Eliza S Robinson's Blog

October 31, 2025

Ethical Dilemmas

“I want to do everything right.” That is what I tell everyone I have spoken to about research ethics. My supervisors, my colleagues, my friends, my parents, the Ukrainians in my life. Especially them. Navigating the research ethics process has been a wild ride of institutional bureaucracy, departmental power struggles, and my growing frustration with the lack of clear answers. I want an instruction manual, a step-by-step guide of what I should do when, and why.

I am six weeks into the second year of my PhD. Nothing from my first year could have prepared me for it. I knew this would be the year where things got real. A year of people and interpersonal relationships instead of reading and writing. “Instead of?”, past Eliza? That’s a great joke! The reading and writing doesn’t stop, but now I have to balance it with teaching and admin and being PhD student rep, and navigating the ethics application process, and trying to find time to do my laundry. It is a good thing that my entire London social life is concentrated around UCL, or I would not have seen my friends all month.

In our PhD training sessions last year, they told us that a time will come when we realise that we are the expert on our research project, not our supervisors. They didn’t tell us that when this time comes, it feels like you have been thrown in the deep end and someone is holding your head under water, telling you not to drown. Every time I feel the passion and frustration of my research, I grow more certain that I am the captain of my ship. Every strong opinion, every moment of conviction is a promise of the expert I will become. This is my research project, I am in charge here, and I don’t know what to do with that authority.

I want to do everything right, but nobody has told me how to do it. Every authority figure gives a different answer, every colleague offers different advice. My inner knowing is a contrarian, a visionary, an idealist. She does not mesh well with institutional bureaucracy. This term, I finally learnt how to spell bureaucracy, which tells you everything you need to know about academia! When I don’t know what to do, I have two options. Option one: I can talk it out. Talking it out soothes my anxious mind, but it is subject to human error, human absence, human webs of complex emotion. Option two is logical. I am a researcher, so I must research. I find 74 articles on research ethics; surely the nuance and clarity I seek will be there?

All I think about these days is research ethics. Not in a nerdy or neurotic way. It goes deeper than that. My colleagues tell me I am “pure of heart”, my friends tell me I have the right intentions and that is what matters. As I read the abstracts of 74 articles on research ethics, I am not so sure. What does it mean to be well-meaning and pure of heart? Neither of these traits will prevent me from unintentionally causing harm.

I don’t often feel powerful, so why I am so convinced of my own power when it comes to this?

If it’s not clear from “all I think about these days is research ethics,” my PhD is the centre of my life. I took all the intensity I once funnelled into hobbies and ill-advised crushes, and redistributed it to my PhD. My research comes first now. Once upon a time, before academia worked its way into my bloodstream, my great love was writing. Half my life ago, I wrote a novel about a scientist Tsar who creates a robot who is so realistically human that even she doesn’t know her true form. The irony of the novel is that she is far more human than he is. It was a futuristic retelling of the Persephone myth, set in 22nd century Russia and Estonia. I spent almost a decade writing and rewriting it, trying to perfect the monster I had created. There is a lot of backstory to this, and if you didn’t know me pre-2022 you wouldn’t know I’d written a novel at all. See, after years of rewriting and various attempts at self-publishing, I decided I was going to redraft my novel once more and try to get it traditionally published. I made this decision in early February 2022. My novel, where a significant storyline involved a war between Russia and a neighbouring country. On 24th February 2022, Russia began its full-scale invasion of Ukraine.

I remember trying to read through my manuscript, the sanitised, fictional war I had created, then reading the news about the atrocities Russian soldiers committed in Bucha. I put my novel down and never came back to it. Thinking of it now, a quote from Arthur Miller’s The Crucible comes to mind: “I may think of you softly from time to time. But I will cut off my hand before I ever reach for you again.” It’s an extreme way to view a novel I spent ten years working on, a novel I once thought would be my life’s work. But I am an extreme person. I read about the war crimes Russian soldiers committed in Ukraine, and I looked at my novel and knew that I was not qualified to write a story about war.

There is a particular intensity I get, a determinedness, a righteousness, a methodical, deliberate passion. I hear it in my voice when I talk about my research, or about teaching. I hear it when I talk about certain people, too. My voice slows down, my usual agitation replaced by calmness and certainty. My adherence to my principles is the scariest part of me. When I believe in something, I do not compromise.

I can’t imagine I will ever go back to that novel. Perhaps its title, The Purest Form of Chaos, was a prophecy of what it would become. I considered rewriting it, setting it in a fictional world. I would have to change so much of the plot that it would unravel completely. Writing The Purest Form of Chaos made me who I was, choosing to stop writing it made me who I would become. Last Tuesday I went to an underworld-themed creative writing workshop. It was the first creative writing I had done in god knows how long. Writing about the Persephone myth felt like falling into the arms of an old friend. I went to the workshop to get a much-needed break from my PhD, and spent the whole time writing stream-of-consciousness poetry about research ethics.

I am not self-indulgent enough to post all of it here. The poems I wrote were deeply personal, and far too specific in their imagery and subject matter for me to post online. But there is one line that sticks in my mind “If I put you neatly in a box, outside the reach of my microscope’s prying eyes, can I tell myself that first I did no harm?” When I followed the prompts of the underworld, I became the mad scientist. I became the villain from my novel of years gone by. My metaphors made me sound like a STEM academic. Perhaps sociology doesn’t make for good poetry, or perhaps there is a deeper fear behind it. I ended the poem with the lines: “You, the artist, the maker of worlds. I, the scientist, capable only of conducting a postmortem. How is it that you are the one preoccupied with death, but it is I who have lost the ability to bring things to life?”

The Ukrainian word for science refers to all academic disciplines. In English, we separate ‘hard’ science from the social sciences and humanities. I don’t view myself as a scientist in my day-to-day life, but my deepest fears, the caricatures of my shadow self, come complete with goggles and a lab coat. I am so conscious of my positionality as a British academic researching a community I am not part of. The more I read about the ethics of researching refugees, the more I question what good I can do. Is it even ethical to want to do good? There are layers to this. Area Studies as a discipline is rooted in colonialism and knowledge extraction. Refugee Studies has a significant history of Western researchers going to refugee camps in the ‘global south’ and either over-promising the impact of their research, or not telling research participants how their data will be used. Even academics who do research for the ‘right’ reasons still unintentionally cause harm. I know the power dynamic is different here, because I am conducting my research in the UK, and the conditions here allow for informed consent in a way that is not realistic in a refugee camp. But can I be sure I am not causing harm?

I have spent much of this year thinking about what it means to be an outsider, and the ways I can bridge that gap. It is the reason I (admittedly poorly) speak Ukrainian, it is the reason I have made such an effort to learn about Ukrainian art and food and music and history and culture. I have often questioned: when does one stop being an outsider? A new thought occurred to me today: do personal relationships blur this insider/outsider distinction? The more I go to Ukrainian events and make Ukrainian friends, the more the line blurs in my own head. The line between my personal life, my personal feelings and relationships, and my research. When I think of the Ukrainians in my life, I don’t think about my research. But when I think about my research, all I can think about is them. It has made me a better researcher, a better writer. It has given me a capacity for nuance that I lacked in the early months of my PhD. Making it personal has given me an unwavering level of devotion to my research that I know will sustain me throughout all the challenging moments of my PhD.

But it leads to new ethical questions. Who am I allowed to care about, and in what capacity? What happens when personal relationships and research-related relationships overlap? There is a part of me that tried to compartmentalise, as if I could somehow keep any friendship or care I felt for a person separate from their connection to my research. As if the two had not been connected by the red string of fate from the moment we met. The dilemma I keep coming back to is that my research is the centre of my life right now, and I want to talk about it with people who understand. I can either talk with other PhD students, who understand the relationship between a researcher and their research. Or I can talk to Ukrainians, who understand my research itself. But I am so conscious that the war, and leaving Ukraine, is a huge part of their life. At the same time, it is not the only thing that defines who they are. I am scared that if I talk about my research too much, I will make Ukrainian people in my life feel like I only view them as research subjects, when quite the opposite is true.

I once had a friend tell me that I viewed him as a science experiment because I read his astrology chart and made him do a 5 Love Languages quiz, so maybe this fear isn’t 100 percent tied to my research. I am analytical and I see patterns with an almost prophetic level of clarity, and I am a deeply intense person. When you take those traits and add a PhD to the mix, it’s a lot to handle. I have thought long and hard about where I, the human inside the researcher costume, fit into my research. I take my research incredibly seriously, but I am not a serious person. I have to ask myself, can someone who has seen my ridiculous side, my anxious side, my affectionate side, still view me as a serious researcher when it matters? Does my personality cancel out my professional competency?

As I navigate these ethical dilemmas, one thing becomes clear to me: I am on my own in this. My supervisors, my colleagues, my interlocutors, they are all part of my research world. But I am the one who must make the hard choices. The only way to trust myself is to face these challenges instead of asking someone else to be my moral compass.

September 27, 2025

A New Home / A Swan Dive / A Blank Page / A Rewrite

At the end of the bookshelf in my bedroom sits a painting by the Croatian artist Asja Boroš. A pomegranate split open to reveal the entire universe, captioned with the words “You can always reinvent yourself”. Fitting, I suppose, that the shelf leading up to it is filled with all my years of diaries. The painting used to hang above the sink in my kitchen. I remember looking up at it in March as I took a leap of faith, chose to be selfish, chose to be brave.

The first thing I notice about living in a girl house for the first time in years is that all our toothbrushes are different shades of purple. I could weep with joy. The scent of incense wafts through the air, the fridge is filled entirely with vegetarian food, and every time I look out the window, I see a different cat. I have landed myself in paradise.

The last time I lived in a 3-person flatshare was 5 years ago. I lived with two Sagittariuses and a cat. One of my new flatmates tells me they are both born in November and December. I resist the urge to ask their zodiac signs, but when she tells me they’re both “very chill” I strongly suspect I am once again living with two Sagittariuses. And a cat. His name is Sven; he used to live here and now he belongs to the neighbours. Sven does not know that he no longer lives here, and who are we to tell him? So we let him in, cuddle him on the sofa, and take pictures of his feet.

The only man I want in my house

My nervous system doesn’t know what to do with girl house. The clean bathroom filled with our many bottles of hair products, the plants, the warmth, the peace and quiet. I spent four years living with a man, and two weeks living alone in a lovely flat that I knew was temporary. Now, I can finally rest, but I don’t quite know how. So I keep busy. I unpack all my stuff in 24 hours (unheard of). I look around my bedroom, and for a moment it takes me back to the flat on Peel Street in Glasgow. I still have the same purple duvet cover. Most of the same books line my shelves. It would be easy to think the years hadn’t passed, that perhaps I hadn’t changed at all. The evidence is subtle. The small collection of books about Ukraine, the lesbian romance novels, the contents of my clothes rail. The only item of clothing I’ve kept for all those years is a black cardigan my friend gave me in Estonia.

The real evidence sits on my windowsill. A Citrine crystal and a sprig of rosemary from my yoga teacher. Three pottery figurines, made precious to me not just for their craftsmanship and beauty, but for the hands that made them. And a lesbian flag, leaning nonchalantly behind a candle in the corner. Indisputable evidence that I am not the girl I was in Glasgow. The crystal, the rosemary, the pottery cat and cauldron and indecipherable animal have all belonged to me since Sunday. The day I got the call from the landlady, telling me I could move in. I got the lesbian flag in April, from the LGBTQ centre in Blackfriars. I used to keep it tucked away in the back of a cupboard, now it’s the first thing I see when I enter my bedroom.

I have been living in a montage sequence since late August, speedrunning growth and progress and personal development. I told myself I stopped believing in fate. I still don’t know how to reconcile my trust in the universe with the knowledge that so many terrible things happen to good people every day. I don’t know how to spend years researching the worst experiences of people’s lives, without losing my faith in any benevolent force. Yet these past few weeks have felt undeniably fated.

Before I moved to London, I listened to Maisie Peters’ There It Goes on repeat for months. The lyrics were a prayer of sorts I’m back in London / I’m running down Columbia Road, I’m doing better / I made it to September / I can finally breathe. When I didn’t know if I would get PhD funding, when I thought I’d be stuck in Glasgow forever, I told myself I just needed to make it to September. This year, the song hit differently. It’s about coming back to yourself after a breakup. Knowing my lease would end in September gave it a newfound meaning. So I repeated my mantra, held the lyrics close to my heart. September came, and breathing was replaced with panic attacks and precarity. The hope I had held onto for months meant nothing now. The first week of September was one of the worst weeks of my life. I didn’t know where I would live after the 10th. All my friends were away and busy; I was alone and terrified and felt like I had no control over my life.

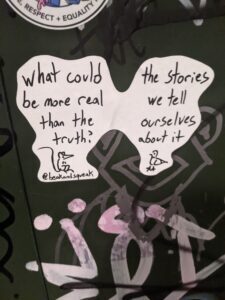

My miracle came through. One of my old flatmates from Glasgow had a friend with an empty flat until the end of September. For two weeks, I lived alone. I came back to myself, recalibrated after so many years of squishing myself down. As I stepped outside the next morning to go to the pharmacy, I found myself living another lyric from There It Goes: Brick Lane in the brisk cold. And I wondered, perhaps, if I was living this song after all. I watched kittens running from under parked cars in the early morning, took the fake-deep quotes pasted onto lampposts as gospel, walked in a two-hour loop from Whitechapel to Hackney every morning because my restless legs could not sit still. In my solitude, I reconnected with my intuition. I heard a voice in my head telling me shut up and listen, and went two entire days without sending voice messages. I don’t know what it says about my level of talkativeness that both my parents messaged me with concern when I hadn’t sent a voice message in a few hours. But I needed the quiet, needed the discomfort of stillness. I poured my thoughts into my diary instead of yapping to anyone who would listen. I created a new world in my head, an East London gothic, where the graffiti in Brick Lane is a portal to the underworld and the sweet dog drooling on me by the kiosk in Haggerston Park is a hellhound. I found my creative voice again.

https://elizaserenarobinson.com/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/PXL_20250911_091253011.mp4My two weeks in Whitechapel ended how they began: transporting everything I own down three flights of stairs by myself. This time I didn’t feel alone, I felt strong, I felt supported because I knew I could rely on myself. I needed my solitude, but by the time I left I was so excited to have flatmates again. I am not the solitary creature I once thought I was. I love to talk, I love to share, I love to be part of something. My flatmate tells me we can share cartons of oat milk, and my heart melts into a puddle on the floor. There are many ways to be alone, and I was much lonelier than I realised these past few years.

The universe has a sense of humour, but there is a lag on the line and the jokes take a few weeks to land. In the background of a voice message I received during the Week of a Thousand Panic Attacks, I heard the beep beep beep of an overground train opening its doors, the voice of the announcer saying “the next station is Homerton”. Before Sunday, I had been to Homerton once before. I went to a queer market in Homerton Library shortly after coming out as a lesbian. I bought an overpriced, oversized slice of black sesame and banana cake, and wandered around the neighbouring streets, sick from the sugar high. The first street I took after Homerton High Street had a mechanic’s garage on one side. I came up a different street when I went to the house viewing. It was only after I moved in, when I walked past the garage on a late-night run to Hackney Tesco, that I realised: I walked past my now-home way back in April, when the freedom of September was a far-off dream. I walk past Homerton Overground Station, and remember where I was three weeks ago, lying on my mattress on the floor in my old flat, listening to a voice message an embarrassing number of times because her voice soothed my panic attacks. I remember turning the volume up, holding my phone close to my ear, and hearing the train announcer’s voice in the background. A coded message from the universe that I didn’t know to pay attention to at the time.

The astrology girlie in me knew my life would change on Sunday with the eclipse in Virgo. But every moment of Sunday felt like fate. After weeks of viewing the most decrepit flats known to man, I viewed a lovely house with lovely women who made me cups of tea and chatted with me for ages. I walked along the canal by Hackney Marshes, my feet taking me towards Leyton when my brain was still undecided. I met a friendly cat by the canal, who flopped down on his back and let me pet his furry belly. Butterflies and dragonflies floated through the sunlit air beside me, a physical manifestation of the lightness I felt in my heart. I sat on a park bench, writing in my diary, trying to balance my logic and my intuition. In a moment of stillness, I heard a voice in my head saying take a leap of faith. I think of the therapy scene in Fleabag, where the therapist tells her “You already know what you’re going to do. Everybody does.” So I take my leap of faith, and I’m rewarded with the warmest hug and the reassurance that my anxious brain had craved. As I walk to the train station later, feeling warm and fluttery and hopeful, I receive a call from the landlady of the house I viewed that morning. I have reached the third verse of There It Goes: the universe is shifting and it’s all for me.

I spend Sunday afternoon at yoga, breathing easy for perhaps the first time in years. It’s a small class that week, and afterwards the three of us lie on our stomachs, kicking our feet in the air, and talk about astrology and crushes and British immigration policy (I contain multitudes, I’ll have you know!), and I am struck by the beauty of the life I am building for myself. I am surrounded by amazing women, I am surrounded by so much love that my heart is bursting.

At the start of September, I felt so isolated, so terrified of what came next. All I knew was I needed to be in control, and the London rental market was the one thing I couldn’t control. So I clung to control in other areas of my life, and I lost control there too. The plans I was holding onto fell through; I read into people’s texts too much and convinced myself they hated me. I was in the worst mental state I had been in all year, and I reached a point where all I could do was surrender, detach from the outcome. As I hovered around the stalls of a ceramics market on Sunday, I bought something called a worry stone. A small piece of pottery with a thumb print pressed into it. On the back, you write a word, a mantra to hold onto. I thought about the lessons I had learned over the past few weeks, and I chose the word surrender. The worry stone lives in my coat pocket now. I am not particularly anxious these days, but I press my thumb into it on the crowded tube, or as I walk through the bustling university campus. I feel the coolness of the clay, the smoothness of the glaze. Everything I did on Sunday was an act of surrender, an act of detachment. All the things I wanted are now mine, or at least finally feel like they are in reach, because I relinquished control.

All I can control in this world is my choices, my behaviour, my assumptions. So I choose to take great leaps of faith, I choose to stop assuming how people feel about me based on texts and look instead to their actions, their energy. I choose to be my full self, a person who is simultaneously a cat-loving astrology girlie who has a portrait of Taylor Swift’s head on Jesus’ body in her bedroom, and is also a serious academic doing important research. A person who cares so deeply about both the personal and the political. I am serious and silly, I am a competent, capable adult, and also a menace whose hobbies include bilingual flirting and constantly pushing my luck.

There is this strange paradox that comes with late-onset lesbianism. I have an adult brain and an adult body, but there is part of me that feels like the tape of my life has been rewound and I am a teenager once again. All the hard-earned maturity and life experience doesn’t take away the youthful part of me that yearns to hold a woman’s hand in a dark cinema, or tell silly jokes to get her attention. It would be easy to let the teenageness of it all consume me. But alas, I am 27 and my life is filled with emails and teaching prep, and I somehow have to find time for my actual PhD rather than just the admin of it. So I find balance, instead, as is befitting of Libra season. I fill my life with so many kinds of love and companionship. I make more friends, acquire more mentors. And in my quiet moments, I think of a hand holding mine, the brush of a thumb against my skin. I hold onto hope that one day all the things my inner teenager yearns for will find me. But I hope without attachment to the outcome. I hope for the joy of it, hope because wanting doesn’t have to feel like pain anymore.

The person I was at the start of September wasn’t ready for the things I yearn for. She had to unlearn the behaviours she spent years absorbing, had to learn how to be fully alone, to trust herself wholeheartedly. But in these weeks of pushing myself out of my comfort zone and relishing in the adrenaline of the freefall, I built someone new. Like my bedroom filled with old books and new trinkets, I have held onto the parts of myself that were too precious to let go. I regained my sparkly side, my fun and adventurous side, my creativity and my curiosity. But I’m not the person I was the last time I was single. I am no longer 23 and insecure. I am 27 and in love with the serenity that aging brings. I look at the life I live now, and think of the Taylor Swift lyric these hands had to let it go free / and this love came back to me. I had to let go, I had to watch everything that felt certain slip from my grasp, because that was the only way to grow into the person I needed to become. This month I lived out the lyrics of There It Goes, as the prophecy foretold. Now I have made it here: a new home / a swan dive / a blank page / a rewrite.

September 2, 2025

I Knew My PhD Would Test My Patience; I Didn’t Think It Would Test My Entire Belief System

There’s a term that often crops up in Migration and Refugee Studies scholarship: temporal uncertainty. It describes the lack of information and clarity regarding one’s future, the way this impact a person’s ability to make plans, impacts how they exist in space and time. Two hours after finishing a draft of a PhD chapter that strongly draws on this topic, I received a call from my would-be future landlord, telling me that I could not, in fact, move into the place I was meant to be moving into four days later. He repeated a nonsensical excuse every time I asked him why. I stood up for myself, reminded him that I had repeatedly asked him to confirm that I could definitely move in. I had triple checked with him before I stopped looking for somewhere else, and he completely screwed me over. I have eight days left on my current lease, and no idea where I’m going to live after that.

As I run back and forth across London in the rain, filling my days with futile flat viewings, the weight of temporal uncertainty settles on my own shoulders. I haven’t felt this detached from my own future since the covid lockdowns five years ago. I try to imagine my life in just over a week from now, and I can’t. I don’t know which part of the city I’ll be living in, I don’t know whether I’ll have found somewhere permanent by then. I barely sleep; I barely eat. I am running on adrenaline and hot chocolate and a constant refrain of “I’m going to fucking kill myself”.

I have waited for September for so long. September, where I can finally stop living with my ex, five entire months after breaking up. It has been five months since I realised I was a lesbian and ended my relationship, and I have put parts of my life on hold during that time. I was so excited for a clean break, to finally close out a chapter of my life that I’d outgrown and move onto something more aligned. Instead, I am filled with dread. I can’t even distract myself with silly little fantasies, because there are gaping plot holes now. I imagine hanging out with a person I’m so excited to see, imagine talking to them as we walk to the tube station and hug goodbye. But which tube station, when I don’t know what my route home will look like in eight days from now? There is very little that I can control right now, and there are even fewer mental escapes.

At the same time, I am deeply aware that my problems aren’t that bad in the scheme of things. I see videos of Ukraine being bombed, of people losing their homes or their lives, and I feel guilty for wallowing in self-pity about my own living situation. As a PhD student researching refugees, I spend a disproportionate amount of my time reading about the worst experiences of people’s lives. I was able to compartmentalise for so long, to create this distance between my own outlook on the world and the work that I was doing. Then I started forming personal relationships with Ukrainian refugees.

I spent most of the past couple of weeks writing about the precarity of the Ukraine Visa Schemes. For anyone who doesn’t know, Ukrainians do not have refugee status, and they have no pathway to settled status or indefinite leave to remain. The visa schemes are part of a larger aid package, including things such as military aid, which means that they are a foreign policy/soft power tool rather than simply a refugee settlement policy. The British government is notoriously hostile towards refugees, and the Ukrainian government doesn’t want to permanently lose a significant part of its population, especially when the demographic is predominantly made up of women and children. It is 3.5 years into the full-scale invasion, there have been increasingly deadly bomb attacks on Ukraine this summer, and the supposed “peace talks” involve rolling out red carpets for the war criminal that started this, instead of sending him to the Hague or the morgue where he belongs. It is absolutely absurd that there are no longer-term protections in place for Ukrainian refugees after all this time.

On Monday last week, I worked on my chapter draft. But on the Sunday before, I went to a protest, and spent time with Ukrainians. For most of this year, the main feedback I’ve gotten from my PhD supervisors is that my writing lacks nuance, that I make generalised statements, that it needs reframing. This time, it was almost too nuanced. My supervisors told me it was too passionate, too critical. That if I am going to make this argument, it needs to be written in a dry, logical way rather than coming from a place of emotion. But all I am is emotion now. I can’t write about the precarity of the Ukraine Visa Schemes without picturing people I care about. I can’t make a single generalised statement, because I am drowning in the nuance of it all. The precarity isn’t distant anymore, it isn’t hypothetical. I imagine what could happen in a year from now if the Ukraine Visa Schemes aren’t extended. I picture the woman I spent time with the day before, her warm, infectious energy, the cartoon cat on her T-shirt, the deliberateness and care she takes when she speaks to me in Ukrainian. I picture a world where she has to leave, where she isn’t safe. It was all I could think about as I wrote. Frankly, I don’t think my chapter was passionate or critical enough. The Ukraine Visa Schemes are basically the subscription model of refugee policy. Everything is at your fingertips right away, but it’s temporary, removable at a whim. It is so paradoxical that these visa schemes have all the ingredients necessary for integration, for settlement, for rebuilding a life in this country, and offer no pathway to do so. What is the point of creating a system that is specifically designed to help people settle, and not allowing them any kind of security or guarantee for their future here? I have many thoughts on this subject (hence the PhD).

There is this concept in Philosophy of Religion called The Problem of Evil. It’s been a decade since I took A Level Philosophy, so my memory is patchy. But the crux of it is: how can a benevolent God exist, when there is so much evil in the world? I don’t believe in God, but I believe in something. Some universal energetic force, something that connects all of us. Throughout every shitty thing that’s happened in my life, I have trusted that things will work out in my favour. For twenty-seven-and-a-half years, I have held an unshakeable faith that I will always end up exactly where I’m meant to be. Even when I’m catastrophising and everything feels impossible, my instinct is to believe that things will always work out for me, that I am blessed. I don’t know how to reconcile that faith with the reality of the world. I don’t know what I believe anymore. If life always works in my favour, why didn’t it work in the favour of all the people who’ve been killed by Russian bombs this week? How can I read about the death of a little girl who was born during the full-scale invasion and was killed during the full-scale invasion, and go on to believe that I am uniquely safe from misfortune? How can I look at the kindest, sweetest people, and see all the ways that they have suffered, and choose to believe that the universe will spare me in particular? I’m not above cognitive dissonance, and delusion is my middle name, but you can’t spend a year researching people’s suffering and ignore the fact that bad things happen to good people all the time.

I knew my PhD would test my patience, but I didn’t think it would test my entire belief system.

If I can’t trust in some universal plan, what can I put my faith in? I think I have the answer, and it is so cliché: each other, each other, each other.

When I get yet another rejection from a potential landlord, I text a friend and ask to meet. I tell her I need a hug. We live on opposite sides of the city; it is a long way to travel to give someone a hug. Yet I don’t hesitate to ask. It’s only later, when we’re sitting by the window in Damsel Collective, drinking ube lattes as she makes me recite a list of all the things that make me an amazing person, that I realise this is the first time I’ve done this since moving to London. The first time I’ve done this since my best friend moved away from Glasgow in March 2020. For the first time in five years, I was able to tell someone exactly what I needed, and know that they would drop everything and be there for me. I tell her she’s my best friend in this city, and she tells me the same. I am still terrified about finding somewhere to live, but relief floods through me. Because having a best friend is a safety net. Having a best friend means that even if the universe is not on your side, someone is.

I have met a handful of people since moving to London who felt destined to be in my life. The woman crying outside the Anthropology building in January, who became the rock that kept me sane throughout this tumultuous year, even when she was on the other side of the world. The woman I met in some remote corner of UCL in November, both lost after an event and all the gates were closed. How we helped each other find our way out of the university (there is a metaphor there somewhere), how months later, talking to her for two hours fundamentally changed my relationship to my research, shook me out of my inertia and unlocked a level of care in me that I don’t know how to restrain. Sometimes you meet people and it feels like the hand of destiny has picked them up and put them on your path. It’s easy to call it fate when you meet people who are warm and affectionate and feel like sunshine, but to call it fate would mean that every bad thing that happened in their life to bring them into yours was also fate. I don’t want to believe in a world like that. I don’t want to believe that good people were meant to suffer just so I could have the joy of their company.

Many years ago, I had a friend who didn’t believe in fate. I believed in destiny and soulmates and everything fantastical, and he told me that it’s more beautiful to believe that loving people is a choice. That you choose people over and over again, that love is an action. Perhaps every ‘fated’ meeting was the natural conclusion of a series of choices. It feels unnatural for me to say it, because deep down I do still believe in some degree of fate, but I don’t like what that implies.

Two days ago, I set a reminder in my calendar to spend yesterday practicing Ukrainian. I imagined this would involve crying into my grammar textbook and scrolling through Instagram reels every five minutes. I will admit that it felt like fate when I saw that my favourite Ukrainian café was looking for volunteers to help with their renovation. But it was a choice to do a 3-hour round trip to paint chairs for 5 hours. I was desperate for a distraction from my housing situation; I longed for any task that would prevent me from looking at my phone for a few hours. I went there in search of manual labour and Ukrainian language immersion. I spent hours kneeling on the floor, painting chairs and absorbing the ambient Ukrainian around me, noticing the subtle differences between their Kryvyi Rih dialect and the Zaporizhzhian one I have grown used to. Later, we sit outside on foldable chairs, eating cherry pie and buckwheat with stew as the sun begins to set, and I make a choice. I tell them about my research. The café, Cream Dream, was founded by a woman called Lisa, who is a Ukrainian refugee. She came here when she was 23, she did not speak any English at the time, and she managed to found this amazing business all on her own. When I told her about my research, I was almost apologetic. I emphasised that I don’t know if my research will have any impact on government policy, that I don’t know if it will do any good in the world, in spite of my best intentions. She told me that what matters is that I chose to do this, that it shows I care. She said she didn’t have the words in English to fully express her emotions, but later, she gives me the longest, warmest hug. We make heart shapes with our hands, and the heart in my chest is full of gratitude and emotion.

On Saturday, when I was having a London rental market-related breakdown, I told my friend that I feel like I have no control over my life. She told me that’s not true, that I have control over my PhD. I laughed and laughed and laughed. It often feels like I’m failing at my PhD, that I’m never doing enough. My writing feels like a mess, I barely speak Ukrainian. I feel like I’m behind on deadlines I didn’t even know existed. Then I spend time with Ukrainian people, feel their warmth and kindness, their sweetness and encouragement of even my most basic attempts to speak their language. And I see that I have chosen to spend 3 years of my life doing work that makes people feel seen, makes people feel supported. There are plenty of things in my life that I could ascribe to fate, but my PhD isn’t one of them. It is the product of consistent choices and relentless determination. This work has always come from a place of care.

In a city like London, it is easy to isolate yourself. You can complain about the lack of community, the alienation of a city this size. Community isn’t something you fall into. It requires effort, it requires consistency, and it requires choosing to show up. You can choose to be the person who goes out of their way for others. You can choose to live your life from a place of care. You can send the “I’m thinking of you” messages, you can travel half way across the city to support your friend when they’re having a bad day, you can paint chairs for your favourite café, you can devote years of your life to a PhD in Ukrainian Studies as penance for your former interest in Russia. Being a person who cares ‘too much’ produces far more tangible results that leaving it up to fate. You get to choose your community. I have spent most of this year hovering on the edge of Ukrainian spaces, feeling like I shouldn’t be there, awkward in my linguistic limitations. I may lurk on the sidelines, but I show up consistently. I learn the memes and the references and the protest chants and the national anthem. Every hour I have spent in a Ukrainian café— tucked away in a corner, letting the language wash over me—every protest I went to, every Ukrainian event, was me choosing a community and showing up for them. Choosing to let myself be seen, forming real, meaningful relationships with the Ukrainians in my life is one of the most important choices I have made. It has cost me my belief system, but I have gained something far more tangible than faith and fate.

August 26, 2025

Woman Heals Self-Esteem Through the Powers of FRIENDSHIP and LESBIANISM

Back in June, I set myself a challenge. A little experiment. After my lesbian awakening had put me through the ringer and taught me some valuable lessons about where I should invest my energy, I took stock of where I was at in my life and realised: all my good friends, all the people who love me, liked me from early on. Even when I was shy and awkward and still in the process of becoming. The people who liked me, liked me from the start. Following that logic, I wondered what would happen if, when I had the opportunity to get to know someone new, I showed up as my full, unfiltered self, right from the beginning. And thus, the experiment was born.

It was a series of choices. I let myself be talkative, let myself share unrelated anecdotes without worrying that I was being annoying. I let myself send voice messages instead of carefully polished texts. I let myself be philosophical and rambling and say all the thoughts in my head. Let myself be an excitable puppy whenever I had the opportunity to talk to a person I liked. It wasn’t a test for someone to pass; it was a way of rerouting back to myself. Of testing the hypothesis that if someone is going to like me, they will like me for my imperfect, unfiltered self.

I forgot about the experiment, but the experiment didn’t forget about me. Unbeknownst to me, it had changed the way I see the world. I became the kind of person who reaches out first, who openly shows affection, who shares my passions and thoughts and opinions. Who can navigate social gatherings with relative ease. A handful of choices I made way back in June transformed me into someone confident, and it had ripple effects throughout other areas of my life. My relationship to my PhD research changed. I let myself feel all the emotions, the anger and frustration and compassion, the sense of powerlessness that often accompanies trying to do good in the world. It turned out that messy, imperfect, unfiltered Eliza is so much better at being a person that her tamed counterpart.

The experiment found its way back to me on Sunday. A quiet presence, tap tap tapping at my side. Soft and gentle, like a hand on my shoulder, pointing out the obvious: I’m not shy anymore. Perhaps I should have realised earlier. It’s been a month of social gatherings, of getting to know friends of friends, of being at ease in the company of strangers. I spent so much of my life thinking I was introverted, when really, I was just anxious. I love being around people, I love talking, and with the right people it feels so easy. But accepting that I’m (it feels weird even suggesting this) likeable means rewriting the story I have told myself for the past 27 years.

Sometimes I make an offhand comment to my friends about how I have no social skills, and they’re always confused. Because I’m repeating a story from before they knew me. No one else knows the stories I believe about myself. It’s not written on my forehead that I’m unlikeable or awkward or too much. People only know I’ve internalised those beliefs if I tell them. And I don’t have to tell them.

The Great Lesbian Awakening of March 2025 was a watershed moment in the Eliza history books. It required me to be selfish; it required me to be brave. For the first time in my life, I fully chose myself. Chose my own potential, my own needs and desires. I chose the possibility of a life that I had to believe existed. At the time, I felt like I was dying. Yet 90 percent of my social anxiety disappeared after coming out as a lesbian. I became outgoing and talkative and bold.

This is new territory for me, trusting that people will like me for who I am. I see the evidence before my eyes, and my brain still tells me to doubt it. I am wrapped in a cosy quilt of green flags, and the voice in my head insists that I must be colourblind. Because surely it’s too good to be true, that you reach a certain point in your life and you outgrow your demons? Did I outgrow them, or sacrifice them? I sacrificed conformity, I sacrificed the path I had committed to for years. And maybe there is a reward on the other side of that. Maybe all the things I hope for are within reach.

I wrote a list shortly after the Great Lesbian Awakening, of non-negotiable qualities I look for in a partner. I’ve only made one change to the list in the months since. Amended “someone in academia who understands this side of me” to “someone who understands why my research is important to me”, because, frankly, I spend enough time around academics. What I really need is to be with someone creative. Perhaps that it my main non-negotiable. I looked at the list today for the first time in months, and realised my life is filled with people who have all these qualities. Shared values, shared ethics, shared interests. People who show up for me, who go above and beyond for me. I look at all these traits that I dreamed up at a point in my life where I desperately needed to cling onto hope, and now I know they’re real. There are people who are creative and fun and kind, who are also reliable and mature and emotionally intelligent.

Perhaps the greatest change in me this year is that I’m learning to find joy in being seen. I hold court at a friend’s party, reading astrology charts and telling stories. Everyone goes quiet and listens attentively when I talk about my research. I am seen in all my shades. My humour, my flamboyance, my sense of justice. I get to be everything at once. I bake a cake for another friend, and remember that I feel most like myself when I’m feeding the people I care about. I reunite with a friend after 5 months apart. The last time she saw me was before my breakup. I am a different person now, bright and sparkly. I am filled with an incredible lightness. There are so many kinds of love to learn, and they’re all interconnected. The love you have for your friends shapes the way you love yourself. If all these beautiful people can love you, that must mean you’re worth loving.

I look at the incredible friendships I have, and rewrite the doubts I have about finding romantic love. I consult my council of queers, sending lengthy voice notes trying to decipher whether someone was flirting with me. I take their advice with a heavy pinch of salt, but two threads of hope burn within me. The hope that they are right, and the hope that comes from knowing I’m loved. My friends don’t doubt that someone would flirt with me, because they don’t look at me through the critical eye that I perceive myself with. They see the good in me, and assume that others will too. I think of the way my friends see me, and I rewrite another story. I am no longer defined by all the years of men making me feel inferior. I am allowed to consider the possibility that a woman was flirting with me. The voices in my head are still like “oh my god, Elizaaaa, you can’t say that!!! You can’t just admit that it’s within the realm of possibility that someone would find you attractive, god!!”. I rewrite the story nonetheless, throwing the voices in my head, kicking and screaming, into the pits of hell where they belong.

I am a deeply unsubtle person. I can either be silent, make myself invisible and slowly wither away – as I did for years. Or I can be loud and vibrant, knowing that I will be seen for exactly what I am, in all the awkwardness of wanting. I am learning to make myself visible again. I buy red lipstick for the first time in years. I wear sparkly purple earrings and cover my fingers in eclectic rings. My magpie brain is determined to be as shiny and sparkly as possible. I let myself flirt shamelessly, even though I promised myself I’d be a good girl and do no such thing. But it’s so easy to slip into the performance of it all, the wicked look in my eye and the teasing tone of my voice, moulding new meanings from a language I’m still learning to speak. It is a performance in the same way my femininity is. Completely natural, completely me, yet embedded with the desire to show off, to be seen in all my sparkles.

Being seen means allowing yourself to be seen in your wanting. This is the part I still struggle with. I don’t do subtlety, as we’ve established. I possess an incurable earnestness and I wear my heart not on my sleeve but on my face. As a queer woman, the relationship between visibility and wanting is even more complex. The fear of being seen as predatory. Even with other queer women. I am so new to all of this; I still feel like a fraud when I tell people I’m a lesbian. Even though it is the truest part of me. It would be so easy to hover on the sidelines; to let the months and years slip by and repeat the lifelong narratives of being unwanted, undesirable. It would feel less awkward than risking rejection. Reject myself, reject my own potential before anyone else has the chance. But I’m not that person anymore.

I feel younger at 27 than I did at 23 or 24. I am no longer shackled to the heterosexual timeline that says women expire by a certain age. I get to be wacky and whimsical and exist at my own pace. For the first time in my life, I feel like I fully belong to myself. Each time I uproot a story of unworthiness, years of my life are returned to me. I can dream bigger dreams now, envision a future where I am loved exactly as I need to be.

There is a conversation I have with my friend from time to time, about how we are both over-givers. Pouring and pouring ourselves into others, overcompensating. Always the planner, always the one who puts in effort. Never able to rest because if you don’t take care of everything, who will? The first blog I wrote post-breakup/lesbian awakening was on this topic. About neediness vs. having needs. There are many traits I look for in a girlfriend, but ultimately I want to be with someone who puts in the same kind of effort that I do. Someone who pays attention to detail, who is organised and conscientious. Someone mature and responsible, so I don’t have to shoulder this burden for the both of us. I want someone creative and funny and whimsical and cute, but these traits must exist alongside self-awareness and responsibility. Sometimes I think I’m unrealistic for believing qualities like this could coexist alongside each other. But I’ve rewritten that story too. Perhaps the real reason I feel younger now than I did in my early twenties is that I keep meeting people who change my perspective on the world. I meet people who show me everything I believe in is possible. When I meet people who make my world brighter, I am so glad that my shyness has faded. That I can tune out the noise in my brain and turn towards them as a sunflower turns to face the sun, breathing in their light.

July 28, 2025

Reframing, Re-potting, Rerouting

A few months before I moved to London, my mum bought me a monstera plant. She told me that taking care of a plant is a good reminder to take care of yourself. If the plant is slowly dying, perhaps you are too. I kept my plant alive, on the windowsill of my dimly-lit living room. I watered it once a week, re-potted it before leaving Glasgow, cut off the wilting leaves. Since moving to London, my monstera has had all the sunlight it could need, but I often forget to water it, and the roots are so tightly packed within its pot that I’m surprised it’s hanging on. I can never quite bring myself to pay the £20 for a bigger plant pot. Sometimes I see the monstera dying, and I know it needs more space; more water, more soil. But the thought is gone before I can act on it.

On Saturday I walked through Hackney, on an expedition to an Eastern European shop to practice my Ukrainian. Everywhere I went, I saw plant shops. When I finally took the bait and stepped into one, I was not drawn in by the plants themselves, but by the pots they grew in. A purple pot caught my eye, too small for my monstera, shimmering in the dappled sunlight through the windows. The jungle of leaves around me was reminiscent of Glasgow Botanic Gardens, and I was transported to a different era, a time in my life where I, too, needed to be re-potted. I looked at the leaves, the soil, the ceramics, and I thought about how both plants and clay come from the ground. The clay is dug up from the earth, shaped, fired, painted, and becomes a vessel for plants that are equally uprooted. What does it mean that they find each other again, in spite of the changes they have been through?

Last week, I attended an East European Studies conference. The final panel I went to was on Ukrainian literature. I learned about a 20th century Ukrainian travel writer, Sofia Yablonska. She travelled to Morocco and China and many more locations, and was the first Ukrainian woman to write about these countries, one of the first female documentary cinematographers in the world. She was obsessed with earth and clay. Yablonska eventually settled down in France, where she built a house, and served her guests Ukrainian borshch in Chinese bowls. Again, I thought about mobility and rootedness, and the vessels we create to hold these parts of ourselves. The countries I have travelled to, the parts of me that were shaped by those experiences. My love of black ryebread, my never-ending supply of anecdotes beginning with “when I was in Estonia…”. The choice of it all. The freedom to run towards something rather than the necessity of flight. Lately all I seem to think about is the vessels we create. The ones we shape with our hands, from clay, from dough, and the ones we shape from words, with questions, arguments, dissertations. The more I release the hold the English language has on my brain, and let myself fall into the arms of Ukrainian, the more I understand language as a boundary, language as a vessel, language as the frame that defines the pictures we see.

At the conference, I was surrounded by Ukrainians. Immersed in the Ukrainian language in a way I never had been before. It’s one thing to go to a Ukrainian café and hear the language for an hour, or listen to podcasts specifically designed for language learners. But spending five days surrounded by people talking amongst themselves in Ukrainian was beautiful. I didn’t think I would get that kind of language immersion at this point in my learning. When the conference ended, I found the thing I missed most wasn’t just the panels or the people, but the Ukrainian language itself. Its softness, its rhythm, its melody, the space my brain holds for it even when English is louder. For someone whose great love is writing, there is such a unique beauty to falling in love with a foreign language. Especially a language that is less well-known, less romanticised than the languages people typically learn. I wonder what it would be like to reach a level of fluency in Ukrainian where I can write as freely as I do in English. The Ukrainian word for “fluent” directly translates to “free”. I have loved the English language for my whole life, but these days it feels like a swollen, roaring river, bursting its banks and flooding the fields around it. In English I have too many words, and in Ukrainian I have too few. Ukrainian is a vessel I am still learning to fill, but English is a plant pot too small for my tangled roots. Learning to hold two languages in my brain has taught me that I myself am the vessel, the drawer of boundaries. Both the plant and the person who forgets to water it, who procrastinates buying a plant pot that will match its size.

The most useful critique my PhD supervisors have given me this year is that my writing needs reframing, that I can’t cover everything. When they told me to reframe my literature review, I drew myself a picture. I sketched out a photo frame, wrote “gender and forced migration” over and over within the lines of the frame, creating a thematic border. Outside of the frame, I wrote topics such as “gender in sociology” “queer migration studies” and all the themes that were too broad for this section. Within the confines of the frame, I wrote all the topics that were relevant to my literature review. Gender and refugees, gender and Ukraine, etc, etc. I don’t know if drawing a picture improved my writing, but drawing boundaries did. I created a visual vessel for the ideas that were relevant, and was able to drown out all the noise of the broader context and themes. Yet the real improvement in my writing came from the dissolution of mental boundaries. When I stopped compartmentalising, and let myself feel the full extent of my compassion, my horror, my sense of justice, that was when I wrote something that made sense. As a researcher, my role is to be a vessel. My role is to hold space for the people whose experiences I will document. Committing to my research requires an abdication of self, a temporary hollowing out of the space in my heart and mind to let someone else occupy it. The more I become such a vessel, the more I feel like myself.

I am in a transitional phase, within myself and within my research. Within the past year I have outgrown so much. A city, a relationship, an identity, a way of inhabiting the world. I look at my monstera plant, cramped in its pot, and see myself in my current flat. I know I will be moving in September, just as I know I will re-pot my monstera eventually. I tell us both to hang on, that something bigger and more comfortable is out there. That one day it will have the space to expand, as will I. I am patiently waiting for this period of becoming, yet I know that when I have the space to flourish, I will become someone I can still barely conceive of.

My research, too, has outgrown its initial limitations. It happened when I realised that I am never “off the clock”, so to speak. I can draw boundaries such as not doing PhD work on weekends, but I can’t switch off my caring. I can’t switch off understanding Ukrainian. I can’t switch off reading the news and feeling my heart break. So I stopped trying, and let myself feel it all. At the end of June, I shifted the paradigm I had been working with. I stopped viewing my PhD as essentially a job, and let it become everything to me. The boundaries I had built to keep the feelings out changed form, became a warm embrace, a hand to cradle the emotions. I built a new vessel, and found a sense of purpose I have so rarely felt before. I also found anger, and an increasing sense of frustration. The more I learn about my PhD topic, the more I befriend Ukrainians and hear their stories, the harder it is to talk to people who repeat misinformation without questioning it. This anger is changing me too. Where I once would have stayed quiet, doubted my own authority, I am learning to argue, learning to educate. Doing a PhD means becoming an expert, and what is the point of becoming an expert if you do not use your expertise to advocate for the people or causes you care about?

I believe that any extended creative or academic project is an act of devotion. To spend years of your life learning about a topic in detail, writing about the minutiae of it, requires a relationship to the work that goes beyond ego and status. The devotion I feel towards my PhD has reached newfound depths this month. It is transformative, it is pure, it is beautiful. Yet it brings with it a feeling of alienation. For the first nine months of my PhD, my relationship to the work was shaped by my day-to-day life. My PhD was the experience of being a PhD student. PhDs are lonely endeavours, but there is a sense of companionship in the day-to-day challenges, because I know my colleagues are navigating those too. But my research topic itself is vastly different from the things my colleagues are researching, as is common in an interdisciplinary Area Studies programme. I am surrounded by historians and political scientists and literature scholars. My research may have been theoretical this year, but in a few months, I will be working directly with traumatised people. That is not a relatable experience. I read that researchers who interview refugees often experience vicarious trauma. I don’t know what to make of that, because this is something I’m entering into willingly. Any discomfort I may experience doesn’t feel like something I can complain about. Yet I think about this possibility often these days. On Saturday I read the parliament proceedings from the debate about the extension of the Ukraine Visa Schemes. As MPs described the ways their Ukrainian constituents are suffering from temporal uncertainty over their ability to stay in the UK, I had tears in my eyes. They referenced a child who has the same name as a Ukrainian friend of mine, and I was fully sobbing. I’m doing an excellent job of being a vessel for other people’s emotions, clearly. I tell myself that when it comes to conducting my interviews, I will be able to leave my own feelings at the door, as if I don’t cry at the drop of a hat.

Before I started my PhD, I thought I knew who I needed to be to do this work. I thought I had to be this idealised version of myself at the start. I wasn’t her. I don’t even know if I have become her now, almost a year in. I am someone else entirely. Being the right researcher for this project isn’t about being perfect. It’s not about being fluent in Ukrainian, or being the picture of professionalism, or knowing how to network. The specific angles of my research project are a product of my specific way of looking at the world. There are plenty of academics researching Ukrainian refugees, but the questions my research asks are unique to me. It’s not about being perfect, it’s about being committed to the work, and understanding why it is necessary.

The truth is, I don’t know what impact my research will have. Perhaps it will become a book that only two people will read. Perhaps it will have some meaningful impact on government policy. But at the very least, I hope it will give people a space to tell their stories and feel seen and heard. I hope it will provide people with catharsis. My research is itself a vessel. It is a vessel through which Ukrainian refugees can discuss their experiences in the UK, it is a vessel for conceptualising and understanding broader trends in British migration and refugee policy. And it’s a vessel for my own growth as an academic, and as a person. The more I try to dismiss my own personhood in the process, the more I learn the necessity of being a person here. I am not a fly on the wall; I am not an objective observer. I am a person who feels deeply, I am a person who is motivated by love and friendship and interpersonal connections. Letting those parts of myself inform my research is a necessity.

July 17, 2025

Once More, With Feeling

After two years and nine months of learning Ukrainian, something glorious and unprecedented has happened. My obsession-prone, attention-span-of-a-goldfish brain has finally hyperfixated on something useful: the Ukrainian language. My brain has never been built for consistency. I can count on one hand the things I have stuck with long enough to get good at them. I either have an intrinsic, interest-based motivation that carries me for years, or I am utterly indifferent.

My motivation for learning Ukrainian was indirect. It came from a place of logic and principle. I believe that if you are researching a group of people that you do not belong to, learning their language is the bare minimum. I am committed to my PhD research; therefore, I am committed to learning Ukrainian. That said, it felt like pulling teeth for the first two years and eight months. Over the past few weeks, my relationship to my research has changed significantly, and my relationship to the Ukrainian language has changed with it. When you only interact with a language in a classroom setting, speaking the language will inevitably feel like trying to pass a test. At best, you memorise the script, but you don’t get a feel for the language. Combine that with perfectionistic tendencies and a predisposition to procrastination, and it’s a miracle I can speak Ukrainian at all.

Every time I had spoken Ukrainian outside of the classroom, it was either to talk about my research, or to order coffee in a Ukrainian café in Covent Garden. I was either worrying about coming across as professional, or trying to remember the correct conjugation for oat milk. Either way, I was trying to pass a test.

The Ukrainian language comes alive to me in a pottery studio in East London in late June. I am half-soaked from the rain, drinking green tea and staring directly into a pair of blue-grey eyes because I never quite learned how to make normal eye contact in all my 27 years on this earth. She is telling me something about the Ukraine Institute’s events, and I am realising just how little Ukrainian I can understand. The only word I can muster is «Боже» (“oh god”) before switching back to English. If it is a test, I am definitely failing, but it doesn’t feel like a test. For the first time, I am listening to someone speak Ukrainian, and feeling at ease. I don’t have the vocabulary, I don’t have the language comprehension skills, I can only really nod and say «так» instead of contributing to the conversation, but I don’t feel like I’m taking an exam.

I feel safe in my imperfection, and it unlocks a curiosity in me. The next day I send a voice message in Ukrainian, and my brain is a dark void. My visual mind has switched off, and I finally get it. The reason Ukrainian never clicked for me is that all I have done is memorise words, but not the feelings and images attached to them. I talk about a meeting with my PhD supervisor, and I don’t picture my supervisor. If there is an image in my mind at all, it’s of a classroom and my former Ukrainian teacher. I think of where I learned the word, not its meaning. Of course my mind is empty. Of course searching for Ukrainian vocabulary feels like fumbling around in the dark.

I have only ever spoken Ukrainian to get it right. To be a good student, to have correct grammar and the right vocabulary. I never spoke Ukrainian to communicate. I never used the language the way I use English. As a writer, language is everything to me. I thought that meant language in general, not English specifically. As a native English speaker, I have rarely had to consider the relationship between my feelings and the language I verbalise them in. My feelings are my feelings; they belong to my body. Yet I only know how to feel in English. For the first time, I begin to wonder what it would feel like to have a friendship in a foreign language, or to fall in love. Would «я тебе кохаю» ever hold the same emotional depth for me as “I love you”? Would I always feel like a part of me was lost in translation?

I never felt emotions in Ukrainian, yet that void held important space for me.

A few months ago, I went to this seminar about the psychology of bilingualism, and the speaker shared an anecdote about a bilingual Korean-Canadian man who was trying to decide whether to break up with his girlfriend. When he thought about it in Korean, he couldn’t bring himself to do it. Yet when he considered it in English, he felt more emotional distance from the language, and as able to admit to himself that he wanted to end the relationship. A few weeks later, I found myself in a similar position. I was grappling with the realisation that I was a lesbian, and I couldn’t admit it to myself, I couldn’t say the word. If I said the word, life as I knew it was over. Saying the word meant ending my relationship, finding somewhere else to live, starting my life over at 27. So I thought of the Korean-Canadian man, and I turned to Ukrainian. I wrote «я лесбійка я лесбійка я лесбійка» over and over in my diary. I repeated it to myself in the mirror. I didn’t necessarily feel anything, besides the weight of premonition thudding in my chest, but Ukrainian gave me words where English failed me.

Ukrainian doesn’t feel like a void to me now. I learned to understand what actually motivates me, and it isn’t perfection. I’m motivated by human connection, I’m motivated by art and creativity, I’m motivated by feelings. I love academia, I am so passionate about my research. But learning a language because I “should” learn it is enough to make me take three years of classes, it’s enough to make me begrudgingly practice. It is enough to squeeze the bare minimum out of me, but it’s not enough to make me fall in love with the language. Falling in love with Ukrainian came from listening to the same songs on repeat for two weeks until I understood their meaning. It came from channelling my overwhelming desire to talk into talking in Ukrainian. Maybe I’m not where I should be after three years of learning a language. But each time I start a voice message with two sentences of Ukrainian, I am doing more than I was a month ago, I am letting the language be lived in instead of relegating its role in my life to a purely academic one.

Understanding Ukrainian doesn’t come from memorising tables of case endings. It comes in quiet moments. Standing on the tube platform with Ukrainian music playing in my headphones, and realising the grammar of the sentence means “are you alive?” and not “you live”. Singing in the shower and realising I’ve memorised the entire chorus of badactress’ wlw.ua without even realising. My biggest linguistic win happened a couple of days ago, once again in a tube station. I was listening to Tember Blanche’s Та Сама and I felt the lyrics of the song, felt this moment of emotion that wasn’t tied to the tone of the music, but the words themselves. For the first time, I felt emotions in Ukrainian, realised I have a favourite song in Ukrainian. Perhaps everything in life, for me, comes down to people and words and art. Perhaps those are the only motivations I know.

I’ve often heard that people have different personalities in different languages. I never developed a personality in Ukrainian, because I was a little robot memorising words without any emotion. I think I’m developing a personality now. I have retained parts of my English personality, namely my sense of humour, but my limited Ukrainian vocabulary forces me to be direct. To say what I mean instead of burying it in layers of inference. Ukrainian doesn’t have the same implications, the same baggage that English does for me. The words that flow easily into my mind in Ukrainian are sweet – compliments and appreciation. Things I find harder to say in English because I know how people will read into them. It feels easier to be affectionate in Ukrainian because words are just words. There is an obvious flaw in this logic: if I am speaking Ukrainian, I am talking to a native Ukrainian speaker. The words that are light as a feather to me probably have a tonne of implications to them. Perhaps the real test of my ability to feel emotions in Ukrainian will be when I start overthinking everything I say in Ukrainian the way I do in English, when the words begin to weigh me down with their power and their inadequacy.

Do our learned behaviours change when we switch to a different language? Will I be less anxious in Ukrainian, less of a chatterbox, less awkward? And why is my first thought that I should be less? Perhaps there are parts of me that will come alive in Ukrainian in a way they never could in English. Perhaps in Ukrainian I get to be forward, get to be open and kind without immediately anticipating rejection.

Learning Ukrainian felt like a purely academic pursuit for so long. I never though this was a language I needed to embody; a language I needed to feel emotions in outside of my research. But every emotion I have felt in Ukrainian so far has been expansive. The space to admit to myself who I am, when my native language failed me. The euphoria of understanding and relating to a song in a foreign tongue. The relief of feeling at ease in someone’s company, of being able to switch back and forth between languages without perfectionism rearing its head. The more I listen to Ukrainian music, make Ukrainian friends, read Ukrainian Instagram posts about astrology, the more this language becomes a world I inhabit instead of a duty to fulfil.

June 29, 2025

Muses and Main Character Energy

In the months before I left Glasgow, the whole city felt claustrophobic. Layers of memories lined the streets, stacked haphazardly on top of each other until my past held greater weight than the present. For a long time, my favourite thing about London was the vastness of it all. London feels endless. When I’m sad or stressed or lonely, I take the tube to a new part of the city, and walk for miles until the feelings vacate my body. There is so much left to explore.

But I’m finding new pleasures now. As I build layers of memories here, I don’t see them as ghosts, I see them as signs of life. This is what it means for a city to be lived in. It’s a beautiful sunny day. I walk from Old Street station to Columbia Road Flower Market, Taylor Swift’s Daylight playing in my headphones and sweat dripping down the back of my neck. Three days ago, I powerwalked down this same street, listening to Вечорниці as the rain soaked through my shirt. The layers begin to stack. I have lived a few lifetimes during my nine months in London, played many characters who didn’t quite feel like myself. Lately I feel as though all the pieces are clicking into place.

My favourite thing about London now is the people. Everyone I’ve met here feels like such a character. Fun characters, infuriating characters, delightfully unexpected characters. I imagine how I would write them, how I would describe their walk and their hands and the fullness of their laughter, the warmth of their hugs. Being a writer means falling in love with the humanness of it all. Humanity as a concept, yes, but also being human as a practice. Humanity that lives in the quirks and details, humanity that catches you off guard in its rawness. There is nothing I love more as an artist than having a muse.

Before I left Glasgow, I was writing a novel. I’m still writing it, technically. But it feels too disparate, there are too many parts that don’t quite slot together. The story adds up, but the characters feel hollow and the pace is erratic. So I let it be, the way I often do with my writing. I neglect my creative side and pour my energy into academia. Don’t get me wrong, I love academia. My PhD is the most important thing in my life right now. But I have always been split in half, I have always had two great loves. My PhD is finally going well, and now there is space in my brain to remember that I have barely written my novel in a year. I have barely written, yet I feel more creative than I have since my teens. Why? Because I’m surrounded by people, I’m surrounded by characters. All the characters in my novel feel flat in comparison. The more I connect with real people, the more flaws I see in my writing.

When you are depressed and isolated, it is hard to be creative. The worlds you do create end up mirroring your reality. Sparse on connection, filled with hollow characters and storylines that never quite make sense. I read the current draft of my novel, and see the emptiness I felt in Glasgow. If I took the exact same plot and wrote it for the first time now, it would be an entirely different story. But I don’t know how to rewrite it, I don’t know how to unravel the threads I have woven thus far. But the biggest issue is that this isn’t the story I need to tell anymore, and I don’t know what story I do want to tell. I have so much to say, and it doesn’t slot neatly into a fantasy novel. I look at my own life, at the characters I’m surrounded by, and imagine the story I could live in.

When we were students together, my best friend and I had a running joke that we were living in a TV show. It was often a sitcom, but had its moments of drama or downright telenovela. As with many TV shows, covid made it weird and it fizzled out to its unsatisfying end. Since starting my PhD, the show has been rebooted. The storylines are bigger and better, and I highly approve of the writers’ choice to make the main character a lesbian. I don’t know what genre my TV show is now, but it feels like I’m living in the right story for the first time in my life. The writers know the character they’re working with; they know her fatal flaws and hidden strengths, and the throwbacks to the early seasons are humorous rather than cliché. I’m learning to step into my main character energy again, to step into the spotlight instead of hiding in the shadows. But I am too much of a writer to go with the flow, I want to control the narrative.

Sometimes I wonder how I ended up in academia, with my artistic temperament. I look at the world with a novelist’s eyes. I am all romanticism and feelings and an inbuilt desire to tie the plot in a neat little bow. I don’t spend enough time around other creative people. My academic side is well-fed by now, but there is an artistic hunger within me. When I talk to creatives, I feel seen, I feel known. To be an artist is to live life as a work in progress, to understand the need to edit, to redesign, to destroy and rebuild. You know you will never reach perfection, but you claw closer towards it, inch by inch. You don’t just have a vision; you have a roadmap. Art is a practice of devotion, it’s not about the finished product, but the process of creation itself. In a world where people are increasingly outsourcing their creative tasks to AI, real art means not taking shortcuts. It means creating because you need to create, not because you want to say that you have made something.

With creativity also comes a desire to be seen. At least, a desire for your work to be seen. This visibility is part of the creative process. The way I write here is different than the way I write in my journal, because my words here are not complete until they are read. I go back and forth between wanting my writing to be seen, and wanting to remove it all from the world and kill the part of me that needs an audience. Maybe if I spent more time around other artists, I would feel less shame around wanting to be visible.