Lucinda Elliot's Blog

July 11, 2023

Donal Og: The Grief of a Young Girl’s Heart: One of my Favourite Poems.

I first came across this poem in a book of traditional poetry when I was fourteen. Though I was going through a stage where I despised romanticism, I was touched by this ancient Irish (I believe eighth century) lament from a girl abadoned by her lover. It is difficult to find the English transation of the full version these days. The nine verse one by Lady Gregory is better known. Still, perhaps because this is the version that I came across first, this is the one I prefer.

The contrast between the vernacular speech with the references to rural village life and the fanciful promises that the young man made to the girl when he courted her, followed by her coming upon him when he is in the act of callously abandoning her and riding off into an unknown future by himself, acting as though there is nothing between them, is evocative.

The stark image of the liar riding off, ‘making nothing of’ the girl to whom he made those impossible promises, made a deep impression on me even at fourteen.

The Grief of a Girl’s Heart

O Donall Og, if you go across the sea, bring myself with you and do not forget it; and you will have a sweetheart for fair days and market days, and the daughter of the King of Greece beside you at night.

It is late last night the dog was speaking of you; the snipe was speaking of you in her deep marsh. It is you are the lonely bird through the woods; and that you may be without a mate until you find me.

You promised me, and you said a lie to me, that you would be before me where the sheep are flocked; I gave a whistle and three hundred cries to you, and I found nothing there but a bleating lamb.

You promised me a thing that was hard for you, a ship of gold under a silver mast; twelve towns with a market in all of them, and a fine white court by the side of the sea.

You promised me a thing that is not possible, that you would give me gloves of the skin of a fish; that you would give me shoes of the skin of a bird, and a suit of the dearest silk in Ireland.

O Donall Og, it is I would be better to you than a high, proud, spendthrift lady: I would milk the cow; I would bring help to you; and if you were hard pressed, I would strike a blow for you.

O, ochone, and it’s not with hunger or with wanting food, or drink, or sleep, that I am growing thin, and my life is shortened; but it is the love of a young man has withered me away.

It is early in the morning that I saw him coming, going along the road on the back of a horse; he did not come to me; he made nothing of me; and it is on my way home that I cried my fill.

When I go by myself to the Well of Loneliness, I sit down and I go through my trouble; when I see the world and do not see my boy, he that has an amber shade in his hair.

It was on that Sunday I gave my love to you; the Sunday that is last before Easter Sunday. And myself on my knees reading the Passion; and my two eyes giving love to you for ever.

O, aya! my mother, give myself to him; and give him all that you have in the world; get out yourself to ask for alms, and do not come back and forward looking for me.

My mother said to me not to be talking with you to-day, or to-morrow, or on the Sunday; it was a bad time she took for telling me that; it was shutting the door after the house was robbed.

My heart is as black as the blackness of the sloe, or as the black coal that is on the smith’s forge; or as the sole of a shoe left in white halls; it was you put that darkness over my life.

You have taken the east from me; you have taken the west from me; you have taken what is before me and what is behind me; you have taken the moon, you have taken the sun from me; and my fear is great that you have taken God from me!

June 20, 2023

More on the Mary Sue and the Marty Stu

IX: Pamela is Married 1743-4 Joseph Highmore 1692-1780 Purchased 1921 http://www.tate.org.uk/art/work/N03575

IX: Pamela is Married 1743-4 Joseph Highmore 1692-1780 Purchased 1921 http://www.tate.org.uk/art/work/N03575I have written before about the Mary Sue and the Marty Stu/Gary Stu. It’s rather fun to poke fun at the most outrageous versions of this pest, for instance, its original manifestations in Samuel Richardson’s Pamela, and Fanny Burney’s Evelina.

I personally like the term, though many writers hate it: I think that the dread of creating such a detestable paragon is salutary for all writers, and don’t agree with the current backlash against it.

I agree that it has been too routinely applied by critics or readers to any competent, attractive female protagonist, and this happens a great deal less often with supposedly irresistibly handsome, gifted male leads.

But one can create a good looking, socially adequate – even charming – talented lead character, even one who is ‘The Chosen One’, without creating either a Mary Sue or Marty Stu.

That is fine, so long as the character is not ridiculously perfect physically and/or mentally, and/or far from perfect, not even particularly remarkable in any way, but for some reason admired and loved by everyone, or a character who is made to win every struggle and indulged by the author like a spoilt child.

The following article and some of the reactions elucidate the problems surrounding the Mary Sue or Marty Stu trope, and why so many readers and writers fail to understand exactly what is meant, with the result that the term is overused.

How to Avoid Writing a Mary Sue Character

One of the commentators – I suspect a young and inexperienced writer – is outraged, and accuses the poster of objecting to good looking, talented people and opposing the whole idea of escapism.

But she misses the point in her ingenuous response.

If you are writing some form of escapism, for instance, you certainly do need interesting, often physically attractive characters who get drawn into unusual adventures, frequently by accident. You may need larger than life characters, or perhaps, mundane characters with extraordinary powers as yet unexplored.

What you don’t need are characters who always look marvellous, even when half dead, or climbing out of a swamp, or characters whose looks every single person praises (after all, no film star is universally admired, however cosmetically enhanced: people will always, fortunately, be impressed by different types).

What you don’t need are lead characters who win every battle through some omniscient plot interference from the author, or an idealised version of the author herself or himself.

And while in Fantasy fan fiction in particular, Mary Sue characters have been inserted into stories who have brought a lot of disrepute on a character being a distant or poor relative of a hero, of course, a character can be written as a distant relative or a poor relation of the hero, without necessarily being a Mary Sue.

To return to the classic examples I have used before: Samuel Richardson’s Pamela has been accused of being a Mary Sue, and rightly. The same with Fanny Burney’s Evelina.

They are depicted as having faultless appearances, which nobody does anything but admire in what has been termed ‘choric praise’. Their faults of character are such minor blemishes – a little timidity here, a spot of social awkwardness there – that they can undergo no real character development during the story.

Everyone likes and admires them save those who are jealous, and even these jealous detractors are depicted as being unable to find a single aspect of them which is imperfect.

This is not only ridiculously unrealistic – jealous people will always find some features, physical and mental, to criticise about someone they resent, but far from inspiring admiration in the spirited reader, it inspires boredom and irritation.

Besides this, these heroines’ doting authors indulge them at every turn in twisting events so that no real harm comes to either. Through Samuel Richardson imposing a wildly improbable moral conversion on Mr B’s part, and Fanny Burney inserting a series of heavy handed plot contrivances, both Pamela and Evelina get the happy ending that we are told they richly deserve.

The characters are also boring. They have nothing to say beyond acting as ventriloquist’s dummies in expressing their author’s sententious views about virtue and right conduct.

Jane Austen’s Elizabeth Bennett has been accused of being a Mary Sue, mainly because she is a girl from a comparatively poor background who attracts and marries a great landowner from an aristocratic background.

As I have said elsewhere, this is unfair. Elizabeth Bennett only gradually attracts Mr Darcy, who originally has so low opinion of her attractions that he refuses to dance with her. He comes to notice her wit and charm during the time that they are forced to spend together at social occasions generally and at Netherfield.

This is clever writing from Jane Austen. The hero only gradually and reluctantly comes to admire the heroine. The author gives us a rare insight into Mr Darcy’s point of view here:

‘Mr. Darcy had at first scarcely allowed her to be pretty; he had looked at her without admiration at the ball; and when they next met, he looked at her only to criticise. But no sooner had he made it clear to himself and his friends that she hardly had a good feature in her face, than he began to find it was rendered uncommonly intelligent by the beautiful expression of her dark eyes. To this discovery succeeded some others equally mortifying. Though he had detected with a critical eye more than one failure of perfect symmetry in her form, he was forced to acknowledge her figure to be light and pleasing; and in spite of his asserting that her manners were not those of the fashionable world, he was caught by their easy playfulness…’

The heroes of ‘Pamela’ and ‘Evelina’ are Marty Stu’s to match the heroines. Mr B is depicted, not as a hectoring hypocrite with rapist and obsessive tendencies, but as a dashing villain.

One of Pamela’s allies, his housekeeper in Bedfordshire points out that there are ‘wicked women enough in the world’ to satisfy his lust, without his having to force himself on a ‘lamb’ like Pamela.

In fact, this is one of the aspects of his behaviour that makes no sense, and even seem to hint at some mental condition (of course, Richardson is far too crude a writer to have had such an intention). Why does a vain man of rakish tendencies put himself to so much inconvenience in his attempts to force himself on a girl who is not responsive, however attractive he might find her?

Richardson, though he does not explicitly state this, clearly sees Pamela’s continued refusal of him as tickling Mr B’s vanity and inflaming his lust, but the amount of energy Mr B expands to impose his will seem to make sense to nobody but some sort of narcissist.

Lord Orville is such a cardboard character that it is difficult even to sum up an image of him without feeling bored. Suffice it to say that he is perfect, physically and mentally. His only fault, if it can be called that, is that at first he only admires Evelina’s appearance. Later on, supposedly comes to appreciate her qualities of mind, though I have to admit I don’t know exactly what these are, apart from sententiousness.

As I have commented before, Charley Kinraid in Elizabeth Gaskell’s ‘Sylvia’s Lovers’ is a classic Marty Stu.

He is the ‘boldest Specksioneer on the Greenland Seas’, dashing, strikingly handsome, fearless, astute, admired by all men save his jealous rival Philip Hepburn (and even he secretly envies his ‘bright, handsome mien and ease of manner’ ) and desired by all women. One girl at least is rumoured to have died of a broken heart after he stopped paying court to her. He has already left behind him a stack of cast off ex-girlfriends.

He is indistructable, turning adversity to his own advantage, rising to the top like a cork shooting up in water. Instead of dying or disappearing at sea – which would be the probable fate of sailor press ganged into the Royal Navy – he returns as a lieutenant, soon to be promoted to captain. Having been cheated out of marrying Sylvia Robson, he comforts himself by marrying an heiress, who admires him even more than he admires himself.

In other words, he is indulged by the author, not even being left with a limp when he breaks his leg during action at the Battle of Acre, while after Sylvia refuses to run away with him, he is provided with as happy an ending as the author can devise by way of wish fulfilment for her lost sailor brother.

It has to be said, in fairness to the author, that Kinraid does actually look ‘wan’ with ‘haggard eyes’ when Sylvia first sees him heroically risen from his sick bed after being shot by the press gang to attend his friend Darley’s funeral. The blood loss does affect his appearance slightly, and so he does diverge from the stereotypical Marty Stu that far. However, he soon recovers, and Sylvia is all admiration for his flashing eyes and teeth, and equally flashy tales of adventure.

In fact, he is a ‘dark hole’ Marty Stu, as he draws in everyone about him to the point where he has no possible rivals. Despite Monkshaven (Whitby) being a busy whaling port, there are no other dashing, handsome, vigorous sailors mentioned in the whole novel.

Here is an amusing exploration of that type of Marty Stu, which I have linked before:

https://tvtropes.org/pmwiki/pmwiki.php/Main/MartyStu

Clearly, authors who create such a monstrosity as the full blown Marty Stu or Mary Sue have never stopped to think that perhaps it might not endear a male or female lead to the readership to have him or her or him sexually irresistible and admired by everybody.

Of course, if anything, it has the opposite effect. Having a few people unfairly contemptuous or dismissive of, or even merely indifferent to her or him, critical of his or her looks, capacities, character etc, generally works far better. So does giving him or her some serious competition in attractions, fighting skills, eligibility as a marriage partner, etc.

I think I may well be typical – though of course, the English are notorious for siding with the underdog – in that if in some story, any character is criticised on all sides, I tend to feel sympathy for him or her, however much that criticism is deserved.

This tends to be comparatively rare for a male or female lead: but it is worth keeping in mind as a good way of arousing sympathy for an anti hero. But note, it has to be the right kind of abuse: ‘He is a terrible villain, with a shocking reputation with the women’ isn’t going to arouse any sympathy in the reader.

That sounds like the typical cardboard rascal seducer. Depicting the said villain suffering some indignity, or revealing some vulnerability, is a bit more like it.

I personally think it is a great mistake of many writers – particularly those who are writing heroes who are meant to be romantically appealing – to depict a male lead who never looks silly, has no real weaknesses, and is, in the words of Elizabeth Bennett ‘not to be laughed at.’ Surely, a male lead who can’t survive looking ridiculous is a very weak creation?

[image error]May 29, 2023

Some Thoughts on The Ending of King Lear.

The weight of this sad time we must obey;

Speak what we feel, not what we ought to say…’;

King Lear mourns Cordelia’s death, James Barry, 1786–1788

King Lear mourns Cordelia’s death, James Barry, 1786–1788These words from Shakespeare’s greatest tragedy came back to me a couple of days ago. I thought how relevant they are to the age of official and social censorship of speech deemed to be offensive. The truth often does tend to be offensive, when one doesn’t want to face it. King Lear thought that Cordelia was being extremely offensive.

This, which is the first part of Edgar’s closing speech at the end of King Lear is, of course, so world renowned that its genius needs no comment from me. Realistically, writers are going to struggle to write anything that comes near the terse, bleak magnificence of those lines.

This speech, given as he stands surrounded by the dead bodies of so many of the main actors in the drama, reflects a spirit of melancholy contemplation after the violent passions, treachery, and carnage of the recent events. It sums up some lessons learnt from the terrible events that led on from the foolish egotism and credulousness of King Lear and (the anachronistic) Duke of Gloucester, the unflinching courage and honesty of Cordelia and the Duke of Kent.

When the touchy and credulous Lear and Gloucester retained their power, honesty was punished, while dishonesty, treachery and flattery were rewarded. That has happened often enough in the real world throughout history, perhaps in our own time more than at any other time, perhaps not.

Both Lear and Gloucester either always were, or with the advancing years have now become, appalling judges of character. That being so, it is a wonder that the straightforward Cordelia and Edgar retained their fathers’ favourites as long as they did.

Of course, Edmund had only just come back from abroad (to overhear his father making coarse jokes about his parentage and stating that he will be sent off again, which arguably provokes him into his campaign to steal his legitimate brother’s inheritance).

Still, it is odd that Goneril and Reagan, who must have long been jealous of Cordelia, haven’t seemingly worked against her before, as neither seems to have been long married.

As a Jacobean playwright, Shakespeare doesn’t seem to have troubled about such minor details of backstory. These inconsistencies are one of the things which I find such a puzzle in reading his works. His characters can seem so human, but they are portrayed with contradictions in behaviour which make no sense to the modern mindset.

After all, a similar objection could be made to Lear’s insisting on having the Fool with him, given his habit of attacking the King with bitter jokes about his idiocy in giving his away kingdom to Goneril and Regan. But maybe the Fool’s wit was less ‘bitter’ before Cordelia was dismissed without a dowry.

Of course, there is the puzzle of the disappearance of the Fool after his exit with the words, ‘And I’ll go to bed at noon’. It is assumed he is dead. After all, his ‘falling away’ after Cordelia’s banishment is commented on by King Lear and by others. He seems to be in a decline. His last words could indicate that he is going to this deathbed.

Some critics suggest that as the character had served his purpose, Shakespeare lost interest in him. This outrages all a modern reader’s ideas, but may be so. Again, perhaps some reference to him was edited out of the Folio’s which have come down to us. It could also be that King Lear is refereeing to him in his mourning over Cordelia’s body, ‘And my poor fool is hanged’. We will never know, given that Cordelia has been hanged herself on Edmund and Goneril’s orders, and King Lear is mourning over her body.

King Lear’s realisation of his idiocy, like all repentance, comes too late to alter the tragic outcome in this play.

When he realises that he is dying, Edmund wishes to undo the evil that he has done, and urges that soldiers run to Cordelia’s prison to revoke the orders he has given for her murder. It is too late.

At least, at this close of the play, there is implied hope for the future, in this evidence that Edgar , as the next ruler, has learnt from this tragic example. The man we have come to know is, as ruler, highly unlikely to banish people for stating uncomfortable facts, not saying what he wants them to say.

That is the only happy outcome from the tragedy of King Lear and his three daughters, and the Duke of Gloucester and his two sons.

…But, perhaps that is not such a little thing, after all.

April 30, 2023

‘Brave New World’ by Aldous Huxley: A Soft Dystopia Grimly Relevant to Today

I found ‘Brave New World’ far more relevant to the divisive cultural issues of today than I had thought possible.

A world where history is forgotten or despised, and classic English Literature derided or unknown, one where critical thought is replaced by slogans, is grimly apposite to today. I was alarmingly reminded of the woke attack on European history and culture, and the sinister replacement of reasoned debate with slogans from those who equate having ‘progressive ideas’ with identity politics.

‘Brave New World’ might be called a ‘soft’ sort of dystopia of conformist horror, as distinct from George Orwell’s ‘boot in the face’ nightmare society, which depicts a grotesque level of surveillance, brutal oppression, poverty and general joylessness. It interests me that Huxley’s dystopia was written in 1932, and yet seems a more sophisticated approach than that of Orwell.

It always struck me that Orwell’s society was impossible, economically and otherwise. The amount of surveillance required would surely be unobtainable, even with today’s technology.

Above anything, though, I found it massively inefficient.

Of course, the lack of personal privacy and comfort of Orwell’s dystopia is clearly based on the drab lifestyle, food shortages, censorship, spying and grim ‘Five Year Plan’ work ethic of the USSR between the wars – with a bit of World War II British rationing thrown in.

By contrast, Huxley’s New World State is a place of hedonism and unthinking consumerism, where the name of Henry Ford is worshipped (ironically, though, nobody uses anything so old fashioned as a car; people travel about by helicopter). There is very little privacy here, either, as you are expected to be as sociable, as unthinking as toddlers.

However, almost everyone fits in happily to the world order, as they are all genetically engineered and then subjected to years of sleep hypnosis to suit their future role in society. The family has been abolished, babies are grown in giant test tubes, children raised in state nurseries. The idea of romantic love, marriage, the family or a biological mother is seen as obscene. So are any emotional ties, for ‘everyone belongs to everyone else’.

Everyone is kept looking young to the point of death, and encouraged to spend leisure time in sports and having casual sex. Any unhappiness can be driven away by taking the drug Soma, and in fact, generous rations of the drug are dispensed after every working day.

Oddly enough, while there is little humour in Orwell’s ‘1984’, ‘Brave New World’ made me laugh out loud in places. For instance, at the depiction of the ludicrous obligatory fortnightly orgies:

‘Round they went, a circular procession of dancers, each with hands on the hips of the dancer preceding, round and round, shouting in unison, stamping to the rhythm of the music with their feet, beating it, beating it out with their hands on the buttocks in front; twelve pairs of hands beating as one…And all at once, a great synthetic bass boomed out the words which announced the approaching atonement and final consummation of solidarity…

‘Orgy-porgy, Ford and fun,

Kiss the girls and make them One,

Boys at one with girls at Peace,

Orgy-porgy gives release.’

What struck me more even than the horror of Orwell’s society is its inefficiency. The amount of time and money that must be spent on surveillance of those who work for ‘the party’ must be phenomenal, what with the CCTV in each room, the spies everywhere, the constant outpouring of propaganda from harsh loudspeakers. Where the citizens of the New World State engage in orgies, the inhabitants of Ingsoc have to participate in daily sessions of ‘Hate Time’ where the public enemies are derided. Both are supposed to serve as a form of release, but the orgiastic one strikes me as infinitely more effective. Then, the citizens of 1984 (except for the proles) are not allowed any such pleasures as drugs or sensual enjoyment; procreation is part of ‘our duty to the Party’.

Nobody bothers about happiness in the world of ‘1984’. In Huxley’s futuristic society, there is the ready available doses of Soma to keep everyone in a drug induced state of blissfulness. This is besides the everyday luxuries such as taps running with scent, canned music on demand (of course, that is nothing out of the ordinary now), films which stimulate all the senses, etc. People are discouraged from instrospection or ever spending any time alone. Instead, they must be sociable at all times – and being constantly youthful, they have the energy to handle it – and spend much of their leisure time playing sports.

In fact, there are some misfits in this society. One of these is Bernard Marx, who is one of the specially bred intellectual ‘Alpha’s’. Unlike the others, however, he is considered a poor specimen.

It is suggested that something must have gone wrong with the environment in which his embryo was cultivated: ‘Bernard’s physique was hardly better than the average Gamma. He stood eight centimetres short of the standard Alpha height, and was slender in proportion. ..Hence the laughter of the women to whom he made proposals…Each time he found himself looking on at he level, instead of downwards, into a Delta’s face, he felt himself humiliated. Would the creature treat him with the respect due to his caste? ’

Bernard has struck up a sort of friendship – though close friendships are discouraged, as ‘everyone belongs to everyone else’ – with a professional writer of slogans, the athletic ‘Escalator Squash’ champion and popular lover, Helmholtz Watson (rumoured to have had 640 different girls in under four years), who suffers from a feeling of social isolation through his sense of having excessive intellectual gifts. The two men sometimes spend time alone talking together, rather than doing sports or philandering, watching ‘feely’ films or engaging in other communal activities. This is subversive in itself. Helmholtz knows he has something important to say, but doesn’t know what. Bernard longs for all the emotions of which he suspects he, and everyone else, has been deprived. This sense of deprivation brings them together.

Another person who doesn’t quite fit in is Lenina Crowne. Though very pretty and popular, in fact, notoriously ‘pneumatic’ – people, with their limited vocabularies, invariably use that description rather than ‘voluptuous’ ‘curvaceous’ or any variant –she has an unfortunate tendency to prefer to have only one man on the go at a time. She is also eccentric in liking Bernard Marx, due to his unusual eyes.

Bernard’s attempt to have a deeper communication with Lenina than is normally encouraged fail miserably, he does take her on a visit to a Mexican Native American Reservation. On these, people surrounded by high fences, lead life in the old way: babies are born, young men and women grow up and fall in love, get married, and have more babies. People age and die. There is ignorance, dirt and disease, but there is also intensity of emotion.

When Bernard has his trip to the Reservation authorised by the director of his department, the man is startled into recounting a trip he took their himself, with a young Beta Minus woman. In a grotesque accident, he lost her on a mountain in a thunderstorm. Though he comforted himself with the (implanted) thought that, ‘The social body persists although the component cells may change’ (this sounds like Durkheim), he fretted about this.

After this, ‘Furious with himself for having given away a discreditable secret, he vented his rage on Bernard. The look in his eyes was now frankly malignant. “And I should like to take this opportunity, Mr Marx’”, he went on, “Of saying that I am not at all pleased with reports I receive of your behaviour outside working hours. You may say this is not my business. But it is. I have the good name of the Centre to think of. My workers must always be above suspicion, particularly those of the highest castes…’

Though the director threatens to have him transferred to Iceland, Bernard is, ‘exalting, as he banged the door behind him, that he stood alone embattled against the order of things’. Later, he boasts that he told him to go to ‘the Bottomless Past’.

At the reservation, Bernard is fascinated. Lenina is appalled, and has run out of Soma. However, they do meet a fair haired, blue eyed youth named John, whose mother, Linda, was taken in by the inhabitants of the Reservation when she was lost on the mountain over twenty years ago. He has been educated partly by Linda, who retains happy memories of life in ‘The Other Place, to which she could never return, because she had suffered the ignominy of giving birth to a child. He has discovered a tome of Shakespeare’s collected works, and has all his ideas from this, combined with some of the myths and legends of the Native Americans. Though mistreated by the others on account of his skin colour and his mother’s careless promiscuity, he is native, idealistic, and at once besotted by the ornamental looking Lenina. To her dismay, she finds herself becoming intrigued by him in return.

This changes everything. Bernard, having lost interest in persuading Lenina to join him in his subversive ideas, decides to exploit his finding of ‘The Savage’, unintentionally fathered by the Director.

John agrees to go with them to London, so long as they take his mother as well: he quotes Miranda from ‘The Tempest’: ‘O brave new world, that has such people in it.’

‘You have a most peculiar way of talking, sometimes,” said Bernard, staring at the young man in perplexed astonishment. “And, anyhow, hadn’t you better wait till you actually see the new world?”

John’s arrival in the outside world leads to the director’s disgrace and fall, when he is in the very act of denouncing Bernard for ‘Heretical views on sports and Soma, by the scandalous unorthodoxy of his sex life, by his refusal to obey the teachings of Our Ford and behave out of office hours ‘like a babe in a bottle’. Bernard’s mother appears and confesses that the director made her have a baby, and John claims him as his father. Mortified, the director accepts banishment.

Everyone is fascinated by the handsome ‘Savage’, even apart from Lenina, whose life is being ruined by her unaccustomed feelings for him. Bernard capitalises on ‘The Savage’s’ fame, and becomes lulled by it into feeling suddenly quite happy with his place in society.

But then, John starts to become disillusioned with this world outside, and this eventually leads to disaster for them all.

SPOILERS FOLLOW

Winston Smith breaks when faced with having his face gnawed by starving rats. Bernard breaks much more easily, at the prospect of being exiled to Iceland. I assume that Orwell expanded this scene, adding massive depths of horror and brutality, in 1984, both in the behaviour of the man on his way to Room 101 at the beginning of Smith’s torture in the Minstry of Love, and in Smith’s betrayal of Julia there (As a matter of fact, it seems to me that the man on his way to Room 101 has broken already, and his going there is a waste of time and energy. He has already offered to cut his children’s throats: how could you be capable of any further turpitude? This seems to be one of several structural weaknesses in the story, unless the implication is that there is some further hideous betrayal that he can make, but goodness knows what it could be: perhaps this is the point of the episode, to keep this horror shrouded in mystery).

Bernard, in fact, is fairly contemptible in this scene of the confrontation with authority, where, faced with nothing worse than exile, he grovels before Mustapha Mond, one of the ten World Controllers: ‘Send me to an Island?…You can’t send me, I haven’t done anything. It was the others. I swear it was the others.’

The similarities between the two scenes at the heart of both novels are obvious. What is interesting, however, is that in Huxley’s scene, Helmholtz is not even angry with Bernard for is betrayal. This is partly his conditioning, of course; deep friendship being incongruous to these people, I suppose that high expectations of loyalty are too.

No doubt there are impossibilities in Huxley’s dystopia. There are almost certainly inefficiencies. For instance, he seems not to have anticipated the development ugly industrial scale farming, which has incarcerated so many animals in prison camps, and so damaged the plants and wildlife, especially the butterflies, in Britain since World War Two. One third of his workforce, in fact, works in agriculture.

Another weakness of the novel is the characterisation, though this is partly a necessary result of the plot, and one which it certainly shares with Orwell’s ‘1984’. After all, the main characters in these dystopias are all necessarily emotionally undeveloped, because of their conditioning. Therefore, while Bernard and Helmholtz suffer from conflict, as does Lenina in her ‘anti social’ exclusive longing for the savage, they are still not, and can never be, rounded characters.

Maybe I am being obtuse, but I didn’t fully understand whether, during the general orgy that takes place in the penultimate scene, after the Savage begins to flog Lenina, is she only slightly hurt? Does she still willingly accept him after that? Why do we not hear any more about her? Where has she gone after the orgy? We are not told.

The implication is that Bernard and Helmholtz are developing as characters and will develop further as a result of their banishment. But what of Lenina? This is one of the most unsatisfactory parts of the unsatisfactory ending.

March 8, 2023

Aristocratic Antagonists and Anti-Heroes in Classic English Novels: the Dukes

Edmund_Blair_Leighton_-_The_Elopement_-_1893.jpg

Edmund_Blair_Leighton_-_The_Elopement_-_1893.jpgIn continuing my posts on Aristocratic Baddies in Classic English Novels, I refer the reader again to the very funny post that inspired it: https://allthetropes.org/wiki/Aristocrats_Are_Evil

The writer(s?) comment that fictional dukes were in most genres not usually evil or at least, opportunistic and morally questionable, like the barons and counts. This might be because many had earned the title of ‘duke’ through military victories, such as the real life first Duke of Marlborough (Winston Churchill’s ancestor, for those who don’t know and are interested).

On the whole, I tend to agree this was the case, before the resurgence of Regency Romance. In reality, of course, dukes have always been scarce on the ground in Britain.

In the world of Regency Romance now, though, if one counts the population of Regency Romance dukes – particularly with non-British writers, one would think that there were more dukes per square mile in Britain than you could shake a stick at. You would think that they were more usual, in fact, than commoners, so how they manage to get enough staff to run their stately homes and castles, let alone secure enough rolling acres in a tiny country approximately the size of Alabama, is a puzzle.

As I have said before, the sad reality is that there have never been more than about twenty-five to thirty dukes in Britain. Most of these were and are elderly and highly respectable (those whose ancestors didn’t win the title through military honours were and are probably making up for being descended from William the Bastard’s marauding robber barons or for the enclosure of common land done by their forebearers).

The problems associated with making an aristocratic pleasure ground of the Britain of the early nineteenth century are perhaps greater than those who defend this obsession with the highest grades of the upper class as harmless escapism are prepared to concede. They are touched on in this perceptive article by romance writers:

Accumulation or: The Problem With Too Many Dukes

One of the writers suggests:

‘And I don’t think manufacturing hundreds of dukes never hurts anyone. Basically we’ve turned Georgian and Victorian England into a romance amusement park. We’ve erased the politically active working class, we’ve made Chartists and Luddites and agricultural workers into comic relief and/or people to be saved by the aristocracy. Sure, none of them are alive now, but their descendants are.’

Maybe all this obsession with dukes was sparked off by the anti-hero bad duke by the originator or of Regency Romances Georgette Heyer in her creation of the Duke of Avon in ‘These Old Shades.’ He in turn was based on another bad duke she had created – Tracy Belmanoir, the Duke of Andover.

Still, it is only fair to say that Heyer did create another duke, the good-natured, unassuming hero of ‘The Foundling’ (1947), The Duke of Sale, who is rather small, pale and quiet and usually, extremely kind to everyone. He is the antithesis of the later duke anti-hero of Regency Romance.

In other genres, I really can’t think of that many dukes in classical fiction who aren’t rulers, minor characters, or relatives of the protagonist, outside Regency Romance. I am sure there are various villainous dukes I can’t call to mind, but they are thin on the ground.

The ducal rulers in various stories set in the Italian states, including Shakespeare’s plays, seem to be a well meaning but dull lot. For instance, there is the interfering do-gooder duke in Shakespeare’s ‘Measure for Measure’ who ends up marrying the novice nun Isabella.

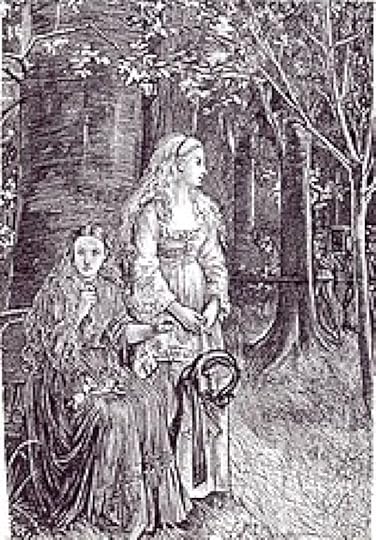

‘Isabella’ by Francis William Topham (1888)

‘Isabella’ by Francis William Topham (1888) He is spying on his subjects in disguise, having decided to see what goes on when he leaves governing the state to his icily virtuous deputy, Angelo. Angelo, naturally, soon goes to bad and develops a passion for a nun, whom he tries to blackmail into going to bed with him. We can imagine the duke going round muttering in a prescient way, ‘All power tends to corrupt, and absolute power corrupts absolutely…’

There are, of course, no dukes, villainous or otherwise, in Jane Austen, whose highest born antagonist is the detestable Lady Catherine de Bourgh, an earl’s daughter.

There is, of course, the Duke of Holdernesse the Sherlock Holmes story, ‘The Adventure of the Priory School’. He is revealed as an antagonist, and is also highly unappealing, middle aged but prematurely aged, afflicted with both an enormously long nose and a great sense of self-importance. The reader is delighted when, having unearthed the kidnappers of his son, Sherlock Holmes rejects his suave attempt to bribe him and gives him a sharp lecture on his treatment of his young son and estranged wife. He does, however, accept the reward of £6,000 odd pounds – which I believe would amount to about £500,000 today.

Another unpleasant – and much earlier – duke is the sixteenth century murderous Duke of Ferrara in Robert Browning’s poem ‘My Last Duchess’ (1842).

An heroic duke is who is, to put it mildly, a man of parts, is Dennis Wheatley’s Duke de Richeleau, Jean Armand Duplessis. Far from being an antagonist, he is wholly heroic. Among other things, he is:

A soldier of fortune.An unarmed combat expertAn expert lover, also twice married, once to an English middle-class girl, once to an archduchess, and the father of a son by a condessa.A formidable occultist .A linguist.A conspirator in the 1903 plot to reinstate the French monarchy and after that, a prisoner and an exile from France.A spy for Alfonso XIII of Spain and later for the British Empire.A financierA bon vivant (Sorry for the foreign expression, but he is after all, a Frenchman…)And so on…His skills are limitless, save for sympathy with anarchists, communists, socialists and radicals generally. He is also very handsome, and drives a Hispano-Suiza with an entourage of footman.

His exploits are detailed over the course of eleven novels, and great fun, if you can accept that the point of view in the Days of Empire was rather different from the values considered acceptable now.

[image error][image error][image error]February 18, 2023

Bad Baronesses and Cruel Countesses: Aristocratic Antagonists in Classic English Fiction: The Women

In my last post, I linked a very funny article about bad titled people in fiction.

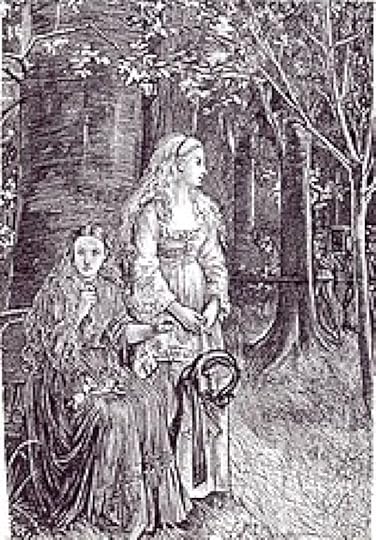

https://tvtropes.org/pmwiki/pmwiki.php/Main/AristocratsAreEvil Here is the predatory Carmilla, with her victim in the forest, annoyed by the hymn singing at the funeral procession of a local girl, who has died suddenly, and unexpectedly…

Here is the predatory Carmilla, with her victim in the forest, annoyed by the hymn singing at the funeral procession of a local girl, who has died suddenly, and unexpectedly…After that, I discussed a few examples of morally reprehensible barons, counts and – usually the worst of the lot – baronets in classic English Literature.

I saved the discussion of Bad Baronesses and Cruel Countesses for this separate post. The question of the female equivalents is a difficult one. Sadly, there are few countesses and baronesses in classic stories who go about being bad on their own account. However, in accordance with the traditional female role, a large number of them do it to further their husband’s careers. An extreme example is Lady Macbeth.

There are by contrast Goneril and Regan in ‘King Lear’, who are more concerned about furthering their own ambitions than those of their husbands. As the king’s daughters, they are about as high up on the social scale as you can get. They were not called ‘princesses’, however, as that was a term not much used until much later. They are described as being married to dukes, presumably for the status to make sense to a Jacobean audience, though the title would not have existed in Celtic Britain. How long they have been married is unclear. Presumably not long enough for the Duke of Albany to understand Goneril’s real character: ‘O Goneril, you are not worth the dust the rude wind blows in thy face.’ The Duke of Cornwall is a more suitable partner for Regan, but after he suffers form the indignity of being killed by a servant objecitng to his carrying out a spot of torture, Regan as a widow is free to plan to marry Edmund, which leads to Goneril’s furious jealousy.

They seem to be completely immoral, conniving, sensuous, and unscrupulous. Something certainly was wrong with their upbringing, and with such a vain, silly father as King Lear, that is hardly surprising. Still, the same environment has intriguingly produced a paragon in Cordeilia. Though they combine against Cordelia, whose honourable qualities they presumably resent, they soon fall out in their mutual jealousy over the embittered son of the Duke of Gloucester, Edmund.

I suppose they admire him so much because he is as bad, or worse, than they are. Edmund doesn’t have a title through being illegitimate, and acts as wickedly through his chagrin over that as any titled villain in literature.

I may be overlooking some obvious examples, so I hope that readers will correct me if I am wrong, but generally, aristocratic women in classics who decide to be bad of their own accord tend to be sirens. You don’t get much in the way of Mad Scientist Baronesses, say, or even Mass Murderer Countesses like the real life Hungarian Countess Elisabeth Bartory. There are, of course, Dracula’s three vampire wives, but they might actually be said to be furthering his career in their own way.

Another vampire countess siren is of course, Carmilla, Countess of Karnstein, in Sheridan le Fanu’s novel ‘Carmilla’. She is acting on her own accord, and seems – intriguingly for the era – to be more attracted to female rather than male victims. How far Sheridan le Fanu’s depiction of her as having lesbian urges was a conscious one, is unclear.

In the mundane world, Lady Davers in Samuel Richardson’s ‘Pamela’ (1740) is Mr B’s sister, even more proud and dictatorial than he is. In fact, her attitude reflects his own – typical of that of the upper class towards servant maids –until he becomes ‘converted’ from a would-be rapist into a devoted husband.

Lady Davers’ encounters with Pamela are purely ridiculous, made tolerable only by the elegant language of the eighteenth century: ‘Creature, said she, art thou to beg an excuse for me? Art thou to implore my forgiveness? Is it to thee that I am to owe the favour, that I am not cast headlong from my brother’s presence? Begone to they corner, wench…’

Note how Lady Davers addresses Pamela using the archaic English familiar ‘art thou’. In addressing Pamela as a ‘wench’, Lady Davers is not only showing that she is of a low social status, she is also – and this is a concept which those who are accustomed to modern democratic ideas about equality find hard to realise – implying that a maidservant is of too low a social caste to aspire to virtue. Maidservants were not expected to value their spiritual welfare sufficiently to place it above pleasing their master. That was the subversive aspect of Richardson’s message, which sits uneasily with Pamela’s toadying subsevience.

There is ‘Lady Booby’ in Henry Fielding’s ‘Joseph Andrews’. Her name, of course, has nothing to do with coarse references to her pulchritude, referring to a term used at the time for a fool. Critics of Samuel Richardson’s ‘Pamela’ jeered at the ineffectual if sexually abusive master, Mr B, as ‘a booby’ most notably in the scurrilous and hilarious spoof ‘Shamela’.

Lady Booby is not a fool herself, but the wicked widow of one. Sadly, she frankly isn’t very interesting. Like the other women in Fielding’s novels, she is not a developed or rounded character. She pursues her footman, the hero Joseph Andrews – written as a virtuous male equivalent of his supposed sister Pamela – with suitable abuse of power, and is frankly made of cardboard.

Slightly off topic, I think I would have found the novel funnier if, as a spoof, it had shadowed the plot of the original novel, where the author provides Pamela with every sort of feeble excuse for remaining in Mr B’s household before fleeing to safety.

Another villainess of title – a sort of earthly bad fairy- is the earl’s daughter Lady Catherine de Bourgh in Jane Austen’s ‘Pride and Prejudice’. She is astounded by the independence of mind that Elizabeth Bennet shows in refusing to confide to her whether or not she would accept an offer of marriage from Lady Catherine’s nephew, Mr Darcy. Lady Catherine’s ‘dignified impertinence’ is abandoned and she rages about ‘The upstart pretensions of a young woman without family, connections, or fortune’.

Mr Darcy, of course, shares her haughtiness until he is taught some humility by Elizabeth.

It is intriguing that the aristocrats and even baronets in Jane Austen – unlike many in the genre of Regency Romance she inspired – are a generally unsympathetic lot. This may reflect her own conviction that the landed gentry – the class to which she belonged herself – were overall more socially responsible and led more worthwhile existences, strongly connected as they were with the land and the local population.

It is notable that there are no aristocrats involved in the Gothic excesses of Emily Bronte’s ‘Wuthering Heights’, only the landed gentry of the Yorkshire Moors, as represented by the Lintons and the Earnshaws.

Aristocratic female antagonists seemed, intriguingly, to become less independently evil as the nineteenth and twentieth centuries went on, in popular fiction at least.

The siren Lady Barbara Childe in Georgette Heyer’s ‘An Infamous Army’ (1935) is seen as outrageous, but it wouldn’t be very hard to shock a society which gossips about a woman wearing polish on her toenails. She is also fond of taking drugs and breaking the hearts of admirers and rivals, but is really only an anti-heroine who repents at the end.

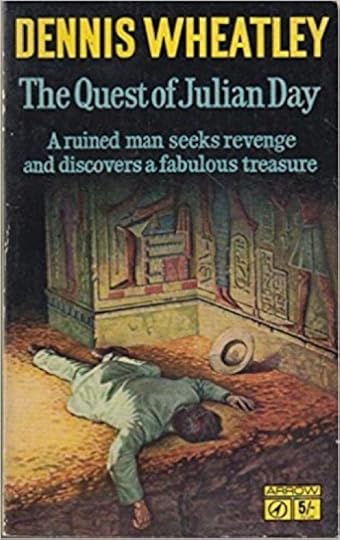

I remember being very impressed at thirteen by Princess Oonas Shahamalek in one of Dennis Wheatley’s novels, ‘The Quest of Julian Day’ (1937).

Julian Day is hit on the head by the possessive siren Princess Oonas, who leaves him to die of thirst in an Egyptian tomb…

Julian Day is hit on the head by the possessive siren Princess Oonas, who leaves him to die of thirst in an Egyptian tomb…Small, but extremely voluptuous, she is still in her early twenties, though a widow, and a siren in the best tradition of Cleopatra, quite happy to enjoy and later callously to abandon lovers.

She is used by the villains of the piece to the seduce ‘Julian Day’. ‘Julian Day’ is in fact, a disgraced aristocrat whose real name is Hugo Julian du Crow Fernhurst, and an unofficial spy himself.

This encounter takes place in a desert tent in Egypt. The agreement is that after this bit of fun – which involves a game of catch with Princess Oonas only wearing a filmy nightdress and some intoxicating perfume – she will then have him murdered in his sleep. However, she finds him such a good lover that she decides to keep him alive after all for more of the same. Julian Day wakes up to hear her instructing her men that she has decided she likes him after all, and the murder is off. When the assassins arrive, she starts shooting at them.

Later, overcome with jealousy of another women on Julian Day’s proposed treasure hunting expedition, and unable to face the threat of losing him, as she sees it, to another, she traps him in a tomb, leaving him to die of thirst.

He escapes. Seeing him later, she assumes he is an evil spirit, and runs out into a sandstorm to a certain death. I assume Dennis Wheatley, who was a great believer in the Law of Karma, wrote this as part of its workings. I thought this was rather a shame. I much preferred her to her rival, Sylvia Shane, despite her treacherous nature. As a take on a ‘desert romance’ I definitely preferred that episode to the self abnegating ‘He’s a Rapist, But I Love Him’ approach of ‘The Sheik’.

Of course, there are a large number of bad female aristocrats in modern fiction, especially in fantasy, but this post being about classic novels, I shall finish this post with the magnificently wicked Princess Oonas.

[image error][image error][image error][image error][image error]Bad Baronesses and Cruel Countesses: Titled Aristocratic Antagonists in Classic English Fiction: The Women

In my last post, I linked a very funny article about bad titled people in fiction.

https://tvtropes.org/pmwiki/pmwiki.php/Main/AristocratsAreEvil

After that, I discussed a few examples of morally reprehensible barons, counts and – usually the worst of the lot – baronets in classic English Literature.

I saved the discussion of Bad Baronesses and Cruel Countesses for this separate post. The question of the female equivalents is a difficult one. Sadly, there are few countesses and baronesses in classic stories who go about being bad on their own account. However, in accordance with the traditional female role, a large number of them do it to further their husband’s careers. An extreme example is Lady Macbeth.

There are also Goneril and Regan in ‘King Lear’. As the king’s daughters, are about as high up on the social scale as you can get. They were not called ‘princesses’, however, as that was a term not much used until much later. They are completely immoral, conniving, sensuous, and unscrupulous. Though they combine against their sister Cordelia, whose honourable qualities they detest, they soon fall out in their mutual jealousy over the embittered son of the Duke of Gloucester, Edmund.

I suppose they admire him so much because he is as bad, or worse, than they are. Edmund doesn’t have a title through being illegitimate, and acts as wickedly through his chagrin over that as any titled villain in literature.

I may be overlooking some obvious examples, so I hope that readers will correct me if I am wrong, but generally, aristocratic women in classics who decide to be bad of their own accord tend to be sirens. You don’t get much in the way of Mad Scientist Baronesses, say, or Mass Murderer Countesses like the real life Hungarian Countess Elisabeth Bartory. There are, of course, Dracula’s three vampire wives, but they might actually be said to be furthering his career in their own way.

Another vampire countess siren is of course, Carmilla, Countess of Karnstein, in Sheridan le Fanu’s novel ‘Carmilla’. She is acting on her own accord, and seems – intriguingly for the era – to be more attracted to female rather than male victims. How far Sheridan le Fanu’s depiction of her as having lesbian urges was a conscious one, is unclear.

In the mundane world, Lady Davers in Samuel Richardson’s ‘Pamela’ (1740) is Mr B’s sister, even more proud and dictatorial than he is. In fact, her attitude reflects his own – and typical of the attitude of the upper class towards servant maids –until he becomes ‘converted’ from a would-be rapist into a devoted husband.

Lady Davers’ encounters with Pamela are purely ridiculous, made tolerable only by the elegant language of the eighteenth century: ‘Creature, said she, art thou to beg an excuse for me? Art thou to implore my forgiveness? Is it to thee that I am to owe the favour, that I am not cast headlong from my brother’s presence? Begone to they corner, wench…’

Note how Lady Davers addresses Pamela using the archaic English familiar ‘art thou’. In addressing Pamela as a ‘wench’, Lady Davers is not only showing that she is of a low social status, she is also – and this is a concept which those who are accustomed to modern democratic ideas about equality find hard to realise – she is implying that she is of too low a social caste to aspire to virtue. Maids were not expected to value their spiritual welfare sufficiently to value it above pleasing their master. That was the subversive aspect of Richardson’s message.

There is ‘Lady Booby’ in Henry Fielding’s ‘Joseph Andrews’. Her name, of course, has nothing to do with coarse references to her pulchritude, referring to a term used at the time for a fool. Critics of Samuel Richardson’s ‘Pamela’ jeered at the ineffectual if sexually abusive master, Mr B, as ‘a booby’ most notably in the scurrilous and hilarious spoof ‘Shamela’.

Lady Booby is not a fool herself, but the wicked widow of one. Sadly, she frankly isn’t very interesting. Like the other women in Fielding’s novels, she is not a developed or rounded character. She pursues her footman, the hero Joseph Andrews – written as a virtuous male equivalent of his supposed sister Pamela – with suitable abuse of power, and is frankly made of cardboard.

Slightly off topic, I think I would have found the novel funnier if, as a spoof, it had shadowed the plot of the original novel, where the author provides Pamela with every sort of feeble excuse for remaining in Mr B’s household before fleeing to safety.

Another villainess of title – a sort of earthly bad fairy- is the earl’s daughter Lady Catherine de Bourgh in Jane Austen’s ‘Pride and Prejudice’. She is astounded by the independence of mind that Elizabeth Bennet shows in refusing to confide to her whether or not she would accept an offer of marriage from Lady Catherine’s nephew, Mr Darcy. Lady Catherine’s ‘dignified impertinence’ is abandoned and she rages about ‘The upstart pretensions of a young woman without family, connections, or fortune’.

Mr Darcy, of course, shares her haughtiness until he is taught some humility by Elizabeth.

It is intriguing that the aristocrats and even baronets in Jane Austen – unlike many in the genre of Regency Romance she inspired – are a generally unsympathetic lot. This may reflect her own conviction that the landed gentry – the class to which she belonged herself – were generally were more socially responsible and led more worthwhile existences, strongly connected as they were with the land and the local population.

It is notable that there are no aristocrats involved in the Gothic excesses of Emily Bronte’s ‘Wuthering Heights’, only the landed gentry of the Yorkshire Moors, as represented by the Lintons and the Earnshaws.

Aristocratic female antagonists seemed, intriguingly, to become less independently evil as the nineteenth and twentieth centuries went on, in popular fiction at least.

The siren Lady Barbara Childe in Georgette Heyer’s ‘An Infamous Army’ (1935) is seen as outrageous, but it wouldn’t be very hard to shock a society which gossips about a woman wearing polish on her toenails. She is also fond of taking drugs and breaking the hearts of admirers and rivals, but is really only an anti-heroine who repents at the end.

I remember being very impressed at thirteen by Princess Oonas Shahamalek in one of Dennis Wheatley’s novels, ‘The Quest of Julian Day’ (1937).

Small, but extremely voluptuous, she is still in her early twenties, though a widow, and a siren in the best tradition of Cleopatra, quite happy to enjoy and later callously to abandon lovers.

She is used by the villains of the piece to the seduce ‘Julian Day’. ‘Julian Day’ is in fact, a disgraced aristocrat whose real name is Hugo Julian du Crow Fernhurst, and an unofficial spy himself.

This encounter takes place in a desert tent in Egypt. The agreement is that after this bit of fun – which involves a game of catch with Princess Oonas only wearing a filmy nightdress and some intoxicating perfume – she will then have him murdered in his sleep. However, she finds him such a good lover that she decides to keep him alive after all for more of the same. Julian Day wakes up to hear her instructing her men that she has decided she likes him after all, and the murder is off. When the assassins arrive, she starts shooting at them.

Later, overcome with jealousy of another women on Julian Day’s proposed treasure hunting expedition, and unable to face the threat of losing him, as she sees it, to another, she traps him in a tomb, leaving him to die of thirst.

He escapes. Seeing him later, she assumes he is an evil spirit, and runs out into a sandstorm to a certain death. I assume Dennis Wheatley, who was a great believer in the Law of Karma, wrote this as part of its workings. I thought this was rather a shame. I much preferred her to her rival, Sylvia Shane, despite her treacherous nature. As a take on a ‘desert romance’ I definitely preferred that episode to the ‘He’s a Rapist, But I Love Him’ approach of ‘The Sheik’.

Of course, there are a large number of bad female aristocrats in modern fiction, especially in fantasy, but this post being about classic novels, I shall finish this post with the magnificently wicked Princess Oonas.

[image error][image error][image error][image error][image error]January 25, 2023

Brutal Barons and Caddish Counts: Aristocratic Villains in Popular Fiction

https://allthetropes.org/wiki/Aristocrats_Are_Evil

Here’s a very funny article about the wicked titled in fiction. Well, after the parliamentary expenses scandal of ten years or so ago, which unearthed appalling levels of politicians’ hands in the till in both the upper and lower chambers, perhaps these days it should be applied equally to life peers, promoted after a supposed life of service.

The wicked Sir Clement Willoughby making one of his countless attempts on Evelina’s virtue.

The wicked Sir Clement Willoughby making one of his countless attempts on Evelina’s virtue.It’s interesting, as the author notes, that generally Barons and Counts get such a bad press in classical English fiction. A good one is a rarity. Often they are lounge lizards, merely fortune seekers with questionable pasts, at worst, very evil if not in outright league with the Devil.

For instance, there is the Baron Adelbert Gruner Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes story, ‘The Illustrious Client’ (This is one of the later stories, being written in 1924, and like several of them, it does strike me has being more sensationalist than the earlier stories). Incidentally, with the acid throwing incident, I found this the most gruesome of the Sherlock Holmes stories.

This man is not only a philanderer and fortune hunter, but a wife murderer who got off on a technicality. His last wife very conveniently fell off the Spügen Pass in the Alps. He schemes to marry the said illustrious client’s daughter, who is totally captivated by him. However, Holmes finds out one weapon he can use against the scheming baron, and that is a book in his own handwriting, where he recounts his conquests…

Another wicked baron whose evil schemes come to grief at the hands of Sherlock Holmes is Baron Von Hering, the German diplomat and spy in the titular story of ‘His Last Bow’ (1917). He is a cardboard baddy, but the story is an entertaining read, presumably written to boost public morale during wartime.

Counts are generally depicted as being as bad as barons. The worst of them all, of course, is Count Dracula, who infamously gets fed up with the shortage of human prey in the Caparthian Mountains in Transylvania, and has his coffin transported to London. This being a piece of late Victorian (1897) gothic, the sexual element of the vampire legend remains only hinted at. In common with most very old people – he is hundreds of years old, though he doesn’t look it –the count likes to tell anecdotes about his youth, sometimes keeping his guest up all night.

Oddly enough, though Dracula is obliquely depicted as having a dark sexual allure, this infamous count has been married less times in his hundreds of years than many Hollywood film stars in middle age. He’s had a mere three brides.

English earls and lords are not necessarily seen as baddies. The heroes of most of Charles Garvice and Georgette Heyer’s romantic novels are earls, and while they might be wild and spendthrift, they usually are honourable and gallant.

Interestingly, in Heyer’s ‘The Infamous Army’ the hero’s rival for the dubious prize of Lady Barbara Childe (the granddaughter of the awful Marquis Vidal in ‘Devil’s Cub’) is a count of disreputable character. The Belgian Comte de Lavisse, however, shows his courage on the battlefield of Waterloo, besides his taste for histrionics. When his troops desert, he lays into them with his riding crop, shouting, ‘My honour is in the dust!’ He also carries the wounded hero off the battlefield, though he is frank enough to admit he regrets this when Lady Barbara Childe decides to marry him, rather than Lavisse. The caddish count must have bitterly resented being made to go in for this piece of self-sacrifice by his creator…

I mentioned the unpleasant Marquis Vidal anti-hero of Georgette Heyer’s ‘Devil’s Cub’ (1933), who goes in for a spot of attempted rape and strangulation by way of courting the heroine. He is in fact, the son of the wicked Duke of Avon, who however, avoided attempted rape if nothing else.

A Marquis, in fact, can be a highly sinister antagonist in Gothic fiction. For instance, in Ann Radcliffe’s 1790 novel ‘A Sicilian Romance’ , the fifth Marquis Mazzini is a very wicked fellow: he spends most of his time in the book trying to kidnap his own daughter to imprison her. He is following a precedent here, as he has kept her mother a prisoner for years in a tunnel. Still, he repents on his deathbed. I like it when antagonists do that. It is quite alarming how many modern writers share Hamlet’s attitude towards their baddies, and want them to die as sinful as possible.

Fictional baronets always seem to have been a shady lot. Perhaps they feel the need to take aristocratic assumptions of superiority and contempt for the lower orders to extremes; they could be over-compensating for the fact that they aren’t proper aristocrats and only halfway between commoners and peers. They are in fact, eligible to sit in the House of Commons. To get the general idea of their bad reputation, you only need think of the early example of Shakespeare’s Sir Toby Belcher in ‘Twelfth Night,’ (not as if parliament existed in those days, so he didn’t have that over-compensating excuse) or the ones who dodge shadily through the pages of popular novels and Victorian comic operas.

The wicked seducer Sir Clement Willoughby in Fanny Burney’s Georgian novel ‘Evelina’ seems to be an typical precedent. He pursues the virtuous Evelina without having any intention of marrying her, given her questionable status as the unacknowledged daughter of another caddish baronet – Sir John Belmont. He later openly admits this to Evelina’s ideal man, Lord Orville, whose intentions are in this- as in everything else – entirely honourable.

Lord Orville is, in fact, like a robot set up only to do the correct thing, whatever the circumstances. In that he is very like another equally two dimensional hero, Charles Darnay in Dickens’ ‘A Tale of Two Cities’. Darnay is really the Marquis St Evermonde since the murder of his uncle, who treated the peasants so brutally under the Ancien Regime that Darnay renounced his name and inheritance. After that, and his subsequent trial for treason by the British Crown, where he falls in love with the one of the witnesses against him, one Lucie Manette, he becomes robotic. Perhaps it is PTSD in his case, though what motivates Fanny Burney’s Lord Orville, apart from a desire to please his creator, is unclear.

Interestingly, dukes are fairly rare in popular fiction before the massive increase in Dukes in Regency romance (a know-it-all aside: there were never more than twenty-five dukes in the UK, including the royal dukes, with most of them then, as now, elderly). Unlike the Evil Marquis trope, they often feature as heroes rather than cads.

But this post is getting too long, so more of titled baddies and goodies in my next post.

[image error]December 30, 2022

New Year’s Resolutions for Writers

.

Hmm. Yes, well… I was meaning to say (and all the sort of things said by someone who hasn’t done what he or she said she would do).

New Year’s Resolutions for Writers is an uncomfortable topic for me, because I have yet to achieve one I make every year myself: That is, to write a simpler story which fits comfortably into a genre.

I have never done it.

If ‘Ravensdale’ was an Amazon best seller for weeks a decade ago, if ‘That Scoundrel Emile Dubois’ reached best seller status during sales, and later on, the same for ‘The Villainous Viscount’, then that was luck as much as anything. The plots of all of them are a bit too complex: they have non-commercial aspects (for instance, the length of ‘That Scoundrel Emile Dubois’). Because they don’t tend to confirm to the general requirements for a genre, they tend to disappoint reader expectations – and that, as Craig Martell comments, is a risky business: you only need look at some of the one star reviews for ‘Ravensdale’ in particular to see that.

Besides that, they don’t easily fit into a category, which makes marketing them difficult. I’ve written about this before, and I never seem to learn.

What is it that draws me towards cross genre novels again and again?

In a former post, I commented that some writers have in the past managed to get round this problem of being attracted to writing cross genre stories by creating a genre of their own.

Of course, that was in pre-internet days, when with less fierce competition, marketing such books was easier with the backing of a publishing company. Still, it can surely still be done without the backing of a publishing company: the problem is, how to think outside the box regarding marketing, reader expectations and the limited category options offered by online book publishing companies.

So, there’s my own repetitive New Year’s Resolution. I’d be interested to hear what writing resolution other writers have made.

It only remains for me to wish all readers of this blog – and of my books especially – a Happy New Year.

[image error][image error][image error][image error][image error][image error]December 18, 2022

The Music Room Ghost by Lucinda Elliot: A Short Story for Christmas

Lottie didn’t know when she first sensed the ghost’s presence in the music room at her aunt and uncle’s hotel. It must have been long before she saw her.

Of course, neither Lottie nor Magda believed in ghosts . Great Aunt Pauline did, but she went to a spiritualist church and generally had crazy ideas.

Lottie had always thought that ghosts must be bores, obsessed for centuries with some wrong done to them or that they had done to someone else. Then there was the ham acting, with their dragging about chains, or patrolling down corridors groaning, head under one arm like a fashion accessory.

There was the pure silliness of that stereotypical White Lady of Somewhere Hall who appeared at the stroke of midnight with the bodice of her gown soaked with blood where she’d been stabbed in the heart by her wicked husband who’d discovered her ‘in the arms of her lover’.

“En flagrante,” Magda had suggested. She had to explain the meaning to Lottie, who’d wrinkled her nose at the idea, supposing she’d got that term from those Charlotte Cray historical romances she’d got Lottie reading.

They’d agreed that a bloodstained white dress could be adopted by the ghost, to disguise that she’d been stark naked at the time she was caught.

On this dark late October afternoon, with the wind rising over the bay outside, Lottie repeated “En flagrante,” absently as, having finished those set exercises, she tinkled on the keyboard. For all the ghostly atmosphere – that sense that someone was watching her – Lottie still liked to sit here on the piano stool, doing a bit of half hearted practice. It got her off helping her aunt and Magda and the staff with the endless cooking and housework .

The hotel brochure might boast of ‘the experienced and friendly staff’ who helped Aunt Amanda run the hotel, but when she invited Magda and Lottie over‘for a break’ they ended up helping out every day.

Lottie could hear voices talking, quick footsteps and doors opening and closing in the kitchen quarters where the evening meal was being prepared. When her hour was up, they’d be yelling up at her to come down and find some extra plates, to dash out into the storm to pick some herbs from the herb garden, or to stir the sauce. Although Lottie had just turned sixteen, her aunt still tended to treat her as if she was an eager twelve- year- old.

From here, with the land between the front of the hotel and the cliff edge out of sight, you had the illusion that you were hovering between a sky and sea, azure on summer days, chill grey in winter. The waves below were flattened by distance, the yachts and boats the size of toys, while the clouds above the swooping gulls seemed within touching distance.

Lottie got up to move over to the great Regency windows. Now the remains of the meadow and the view of the bay with the rival hotels came into view, and down below the beach. On a wet and a windy autumn day like today, there were only a couple of people braving the weather. A youngish looking couple walked their dog and some old school fisherman sat obliviously on an upturned rowing boat, doing something to a net. He seemed oddly ageless.

A female voice said suddenly, “’En flagrante?’ Well, really! It scarcely becomes a schoolroom miss to be so precociously knowledgeable.” That voice would have been attractive had it not sounded so irritable.

Lottie jumped, but said at once, “It’s just my imagination.”

“I am so weary of hearing that,” the voice went on, speaking in the clearest of elocution mistress like voices. “The most unimaginative people claim that is what my voice must be. A vulgar, affluent travelling salesman said it, a while since. This the most unimaginative person you could meet, with a dreadful hail fellow well meet air. How it was I was visible to him, I cannot imagine..”

Lottie gawped. She thought about running, but decided against it. After all, she had known for a long time now that this room was haunted.

At first, the ghost had moved things. She would put down something, say her book of piano exercises, on the left of one of the side tables, turn about, and find that it had been moved over to the right. Sometimes a door would softly open and close. Lottie had rationalised that as changes in air pressure when a door being opened or shut somewhere else in the house. She had told herself that the pacing footsteps she so often heard in this part of the house were echoes. Still, there was that unaccountable scent of roses throughout the year.

After a while, the ghostly presence had started to sigh heavily now and then. Doggedly, Lottie told herself that was the wind.

Now, her voice wobbled as she tried to sound casual. “A travelling salesman? That must have been ages ago. They’ve died out.” She added helpfully, “I know one of my great-uncles was one.” She realised that she was gabbling irrelevantly.

She was staring about for the source of the voice, which remained hidden. Why was this? She’d heard somewhere of ghostly voices speaking with no sign of a body.

“Are you a ghost?” Realising that to the formal manners of a former age her question might sound what Aunt Amanda would call ‘brusque,’ she added, “Please.”

The voice made a noise which sounded like ‘Pshaw!’ and she felt a stir of chilly air at her elbow. “I prefer the term ‘spirit’. I suppose that is what I am.” The precise voice with the over-the-top received pronunciation sounded strained and impatient.

“Are you stuck here?” Lottie had never understood why anybody would choose to be a ghost. It sounded a boring existence to her. That was assuming an element of choice must come into it. She vaguely recalled Great-Aunt Pauline talking about spirits getting stuck between two worlds. She hadn’t taken much notice about how that came about.

The spirit said, “Do you mean by that, am I earthbound? Well, I suppose I am. I have been trying for a long while to unburden myself. I want people to know the truth about the scoundrel I married, but no-one will listen.”

“Oh.” Lottie was proud of her adult tact in keeping to herself her disappointment that marital squabbles seemed to dominate a female spectre’s afterlife. She knew too well how Aunt Amanda felt about Uncle Simon’s main contribution towards running the hotel being his socialising with the customers in the bar.

“Like the White Lady…” she realised something. “When did you die?”

She voice sounded offended. “My soul was separated from my body in 1809.”

“Six years before the Battle of Waterloo. ” Lottie felt proud of her grasp of history. “Have you been hanging about ever since then?”

She was still trying to catch sight of the ghost, who seemed to be moving about the room. She thought she saw a vague stir, like a slightly denser shadow, near the table with the antique violin case on it which was kept locked, the violin in it having a damaged bridge.

“Really, you have the most indelicate way of speaking for a young lady. And yet, you do not appear to be wholly insensitive, or you would be unable to realise my presence at all…Yes, since leaving that life I have been trying to summon people’s attention. Unfortunately, after the last heir was killed in some war with the Germans, the house stood empty for years.”

“Do you mean World War One?” wondered Lottie. “There was a worse war than that afterwards, the one my travelling salesman great- uncle was killed in.”

The voice sounded bored. “How unfortunate… Anyway, to return to my purpose: I want you to hear my story.”

Lottie generally liked hearing stories – as long as they weren’t dirty ones told by chortling boys at school –but realised how much she didn’t want to hear one from a ghost.

‘This shouldn’t be happening,” whined the rational part of her mind.

Downstairs, brisk footsteps sounded, and a voice called something, only to be cut off by a door slamming. Lottie suddenly realised how chill the room now felt and how much she wished that she was back in everyday, prosaic reality.

She glanced longingly at the music room door four metres away, thinking of making a dash for it. Absurdly, it was her upbringing – that upbringing that scorned the idea of ghosts – which stopped her from cutting off one of her elders in mid speech. After all, though the voice was that of a young woman, her ghost must be well over two hundred – far older than any of the old ladies here who demanded respect on account of their age.

Besides, if she gabbled some excuse and started to run, this ghost might turn nasty. It was hardly being good natured as it was. It might seize her with icy fingers, or perhaps cause the door to lock so that Lottie was trapped her with it. The very thought of that made her legs feel weak.

She mumbled, “It would be best if you talked to my uncle or aunt.” This was what she had always said to guests who asked her do things like turn up the heating, her aunt being oblivious to the icy draughts that found their way through the period windows in winter.

Lottie immediately saw how incongruous that idea was. Her aunt would be too busy thinking about the accounts or in planning next weeks’ menu to give a thought to spectral voices, while her uncle’s senses were usually blunted by a few whiskies by late afternoon.

The disembodied voice – now nearer to the window – sounded even more irritable. “You surely see the absurdity of my attempting to talk to either.”

Lottie – astonished at her own courage – fell back on a get out that she hadn’t demeaned herself by using in years. “But they are adults.”

She was disgusted by her whinging tone, but to her surprise, the ghostly voice softened, becoming almost coaxing. “It is indeed, unfair that you should be burdened with this at so young an age. Regrettably, I have little choice. I must relieve my mind by speaking out while I have the chance, or am I to be trapped here for ever?”

The question seemed to be rhetorical, thought it sent a nasty thrill through Lottie, who had a sudden dread that she might somehow become trapped likewise. No, she refused to believe that. For one thing, she wasn’t dead, or anyway, had shown no sign of dying when she was doing her piano practise a few minutes earlier.

Still, she saw that for now there was no escape. Shivering in the chill air, she tried to return to her blasé approach, which had been easier when it wasn’t so cold. “I suppose I have to listen like the wedding guest in that daft poem about the Ancient Mariner we did at school. At least if my aunt moans about my not doing my piano practice, I’ll have an original excuse: ‘A ghost stopped me.’”

The only response the spectre made to that was a chilly silence, though perhaps that was the temperature in the room. Seeing a throw draped over the sofa across the room, Lottie stumbled on shaking legs to seize it and drape it about herself. “Ah, that’s better.”