Bill Steigerwald's Blog

May 25, 2020

Sorry, Charley: The fabulism of ‘Travels With Charley’

After criss-crossing America in the tracks of John Steinbeck’s ‘Travels With Charley,’ Bill Steigerwald came to a conclusion: The esteemed work is something of a fraud. (Victimless, perhaps, but still.)

A cornfield near Alice, N.D., where Steinbeck supposedly camped overnight and met an itinerant Shakespearean actor in October 1960.

The Pittsburgh Post-Gazette

Sunday, December 05, 2010

By Bill Steigerwald

ALICE, N.D. — “Hah!” I blurted out as a million North Dakota cornstalks rattled in the pushy October wind.

“Who were you trying to kid, John? Who’d you think would ever believe you met a Shakespearean actor out here?”

For three weeks I had been retracing the 10,000-mile road trip Steinbeck made around America for his nonfiction bestseller “Travels With Charley,” and chronicling it for the Post-Gazette.

I wasn’t in the habit of speaking directly to the ghost of John Steinbeck. But I couldn’t stop from laughing at the joke that Steinbeck played on everyone in the pages of “Travels With Charley,” released in 1962 to national acclaim and still revered as a document of the American soul.

No one could hear me talking to Steinbeck’s ghost that Oct. 12 afternoon. I was parked on an unpaved farm road in the earthly equivalent of outer space — the cornfields of North Dakota, 47 miles southwest of Fargo.

The closest “town” was Alice, N.D., a 51-person dot on the map of a state famous for its emptiness, badlands and Lawrence Welk. The closest person, a woman, was more than a mile away, hidden in the cloud of dust her combine made as it shaved the stubble of the family wheat crop down to the dirt.

Alice is the scene of one of the most egregious fictions in “Travels With Charley.” Steinbeck wrote that he camped overnight somewhere “near Alice” by the Maple River, where he just happened to meet an itinerant Shakespearean actor who also just happened to be camping in the middle of the middle of nowhere.

According to Steinbeck’s account in “Charley,” the two hit if off and had a long, five-page discussion about the joys of the theater and the acting talents of John Gielgud.

Bumping into a sophisticated actor in the boondocks near Alice would have been an amazing bit of good luck for writer Steinbeck. It could have really happened on Oct. 12, 1960.

But like a dozen other improbable/unbelievable meetings with interesting characters Steinbeck says he had on his 11-week road trip from Long Island to Maine to Chicago to Seattle to California to Texas to New Orleans to New York City, it almost certainly never did.

Steinbeck, the master American novelist and storyteller, was making stuff up in Alice. It’s possible he and Charley stopped to have lunch by the Maple River on Oct. 12, 1960, as they raced across North Dakota.

But unless the author of “The Grapes of Wrath” was able to be at both ends of the state at the same time or push his pickup truck Rocinante to supersonic speeds, Steinbeck didn’t camp overnight anywhere near Alice 50 years ago.

In the real world, the nonfiction world, on the night of Oct. 12 Steinbeck was 326 miles farther west of Alice. He was in the Badlands, staying in a motel in the town of Beach, taking a hot bath. We know this is true nonfiction because Steinbeck wrote about the motel in a letter dated Oct. 12 that he sent from Beach to his wife Elaine in New York.

Steinbeck’s non-meeting with the actor near Alice is not an honest slip up or a one-off case of poetic license being too liberally employed in the pursuit of making an otherwise true story seem truer or more interesting. “Travels With Charley” is loaded with such creative “fictions.”

Long before I arrived in the lonely aglands of Alice, long before I left on my own 43-day 11,276- mile pursuit of Steinbeck’s ghost, I knew “Charley” was full of it — fiction, that is.

I already knew Steinbeck’s beloved account of his travels was not really a nonfiction book, which is how it has been classified since the day it became an instant bestseller in 1962.

I already knew “Charley” was deliberately vague and fuzzy about time and place. Steinbeck — 58 and in poor health — took virtually no notes and discovered no great truths about the country as he sped across it, so he had to hide the truth about his actual trip and make up a lot of stuff.

And I already knew — OK, let’s say, “I already seriously suspected” — that most members of the perfect cast of characters he described meeting on his trip from New England to New Orleans were not real people but creations of a novelist’s imagination.

I didn’t learn these things because I’m a literary Woodward or Bernstein. I didn’t set out to get the goods on the great John Steinbeck or fact-check “Travels With Charley.” And I never intended to show that the basic storyline of “Travels With Charley” — world-famous author travels across the country alone, roughing it and camping out as he searches for the soul of America and its people — is a 48-year-old cultural myth.

My initial motives for digging into “Travels With Charley” were totally innocent. I simply wanted to go exactly where Steinbeck went in 1960, see what he saw on the Steinbeck Highway and then write a book about the way America has and has not changed in the last 50 years.

I had a lot of Steinbeck homework to do, and I did it. I read “Travels With Charley” — and immediately became suspicious about the credibility of almost every character Steinbeck said he met, from the New England farmers who sound like crosses between Adlai Stevenson and Descartes to the archetypal white Southern racist in New Orleans.

Using clues from the “Charley” book, biographies of Steinbeck, letters Steinbeck wrote from the road, newspaper articles and the first draft of the “Charley” manuscript, I built a time-and-place line for Steinbeck’s trip from Sept. 23, 1960 to Dec. 5, 1960.

The more I learned about Steinbeck’s actual journey, however, the less it resembled the one he described in “Travels With Charley.” Some really smart people, not just high school kids with road fever in their blood, believe parts of the prevailing “Travels With Charley” myth without questioning.

One is writer Bill Barich, author of “Long Way Home,” a new Steinbeck-themed book about his six-week road trip up the gut of middle American on U.S. Route 50 in 2008. He told the Los Angeles Times recently that he thought Steinbeck’s pessimistic view of the America he found in 1960 (but didn’t put into “Charley”) was partly a result of spending so much time alone on the road with only a dog and a cache of booze to keep him company.

That’s the prevailing “Charley” myth, but it’s totally wrong.

Based on my research, my drive-by journalism and my best TV-detective logic, during his entire trip Steinbeck was almost never alone and rarely camped in the American outback.

Steinbeck was gone from New York for a total of about 75 days. On about 45 days he traveled with, stayed with and slept with his beloved wife Elaine in the finest hotels, motels and resorts in America, in family homes, and at a Texas millionaire’s cattle ranch near Amarillo.

Adding up all the other nights we know Steinbeck stayed in motels, slept in his camper at busy truck stops or stayed with friends, etc., there were roughly 70 nights in which Steinbeck wasn’t alone in his camper in the middle of nowhere or alone anywhere else.

Since he also socialized for weeks with his pals and family while he was on the West Coast and in Texas, the real question is, “Was Steinbeck ever alone in the fall of 1960?”

Even when he was driving cross-country by himself, he wasn’t alone for long. He was constantly stopping for gas, stopping to talk to locals in coffee shops and bars and visiting places like the Custer Monument and Yellowstone Park.

So let’s see: 75 minus 70. That leaves about five nights of Steinbeck’s “Travels With Charley” trip unaccounted for. In the book, which is rarely reliable, he tells us he camped overnight alone on a farm in New Hampshire, in Alice, N.D., and in the Badlands of North Dakota. But he really didn’t; he almost certainly made up or heavily embellished those campouts under the stars.

Did Steinbeck actually camp out on a second farm in New England or near the Continental Divide along Route 66 in New Mexico? Did he sleep in his camper in the rain under that bridge in Maine? Did he really camp out on private land in Ohio and Montana?

Only his ghost knows for sure — but so what?

“Travels With Charley” has always been classified as a work of nonfiction, but no one ever claimed it was a “Frontline” documentary.

Does it really matter if Steinbeck made up a lot of stuff he didn’t do on his trip or left out a lot of stuff he did do? Should we care that “Charley” could never be certified as “nonfiction” today or pass Oprah’s Truth Test? All nonfiction is part fiction, and vice versa. It’s not like Steinbeck wrote a phony Holocaust memoir that sullies the memories and souls of millions of victims.

“Travels With Charley” is almost 50 years old. It’s got its slow parts and silly parts and dumb parts. It contains obvious filler, but in many ways it is a wonderful, quirky and entertaining book. It contains flashes of Steinbeck’s great writing, humor and cranky character and appeals to readers of all ages. That’s why it’s an American classic and still popular around the world.

It doesn’t matter if it’s not the true or full or honest story of Steinbeck’s quixotic road trip. It was never meant to be. It’s a metaphor, a work of art, not a AAA travelogue.

Steinbeck himself insisted in “Charley” — a little defensively — that he wasn’t trying to write a travelogue or do real journalism. And he points out more than once that his trip was subjective and uniquely his, and so was its retelling.

My work is done. I’ll let the scholars sort out whether Steinbeck’s ghost deserves to be hauled on to Oprah’s stage to defend himself for his 50-year-old crimes against nonfiction. I don’t know where John Steinbeck will take me next.

But I’m glad I got to take my own strange trip down his highway — and got to laugh out loud in Alice.

May 16, 2017

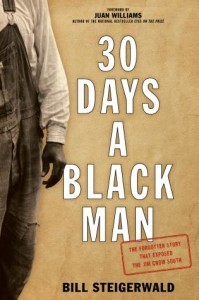

My new book — ’30 Days a Black Man’ — is about a star Pittsburgh newsman who disguised himself as a black man and went into the Jim Crow South in 1948

Ray Sprigle was a superstar newspaperman for the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette whose amazing undercover mission into the Jim Crow South in 1948 has been largely forgotten.

In my Lyons Press book 30 Days a Black Man I retell Sprigle’s great story, which is about the pre-TV civil rights movement, the triumphs and failures of black and white newspapers and the power of one journalist to start a national debate in the media over ending legal segregation.

Support your local bookstore or buy many copies online.

Six years before Brown v. Board of Education, seven years before the murder of Emmett Till, and thirteen years before John Howard Griffin’s similar experiment became the bestseller Black Like Me, Sprigle’s intrepid journalism blasted into the American consciousness the grim reality of black lives in the South.

It was my great pleasure — and duty — to elevate Sprigle’s groundbreaking exposé to its rightful place among the seminal events of the early Civil Rights movement.

Paul Theroux, the globe’s top travel writer and author of Deep South, blurbed about the book this kind way on the back cover:

This is a vivid, well-researched account of a journalistic coup. White Ray Sprigle passing for black in the Jim Crow South—the danger, the narrow escapes, the abuses, the revelations. But it is also a set of portraits: of the brave black men who helped Sprigle fulfill his assignment; a portrait of the Deep South; and a portrait of the United States in the late 1940s.

And Nick Gillespie, the culturally erudite editor of libertarian Reason.com and big fan of Dogging Steinbeck, wrote this in the intro to Reason’s podcast with me:

Steigerwald’s powerful new book … documents Sprigle’s expose and does a masterful job of recreating an America in which de facto and de jure segregation was the rule not just in the former Confederacy but much of the North as well.

February 17, 2017

Fall, 2012: When ‘Travels With Charley’s’ Publisher Quietly Admitted the Truth about Steinbeck’s ‘fake nonfiction’

This was originally written for the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette on Oct. 14, 2012, when the Penguin Group’s 50th anniversary edition of John Steinbeck’s “Travels With Charley” quietly came out with a slyly amended introduction by professor Jay Parini that admitted — after half a century — that “Charley” was a work of fiction, not nonfiction.

‘Travels With Charley’: now officially mostly fiction

There were no puffy press releases from John Steinbeck’s publisher. No stories in The New York Times culture pages or news flashes on feisty book industry blogs such as GalleyCat.

But after half a century of masquerading as a work of nonfiction, and after almost 1.5 million copies sold, John Steinbeck’s iconic road book “Travels With Charley” has quietly come clean with its readers.

Penguin Group, which owns the rights to Steinbeck’s works, didn’t quite come out and call “Travels With Charley” a literary fraud, as I did first in the Post-Gazette in December 2010 and five months later in Reason magazine.

But the company has been forced to admit that the beloved book about a great American writer traveling around the country in a camper with his poodle is so heavily fictionalized it should not be taken literally.

Before I detail Penguin’s confession, some background is in order. For the past two years I’ve caused trouble for a lot of the “Travels With Charley” fans, scholars and publishers who live on Steinbeck World.

It started innocently. In the fall 2010, as part of a book project to show how much America has changed in the past 50 years, I wanted to retrace faithfully Steinbeck’s 10,000-mile road trip. The Post-Gazette granted me a blog, “Travels Without Charley,” to chronicle the journey, and published a series of my pieces in the Sunday Magazine.

While doing research in libraries and reading the original manuscript of the book, however, I stumbled onto a 50-year-old literary “scoop.”

As I revealed in my Dec. 5, 2010, PG article “The Fabulism of ‘Travels With Charley,’ ” there were major discrepancies between Steinbeck’s actual road trip and what he wrote in the book.

Though it had always been marketed, sold, reviewed and taught as the true account of Steinbeck’s circumnavigation of the USA in the fall of 1960, “Charley” was not very true or accurate or honest at all.

It was not nonfiction. It was mostly fiction — plus a few lies and deliberate distortions thrown in by Steinbeck and his sly editors at the Viking Press to create the myth that he traveled alone, roughed it and spent a lot of time studying and thinking about America and its people.

It took a while for my charges against Steinbeck to escape the gravitational field of Pittsburgh. But in April 2011, five months after my article for the PG, The New York Times “discovered” me and made my accusations globally famous — for the usual 15 minutes.

Most of my fellow journalists praised me for my discovery. But I was cursed by Steinbeck groupies around the world for spoiling their fun with my fierce fetish for facts. It was hard to persuade them I didn’t hate Steinbeck or “Charley,” which, despite its lapses in the truth department, flashes with his great nature writing, wisdom and humor.

And some college English professors who believe the use of creative fictional techniques in nonfiction is a good and common thing dismissed me for wasting so much energy proving what they claimed was irrelevant or always obvious.

Penguin’s recent admission of the fictional genetic makeup of “Charley” was subtle — so subtle no one noticed it but professional-Steinbeck-watchdog me. It had been quietly slipped into the introduction of a new edition of “Charley,” which was released on Oct. 2 to co-celebrate the book’s 50th birthday and the 50th anniversary of Steinbeck’s Nobel Prize for Literature.

The lengthy introduction was first written for a 1997 paperback edition by esteemed Middlebury College English professor, author and Steinbeck biographer Jay Parini.

In his original introduction, Mr. Parini had pointed out Steinbeck’s heavy use of fictional elements, especially dialogue. Otherwise he treated “Charley” just as 2.5 generations of Steinbeck scholars had always treated it — as if it was the true and honest account of the author’s road trip and what he thought about America and Americans.

Into the latest edition, however, Mr. Parini inserted the cold truth:

“Indeed, it would be a mistake to take this travelogue too literally, as Steinbeck was at heart a novelist, and he added countless touches — changing the sequence of events, elaborating on scenes, inventing dialogue — that one associates more with fiction than nonfiction. (A mild controversy erupted, in the spring of 2011, when a former reporter for the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette did some fact-checking and noticed that Steinbeck’s itinerary didn’t exactly fit that described in the book, and that some of the people he supposedly interviewed, such as an actor at a campsite in North Dakota, never existed.)

“It should be kept in mind, when reading this travelogue, that Steinbeck took liberties with the facts, inventing freely when it served his purposes, using everything in the arsenal of the novelist to make this book a readable, vivid narrative.”

Naturally I was pleased to see that the truth had come out because of my efforts. Naturally I was not pleased to see that my name was not mentioned.

I sent a sarcastic email to Mr. Parini for making a mistake no rookie journalist would have made. Ignoring my serial insults, Mr. Parini took the classy, professorial road. He apologized profusely, near abjectly. I forgave him, though I really don’t know why.

It took half a century, and it cost me a lot of time and work and money, but at least the truth had triumphed. At least from now on anyone who buys a new copy of “Travels With Charley” will not be fooled.

December 1, 2015

Steinbeck is back home — and out of gas

The ‘Travels With Charley’ Timeline — Days 71 – 75

Friday, Dec. 2, 1960 – Upriver to Mississippi

Steinbeck writes in “Charley” that he left the Upper Ninth Ward, ate a sandwich by the Mississippi River and then stopped at “a pleasant motel.” The next day, most likely Dec. 2, he drives north on U.S. Highway 61 along the Mississippi River to Natchez and Vicksburg. Then he takes U.S. Highway 80 east across Mississippi.

Saturday, Dec. 3, 1960 – Pelahatchie, Mississippi

Steinbeck mails two postcards from Pelahatchie, Mississippi, on U.S. Route 80. One is to his agent, Elizabeth Otis, and one is to his editor, Pascal Covici. At dusk, 26 miles east of Jackson, I stopped on U.S. 80 to get a picture of the yellow brick Pelahatchie post office, where Steinbeck’s cards to his agent and editor had been postmarked Dec. 3, 1960. To his agent Elizabeth Otis Steinbeck wrote, “I’ll miss the coastal states but can’t have everything. Damned if I know whether I’m getting anything. At least I’ll know what’s not so.” The postcards are the last reliable evidence of where he was and when. He takes U.S. 80 into Alabama and picks up U.S. Route 11, which runs northeast along the Appalachian Mountains toward New York and home.

Sunday, Dec. 4 to Dec. 6, 1960 – The Home Stretch

Steinbeck meets U.S. Highway 11 in Alabama and slants through Tennessee and parts of Virginia, West Virginia and Maryland into Pennsylvania at Carlisle. He takes the PA Turnpike to New Jersey and arrives in New York City at the Holland Tunnel. In the book he says he’s denied entrance to the tunnel because of the propane tank aboard Rocinante. He takes the Hoboken Ferry, gets lost in evening rush hour in downtown Manhattan and has to ask a cop for directions to his house. In nearly 11 weeks, he had touched 33 states and driven about 10,000 miles. To start at Day 1 of Steinbeck’s trip, go here.

Home at last

Angling northeast on U.S. Route 11, shadowing the Appalachian Mountains, Steinbeck pushed hard for home. He says he drove in a blur, stopping only to sleep for a few hours at a time. The last town he mentions in the book is Abingdon, Virginia, 650 miles short of New York City. Abingdon is where he says his trip in search of America ended in a kind of road-weary amnesia, but of course it had effectively ended seven weeks earlier in Seattle. No matter.

My best guess is that Steinbeck staggered into New York City on about Dec. 5 or 6. He had been gone roughly 75 days. He had racked up about 10,000 noisy, butt-busting miles in his beloved Rocinante, which he quickly sold. He was out of gas physically and psychically. He had gone in search of America and its people and knew he had found neither….

In the late summer of 1962 his book “Travels With Charley” debuted on the New York Times Top 10 nonfiction list, hit No. 1 for a week in October list and stayed on the list for more than a year. It has sold about 1.5 million copies. In 2012, when its publisher Penguin Group published a 50th anniversary edition of “Charley,” the introduction was edited to alert readers that what they were about to read was a highly fictionalized account of Steinbeck’s actual trip.

— Excerpted from “Dogging Steinbeck”

November 30, 2015

Steinbeck is sickened by racism in New Orleans

The ‘Travels With Charley’ Timeline — Day 70

Thursday, Dec. 1, 1960 – New Orleans, Upper Ninth Ward

Steinbeck says in “Charley” he wanted to go to New Orleans to witness the anti-integration protests at a public school. Though he actually left from his wife’s sister’s place in Austin, which is 500 miles west of New Orleans, in the book he describes picking up Charley at the vet in Amarillo and driving south and east across Texas to New Orleans, a total of 1,000 miles. Hardly sleeping, he says he traveled in the bad ice storm that actually did hit southeast Texas Nov. 29 and 30. He writes that he arrived in “frozen-over” Beaumont, Texas, at midnight and in Houma, Louisiana, at dawn. In New Orleans that morning he says he parked Rocinante and took a cab to William Frantz Elementary in the Upper Ninth Ward. To start at Day 1 of Steinbeck’s trip, go here.

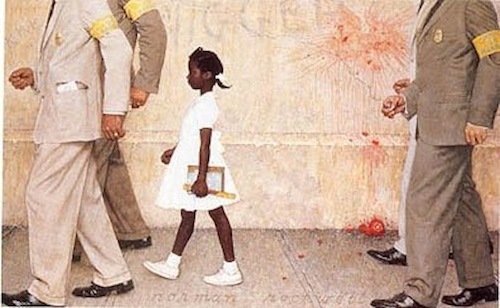

Steinbeck goes to schoolWilliam Frantz Elementary – then an all-white school in a virtually all-white working-class neighborhood – was making national headlines. The city of New Orleans had taken its first token steps to integrate its public schools. The crowded grade school was ground zero in a bitter civil rights battle that segregationists and white parents could never win but were viciously fighting anyway.

On Nov. 14, 1960, the city’s color barrier was broken at William Frantz by little Ruby Bridges, the 6-year-old first-grader immortalized in Norman Rockwell’s painting “The Problem We All Live With.” Three other first-grade girls integrated a second school in the Lower Ninth Ward. When Bridges, escorted by beefy federal deputy marshals, showed up at William Frantz in her little white dress and white socks, it was like a bomb went off under Jim Crow’s bed.

The white teachers in the school immediately quit. White parents pulled their kids out and began mounting large daily protest rallies in front of the building that included racist signs, spitting, slashing tires and throwing rocks. Two days later thousands of white extremists and teenagers went on a rampage in downtown New Orleans and, as the whole nation watched, a Southern city thought to be (relatively) progressive on matters of race was turned upside down and disgraced.

Steinbeck was following these events from Texas as he prepared to make his dash home to New York. He decided he had to witness the ugly drama playing each morning outside William Frantz Elementary. He was especially interested in the well-publicized “Cheerleaders.” He characterized them as “stout middle-aged women,” but from the old newspaper photos and newsreels they looked like mostly young, white working-class mothers. The mothers stood across the street behind barricades yelling crude obscenities at Ruby Bridges and the few white parents who braved the boycott by walking their kids into the virtually empty school.

On what was probably Thursday, Dec. 1, 1960, Steinbeck writes that he arrived in New Orleans, parked his truck and took a cab to the school. He says he joined the morning circus at exactly 8:57. That was the time Ruby Bridges arrived each day. The barricaded sidewalks and streets were crowded and angry. Police were there to keep people from being hurt. Local and national media were there in force….

Going to New Orleans to see the Cheerleaders in action was the only deliberate act of journalism Steinbeck made on his entire trip, and it paid off. It gave his book of fictional encounters, musings and memories some needed punch and passion and a newsy edge. Not to mention a welcome dose of reality.

Being where real people are doing real things always has a way of producing strong writing, whether you’re a newspaper reporter covering a house fire or a great novelist covering a race war. Steinbeck’s Cheerleaders scenes, unlike any other in the book, prove it. In probably less than an hour, he found a powerful ending for “Charley” without having to rearrange the real world much at all.

— Excerpted from “Dogging Steinbeck”

November 20, 2015

The Steinbecks feast in Texas

The ‘Travels With Charley’ Timeline — Days 60 – 69

Monday, Nov. 21 to Nov. 29-30, 1960 – Texas

Steinbeck says in “Charley” he spent “three days of namelessness at a beautiful motor hotel” in the middle of Amarillo while the broken front window of his camper shell was repaired. He says Charley was sick and was left with a kind vet for four days. Elaine flew in to rejoin him in her home state of Texas and the pair went to her ex-brother-in-law’s cattle ranch in nearby Clarendon, arriving the day before Thanksgiving. Steinbeck doesn’t say in the book how long he stays at the ranch and never mentions that afterwards the Steinbecks drove 400 miles south to Austin to visit Elaine’s sister until the end of the month.

Where the Steinbecks spent Thanksgiving 1960Though two buildings were new and many upgrades had been made, it was clearly the place Steinbeck described in “Charley.” The main structure, a long one-story redbrick house, had a big screened-in porch overlooking a trout pond surrounded by trees. The great room had a white-brick fireplace and a high white ceiling with heavy beams. Each of the three bedrooms had a Texas-size bed, its own bathroom and a door to the outside.

It was like a little motel, only in 1960 the regular guests were members of Texas’ richest cattle families. The showroom of heavy wood outdoor furniture on the covered patios was worth more than my house. Yet, notwithstanding the “Dallas” stereotypes, nothing inside or out was ostentatious or in bad taste, just expensive and heavy.

Enjoying the sun and wind and park-like setting, I tried to imagine what it was like to be a vacationing cattle baron. I couldn’t. My hat was too small. But I didn’t need to imagine anything, since Steinbeck did a thorough job of detailing the cattle-baron lifestyle in “Travels With Charley.” When Steinbeck writes about something he really did on his trip, you can usually tell. Instead of inventing pages of wooden dialogue, he delivers detail.

— excerpted from “Dogging Steinbeck”

One of the ranch’s bedrooms in 2010.

The living room with fireplace in 2010.

November 14, 2015

Route 66, Bound for Amarillo

The ‘Travels With Charley’ Timeline — Days 55 – 60

Tuesday, Nov. 15 to Sunday, Nov. 20, 1960 – Monterey to Amarillo

Steinbeck leaves the Monterey Peninsula on Tuesday, Nov. 15, bound for Amarillo, Texas, which is 1,333 miles away. Elaine flies on ahead. With his boyhood friend and lawyer Toby Street riding with him in Rocinante, Steinbeck goes through Los Banos, Fresno and Bakersfield. He crosses the Mojave Desert and picks up Route 66 at Barstow, California. After four days, Street leaves him in Flagstaff, Arizona

. Steinbeck

writes in “Travels With Charley” that he drove the last 600 miles to Amarillo on Route 66 as fast as he could. Dejected, he admitted to himself that he was “pounding out the miles because I was no longer hearing or seeing. I had passed my limit of taking in or, like a man who goes on stuffing in food after he is filled, I felt helpless to assimilate what was fed in through my eyes.” He says he

camped alone in a canyon near the Continental Divide east of Gallup, New Mexico

.

Riding the ‘Mother Road’ to Texas

What’s left of Route 66.

Like Steinbeck 50 years before, I slipped out the back door of the Monterey Peninsula. East into the dry gut of central California I sped along state routes 156 and 99. They were the same roads Steinbeck took on his way east to a Thanksgiving holiday at a cattle ranch near Amarillo, Texas, only my asphalt – per usual – was smoother, wider and safer.

By Saturday night, I had made it past Fresno and Tulare to a $62 motel in Bakersfield. The next morning I breezed south through flat, arid, dead valleys on Route 58. Dodging grassy tan mountains, passing beneath a forest of wind turbines stretched across several ridge tops, I skirted the town of Mojave, slipped by the edge of Edwards Air Force Base and drove through the bleak Mojave Desert to the crossroads town of Barstow.

At Barstow, Steinbeck met U.S. Highway 66, his “Mother Road” from “The Grapes of Wrath,” and followed it all the way to Texas. I-40 has replaced, covered or bypassed Route 66, which no longer officially exists. But long, desolate stretches of the historic and culturally powerful road still parallel the interstate. Old Route 66 comes back to life when it becomes the main street of traveler-centric desert towns like Gallup, Winslow, Kingman and Winona. Jazzman Bobby Troup made those dusty places hip & famous forever with the lyrics of his swinging 1946 hit “Route 66,” which Nat King Cole sang first and the Rolling Stones, John Mayer and dozens of others have covered.

If any road in America deserved to be worshipped, it was old Route 66. Starting in the 1930s, and until the western interstates were completed in the 1970s, it was the only practical east-west route by car from Chicago to L.A. Route 66 made it possible for migrants of every socioeconomic class to reach for the golden promises of California, not just the desperate migrants in the “The Grapes of Wrath.”

— Excerpted from “Dogging Steinbeck”

October 30, 2015

John, Elaine and Charley relax in Monterey

The ‘Travels With Charley’ Timeline — Days 40 – 55

Monday, Oct. 31 to Nov. 15, 1960 – Monterey Peninsula/Pacific Grove

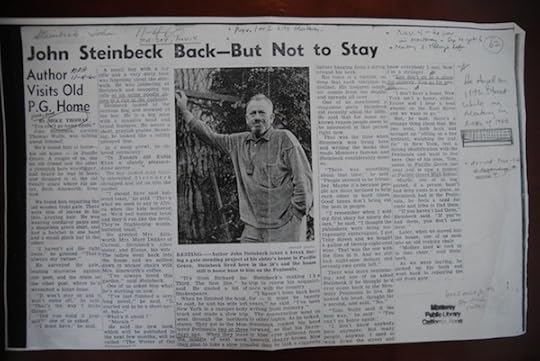

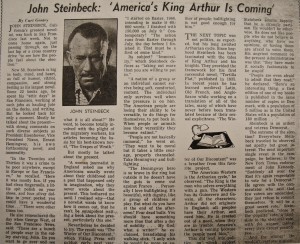

The Steinbecks – John, Elaine and Charley – stayed for two weeks with his sister Beth at the modest Steinbeck family cottage two blocks from the ocean in Pacific Grove. After not having been in Monterey for about 20 years, he visited the remnants of the once thriving sardine industry on Cannery Row, the official new name for Ocean View Avenue. In his book he says he returned to one of his favorite bars on Alvarado Street (the Keg) and went with Charley to the top of Fremont Peak. He was interviewed and photographed at the cottage by the Monterey Peninsula Herald. The newspaper article, “John Steinbeck Back – But Not to Stay,” ran Nov. 4, 1960, and included a photo of Steinbeck standing in the garden of the cottage with a cigarette in his mouth. To start at Day 1 of Steinbeck’s trip, go here.

The Steinbeck Family CottageOn 11th Street I parked across from the Steinbeck family cottage. Except that it was probably the least renovated and shabbiest structure on the block, it fit in well with its cramped neighborhood of little yellow-and-dark-green-trimmed stucco houses on micro-lots. Two blocks from the surf, with a low gray wood fence at the sidewalk and a dense side garden, it had been remodeled by Steinbeck so it’d have no door to the street.

His father, who was neither poor nor un-influential, built the red-and-white cottage early in the 20th century. Steinbeck lived there with his first wife Carol from 1930 to 1936, when he wrote books like “The Red Pony” and “Tortilla Flat” that made him nationally known. Though it was still owned and used by Steinbeck heirs, no one was there when I dropped by to snoop. It was just as well, since all I wanted to do was take photos.

In 1960 the Traveling Steinbecks were at the cottage for only a day or two when the Monterey Peninsula Herald dispatched a writer and photographer to do a story. The resulting feature, which ran in the Nov. 4 paper, was very well written by Mike Thomas and included a photo of Steinbeck standing in the garden with a cigarette in his mouth.

Thomas found Steinbeck fixing a wooden front gate, which the author said he had probably built himself 30 years earlier. Describing Steinbeck as a big man with broad features, piercing blue eyes, graying hair and small goatee, Thomas said he was wearing corduroy pants and a shapeless green sweater.

His fingers were nicotine stained and he had a Zippo cigarette lighter on a string around his neck. Wife Elaine was there. So was “an aging poodle sitting in a car at the curbside.” When Thomas asked if he would ever move back to the Monterey area, Steinbeck said he felt like a stranger on the peninsula and repeated his Thomas Wolfe mantra – “You can’t go home again.”

****

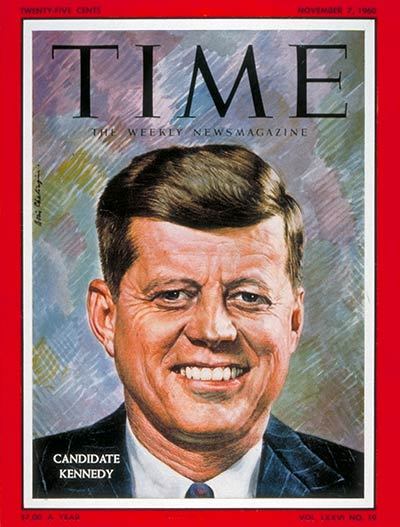

Election Day, 1960Going into Election Day, the presidential race was close in both California and the nation, with Kennedy leading Nixon in the Time and Newsweek polls. On Nov. 2, with six days to go, JFK came through San Jose on his way to a fundraiser in San Francisco and Nixon was about to fly into Fresno. The Peninsula Herald put its endorsement of Richard Nixon and Henry Cabot Lodge at the top left of its front page. It ran the same recommendation on Page 1 every day for the next six days.

The plug for “Tricky Dick” may have helped Nixon take Monterey County by a 56-43 majority and narrowly carry the state by 35,000 votes out of 6.5 million cast. But it couldn’t sway Steinbeck. On Nov. 8, he cast an absentee vote. Unless he wrote-in the name of his hero Adlai Stevenson, he voted for John F. Kennedy.

Two months later he’d attend JFK’s inauguration and begin his personal relationship with Kennedy and LBJ. Steinbeck would be pleased to know the voters of Steinbeck Country have done a political 180 in the last half-century. In 2008 they voted 66-33 for President Obama, a nail-biter compared to the 80-20 Obama landslide in San Francisco….

Steinbeck’s Partisan PoliticsPart of John Steinbeck’s original mission had been to take the political pulse of the country. He was quickly disappointed to find how difficult that was. As he wrote in his first draft, he was saddened to learn that the greatest number of Americans he saw “did not have political opinions, or if they did, concealed them whether out of fear or expediency I do not know.”

Their silence didn’t stop him from lacing his original manuscript with his running commentary on the election, which he obviously followed closely. He was a stanch New Deal Democrat and didn’t pretend otherwise. In the first draft of “Charley,” he wrote, “It must not be thought that my wife and I are or were nonpartisan observers. We were and are partisan as all get out, confirmed, blown in the glass democrats and make no bones about it.”

That confession was axed. So was nearly every overt political comment or crack he put in the first draft. For example, all four televised Nixon-Kennedy debates occurred while he was on the road. Based on his letters and the original manuscript, he saw or heard each one in full or in part.

A Stevenson Man until the bitter end, Steinbeck didn’t swoon over the prospects of a President John Kennedy. But he loathed Nixon, as the manuscript repeatedly makes clear. At one point, after watching a Nixon-JFK debate on the big TV in his motel room, he criticized Nixon and Herbert Hoover and went on for about 150 words, making fun of their pedestrian Republican reading habits and comparing their low intelligence levels to Kennedy’s high one. “Being a democrat,” he wrote without capitalizing Democrat, “I wanted Kennedy to win….” That scene was axed.

Also cut was his commentary following the third presidential debate, which he watched in his room at a “pretty auto court” in Livingston, Montana. He sarcastically asked himself if Montanans had any real interest in the major geopolitical issue of that debate – whether the United States should defend the tiny islands of Quemoy and Matsu, which the Red Chinese were shelling and threatening to take from Taiwan. Other political comments he made in San Francisco, Monterey and Amarillo – some of them refreshingly bipartisan in their cynicism – were chopped out completely. So were two pokes at the John Birch Society, a favorite punching bag.

Though it took some of the edge away from an already nearly edgeless book, cutting 99 percent of the presidential politics from “Travels With Charley” was smart and logical editing. First of all, by the time the book would hit bookstores – in late July of 1962 – the 1960 election was ancient history. Who would care by then what Steinbeck thought about the third JFK-Nixon debate?

Plus, his political sniping was petty and one-sided, though that probably bothered no one at the Viking Press. It was also boring and at odds with the rest of the book’s grouchy but generally likable tone. The trouble was, removing all of the politics left a glaring hole in what was supposed to be a nonfiction account of what was going on in the nation….

— Excerpted from “Dogging Steinbeck”

October 26, 2015

The Steinbecks meet the press in San Francisco

The ‘Travels With Charley’ Timeline — Days 36 – 39

Thursday, Oct. 27 to Oct. 30, 1960 – San Francisco

According to famed city columnist Herb Caen, the Steinbecks arrived in San Francisco on Wednesday evening, Oct. 26. They socialized with John’s friends and stayed at the posh St. Francis Hotel downtown through Oct. 30. He was interviewed in his suite on Oct. 28 by Curt Gentry, a freelancer for the San Francisco Chronicle’s book section. On Sunday Oct. 30, John, Elaine and Charley move down the coast to the Steinbeck family cottage in Pacific Grove. Day 1 of Steinbeck’s trip was Sept. 23, 1960.

The ‘pure grandeur’ of the St. FrancisThe Westin St. Francis in 2010.

Steinbeck had no intention of zipping past his favorite city without partaking of its pleasures. He spent four busy days downtown, staying at the handsome St. Francis Hotel in Union Square.

Apparently, booking a room in San Francisco had been difficult even for him because of conventions. If scenes cut from the book’s first draft can be believed, Elaine made several fruitless calls ahead to hotels from roadside pay phones before they landed a suite at the St. Francis, where Caruso, Fatty Arbuckle and Hemingway had once been regulars and Steinbeck was a familiar face.

In the deleted scenes, Steinbeck described arriving with Elaine via U.S. Route 101 and the Golden Gate Bridge. After getting lost for a while, he found his way to the St. Francis downtown. Now the Westin St. Francis, it has undergone many cosmetic changes since 1960. But in 2010, when I prowled its halls and stairways, it still had dark wood, heavy rugs, mirrored ceilings, monstrous chandeliers and a two-ton shoeshine stand. Everything else – the floors, the back steps, walls – was made of marble.

Curt Gentry wrote a long article for the San Francisco Chronicle after his meeting with Steinbeck at the St. Francis during his five-day rest stop.

Steinbeck wrote that he parked Rocinante at the luxury hotel’s entrance – and just left it there, where it was in the way and attracting the wrong class of attention. He went straight to his hotel room and jumped in the bathtub with a whisky and soda at his side. He really enjoyed sitting in bathtubs with whiskies and sodas.

In the cut scenes Steinbeck purred that the spacious suite was “pure grandeur.” He was pleased to find no Formica, no plastic, no cheap ashtrays in the St. Francis, which in 1960 was already old, prestigious and, as he admitted, “outmoded” and “trapped in an ancient and primitive way of doing things.” He wasn’t complaining about the hotel’s old ways. Eating in the living room on white linen, he was pleased in his first draft to report being attacked by an army of servants – “valet, waiters, maids, pressers, housekeeper.”

Apparently, after her punishing ride in Rocinante and a week’s worth of rustic resorts, Elaine was back in her idea of lodging heaven. She preferred well-staffed English country inns to the “do-it-yourself” style of the modern American motel, where you had to fetch your own ice at the end of the hall and lug your own luggage. “My lady wife was very pleased,” Steinbeck wrote.

As he sat in his bathtub “like a sunburned Buddha,” Steinbeck wrote, the phone rang. It was the doorman. Rocinante was blocking traffic and it didn’t fit in the underground parking garage across the street under Union Square. What should be done with it? The unsightly pickup truck was moved to a parking lot and the hotel scenes end with Elaine calling the hairdresser. It’s not hard to understand why this glimpse of the Steinbecks indulging themselves on the road was purged from the book. And where was faithful Charley in these dropped scenes? His presence at the St. Francis was never mentioned. Apparently he’d already been checked into a kennel.

***

Portrait of an ImmortalDuring his stay in San Francisco, Steinbeck was filmed along the Pacific Coast doing a brief stand-up introduction for a movie made from his short story “Flight.”

The great columnist Herb Caen, who in 1958 coined the word “beatnik” to describe the Beat Generation, also captured a sharp, mid-trip portrait of John Steinbeck. Caen’s breezy, literate daily column of insider gossip and smart-alecky opinion about the city he called “Baghdad by the Bay” was a must-read for decades until his death in 1997. In his Oct. 30 column he detailed the recent afternoon encounter he had with Steinbeck at Enrico’s sidewalk cafe, where Caen ate lunch nearly every day.

“John Steinbeck, well-nigh immortal writer, was there, looking distinguished, like/as a writer should. Pinstriped suit. Black hat. Silver-topped cane. And a handsome beard.” Caen quoted Steinbeck’s explanation for the beard: “‘Hemingway wears a beard because he has skin cancer. My reason is pure vanity. The cane? I broke my kneecap four times.’”

Steinbeck, pushing away his lunch and ordering a beer, told Caen what he was up to:

“‘I drove across the country in a campwagon. Alone. My wife met me in Seattle. I’ve been living in New York – that’s not America – and Europe. I hadn’t seen my own country in twenty years. I wanted to get to know the people again, hear how they talk and feel. You can’t live on memories.’ ”

Steinbeck also told Caen that the American people “‘are disturbed, plenty. They feel nobody in Washington has been telling them what’s going on. I think Kennedy will win. It’s like writing a play – you can’t fool people. You can get away with a sensational play, maybe, but not a bad one. Nixon is a bad play, the kind you don’t believe.’”

Caen said Steinbeck “lit a cigarette with a lighter strung around his neck on a black cord” and raved about the “magnificent” beauty of the country, especially Montana. Other topics included Steinbeck’s upcoming novel about America’s lack of morality and a few semi-humorous asides. Charley and Elaine were not mentioned, though they were probably there.

Caen’s brief detailed depiction of Steinbeck, like Gentry’s longer portrait, is telling. It also almost single-handedly destroys the “Travels With Charley” Myth. The “well-nigh immortal writer” Caen met – dressed flamboyantly for lunch in one of the hottest eateries in town – was not the grizzled romantic road warrior of “Travels With Charley.” Nor was he lonely, depressed or sickly. Nor was he roughing it, trying to lay low or searching very hard for America.

— Excerpted from “Dogging Steinbeck”

October 20, 2015

The Steinbeck Family spends quality time with California’s redwoods

The ‘Travels With Charley’ Timeline — Day 29 – 35

Friday, Oct. 21 to Oct. 26, 1960 – The Pacific Coast Highway

There are virtually no hard clues to determine where the Steinbecks stopped as they came down the Pacific Coast through redwood country to San Francisco. Based on scenes deleted from the book’s original manuscript, once they crossed the California line they stayed for at least two days at a large, nearly empty resort in the shade of redwoods. The only reliable clue is a postcard Steinbeck mailed on Monday, Oct. 24, 1960, to his editor Pascal Covici from Trinidad, California, where he said he and Elaine were staying the night in a motel by a redwood grove on U.S. 101, about 300 miles north of San Francisco. Day 1 of Steinbeck’s trip was Sept. 23, 1960.

Not ‘Travels With Elaine’

It was on the West Coast that “Travels With Charley” reached its height of deception. In the real world, John, Elaine and Charley made their slow trip down to San Francisco in their overloaded pickup truck. But in the book Elaine is not there. It is only the author and his faithful poodle who visit Seattle, fix a flat tire on a rainy Sunday in Oregon and commune with the great bodies of the redwoods.

It wasn’t that way at all in the original manuscript, which co-stars Elaine and reads like the travel log of the Duke and Duchess of Sag Harbor. As soon as she made it to Seattle, Elaine – aka “my wife” – is in about six straight scenes at the waterfront and on the road. Some of those scenes were dropped completely and some were retained, but her presence was stripped out.

One scene completely dropped from the first draft mentions “the several days” Mr. and Mrs. Steinbeck stayed “at a partially closed resort in a big redwood grove.” Holed up in “a cottage at the base of a cluster of monster trees,” he wrote that he was sore and scraped up after having to flounder in “thick yellow muck” while fixing Rocinante’s flat tire, which he said he did as Elaine sat in the cab reading a book.

Steinbeck wrote that the cottage in the redwoods seemed like “the perfect place to rest and refurbish our souls.” Apparently, he was halfway to heaven. As he soaked in “a tub of near boiling water,” he wrote, “My lady wife slipped in and set a scotch and soda on the edge of the tub. And the world and the people there of, the grasses and the trees became very beautiful.”

Another completely dropped scene does not reflect well on Steinbeck’s vaunted love for the common man. After he and Elaine hear about a good restaurant nearby, they decide to get dolled up and do the “town.” They were disappointed to find that the eatery in the sticks of Northern California was not a Trader Vic’s franchise but a neon hellhole. Sounding like an old fogey, Steinbeck wrote that the restaurant possessed “every damnable feature of our civilization – cold glaring light, despondent roaring music from a cathedral juke box, batteries of coin machines, Formica counters and tables. One wall was a cemetery of ugly … pies.”

Great descriptive writing, as usual. But when Steinbeck – who rarely let a commoner he meets on his journey escape without uttering a “he don’t” or a “them people” – made fun of the waitress for saying “fried tatters” and “We ain’t got no (liquor) license,” he doesn’t sound like a friend of the working class. Later he was happy to report that while he and Elaine slept close to the redwoods, there were “no trippers, no chattering troupes with cameras” to spoil their stay. The entire restaurant tragedy was easily snipped from the final version of “Charley.” But excising Elaine from the other scenes posed a larger editorial problem. On the West Coast, whenever he writes “we” in the book he was originally referring to himself and Elaine, not himself and Charley.

Speaking of poor Charley, he all but disappears from the first draft once Elaine takes over the passenger seat. It became so obvious to some folks (i.e., the editors or Steinbeck’s agent) that the poodle was missing that Steinbeck felt obligated to explain to the reader where Charley went. He handwrote a short chapter – obviously never published – answering the criticism that Charley was being ignored and assuring everyone he was feeling fine. He explained that with the missus onboard, the standard Steinbeck family pecking order had reasserted itself: “When Charley and I traveled alone together, the dog was indeed man’s best friend. But Charley knows better than anyone when the wife is present, he is man’s second best friend, and he finds this a normal relationship and perhaps a better one.”

In the end, Charley was restored to top billing and Elaine’s presence on the West Coast for four weeks was completely eliminated. It was editorially smart – and necessary – to dump the duchess. First of all, the scenes focusing on her were boring as hell. But most important, she seriously undermined the book’s romantic conceit. With her by his side every night, Steinbeck was no longer the man alone. He was a love-struck honeymooner.

— Excerpted from “Dogging Steinbeck”