Alex Roddie's Blog

July 15, 2015

The Cape Wrath Trail days 18 – 20

The Cape Wrath Trail is a long-distance hiking route in Scotland. It links Fort William with Cape Wrath, the farthest northwest point of the British mainland. Renowned as one of the toughest long-distance walks in the UK, it is not waymarked, has no single recognised route, and there is frequently no actual path underfoot. Due to its informal nature, the length of this trail varies. Most thru-hikes are around 230 miles in length.

My hike of the Cape Wrath Trail took place between June the 3rd and June the 22nd 2015, and consisted of eighteen days of walking and two rest days. My route was 241 miles in length and was based on the itinerary laid out in the popular Cicerone guide by Iain Harper, with a few small modifications. I used the new Harvey Cape Wrath Trail maps for navigation.

The CWT is one of the finest foot journeys of its kind in the UK and takes the hiker through some magnificent wild locations. Its tough and frequently trackless nature makes the route I took potentially tricky in poor weather, requiring good navigational skills, a high level of fitness, and the ability to cope with hazards such as the crossing of swift-flowing rivers. But it's also truly magnificent. In this series of blog posts I will tell the story of my CWT adventure.

The Cape Wrath Trail trip report series

days 1 - 3 mile 0 - 38days 4 - 6 mile 38 - 65days 7 - 10 mile 65 - 115days 11 - 14 mile 115 - 167days 15 - 17 mile 167 - 203days 18 - 20 mile 203 - 241

DAYS 18 – 20 TRAIL MILE 203 – 241 (CAPE WRATH)

Day 18 – June the 20th18 miles

I woke that morning at Glendhu bothy to a gentle tapping sound. The light was streaming through the window but I saw moving shapes obscuring it, blurry through the layer of grime, and in a flash I was out of my sleeping bag to see what the hell was going on.

I stepped outside the bothy and was greeted by three wild ponies who had been nosing at the windows. The animals stood there in the ethereal morning light like mythical creatures from another world. Just another moment of magic on a long and magical journey.

Day 18 would be hard; I had to make it all the way to Rhiconich at trail mile 221. In between lay some of the wildest terrain in Scotland.

My day began by crossing the pass of Bealach nam Fiann, a good estate road crossing the lower slopes of Ben Strome. Despite the developed access track, beautiful wild terrain surrounded me and my mind lost itself in the complex tessellation of rock and water. But I also noticed a worrying pain in my left shin, more pronounced when hiking downhill.

Had I overstretched myself the previous day? It hardly seemed likely; after more than two hundred miles, I had my trail legs and, surely, the risk period for overuse injuries was well past.

But it got worse. By the time I began the steep descent on the other side of the pass, I was wincing in pain with every step and hobbling along like a cripple, using my trekking poles as crutches. It only hurt when going downhill and could hardly be felt on the flat or when climbing. Was it shin splints? A sprain? I didn't know, but I realised it could threaten my ability to finish the trail.

Time to make some decisions.

There was a road ahead, stringing together a few remote settlements in the wilds. Curiously the option to give up still didn't occur to me – escape would have been difficult at this point anyway, but I was still thinking in terms of overcoming the challenges of the trail and making it all the way to Cape Wrath no matter what.

However, I would need to modify my plans. The guidebook recommended a very tough route over Ben Dreavie then through the wilderness beneath Sail Mhor and Foinaven, but a quick look at the map revealed that the road gave me an option to bypass these difficulties.

So I decided to take a road walking diversion. Perhaps my body needed an easy day to recover from the stresses of the trail.

The beautiful and mysterious Loch StackI started walking and soon settled in to a pace and gait that felt comfortable. My shin twinged on the downhill sections, but they were very gentle on the tarmac road. It felt galling to bypass this section of spectacular wildness, but the road walk wasn't so bad, and it felt good to be making a good pace for once.

The beautiful and mysterious Loch StackI started walking and soon settled in to a pace and gait that felt comfortable. My shin twinged on the downhill sections, but they were very gentle on the tarmac road. It felt galling to bypass this section of spectacular wildness, but the road walk wasn't so bad, and it felt good to be making a good pace for once.Some video I shot on the road walk:

https://youtu.be/0PuJ-3iffZE

The weather wasn't bad that day – cloudy, but it only drizzled on and off a few times. The midges were, however, out to get me with a vengeance. I actually had to walk with my headnet on during a particularly bad section.

Probably one of the most scenic roads in the UKThen I reached a junction in the road, and for the first time I saw a sign showing me just how close I was to the end of the line. It hit me like an electric shock.

Probably one of the most scenic roads in the UKThen I reached a junction in the road, and for the first time I saw a sign showing me just how close I was to the end of the line. It hit me like an electric shock. 'But I don't want it to end!'Road walking is tiring when you do it for mile after mile, and I was pretty knackered by the time I pulled in to Rhiconich at about 8 p.m (but, important to note, still entirely blister free). I was unable to resist the siren call of the bar; within minutes I had a pint of cold beer in front of me and was swapping stories of the trail with the bar staff.

'But I don't want it to end!'Road walking is tiring when you do it for mile after mile, and I was pretty knackered by the time I pulled in to Rhiconich at about 8 p.m (but, important to note, still entirely blister free). I was unable to resist the siren call of the bar; within minutes I had a pint of cold beer in front of me and was swapping stories of the trail with the bar staff.They had seen no other CWT hikers for a long time. What had happened to everyone else on the trail? I had no idea.

I left the bar after an hour to look for somewhere to camp. I eventually settled for a marginal pitch near the river, on a lumpy bracken field, and spent an uncomfortable night besieged by more midges than I'd ever seen in my entire life.

Day 19 – June the 21st12 miles

When I woke the next morning, the first thought that crossed my mind – after the 'Sweet Jesus, look at all those midges!' moment, that is – was that I only had twenty miles of trail left in front of me. And then I wondered what would happen when I got to the end. What did the end of the trail even mean? I'd been walking towards it all this time, and I still didn't know.

The beautiful Loch InchardThis was one of the easiest stages of the CWT and a final opportunity to draw breath before the grand finale. I had a gentle road walk to Kinlochbervie ahead of me, a resupply, then a final short hike to Sandwood Bay. I took my time and enjoyed the views. Fortunately the road walk the previous day seemed to have done the job and my shin no longer troubled me.

The beautiful Loch InchardThis was one of the easiest stages of the CWT and a final opportunity to draw breath before the grand finale. I had a gentle road walk to Kinlochbervie ahead of me, a resupply, then a final short hike to Sandwood Bay. I took my time and enjoyed the views. Fortunately the road walk the previous day seemed to have done the job and my shin no longer troubled me.

I'd originally planned to resupply at the London Stores, a place legendary amongst CWT thru-hikers, but it was closed due to the fact that it was a Sunday. I decided to press on to Kinlochbervie.

Kinlochbervie is a curious place – a fishing port that looks like it would be more at home in Scandinavia or the Arctic than the UK. It has the feel of a frontier town about it and the only general store is a Spar shop near the harbour complex. I had to wait for the shop to open so spent a couple of hours crashed out next to the bay, drying out my gear in the sun.

I also took the opportunity to try ringing through to range control at Cape Wrath to find out if any exercises were planned on the live firing range, but was unable to get through. When the Spar shop opened I made enquiries inside but nobody knew of any planned exercises.

Looks like the Mediterranean!After buying my supplies, I set off along the little coastal road leading to Sheigra and Sandwood Bay. I'd last come this way about six years previously on a sea cliff climbing trip. There were numerous newly built houses – holiday homes, I guessed – that I hadn't noticed on my previous visit.

Looks like the Mediterranean!After buying my supplies, I set off along the little coastal road leading to Sheigra and Sandwood Bay. I'd last come this way about six years previously on a sea cliff climbing trip. There were numerous newly built houses – holiday homes, I guessed – that I hadn't noticed on my previous visit. Amazing views everywhere

Amazing views everywhere

Looking back to KinlochbervieWhen I reached the car park for Sandwood Bay, I met two men walking towards me with backpacking rucksacks. I immediately recognised fellow CWT hikers and stopped for a chat. It had been such a long time since I'd seen anyone else on the trail that I had started to think I was the only one left.

Looking back to KinlochbervieWhen I reached the car park for Sandwood Bay, I met two men walking towards me with backpacking rucksacks. I immediately recognised fellow CWT hikers and stopped for a chat. It had been such a long time since I'd seen anyone else on the trail that I had started to think I was the only one left.These guys were southbound section hikers heading for Ullapool. They'd camped at Sandwood Bay the previous night after crossing over from Cape Wrath, and informed me that the terrain was relatively firm with few bogs. Music to my ears!

In contrast with most other sections of the trail, the path to Sandwood Bay was very busy with day hikers. I must have met a dozen or more people on the short section of well-drained path leading to the sea.

The weather took a turn for the worse, though, and unfortunately I didn't get much of a view as I descended towards the dunes.

My first view of Sandwood BayAs it began to rain, I spent some time looking for the best place to camp. Sandwood Bay is undoubtably the best wild-camping location on the entire CWT, with a huge variety of flat grassy pitches. I selected a sheltered spot amongst the dunes and topped up my water supply from the nearby freshwater loch.

My first view of Sandwood BayAs it began to rain, I spent some time looking for the best place to camp. Sandwood Bay is undoubtably the best wild-camping location on the entire CWT, with a huge variety of flat grassy pitches. I selected a sheltered spot amongst the dunes and topped up my water supply from the nearby freshwater loch.Unfortunately I didn't get the coveted Sandwood Bay camping experience of watching the sun set over the ocean. It chucked it down with rain for fifteen hours and I spent the evening in my tent.

Day 20 – June the 22nd8 miles

When I woke the next morning, I knew that I couldn't put it off any longer. This was my final day on the trail. Only eight miles remained between my wild camp and the farthest NW point of the British mainland.

But the sun was out at last, and I could enjoy Sandwood Bay at its best.

After walking across the beach I had a river to cross – actually a little deeper than I expected – then a sandy cliff to climb. From the top of the cliff I was thrust immediately into the rough and serious terrain of Cape Wrath.

The final stage of the trail is almost entirely trackless and offers the hiker a choice of route: stick to the coastline or plot a course further inland? I'd heard that the inland route was easier, so I picked that. The twinge in my leg seemed to have gone but I didn't want to take any chances this close to the end.

The terrain was bleak, open, largely featureless, and involved map-and-compass navigation right from the start. My first task was to locate the remote bothy of Strathchailleach.

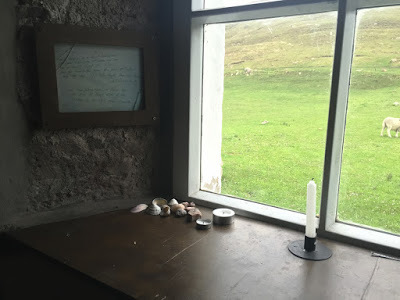

A typical Cape Wrath sceneStrathchailleach has a fascinating history and I was looking forward to seeing the amazing wall paintings left by its last permanent occupant, James McRory Smith. They didn't disappoint. Although I didn't stay the night in this bothy, it was a memorable place to brew a cup of coffee and spend half an hour.

A typical Cape Wrath sceneStrathchailleach has a fascinating history and I was looking forward to seeing the amazing wall paintings left by its last permanent occupant, James McRory Smith. They didn't disappoint. Although I didn't stay the night in this bothy, it was a memorable place to brew a cup of coffee and spend half an hour. The kitchen area

The kitchen area

The most colourful bothy in Scotland?Unfortunately it started raining again when I was at the bothy, and low cloud came back in with a vengeance. The bogs were pretty vicious on the line I ended up taking, too. It felt like the CWT was throwing everything it had at me right at the end.

The most colourful bothy in Scotland?Unfortunately it started raining again when I was at the bothy, and low cloud came back in with a vengeance. The bogs were pretty vicious on the line I ended up taking, too. It felt like the CWT was throwing everything it had at me right at the end.I set my compass and contoured around the hill. After a while I came across the barbed wire fence marking the edge of the live firing zone.

The CWT guidebook emphasises that it's very important to check with range control before crossing into the live firing zone. I had tried to phone through the previous day but got no response. Due to the hill fog, I could see no red flags flying on the fence, and I optimistically assumed everything would be fine. Over the fence I climbed!

Onwards. One more hill to climb and contour around, then a long, gentle descent through bog. I saw a hard-surface road in the distance leading around one final headland. My last navigational act of the trail was to set my compass due north.

When I reached the road, I met a sentry parked with a landrover. He told me that the RAF was about to commence bombardment in fifteen minutes! When I told him I hadn't seen any red flags he was quite good natured about it, and told me it would be safe to wait at the lighthouse until the all-clear was sounded at 4 p.m. He told me that I was allowed to stay at the Kearvaig bothy that night, but that I would have to be escorted to the edge of the exclusion zone the next morning. I got the impression this sort of thing was a regular occurrence.

So I began the final walk towards the end of the trail. I walked around the side of the last hill, and the lighthouse came into view.

I entered the courtyard in a daze. A minibus had just arrived with tourists to see the lighthouse, and when someone asked me where I'd walked from, I told him (truthfully!) that I'd come from Fort William.

The end of the CWTIt was an emotional moment. I walked to the edge of the cliffs and looked over, perhaps seeking an extension to the trail, but there was no more north. I had come to the end.

The end of the CWTIt was an emotional moment. I walked to the edge of the cliffs and looked over, perhaps seeking an extension to the trail, but there was no more north. I had come to the end. The rock of Cape Wrath: big, scary, but also beautiful. Rather like the trail itself.I went back to the odd little cafe in the outbuildings where I ordered a cup of coffee and leafed through the trail register. I saw a couple of familiar names in there, but it contained vanishingly few records of completion for the month of June – a far cry from the fifteen or so aspirant thru-hikers a week I'd heard about all the way back at Glenfinnan.

The rock of Cape Wrath: big, scary, but also beautiful. Rather like the trail itself.I went back to the odd little cafe in the outbuildings where I ordered a cup of coffee and leafed through the trail register. I saw a couple of familiar names in there, but it contained vanishingly few records of completion for the month of June – a far cry from the fifteen or so aspirant thru-hikers a week I'd heard about all the way back at Glenfinnan.The attrition rate that month had been brutal. But I'd survived the Cape Wrath Trail.

After the bombing had finished and the all-clear was sounded, I walked a few miles along the coast to the charming bothy of Kearvaig, which was to be my final bothy stay of the trip (and also the northernmost bothy in Scotland). It proved to be the best bothy of all, in a stunning location and lovingly maintained by the MBA.

KearvaigI watched the waves crashing on the beach and listened to the screech of gannets on the cliffs. I sat in the chair beside the window and thought about the amazing journey I'd experienced – the austere sublimity of life on the trail, the warping of time and space back to their proper dimensions, the evidence of things not seen. I knew the trail had changed me. And I think I understood at last what it meant.

KearvaigI watched the waves crashing on the beach and listened to the screech of gannets on the cliffs. I sat in the chair beside the window and thought about the amazing journey I'd experienced – the austere sublimity of life on the trail, the warping of time and space back to their proper dimensions, the evidence of things not seen. I knew the trail had changed me. And I think I understood at last what it meant.

“As long as I live, I'll hear waterfalls and birds and winds sing. I'll interpret the rocks, learn the language of flood, storm, and the avalanche. I'll acquaint myself with the glaciers and wild gardens, and get as near the heart of the world as I can."—John Muir

The Cape Wrath Trail trip report series

days 1 - 3 mile 0 - 38days 4 - 6 mile 38 - 65days 7 - 10 mile 65 - 115days 11 - 14 mile 115 - 167days 15 - 17 mile 167 - 203days 18 - 20 mile 203 - 241

Published on July 15, 2015 07:18

July 9, 2015

The Cape Wrath Trail days 15 – 17

The Cape Wrath Trail is a long-distance hiking route in Scotland. It links Fort William with Cape Wrath, the farthest northwest point of the British mainland. Renowned as one of the toughest long-distance walks in the UK, it is not waymarked, has no single recognised route, and there is frequently no actual path underfoot. Due to its informal nature, the length of this trail varies. Most thru-hikes are around 230 miles in length.

My hike of the Cape Wrath Trail took place between June the 3rd and June the 22nd 2015, and consisted of eighteen days of walking and two rest days. My route was 241 miles in length and was based on the itinerary laid out in the popular Cicerone guide by Iain Harper, with a few small modifications. I used the new Harvey Cape Wrath Trail maps for navigation.

The CWT is one of the finest foot journeys of its kind in the UK and takes the hiker through some magnificent wild locations. Its tough and frequently trackless nature makes the route I took potentially tricky in poor weather, requiring good navigational skills, a high level of fitness, and the ability to cope with hazards such as the crossing of swift-flowing rivers. But it's also truly magnificent. In this series of blog posts I will tell the story of my CWT adventure.

The Cape Wrath Trail trip report series

days 1 - 3 mile 0 - 38days 4 - 6 mile 38 - 65days 7 - 10 mile 65 - 115days 11 - 14 mile 115 - 167days 15 - 17 mile 167 - 203days 18 - 20 mile 203 - 241

DAYS 15 – 17 TRAIL MILE 167 – 203

Day 15 – June the 17th14 miles

During my stay at the Schoolhouse bothy the previous night, I'd been woken up several times by massive gusts of wind slamming into the side of the building and rattling everything inside. I also heard torrential rain hammering on the roof for hours. It was not a peaceful night.

The weather didn't improve in the morning. I packed up my belongings as slowly as I could, reluctant to venture outside and receive another soaking.

My original plan for days 15 and 16 had been to take the east route round the back of Ben More Assynt. This isn't the main route in the guidebook, but is presented as a wilder alternative stage for those who have no need for the amenities at Inchnadamph. I'd only been away from Ullapool for a day so had no wish to return to civilisation so soon.

But the weather was pretty bad – so windy and wet, in fact, that I knew at once all hopes of walking the harder alternative stage were pointless. I'd found it very difficult to locate suitable campsites on the CWT. It was almost impossible to find places that were flat enough, smooth enough, sufficiently well-drained, and sheltered – even satisfying just one of those conditions was often a struggle. I pictured myself trying to pitch the Notch in galeforce winds on some heathery ledge, or in the middle of a bog out of desperation, and knew I had to modify my plans.

So I made my mind up to tackle the pass of Breabag Tarsainn instead. First I had to make it along the length of Glen Oykel.

Typical Glen Oykel sceneryThe previous day had been less spectacular than an average CWT section, but Glen Oykel was the low point of the entire route. At the time, I remember feeling a little guilty that I could admit such a thing, but there you have it: combine rain with a long grind along landrover tracks, through miles of clear-felled forestry plantations, and it's going to compare poorly with all the amazing sections I'd passed through over the previous two weeks.

Typical Glen Oykel sceneryThe previous day had been less spectacular than an average CWT section, but Glen Oykel was the low point of the entire route. At the time, I remember feeling a little guilty that I could admit such a thing, but there you have it: combine rain with a long grind along landrover tracks, through miles of clear-felled forestry plantations, and it's going to compare poorly with all the amazing sections I'd passed through over the previous two weeks.I didn't really mind the hard roads or the bad weather that much; what I didn't like was the constant reminders of civilisation. I'd passed through so much relative wilderness, where mankind's impact is everywhere but very subtle, and you can ignore it if you try. But in Glen Oykel I felt that nature was being held hostage and used by humanity on a horrible scale. It's no different to any other part of the British countryside, of course, but I didn't want to wake up from the dream – and there I saw reminders everywhere that the majority of human beings see nature as a resource to be exploited, not a priceless treasure to be defended.

I passed through industrial cattle farms and mile upon mile of felled woodland. Despite a few breaks in the weather, it was generally grim head-down walking in heavy rain, with some massive gusts of wind thrown in for good measure.

The River Oykel itself was the only part of that day's walk that I really enjoyed, but even that was tamed for the purposes of commercial fishing. And logging operations meant a convoluted and annoying diversion to the trail.

The only CWT trail marker I saw on the entire journey

The only CWT trail marker I saw on the entire journey

The worst bridge on the Cape Wrath TrailI spent an hour or two flailing around in bogs, thickets of heather, and trying to dodge "NO PUBLIC ACCESS! LOGGING OPERATIONS!" signs. It was not a high point of my CWT experience.

The worst bridge on the Cape Wrath TrailI spent an hour or two flailing around in bogs, thickets of heather, and trying to dodge "NO PUBLIC ACCESS! LOGGING OPERATIONS!" signs. It was not a high point of my CWT experience.Fortunately I was out of the worst of it soon enough and could see mountains in the distance. Although my mileage for the day had not been great, the weather was getting windier and I started to think about finding somewhere to camp. I was keen to draw a line under Glen Oykel and move on to better parts of the trail.

By this point the high wind was a serious cause of concern. I knew I had to find somewhere sheltered, so I spent some time in the forest off-trail looking for a suitable glade. Eventually I found just the spot: a grassy meadow in the curve of a burn, sheltered on all sides. It was actually a delightful campsite and the best wild camp of the entire trip. By the remains of a fire I could tell that others had camped there before.

Although I could hear the gale tearing over the treetops, hardly a breeze ruffled my flysheet and I slept better than expected.

Day 16 – June the 18th

10 miles

I awoke to a moment of pure magic: a swoosh and a flap of mighty wings, followed by the unmistakable yip! yip! yip! of a golden eagle. A shadow flitted above my tent. The king of birds had just swooped over my forest glade, but sadly I didn't catch a glimpse of it.

It was another morning of packing up inside the tent to avoid the rain outside for as long as possible. When I finally emerged, I found that the burn encircling my meadow had risen by about a foot overnight thanks to the rains.

Upper Glen Oykel – which is much, much wilder than the forested lands lower down – proved to be a brutal struggle and the hardest section of the entire trail since those early days through Knoydart. The weather was so bad that I didn't take my camera out all day, and I don't have a single photo from June the 18th.

Although I followed a good path for a couple of miles, it soon disappeared into the bog and I had to – you've guessed it! – follow contour lines and perform other navigational magic to get me to the summit of the pass in the terrible visibility. This was very much a 'compass-in-hand' day, and is one of the stretches of the CWT that will punish the unskilled (if they manage to get this far). It's incredibly easy to find yourself following vague tracks and accidentally climbing towards Dubh Loch Mor when you should be contouring much lower, following the rougher ground.

Despite the rainfall, the rivers weren't too bad in Glen Oykel although I did get pretty wet fording one of them; by this point in the trail I had given up on removing socks or rolling up trousers when wading rivers. The final climb to the bealach was steep, rough work, and by the time I reached the top of the pass I was absolutely soaked to the skin. My waterproof trousers had leaked badly and water had got under my jacket too. I was later to discover that about a litre of water had somehow penetrated my rucksack cover and pooled in the bottom of my pack. It was just one of those days when it's impossible to stay dry. And it was cold, too – at the top of the pass the rain briefly turned to wet snow.

The descent from the bealach, picking its way down the western slopes of Conival, was even tougher than the ascent. Visibility was as poor as I'd ever seen it during the summer months on a mountain, and it was very easy to miss the faint path that wove a stealthy way between crumbling cliffs. Lose this path and you'll find yourself in extremely serious terrain. On one occasion I found myself looking down a 100m+ vertical drop, wondering where the hell the path had gone.

When I made it past the cliffs there was another vast bog to negotiate, made confusing by complex contour lines. Fail to take compass bearings here and you could end up losing hours of time and a great deal of energy.

The crossing of the River Traligill was the most difficult moment of the day. This is a serious watercourse and, in the conditions, I had to take some time to select the right crossing point. I ended up traversing the steep rocky sides of a ravine as I contemplated several possible places, each of which looked worse than the last. In the end it came down to jumping between two rocks spaced further apart than I'd have liked – the consequences of getting the leap wrong would have been catastrophic – but it was either that or risk wading a torrent that could easily have swept me away.

I survived the river crossing and shortly afterwards met another walker, called Andrew, who was on his way down from Conival. Chatting to another human made me feel a little better after such a punishing crossing, and we promised to meet at the hotel bar that night.

When I got to Inchnadamph I knew at once that I would need a roof over my head that night. I was simply too soaked and cold to even contemplate camping, and I doubted I'd be able to find anywhere acceptable to camp anyway; every inch of ground was utterly waterlogged. After finding the bunkhouse and standing shellshocked and dripping on their doormat for a few minutes while I figured out that they were full for the night, I made my way to the hotel. Sod it, I thought; I'm checking in to the hotel. I need this.

The hotel was a haven. I was amazed that I had an entire room to myself with a bed, a chair, and a bath! Such incredible luxuries! After washing my clothes and sending them to the drying room, I had a bath and felt richer than any other human being on Earth. The staff of the hotel were friendly and welcoming, being used to thru-hikers, and after drying out I spent a few pleasant hours in the bar talking to Andrew, the other guests, and the barman.

The barman was an experienced hillwalker and knew all about the CWT, the Assynt backcountry, and the hardships of long-distance hiking. He told me that a number of CWT thru-hikers had passed through Inchnadamph that month, but nowhere near the fifteen a week I had heard reported at the start of the trail. In fact, he told me that many hikers had failed to claim resupply boxes sent to the hotel.

'A lot of hikers have dropped out this year,' he said while pouring me another pint of An Teallach. 'The trail is getting busier, but it's catching people out. And the weather hasn't helped either.'

I couldn't help but agree with him.

I hadn't intended any hotel stops when I started my hike, but in the circumstances a stay at the Inchnadamph Hotel was exactly what I needed. I didn't realise just how much the crossing from Glen Oykel had taken out of me until I collapsed, exhausted, in my bed not long after 9 p.m.

Day 17 – June the 19th

12 miles

I left Inchnadamph in improving (but still damp) weather, feeling considerably restored. I'd been looking forward to this section of the trail for a long time – it would take me through some splendid wild country, and past the 200-mile mark.

Leaving Inchnadamph on a good pathThe first few miles felt easy compared to what I'd dealt with the previous day. I climbed the hill rapidly and was soon making the final ascent to the pass of Glas Bheinn.

Leaving Inchnadamph on a good pathThe first few miles felt easy compared to what I'd dealt with the previous day. I climbed the hill rapidly and was soon making the final ascent to the pass of Glas Bheinn. The pass visible in the far distance

The pass visible in the far distance

My first glimpse of the wilderness beyondAt the top of the pass, the terrain made an abrupt change from open, scooped-out corries to far more complex and rugged topography. In the words of the guidebook, 'As you climb back out of Inchnadamph ... you're entering some of the best mountain country in the world.' It looked good, and it got better with every mile I walked.

My first glimpse of the wilderness beyondAt the top of the pass, the terrain made an abrupt change from open, scooped-out corries to far more complex and rugged topography. In the words of the guidebook, 'As you climb back out of Inchnadamph ... you're entering some of the best mountain country in the world.' It looked good, and it got better with every mile I walked. Dropping down to the magnificent canyon of the Leitr DubhA path took me through complex terrain to the cliffs near the top of Eas a'Chual Aluinn, the highest waterfall in the UK. I then dropped straight down steep ground next to a burn and crossed the river, which I then followed north towards Loch Beag. Leitr Dubh was simply majestic, a vertical-sided canyon through which waterfalls thundered – and no paths to be seen anywhere. This section of the trail represented the CWT at its very best.

Dropping down to the magnificent canyon of the Leitr DubhA path took me through complex terrain to the cliffs near the top of Eas a'Chual Aluinn, the highest waterfall in the UK. I then dropped straight down steep ground next to a burn and crossed the river, which I then followed north towards Loch Beag. Leitr Dubh was simply majestic, a vertical-sided canyon through which waterfalls thundered – and no paths to be seen anywhere. This section of the trail represented the CWT at its very best. Eas a'Chual AluinnAfter a while I caught my first view of the mighty waterfall. It astonished me. If I had thought the Falls of Glomach impressive, Eas a'Chual Aluinn made ten times as big an impression. In fact, the entire glen at that point felt more like an otherworldly landscape from Middle Earth than an actual location in Scotland.

Eas a'Chual AluinnAfter a while I caught my first view of the mighty waterfall. It astonished me. If I had thought the Falls of Glomach impressive, Eas a'Chual Aluinn made ten times as big an impression. In fact, the entire glen at that point felt more like an otherworldly landscape from Middle Earth than an actual location in Scotland.I felt a little like a hobbit questing through the wilds, and found myself humming the soundtrack to The Lord of the Rings as I walked.

Where freshwater meets saltwaterAt the outflow of the Abhainn an Loch Bhig river, I contoured around a small headland into Glen Coul, where I stopped for a few moments at the remote bothy. This is actually the location of the most remote war memorial in the UK. I could see it standing proud on a small knoll not far from the buildings.

Where freshwater meets saltwaterAt the outflow of the Abhainn an Loch Bhig river, I contoured around a small headland into Glen Coul, where I stopped for a few moments at the remote bothy. This is actually the location of the most remote war memorial in the UK. I could see it standing proud on a small knoll not far from the buildings.Onwards! I had one more headland to cross before I could call it a day. Mileage would, again, be low – but over such rough pathless terrain I had no quibbles with stopping early. I planned to stop at the Glendhu bothy a few miles to the north. I only had a few more days left on the trail, and wanted to enjoy my remaining time as much as possible.

Looking back to Leitr Dubh and the falls

Looking back to Leitr Dubh and the falls

Crossing the headland and looking towards Loch Gleann DubhThe headland proved to be pretty tough going – a steep landrover track to begin with, so steep that I doubted any vehicles could successfully climb it, followed by rough trails over moorland and through birch woodland that clung precipitously to the side of the mountain.

Crossing the headland and looking towards Loch Gleann DubhThe headland proved to be pretty tough going – a steep landrover track to begin with, so steep that I doubted any vehicles could successfully climb it, followed by rough trails over moorland and through birch woodland that clung precipitously to the side of the mountain.And I passed trail mile 200. Hurrah!

When I finally reached the bothy at Glendhu, I felt more than ready to call it a day despite only having walked twelve miles. It felt more like a Knoydart day – not quite as tough as the crossing from Glen Oykel, but challenging for different reasons. I got a fire going and dried out my shoes.

As I read the bothy book and picked out the scant few entries from the CWT hikers who had made it this far, it started to dawn on me at last that I would make it to Cape Wrath, and that the final moment of my adventure was rapidly approaching. I had less than forty miles left to walk to the farthest northwest corner of the British mainland. In a few days my life on the trail would be over.

In the next blog post I'll describe my final three days on the trail: a road-walking diversion due to injury, camping at Sandwood Bay, nearly getting bombed by the RAF, and the moment of triumph when I reached the lighthouse.

Tranquility at Glendhu bothyThe Cape Wrath Trail trip report series

Tranquility at Glendhu bothyThe Cape Wrath Trail trip report seriesdays 1 - 3 mile 0 - 38days 4 - 6 mile 38 - 65days 7 - 10 mile 65 - 115days 11 - 14 mile 115 - 167days 15 - 17 mile 167 - 203days 18 - 20 mile 203 - 241

Published on July 09, 2015 05:28

July 7, 2015

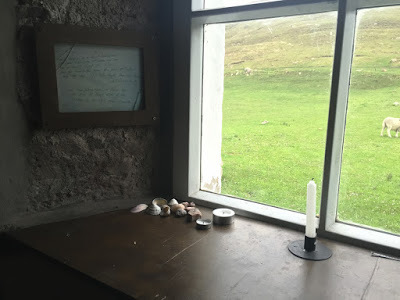

Feature on Professor Forbes and alpine glaciers in Mountain Pro Magazine

The July 2015 edition of Mountain Pro Magazine has now been published – an alpine special including articles from Jon Griffiths, Hendrik Morkel, and many others. My contribution is a feature on Professor Forbes and his 1842 journey through the Alps, specifically the Valpelline to Evolene section that I hiked a year ago.

In my article I explore the pass of Col Collon and examine the changes to the glaciers in that region since 1842. As I discovered, climate change has transformed the area almost beyond recognition.

Mountain Pro Magazine is free to read online. You can pick up the July 2015 issue here.

Published on July 07, 2015 13:48

July 6, 2015

Book review: Ruin by Harry Manners

Ruin (Book 1 of the Ruin Saga)by Harry Manners

Post-apocalyptic fiction is popular at the moment – so popular, in fact, that it takes a great deal for a post-apocalyptic story to stand out from the crowd. We've become well aquainted with zombie apocalypses, nuclear apocalypses, and more recently ecological apocalypses. What Harry Manners offers with his debut novel, Ruin , is something a little different.

Ruin tells the story of Great Britain in the aftermath of a cataclysmic event known simply as the End. For reasons unknown, the vast majority of Britain's population – and that of the world – completely disappeared, leaving no trace. Every electronic device also stopped working at that moment. The few survivors who remained found the world a very different place.

It's a story of brutal realities and conflict, but some great characters underpin the narrative. Alex, a visionary leader who aims to salvage what he can of the Old World and bring education and technology to the scattered people of Britain, is deeply conflicted but is regarded as something of a messiah by his followers. Then there's Norman, trained by Alex to eventually act as his successor, but Norman is plagued by feelings of insecurity and inadequacy. Alex's mission is a major driving force behind the plot. He has worked tirelessly for decades to keep the light of civilisation burning, but when famine devastates the land even that may not be enough. I did, however, feel that the female characters in Ruin were a little less well developed.

One thing I really enjoyed about this book is the sense of mystery and destiny that the author skilfully weaves into the narrative. There are more questions than answers at the end – an effective cliffhanger leading to the second book, Brink, although the novel works as a standalone.

It's a very British work of post-apocalyptic fiction. It's set in the British Isles, the characters are British, and many of its qualities succeed by being understated and subtle rather than overt. Although there's plenty of violence, Alex's principles of education and reform seek to change the world so that armed conflict is no longer necessary. There's a lot to admire in his lifelong mission to transform the lands, hold back the dark, against dwindling odds.

Harry Manners also writes exquisitely, with excellent dialogue and description. Less commonly amongst self-published books, the publication standard is of a very high standard of professionalism: smooth editing, flawless formatting and presentation, and one of the best covers I've seen in a long time.

I enjoyed reading this author's debut novel, and I enjoyed the sequel, Brink , just as much. If you like the post-apocalyptic genre then I think you'll love this great first book.

Buy Ruin on Amazon.com here, or Amazon.co.uk here

Visit the author's website@harry_a_manners on Twitter

Published on July 06, 2015 10:30

The Cape Wrath Trail days 11 – 14

The Cape Wrath Trail is a long-distance hiking route in Scotland. It links Fort William with Cape Wrath, the farthest northwest point of the British mainland. Renowned as one of the toughest long-distance walks in the UK, it is not waymarked, has no single recognised route, and there is frequently no actual path underfoot. Due to its informal nature, the length of this trail varies. Most thru-hikes are around 230 miles in length.

My hike of the Cape Wrath Trail took place between June the 3rd and June the 22nd 2015, and consisted of eighteen days of walking and two rest days. My route was 241 miles in length and was based on the itinerary laid out in the popular Cicerone guide by Iain Harper, with a few small modifications. I used the new Harvey Cape Wrath Trail maps for navigation.

The CWT is one of the finest foot journeys of its kind in the UK and takes the hiker through some magnificent wild locations. Its tough and frequently trackless nature makes the route I took potentially tricky in poor weather, requiring good navigational skills, a high level of fitness, and the ability to cope with hazards such as the crossing of swift-flowing rivers. But it's also truly magnificent. In this series of blog posts I will tell the story of my CWT adventure.

The Cape Wrath Trail trip report series

days 1 - 3 mile 0 - 38days 4 - 6 mile 38 - 65days 7 - 10 mile 65 - 115days 11 - 14 mile 115 - 167days 15 - 17 mile 167 - 203days 18 - 20 mile 203 - 241

DAYS 11 – 14 TRAIL MILE 115 – 167

Day 11 – June the 13th

18 miles

Leaving KinlocheweI left Kinlochewe early that morning, keen to make it across the wildernesses of Letterewe and Fisherfield to the bothy of Shenavall. Ever since I'd known what a bothy was, Shenavall had intrigued me – it's a remote shelter beneath the celebrated mountain An Teallach, and the focus of numerous stories and legends from 20th century mountaineering culture. It's one of those places with the glamour of magic about it.

Leaving KinlocheweI left Kinlochewe early that morning, keen to make it across the wildernesses of Letterewe and Fisherfield to the bothy of Shenavall. Ever since I'd known what a bothy was, Shenavall had intrigued me – it's a remote shelter beneath the celebrated mountain An Teallach, and the focus of numerous stories and legends from 20th century mountaineering culture. It's one of those places with the glamour of magic about it.But in order to get there I had to cross a big stretch of very remote and very wild land. The first section of the walk began easily enough, and for miles I strolled along flat landrover tracks that led from the village to the Heights of Kinlochewe, a tiny settlement at a fork in the track. I then followed similarly easy paths along the length of Gleann na Muice.

Easy walking for the first few miles

Easy walking for the first few miles

Regenerating forest near the Heights of KinlocheweThe trail may not have been as obviously exciting as the rollercoaster ride of Torridon, but I enjoyed this stretch. Easy paths underfoot allowed me to increase my pace, and the regenerating native woodland made a pleasant environment to walk through. The weather had definitely deteriorated, though – rain fell intermittently for the first couple of hours, and when I left the good paths and began the inevitable section of trackless cross-country navigation, cold winds and mists blew in from the north. The skies grew dark and stormy. A torrential downpour seemed imminent.

Regenerating forest near the Heights of KinlocheweThe trail may not have been as obviously exciting as the rollercoaster ride of Torridon, but I enjoyed this stretch. Easy paths underfoot allowed me to increase my pace, and the regenerating native woodland made a pleasant environment to walk through. The weather had definitely deteriorated, though – rain fell intermittently for the first couple of hours, and when I left the good paths and began the inevitable section of trackless cross-country navigation, cold winds and mists blew in from the north. The skies grew dark and stormy. A torrential downpour seemed imminent. The Letterewe wildernessGetting from the end of the path at Loch an Sgeireach to the Strath na Sealga involved navigating the pass of Bealach na Croise. The terrain was not particularly steep or rocky, but navigation proved to be a little tricky in the foul weather and I ended up wishing I had taken a compass bearing from the start. Something about the contour lines deceived my (usually excellent) sense of direction and I ended up on the wrong side of a small lochan, convinced I was facing north instead of east! I knew something was up when the terrain ahead didn't look as it should, however, and a glance at the compass set me back on course.

The Letterewe wildernessGetting from the end of the path at Loch an Sgeireach to the Strath na Sealga involved navigating the pass of Bealach na Croise. The terrain was not particularly steep or rocky, but navigation proved to be a little tricky in the foul weather and I ended up wishing I had taken a compass bearing from the start. Something about the contour lines deceived my (usually excellent) sense of direction and I ended up on the wrong side of a small lochan, convinced I was facing north instead of east! I knew something was up when the terrain ahead didn't look as it should, however, and a glance at the compass set me back on course.More contouring – I was getting good at that technique! – took me to the summit of the pass, but not before some truly monstrous peat hags had to be dealt with. On one occasion I found myself staring down a vertical bank of peat nearly ten feet high. Several lengthy diversions to avoid this and similar obstacles made the crossing of this pass take longer than expected.

On the other side of the pass, I started to follow a vague stalker's path on the left bank of a burn. It went the right way to begin with but after about half a mile I realised it was not descending, and I was at risk of contouring into one of the high corries of Mullach Coire Mhic Fhearchair – not at all where I wanted to be. So I abandoned the path and set a bearing for the river, splashing through the endless bogs and peat.

A very easy river crossingThe river crossing was trivial (the water didn't come far above my ankles) and I soon found myself standing on a path once again. The weather was poor by this point so I was pretty glad that the off-path section of that day's trail was at an end. All I had to do was follow the path north and it would take me to the Shenavall bothy.

A very easy river crossingThe river crossing was trivial (the water didn't come far above my ankles) and I soon found myself standing on a path once again. The weather was poor by this point so I was pretty glad that the off-path section of that day's trail was at an end. All I had to do was follow the path north and it would take me to the Shenavall bothy.It was, however, pretty rough as paths go: continuously waterlogged, often ploughing straight through massive bogs or eroded areas of peat. At times progress was so laborious that it was better to climb a little way up the hillside and traverse rough heather and scree. I started to realise that the arid conditions between Bendronaig Lodge and Kinlochewe had spoiled me a little! This was back to how things had been in Knoydart, without the complex topography and killer river crossings.

But I felt cheerful. I wasn't on the CWT for it to be easy. I wanted a challenge – if I had wanted easy walking on nice paths I would have done the West Highland Way. So I made what progress I could and I enjoyed the splendid, beautiful desolation of my surroundings.

The Strath na SealgaSoon enough the path joined another glen, the Strath na Sealga, where I started to notice evidence of human habitation (albeit none recent). There were stands of ancient trees that may once have been an orchard, a ruined cottage, and tumbledown stone enclosures near the riverbanks. In better weather that place would have been a paradise, actually – but the driving rain kept me walking on as fast as possible instead of standing for a while and taking in the view.

The Strath na SealgaSoon enough the path joined another glen, the Strath na Sealga, where I started to notice evidence of human habitation (albeit none recent). There were stands of ancient trees that may once have been an orchard, a ruined cottage, and tumbledown stone enclosures near the riverbanks. In better weather that place would have been a paradise, actually – but the driving rain kept me walking on as fast as possible instead of standing for a while and taking in the view.For the first time on the trail, I saw other lightweight backpackers. Someone had pitched a Trailstar in a sheltered spot by the river, several Hilleberg Aktos were standing amongst the dead oaks of the wood, and I saw another lightweight shelter I couldn't identify a little further up the glen. I had seen no other walkers all day; it seemed strange to see so many others now. I started to wonder if maybe the bothy was already full.

I didn't glimpse the bothy until I was almost upon it. This haven in the wild nestles beneath the buttresses of An Teallach, and from first glance it struck me as one of the most welcoming bothies I had ever visited. It's the only intact building amongst a number of ruins (another tent was pitched, weirdly, within the walls of one of them) and I increased my pace, eager to get warm and dry in front of the fire.

Shenavall, the legendary home in the wild

Shenavall, the legendary home in the wild

This was taken the following morning before departureI needn't have worried that the bothy would be full. It's pretty big as bothies go. One other person was in residence – Martha, a section hiker doing the CWT between Achnasheen and the Cape – but others soon turned up, and before long we had a fire and a merry gathering in the common room.

This was taken the following morning before departureI needn't have worried that the bothy would be full. It's pretty big as bothies go. One other person was in residence – Martha, a section hiker doing the CWT between Achnasheen and the Cape – but others soon turned up, and before long we had a fire and a merry gathering in the common room.It was a classic bothy evening. Altogether the company included four hillwalkers just down from the Fisherfield Six, two down from An Teallach, Martha the section hiker, and myself. Two different single malt whiskies were doing the rounds and we all chatted about mountains and mountaineering while our socks and shoes dried in front of the fire.

Martha and I compared notes on the trail. Although her planned route was very different to mine, we were both aiming to finish on about the same day and I wondered if I would see her again on my travels. I hadn't seen any other CWT hikers for nearly a week and I had started to miss the social aspect of the trail – the sharing of plans and ambitions, the telling of tales at each meeting. I'd had to make do with reading entries in the bothy books as I'd passed, but more and more names I had followed from bothy to bothy were starting to disappear as I moved north. I didn't know if they had left the trail or simply gone a different way. Hiking alone is great but I also found I enjoyed being a part of the nebulous CWT community.

At about 10 p.m. the rain finally cleared, allowing the sunset to pierce the bottom layers of the clouds for a few glorious minutes – just long enough for me to run outside with my camera.

Alpenglow on the mountains

Alpenglow on the mountains

The only sunshine I'd seen all dayIt had been a good day – tough in sections, but worthwhile. And I'd passed the halfway mark on my journey.

The only sunshine I'd seen all dayIt had been a good day – tough in sections, but worthwhile. And I'd passed the halfway mark on my journey.Day 12 – June the 14th

18 miles

I woke late that morning as my original plan was to walk the nine miles or so to Inverlael, then camp before tackling the road walk to Ullapool. By the time I got up the bothy was almost empty. Wood smoke still curled from the dying remains of the fire from the night before. I looked out of the window and saw glorious sunshine.

I had breakfast with Stephen, a Scottish hillwalker who had camped nearby the previous night but decided to move his things into the bothy before tackling An Teallach. When we chatted about our adventures he seemed incredulous that I had hiked over a hundred and thirty miles with a small pack and lightweight running shoes – it was simply outside his experience. His own pack was an 80-litre monster that I tried and failed to lift onto my shoulders. He said it had weighed 24kg before loading it with food and supplies!

As we talked, another hiker arrived at the bothy, also on his way to An Teallach. The newcomer was an American called Jamie, and in the conversation that followed a momentous event occurred: I was given my trail name!

Trail names are not commonly used in the UK but they are established on the long American hiking routes such as the Appalachian and Pacific Crest Trails. A trail name is essentially a nickname that you can either pick yourself or (more often) is given to you and 'sticks'. I'd simply been introducing myself as Alex to everyone I met on the trail but I had secretly wondered if I would acquire a trail name before completing the CWT.

This is what happened.

Stephen: 'This lad has walked all the way from Fort William wi' nae boots.'Jamie: 'No boots?'Stephen: 'Aye, just these flimsy trainers. Nae boots.'Jamie, looking at me: 'That should be your trail name, man. Naeboots.'

And so it was that my trail name became Naeboots! I didn't use it in person on the CWT – it would have felt weird – but I signed off my name as Naeboots in every bothy book from that point onwards. And, if I ever hike in the USA, that's what I'll call myself.

I soon packed and left the bothy, ascending behind An Teallach to an elevation of 400m. The views were absolutely stunning – and they remained that way for the entire day.

The view back to the Fisherfield wildernessThe route from Shenavall to the main road at Inverlael went over two passes: the first beneath An Teallach to Dundonell, the second over wilder moorland at a similar elevation. I enjoyed both passes tremendously. The first was wooded and ridiculously scenic, like a small portion of the Alps dropped into Scotland; the second was the usual combination of wide open spaces and endless bog/peat, but the views more than made up for it. And I was making good time.

The view back to the Fisherfield wildernessThe route from Shenavall to the main road at Inverlael went over two passes: the first beneath An Teallach to Dundonell, the second over wilder moorland at a similar elevation. I enjoyed both passes tremendously. The first was wooded and ridiculously scenic, like a small portion of the Alps dropped into Scotland; the second was the usual combination of wide open spaces and endless bog/peat, but the views more than made up for it. And I was making good time.

The CWT descending to Dundonell

The CWT descending to Dundonell

An TeallachThe views of An Teallach were stunning and a true highlight of the entire trail. I thought to myself that this is what all Scottish mountains should look like, clothed in trees and green nature, not stripped to the bone by millennia of human interference and devastated ecosystems.

An TeallachThe views of An Teallach were stunning and a true highlight of the entire trail. I thought to myself that this is what all Scottish mountains should look like, clothed in trees and green nature, not stripped to the bone by millennia of human interference and devastated ecosystems.  Uncharacteristically lush countryside on the second pass

Uncharacteristically lush countryside on the second pass

The crest of the second pass – spot the walkersThe descent to Inverlael was relentlessly steep and I was glad of my trekking poles as I slithered down muddy logging tracks. The views ahead were, again, gorgeous.

The crest of the second pass – spot the walkersThe descent to Inverlael was relentlessly steep and I was glad of my trekking poles as I slithered down muddy logging tracks. The views ahead were, again, gorgeous. InverlaelIt was early in the afternoon when I got to Inverlael, so I saw no need to camp. I set off north along the main road to Ullapool. This stretch of road is only about eight miles long, but in the heat and traffic it actually felt much longer. The guidebook recommends against tackling this roadwalk, except if you're a purist, but I had to resupply in Ullapool and was determined to walk every step of the way to Cape Wrath. Hitching or finding a bus was not an option!

InverlaelIt was early in the afternoon when I got to Inverlael, so I saw no need to camp. I set off north along the main road to Ullapool. This stretch of road is only about eight miles long, but in the heat and traffic it actually felt much longer. The guidebook recommends against tackling this roadwalk, except if you're a purist, but I had to resupply in Ullapool and was determined to walk every step of the way to Cape Wrath. Hitching or finding a bus was not an option!So I walked. After a couple of miles my feet began to hurt, and I stopped to have a look at them. To my surprise, both shoes had developed serious holes in the uppers – and, worse still, the rubber had worn alarmingly thin underneath the balls of my feet, with a few lugs worn completely down. The cushioning had also collapsed there. I started to wonder if my shoes would last the rest of the trail.

I was tired when I got to Ullapool, but the weather was sunny still and I found a sheltered pitch at the camping ground. The next day would be a zero.

Day 13 – June the 15th

Zero miles / rest day

There are worse places to spend a zero than Ullapool. It's a pleasant lochside town with every amenity the thru-hiker could wish for: supermarkets, pubs, restaurants, hardware stores, even a very good outdoor store. After buying supplies to last me to Kinlochbervie near the end of the trail, I made a visit to North West Outdoors in search of a new pair of running shoes.

Unfortunately they didn't stock Inov-8. The only lightweight mesh trail shoes they stocked were the Merrell All Out Peak. I didn't like the extra cushioning and flimsy mesh, but the fit felt ok so I bought them. Then I went to the post office and sent my Scarpa Spark shoes home (the Goretex shoes that had performed so poorly on the trail, and which I'd been lugging around as camp shoes ever since).

My strategy would be simple: wear the knackered Inov-8 shoes to destruction, then switch to the Merrells.

I ate well at the pub that day and spent time wandering around the town and exploring. It felt strange not to be hiking and, oddly, I felt more tired at the end of that day than I usually did after a day on the trail.

UllapoolDay 14 – June the 16th

UllapoolDay 14 – June the 16th16 miles

My route from Ullapool was not actually on the main CWT as described in the Iain Harper guide. It's presented as an alternative stage for hikers who chose to divert to Ullapool, and an easy stage before sterner stuff ahead. As I had no wish to walk or hitch back along the road to the main CWT route, I took the alternative stage via Glen Achall.

This was an easy stage, but also comparatively dull. Don't get me wrong, every day walking in the Highlands is better than a day spent at a desk, but I'd become used to hiking classic trails beneath legendary mountains, every mile a challenge and a pleasure. This was a long walk on landrover tracks through sheep farms and lowland estates. It was just one of those stages where you get your head down and walk.

Typical Glen Achall sceneryThe most exciting thing to happen all day was an off-path diversion to avoid a herd of cattle with calves on the advice of the farmer. I did, however, see large numbers of unusually tame deer very near to the road.

Typical Glen Achall sceneryThe most exciting thing to happen all day was an off-path diversion to avoid a herd of cattle with calves on the advice of the farmer. I did, however, see large numbers of unusually tame deer very near to the road.

The glen becomes a little wilder

The glen becomes a little wilder

The third worst bridge I encountered on the CWTThe weather remained dull and chilly as I walked. Gradually the terrain became less cultivated and more wild, and I made good time to Loch an Daimh. I spotted Knochdamph bothy and poked my nose in for a look, but found it creepy in the extreme – there was even an upstairs room with a rusty old Victorian bed still in situ!

The third worst bridge I encountered on the CWTThe weather remained dull and chilly as I walked. Gradually the terrain became less cultivated and more wild, and I made good time to Loch an Daimh. I spotted Knochdamph bothy and poked my nose in for a look, but found it creepy in the extreme – there was even an upstairs room with a rusty old Victorian bed still in situ! Near Loch an DaimhThe rain came down in buckets while I stopped in Knockdamph, so I took the opportunity to make some coffee and read the bothy book. Only a handful of CWT hikers had made entries.

Near Loch an DaimhThe rain came down in buckets while I stopped in Knockdamph, so I took the opportunity to make some coffee and read the bothy book. Only a handful of CWT hikers had made entries.But I wanted to get a few more miles in before I called it a day. I left Knockdamph in the rain and continued along the track, entering Glen Einig before long. Glen Einig reminded me of the Yorkshire Dales with its wide open sheep pasture and drystone walls.

Glen EinigThe Schoolhouse bothy was my stop for the night (although as usual I arrived early – still getting the hang of the logistics of the CWT!) It's a quaint little building that once served as a schoolroom, but the MBA renovated it some years ago and it now serves as an open mountain shelter. There was no fireplace, but it was a very snug little building and one of the smartest bothies I've ever stayed in.

Glen EinigThe Schoolhouse bothy was my stop for the night (although as usual I arrived early – still getting the hang of the logistics of the CWT!) It's a quaint little building that once served as a schoolroom, but the MBA renovated it some years ago and it now serves as an open mountain shelter. There was no fireplace, but it was a very snug little building and one of the smartest bothies I've ever stayed in. The Schoolhouse – it has two rooms

The Schoolhouse – it has two rooms

Expanding to fill the available spaceI read old copies of Wild Land News until it got dark, and went to sleep dreaming of wolves, forests and rewilding. The next day I would hike to Glen Oykel – a leg of the trail that looked easy on the map, but it proved to far more challenging than I expected in the deteriorating weather. Every day presents its own challenges on the Cape Wrath Trail!

Expanding to fill the available spaceI read old copies of Wild Land News until it got dark, and went to sleep dreaming of wolves, forests and rewilding. The next day I would hike to Glen Oykel – a leg of the trail that looked easy on the map, but it proved to far more challenging than I expected in the deteriorating weather. Every day presents its own challenges on the Cape Wrath Trail!The Cape Wrath Trail trip report series

days 1 - 3 mile 0 - 38days 4 - 6 mile 38 - 65days 7 - 10 mile 65 - 115days 11 - 14 mile 115 - 167days 15 - 17 mile 167 - 203days 18 - 20 mile 203 - 241

Published on July 06, 2015 01:01

July 2, 2015

The Cape Wrath Trail days 7 – 10

The Cape Wrath Trail is a long-distance hiking route in Scotland. It links Fort William with Cape Wrath, the farthest northwest point of the British mainland. Renowned as one of the toughest long-distance walks in the UK, it is not waymarked, has no single recognised route, and there is frequently no actual path underfoot. Due to its informal nature, the length of this trail varies. Most thru-hikes are around 230 miles in length.

My hike of the Cape Wrath Trail took place between June the 3rd and June the 22nd 2015, and consisted of eighteen days of walking and two rest days. My route was 241 miles in length and was based on the itinerary laid out in the popular Cicerone guide by Iain Harper, with a few small modifications. I used the new Harvey Cape Wrath Trail maps for navigation.

The CWT is one of the finest foot journeys of its kind in the UK and takes the hiker through some magnificent wild locations. Its tough and frequently trackless nature makes the route I took potentially tricky in poor weather, requiring good navigational skills, a high level of fitness, and the ability to cope with hazards such as the crossing of swift-flowing rivers. But it's also truly magnificent. In this series of blog posts I will tell the story of my CWT adventure.

The Cape Wrath Trail trip report series

days 1 - 3 mile 0 - 38days 4 - 6 mile 38 - 65days 7 - 10 mile 65 - 115days 11 - 14 mile 115 - 167days 15 - 17 mile 167 - 203days 18 - 20 mile 203 - 241

DAYS 7 – 10 TRAIL MILE 65 – 115

Day 7 – June the 9thZero miles / rest day

After a tough stint of hiking through the rough bounds of Knoydart, I'd been looking forward to my first rest day. Shiel Bridge made a natural place to pause: there's a shop to restock provisions, a pub for food and beer, and an excellent cafe just down the road (the Jac-O-Bite).

I made good use of my day off, baking damp gear in the sun, eating a massive Highland breakfast at the cafe, and replenishing my supplies. I decided that I would need three main meals (ended up getting Pasta-n-Sauce as usual), breakfast mix (muesli on this occasion, although I'd started the trail with a mixture of peanut M&Ms and trail mix), and trail food for two days. The small shop at the petrol station wasn't cheap but it had everything I needed.

The Sealskinz had leaked on day 4 but were still

The Sealskinz had leaked on day 4 but were stilla little dampDay 8 – June the 10th17 miles

I'd been looking forward to this leg of the trail for a while. I had arranged to meet my friend John Burns at the remote Maol-Bhuidhe bothy, and he'd promised to bring in fresh food and wine to save me from subsisting on dried rations all the time. Maol-Bhuidhe is 17 miles from Shiel Bridge, but with the considerably better weather and the promise of easier trails I felt very confident of being able to tackle the extra distance.

The walk began from Morvich, where a good trail led through mixed forest before striking off up the open hillside.

Pleasant walking from Morvich

Pleasant walking from Morvich

The path to the Falls of GlomachA straightforward climb and a crossing of open moorland led me to the top of the Falls of Glomach. Astoundingly, I'd hiked without getting my feet wet until that point – the dry weather and straightforward paths made an enormous difference, and I was flying along the trail compared to the slow pace I'd managed in Knoydart.

The path to the Falls of GlomachA straightforward climb and a crossing of open moorland led me to the top of the Falls of Glomach. Astoundingly, I'd hiked without getting my feet wet until that point – the dry weather and straightforward paths made an enormous difference, and I was flying along the trail compared to the slow pace I'd managed in Knoydart.I'd been looking forward to seeing the Falls of Glomach. It certainly didn't disappoint. The guidebook actually mentions that 'The waterfall here cascades more than 100m straight down into the ravine, the largest drop of any waterfall in the UK.' While it is more than 100m straight down (113m, in fact), it turns out it isn't the highest in the UK; that honour belongs to Eas a'Chuil Aluinn, over a hundred trail miles north.

Biggest or no, the Falls of Glomach was a highlight of the CWT experience. It's a little tricky to see from the top – you have to scramble down some rocky switchbacks to reach the best viewing platform, then climb back up to find the very faint path that traverses into the enormous canyon beyond.

The canyonHere's a short video I took from the viewing platform:

The canyonHere's a short video I took from the viewing platform:YouTube link

I enjoyed the canyon almost as much as the waterfall itself. The trail clung to the edge of precipitous cliffs, weaving a cunning route between rock outcrops and stands of woodland. There were a few boggy sections (and a knee-mashing descent) but nothing as rough or as challenging as Knoydart had been.

The trail then dropped down to Glen Elchaig where it took up a firm landcover track running east through the estate. What this section of the trail lacked in wildness it made up for in sheer speed and ease of travel. I made rapid progress through Glen Elchaig and soon I had begun the gentle ascent from Iron Lodge that would lead me into the much wilder lands to the north.

Loch na Leitreach in Glen Elchaig

Loch na Leitreach in Glen Elchaig

The remains of cornices on the east face of Faochaig (868m)This section of trail was a joy. With the landrover tracks of the lower glen behind me, I could enjoy the increased sense of open space and wildness yet still walk on good paths for a while. The sun was shining, I was feeling fit and strong, and before I knew it I had caught up with John at the crossing of a burn. We walked the rest of the way to Maol-Bhuidhe together.

The remains of cornices on the east face of Faochaig (868m)This section of trail was a joy. With the landrover tracks of the lower glen behind me, I could enjoy the increased sense of open space and wildness yet still walk on good paths for a while. The sun was shining, I was feeling fit and strong, and before I knew it I had caught up with John at the crossing of a burn. We walked the rest of the way to Maol-Bhuidhe together.

I'd known John for a couple of years but we had never actually met in person (a common state of friendships in the Twitter age!) We share a love of the Scottish peaks, an appreciation of bothies, and are both students of mountaineering history. John's interest in the history of the hills is expressed by writing and performing one-man plays including A Passion for Evil (about Aleister Crowley) and, most recently, Mallory – Beyond Everest (an intriguing take on the George Mallory story, featuring a much older character who survived Everest in 1924). He is also working on a book about his decades of experience in the hills.

We made good time to the bothy, which is located in the midst of a stunning area of wild land. Beautiful peaks surround it on all sides, many of which are only accessible by long walks – or a stay in the bothy itself. Two other hikers were already at the bothy with their gear spread outside, making a brew, and greeted us with cups of tea when we arrived!

Me at Maol-BhuidheThe stage was set for a memorable evening. The two hikers were backpacking south, gradually ticking off a number of mountains as they went, and in the long conversation that followed we found that all four of us had a lot in common: a shared love of the hills, of climbing and winter mountaineering, and we even knew many of the same places and people. Such serendipity is common in bothies, places where like-minded people gather and chat as if they've been friends for years, even if they had never met before. I've often thought that bothy culture is how all society should be. The world would be a happier place if more people treated their fellow humans as they do in bothies.

Me at Maol-BhuidheThe stage was set for a memorable evening. The two hikers were backpacking south, gradually ticking off a number of mountains as they went, and in the long conversation that followed we found that all four of us had a lot in common: a shared love of the hills, of climbing and winter mountaineering, and we even knew many of the same places and people. Such serendipity is common in bothies, places where like-minded people gather and chat as if they've been friends for years, even if they had never met before. I've often thought that bothy culture is how all society should be. The world would be a happier place if more people treated their fellow humans as they do in bothies.John had hauled in a veritable feast: fresh bolognese (made with bacon!), spaghetti, olive bread, pate, chocolate cake, and a box of red wine. The food was much appreciated and afterwards we all enjoyed a drink or two around the fire. John had also brought in a firelog, which burned for hours in the absence of other fuel. I loved my lightweight pack while hiking, but carrying in a few luxuries certainly has its compensations!

Day 9 – June the 11th16 miles

It was hot and humid when we emerged from the bothy the next morning. The two hikers were heading for the hills, John was heading home, and I had a few miles of rough bushwacking ahead of me. After saying farewell to my friends I began the day's walking.

Looking back to Maol-BhuidheThe first section of the CWT from Maol-Bhuidhe gave me a choice: go north of Beinn Dronaig or south. The north route has a path for more of its length but you have to cross a wire bridge. I don't like wire bridges; I decided to take the south route, which looked wilder on the map. I followed an unnamed river (an outflow of Loch Cruoshie) for some miles over rough and boggy terrain, loving the wildness of my surroundings, spoiled only by an ancient deer fence quietly rusting into the ground. After some distance I followed a rising traverse line (careful navigation required here) until the beginnings of a very faint stalker's path that led directly to Bendronaig Lodge. The terrain was rough but, again, I remember thinking this is nothing compared to Knoydart!

Looking back to Maol-BhuidheThe first section of the CWT from Maol-Bhuidhe gave me a choice: go north of Beinn Dronaig or south. The north route has a path for more of its length but you have to cross a wire bridge. I don't like wire bridges; I decided to take the south route, which looked wilder on the map. I followed an unnamed river (an outflow of Loch Cruoshie) for some miles over rough and boggy terrain, loving the wildness of my surroundings, spoiled only by an ancient deer fence quietly rusting into the ground. After some distance I followed a rising traverse line (careful navigation required here) until the beginnings of a very faint stalker's path that led directly to Bendronaig Lodge. The terrain was rough but, again, I remember thinking this is nothing compared to Knoydart!

Beautiful wild land south of Beinn DronaigI really enjoyed that leg of the trail. I think it perfectly captures what the CWT is all about: an adventurous cross-country backpacking route that requires good hill skills and fitness, visiting the best wild places instead of slavishly following the easiest paths.

Beautiful wild land south of Beinn DronaigI really enjoyed that leg of the trail. I think it perfectly captures what the CWT is all about: an adventurous cross-country backpacking route that requires good hill skills and fitness, visiting the best wild places instead of slavishly following the easiest paths.But it was a hot day, the hottest so far, and the heat took a little of the spring out of my steps. I took every opportunity to splash through clear running water to keep my feet cool.

'All this wilderness, and it's mine to enjoy!'Eventually I reached Bendronaig Lodge, an estate bothy of the Attadale Forest. I poked my nose in to have a look. It was the only bothy I have ever seen with a flushing toilet! I chatted to two cyclists who had slept there overnight, and they confirmed it was a comfortable place to stay.

'All this wilderness, and it's mine to enjoy!'Eventually I reached Bendronaig Lodge, an estate bothy of the Attadale Forest. I poked my nose in to have a look. It was the only bothy I have ever seen with a flushing toilet! I chatted to two cyclists who had slept there overnight, and they confirmed it was a comfortable place to stay. Bendronaig LodgeThe Attadale Forest was, as usual for the estates in the area, equipped with hard-track roads. I made rapid progress west before breaking away from the landrover track and climbing the pass of Bealach Alltan Ruaridh. The terrain suddenly felt different – conditions had been dry all day, but I noticed the terrain becoming far more arid as the geology began to change. I saw my first glimpses of the Torridonian giants on the horizon. It remained very hot.

Bendronaig LodgeThe Attadale Forest was, as usual for the estates in the area, equipped with hard-track roads. I made rapid progress west before breaking away from the landrover track and climbing the pass of Bealach Alltan Ruaridh. The terrain suddenly felt different – conditions had been dry all day, but I noticed the terrain becoming far more arid as the geology began to change. I saw my first glimpses of the Torridonian giants on the horizon. It remained very hot. The CWT just past the Bealach Alltan RuaridhBefore too long I was descending to Strathcarron where a drink in the pub (and half an hour on their wifi) restored me enough to contemplate another few miles to the bothy just up the glen.

The CWT just past the Bealach Alltan RuaridhBefore too long I was descending to Strathcarron where a drink in the pub (and half an hour on their wifi) restored me enough to contemplate another few miles to the bothy just up the glen.  The descent to Strathcarron

The descent to Strathcarron

A dry streambed – astonishing to think how wet it had

A dry streambed – astonishing to think how wet it hadbeen only days beforeI enjoyed the walk from Strathcarron to Coire Fionnaraich. A pleasant initial stretch along the riverside, through woodland, led to an easy climb on a good path that led into the heart of Torridon. Again, the terrain was everywhere exceptionally dry. I'd hiked with wet feet as far as Bendronaig Lodge, but my socks had pretty much dried out by Strathcarron and overall I think this was the driest day on the entire trail.

Looking back to Strathcarron