Mark D. Jacobsen's Blog

July 18, 2024

Reflections on Paolo Bacigalupi’s “Navola”

Almost twenty years ago, I read a science fiction story that blew my mind. It depicted a dystopian near-future, in which severe drought had depopulated the southwestern United States, states were practically at war with each other over water, and California was enclosing the Colorado River in castle-like fortifications to prevent leakage, evaporation, and theft. The protagonist eked out a meager living collecting government bounties on water-thirsty tamarisk plants. The authorities didn’t know that he was secretly replanting them to safeguard his livelihood.

This was my favorite kind of SF story, with brilliant prose, sharp characters, exquisite worldbuilding, and a tight plot. But I liked it for two other reasons. First, like the novels of Kim Stanley Robinson, it showed deep engagement with this world—which I gradually learned was my favorite kind of SF. Second, it put water competition on my radar as a critical topic worthy of study.

After reading the story, I lost track of it. I couldn’t remember the title or author. Still, those vague dreamlike impressions of U.S. states warring over the Colorado River stayed with me.

The timing was fortuitous. As best I can gather, I encountered a reprint of the story in the May 2007 issue of The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction. One year later, my family and I moved to Amman, Jordan, where I began a two-year Olmsted Scholarship to earn a Master’s of Conflict Resolution at the University of Jordan.

During my time in the Middle East, inspired by the short story, I wrote a lengthy research paper on the history of competition over the Jordan River, which among other things included interviewing a former Jordanian Minister of Water who had negotiated water sharing agreements with Israel. I uncovered a fascinating history as bleak and violent as the short story, with Israel, Jordan and other actors shrewdly outmaneuvering each other for control of the Jordan: diverting rivers, digging canals, bombing waterworks, draining aquifers, and undermining water agreements as soon as they were signed. The competition was slowly murdering the Dead Sea, which is on track to vanish by 2050.

That paper helped get me accepted at Stanford for my PhD in Political Science. It also left me with an enduring fascination with water scarcity. I later read Cadillac Desert, which chronicles the hubris, audacity, and corruption of American efforts to make the southwest desert bloom. Water continually reappears in my own short stories, especially The Weight of Oceans and “Abundance”, a story about efforts to save the Dead Sea.

Rediscovering PaoloLast year I stumbled across Paolo Bacigalupi’s The Water Knife, a science fiction novel about violent interstate competition over the dwindling Colorado River. I bought the book immediately and devoured it in a few days. It was dark, gritty, and bleak—Blade Runner meets Sicario meets Cormac McCarthy. Bacigalupi’s apocalyptic nightmare extrapolates a real-world trendline and would make anyone think twice before moving to the southwest.

The novel felt an awful lot like that forgotten short story. To my delight, I discovered that the author was one and the same. Paolo Bacigalupi’s short story The Tamarisk Hunter (still excellent) had set him on a long journey that culminated in this brilliant novel.

When I finished The Water Knife, I immediately began reading Bacigalupi’s earlier novel The Windup Girl, which won the Hugo and Nebula and several other awards. The worldbuilding is among the most unique I’ve ever encountered, which makes the novel both breathtaking and difficult to penetrate. It is set in Thailand in a barely recognizable future, where biotechnology has supplanted information technology in organizing and shaping human civilization. The novel is just as dark and gritty as The Water Knife, and its themes about climate change, genetically modified food, and corporate malfeasance apparently struck a chord with readers, catapulting Bacigalupi from obscurity to fame.

Although I enjoy science fiction and write it myself, it’s rare that I find SF novels I truly love, so discovering Paolo Bacigalupi was a special treat. When I learned recently that he was releasing another novel, I preordered it immediately.

NavolaBacigalupi’s third adult novel is fantasy, not science fiction, which makes it a courageous departure for an author who has built up certain expectations with his readers. It is doubly courageous because, as a few disgruntled reviewers have observed, it barely qualifies as fantasy; it is set in a fantasy recreation of Renaissance Italy, with only a faint magical luminosity pulsing through its mythology and through a dragon’s eye introduced in the novel’s first chapter. The worldbuilding reminds me of Guy Gavriel Kay, who writes novels reimagining various historical times and places as fantasy worlds. Fortunately, this is exactly the kind of novel I love. I devoured most of this 550-page tome on a single flight from Atlanta to Honolulu.

Everything I love about Paolo Bacigalupi’s writing is here: incredible worldbuilding, rich characters, gorgeous prose, and a skillfully woven plot. The novel also features the gritty brutality that characterizes Bacigalupi’s SF novels. The political intrigue is first-rate and reminded me of both Dune and Game of Thrones; like those works, the novel centers on a young man coming of age in a family that must fight for its survival among enemies who circle like wolves. Young Davico’s relationship with his father is extremely well done, as is his complicated relationship with his sister Celia, forcefully adopted into the family as a means of revenge against an enemy family.

I won’t provide a full review (I liked Gary Wolfe’s), but wanted to mention two themes struck me with unexpected force.

First, the sophisticated mythology and philosophy of Navola differentiates between two dimensions of the world: Cambios and Firmos. Cambios is the world of things built and touched by men, while Firmos refers to the natural world that precedes and transcends mankind. Bacigalupi develops this dichotomy with tremendous skill. Most inhabitants of Navola view Cambios as the proper domain of power and action, but Davico never feels at home there; he prefers to inhabit Firmos, with all its natural power and wild unpredictability. Many characters consequently view Davico as strange and aloof, but we continually see him tapping into a source of power greater than any they can access.

It’s a beautiful artistic representation of a tension I feel constantly in our own real world: between the material and the spiritual, civilization and nature, the visible and transcendent. I have spent my military career immersed in Cambios, studying the laws of power, practicing the arts of war and politics. Yet my constant yearning has been to leave Cambios behind entirely and revel in pure Firmos. The result has been a sense of homelessness in the halls of power. This novel expresses that tension better than anything I have read, and it came during a season when I have specifically sought time in Firmos after long years of immersion in Cambios.

Second, and related, a key theme in the novel is Davico’s struggle with whether or not he has the strength to rule over his father’s commercial empire. Davico was born into a world of ruthless Cambios, but he was also born decent and good. At every step, scheming allies and enemies—and Davico himself—wonder if that disqualifies him from leadership. The novel explores the primal fear—common to all people, but especially men—that one lacks the strength and fortitude the world demands. In the novel this becomes a tangible and practical question, propelling the plot to a brutal reckoning. Along the way, Davico must grapple with his weaknesses and also discover his own unique forms of strength.

I opened the novel expecting to be entertained and mesmerized. I did not anticipate the degree of reflection the book triggered. I remain a huge Paolo Bacigalupi fan, and look forward to seeing where he goes next.

July 11, 2024

Day 21: The Wilderness Cathedral

Cathedral Peak is the second of three “easy” alpine peaks in Tuolumne that constitute the Triple Crown. John Muir wrote that it had more individual character than any mountain he’d seen except Half Dome. In My First Summer in the Sierra, Muir wrote:

No feature, however, of all the noble landscape as seen from here seems more wonderful than the Cathedral itself, a temple displaying Nature’s best masonry and sermons in stones. How often I have gazed at it from the tops of hills and ridges, and through openings in the forests on my many short excursions, devoutly wondering, admiring, longing! This I may say is the first time I have been at church in California, led here at last, every door graciously opened for the poor lonely worshiper. In our best times everything turns into religion, all the world seems a church and the mountains altars.

Today, after two rest days in Tuolumne, we plan to follow in John Muir’s footsteps. Today we aim to climb Cathedral Peak.

—I am still smarting from turning back from Tenaya Peak, the easier climb. I know we could have done it, but it didn’t feel wise. We were tired, Hannah was a newer climber, and I had never led anything of that scale.

Cathedral Peak is a little harder, but there is a big difference today: my friend Knight Campbell, an experienced mountain guide and the CEO of Cairn Leadership, reached out about doing a climb together. He offered to lead. This is exactly what I need: an experienced partner. He brings the experience and judgment I lack, can teach me a few tricks as we go, and can guide me through my first technical mountain climb before I lead my own. Hannah and I are also eager for the simple pleasure of climbing socially with a friend.

—The approach trail is easier than Tenaya. The length and grade feel comparable, but the trail is well-groomed and the mosquitos are marginally better. Still, it’s a workout. We stop to refill water where the trail approaches the river, then make the last strenuous hike up to the base of the peak. We’re huffing and puffing by the time we arrive. Climbing, ironically, will feel easier.

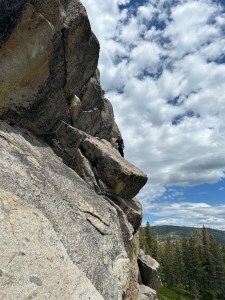

Cathedral Peak is stunning, a sharp fin of granite tapering to a fine point 700 feet above. Ample cracks and features offer myriad pathways up the rock. We see a couple parties ahead of us, and meet another group descending a trail that winds around the peak.

Knight wastes no time. The moment we arrive, he begins flaking his rope. We follow suit. Knight is on a schedule today. After our climb, he will hike into a backcountry campground to join his family for a backpacking trip. Guidebooks suggest the climb can be done in 5 to 7 hours, but I have warned Knight that Hannah and I will likely be slow. He assures us we can take as much time as we need, but we still feel obligated to help him stay on schedule.

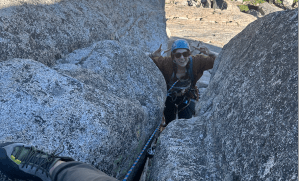

We climb caterpillar-style, which means we use two ropes to chain the three of us together. Knight leads, I follow, and Hannah trails behind. After quick safety checks, Knight starts the first pitch. He moves swiftly and deftly upwards. I’m shocked by how little protection he places. He makes long runouts between cam placements, which would make a fall a significant event. This is a product of his experience, and has the benefit of allowing him to climb fast and make long pitches without running out of gear.

After he completes the pitch and sets up a belay, I follow his route. I climb without trouble, and don’t fall once during the day, but I’m still glad he’s leading. I could lead this, but I would place far more gear and would likely need to make additional pitches.

The climbing itself feels amazing. The route is interesting and varied, offering a wide range of climbing styles, from finger-cracks to face moves to off-width chimneys. The views are breathtaking. This is exactly what I wanted my last day of this trip to be: an epic adventure, bigger than anything I’ve climbed before, taking me into new territory.

—We reach a bottleneck at the off-width crack. We arrive at the belay station just behind another couple, so have to wait for them to clear out. While we wait, two fast simul-climbers reach the belay ledge and ask if they can pass us. We agree, which further delays us. It’s probably for the best; with three climbers, we’re the slowest group up here. Knight hoped to complete each pitch in roughly 30 minutes, but by the time we get to the uppermost pitches, we’re running more like an hour.

The fifth pitch is supposed to be the last, but from the belay ledge, I can’t see up over the next feature. I try to read Knight’s motions by the movement of the rope, which communicates a surprising amount of information. Towards the end of the pitch, the rope does funny things. I feed him a ton of slack, then take a ton of rope in, then feed him more slack. I have no idea what he’s doing up there.

I understand once I finally climb up to join him. The climb doesn’t taper up to a point; instead, we have to navigate around big, heaped blocks of stone to clamber our way to the summit. They looked like stacked children’s blocks. Our route requires belly-crawling over a stone ledge, descending down a ways, then climbing other blocks to the summit. The summit itself is the size of a dining room table. I find Knight sitting happily at the top, legs dangling over the edge, three cams wedged in a crack behind him. I clamber up next to him, clip in, and soak in the views while Hannah climbs up behind me.

This is the most visually stunning hike or climb I’ve ever done. Hannah, breathless, plops down next to me. I wish she could stay longer to savor the views, but another party is queued up behind us. We give her a few minutes, then rig our ropes to descend back down.

—Descents intimidate me more than anything about big multi-pitch climbs. Climbers have access to clear maps, photos, and textual descriptions of ascents, but getting down again always seems like a poorly-documented afterthought. Prior to this climb, I spent hours trying to mine nuggets of information out of climber reports. I gathered that the descent from Cathedral Peak could be sketchy.

The uppermost moves are definitely intimidating, as they involve downclimbing through exposed terrain. Fortunately, Knight belays us, which removes all the risk for us. Next, we have to circle around the summit and descend down steep slabs towards a feature called the Eichhorn Pinnacle. This unexpectedly proves to be the most terrifying section of the day’s adventure. The slabs are highly exposed, with scary fall potential. Many moves feel precarious. The trail isn’t clear, so we repeatedly have to make calculations about the safest way through sketchy terrain. Knight sets up a short rope system, which means we are tied together but not anchored to the rock; if one of us falls, the others should be able to arrest their fall. In practice, it feels like there’s a risk that one of us could pull the other two off a slab and send us tumbling down.

Our descent is painfully slow. Knight moves through the terrain like a mountain goat, but Hannah and I are less sure of our footing. We are both acutely aware of the passing time. The more time we take here, the longer before Knight can catch up with his family on the backpacking trail. The sun is also getting low on the horizon. Still, there is no rushing.

I’m very glad I didn’t try leading this climb on my own. The climbing would have been okay, but this descent would have left me at a loss. A party behind us sets us up a rappel. I probably would have done something similar.

Eventually we make it down to the trail at the Eichhorn Pinnacle, where we have to clamber uphill again over a ridge and then descend the other side of the mountain. This part of the trail, though not treacherous, is cumbersome. Then, at last, we find ourselves on a well-marked trail that descends stone staircases alongside the face we just climbed. At last we reach the ground and commence the two-mile hike back to civilization.

—By the time we reach the van, what we hoped would be a 5 to 7-hour climb has turned into an 11-hour saga. Everything has gone smoothly; we are just slow. I feel bad, but this is what it is. Knight seems eager to get back but is also unperturbed. We’re having fun out here, it’s a gorgeous day, and this climb was spectacular.

My lingering frustration about not climbing Tenaya Peak finally dissipates once and for all. I wanted to end my Sierra Nevada trip with a climb that stretched my abilities. This was exactly what I needed: safe, fun exposure to a new kind of climbing, in the company of a friend and experienced guide. This day feels like a breakthrough. We’re tired, sore, and exhilarated in the best possible way. That is exactly how I wanted to feel before my trip concluded.

We’ve done what we came to do. Now we can think about going home.

July 9, 2024

Day 20: The Call to Return

Our second day in Tuolumne, like the first, begins early. I roll out of bed at 4:00am, drive into Tuolumne to beat the 5am reservation-only window, and go back to bed. Sleep proves elusive. I’m torn about whether to try Tenaya Peak again, after our aborted attempt yesterday. We should have decided this last night, but I felt too tired to make a decision and deferred it to morning. Now I’m still not sure.

I want the climb so badly, but I’m not feeling good about another attempt. Nothing would really be different from yesterday. We also have a major climb planned for tomorrow, up Cathedral Peak, with a friend who is an experienced mountain guide. It wouldn’t be wise for us to climb two mountains in a row without a rest day. Even so, I feel sad and frustrated at my inability to climb this peak. I can’t shake the feeling that I’m failing somehow.

Dawn brings a sobering realization: after almost three weeks of van life in the Sierra Nevada, I’m tired. Every single day of this trip has been amazing and life-giving, but life on the road takes a cumulative toll. That is now manifesting as physical fatigue, as well as emotionality and indecisiveness. That alone, I know, is a good reason to stay on the ground today.

—When we first embarked on this trip, Hannah and I wondered how we would feel at the end. Would we be ready to return home, or would we want to stay on the road forever?

I suppose I have my answer. As much as I love this trip and want to steer my life towards places and activities like this, I’m beginning to yearn for stability and routines.

More than anything, I miss my kids. They are back in the U.S. after two amazing weeks in Tanzania, and are now staying for a third week with my ex-wife’s extended family. It’s the longest we’ve been apart in a decade. Later, sitting by Tenaya Lake, I watch a family enjoying their vacation. Dad floats in the glacial water with the kids, while mom lays out a picnic lunch. They look so happy, sun-browned, carefree. The sight opens a wellspring of emotion in me. There is so much goodness in my life now, so much momentum in this new season of my life, but so much brokenness still lies beneath the surface; I feel it every day, an arthritic pain that will never go away. I’m ready to be with my kids again.

I also miss the comfort of routines. On this trip I achieved exactly what I set out to do: embrace my alter ego as a writer who loves nature and sees life as a spiritual journey, write daily for myself, and share that writing with others. While this has been liberating, it’s also detoured me away from my core writing projects, specifically my book on belonging. I’m ready to get back to it, and that will be easier at home.

Finally, new adventures await. In a month, I will start a new job that will exercise my skills and abilities in entirely new ways. The flexibility and freedom in this new season will, I hope, allow me to write more seriously. My oldest son will turn 16 and start driving. A new school year will start. My children have extensive activities lined up. I’m excited to see how my relationship with Hannah develops, and we are already planning a range of family activities. Life is calling us back.

—I have been here before: yearning to remain on vacation forever, but feeling the inevitability of return, gathering on the horizon like a weather front.

This trip has always only been a transition period, an intermission between chapters of my life. Time and inertia are sweeping me forward, and stubbornly clinging to this trip would be unnatural and self-defeating. I need to let go, to trust this river sweeping me onward.

That is what I’m feeling today, I think: the need to slow down, to savor these last days, and to prepare for our return.

I do my best to let Tenaya Peak go. We sit on the beach beside Tenaya Lake, with our books and journals, taking in the lazy morning. Later, we go for an easy hike around Tuolumne Meadow. I keep looking back at the towering mountain. I feel deeply conflicted, but I also know the mountain isn’t going anywhere; we can return someday.

And we aren’t quite done yet. Tomorrow will be our biggest challenge of this entire trip, the capstone, the culmination of all our climbing: scaling Cathedral Peak.

July 8, 2024

Day 19: A Hard Reckoning

Up to this point, everything on this trip has gone amazing. I feel tremendous momentum, as if all the benevolence of the universe is with us, filling our sails and propelling us forward.

It was bound to happen sooner or later: the setback, the crash, the collision between unstoppable momentum and an immovable object.

That immovable object proves to be Tenaya Peak.

—For years I have wanted to see Tuolumne, a high-elevation region in the northeastern portion of Yosemite Valley. The beauty of this area is legendary: lush meadows, granite domes, and the winding Tuolumne River, tucked away in the subalpine heights, far from the crowds and traffic jams in Yosemite Valley. The National Park Service’s webpage for Tuolumne opens with a fitting quote from John Muir:

Walk away quietly in any direction and taste the freedom of the mountaineer. Camp out among the grasses and gentians of glacial meadows, in craggy garden nooks full of nature’s darlings. Climb the mountains and get their good tidings, Nature’s peace will flow into you as sunshine flows into trees. The winds will blow their own freshness into you and the storms their energy, while cares will drop off like autumn leaves.

Tuolumne is also home to phenomenal rock climbing, including three relatively “easy” alpine mountain climbs: Tenaya Peak, Cathedral Peak, and the Matthes Crest. All three can be linked in a day by strong climbers, a feat known as the Triple Crown. In the runup to our trip, I studied all three routes. I read guidebooks and watched YouTube videos.

Although Hannah and I were still relatively new to multi-pitch climbing, I thought these peaks would be within our abilities. They would be bold, huge, and intimidating, making them a fitting climax to our trip. Before we returned to Alabama, I wanted to accomplish something that would take me to my limit.

—I set my sights on the Northwest Buttress of Tenaya Peak, supposedly the easiest of these three classic climbs. The hardest pitch is only 5.5, which is well within my limits, and most pitches are even easier. However, the route is 14 pitches and gains 1400 feet, which is monstrous compared to any technical climb I have done. Completing the climb would require not just raw climbing skills but the ability to tackle a long approach hike, navigate an ocean of granite, make decisions in an austere and unforgiving environment, and find my way down a long descent trail at day’s end.

All this intimidates me, but I feel quiet, easy confidence. I know I have the ability to safely climb this mountain. I often shirk back from the boundary edge of my abilities, afraid I won’t be up to the challenge. This formidable mountain poses a question: whether I will trust myself. This time, I’m resolved, the answer will be “yes.”

—Shortly before our arrival, I realize I made a rare planning mistake: I forgot that Tuolumne Meadows actually sits within Yosemite National Park. In June, Yosemite only required entry reservations on Saturday and Sunday. In July that changes to every day. It’s July now, and reservations are sold out.

Fortunately, the park offers a sensible option that limits the crowds in Yosemite while still allowing dirtbag adventurers virtually unlimited access to the park: visitors don’t need a reservation if they enter before 5am.

We leave our RV park at 3:30am. I make a bleary-eyed drive up the winding mountain road, past the deserted Yosemite entry booth, and towards Tenaya Lake. It is utterly dark; the sky is full of stars. I keep my focus on the winding two-lane road, but I can sense gigantic shapes rising up around me and am acutely aware of the black void to my left. This landscape must be breathtaking. I can’t wait to see it.

I park beneath Tenaya Peak, slouch back to my bed, and go back to sleep.

— My alarm rouses us at 8:00am, the latest I want to embark on this climb. We rub our eyes, make coffee, and grab our climbing gear. Then we step outside and get our first glimpse of Tuolumne.

My alarm rouses us at 8:00am, the latest I want to embark on this climb. We rub our eyes, make coffee, and grab our climbing gear. Then we step outside and get our first glimpse of Tuolumne.

Tenaya Peak is immense, shining white overhead. It evokes my feelings of looking up El Captain. It’s only half as tall, but that’s still huge. Unlike El Capitan, which is starkly vertical, this granite sea is sloped, which is what supposedly makes the climb accessible to someone like me. Despite the peak’s formidable size, I feel good. We can do this.

We start up the two-mile approach trail, which gains considerable elevation through a series of overgrown deer paths, switchbacks, and low-angle slabs. Our good feelings quickly sour. I’ve never seen this many mosquitos; twenty or thirty cling to our clothes at a time, and we’re constantly swatting them away from exposed skin. We’re both feeling the elevation and the morning heat; after twenty minutes of hiking, I’m dripping with sweat. We both have daypacks and climbing gear, and I’m hauling a heavy rope over my shoulders. We’re also tired from our early-morning drive into Tuolumne.

At one point, we lose the approach trail. We need to go back down, I conclude. We have to make a sketchy move on wet, slippery granite. It’s only a few feet, but a fall would entail tumbling down the next slab. I take the time to set up a belay. It’s awkward and time-consuming. No sooner do we get down than another couple appears, telling us we had it right the first time; the trail continues above us. We climb back up the sketchy move, this time without the benefit of a belay. The back-and-forth leaves me tired and shakes my confidence; if I can’t navigate the approach trail, how will I routefind through 14 pitches of rock? We’re also chugging through our water quickly, and we aren’t even on the climb yet. We stop to filter water, which leaves us at the mercy of mosquitos. Hannah’s patience is cracking; she wants to charge ahead, away from the mosquitos, but without rests we’re both getting tired.

Two hours after we set out, we finally arrive at the granite slabs marking the start of what I think is the first pitch of the climb. We’re exhausted, covered in bites, sweaty, and emotionally rattled. We need to rest, but rest means a feast for the mosquitos. The path ahead is all exposed slabs, with easy walking but the potential for long falls. I feel ill at ease. A long way ahead, I can see climbers gathered beneath a tree that marks the start of the second pitch. Above that it’s pure granite.

Hannah and I look at each other silently, inquiring. We’re both in the same headspace: fatigued, sketched out, swamped with negative emotions. “I’ll keep going if you want,” Hannah tells me, but I know she doesn’t want to. I don’t either. Not today.

We turn around.

— The onslaught of negative self-talk is immediate and relentless. I ache with self-loathing. I feel worthless, cowardly, a failure. This is supposed to be an easy climb. I know I can do it; the only thing holding me back is my own lack of confidence.

The onslaught of negative self-talk is immediate and relentless. I ache with self-loathing. I feel worthless, cowardly, a failure. This is supposed to be an easy climb. I know I can do it; the only thing holding me back is my own lack of confidence.

“Jacobsen is a whiny sissy,” begins the harshest review I’ve ever received for my book. I stopped reading right there, but those words lodged in my brain like a splinter. They perfectly embody one of my deepest fears: that I’m not strong enough, that I’m singularly weak or fearful.

I have come a long way over the years, recognizing these disparaging internal monologues, analyzing them, and leeching them of their power. I wonder why these thoughts and feelings are attacking so strongly now. Why is it, I wonder, that my feeling of self-worth is bound up in climbing a mountain peak that would utterly terrify most people? Clearly, this is unhealthy. I wonder what I am trying to prove, and to whom. The only coherent answer is myself.

I’m frustrated and angry, trying to swim my way out of the black whirlpool of emotions. I know I’m being irrational. I know this response is deeply unhealthy, and that it’s pointing me towards something important I need to learn about myself. Maybe that is today’s task, I think: to battle this demon, to face something in myself even harder than the mountain.

—A short ways into our descent down the approach trail, we meet two climbers on their way up. They look like brothers, lean and strong, wearing sunglasses, day packs, and identical sun shirts. When they ask us about our plans, I sheepishly tell them we’re bailing. I’m embarrassed, I say, but we weren’t in a good headspace to do the climb.

Their tone changes immediately: they become overwhelmingly kind, gracious, and encouraging. Bailing is normal, they say. They do it all the time. The guidebooks might advertise easy climbing, they say, but climbing in an alpine environment is radically different than crag climbing. They applaud our decision and offer thoughts on other, easier climbs. We learn they are Yosemite Climbing Rangers, which sounds like the best job ever. Their names are Eric and Gus, and they are the kindest and most encouraging people I’ve ever met on the trail. They arrived at a crucial moment, like angels.

I feel marginally better. We continue down, through the mosquito-infested forest, to our van.

—Hannah and I spend the afternoon at Lake Tenaya, where the breeze keeps the mosquitos away. We don’t feel like climbing; instead, we read and nap in our hammock. It is a perfect day, a day of unexpected, blissful rest in each other’s arms in one of the most beautiful places in the world.

I try so hard to fully relax into the beauty of the day. Even as I savor this beautiful togetherness, I can’t quite shake the demons. They still prowl in the shadows, whispering hate. My eyes keep drifting up to Tenaya above. We discuss possibly trying again tomorrow; now that we know the approach, we’ll be in a better headspace.

We depart early to find a dispersed campsite. A helpful app leads us into the Inyo National Forest, which doesn’t look much like a forest at all; it’s a bleak landscape of gravel, dirt, and desert shrubs. I feel cranky. I don’t want to camp in a dirt patch in the desert, but that’s exactly where we end up.

I turn off the engine and climb out of the van. Almost immediately, my feelings change: it is truly beautiful here. We are utterly alone in this desert wilderness. The sky is enormous. Mountains range from north to south as far as we can see, layered behind each other, some of them snow-capped. It looks like Middle Earth. It’s warm, but pleasantly so; we’re still at considerable elevation.

I turn off the engine and climb out of the van. Almost immediately, my feelings change: it is truly beautiful here. We are utterly alone in this desert wilderness. The sky is enormous. Mountains range from north to south as far as we can see, layered behind each other, some of them snow-capped. It looks like Middle Earth. It’s warm, but pleasantly so; we’re still at considerable elevation.

We cook dinner and open a bottle of wine. The quiet is incredible. Our spirits settle as we yield to the stillness. We sit on a rock and watch the sun go down over the mountains to the west; they are shrouded with haze, each successive peak a lighter shade of blue than the one before. We talk for hours, about everything under the sun.

I can tell already that this will be the darkest sky I’ve seen in years. We are miles from anything, and tens of miles from a city of any respectable size. The moon won’t rise until 3:00am. We lay a blanket and sleeping bags out on the sand. The stars begin to appear, Arcturus and the handle of the Big Dipper at first, then others I don’t know. Thousands of smaller, fainter stars fill in the remaining emptiness. The Milky Way reveals itself as the last blue light melts into the mountains, a winding river low over the horizon, so faint I can’t be sure it’s real.

I can tell already that this will be the darkest sky I’ve seen in years. We are miles from anything, and tens of miles from a city of any respectable size. The moon won’t rise until 3:00am. We lay a blanket and sleeping bags out on the sand. The stars begin to appear, Arcturus and the handle of the Big Dipper at first, then others I don’t know. Thousands of smaller, fainter stars fill in the remaining emptiness. The Milky Way reveals itself as the last blue light melts into the mountains, a winding river low over the horizon, so faint I can’t be sure it’s real.

Hannah curls into me. I teach her constellations. We watch for shooting stars and count satellites. We are alone in the universe, and the stars are our own private possession.

—I wonder what I learned this day.

I confronted something in myself I don’t like, a painful but necessary reckoning.

But I also learned something about relaxing control. I failed to climb a mountain; the ensuing space became fertile ground for Hannah’s and my relationship. This unexpectedly became a day for us. I could never have planned something like this, with so many magical unfoldings. To appreciate these little miracles I needed to be still, quiet, and receptive to serendipity.

I’m not sure how to put all these disparate pieces of the day together. But maybe I don’t need to; maybe lying here beneath these stars, marveling at the mystery of it all, is enough.

July 7, 2024

Day 18: The Art of Departure

It is a day of departures.

We spent the first few days of our Sierra Nevada trip in Truckee. After leaving to spend time in Yosemite, we missed Truckee so much that we returned for several more days. Those day were magical, allowing us to settle into the place in a deeper way, but now it’s finally time to move on. We want to visit one more destination on our Sierra Nevada Trip: Tuolumne Meadows, the high country in the northeast portion of Yosemite Valley.

I deliberately planned this trip to be a transitional event in my life: the end of one chapter, the beginning of another. Over the past few ways, I have asked what it means to truly arrive in a place—to wholeheartedly commit, slow down, observe, and learn. Our time in Truckee became an experiment in arrival, a rehearsal for whatever arrivals will mark my entry into a new season of life.

Now I find myself contemplating what it means to intentionally depart a place. The easy thing would be to simply jump in the van and leave. I want better than that; I want a departure that both honors this place and safeguards it in my memory.

We make our last day in Trucke slow by design. After visiting the Donner Summit Tunnels, and paying homage to Steinbeck’s Lee and the Chinese railroad workers he represents for us, we string up a hammock between two pine trees on a granite dome overlooking the Donner Summit Bridge. We read in the warm sunlight, with the valley sprawled out beneath us. The breeze occasionally carries the voices of climbers on the granite walls above us. Eventually we drift off into naps, curled together in a tangle of limbs. It is a perfect moment, of absolute stillness, with all our senses absorbing the fine details of this spectacular summit.

Afterwards, we head to Good Wolf Brewing, which a barista at the local coffee shop recommended. The brewery is small, cozy, with earthen tones and stone pillars. We order flights of local beers and sit and process everything we’ve experienced over the past two weeks. It feels like a fitting way to say our goodbyes.

In the morning we make one last visit to our beloved coffee shop, then start our drive. It’s a long descent out of the mountains, which somehow feels symbolic. The temperature steadily increases. Alpine beauty fades to desert. Billboards for personal injury lawyers appear like blight. We enter Reno, the biggest city east of the northern Sierra, the artery of civilization that nourishes and sustains human life in these spectacular mountain places. It feels uninspiring. I remember what a mountain guide told me, near the summit of the Grand Teton, sweeping his arms around at the majestic peaks: “THIS is civilization.”

After Reno is Carson City and then nothing: just vast stretches of desert, choked with dry shrubs, pale green or yellow or almost blue in the harsh sunlight. Perhaps calling all this “nothing” is unfair; perhaps I simply haven’t learned to see what this new place offers. We are in a new climate, a new biome, a new place that must be met on its own terms.

We arrive early at a small RV campground in Bridgeport, a meager town that serves as a highway stop between other, more important places. We dock like a ship entering port. We replenish fresh water, dump our sewage, do laundry, and take real showers, which is a special treat; our usual “dirtbag” showers entail shivering outside the van, sponging ourselves down while dribbling water from the van’s limited fresh water supply.

It is a lovely little oasis in our journey. We are in a space between worlds, having departed one place but not yet arrived in the next. Tomorrow will be Tuolumne: alpine beauty again, real mountains, and hopefully the biggest and hardest climbs we’ve yet done. A new arrival.

July 6, 2024

Day 17: Steinbeck, Lee, and the Chinese Railroad Workers

When we returned to Truckee, I committed to learning about the place. I wanted to be more than a tourist. I wanted to learn something of the history, culture, geology, and biology of this town that Hannah and I love so much. Reading about the Donner Party seemed like a natural place to start, which led me to purchase The Best Land Under Heaven. We also visited the Donner Memorial State Park Museum. We browsed the various exhibits recounting the dreadful history of the Donner Party, which nicely complemented the book, but it was a separate exhibit on the construction of the Transcontinental Railroad that truly caught my attention.

In the late 1860s, thousands of Chinese migrants converged in the uppermost heights of the Sierra Nevada near Truckee, to build the most difficult stretch of the Transcontinental Railroad. It was grim, difficult, and dangerous work. Track wound along precarious mountain summits. In numerous places, these migrants had to blast their way through solid granite using black powder. When that proved too slow, demanding administrators introduced nitroglycerin. As many as 1,200 Chinese migrants lost their lives. What they accomplished was extraordinary: the completion of a railway through some of the most hostile terrain in the country, a feat that many experts considered impossible. A transcontinental trip that used to last months could now be completed in days. This iron weaving came just years after the Civil War, during a time of healing, reconstruction, and reunification of a broken country.

I knew the general contours of this history, but like most Americans, never gave it much thought. My U.S history textbook in high school mentioned the terrible conditions under which Chinese railroad workers constructed American railroads. At Stanford, my kids and I took a moment to marvel at the golden spike, which Leland Stanford ceremoniously hammered into place, completing the railroad.

However, an exhibit at the Donner Memorial State Park Museum triggers another association: one that hits closer to home.

—Back at the van, I fish out my Kindle and search through my digital copy of East of Eden, my favorite novel.

East of Eden is a magisterial book, as weighty as scripture, spanning multiple generations in a profound contemplation of the human condition. Each character speaks to me in different ways, but one of my favorite characters in the book—perhaps in all of literature—is Lee, the free Chinese servant of Adam Trask, one of the book’s main characters. When Lee first appears, he speaks pidgin, a dialect that evokes all the worst stereotypes of Chinese migrants to the U.S. Later, we discover that Lee is a sophisticated autodidact who speaks English not just fluently but eloquently. Lee is a genius, well-versed in many academic disciplines and gifted with deep emotional intelligence and a keen understanding of human nature. Even so, he shows extraordinary humility as well as loyalty to the Trask family.

Like Mark Twain’s humanizing depiction of Black slaves and fierce criticism of slavery, Steinbeck’s depiction of Lee feels ahead of its time. Lee speaks pidgin in public, he says, because that’s all most people can see and hear: “Pidgin they expect, and pidgin they’ll listen to. But English from me they don’t listen to, and so they don’t understand it.” Steinbeck seems acutely aware of his society’s deep prejudice against Chinese-Americans, and he endows Lee with traits that showcase the best of humanity.

Lee’s wisdom, empathy, and sensitivity to the goodness and suffering of the human condition do not come out of nowhere; they were forged in hardship. In Chapter 28, during a conversation with Adam Trask about whether Adam should disclose a difficult truth to his boys, Lee recounts his father sharing the terrible truth behind Lee’s birth.

This is the passage I vaguely remember, as I look at the museum poster board with its grainy photos and captions about Chinese railroad builders. There is a connection here.

I find it quickly. Describing his parents’ migration from China to the U.S., Lee says, “In San Francisco the flood of muscle and bone flowed into cattle cars and the engines puffed up the mountains. They were going to dig hills aside in the Sierras and burrow tunnels under the peaks.”

This is it! This is the connection I was grasping for. Lee’s parents toiled in these very mountaintops, above the town of Truckee, near Donner Summit. I can see their handiwork every time Hannah and I climb here. Each time we clamber up onto the slab of School Rock, we can see the ugly serpentine tunnel wending its way through the opposing rock face, just beneath Donner Peak.

Previously, I held the tunnels in contempt. I saw them as symbols of bold visions sold by fortune-seeking developers. I have read so much about the environmental calamities unleashed by entrepreneurial humans in these mountains, like the drowning of the Hetch Hetchee Valley behind the O’Shaughnessy Dam. Developers even wanted to drown Yosemite Valley, a crime against nature so terrible that it makes me shudder; thank God other voices prevailed. These tunnels seem to fit that pattern: festering wounds carelessly blasted through pristine granite older than human history. I understand their existence—human civilization always requires compromises with wilderness—but every time I look at them, they remind me that our taming of wilderness entails a price.

Now, lifting my eyes from the pages of East of Eden, I see the tunnels in a different light. They have just flared to life in my imagination. They are now imbued with a story.

— Accessing the tunnels is easy. AllTrails includes a Donner Tunnels Hike, which appears to run in a straight line for a mile and a half. When we first arrived in Truckee, Hannah’s local friend told us to avoid the tunnels, which she described as a filthy eyesore. We agreed.

Accessing the tunnels is easy. AllTrails includes a Donner Tunnels Hike, which appears to run in a straight line for a mile and a half. When we first arrived in Truckee, Hannah’s local friend told us to avoid the tunnels, which she described as a filthy eyesore. We agreed.

The Lee connection changes everything. Not only is East of Eden my favorite novel, it holds a central place in Hannah’s and my relationship. Our romance began to flare when a friend pointed out her tattoo of the world TIMSHEL, a reference to the novel. When we began dating, Hannah and I read the novel again, as well as the journal Steinbeck kept while writing it. We met at Prevail Coffee dozens of mornings to discuss our insights.

There’s no choice in the matter: we need to visit the tunnels. We need to visit Lee’s family history.

—I feel self-conscious, developing such a powerful connection with a place via a fictional character, when so many real human beings lived, labored, suffered, and died here. But perhaps that is what fiction offers: it distills human experience into Story, a pure and essential form that our minds and hearts are hardwired to latch onto. A heartfelt attachment to an entire people is too much to hold, but an attachment to one well-crafted individual comes easily. That individual stands as a representative, holding everything else.

Still, if Hannah and I are going to make a pilgrimage to the railroad tunnels at Donner Summit, I owe it to those real, historical Chinese railroad workers to learn more of their history. I return to Word After Word Books, where I pick up the best single-volume history available: Ghosts of Gold Mountain: The Epic Story of the Chinese Who Built the Transcontinental Railroad by Gordon H. Chang, a history professor at Stanford, my alma mater, another connection. The book grew out of a six-year, cross-disciplinary effort to painstakingly recover a history that had largely been lost and forgotten.

The bookstore’s owner, Andie, spots the book in my hand. “That’s a fantastic book,” she tells me. We chat a bit, and I ask her if she’s read East of Eden. To my delight, she has. I tell her about Lee’s parents, about the connection to Donner Summit. I’m eager to tell anyone who will listen. My googling hasn’t yielded any mention of the connection. I feel as though I’ve stumbled across a forgotten treasure.

—I wonder if I’m imagining all this. Perhaps there were other summits, other tunnels. I wonder how much Steinbeck knew, where he lived, what influences shaped this particular chapter of this novel.

I discover that Steinbeck lived on Lake Tahoe for two years, early in his writing career. Very little is known of these years. He worked odd jobs without enthusiasm, then wrote his first novel during the winter snows.

Tahoe would have put him in close proximity to Truckee and Donner Summit. He was here. He knew.

— The Tunnels are, as advertised, an eyesore. The AllTrails route begins in a dirt lot at the mouth of one tunnel opening. The amount of graffiti is staggering; every surface is covered, layered like geological sediment. In any given tunnel section, one could scrape through the brightly colored spraypaint to travel backward through time. The visible layer broadcasts today’s concerns. FUCK NETANYAHU, I read as I enter the tunnel.

The Tunnels are, as advertised, an eyesore. The AllTrails route begins in a dirt lot at the mouth of one tunnel opening. The amount of graffiti is staggering; every surface is covered, layered like geological sediment. In any given tunnel section, one could scrape through the brightly colored spraypaint to travel backward through time. The visible layer broadcasts today’s concerns. FUCK NETANYAHU, I read as I enter the tunnel.

According to East of Eden, Lee’s father grew up in a small village in the Cantonese-speaking region of southern China. When he fell into debt, his family repaid it. Now obligated to his family, Lee’s newly-married father repaid them with a signing bonus he earned by agreeing to work in the United States. Midway through the ocean crossing, Lee’s father discovered that his bride had smuggled herself aboard, disguised as a man. Only once she was aboard did she learn she was pregnant, which put them both in great danger. When the railroad company learned she was a woman, it would not treat her kindly.

Lee’s parents arrived on the California coast, then found their way up into the heights of the Sierra Nevada.

They likely arrived on this very mountain top, working this very tunnel.

— The first tunnel feels the oldest: a black maw blasted and carved out of the mountain, leaving blocky unfinished edges behind. It took an entire crew of Chinese railroad workers a full day to advance a few inches. The floor is uneven. A trickle of water dribbles through. We sweep our flashlights over the walls, studying the graffiti, which is appalling but also breaks up the endless, monotonous dark. Endless names and initials. “JESUS” and a cross, Christian vandalism, always amusing. BUSH DID 9/11. TRANS IS BEAUTIFUL.

The first tunnel feels the oldest: a black maw blasted and carved out of the mountain, leaving blocky unfinished edges behind. It took an entire crew of Chinese railroad workers a full day to advance a few inches. The floor is uneven. A trickle of water dribbles through. We sweep our flashlights over the walls, studying the graffiti, which is appalling but also breaks up the endless, monotonous dark. Endless names and initials. “JESUS” and a cross, Christian vandalism, always amusing. BUSH DID 9/11. TRANS IS BEAUTIFUL.

The tunnels are poorly cared for. They are on private property belonging to the Union Pacific Railroad but are not well maintained. Locals have been fighting to protect these tunnels as a national landmark, but they have not yet been successful; there are too many colliding interests. Union Pacific has never officially opened the tunnels for public access, partly due to liability concerns, even as it turns a blind eye to the hundreds of tourists who hike here each day. I wonder how they ensure the structural integrity of tunnels. Maybe they don’t; maybe one day a catastrophic collapse will bury tourists. The neglect of this place adds to the air of sorrow: a forgotten history, a forgotten people.

I imagine Lee’s parents here, slaving away in the dark, swinging hammers or setting explosives. In the later tunnels, which are fortified with more modern concrete slabs, we encounter thin gaps and windows. Outside, beyond the endless dark, is indescribable beauty: lush meadows bright with wildflowers, neighboring granite peaks, pine forests fiercely clinging to their slopes. These views must have been both a blessing and a torment to the Chinese laborers within these tunnels. Such stark beauty so close at hand, and so unattainable.

Lee’s parents, laboring in the underbelly of these mountains, knew they must escape before others discovered their secret. They hatched a plan, stashing away rice and scraps of clothing, fashioning fishing line and hooks. When they were ready, they would flee to some alpine meadow, where they could fashion a home for themselves and prepare for the baby.

Their hope was beautiful, fragile, desperate. Every time his father told the story, Lee says, he yearned for the outcome to be different. Just once, he wanted this fairy tale ending to come true.

— The third tunnel goes on forever. This one feels modern, with straight edges and beams framing the rockpiles on the inner wall. We wonder about the history of drilling and improvement. There is no one to ask, no signboards offering explanations. It feels like an abandoned subway in a post-apocalyptic film. The only variation on the endless walk is the graffiti, but even that starts to feel repetitive. We smell urine.

The third tunnel goes on forever. This one feels modern, with straight edges and beams framing the rockpiles on the inner wall. We wonder about the history of drilling and improvement. There is no one to ask, no signboards offering explanations. It feels like an abandoned subway in a post-apocalyptic film. The only variation on the endless walk is the graffiti, but even that starts to feel repetitive. We smell urine.

Eventually, somewhere deep in the third tunnel, we turn back.

Back between the second and first tunnels is a grassy opening, with overgrown footpaths leading off into the mountain slopes. We scramble upward, eager to be in nature again, then stand looking back at the tunnels with their endless outflow of tourists.

This is the spot, I think. This is where Lee’s parents might have escaped. I imagine those little figures below as railroad workers, busy, heads down, not looking to the hills. It would be the easiest thing for Lee’s parents to turn their backs and keep walking, higher into the hills.

Alas, this was not to be. A terrible tragedy befell Lee’s parents before they could make their escape, a tragedy that shaped Lee’s upbringing and his life.

But Hannah and I are here, now. We could make their escape for them, a symbolic gesture, a re-enactment of a past that Lee’s parents only dreamed of.

— We continue up the dirt path, leaving the tunnels behind. It carves through thick, bright foliage. I imagine us as Lee’s parents, terrified, excited, hopeful, out in the fresh mountain air with the sunlight pouring over us. Only a little further to alpine meadows, to freedom.

We continue up the dirt path, leaving the tunnels behind. It carves through thick, bright foliage. I imagine us as Lee’s parents, terrified, excited, hopeful, out in the fresh mountain air with the sunlight pouring over us. Only a little further to alpine meadows, to freedom.

When our forest path ends in deep, sucking mud, we double back and ascend a different path up over the tunnel. It descends again on the far side of the mud. There is no trail here, just easy walking amidst rockfall and grass. Little flowers carpet the terrain. I can picture Lee’s mother here, plucking a few flowers, tucking them away for her baby.

I want to do something for them, something to commemorate the arrival they never had. Erect a small cairn, maybe, or carve their initials into a stone. But I don’t know their names, and even though this little pilgrimage is weighty and serious, I feel a little silly. I settle for pausing, soaking in the sights and sounds, and holding Lee’s parents in my memory.

—I have a new appreciation for the “ghosts of Gold Mountain” who carved a path through these mountain heights. I’m only a short way into Chang’s book, but finishing it will be my next commitment, my way of honoring the real laborers who made these tunnels.

Our pilgrimage ends back at the dirt lot where our dusty van awaits. We leave memory and imagination behind and return to the modern world, conceived by entrepreneurial visionaries with their dams and railways and interstates, and built by laborers like Lee’s parents. We start up the van and descend on a pleasant high back to Truckee, repeating the benefits of their work.

July 5, 2024

Day 16: Desolation Wilderness

One of my greatest regrets is that I didn’t take fuller advantage of the outdoors while living in California. To be fair, I was under tremendous pressure during these years, competing my PhD and working a demanding government innovation job while raising three young kids. We did the best we could with the outdoors, which was still respectable: frequent trips to northern California’s many beaches, a few ski trips to Tahoe, day hikes, summer vacations at alpine lakes, and a couple backpacking trips. Yet I craved more: more wilderness, more nights under the stars, more epic adventures.

When the COVID-19 pandemic hit, and California began enforcing strict lockdowns, I suggested spending long stretches of time in the mountains, Captain Fantastic-style. While most Californians were huddled at home, the national parks and forests would be practically empty. We could homeschool our kids, teach them wilderness survival and first aid skills, and explore some of the world’s most beautiful places, all while complying with social distancing legislation. My target for this mountain fantasy was Desolation Wilderness, southwest of Lake Tahoe, a place I had only heard of. The name alone was enough to evoke wonder.

My family quite didn’t share my enthusiasm, and rapidly-evolving government policy left us unsure whether this would even be legal. I let the fantasy go.

—When we live in a place, we take it for granted. This seems to be a universal element of the human condition. We travel the world to see a destination’s most famous sights, but many of us sheepishly confess that we’ve never visited the sights in our own backyards.

Moving to Alabama from California felt like exile. I made a nice life for myself, but I yearned for West Coast beauty. I appreciated the Southern mountains for what they were, but I knew the truth: they were only hills. I pined for the mountains and escaped when I could, on brief trips to the Sierra, the Tetons, and Red Rock National Park. I also sought the wilderness in books.

This trip has finally given me the opportunity to return to California, this time as a visitor. I resolved to not take the mountains for granted. I would have abundant time to revel in the beauty and truly learn each destination we visited.

I prepared for the trip with books. First and foremost was Kim Stanley Robinson’s High Sierra: A Love Story. I’d first discovered Robinson while a cadet at the U.S. Air Force Academy. I attended a conference about sending a manned spacecraft to Mars, where he was a keynote speaker. He won me over immediately: a sophisticated science fiction author, deeply intellectual, clearly brilliant, lean and handsome, and reportedly a mountain climber. I bought and read Red Mars, his most famous book, and then all the rest of his novels. He was unlike any other science fiction author I’d read. His work showed a deep love of nature. Unlike many SF authors, he seemed enchanted with this world, and he took that love into his science fiction settings.

High Sierra is a significant departure from his science fiction. It defies genre, combining personal memoir with mini lessons in geology, essays on the naming of wilderness features, sketches of key figures in Sierra history, and wilderness travel tips. Robinson writes that his own love affair with the Sierra began in the Desolation Wilderness in the 1970s, which only doubled down on my determination to visit. Hannah, who loved the book as much as I did, agreed we needed to go.

—We planned to visit Desolation Wilderness earlier in our trip, but it became a casualty of our finite schedule. Now that we’re back in Truckee, we thankfully have another opportunity. Mallory, an old friend of Hannah’s we want to spend time with, suggests a hike.

The hike runs roughly six miles, from Echo Lake to Lake Aloha, and then six miles back again. It begins in an overflowing parking lot, where we are exceptionally lucky to nab a spot from a departing vehicle; later, when we return, we find citations on the windshields of dozens of vehicles crammed along the roads. From the parking lot, a road leads down to a bustling store and boat launch. Friendly trail volunteers issue us a permit, then we set off along the shore of the lake.

The hike runs roughly six miles, from Echo Lake to Lake Aloha, and then six miles back again. It begins in an overflowing parking lot, where we are exceptionally lucky to nab a spot from a departing vehicle; later, when we return, we find citations on the windshields of dozens of vehicles crammed along the roads. From the parking lot, a road leads down to a bustling store and boat launch. Friendly trail volunteers issue us a permit, then we set off along the shore of the lake.

We aren’t actually in Desolation Wilderness yet; this hike begins in civilization and climbs its way out. The lake is teeming with recreational boaters. The trail passes dozens of small lakefront cabins, accessibly only by boat or trail. Vacationing families sit on patios, listening to loud music, talking. The trail is packed, a wilderness highway. It’s the kind of hike that I suspect Kim Stanley Robinson would avoid.

Still, the scenery is beautiful, and I don’t mind crowded trails. Seeing people outdoors makes me happy. When we pause to filter water, a delightful woman from a huge Korean group shares her childhood memories of drinking unfiltered water from sparkling creeks. We pass a boy scout troop, backpackers lugging heavy packs, and a group toting snowboards and skis in search of shady slopes still packed with snow.

Past the lake, we start a steep climb to a ridge. At last we reach the top and then the wilderness on the other side. The beauty keeps unfurling. The trail flattens and winds through alpine meadows. Snowmelt is pooled in dozens of unnamed ponds.

Past the lake, we start a steep climb to a ridge. At last we reach the top and then the wilderness on the other side. The beauty keeps unfurling. The trail flattens and winds through alpine meadows. Snowmelt is pooled in dozens of unnamed ponds.

Then, suddenly, we get our first glimpse of Lake Aloha. I had no expectations for this hike, but the vista is literally stunning. I stop to take it in: a black-and-white painting, white snow on bright granite, the broken white trunks of pines. This grayscale landscape makes the crystalline blue lake all the more brilliant, like a partially colorized photo.

The lake houses a backcountry campground. Brightly colored tents are wedged into every open space among the trees. Camp stoves and pots sit on tables improvised from chopped logs. Bear canisters lay about. Hikers and backpackers are sunning themselves on the rocks or swimming in the glacial water.

The lake houses a backcountry campground. Brightly colored tents are wedged into every open space among the trees. Camp stoves and pots sit on tables improvised from chopped logs. Bear canisters lay about. Hikers and backpackers are sunning themselves on the rocks or swimming in the glacial water.

We dump our daypacks on a rock, eat lunch, and drink warm beer. The sun, breeze, and alcohol make me sleepy. I nap while the women talk. Mallory takes a plunge in the lake. It’s tempting, but I’m feeling happily lazy. Eventually we rouse ourselves, gather our belongings, and start the hike back.

—Literature and nature, my two great loves. It feels wonderful to combine them on this trip. Books bring places to life, and I love visiting places special to authors. Hannah and I often make references to “Stan”, as though Kim Stanley Robinson is our personal guide, who has somehow wandered off and left us. Every time one of us wonders about some unique geological feature, the other says, “We need Stan.” Little references to the book pepper our conversations.

As we descend, our journey into wilderness reverses itself: back to the crowds, to the lakeside rentals, to speedboats and stand up paddlers. At the lakeside store we buy popsicles, then make the long drive back to Truckee.

It was a reasonably long hike, but it offered little more than a glimpse of Desolation Wilderness. We would need days or weeks to properly experience this place. Maybe a lifetime. And if Kim Stanley Robinson is right, this isn’t even the prettiest place in the Sierra. But at least we were here, seeing it for ourselves, sampling the riches it offers. I remind myself that this doesn’t need to be my last trip. I am taking notes about where I want to return, hopefully with my kids.

Day after day, this trip reminds me: take nothing for granted. Experience everything. There is so much life to be had.

July 3, 2024

Day 15: Confidence, Endings, and Beginnings

Over the past two weeks, Hannah and I have made five climbing excursions to School Rock at Donner Summit. Each time, we push ourselves a little harder. We like this crag because its six major routes span the lower range of difficulty levels, allow a new multi-pitch trad climber to work their way up a nice ladder of progression. We started with a 5.3, then a couple 5.6s. Today we plan to climb Mary’s Crack, a three-pitch climb that starts with a 5.7 crack, then an easy 5.3 slab, and finally a 5.8+ crack with a reportedly difficult crux move.

I feel ready for this climb, but I still feel intimidated. I have very little experience with crack climbing, which requires different skills from face climbing, so even a 5.7 or 5.8 crack will be at the edge of my abilities. My left shoulder is still weak from a partly-failed surgery, so I don’t know when or where my body might let me down. The crux move is near the top; if we can’t make the move, we’ll need to find a creative way off the face.

My greatest fear in climbing is getting stuck. I worry about reaching a point, muscles straining, struggling to hold on, where I can no longer safely go up or down. This isn’t as much of a concern when single-pitch sport climbing, because fixed bolts offer regular protection and can facilitate a quick and easy bail off the route. Multi-pitch trad is different. Although it shouldn’t be a problem on these specific routes, it’s possible to encounter long runout sections without cracks for placing protection. These routes also don’t typically have fixed anchors for rappelling off a route, so bailing can be tricky. Each time I climb a multi-pitch trad route, I feel like I must commit to the unknown.

All of this is familiar; I have written about this dynamic before. But today’s climb feels different. I have rapidly gained experience over these past two weeks, and I know this climb is within my abilities. The cracks might be challenging but offer abundant placements for protective cams.

Mary’s Crack makes a straightforward demand: that I show confidence in my abilities. It mirrors a much larger calling in this transitional season of life.

—The past two years have been a time of transitions—not mere moves or job changes, but seismic upheavals in the foundations of my life. Repeatedly, life has presented forks in the road: do I stay or go? My wife and I faced the question every single day, teetering between divorce and reconciliation. Military retirement presented another dilemma. Once I crossed the 20-year mark, I had the power to retire virtually any time I wanted. Staying became a choice I had to renew each day. I exasperated my bosses by submitting retirement papers, pulling them back, and staying for another year.

All of us find ourselves at such crossroads multiple times during our lives. We face anguished choices between the familiar and the unknown. Most likely we feel restless discontent with the status quo, which is why we contemplate a new beginning at all. Yet we also recognize the good we’d be leaving behind, and we are mindful of the dangers and uncertainties that lie ahead.

A common response in these situations is to hedge. We try to have it both ways, clinging to safe and familiar shores even as we test the waters of this unknown sea.

Sometimes this approach makes sense. Our fantasized new life, which we are so hopeful will deliver greater happiness, is only a hypothesis. It often makes sense to test this hypothesis by making small bets, an approach Bill Burnett and Dave Evans advocate in Designing Your Life.

Other times, hedging simply reflects decision paralysis. We cling to our purgatory, trapped between past and future, afraid to let go of either. The fear of regret haunts us. We might also lack confidence in our ability to chart a new course through life.

During this season, I read two things that finally helped me step into a new future.

First, I read that an overwhelming majority of people who finally commit to a major life decision believe that the decision made their lives better. I can’t find the source now, but it may have been an extrapolation from studies showing that most people’s regrets are about inaction rather than action (54% vs. 12% in one study; in several later studies, around 70% of respondents regretted inaction; see Gilovich and Medvec (1995).

Second, I read William Bridges’ classic book Transitions. Bridges argues that “transitions” are different from mere “changes”; changes are situational, while transitions are psychological; furthermore, changes often result from the pursuit of goals, while transitions start with letting go of something in one’s life that no longer works. From there, Bridges develops a three-part model of transitions: an ending, a “neutral zone”, and a new beginning.

The Bridges model is simple, but it shook me deeply. He showed me that I needed to decisively commit to an ending before I could reap the benefits of a new beginning. Once I took that step, things fell into place quickly.

—I think about this now, facing Mary’s Crack. It’s a different context, to be sure. No major life transition is involved in making this climb, but it feels like a metaphor for much bigger stirrings in my life.

A life transition calls for courage; it asks us to trust ourselves, our abilities, and the goodness of the world around us. When we burn the boats behind us—or leave the ground on a climb—we need confidence that we can overcome whatever obstacles lie ahead. We can never count on a problem-free future. Our fairy tales teach us that any hero embarking on an adventure will face perilous dragons, but they also teach us that this unlikely hero can rise to the occasion and triumph.

This is the truth I’ve tried to avoid for so long: in life, in my writing, and in my climbing. I want control. Through endless study, skill-building, and practice in safe environments, I want to eliminate every source of uncertainty before I embark. I want to guarantee success before I leave the ground, submit my retirement request, or publish a blog post. It’s a fool’s errand, time-wasting, draining away potential.

This trip is challenging me to approach life differently: to try things, to write with abandon, to climb routes with uncertain outcomes. Life is asking me to trust that I can handle what comes.

—I feel the usual fear prior to beginning the climb. As always, I’m silent on the drive. When we reach the wall and rope up, I start up immediately, before my nerves can stop me. It’s the same way I approach leaping off rocks into swimming holes with my kids: a single, fluid movement to the edge and out into the air. Nothing good comes from hesitating.

I hit the first tricky move just a few feet off the ground. Fortunately the cam placements are good, protecting me. After testing various handholds and footholds, I commit to the move. I stick it on the first try. Hannah and two nearby climbers cheer me on.

I quickly climb the rest of the pitch. The second pitch is unremarkable. We eventually arrive beneath an imposing roof, spit by an off-width crack, too small to fit my body but too large to jam hands. This is the crux, the hard move I’m not sure we can make. Even if I complete the move, I’m not sure Hannah can, which would leave her stuck beneath me. I breathe through the anxiety and consider options. From her belay station, we can traverse sideways to another, easier route. If we really get stuck, that will provide a viable escape; it will just require some downclimbing and take time.

I climb up to the off-width crack, place my first cam, and wedge part of my body up into the crack. I spend a long time studying the rock’s features, identifying opportunities for good cam placements. I try twice to pull the hard move, but I struggle. I’d really like another cam, but the piece I need is with Hannah. I lower myself out of the crack, build a new anchor, and belay Hannah up to me. I return to the crack, place a black Totem, and try the move again.

I heave and struggle and groan and curse. I know I’m capable of this move, but I can’t do it. If I recall what I read earlier, the usual way to pull the move is to jam a left fist overhead in the top of the crack. But that’s my bad shoulder, and as I try to contort my arm upward, my shoulder seizes up; it refuses to move at that angle. I feel twinges of pain. Even if I can place my fist, I’d hate to take a fall, sinking my whole body weight onto that shoulder. I try other approaches.

After twenty or thirty minutes of effort, I decide to call it a day. I grab the strap on a cam and pull myself upward. It’s cheating, pulling on gear instead of the rock itself, but it gets me through the move. A reasonable way of adapting and ensuring we can complete the route.

I build an anchor above the crux. Hannah follows. She tries just as hard to make the move. I can see her down beneath my feet, squirming and cursing. At one point she falls and slams her shoulder hard into the rock. She shakes it off. Eventually she repeats my move, pulling on a cam, and hoists herself up onto the next ledge.

—When we reach the top, we don’t feel our usual exuberance; we’re simply tired. However, we do have the deeper satisfaction of knowing we reached the top. This might be one of my biggest confidence-improving climbs yet, because it showed me I can safely handle a climb even when I can’t make all the moves.

It’s not altogether different from my writing. I’m still writing at a wild pace, publishing daily, and trying not to worry about readership. That’s admittedly hard to do. My readership is small, not growing. Each social media share attracts only a few likes, probably because of the ways the algorithms work; I suspect very few of my friends even see my posts. I also know I’m violating all the rules, writing so frequently and at such length, without a clear value proposition to attract readers. However, I’m doing exactly what I promised myself: writing for myself, battling my inner critic, proving to myself that I can put my work out into the world.

It’s a way of leaving the ground, or sailing away from safe shores. The safety I’m leaving behind—the thing I’m decisively ending—is staying hidden, where I won’t face criticism or rejection. I’m up among the bright granite now, searching out holds, trying things, seeing what happens, open to danger and trusting I can handle what comes.

Messages of affirmation trickle in. A high school classmate tells me she is living vicariously through my posts. A Navy friend who has been navigating his own decision about military retirement tells me how meaningful my posts are. An old Air Force colleague, out of the blue, writes an encouraging multi-paragraph message about his deepest lessons learned while processing divorce and his post-military transition.

Magic is happening, the first hint of a new beginning.

July 2, 2024

Day 14: The Art of Arrival

On day 12, I wrote about the infinite variety of a single place. On Day 13, I wrote about how writing enables an author to hone his senses, see more, more fully inhabit the present moment and the remembered past. For me, the virtuosos of mindful living are writers who embed themselves in particular places. Writing becomes a way of life, a means of crystallizing experience into something hard and pure, enabling them to develop a greater intimacy with human experience than most people think possible.

This is what I want my writing to be. My desire to write springs not just from a love of the written word, but of a ravenous love for life itself.

Over the past two decades I have exhausted myself on politics, nations, war, religion, movements, causes, grievances, the things that most of us take for granted as the stuff of life, partly because news and social media waterboards us with it 24/7; we have forgotten a world in which we’re not choking and sputtering for breath between forced, gurgling intakes.

But the closer I move to local, immediate experience—the cold sunlight spilling into our meadow, the feel of pen on paper, a rich conversation over dinner with a friend, an engrossing book—the more intoxicating and enchanting life becomes. For these three weeks I have intentionally dialed my world down to raw, immediate experience, and the result is rapturous. Repeatedly each day, I feel like I’m in a mystical reverie. Every single thing becomes a world unto itself: wildflowers on a hike, a wandering crack in the granite, an insight from a book. I could fall into the infinite offerings of each moment. I want to pull every thread, follow every footpath. This awesome feeling is bittersweet: the world’s offerings are infinite, and there aren’t enough lifetimes to experience them all.

In the early days of the Internet, prior to its enshittification into ad-congested doomscrolling, digital pioneers “surfed” hyperlinks through a web of unique, lovingly hand-crafted pages. The world itself feels that way to me now, an intricate living web, so much larger and higher-dimensional than the flat pixelated world I so often inhabit. I keep finding connections between places, people, history, ideas, books; I want more; I want it all. I’m starving to learn, to absorb, to more fully live.

Today I wholly give myself over to that impulse. We’ve been pushing hard the past few days, and now it’s time for a day of empty, unstructured time. I want to indulge my appetite to truly learn a place. Now that we’re back in Truckee, I want to truly arrive.

—A couple years ago, while on a backpacking trip in the southern Sierra, my colleagues at Cairn Leadership changed how I thought about “arrival.” Until that moment, arrival was nothing more than a checkpoint or milestone at the end of a journey. Arrival held no intrinsic significance, except as a marker of something else ending.

But the guides at Cairn were deeply thoughtful about every step of their outdoor adventures, which they use to train business leaders and teams. We met at a coffee shop in town, ran through some preliminary introductions and intention-setting exercises, and then loaded up our vehicles for the trailhead. We spent a solid hour in the parking lot, handing out gear, dividing up food, doing last-minute inventories, and packing our backpacks. Technically we had “arrived”, but by the time we wiggled into our packs and started up the trail, we’d hardly had time to notice.

A short ways into a strenuous uphill hike, our guides unexpectedly told us to stop. It was time to arrive.