Barbara Shoup's Blog

August 20, 2020

It's Point of View, Stupid

I hate politics. Before 2016 I avoided reading or talking about it because it was either boring or depressing or infuriating. I thought, Catch 22: anyone who WANTS to be a politician is not qualified to be one because what wanting to be a politician really means is wanting power. I didn’t think all politicians started out that way, just that they inevitably became that way because of how it works. Lobbying, mainly. I’m not even going THERE because, well—I’m just not. I find it ironic that I’ve become a politics junkie because of Donald Trump. But isn't it sort of irresponsible not to be one, given what havoc he's wrought from Day One?

I still hate politics—and way, way more than I used to—but I have to admit I have become fascinated by how things have evolved. I keep thinking, you couldn’t make this shit up. And it gets curiouser and curiouser, as Alice in Wonderland said. Of course, I’ve become excessive about this. I’m excessive about everything. I’ve watched every bit of the Democratic Convention, so far. Actually, maybe THIS is what I wanted to write about. So, I’m thinking, wow, they’re doing a great job of presenting a picture of the variety of people and issues. Thinking, they should always do it this way. No more in-crowd conventions with people in idiotic hats, yelling and screaming as if they’re at a basketball game. And think of how much it costs to get all of those people there, pay for accommodations, media stuff. Not to mention the fucking balloons. All of which could be spent on—pretty much anything would be more worthwhile.

The in-crowd aspect of politics has always annoyed the hell out of me. Self-important people doing each other favors. Ugh. I know. I’m rambling. Maybe what I really want to write about is how I’m finding it harder to focus, to know what I want to say—even what can be said, because by the time you decide to speak, what you wanted to speak about has already changed. It’s nuts. I don’t step out into a cooling toward fall morning and feel that spark of energy I usually feel at this time of year, happy thoughts of school starting, leaves turning red and gold and orange, I think, Noooooooooo! It’s going to get cold and we’re all going to be stuck inside again.

And here’s something else, unrelated because that’s where my head is today. I was thinking of the rich diversity of people involved in the convention and feeling as good as I feel about anything these days and then I read this piece about how young people are pissed off because all the speakers are old and not progressive enough and other people are pissed off for who knows how many different reasons. OMG. The party of diversity is also the party of a gazillion often-conflicting points of view. To come together, each of us not only has to look objectively at what we want/hope, but also get inside a plethora of other people’s heads and do our best to see what they want/hope (and why)—then objectively, compassionately assess what’s possible right now, where to start—trusting that, eventually, we’ll get to everything that matters.

Can we do that?

December 20, 2018

Happy Birthday, Paul Klee!

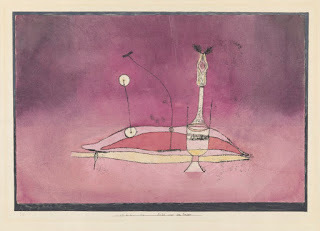

I love Paul Klee’s paintings, so simple at first glance that it’s not uncommon to hear the person next to you scoff, “A child could have done that!”

But if you look long enough, almost transparent dabs of burnt sienna and eucalyptus green might give way to long rectangles topped with triangles at the top of the canvas might become desert and a faraway walled city, so evocative that for a moment you’re standing in the hot dry air under the bleached sky. You can almost hear the muezzin’s call to prayer.

What first seems like a real thing—a crude black outline of a house with a tilted roofline set on a mosaic background of thousands of tiny squares—blue and orange, umber and red—might shift and suddenly become no more than a tilted triangle. In fact, the painting might actually be no more than a study triangles and almost-triangles. That single arch, the solid orange disc you thought was a sun when you thought the painting was a house, inviting only for their difference.

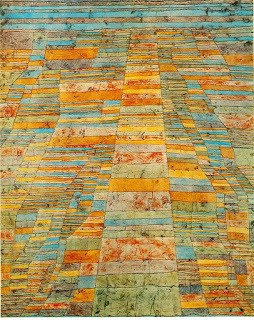

Then there are the countless color studies. Blocks of what seem like random color marching across a canvas. That’s it, you think. Just that. Until you look long enough to hear them singing.

The more I look at a painting by Paul Klee, the more I listen to the colors, the more I’m drenched with emotion, unbalanced by the intensity, the mystery of how color and shape can make that happen. The whimsy underpinned by strangeness and wonder.

Entering a retrospective of Klee’s work, I couldn’t wait to see room after room of his paintings, but what caught my eye when I walked into the gallery was a glass case containing an open sketchbook. Cool, I thought, expecting Klee’s sketchbook to reveal experiments with color, bits and pieces of patterns or images later incorporated into paintings. But what the open sketchbook revealed was a drawing of a farmhouse and the landscape surrounding it, so perfectly rendered that it might have been a photograph.

Turns out, Paul Klee had a degree in fine arts, and his passion for color led him to endless experiments in color and form. Over time, he developed his own color theory, which he taught to students at the Bauhaus.

Rules are made to be broken, artists often say. Which is true enough. The best of them broke the rules of preceding generations to create something wholly new—and which created a whole new set of rules for following generations to break. But, like Klee, the best of them had mastered those rules first. They broke them because what they imagined could not be contained in the old set of rules.

There are rules for writing fiction, too—guidelines we use to talk about aspects of the craft that must be mastered to write a good story. Occasionally, it happens, as it did to me, that someone writes a publishable first novel by some combination of instinct and dumb luck. But there were twelve years between the publication of my first published novel and the next one. I knew too much to repeat the dumb luck approach, and it took me all those years to understand the elements of craft well enough for them to become second nature to me.

January 26, 2017

Pink Hats, Privilege, Point of View

The other day on NPR's "Here and Now," there was a story about why so few Black women participated in the Women's March—a issue the host referred to as “intersectionality”—which is, I guess, how and where the multitude of issues and problems that need to be solved intersect.

(Yet another word to hate, but that’s a whole other post.)

I had been troubled by how few African-American women attended the Indianapolis event. It was obvious, looking at the photos, that the same was true of Washington and other cities. Reading a piece in the "New York Times" a while back about leaders of the March squabbling over inclusion, I thought, do we (meaning not only women) always have to argue about who’s in charge? I felt the same irritation upon learning it was the topic on “Here and Now.”

Then Ijeoma Oluo began to speak.

"I thought about [attending],” she said. “I gave it a lot of thought, and honestly, emotionally, it was really too hard. As the day became nearer, and I saw a lot of people who had never marched before, who had never marched with me before and with other people of color before, so excited to march for the first time, it became a really conflicting and emotional time, and it honestly wasn't something I could handle."

"It was wonderful to know that so many people were taking to the streets and were speaking out,” she said, “but if you are a person of color who has been fighting for black lives and brown lives, if you are a water protector who has been hosed down in Standing Rock, you have been begging people to stand next to you for so long. So, it can be hard to look at it and not wonder how many lives could be saved if we had even a tenth of these many people showing up at a Black Lives Matter march to push for police accountability and to push for reform. And that becomes hard because you can't bring people back from the beyond the grave."She wondered what the turning point was for these women, wondered why it hadn’t been watching any number of videos of young black men being murdered by the police."Where were they then?" she asked.Where, I wondered, was I?At which point, suddenly, I saw the Women's March through her eyes: the sea of white faces, the pink hats, the clever, in-your-face signs, the air of celebration and self-congratulation.

Finally! Women were going to rule the world!

Before our group left for the Indianapolis March on Saturday morning, my daughter shared a handout from UNITEWOMEN.ORG. with tips for what to do if the demonstration went bad. “I really don’t think anything’s going to happen,” she said. “But just in case, you might want to take a photo of this.” We did. But I was pretty sure we wouldn’t be in danger, and I’m guessing none of the other women—and for that matter, none of the millions of women who marched all over the country that day—did, either.

Because most of us were white--and if we weren’t white, we were surrounded by a wall of white privilege. Privilege, in this case, being the knowledge that there was no way the police were going to mess with a bunch of white women, many of whom were pillars of the community.

This hit me so hard I wanted to cry. “Oh, and about the hats,“ an African American friend of mine said, quietly, when I shared this story with her and told her how I felt. “My vagina isn’t pink.” Oh, my god, I thought. Everything, everything comes down to race in the end, whether it is intentional or an honest, if insensitive, mistake—and we are so completely nowhere on even confronting that problem, let alone solving it. Can it even be solved? Is a country whose grand experiment in democracy was built on the backs of black slaves and the genocide of its native people so skewed from the beginning that it can ever shed its sins and become a place where everyone is equal, everyone is free?Not if we don't acknowledge those sins, acknowledge where they are still alive among us. Not until all of us do everything we possibly can to see the world through the eyes of those who still suffer their lingering effects--and get a a small taste of what its like to be a Black person in this country.

January 20, 2017

Bea Kreloff, Artemesia Gentileschi, and Hope

Last Saturday afternoon several hundred people of all ages gathered in the gallery of the West Beth Artists Community to see an exhibit of Bea Kreloff’s work and to celebrate her life. She was nearly ninety-one when she died last fall. Who gets to that age and still has so many friends?

I met Bea in 2007 the day I arrived at Art Workshop International in Assisi. I’d never painted before and, as far as I could tell, had zero natural ability for it. But I like to write about painting and painters, and wanted to know where ideas for paintings came from, how they evolved, and how they were the same as and different from ideas for stories. I wanted to know what painting felt like. I’ve got to say, though, watching the taxi that had deposited me at the Hotel Giotto make its way back down the hill, I had a moment of sheer terror. I couldn’t draw, I couldn’t paint, and here I was among all these…artists. I was about to make a total fool of myself.

But there was Bea in the lobby—dressed in a voluminous black dress, her hair in a Louise Brooks bob. “You must be Barbara Shoup!” she said, and engulfed me. I felt, in that instant, part of the family of art. It was not a problem at all to Bea that I had no experience as artist. “Art is all around you,” she said. “Look. You’ll find it.”

I had expected, maybe, lessons. But she set me loose to discover my work with absolute confidence that I would find it. That day, wandering Assisi, anxiously wondering how in the world I was going to come with an idea, I came upon St. Francis’s cloak in a glass case in the Basilica museum. I looked at it for a long time—it’s simple design, its worn geometry of black and gray and white patches—marveling at the fact that he wore this, he walked the streets I’d walked to this place where I was standing. I bought a postcard, left. But I couldn’t stop thinking about it.

So I went back to the studio, enlarged the postcard, traced the pattern of patches on to a piece of drawing paper, opened my brand new tubes of acrylic paints, mixed up some colors, delighting in the feel of paint beneath my brush and—painted. I was happy. Lost, the way I’m lost, writing.

I loved what I’d made: my own vision of St. Francis’s cloak. But—like so many of my writing students—I felt I should apologize for being, well, a student. And wasn’t what I’d done sort of cheating?

“Absolutely not!” Bea said. “It’s wonderful. It’s art. You’re making art from what’s around you.”

I felt as if I’d just painted a masterpiece.

Bea always said, “Yes!” That’s what kind of teacher she was. Not that she wouldn’t also tell you what you needed to do to make your work better.

But here’s the story I really want to tell about Bea on this morning of Donald Trump’s inauguration, when I am feeling heartbroken about what our country is becoming.

It was told at Bea’s memorial by her long-time friend, Maria Louisa, a gorgeous Italian woman who owned a women’s bookstore in Rome that Bea discovered on her first trip to Italy in the 1970’s. A young Italian woman, an art history student, came into the store one day while Bea was there and asked about women artists during the time of Caravaggio. Were there even any, she wondered?

“Yes!” Bea said. “And one was better than Caravaggio.”

She got up, went to the art section and brought back books about Artemesia Gentilschi. Then she sat the young woman down and told her Artemesia’s story, enraged by how the world had treated this woman nearly four hundred years ago.

Her father, and artist and a friend and follower of Caravaggio, encouraged Artemesia to paint. At seventeen, she shocked the art world with “Susanna and the Elders,” breaking taboos in a time when women artists were only painting still life and portraits. She was raped when she was nineteen—and endured torture during the trial to avenge her family’s honor. Metal rings were tightened around her fingers, yet she told the brutal truth about the sexual assault. The rapist was found guilty, but never served his sentence.

Bea showed the young woman Gentileschi’s “Judith Slaying Holfoernes,” tapped her finger on the blade of the knife slicing his neck and said, “Who do you suppose she was thinking about when she painted that?”

The young woman was entranced. She bought the books about Gentileschi and left. Some months later, she returned to the store and asked for the American Woman. “Oh!” she said when Maria Louisa told her Bea didn’t work there. “I wanted to tell her that I’d done my dissertation on Artemesia Gentilischi.” Maria Louisa assured her that she would let Bea know.

“And there’s more!” Maria Louisa said, concluding her story at Bea’s memorial. “This same woman is one of the curators for the Artemesia Gentileschi exhibit right on at the Palazzo Braschi, in Rome.”

Such a small thing: a chance conversation in a bookstore. But it set the course for that young woman's life.

That's the kind of person Bea was. Wicked smart. So passionate about what she loved (and what she didn't), so engaged with the world around her, so generous of spirit. She made a difference in so many people's lives.

And that is what gives me hope on this dark day: one single person can change a life. Changed lives can change the world.

Gloria Steinem said, "The future depends entirely on what each person does every day; a movement is only people moving." So let's do it. Let's be smart, passionate, engaged, generous--like Bea was. Let's connect. Let's move. Let's take on the world, one by one by one by one by one.

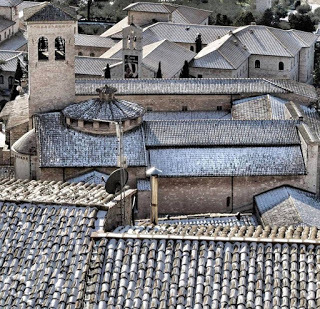

And if there is a heaven, let it be the Hotel Giotto in Assisi, Bea on the terrace at sunset with a glass of wine, looking out at the rooftops and towers of Assisi, telling stories, changing lives.

January 13, 2017

Hitler's Dollhouse

A couple of years ago, my husband and I visited Berlin. He’s a serious student of World War history; I’m fascinated by the war, too—maybe, in the beginning, for the simple reason that my mom was an English war bride and if there’d been no WWII I’d never have been born. Before we left, we read a wonderful series of thrillers by John Russell set in Berlin during the war years, which was fun because part of what we did while we were there was explore the stories’ geography, imagining the characters in the places we saw. Reporters hanging out in the Adler Hotel just beyond the Brandenburg Gate, spies meeting in the cafe at Zoo Station ,Nazi soldiers on guard at the Stadtschloss.

I love to visit the places I’ve read about in books that moved me deeply and shaped the way I see the world. Standing where real people or fictional people stood, seeing what they saw, understanding the boundaries of their existence in a visceral way enriches my imagination, and a deeper, more sympathetic understanding of what it means to be human settles into me.

I remember the preserved set of barracks at Auschwitz that showed the evolution from what looked like rustic (if crowded) cabins, one prisoner to a bunk and space for a table and chairs, to nothing but wall-to-wall shelves where prisoners slept head to toe. I remember standing in the space between the barracks and the administrative building, where prisoners were forced to stand, sometimes for hours, freezing in the winter, broiling in the summer, waiting to be counted or punished. I remember entering the gas chamber, never used, but—still. And the moment I looked at the opening of the oven where bodies were burned, realizing that bodies would have had to be handed it through it one by one—by a person, probably a Jew. Somehow I had thought it was less personal than that.

It’s the seemingly small things, like that oven door, that can create what feels like a cataclysmic shift in your understanding of history. Wandering through the German Historical Museum in Berlin, I came upon an exhibit of toys from the WWII era, among them a dollhouse-sized kitchen, its table set with tiny plates and beer steins, tiny bread and salami for the meal, a tiny red candle set into a tiny silver candlestick. There’s a white bowl of fruit on a sideboard, a cuckoo clock on the wall; flowered curtains trimmed with lace cover the windows. There’s a sink, a stove, a tiny vacuum cleaner.

The walls are papered with tiny images of Hitler Youth. Lined up, saluting; marching in pairs, bearing the Nazi flag; sitting around a campfire; hand-in-hand in a circle, playing some kind of game; at work, pushing a wheelbarrow, carrying sheaves of wheat. Between the two windows: a miniature photograph of Hitler in a silver frame; some kind of medallion with a swastika at its base.

I couldn’t stop looking at it, thinking— Someone had the idea to manufacture this dollhouse. Someone designed and manufactured this wallpaper for it. Someone shrunk and framed the photograph of Hitler to dollhouse scale. Someone made the mold for the medallion that hung on the wall. Someone bought it for his daughter. I imagined a blond, blue-eyed girl playing with it on the floor of her bedroom, the perfect Aryan doll family that surely came with it. Moving the mother, blond and blue-eyed like herself, to set the meal on the table; calling in her pretend-voice, “Vater, kommen Sie. Es ist Zeit zu essen.“ Picking up the father doll with her little fingers, arranging him in one of the chairs. Then “Kinder, du kommst auch,“ because there would certainly be a little blond boy doll and a little blond girl doll to join them, perhaps dressed in Hitler Youth uniforms, excited to tell their parents about the important work they’d done that day for the fuehrer.

Who isn’t horrified by the idea of Hitler Youth, the formal indoctrination of children in beliefs that resulted in terror, cruelty, and the death of more than six million people? I certainly am. But not as horrified as I was standing before this toy that had been designed to corrupt a child’s imagination, to turn healthy play into an exaltation the Nazi way of life, thinking about how many children grew up thinking this was perfectly normal.

I’ve been thinking a lot lately about how so many terrible things have begun to seem normal to us, and how dangerous that is: the kind of cultural change that happened in Germany didn't happen overnight, it evolved. It took a long time for German people to go from being maybe a little alarmed at Hitler’s message but still believing that nothing truly horrible would happen to book burning and death camps and manufacturing Hitler dollhouses for little girls.

I’m deeply troubled by the escalation of hateful, cruel, threatening, and exclusionary messages from the far right since the presidential election, fearful that we’ll wait too long to heed them, terrified what might happen if we do.

Children are hearing these messages, too, and it makes me worry about the games playing out in their fertile, unformed minds.

<!-- /* Font Definitions */ @font-face {font-family:"Courier New"; panose-1:2 7 3 9 2 2 5 2 4 4; mso-font-charset:0; mso-generic-font-family:auto; mso-font-pitch:variable; mso-font-signature:-536859905 -1073711037 9 0 511 0;} @font-face {font-family:"Cambria Math"; panose-1:2 4 5 3 5 4 6 3 2 4; mso-font-charset:0; mso-generic-font-family:auto; mso-font-pitch:variable; mso-font-signature:-536870145 1107305727 0 0 415 0;} @font-face {font-family:Calibri; panose-1:2 15 5 2 2 2 4 3 2 4; mso-font-charset:0; mso-generic-font-family:auto; mso-font-pitch:variable; mso-font-signature:-536870145 1073786111 1 0 415 0;} /* Style Definitions */ p.MsoNormal, li.MsoNormal, div.MsoNormal {mso-style-unhide:no; mso-style-qformat:yes; mso-style-parent:""; margin:0in; margin-bottom:.0001pt; mso-pagination:widow-orphan; font-size:12.0pt; font-family:Calibri; mso-ascii-font-family:Calibri; mso-ascii-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-fareast-font-family:Calibri; mso-fareast-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-hansi-font-family:Calibri; mso-hansi-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-bidi-font-family:"Times New Roman"; mso-bidi-theme-font:minor-bidi;} pre {mso-style-priority:99; mso-style-link:"HTML Preformatted Char"; margin:0in; margin-bottom:.0001pt; mso-pagination:widow-orphan; font-size:10.0pt; font-family:"Courier New"; mso-fareast-font-family:Calibri; mso-fareast-theme-font:minor-latin;} span.HTMLPreformattedChar {mso-style-name:"HTML Preformatted Char"; mso-style-priority:99; mso-style-unhide:no; mso-style-locked:yes; mso-style-link:"HTML Preformatted"; mso-ansi-font-size:10.0pt; mso-bidi-font-size:10.0pt; font-family:"Courier New"; mso-ascii-font-family:"Courier New"; mso-hansi-font-family:"Courier New"; mso-bidi-font-family:"Courier New";} .MsoChpDefault {mso-style-type:export-only; mso-default-props:yes; font-family:Calibri; mso-ascii-font-family:Calibri; mso-ascii-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-fareast-font-family:Calibri; mso-fareast-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-hansi-font-family:Calibri; mso-hansi-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-bidi-font-family:"Times New Roman"; mso-bidi-theme-font:minor-bidi;} @page WordSection1 {size:8.5in 11.0in; margin:1.0in 1.0in 1.0in 1.0in; mso-header-margin:.5in; mso-footer-margin:.5in; mso-paper-source:0;} div.WordSection1 {page:WordSection1;} </style> -->

January 7, 2017

Mary and Finn

A few nights ago, coming up the Harrietta Hill on the road between Cadillac and Caberfae Ski Area, we came upon a battered SUV with its blinkers on. Steve pulled up next to the driver’s window; I rolled down my window and asked if they needed help.

A few nights ago, coming up the Harrietta Hill on the road between Cadillac and Caberfae Ski Area, we came upon a battered SUV with its blinkers on. Steve pulled up next to the driver’s window; I rolled down my window and asked if they needed help.The man said they’d run out of gas.

No problem, Steve said. We’ll get you some gas.

There was a woman in the car, too, and a baby. It was cold, so we suggested that they come along. She brought the car seat, then the baby—and buckled him into it. She went back for the gas can.

“I’m Mary,” she said, closing the door. “This is Finn. He’s one and a half.”

We introduced ourselves, said we were from Indianapolis.

“Where’s that?” Mary asked.

“Indiana,” I said. “You know, just south.”

“Is it warm there?” she asked.

“Maybe a little warmer than Michigan, but not much,” I said.

They were from Manton, she told us, which we knew was about thirty miles away. They were on their way to pick up a friend who worked at the ski area because his car had broken down.

We chatted along the way. They had eight children between them, Mary told me. Finn was the child of a friend who they were raising as their own because she couldn’t care for him.

“You missed having little ones,” I said.

“Yeah,” Mary said, a smile in her voice. “I did.”

Fin was fitful, crying earnestly at times, then that tired, cranky kind of crying, then crying for his daddy. Mary soothed him.

When we got to the gas station, Steve said he needed to fill our tank (which he’d actually filled earlier that day), so there was no need for her to get out. He’d fill her gas can at the same time.

“Can I write you a check for that?” she asked, when he got back in the car.

“No,” Steve said. "Don't worry about it."

She thanked him quietly, we drove on back to the Harrietta Road in silence, but for Finn’s moaning, “Daa, Daa, Daa.”

We pulled up in front of the SUV and Mary got out, unbuckled Finn, and handed him through the open window to her husband, a gargantuan, bearded guy, who engulfed him. She put the car seat back into their car, then went back for the gas can.

“Are you guys going to be okay?” Steve asked.

Her husband nodded. He put a happy Finn up to the open window. “These are good people,” he said.

And we went on our way, back to our cozy cabin, to our dog and our books and a fire.

"We're so lucky," I said.

Steve agreed.

The thing is, though, if you asked Mary I'm pretty sure she’d say she was lucky, too. She loved her husband, loved her children. Times were tough, but—

I keep thinking about them. They had to know how low their gas tank was and how few gas stations there were in the thirty miles between home and their destination, yet they set out to pick up their friend, who needed help. They were several miles from the ski area when we came upon them. It was icy and dark so walking there was unlikely—not to mention dangerous. I have no idea how long they sat there, getting colder and colder. Almost nobody travels that road, especially at night.

My point? I wish I knew. I keep thinking a lot about Trump voters, who they are, how they live. Why they chose him. Were Mary and her husband Trump voters? Did they even vote? I don’t know. But I suspect that there are a lot of Trump voters who are like them, living on the edge, doing the best they can.

The gas can: one of those “telling details” fiction writers talk about. People don’t carry a gas can when they have enough money to fill up the tank when it nears empty.

When I was a kid, my dad would put a dollar or two, at most, in the tank. I thought everybody did that. Only rich people told the gas station attendant, “Fill ‘er up.” I couldn’t imagine what that would be like.

Now I hop out of my car, fill up the tank without a second thought. But I don’t ever want to forget how many people can’t do that. It seems like a small thing. But the world is made of small things, which, when put together so often make a picture that will break your heart.

March 3, 2016

Remembering Harper Lee

I’ve been living in Harper Lee’s world lately to prepare for a library talk I gave last week about To Kill a Mockingbird and Go Set a Watchman. I reread both books, watched the film, and saw Indiana Repertory Theatre’s production of “To Kill a Mockingbird.” I read Mockingbird: A Portrait of Harper Lee, by Charles J. Shields, and The Mockingbird Next Door, Marja Mills’s memoir about her friendship with Harper Lee.

I’ve been living in Harper Lee’s world lately to prepare for a library talk I gave last week about To Kill a Mockingbird and Go Set a Watchman. I reread both books, watched the film, and saw Indiana Repertory Theatre’s production of “To Kill a Mockingbird.” I read Mockingbird: A Portrait of Harper Lee, by Charles J. Shields, and The Mockingbird Next Door, Marja Mills’s memoir about her friendship with Harper Lee. I thought a lot about Lee’s struggles with her first novel, Go Set a Watchman, which she never got right, and her struggles with To Kill a Mockingbird, which she go so right that it catapulted into the fame and fortune that most writers dream of—and stopped her in her tracks.

I thought about a 2005 conversation Lee had with a waiter at a party in New York, described near the end of Shields’s biography. “Why didn’t you write another book?” the waiter asked.

“‘I had every intention of writing many novels,’” Harper Lee reportedly said, ‘but I never could have imagined the success To Kill a Mockingbird would enjoy. I became overwhelmed.’”

In the concluding paragraph of his biography, Shields wrote, “Rather than allow herself to be eternally frustrated, she ‘forgave herself’ and lifted the burden fro her shoulders of living up to the book. She refused to pressure herself into writing another novel unless the muse came to her naturally.”

But the muse nevercomes naturally. Writing isn’t about inspiration; it’s about addiction, obsession. The muse is knowing and needing the way writing will take you away from the real word into a world of your own making, one you have the power to shape and control.

Harper Lee knew this.

In 1964, still struggling with the second novel she never produced, she described herself to an interviewer as someone who must write. “I like to write,” she said. “Sometimes I’m afraid that I like it too much because when I get into work I don’t want to leave it. As a result I’ll go for days and days without leaving the house or wherever I happen to be. I’ll go out long enough to get papers and pick up some food and that’s it. It’s strange, but instead of hating writing I love it too much.”

She spoke about the novels she hoped to write, books that would “…leave some record of the kind of life that existed in a very small world…to chronicle something that seems to be very quickly going down the drain. This is small-town middle-class southern life as opposed to the gothic, as opposed to Tobacco Road, as opposed to plantation life.”

“In other words,” she concluded, “all I want to be is the Jane Austen of south Alabama.”

The sad thing is, she could have been.

In the sixties, a promising writer, one whose first novel had received excellent reviews but sold only moderately well, would have been nurtured by her publisher. If she needed money to pay the rent so that she could get that second novel written, money would magically appear. Her editor would be on call in the case of any crisis or confidence, instantly available for lunch or dinner or a drink to help calm the writer down, to reassure her that of course she would finish the book she was working on in time and of course it would be wonderful. The editor would truly believe this. She would believe it was her job to guide you through the long, harrowing process of birthing a novel.

It is its own kind of weird blessing not to be famous, not to have people waiting to see what you’ve written next, to judge if it is better or worse than what you’ve written before. It is its own weird kind of blessing to keep the carrot of recognition ever before you. Maybe, maybe the next novel will be the one that makes you a “successful” writer. When it’s not, well, you go at it again.

Harper Lee had an editor who believed passionately in her work and guided her through revision after revision of both Go Tell a Watchman and To Kill a Mockingbird. She had friends who believed in her so much that they gave her enough money to quit her job and do nothing but write for a year.

She knew writing was hard, that it was supposed to be hard. Shields described Lee’s 1966 response to a Sweet Briar College student who asked about her typical workday. “She said she stayed at her desk six to twelve hours a day and ended up with, perhaps, one page of finished manuscript.” Harper Lee told the class, “‘To be a serious writer requires discipline that is iron fisted. It’s sitting down and doing it whether you think you have it in you or not. Everyday. Alone. Without interruption. Contrary to what most people think, there is no glamour to writing. In fact, it’s heartbreak most of the time.’”

What might Harper Lee have written if “Mockingbird” hadn’t been a publishing phenomenon; if instead, good reviews and moderate sales had given her confidence as a writer, a manageable taste of recognition, the courage to go on?

What if she’d never had to occasion to say to her cousin, Dickie Williams, who asked the question she had surely come to dread, “Richard, when you’re at the top there’s only one way to go.”

In his conclusion to Mockingbird: A Portrait of Harper Lee, Charles J. Shields wrote, “A little more than a year after To Kill a Mockingbird was published, Nelle wrote to friends in Mobile, ‘People who have made peace with themselves are the people I most admire in the world.’ From all indications, she seems to have done that.”

I so hope he’s right. But I wonder.

And now we’ll never know.

Published in NUVO Newsweekly March, 2016

February 17, 2016

Between the World and Me

Early in Between the World and Me, a memoir addressed to his fifteen year-old son, Ta-Nehisi Coates writes, “I tell you now that the question of how one should live within a black body, within a country lost in the Dream, is the question of my life, and the pursuit of this question, I have found, ultimately answers itself.”

Between the World and Me is the story of Coates’s questioning, as a fearful boy in the brutal streets and failed schools of Baltimore; as a young man in the library at Howard University, Mecca to young black scholars; as an adult, an anxious father, doing the best he can to raise his son to be real and free in a country where the lives of black boys become increasingly expendable.

In the process, he addresses the paradox at the root of America’s long history of racial strife: our country, whose Constitution declares freedom and equality for all people, was built on the backs of black people whose lives and bodies were and continue to be fodder for the American Dream.

“America understands itself as God’s handiwork,” Coates writes, “but the black body is the clearest evidence that America is the work of men.

The result of this is a legacy of visceral, constricting fear at every level of Black culture. Coates’s parents weren’t religious, so there was no retreat to the comforts and mysteries that so often sustain believers. They were strict, pragmatic, afraid. Coates remembers his mother holding his hand crossing a busy street, telling him that if he ever let go and got killed by a car she would beat him back to life. At six, he wandered away while visiting a local park; when his parents found him, his father reached for his strap. “Later I would hear it in Dad’s voice—” Coates writes. “‘Either I can beat him, or the police.’ Maybe that saved me. Maybe it didn’t. All I know is, the violence rose from the fear like smoke from a fire, and I cannot say whether that violence, even administered in fear and love, sounded the alarm or choked us off at the exit.”

Even wealthy, privileged Blacks suffer the consequences of the Dream. Coates tells the story of the death of a college friend, Prince Jones, at the hands of the police. Jones’s mother was a doctor, he was raised in an affluent community, yet he was stopped by the police for the same kind of vague reason that hundreds of young black men are stopped and all too often killed by the police: they were searching for a young black man who looked nothing at all like the young man they’d stopped and about whom they had no cause for suspicion…but he was there. The police officer who made the “mistake” was not prosecuted.

Early in the book Coates writes about his son’s reaction to learning that the police officers who killed Michael Brown would not be punished. “You said, ‘I’ve got to go,’ and you went to your your room and I heard you crying.”

Coates goes to his son, but does not comfort him because he felt to comfort him would be wrong. He doesn’t tell him that it would be okay, because he didn’t believe it. What he tells him was what his own parents had tried to make him understand when he was the same age: “…that this is your country, that this is your world, that this is your body, and you must find a way to live within the all of it.”

Between the World and Me is the most honest, courageous, original, and heartbreaking book about race in America that I have ever read. It offers little hope. How could it, given the world as it is? There are no easy answers, either. How could there be when we can’t bring ourselves to ask the questions that matter?

About his own thwarted search for answers to the essential question of his life, Coates writes, “It began to strike me that the point of my education was a kind of discomfort, was a process that would not award me my own especial Dream, but would break all the dreams, all the comforting myths of Africa, of America, of everywhere, and would leave me only humanity in all its terribleness.”

May we all have the determination and courage to experience such discomfort in (finally) facing the real issues surrounding race in America. If we fail to do this, we cannot survive.

NUVO Newsweekly February, 2016

January 20, 2016

Hooray for Writers Who Are Alive!

A cemetery is a good place for young writers to visit because it is about dying, and anything about dying is about living as well. It is useful to wander among the graves of those whose lives are over. To feel grateful that you are still here, living the story of your life and turning it into words. So over the twenty years I taught creative writing at the Broad Ripple High School Center for the Humanities and the Performing Arts in Indianapolis for twenty years, we took an annual field trip to Crown Hill Cemetery. This was when you could still take kids in your car and kids with cars of their own could drive themselves, so we’d caravan across town, wind our way up to the James Whitcomb Riley grave, the highest point in Indianapolis. I’d spread a red-checked tablecloth on the big marble slab, start up the mix tape on my boom box: “The Not Necessarily Grateful Dead,” songs by performers no longer with us, and we’d eat our picnic lunches. From where we sat, the city we lived in looked like Oz.

To be honest, though, I did not choose JWR’s grave as the site for our excursion to celebrate his (in my opinion, dreadful) poetry. I chose it for irony’s sake. (Really? He’sthe Indiana writer with the gargantuan monument?) I’m embarrassed (and annoyed) that all too often his name is the first one mentioned when the subject of Indiana writers comes up. Okay. He’s part of our history. I get that.

So are a lot of (wonderful) dead Indiana writers.

But in my writing classroom, we studied Indiana writers who were alive. So many talented young people flee the state as soon as they can. I wanted my students to know that literature made of the stuff of their own Indiana lives could be as rich and mysterious as lives led in more exotic places.

Now, as the Executive Director of the Indiana Writers Center, I try to spread that message around the state—and beyond. We all need to do a better job of celebrating Indiana writers, promoting their work so that theirs are the names that come up when conversation turns to Indiana literature. Thanks to an Indiana Masterpiece Grant from the Indiana Arts Commission, the Writers Center has the opportunity to do just that with an anthology of contemporary Indiana writers to be published early next fall. Many accomplished Indiana writers have already agreed to be part of the project, including, Scott Russell Sanders, Susan Neville, Patricia Henley, Helen Frost, Karen Kovacik, and Michael Martone.

The book will be a “snapshot” of Indiana writers at the time of its 2016 Bicentennial. It will be launched with a series of readings, classroom visits, and writing workshops around the state.

But here’s the best part: the anthology will be appropriate for use in the high school classroom. It will be available online to English and writing teachers, along with curriculum materials designed to meet state standards.

While you’re waiting to read it, check out some of the writers mentioned above, if you aren’t already familiar with them. And here are some more I’m thrilled will be included: Shari Wagner, George Kalamaras, Greg Schwipps, Sarah Layden, Bryan Furuness, and Jim McGarrah.

Oh, and we don’t have a title yet. Any ideas?

November 16, 2015

Following the Brush

Yesterday I took David Shumate’s IWC class, “Following the Brush,” which was about where poems come from, how to cultivate the posture of the of the mind that invites them. We talked about the importance of letting your guard down in the first phase of writing a poem, messing around, not working toward a specific goals. "Think of yourself as a witness to the poem coming," Dave said. "Recognize that the poem has an intelligence of its own."

The early process is prelinguistic: impulse, image, development of a notion, he said. Not words. The proper state of mind is: I don’t know what to do with this. Let’s see where it goes.

“Follow the brush” is a Chinese term that describes this early process. The brush is the tool, the implement. It knows better than we do where to go. You have to allow the brush to emerge. This was a new term to me, one I like very much.

In this state, you are the “pilgrim of the poem,” a representative of the real “I.” The pilgrim disengages immediately from the “me,” allowing the pilgrim to discover vicariously what might happen. The pilgrim is utterly willing, naïve, stupid to go out on these pilgrimages in the first place. It disengages hesitance to let the “I” do things it wouldn’t actually down.

I like the idea of the poet as a pilgrim very much, too. And the idea that being in this state gives you entry to the territory of myth, where the ordinary world filtered through the prism of the imagination.

Early in the class, Dave asked us to describe where/how we get into the posture of mind that allows poems. I misunderstood, sort of, what he meant—and instead of describing my writing place, I tried to recreate how poems most often come to me (when they come, which I wish happened more often.)

Fall day, last leaves, yellow against the blue sky.I’m sitting in a glass building, consideringwhere poems come from and notice a dog outside--.red as the fallen leaves, straining against the leash.A woman in a blue jacket—blue—hurrying after him.It’s always blue that stops me. Blue movingAcross the landscape, becoming a poem.

Right now I’m thinking now about “blue.” The blue of the Italian paintings I love: the blue of the Madonna’s robe, the blue Italian sky. And “View of Delft.” Vermeer’s blue that captivated me for years. Early in the class, I said that when I write a poem it’s usually about something I want to own, to keep—but know I can’t. Looking at whatever it is the way I need to look to make a poem reconstructs that thing in my head in a way that makes me feel like I own it.

Which is, of course, what I’m always writing about: trying to keep, to hold something I love (a painting, a person, a time, a place). When the little poem (draft) came yesterday I thought it was the opposite of that: something totally random. Now I see it captured a moment that trigged a few thoughts about my own process that I wanted to keep:

1. Whatever blue is often delivers me to the posture of mind that invites a poem to come.

2. Dogs don’t need to write poems; they just are.

3. Which, (of course) paradoxically, puts the poet in the posture of mind that produces the brush to follow--then somehow, magically, become the brush herself.

4. Ergo: the poem on the page is made of who we are…when we aren’t.

These ideas aren’t new to me. But it was lovely to revisit them by way of a poet I deeply admire, such a delight to follow a brush that made them present themselves in a new way--and carry me to the holy place that invites poems (stories, novels) to come.