Sir Poley's Blog

February 24, 2021

On Creating a Frictionless Traveller, Part II: Character Sheets

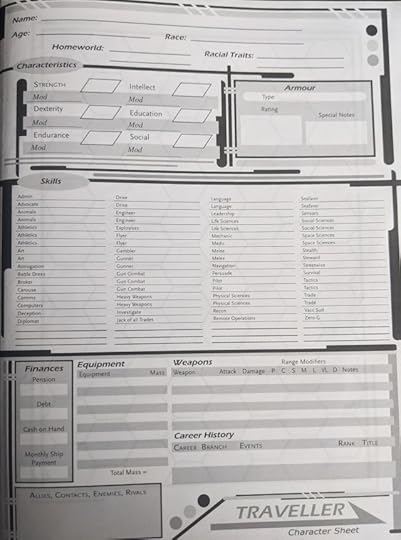

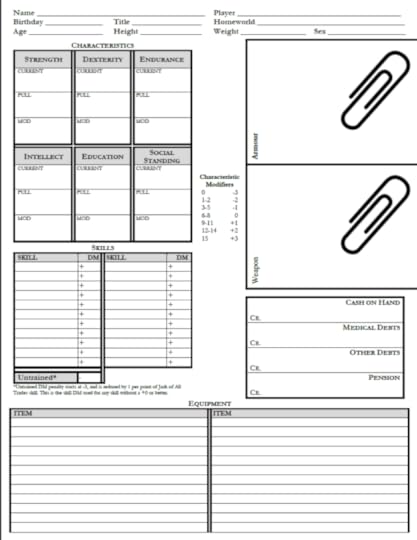

The character sheet that comes stock with the edition of Traveller I own (Mongoose Traveller1st edition, 2008) leaves a lot to be desired, although that almost doesn’t matter: I don’t own a scanner and can’t find it online, so I needed to make my own anyway.

With no scan available, here’s a grainy photo so you know what I’m talking about:

Here’s a few issues with the built-in sheet:

1. Traveller doesn’t use hit points. Instead (like Numenera, and other RPGs), damage reduces ability scores directly. The built-in character sheet doesn’t have a good way to differentiate current ability scores vs. maximum ability scores.

2. Similar to D&D, ability scores grant a die modifier to skill checks. When ability scores change, so does the modifier. Unlike D&D, ability scores in Traveller can change every round. The algorithm for calculating the modifier isn’t immediately obvious, so this has to be looked up every time someone takes damage.

3. Weapons and armour tend to change more often in Traveller campaigns than in D&D campaigns because many weapons are illegal on many worlds (see Post I). However, each weapon (particularly ranged ones) come with quite a lot of information associated with them, as in addition to any special rules they might have (and many do), they have damage, heft/recoil, ammo, rate of fire, and range modifiers at various distances. Armour isn’t as complex, but is still annoying to change frequently.

4. As a sci-fi game, a lot of gameplay comes from neat gadgets PCs can purchase. However, space for equipment on the main character sheet is tiny.

5. Character creation involves going through several four-year terms. This generates a ton of information, but the default character sheet relegates this to a tiny corner.

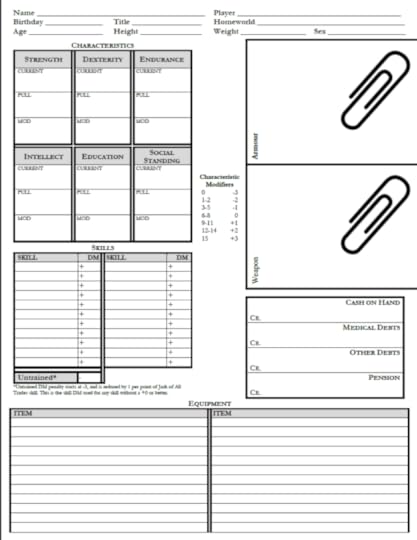

My homebrew character sheet uses the following solutions to these problems (don’t print these screenshots, PDFs will be available below):

1. Each ability score now has much more space, and separate boxes for the modifier, the current number, and the maximum number.

2. To solve problem #2, the table that converts ability scores to modifiers is printed directly on the sheet.

3. Instead of making players copy down the many, many numbers associated with each weapon, I made playing-card sized cards for each weapon in the book and have space on the character sheet to paper clip them in. When weapons change, it’s as easy as swapping a card. Armour gets an extra mini-card for ablative or reflective overlays.

4. There’s much more room for equipment on my character sheet, made up for by shrinking the Skills section. Traveller characters tend to only have a few skills, so they can write in the ones they have, rather than listing all available ones.

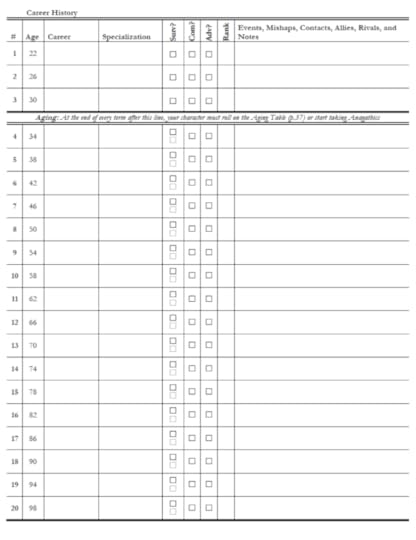

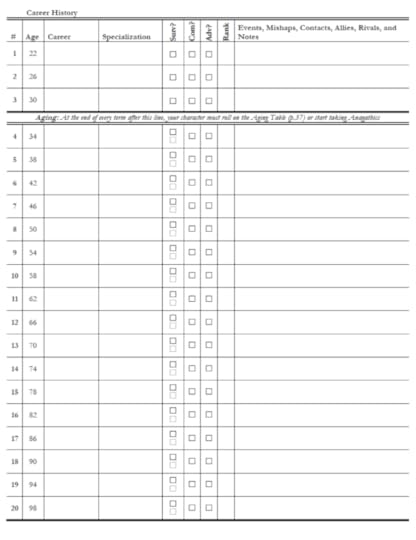

5. The entire back page is for character creation information.

A few things that came up since creating these character sheets that I ought to fix for a later one:

· The blank section for “Weapons” should probably have “unarmed combat” stats on it.

· There’s no space for recording Rads a character has absorbed

I’m not an artist by any means. There’s no question that my character sheet could be prettier. But (for my purposes anyway), it’s much more functional than the one that comes with the book.

I’ll include download PDFs of the weapon and armour cards, and the new character sheet, below. Margins were determined based precisely on what my printer could print, so YMMV.

On Creating a Frictionless Traveller, Part II: Character SheetsThe character sheet that comes...

The character sheet that comes stock with the edition of Traveller I own (Mongoose Traveller1st edition, 2008) leaves a lot to be desired, although that almost doesn’t matter: I don’t own a scanner and can’t find it online, so I needed to make my own anyway.

With no scan available, here’s a grainy photo so you know what I’m talking about:

Here’s a few issues with the built-in sheet:

1. Traveller doesn’t use hit points. Instead (like Numenera, and other RPGs), damage reduces ability scores directly. The built-in character sheet doesn’t have a good way to differentiate current ability scores vs. maximum ability scores.

2. Similar to D&D, ability scores grant a die modifier to skill checks. When ability scores change, so does the modifier. Unlike D&D, ability scores in Traveller can change every round. The algorithm for calculating the modifier isn’t immediately obvious, so this has to be looked up every time someone takes damage.

3. Weapons and armour tend to change more often in Traveller campaigns than in D&D campaigns because many weapons are illegal on many worlds (see Post I). However, each weapon (particularly ranged ones) come with quite a lot of information associated with them, as in addition to any special rules they might have (and many do), they have damage, heft/recoil, ammo, rate of fire, and range modifiers at various distances. Armour isn’t as complex, but is still annoying to change frequently.

4. As a sci-fi game, a lot of gameplay comes from neat gadgets PCs can purchase. However, space for equipment on the main character sheet is tiny.

5. Character creation involves going through several four-year terms. This generates a ton of information, but the default character sheet relegates this to a tiny corner.

My homebrew character sheet uses the following solutions to these problems (don’t print these screenshots, PDFs will be available below):

1. Each ability score now has much more space, and separate boxes for the modifier, the current number, and the maximum number.

2. To solve problem #2, the table that converts ability scores to modifiers is printed directly on the sheet.

3. Instead of making players copy down the many, many numbers associated with each weapon, I made playing-card sized cards for each weapon in the book and have space on the character sheet to paper clip them in. When weapons change, it’s as easy as swapping a card. Armour gets an extra mini-card for ablative or reflective overlays.

4. There’s much more room for equipment on my character sheet, made up for by shrinking the Skills section. Traveller characters tend to only have a few skills, so they can write in the ones they have, rather than listing all available ones.

5. The entire back page is for character creation information.

A few things that came up since creating these character sheets that I ought to fix for a later one:

· The blank section for “Weapons” should probably have “unarmed combat” stats on it.

· There’s no space for recording Rads a character has absorbed

I’m not an artist by any means. There’s no question that my character sheet could be prettier. But (for my purposes anyway), it’s much more functional than the one that comes with the book.

I’ll include download PDFs of the weapon and armour cards, and the new character sheet, below. Margins were determined based precisely on what my printer could print, so YMMV.

February 19, 2021

On Creating a Frictionless Traveller, Addendum: the Law and Melee Combat

When makingthe table in Part I, I realized that every planet has a semi-hiddencharacteristic that balances melee combat. This was pretty astonishing to me,as it’s buried pretty deep, but it’s also a huge improvement to the game ifimplemented in your campaign.

The issueis as follows: Traveller ranged andmelee combat is realistically balanced (whichis to say, swords simply don’t compare to laser guns). Traveller also lacks “sci-fi remedies” such as lightning swords and laser whips and whatnot:with the exception of the stunstick, melee weapons are pretty conventionalrenaissance or medieval era swords and so on. None of this is exactly a problem, but it’s a little weird that,during character creation, there’s quite a lot of emphasis on getting fancyswords and the Melee skill, especially Melee (Blade). A lot of career optionsdangle Melee (Blade) in front of players in a way that means it seems like it ought to be useful, but, on its face, isn’t.

There’s alittle note in the rules that cutlasses and so on are popular boarding weaponsbecause it reduces the chances that a stray shot will damage a ship’scomponent, but there’s not really any clear rule or system for how that wouldplay out beyond occasional GM fiat. In practice, I’m pretty sure that if theparty tried to rush a pirate ship through the airlock with cutlasses, and thepirates were willing to scuff their own ship and thus had shotguns, the resultswould be fairly predictable.

(At some point I might create a houserule to handle that (missed ranged attacks roll on a table of spaceship damage or something)).

It’s fine to say “in this sciencefiction setting, combat is done with guns. Bringing a sword to a gunfight isanachronistic and suicidal.” Most science fiction, Star Wars aside, takes this approach. But if that’s the approach Traveller was going for, then… why are there all these rules for melee combat? Traveller, unlike,say, D20: Modern, isn’t a spinoff ofa fantasy game with a bunch of vestigial fantasy-genre-stuff. These rules were put in for a reason.

A relatedissue (again, not exactly a problem)is that laser weapons are vastly moreeffective than conventional firearms (unless the enemy has Reflec, though text in the book (and equipment of default NPCs) indicates that this is supposed to be a fairly rare item). Laser weapons are also more expensive, but theprice of both are trivial compared to the amount of money Players will bedealing with in the trade system. So… why are there all these rules forconventional firearms?

The answer:because guns are illegal, laser guns,doubly so. On a shockingly large number of planets, anyway. Shocking tosomeone from a D&D background, anyway, where the expectation is that if aweapon is written on a character sheet, it’s pretty much always available.

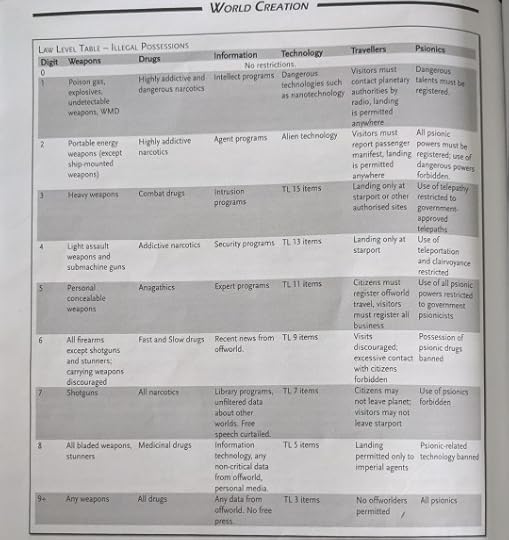

Law Level Table, Mongoose Traveller (2008) p.176

Each planethas a Government code, and a separate Law Level Table tells you which items are banned bywhich type of government. Most governmentsrestrict weapons. The two most important for our purposes are“Weapons” and “Techology” (because a lot of powerfulweapons are only available at advanced TL’s, also). I went through each weapon in the book and pennedin the “Law Level” it becomes illegal at (this should have been in the book to begin with). The result isthat nearly every planetary governmentrestricts laser weaponry (Law level 2+ by Weapon, 3-7 by Technology,depending on the weapon in question). Some,but not all, restrict conventional firearms (Law Level 4-7+, depending on theweapon, and by around 5+, by Technology), but virtually none restrict meleeweaponry, whether by restricting Weaponry or Technology. I had to make a prettyarbitrary few judgement calls (I decided any weapon with autofire, plus theextra-deadly gauss weapons, counted as “assault weapons,” forexample). Now, when the party goes to a planet’s surface, I tell them therestrictions that planet places on weapons and technology (”Weapons Law 2+, TL13+,” for example), which they compareto the number printed on their weapon cards (see the upcoming Post II), and then they tellme if they’re complying with the law or smuggling their weapons in. I havethese numbers written in my notes on each planet in my GM binder.

The resultof this is that there are huge stretches of the galaxy where sword-and-boardfighting is prevalent (ruthlessly enforced by police who are equipped with controlled weapons), while boarding actions,which are an anything goes “wild west,” are dominated by ultra-lethallaser weaponry. I know that this is the opposite dynamic to that noted by the text on boarding actionsand cutlasses, which is a discrepancy I haven’t yet been able to resolve. Nonetheless, it does leave a niche for both styles of fighting.

If you, asGM, are consistent with weapon and technology control laws (which means theheadache of dealing with the Law and Government tables at the back of the book),it opens up many new opportunities for PC’s with unconventional skills toshine. This is especially important given Traveller’s quirky character creation—playersdon’t always have a lot of control over their character’s skills, so anythingthat puts disparate skills on a more level playing field is worthwhile.

February 15, 2021

On Creating a Frictionless Traveller, Part I: Trade

I just ranSession Zero (character creation and so on) of Mongoose Traveller 1st edition (2008) with my quarantine pod.This is my second Traveller campaignthat I’ve run (thoughts inspired by the first you can read about here), and thefourth that I’ve been a part of. Having learned a little from my last campaign,I’ve made a few improvements to the game’s interface(not really houserules) that speed up gameplay and reduce friction.

What do Imean by interface? Imagine if Traveller was a computerprogram. The interface would be the information displayed on the screen, whilethe actual rules of the game are what goes on in the background. Traveller’s rules, so far, are rock-solid.The basic core dice mechanics are fast and easy, and the game’s many elegantsystems for procedural generation allow nearly endless gameplay with onlysparing need for GM-added “spice.”

What isn’t elegantis the way some of these systems are presented to the GM and the players. Thusfar, I have isolated several systems (many of which are quite entangled witheach other) that could benefit from a more polished interface to reducefriction during play (i.e., avoidable timeswhen the game grinds to a halt and something has to be looked up, calculated, found,remembered, etc.). They are:

Trade (namely: calculating purchase modifiers,number of passengers, amount of available freight, legality of various goods)Character Statistics (namely: character sheets, weaponand armour statistics)Spaceship combat (namely: tracking spaceshipposition, responsibilities of individual crewmembers, tracking computerprograms)I’ll startwith trade because it is, I think,one of the most overwhelming systems in the game on its face, but also one ofthe most crucial to keeping the Traveller“loop” going. It’s also part of what makes Traveller so unique.

To buycargo, a character must make a Broker skill check (easy), adding a modifierbased on the value of that trade good on the current planet (easy), and compareit to a little table that converts that into the price, as a percentage, of thegood’s value (easy, with a calculator or smartphone). For example: to buy BasicMachine Parts, a player must roll 3D6 + 2 (the PC’s Broker skill modifier) + 4(a bonus because the goods are cheap on the current planet). The roll is 17,which a table on page 164 tells you means Basic Machine Parts can be bought at65% of their value (normally cr. 1000/ton), or cr.650 per ton. Great. Easyenough, right?

Wrong.

The reasonthis can be incredibly slow isbecause the price modifier based on the planet’s characteristics—the number that encourages the players toexplore the galaxy—is a real headache to calculate on the fly. It is calculatedfrom the following sources:

First,look up the Trade Good on the table on page 165. Lookat the Trade Codes of the planet in question (on a handout the GM generates andgives to the players at the start of the campaign) Determineif the Trade Good is illegal on this planet. This is found by:Comparingthe planet’s Government Code (on the handout) to the Government Table (on page175) to see if a category of goods is restrictedIfit is, debating for awhile whether “Advanced Weapons” are considered“Heavy Weapons” or “Portable Energy Weapons” (i.e., make ajudgement call)Comparingthe Law Digit for the item from the Law Table on page 176 to the Law Level ofthe planet to see how illegal it isFindthe highest number in the Purchase DM category related to these Trade Codes,unless it is lower than the number calculated in step 3, in which case, use thenumber in step 3 (and the PCs are now smuggling! This is cool because now youcan have police chases and so on.)Findthe highest number in the Sale DM category related to these Trade Codes andsubtract thisSumall of these numbers. Repeat for each trade good purchased.Looking atall of those steps probably convinced at least some of you to swear off Traveller altogether. But here’s thething: this is incredibly slow to calculate duringplay, but after the galaxy is generated, these numbers never really change.Barring exceptional events in thecampaign, an Industrial world will continue to be Industrial from start tofinish. My toddler was unusually chill last week, so I spent a few hours makingan Excel spreadsheet that crunches this once, and only once, and spits out this table for my star cluster:

Eachfour-digit code along the top corresponds to a labelled hex coordinate on the starcluster map they have (i.e., a settled planet).

This tablepresents each planet’s numerical stats. There’s a lot more that goes into eachplanet (it’s weird cultural quirks, important NPCs there, maps, etc.—you know, worldbuilding stuff) but this table iswhat the players need for the game’s rules. Different types of survivalequipment available are rated for different atmosphere numbers, for instance,and different bases provide different services. I know “Gas Giants”aren’t really bases, but I didn’t have space for another column for them.

I’ll admitthis was a slog to put together. I like spreadsheets more than most, but evenmy eyes glazed over a few times doing this. I also had to make a few judgementcalls on what items were restricted at various law and government levels. It’salso possible it contains significant errors; my spreadsheet grew morecomplicated than I was able to understand (and thus debug) by the time it wasdone. Still, it works for now, and I’m not willing to change it. It wasn’t morework than, say, drawing a dungeon map, and it’ll last the whole campaign. Imade similar tables for determining passenger and freight availability. If I ever go back and tidy up that spreadsheet so that it’s useable for others, I’ll post it.

Nowthat that math is done, it stays done. I gave the players this,printed on cardstock, at the start of the campaign, and they never need to know how much work I savedthem.

Buying and selling stuff now isn’t any more work than any other skillcheck: it’s a dice roll, plus a modifier on the character sheet, plus acircumstance modifier. It’s quick, it’s easy, it's frictionless.

July 22, 2020

On the Full Plate Threshold and the Nature of Money

“Can I buy a magic sword?”

This is a question that seems straightforward,

but is actually fraught with follow-on implications that are not obvious. It is

also one that’s asked at some point in any D&D campaign. You might be

thinking, as GM, that you’re making a choice about the setting of your campaign (is this a high-magic or low-magic world,

a desert island, a major trade city, etc). While you are making this decision, you’re also deciding (perhaps without

knowing) what money is in this game. You’re

deciding whether your adventuring party will build castles or not, whether

they’ll hire armies or not, whether they’ll go adventuring or not, whether

they’ll be greedy or not, and whether they’ll care about rewards at all after

the fighter gets her hands on a set of Full Plate.

In my experience, money in RPGs is used for

one of six things: character power, narrative power, oxygen, skill, XP, or

nothing.

This paradigm is the one most familiar to

3.x veterans such as myself, and is the direct result of allowing magic items

to be purchased freely for money. This allows players to invest money in their

character’s powers and strengths in the same way they do with skills and feats.

There is a slightly different set of constraints on how money is spent than

skill points (which is to say, the party must find a city), and may be further

restrictions still (such as 3.x’s limitations on the most expensive items that

can be bought in each size of settlement), but at the end of the day, players

can pretty much buy whatever they have money for.

In essence, if a player can convert

currency into better stats, damage, armour, etc., then in your system, money is

character power and should be treated as such. The GM should keep a close eye

on how they hand out treasure and quest rewards, as too little or too much

money can easily result in difficulty balancing encounters. Third edition

D&D came with a table stipulating how much money each character should have

at each level (the (in)famous “Wealth by Level” table) and balanced

monster CR based off of this assumption. In my younger years, I GM’d several

campaigns in which I restricted purchase of magic items because of campaign setting

reasons (it was a low magic setting, or the party was far from civilization, or

whatever), and then was shocked as the party struggled against ethereal

monsters or monsters with damage reduction, yet with CR far below their level.

Additionally, such restrictions won’t affect all characters equally—a 3.5-era

sorcerer, for instance, can operate just fine despite absolute poverty, while a

fighter will really feel the lack of a level-appropriate magic sword. Monks,

despite not using weapons or armour, are ironically among the classes most dependent on magic items because of

their dependency on multiple ability scores.

Determining whether your system assumes

money as character power may not be immediately obvious, but as a GM, it is

crucial that you find out. D&D’s modern-era spinoff, D20 Modern, does not

use money as character power, as you can’t simply buy better and better guns as

you level up—once you’ve realized that the FN 5-7 pistol and the HK G11 rifle

are mathematically the best guns and you’ve bought them (which you can easily

do as a first-level character), you’re set for the rest of the campaign.

However, D20 Modern variant campaign settings, such as D20 Future and Urban

Arcana, do allow you to directly

convert money into character power, as the reintroduction of D&D-esque

magic items of Urban Arcana and the “build your own gear”

gadget-system of D20 Future allow unlimited wealth to be converted to unlimited

power.

What

to Watch as a GM: Ensure a steady trickle of

monetary rewards that increase as the players level, realize that players will

be increasingly antsy to reach town the more treasure they have, keep an eye on

any game-provided wealth-by-level suggestions, and be wary about player-driven

“get rich quick” schemes and item crafting systems. Be very cautious

about allowing a PC to borrow money from an in-world bank or other lender, as

they could quickly invest that money in magic items and destabilize the game

balance.

Advantages:

Combing through books to find perfect magic/sci-fi

items is very appealing to some players, and it allows the GM to dangle money

in front of his or her players to hook them on adventures.

Disadvantages:

Can lead to very hurt feelings (and huge game

imbalances) if a character is robbed/disarmed in–game, as it is functionally

equivalent to erasing a feat from their character sheet. Further, the game can

break down very quickly if there is a wealth disparity among the party, as

there are more than simple roleplaying repercussions to playing a

“rich” or “poor” character. Some players find this system

“video gamey,” and others feel that it overwhelmingly encourages

players to steal everything not nailed down.

Best

For: Combat-heavy games in which a

“build” is important, high magic/soft sci-fi settings.

When money sees its most use bribing

officials, hiring mercenary armies, building castles, or funding large-scale

operations of any kind, money in your system directly converts to

“narrative power.” Players can use cash to influence the game world

and the direction of the story, but not necessarily to deal more damage in

combat (or heal more, or buff more, or whatever). This is where D&D 5e tends

to get to after low levels (see “Crossing the Streams” for more on

this). Many gritty, film noir-esque stories rely on key characters being dangerously

in debt and are called to adventure by motivation to pay off said debt.

Depending on the details of the campaign world, however, Players might stop

caring about money entirely if it doesn’t directly relate to the plot or some

kind of scheme.

What

to Watch as a GM: If you come from a legacy of

“Money as Character Power” games, you might have to remind yourself

to loosen your grip if one or more characters seems to be accumulating

“too much” money. Just because money doesn’t have direct applications

in combat and adventuring doesn’t mean it isn’t an important game resource—be

sure to provide opportunities for players to use their money to solve problems,

or else they’ll quickly ignore it entirely.

Advantages:

Allows a host of narrative options restricted by

“Money as Character Power” games, such as managing businesses,

organizations, or fiefdoms. Allows a wealth disparity between party members

with only moderate issues. Additionally, allows stories involving borrowing and

lending money without breaking balance in half, and overall can feel quite

freeing.

Disadvantages:

Can still cause problems if one PC is notably

wealthier or poorer than the rest, depending on the players themselves, as they

might end up driving the story. Unless finances are baked into the plot, using

money as a reward is unlikely to garner much interest on behalf of the players.

Best

For: Gritty realism, power politics, games that

will eventually result in characters becoming lords/ladies/CEOs/etc.

In some ways, this is the exact opposite of

“Money as Character Power"—when money is treated in your system as a

skill, players have to sacrifice

combat power in exchange for wealth. For instance, in the Fate-based Dresden

Files RPG, if a player selects Resources to be one of their better skills, they

are consciously giving up choosing, say, Weapons or Fists as a good skill. In

such a system, a character’s wealth is abstracted, and largely unaffected by

major purchases or sales. Similarly, monetary quest rewards are pretty much off

the table unless similarly abstracted.

This system strongly encourages huge

disparities in wealth between party members, allowing rich and poor characters

to solve problems equally well, just in different ways.

Note that "Money as a Skill”

doesn’t just mean that purchases are handled by skill checks, but rather that

the wealth of a character is as core, internal, and untouchable as their other

core stats, like Strength, Agility, etc. D20 Modern uses a system similar to

skill checks to handle finances, but a character’s Wealth score fluctuates

hugely when they buy or sell things, so doesn’t entirely fit in this paradigm.

Sometimes these systems do away with money

altogether, such as the mecha rpg LANCER, which exists in a post-scarcity world

entirely without money. Equipment is earned by getting progressively better

“licenses,” which authorize PCs to replicate increasingly powerful

weapons and mecha shells.

What

to Watch as a GM: You’ll have to find ways to

motivate players without monetary rewards, and be sure to find opportunities to

reward players who invested in their “money” skill, either through

narrative or scenario design, just as you would ensure to place a few traps in

every dungeon for a rogue to disarm.

Advantages:

Allows (and, indeed, almost requires) large wealth

discrepancies between characters, and greatly reduces bookkeeping.

Disadvantages:

Tends to be highly abstract, which can lead to a

mismatch of expectations (such as if players start looting bodies to sell, with

absolutely no mechanical impact, or being unsure if “+5 wealth” is

middle-class or Bezos-class).

Best

For: Narrative games without much focus on

accumulating wealth and treasure, but in which money still matters.

This is the oldest of all old-school

approaches, and in many ways the logical extreme of “Money as Character

Power.” When money is used as XP, acquiring gold directly leads to

characters increasing in level. Sometimes this requires spending the money

(i.e., donations to charity, training, or spell research resulting in XP

gains), while other times, it only means acquiring the money (in which case,

you have to answer the question of what players are to do with all this

accumulated wealth after its primary purpose—giving them XP—has been achieved).

This approach has largely been left by the wayside, and many modern players

will discount it out of hand, but I’d encourage you to stop and think about it:

we already accept that fighting more powerful monsters and overcoming more difficult

challenges lead to greater XP and

greater material rewards, so why not cut out the middleman and just say the

material rewards are XP? One caveat

is that, even moreso than with “Money as Character Power,” this can

result in PCs doing anything to get

their hands on cold, hard cash—but, conversely, by removing (or downplaying)

combat XP, it can also result in encouraging peaceful or stealthy approaches to

solutions. This would lead into a whole conversation about when and how to give

out XP, and what behaviours this decision encourages around the tabletop, but

such a discussion is outside the scope of this essay.

This system works well for GMs that want

their players to be treasure-hungry, like in Money as Character Power, but

don’t like the inevitable proliferation of magic items that results.

As with “Money as Character

Power,” under such a paradigm, GM’s must keep a close eye on PC’s pocketbooks.

Taking away their treasure, either through in-game theft, a rust monster, or

similar, will lead to frustration and hard feelings. Similarly, anything that

lets players turn a profit without adventuring, such as item crafting or simply

by getting a day job, could destabilize the game unexpectedly—many systems specify

that only treasure found while

adventuring counts towards XP, though determining what counts as

“while adventuring” can be something of a headache (albeit not an

insurmountable one). Additionally, this system strongly discourages wealth

imbalances between PCs, as they directly

result in some PCs being higher level than others.

Given how out-of-style this is in tabletop

games, it’s perhaps surprising that several modern video game RPGs fall into this category in the late game. In Skyrim, for example, after I’d bought

the best weapons and armour that could be found in shops, future resources went

into buying all the world’s iron and leather to grind up my Smithing skill

again and again, giving myself easy levels.

What

to Watch for as GM: Same as with “Money as

Character Power.”

Advantages:

Eliminates post-battle XP calculation entirely,

encourages players to avoid direct confrontation, and gives players a very

strong monetary motivation (which can also be a disadvantage) without resulting

in a high-magic world.

Disadvantages:

Can strike some players as unintuitive, and strongly

encourages desperate treasure-hunting (which can also be an advantage).

Best

For: Games involving treasure-hunting and

exploration.

With Money as Oxygen, money becomes

something that players need a steady stream of just to survive. Maybe they’re

deeply in debt, have to make rent payments, have to maintain their equipment,

or just have to feed themselves. The reason for their regular thirst for wealth

might be narrative (rent, debt, etc.) or mechanical (equipment maintenance,

etc.) in nature. In Traveller, a

huge source of motivation for the party is just trying to keep ahead of mortgage

payments for your starship. Money becomes the same as food, water, and air—a

vital necessity that you simply always

need more of.

With Money as Oxygen, players constantly

have to eye their dwindling bank accounts and do cost-benefit calculations before

accepting a mission, or else disaster could strike. This is a very, very

different genre from “Money as Character Power” or even “Money

as Narrative Power,” as it rarely results in the party spending their money

on anything other than survival. Unless they really hit a gold mine, they won’t

use money to upgrade weapons or armour, or to buy land and power, because doing

so runs the risk of starvation/bankruptcy/etc.

This probably isn’t the paradigm to use for

most D&D-esque campaigns, as it can (and should) result in players actively

avoiding heroic archetypes—if survival depends on a paycheck; the crusade

against evil is someone else’s problem.

What

to Watch for as GM: This paradigm is

bookkeeping-heavy, so make sure the players understand that from the get-go.

Also, anyone expecting “Money as Character Power” might find

themselves frustrated by their ever-dwindling resources. Make sure you have a very good handle on the math of the

players’ survival (that is, exactly how

many gold pieces/dollars/credits they need to survive a week) or you might

accidentally underpay them and lead them to ruin. Not that this shouldn’t

happen; it just shouldn’t happen by

accident. If you accidentally give them too much money, feel free to

timeskip ahead several months until they’re broke again, or dangle another

moneysink in front of them, like a one-of-a-kind, now-or-never opportunity to

buy a shiny magic item or spaceship upgrade (dipping judiciously into Money as

Character Power).

Advantages:

Makes the players feel poor, desperate, and downtrodden.

Disadvantages: Both the players and the GM have to keep a very, very close eye on finances in order to

maintain tension. If paired with a mechanical system that doesn’t result in

substantial character progression from XP (such as skills, feats, etc.), then

players can feel stuck and lacking motivation.

Best

Used For: anything that can be accurately described

with the words “seedy underbelly.”

We’ve all played games in which money is

straight-up useless. In many Zelda games, for example, like the classic Ocarina of Time, monsters drop rupees

all through the game. In addition, there are secrets, hidden chests, and

puzzles that pay out rupee rewards as if

the game thinks they would make you happy. After the first hour of the

game, it becomes blindingly obvious that there’s no point to this money, as the

things you would buy (arrows, sticks, bombs) are just as freely dropped from

monsters and bushes. Many other video games hit this point after the early game

as well (like Diablo II, where

monsters continue to drop thousands and thousands of gold throughout the game,

but there’s nothing worthwhile to spend it on).

I personally can’t see any advantages to

this system, as I don’t think it’s chosen by design.

Of course, few games fall strictly into one

of the above categories, and most aim to do two or even three, which can lead

to some common pitfalls. For example, the 3e splatbook the Stronghold Builder’s

Guide allowed players to spend tens of thousands, even hundreds of

thousands, of GP on elaborate castles and mansions. These was very cool, and

the rulebook is one of my favourites from the edition… but I’ve never seen it

used in actual play, because any player who did so would find themselves

handicapped for the remainder of the campaign, as they hadn’t invested their

gold in magic items, as the system requires

you to. (Again: the math of monster design in 3.x assumes and requires that

player characters gain magic items at a set rate).

Some of the paradigms play nicer with each

other than others. For example, many variants of “Money as XP”

practically require a secondary output for money. Unless the XP is only gained

by spending the money, all of that accumulated loot has to go somewhere—typically either into magic

items (Money as Character Power) or into strongholds (Money as Narrative

Power). Games that have large-scale battle rules (which, I’ve been told, ACKS

does, though I haven’t played it firsthand) blur the lines between Narrative

and Player power, because the castles and hirelings a player buys actually do something, mechanically, though they

typically don’t help you in an actual dungeon. “Money as Oxygen,”

similarly, may require temporarily dipping into another paradigm to bleed off

surplus money from the party to keep them permanently poor (something Traveller does gracefully by allowing

incredibly-expensive spaceship upgrades).

The Full Plate Threshold:

once the players have

bought the most expensive item available to them, the nature of money

permanently changes.

One very common dynamic is for games to

have Money as Character Power in early levels, and transition to another

paradigm (or fall into Money for Nothing) at later levels. This is particularly

common in video game RPGs, where after the early game, nothing anyone sells in

stores is of any value whatsoever (or if they do, the price is trivial), yet

despite this, monsters continue to drop

thousands upon thousands of gold. If these games have a multiplayer

aspect, players usually settle on a rare item as the de facto “currency” for trades.

This is also the dynamic that results when

the sale of magic items in D&D-esque games is restricted, as in early

levels, players save up to buy half-plate to replace their breastplates,

warhorses to replace their feet, composite bows to replace their shortbows, and

so-on. Once the most expensive upgrade has been bought (in D&D, the last

character to make this transition is typically the fighter, as the best mundane

armour available is a steep 1,500 GP in 3.x and 5e—a friend of mine dubbed this

the “Full Plate Threshold” after my 5e paladin bought full plate, and we all suddenly stopped caring

about gold), money is no longer convertible to Character Power. At this point,

which can happen between level 3 and 7 depending on character class, system, and GM

generosity, the nature of money in the campaign will change. This could result in the widening of scope in the

campaign, as players invest in land, armies, and castles, or it could result in

money piling up like in Diablo or Final Fantasy, totally meaninglessly. Similarly,

many campaigns that start with “Money as Oxygen” can escalate into

“Money as Narrative Power” as players finally hit the jackpot, and no

longer need to worry about maintenance/mortgages/etc.

As a GM, handling this transition can be

tricky. If it sneaks up on you without realizing (many 5e D&D GMs might not

know (because they weren’t told), for instance, that the nature of money

changes dramatically the second

someone buys full plate), they might suddenly find their players disinterested

and bored around the table even though seemingly nothing else has changed. Their adventures are just as gripping, their monsters just as scary, their dungeons just as unique… but the players seem to be just going through the motions If your

system or campaign doesn’t have an endless supply of increasingly-expensive

bits and baubles for players to buy, you’re going to have to manage this

transition, whether you want it or not.

There is no objective “right” or

“wrong” way to handle money in an RPG, but some methods definitely

work better for certain genres than others, as changing the “rules”

of money in your campaign will massively change the feel and pace of the game.

On the same note, be careful of follow-on effects from changing the rules:

simply saying “magic items can’t be bought,” without making any other

changes, will lead 3.x campaigns into a series of very predictable roadblocks (weakening

martial characters, unevenly and unpredictably increasing encounter difficulty,

and potentially eliminating motivation to go on some adventures) that you have

to have solutions to. Similarly, adding a “magic item store” to a

system not initially designed for it, such as D20 Modern, can lead to massive

imbalance and weird behaviour. For instance, due to bizarre math, even

relatively powerful magic daggers fall below the threshold at which rich

characters lose wealth points in that system, making them literally free, while buying an unenchanted, off-the-shelf AK-47 (which

is just above that same threshold) permanently

drops the wealth bonus of any character. This leads to the system incentivizing

any problem that can be solved with

thousands of +3 Daggers being solved with thousands of +3 Daggers in a way that neither GMs nor

(I assume) game designers intended.

These incentives matter. If a game penalizes one option and incentivizes another,

that second option is just going to be taken more often. Maybe a lot more often. If you can align your

campaign’s incentives with desired behaviour for your players, you’ll save a

lot of headache, frustration, and counter-intuitive behaviour for everyone involved.

July 21, 2020

Parties vs. Guilds

(This is a gaming post, not a politics / economics post.)

So the last D&D game that I ran hit a scheduling conflict, then another, and then stalled to a halt. And in the meantime I started up a Pandemic Legacy game (which goes much faster when you play 3 games per session and one session per week :P ), backed a game that’s reminiscent of Darkest Dungeon (The Iron Oath, 39 hours left in their KickStarter at time of writing), and a friend got into Massive Chalice.

All of which have me thinking about the difference between RPG management / strategy games and tactics games. For example, Massive Chalice has the XCOM flavor where there’s a strategic layer and a tactical layer, which reinforce each other; Darkest Dungeon is similar while the strategic layer feels more lightweight. And in Pandemic Legacy, the strategic layer is basically the durable changes to the board/character/rules.

I notice that when I’m playing D&D, I miss that, and so I often try to bolt something like that on. When DMing, rather than having a specific antagonist and a specific plot (”okay, this particular villain running an evil organization is trying to accomplish this specific goal that the party will now have to thwart”) I’d rather make a world with a bunch of competing organizations and let the party go nuts. (This sometimes has the downside of them picking a different faction than I had hoped–no, worship the Apollo stand-in, not the Thor stand-in!–but that seems better from a group satisfaction point of view.) And this is also typically the sort of thing that I want as a player–put me in charge of a company that’s trying to get rich and powerful and has a team of professional murderers to solve problems for it, rather than have me chase down some nut who’s out to destroy the world.

But, of course, D&D by default isn’t set up for that sort of thing. (I’m remembering the time when we had a mission to clear a magical disturbance out of a section of forest so it could be logged, and I wanted to buy up the land for cheap first, since we had several thousand gold sloshing around; the DM said “basically, sure you can do that, but you’re not going to get any richer than the wealth-by-level guidelines.” Which is a sensible position–the point of the wealth system in D&D is to give players a sense of reward and points with which to customize their abilities, and having the players turn into merchants / focus on financial schemes and arbitrage rather than dungeon delving is losing the plot / stressing the system seriously. (I mean, imagine if your maxed-Persuasion character decided to start a Ponzi scheme in a world both 1) not particularly financially literate, and thus not particularly resistant to that sort of thing and 2) where those sorts of exponential returns could in fact be delivered by an adventuring party robbing dragons or similar things.)

Another problem that often happens is that people like having lots of character designs. They’ll make a character, play with it for a few sessions, and then think of something else cool they’d like to be. Or perhaps the character will get tactically stale–sure, being an archer is fun, but do you really want to spend twenty sessions as an archer? “Oh, now I get to attack twice in a round!” This leads to a conflict between character arcs and attachment and novelty.

Somewhat connected, trying to get a group of adults to all be available at the same time is remarkably difficult. (Gone are the days when my friends all went to the same school and had vacations at the same time and we could just walk home together and play D&D on Fridays.) When the sessions are highly linked, or the party is traveling together, this leads to bizarre situations where characters are ghosted, absent, ill, or whatever. Some games solve this by being bizarre themselves (in RIFTS, for example, you could just say that a rift swallows a character for that session). But then does the character get experience? A cut of the treasure? If someone being run by the party dies, what happens, especially if it’s a permadeath game?

But if instead of a single party of four people, the players are running a guild of, say, a dozen people that only sends ~4 out on any particular mission, then this works out fine. (Basically any game with a roster works this way.) The number of people you can send depends on the number of people who show up that week (but, if people are comfortable running multiple characters, doesn’t have to be a hard cap). Also include assignments for the people not on the mission, and then when Bob is absent, Bob’s wizard is busy doing something off-screen, like studying or making potions or whatever.

So I expect the next game I run to embrace that aspect from the start. But there’s still a fairly deep uncertainty about what to try to build off of–if there isn’t anything built for this yet, there isn’t going to be anything balanced for this yet / I can’t rely on other people’s design work instead of my own.

The ramping of D&D feels mostly wrong (roughly linear power scaling means sending lvl5 chars on missions is hugely different from sending lvl2 chars on missions, whereas swapping a different character into a Pandemic Legacy game is only slightly different) and the characters seem to have way too much specialization for them to be easily handed off. In Pandemic Legacy, you only need to learn a new special ability to play a different character; in Darkest Dungeon, you only need to understand four abilities to play a different character, and a roughly similar thing is true for Massive Chalice.

Those suggest something like just using Darkest Dungeon’s rules, or a small team minis game like Warmachine or Mobile Frame Zero. (Other contenders: Massive Chalice, XCOM, Fallout Tactics, Renowned Explorers, The Curious Expedition.) The basic things you want from a character are (1) biographical / psychological details, (2) skill / out of combat abilities, and (3) in combat abilities, and ideally all of them together fit on an index card (but an index card for each third might be fine, and it’s also alright if it refers to off-card stuff that the players can be reasonably expected to memorize).

(For example, in Darkest Dungeon, those things are: (1) name/color, (2) traits, campfire abilities, inventory, and trap finding (3) traits, abilities, equipment, hp, and stress. Basically everything fits in class 3, and a similar thing will be true for XCOM and Massive Chalice and so on. For D&D, each of them is considerably deeper.)

Another thing that’s nice about putting it in a reference class with, say, Legacy games is that you can ‘unlock’ new mechanics as you go along or modify existing ones with less of an objection. “Alright, guys, now all characters have ‘stress’ to track along with hit points.” or “This particular spell works differently now.” It makes using a work-in-progress system much more palatable.

I love this. As I’ve been playing Traveller recently, I’ll add that Traveller would make a very good “Guild” game (the “Guild” is a small corporation that has *one* spaceship plus a stationary headquarters, so every session, a crew for that *one* spaceship is assembled and sent out. The fact that there’s only one ship justifies the fact that only a few people go out at a time.

I’ve been thinking about Traveller a lot recently because of your posts (thanks for them, btw!) but I think you run into a major problem with the “one spaceship” strategy.

That is, either the spaceship has to return to the Home Base at the end of every mission, so that you can assemble a new team to send out, or you need to have people conveniently hopping to the right spaceport so they can be there. (How did they know which spaceport? One of the premises of Classic Traveller, at least, is that you have FTL travel without FTL communication, and so it makes sense to have ships physically carrying mail and goods with wildly varying and speculative prices; I don’t know if that’s also a part of how Mongoose’s version is explained.)

Given the pressures to Always Be Trading, having people need to always come back to the home base is probably a rough deal. [Unless you do something like the old DOS game Merchant Prince, where all the players are based out of Venice, which is also the only source of glass, which can be bought at a reasonable price and sold at high prices elsewhere, or the Home Base is on the highly populated rich world where they can generally sell whatever they picked up throughout the rest of the subsector. But this encourages more of a “find a stable loop and grind it” experience than a “be making local greedy decisions that cause you to loop wildly around the subsector” experience.]

It feels better suited to an ‘away team’ style game, where everyone is on the ship (like the Final Fantasy airships) and only ~4 of them land on any particular planet depending on who’s there that week, but then you’re back to the Patrons being the meat instead of the spice.

(I’m not very fluent with the mechanics of Tumblr’s UI, and I’m not sure if “reblog” is the accepted way to respond to this message or if there’s another convention. Also thank you for your compliment!)

I think in my scenario I proposed, the assumption would be that, sometime between the end of the previous session and the start of the next one, the ship returned to home base. You’re right that it brings up a whole host of problems to always have the game start in the same port, not the least of which is that the systems furthest from it may never be visited. These are… pretty big problems, actually, with no easy solution. Drat.

Mongoose Traveller has the same property as classic in that FTL communication doesn’t exist outside of physically carrying mail on spaceships.

I think your ‘away team’ solution is a good one that could definitely work for a lot of groups, but isn’t quite what I’d be looking for–it would require a VERY large spaceship (most that I’ve seen have a crew of 5-10 or so; you’d need two or three times that to have a real ‘stable’ of characters onboard) and it would bring up a couple of issues in play that would be hard to resolve (i.e., “we’re down on this Vulcan planet and it sure would be helpful if Spock was here but he’s… busy… up in space, I guess? He’s taking his PTO?”)

I think we’re circling around something really promising, but I haven’t quite been able to align these pieces satisfactorily.

Parties vs. Guilds

(This is a gaming post, not a politics / economics post.)

So the last D&D game that I ran hit a scheduling conflict, then another, and then stalled to a halt. And in the meantime I started up a Pandemic Legacy game (which goes much faster when you play 3 games per session and one session per week :P ), backed a game that’s reminiscent of Darkest Dungeon (The Iron Oath, 39 hours left in their KickStarter at time of writing), and a friend got into Massive Chalice.

All of which have me thinking about the difference between RPG management / strategy games and tactics games. For example, Massive Chalice has the XCOM flavor where there’s a strategic layer and a tactical layer, which reinforce each other; Darkest Dungeon is similar while the strategic layer feels more lightweight. And in Pandemic Legacy, the strategic layer is basically the durable changes to the board/character/rules.

I notice that when I’m playing D&D, I miss that, and so I often try to bolt something like that on. When DMing, rather than having a specific antagonist and a specific plot (”okay, this particular villain running an evil organization is trying to accomplish this specific goal that the party will now have to thwart”) I’d rather make a world with a bunch of competing organizations and let the party go nuts. (This sometimes has the downside of them picking a different faction than I had hoped–no, worship the Apollo stand-in, not the Thor stand-in!–but that seems better from a group satisfaction point of view.) And this is also typically the sort of thing that I want as a player–put me in charge of a company that’s trying to get rich and powerful and has a team of professional murderers to solve problems for it, rather than have me chase down some nut who’s out to destroy the world.

But, of course, D&D by default isn’t set up for that sort of thing. (I’m remembering the time when we had a mission to clear a magical disturbance out of a section of forest so it could be logged, and I wanted to buy up the land for cheap first, since we had several thousand gold sloshing around; the DM said “basically, sure you can do that, but you’re not going to get any richer than the wealth-by-level guidelines.” Which is a sensible position–the point of the wealth system in D&D is to give players a sense of reward and points with which to customize their abilities, and having the players turn into merchants / focus on financial schemes and arbitrage rather than dungeon delving is losing the plot / stressing the system seriously. (I mean, imagine if your maxed-Persuasion character decided to start a Ponzi scheme in a world both 1) not particularly financially literate, and thus not particularly resistant to that sort of thing and 2) where those sorts of exponential returns could in fact be delivered by an adventuring party robbing dragons or similar things.)

Another problem that often happens is that people like having lots of character designs. They’ll make a character, play with it for a few sessions, and then think of something else cool they’d like to be. Or perhaps the character will get tactically stale–sure, being an archer is fun, but do you really want to spend twenty sessions as an archer? “Oh, now I get to attack twice in a round!” This leads to a conflict between character arcs and attachment and novelty.

Somewhat connected, trying to get a group of adults to all be available at the same time is remarkably difficult. (Gone are the days when my friends all went to the same school and had vacations at the same time and we could just walk home together and play D&D on Fridays.) When the sessions are highly linked, or the party is traveling together, this leads to bizarre situations where characters are ghosted, absent, ill, or whatever. Some games solve this by being bizarre themselves (in RIFTS, for example, you could just say that a rift swallows a character for that session). But then does the character get experience? A cut of the treasure? If someone being run by the party dies, what happens, especially if it’s a permadeath game?

But if instead of a single party of four people, the players are running a guild of, say, a dozen people that only sends ~4 out on any particular mission, then this works out fine. (Basically any game with a roster works this way.) The number of people you can send depends on the number of people who show up that week (but, if people are comfortable running multiple characters, doesn’t have to be a hard cap). Also include assignments for the people not on the mission, and then when Bob is absent, Bob’s wizard is busy doing something off-screen, like studying or making potions or whatever.

So I expect the next game I run to embrace that aspect from the start. But there’s still a fairly deep uncertainty about what to try to build off of–if there isn’t anything built for this yet, there isn’t going to be anything balanced for this yet / I can’t rely on other people’s design work instead of my own.

The ramping of D&D feels mostly wrong (roughly linear power scaling means sending lvl5 chars on missions is hugely different from sending lvl2 chars on missions, whereas swapping a different character into a Pandemic Legacy game is only slightly different) and the characters seem to have way too much specialization for them to be easily handed off. In Pandemic Legacy, you only need to learn a new special ability to play a different character; in Darkest Dungeon, you only need to understand four abilities to play a different character, and a roughly similar thing is true for Massive Chalice.

Those suggest something like just using Darkest Dungeon’s rules, or a small team minis game like Warmachine or Mobile Frame Zero. (Other contenders: Massive Chalice, XCOM, Fallout Tactics, Renowned Explorers, The Curious Expedition.) The basic things you want from a character are (1) biographical / psychological details, (2) skill / out of combat abilities, and (3) in combat abilities, and ideally all of them together fit on an index card (but an index card for each third might be fine, and it’s also alright if it refers to off-card stuff that the players can be reasonably expected to memorize).

(For example, in Darkest Dungeon, those things are: (1) name/color, (2) traits, campfire abilities, inventory, and trap finding (3) traits, abilities, equipment, hp, and stress. Basically everything fits in class 3, and a similar thing will be true for XCOM and Massive Chalice and so on. For D&D, each of them is considerably deeper.)

Another thing that’s nice about putting it in a reference class with, say, Legacy games is that you can ‘unlock’ new mechanics as you go along or modify existing ones with less of an objection. “Alright, guys, now all characters have ‘stress’ to track along with hit points.” or “This particular spell works differently now.” It makes using a work-in-progress system much more palatable.

I love this. As I’ve been playing Traveller recently, I’ll add that Traveller would make a very good “Guild” game (the “Guild” is a small corporation that has *one* spaceship plus a stationary headquarters, so every session, a crew for that *one* spaceship is assembled and sent out. The fact that there’s only one ship justifies the fact that only a few people go out at a time.

On the Four Table Legs of Traveller, Leg 4: Random Encounters

In part 1

of this series, I described how Mongoose Traveller’s

spaceship mortgage rule becomes the drive for adventure and action in a

spacefaring sandbox, and the ‘autonomous’ gameplay loop that follows.

In part 2,

I talked about how Traveller’s Patron

system gives the DM a tool to pull the party out of the 'loop’ and into more

traditional adventures.

In part 3,

I talked about Traveller’s unique

character creation system, and how it supports the previous two systems, and

how to avoid some of the pitfalls that I’ve seen in play.

In this

part, I’ll talk about how each of these three systems interacts with, and in

fact, relies upon, Traveller’s random

encounters.

of Traveller

Traveller really takes the concept of random encounters

and runs with it. Just in the core

rulebook, there are random encounters for…

-

Encounters

during space travel (with different sub-tables for travel near a space port, in

settled space, wild space, and so on),

-

Encounters

on foot in a starport, rural area, and urban area,

-

Encounters

with the law (that is, random legal complications tables for accidentally or

deliberately breaking laws on strange new worlds)

There are

also several 'honorary mention’ tables that interact with the random encounter

tables, such as:

-

Random

asteroid and random salvage tables,

-

Random

passenger tables,

-

Random

“bounty hunters come to repossess your ship if you didn’t pay your

mortgage” tables

-

Full

random monster generator tables—this one is particularly impressive. When an

alien 'animal’ is encountered, rather than having hundreds of pages of animals,

it seamlessly moves into generating a fully-unique animal on the fly

-

Random

patron tables (these are truly in-depth: they generate who your patron is, what

you’re asked to do, random targets for your mission, and even who the

opposition is).

-

A

random piracy table (unfortunately buried in the spacecraft chapter, not near

the table where pirate encounters are rolled), that provides inspiration for

just how the pirates manage to get the jump on the party and what they want.

-

Of

course, special mention goes out to the procedural subsector generator which is

a full chapter in the book, in which the DM can generate the entire setting for

the campaign.

What’s

impressive about Traveller isn’t so

much the volume, or even the quality, of the random tables, but how tightly

they’re tied into each of the other game’s systems

As Traveller is a game primarily about

space travel, I’ll focus on the Space Encounter table.

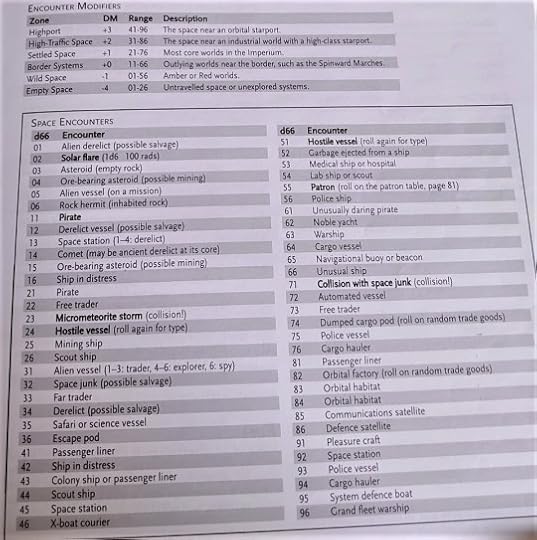

Sorry for the janky photo; I don’t have the

book on pdf. (Traveller Core Rulebook, 2008,

p139)

This table

is rolled on pretty much whenever the DM feels like it (the rules say: “roll

1d6 every week, day, or hour depending on how busy local space is. On a 6 […]

roll d66 on the table below”). Many of these results tie in to subtables

(any result of salvage, collision, mining, trade goods, or patron has

additional rolls), but the photo above contains the most important part of the

space encounter system.

Compare

this table to the one from D&D’s Manual

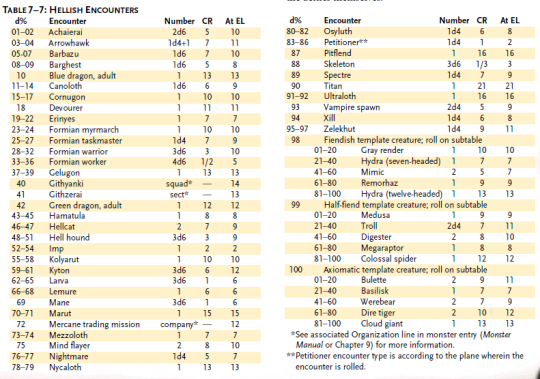

of the Planes I used as an example in my series on wandering monsters:

Manual of the

Planes, 2001. p. 151

Now,

obviously, D&D’s encounter table here is for an explicitly dangerous place—literally

Hell—but the only result you can roll

on the table that doesn’t immediately move

to combat is “72: Mercane trading mission.” Thus, any time this table

is rolled, there is a 99% chance of initiative

being rolled.

Traveller’s random encounter table marks its

“unavoidable” encounters in bold (typically they’re ones that

immediately start a battle or some kind of dangerous phenomenon like a collision),

though “patron” is also on there. There are only 7 results that are

bolded this way, and only 6 of them are explicitly dangerous. Some of the

non-bold rolls can result in battles as well depending on the party’s actions,

but there’s no assumption of violence.

This is

representative of most of Traveller’s

random encounter tables: they’re not, by and large, random battle tables, but universe

simulators. Depending on the context of the adventure, this means the

random space encounter table could mean one of a number of different things.

For example:

-

If

the players are pirates, this becomes a random pirate target table. Most of the results are unarmed NPC ships that

would be perfect targets for piracy. However, some are police or military

vessels that would cause real problems for the party.

-

If

the players are blue-collar miners and salvagers, this becomes a random treasure table, where the

various derelict, asteroid, and salvage options become possibilities for work.

-

If

the players are in trouble (suffering from a medical emergency or a mechanical

failure), this becomes a random rescue

table, where you get to find out who answers your distress beacon, and what

their intentions might be. Additionally, the tables tell you how long it takes for rescue to arrive

(for example, in lightly inhabited space, you have a 1-in-6 chance every week that a spaceship shows up. At

that point, you’re running up against hard limitations of fuel reserves on your

ship as to whether life support will give out before rescue arrives)

-

If

the players are simple traders, this table is a random flavour table, mostly adding a bit of flavour to the world while

only occasionally having major impact on play.

“That’s

all well and good,” you say, “but what does this have to do with

tables?”

Even with

the bank taking most of the party’s trade profit, without close attention to

random encounters, the 'trade loop’ can quickly turn into a 'roll dice and

watch numbers grow’ game. In a single iteration of the trade system, a lot of random encounters are rolled:

-

A

Space Encounter in the origin system while flying to the 100-diameter limit

(you can’t safely use Traveller’s FTL

drives within 100-diameters of a planet),

-

A

Space Encounter in the destination system while flying to the world from the

100-diameter limit (in the case of a mis-jump, which lands you far from the

target world, this can use the more-dangerous less-settled options on the

encounter table),

-

A

Legal Trouble Encounter check upon docking with the new spaceport,

-

One

or more Spaceport Encounter checks while in the spaceport and picking up cargo.

-

One

or more Random Passenger rolls if passengers are picked up

That’s four

or more rolls on random tables just going from one planet to another. This

means that what might otherwise seem to be a straightforward (and therefore

boring) trading game becomes, in practice, a series of minor adventures and

close escapes full of danger. Remember, any time a pirate is encountered,

there’s a real possibility the players will be forced to jettison their cargo,

which typically represents all of their

accumulated wealth. The stakes are very

high.

These high stakes

also provide motivation for your players to accumulate wealth beyond simply

keeping the banks off their backs: ship-scale weapon systems are very expensive (in the millions of

credits), but even one or two upgrades to a basic ship can give the party a

huge leg-up against non-player ships (who usually fly unmodified ships lifted directly

from the book).

Virtually

every random encounter table has a one or two entries that result in the party

meeting a patron, which, as I described in the second part of this series,

are the keys to adventure in Traveller.

Math isn’t my strong suit, but back-of-the-napkin calculations suggest that

around one-in-five trips between worlds will involve a run-in with a patron,

and thus the start of a classic-style adventure. Note that while the book does provide tables to generate patrons,

it really isn’t practical to do this on the fly. What this does mean is that, as DM, when you have a free afternoon or just a

couple of hours, you can create and queue up your own patrons in advance and

trust that, at some point, the game’s

procedural universe simulation will put them in front of the party.

Creation

Traveller’s character creation system is different. So different, in fact, that it can be tempting to cut it out altogether and replace it with something conventional.

The

rulebook recommends that, if possible, patrons should be drawn from the PCs’

existing contacts and allies. I don’t think it explicitly mentions this, but

hostile encounters should also often include the PCs’ existing enemies and

rivals. This ties player characters’ backgrounds directly into the action of

the game’s 'present’ timeline. In addition, it’s actually much easier as DM to pull out a character that you already have in

your rolodex sometimes than come up with a new, characterful pirate captain for

each random encounter.

Unless you really know what you’re doing, Traveller runs a serious risk of

collapsing if any of these four legs (mortgages/trade, patrons, character

creation, and random encounters) is removed or seriously modified.

Unfortunately, the game doesn’t make this clear in any particular way, which is

why my previous DM (who, again, is very good)

struggled visibly with his two campaigns.

If you decide mortgages won’t be a major aspect of

the game, you have to remove or severely nerf the trade rules, or your

party will be rolling in cash almost

immediately. Because the trade rules are the primary motivation to move around

(and thus, roll random encounters), you have to come up with another reason for

them to do so. (Note that it’s possible,

during character creation, to be loaned a Scout Ship without having to pay

mortgages on it. As DM, you should consider disallowing this, or at least be

aware of the implications if this reward is rolled)

If you decide trading won’t be a major aspect of

this game, you have to find

another way for the party to make money (lots

of money) or they simply won’t be able to pay their mortgage. You also have to find a reason for them to

travel from place to place, or they won’t be able to justify the cost of fuel,

crew salary, and other expenses. The game will run serious risk of defaulting to

jumping from one patron job to another. This isn’t inherently bad, but it’s a lot of work for the DM, and, at some

point, becomes a railroad of quest-to-quest with no other real alternative.

You’re also cutting off the party from meaningfully interacting with the

spaceship upgrade system—there’s pretty much no other way to raise the millions

of credits needed to buy extra laser turrets and stuff for their ship.

If you decide patrons won’t be a major aspect of

the game, you might find that the party never

leaves their spaceship. Skills other than those related to trading and

spacecraft operation will never be used, most of the equipment chapter and the

encounters and danger chapter will be left unread, and those wild and unique

planets you spent ages generating before the campaign will go completely

unnoticed.

If you decide Traveller’s

character creation is too unbalanced and ought to be replaced by a

point-buy system, you might struggle to weave the players’ contacts,

rivals, allies, and enemies into the campaign (if they even have those), and

you might miss out on having hired NPCs running around on the spaceship. This

in turn means that there’s many fewer opportunities for roleplaying during

travel. Additionally, your players might then operate with the expectation that

Traveller will have anything

resembling game balance, and, as such, be frustrated by the game’s hugely

uneven random encounters.

If you decide random encounters won’t be a major

aspect of the game, you might find that the party never meets a patron, never has

the opportunity to engage in piracy, never has any trouble watching their

credits climb and climb indefinitely, and never has much motivation to make

money (and thus, go on adventures and travel around) beyond paying off their

mortgage.

July 20, 2020

i find it really surprising to read you write “For a D&D campaign, you usually come to the table with a more-or-less fully-fledged character concept” or “Traveller is very different from most D&D-esque RPGs. It doesn’t provide any guidance for or benefit f

Right, I probably should have mentioned this in the article. I personally started meaningfully playing D&D with 3.0 (I played 2e with a babysitter, but only dimly remember it). As a result, I can’t speak to pre-3.0 D&D with any authority, so when I say “D&D” I’m usually referring to 3.0e/3.5e/D20 modern/Pathfinder/5e. I largely gave 4e a pass; it wasn’t really “for me”.

From 3.0 on, striving (and often failing to achieve) balance in one way or another (between each party member, between party members and monsters, between choices of feats and weapons) has always been a major part of the game’s design. So for me, Traveller is really my first foray into an RPG that doesn’t even pay lip-service to balance. Frankly, it’s deeply refreshing. As you point out, it certainly isn’t a new idea overall, but it’s a new idea to me.

I hope you don’t mind me posting this publicly; I can take it down if you want. I think it’s a valuable tidbit of conversation that adds meaningfully to my posts on Traveller.

i find it really surprising to read you write "For a D&D campaign, you usually come to the table with a more-or-less fully-fledged character concept" or "Traveller is very different from most D&D-esque RPGs. It doesn’t provide any guidance for or benefi

Right, I probably should have mentioned this in the article. I personally started meaningfully playing D&D with 3.0 (I played 2e with a babysitter, but only dimly remember it). As a result, I can’t speak to pre-3.0 D&D with any authority, so when I say “D&D” I’m usually referring to 3.0e/3.5e/D20 modern/Pathfinder/5e. I largely gave 4e a pass; it wasn’t really “for me”.

From 3.0 on, striving (and often failing to achieve) balance in one way or another (between each party member, between party members and monsters, between choices of feats and weapons) has always been a major part of the game’s design. So for me, Traveller is really my first foray into an RPG that doesn’t even pay lip-service to balance. Frankly, it’s deeply refreshing. As you point out, it certainly isn’t a new idea overall, but it’s a new idea to me.

I hope you don’t mind me posting this publicly; I can take it down if you want. I think it’s a valuable tidbit of conversation that adds meaningfully to my posts on Traveller.

Sir Poley's Blog

- Sir Poley's profile

- 21 followers