Thomas D. Perry's Blog

March 21, 2020

Archibald Stuart And The Lee Land

Archibald Stuart And The Lee Brothers

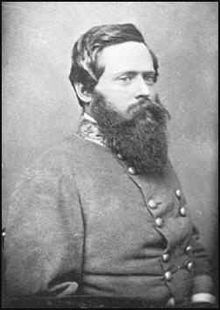

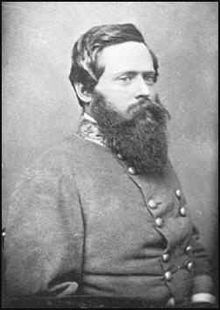

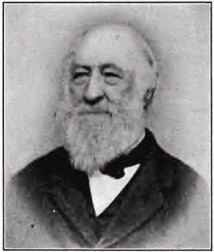

J. E. B. Stuart's Father Archibald

J. E. B. Stuart's Father Archibald

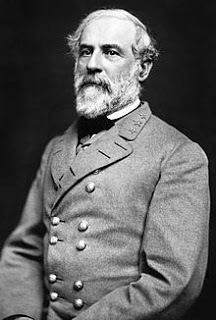

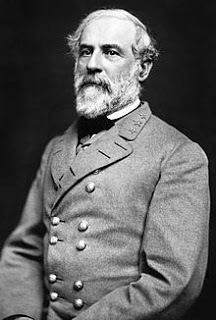

Robert E. Lee circa the time he wrote Archibald

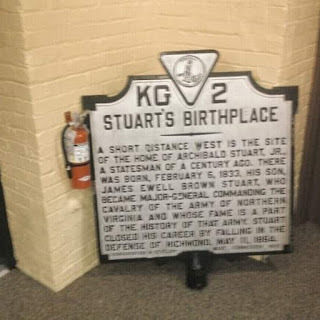

On November 24, 1836, Archibald Stuart received a letter from Robert E. Lee, an officer in the United States Army with a deed that Lee’s brother Charles Carter Lee wished passed on to Stuart, who acted as the Lee’s attorney in Patrick County. This is the first time the names of Stuart and Lee come together that I have found. Archibald Stuart’s son James Ewell Brown Stuart would make a name for himself as R. E. Lee’s cavalry commander during the War Between the States.

The story of the Lee land in Patrick County is an interesting one. After the Revolutionary War, Buffalo Mountain was a part of a 16,000-acre tract of land known as Lee’s Order. This tract was a grant made to General Henry Lee (1756-1818) by the United States for his service in the Revolutionary War. Henry Lee attended Princeton with the future president, James Madison, and served as a cavalry commander under George Washington during the American Revolution. Known for his swift movements and lightning attacks, he earned the moniker of “Light Horse Harry.” After the war, Lee served as Governor of Virginia, but land speculation led to a term in debtors’ prison and a wretched end for the man who said Washington was “First in War, first in peace and first in the hearts of his countrymen.”

Robert Edward Lee (1809-1870), known to history as the “Gray Fox,” commanded the Army of Northern Virginia during the War Between the States, but his brothers are lesser known. Sydney Smith Lee (1802-1869) married the granddaughter of “Founding Father” George Mason, the “Father of the Bill of Rights.” He was the father of “Jeb” Stuart’s subordinate Fitzhugh Lee. Sydney Lee served in the navies of the United States and the Confederate States of America. Beginning in 1820 with a midshipman’s commission in the United States Navy, he rose in rank serving as Commandant of the Naval Academy, commanding the Philadelphia Naval Yard, and accompanying Mathew Perry on his expedition to Japan. He commanded the Norfolk Navy Yard and the Confederate Naval Academy at Drewry’s Bluff during the war. Considered very handsome, his brothers nicknamed him “Rose.” After the war, he farmed in Stafford County, Virginia, before dying suddenly in July 1869.

Fitzhugh Lee, Son of Sydney Lee served under J. E. B. Stuart during the Civil War

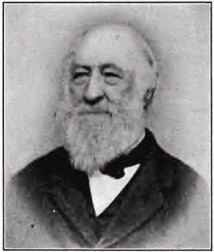

Robert E. Lee's brother Sydney Smith Lee, father of Fitzhugh Lee.

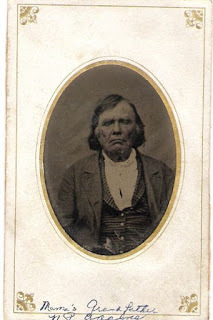

Charles Carter Lee was born in 1798, received a degree from Harvard in 1819. He lived a disjointed life as a New York City lawyer, land speculator, and plantation owner in Mississippi until his marriage at age 49 to Lucy Penn Taylor. He lived on his wife’s inheritance, Windsor Forest, in Powhatan County, Virginia, prospering as a husband, father, farmer, and writer, especially of poetry.

Of the three Lee brothers, only Carter lived on the land in Floyd County. Papers supplied from the courthouse indicate that Carter tried to establish a gristmill on the property and that he was involved in legal dealings with Archibald Stuart. Tradition states he lived on the Buffalo Mountain property at one time in a home called Spring Camp and that he had a law office. Carter was the last of Henry and Ann Lee’s children to die.

Charles Carter Lee, older brother of R. E. Lee.

After the death of their mother, Ann Hill Carter Lee, in 1829, the three Lee brothers inherited the property. There were unpaid taxes and bills against the property, but the brothers kept the land. In 1846, the brothers sold 16,300 acres in the three counties to Nathaniel Burwell of Roanoke County (Patrick County Deed Book #12 page 425) for $5,000. Surveyed initially as over 20,000 acres, the Patrick portion was 6,268 near Hog Mountain crossing branches of the south fork of Rock Castle Creek, the Conner Spur Road, and a fork of the Dan River. The Floyd portion was 7,143, and Carroll was 5,797 acres.

Anne Carter Lee, mother of the Lee brothers.

Robert E. Lee may have summed up the ownership of the land in southwest Virginia and the plight of the three brothers after the war when he said, “It’s a hard case that out of so much land, none should be good for anything.” Lee went on to command the Army of Northern Virginia, where his cavalry was commanded from June 1862 until May 12, 1864, by Archibald Stuart's son, James Ewell Brown "Jeb" Stuart.

Robert Edward Lee and his cavalry commander during the War Between The States, J. E. B. Stuart, who was born at the Laurel Hill Farm, Ararat, Patrick County, Virginia.

J. E. B. Stuart's Father Archibald

J. E. B. Stuart's Father Archibald

Robert E. Lee circa the time he wrote Archibald

On November 24, 1836, Archibald Stuart received a letter from Robert E. Lee, an officer in the United States Army with a deed that Lee’s brother Charles Carter Lee wished passed on to Stuart, who acted as the Lee’s attorney in Patrick County. This is the first time the names of Stuart and Lee come together that I have found. Archibald Stuart’s son James Ewell Brown Stuart would make a name for himself as R. E. Lee’s cavalry commander during the War Between the States.

The story of the Lee land in Patrick County is an interesting one. After the Revolutionary War, Buffalo Mountain was a part of a 16,000-acre tract of land known as Lee’s Order. This tract was a grant made to General Henry Lee (1756-1818) by the United States for his service in the Revolutionary War. Henry Lee attended Princeton with the future president, James Madison, and served as a cavalry commander under George Washington during the American Revolution. Known for his swift movements and lightning attacks, he earned the moniker of “Light Horse Harry.” After the war, Lee served as Governor of Virginia, but land speculation led to a term in debtors’ prison and a wretched end for the man who said Washington was “First in War, first in peace and first in the hearts of his countrymen.”

Robert Edward Lee (1809-1870), known to history as the “Gray Fox,” commanded the Army of Northern Virginia during the War Between the States, but his brothers are lesser known. Sydney Smith Lee (1802-1869) married the granddaughter of “Founding Father” George Mason, the “Father of the Bill of Rights.” He was the father of “Jeb” Stuart’s subordinate Fitzhugh Lee. Sydney Lee served in the navies of the United States and the Confederate States of America. Beginning in 1820 with a midshipman’s commission in the United States Navy, he rose in rank serving as Commandant of the Naval Academy, commanding the Philadelphia Naval Yard, and accompanying Mathew Perry on his expedition to Japan. He commanded the Norfolk Navy Yard and the Confederate Naval Academy at Drewry’s Bluff during the war. Considered very handsome, his brothers nicknamed him “Rose.” After the war, he farmed in Stafford County, Virginia, before dying suddenly in July 1869.

Fitzhugh Lee, Son of Sydney Lee served under J. E. B. Stuart during the Civil War

Robert E. Lee's brother Sydney Smith Lee, father of Fitzhugh Lee.

Charles Carter Lee was born in 1798, received a degree from Harvard in 1819. He lived a disjointed life as a New York City lawyer, land speculator, and plantation owner in Mississippi until his marriage at age 49 to Lucy Penn Taylor. He lived on his wife’s inheritance, Windsor Forest, in Powhatan County, Virginia, prospering as a husband, father, farmer, and writer, especially of poetry.

Of the three Lee brothers, only Carter lived on the land in Floyd County. Papers supplied from the courthouse indicate that Carter tried to establish a gristmill on the property and that he was involved in legal dealings with Archibald Stuart. Tradition states he lived on the Buffalo Mountain property at one time in a home called Spring Camp and that he had a law office. Carter was the last of Henry and Ann Lee’s children to die.

Charles Carter Lee, older brother of R. E. Lee.

After the death of their mother, Ann Hill Carter Lee, in 1829, the three Lee brothers inherited the property. There were unpaid taxes and bills against the property, but the brothers kept the land. In 1846, the brothers sold 16,300 acres in the three counties to Nathaniel Burwell of Roanoke County (Patrick County Deed Book #12 page 425) for $5,000. Surveyed initially as over 20,000 acres, the Patrick portion was 6,268 near Hog Mountain crossing branches of the south fork of Rock Castle Creek, the Conner Spur Road, and a fork of the Dan River. The Floyd portion was 7,143, and Carroll was 5,797 acres.

Anne Carter Lee, mother of the Lee brothers.

Robert E. Lee may have summed up the ownership of the land in southwest Virginia and the plight of the three brothers after the war when he said, “It’s a hard case that out of so much land, none should be good for anything.” Lee went on to command the Army of Northern Virginia, where his cavalry was commanded from June 1862 until May 12, 1864, by Archibald Stuart's son, James Ewell Brown "Jeb" Stuart.

Robert Edward Lee and his cavalry commander during the War Between The States, J. E. B. Stuart, who was born at the Laurel Hill Farm, Ararat, Patrick County, Virginia.

Published on March 21, 2020 12:41

March 14, 2020

Archibald Stuart Part One

J. E. B. Stuart's Father: Archibald Stuart (1795-1855) Part One

“His memory is cherished with an affection rarely equalled in the history of any public man."

-- H. B. McClellan

In the summer of 1855, he was fifty-nine years old. He looked back on a long life of public service as a soldier, attorney, delegate to two constitutional conventions, representative of Patrick County in both houses of the Virginia Legislature, and one term in the United States House of Representatives. He fathered eleven children with Elizabeth Letcher Pannill Stuart. He was the fifth richest man in Patrick County five years earlier, but most of it came from his wife’s inheritance because, like many people, Archibald Stuart had his shortcomings. He drank, gambled, loving the party, and the company of women. Archibald Stuart was alone and dying at Laurel Hill. He wrote his granddaughter, Mary Belle Peirce, that her grandmother, Elizabeth, was away from Laurel Hill caring for their daughter, Victoria. Alone at his home with his thoughts and his own mortality Archibald Stuart asked his granddaughter to please write to him.

George Washington was President of the United States when Archibald Stuart was born December 2, 1795, in Lynchburg, Virginia. As the son of Judge Alexander Stuart, the law came naturally to Archibald and, with that, politics as well. One biographer describes him this way. “His portrait shows a handsome face, high-bred, genial and ruddy with a bright eye and certain weakness about the mouth. He was a notable orator, famous on the hustings, admired in the legislative halls and exceedingly convivial. Old men relate that no gathering of gentlefolk in his section was complete without Arch Stuart, to tell the liveliest tales and trill songs in his golden voice, when the cloth was drawn and the bottle passed.”

After joining the legal bar in Campbell County, serving in an artillery unit during the War of 1812 from March 22 until August 22, 1813, Stuart served in Captain James D. Dunnington’s Artillery. Later, Stuart served as a sergeant from August 12, 1814, until January 26, 1815, in the 53rd Regiment of Virginia Militia, Campbell County’s Captain Adam Clements Troop of Cavalry. For this service, Stuart received eleven dollars a month along with forty cents a day for his horse for a total of $127.52 (1,116.80 in 2005 dollars per www.westegg.com/inflation).

In a Bounty Land Claim in the National Archives dated January 26, 1856, by Patrick County Justice of Peace J. C. Taylor and witnessed by Stuart’s neighbors Lewis and D. Floyd Pedigo, Stuart’s widow Elizabeth received 80 acres near Christiansburg, Kentucky in 1857 for his service in the War of 1812.

The land records show Archibald Stuart living in Campbell County, Virginia, on January 13, 1818. That same year, he returned to the ranks of the 23rd Troop of Cavalry after the resignation of Gabriel Scott.

Described in different sources as a “hell of a fellow,” Archibald Stuart married Elizabeth Letcher Pannill, a strict religious woman with “no special patience for nonsense,” in 1817. Eleven children followed born to the union over the next twenty years. The children were Ann born in 1818, Bethenia in 1819, Mary in 1821, David in 1823, William in 1826, John in 1828, Columbia in 1830, J. E. B. in 1833, an unnamed son who died in 1834, Virginia in 1836, and Victoria in 1838.

Stuart on May 10, 1818, defended a slave named Henry charged with leaving and setting fire to his master’s home. The following year a daughter, Bethenia, named for her maternal grandmother, was born at Seneca Hill in Campbell County. Archibald Stuart’s father Alexander owned 200 acres of land as early as 1796 on Seneca Creek in Campbell County that increased to 600 acres later. Archibald Stuart represented Campbell County in the Virginia House of Delegates (1819-1820). On December 1, 1828, Archibald Stuart cut his ties to Campbell County and sold his land there to his brother-in-law William L. Pannill. The transaction involved 1,070 acres for $1532.50.

Archibald and Elizabeth Letcher Pannill Stuart and her brother William Letcher Pannill worked out a land swap recorded in December 1828 where the sister received all the land in Patrick County for the land deeded her by her mother Bethenia in Pittsylvania County including 146 acres where the “Chalk Level store is situated.” Archibald and Elizabeth Stuart went to live in Patrick County.

The journey to Patrick County was not as seamless as it appears. There is evidence that Archibald Stuart “lost the family farm” in Campbell County. Many biographers of J. E. B. Stuart make passing mention of the financial problems Archibald Stuart dealt with most of his adult life.

Pere Louis-Hippolyte Gache, a Jesuit priest, and the former Chaplain 10th Louisiana Infantry, detailed to Danville Hospitals, where he met Mrs. Elizabeth Stuart during the Civil War in Danville in 1862, seven years after Archibald’s death. Gache wrote that Stuart lost his home, Seneca Hill, due to “compulsive” gambling. Gache continued that Archibald Stuart threw himself upon the mercy of his father, Judge Alexander Stuart, in Florissant, St. Louis County, Missouri. Elizabeth gave birth to her daughter Mary while in Missouri. After a short sojourn living in Missouri near his father, young Stuart returned to the “Old Dominion.”

Order Book #3 states that Archibald Stuart was in Patrick County by October 1823 and began to practice law. He paid taxes on three slaves, a horse and a “chariot” valued at $300 that year. The courthouse records show him present for the next thirty-two years. One can imagine Archibald Stuart in his one-person buggy and horse riding to court at Patrick County Court House as he began to make a life for his wife and children. He signed an account of G. Moore, the guardian of John Moore, in May 1825, along with signing as a commissioner on William Moore, deceased, with William Carter as administrator. Over the years, the amount of property owned by the Stuarts in Patrick County fluctuated from a high of 2169 acres in 1836 to the 1508.50 acres when sold in 1859. Archibald Stuart owned an additional 600 acres nearer the Blue Ridge Mountains on nearby Lovill’s Creek, but not contiguous to the property inherited through his wife. There were an additional 70 acres on Wolf Creek that remained in the family until 1876 seventeen years after Laurel Hill was sold.

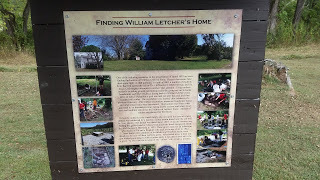

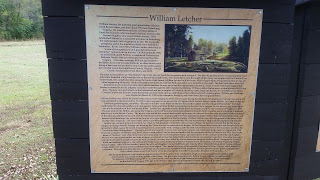

The Stuarts built the house at Laurel Hill in 1831 as the property tax record show that the county appraised $300 more in value for a “new house.” The little known about the house comes from biographies of J. E. B. Stuart with descriptions of the house as being a large comfortable house in a grove of oak trees with a beautiful flower garden and an excellent view of the Blue Ridge Mountains. Descriptions of cherry and pear trees near the home exist, and today a Royal Ming tree, not native to the area, still flourishes near the house site. No known photos or drawings of the home exist, which makes rebuilding it impossible. No plans ever existed to rebuild the home from the beginning of the fundraising project at Laurel Hill. It was going to be a park, not a reconstruction.

Next door, the home of Lewis and Sarah Pedigo and their many children brought many oral traditions about Laurel Hill to the present day. Carolyn Susan “Carrie Sue” Culler, whose grandmother knew the Stuart children, tells many interesting, but unverified stories. One of these states that Archibald Stuart taught law to several of the local boys in a log cabin, including the Pedigo sons and others such as Jack Reeves and George Duncan. Another tells of Victoria Stuart Boyden giving a picture and a hat to Mary Pedigo.

Stuart's political career progressed, as did life at Laurel Hill. Described as having an excellent speaking and singing voice, a good wit, Stuart had a gregarious personality that led him to be comfortable in public situations.

At noon on October 5, 1829, an older man rose to call the meeting to order in Richmond, Virginia. He stood in the Capital of Virginia, designed by his old friend Thomas Jefferson. The assembled ninety-eight men were to revise the 1776 Virginia Constitution, and as the elder statesman spoke, thirty-four-year-old Archibald Stuart no doubt marveled at the men around him.

Stuart found himself in the presence of several giants of Virginia and American History at the convention. The old man had once written, “If men were angels, no government would be necessary.” Standing before Archibald Stuart this day, he was one of the last “Founding Fathers,” and he spoke on constitutional matters as few could. Today we consider him the “Father” of the United States Constitution. James Madison, the former fourth President of the United States, still had seven years to live, and this day he nominated the former fifth President, James Monroe as President of the Convention. The Chief Justice of the United States, Virginian John Marshall, seconded the nomination. Madison, Marshall, and Monroe, who crossed the Delaware River with George Washington in 1776 were joined in the assembly by the infamous John Randolph of Roanoke and the future tenth President of the United States John Tyler, who lived long enough to be part of the government of the Confederate States of America. Stuart served as a Delegate to the Virginia Constitutional Convention from October 5, 1829, until January 15, 1830. Among other serving from the 21st Senatorial District were Joseph Martin of Henry County, Benjamin W. S. Cabell, and George Townes of Pittsylvania County.

The Convention of 1829-30 revised the 1776 Constitution of Virginia. Stuart served on a committee charged with the “Bill of Rights and matters not referred to foregoing Committees.” Described as a “reformer,” Stuart voted 80% of the time for a change in the constitution. He was one of only four delegates east of the Blue Ridge along with Henry A. Wise calling for a “white basis” in representation that challenged the authority of Piedmont plantation owners and increased the power of the western part of Virginia. While that measure failed along with a resolution on dueling, but an amendment passed to make removal of corrupt or incompetent judges “more efficient.” Stuart supported opening the right to vote to “leaseholders” not just property owners.

Although, as early as 1807, Patrick County called for a change in the Virginia Constitution, the county voted against having the convention in 1829 (400 to 95). There were 1,146 white males over sixteen, and 578 were qualified to vote. Only landowners held the suffrage. The county voted for the final constitution 274 to 246.

Described as a charmer, orator, advocate, a man of wit, humor, and a man of song, Stuart began representing Patrick County on December 6, 1830, until April 19, 1831, in the Virginia House of Delegates. Isaac Adams contested the election, and Stuart lost his seat.

Many counties in Southwest Virginia have evidence of Archibald Stuart’s legal career and his vices. In the Grayson County Law Order Book, officials indicted Stuart for gambling in a poker game. He pled guilty and paid a $2.00 fine. The Grayson County Order Books mention Stuart as early as August 1826 and in legal proceedings in 1833, 1835 and 1842. In 1842, he was a commissioner to choose a location and draw up a contract for the construction of the courthouse and jail in Carroll County, along with William Lindsey, Madison D. Carter, and Mahlon Scott. Henry County shows Archibald as early as 1827, receiving $10 for prosecuting a John Montgomery.

On March 1, 1831, Archibald Stuart took the oath as Commonwealth Attorney in Floyd County. A few days later, officials appointed Stuart to a commission to locate the county seat. Floyd County Attorney and Historian Gino Williams researched Archibald Stuart in Floyd County and supplied information, where Stuart was Commonwealth Attorney from September 20, 1831, until September 26, 1837, appointed by his brother in law Judge James Brown. Later Stuart replaced Jubal Early temporarily in the same position in March 1847. As late as December 1854, Stuart served on a committee “examining” the Clerk’s Office.

In December 1832, Judge Alexander Stuart returned to Virginia from Missouri and died in his native Augusta County. His will recorded in the General Court of Virginia is not available as it burned during the evacuation of Richmond in 1865. Either through mismanagement or the burden of his father’s estate, Archibald Stuart began to experience financial problems. As no copy of the will of Alexander, Stuart could be found, the precise reason is not known. Still, it is evident through the following recordings in the Patrick County Deed Books that Archibald Stuart carried his father’s estate for many years to come as collateral.

On June 8, 1835, Archibald sold 2000 acres of his father’s estate to Walker Merriweather in Lincoln County, Missouri. Four years later, on March 14, 1839, Archibald Stuart owed Chiswell Dabney $2000 “due in land” plus interest with four weeks’ notice at Patrick Court House over the estate of Alexander Stuart. Twenty-three slaves would go to J. E. Brown and John B. Dabney if Stuart did not pay. The slaves listed are Peter, Jack, Charles, Bob, Moses, Jefferson, Suckey, and children (Catharine, Lucy, John, Louisa, Charles, and infant) Celia and four children Henry, Suckey, David, Winney, and her children (Amy, Lavinia, Scott, and Jackson) On August 14, 1839, a Deed of Trust recorded on page 276 of Patrick County Deed Book #10 between Archibald Stuart, Madison Carter, and J. E. Brown states that Stuart is indebted to Brown for $1250.80 plus interest from September 24, 1832. Brown was responsible to Abram Staples for $615.09 as Staples and Stuart had a legal suit pending in Grayson County. The slaves involved in this transaction from Stuart to James Madison Carter included Peter, Jack, Bob, Moses, and Winney and children (Amy, Lavinia, Scott, and Jackson) for $1251.86 from Carter to Brown. The next day, August 15, 1839, the slaves listed on page 277 of Patrick County Deed Book #10 include Charles, age 40, Suckey, age 43, Jefferson age 19, Catharine age 17, Lucy age 15, John age 13, Louisa age 11, Charles Henry age 5 and Martha Jane age 3. This transaction states that Chiswell Dabney sold slaves in Missouri for $4480, along with slaves valued at $2000 in Virginia. Archibald Stuart received $4530 via Dabney.

Alexander Stuart transferred the property to Archibald in December 1828 with his recorded will on November 11, 1832. The Patrick County Deed Book #10 on page 255 lists a recording on September 12, 1835, with Archibald Stuart and Chiswell Dabney of Lynchburg acting as agents. The value listed as $939.14 included a library at $213.97, a law library at $162.75, furniture at $271.50, livestock at $237, including six cows at $12 each and schoolbooks at $6.92. Dabney was to receive property from the estate, and Stuart’s brother in law, J. E. Brown, held some of the property.

The exact cause of Archibald Stuart’s financial woes is unknown. The tradition in the biographies of his famous son J. E. B. Stuart are vague, dismissing his problems as a simple lack of business skill portraying Elizabeth Stuart as taking over the running of the Laurel Hill Farm, but the evidence points to other causes. From early in their marriage, there are rumors of a gambling problem. There were problems from the estate of Judge Alexander Stuart. Either or both of these wreaked havoc on the financial condition of the Stuarts at Laurel Hill. One fact that speaks volumes is the will of Bethenia Letcher Pannill recorded in Pittsylvania County Will Book #1 on page 507, which states clearly that her land is “not for the payment of Arch Stuart’s debts” and James Peirce will act as trustee for Elizabeth Letcher Pannill Stuart, not Archibald.

Chiswell Dabney, along with J. E. Brown, comes up in the transactions regarding Archibald Stuart often. Dabney, who lived near Lynchburg, was Arch Stuart’s maternal uncle. Chiswell’s brother John had a famous grandson also named Chiswell Dabney, who served as “Aide de camp” on J. E. B. Stuart’s staff from 1862 until 1863 during the Civil War. The many people in the Stuart family with Dabney as a middle name included Archibald’s sister, and son John Dabney Stuart denotes the importance of this relationship. Chiswell Dabney, who administered Judge Alexander Stuart’s Will, along with Judge Brown, allowed Archibald Stuart to survive the financial problems that plagued him throughout much of his adult life along with the inheritance from his father.

Patrick County, in 1833, the year J. E. B. Stuart was born, was “rural isolation.” The county seat called Taylorsville, named after a Revolutionary War figure George Taylor, but always referred to as Patrick Court House by the Stuart family, had forty homes, three taverns, two stores, a tailor shop, saddlery, tanyard, flour mill, and two tobacco factories. The Stuarts lived on the far western end of Patrick County in The Hollow or Ararat along the state line with North Carolina.

Excerpted from “The Dear Old Hills of Patrick:” J. E. B. Stuart and Patrick County Virginia by Thomas D. Perry.

“His memory is cherished with an affection rarely equalled in the history of any public man."

-- H. B. McClellan

In the summer of 1855, he was fifty-nine years old. He looked back on a long life of public service as a soldier, attorney, delegate to two constitutional conventions, representative of Patrick County in both houses of the Virginia Legislature, and one term in the United States House of Representatives. He fathered eleven children with Elizabeth Letcher Pannill Stuart. He was the fifth richest man in Patrick County five years earlier, but most of it came from his wife’s inheritance because, like many people, Archibald Stuart had his shortcomings. He drank, gambled, loving the party, and the company of women. Archibald Stuart was alone and dying at Laurel Hill. He wrote his granddaughter, Mary Belle Peirce, that her grandmother, Elizabeth, was away from Laurel Hill caring for their daughter, Victoria. Alone at his home with his thoughts and his own mortality Archibald Stuart asked his granddaughter to please write to him.

George Washington was President of the United States when Archibald Stuart was born December 2, 1795, in Lynchburg, Virginia. As the son of Judge Alexander Stuart, the law came naturally to Archibald and, with that, politics as well. One biographer describes him this way. “His portrait shows a handsome face, high-bred, genial and ruddy with a bright eye and certain weakness about the mouth. He was a notable orator, famous on the hustings, admired in the legislative halls and exceedingly convivial. Old men relate that no gathering of gentlefolk in his section was complete without Arch Stuart, to tell the liveliest tales and trill songs in his golden voice, when the cloth was drawn and the bottle passed.”

After joining the legal bar in Campbell County, serving in an artillery unit during the War of 1812 from March 22 until August 22, 1813, Stuart served in Captain James D. Dunnington’s Artillery. Later, Stuart served as a sergeant from August 12, 1814, until January 26, 1815, in the 53rd Regiment of Virginia Militia, Campbell County’s Captain Adam Clements Troop of Cavalry. For this service, Stuart received eleven dollars a month along with forty cents a day for his horse for a total of $127.52 (1,116.80 in 2005 dollars per www.westegg.com/inflation).

In a Bounty Land Claim in the National Archives dated January 26, 1856, by Patrick County Justice of Peace J. C. Taylor and witnessed by Stuart’s neighbors Lewis and D. Floyd Pedigo, Stuart’s widow Elizabeth received 80 acres near Christiansburg, Kentucky in 1857 for his service in the War of 1812.

The land records show Archibald Stuart living in Campbell County, Virginia, on January 13, 1818. That same year, he returned to the ranks of the 23rd Troop of Cavalry after the resignation of Gabriel Scott.

Described in different sources as a “hell of a fellow,” Archibald Stuart married Elizabeth Letcher Pannill, a strict religious woman with “no special patience for nonsense,” in 1817. Eleven children followed born to the union over the next twenty years. The children were Ann born in 1818, Bethenia in 1819, Mary in 1821, David in 1823, William in 1826, John in 1828, Columbia in 1830, J. E. B. in 1833, an unnamed son who died in 1834, Virginia in 1836, and Victoria in 1838.

Stuart on May 10, 1818, defended a slave named Henry charged with leaving and setting fire to his master’s home. The following year a daughter, Bethenia, named for her maternal grandmother, was born at Seneca Hill in Campbell County. Archibald Stuart’s father Alexander owned 200 acres of land as early as 1796 on Seneca Creek in Campbell County that increased to 600 acres later. Archibald Stuart represented Campbell County in the Virginia House of Delegates (1819-1820). On December 1, 1828, Archibald Stuart cut his ties to Campbell County and sold his land there to his brother-in-law William L. Pannill. The transaction involved 1,070 acres for $1532.50.

Archibald and Elizabeth Letcher Pannill Stuart and her brother William Letcher Pannill worked out a land swap recorded in December 1828 where the sister received all the land in Patrick County for the land deeded her by her mother Bethenia in Pittsylvania County including 146 acres where the “Chalk Level store is situated.” Archibald and Elizabeth Stuart went to live in Patrick County.

The journey to Patrick County was not as seamless as it appears. There is evidence that Archibald Stuart “lost the family farm” in Campbell County. Many biographers of J. E. B. Stuart make passing mention of the financial problems Archibald Stuart dealt with most of his adult life.

Pere Louis-Hippolyte Gache, a Jesuit priest, and the former Chaplain 10th Louisiana Infantry, detailed to Danville Hospitals, where he met Mrs. Elizabeth Stuart during the Civil War in Danville in 1862, seven years after Archibald’s death. Gache wrote that Stuart lost his home, Seneca Hill, due to “compulsive” gambling. Gache continued that Archibald Stuart threw himself upon the mercy of his father, Judge Alexander Stuart, in Florissant, St. Louis County, Missouri. Elizabeth gave birth to her daughter Mary while in Missouri. After a short sojourn living in Missouri near his father, young Stuart returned to the “Old Dominion.”

Order Book #3 states that Archibald Stuart was in Patrick County by October 1823 and began to practice law. He paid taxes on three slaves, a horse and a “chariot” valued at $300 that year. The courthouse records show him present for the next thirty-two years. One can imagine Archibald Stuart in his one-person buggy and horse riding to court at Patrick County Court House as he began to make a life for his wife and children. He signed an account of G. Moore, the guardian of John Moore, in May 1825, along with signing as a commissioner on William Moore, deceased, with William Carter as administrator. Over the years, the amount of property owned by the Stuarts in Patrick County fluctuated from a high of 2169 acres in 1836 to the 1508.50 acres when sold in 1859. Archibald Stuart owned an additional 600 acres nearer the Blue Ridge Mountains on nearby Lovill’s Creek, but not contiguous to the property inherited through his wife. There were an additional 70 acres on Wolf Creek that remained in the family until 1876 seventeen years after Laurel Hill was sold.

The Stuarts built the house at Laurel Hill in 1831 as the property tax record show that the county appraised $300 more in value for a “new house.” The little known about the house comes from biographies of J. E. B. Stuart with descriptions of the house as being a large comfortable house in a grove of oak trees with a beautiful flower garden and an excellent view of the Blue Ridge Mountains. Descriptions of cherry and pear trees near the home exist, and today a Royal Ming tree, not native to the area, still flourishes near the house site. No known photos or drawings of the home exist, which makes rebuilding it impossible. No plans ever existed to rebuild the home from the beginning of the fundraising project at Laurel Hill. It was going to be a park, not a reconstruction.

Next door, the home of Lewis and Sarah Pedigo and their many children brought many oral traditions about Laurel Hill to the present day. Carolyn Susan “Carrie Sue” Culler, whose grandmother knew the Stuart children, tells many interesting, but unverified stories. One of these states that Archibald Stuart taught law to several of the local boys in a log cabin, including the Pedigo sons and others such as Jack Reeves and George Duncan. Another tells of Victoria Stuart Boyden giving a picture and a hat to Mary Pedigo.

Stuart's political career progressed, as did life at Laurel Hill. Described as having an excellent speaking and singing voice, a good wit, Stuart had a gregarious personality that led him to be comfortable in public situations.

At noon on October 5, 1829, an older man rose to call the meeting to order in Richmond, Virginia. He stood in the Capital of Virginia, designed by his old friend Thomas Jefferson. The assembled ninety-eight men were to revise the 1776 Virginia Constitution, and as the elder statesman spoke, thirty-four-year-old Archibald Stuart no doubt marveled at the men around him.

Stuart found himself in the presence of several giants of Virginia and American History at the convention. The old man had once written, “If men were angels, no government would be necessary.” Standing before Archibald Stuart this day, he was one of the last “Founding Fathers,” and he spoke on constitutional matters as few could. Today we consider him the “Father” of the United States Constitution. James Madison, the former fourth President of the United States, still had seven years to live, and this day he nominated the former fifth President, James Monroe as President of the Convention. The Chief Justice of the United States, Virginian John Marshall, seconded the nomination. Madison, Marshall, and Monroe, who crossed the Delaware River with George Washington in 1776 were joined in the assembly by the infamous John Randolph of Roanoke and the future tenth President of the United States John Tyler, who lived long enough to be part of the government of the Confederate States of America. Stuart served as a Delegate to the Virginia Constitutional Convention from October 5, 1829, until January 15, 1830. Among other serving from the 21st Senatorial District were Joseph Martin of Henry County, Benjamin W. S. Cabell, and George Townes of Pittsylvania County.

The Convention of 1829-30 revised the 1776 Constitution of Virginia. Stuart served on a committee charged with the “Bill of Rights and matters not referred to foregoing Committees.” Described as a “reformer,” Stuart voted 80% of the time for a change in the constitution. He was one of only four delegates east of the Blue Ridge along with Henry A. Wise calling for a “white basis” in representation that challenged the authority of Piedmont plantation owners and increased the power of the western part of Virginia. While that measure failed along with a resolution on dueling, but an amendment passed to make removal of corrupt or incompetent judges “more efficient.” Stuart supported opening the right to vote to “leaseholders” not just property owners.

Although, as early as 1807, Patrick County called for a change in the Virginia Constitution, the county voted against having the convention in 1829 (400 to 95). There were 1,146 white males over sixteen, and 578 were qualified to vote. Only landowners held the suffrage. The county voted for the final constitution 274 to 246.

Described as a charmer, orator, advocate, a man of wit, humor, and a man of song, Stuart began representing Patrick County on December 6, 1830, until April 19, 1831, in the Virginia House of Delegates. Isaac Adams contested the election, and Stuart lost his seat.

Many counties in Southwest Virginia have evidence of Archibald Stuart’s legal career and his vices. In the Grayson County Law Order Book, officials indicted Stuart for gambling in a poker game. He pled guilty and paid a $2.00 fine. The Grayson County Order Books mention Stuart as early as August 1826 and in legal proceedings in 1833, 1835 and 1842. In 1842, he was a commissioner to choose a location and draw up a contract for the construction of the courthouse and jail in Carroll County, along with William Lindsey, Madison D. Carter, and Mahlon Scott. Henry County shows Archibald as early as 1827, receiving $10 for prosecuting a John Montgomery.

On March 1, 1831, Archibald Stuart took the oath as Commonwealth Attorney in Floyd County. A few days later, officials appointed Stuart to a commission to locate the county seat. Floyd County Attorney and Historian Gino Williams researched Archibald Stuart in Floyd County and supplied information, where Stuart was Commonwealth Attorney from September 20, 1831, until September 26, 1837, appointed by his brother in law Judge James Brown. Later Stuart replaced Jubal Early temporarily in the same position in March 1847. As late as December 1854, Stuart served on a committee “examining” the Clerk’s Office.

In December 1832, Judge Alexander Stuart returned to Virginia from Missouri and died in his native Augusta County. His will recorded in the General Court of Virginia is not available as it burned during the evacuation of Richmond in 1865. Either through mismanagement or the burden of his father’s estate, Archibald Stuart began to experience financial problems. As no copy of the will of Alexander, Stuart could be found, the precise reason is not known. Still, it is evident through the following recordings in the Patrick County Deed Books that Archibald Stuart carried his father’s estate for many years to come as collateral.

On June 8, 1835, Archibald sold 2000 acres of his father’s estate to Walker Merriweather in Lincoln County, Missouri. Four years later, on March 14, 1839, Archibald Stuart owed Chiswell Dabney $2000 “due in land” plus interest with four weeks’ notice at Patrick Court House over the estate of Alexander Stuart. Twenty-three slaves would go to J. E. Brown and John B. Dabney if Stuart did not pay. The slaves listed are Peter, Jack, Charles, Bob, Moses, Jefferson, Suckey, and children (Catharine, Lucy, John, Louisa, Charles, and infant) Celia and four children Henry, Suckey, David, Winney, and her children (Amy, Lavinia, Scott, and Jackson) On August 14, 1839, a Deed of Trust recorded on page 276 of Patrick County Deed Book #10 between Archibald Stuart, Madison Carter, and J. E. Brown states that Stuart is indebted to Brown for $1250.80 plus interest from September 24, 1832. Brown was responsible to Abram Staples for $615.09 as Staples and Stuart had a legal suit pending in Grayson County. The slaves involved in this transaction from Stuart to James Madison Carter included Peter, Jack, Bob, Moses, and Winney and children (Amy, Lavinia, Scott, and Jackson) for $1251.86 from Carter to Brown. The next day, August 15, 1839, the slaves listed on page 277 of Patrick County Deed Book #10 include Charles, age 40, Suckey, age 43, Jefferson age 19, Catharine age 17, Lucy age 15, John age 13, Louisa age 11, Charles Henry age 5 and Martha Jane age 3. This transaction states that Chiswell Dabney sold slaves in Missouri for $4480, along with slaves valued at $2000 in Virginia. Archibald Stuart received $4530 via Dabney.

Alexander Stuart transferred the property to Archibald in December 1828 with his recorded will on November 11, 1832. The Patrick County Deed Book #10 on page 255 lists a recording on September 12, 1835, with Archibald Stuart and Chiswell Dabney of Lynchburg acting as agents. The value listed as $939.14 included a library at $213.97, a law library at $162.75, furniture at $271.50, livestock at $237, including six cows at $12 each and schoolbooks at $6.92. Dabney was to receive property from the estate, and Stuart’s brother in law, J. E. Brown, held some of the property.

The exact cause of Archibald Stuart’s financial woes is unknown. The tradition in the biographies of his famous son J. E. B. Stuart are vague, dismissing his problems as a simple lack of business skill portraying Elizabeth Stuart as taking over the running of the Laurel Hill Farm, but the evidence points to other causes. From early in their marriage, there are rumors of a gambling problem. There were problems from the estate of Judge Alexander Stuart. Either or both of these wreaked havoc on the financial condition of the Stuarts at Laurel Hill. One fact that speaks volumes is the will of Bethenia Letcher Pannill recorded in Pittsylvania County Will Book #1 on page 507, which states clearly that her land is “not for the payment of Arch Stuart’s debts” and James Peirce will act as trustee for Elizabeth Letcher Pannill Stuart, not Archibald.

Chiswell Dabney, along with J. E. Brown, comes up in the transactions regarding Archibald Stuart often. Dabney, who lived near Lynchburg, was Arch Stuart’s maternal uncle. Chiswell’s brother John had a famous grandson also named Chiswell Dabney, who served as “Aide de camp” on J. E. B. Stuart’s staff from 1862 until 1863 during the Civil War. The many people in the Stuart family with Dabney as a middle name included Archibald’s sister, and son John Dabney Stuart denotes the importance of this relationship. Chiswell Dabney, who administered Judge Alexander Stuart’s Will, along with Judge Brown, allowed Archibald Stuart to survive the financial problems that plagued him throughout much of his adult life along with the inheritance from his father.

Patrick County, in 1833, the year J. E. B. Stuart was born, was “rural isolation.” The county seat called Taylorsville, named after a Revolutionary War figure George Taylor, but always referred to as Patrick Court House by the Stuart family, had forty homes, three taverns, two stores, a tailor shop, saddlery, tanyard, flour mill, and two tobacco factories. The Stuarts lived on the far western end of Patrick County in The Hollow or Ararat along the state line with North Carolina.

Excerpted from “The Dear Old Hills of Patrick:” J. E. B. Stuart and Patrick County Virginia by Thomas D. Perry.

Published on March 14, 2020 06:57

March 8, 2020

Elizabeth Perkins Letcher And Her Daughter, Bethenia Letcher Pannill

J. E. B. Stuart Mural at Patrick County High School

Elizabeth Perkins Letcher And Her Daughter, Bethenia Letcher Pannill

In September 1852, a couple walked together through the boxwoods and cedar trees of Beaver Creek Plantation in Henry County, Virginia. The pleasant day included a hunt for blackberries and spending time near the cooling waters of a nearby spring, where the young man tried to impress her with watery exploits and her playing the piano while he secreted himself out of sight to listen. As the sun sank, in the west, they sat in the grass while nearby a rooster caused a spectacle chasing fireflies. The voices of many slaves raised in song returning from the fields came to the ears of the young people reflecting on why “the caged bird sings.” He told her in a later letter that thinking of the day that it would “revive in my heart unfading recollections of the joy I experienced during that visit. I will never forget it.” Nearby the graves told the story of their shared family history. They shared a common ancestor, his great-grandmother, and her grandmother for Elizabeth Perkins “Bettie” Hairston and James Ewell Brown Stuart descended from Elizabeth Perkins Letcher Hairston.

After the death of William Letcher, the romantic and family tradition holds that George Hairston led troops into The Hollow, captured Nichols, the assassin of William Letcher, gave him a drumhead trial, and hung him. The area for years went by the name of Drumhead, including the letters written by J. E. B. Stuart. The author believes the Stuart family associated the area near William Letcher’s grave with the tradition that the murderers of the former after capture succumbed to execution by hanging after receiving the justice of a drumhead court-martial. Laurel Hill became synonymous with the area on the bluff above the river where Archibald and Elizabeth Stuart built their home and where their son James Ewell Brown Stuart was born.

George Hairston carried Elizabeth Perkins Letcher and her baby, Bethenia, to the Hairston home, Marrowbone, in Henry County. As this was several day's journey with overnight stops and no chaperone. Honor caused George to propose marriage to the wife of his friend rather than sully her reputation. George Hairston married Elizabeth Perkins Letcher on January 1, 1781. Family tradition tells he gave her two Chickasaw ponies and buckskin saddle heavily embroidered as a wedding gift. The newly married couple rode to their home at George Hairston’s house, Beaver Creek, just north of Martinsville in Henry County, Virginia, with a groomsman carrying baby Bethenia.

George Hairston described as a man of “great firmness of character combined with elegance of manner and appearance,” began his house along with the land between Beaver and Matrimony Creeks in 1776. It burned after his death, and his son Marshall rebuilt the present structure in 1837. George gave Henry County fifty acres that, along with much of downtown Martinsville includes the site of the old courthouse.

The marriage of George and Elizabeth Perkins Letcher Hairston produced twelve children beginning with Robert in 1783 followed by George in 1784, Harden in 1786, Samuel in 1788, Nicholas Perkins in 1791, Henry in 1793, Peter in 1796, Constantine in 1797, John Adams in 1799, America in 1801, Marshall in 1802 and Ruth Stovall Hairston in 1804.

George Hairston did not forget the friend, William Letcher, he lost during the American Revolution, and family tradition points to the warm feelings he held for his stepdaughter, Bethenia Letcher. Exhaustive searches of multiple county land records in Virginia did not reveal ownership by William Letcher of Laurel Hill. In 1790, John Marr purchased the 2,816-acre tract that included Laurel Hill and two years later conveyed 550 acres to William Letcher’s daughter, who was still a minor, for five hundred pounds. Hairston and Marr had a business relationship dealing in land speculation, including the “Iron Works Tract” that today encompasses Fairy Stone State Park. Six years later, the property was appraised at $1.75 an acre for a total of $962.50. Hairston paid the taxes on the land until Bethenia’s marriage. George lived on until March 7, 1827.

Elizabeth Perkins Letcher Hairston died on January 7, 1818. Bethenia Letcher married David Pannill on October 29, 1798. On her wedding day, tradition holds that Bethenia Letcher, “a very beautiful woman,” wore white plumes in her hair, but an ill omen of a black spot marred the nuptials. The groom cut the place out, but his wedding gift to his bride of a new carriage along with two horses burned up in a stable fire within days. The couple settled in Pittsylvania County at Chalk Level east of Chatham, Virginia.

On January 4, 1801, Bethenia gave birth to her first child, a daughter she named Elizabeth Letcher Pannill. The second child, William Letcher Pannill, came into this world on September 10, 1803, just months before his father’s death. David Pannill died in November 1803, leaving a wife and two small children. His tombstone reads, “He had a warm, generous heart, was just to all men and died among many friends who sincerely regretted the death of their best friend and benefactor.” Bethenia found herself in the same situation as her mother over twenty years earlier.

William Letcher Pannill married his cousin Maria Bruce Banks on December 22, 1831, and produced fifteen children. William’s descendants became prominent founding Pannill Knitting Company, and their generosity helped preserve Laurel Hill.

Bethenia gave Chalk Level to her son and moved into a nearby home called Whitehorne in 1839. Bethenia Letcher Pannill died on February 23, 1845. Her will divided the Patrick County land between her children. David and Bethenia Pannill lie together in the Chatham town cemetery with a marker noting their relationship to their famous grandson, James Ewell Brown “Jeb” Stuart, who was born at Laurel Hill.

Published on March 08, 2020 10:26

March 1, 2020

The Assasination Of William Letcher

William Letcher’s daughter was born on March 21, 1780. Elizabeth Perkins Letcher gave birth to her first child, Bethenia. This small child became the connection that led to her famous grandson's birth at Laurel Hill over fifty years later. That same year the American Revolution would come to Laurel Hill with tragic consequences.Bethenia’s daughter, Elizabeth Letcher Pannill Stuart, wrote of William Letcher at this time that, “He had the promise of long years of happiness and usefulness and domestic felicity, but a serpent lurked in his path, for whom he felt too great a contempt to take any precautions.” The clouds of war reached the home of William and Elizabeth Letcher that summer with tragic results in the form of Tories, those loyal to the British. John Adams said of the Tories, “A Tory here is the most despicable animal in the creation. Spiders, toads, snakes are their only proper emblems.”The same day Bethenia was born, Virginia Governor Thomas Jefferson wrote to Colonel William Preston in Montgomery County, stating, “I am sorry to hear that there are persons in your quarters so far discontented with the present government as to combine with its enemies to destroy it.” It was four years since this famous Virginian had penned the words of The Declaration of Independence. On March 29, the British began a siege of Charleston, South Carolina, resulting in the surrender of the city on May 12, 1780. This marked a change in British strategy to a southern front. Up to this time, the opposing armies fought most of the battles in the corridor between Philadelphia and Boston. It was the time of Banastre Tarleton for the British and Francis Marion “The Swamp Fox” for the Whigs or Patriots. On May 29, Tarleton defeated and then massacred the Patriots under Colonel Abraham Buford at the Waxhaws in South Carolina. Tarleton refused to accept the surrender of the men and killed or wounded 300. Four days later, General Henry Clinton, the Britishcommander in America, issued a proclamation saying, “Anyone not actively in support of the Royal government belonged to the enemy and was outside the protection of British law.”With the presence of a large army in the region, the Tories began an aggressive campaign against Patriot groups. Historians estimate the population evenly divided over the cause of independence with one-third in favor, one-third indifferent and one-third pro-British. Political, religious, and even personal feelings directed the decisions of those involved and made for a volatile situation.Lord Charles Cornwallis commander of the British commented on it this way, “In a civil war there is no admitting of neutral characters and those who are not clearly with us must be so far considered against us, as to be disarmed, and every measure taken to prevent their being able to do mischief.” Cornwallis’ opponent in the Southern Campaign, Nathaniel Greene, said, “The whole country is in danger of being laid waste by the Whigs and Tories who pursue each other with as much relentless fury as beasts of prey.” One participant summed up this civil war within the American Revolution in the following statement, “The virtue of humanity was totally forgot.” Documentation about Tory activity in the region exists. The Moravian settlers in nearby Forsyth County, North Carolina, often speak of them in their diaries. Today, Tory Creek, in nearby Laurel Fork on the Blue Ridge, holds to be a traditional hiding place for those loyal to the Crown. One revolutionary war soldier, James Boyd, who served in Captain James Gidens militia from Surry County, North Carolina, stated in his pension application details about the hangings of Joseph Burks, Mark Adkins, Adam Short, William Kroll (Koil) and James Roberts for being Tories. Tradition holds that William Letcher was a leader among the local people in support of the patriot cause and separation from Great Britain. Letcher left no doubt about his feelings, and this made him a target. As a member of the local militia, he may have been involved in several small battles against the pro-British sympathizers in the region. There is no evidence that Letcher took part in any major campaigns with the Continental Army or was ever a member of a mainline military unit. His granddaughter wrote of him, “He was very active in hunting them from their hiding places. He would frequently go alone, armed only with a shotgun, into the most inaccessible recesses of the mountains, exploring every hiding place…he knew it was for the Tories, who concealed themselves in the daytime but came forth in darkness and secrecy… William Letcher had proclaimed that he would lay down his life before one of them should lay a finger on his property. Hall used this remark to incite the Tories against him; reporting also his known enmity and activity in hunting them down, and representing their property as unsafe so long as William Letcher lived.” William Hall lived in Surry County, North Carolina, south of Letcher along the Ararat River. John Letcher mentions Hall's home, a meeting place for Tories, in the 1856 letter about Letcher.J. E. B. Stuart’s mother continued her narrative about her grandfather. Late one night, the Tories disguised as “fiends” burned Letcher’s smokehousefull of meat. Awakened by the fire and smell, Letcher scattered them with gunfire. One of the Tories reportedly replied from the darkness, “I am Hell-Fire Dick. You will see me again.” Letcher oblivious to the danger continued a normal life as a farmer with his wife, newborn daughter, and slaves.Oral tradition abounds today in Patrick County about the death of William Letcher. One version has Letcher shot from a nearby ridge while stepping out onto his porch. Another has him shot through a window of his home by a coward lurking outside at night. The most romantic and accepted story tells that Letcher was in his fields on August 2, 1780, when a stranger came to the house and asked Elizabeth Letcher about her husband’s whereabouts. She replied that he would be back shortly and invited the visitor to stay. When Letcher entered, the man identified himself as Nichols, a local Tory leader, and said, “I demand you in the name of His Majesty.” Letcher replied, “What do you mean?” Nichols shot Letcher. The Tory fled the home leaving the dying Patriot in the arms of his wife, his last words reportedly being, “Hall is responsible for this.” Hall fled towards Kentucky, but Indians along the Holston River killed his entire family. William Nichols, born in Granville County, today’s Orange County, North Carolina, about 1750, married Sarah Riddle in 1770, the daughter of Colonel James Riddle, a prominent Surry County Tory. Nichols is listed in the 1771 tax list of Surry County and served in the local militia for the Patriot cause, but received harsh treatment for “bad conduct” and swore to seek revenge after he was discharged. Letcher was his first victim. Reaction to Letcher’s death was immediate. On August 6, Colonel Walter Crockett in Wythe County believing the murderers were “Meeks and Nicholas…assembled 250 men at Fort Chiswell and was about to march against the Tories on the New River. He reported that one Letcher had been murdered...it is generally believed a large body of those wretches are collected in The Hollow.” The death of Letcher so stirred up the area that they hung the Tories “like dogs,” including a group hanging in nearby Mount Airy, North Carolina. When the wives of the doomed men “cried and lamented the fate of their husbands,” they were “well whipped for sorrowing for a set of rogues and murderers.”Colonel William Preston in Montgomery County wrote Governor Jefferson on August 8 stating, “A most horrid Conspiracy amongst the Tories in this Country being providently discovered about ten Days ago obliged me Not only to raise the militia of the County but to call for so large a Number from the Counties of Washington and Botetourt that there are upwards of four hundred men now on Duty exclusive of a Party which I hear Colonel Lynch marched from Bedford.” Another pensioner, William Carter, speaks of “a great excitement was produced by the murder of a distinguished Whig, William Letcher, who was shot down in his own house by a Tory in the upper end of Henry County. Captain Eliphas Shelton commanded a company of militia in which Carter was a sergeant. Ordered by his captain to summon a portion of the company to go in pursuit of the murderer, he rode all night, collected twenty or thirty men early the next morning, and pushed for the scene of the murder. The murderer and the Tories with whom he was connected had fled to the mountains where the detachments pursued them but failed in overtaking them and returned home after an absence of a week or more. He had scarcely returned home when the Tories returned to the same neighborhood and committed a good many robberies.”James Boyd’s pension applications states that Nichols and others murdered Letcher. Militia companies, including those of Shelton, Lyon, and Carlin of Virginia and Gidens of North Carolina combined to make a force of over 200 men. He continues that Captain Gidens captured Nichols within two weeks, but mentions that it was at Eutaw Springs, a battle that occurred on September 8, 1781, in South Carolina. Another account tells of “nine prisoners were captured, and on our return, two Nichols and Riddle out of the nine were hung…Tories Nichols and Riddle were hung in consequence of it appearing that they had been concerned with robbing a house.” This account mentions that they were involved in robbing a house of “one Letcher murdered by Meeks and Nichols.” Whenever Patriots captured William Nichols tradition holds, they hung him in chains and left him unburied. His motive for killing Letcher was in a letter found on his person after execution from the British offering a reward for every Patriot he murdered. On August 16, 1780, Cornwallis defeated Patriot General Horatio Gates at the Battle of Camden, South Carolina, and by the end of September, the British moved into that “nest of hornets” known today as Charlotte, North Carolina. The cause Letcher gave his life for rebounded with Patriot victories at King’s Mountain on October 7 and a week later at the Shallow Ford of the Yadkin River. In 1781, Virginian Daniel Morgan crushed Banastre Tarleton at the Battle of Cowpens on January 17. Nathaniel Greene lost to Cornwallis at the Battle of Guilford Court House on March 15, where Major Alexander Stuart fought. The road to Yorktown opened, andthe surrender of Cornwallis to George Washington came on October 19, 1781, resulting in a victory for the United States of America, a little more than a year later with the signing of a peace treaty on November 30, 1782.Over the years, this author often imagined a young man standing in front of the grave with eyes down reading the inscription and then slowly raising his head to view the bottomland along the river. The land full of the life of growing crops with the mountains shaded by the blue mist filled him with pride. He had grown from this very soil, and it was here that he always called home. The young army officer’s uniform was blue, and the summer sun reflected off the polished buttons. He placed his hat with the large dark plume on his head, saluted, and turned to mount his horse. He galloped off to splash through the river and up the hill to the site of his birth, his waiting family, and his destiny. It was the summer of 1859, andFirst Lieutenant James Ewell Brown Stuart of the First United States Cavalry was home for the last time. The white marble stone from a Richmond stonecutter, William Mountjoy, from the corner of Main and Eight Streets and placed by his maternal grandmother before her death in 1845, marked the grave of her father. As I write this, the graveis the only piece of the history from the Stuart Family that the young man would recognize if he came back today.Today, William Letcher rests in the bottomlands along the Ararat River in Patrick County’s oldest marked grave. His tombstone placed by his daughter before her death in 1845 says the following. “In memory of William Letcher, who was assassinated in his own house in the bosom of his family by a Tory of the Revolution, on the 2nd day of August 1780, age about 30 years. May the tear of sympathy fall upon the couch of the brave.”We should not lose sight of the irony of William Letcher’s great-grandson losing his life eighty-four years later at nearly the same age fighting for what he believed was a second American Revolution.While it might be a stretch to say that Letcher’s life and example led J. E. B. Stuart to a life in the military, it would not be hard to imagine a young man’s fascination with brave ancestor fighting and dying for something he believed in. This strong influence inculcated a strong love of home and a heroic legend he must live up to. You might even say Stuart gave his life defending the legacy William Letcher left him.

Published on March 01, 2020 03:17

February 27, 2020

The Strange Case of Not Adams

This time of year, I decompress and concentrate on writing my next book projects. One of them has been percolating in my mind for many years and it involves The Strange Case of Not Adams. Sometimes you find a new writing project when researching another. As usual J. E. B Stuart leads me to many other topics. On September 11, 2001, I was in the Library of Virginia doing research on Civil War General James Ewell Brown “Jeb” Stuart in the Special Collections Department. Governor John Letcher was a cousin of Stuart and I was looking through Letcher’s papers. I did not know about the terrorist attacks until noon when I came up for air upon hearing two of the staff discussing it. I came across this entry in Virginia’s Civil War Governor’s papers. “An important function of the governor was issuing reprieves and pardons. Copies of court cases, clippings, petitions, and correspondence supplement the pardons. All the pardon papers are filed separately in the chronological series at the end of each month. One significant pardon involved the case of Notley P. Adams of Patrick County who was charged with arson. Letcher pardoned Adams in December 1863, after he served three years in the penitentiary. A map of the area in Patrick County where the crime was committed is included in the papers. The governor also received and issued proclamations and requisitions regarding escaped convicts and fugitives.” I had never heard of Notley P. Adams before that day, so I requested to see the materials. They arrived in three large folders including over four hundred individual sheets documenting the pardon request by Adams to Governor Letcher. Since that time twenty years ago, the Library of Virginia has microfilmed the whole collection and you can scan the documents to pdf files and that is what I did in the fall of 2019. That has led to this book with easier access to this case about my home county of Patrick in far southwest Virginia. In Virginia, Patrick County likes to put biblical names on places. Ararat for the “Mountains of Ararat,” where Noah’s Ark landed in the book of Genesis in the Old Testament. The Dan River comes from Dan, the fifth son of Jacob, which is related to judgement. Dan was the founder of the Tribe of Dan, the second largest tribe of Israelites. Among his descendants was Samson. The community of Meadows of Dan in Patrick County applies a romantic name to the land drained by the Dan River. Just before the War Between The States erupted in 1861, one man was accused of arson. In April 1859, Notley Price Adams was accused of burning of the vacant home of Jefferson T. Lawson near the Patrick and Floyd county lines near the Dan River and the Laurel Fork. Local tradition says Notley Price Adams stood before the judge and was asked to state his name. “Not Adams” he replied. The aggravated judge said, “Well, then who are you,” which he heard again, “Not Adams.” The exasperated judge stated, “Well, if you are not Adams, who are you?” The question reverberates down to us today. This book tells the story of Adams and the times he lived in Patrick County, Virginia, where the more things change, the more they stay the same. When a small clique of people in the county seat try to destroy a man using trumped up evidence to convict him of a crime. This story is set in the War Between The States when Virginia tried to leave the Union. Patrick County was going to leave Virginia if it did not secede and become The Free State of Patrick.

Published on February 27, 2020 05:07

February 26, 2020

Remarks at Danube Presbyterian Church May 20, 2007

Let me begin by thanking the congregation of Danube Presbyterian Church and especially Reverend Fred Gilley for inviting Kenny and myself to come to speak about our region’s history. Looking about this room, I think I know almost everyone here from Ethel Cox and her three beautiful daughters, who used to baby-sit me. Some baby uh Ethel? It is good to see Mildred and Charles Hill, whose father we will talk about, and Verna Anderson, who I have shared some fun historical things over the years. I see Diana Goad, who I use to work with and young Wes Burkhart, just in from college, whose parent’s I went to high school with.

Today as we sit on the banks of one of Patrick County’s great rivers, I will speak to you today about the geography, specifically the route of the Mount Airyand Eastern Railway, “The Dinky” and some human interest stories about the train. Kenney will speak about the chronological history of the railroad and what it did in Kibler Valley.

We are into biblical names for our rivers in Patrick County. The railroad traveled the distance between the Dan named for a tribe of Israel to the Ararat, where Noah’s Ark landed on the mountains of. The Ararat River travels from BellSpur Churchin Patrick Countyto Siloam, North Carolina.

The railroad began on Riverside Drivenear present day Cross Creek Apparel. I use to work there in the dye house when I got out of college on third shift. Like the railroad, the textile mills will soon be gone as well. I have twelve web pages built about the railroad, and at the beginning, I found out the local genealogists Esther Johnson grew up there at the beginning of the railroad, and she wrote about it.

The Mount Airyand Eastern traversed 19.50 miles to Kibler Valley. The present day railroad tracks used to go to the North Carolina Granite Corporation. The narrow gauge Dinky pulled beside this railroad so that lumber and other material could be transferred.

The railroad followed the present day RiversideDrive, North Carolina Highway 104, past Renfro Corporation and along the Ararat River. The train followed past Johnson’s Creek, where a water tower, one of over a dozen, supplied water for the steam locomotives.

Next, the train carried passengers often to the White Sulphur Springs on excursions. The resort hotel is known for the foul smelling Sulphur water that smelled of rotten eggs. People had been coming to this place since the time Jeb Stuart’s mother lived here in the 1850s.

The railway passed near the Sparger House, which was once a tobacco farm and site of a tobacco factory before the days of Reynolds Tobacco and multi-national conglomerates. Near here, Totsey Hill and his large family lived on a farm I use to romp on with the Guynn kids, Teddy and Ann, as their mother Bertie was one of Totsey and India’s children.

One story about Totsey involves his brother Rob, who is Charles Hill’s father. Once a hot air balloon appeared over the Blue Ridge Mountains coming from Maryland until Rob Hill decided it must come down and with his trusty rifle he brought down. I have this photo of many people “long necking” around the basket of a brought down by Rob Hill.

The Dinky Railroad continued on up crossing the AraratRiver and heading towards the Virginia/North Carolina border, where it changes from state to commonwealth in Edith Brown’s pasture dissecting the line surveyed by Thomas Jefferson’s father Peter, Joshua Fry and an entourage of North Caroliniansand Virginias in 1749.

The rails or working on the rails brought many people to our area. Among them was John Edward Dellenback, who came to work on the railroad and then worked at Pedigo’s Mill. John married Serelda Mary Wilson and was the father of Charlie, who is the father of George, Walter, Eddie, and Mary.

The railroad passed by Laurel Hill, the birthplace of James Ewell Brown “Jeb.” Just across the road from Patrick County’s most historic site is a washed out trestle on the land of Eric and Amy Brown Sawyers. The railroad makes a curve and turns from the AraratRiver to Clark’s Creek across the land of Porter Bondurant.

I have known Porter most of my life, but Kenney Kirkman and Desmond Kendrick did not. So when Porter loaded us up on his John Deere Gator, I could see the fear in the city slicker’s eyes to have a man alive during World War One who actually rode the Dinky driving them around scared them to death. I also came to find that they were truly from town when Porter offered them free watermelons from his patch along Clark’s Creek. Porter grew watermelon on steroids, and I was left standing in the patch digging for the biggest one I could find when my city friends declined Porter’s generous offer.

Gordon Axelson, who is here today with his wife, my former high school science teacher, who, by the way, does not look like she is old enough to have been my science teacher, videoed Porter and his old sister Carrie Sue Bondurant Culler. Both of them rode the railroad, and it was one of the most memorable scenes of the research we did was to see a 92-year-old man being corrected by his older sister about their lives as kids.

The railroad continued along Clark’s Creek across the land of Dan Smith, Dwight Jessup, and a large trestle crossed the creek as the railroad made its way to the Holly Tree Road. The railroad continued up the creek across the bottomland of Diane King and then Howard King to the Homeplace Road. We were lucky to have Nick Epperson, whose family built the house here in Kibler Valley, who, like many people, sat down and talked to us about what he knew relating to the railroad and let us see his photos. In the 19 plus miles that Kenney and I walked most of the path of the railway, we never once ran into a landowner who was unfriendly or did allow us on their property. In fact, most we very enthusiastic and shared what they knew about the train.

We never encountered a mean dog. We met some very friendly dogs while walking the Isaac property. There are places that the railroad is not noticeable as cleared fields, and the flood control dam on Clark’s Creek erased traces of it.

Next, we walked across the property of Anthony Terry and James Clement. Later, Anthony discovered more than ¼ mile of the track while clearing a fence line for James and Charles Clement across the spot we had walked. We assume that the railroad was taken up and sold for scrap metal or, as Porter told us, “We sold it to the Japanese, and they shot back at us during World War Two.”

The railroad followed up the headwaters of Clark’s Creek just across from Church and towards the “Crossroads” the intersection of Squirrel Spur’s Road/Unity Church Road with the Ararat Highway. There was a siding in this area, and there are several stories about it.

One story about the railroad involved several of the Clement boys, who discovered several cars on the siding loaded with lumber. The boys investigated the cars one and discovered how to release the brake, and down the tracks, towards Mount Airythey went with their load of lumber until they realized that starting a railroad car was much easier than stopping one. The Clement boys abandoned train while the cars continued on derailing somewhere around Anthony Terry’s place, leaving lumber spread out across the bottom.

The train made its way up to the crossroads, where Bob Childress once worked in a blacksmith shop in sight of the Clark’s Creek Progressive Primitive Baptist Church. One famous story about “The Man Who Moved A Mountain” was that he brought the youth choir from this African-American church to his rock churches in a time of segregation. I often wonder if Childress heard those young Black voices before he found a personal relationship with Jesus Christ and began to spread the word about Christianity and made the courageous move of inviting them. When the railroad came by the church, there was a school for the African-American children that is today falling down behind the modern brick church. There are some things that show that we have made progress in this country, and the railroad witnessed it.

Another man of African descent, John P. Hairston, was a saw miller that heard that “Old Man Carter” was looking for experienced lumbermen. He came on the Dinky to make a living near the Dan River.

The railroad’s path continued across the land or Romey and Barbara Bowman Clement. Bobby, who is here today, shared her photos and knowledge of the railroad and our local history. She is what everyone involved in history should be a sharer, not a hoarder of it. She is a treasure for the people of Patrick County.

The railroad made its way parallel down the hill towards Fall Creek, making a wide turn before crossing the Ararat Highway below Greg Radford’s house. The largest washed out trestle we found is on Darryl and Sandra Clement’s property.

Down Fall Creek, the railroad went in a roadbed still visible in the winter past a sawmill once operated by Andy Griffith’s grandfather Nunn. Near Jerry Love’s cabin, the railroad turned away from the creek just above the flood plain. The railroad crossed the Dan River in this area into what we call Meadowfield.

The Love brothers, Jim and Jerry grew up in the white house at the foot of what we call Bateman’s straight on the Ararat Highway. They shared their stories and access to their property about the railroad. We came to believe there was a Wye (Y) shaped rail system at Meadowfield. One spur went up the Dan River to Kibler Valley, and another followed the path of the present day road to the point that it cut behind Jerry Love’s house and across the Kibler Valley Road and into what is today the Primland property.

William Leftridge Bateman, the son of William and Sally Bateman, came to work in the general store at Meadowfield, owned by Thomas Lee Clark. He married Judy Ann Joyce in 1906. Bateman purchased the Meadowfield store, and by 1910 there was a grist mill, fertilizer house, lumber yard, post office, water tank, and the boarding house, of which the latter is the only thing left standing. In 1916, a flood caused by a tropical storm destroyed the railroad and other structures at Meadowfield ending Bateman’s dream of an industrial. One of the Bateman’s daughters, Lena Mae, married James Beasley, and they ran the store at the “crossroads.” She spoke of her father’s store at Meadowfield selling overalls, shirts, shoes, turkeys, chicken, and even crossties and tanbark.

The Dinky railroad followed the eastern bank of the Dan River past the Zeb Stuart Scales Bridgeand towards the Sawmill Road. This part of the railroad bed is still in pristine condition and easy to walk in the winter. The path followed by Anthony Terry’s boyhood home and probably in the roadbed of the present Sawmill Road and back across the Primland property.

Kenney walked across the property of Leroy Pack into KiblerValley, still following the Dan River. The railroad made its way past Danube Presbyterian Church. When you think of Danube Vienna, the Sound of Music and Austriamight come to mind and not narrow gauge railroads and Presbyterians, but the railroad has come from a river named for a mountain Noah’s Arklanded on to a river with the same name as a great river of Europe or a tribe of Israel.

One of those who came to this valley was John Bishop Wilson, who was educated by Dr. Floyd Pedigo, who grew up near Stuart’s Birthplace. Wilson married Mahala Pack and went to work for the Epperson’s here in the valley. When the railroad stopped, Wilson bought some property, ran a one room store, built a house, worked on clocks, watches, and guns. He became the Superintendent of Sunday School at the Danube Presbyterian Church.

Kenney will talk about the chronological history of the railroad and about Kibler Valley, but I have tried to tell you about the path the train took getting her to the valley. I followed him around through nearly twenty miles of woods and fields with a clipboard and marking on a map. We ran into no hostility or even a mean dog, but we did meet and talk to a lot of great people like the congregation of Danube.

Reverend Gilley, you may not realize that it is hard to find verses about railroads in the Bible, but I had one recommended to me. Matthew Chapter 7 Verses 13-14 goes like this: “Enter through the narrow gate. For wide is the gate and broad is the road that leads to destruction, and many enter through it. But small is the age and narrow the road that leads to life, and only a few find it.”

Maybe to paraphrase would be narrow is the gauge that led this church to life.

Published on February 26, 2020 06:36

February 23, 2020