Anne Charnock's Blog

January 15, 2026

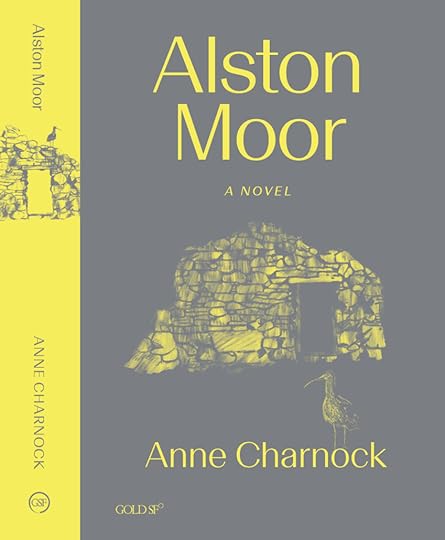

Alston Moor: Cover Reveal

I’m thrilled to reveal the stunning cover (and spine) art for my forthcoming novel, ALSTON MOOR, which will be published on 29 September 2026 by Goldsmiths Press/Gold SF. I’m immensely grateful to cover art designer Heather Ryerson and the Goldsmiths’ team.

To bring this novel to fruition I’ve immersed myself in the science of peatlands and the history of the North Pennines. The novel is shaped by moorland walks and my visits to restoration projects on remote peatbogs! It’s been both challenging and fun, and I can’t wait to see Alston Moor in print.

From the publisher:

In an epic novel set on the North Pennine moors, Elizabeth has abandoned avalanche science to restore desolate peatlands. She treks in the footsteps of Isabel who, five centuries earlier, herds her cattle to remote summering grounds.

Both are reeling from the overwhelming crises of their day. In 1548, Isabel and her father, together with the priest in this poorest of parishes, grapple with the chaos of the protestant reformation. Today, a grieving Elizabeth fights to save an invaluable ecosystem, one that is threatened by wilful fire-raising and arson.

The entwined stories are told through multiple voices creating a rich portrait of England’s most remote landscape. At its heart, this deeply moving novel interrogates how society confronts crisis whether through science, faith or superstition.

More updates as they come!

The post Alston Moor: Cover Reveal appeared first on Anne Charnock.

December 30, 2025

My best reads of 2025

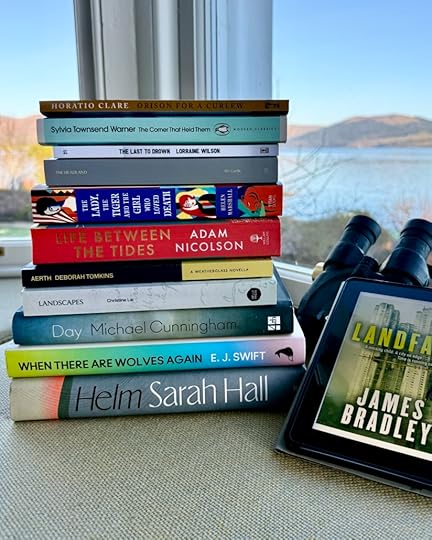

Judging by my spreadsheet ‘Books Read in 2025’, I have enjoyed an excellent year whether I’ve been reading for research or reading classics or keeping up with contemporary fiction. Here is a selection of my favourites together with a brief update on my writing year.

I like to start the year with a book of nature writing. To fill this seasonal slot, I read Adam Nicolson’s Life Between the Tides: In Search of Rockpools and Other Adventures Along the Shore. This delightful book helped me to appreciate, more deeply, the inter-tidal zones on the Isle of Bute where I have lived for the past eight years.

Michael Cunningham is a must-read author for me, and his novel Day became another early read in 2025. It did not disappoint. Day is a tender portrayal of love and loss, set during lockdown, and it’s yet another Cunningham masterpiece. I love everything he writes!

As per usual, I look out for novels with a climate/ecological angle. In that field, I’ve thoroughly enjoyed James Bradley’s speculative crime novel Landfall and Christine Lai’s near-future novel, Landscapes. And I read in manuscript E. J. Swift’s When There Are Wolves Again, which is an excellent pairing with her previous novel, The Coral Bones.

I am always drawn to novels with fragmented narratives especially those with a thread of historical fiction (I included a historical storyline in my second novel Sleeping Embers of an Ordinary Mind, and there’s a substantial historical element in my upcoming novel Alston Moor). This year I devoured Sarah Hall’s epic, multi-stranded novel Helm spanning from neolithic to contemporary times. The titular Helm is Britain’s only named wind. I also enjoyed Helen Marshall’s structurally complex novel, The Lady, The Tiger and The Girl Who Loved Death – another book I read in manuscript. The political and propaganda themes in this fantasy novel really drew me in.

Throughout 2025, I’ve found myself committed to reading a mass of non-fiction as research for my current work-in-progress. So, I’ve taken periodic breathers from heavy tomes by reading a number of compelling novellas including Aerth by Deborah Tomkins (winner of the Weatherglass Novella Prize) and The Last To Drown by Lorraine Wilson.

Somewhat belatedly, I read the brilliant, short memoir/travelogue, Orison for a Curlew: In Search of a Bird on the Edge of Extinction by Horatio Clare. An homage to the slender-billed curlew, this is also the human story of the birdwatchers and conservationists who have sighted this near-extinct bird.

Among several other novels I have admired, the ones that stayed with me are One Boat by Jonathan Buckley, and The Headland by Abi Curtis.

Despite the fact I’d finished writing Alston Moor, I have continued reading books relating, one way or another, to that novel. A case in point: prompted by an episode on the Backlisted podcast, I read The Corner That Held Them by Sylvia Townsend Warner, set in a medieval Norfolk convent. Unputdownable, for me at least!

Following several years of research and drafting, my fifth novel – Alston Moor – will be published in Autumn 2026 by Goldsmiths Press/Gold SF. Edits are now complete and I will be revealing the cover art soon!

Digital Advanced Reader Copies will be available for reviewers from Goldsmiths Press/GoldSF in the coming weeks.

In the meantime, I am scouring everyone’s end-of-year roundups to discover must-read books, which will jump to the top of the pile!

Wishing you all an eventful yet peaceful 2026.

Happy reading everyone!

The post My best reads of 2025 appeared first on Anne Charnock.

September 24, 2025

Goldsmiths Press to publish my latest novel Alston Moor

I am totally thrilled that Goldsmiths Press will be publishing my novel Alston Moor in the Autumn of 2026 as part of the press’s Gold SF feminist series. Alston Moor is a work of eco-fiction with two parallel storylines set 500 years apart. I have adored every minute I’ve spent on research for this novel, whether I’ve been hiking on the North Pennines or reading texts detailing late-medieval life in this remotest of English landscapes.

I can’t wait to see this novel out in the world. Patience!

The entwined stories are told through multiple voices including cattle-herding Isabel and peatlands scientist Elizabeth who are both reeling from the overwhelming crises of their day: the eradication of religious traditions during the English Reformation and the impending ecosystem collapse of today.

Copy edits are imminent. And I am already enjoying working with the excellent Goldsmiths Press/Gold SF team.

Watch this space…

NOTE: Goldsmiths Press has acquired World English Language rights. All foreign rights and film & tv requests to assistant at sarah-such dot com at the Sarah Such Literary Agency, UK.

Happy reading, everyone!

The post Goldsmiths Press to publish my latest novel Alston Moor appeared first on Anne Charnock.

December 29, 2024

My best reads of 2024

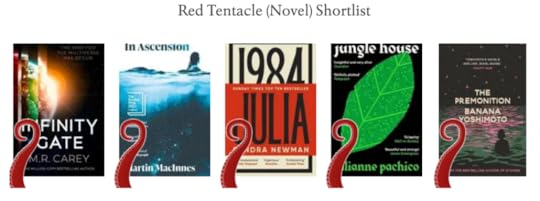

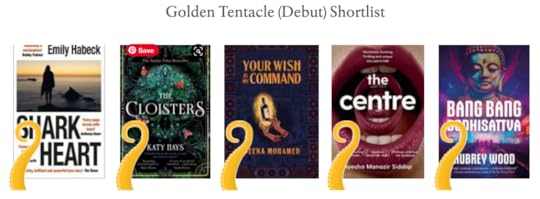

This year I smashed through all my previous records for number-of-books-read. How did I manage that? Well, I joined the jury for The Kitschies Awards along with Leila Abu El Hawa, Nick Mamatas and Molly Tanzer. Not surprisingly, my best reads of 2024 can be summarised by reminding you of the shortlists. It was such fun to spend the year talking books. And I’m pleased to say that the judges were in very close agreement on the shortlists and winners!

The awards search out progressive, intelligent and entertaining novels with a speculative element. Back in 2014 – a decade ago! – I was bowled over when my novel A Calculated Life was shortlisted for The Kitschies debut award. So, I have a fondness for their shortlists, which invariably bring overlooked books to our attention.

Sadly, this turned out to be the last year of the Kitschies. So, in retrospect, I feel doubly delighted and honoured to have joined the jury for the Red Tentacle (Best Novel) won by Julia by Sandra Newman, and the Golden Tentacle (Best Debut) won by The Centre by Ayesha Manazir Siddiqi.

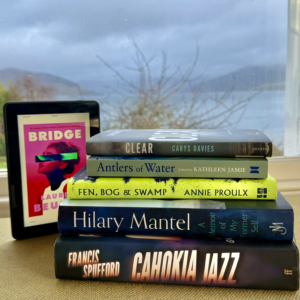

Needless to say, in the course of reading the submissions, I came across a number of speculative novels that made a great impression on me and I can heartily recommend two alternate history novels – Cahokia Jazz by Francis Spufford and Biography of X by Catherine Lacey. Also, I thoroughly enjoyed the multiverse novel Bridge by Lauren Beukes for its fascinating exploration of a mother-daughter relationship. One of the debut novels that impressed me was Sarah K Jackson’s Not Alone, which combined a post-apocalyptic story with wonderful nature writing.

Beyond reading for the awards, I dipped into non-fiction anthologies and collections for the sake of varying my diet! I adored Hilary Mantel’s A Memoir of My Former Self, which brings together her essays and other non-fiction works including film reviews and her Reith Lectures. I have also appreciated Antlers of Water, Writing on the Nature and Environment of Scotland edited by Kathleen Jamie. Plus Fen, Bog and Swamp by Annie Proulx.

In May, I spent a few sunny days at Hay Literature Festival and caught fascinating talks about bird watching by Hamza Yassin and Mark Cocker. And having already read Cahokia Jazz, I made a bee-line for Francis Spufford’s interview – a totally engaging insight into his research. During October, I visited Wigtown Book Festival in Dumfries and Galloway, and the highlight was a conversation between author Carys Davies and critic Stuart Kelly about Davies’ brilliant historical novel, Clear.

And, most recently, I’ve enjoyed something completely different – Ursula K Le Guin’s generation-starship novella, Paradises Lost.

Two of my favourite novels of 2023 (In Ascension by Martin MacInnes and Orbital by Samantha Harvey) featured this month on Barack Obama’s best reads of the year. Not that I’m suggesting the former president follows my book recommendations! (But let’s see which books he selects next year).

On my bedside table, I have a mountain of books that I simply didn’t have time to read this year. I now want to read them all at the same time! I’m desperate to get to the following, in no particular order:

Curandera by Irenosen Okojie, Parade by Rachel Cusk, 381 by Aliya Whiteley, The Deluge by Stephen Markley, Day by Michael Cunningham, Creation Lake by Rachel Kushner, Stone Yard Devotional by Charlotte Wood, The Last White Man by Mohsin Hamid, The Work of Art by Adam Moss, The Ministry of Time by Kaliane Bradley.

Will I read them all in 2025, or will I be diverted throughout the year, as usually happens, by recommendations from other writers, reviewers and readers? Already I must add Deborah Levy’s The Position of Spoons which I received as a gift – a book I can’t wait to read having devoured all her memoirs to date.

And no doubt when I read other end-of-year lists, my TBR pile will immediately double in height!

Happy reading, everyone! All my best wishes for 2025!

The post My best reads of 2024 appeared first on Anne Charnock.

April 30, 2024

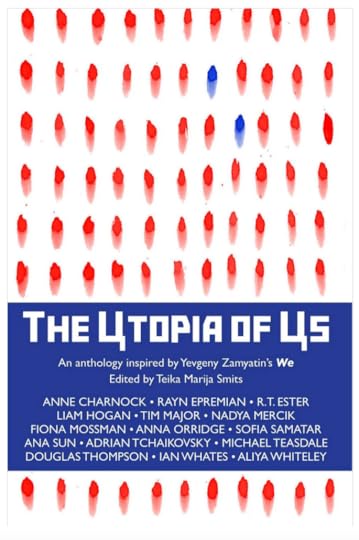

The Utopia of Us: Me and WE

When I heard about plans for a Yevgeny Zamyatin-inspired anthology, I knew instantly I would love to be included. I’m delighted my short story “The Earth Heals – Silent Days – Vagaries and Savagery” will appear in this special anniversary anthology, which marks the 100th anniversary of the publication of Zamyatin’s dystopia WE.

Edited my Teika Marija Smits and published by Luna Press Publishing on the 28th May, The Utopia of Us is now available for Pre-Order.

Each contributor to the anthology has writtten an introduction to their short story to explain their personal connection to Zamyatin’s WE. These introductions will appear on the Luna Press website through the month of May in the lead-up to the book’s release. And my introduction is here.

Full list of contributors below. So chuffed to be among them! And I can’t wait to read the anthology myself.

The post The Utopia of Us: Me and WE appeared first on Anne Charnock.

December 28, 2023

My best reads of 2023!

Throughout December, I Iook forward to hearing about everyone’s favourite books of the year. Looking back on my own reading notes for 2023, I notice that compared to recent years I’ve read books published relatively recently. I think this is a good indication that this has been a stellar period for my kind of fiction. Here are several I can thoroughly recommend – the books that have stayed with me:

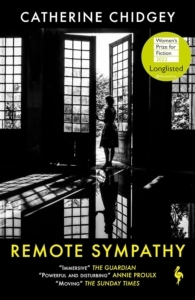

Remote Sympathy by Catherine Chidsey (Europa Editions, 2021)

One of my first reads of the year dealt with grim subject matter. Remote Sympathy is set in World War 2 in the environs of the Buchenwald concentration camp. We see the camp from the perimeter, so to speak, as seen by the families of the SS German officers who operated the camp. It details how one woman in particular, Frau Greta Hahn, fails to grasp the truth that lies behind that perimeter fence. That is, until she becomes increasingly dependent on an inmate, Lenard Weber, a former physician, who is allocated to the Hahn family as a servant. It’s a totally immersive novel, beautifully crafted.

One of my first reads of the year dealt with grim subject matter. Remote Sympathy is set in World War 2 in the environs of the Buchenwald concentration camp. We see the camp from the perimeter, so to speak, as seen by the families of the SS German officers who operated the camp. It details how one woman in particular, Frau Greta Hahn, fails to grasp the truth that lies behind that perimeter fence. That is, until she becomes increasingly dependent on an inmate, Lenard Weber, a former physician, who is allocated to the Hahn family as a servant. It’s a totally immersive novel, beautifully crafted.

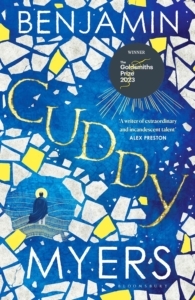

Cuddy by Benjamin Myers (Bloomsbury Circus, 2023)

This is definitely one of my top novels of recent years. Cuddy won the 2023 Goldsmiths Prize and was shortlisted for the Booker. It’s an ambitious, experimental, epic novel, which spans from Lindisfarne in the 8th century to a present-day austerity Britain. Written in four parts, the novel is held together by the story of St Cuthbert (the titular Cuddy), a hermit and unofficial patron saint of the north of England.

This is definitely one of my top novels of recent years. Cuddy won the 2023 Goldsmiths Prize and was shortlisted for the Booker. It’s an ambitious, experimental, epic novel, which spans from Lindisfarne in the 8th century to a present-day austerity Britain. Written in four parts, the novel is held together by the story of St Cuthbert (the titular Cuddy), a hermit and unofficial patron saint of the north of England.

Boy Parts by Eliza Clark (Influx, 2020)

Boy Parts had been on my TBR pile since it was published by Influx. But somehow it took me three years to get around to starting it. I found myself blown away by this dark comedy, which follows art photographer Irina as she persuades young men to model for her in explicit poses. Shocking, funny and engrossing, I could not put this book down.

Boy Parts had been on my TBR pile since it was published by Influx. But somehow it took me three years to get around to starting it. I found myself blown away by this dark comedy, which follows art photographer Irina as she persuades young men to model for her in explicit poses. Shocking, funny and engrossing, I could not put this book down.

His Bloody Project – Graeme Macrae Burnet (Saraband, 2016)

After reading and loving Case Studies by Graeme Macrae Burnet, I decided I should go back and read his highly acclaimed earlier novel, His Bloody Project (shortlisted for the Man Booker 2016). I am partial to historical fiction, and this novel, set in 1869 in the Scottish Highlands, delivers a totally riveting and psychologically intense reading experience. The author portrays the malicious undercurrents in a small highland community – undercurrents that lead to murderous hatred.

After reading and loving Case Studies by Graeme Macrae Burnet, I decided I should go back and read his highly acclaimed earlier novel, His Bloody Project (shortlisted for the Man Booker 2016). I am partial to historical fiction, and this novel, set in 1869 in the Scottish Highlands, delivers a totally riveting and psychologically intense reading experience. The author portrays the malicious undercurrents in a small highland community – undercurrents that lead to murderous hatred.

Demon Copperhead by Kingsolver (Faber and Faber, 2022)

In Demon Copperhead, Barbara Kingsolver takes aim at the ongoing and tragic crisis of opioid addiction, in a modern retelling of Charles Dickens’ David Copperfield. Winner of 2023 Women’s Prize and co-recipient of the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction, it’s a convincing novel with rich, believable characters. I admit I nearly bailed when the novel took a deep dive into American football culture, but I’m glad I persisted. Slightly too long, but an ambitious novel that achieves its aims.

In Demon Copperhead, Barbara Kingsolver takes aim at the ongoing and tragic crisis of opioid addiction, in a modern retelling of Charles Dickens’ David Copperfield. Winner of 2023 Women’s Prize and co-recipient of the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction, it’s a convincing novel with rich, believable characters. I admit I nearly bailed when the novel took a deep dive into American football culture, but I’m glad I persisted. Slightly too long, but an ambitious novel that achieves its aims.

In Ascension by Martin MacInnes (Atlantic, 2023)

An equally sprawling (in a good way) novel, In Ascension takes the reader from the thermal vents on the ocean floor to a space mission to the edge of the solar system investigating a suspected alien first-contact. The main character is marine biologist Dr Leigh Hasenboch who, as a child, found a temporary escape from her dysfunctional family by swimming outdoors. The story returns repeatedly to Leigh’s fraught relationship with her sister and parents. In Ascension was longlisted for the Booker Prize and has rightly gained a wide readership. An ambitious novel, gorgeous prose, heart-rending and absorbing, with an ending that works well for me.

An equally sprawling (in a good way) novel, In Ascension takes the reader from the thermal vents on the ocean floor to a space mission to the edge of the solar system investigating a suspected alien first-contact. The main character is marine biologist Dr Leigh Hasenboch who, as a child, found a temporary escape from her dysfunctional family by swimming outdoors. The story returns repeatedly to Leigh’s fraught relationship with her sister and parents. In Ascension was longlisted for the Booker Prize and has rightly gained a wide readership. An ambitious novel, gorgeous prose, heart-rending and absorbing, with an ending that works well for me.

Prophet Song by Paul Lynch (Oneworld, 2023)

Winner of this year’s Booker prize, Prophet Song is a dystopia set in Dublin. An authoritarian regime has come to power and is attempting to suppress rebel incursions. Paul Lynch asks an ages-old question: when do you know it’s time to leave? Or, to put it another way: why do some people leave it too late? The story is centred on Eilish Stack, mother of four, who is fending as best she can following the detention of her detective husband by the secret police. By association she comes under suspicion and loses her job as a scientist. Her elder son leaves Dublin to join the rebels, while she clings to old routines, reluctant to take help from her sister living in Canada. It’s good to see a dystopia winning the Booker!

Winner of this year’s Booker prize, Prophet Song is a dystopia set in Dublin. An authoritarian regime has come to power and is attempting to suppress rebel incursions. Paul Lynch asks an ages-old question: when do you know it’s time to leave? Or, to put it another way: why do some people leave it too late? The story is centred on Eilish Stack, mother of four, who is fending as best she can following the detention of her detective husband by the secret police. By association she comes under suspicion and loses her job as a scientist. Her elder son leaves Dublin to join the rebels, while she clings to old routines, reluctant to take help from her sister living in Canada. It’s good to see a dystopia winning the Booker!

Orbital by Samantha Harvey (Jonathan Cape, 2023)

Top marks for a succinct, beautifully written novel set on a space station orbiting earth. Six astronauts carry out their experiments while observing the earth with wonder. Time has little meaning on the space station, which orbits the earth 16 times in 24 hours. Samantha Harvey describes the ‘whipcrack of dawn’ that the astronauts experience time and time again each day. They observe their home planet where the boundaries between countries are invisible. Earth appears natural and beautiful. But the astronauts come to a startling realisation that the earth is not unspoilt. Human impact on the natural world is everywhere in evidence once they look for it. This short novel includes a simple but useful map, which shows the 16 orbits made by the astronauts in this one fictional day.

Top marks for a succinct, beautifully written novel set on a space station orbiting earth. Six astronauts carry out their experiments while observing the earth with wonder. Time has little meaning on the space station, which orbits the earth 16 times in 24 hours. Samantha Harvey describes the ‘whipcrack of dawn’ that the astronauts experience time and time again each day. They observe their home planet where the boundaries between countries are invisible. Earth appears natural and beautiful. But the astronauts come to a startling realisation that the earth is not unspoilt. Human impact on the natural world is everywhere in evidence once they look for it. This short novel includes a simple but useful map, which shows the 16 orbits made by the astronauts in this one fictional day.

Julia by Sandra Newman (Granta, 2023)

How can any writer of speculative fiction resist this retelling of George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four, written from the perspective of Julia? In Sandra Newman’s novel we see Julia as a reckless adventurer within the world of Oceania as she pursues sexual encounters which are not sanctioned. She becomes an agent for inner party member, O’Brian, setting honey traps and encouraging her victims to denounce Big Brother. We learn about Julia’s fascinating backstory, we revisit the rat scene in Room 101, and we are rewarded by Newman’s fascinating and satisfactory conclusion.

How can any writer of speculative fiction resist this retelling of George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four, written from the perspective of Julia? In Sandra Newman’s novel we see Julia as a reckless adventurer within the world of Oceania as she pursues sexual encounters which are not sanctioned. She becomes an agent for inner party member, O’Brian, setting honey traps and encouraging her victims to denounce Big Brother. We learn about Julia’s fascinating backstory, we revisit the rat scene in Room 101, and we are rewarded by Newman’s fascinating and satisfactory conclusion.

Currently on the bedside table:

The Deluge by Stephen Markley, which I am loving (though this is a long, long book), The Last White Man by Mohsin Hamid, I Am, I Am, I Am by Maggie O’Farrell.

———————-

While I am here, I am delighted that my essay on Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale was published this year in Dead Ink’s Writing the Future, edited by Dan Coxon and Richard V. Hirst. You can buy it here direct from Dead Ink!

Also, I am interviewed for the Friends of the Earth podcast series Imagining Tomorrow, launched earlier this month. In this uplifting series, award-winning podcaster and author Emma Newman pieces together the roadmap to utopia by interviewing inventors, communities and science fiction authors.

Happy reading and listening, everyone!

The post My best reads of 2023! appeared first on Anne Charnock.

September 7, 2023

Writing the Future anthology published by Dead Ink

It’s publication day for Writing the Future, an anthology of essays edited by Dan Coxon and Richard V Hirst, and published by Dead Ink. My contribution is a Spotlight essay on Margaret Atwood titled “The Shifting Sands of Plausibility. Reflections on The Handmaid’s Tale”.

Cover design by Luke Bird. Typeset by Laura Jones.

I am delighted to find myself in fine company in this book! According to the back cover blurb:

Writing the Future gathers some of the best contemporary writers of science fiction, speculative fiction, dystopia and eco-fiction to explain their craft and explore the many worlds upon which our imaginations might land.

Here is the full list of contributors:

Nina Allan, Rachelle Atalla, Anne Charnock, Tendai Huchu, Oliver Langmead, Toby Litt, Adam Marek, Una McCormack, Maura McHugh, James Miller, Adam Roberts, Aliya Whiteley, Marian Womack.

The collection has received praise from the Australian author of Ghost Species, James Bradley:

A marvellous combination of critical insight and reflections on practice, Writing the Future doesn’t just offer an array of fascinating perspectives on the ways speculative modes enlarge and illuminate the world that is taking shape around us, it opens up new ways of thinking about the business of creating those worlds.

And From Adrian Tchaikovsy, author of Children of Time:

A glittering array of ideas and analysis from some of the most incisive minds in the business.

Writing the Future is a follow-on from Dead Ink’s award-winning anthology Writing the Uncanny. You can order these books from your favourite bookstore or order direct from Dead Ink.

The post Writing the Future anthology published by Dead Ink appeared first on Anne Charnock.

January 2, 2023

My best reads of 2022

It’s always a pleasure to look back on the books I’ve read during the year to pinpoint my favourites. During 2022, I have to admit I read far fewer novels than usual. I devoted most of my reading time to research, and I will keep those non-fiction books under wraps for the time being. When choosing my fiction reading, as in the first half of 2022, I tended to pick novels that came highly recommended to me.

In June this year I posted my best books for the first half of the year while they were still fresh in my mind:

The Fell by Sarah Moss (Picador, 2021)

Intimacies by Katie Kitamura (Jonathan Cape, 2021)

To Paradise by Hanya Yanagihara (Picador 2022)

Double Blind by Edward St Aubyn (Harvill Secker, 2021)

News of the Dead by James Robertson (Hamish Hamilton, 2021)

Bird Summons by Leila Aboulela (W&N, 2019)

Case Study by Graeme Macrae Burnet (Saraband, 2021)

So, here are my stand-out reads for the second half of 2022.

Historical fiction, it often strikes me, has much in common with speculative fiction in terms of world building. Many aspects of historical worlds are known to us, and certain aspects of a future world seem easier to predict than others. But writers of historical and science fiction must apply themselves to filling in the gaps. This year, my favourite historical novel was Hamnet (Tinder Press, 2020) by Maggie O’Farrell — beautifully realised and richly detailed in depicting life during the closing years of the sixteenth century in Stratford-upon-Avon.

Historical fiction, it often strikes me, has much in common with speculative fiction in terms of world building. Many aspects of historical worlds are known to us, and certain aspects of a future world seem easier to predict than others. But writers of historical and science fiction must apply themselves to filling in the gaps. This year, my favourite historical novel was Hamnet (Tinder Press, 2020) by Maggie O’Farrell — beautifully realised and richly detailed in depicting life during the closing years of the sixteenth century in Stratford-upon-Avon.

One of the delights of my year was catching up with the novella Small Things Like These (Faber & Faber, 2021) by Claire Keegan. The story is tightly focussed on a coal merchant and his interaction with a convent and the Magdalene laundry run by the nuns. Keegan prompts the reader to ask what they themselves would do. Would the reader, in similar circumstances, fail in their lack of curiosity, turn a blind eye, or would they intervene?

One of the delights of my year was catching up with the novella Small Things Like These (Faber & Faber, 2021) by Claire Keegan. The story is tightly focussed on a coal merchant and his interaction with a convent and the Magdalene laundry run by the nuns. Keegan prompts the reader to ask what they themselves would do. Would the reader, in similar circumstances, fail in their lack of curiosity, turn a blind eye, or would they intervene?

There is little I can add to the praise for Sea of Tranquility (Picador, 2022) by Emily St John Mandel, but I can say that Mandel is now a must-read author for me. I saved this novel to read on holiday in the latter part of the year. It did not disappoint. Smart, fragmented, and intriguing from start to finish. Sea of Tranquility combines historical, contemporary and future settings. Wonderful.

There is little I can add to the praise for Sea of Tranquility (Picador, 2022) by Emily St John Mandel, but I can say that Mandel is now a must-read author for me. I saved this novel to read on holiday in the latter part of the year. It did not disappoint. Smart, fragmented, and intriguing from start to finish. Sea of Tranquility combines historical, contemporary and future settings. Wonderful.

Another novel combining past, present and future storylines is The Coral Bones (Unsung Stories, 2022) by E.J. Swift. I was fortunate to read this novel in manuscript. It’s an elegant novel — a beautifully crafted love letter to our endagered coral reefs, confirming Swift as a writer of compelling eco-fiction.

Another novel combining past, present and future storylines is The Coral Bones (Unsung Stories, 2022) by E.J. Swift. I was fortunate to read this novel in manuscript. It’s an elegant novel — a beautifully crafted love letter to our endagered coral reefs, confirming Swift as a writer of compelling eco-fiction.

I returned once again this year to Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale (Jonathan Cape, 1986) because I’m writing an essay about the influence of that novel on my own fiction. Though I have read The Handmaid’s Tale at least four times over the decades, I found new, startling resonances in the wake of Trumpism and the overturning of Roe versus Wade. It makes me wonder if I should return to more old favourites!

I returned once again this year to Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale (Jonathan Cape, 1986) because I’m writing an essay about the influence of that novel on my own fiction. Though I have read The Handmaid’s Tale at least four times over the decades, I found new, startling resonances in the wake of Trumpism and the overturning of Roe versus Wade. It makes me wonder if I should return to more old favourites!

Sandra Newman’s The Men (Granta, 2022) struck me as an equally confrontational feminist novel. I read it immediately after The Handmaid’s Tale. In Newman’s novel, all people with a Y chromosome — both young and old — disappear overnight. The author imagines a world run by women, prompting the reader to ask what would be gained and what would be lost. Equal parts utopia-dystopia-mystery-horror.

Sandra Newman’s The Men (Granta, 2022) struck me as an equally confrontational feminist novel. I read it immediately after The Handmaid’s Tale. In Newman’s novel, all people with a Y chromosome — both young and old — disappear overnight. The author imagines a world run by women, prompting the reader to ask what would be gained and what would be lost. Equal parts utopia-dystopia-mystery-horror.

I also enjoyed a relatively recent classic, Gilead (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2004) by Marilynne Robinson, which is a slow-burn novel about family, fathers and sons, religion and faith, a love of life in the face of approaching death, and the attempt to open one’s heart and set the record straight before it’s too late.

I also enjoyed a relatively recent classic, Gilead (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2004) by Marilynne Robinson, which is a slow-burn novel about family, fathers and sons, religion and faith, a love of life in the face of approaching death, and the attempt to open one’s heart and set the record straight before it’s too late.

All in all, I regard this as a solid ‘best of’ year’ list, even though I had fewer books to choose from.

I’m enjoying everyone else’s yearly round-ups, and my pile of books for the coming year is reaching the ceiling.

Happy reading in 2023, everyone!

The post My best reads of 2022 appeared first on Anne Charnock.

December 29, 2022

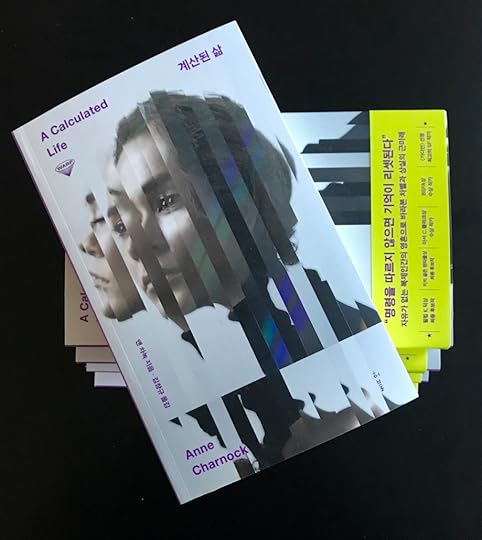

Korean edition: A Calculated Life

What a lovely end to my writing year! It’s been a year dominated by research and works-in-progress, so it’s wonderful to receive the gorgeous Korean edition of A Calculated Life.

This Korean edition is published by Hubble, an imprint of East-Asia Publishing Co. The translator is Kim Changgyu, an award-winning author, and the new edition is designed by Chung Myounghee.

Many, many thanks to everyone involved in producing this edition. How exciting to find new readers!

I hope to post my favourite reads since June 2022 fairly soon. My best reads of the first half of the year are posted here.

In the meantine, happy reading everyone!

The post Korean edition: A Calculated Life appeared first on Anne Charnock.

July 19, 2022

Amanat: Women’s Writing from Kazakhstan

Earlier this year I had the great pleasure to read this anthology in manuscript. This month AMANAT is published!

In the fall of 2018, the Kazakh writer Zira Naurzbayeva agreed to meet me, an English traveller and writer, to discuss her work of nonfiction “The Beskempir,” which I had read online though only in the form of an extract. Like many travellers, whenever I prepare for a journey I gather books of fiction and nonfiction set in each country on my route. However, in the case of Kazakhstan, I found it difficult to track down translations, especially translations of Kazakh women’s writing.

I contacted Zira through her translator, Shelley Fairweather-Vega, in the hope that by meeting Zira I might gain personal insights into a part of the world that was unfamiliar to me. Zira and I emailed back and forth, sometimes in English but also in Russian. I don’t speak Russian so I typed my messages into online translators, and kept my fingers crossed that in spite of our language incompatibility we would manage to make a real-world connection. A last-minute change to my complex train schedule might have scuppered our plans. My route took me from western Europe, through Belarus to Russia, and I entered Kazakhstan via the northern city of Petropavl, later travelling onwards to China.

Fortunately, we did meet on a Saturday afternoon at Astana’s National Library. Zira’s daughter, Hadisha, kindly came along to translate.

At the end of the afternoon, I came away emotionally wrecked. As a former journalist I have enjoyed the privilege of meeting many generous people willing to tell me about their lives, their family histories. But I had never met anyone with such a bewildering and traumatic family history as Zira’s. I believe the intensity of our conversation became heightened because Zira’s daughter acted as an innocent conduit for these appalling accounts of the past, which ended, more often than seemed plausible, in dispossession, famine and starvation. Their extended family history mirrored the gamut of Central Asia’s century of catastrophes: the loss of livelihoods during political upheavals and disastrous macro-economic interventions, the confiscations of livestock by the Red Army during the Russian Civil War, dispossession of land when the Bolsheviks pushed to collectivise farming, the destruction of the fishing industry at the Aral Sea. Not forgetting, the loss of good health following the Soviet nuclear testing programme in eastern Kazakhstan.

I also came away from our conversation wanting to know more. I craved more personal reflections on life in Kazakhstan whether those reflections took the form of essays, short stories or fictionalised autobiography, which I could read alongside the limited number of English-language travel guides. I wanted the authentic, insider stories, the authentic voices of women.

Here we have it, in Amanat: Women’s Writing from Kazakhstan. Edited by Shelley Fairweather-Vega and Zaure Batayeva. Published by independent press, Gaudy Boy.

At last, we can read “The Beskempir” unabridged in English for the first time.

One of the great pleasures in reading these works in translation is our encounter with Kazakh idioms. ‘Why hurry away as if you’ve come to borrow a matchstick?’ (“An Awkward Conversation”). ‘If I pulled one way, my bull would die, and if I pulled the other, my cart would break’ (“Hunger”). In the same story we read about a food vendor: “They have everything but bird’s milk.” And we meet a local dignitary described as a ‘big bird’ (“Romeo and Juliet”).

The reader gleans that the writers in Amanat are connected to a rural heritage even if their families had moved to the cities, away for the steppe and their villages half a century earlier. Indeed, the difficulties in transitioning from a rural life to an urban life is a key theme in Zira’s “The Beskempir.” It records the pressure on grandmothers to leave their auls, their village homes, and help their adult children in the city. An elderly woman sinks into despair having left her aul to live with her daughter in a soulless apartment block. In secret, the daughter sells the family house, and is allocated a larger apartment by coercing her mother to stay. The old woman stands at her window on the fifth floor, and howls.

Though western readers will be intrigued by the portrayal of life under state central control, enthralled by the unfamiliarity, the stories reveal the universal nature of everyday life. Children steal apples from an orchard (“The Orphan”), a woman suspects her husband is dreaming of a lost love (“An Awkward Conversation”), a family feud is sparked over the deathbed wish of their matriarch (“Amanat”), a mother waits for her son to return from war (“Aslan’s Bride”), a woman reflects, while cradling her child, on the deep connection she feels to her grandmothers (“My Eleusinian Mysteries”), and the pervasive love of traditional music (“The Rival,” “Weddings at the Medeu” and “The Anthropologists”).

We glean the impression through several accounts—whether fictional, factual or semi-autobiographical—that many adults in Kazakhstan have been raised in orphanages, and we learn of one particular orphanage ‘for children of enemies of the people,’ which stopped me in my tracks. Readers eavesdrop in “The Beskempir” on a group of elderly women who meet regularly in the writer’s family home, and who turn out to be former inmates of ‘Algeria,’ the nickname for the Akmolinsky Camp for Wives of Traitors to the Motherland. The so-called traitors were ‘repressed,’ often as a punishment for being captured by German forces during the Second World War.

In fact, the Second World War feels ever present in Amanat. “Aslan’s Bride” is the emotionally taut story of a mother waiting for her son to return from the war. Each year she pays the impoverished cobbler in her village to re-sole her son’s shoes in readiness for his return. The story seems to ask if it’s better to know the truth or live with hope. A particularly poignant story with a surprising revelation.

In the latter years of the Soviet Union, in an inflammatory move, Mikhail Gorbachev installed Gennady Kolbin as First Secretary of the Communist Party in Kazakhstan. Kolbin had no close connection to the country and his appointment sparked student riots in December 1986 in the Kazakh capital Astana (now Nur-Sultan). “The Black Snow of December” takes the reader to a newspaper office where a journalist is fearful he has landed himself in deep trouble by examining those student riots in a retrospective exposé.

I found myself drawn to stories in Amanat that reveal the impact of geopolitics on ordinary citizens. The internal collapse of the Soviet Union, beginning in 1991, led two years later to the dramatic overnight issue of a new currency by Kazakhstan’s then-president Nursultan Nazarbayev. In secret, the first banknotes were printed in the United Kingdom and the coins minted in Germany. And we see the immediate fall-out of this currency switch in “Hunger.” This portrays a young Kazakh woman studying literature in Moscow who finds she can no longer cash the money orders sent from her home in Almaty. Close to starvation she is forced to take any work she can find to survive. She recalls the phrase, ‘Wash a donkey’s ass, if you must, as long as you earn some money.’

A teenager claiming to be a refugee, finds herself in similar dire straits. She lives on her wits in the richly detailed story, “The Lighter.” Sheltering in the basement of a building under construction, she adopts a reckless strategy for tricking men out of money so she can feed herself and her young friends sharing this basement squat. Nevertheless, her outlook appears hopeful. She stands on the roof of the unfinished building, spellbound by the city sprawl below.

Those stories set in the present-day point to the challenge of corruption (“The School” and “Weddings at the Medeu”) and the clash of cultures as Kazakhstan has opened up to foreign workers, academics, aid workers and, I suppose, foreign travellers like me (“The Anthropologists” and “Precedent”). We glean that the undercurrents of ethnic tension are still present, and that a new generation remains caught up in the geopolitical tensions of the region, with young people yearning to see more of the world themselves.

Since my mind-shattering conversation with Zira Naurzbayeva and her daughter in 2018, Zira has ‘derussified’ her name on social media to Zira Nauryzbai, and she will publish under this name for future publications.

If you would like to read Amanat: Women’s Writing from Kazakhstan, it’s now available from a range of bookstores and websites or through the publisher Gaudy Boy. For anyone looking to understand the politics of Central Asia, Amanat is an excellent place to start.

The post Amanat: Women’s Writing from Kazakhstan appeared first on Anne Charnock.