M.R. Dowsing's Blog

March 8, 2026

Asa no hamon / 朝の波紋 (‘Morning Ripples’, 1952)

Obscure Japanese Film #251

Hideko Takamine

Hideko Takamine

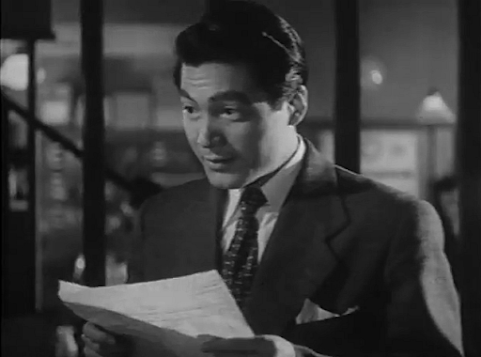

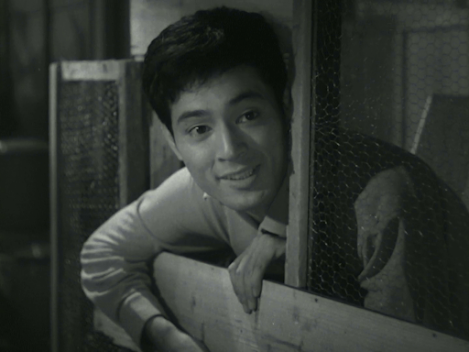

Atsuko (Hideko Takamine) is ayoung woman living at home with her mother (Hisako Takihana) andnephew Kenichi (Katsumasa Okamoto), whose father was killed in thewar and whose mother (Kuniko Miyake) works at a hotel in Hakone.Kenichi has become very attached to a stray dog he adopted but whichhis mother disapproves of due to its habit of stealing theneighbours’ shoes (the implication is that Kenichi feels ratherlike a stray dog himself). Atsuko works at a small trading company,where one of her ambitious male colleagues, Kaji (Eiji Okada), hasdeveloped a crush on her. One day she meets the less serious Inoda(Ryo Ikebe), who has befriended Kenichi and works for a largertrading company, and the two hit it off. However, Kaji’s jealousy,together with a dispute between the two rival companies over aclient, threatens to destroy their burgeoning romance…

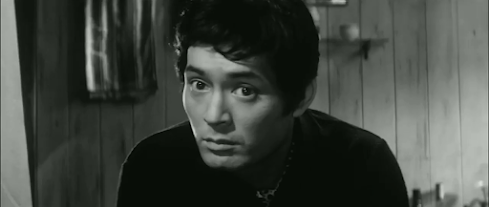

Ryo Ikebe

Ryo Ikebe Kuniko Miyake

Kuniko MiyakeDistributedby Shintoho, this was the second production by director HeinosukeGosho’s independent production company Studio 8. It was based on anovel of the same name by Jun Takami (1907-65), whose work alsoprovided the basis for the previously-reviewed Love in theMountains (1959), a similarly modest and sentimental love storyabout ordinary people.

Althoughthis was far from star Hideo Takamine’s most interesting role, sheand Ryo Ikebe make for an appealing pair as they search the post-warrubble of Asakusa in search of Kenichi after he runs away –Asakusa, most of which had been destroyed by bombs, was evidently notyet fully rebuilt in 1952, the final year of American occupation.Incidentally, Takamine speaks English in several scenes here as thecompany Atsuko works for does most of its business with foreigners.Her modern, independent personality and ability to do her job well isnot always appreciated by her male colleagues, including Kaji. whoare at times quite condescending towards her.

Eiji Okada

Eiji OkadaThefilm is full of quietly effective little moments, such as when Inodatakes a break on the stairwell with his colleague, looks down to seethe cleaning woman on the floor below, then turns to look up at thesun shining through the window; although the influence of Westernculture is apparent everywhere in the lives of these characters, suchmundane details feel a long way from Hollywood.

Amongthe supporting cast, the best-known face is that of future AkiraKurosawa favourite Kyoko Kagawa, who appears here briefly as a nun.

Thecopy I watched was a low-res VHS transfer viewable on YouTube here,but I assume the Japanese DVD is better quality. English subtitlescourtesy of Coralsundy can be found here.

If you enjoy this blog, feel free to Buy Me a Coffee!

March 4, 2026

The Last Judgment / 最後の審判 / Saigo no shinpan (1965)

Obscure Japanese Film #250

Tatsuya Nakadai

Tatsuya Nakadai Masao Mishima

Masao Mishima

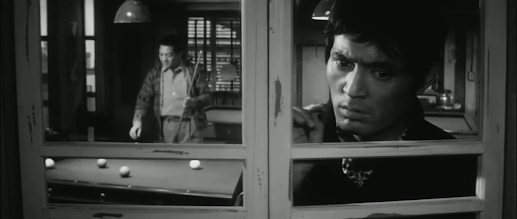

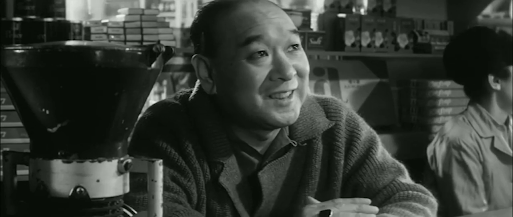

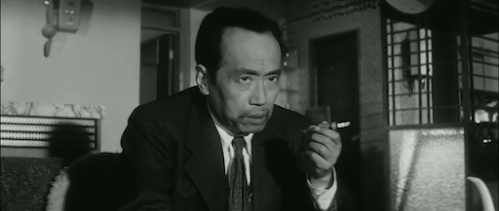

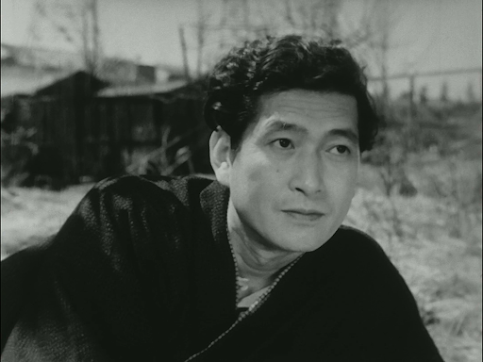

Jiro(Tatsuya Nakadai), the manager of a pool hall owned by Asai (MasaoMishima), has been having an affair with Masako (Chikage Awashima)since her wealthy engineer husband went to oversee a constructionproject in Vietnam two years earlier. The husband in question,Riichiro (Fujio Suga), also happens to be Jiro’s cousin. When hereturns from abroad, it becomes very difficult for the lovers tocontinue meeting, especially as Riichiro is not only a jealous andsuspicious type, but has a short fuse to boot.

Fujio Suga

Fujio Suga Jitsuko Yoshimura

Jitsuko YoshimuraMeanwhile,Asai wants to sell the pool hall and Jiro wants to buy it but lacksthe funds. He also has little time to find them as the local yakuzawant to buy the place, but then he thinks of a clever solution to hisproblems. This will involve both seducing a waitress, Miyoko(Onibaba’s Jitsuko Yoshimura), and getting Riichiro to usehis explosive temper against himself. But will Jiro be able to stayone step ahead of dogged police detective Kikuchi? (This latter isplayed by Junzaburo Ban, who played a similar character in the sameyear’s A Fugitive from the Past.)

Junzaburo Ban

Junzaburo BanThisToho production was based on the 1949 novel Heaven Ran Last byWilliam P. McGivern (1918-82), who also wrote the novels on whichFritz Lang’s The Big Heat (1953) and Robert Wise’s OddsAgainst Tomorrow (1959) were based. Heaven Ran Last,though, was neverfilmed by Hollywood and, like Kurosawa basing High and Low(1963) on Ed McBain’s novel King’s Ransom, it’s anindication of how much American pulp was being translated intoJapanese in the post-war years that it came to the attention ofdirector Hiromichi Horikawa. In this case, apart from transferringthe story from America to Japan, screenwriters Zenzo Matsuyama andIchiro Ikeda have stuck pretty closely to the book – too closely,perhaps, according to some Japanese reviewers who have commented thatthe characters don’t behave like Japanese people. In any case, Ifound it to be one of the better plots I’ve seen in this type offilm as the twists don’t become too far-fetched, as is so often thecase.

Chikage Awashima

Chikage AwashimaSeveralof the same talents from Horikawa’s excellent 1963 noir Shiro tokuro (‘White and Black’, aka Pressure of Guilt)returned for this one, including Japan’s top film composer ToruTakemitsu as well as cast members Chikage Awashima, Masao Mishima,Eijiro Tono and, of course, star Tatsuya Nakadai. The LastJudgment makes an excellent vehicle for Nakadai, who looks verycool driving around in an MG Roadster in his shades and fur-linedjacket and is obviously having a field day being very bad indeed.However, Jiro is saved from becoming a one-dimensional villain notonly by Nakadai’s charismatic performance but the fact that his love forMasako, at least, does seem to be genuine.

Oneof the great things about Takemitsu as a composer was that he knewwhen to shut up, an all-too-rare talent which is well in evidencehere, while Horikawa makes excellent use of industrial noises toheighten the tension in a number of scenes. Another plus is the dark,shadowy cinematography of Tokuzo Kuroda. All in all, The LastJudgment is a very satisfying noir that has been kept in the darkfor far too long.

Thanksto A.K.

Ifyou enjoy this blog, feel free to Buy Me a Coffee!

February 27, 2026

Kanashiki kuchibue / 悲しき口笛 (‘Sad Whistling’, 1949)

Obscure Japanese Film #249

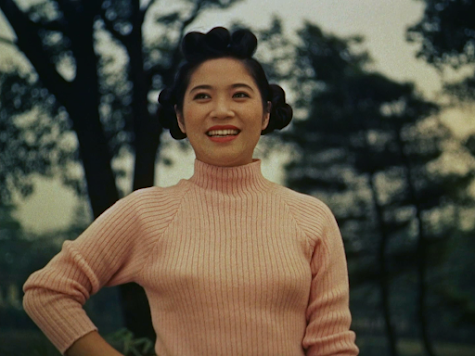

Hibari Misora

Hibari Misora

Mitsuko (Hibari Misora) is ahomeless child who hangs around with the day labourers at the docksin the Sakuragicho district of Yokohama. They look after her and shekeeps them entertained by singing, for which she has a remarkabletalent. Mitsuko dresses as a boy, but it’s never explained whetherthis is simply because it was easier for her to get hold of boy’sclothes or for some other reason. However, she is soon adopted anddressed in girl’s clothes by a waitress named Kyoko (KeikoTsushima) and her father, Osamu (Ichiro Sugai), a classical violinistreduced to busking to make a living.

Keiko Tsushima

Keiko Tsushima Ichiro Sugai

Ichiro SugaiMeanwhile,Mitsuko’s older brother, Kenzo (Yasumi Hara), a musician, hasfinally made it back to Yokohama after being posted overseas duringthe war and is searching for his sister but has also become involvedin a smuggling racket. One night he runs into Osamu, who is extremelydrunk and singing a song which Kenzo wrote but never published. Kenzoknows that Osamu could only have heard the song from Mitsuko, butOsamu is too intoxicated to provide any useful information. WhenOsamu subsequently goes blind as a result of drinking bootleg liquorcontaining methanol, Kyoko’s efforts to raise money to pay hismedical bills result in her being forced into helping the same gangof smugglers that Kenzo is involved with...

Yasumi Hara

Yasumi HaraAlthoughit lacks big Hollywood-style production numbers, this Shochikuproduction has enough songs that it certainly qualifies as a musical.It was based on a story by the prolific Toshihiko Takeda (1891-1961),whose work also provided the basis for Tomu Uchida’s Policeman(1933) and Hiroshi Shimizu’s Why Did These Women Become LikeThis? (1956). It was the third film to be directed by MiyojiIeki, who would become known for films dealing with childhood,although this particular film has the feel of an assignment, and itsmain raison d’être was probably to function as a vehicle forsinging prodigy Hibari Misora. She was 12 at the time but looksyounger; it was her fifth film appearance but her first starringrole. Here, she comes across as a sort of Japanese Shirley Temple,which might not be entirely by chance – its worth remembering thatthe film was produced during the occupation when filmmakers neededthe approval of the American authorities. As well as Hibari’ssinging, Keiko Tsushima – a trained dancer as well as actor –also gets to strut her stuff.

Kanashikikuchibue is a contrived and sentimental tale but it’s quitewell-made and lent a little interest due to its portrayal of achaotic post-war world in which people are forced to do whatever theycan to survive.

Hibari Misora

Hibari MisoraSungby Hibari, the title song was released about a month before the movieand became a huge hit.

DVDat Amazon Japan (no English subtitles)

Ifyou enjoy this blog, feel free to Buy Me a Coffee!

February 22, 2026

Shirobamba / しろばんば (1962)

Obscure Japanese Film #248

Toru Shimamura

Toru ShimamuraThisNikkatsu production was based on the autobiographical novel of thesame name by one of Japan’s major writers, Yasushi Inoue (1907-91).The book was translated into English by Jean Oda Moy in 1991, butInoue’s sequel, Zoku Shirobamba, has been neither filmed nortranslated, and the fact that Nikkatsu never made the sequel suggeststhat this film was not especially profitable. The story concernsInoue’s own childhood in Izu in the early Taisho period (1912-26)when Inoue was around seven years old, and the title refers to thewhite aphids that the children would try to catch in the autumn.

Izumi Ashikawa

Izumi AshikawaInoue’salter ego is Kosaku (played here by Toru [later Miki] Shimamura),whose rural upbringing is unusual in that his parents, though living,are absent, and he’s brought up by his lategreat-great uncle’smistress, known as Granny Onui (Tanie Kitabayashi). He’s all she’sgot, so she spoils him, and he’s very attached to her as a result.The only other person he really likes is Sakiko(Izumi Ashikawa),whom he calls his eldersister although she’s actually his aunt. Unfortunately, shelooks down on Onui and there’s no love lost between the two women.Sakiko lives in the ‘Upper House’ nearby with Kosaku’s otherrelations, but he feels uncomfortable there and avoids them. Kosakugets the highest grades in his year at school and his family has ahigher social status than his classmates’, so he feels different tothe other boys and great things are expected of him.

Jacket of the novel in English translation

Jacket of the novel in English translationReadingthe novel in translation a while ago I was reminded of the films ofKeisuke Kinoshita and wondered if the book had ever been filmed;looking it up, I found that not only had it been, but that thescreenwriter was none other than Keisuke Kinoshita himself. However,it’s directed not by him, but by Eisuke Takizawa, who seems to havebeen Nikkatsu’s director of choice for their more prestigiousliterary adaptations during this period (not a genre they’re widelyremembered for).

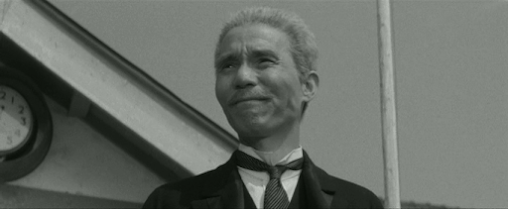

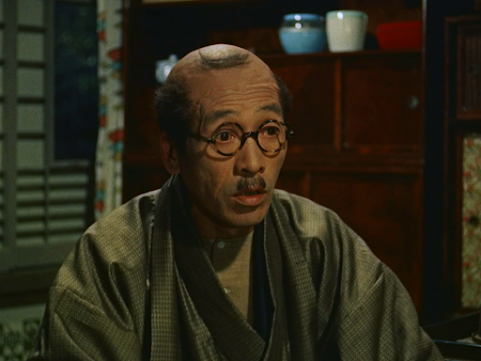

Jukichi Uno

Jukichi UnoIhad high hopes for this film but, although its superficiallyfaithful, one of the strengths of the book is its lack ofsentimentality, and it was disappointing to see the storysentimentalised as it has been here, especially in regard to composerTakanobu Saito’s clichéd use of mandolin and harp. There’s alsobeen an overall softening of tone – to give a couple of examples,in the book, the schoolteachers think nothing of dishing out corporalpunishment, and Sakiko is an arrogant snob, while here the teachers(one of whom is played by a twinkly-eyed Jukichi Uno in old man make-up) are far moregenial and Sakiko – perhaps partly due to the casting of popularstar Ishikawa – is a much gentler character.

Tanie Kitabayashi

Tanie KitabayashiTalkingof casting, I felt that a lack of imagination was evident in hiring51-year-old character actress Tanie Kitabayashi to do her old grannyact yet again when Sachiko Murase would have been a far better fitfor the complex character described by Inoue. Well-made though it is,ultimately I couldn’t help feeling that the film would have hadmore depth if it had been cast and scored differently and directed byKinoshita or Miyoji Ieki instead of Takizawa.

A note on the title:

Thetitle can be written as Shirobamba or Shirobanba inEnglish; the character んisusually written as ‘n’ in translation, but when pronounced beforea ‘b’, it’s natural to close the mouth more fully, so it comesout sounding more like an ‘m’. This is also the reason why bothTetsuro Tanba and Tetsuro Tamba can be considered correct.

Thanksto A.K.

DVDat Amazon Japan (no English subtitles)

Ifyou enjoy this blog, feel free to Buy Me a Coffee

February 18, 2026

The Beast Must Die: Mechanic of Revenge / 野獣死すべし 復讐のメカニック / Yaju shisubeshi: fukushu no mekanikku (1974)

Obscure Japanese Film #247

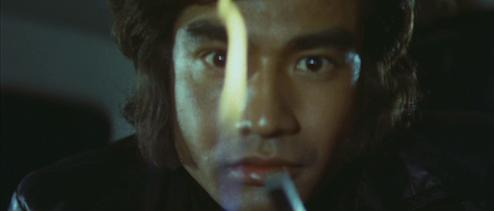

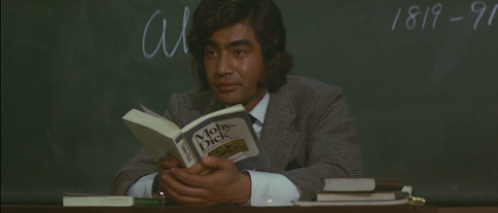

Hiroshi Fujioka

Hiroshi Fujioka

Atthe end of The Beast Must Die (1959), Kunihiko Date (TatsuyaNakadai), a highly intelligent but amoral student leading a doublelife as a thief and murderer, escapes the clutches of the police andjets off to America. In this sequel (loosely based on author HaruhikoOyabu’s 1960 sequel to his original book) he’s back from theStates and is now a Moby Dick-obsessed literature professor,but is still killing and stealing in his spare time. Although it’sunclear whether exactly 15 years have passed in story terms, it doeslook like 1974, and he’s now played by the 28-year-old HiroshiFujioka (Nakadai – who had been playing a little younger than hisreal age in the first film – was 41 by this point and perhapsdeemed too old. It should also be noted that he does not appear inthis film despite a credit on IMDb).

Date,who was already pretty nasty, has become even nastier (burning aman’s face, casually killing a woman who’s helped him, etc) buthas also been given a personal motive for his crimes. This time roundhe’s targeting the businessmen who drove his father to suicide andtook over his company. In my view, despite the fact that this elementseems to have been present in the book, this was a mistake – Dateis someone who simply does not care about other people, so it makesno sense that he would care about his father so much that he would goto all the trouble he does here to get revenge (in the superior firstfilm, Date does what he does because he views himself as a sort ofNietzschean superman above normal standards of morality).

Mako Midori

Mako MidoriHiroshiFujioka, previously a supporting actor in movies but a star in TV,fails to make much of the character and, while the supporting castare decent enough, they only have so much to work with. Mako Midori –something of a cult actress in Japan – is among them, but herscreen time is limited and she has been better served in other films,such as Yasuzo Masumura’s The Great Villains (1968). AkemiMari, who plays the other main female role, had been married to thisfilm’s director, Eizo Sugawa, since 1969. She’s fine here, buther film career never really took off, although she had some successon TV.

Akemi Mari

Akemi MariThefilm is also rather cheap and drab-looking – I suspect that Tohohad limited faith in it and only allowed Sugawa (who had also madethe first film) a pretty low budget. Incidentally, Sugawa made otherunrelated films with the word ‘beast’ in the title, including hisprevious film, Beast Hunt (1973, aka The Black BattlefrontKidnappers) and the excellent Beast Alley (1965).

Onthe plus side, the soundtrack features a cool combination ofclassical and jazz courtesy of composer Kunihiko Murai, who wasbetter known as a producer of pop music, though he also composed thesoundtrack for Tampopo (1985). Running a taut 86 minutes, thefilm also has an appealing leanness about it, and its misanthropictone is certainly of a piece with its director’s other best-knownworks so, while it’s certainly not as good as the first film, it’snot a total wash-out. (Incidentally, one of the screenwriters, YoshioShirasaka, had also worked frequently with that other greatmisanthropic director of the era, Yasuzo Masumura).

StarringYusaku Matsuda, Toru Murakawa’s 1980 remake of the 1959 original ismore impressive (if more self-indulgent) than this sequel andrecently received the deluxe Blu-ray treatment courtesy of RadianceFilms, while a further remake and sequel (neither of which I’veseen) appeared in 1997 starring Kazuya Kimura as Date.

It’sa bit low-res, but you can watch the film on YouTube with Englishsubtitles here.

Hearpart of Kunihiko Murai's original soundtrack on YouTube here.

Ifyou enjoy this blog, feel free to Buy Me a Coffee!

February 13, 2026

Sazae-san no seishun / サザエさんの青春 (‘Sazae-san’s Youth’, 1957)

Obscure Japanese Film #246

Chiemi Eri

Chiemi EriThisthird film in the Toho series kicked off by the previously-reviewedSazae-san was the first to be shot in colour, but otherwisedirector Nobuo Aoyagi repeats much the same recipe, even down toChiemi Eri dancing along the street singing ‘Bippidi-Boppidi-Boo’,as she had also done in the first film, although there are fewersongs this time around.

Here Sazae-san becomes engaged to herlong-term sweetheart, Fuguta (Hiroshi Koizumi), and tries to prepareherself for married life by taking on the household chores, helpingto look after her cousin’s new baby and getting a job in adepartment store to contribute to the household income. Of course,she makes a mess of all three, and disaster is only narrowly avertedwhen a female customer at the store takes a liking to Sazae andinvites her round for tea – it turns out that she’s the wife ofSazae’s father’s boss and sees Sazae as a possible future wifefor her son…

Releasedjust in time for New Year, this would have been intended as a film thatthe whole family could enjoy together, and it retains anold-fashioned innocence and charm, while the new colour photographysuits the material well, making it look appropriately more cartoonishthan it did in black and white.

Afterskipping the second film, Tatsuya Nakadai reappears here asSazae-san’s cousin, but has only one brief scene around 35 minutesin, in which he’s at a hospital waiting to see his newborn childfor the first time (typically, Sazae-san manages to mix it up withsomeone else’s baby to comic effect). Incidentally, Nakadai is notthe only Kurosawa favourite to pop up in these films – also presentis Kamatari Fujiwara, who appeared in no fewer than 12 Kurosawapictures, and even made it to Hollywood on one occasion, appearing inArthur Penn’s underrated Mickey One (1965).

Alsodeserving a mention is Tomoko Matsushima, who plays Sazae-san’sbig-eyed younger sister and is pretty funny in these films. Everyoneknows about Johnny Cash’s famous prison gig, but Matsushimaperformed at Sugamo Prison in 1950 at the age of 5 and apparentlyreduced around 1,000 war criminals to tears with her rendition of aJapanese song entitled ‘The Cute Fishmonger’. Later in life, shebecame a TV presenter and was attacked twice by big cats – once bya lion, another time by a leopard, luckily surviving both incidentswithout major harm. It has been speculated that her large eyes mayhave been a reason for the attacks as it’s inadvisable to look adangerous predator in the eye and presumably, therefore, even less ofa good idea if you have big eyes...

Watchedwithout subtitles.

DVD at Amazon Japan (no English subtitles).

Ifyou enjoy this blog, feel free to Buy Me a Coffee!

February 8, 2026

Sazae-san / サザエさん (1956)

Obscure Japanese Film #245

Chiemi Eri

Chiemi Eri Kamatari Fujiwara and Nijiko Kiyokawa

Kamatari Fujiwara and Nijiko Kiyokawa

Sazae(Chiemi Eri) is a young woman still living at home with her father(Kamatari Fujiwara), mother (Nijiko Kiyokawa) and two youngersiblings. She applies for a job at a women’s magazine but, afterbeing directed to the wrong door by the handsome young Fuguta(Hiroshi Koizumi), she accidentally ends up working for a literarypublisher instead. Her first task is to deliver the proof of a bookto an author, but he turns out to be the same man she had had anembarrassing misunderstanding with in a department store and she isfired. Fuguta suggests she try to get a job at a detective agencyinstead – unexpectedly, she succeeds, but her first assignmenthappens to be to spy on her cousin, Norisuke (Tatsuya Nakadai), ashis fiancee’s mother wants him investigated before agreeing to themarriage. She disguises herself as an old woman and begins to followhim around…

Chiemi Eri

Chiemi EriThisToho production was their first in a series of ten musical comediesstarring singing sensation Chiemi Eri as Sazae-san, a daydreamingtomboy with a strange hairdo. It was based on a comic strip byMachiko Hasegawa (1920-92), Japan’s first professional female mangaauthor, which first appeared in 1946 and ran in various newspapersuntil 1974. There have been various other adaptations, most notablyan anime TV series which has been running since 1969, makingSazae-san a true Japanese institution, albeit one that’s remainedlittle-known in the West.

Oneof the ironies of Japanese cinema is that, the more westernised thecharacters, the less likely a film has been to receive distributionabroad. The overseas market has tended to favour tales of samurai,geisha and yakuza, and (as far as I’m aware), Sazae-san hasnever been distributed in Europe or the U.S. At the end of the film,we see the family celebrating Christmas – which, of course, is nota Japanese festival, and the film is full of instances of Japanesepeople attempting to emulate westerners. The most extreme example ofthis is seen in the department store, where none of the mannequinslook remotely Japanese.

Thefilm was released in December of 1956 as the main feature in atriple-bill which also included two Tenten Musume pictures ofunder an hour each – very similar fare directed, like Sazae-san,by Nobuo Aoyagi, who had earlier made the excellent World of Loveand the previously-reviewed Hyoroku’s Dream Tale (both1943), but by this stage in his career seemed happy to be directinganything. In this case, there’s little to say about his directionexcept that it’s competent. Still, there’s some fun to be hadfrom Sazae-san’s antics, and Chiemi Eri proves herself an adeptcomedienne as well as singer. Incidentally, in her daydreams, Sazaehas a sensible haircut, glamorous attire and sings American-stylejazz songs.

Tatsuya Nakadai

Tatsuya NakadaiIt’salso amusing to see a young Tatsuya Nakadai as Sazae’s slightlyslow-witted cousin in the days when he still had to take whateverroles he could get. It’s difficult to think of a less typicalNakadai role than this one, and it has to be said that he doesn’tlook entirely comfortable singing along to Jingle Bells at thefilm’s climax. He managed to avoid the second film, but was ropedback in for the third in the series before escaping for good.

Watched without subtitles.

DVD at Amazon Japan (no English subtitles)

Ifyou enjoy this blog, feel free to Buy Me a Coffee!

February 5, 2026

Mogura Yokocho / もぐら横丁 (‘Mole Alley’, 1953)

Obscure Japanese Film #244

Shuji Sano

Shuji SanoThis Shintoho production wasbased on episodes from a number of autobiographical novels by KazuoOzaki (1899-1983), one of which gives this film its title. Ozaki isrenamed Kazuo Ogata here and played by Shuji Sano. In the originals,Ozaki was writing about his life as a struggling author in the 1930sbefore winning the coveted Akutagawa Prize in 1937. Perhaps forbudgetary reasons, director Hiroshi Shimizu chose not to recreate theperiod and, in one scene, Ogata’s wife (played by Yukiko Shimazaki)goes to the cinema to see the 1952 French-Italian co-production TheSeven Deadly Sins. However, apart from a few minor details such asthis, the film could almost be set in the 1930s as there is nomention whatsoever of the war or of issues specific to the post-warperiod. Instead, it focuses entirely on the problems of the youngcouple as they try to find ways of paying the bills and avoidinghomelessness while he maintains a writing career and she becomes amother.

Yukiko Shimazaki

Yukiko ShimazakiOzaki was a respected literaryauthor in Japan, but almost none of his work has been published inEnglish. His mentor was the better-known Naoya Shiga, who has severalworks published in English, including the novel A Dark Night’sPassing and the collection The Paper Door and Other Stories.Humour and anger at injustice are said to be among the primecharacteristics of Ozaki’s work, which Mishima reportedly describedas being like ‘Naoya Shiga in a kimono.’ Incidentally, there have beenonly three other films based on his writing: Koji Shima’s Nonkimegane (1940). Tadao Ikeda’s Tenmei Taro (1951) andSeiji Hisamatsu’s Aisaiki (1959), none of which are easilyaccessible.

Shimizu co-wrote the screenplaywith Kozaburo Yoshimura, already a well-established director himselfby then, and this film seems to have been their sole collaboration.Shimizu was at this point dividing his time between making his ownindependent pictures and working for Shintoho. Unsurprisingly for aShimizu picture, it’s an understated piece which avoids melodramafor the most part and has very little plot but plenty of gentlehumour. On the other hand, it’s not one of his most characteristicor memorable films – unlike Tomorrow will be Fine Weather in Japan, for example, which feels like it could only have been madeby Shimizu.

If leading lady Yukiko Shimazaki,who plays Ogata’s rather child-like wife, is unfamiliar, that’sperhaps a symptom of Shimizu’s lack of interest in working with bignames – she was not a major star, although she had been active infilms from 1950 and went on to appear in Seven Samurai. Shewas also a chanson singer and, in 1963, she left the film businessand opened her own chanson bar in Ginza named Epoch, which she ranfor many years. A more familiar face among the supporting cast isJukichi Uno, who plays a kindly landlord and seems to have appearedin almost every shomin-geki made during this period.

Jukichi Uno

Jukichi UnoA note on the title:

Asfar as I’m aware, ‘Mole Alley’ is not an official Englishtitle. While ‘alley’ seems a fair translation of yokocho(which can also be translated as ‘side street’, ‘lane’, etc),mogura can also mean ‘creepers’ or ‘trailing plants’as well as ‘mole’. Mogura Yokocho is the name of thestreet that Ogata and his wife move to, but whether that street isnamed after moles or creepers is unclear.

Bonustrivia:

Threewell-known Japanese writers are glimpsed briefly in the AkutagawaPrize ceremony scene: Fumio Niwa, Kazuo Dan, and Shiro Ozaki (norelation to Kazuo Ozaki).

Japanese DVD to be released 13 May 2026

Thanks to A.K.

January 30, 2026

Their Legacy / 家庭の事情 / Katei no jijo (‘Family Circumstances’, 1962)

Obscure Japanese Film #243

So Yamamura

So Yamamura Junko Kano and Ayako Wakao

Junko Kano and Ayako Wakao Utako Shibusawa and Mako Sanjo

Utako Shibusawa and Mako Sanjo

Uponretiring, widower Misawa (So Yamamura) decides to give each of hisfour unmarried daughters 500,000 yen to do with as they wish. Theeldest, Kazuyo (Ayako Wakao), is regretting having an affair with amarried colleague (Jun Negami) and decides to quit and open a café.Second daughter Fumiko (Junko Kano) gives hers to her boyfriend (JiroTamiya) so that he can pay off his debts. Third daughter Miyako (MakoSanjo) only reluctantly accepts the money and just wants to stay athome with her father. The youngest, Shinako (Utako Shibusawa), worksin an accounts department and decides to become a moneylender whilefighting off the attentions of a persistent co-worker (HiroshiKawaguchi). Meanwhile, Misawa has a relationship with gold-diggerTamako (Murasaki Fujima), although a matchmaker (Haruko Sugimura) istrying to interest him in getting married again to Yasuko (MayumiKurata)*…

ThisDaiei production was based on a magazine serial by Keita Genji(1912-85), whose works were also the source for thepreviously-reviewed Daiei movies The Most Valuable Wife (1959)and Kirai Kirai Kirai (1960), both of which offered similarfare. Like those, this is a light comedy, a genre not typicallyassociated with director Kozaburo Yoshimura or his screenwriterKaneto Shindo (although it was by no means the only occasion on whicheither filmmaker dabbled in comedy). Presumably, then, this was astudio assignment, but it’s well-made and entertaining, and Iwasn’t left feeling they had just phoned it in.

AlthoughAyako Wakao – curiously, the only one who seems to be playing it totally straight – is top-billed, in this case she’s really just part ofan impressive ensemble cast which also features Eiji Funakoshi, KeizoKawasaki and Eitaro Ozawa, most of whom make the most out of thematerial. If you enjoy Daiei films of this era and like these actors,Katei no jijo is an enjoyable time-passer, with Sei Ikeno’sscore helping to heighten the comic effect, although theblack-and-white rush hour prologue and epilogue, while fun, seem abit random to me as I couldn’t really see how they related to themain story. (I could also have done without the close-up of EitaroOzawa eating...)

Jiro Tamiya

Jiro TamiyaIncidentally,in one impressive scene, real-life karate black-belt Jiro Tamiya getsproperly thrown by another real-life karate black belt, Jun Fujimaki,who also appears here playing a love rival to Tamiya’s character.

KeitaGenji’s story was remade by Katsumi Nishikawa for Nikkatsu in 1965as Yottsu no koi no monogatari (‘Four Love Stories’).

*Althoughboth IMDb and eiga.com state that Tamako is played by Yasuko Nakadaand Yasuko is played by Murasaki Fujima, this is incorrect.

Murasaki Fujima as Tamako

Murasaki Fujima as Tamako Mayumi Kurata as Yasuko

Mayumi Kurata as Yasuko

DVD at Amazon Japan (no English subtitles)

Thanksto Coralsundy for the English subtitles, which can be found here.

If you enjoy this blog, feel free to Buy Me a Coffee!

January 24, 2026

Inoru hito / 祈るひと (1959)

Obscure Japanese Film #242

Izumi Ashikawa

Izumi Ashikawa Tsutomu Shimomoto

Tsutomu Shimomoto Yumeji Tsukioka

Yumeji Tsukioka Yuji Odaka

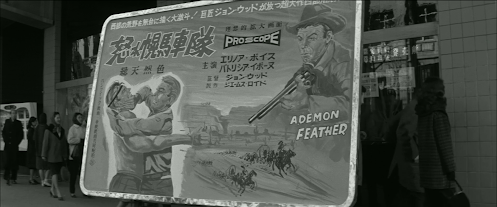

Yuji OdakaAkiko (Izumi Ashikawa) is theonly child of her father (Tsutomu Shimomoto) and mother (YumejiTsukioka) and is approaching marriageable age. She has alwaysregarded her academic father as cold and remote and seen littleevidence of love between her parents, so she’s keen not to make amistake in choosing her own husband. Pressured into going on anarranged date with the boorish Hasuike (Yuji Odaka), she’s far fromimpressed when he takes her to the cinema to see a grade-Z western,but as she begins seriously thinking about her options for thefuture, she finds herself looking back at the past...

ThisNikkatsu production was based on a novel of the same name by TorahikoTamiya (1911-88) originally published as a serial in a women’smagazine the year before. His work is unavailable in English, butalso provided the basis for the previously-reviewed Love is Lost(1956) and Stepbrothers (1957) among other films. Featuringsome voiceover narration from Ashikawa’s character, the filmunfolds in a sometimes confusing flashback structure and wanders offinto some subplots of dubious relevance. However, despite theseflaws, the film turns out to be a surprisingly serious and thoughtfulstory of a young woman finding out who her parents really are –and, by extension, who she really is. It’s also very nicely-handledby director Eisuke Takizawa, who elicits good performances all round and also made the recently-reviewedpicture The Samurai of Edo.

Ona cultural note, there’s a scene in which Akiko visits a barpopular with students where they sing Russian folk songs in Japaneseand all seem to know the words, an odd phenomenon also featured inthe 1956 film Gyakukosen. Incidentally,although there’s a close-up of the poster for the film Hasuiketakes Akiko to at the cinema, I was unable to identify it despitetranslating the text – was it such a low-budget piece of crap thatit’s vanished without a trace or was it a fictional film that neverexisted in the first place?

Inoru hito is sometimes translated (incorrectly in my view) as ‘ThePraying Man’, which I don’t think was ever an official Englishtitle. While the standard translation of inoru is ‘pray’,it can also be interpreted less literally as ‘hope’, while hitois genderless and can be read as ‘person’ / ‘people’ /‘human(s)’, etc. As there's a scene in which Akiko is shown in apraying posture, it seems likely that the title refers to her, andthere’s certainly no male character it could relate to. A betterEnglish title, then, might be ‘One Who Prays.’

Ifyou enjoy this blog, feel free to Buy Me a Coffee!

Film at Amazon Prime Video Japan