Paul Preuss's Blog

September 24, 2015

Cleopatra, Greeks and Egyptians

Cleopatra VII is perhaps the most famous woman in Western (and Middle Eastern and North African) history. Probably more has been written about her than any other woman, with the possible exception of a few religious figures. Yet for all the works that have accumulated in the past two millennia, the early sources are sparse, incomplete, and prejudiced. Contemporary references, for example by the ungallant Cicero, are mere offhand jottings. More complete histories were composed long after she died, and none is centered on her; the best of them, by Plutarch, came over a hundred years later and appears as part of his Life of Antony. All of them, letters, histories, epic poems (notably Vergil’s Aeneid, in which she plays the part of Dido of Carthage), are poisoned by the propaganda of Octavian, who won the war against her and Antony and became the emperor Augustus.

Cleopatra VII is perhaps the most famous woman in Western (and Middle Eastern and North African) history. Probably more has been written about her than any other woman, with the possible exception of a few religious figures. Yet for all the works that have accumulated in the past two millennia, the early sources are sparse, incomplete, and prejudiced. Contemporary references, for example by the ungallant Cicero, are mere offhand jottings. More complete histories were composed long after she died, and none is centered on her; the best of them, by Plutarch, came over a hundred years later and appears as part of his Life of Antony. All of them, letters, histories, epic poems (notably Vergil’s Aeneid, in which she plays the part of Dido of Carthage), are poisoned by the propaganda of Octavian, who won the war against her and Antony and became the emperor Augustus.

The best part of writing a book, short of finishing it, is the research, and these days much of my nonscientific research concentrates on Cleopatra. No, I’m not writing a historical novel, but the one I am writing depends on getting the apparent facts right and, where facts are missing altogether, making a number of persuasive guesses. Among the things we don’t know about Cleopatra is the identity of her mother. Her father, Ptolemy XII, called the “flute player,” was, like all the Ptolemaic rulers of Egypt, mostly Macedonian, that is, Greek, although Athenians and other sophisticated Greeks considered the Macedonians hillbillies (the first Ptolemy was one of Alexander the Great’s generals). Cleopatra’s mother may have been Cleopatra VI, the flute player’s wife, but she vanishes from the record shortly after Cleopatra was born, and before the birth of Cleopatra’s three younger siblings.

A possible clue appears in Plutarch, who in his Life of Antony tells us she spoke many languages and rarely used an interpreter. He lists seven of these—including the language of the Troglodytes! “It is said that she knew the language of many other peoples also, although the preceding kings of Egypt had not tried to master even the Egyptian tongue, and some had indeed ceased to speak the Macedonian dialect.”

Is her ability to speak Egyptian evidence that her mother was Egyptian, or part Egyptian? Some historians say yes. Duane Roller writes that “it was probably her half-Egyptian mother who instilled in her the knowledge and respect for Egyptian culture and civilization . . . including an ability to speak the Egyptian language.” Others, the Egyptologist Joyce Tyldesley among them, aren’t so sure. After a careful weighing of the evidence and a tour through the Ptolemaic family tree, Tyldesley concludes that “in the crudest of statistical terms, Cleopatra was somewhere between 25 percent and 100 percent Macedonian . . . she possibly had some Egyptian genes.”

In short, there’s room here for the imagination to roam, but within tight boundaries. More on this and other unanswered questions about Cleopatra in future posts.

____________________________________________

Plutarch. Life of Antony. Quoted in Tyldesley.

Roller, Duane W. 2010. Cleopatra, A Biography. New York: Oxford University Press. amzn.to/1OvuyV6

Tyldesley, Joyce. 2008. Cleopatra, Last Queen of Egypt. New York: Basic Books. amzn.to/1FvjfJK

August 25, 2015

The Ultimate Turing Test

In the last post I looked at the Turing Test, which despite Turing’s intention has come to stand for the ultimate test of machine intelligence. But machine behavior that might have won what Turing called the “imitation game” in the 1950s would fail to impress anyone today. As computers and their packaging become more diffuse and sophisticated, the bar is raised ever higher.

In the last post I looked at the Turing Test, which despite Turing’s intention has come to stand for the ultimate test of machine intelligence. But machine behavior that might have won what Turing called the “imitation game” in the 1950s would fail to impress anyone today. As computers and their packaging become more diffuse and sophisticated, the bar is raised ever higher.

An intriguing article by classicist Daniel Mendelsohn in a recent issue of the New York Review of Books reminds us that intelligent robots have been with us for roughly 2,700 years, since Homer’s Iliad. Homer’s robot builder and programmer was Hephaestus, the lame blacksmith among the Olympian gods.

…round their master his servants swiftly moved,

fashioned completely of gold in the image of living maidens;

in them there is mind, with the faculty of thought; and speech….

There have been many fictional versions of intelligent robots in the millennia since, including Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein (flesh, not metal, but a kind of intelligent robot nevertheless, not quite human but humanoid), and HAL in Stanley Kubrick’s 2001, whose imitation of humanity, like the program named Samantha in Spike Jonze’s Her, resides entirely in its voice.

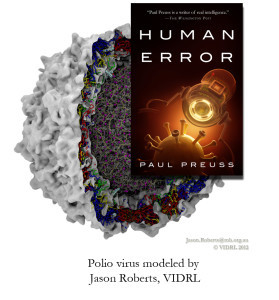

In my novel Human Error, recently republished in a digital edition by Diversion Books, the computational challenger goes farther than either a voice or a humanoid machine. Human Error and Greg Bear’s powerful Blood Music were among the first novels, perhaps the very first, to deal with the implications of nanotechnology for human evolution. Neither of us knew what the other was up to until our books came out almost simultaneously in 1985.

The two seem eerily similar, but only in the beginning. Greg’s protagonist, Vergil Ulam, creates biocomputers using his own lymphocytes; my Adrian Storey and Toby Bridgeman base their biocomputers, for geometrical reasons, on a polio virus. In both novels the inevitable infections occur. Then the two stories diverge dramatically.

Greg’s conclusion is intellectually compelling but undeniably gloomy (or perhaps gray-gooey). If you believe machine intelligence is not only possible but as much a promise as a threat, however, Human Error is actually optimistic.

For me, Human Error was always a story of the ultimate Turing Test, but for some reason the publisher wasn’t eager to use this as a tag line. (Benedict Cumberbatch’s riveting performance in The Imitation Game was some decades in the future.) Not only was the Turing Test my inspiration, thanks to Wikipedia I can pinpoint the when and the why.

Early in the 1980s Martin Gardner, who wrote Scientific American’s Mathematical Games column, was in the process of handing his column over to Douglas Hofstadter, a different sort of polymath. For a while they alternated columns monthly, and in May, 1981, Hofstadter published “A Coffeehouse Conversation on the Turing Test.” I still have the issue, as well as Hofstadter’s 1985 book in which it is reprinted, Metamagical Themas (an anagram of Mathematical Games). In the conversation, a philosopher named Sandy proposes the following:

… when it [artificial intelligence] comes, it will be mechanical and yet at the same time organic. It will have that same astonishing flexibility that we see in life’s mechanisms. And when I say mechanisms, I mean mechanisms. DNA and enzymes and so on really are mechanical and rigid and reliable…. it’s that exposure to biology that convinces me that people are machines. That thought makes me uncomfortable in some ways, but in other ways it is exhilarating.

… when it [artificial intelligence] comes, it will be mechanical and yet at the same time organic. It will have that same astonishing flexibility that we see in life’s mechanisms. And when I say mechanisms, I mean mechanisms. DNA and enzymes and so on really are mechanical and rigid and reliable…. it’s that exposure to biology that convinces me that people are machines. That thought makes me uncomfortable in some ways, but in other ways it is exhilarating.

Should I have said “spoiler alert?” No matter, getting there is all the fun. It was humbling to rediscover Hofstadter’s words, which so neatly spell out the theme and climax of the story I spent months working out after I read them; no, I didn’t think it up on my own. It was also a pleasure to be reminded that, by courtesy of what was then largely imaginary bio-nanotechnology, Human Error was the first tale of a human robot.

Not humanoid, human. And, one might argue, a hell of a lot more like the humans we all wish we were than we can otherwise hope to be.

____________________________________________________________________

References

Hofstadter, Douglas. 1981. “A Coffeehouse Conversation on the Turing Test.” Scientific American (May). The “symposium,” plus Hofstadter’s amusing and informative 1985 post scriptum, are available online at bit.ly/1JhTFEm.

Mendelsohn, Daniel. 2015. “The Robots are Winning.” New York Review of Books (4 June). Available online at bit.ly/1PRbLl6.

Polio virus simulation by Jason Roberts of the Victorian Infectious Diseases Reference Laboratory, Melbourne, Australia. Available online at bit.ly/1NSZlrF.

August 17, 2015

The Turing Test Returns

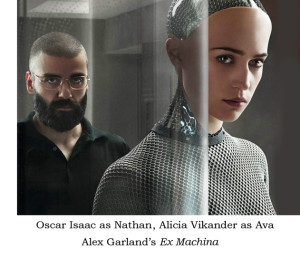

Robots of all sorts, but especially humanoid robots that can pass the Turing Test, are making a strong comeback to popular awareness. Interest is signaled by a raft of articles, fiction and nonfiction books, TV shows, and movies, including excellent ones like Spike Jonze’s Her, Alex Garland’s Ex Machina, and Morten Tyldum’s The Imitation Game (no robots in the latter, rather the story of the man who started all the fuss).

Robots of all sorts, but especially humanoid robots that can pass the Turing Test, are making a strong comeback to popular awareness. Interest is signaled by a raft of articles, fiction and nonfiction books, TV shows, and movies, including excellent ones like Spike Jonze’s Her, Alex Garland’s Ex Machina, and Morten Tyldum’s The Imitation Game (no robots in the latter, rather the story of the man who started all the fuss).

No physical humanoid appears in Her, but Scarlett Johansson’s voice is all that’s needed to evoke the machine’s intimate and profound imitation of a human being. In Ex Machina, on the other hand, the robot frankly presents herself as a piece of machinery having only an expressive face and, yes, a persuasive voice. She gradually and intentionally acquires a human appearance, first by pulling long stockings over her metal legs and a knit cap over the skull that protects her luminous brain. The process continues — clothes, hair, skin — a teasing transformation essential to the robot’s plan to pass the Turing Test beyond question.

In Alan Turing’s 1950 paper, “Machinery and Intelligence,” the imitation game was first presented as a party game in which a man and a woman in separate rooms each try to convince another party-goer they are the opposite sex. Replacing the woman with a machine (!) was Turing’s next step to the test now named after him. Turing specified that the replies had to be typed, since computers couldn’t speak. Sixty-five years later your smartphone plays the game.

One of the more famous arguments against artificial intelligence, philosopher John Searle’s so-called “Chinese Room,” attempts to dismiss the Turing Test as meaningless. Turing himself thought the question of machine intelligence was meaningless; if the machine could fool you, it might as well be intelligent. What exercised Searle was the supposition that a machine that could pass the Turing Test would have more than rote machine intelligence; it would have a mind and consciousness.

In a 1980 paper, “Minds, Brains, and Programs,” Searle supposes that if he were inside a room supplied with enough Chinese characters and a sophisticated set of instructions (i.e., a program, written down) detailing how a set of Chinese characters in the form of a written question should be transferred into a different set of Chinese characters that accurately answered the question, then he could simply follow directions and fool a native Chinese interrogator into believing he understood Chinese.

Anyone who has studied Chinese will tell you that’s impossible. There are tens of thousands of Chinese (Mandarin) characters; several thousand are the minimum needed to communicate; many have different meanings in different contexts. How long would it take Searle to identify the characters he’s presented with and find the different characters he needs to answer the question? An hour? A day? Probably, depending on the question, a lot longer.

Bad timing is a dead give away. To pass the Turing Test, Searle would have to actually understand Chinese. And in fact, should he wish to dedicate several years to playing the game, he might eventually be able to do so. He would have learned it because he has a mind as well as a program.

So would any computer that can pass Searle’s challenging version of the Turing Test, I believe. Indeed, there are versions of the test even more challenging than Searle’s. For maximum persuasiveness, the successful intelligent computer will likely be a walking, talking, convincingly humanoid robot.

So would any computer that can pass Searle’s challenging version of the Turing Test, I believe. Indeed, there are versions of the test even more challenging than Searle’s. For maximum persuasiveness, the successful intelligent computer will likely be a walking, talking, convincingly humanoid robot.

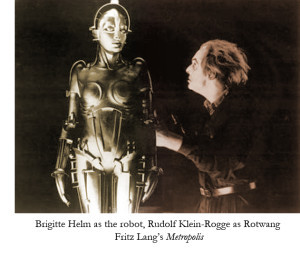

Less than a century ago, the first robot disguised as a live woman appeared on screen in Fritz Lang’s 1927 science-fiction extravaganza, Metropolis. Yet stories about humanoid robots are nothing new; they’re at least as old as the Iliad (and yes, they too were women). More on this next time — and a look at what I think is needed to pass the ultimate Turing Test.

August 5, 2015

The Deep Rhythms of Writing

My previous post concerned the desperate writer (otherwise known as “you”) grappling with a first draft. I focused on two how-to-write books with shared values but quite different approaches: Bird After Bird, by Anne Lamott, and Several Short Sentences About Writing, by Verlyn Klinkenborg. The two have radically different styles but a common regard for rhythm. Most writers do. For many readers it’s the mystery element in a good story.

My previous post concerned the desperate writer (otherwise known as “you”) grappling with a first draft. I focused on two how-to-write books with shared values but quite different approaches: Bird After Bird, by Anne Lamott, and Several Short Sentences About Writing, by Verlyn Klinkenborg. The two have radically different styles but a common regard for rhythm. Most writers do. For many readers it’s the mystery element in a good story.

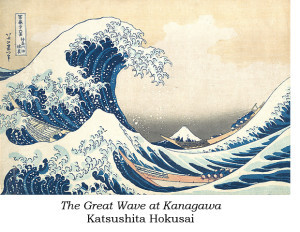

Ursula Le Guin’s thoughts on rhythm are the most meaningful and moving I’ve come across. You’ll find them in The Wave in the Mind, which is not a how-to-write book; although it includes lots of good advice, it’s a book of feelings, reflections, manifestos, a few poems (including the hilarious “Loud Cows”), and elegant miscellany centered on her personal experience of writing. (Le Guin’s superb how-to-write book, Steering the Craft, becomes available in an up-to-date revised edition this September 15.)

Le Guin’s inspiration, and the title of her book, are from a letter Virginia Woolf wrote to Vita Sackville-West in 1926:

Style is a very simple matter: it is all rhythm. Once you get that, you can’t use the wrong words. But on the other hand here am I sitting after half the morning, crammed with ideas, and visions, and so on, and can’t dislodge them, for lack of the right rhythm. Now this is very profound, what rhythm is, and goes far deeper than words. A sight, an emotion, creates this wave in the mind, long before it makes words to fit it; and in writing (such is my present belief) one has to recapture this, and set this working (which has nothing apparently to do with words) and then, as it breaks and tumbles in the mind, it makes words to fit it.

Of this passage Le Guin writes, “I have not found anything more profound, or more useful, about the source of story.”

In much of The Wave in the Mind, the question that most concerns Le Guin is where stories come from. Ideas are necessary but far from sufficient. For Le Guin, two things are needed before a novel (what she calls a “big story”) can crystallize around an idea: “I have to see the place, the landscape; and I have to know the principal people. By name.” The story often comes to her along with the setting and characters, but these rarely come easily.

The same is true of many writers, in fact of Woolf, who in another letter quoted by Le Guin wrote that a novel starts with “a world. Then, when one has imagined this world, suddenly people come in.” But Le Guin reminds us that even after the characters have arrived, bringing with them a plot, “telling the story is a matter of getting the beat — of becoming the rhythm, as the dancer becomes the dance.”

If rhythm is style but deeper than style, if rhythm is what dislodges jammed ideas, if the perception of rhythm can come from inside our bodies or from the universe around us, what’s required to catch the beat? What must we do to tame this wild music of our story?

If rhythm is style but deeper than style, if rhythm is what dislodges jammed ideas, if the perception of rhythm can come from inside our bodies or from the universe around us, what’s required to catch the beat? What must we do to tame this wild music of our story?

The main thing is patience. Sometimes we have to be patient for years; usually things happen faster than that, but, as I can attest, any attempt to speed things up is more likely to slow them down. You can never tell. And that has to be all right with you.

Le Guin gives us a parable, the tale of the taming of the fox from Antoine Saint-Exupéry’s Little Prince. The fox insists that the little prince tame him, and when the prince asks how, tells him that each day he must sit down “at a little distance from me in the grass. I shall look at you out of the corner of my eye, and you will say nothing. Words are the source of misunderstanding. But you will sit a little closer to me every day….”

“And so the fox is tamed,” Le Guin says. “And when they part, the fox says, ‘I will make you a present of a secret…. You become responsible, forever, for what you have tamed.’”

Of the secret of finding the rhythm, Le Guin says, “I think what keeps a writer from finding the words is that she grasps at them too soon, hurries, grabs…. she doesn’t wait for the wave to come and carry her beyond all ideas and opinions, to where you cannot use the wrong word.”

That would be a great way to write a first draft. It’s the only way to write the last one.

____________________________

References

Klinkenborg, Verlyn. 2012. Several Short Sentences About Writing. New York: Knopf. bit.ly/1I8U23g

Lamott, Anne. 1994. Bird by Bird: Some Instructions on Writing and Life. New York: Pantheon. bit.ly/1IIvuUw

Le Guin, Ursula K. 2004. The Wave in the Mind: Talks and Essays on the Writer, the Reader, and the Imagination. Boston: Shambhala. bit.ly/1JtLbxM

————— 2015. Steering the Craft: A Twenty-First-Century Guide to Sailing the Sea of Story. Wilmington, MA: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. amzn.to/1fFpAGn

July 29, 2015

Sentence by Sentence, Another Way to Write

I stumbled over a random, breathless paragraph in the pages of the July 27 issue of the New Yorker. It was a trap.

Writers tumble into this story, and then they plummet. I have always supposed this to be because Gould suffered from hypergraphia. He could not stop writing. This is an illness, a mania, but seems more like something a writer might envy, which feels even rottener than it usually does, because Gould was a toothless madman who slept in the street. You are envying a bum….

Writers tumble into this story, and then they plummet. I have always supposed this to be because Gould suffered from hypergraphia. He could not stop writing. This is an illness, a mania, but seems more like something a writer might envy, which feels even rottener than it usually does, because Gould was a toothless madman who slept in the street. You are envying a bum….

The author, Jill Lepore, isn’t done with her paragraph yet, and she’s not done with “you,” the hapless writer. It seems that what Gould wrote was dreadful.

But wait, that’s worse, because then you have to ask: Maybe everything you write is dreadful too. But then, in one last twist, you find out that everything he wrote never even existed….

Since Lepore is one of my favorite essayists, and rarely breathless, I had to backtrack and read her article, “Joe Gould’s Teeth.” It has a grisly fascination. Gould was an awful little man, racist, misogynist, anti-Semitic, a eugenecist, a stalker, interesting mainly for his misery, for what other people wrote about him, and for the supporters of his endless (maybe) hand-written work called “Oral History.” Among them were e.e. cummings, Ezra Pound, Marianne Moore, and William Saroyan.

What stayed with me was that original paragraph, Lepore’s evocation of the desperate writer. Every writer will tell you how hard it is to write a book (James Patterson possibly excepted). Since no one who hasn’t done it believes us, we ought to stop whining.

Nevertheless, writers keep writing how-to-write books. Presumably the market is those who hope to become writers themselves. I suspect a bigger market is those of us who have been writing for years.

What we are looking for, I think, is reassurance. Maybe a reminder or two, or even some hints. The best of these books agree on most points: how hard it is to write, of course; the insistence on essential truth; the need for some understanding of grammar and syntax; the value of reading aloud; the necessity of rewriting (and, in my case, rewriting and rewriting); patience.

What we are looking for, I think, is reassurance. Maybe a reminder or two, or even some hints. The best of these books agree on most points: how hard it is to write, of course; the insistence on essential truth; the need for some understanding of grammar and syntax; the value of reading aloud; the necessity of rewriting (and, in my case, rewriting and rewriting); patience.

The most common advice is “throw up, then clean up.” For years I thought this phrase was Anne Lamott’s, from her bravura memoir-cum-manual, Bird by Bird, but she’s more direct. She calls it “shitty first drafts.” “The first draft is the child’s draft, where you let it all pour out…. If one of the characters wants to say, ‘Well, so what, Mr. Poopy Pants?,’ you let her. No one is going to see it.”

Lamott means to convey that all first drafts are shitty. If you can’t accept that, you’ll never really write. (Surely there are exceptions, you say. Yeah, and every year somebody, somewhere, wins Mega Millions, at odds of 258 million to 1.) Her advice is excellent. It can’t be argued against. But her emphasis is on a certain kind of playful sloppiness that’s only one of many ways to make a first draft shitty.

Verlyn Klinkenborg’s writing advice is generally similar, but in Several Short Sentences About Writing, his emphasis is quite different:

Here, in short, is what I want to tell you.

Know what each sentence says,

What it doesn’t say,

And what it implies.

Of these, the hardest is knowing what each sentence actually says.

In these sentences Klinkenborg is actually saying that shittiness resides not only in the first draft as a whole but in almost all of its first-attempt sentences.

(Yes, he lays out his entire book this way, every new sentence flush left. Annoying, but eventually you get used to it, and it makes a point. “Point” being a concept he hates, by the way, along with meaning, logic, transitions, and all the rules about writing he supposes you learned in school.)

Why are we talking about sentences…?

The answer is simple.

Your job as a writer is making sentences.

…

Most of the sentences you make will need to be killed.

The rest will need to be fixed.

He tells you exactly how to do it, from the general (“Start by learning to recognize what interests you…. Notice what you notice and let it go”) to the particular (a list of words and phrases to avoid: In fact./ Indeed./ On the one hand./ On the other hand./ Therefore./ Moreover./ However./ In one respect./ Of course./ Whereas./ Thus).

He tells you exactly how to do it, from the general (“Start by learning to recognize what interests you…. Notice what you notice and let it go”) to the particular (a list of words and phrases to avoid: In fact./ Indeed./ On the one hand./ On the other hand./ Therefore./ Moreover./ However./ In one respect./ Of course./ Whereas./ Thus).

One reason I like Klinkenborg is because I write his way, or try to, one sentence at a time — a great excuse for being a slow writer. Anne Lamott’s criteria are just as strict, but her way of writing a first draft, slinging Mr. Poopy Pants around, would be a lot more fun. If I could do it.

You can have a whole manuscript full of good sentences and still have a shitty first draft, because of plot problems, cliché characters, whatever. Worst of all is lack of a true story. Not factually true, but honest.

In her book The Wave of the Mind, Ursula Le Guin shares a vision of how to write that’s certainly no easier than Lamott’s or Klinkenborg’s approaches but somehow filled with hope. More next time.

References:

Klinkenborg, Verlyn. 2012. Several Short Sentences About Writing. New York: Knopf. bit.ly/1I8U23g

Lamott, Anne. 1994. Bird by Bird: Some Instructions on Writing and Life. New York: Pantheon. bit.ly/1IIvuUw

Le Guin, Ursula K. 2004. The Wave in the Mind: Talks and Essays on the Writer, the Reader, and the Imagination. Boston: Shambhala. bit.ly/1JtLbxM

Lepore, Jill. 2015. “Joe Gould’s Teeth: The Long-lost Story of the Longest Book Ever Written.” New Yorker (27 July). nyr.kr/1LW8fqF (may need a subscription)

July 17, 2015

The Nonexistent Paradoxes of Time Travel

This clock has seen a lot of time go by. (Photo by Cami.)

Apparently the first story to hint at the paradoxes of time travel was Edward Page Mitchell’s “The Clock that Went Backward,” which appeared in a New York newspaper, The Sun, in 1881. Most of the action takes place in Leyden, the Netherlands, where a 300-year-old clock made by one Jan Lipperdam sends the narrator, his cousin Harry, and their professor, Von Stott, back in time to the historic siege of 1574. Events suggest, although with much uncertainty, that Von Stott is Lipperdam, and that Harry is his own great-grandfather.

These are foreshadowings of the by-now traditional grandfather paradox and bootstrap paradox (or causal loop), the latter named for Robert Heinlein’s 1941 short story “By His Bootstraps.” The causal loop is often illustrated with the tale of an inventor of a time machine who uses it to return to his past, where he teaches his younger self how to build it; where, except from himself, did he get the information? The grandfather paradox raises the possibility that a man returns to the past and kills his own grandfather, an act that should have pre-erased him.

Some kinds of time travel are commonplace. Imagine a scientist who brings an atomic clock aboard a jet plane and flies around the world; velocity makes her clock run slower than an identical clock on the ground, which is tended by her twin sister; she thus returns to Earth in her sister’s future.

This is a version of the so-called twin paradox, which is not a paradox at all but a straightforward result of Special Relativity. (Gravity also has an effect on the passage of time, but for now we can ignore it.) The clocks aren’t necessary; they’re just there to prove that people in the speeding plane, or space shuttle, or some future rocket to Andromeda, really do travel into the future of those they leave behind, whether by nanoseconds or centuries. Many such experiments have been performed.

Even if travel to the past is not impossible, it would require tremendous energy and expense—not to mention unlikely circumstances, such as wormholes that don’t annihilate everything that falls into them. So far, visits to the past happen only in fiction. If the protagonist gets whacked on the head or runs into a chronosynclastic infundibulum, it’s probably a work of satire. If the author hand-waves about time machines, black holes, spacetime continua, or genetic disorders, it’s a science fiction story. However much real science there may be in the story, there’s none in the mechanism for traveling back in time.

Philosophers love it anyway. In 1976 David Lewis published an essay titled “The Paradoxes of Time Travel.” With typical bluntness, he begins, “Time travel, I maintain, is possible. The paradoxes of time travel are oddities, not impossibilities.” He’s not talking about practical difficulties but logical ones. “I shall be concerned here with the sort of time travel that is recounted in science fiction.”

Lewis is beloved of fiction writers, at least this one, because of his argument—stated in his 1978 essay, “Truth in Fiction”—that “worlds where the fiction is told, but as known fact rather than fiction,” are not only possible worlds but real ones.

Unlike the twin paradox, however, the paradoxes of travel to the past are widely thought to render these fictional worlds impossible. In a subtle retort, Lewis deals with the objection by distinguishing two kinds of time, external and personal. External time deals with the real world, personal time with the time traveler’s experience. “We can say without contradiction, as the time traveler prepares to set out, ‘Soon he will be in the past.’”

A time traveler’s personal time is always continuous. (M.C. Escher, red ants on a Mobius strip)

With this simple distinction, Lewis demolishes the grandfather paradox. In neither the linear passage of external time nor the loops and leaps of the time traveler’s personal time is continuity ever interrupted. “Tim [a time traveler who is motivated and able to kill his grandfather] cannot kill Grandfather. Grandfather lived, so to kill him would be to change the past. But the events of a past moment… cannot change.”

There’s no such simple solution to the bootstrap paradox, since it too respects the demands of both external and personal time. Causal loops are possible, says Lewis, but they don’t matter.

Where did the information come from in the first place…? There is simply no answer. The parts of the loop are explicable, the whole of it is not. Strange! But not impossible, and not too different from the inexplicabilities we are already inured to. Almost everyone agrees that God, or the Big Bang, or the entire infinite past of the universe, or the decay of a tritium atom, is uncaused and inexplicable. Then if these are possible, why not also the inexplicable causal loops that arise in time travel?

In this blithe paragraph, Lewis puts his finger on one of the central tenets of real science, namely, that there is a profound difference between the inexplicable and the impossible.

July 8, 2015

Blast from the Past

Crossroads Baker. The dark object on the right side of the column of water is a battleship. Vertical.

The USS Independence survived World War II and two A-bomb blasts before it was scuttled near the Farallon Islands in 1951. In 1946, in the joint army/navy Operation Crossroads, the navy had assembled more than ninety vessels at Bikini Atoll in the Marshall Islands, ostensibly to test the effects of atomic weapons on ships. Another motive, perhaps the real one, was to scare the Soviets, who had been invited to observe. There was nothing novel about the bombs; they were the same kind that had destroyed Nagasaki less than a year earlier, the spherical, plutonium implosion type called called Fat Man. They were straight from the US nuclear arsenal—a very small arsenal, but the Soviets didn’t know that.

In Crossroads Able the army air force dropped the first Fat Man and missed its target by almost half a mile. On the second try, Crossroads Baker, the navy made sure they hit something by hanging their bomb from a landing craft in the middle of the flotilla. The result was the most poisonous fountain of water in history, accompanied by a radioactive fog that engulfed the surviving ships and a tsunami that washed over the surrounding islands. The third test had to be canceled, and no one has settled in the atoll since.

As for the propaganda effect on the Soviet scientists, it was nil, and, in fact, possibly a stimulant; the Soviets exploded their first A-bomb, closely based on the stolen Fat Man design, just three years later.

After Crossroads came to an end, the damaged, radioactive Independence was among ten ships towed back to San Francisco. Clean-up experiments failed, and it was scuttled four years later, thirty miles west of Half Moon Bay in what’s now the northern part of the Monterey Bay National Marine Sanctuary. The sunken ship was revisited this April by NOAA scientists headed by James Delgado, using the Boeing autonomous underwater vehicle Echo Ranger to image the ship with sonar—but not before UC Berkeley and Lawrence Berkeley Lab radiation expert Kai Vetter calculated the risks to equipment and personnel. In a release titled “Radiation Safety for Sunken-Ship Archaeology,” Berkeley Lab’s Kate Greene gives the details.

The rusty wreck, lying 2,600 feet underwater for the past sixty-four years, poses no significant risk of radiation poisoning. Even a significant risk of that kind is a small part of the much greater risk posed by countries who refuse to draw down their nuclear arsenals, or secure them sloppily, or are trying to build their own, or who lie about trying to build their own, or who lie about the hidden arsenals they already possess.

Have I left anybody out?

July 1, 2015

Evolving Language: Conservatives versus Radicals

William Morris’s edition of William Caxton’s The Recuyell of the Historyes of Troye, the first book printed in the English language. (http://bit.ly/1GNoHTd)

In his 1985 book The English Language, Robert Burchfield calls the era of frequent changes in pronunciation, usage, and the coinage of new words that started in the late eighteenth century “the period of disjunction.” Disjunction was going strong when Burchfield, a long-time editor of the Oxford English Dictionary, died in 2004, and it hasn’t slowed. Like the expansion of the physical universe, it seems to be accelerating.

Whether for fun, profit, or from passionate commitment or a sense of duty, most people who concern themselves with such changes spend a lot of their time writing, whether their job title is teacher, philosopher, social worker, copy editor, or something farther afield. Such folk span the linguistic spectrum from conservative to radical. A century ago conservatives ran the show; they’re called prescriptivists because they believe there are right and wrong ways to spell and use words. Radicals (descriptivists) decline to criticize even obvious grammatical mistakes, or, more accurately, mistakes that appear obvious at the time.

These labels have nothing to do with politics. Politically I’m left of Barack Obama on most issues, but when it comes to usage I’ve always leaned conservative. Thus my favorite one-volume dictionary is the American Heritage, with its handy Usage Panel, and The Chicago Manual of Style is my backstop for questions about punctuation, capitalization, when to use italics and when to use Roman type, and whether to write out eleven, twelve, thirteen, all the way to one hundred, or use the numerals 11, 12, 13 instead. (And long live the serial comma.)

Then, a few years ago, I caught myself describing a person as “forthcoming”—not that she would soon be making an entrance, but meaning she talked openly about a personal experience. I was on the slippery slope.

As Burchfield points out, brand-new words are much less common than old ones that have acquired new meanings, such as nouns that become verbs (so-called back formations). “Gift” as a verb makes me cringe; I wonder where it came from and why people bother with it. “He gifted me this book” is harder to say than “He gave me this book” and to my ear sounds infantile.

When I was doing research on Cleopatra for a novel, however, I discovered Joyce Tyldesley’s Cleopatra, Last Queen of Egypt, and on page 11 ran straight into “The Romans… believed they had a valid legal claim to Egypt, which had been gifted to them seven years earlier in a vexatious will….” A few pages later I hit “Cyprus as well as Egypt had been gifted to Rome….” Tyldesley is a British archaeologist and Egyptologist, and her biography of Cleopatra is the all-around best of the current crop. Those are the only two times she gifts us with that unhappy usage, but I can no longer pretend it betrays ignorance.

One word I’ll try never to use (outside quotes, whether on the page or in the air), whose misuse has reached a fever pitch, originally meant “to upset the order of…, to break or burst.” In 1997 it was repurposed by Harvard professor Clayton Christensen to describe a business strategy, summarized by Jill LePore in the June 23, 2014 New Yorker as “the selling of a cheaper, poorer quality product that initially reaches less profitable customers but eventually takes over and devours an entire industry.”

Disruption the old-fashioned way.

I’m talking about “disruption,” often heard paired with “innovation.” LePore’s article, “The Disruption Machine,” deconstructs the so-called theory of disruptive innovation, just-so story by just-so story. “Disruptive innovation is competitive strategy for an age seized by terror,” she writes. If you’re weighing crowdfunding an innovatively disruptive startup app against, say, buying stock in railroads, read the article. It’s full of apposite facts like “Three out of four startups fail. More than nine out of ten never earn a return.” Maybe because I already hated the new use of the word and finally found someone who agreed with me (and had the facts at hand), I thought LePore was one of the smartest writers I’d ever read.

The professor she criticized agrees: “She’s just an extraordinary writer.” In his response on the Bloomberg website, however, he pities himself in the third person (“she starts instead to try to discredit Clay Christensen, in a really mean way”), offers feeble excuses for the failures of his theory, and belittles her, repeatedly calling a woman he’s never met by her first name (“Jill, tell me, what’s the truth?”).

The theory of disruptive innovation will fade as its emptiness becomes apparent, but some of the original meaning of disruptive is forever lost. Ending his chapter on the disjunctive period, Burchfield writes, “… most of the new features that are intensely disliked by linguistic conservatives will triumph in the end. But the language will not bleed to death. Nor will it seem in any way distorted once the old observances have been forgotten.”

I’m bracing myself.

June 24, 2015

Tangled Up in Quanta

Quantum entanglement is easy to describe but not easy to understand. It plays a key role in my novel Secret Passages, newly reissued by Discover Books, and is crucial to the theory developed by my protagonist, Manolis Minakis, that allows him to look deep into his own past. (Yes, that last part is fiction. Maybe).

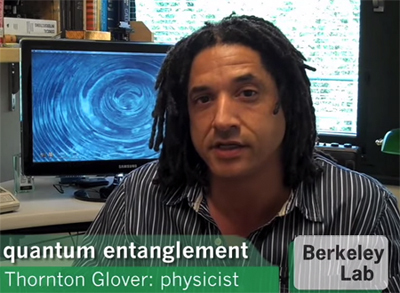

Thornton Glover explains quantum entanglement in one minute and ten seconds. Click on the link in the text.

Thornton Glover of Berkeley Lab’s Advanced Light Source gives one of the best one-minute explanations of quantum entanglement I know, so have a look. What he calls red and blue can be any number of quantum properties in a pair of particles prepared together, such as the spin orientation of electrons or the polarization of photons. The states remain superposed, like Schrödinger’s alive-dead cat, until one is measured.

Because the two (or more) particles are entangled, measuring one instantly determines the state of the other, no matter how far apart they are. Einstein called it “spooky action at a distance,” but the effect has been demonstrated over many kilometers by Alain Aspect and other experimentalists using polarized photons.

The act of measurement is known as collapsing the wave function. The wave function includes all possible outcomes of the particle’s superposed states; collapsing it picks just one. Consider a system of entangled electrons, all of them spin up and spin down, not one or the other. They can stand for superposed bits of information in a quantum computer. A few entangled electrons in nitrogen-vacancy centers of a ring-sized diamond, for example, could store more data than a classical supercomputer and, upon the collapse of the wave function, process it instantly.

So what’s the fuss? In fact, for young physicists who were already tackling quantum mechanical calculations in high school or before, there is no fuss; the attitude is “get over it, that’s the way the world works.”

Not all physicists, even young ones, are so blasé. In those for whom philosophy is not a dirty word, quantum entanglement raises the specter of instantaneous communication, and such horrors as causes coming before their effects. An obvious objection is that if two particles can be as far apart as from here to Jupiter, and measuring the state of the one here instantly fixes the state of the one there, then information must be traveling much faster than the speed of light. At the very least it violates relativity theory.

Einstein claimed this showed that quantum mechanics is incomplete. He and his colleagues said extra terms were needed, what became known as hidden (local) variables. First John Bell and later Alain Aspect disproved Einstein’s argument.

Other proposals followed and are still coming. Perhaps the most famous is Hugh Everett’s many worlds interpretation (MWI), which has proved tremendously useful to many science fiction writers, including me; it gives us an infinity of not-quite-identical worlds to play in. MWI does away with collapsing wave functions by supposing that every possible state of every particle exists in its own parallel reality. A single wave function covers them all.

John Wheeler and Richard Feynman theorized that particles actually do reverse in time, an indirect way of avoiding the collapse of the wave function because, it seems to me, it leads to a universe that doesn’t change: the same particles move backward and forward in time, constantly switching temporal direction, constituting everything we experience and know.

Wheeler and Feynman were the inspiration for my favorite theory, John Cramer’s transactional interpretation of quantum mechanics, which posits two waves (estimates of probability) for every quantum event, one emitted forward in time, the other emitted backward, which meet and with a “handshake” settle the true state of the event. This is the basis, as far as real science goes, of Manolis Minakis’s backwards-in-time experiment in Secret Passages.

A recent, ingenious attempt to evade the paradoxes of quantum entanglement and the collapse of the wave function must also be mentioned, the QBism of Christopher Fuchs. Quoted by Amanda Gefter in Quanta Magazine, Fuchs describes physics as a “dynamic interplay between storytelling and equation writing”—right on!—and regards the wave function not as a description of reality but of our personal beliefs about and knowledge of reality at a given moment. Lots to think about here, so I encourage you to read Gefter’s interview with Fuchs.

Meanwhile I’ll conclude by saying that a storyteller has to cheer the prospect of confronting the role human involvement plays in seemingly hands-off physics. Fuchs may be onto something, whether or not his math holds up in the long run. The measurements needed to collapse wave functions have long been a thorn in the side of those inclined to fret. Collapses happen all the time; the world goes on even when we’re not looking. Who’s doing the observing? Einstein put the dilemma succinctly: “Is it enough that a mouse observes that the moon exists?”

Meanwhile I’ll conclude by saying that a storyteller has to cheer the prospect of confronting the role human involvement plays in seemingly hands-off physics. Fuchs may be onto something, whether or not his math holds up in the long run. The measurements needed to collapse wave functions have long been a thorn in the side of those inclined to fret. Collapses happen all the time; the world goes on even when we’re not looking. Who’s doing the observing? Einstein put the dilemma succinctly: “Is it enough that a mouse observes that the moon exists?”

June 19, 2015

Relaunch

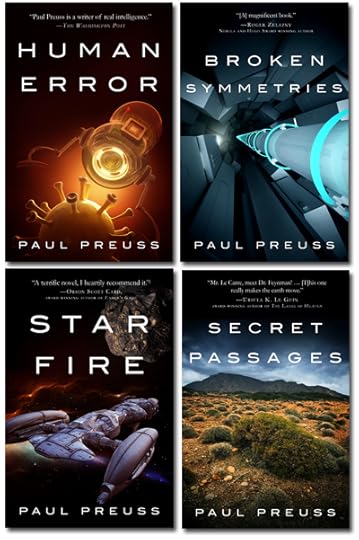

More than an excuse, I’ve been given a directive to reactivate my blog, update my website, and generally show up for duty on social media, starting now. The occasion is the reissue of four novels by Diversion Books, an innovative new publisher with a strong position in digital publishing and plans for more.

More than an excuse, I’ve been given a directive to reactivate my blog, update my website, and generally show up for duty on social media, starting now. The occasion is the reissue of four novels by Diversion Books, an innovative new publisher with a strong position in digital publishing and plans for more.

The big day is this coming Tuesday, June 23. Each of the four novels tells a story in which the characters grapple with the implications of different kinds of science: Human Error is about nanoscale biotechnology and the ultimate Turing Test, while Starfire is about an inertial-fusion-powered rocketship’s tangle with the sun. Broken Symmetries is about extreme particle physics, and its sequel, Secret Passages, is about quantum mechanics and the archaeology of Crete. Every book is about other things too, of course; more information is on the fiction page of my website.

In an evolving age of publishing, a lot of authors complain about publishers who expect them to do all the work. I admit I was one of the gripers, until I met (via email, so far) the staff at Diversion, among the smartest and hardest working crews I’ve encountered in the business. It’s a shared undertaking.

In future I’ll blog about some of the scientific subjects raised in the four books, then and now. All are set in the near or slightly alternate future (which for some of them has become the alternate past). In every field where I’ve had experience as a science writer, from cosmology to materials science to molecular biology, change has been rapid, thrilling, and sometimes scary. And not just in science. Beyond what’s in these novels I’ll be visiting topics like artificial intelligence, the Internet of Things, the evolution of the English language, art theft, cellphone networks in the jungle, and more. There’s new fiction in the works, and I’ll share its progress. I’ll be having fun, and I hope you’ll join me.

Paul Preuss's Blog

- Paul Preuss's profile

- 21 followers