James N. Powell's Blog

September 15, 2024

Cloud Melting into Sky

The Manual for Self Realization: 112 Meditations of the Vijnana Bhairava by Lakshmanjoo

The Manual for Self Realization: 112 Meditations of the Vijnana Bhairava by LakshmanjooMy rating: 5 of 5 stars

In his comments on Verse 24 of the scripture, Swami Lakshmanjoo speaks of the prana being exhaled from the heart to a space outside the body that is twelve finger-widths downward from the tip of the nostrils. And then, upon inhalation, of prana moving from the space outside the body back into the heart again.

Jaideva Singh while working closely with Swami Lakshmanjoo created a translation of the scripture. In that translation, Verse 24 reads as follows:

Para devi or Highest Sakti who is of the nature of visarga, goes on (ceaselessly) expressing herself upward (ūrdhave) (from the centre of the body to dvādaśanta or a distance of twelve fingers) in the form of exhalation (prānā) and downward (adhah) (from dvādaśanta to the centre of the body) in the form of inhalation (jiva or apana). By steady fixation of the mind (bharanat) at the two places of their origin (viz., centre of the body in the case of prānā and dvādaśanta in the case of apāna), there is the situation of plenitude (bharitāsthitih, which is the state of parāśakti or nature of Bhairava).

Singh (in consultation with Lakshmanjoo) then goes on to explain his translation in some detail.

At my request, in 1974 - 1975 Swami Lakshmanjoo and Pandit Dina Nath Muju created an English rendering of the scripture for me. Their rendition of verse 24 reads as follows:

Verse 24. The ingoing breath is (sounds) Ham and outgoing breath is (sounds) So. Observe their junction both within your heart and outside. Fullness results.

I should mention that Sanskrit a sounds like the u in the English word hum.

The incoming and outgoing breaths, when pronounced together, sound like the Sanskrit name of a bird: the swan.

On the South Asian subcontinent, the haṃsa (swan or goose), a migratory waterfowl, is poetically credited with the almost alchemical gift of being able to extract milk from a mixture of milk and water.

Some scholars have reasoned this attribute arose from the bird's ability—while floating lotus-like on lakes—to extract the milk-like nectar (kṣīra, 'milk') from the fibres within the stalks of lotus plants.

On the Asian subcontinent, this ability of the haṃsa serves as a metaphor for the discernment of the yogi(ni) who, knowing the one thing—Shoreless Consciousness—which having known, the yogi(ni) need know nothing else.

In Yoga and the Hindu Tradition (1977), Jean Veranne expounds on the direct phonetic-symbolic link between the act of breathing and the name of the migratory bird [haṃsa]. When we breathe in, the text asks, does not the air as it enters make the sound ham [hum]? And when we breathe out, does not the air hiss as it leaves, making the sound sa? So that we are, all of us, however unwittingly, forever repeating hamsa! hamsa!

The air goes in making ham! [Sounding like the English word hum.]

It goes out making sah!

So the living being lives life repeating endlessly the mantra of the bird! One needs only to become aware of this to be free from all sin. (Dhyanabindu Upanishad)

. . . .

Veranne continues as follows:

It should be added that the same two syllables in reverse order (with a slight phonetic change required by the rules of Sanskrit grammar) mean something quite different: so'ham, so'ham (I am It, I am It!) we also all proclaim as we breathe, and "It," needless to say, is hamsa, the Atman. Again, moreover, consciousness (a real, effective, experienced consciousness ) of the secret meaning of the two syllables so'ham has a liberating power. By repetition of this new mantra (esoterically identical with the first), one obtains liberation because one is relizing the identity of the self and the inner controlling force (antar-yamin)—yet one more name of Atman-Brahman. Combined, the two mantras are an encapsulation of the entire doctrine: "My true self is the Atman there in the deepest heart of myself!"

. . . .

Again, ham sounds like the English word hum.

In the translation Swami Lakshmanjoo and Dina Nath Muju prepared for me, Verse 25 reads as follows:

The energy of breath flows in and out. Be aware of the interval outside and inside. Divine manifests.

Mysteriously, in 19th century Germany there was a popular card game that taught players some basic facts about famous writers, artists, and composers. For instance, there was a card for Longfellow and also one for the composer Robert Schuman. Hesse was particularly fond of Schuman's piece “Vogel als Prophet” (The Bird as Prophet) from his collection Waldszenen (Forest Scenes), Op. 82. This piece is known for its ethereal and mysterious qualities, often evoking the image of a bird with prophetic abilities.

Herman wrote that it may have been while playing that card game that he first received the idea for writing his magnum opus, The Glass Bead Game.

Ever since he wrote the book, for which he was awarded a Noel Prize in 1949, his readers have conjectured about what the Game described within the book's pages entails.

Mysteriously, I believe it may have something to do with breathing in and out, and with Atman (Sanskrit for Self [as Shoreless Consciousness]).

Hesse distinguishes between (i) an intellectual-aesthetic level of the Game and (ii) a sacral dimension of the Game, of which most of the Game's players have no inkling. This distinction is like that between (i) dichotomizing thought structures and (ii) knowledge that transcends the mind, such as jnana (which also has to do with breath).

Consider the following passage (from the Winston translation):

Perhaps this is the place to cite that other passage from Knecht's letters, which also deals with the Glass Bead Game, although the letter in question addressed to the Music Master, was written at least a year or two later. "I imagine," Knecht wrote to his patron, "that one can be an excellent Glass Bead Game player, even a virtuoso, and perhaps even a thoroughly competent Magister Ludi, without having any inkling of the real mystery of the game and its ultimate meaning. It might even be that one who does guess or know the truth might prove a danger to the Game, were he to become a specialist in the Game, a Game leader. For the dark interior, the esoterics of the Game, points down into the One and All, into those depths where the eternal Atman eternally breathes in and out, sufficient unto itself. One who has experienced the meaning of the Game within himself would by that fact, no longer be a player; he would no longer dwell in the world of multiplicity and would no longer be able to delight in invention, construction, and combination, since he would enjoy altogether different joys and raptures. Because I think I have come close to the meaning of the Glass Bead Game, it will be better for me and for others if I do not make the game my profession, but instead shift to music."

Careful readers should note that although Hesse does not use the word Atman, in the book's original German, the translators do because of the close relationship between breath and spirit in Indo-European languages.

Consider, for instance, the following etymology of the German word for Atem:

Atem, masculine, from the equivalent Middle High German âtem (âten), Old High German âtum, masculine, ‘breath, spirit’; compare Middle High German der heilege âtem, Old High German der wîho âtum, ‘the Holy Spirit;’ Modern High German collateral form (properly dialectic) Odem. The word is not found in East Teutonic; in Gothic ahma, ‘spirit,’ is used instead (see achten). Compare Old Saxon âðom, Dutch adem, Anglo-Saxon œ̂þm (obsolete in English), ‘breath.’ The cognates point to Aryan êtmon-, Sanskrit âtmán, masculine, ‘puff, breath, spirit’; also Old Irish athach, ‘breath,’ Greek ἀτμός, ‘smoke, vapour.’

In the translation of the scripture Swami Lakshmanjoo and Pandit Dina Nath Muju prepared for me, Verse 26 reads as follows:

When the mind is silent and breath ceases to flow in and out, it stays of its own accord in the centre. Watch the moment. Divinity dawns.

This is the most beautiful of the verses on breath: the most effortless. Here the emphasis is not on the breath, the mantra, it is on the state of mind beyond thought. When that state suddenly floods duality. There is only one thing. There is no space anywhere for any technique or even the thought of a technique. There is no duality. There is only one thing. One is no longer a player of the game of meditation.

In that state: breathing has become suspended.

Jaideva Sing's comments on Verse 26 read as follows:

1. In this dhāraṇā, prana (exhalation) and apdna (inhalation) cease and madhya dasa develops, i.e., the pranasakti in the susumna develops by means of nirvikalpabhava, i. e., by the cessation of all thought-constructs; then the nature of Bhairava is revealed.

Sivopadhydya in his commentary says that the nirvikalpa bhava comes about by Bhairavi mudra, in which even when the senses are open outwards, the attention is turned inwards towards inner spanda or throb of creative consciousness which is the basis and support of all mental and sensual activity, then all vikalpas or thought-constructs cease. The breath neither goes out, nor does it come in, and the essential nature of Bhairava is revealed.

2. Dvdadasdnta means a distance of 12 fingers in the outer space measured from the tip of the nose.

3. The difference between the previous dhāraṇā and this one lies in the fact that whereas in the previous dhāraṇā, the madhya dasa develops by one-pointed awareness of the pauses of prana and apana, in the present dhāraṇā, the madhya dasa develops by means of nirvikalpa-bhava.

Abhinavagupta has quoted this dhāraṇā in Tantraloka v.22 p. 333 and there also he emphasizes nirvikalpa-bhava. He says that one should fix one’s mind with pointed awareness on the junction of prana, apana and udana, in the centre, then prana and apana will be suspended; the mind will be freed of all vikalpas, madhya dasa will develop, and the aspirant will have the realization of the essential Self, which is the nature of Bhairava.

Sivopadhyaya says that since this dhāraṇā takes the help of madhyadasa, it may be considered to be an anava updya. But the development of madhyadasa is brought about by nirvikalpa-bhava in this dhāraṇā. From this point of view, it may be considered to be sambhava upaya.

View all my reviews

Published on September 15, 2024 09:57

•

Tags:

bhairava, breath, breathing, consciousness, glas-bead-game, herman-hesse, hesse, india, jaideva-singh, kashmir, kashmir-shaivism, magister-ludi, mantra, meditation, nondual, nondual-shaiva-tantra, prana, pranayama, re-birthing, rebirthing, schuman, shakti, shiva, singh, soul, spirit, spirituality, swami-lakshmanjoo, tantra, transcendence, vijnana, vijnana-bhairava-tantra, yoga

September 8, 2024

The Glass Bead Game

The Glass Bead Game by Hermann Hesse

The Glass Bead Game by Hermann HesseMy rating: 5 of 5 stars

In this review, I share my thoughts on two spectra within the rainbow of knowledge the novel's main character, Knecht, lives: (i) According to Knecht, "one who has experienced the [esoteric] meaning of the Game within himself would by that fact, no longer be a player; he would no longer dwell in the world of multiplicity." I reveal how that is so. (ii) I also unveil a way of knowing and being in the world that Hesse learned of from his spiritual teacher, the naturmensch, pacifist, poet, painter, and antiwar activist Gustav (Gusto) Gräser.

William Wordsworth

As literary critics Harold Bloom and Lionel Trilling wrote, "Before Wordsworth, [English] poetry had a subject. After Wordsworth, its prevalent subject was the poet's own subjectivity . . . and so a new poetry was born."

The core of the subjectivity that Lake Poet William Wordsworth wrote of is a luminous, tranquil transcendental realm, a kind of terra incognita of the spirit, which beckons from within. For when breathing stills, we abide as the calm, shoreless being of our Soul.

Wordsworth:

It is a beauteous evening, calm and free,

The holy time is quiet as a Nun

Breathless with adoration; the broad sun

Is sinking down in its tranquility;

The gentleness of heaven broods o'er the Sea;

Listen! the mighty Being is awake,

And doth with his eternal motion make

A sound like thunder—everlastingly.

Dear child! dear Girl! that walkest with me here,

If thou appear untouched by solemn thought,

Thy nature is not therefore less divine:

Thou liest in Abraham's bosom all the year;

And worshipp'st at the Temple's inner shrine,

God being with thee when we know it not.

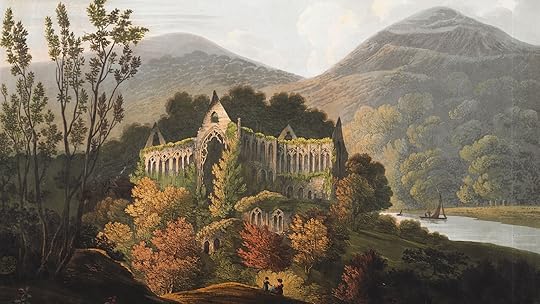

Tintern Abbey

Similarly, in "Lines Written a Few Miles above Tintern Abbey," Wordsworth whispers to us of the power of the same pause between inhalation and exhalation.

Five years have passed; five summers, with the length

Of five long winters! and again I hear

These waters, rolling from their mountain-springs

With a soft inland murmur. –Once again

Do I behold these steep and lofty cliffs,

That on a wild secluded scene impress

Thoughts of more deep seclusion; and connect

The landscape with the quiet of the sky.

The day is come when I again repose

Here, under this dark sycamore, and view

These plots of cottage-ground, these orchard-tufts,

Which at this season, with their unripe fruits,

Are clad in one green hue, and lost themselves

'Mid groves and copses. Once again I see

These hedge-rows, hardly hedge-rows, little lines

Of sportive wood run wild: these pastoral farms,

Green to the very door; and wreaths of smoke

Sent up, in silence, from among the trees!

With some uncertain notice, as might seem

Of vagrant dwellers in the houseless woods,

Or of some Hermit's cave, where by his fire

The Hermit sits alone.

These beauteous forms,

Through a long absence, have not been to me

As is a landscape to a blind man's eye:

But oft, in lonely rooms, and 'mid the din

Of towns and cities, I have owed to them,

In hours of weariness, sensations sweet,

Felt in the blood, and felt along the heart;

And passing even into my purer mind

With tranquil restoration: – feelings too

Of unremembered pleasure: such, perhaps,

As have no slight or trivial influence

On that best portion of a good man's life,

His little, nameless, unremembered, acts

Of kindness and of love. Nor less, I trust,

To them I may have owed another gift,

Of aspect more sublime; that blessed mood,

In which the burthen of the mystery,

In which the heavy and the weary weight

Of all this unintelligible world,

Is lightened: –that serene and blessed mood,

In which the affections gently lead us on, –

Until, the breath of this corporeal frame

And even the motion of our human blood

Almost suspended, we are laid asleep

In body, and become a living soul:

While with an eye made quiet by the power

Of harmony, and the deep power of joy,

We see into the life of things. . . .

Now, as cautiously as a cat approaching its prey, we will slowly advance one silent paw ahead: in the form of a puzzle:

The first part of the puzzle is this: Why does, at first glance, a line in Richard and Clara Winston’s English translation (first published in 1969) of Hermann Hesse’s Das Glasperlenspiel seem to differ so boldly from Hesse's own writing about the esoteric dimension of the Game?

Quoting from the Winston translation:

Perhaps this is the place to cite that other passage from Knecht's letters, which also deals with the Glass Bead Game, although the letter in question addressed to the Music Master, was written at least a year or two later. "I imagine," Knecht wrote to his patron, "that one can be an excellent Glass Bead Game player, even a virtuoso, and perhaps even a thoroughly competent Magister Ludi, without having any inkling of the real mystery of the game and its ultimate meaning. It might even be that one who does guess or know the truth might prove a danger to the Game, were he to become a specialist in the Game, a Game leader. For the dark interior, the esoterics of the Game, points down into the One and All, into those depths where the eternal Atman eternally breathes in and out, sufficient unto itself. One who has experienced the meaning of the Game within himself would by that fact, no longer be a player; he would no longer dwell in the world of multiplicity and would no longer be able to delight in invention, construction, and combination, since he would enjoy altogether different joys and raptures. Because I think I have come close to the meaning of the Glass Bead Game, it will be better for me and for others if I do not make the game my profession, but instead shift to music."

In our exploration of the mystical pause in breathing, advancing another paw forward, I wish to draw attention to this one sentence: "For the dark interior, the esoterics of the Game, points down into the One and All, into those depths where the eternal Atman eternally breathes in and out, sufficient unto itself."

Hesse's original reads as follows: "Denn die Innenseite, die Esoterik des Spiels, zielt wie alle Esoterik ins Ein und All hinab, in die Tiefen, wo nur noch der ewige Atem im ewigen Ein und Aus sich selbst genügend waltet."

If readers do not know German but have sunk their claws into Hesse's sentence, they may think that the word Atem (breath, spirit) is German for the Sanskrit word Atman (Self, Soul, Spirit).

The reader would be both wrong and yet closer to the esoteric secret of the Game, for in the German language, the relationship between breath and Soul is both innate (indwelling) and intimate. Thus, one needs only see that fact nakedly.

Mervyn Savill's 1949 English translation of the line reads as follows: " . . . for the inner meaning, the esoteric of the Game, aims as all esotericism does, deep down into the One and All, where only the eternal In and Out breathing reigns in self-sufficiency."

Readers may have noticed that Savill's translation does not invoke the Sanskrit word Atman, which was also not in Hesse's original.

By including the word Atman, however, Richard and Clara Winston's translation is actually closer to Hesse's original.

My reason for saying this is because the German word Atem and the Sanskrit word Atman both derive from their same ancient, Proto-Indo-European root and still resonate with the root's meanings: breath and spirit.

Thus, the German word Atem means both breath and spirit.

There is an Indian scripture, the Vijñāna Bhairava, which speaks of the transcendent relationship between Spirit and Breath. Readers can access the scripture's verse on breathing through the website on my profile

The Power of Love

Germany's industrial revolution was a nightmare. Wise, sensitive souls escaped the cities. By 1920, a bucolic countercultural enclave had become fashionable enough that Bohème Sauvage dispatched a journalist, Marie de Winter, to Switzerland. Her mission was to rub elbows with the “nature people” at Monte Verità. In her own words, to subsist on a diet of berries, grains, and nuts . . . to till in a garden while wearing only a loincloth . . . to climb the face of a huge rock while completely nude and unbelievably — to do so while accompanied by none other than the famous writer Herman Hesse, who had just applied his finishing touches to his latest novel, Demian.

Monte Verità (Mountain of Truth), in Ticino, had become a spiritual, anticolonial colony of artists and naturalists.

It had been cofounded by a group of Hippies avant la letter, including the naturmensch, itinerant teacher, pacifist, poet, painter, and antiwar activist Gustav (Gusto) Gräser: the German equivalent of America’s Bohemian, Beat, and Hippie generations all rolled into one innocently foundational personality. The painting heading this section of the review is his and entitled "The Power of Love." Hesse's journey to the East was to Monte Verità. He had ventured there to learn of Gräser's ways of being in the world.

Decades later, Americans would become absorbed in these ways only somewhat unknowingly, when, tutored by German nature lovers, California Nature Boys such as Gypsy Boots and Eden Ahbez brought organic smoothies, granola, brown rice, vegetarianism, and veganism to American tables.

Hesse learned from his German naturemensch teacher the health benefits and joys of diving into ice-cold lake waters.

[Stay tuned, to be continued]

View all my reviews

Published on September 08, 2024 15:44

•

Tags:

breath, glass-bead-game, goddess, herman-hesse, hesse, hinduism, kashmir, kashmir-shaivism, lakshmanjoo, meditation, non-dual, nondual, shaiva, tantra, the-glass-bead-game, vijnana-bhairava, wordsworth, yoga

April 6, 2024

Holden

The Catcher in the Rye by J.D. Salinger

The Catcher in the Rye by J.D. SalingerMy rating: 5 of 5 stars

From Anna Freud and J.D. Salinger’s Holden Caulfield

By Robert Coles

“I got to know this Holden Caulfield by hearsay before I met him as a reader. My analytic patients spoke of him sometimes as if they’d actually met him; they used his words, his way of speaking. They laughed as if he had made them laugh, because of what he’d said, and how he looked at things. I began to realize that they had taken him into their minds, and hugged him—they spoke, now, not only his words in the book (quotations from it) but his words become their own words (deeply felt, urgently and emphatically expressed). There were moments when I had to be the perennially and predictably pedantic listener, ever anxious, to pin down what has been spoken, call it by a [psychoanalytic] name, fit it into my ‘interpretative scheme, ’ you could call it. I would ask a young man or a young woman who it was just speaking—him, or her, or Holden! Well, I’d hear ‘me, ’ but it didn’t take long for the young one, the youth, the teenager, to have some second thoughts! They’d be silent; they’d mull the matter over—and I wasn’t surprised, again and again, to hear a quite sensible person, not out of his mind, or her mind (not ‘psychotic, ’ as we put it in staff conferences) speaking of this Holden Caulfield as though they’d spent a lot of time with him, and now had taken up, as their very own, his favorite words, his likes and dislikes, his ‘attitude, ’ one college student, just starting out, once termed it."

View all my reviews

April 2, 2024

The Captive Mind

The Captive Mind by Czesław Miłosz

The Captive Mind by Czesław MiłoszMy rating: 5 of 5 stars

"The War broke out, and our city and country became a part of Hitler's Imperium. For five and a half years we lived in a dimension completely different from that which any literature or experience could have led us to know. What we beheld surpassed the most daring and the most macabre imagination. Descriptions of horrors known to us of old now made us smile at their naivete. German rule in Europe was ruthless, but nowhere so ruthless as in the East, for the East was populated by races which, according to the doctrines of National Socialism, were either to be utterly eradicated or else used for heavy physical labor. The events we were forced to participate in resulted from the effort to put these doctrines into practice.

Still we lived; and since we were writers, we tried to write. True, from time to time one of us dropped out, shipped off to a concentration camp or shot. There was no help for this. We were like people marooned on a dissolving floe of ice; we dared not think of the moment when it would melt away."

Czeslaw Milosz

View all my reviews

Published on April 02, 2024 22:41

•

Tags:

communism, nazism, totalitarianism, ukraine, war

Hill and Hollow

Spanish Colonial Style: Santa Barbara and the Architecture of James Osborne Craig and Mary McLaughlin Craig by Pamela Skewes-Cox

Spanish Colonial Style: Santa Barbara and the Architecture of James Osborne Craig and Mary McLaughlin Craig by Pamela Skewes-CoxMy rating: 5 of 5 stars

In all their chaste simplicity and luminous grace, Mary Craig homes have, for most of my life, sheltered an unknowing soul.

My own.

For until recently, I had never known the name Mary Craig. I now thank her for her vision and the atmosphere of her creations, the airs surrounding the spaces wherein her dreams settled. Spaces resonant with the qualities of the creations themselves.

Exterior spaces are reflections of inner worlds. In The Poetics of Space, Gaston Bachelard, that self-proclaimed philosopher of adjectives, recognizes the truth that the hollows within our homes form our first and most intimate nests. We hallow these hollows because of the qualities of our lives they make possible.

Often Mary Craig homes are embosked within glades of oaks. Oaks abide. Nested within the hollow of a three-hundred-year-ancient oak, forest-bathing within its eternal current of shoreless ultra-low-freuency electromagnetic waves, we discover that oaks are prayers, their dark heartwood leafing outward into light as surely as human hearts flower inward, following the grain of an even fuller illumination.

Bachelard says our homes shelter daydreaming. Our homes protect the dreamer. Our homes allow us to dream in peace. The nooks and crannies of our homes become our centers of simplicity in dwelling, wherein we may more easily luxuriate within the primitiveness of refuge and bathe within the shoreless purity of Being.

The first Mary Craig design to nourish my inner life was a beach house. When I was a kid, any truly respectable stretch of coast in Santa Barbara, any reputable expanse of sand with a good name and a suitably high opinion of itself began to attract its own elite coterie of surf bums. Suddenly the waters off points such as Miramar, reefs such as Hammond’s, coves such as Campus, and river mouths such as Rincon, found themselves a-bob with blond-haired boys astride surfboards, awaiting waves. At one secluded beach, where vast lawns and orchards aflutter with butterflies basked beside the sea, where the waves swelled and peeled translucently over the summer sandbars, a metaphysically inclined cult of surf bums emerged. The core members of our tribe were, besides myself: Whooper, The Goose, Modoc, Chaddy, The Hog, The Ace, Stein, and The Ravin’ Baby Ese Animal Gargantua Cabron. We were brought together by a couple of simple facts. First, my big brother, The Ace, owned a woodie that ran well enough to get us all to the beach. But what was more important was the fact that as we sat eating lunch at La Colina Junior High, we shared one deep secret—isolated by steep cliffs, miles of sand, and a guarded gate that opened only to members lay one of the most lyrical beach-breaks on the entire coast—Hope Ranch Beach.

On most days the surf was flat: as contour-free as the chests of each year’s new covey of nymphs as they lay thin and thoroughbred atop their beach towels on a summer’s morn at Hope Ranch Beach, absorbed in their solar devotions, transistors tinkling with Percy Faith’s “There’s a Summer Place,” lifeguard slouched atop his white wooden tower, four or five long surfboards top-down on the wet sand, their owners stretched out on the warm dunes, lulled by the lapping of little wavelets, swarms of flies buzzing lazily above heaps of beached seaweed, seagulls screeching and pecking at the remains of a watermelon rind, Campus Point hazy off to the north, Woff Woff Point dimly to the south, and, shining silver in the haze—indolent, indifferent, and self-contained—the great Pacific, the majestic Pacific, the wide-stretching, everflowing, endlessly rolling Pacific.

The surf was not always flat. On mornings of wind swells, the haze usually loafing over the summer shoreline would ghost away, the sky would blue, and above the roaring surf, the warm air would tingle with salt spray. The covey of nymphs would come to life, plunging through the waves while struggling to keep bikinis in place; the lifeguard would awaken; and a few of us surfers would be out in the waves, spread along a mile or so of sun-drenched beach. From time to time one of us would take off on a surging swell of blue water, drop to the bottom, lean into a turn, and then squat on the board as a bellowing, hollow vortex of Pacific curled over.

A day later the beach would be dead again, the nymphs, surfers, lifeguard, and kelp flies somnolent, and the Pacific—now once again slumbering behind ever-shifting veils of mist—would resume its long silvery daydream.

On flat days, to dispel boredom, we would meander up the beach to what we did not know was a Mary Craig beach house. We would hang out there for a while, discoursing on waves, and then climb up a steep set of stairs that led to the top of a high cliff. There awaited the Bryce estate. Whenever Mrs. Bryce would see us on her property, she was always hospitable. She liked us.

I was fascinated with her little playhouse. It was nestled under some pines overlooking the dreamily enchanting waves, their eternal motion ceaselessly sounding their soft thunder.

Inside the little playhouse awaited one of Mrs. Bryce's collections of books. Imagine my delight when I discovered one of her favorites was also one of mine: Pearl Lagoon, written by Charles Nordhoff. After revisiting a chaper or so, I would drift outside and recline on a soft bed of pine needles, yielding all thought to the soft murmurations of the waves, far below, lullabying me to sleep as I imagined a little Japanese teahouse on a nearby estate, the words of a poem floating through my drowsiness:

In my ten-foot bamboo hut this spring

I have nothing

I have everything

The second Mary Craig retreat I fell into unknowingly was also surf related, though under harsher conditions, for it sheltered us during large, cold, powerful winter surf. This beach house still sits on Devereux Beach, near the point. Though it was in a state of disrepair, after a long, freezing surf session, it nevertheless provided much-needed shelter from the sun and rain and cold.

And it was a place where surfers could build a fire to gather around and shoot the bull.

The third Mary Craig abode was one I felt extremely thankful to have fallen into. I remained there for many years, aside a creek in Montecito. The oldtimers in the neighborhood would inform me that the creek had formerly flowed through the hollow wherein the building had been erected, beside the present meandering curve of creek, the hollow meandered its ancient way down the hill, tellingly lined on either side with old-growth, water-loving sycamores: creeks loyal sentinals.

The space was holy. Its former occupant, just before myself, on her way to nunhood. When we would sit, quietly, her face would begin to glow, her breathing still. I well understood her calling. She was my partner of eight years. We'd met on a meditation retreat during which I was considering monkhood. We both clipped our hair, "Francis" and "Claire". She, the wise one, joined a clan of contemplative women. They glow from head to toe.

I ended up embosked, thankfully, but unknowingly, within the Mary Craig "ten-foot bamboo hut" wherein she'd dwelled.

~

A mossy doorway opens to the hills

where summer sun will linger for a spell

where through the bedroom window steals the dawn

beside a whispering stream, an oak robed dell

Beneath those oaks embosked in pollened tones,

with moon white lips she'd chant a sullen rune,

leaf shadows aflutter a dappled trance . . .

before she'd curl into her dark cocoon

Beside our table, blessed with acorn bread

we'd kneel, our, tongues of pink, curled 'round sweet figs,

sage-curried pancake, tea and apricot:

suggestive of sweet pleasures we had shared

suggestive of sweet pleasures we'd known not

There o'er the tub curls Hokusai's towering wave,

in candleglow, Neruda's lines afloat

erode our forms of daylight into night,

kiss our unknowing into sweet delight

Within her dreams, a tiny sesame seed cottage

coyotes howl beneath a sesame seed moon,

entrancement holds our breaths a willing hostage

within the silence of the world's honeyed womb.

The earth is seed, our hearts but sesame seed stars,

each aswim in sable sesame seed night

each dissolving into rosey forms

of rosey rounded psalms of sesame seed light.

View all my reviews

Published on April 02, 2024 21:40

•

Tags:

architecture, design, home, hope-ranch, mary-craig, montecito, spanish-colonial-style