J. Mark Powell's Blog

October 19, 2025

HOLY COW! HISTORY: Unsinkable Sam, the World’s Luckiest Cat (Maybe)

You’ve heard about the Unsinkable Molly Brown, the brassy, nouveau riche millionaire miner’s wife who made it safely off the sinking Titanic. As incredible as that was, she had nothing on a remarkably feisty feline. Because he survived not one, but three separate ship sinkings … and in wartime, too, no less.

You’ve heard about the Unsinkable Molly Brown, the brassy, nouveau riche millionaire miner’s wife who made it safely off the sinking Titanic. As incredible as that was, she had nothing on a remarkably feisty feline. Because he survived not one, but three separate ship sinkings … and in wartime, too, no less.

At least, that’s the story. Listen to it and then decide for yourself.

With that, get ready to meet Unsinkable Sam, the luckiest cat in the world.

It would be all too easy to make a lame reference to a cat having nine lives. Sam must have had at least twice that many.

Very little is known about his early life. He was likely born in Germany because he wound up on a German battleship in World War II. For centuries, sailors kept cats with them on the high seas, partly for the companionship, partly to go after mice and rat stowaways on board.

And he wasn’t on just any old battleship, either. It was one of the biggest, most ferocious, and potentially deadliest of all: the mighty Bismarck. She was such a grave threat that even the dauntless and determined Winston Churchill was deeply worried.

So when she steamed out of port in May 1941, the British made destroying her Priority 1, 2, and 3.

Bismarck quickly sank the battleship HMS Hood, causing the Brits to dispatch dozens of warships to hunt her down. When she finally went to the bottom of the Atlantic on May 26, almost 2,100 crewmen went with her. British and German vessels picked up around 115 survivors.

One of them, the destroyer HMS Cossack, spotted something clinging to a piece of debris floating in the water. On closer look, they found it was a “tuxedo cat,” black with white markings on its mouth and chest. (Think of Sylvester in the old Looney Tunes cartoons.) He was the only survivor the Cossack found.

The cat switched sides that day, going over from the Axis to the Allies. Since the Cossack’s crew didn’t know his name, they called him Oscar. It’s theorized that they called him that because in the International Code of Signals, “O” means “man overboard.

Although his allegiance had changed, his luck hadn’t.

That fall, the Cossack was torpedoed by a Nazi U-boat west of Gibraltar. She sank on October 27, almost exactly five months after the Bismarck went down.

Once again, a drenched cat was seen clinging to a piece of debris and was once more hauled aboard a British warship, the HMS Ark Royal. In a neat twist of fate, that aircraft carrier had played a key role in disabling the Bismarck the previous spring.

As word of the cat’s repeated ability to cheat death on the high seas spread, folks stopped calling him Oscar and gave him a new name: Unsinkable Sam. But the plucky feline had yet another rendezvous with Fate waiting right around the corner.

This time, it was the Ark Royal that was dispatched to Davy Jones’ Locker. Barely two weeks after the Cossack’s loss, another U-boat torpedoed the mighty carrier, also off Gibraltar.

A motor launch plucked a “quite angry but otherwise unharmed” Sam from the sea. He must have been thinking, “This is getting really old!”

That was the end of Sam’s adventures. The rest of his wartime serve was quietly passed as a mouser in the Governor General’s building on Gibraltar. He eventually wound up a “Home for Sailors” in Belfast, Northern Ireland, peacefully passing away at a ripe old age in 1955.

Historians are quick to pooh-pooh the story. They claim it’s riddled with more factual holes than a piece of Swiss cheese. Serious students of World War II lump it in the “tall tales” category.

Yet, it was so widely circulated around the British Isles during the war years that it seems something involving a cat at sea must have happened.

Perhaps we’ll never know for sure. Maybe this is just one of those stories that should have been true, even if it wasn’t.

The post HOLY COW! HISTORY: Unsinkable Sam, the World’s Luckiest Cat (Maybe) appeared first on J. Mark Powell.

September 18, 2025

The Deal of a (Very Long) Lifetime

Everyone loves a bargain, a bit of financial good fortune to the buyer’s advantage. When it’s exceptionally good, we call it the deal of a lifetime. Sixty years ago, a lawyer made an arrangement that he thought would quickly reap a highly profitable windfall. But as so often happens in Holy Cow! History tales, it didn’t turn out that way.

Everyone loves a bargain, a bit of financial good fortune to the buyer’s advantage. When it’s exceptionally good, we call it the deal of a lifetime. Sixty years ago, a lawyer made an arrangement that he thought would quickly reap a highly profitable windfall. But as so often happens in Holy Cow! History tales, it didn’t turn out that way.

Our story begins in February 1875, when Nicolas and Marguerite Gilles welcomed daughter Jeanne into their well-to-do family in Arles in southern France.

For historical context, the United States was only 99 years old at the time; the telephone and electric light bulb hadn’t been invented yet, and the Statue of Liberty was still a decade away.

Nicolas was a shipbuilder, and the family lived in a coastal city on the Mediterranean. She attended private schools, painted, and played the piano. Her doting daddy brought her home for lunch each day. It was a happy, secure family environment.

In 1896, when she was 21, Jeanne married Ferdinand Calment, her double second cousin (they were related on both sides of their families) and heir to a prosperous drapery business. The young couple lived in a sumptuous apartment and had servants. Jeanne cycled, swam, played tennis, and even fenced. In January 1898, their only child, daughter Yvonne, arrived. Life was good.

Yvonne grew up, married, and had a son of her own. After she died of pleurisy on her 36th birthday, Jeanne raised her grandson.

The family survived World War I, the worldwide Great Depression, and even German occupation during World War II. In 1942, her husband (who was by then 73) died, reportedly of cherry poisoning.

Throughout all that time, Jeanne continued living in the same home. Grandson Frederic lived next and looked after her. She eased into a comfortable old age.

A fellow resident of Arles had been eyeing her beloved apartment for a long time. Andre-Francois Raffray was a real estate attorney, and he knew a good thing when he saw one. The apartment was in an excellent location and was worth a great deal of money.

So in 1965, when he was 47 and Jeanne was 90, he made an offer. He proposed an arrangement that the French call a viager contract. Raffray would pay Jeanne 2,500 francs every month (about $500 at the time); when she died, he would inherit her apartment at 2, Rue du Palais.

Raffray must have thought, “I just made the deal of the century! She’s 90 years old; she’ll die soon, and I’ll get the apartment for a pittance!”

And his scheme might have worked, too—if Jeanne Calment hadn’t been the Energizer Bunny of geriatrics. She kept going and going…

Months turned into years, and years stretched into decades. And still the payment was made each month.

By the time Raffray died in 1995 at age 77, Jeanne was 120 years old. (And Raffray’s widow was legally obligated to keep those monthly checks coming, too.)

Jeanne died two years later in 1997. Not only was she what experts call a supercentenarian, but at age 122 years and 164 days, she was the oldest person whose age could be documented.

Raffray not only picked the wrong little old lady for his offer … but he also chose the person who lived the longest in all recorded human history!

The arrangement came back to bite him on the bottom, too. Because Raffray wound up paying more than twice the apartment’s value over those 32 years. Some deal!

O. Henry and Rod Serling never wrote a better twist ending than that.

The post The Deal of a (Very Long) Lifetime appeared first on J. Mark Powell.

November 4, 2022

1948: Political Polling’s Epic Fail

It’s been a bungee jump of a year politically. Last spring the GOP seemed poised to ride a Red Tsunami in the upcoming midterm elections. Democrats rallied over the summer and appeared to have regained the momentum. This fall, however, there was a Republican resurgence with the prevailing winds now apparently blowing in its direction.

It’s been a bungee jump of a year politically. Last spring the GOP seemed poised to ride a Red Tsunami in the upcoming midterm elections. Democrats rallied over the summer and appeared to have regained the momentum. This fall, however, there was a Republican resurgence with the prevailing winds now apparently blowing in its direction.

And political pollsters were right there every step of the way telling us how this seesaw campaign season was playing out. They’re so ubiquitous, you can’t swing a dead cat without hitting some new poll result.

Love them or hate them, they are impossible to ignore. Americans are addicted to soothsayers whose algorithms tell us with what vox the populi is about to speak.

Until, of course, they get it wrong. Consider 2016. On Monday, Nov. 7, many pollsters were predicting Hillary Clinton would win the presidency by a comfortable margin. On Wednesday, Nov. 9, they were frantically wiping egg off their face.

However, nothing but nothing can compare to polling’s great failure, the Mother of All Missed Calls, the 1948 presidential election.

It was supposed to have been a no-brainer. After all, Democrats had won control of Congress in 1930. Their Franklin Roosevelt was elected president in 1932 and then reelected, and reelected, and yet again reelected. For nearly 20 years, Washington was their personal playground.

Until 1946, when Republicans seized both houses of Congress in a ballot box romp. Then the GOP turned its sights on Harry Truman.

Poor Truman. FDR would have been a hard act for any politician to follow. But a sizable number of Americans felt the Man from Missouri simply wasn’t up to the job. Tom Dewey was one of them.

The 46-year-old Republican governor of New York was viewed by many as a president in waiting. He had challenged Roosevelt in ’44 and had run a surprisingly close campaign. Dynamic and handsome (though his dark mustache had prompted GOP socialite Alice Roosevelt Longworth to dub him “the little man on the wedding cake”), his rich baritone voice sounded great on the radio.

“Dewey will be in till ’57,” one national news magazine confidently reported, taking for granted he would win 1952’s election before 1948’s was even held. Putting money on a Truman victory was a sucker bet. Poll after poll backed that up.

There had been earlier warning signs that the new science’s methodology was still a work in progress. Its most famous flop was a much-ballyhooed 1936 survey by “Literary Digest” magazine predicting Republican Alf Landon would defeat FDR in a landslide. (The Kansas governor carried only Maine and Vermont.)

With Election Day 1948 nearing Crossley, Gallup, and Roper—the country’s three leading pollsters—all agreed Dewey would win in a breeze.

They were all wrong.

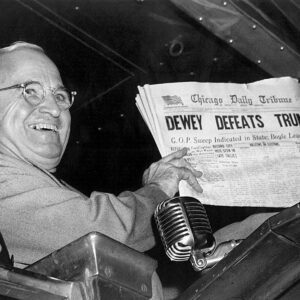

Truman narrowly eked out the biggest upset in presidential history. It was close; but close was good enough. A grinning president couldn’t help holding up a copy of the Chicago Tribune (which was so certain of a Republican sweep it had gone to press before all the votes were counted) whose iconic headline blared “Dewey Defeats Truman” for photographers.

Historians have dubbed 1948 an utter fiasco for political polling. So, just what went wrong?

Plenty. For starters, interviewers were allowed back then to pick their own respondents without demographic screening first. Talk to too many Democrats or too many Republicans and the results were skewered.

There was also bad timing. As George Gallup, Jr. later recalled, “We stopped polling a few weeks too soon.” That’s right; Dewey seemed such a lock to win many pollsters simply didn’t feel the need to waste resources confirming what everyone knew was going to happen.

Finally, there was the FDR Factor. The leading pollsters of the era had cut their teeth during the New Deal’s long run. Roosevelt was a deeply polarizing figure with people either passionately loving or furiously hating him.

But in 1948 not only was Roosevelt gone, there were also four presidential candidates: Dewey, Truman, Dixiecrat Strom Thurmond, and Progressive Henry Wallace. Their old “what do you think of him?” approach simply didn’t work in that dynamic.

Taken together, those problems combined to create a perfect storm for wildly off-the-mark forecasts.

It was such a disaster Harry Truman became the patron saint for underdogs everywhere. “Look how he was underrated in ’48!” they still note with a whiff of desperation. Political pros have a rule of thumb that says whenever a candidate invokes Harry Truman in the closing days of a campaign, that candidate will have an unhappy election night.

It was such a disaster Harry Truman became the patron saint for underdogs everywhere. “Look how he was underrated in ’48!” they still note with a whiff of desperation. Political pros have a rule of thumb that says whenever a candidate invokes Harry Truman in the closing days of a campaign, that candidate will have an unhappy election night.

And so it is ironic that the candidate who proved pollsters wrong by pulling off the greatest come-from-behind win of all time is now a St. Jude for political lost causes.

Did you find this enjoyable? Please continue to join me each week, and I invite you to read Tell it Like Tupper and share your review!

Curious about Tell It Like Tupper? See for yourself. Take a sneak peek at a couple of chapters in this free downloadable excerpt.

The post 1948: Political Polling’s Epic Fail appeared first on J. Mark Powell.

October 9, 2022

7 Sisters and 37 Feet of Hair

There’s no delicate way to say this, so here goes. Your great-great-grandparents had a weird thing about hair.

The Victorians were obsessed with lovely locks. People have always admired a nice head of hair. But Victorians were bonkers for beautiful tresses.

They snipped strands of dead loved ones’ hair for keepsakes. They put their locks inside lockets and photo cases for paramours. And they made hair jewelry. Seriously, it was a thing. They wove it into bracelets, brooches, watch fobs, and more.

Decades before the musical “Hair” took Broadway by storm, a musical group swept the country at the height of hair’s heyday and, in turn, peddled a concoction that made a fortune. This is the story of seven sisters and their combined 37 feet of hair.

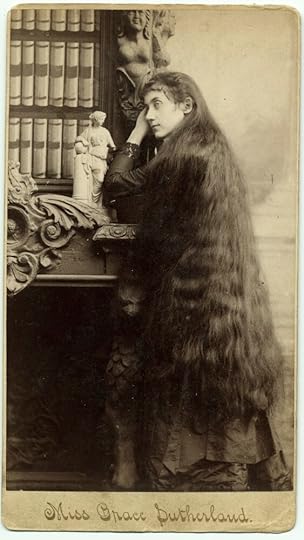

Life wasn’t easy on the Sutherland family’s turkey farm in Niagara County, N.Y. Fletcher Sutherland was like Pa Kettle, a lazy ne’er-do-well content to let everyone else do his work for him. Daughters Sarah, Victoria, Isabella, Grace, Naomi, Dora, and Mary herded the birds barefoot and in dingy dresses. Smooth-talking Papa Sutherland preferred preaching and politicking and basically anything (apart from manual labor) that let him flap his jaw.

His daughters were so ashamed of their appearance they hid when company called, especially after their longsuffering mother died in 1867.

But one thing set the Sutherland sisters apart. Their remarkably long, lovely hair which they grew to their waist and beyond. People raved about it.

Their mother had drenched their heads with a foul-smelling mixture she cooked up to make their hair luxuriously beautiful. It smelled so bad kids wouldn’t sit beside them in school. When the mom passed away, the odious ointment went to the grave with her.

The girls (along with brother Charles) began playing musical instruments and singing. Their daddy, always looking for a chance to make a quick buck, booked them at churches.

Soon, the act became the talk of Upstate New York. Musically, it was nothing special. The kids weren’t bad; they weren’t great, either. But people weren’t coming to hear their songs. Folks flocked to see their incredible hair.

Fletcher Sutherland knew a good thing when he saw it. He billed the sisters as “The Seven Wonders.” (Brother Charlie was given the boot; there was no interest in an adolescent boy with average hair). By December 1880 they reached Broadway where audiences gazed admiringly at the girls’ combined total of 37 feet of hair.

The act began with the sisters sporting braids atop their heads. The highlight came when they turned their backs and unpinned it, unleashing a tidal wave of hair. Caught in glowing gaslight, crowds gasped in amazement at the wondrous sight. Victoria fascinated showgoers the most with her seven feet of hair. Mary was the slacker with a mere three feet.

In 1884 they hit the big time: A sideshow with Barnum and Bailey’s Circus, “The greatest show on Earth.” P.T. Barnum promoted them as, “The seven most pleasing wonders of the world.”

The sisters were different from their colleagues. They weren’t viewed as “circus people” shunned by polite society. They conducted themselves as dignified proper ladies. Though his girls were now bona fide celebrities, it still wasn’t enough to satisfy their father’s voracious greed.

So Fletcher Sutherland partnered with promoter Harry Bailey, distant cousin of the Bailey in Barnum and Bailey. They resurrected Ma Bailey’s hair ointment, changing the formula so it wasn’t so disgusting smelling. Soon “The Seven Sutherland Sisters Hair Grower” was being sold.

They got a chemist to write, “I hereby certify that I found it free from all injurious substances … and I cheerfully endorse it.” In the days before the FDA, that was good enough for gullible consumers. By 1884 the company had raked in $90,00 in sales (about $2.7 million today).

Sutherland was a wealthy man when he died in 1885. The sisters gradually got involved in the company and proved themselves shrewd businesswomen. They expanded the product line to include brushes and other hair-related products, all marketed to upper-class women who could afford their extravagant prices. By 1890, their Hair Grower (also sold as “Hair Fertilizer”) had sales of $3 million (around $97.6 million in 2022).

The sisters married, started families, and became eccentrics. They lived together in a gaudy 14-room mansion built on the family farm. Despite their facade of Victorian respectability, behind closed doors, they would have been “The Real Housewives of Cambria, New York.” There was alcoholism, complicated extramarital affairs, and even whispers about witchcraft—enough fodder for a tabloid.

Naomi died suddenly in 1893 before turning 40, dramatically shaking the surviving sisters. They toured on and off with Barnum until 1907. But the 20th century’s arrival saw Americans’ fascination with hair rapidly fading. Sales of their products plunged as extravagant living caught up with them.

Desperate for cash, the last three sisters went to Hollywood in 1919 on a trip so disastrous that not only did a movie deal fall through but Dora was killed in a car crash. Things only got worse from there.

The mansion was sold in 1931 (burning in 1938); the hair business went belly-up in 1936; Mary died in an insane asylum in 1939; and when Grace, the final sister, passed away in 1946 at age 92 she was dirt poor.

The mansion was sold in 1931 (burning in 1938); the hair business went belly-up in 1936; Mary died in an insane asylum in 1939; and when Grace, the final sister, passed away in 1946 at age 92 she was dirt poor.

In the end, the Sutherland Sisters wound up right back where they had started.

Did you find this enjoyable? Please continue to join me each week, and I invite you to read Tell it Like Tupper and share your review!

Curious about Tell It Like Tupper? See for yourself. Take a sneak peek at a couple of chapters in this free downloadable excerpt.

The post 7 Sisters and 37 Feet of Hair appeared first on J. Mark Powell.

September 15, 2022

An Earlier Rail Strike’s Close Call

Labor contract negotiations often come down to a game of chicken. Negotiators on both sides go as close to the deadline as they dare until someone blinks. The higher the stakes, the closer to the edge each camp is willing to go. They can make the Cuban Missile Crisis look like child’s play.

Labor contract negotiations often come down to a game of chicken. Negotiators on both sides go as close to the deadline as they dare until someone blinks. The higher the stakes, the closer to the edge each camp is willing to go. They can make the Cuban Missile Crisis look like child’s play.

We were reminded of that with this week’s narrowly averted rail shutdown. Less than 48 hours before passengers and freight trains were scheduled to grind to a halt, threatening to cripple an already battered supply chain still reeling from the pandemic, a tentative deal was reached. November’s looming midterm elections played no small part in the urgency as well.

It was dramatic stuff. Yet it was nothing compared to the decisive (and almost theatrical) role a president played in an even more ominous rail strike 76 years earlier.

In 1946, railroads were the backbone of the world’s largest transportation system. The federal interstate highway system was still just a dream. Air cargo was in its infancy. Though trucks and barges moved many things, the yeoman’s duty was done by trains. If it was sent in America at that time, it went by rail.

When the people who kept the country’s iron horses rolling threatened to walk off the job in 1946, a major catastrophe was in the making. The nation was still undergoing the painful transition from wartime to a peacetime economy. Major unions had made a no-strike pledge for the duration of the conflict, and they had kept it.

Now that bombs had stopped falling, prices were shooting up. Inflation was having a field day, making up for the hiatus it had taken the war years. Railroad workers, like many other Americans, said they simply couldn’t keep up.

Labor was on the warpath just then. Steelworkers, telephone workers, meatpackers, and General Electric laborers—some 5 million people in all—were walking the picket line. If the railroad workers joined them, it would be one strike too many.

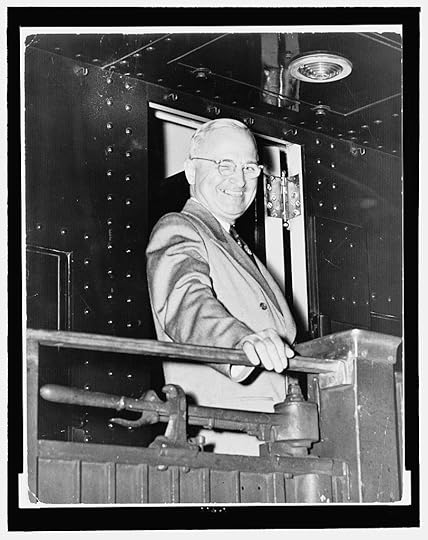

President Harry Truman, who was ending his first year on the job, was increasingly frustrated. Labor Secretary Lewis Schwellenbach had been his personal emissary for months as he keep representatives from railway management and 20 different unions talking.

His patience finally gave out, and Truman invoked the Railway Labor Act imposing a 60-day cooling-off period. Though some progress was made, two unions still refused to budge.

A strike was set for May 18, 1946.

Truman had been pushed too far. On May 17, he signed Executive Order 9727 authorizing the federal government to seize control of, and operate, the nation’s railroads. Truman had more than upped the ante; he had pushed all the chips to the middle of the table and was going for broke.

Labor leaders took a step back the next day, postponing the strike for five days.

On May 22, Truman proposed giving rail workers an 18.5 cent hourly raise ($2.81 in today’s dollars). The unions’ reply: A firm, “No, that’s not enough.”

And so on May 24, while Truman was shaking hands with 865 wounded World War II veterans at a special reception on the south lawn of the White House, the strike began. Its effects were instantaneous.

America was largely paralyzed. Thousands of travelers were stranded wherever they happened to be when the trains stopped running. Auto traffic became tangled. Without railcars to carry crops, farm harvesting froze. Newspapers, the main communications outlet of the day, cut back coverage to conserve their supply of newsprint. The Atlanta Constitution only ran notices of funerals and lodge meetings and promised its readers with a whiff of desperation it wouldn’t stop publishing if it was “humanly possible to avoid it.”

Truman was a skilled poker player. He recognized the unions believed his seizure of the railroads was bluffing. They had called his bluff. And they called wrong. The president pounced.

He spoke to the nation by radio that night, urging rail workers to return to their jobs for the good of the country.

Then, in one of the most dramatic moments in congressional history, Truman went to Capitol Hill the next day to address a special joint session. Getting the House and Senate to meet on a Saturday was a big deal itself. But everyone understood this can couldn’t be kicked down the road.

Truman stepped to the rostrum at 4:00 p.m. and recounted all he had done to prevent that moment from happening, saying “the time for negotiation had passed and the time for action had arrived” and adding in his no-nonsense way, “We are dealing with a handful of men who have it within their power to cripple the entire economy of the nation.”

The air at electric. Truman asked Congress to give him special authority for six months to draft strikers into the armed forces and put them in the service of the government. Harry wasn’t fooling around.

At that precise moment Leslie L. Biffle, Secretary of the Senate, stepped over and handed Truman a slip of paper. The president paused as he read it, looked up, and said, “Word has just been received that the railroad strike has been settled on terms proposed by the president!”

The news was greeted with more than applause; a tidal wave of whooping, hollering, and cheers swept through the chamber as 535 senators and representatives heaved a collective sigh of relief. A national tragedy had been averted.

Yes, the 11th-hour agreement that preempted a 2022 rail strike was indeed dramatic. But it can’t hold a candle compared to what happened in 1946.

Yes, the 11th-hour agreement that preempted a 2022 rail strike was indeed dramatic. But it can’t hold a candle compared to what happened in 1946.

Did you find this enjoyable? Please continue to join me each week, and I invite you to read Tell it Like Tupper and share your review!

Curious about Tell It Like Tupper? See for yourself. Take a sneak peek at a couple of chapters in this free downloadable excerpt.

The post An Earlier Rail Strike’s Close Call appeared first on J. Mark Powell.

May 29, 2021

Grandma Gatewood’s Excellent Adventure

I’ve been getting into shape recently. But my progress pales compared to what a remarkable senior did nearly 70 years ago.

I’ve been getting into shape recently. But my progress pales compared to what a remarkable senior did nearly 70 years ago.

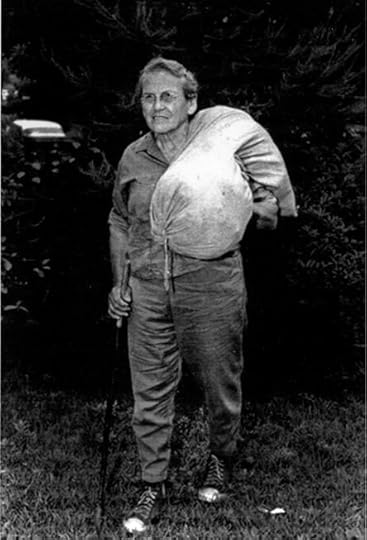

Emma Gatewood’s life was hard. Born in Ohio in 1887, she was one of 15 kids in a family that slept four to a bed. Her father lost a leg in the Civil War and spent the rest of his life drinking and gambling. Though her formal education ended in the 8th grade, she kept learning by devouring encyclopedias, Greek classics, and books on woods and wildlife.

At age 19 Emma married a 27-year-old teacher and tobacco farmer named P.C. Gatewood. The honeymoon ended quickly, when Emma discovered she was expected to work in the fields alongside the men, plus cook, clean, and raise their 11 kids.

P.C. was mean. He killed a man in 1924 but avoided prison because the judge said his many children would go hungry with him behind bars.

He beat Emma often, sometimes almost to the point of death. When he turned violent, she tried to run into nearby woods. Safe in the security of her beloved trees and plants, she found peace and solitude.

P.C. repeatedly threatened to send Emma to a mental institution to keep her from divorcing him. In 1939, he had her jailed in the first step toward having her committed. Seeing Emma’s cracked teeth and broken ribs, their town’s mayor moved her into his home and helped her get a job. She divorced P.C. the next year. A series of odd jobs saw her through the next decade until her children were all grown.

Then, as so often happens, fate unexpectedly called. For Emma, it came in the form of an old magazine. She happened upon a 1949 National Geographic issue featuring an article on the Appalachian Trail. At that moment an incredible idea took root in her mind. She would become the first woman to walk the entire length of the trail, all 2,200 miles from Springer Mountain in Georgia to Maine’s Mount Katahdin.

At age 66, no less.

The idea grew into an obsession. At a time when people nearing 70 were expected to relax in rocking chairs, Emma began preparing to attempt what no woman before had ever done. Her legs were strong, she was in good health, so why not?

She began her journey at Mount Katahdin in July 1954 — and promptly met with one disaster after another. She broke her glasses, she got lost, then she ran out of food. When rangers found her, they persuaded the hapless sexagenarian to go home.

But while Emma Gatewood may have failed, she didn’t quit. She told no one about her setback and quietly prepared for a second attempt. She learned from her initial mistakes and changed her strategy.

In 1955, she started two months earlier this time and began in Georgia. Again, it wasn’t easy. That 1949 article had made her believe the route was a smooth trail. It wasn’t, and her Keds tennis shoes were no match for the rugged mountain terrain. She expected to find shelters along the way; there weren’t any, forcing her to sleep in piles of leaves.

But she stuck with it and kept walking. Newspapers picked up her story as she went, and soon she acquired a nickname—Grandma Gatewood—along with celebrity status.

She achieved her goal 146 days later when she reached Baxter Peak atop Mount Katahdin. She signed the register, sang “America the Beautiful,” and said to herself out loud, “I did it. I said I’d do it, and I’ve done it.”

Grandma Gatewood then appeared on the Today show, was a guest on a TV game show, and was even profiled in Sports Illustrated where she said, “This is no trail. It’s a nightmare. For some fool reason, they always lead you right up over the biggest rock on top of the highest mountain they can find.”

And she didn’t stop walking. She hiked the entire Appalachian Trail a second time two years later, walked all 2,000 miles of the Oregon Train in 1959, and at age 76 she did the Appalachian Trial yet again (though this time in sections), becoming the first person to walk it three times. She went right on hiking right up until her death in 1973 at 85.

What was the secret to her success? Grandma Gatewood refused to let anything—failure, adversity, or advanced age—stand in her way.

What was the secret to her success? Grandma Gatewood refused to let anything—failure, adversity, or advanced age—stand in her way.

Did you find this enjoyable? Please continue to join me each week, and I invite you to read Tell it Like Tupper and share your review!

Curious about Tell It Like Tupper? See for yourself. Take a sneak peek at a couple of chapters in this free downloadable excerpt.

The post Grandma Gatewood’s Excellent Adventure appeared first on J. Mark Powell.

August 15, 2020

Young George and That Cherry Tree

Keeping all of February’s presidential birthdays straight is a big headache. Ronald Reagan was born on February 6. William Henry Harrison on the 9. Lincoln arrived on the 12th. And president Numero Uno, George Washington, was born February 22. Congress washed its hands of the mess by lumping them all together in the Presidents Day holiday.

Keeping all of February’s presidential birthdays straight is a big headache. Ronald Reagan was born on February 6. William Henry Harrison on the 9. Lincoln arrived on the 12th. And president Numero Uno, George Washington, was born February 22. Congress washed its hands of the mess by lumping them all together in the Presidents Day holiday.

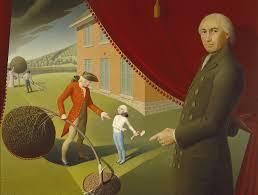

Chances are you grew up hearing George Washington chopped down a cherry tree as a 6 year-old-boy. When his dad asked who was responsible, the future Father of Our Country ‘fessed up and said, “I cannot tell a lie, I did it with my little hatchet.” It’s a story that inspired countless generations of kids to always tell the truth.

Yet it never happened.

That’s right, the tale extolling the virtues of honesty is a lie. And get this—it was even spun by a man of the cloth! Here’s the story.

Back in our country’s infancy, early Americans hungered for heroes. We’d just broken free from Britain, so England’s history no longer appealed on this side of the pond.

Back in our country’s infancy, early Americans hungered for heroes. We’d just broken free from Britain, so England’s history no longer appealed on this side of the pond.

George Washington perfectly fit the bill. He had held the Continental Army together by sheer force of will, saving the Patriot cause along with it. Tall and imposing, he looked and acted like a successful general. He added to his reputation by getting one of the world’s first republics since ancient Rome up and running. Then, most astonishingly of all, at the very summit of his career when he could have been anything he wanted—king, emperor, or dictator—he did the unthinkable: he walked away from power and went home. In doing so, he left a legacy that’s still practiced nearly 225 years later.

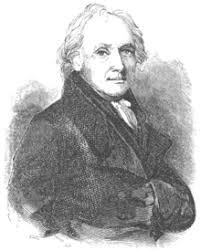

But all that wasn’t good enough for Parson Weems.

To say Mason Locke Weems was a fan of George Washington is an understatement. His adoration for the first president bordered on obsession. He was, in modern sports terms, a Super Fan.

To say Mason Locke Weems was a fan of George Washington is an understatement. His adoration for the first president bordered on obsession. He was, in modern sports terms, a Super Fan.

Born and raised in Maryland, Weems was ordained in the Protestant Episcopal Church just after the Revolution. Needing a sideline to supplement is meager income, he first sold and then wrote books. He eventually settled as pastor of a parish in Lorton, Virginia, not far from Washington’s home. Weems later padded his resume by claiming he had served as rector of the Mount Vernon parish, which wasn’t true.

After Washington’s death in December 1799, people craved information about that remarkable man’s life. So Parson Weems happily filled the void. Unfortunately, he couldn’t resist the temptation to make a good story better. Like a fisherman’s yarn about the one that got away, his tales kept getting bigger and bigger. His crowning jewel was the cherry tree incident, which he claimed to have heard from an elderly woman who had known the young Washington’s family.

After Washington’s death in December 1799, people craved information about that remarkable man’s life. So Parson Weems happily filled the void. Unfortunately, he couldn’t resist the temptation to make a good story better. Like a fisherman’s yarn about the one that got away, his tales kept getting bigger and bigger. His crowning jewel was the cherry tree incident, which he claimed to have heard from an elderly woman who had known the young Washington’s family.

(Full disclosure: my Powell ancestors’ farm bordered the Washington’s plantation in Stafford County, Virginia where the cherry tree incident allegedly occurred. But I won’t let that family connection obscure my journalistic objectivity.)

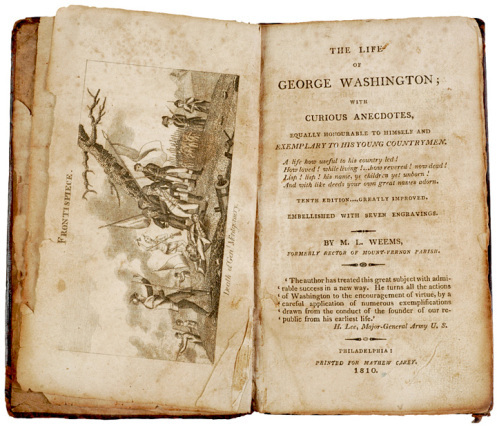

Young George, his little hatchet, the downed cherry tree, and the famous “I cannot tell a lie” line first appeared in the fifth edition of Weems’ book, The Life of George Washington. The passage was a show-stealer. It was the part everyone talked about. So much so, other writers accepted it as fact and included it in their Washington biographies. Even the legendary McGuffey Reader passed it on to countless students for decades.

Young George, his little hatchet, the downed cherry tree, and the famous “I cannot tell a lie” line first appeared in the fifth edition of Weems’ book, The Life of George Washington. The passage was a show-stealer. It was the part everyone talked about. So much so, other writers accepted it as fact and included it in their Washington biographies. Even the legendary McGuffey Reader passed it on to countless students for decades.

By the end of the 19th Century, historians began expressing doubts. Woodrow Wilson’s 1896 Washington biography came right out and called the tale a fabrication. There has been exhaustive research into it ever since, and the most charitable conclusion that can be drawn is there’s no way of proving whether it happened. Which is a far cry from saying it did.

By the end of the 19th Century, historians began expressing doubts. Woodrow Wilson’s 1896 Washington biography came right out and called the tale a fabrication. There has been exhaustive research into it ever since, and the most charitable conclusion that can be drawn is there’s no way of proving whether it happened. Which is a far cry from saying it did.

I’m a traditionalist and am usually inclined to give questionable historic incidents the benefit of the doubt. But not this time. Parson Weems seems to have had a very casual relationship with honesty. He wrote several books about America’s early leaders and stretched the truth in all of them. Like, a lot.

So go ahead and eat a cherry pie George’s birthday next February if you wish. Because regardless of what may or may not have happened when Washington was a child, one thing is certain: I swear cherry pies are delicious. I cannot tell a lie.

So go ahead and eat a cherry pie George’s birthday next February if you wish. Because regardless of what may or may not have happened when Washington was a child, one thing is certain: I swear cherry pies are delicious. I cannot tell a lie.

Did you find this enjoyable? Please continue to join me each week, and I invite you to read Tell it Like Tupper and share your review!

Curious about Tell It Like Tupper? See for yourself. Take a sneak peek at a couple of chapters in this free downloadable excerpt.

The post Young George and That Cherry Tree appeared first on J. Mark Powell.

July 31, 2020

The Woman Who Kissed Hitler

We’ve all done something impulsive at one time or another. A spur of the moment decision that, when you thought about it later, wasn’t such a good idea. Nearly 90 years ago an American woman acted rashly, and her action involved history’s worst monster. Here’s the story of the woman who kissed Hitler.

We’ve all done something impulsive at one time or another. A spur of the moment decision that, when you thought about it later, wasn’t such a good idea. Nearly 90 years ago an American woman acted rashly, and her action involved history’s worst monster. Here’s the story of the woman who kissed Hitler.

In many ways, George and Carla De Vries were typical American tourists vacationing in Europe. The Norwalk, California dairy farmers did what many of their countrymen did that year and seized on the upcoming Summer Olympic Games as the perfect opportunity to see the Continent.

But this wasn’t any ordinary Olympiad. Because the 1936 Games were held in Berlin, capital of Nazi Germany. The swastika flew above Olympic Stadium. And hovering over it all was the official host, Adolf Hitler.

But this wasn’t any ordinary Olympiad. Because the 1936 Games were held in Berlin, capital of Nazi Germany. The swastika flew above Olympic Stadium. And hovering over it all was the official host, Adolf Hitler.

In fairness to the de Vries, at that particular moment Hitler seemed like just another bad guy to many people. A really bad guy, perhaps. But there were plenty of them in Europe at that time. Stalin, Mussolini, Franco, and lots of lesser tyrants as well. The Third Reich’s worst horrors were yet to come. World War II and the Holocaust were still several years away. The Nazis were on their best behavior just then, too. They toned down their hate-filled rhetoric, plastered fake smiles on their faces, and built shiny massive venues to host athletic competitions. The Reich’s leaders hoped to use the games to showcase their racial superiority claptrap, though that didn’t turn out as they had planned.

George and Carla were among the large crowd (estimates are as high as 30,000 people) watching swimming contests on August 15. Hitler had a ringside seat. The men’s 1500m freestyle event had just wrapped up. Carla asked guards if Der Fuhrer would autograph her Olympic ticket. During a break in the action, she was escorted to his seat.

George and Carla were among the large crowd (estimates are as high as 30,000 people) watching swimming contests on August 15. Hitler had a ringside seat. The men’s 1500m freestyle event had just wrapped up. Carla asked guards if Der Fuhrer would autograph her Olympic ticket. During a break in the action, she was escorted to his seat.

Hitler seemed to be having one of his rare pleasant days. Carla handed him the ticket, which he obligingly signed and returned.

Then an idea popped into her head and she pounced. Literally. The 40-year-old lunged over the railing and tried to kiss the dictator. Hitler pulled back, grinning from ear to ear like an awkward schoolboy.

Then an idea popped into her head and she pounced. Literally. The 40-year-old lunged over the railing and tried to kiss the dictator. Hitler pulled back, grinning from ear to ear like an awkward schoolboy.

Carla lunged again. This time her lips grazed the Fuhrer’s cheek. Hitler wheeled away, still grinning stupidly through a shellshocked expression.

Security guards grabbed Carla. As they led her off, thousands of people who witnessed the scene cheered wildly. “I think we’d better get out of here,” she told George, who agreed. They lost no time returning to their hotel. Carla had, after all, just made people laugh at the one person in Nazi Germany you didn’t make fun of.

Security guards grabbed Carla. As they led her off, thousands of people who witnessed the scene cheered wildly. “I think we’d better get out of here,” she told George, who agreed. They lost no time returning to their hotel. Carla had, after all, just made people laugh at the one person in Nazi Germany you didn’t make fun of.

Back at his palatial office inside the Reich Chancellery later that day, Hitler was furious. How could his SS bodyguards have failed so terribly? What if the woman had lunged at him with a gun, or a grenade, or a knife? It had been a major security lapse. There was a huge shakeup in Hitler’s detail. Some officers were fired, others demoted.

The moment was caught on film. But the Nazis censored it, preventing most Germans from learning what had happened. Yet, the Olympics is an international gathering after all and stories about it ran in newspapers around the world, including The New York Times.

The moment was caught on film. But the Nazis censored it, preventing most Germans from learning what had happened. Yet, the Olympics is an international gathering after all and stories about it ran in newspapers around the world, including The New York Times.

Why did Carla do it? As she said afterward, “It’s just that I’m a woman of impulses, I guess … I don’t know why I did it. Certainly, I hadn’t planned such a thing.”

The 1936 Olympics wasn’t Carla’s only brush with fame. She was in the news later for preventing a patient in a mental institution from committing suicide, and again when her husband’s dairy dealt with a labor strike.

Still, there was one moment in her life she was asked about over and over. “Come on, Grandma, tell us about the time you kissed Hitler.” She went right on telling the tale until her death in 1985 at age 92. It was a tale, however, no one envied.

The censored film clip surfaced a few years ago. Although the affair lasted less than ten seconds, it shows the man who brought misery to millions made to squirm. There is a small measure of retribution in that.

The censored film clip surfaced a few years ago. Although the affair lasted less than ten seconds, it shows the man who brought misery to millions made to squirm. There is a small measure of retribution in that.

Did you find this enjoyable? Please continue to join me each week, and I invite you to read Tell it Like Tupper and share your review!

Curious about Tell It Like Tupper? See for yourself. Take a sneak peek at a couple of chapters in this free downloadable excerpt.

The post The Woman Who Kissed Hitler appeared first on J. Mark Powell.

July 17, 2020

Before Camp David, There Was Camp Hoover

President Trump loves hanging out at Mar-a-Lago, his luxury Florida estate. He’s less fond of Camp David, the chief executive’s official getaway in the Maryland mountains. He once called the place “interesting for about 30 minutes.”

President Trump loves hanging out at Mar-a-Lago, his luxury Florida estate. He’s less fond of Camp David, the chief executive’s official getaway in the Maryland mountains. He once called the place “interesting for about 30 minutes.”

Every president since FDR has spent time at the presidential retreat. Yet 13 years before Camp David was created another presidential property was built in Virginia’s Shenandoah Valley.

This is the story of Camp Hoover.

Herbert Hoover is remembered for the extraordinarily bad luck of having the Great Depression start on his watch, the kind of thing that looks terrible on a presidential resume. But when he entered office in 1929 he was quite popular. The first president born and raised west of the Mississippi, Hoover had spent years living in mining camps as an engineer. The outdoors appealed to this most buttoned-down of presidents.

Herbert Hoover is remembered for the extraordinarily bad luck of having the Great Depression start on his watch, the kind of thing that looks terrible on a presidential resume. But when he entered office in 1929 he was quite popular. The first president born and raised west of the Mississippi, Hoover had spent years living in mining camps as an engineer. The outdoors appealed to this most buttoned-down of presidents.

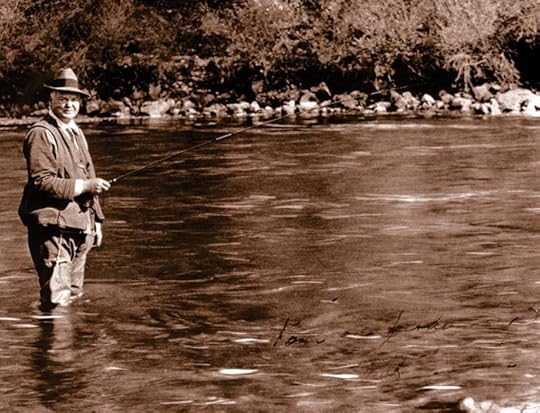

Shortly after Hoover moved into the White House, he found the perfect location for escaping it. A getaway at the Rapidan River’s headwaters atop Doubletop Mountain. Nearby Mill Prong and Laurel Prong streams offered ideal fishing. (Hoover was an avid angler, though also the kind of guy who fished while wearing a coat and tie.)

Virginians offered the land for free. But Hoover wouldn’t hear of it. He insisted on personally paying the prevailing $5 an acre for 164 pristine acres, plus another $22,719 for materials. U. S. Marines provided free labor by labeling the construction project a “military exercise.” They built 13 buildings including cabins, two mess halls, a lodge, a meeting place, and Hoover’s residence called the Brown House (to distinguish it from the White House). There were hiking trails, a miniature golf course, and trout pools where it was said the fish were so tame “they drift slowly out into the open to look you over.”

Virginians offered the land for free. But Hoover wouldn’t hear of it. He insisted on personally paying the prevailing $5 an acre for 164 pristine acres, plus another $22,719 for materials. U. S. Marines provided free labor by labeling the construction project a “military exercise.” They built 13 buildings including cabins, two mess halls, a lodge, a meeting place, and Hoover’s residence called the Brown House (to distinguish it from the White House). There were hiking trails, a miniature golf course, and trout pools where it was said the fish were so tame “they drift slowly out into the open to look you over.”

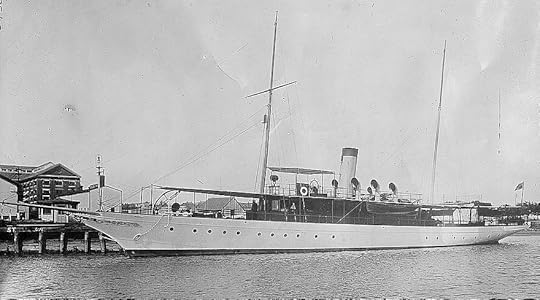

Hoover decommissioned the presidential yacht Mayflower and reassigned its mess crew and china to the camp to save money. Its official name was Rapidan Camp. But everybody called it Camp Hoover.

Hoover decommissioned the presidential yacht Mayflower and reassigned its mess crew and china to the camp to save money. Its official name was Rapidan Camp. But everybody called it Camp Hoover.

It was so rustic, mail was delivered by dropping it from an airplane!

That didn’t stop the era’s Who’s Who from trekking there. Visitors included Thomas Edison, Edsel Ford, Governor Theodore Roosevelt, Jr., Winston Churchill, and even British Prime Ramsay Minister McDonald. In a move foreshadowing Camp David’s later role as a place for delicate diplomatic negotiations, Hoover used it as the place to offer this deal: Washington would cancel Britain’s World War I debt in exchange for America buying Bermuda, Trinidad, and British Honduras. (McDonald’s reply: “Thanks, but no thanks.”)

In August 1929 Hoover’s doctor met a mountain boy while hiking through nearby woods. They struck up a conversation. The doctor was horrified to discover the child, nor his eight brothers and sisters, had ever attended school. Because there wasn’t one nearby. The boy and some friends rode horses into Camp Hoover a few days later and gave the president a live possum as a birthday gift. (Anne Morrow Lindbergh, visiting with husband Charles, was amused to learn the kids had never heard of the world-famous aviator.) Hoover was touched and personally funded a small school for local poor children.

In August 1929 Hoover’s doctor met a mountain boy while hiking through nearby woods. They struck up a conversation. The doctor was horrified to discover the child, nor his eight brothers and sisters, had ever attended school. Because there wasn’t one nearby. The boy and some friends rode horses into Camp Hoover a few days later and gave the president a live possum as a birthday gift. (Anne Morrow Lindbergh, visiting with husband Charles, was amused to learn the kids had never heard of the world-famous aviator.) Hoover was touched and personally funded a small school for local poor children.

Camp Hoover’s glory days didn’t last long. Defeated for reelection in 1932, Hoover gave the camp to the government. Franklin Roosevelt visited in 1933 but didn’t like it; the trails couldn’t handle his wheelchair and the water was too cold for swimming.

The Boy Scouts used the place from 1946 until the early 60s. By then many of its cabins had rotted.

Still, VIPs kept coming. Jimmy Carter was the first president since FDR to visit; when his vice president Walter Mondale was trapped there in a snowstorm the Secret Service needed chainsaws to get him out. Al Gore also dropped by when he was Veep.

Still, VIPs kept coming. Jimmy Carter was the first president since FDR to visit; when his vice president Walter Mondale was trapped there in a snowstorm the Secret Service needed chainsaws to get him out. Al Gore also dropped by when he was Veep.

The National Park Service finally restored the three remaining cabins (including the Brown House) in 2004 and renamed it Rapidan Camp. You can visit it today, either by hiking on foot or riding by van from a nearby visitor center. Those who do relive a forgotten piece of presidential history in the same surroundings Herbert and Lou Hoover enjoyed nearly 90 years earlier.

The National Park Service finally restored the three remaining cabins (including the Brown House) in 2004 and renamed it Rapidan Camp. You can visit it today, either by hiking on foot or riding by van from a nearby visitor center. Those who do relive a forgotten piece of presidential history in the same surroundings Herbert and Lou Hoover enjoyed nearly 90 years earlier.

Did you find this enjoyable? Please continue to join me each week, and I invite you to read Tell it Like Tupper and share your review!

Curious about Tell It Like Tupper? See for yourself. Take a sneak peek at a couple of chapters in this free downloadable excerpt.

The post Before Camp David, There Was Camp Hoover appeared first on J. Mark Powell.

July 11, 2020

Fort Blunder

We all make mistakes. To err is human, after all. For example, flowers sometimes get inadvertently planted or fences built on the wrong side of the property line. It’s an imperfect world after all.

We all make mistakes. To err is human, after all. For example, flowers sometimes get inadvertently planted or fences built on the wrong side of the property line. It’s an imperfect world after all.

When armies and nations make such a faux pas, war can result. Fortunately, that didn’t happen with this week’s tale. Although the story does begin with a war. Two of them, in fact.

We know Canada today as a mellow place, a country famous for its politeness and good manners (along with trying to stay warm half of the year). But that wasn’t always the case.

When the American colonies launched the Revolutionary War, our neighbor to the north stayed loyal to England. Twice, (during the Revolution and again 37 years later during its sequel, the War of 1812) the U.S. invaded Canada. Twice, we had our fanny handed to us on a platter. And, as my Canadian friends in college were fond of gleefully pointing out, “We burned your White House, too!”

When the American colonies launched the Revolutionary War, our neighbor to the north stayed loyal to England. Twice, (during the Revolution and again 37 years later during its sequel, the War of 1812) the U.S. invaded Canada. Twice, we had our fanny handed to us on a platter. And, as my Canadian friends in college were fond of gleefully pointing out, “We burned your White House, too!”

After narrowly surviving the War of 1812, President James Madison said it was time to seriously invest in defense spending. Since a fort had famously stopped the British fleet at Baltimore (giving us The Star-Spangled Banner in the process), the War Department set about building a string of fortifications along the Atlantic coast, many of which still stand today.

An imposing fort was planned to protect America from Canada as well. Money was authorized to build an 8-sided fortification with 30 foot stone walls and armed with 125 powerful cannons. It would be built in New York state on the northern end of Lake Champlain within sight of the border. Twice during both wars, the British had used that waterway to launch their own invasions of our country. Once the new fort was in place, no warship could get past it.

So the Army set to work building the new fortress in 1816. Dozens of workmen and soldiers, overseen by the Corps of Engineers, commenced the mighty task. It was so important, President James Madison even inspected the site in 1817. Things were progressing nicely. Dozens of acres of woods had been cleared and the massive stone walls were going up.

So the Army set to work building the new fortress in 1816. Dozens of workmen and soldiers, overseen by the Corps of Engineers, commenced the mighty task. It was so important, President James Madison even inspected the site in 1817. Things were progressing nicely. Dozens of acres of woods had been cleared and the massive stone walls were going up.

Then it happened. A clerk in Washington discovered a mistake. A bad mistake. A make-your-face-turn-red and hang-your-head-in-shame mistake.

The survey that had been used to select the new fort’s site was wrong. Way wrong. It mistakenly placed the international border three-quarters of a mile to the south. Meaning the fort intended to protect us from Canada was being built—in Canada!

The survey that had been used to select the new fort’s site was wrong. Way wrong. It mistakenly placed the international border three-quarters of a mile to the south. Meaning the fort intended to protect us from Canada was being built—in Canada!

President Madison was mortified. He ordered construction to stop, told the Army to immediately withdraw, then apologized profusely to the Canadians, who shrugged it off with a “these things happen” response.

Washington had spent $175,000 (about $3.5 million today) on the project. Now it was all wasted in a textbook example of a government boondoggle.

With the Army gone, local residents took stone and other materials for use in their houses, buildings and barns. In a few years, the site was picked clean. No trace of it now exists.

The fort had never been officially named. Americans and Canadians alike eventually called the place exactly what it was: Fort Blunder.

The fort had never been officially named. Americans and Canadians alike eventually called the place exactly what it was: Fort Blunder.

Twenty years later, the Army built another fortification nearby. Called Fort Montgomery, it was smaller and less imposing than the original. By then US-Canadian relations were warming significantly. In 1909 it was abandoned. Today it sits empty on the shores of Lake Champlain, a decaying relic from by a bygone era.

But one thing was certain: when the Army began building Fort Montgomery, you can bet they made darn sure they went to work on the right side of the border that time!

But one thing was certain: when the Army began building Fort Montgomery, you can bet they made darn sure they went to work on the right side of the border that time!

Did you find this enjoyable? Please continue to join me each week, and I invite you to read Tell it Like Tupper and share your review!

Curious about Tell It Like Tupper? Here’s a chance to see for yourself. Take a sneak peek at a couple of chapters in this free downloadable excerpt.

The post Fort Blunder appeared first on J. Mark Powell.