Jim Booth's Blog

May 14, 2020

Revisiting: Sinclair Lewis Imagines American Dictatorship: It Can’t Happen Here…Can It…?

“More and more, as I think about history…I am convinced that everything that is worthwhile in the world has been accomplished by the free, inquiring, critical spirit, and that the preservation of this spirit is more important than any social system, whatsoever. But the men of ritual and the men of barbarism are capable of shutting up the men of science and of silencing them forever.” – Doremus Jessup in Sinclair Lewis’s It Can’t Happen Here

One of the great fears one reads about these days is the use of the Covid-19 pandemic as cover for pushing the United States into fascism. I offer here a revisit to my essay on Sinclair Lewis’s classic about the rise of fascism in the US, It Can’t Happen Here as food for thought.

It Can’t Happen Here by Sinclair Lewis (image courtesy Goodreads)

It may seem strange that I choose to write about Sinclair Lewis’s dystopian satire, It Can’t Happen Here, for July 4th, the high holy day of the American ideal/experiment. Lewis’s novel is, after all, about the subversion of American democracy into a dictatorship. Worse, that dictatorship, is controlled by the leader of a political party called, presciently enough, The American Corporate State and Patriot Party. If ever someone seemed a political seer trying to warn us to consider the results of our actions, Lewis is that seer and It Can’t Happen Here is his warning. Published in 1935, the novel both reminds us of the complicated economic and political stresses of that time and, in an eerie way, reads (for anyone who has been paying attention over the last decade) like the playbook of – well, of both the “corporate citizen” and “patriot” movements within American politics.

For those who don’t know the work of Lewis (and, sadly, that will be far too many), his stock in trade as a novelist was the closely detailed, wittily sarcastic satirization of American life and culture. His masterpiece, Main Street, looks at the smug conservatism of American small towns; Babbitt is an indictment of bourgeois conformity and the practice of “boosterism” (called by another name today, but as rampant now as when Lewis wrote his novel); Arrowsmith, an inquiry into how science, specifically the practice of medicine, is affected by “expected” definitions of success; Elmer Gantry, his attempt to expose the hypocrisy of too many “big time” religious evangelists; and Dodsworth, a critique of the wealthy (whom Lewis found intellectually empty and self-absorbed). For this body of work Lewis became America’s first Nobel Prize winner in literature in 1930.

It Can’t Happen Here began life as an intended indictment of political demagoguery – in particular, Lewis intended to satirize “The Kingfish,” Louisiana governor and senator (and would-be US President) Huey Long. Long’s assassination in Baton Rouge, as well as Lewis’s growing concern as he learned more and more about fascism in Italy and Nazism in Germany changed the course of his novel – and It Can’t Happen Here was the result.

The plot of It Can’t Happen Here takes place in a near future (published in 1935, it covers the years 1936-39) and concerns a newspaper editor in the small Vermont town of Fort Beulah. That editor, Doremus Jessup, describes himself as “Liberal”: he supports a labor union in their strike for better wages and working conditions at a local granite quarry, for instance. But he admires fellow Vermonters Ethan Allen and Thaddeus Stevens, so his liberalism is of the independent minded Yankee sort. He watches first with curiosity, then with growing alarm, the rise of Berzelius Windrip, a senator from an unnamed state in the middle of the country. When Windrip is elected President on the Democratic ticket over a “Lincoln like” Republican Walt Trowbridge and a frustrated Franklin D. Roosevelt who has left the Democrats after failing to gain the 1936 party nomination and formed his own party (much as his cousin did in 1912 in his frustration with the Republicans), the decline from democracy to dictatorship begins in earnest. Windrip, who has campaigned on a platform much like Huey Long’s “every man a king” campaign strategy, upon inauguration begins to assume dictatorial powers and uses his private army, called Minute Men, who become increasingly militarized (any similarities between the “MM’s,” as they’re called and Hitler’s use of first the S.A., then the S.S. to enforce his political will is strictly intentional) as his muscle. Of course after his election, in the name of “security,” Windrip and his chief henchman, a sinister figure named Lee Sarason (a composite of Joseph Goebbels and Heinrich Himmler) outlaw all political parties except their newly created American Corporate State and Patriot Party (known as “Corpos” in the vernacular). Then, like any dictatorship, they begin a systematic program of repression and persecution of any who oppose their policies. Eventually the repression becomes so pervasive that even small town newspaper editor Jessup ends up in a concentration camp. Eventually, through the assistance of his lover, he is able to escape the camp and make his way into Canada where he becomes an agent for the counter-revolution led by that Lincolnesque figure I mentioned earlier, Walt Trowbridge. The novel ends on a hopeful, of somewhat unsatisfying note:

“And still Doremus goes on in the red sunrise, for a Doremus Jessup can never die.”

The focus on small town life suits Lewis well and plays to his strengths as one of the greatest chroniclers of that life. While keeping the bulk of the story in Vermont (there are a couple of brief trips to places like Boston and Hartford, and a digression in which Lewis brings readers – if not Jessup, who at that point is in a concentration camp that receives no news – up to date on the fate of the major Corpo characters) allows Lewis to explore how an emerging dictatorship might spread its tentacles over the nation, eventually infiltrating, co-opting, and controlling even small towns like Fort Beulah, VT, it separates us from feeling the evil of Windrip’s regime in a way that perhaps mimics our own separation from the evil that goes on, as we cavalierly term it, “inside the Beltway.” To give Lewis his due, that is certainly realistic. And given the times (and limits in communication, something we may forget given that we approach the book as readers now inured to a constant flow of information), the sometimes bucolic stretches of the novel balance the horrors that do eventually visit the Jessup family- Doremus’s son-in-law is ruthlessly murdered by Minute Men for “crimes against the state” (i.e., speaking truth to power); his daughter (the widow) eventually joins the Corpo Women’s Air Corps group and takes her revenge on the magistrate who ordered her husband’s death by flying her plane into one in which he is traveling – killing both him and herself; and Doremus, though eventually he escapes the concentration camp he has been sent to and voluntarily returns to Minnesota where he serves as a counter-revolutionary leader, loses (for all intents and purposes) his wife, his lover, his remaining children and grandchild, and his friends. Still, one can’t help feeling distanced from it all at times – as if Lewis himself is not completely sold on his premise – in truth, that he himself feels that “it can’t happen here.” In that, the novel falls a little short of its immediate predecessor, Huxley’s Brave New World and even more short of its successor, a work forged in the fiery furnace of World War II, Nineteen Eighty-Four.

* * * * *

In his Nobel Prize acceptance lecture, Sinclair Lewis bemoaned what he saw as an abiding fear in American literary efforts: “…in America most of us—not readers alone, but even writers—are still afraid of any literature which is not a glorification of everything American, a glorification of our faults as well as our virtues.” Ironically, perhaps that is what keeps It Can’t Happen Here from being a more widely esteemed novel than it is. Despite himself, Lewis’s Doremus Jessup, while he can criticize America’s failings, can’t help but praise America, especially its general indifference to even the most powerful social and political situations:

Blessed be they who are not Patriots and Idealists, and who do not feel that they must dash right in and Do Something About It.

And Doremus (and thus Lewis) can offer the following critique of American visionaries:

It is just possible…that the most vigorous and boldest idealists have been the worst enemies of human progress instead of its greatest creators? Possible that plain men with the humble trait of minding their own business will rank higher in the heavenly hierarchy than all the plumed souls who have shoved their way in among the masses and insisted on saving them?

So much for the Founders, Lincoln, Teddy and Franklin Roosevelt, Martin Luther King, et. al.

But Doremus learns – and this allows Lewis to lead readers towards (one hopes) similar epiphanies. Here, for instance, as the fist on the Corpo dictatorship closes around him, his family, his friends, his state, Jessup begins to understand how his “new order” is changing his little world:

Under a tyranny, most friends are a liability. One quarter of them turn ‘reasonable’ and become your enemies, one quarter are afraid to stop and speak, and one quarter are killed and you die with them. But the final blessed quarter keep you alive.

And Doremus learns – and Lewis tries to warn us – that when we lose the news, we lose the truth:

He could find no authentic news even in the papers from Boston or New York, in both of which the morning papers had been combined by the government into one sheet, rich in comic strips, in syndicated gossip from Hollywood, and, indeed, lacking only any news.

A wonderful thought experiment at this point would be to suggest that you leave this essay and go look at any of the news “services” – CNN, Yahoo, etc. But it can’t happen here, now can it?

And as with any system designed to perpetuate itself, re-education is a must:

They saw arising a Corpo art, a Corpo learning, profound and real, divested of the traditional snobbishness of the old-time universities, valiant with youth, and only more beautiful in that it was ‘useful.’

Lewis envisioned this coming from reconstituting higher education. It should be, then, duly concerning to contemporary readers that many of our “thought leaders” are suggesting that traditional educational systems can easily be supplanted by systems like MOOCs that “democratize” learning and force professors to be “competitive” and “entertaining” to survive in a “flat world.” This may indeed be, as Lewis calls it “useful.” The question that must be asked is – useful to whom?

So the Corpo dictatorship rises and establishes itself. But then wheels start to come off. Windrip, more a “glad hander” and demagogic orator than a leader, is deposed and exiled by his efficient (and highly decadent) lieutenant, Sarason – who is then eliminated (in the literal sense of the word in this political context) by the head of the military, a General Haik, who deals with dissent with Stalin-like efficiency. Haik, understanding the American psyche perhaps even better than his predecessors, adds a last element to the Corpo indoctrination methodology:

…there were also plenty of reverend celebrities…to whom Corpoism had given a chance to be noisily and lucratively patriotic….These more practical shepherds…became valued….For even for an army of slaves, it was necessary to persuade them that they were freemen and fighters for the principle of freedom….

Despite these efforts, despite attempts to crush dissent, eliminate dissenters, re-educate the populace through schools and churches, counter-revolution still comes – and the country splits. Doremus Jessup, who has suffered much under Corpo tyranny, joins the “enemy” and the novel ends with Lewis’s claim that men like Jessup – “real Americans” – will always exist – that there will always be those who are willing to risk their lives for real freedom – not some version of it presented as security or comfort or peace though perpetual war.

Let us hope that Lewis is right about that.

May 7, 2020

A Little Light Reading for These Secluded Days

Back in 2018 I ran out of gas – the current government had gotten on my last nerve, and my refuge, reading and writing about what I read, sort of failed me for awhile. I went back into playing music (still very much doing that – working on a solo album right now with the aid of my sons, former members of the band Doco) which gives me a lot of solace. Bought what is probably my last instrument – a bucket list buy, a Rickenbacker 4003 bass. I’ve owned and played lots of basses – started with a 1968 Vox Sidewinder, moved on to a 1969 Fender Telecaster bass (yes, it had the psychedelic flowers on it), then on to a Gibson EB-3 with slot neck tuners, then a few more I won’t list (I realize the only people still reading at this point are other musicians, well, bass players like me, anyway, but I don’t care because talking about this stuff makes me happy and that’s what we’re all trying to find these days – stuff to talk about that gives us a little happiness). At some point we’ll talk strings, guys. And we can talk guitar collections, too, if you like.

[image error]

Rickenbacker 4003 in walnut. And the bucket list grows more complete.

But not today.

Today I give you the benefit of my nerdy expertise as an English professor and slightly known lit fiction author. This list is mostly “serious” work, but future lists will talk about music books and cozy mystery (think Dorothy Sayers, Margery, of course, Agatha, Caroline Graham, M. C. Beaton, etc.) so there’ll be plenty to consider for your own private Decameron.

So in 2018 I made up a reading list. I wanted to choose books that gave me a sense of what America was, or thought it was, or pretended to be. I had planned my return to blogging by talking about these books individually (or maybe in groups of 2 or 3).

To the list, then. I went looking for America (whatever that is) via literature. Here’s what I found:

What Unites Us – Dan Rather – blowing sunshine – or smoking it. You gotta love ol’ Dan for wanting America to be more than it is….

John Smith’s America – there are various editions of this – any is fine – mostly lies, anyway, but it’s good to meet one of the earliest myth makers….

Autobiography – Benjamin Franklin – full of aphorisms and fiction but quite enjoyable

The Last of the Mohicans – James Fenimore Cooper – slow and plodding but so full of unintentionally great thoughts about the idea of America

The Scarlet Letter – Nathaniel Hawthorne – like the poor, the Religious Right has always been with us…

Billy Budd and other Stories – Herman Melville – the real jewel is “Bartleby the Scrivener” – a great, great story about what it means to make one’s job one’s life…

The Rise of Silas Lapham – William Dean Howells – best known as the editor of The Atlantic and early supporter of both Mark Twain and Stephen Crane (far greater writers), this novel is about how Americans think about themselves, money, and themselves as how much money they have…it is fantastic….

My Antonia – Willa Cather – as fine an example of what happens when a country sees itself as a “melting pot” when it – well, isn’t…lovely, lovely, elegiac book….

The Mysterious Stranger and Other Stories – Mark Twain – No, not Huckleberry Finn – the story of America is in “The Man Who Corrupted Hadleyburg” and the title story of this collection…

Maggie A Girl of the Streets – Stephen Crane – Red Badge of Courage gets all the love but this is as insightful into how America eats its young as any book I know…

White Fang – Jack London – might give pause to those thinking that moving back to the rural environs is the answer…

Sister Carrie – Theodore Dreiser – Dreiser is an awful writer (well, better than Upton Sinclair, but that’s like saying solid shit is better than diarrhea) – some would argue for An American Tragedy, but this book illustrates how America treats women as well as any book by a man can do….

Barren Ground – Ellen Glasgow – as good a book about the South’s inability to mend itself as there is – better than Faulkner or O’Connor in that Glasgow doesn’t feel the need to drown ideas in gothic myth or inscrutable language….

Main Street and Babbitt – Sinclair Lewis – no one understands the narrowness, anti-intellectualism, and self-satisfaction of Americans better than Lewis. One should really read both books back to back – they are a summary of why in spite of every advantage we were bound to face the struggles we face.

Laughing Boy – Olive La Farge – a book that tries hard (perhaps misguidedly) to make American readers understand the Native American people we displaced and destroyed to build – whatever it is we have built. This book, by the way, beat Look Homeward, Angel, A Farewell to Arms, and The Sound and the Fury for the Pulitzer Prize for 1930.

Winesburg, Ohio – Sherwood Anderson – a quietly great book, it is about Americans as humans – quirky, loving, not quite as aware as they should be. I dearly love it.

Tobacco Road – a terrible, wonderful book about the South – as mean spirited as possible, and so full of truth if anyone Southern is honest that it hurts…

The Grapes of Wrath – John Steinbeck – if there is a Great American Novel, this is it.

House Made of Dawn – N. Scott Momaday – if you want to understand the Native American Mind, read this book. You probably won’t understand the Native American Mind, but you’ll know that’s on you, not on Momaday. And you’ll respect the Native American Mind – which is the important thing.

Trout Fishing in America – Richard Brautigan – because part of being an American should be reading a book that ends with the word “mayonnaise.”

The Crying of Lot 49 – Thomas Pynchon – my generation, which kinda sorta includes Pynchon, thought we’d change the world – or at least America. What Pynchon puts out there for us is the inverse – the world – or maybe, America – changing us.

As I said at the beginning, this is not an easy list (the term “light”is an example of what we call irony). But this is an important set of books because all have at one time or other been solid members of the “canon” of American lit.

If part of this seclusion we’re all in is thinking about who we are and who we want/don’t want to be – then trying a few of the books on this list might help you gain some insight.

I’ll be back soon to talk about some/all of these books in more detail. Meanwhile.

August 16, 2018

Aretha and Elvis: the burden of being authentic

“…we want to talk right down to earth in a language that everybody here can easily understand.” – Malcolm X.

At the end of his long running eponymous music program, the late Don Cornelius always ended his program with this reminder of three of life’s important elements:

[image error]

Aretha Franklin 1968 (courtesy Wikimedia)

No one epitomized that Don Cornelius reminder of those important elements than Aretha Franklin, who died today and whose passing takes from us one who was undoubtedly the greatest singer of her generation and whose talent influenced singers ranging from Janis Joplin to Adele.

Aretha, like the iconic music figure with whom she, sadly, shares a death date, Elvis Presley, now belongs to the ages. But it’s important to consider what Elvis and Aretha share beyond the date of their passing into history. Both figures, enormously talented singers, achieved iconic status for bringing to a larger world music and cultural considerations that had long been ignored because racism and sexism dominated the worlds they were born into in ways that made their music carry more powerful messages – and greater burdens – than either of them would ever have intentionally pursued. Both of them, after all, wanted to be what they were – musicians and artists. Both of them strove to be authentic. At reaching that lofty (and perhaps Utopian) goal of authenticity, ultimately Elvis failed and Aretha succeeded.

The struggles of both have made for many volumes on Presley and will make for many on Franklin. Elvis, the King of Rock ‘n Roll. Aretha, the Queen of Soul. “Uneasy lies the head that wears a crown” the guy who could be called the King of Literature reminds us. But on this sad day, it’s important to remember why those volumes have been or will be written.

Presley brought the power of both black Southern blues and gospel music to white audiences who had been “protected” from them by – oh, what’s the right terminology – yeah, right, racists. Nowhere is that better presented in his oeuvre than in this ditty from 1954 that set him on his path to world domination:

Unlike Elvis, Aretha didn’t find her voice right away. She struggled for a few years, misunderstood by a record company who saw her more Ella Fitzgerald/Sarah Vaughan than as the dynamo of feminism and racial equality that she became when turned loose by Jerry Wexler. Once she found her voice and message, though, she became both a civil rights and women’s rights spokesperson of the highest order, as this anthem attests:

After bringing rock ‘n roll to the masses with a series of brilliant songs (almost exclusively written by others, one must admit), Elvis, always a far more obedient fellow than his image suggested, retreated into making shitty movies and recording shittier pop songs written for those movies at the behest of arguably the worst manager in the history of the music business. There was another brief shining moment in 1968-69 when he made a “comeback,” but that degenerated into endless Vegas puffery and endless touring to bring that Vegas puffery to the masses. He died, an “old” young man at 42, worn out with being “the King.”

Aretha endured bad marriages, career ups and downs, and health problems. She reinvented herself, sometimes, brilliantly, sometimes, disastrously (have you listened to “Who’s Zoomin’ Who” lately?). Eventually, though it seems fairer to say inevitably, she became a legend, THE diva among divas, as evidenced here where she takes a song written by one of pop music’s greatest songwriters and shows how it should be sung with the songwriter standing three feet to her left:

What should we conclude?

Elvis lost Elvis and never found him again – and, in a way, that killed him as surely as the pharmacopoeia he ingested. One can infer that the bad jokes and the myths (Elvis is alive!) that his memory has endured for the last 40+ years are a reflection of the deep cultural question and have asked not “Where is Elvis?” but “Who is Elvis?” Perhaps those who love him in spite of his failing find themselves remembering more lines from Shakespeare:

And tell sad stories of the death of kings;

Aretha fought plenty of demons of her own – but she never lost Aretha. Another thing: she never lost her deep religious faith – like Elvis, Aretha was a remarkable singer of gospel as well as secular music. Unlike Elvis, Aretha’s relationship with that music reflected a deep spirituality that Elvis yearned and strove for but ultimately failed to realize. Elvis love gospel music as music; Aretha loved it as a statement of her trust in a higher power that succored and sustained her – and allowed her to hold on to an authenticity throughout her life and career that Elvis had and lost and found again and lost again.

It’s how she got over.

February 7, 2018

Why Jesus don’t want me for a sunbeam – the great rock ‘n’ roll ripoff…

“Jesus don’t want me for a sunbeam/Sunbeams are never made like me…” The Vaselines, Nirvana

The Who – maximum sunbeam unworthiness (image courtesy Amazon.com)

An incident at the memorial service for my friend and former band mate, Mike, about whom I wrote a recent reminiscence, has been rattling around in my head for several weeks now. During that time I’ve finished reading the next to last book on the 2017 reading list, Reverend Emmett Barnard’s Rock ‘n’ Roll Ripoff! It’s one of the first of the religious right’s attacks on rock music as the ruination of American youth as well as one of the early salvos in the culture wars that movement has been waging for over 30 years.

As an academic and scholar, my view of Barnard’s book, which he presents in the form of a scholarly monograph, is that it’s a terrible book. It’s poorly written, weakly sourced, and generally sloppy. Repeatedly, Reverend Barnard displays a profound lack of knowledge of his subject, and the work is rife with factual errors.

Barnard, for example, identifies Paul Revere and the Raiders in the following passage:

Then of course, in 1963, the Beatles entered the scene, and a new era was born. This opened the floodgates to many English groups: Herman’s Hermits; the Dave Clark Five; Paul Revere and the Raiders (emphasis mine); the Rolling Stones and many more.

Paul Revere and the Raiders were from that most English of cities, Boise, ID.

Rock ‘n’ Roll Ripoff! is loaded with this kind of factual error. Egregious enough, to be sure. But Reverend Barnard is less interested in scholarly accuracy than in warning his readers of the insidious evil of rock and roll music. To do that he is willing to present information in ways that move beyond (possibly excusable) factual error into the questionable territory of misleading the reader. Here he discusses music from 1970, a year in rock notable for the “Jesus freak movement,” a short lived fad in rock’s long and checkered history:

Interestingly enough, in 1969 and 1970, ten percent of the rock ‘n’ roll recorded songs had a religious theme, though not necessarily Christian…. In 1970, Cashbox magazine reported that Norman Greenbaum’s song “Spirit in the Sky” was the year’s top moneymaker. Other songs included: “Let It Be,” by the Beatles; “Bridge Over Troubled Water,” by Simon and Garfunkel; “Amazing Grace,” by Judy Collins; “New Morning,” by Bob Dylan; and “Stage Fright” [!] by the Band…even…George Harrison was singing “My Sweet Lord,” with the background singers singing “Hare Krishna.”

This in itself isn’t misleading (though “Stage Fright” has no business being in the list above). Where Barnard moves beyond simple error into deliberate misrepresentation is in this aside he tosses off:

“Hare Krishna” means Prince of Darkness, by the way.

Hare Krishna doesn’t mean “Prince of Darkness.” But you knew that. I could offer a dozen more examples from the book, but that seems pointless. Barnard engages in the sort of delusional behavior in Rock ‘n’ Roll Ripoff! that we’ve come to associate with the Evangelical Right: misapprehension and even misrepresentation of facts in order to fit them to a predetermined narrative based on a belief system that is seemingly incapable of either, it seems, flexibility or rationality. Rock ‘n’ Roll Ripoff! is, to use an old Southern Baptist phrase, “preaching to the choir.”

And that, as John Donne would say, “…makes me end where I begun.” I mentioned at the opening of this essay an incident at my friend Mike’s memorial service. Mike and I had been somewhat estranged over the last few years. Mike became a “born again” evangelical Christian about 20 years ago, a move that affected our friendship slightly but that we overcame by consciously avoiding the topic of religion and focusing on our mutual love of music. At the memorial service the preacher talked a good bit about how Mike had once lived a “wild and unrepentant” life, even having allowed himself to belong to a “locally famous” rock band, Backyard Tea. But then Mike found Jesus – or Jesus found Mike, I’m unsure exactly how the whole experience works – and his life became “worth living.”

As my friend and band mate Steve and I drove back to his house from the service, we laughed about achieving one of any serious Southern rocker’s bucket list goals – we’d gotten preached against from a pulpit. When we got back to his place I dialed up a tune on my iPod for him. Here it is for you:

January 14, 2018

A kind of requiem – with milk and cookies and a white guitar…

“The language of friendship is not words but meanings.” – Henry David Thoreau

[image error]

Mike about the time our band, Backyard Tea, formed in 1971

One of my oldest friends died a few weeks ago.

Mike and I first met when were were 7 years old. We bonded over a mutual love of baseball and our love of our grandmothers. Mike lived with his; I visited mine frequently. Many times when I visited my grandmother we’d get together for an impromptu game of whiffle ball, or a game of catch, or simply a walk around the neighborhood. We’d talk about the stuff 8-9-10 year old kids talked about in those halcyon days of the early sixties: the New York Yankees (Mike was a lifelong fan), Batman vs. Superman, astronauts, Mad magazine.

We were typical American boys of our time.

Then came February 1964. I got a Silvertone acoustic for Christmas 1964 that I still own. Mike got the cooler guitar, a Silvertone electric with an amp built into the case. I have no idea what Mike did with his guitar. That was many guitars and adventures ago.

The goal was, of course, to become Beatles.

We’d gone to different elementary schools, but Mike and I went through junior high and high school together, at times close and hanging out regularly, at times drifting apart as we pursued our musical dreams. I was part of one band after another, most locally well known and successful but frustrating to me because they played covers and I’d begun writing my own songs. Mike chose to hang with a hipper crowd and played with a loose group of guys who, while they also performed covers, performed covers of Delta and Chicago blues tunes at the hippie hangout in our small Southern town, the coffee house at the Episcopal church. One night during our senior year in high school, my band, the best known in town, went down to the coffee house to – well, to be recognized and whispered about while checking out the competition.

The other guys in my band snickered at the primitive equipment and raw sounding performances of both blues covers and original songs Mike and his band did and were ready to leave after about 20 minutes after having had their egos stroked by both the crowd oohing and aahing at us and the young priest asking us to “stop by and play a few songs sometime.” I, on the other hand, was blown away – these scruffy guys with their second and third rate gear and lousy sound system were doing what I wanted to be doing – playing their own songs with passion and covering much cooler songs than the sixties pop our band played. I talked a little with Mike between sets that night and a few more times later at school about what his band was doing musically. Mike urged me to come by and jam with them any time.

High school being high school (or so I rationalize to myself now), I never took Mike up on his offer. I’d like to say there was some other reason, but the truth is I enjoyed being in the most successful band in town too much to let myself follow my calling then. My own band’s work became more and more of a burden in spite of the money – I got tired of the matching white pants/blue shirts we “had” to wear. I got tired of playing covers that tried to sound as “exactly like the record” as possible. I got tired of being the band beloved of moms looking for entertainment for their daughters’ sweet sixteen parties. The summer after graduation I began behaving more and more eccentrically, breaking the dress code, even showing up a sheet or so to the wind for a junior high swim/dance party. I got sacked in August just before I entered college. It was one of the best musical breaks I ever got.

After being kicked out of the top band in town, I scuffled for a while. I thought about crawling back and asking to rejoin, but the band imploded only a couple of months after I got booted; they ended badly after playing for a local beauty pageant and letting themselves be talked into playing backup for a contestant doing an interpretive dance and became laughing stocks as a result. I wasn’t doing much better, taking courses at the local community college and working part-time in a local textile mill. One day I wandered into the snack bar at the student center and there was Mike, strumming an acoustic guitar. He talked me into getting together with him and a friend of his. He said he thought the friend and I might want to write songs together and maybe the three of us could form a band.

After a little dithering, I agreed to get together. We clicked immediately; my keen pop sensibilities blended with Mike’s friend, Steve’s, equally keen blues and underground rock sensibilities in a way that gave us a distinctive voice. We formed a band a few months later. We had some success in the first half of the seventies. We didn’t become Beatles, but we did some fine work. Mike was not simply important to that work, he was at the heart of it.

But wait, there’s something more. Steve and I have been playing and writing together ever since, over 40 years now. He’s my closest friend. That band, that songwriting partnership, that friendship were just a few of many gifts Mike gave me.

***********

What we humans do when we talk about the dead is tell each other stories. We do this, I think, because it is impossible to convey to another the essence of what it meant/means to care for that dead person. Whatever that thing is that made/makes us love another person romantically, fraternally, parentally, admiringly, is, as far as I am able to discern, impossible to convey explicitly. So we tell one another stories about the beloved hoping, if we are the storyteller, that we are conveying what made that person special to us. As listeners, our task is to infer, one of the trickiest acts in communication; to understand from context the who, what, when, where, and why of the teller’s love from a story that may or may not convey all or any of those necessary details. As Edward Lear sagely observed, “Such, such is life….”

Here are two of my stories about Mike. You have been warned.

Back in 1994 I was at a low ebb as a musician. A disastrous divorce and a punitive ex-wife had forced me to sell my Gibson EB3 bass and my amp. Steve, who was methodically trying to reunite the band (yet again), convinced me to go to a jam session at Mike’s house, a big rambling farm house out in what passes for the middle of nowhere in Piedmont North Carolina. I didn’t play at first; I simply sat around watching the guys, having a beer, trying to be inconspicuous, ashamed both of my rustiness as a musician and of my lack of gear. About an hour or so into the session, while everyone was out on the porch taking a break, Mike asked me about my situation and I explained why I wasn’t playing. He gave me a pat on the shoulder and went inside. When we came back in and the guys began picking up instruments again, Mike caught my eye and nodded his head toward what had been an empty corner of the room. He’d set up a small bass amp and an old seventies era Univox bass as a rig for me. I played the rest of the evening and I got way more praise for my playing from the guys than it deserved. I felt better than I had in a long time. As I was walking out to the car about 1 AM, Mike came trotting up with a small acoustic guitar that some idiot had painted white, evidently with house paint. “I couldn’t get the paint off without damaging it,” he said, “but I’ve put a new nut and bridge on it and it plays okay.” I demurred from accepting it at first, then offered to pay him for it. “I bought it for $2 at a flea market,” he scoffed, “and I had the nut and bridge from another project. Besides, it’s gonna need new strings. Take it. No real musician should be without an instrument.”

**********

During the summer of 1963, as I usually did, I spent a couple of weeks staying at my grandmother’s house. Mike and I hung out together a lot during that time. Our favorite thing to do was climb onto the roof of my grandmother’s somewhat dilapidated garage. Several tall trees overhung the garage and made that roof a lovely, shady spot for a couple of guys to hang out, read comic books, and talk a lot – talk the kind of rot that 11 year boys talk. To fortify ourselves we needed snacks. Sometimes we’d walk up to the store on the corner about a block away and buy sodas and candy bars or snack crackers. Most of the time, though, we had milk and cookies. My grandmother allowed me to have all the milk I

Aluminum tumblers are a good choice for garage roof milk drinking – no breakage (image courtesy Pinterest)

wanted without questions, so I would simply get two glasses of milk in those aluminum tumblers everyone’s grandmother had back then. Mike’s grandmother didn’t allow him unlimited cookies, of course, so he swiped them (he was careful not to take more than a couple of cookies for each of us) from her cookie jar. Somehow we managed to get the milk onto the roof every time without spilling it. I don’t think either of us said anything memorable while we sat on that roof, reading comics, sipping milk, nibbling cookies.

I’ve thought of these two events from my friendship with Mike repeatedly in these last weeks since his death. They have deep meaning for me.

Thoreau is right, I think. Friendship uses the language of meanings.

December 10, 2017

Republican new order looks a lot like medieval old order…

“…ternarity became the ideology of feudal society; the division into groups was “not on the basis of actions performed, roles played, offices assumed, or services mutually rendered, but rather on the basis of merit.” – Georges Duby

Medieval depiction of The Three Orders: left to right, the Clergy, the Nobility, the Laborer (image courtesy W. W. Norton)

As what the Republicans call the “tax cut” bill and 79% of the public calls the “tax cuts for the rich, nightmares for everyone else” bill moves toward a vote, I’ve been thinking a lot about the French medieval historian Georges Duby.

That’s how I roll, people.

Duby has been on my mind because a couple of years ago I wrote an essay on his masterful examination of the socio-economic structure of medieval Europe, The Three Orders. I’ve been turning over in my mind one passage in particular from that essay:

What is left for readers is to consider how Duby’s elucidation of that far off time provides insights into our own imaginings of this new millennium.

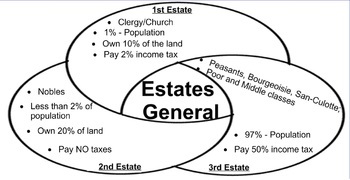

Duby’s term for the organization of medieval society, as mentioned above in the quote, is ternarity. The standard divisions are as follows: those who pray (the clergy, which included all offices of the church from humble parish priests to the Pope); those who fight (which included the nobility, especially those serving in the knighthood); and those who labor (this group included all of those considered commoners whether wealthy merchants, traders/craftsmen, or impoverished farmers). Here’s a pretty apt diagram with some statistical information about the percentages of society belonging to each group:

The medieval system of ternarity, still in place in 1789, that was finally ended by the French Revolution (image courtesy Teachers Pay Teachers)

We hear a lot these days about the 1% and the rest of us. For those of us worried about economic inequality (which, I suspect, is anyone reading this), here’s some discomfiting information: by the time of the French Revolution in 1789, under the ternarity system,”those who labor” paid a 50% tax rate while the church paid 2% and the nobility paid nothing.

In America, we do things differently, of course. Here the church pays no taxes even as some of its princes – both Roman Catholic and evangelical – live like real princes. Our “nobility,” the rich, pay tax rates that are, on paper, considerably higher than the church paid under the Ancien Regime. However, plutocrats need not fear – the elimination of major deductions for the majority of individual citizens coupled with the elimination of taxes applicable only to the rich will ensure that the tax burden shifts far more onto, shall we say, those who labor. (We should not ignore corporations who hold status as “citizens” and enjoy – and will enjoy in future – protections from taxes via deductions and credits that are unavailable to those who labor.)

The anger rising in America over its growing income inequality will only be exacerbated by this new tax plan – a main provision of which will likely continue to guarantee that income inequality continues for the foreseeable future. Whether that anger will accelerate or subside into acceptance (sullen or resigned) remains to be seen. Perhaps the rich will find comfort in historical fact: it took approximately 500 years under the oppressive system Duby examines in The Three Orders for the anger of the oppressed to explode into the bloody retribution of the French Revolution. Unfortunately, 21st century technologies will likely shorten – perhaps geometrically – the time span that our American “betters” lord it over the rest of us. What is now merely known as the Resistance may explode into revolution – sadly, likely violent – in short order.

A scholar like the late Professor Duby would certainly have found this turn in historical events fascinating. And the words of Georges Santayana might creep into his thoughts:

Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.

November 19, 2017

Dear Mr. Buffett: about your excess cash problem…

“Warren Buffett has advocated for higher taxes on the rich and a reasonable estate tax. But his company Berkshire Hathaway has used ‘hypothetical amounts’ to ‘pay’ its taxes while actually deferring $77 billion in real taxes.” – Paul Buchheit, Bill Moyers and Company

Warren Buffett with a little of what he has a lot of (image courtesy Wall Street Nation)

This an an open letter of sorts to the richest person in Omaha, Nebraska.

A recent Motley Fool article bemoaned a problem that can best be described as peculiar to one in Mr. Buffett’s life situation:

As of Sept. 30, Berkshire [Hathaway] (Mr. Buffett’s company) was sitting on more than $109 billion in cash, which represents nearly one-fourth of the company’s entire market cap, and the Oracle of Omaha is undoubtedly feeling the pressure to start putting it to work.

The author of the article, Matthew Frankel, reassures us that he realizes that Mr. Buffett’s problem deserves to be placed in its proper context:

To be clear, having a massive sum of cash is certainly a good problem to have. It’s certainly better than not having enough cash, or having too much debt.

If your response to the above was “Well, duh,” you might be in the 99%.

So here’s an open letter to Warren Buffett, “the Oracle of Omaha,” about ways in which he might use some, if not all, of that excess cash he has lying around.

Dear Mr. Buffett:

You wouldn’t know me because I’m only one of the nameless rabble that those who breathe the rarefied air of the super-rich don’t have much contact with. To help you with perspective on my plight, which is that of millions and millions and millions of people, think of me as someone like your secretary for whom you expressed great sympathy (I understand how it might be difficult for you to experience much in the way of empathy given your life situation vis a vis said secretary). I am a college professor, a job that admittedly raises eyebrows in what some with your financial status whose political views are, shall we say, more strident than yours, find questionable, and by some measures I would be classified as a privileged member of the middle class. I am not sure that I feel that way, but as we both know, uncertainty about money is a worrisome thing, carrying as it does the weight of loss of status, something Americans, despite our claimed equality, feel considerable anxiety about.

Anxiety creates opportunity, though, doesn’t it?

I am aware that you are one of our greatest philanthropists. So my suggestions to you as to what you might do with that vast amount of excess cash you have “lying around” (or whatever the “billions and billions” equivalent of finding a fiver in a coat pocket is) are based on both your generosity and some of the needs we could both easily identify given the economic inequality overwhelming our country.

So here are some ways in which you could use some (not all, of course! I know you have a rule about keeping $20 billion cash on hand) of that loose change ( I know this may come across as poking fun, but we kid those we like, Mr. Buffett, and though billionaires as a class have proven themselves pretty unlikable in the main, you have proven to be an admirable exception). Not all of these will appeal to you, perhaps, but surely you can find something – perhaps multiple somethings – that you find worthy of an investment.

Since Motley Fool estimates your cash excess at $109 billion and you prefer to keep 20 billion on hand in cash for your company, Berkshire Hathaway, that leaves only $89 billion available for investment (though if your stock purchase in Pilot/Flying J has gone through that amount will be only $80 billion, still a not inconsiderable sum in my humble estimation). In the vast world market in which you do business that may not seem an extraordinary sum, but let me assure you that for the majority of Americans it’s a mind boggling amount. And invested in the people of this country which has given you the opportunity to become the wealthy man you are, I think you would be able to get both tangible and intangible rewards (those latter rewards are talked about a great deal in my profession where tangible rewards are modest compared to other professional fields).

So, a few suggestions.

Well, the Trump budget slashes large amounts from agencies such as the EPA, and departments such as the Interior, Education, HHS and HUD. Investing about $20 billion in social nonprofits, and environmental groups that work to protect the environment and help citizens gain decent housing and educational opportunity would both offset these cuts and provide our country with a cleaner environment, preserve national treasures such as our National Parks, and eventually produce a healthier, better educated citizenry, a long term economic boost.

An infusion of Berkshire Hathaway capital (a small amount, say,$2-3 billion) into green energy initiatives would both offset Trump’s cuts to these initiatives and foster more rapid development of energy alternatives such as wind and solar power. Such an infusion would create jobs and be beneficial for the environment.

Finally, the arts in America are in crisis due to ever increasing budget cuts. Investing even a small (well, small by Berkshire Hathaway standards) amount of money to support state arts councils ($100 million to the arts council of each US state would total $5 billion) would pay cultural dividends and add to the attractiveness of every state for business investors – surely this would be a worthwhile use of money.

I could offer a number of other suggestions, Mr. Buffett, but I’ll be respectful of your time. My purpose in writing to you has been to suggest ways in which you might put some of your resources to use in ways that might bring both material gain and civic improvement to our country. Given our nation’s current condition, I am sure that risking the amounts of capital mentioned above may not meet your long established value investment philosophy. But as I’m sure you understand, I’ve been talking about more than mere investments – I’ve been talking about the future of our nation to someone whom I believe can help that future be better for all. Too, your example of investing in these areas might inspire those like you to rethink their investment strategies where our country is concerned.

To paraphrase a famous movie quote, help us Mr. Buffett – you might be one of our only hopes.

A fellow American,

Jim Booth

November 18, 2017

Awopbopaloobop Alopbamboom… rock music according to Nik Cohn

“Elvis is where pop begins and ends. He’s the great original and even now he’s the image that makes all others seem shoddy, the boss. For once, the fan club spiel is justified: Elvis is King.” – Nik Cohn

Awopbopaloobop Alopbamboom by Nik Cohn (image courtesy Goodreads)

One of the books from the 2017 reading list that I have most been looking forward to reading (actually re-reading) is Nik Cohn’s now classic 1970 book on rock music, Awopbopaloobop Alopbamboom. Cohn’s style, which is opinionated, brash, and merciless in his assessments of some of the musicians we think of as both musical and cultural legends (don’t be fooled by the encomium above – he takes plenty of shots at the post-Army movie star and the Vegas period lounge singer Elvis became).

He is, to me, one of the most authentic writers on the subject of rock music that I have ever read. I rate him with Peter Guralnick, Greil Marcus, and Lester Bangs (some would count Paul Morley in this elite company, but I find him pedantic and self-indulgent). Awopbopaloobop Alopbamboom is Cohn’s first book. Written when he was only 23, it is filled with the hubris and certainty of youth, and I suspect Cohn’s strong opinions, especially about his contemporaries, the rock stars who emerged in the 1960’s, have likely moderated – or hardened – over the years.

Still, nearly 50 years later Cohn’s opinions about both the founding figures of rock from the 1950’s – Chuck Berry, Little Richard, Fats Domino, Elvis Presley – and the great English stars – The Beatles, The Rolling Stones, The Kinks, and The Who – almost all of whom he knew, some closely (he was an intimate of Pete Townshend) resonate with a level of both the gravitas of a serious critic and the snarkiness of a kid in the mosh pit that impresses even as it sometimes maddens a knowledgeable reader. He’s as authentic as those he writes about.

A few examples serve to illustrate Cohn’s talent and his deep understanding of rock music. He is a fan of rock based in blues (despite his friendship with The Who’s Townshend, his favorite band, he tells us, is The Rolling Stones); he is dismissive of folk rock generally (he execrates pretty much everyone associated with it, even The Byrds and Buffalo Springfield, and expresses particular distaste for Crosby, Stills, and Nash); his critique of what he calls “California,” the West Coast groups from Los Angeles and San Francisco is alternately righteously angry (he is one of the first from the rock community to point out the mess that Haight Ashbury became as a cultural experiment) and his usual highly opinionated authoritativeness – Grateful Dead: simplistic noodlers; Jefferson Airplane: complicated noodlers; Doors: pretentious posers.

Where Cohn is most interesting and provocative is in his assessments of individual talents. As with his observation about Elvis above, he has his opinions on who’s good and who’s not, and he isn’t shy about sharing them. A few examples should serve to convey both how Cohn sees rock music and what he sees as talent. Here is is on Chuck Berry, a certified genius in Cohn’s not so humble opinion:

As a writer, he was something like poet laureate to the whole rock movement.

Bob Dylan, on the other hand, Cohn finds less than Nobel worthy:

How do I rate him? Quite simply, I don’t – he bores me stiff.

He rates both The Rolling Stones The Who very highly, his admiration predicated in the former case on the cacophony they created, in the latter on the band’s willingness to self-destruct as part of their act:

[The Rolling Stones] weren’t much on melody, their words were merely slogans…. All that counted was sound…. All din and mad atmosphere…. The words were lost and the song was lost. You were only left with chaos, beautiful anarchy. You drowned in noise….

Pete Townshend used to smash his guitar full in the amps, shattering it like kindling…. Roger Daltrey, who sang, used to swing his mike like a lariat and crash against the drums…Keith Moon used to play drums with twenty arms, mouth gaping and eyes bugged, flailing and thrashing like some dervish…John Entwistle used to play bass like Bill Wyman, bored as he could be, and he bound them down or else they’d have flown away….

The Beatles awed him in some ways, disappointed him in others. Cohn quoted one of the sixties great record producers, Bert Berns, in his assessment:

Those boys have genius. They may be the ruin of us all.

Cohn ends his book with a few words from that existential philosopher Richard Penniman, better known by his stage name, Little Richard:

The words of Little Richard still apply. They summed up what pop music was about in 1956. They sum it up now and always: AWOPBOPALOOBOP AWOPBAMBOOM

There’s not much way to argue with that kind if logic.

November 5, 2017

Coda: resisting McDonaldization…

“The system is run by the few with the few as the main beneficiaries. Most of the people in the world have no say in these systems and are either not helped or are adversely affected by them.” – George Ritzer

We’re all living in McDonald’s world (image courtesy LinkedIn)

The range of the standardized, bureaucratic system embodied in McDonald’s is now an immense web in which almost every American is enmeshed. The power of McDonaldization is now so great that for many people resisting the roles defined for us by McDonaldized business and institutional models feels, if not impossible, so difficult and time consuming (inefficient and unpredictable, not to mention difficult to calculate and hard to control) as to seem not worth the effort.

So, the vast majority of us continue to submit ourselves, if not willingly then unresistingly, to McDonaldized systems. From our daily activities of shopping and dining to our most important decisions such as obtaining health care and education, we are, all too often, faced with capitulating to McDonaldization to meet our life needs. We buy our morning coffee from the chain outlet, check and bag our own purchases from a big box store, go to the immediate care facility to get our sprained ankle treated. These behaviors are our first, sometimes our only, options. But most of use realize that such behaviors drain us of our humanity and individuality bit by bit. And we wish there were other possibilities.

There are ways of resisting McDonaldization. They require some effort, and not all will be doable at once. But resistance is vital if we hope to reclaim the humanity of our human institutions and interactions.

Here are a few possible ways of beginning to resist. While we may not be able to practice all of these right away, beginning with any is a step towards re-humanizing our interactions with the world:

Seek out restaurants that use real china and metal utensils; avoid those that use materials such as Styrofoam that adversely affect the environment.

When dialing a business, always choose the “voice mail” option that permits you to speak to a real person.

The next time a minor medical or dental emergency leads you to think of a “McDoctor” or a “McDentist,” resist the temptation and go instead to your neighborhood doctor or dentist, preferably one in solo practice.

Avoid Hair Cuttery, SuperCuts, and other hair-cutting chains; go instead to a local barber or hairdresser.

Frequent a local café or deli. For dinner, again at least once a week, stay home, unplug the microwave, avoid the freezer, and cook a meal from scratch.

Try to live in an atypical environment, preferably one you have built yourself or have had built for you. If you must live in an apartment or a tract house, humanize and individualize it.

Avoid classes with short-answer tests graded by computer. If a computer-graded exam is unavoidable, make extraneous makes and curl the edges of the exam so that the computer cannot deal with it.

Seek out small classes; get to know your professors. (list items courtesy plosin.com)

The McDonaldization of our economy and institutions was, as this series has tried to explain, an evolutionary process over many decades. Our recovery from its effects can only commence once we consciously begin to act in ways that resist its reach into our lives. Freeing ourselves from the convenience and control of McDonaldization might take time, but the pleasure of living lives less calculated, efficient and predictable will surely be ample compensation.

October 28, 2017

The McDonaldization of pretty much everything…part 5

“The bureaucracy is a dehumanizing place in which to work and by which to be serviced. The main reason we think of McDonaldization as irrational, and ultimately unreasonable, is that it tends to become a dehumanizing system that may become anti-human or even destructive to human beings.” – George Ritzer

Wall Street bankers discuss the housing market crash rationally (image courtesy Idle Log)

In part 4 of this series I discussed how the tentacles of McDonaldization have spread far beyond the fast food industry and attached themselves to almost every institution of American culture. This implementation of the hyper-rational methods developed by Ray Kroc for the McDonald’s food chain, however, when implemented, tend to foster irrational behavior and results.

As parts 1 and 2 of this series explained, McDonaldization is evolved from bureaucracy, a form of standardization that emphasizes chain of command, efficiency through strict limitation of individual duties and responsibilities, and above all, strict control over all operations. Kroc’s adaptation of this methodology for his hamburger stands distilled the rigidity of bureaucracy into four essential elements George Ritzer calls McDonaldization: efficiency, calculability, predictability, control. The application of these elements, as explained in part 3 of the series, was wildly successful – financially – and made McDonald’s the envy of first their direct competitors and then of the business world. Businesses of all sorts began to apply the McDonald’s methodology to their companies – with varying degrees of success.

Undaunted by the uneven success of the widespread application of McDonaldization across various lines of business endeavor, institutions whose primary focus was not the production of product in the pursuit of profit fell under the sway of business types (who entered those institutions, institutions such as healthcare and education, as “administrators” in order to help those fields become more efficient and controlled – by calculating costs such as the costs of medical procedures or college tuition by making them more calculable and ultimately, predictable) but who instead have overseen runaway rises in costs for both these institutions.

As I have noted numerous times before, it is important in considering the irrationality that is an unintended consequence of the hyper rationality that we remember how the elements of McDonaldization have to be applied for the system to produce “success” (which ia always measured in financial terms):

Efficiency – The optimum method of completing a task. The rational determination of the best mode of production. Individuality is not allowed.

Calculability – Assessment of outcomes based on quantifiable rather than subjective criteria. In other words, quantity over quality. They sell the Big Mac, not the Good Mac.

Predictability – The production process is organized to guarantee uniformity of product and standardized outcomes. All shopping malls begin to look the same and all highway exits have the same assortment of businesses.

Control – The substitution of more predictable non-human labor for human labor, either through automation or the deskilling of the work force.

Two factors affect the success of any endeavor that attempts to apply the methodology of McDonaldization. First, there must be a product – McDonaldization is a system of product production. Second, it is important to understand that inherent in any hyper-rational methodology are the seeds of irrationality – and that the law of unintended consequences will will undoubtedly release that irrationality.

* * * * * * * * * *

In applying the principles of McDonaldization to the institutions of education and medicine (which we think of by the term healthcare), the administrative class, which in both cases in the US arose during the 1980’s, boom years for the business classes, found itself faced with a dilemma – neither the practice of medicine nor the profession of education are products per se. This, as we now know, has not deterred those who have made it their mission to make healthcare and education into products. Much of this “productification” of these fields has come from irrational attempts to treat the practice of medicine and the profession of education as if they are products.

Let’s look at medicine. A health management organization (known commonly by the acronym, HMO) has broken down the practice of medicine into discrete divisions of labor – when a person gets sick and goes to the hospital, there is, for example, a clerical staff who handles admission paper work, a staff of medical personnel whose tasks are to operate machines (non-human technology such as X Ray, MRI, CT, etc.) which conduct medical tests, and a nursing staff whose job is to check on patient condition (which is machine monitored, more non-human technology) and administer medicine on a predetermined schedule. There are doctors, too, of course, but these highly educated and skilled professionals are now primarily tasked with performing procedures or supervising the bureaucracy described above as they attempt to practice their profession within this McDonaldized system.

Monitoring ALL of these employees are HMO administrators, both onsite at the hospital and in corporate cubicles somewhere overseen by supervisors, who answer to executives whose interest is in making a profit from the medicines, tests, and procedures done for each customer patient. Perhaps this explains why, after a hospital stay, a patient

Education, as anyone not living in a cave knows, has always served two purposes in American life, transmission of knowledge and socialization. Under the current McDonaldized system, largely controlled education is is now controlled by testing and assessment based on (unfunded) mandates which demand that education be treated like a product. More accurately, students are to be treated as customers and education is the product with proof that the product has been delivered Faculty at the el-hi level have been largely reduced to coordinators of tests and test preparation presenters. Student test scores determine school funding because the belief is that education is calculable in the aggregate as well as in the individual case. (The efficacy and accuracy of grades as a measure of individual learning is a discussion for another time.) Students’ social development is unimportant; what matters in this system is product performance. The irrational element in this should be obvious. The focus in this system is on the test, not on the student. The test is efficient, calculable, predictable, and controllable.

If one thinks that higher education fares better, think again. Since students pay for the privilege of attending college, college the college administrative class, naturally, thinks of students as customers and the college degree as a product. Since education is considered a product, two lines of thought dominate: education should be efficient (students should learn only what will make them more successful in the job market and their careers) and students who will live on campus must offered every convenience (and indeed, luxury) in their accommodations. Subsequently, curricula have been redesigned to de-emphasize liberal education and emphasize “practical” majors such as computer science (especially areas such as cyber security and software development), criminal justice, and the various areas in the business school such as marketing, human resources, and management. To make schools more attractive to students, colleges have built housing that includes private rooms and baths, and numerous amenities including snack bars and exercise facilities.

To help defray the costs of this kind of investment, budgets for less important elements such as faculty have been slashed. The majority of students in US colleges today are taught by underpaid adjunct faculty who are often portrayed as “teacher-practitioners” with “real world” experience (a marketing ploy designed to support the claim that “University X provides degrees that earn jobs”). This has been portrayed as economically efficient, calculable, and predictable use of higher education resources. But while the quality of student accommodations has been enhanced to luxurious, the quality of students’ actual education, built upon transient, underpaid adjuncts instead of on a stable, tenured full-time teaching faculty, has declined in ways that will only become obvious in the coming years. The wrapper has been made shinier, but the burger’s contents have been compromised.

The redesign of healthcare into bureaucratic processes is one form of irrationality deriving from the field’s McDonaldization. The recasting of higher education as job training in a luxurious setting is another. These kinds of irrationality will have wide ranging, far reaching, long lived effects on our culture. The likelihood that these practices will be reversed in the near future is nearly nil.

But one small step toward reversing the effects of McDonaldization and its attendant irrationality is recognizing how it is working in our culture and trying to find ways of neutralizing its effects.