Eugene Salomon's Blog

May 24, 2021

The Comment That Went Viral

I subscribe to the online edition of the New York Times. There's a feature in it of which I'm particularly fond -- the comments section. Roughly half the articles, and nearly all of the Op-Eds and Guest Essays, have one. On any given day there are thousands of comments from readers -- in fact, sometimes a single article by itself may receive over a thousand. It's like the old "Letters To The Editor" of the print era on steroids.

It's easy to make a comment. Here are the rules of the game:

-- comments are moderated for being "on-topic" and "civil";

-- they cannot exceed 1500 characters;

-- each article which permits comments has a time limit for submissions. If you get to it too late, it will be closed;

-- you can make a comment to a comment (a "reply"). Thus discussions occur among commenters.

-- comments can be "flagged" by readers as inappropriate. They may then be removed by moderators.

-- you can click "Recommended" beneath a comment if you really like it. These "Recommended" comments can then be viewed in a window of their own when you click on "Reader Picks". They're listed in order of which got the most. This creates a popularity contest of sorts among the readers.

-- there's also a section called "NYT Picks". Click on that and you will see the comments chosen as most deserving of attention by the moderators of the Opinions Section.

-- and finally there's an icon for "All" comments, listed in chronological order.

Because the Times is one of the most widely read and respected papers in the U.S. (and the world), it attracts readers who are often quite well-versed in the subjects being written about and their comments may offer a new perspective that had been overlooked by the author of the article. It tends to be a smart crowd.

I consider myself well-versed in certain areas: New York City in general; taxi driving and the taxi business; transportation; and, of course, my own experiences with the human race as a longtime NYC taxi driver. If I feel I have something relevant to say to an article in these zones, I will often make a comment using the pen name "Old Yeller".

So here's what happened...

On August 24th last year the Times ran an Op-Ed by Jerry Seinfeld called "So You Think New York Is 'Dead' (It's not.)"

In his piece Jerry came down pretty hard on "some putz in LinkedIn" (the owner of a comedy club in Manhattan who, after relocating to Miami, had written what was basically an obituary on the city.) Jerry kicked the guy's butt, so to speak, and made a good case for the city's resilience and revival. Before the comments section was closed it received a whopping 2,740 comments. One of them was mine. And thus began the journey of a comment...

-- I started my day on August 24th as I always do, reading the Times over breakfast. And after breakfast. I did not see Jerry's Op-Ed.

-- Later in the day I received an email from my buddy in the U.K., Jodie Schofield, alerting me to Jerry's article and providing a link. How could I have missed this? I read the article, loved it, and immediately wrote this comment:

"I've been a NYC taxi driver for many, many years. My favorite type of ride is the rare one of picking up a man who has just emerged from a hospital following the birth of his first child. It is the best day in his life and I usually find it difficult to hide my own tears of joy as he tells me all about it.My second favorite ride is similar. It is a young person with a dream who is coming to New York City for the very first time. I am the taxi driver taking him or her to Manhattan from the airport. I insist on the Upper Level of the 59th Street Bridge as our route. Excitement grows as the city grows larger and larger as we approach Manhattan. Finally, almost at ground level, the ramp takes us so close to the surrounding buildings that we can actually see the people inside. Touching down on E. 62nd Street, my newly minted New Yorker is experiencing for the first time the "energy" that is so often spoken of. It's like watching a child approaching a roomful of birthday presents. All things are possible. It will take more than a crumby pandemic to change that."

-- About 15 minutes after I submitted the comment I received an email from the Times telling me it had been approved. (Normal procedure, they do that for every comment they publish.)

-- An hour later I checked the comments section of Jerry's article to see if I'd received any "recommends" or, better yet, if my comment had been chosen as a "NYT Pick". It had received a handful of recommends but was not a NYT Pick. Oh, well.

-- After another hour, I checked again. I discovered that my comment had miraculously been switched from the "All" section to the "NYT Picks" section! Wow, that never happens, at least not to me. Wondering what could have caused this momentous turn of events, I found that a reader named Flaminia from Los Angeles had made this reply to my comment:

"@Old Yeller, THIS should be a Times pick."

Apparently a moderator agreed. In the contest of Which Comment Gets The Most Recommends, this is a big deal. The elite "NYT Picks" comments are seen by more readers than the ones in the "Reader Picks" and "All" parts of town. More views means more Recommends.

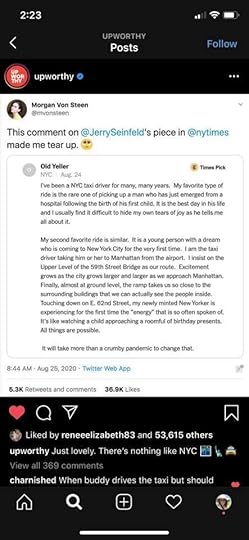

Unbeknownst to me, a fire was being lit. I'm not sure of the exact timeline, but as far as I can tell it began in the morning of Aug. 25th with a tweet from Morgan Von Steen (@mvonsteen, who tweets about "design & technology in government, especially New York"). She tweeted:

This comment on @JerrySeinfeld's piece in @nytimes made me tear up. [image error]

And then she posted the comment itself.

As the day went on, Morgan Von Steen's tweet generated over 9,000 retweets, more than 1,400 Quote Tweets, 76K likes, and a swarm of comments, many reminiscing about their own first ride into Manhattan, their ride in a taxi on the day their first child was born, and especially about their love affair with New York City.

We were off to the races.

-- Upworthy.com on Instagram posted Morgan Von Steen's tweet, generating another 53K likes.

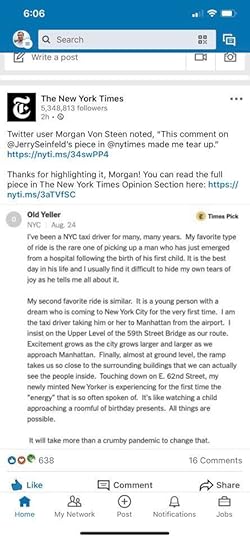

-- The attention the comment was generating got on the radar of the NY Times Opinion Section people. They highlighted it on LinkedIn.

-- My daughter, Suzy, and my nephew, Sanjay, alerted me that my comment was apparently going viral. That was exciting, but, wait! People reading it would only know that some cab driver in NYC calling himself "Old Yeller" had written it. I want people to read my book and my blog, of course, and they don't know that "Old Yeller" is me. Some clever way to identify myself was needed...

-- I went back to the replies to my comment in the NYT Picks. I discovered that Patricia Caiozzo from Port Washington, New York, had written: "@Old Yeller. Your post is excellent. Perhaps you write in your free moments? You should." Perfect. I replied: "@Patricia Caiozzo. Thanks, Patricia. In fact, I do. I have a blog called 'Cabs Are For Kissing'. Hope you'll stop by." And then I added a link to my blog. So with that, not only readers of the Times could find me, but the moderators of the Opinions Section could, too. For the next few days, presto, the hits on my blog went out the roof.

-- At the same time Suzy got on Twitter to inform commenters who were wondering who this "Old Yeller" guy is, and shouldn't he write a book or have a column in Times or something, that Old Yeller is her father and he did write a book, and here's the name of the book, and he has a blog, too, and here's the link to that. (This is why you have children.)

-- Jodie in the U.K. also jumped in on Twitter, referring readers to my blog.

-- A few hours later Sanjay alerted me that Gov. Andrew Cuomo had retweeted Morgan Von Steen's tweet and had added:

Governor Andrew Cuomo August 25, 2020 · The naysayers have predicted the “decline” of New York before. They have always been proven wrong — and they will be again.Read this beautiful comment written by a NYC taxi driver on Jerry Seinfeld's New York Times op-ed.#NewYorkTough-- My head was beginning to swell. Governor Cuomo, wow! It was almost enough to make me forget that he had renamed the new Tappan Zee Bridge after his own father.

-- And my head-swelling problem was not helped when an article from the online business magazine Fast Company was brought to my attention, claiming that "the best thing about about Jerry Seinfeld's 'NYC Is Not Dead' article is this cab driver's response" (click here for that.) Could my comment have upstaged the great Jerry Seinfeld? Is that possible? I'm thinking I may need to have the doors in my house widened so my head can fit through.

-- To make matters worse, there was this from supermodel Bella Hadid, with 32 million followers on Instagram:

-- And then her sister, Gigi, another supermodel, did the same. 50 million followers on Instagram.

-- On Aug. 26th, more media attention in this article in the Daily Mail in the U.K.

-- After that it became difficult, if not impossible, to figure out the numbers the comment generated. If there's some way of calculating this I'd like to know about it, but I guess it's safe to assume it must have been in the millions.

NY Times Interview

On Aug. 27th I heard from Shannon Busta, an editor on the NY Times Opinion Desk, informing me that as far as she knew this was the first time a comment to an article in the Times had ever gone viral, and asking if I'd be interested in being interviewed. I was. It was half an hour, live -- which is the interview equivalent of walking on a tightrope.

Click here to see the interview.

Why Was The Comment So Popular?

For one thing, it was short and to the point.

It was written at a time when virtually the entire human race was suffering from a mutually shared reality, and with no end in sight.

More than that, I think, it was because it has the power to rehabilitate the personal purpose line lying dormant in the minds of those who read it. There are certain people -- you could call them dreamers or creatives -- who at some point in their lives have had an epiphany. They have discovered exactly what their purpose is in this lifetime. They have made a promise to themselves to pursue that purpose, no matter what it takes. For many, this means coming to New York City. The skyline of New York, one of the great sights of the world, is symbolic of that dream. To recall that first moment they ever laid eyes on it is to blow apart the barriers that have been holding them down and bring their purpose back to life.

You could just about raise the dead with that.

Two Concise Paragraphs

I've been asked where the full versions of the two stories that are tightly packaged into the comment can be found. The story of the "newly minted father" is in this blog. It was published on March 16, 2013. Go to The Best Day of Your Life.

The story of the dreamer coming to the city for the first time and seeing the New York Skyline as we approached Manhattan was published in my book, Confessions Of A New York Taxi Driver. I am including it here in my blog for the first time. Go to From JFK or just scroll down. It's right below this post.

And Then There Was This

In November a facsimile of Jerry Seinfeld's op-ed on a gigantic billboard was attached to the facade of a luxury apartment building under construction in the Upper East Side. Unfortunately the Comments Section was not included! Read about it here.

May 23, 2021

From JFK

I had been waiting in the taxi lot at American Airlines for half an hour or so on a pleasant evening in June, 1990, when suddenly the line started moving -- two flights had come in simultaneously and the newly arriving passengers were jumping out of the terminal like popcorn popping. Within five minutes one of them was sitting in the back seat of my cab and we were on our way, fortunately, to Manhattan. (When you pick up a fare at the airport, you're always a little worried that the ride will be a shortie to Brooklyn or Queens. Manhattan is the place you want to go.)

My passenger was a twenty-something kid, an "Agog-er", eyes all aglow at seeing the Big Apple for the very first time. New York, he said, was the place he'd been dreaming of coming to "forever" and finally his dream was coming true. He was from the Midwest somewhere and had studied documentary filmmaking at a couple of different schools, and now at last it was time to take the Big Plunge. His excitement was palpable even though we were still ten miles away from the part of New York that even New Yorkers call "the city"... Manhattan.

You know, I have been saying that one of my favorite kinds of fares is the one with elderly people who are still enjoying living. Let me confide in you now that my very favorite type of ride -- the one at the top of the list -- is this one, the trip to Manhattan with the wide-eyed virgin, so to speak. I become the impromptu tour guide, an embedded guru, offering advice and insider skinny, but secretly longing to experience vicariously the thrill I hope they are about to have when they see it for the very first time.

After twenty minutes of stop and go on the Long Island Expressway we arrived at the last exit you can take before entering the Midtown Tunnel -- I did not want to take that route into the city -- and I got off there. We drove a few more blocks and soon arrived at the exact spot where I needed to be for this particular ride -- the entrance to the Upper Level of the 59th Street Bridge on Thompson Street. I made a right onto the long ramp that rises, before it feeds onto the bridge, above houses, factories and the Number Seven subway line. There are five bridges that span the East River, but the one with not only the best view, but the best feel is the Upper Level of the 59er, and that's why I chose to take him this way. I wanted him to feel it.

Now here's the thing about the Upper Level -- first the broad skyline, that endless vista of skyscrapers -- is one of the great sights of the world. You can see many of New York's iconic structures quite clearly, and that in itself is spectacular, but the main thing, due to its location and its clear sight lines, is the sense you have of the city getting larger and larger and LARGER as you approach it. New York, that faraway dream, is becoming a reality.

Look -- look! -- there it is! It's really there!

And then, as the roadway of the bridge begins to descend toward ground level, the immensity of the place starts to sink in. The buildings gradually surround you -- look, you can see people inside them! -- and one has the sense of being literally devoured by Gotham.

Finally touching down on East 62nd Street, the "energy" of New York City hits you square in the face. People are crowding the sidewalks, walking quickly as if they're late for something, the traffic is bumper to bumper, and, hey, look at that -- there really are yellow taxicabs all over the place. The feeling comes over you that if there actually were a place where your dream will come true, this is what it would look like.

I studied my passenger in the mirror. He was gazing eagerly out his window, trying to take it all in, mesmerized and enchanted, as I hoped he would be.

"So, what do you think?"

"Wow!"

We headed across town on 63rd Street, made a left on 5th Avenue, and started coasting down the avenue which runs straight down the middle of Manhattan.

"Look, " I said, "there's Central Park."

"Oh, yeah, wow!"

"There's Tiffany's."

"Wow!"

"There's Rockefeller Center."

"Wow!"

When we got to the south side of 34th Street, I suddenly pulled over to the curb and stopped.

"Get out," I commanded.

"Get out?"

"Yes, get out and look up."

He did what he was told and found himself gazing at the tallest building he had ever seen. You just can't appreciate the size and magnificence of the Empire State Building unless you're standing right under it.

"Oh my God!" he exclaimed as he climbed back into the cab. He smiled like a little kid at his own birthday party who was about to start opening a whole roomful of presents.

Oh, yes.

He had arrived.

It had begun.

Excerpted from Confessions Of A New York Taxi Driver (HarperCollins)

June 7, 2020

The Rhinoceros Story

A little history...

I grew up in Levittown, New York -- about a forty-five minute drive from Manhattan -- where I was a student in a typical American high school. I graduated in 1967. It's common to look back at that time in your life as the "good old days", but not for me. I couldn't wait to get out of the place! It felt like prison to me. This was the '60s and the tumult of the era was weighing heavily upon me. The prospect of spending another four years in an academic environment, which is where most of the kids I knew were headed, had no appeal whatsoever. I wanted to get far away and "see the world". However, the idea of being drafted into the U.S. Army and being shipped far away into the world of the Viet Nam War also had no appeal. So the thing to do, at least if you were a white, middle-class American boy, was to get yourself into college. That was your ticket to stay out of the military, at least for a few years. It was called a "student deferment". So I needed to find a college that could serve both of these needs.

And find one I did in an offbeat school which had just recently been established not far from my hometown by the Society of Friends (the Quakers). It was called Friends World College. (Actually it was an "institute" when I enrolled in September of '67. It was so new at the time that it was still in the process of becoming accredited by the State of New York. When that occurred, about a year later, it could then officially be called a college.)

The basic idea of Friends World College was to create a learning experience in which students could grow into young adults with a "world view". For four years they would spend successive semesters living in different parts of the planet. This would not be sitting in classrooms, reading books, and taking exams. It would be an integration into the cultures in which they were living.

It was very loosely structured. There were no examinations or formal courses. The only real requirement was the keeping of a journal of one's thoughts and experiences. Seminars and field trips were offered mostly having to do with topics which were progressive in that era, such as ecology, civil rights, consumer cooperatives, regional development, universal suffrage, intentional communities, and socialism. Individual projects were encouraged and advisors were assigned to each student to offer guidance.

My first semester was spent at the North American campus (if you could call it that) on Long Island in a converted barracks leftover from a decommissioned Air Force Base named Mitchel Field. There were 37 kids in my class. We not only participated in student activities, but we shared work responsibilities like cooking and cleaning. So this was not just a school, really, but a community. Here I had finally found a group I could fit in with. Spirited, intelligent, socially conscious to the point of being willing to do something about it, adventurous, iconoclastic: these would all be apt descriptions of the kids there, and of the faculty, too. Plus we all traveled around in the preferred mode of hippie transportation in those days, the Volkswagen bus.

My second semester was spent in Kenya, in East Africa. Now this was "far away" indeed. Not only in distance, but in time. Kenya had only recently obtained independence from Great Britain and in 1968 was barely a nation state. Being there was like traveling back in a time machine to an era when people lived in tribes, subsisted from the land, had very little, if any, contact with the outside world, and needed to be aware at all times of the dangers posed to them by their own predators, the animals.

Our center was in the capital of the country, Nairobi. It had many of the basic things we took for granted back home such as buildings, electricity, running water, paved roads, telephones, a post office, and a hospital. But once you were just a little bit away from Nairobi, wow, were you ever in a different world. Some of the things that remain engraved in my memory are:

-- living among people who never in their lives owned a pair of shoes. Over the years the bottoms of their feet eventually became so calloused that they actually became their "shoes".

-- realizing that in the months I lived in Kenya not only had I never seen a tractor, I had never seen a horse-drawn or ox-drawn plow. What I did see were women bent at right angles tilling the soil by hand.

-- going on a field trip with a few other students which was led by Jesse, a young man employed at the center, who escorted us to the village where he'd grown up. We had to leave our VW bus behind and walk the last mile because there were no roads which led to the village, only trails. At one point along the way Jesse suddenly screamed "Get down!" and we all hit the dirt just as a mass of bees the size of a truck flew right over our heads. Damn! Continuing on, we were greeted effusively by villagers, some of whom bestowed presents upon us. We were only the second group of white people they had ever seen. (Jesse had brought students from the previous class to his village a few months earlier. They were the first.) We were graciously welcomed by Jesse's parents who served us a wonderful meal. The homes in their village were made by building a frame from sticks and filling in the gaps with cow manure. When it dries it hardens like clay and keeps the rain out. Should a big storm come and wash the homes away, the villagers simply build new ones.

-- the school rented a house in the village of Machakos. I stayed there for several weeks.

One day a long line of ants somehow entered the house, marched across the wooden floor, and exited on the other side of the place. The "soldier" ants formed two columns and remained stationary. In the lane they created, the "worker" ants, moving swiftly, carried small bits of food. This went on for about an hour and then quite suddenly they were all gone. Just passing through.

-- one of the few other places in Kenya which at that time could be called a city was Mombasa, on the Indian Ocean, 273 miles from Nairobi. These two cities were connected by what was then the only paved road in the country (other than those within the cities themselves). Once while traveling in a car on this road with one of the faculty members we encountered some elephants standing right in the middle of it, blocking our way. We moved forward quite slowly but got a little too close to them. Suddenly one turned, raised his trunk, and started running toward us in a most unfriendly manner. Not wishing to dispute the point, the car was hastily thrown into reverse and we backed up until the elephant was satisfied we were far enough away from him. Then he went back to his buddies. We sat there for half an hour before they finally went on their way. We'll move when we damned well feel like it.

********

It was on this same road one day that six of us students -- none over the age of nineteen -- were making a journey from Nairobi to Mombasa in one of the VW buses. I don't remember why we were going to Mombasa but I do recall that we were in no rush to get there. It was to be an all-day trip but not an urgent one. We had some time to kill and to explore whatever might come our way. And what came our way was...

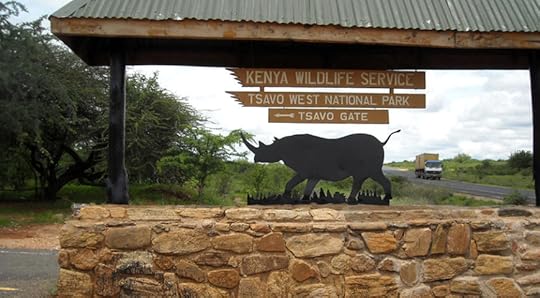

Tsavo.

Tsavo (pronounced SAH-vo) is Kenya's largest National Park. It's an area set aside for animals to live in their natural habitat. No towns, no factories, no taxi garages. Just wide open land. If you're a human, you come with the understanding that you're in Animal Town.

Sometimes when I speak about places like Tsavo to people I feel a need to emphasize the size of these so-called "parks". This is not a theme park, like a Great Adventure or Disney's Animal Kingdom. These national parks are extraordinarily huge. Tsavo's land mass is 8,494 square miles (22,000 in kilometers). That's almost exactly the same size as the entire state of New Jersey in the U.S. and slightly larger than Wales in the U.K.

We'd been rolling along in the bus for a few hours since departing from Nairobi, just looking at the usual sights along the road. The landscape in this part of Africa is primarily flat, open plains, not heavily vegetated as you'd find in a rain forest or a jungle. Your field of view is usually relatively unobstructed, allowing sightings of things like baobab trees and herds of zebras and antelopes.

We came upon a sign telling us we were approaching an entrance to Tsavo National Park.

We stopped and pulled over to the side of the road. A quick tally was taken -- "Hey, wanna check out Tsavo?" -- and the consensus was a unanimous, "Sure, let's do it!"

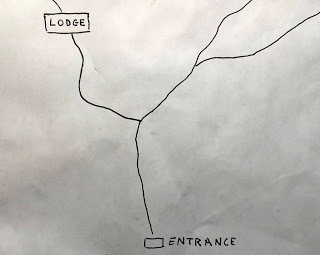

So we approached the entrance where a gatekeeper was sitting in a little hut. After a brief conversation we paid him the entry fee of a few shillings, and he handed us a crude hand-drawn map which looked something like this:

Then he opened the gate and into Tsavo we drove.

The map was pretty much useless as it had no way of calculating the distances between things, no clues as to which animals might be found at any particular location, and no words of caution other than the standard "do not step out of your vehicle". The only thing that looked like it might be of interest (simply because of its name as there was no information about what could be found there) was the "lodge". And so, even though we had no idea how far away it was, we agreed:

"Let's go to the lodge!"

Our excursion began. We'd all been to at least one other park like Tsavo, so we already had an idea of what it would be like inside. The roads are all dirt, of course, and are just about wide enough for two vehicles to pass by in either direction. Sightings of gazelles, zebras, and elephants are common. (The elephants in Tsavo actually appear to be a reddish-brown color due to the volcanic soil they roll around in at a watering holes.) It was also not unusual to see baboons, ostriches, water buffalos, giraffes and, with a little luck, lions.

After we drove about five miles we saw a little cluster of vehicles ahead, just a bit off the road. This is a sign that there is an unusual sighting to be had, so we went over to take a look. Sure enough there was a family of cheetahs hanging out in the grass. None of us had ever seen a cheetah before so this was special.

It's interesting that some of these animals get quite used to vehicles like ours just showing up and parking close to them. One assumes that over time they've simply gotten used to our presence, or at least the presence of these things with four wheels, and don't see them as a threat or a source of food. The cheetahs barely gave us a second look, and we were right next to them.

Well, that was interesting. We drove on -- probably, I would guess, for about another five miles for so, just following the line on the map. Suddenly, wait, stop the bus. A decision had to be made.

According to our little map we would eventually come to a place where two roads converged. If we wanted to get to the lodge we should follow the road to the left. But there was a problem. First, there were no signs on these roads. They didn't have names or numbers, they were just there. Secondly, the road which went to the left was not a wide one like the one we were on. It was merely a narrow, two-tire-track road. Was this the road to take? We couldn't be sure. But, what the hell? It went to the left, so...

...we took it.

It was a little bumpy, but passable. We continued along, not seeing much of anything but birds and trees. No elephants, no zebras, nor any of the usual gang. And then, truly out of nowhere and without anyone even noticing that it was coming right at us -- we were charged by a rhinoceros!

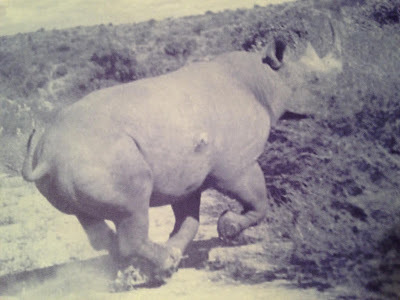

It was running very fast, I'd say at about 30 miles per hour, and it "crossed our bow", so to speak, missing the front of the bus by only a few yards. Then it kept running in a straight line, kind of like a prehistoric cannonball, and disappeared from sight. One of the students, Sally Puleston, an avid photographer, was sitting in the front seat with a camera already perched on her knee and instinctively snapped it, getting this incredible shot:

Photo by Sally Puleston McIntosh

Photo by Sally Puleston McIntoshYes, that's the actual rhino which charged us.

Along with laughter, our reactions were simultaneous yelps of "holy shit", "oh my God!", "whoa, man!" and whatever other expletives were common in 1968. Someone may have even blurted out "groovy!" It was like we'd been watching a movie and suddenly here's the scary part.

For some reason not feeling that the rhino was going to turn around and come after us again, we just continued along on our way -- to the lodge! -- and rather merrily. But after another couple of miles on this two-tire-track-excuse-for-a-road, a new dilemma suddenly presented itself: the road led into a stream and continued out on the other side.

What to do?

We got close enough to the stream to see that a) it was about twenty yards wide, b) it had a sandy bottom, and c) the water was about a foot deep.

Could the bus make it across the stream? Maybe. Maybe not.

What to do?

The decision-making process among six teenagers began.

The kid who'd been driving the bus thought we could make it across. His idea was to back up, pick up speed, and go for it, man! Three of the others agreed. It looked doable to them. Only myself and one other student, Mary Noland, had second thoughts.

Like, wait a minute:

-- our VW bus isn't an all-terrain vehicle, like a Land Rover. It's got small wheels and a tiny engine. It's not made for this kind of thing.

-- we don't know how soft the sandy bottom is. We may not be able to pick up enough traction to get across.

-- the sand may be camouflaging rocks or holes which could not only get the bus stuck but could damage it.

The others disagreed. The basic reasoning was still, "Oh, come on, we can make it!"

Voices began to rise. (My voice, actually.) It went something like this:

-- Hang on, what if we DON'T make it??? We're on a road that's more like a trail than a real road. We haven't seen a single other vehicle since we've been on it. What if we get stuck in the stream and can't get the bus out? Who's gonna help us? What if we sit here for a day or two and nobody comes along? We only have enough food to last for today. Someone's gonna have to WALK back to the main road to get help. Who wants to volunteer to walk back to the main road? And remember, between here and the main road there's a RHINOCEROS which just ATTACKED us! A RHINOCEROS!

I could see that I was swaying them. Just to top it off I added:

-- look, we don't even know if we're on the right road to get to this lodge.

-- who cares about the damned lodge, anyway?

-- even if we make it across the stream now, we're going to have to do it again because we'll be coming back the same way. So it's twice we'll have to make it across the stream.

-- let's just get the hell out of here and hope we don't meet Mister Rhinoceros again.

Finally we all agreed.

We turned around and drove back to the main road. Luckily we did not see the rhino again and we arrived in Mombasa, if I recall, just before sunset.

Plus we got to live.

This incident became one of the milestones in my memory for future reference. Years later it helped me conclude that there are three types of people.

1. People who can learn from observing or reading about the experiences of others. (foresight)

2. People who can't learn from observing or reading about the experiences of others but can learn from their own experiences. (hindsight)

3. People who can't even learn from their own experiences. (no sight)

The "rhinoceros incident" helped me realize something else, too. It's that survival has a lot to do with the ability to simply confront what appears before you, to not be pretending it isn't there. This is not a movie you're in, it's life. My old friends can be excused because we were all still teenagers, but, man, if you don't get that you're in a dangerous situation when you've just come this close to being run down by a rhinoceros, you're just not capable of seeing what's right there in front of you, staring you in the face.

It's also helped me understand that there are people in this world who need danger to feel they are alive. If it isn't dangerous, it isn't fun. You meet people like that every once in a while.

********

Okay, let's fast forward ten years. It's 1978.

Now I am driving a taxi in New York City, an occupation that has recognizing danger as one of the requirements for doing the job for more than a week. (See my post "The Three Strikes and You're Out System" in this blog.)

One day I picked up a young man -- twenty-something, Caucasian, friendly, bright, talkative -- who was en route to JFK. That's about a forty-five minute ride, so it provided time for us to have a real conversation. I learned that he was from somewhere in the Midwest, had never been to New York before, and was impressed with the hustle and bustle of the city. He'd graduated from a college in Ohio, had a couple of jobs since then which he'd found pretty boring, was not married or in a relationship, and was now going out into the world "to make my fortune".

Interesting! It's not every day that somebody tells you he's off to make his fortune.

"Where are you going?"

"To Lebanon."

"Lebanon? Why Lebanon?"

"They're having a civil war. I'm gonna sell arms and ammunition."

"Really! Who are you going to sell them to?"

"I don't know. I'll find out when I get there."

"Uh, have you been to Lebanon before?"

"No."

"So you have contacts over there?"

"Not yet."

Oh my God, this was a guy who saw himself as some kind of character out of a movie: a Robin Hood, James Bond, or Lawrence of Arabia. But I saw him as someone who was about to go to great lengths to get himself killed. Apparently he had no idea what he could be getting himself into. He also had no considerations about the ethics of profiting from the sale of weapons to people who were trying to kill each other. It was all going to be a glorious adventure. And he'll be rich.

I thought I'd take a shot at changing his mind, as unlikely as that was being that here he was, already on his way to the airport. Nevertheless, I pulled the rhinoceros story out of my hat. When the subject of danger comes up in conversation, especially when it involves people who seem to have a blind spot in that area, if there's time and they're up for it, I will tell them the rhinoceros story.

So I said something along the lines of doing what he's planning on doing sounds intriguingly dangerous and I've got a great story about danger for you. It's kind of long, but do you want to hear it?

Of course he did, being that danger was his thing.

So I told him how this group of teenagers riding around in a VW bus in a game park in Kenya (I didn't mention its name) back in '68 had a close encounter with a rhinoceros and how obtuse we were to the danger we were in at the time. Just a rite of passage from adolescence, I said. I was trying to bring the story around to how maybe he should rethink what the danger of being an amateur arms dealer in an unknown country might be, but before I could get to that interrupted me.

"Wow", he said, "that is so interesting that you should tell me this!"

"Why?"

"Just last year the mother of a friend of mine was on a safari in a game park in Kenya. She stepped out of the vehicle they were riding around in to take some pictures and suddenly she was attacked by a rhinoceros. She was killed."

"Oh my God! Really?"

"Yes!"

"Do you know the name of the park she was in?"

"Yeah," he said, "it's called Tsavo."

********

It may have been the same rhinoceros.

January 18, 2020

Why The Medallion Tanked

And yet I have not encountered a single person who actually understood the true reason for the medallion's decline. Nor have I read an article that pinpointed exactly what happened. The assumption is always that Uber showed up and took the passengers away or, according to a recent series of articles in the NY Times, that predatory loans agreed to by unsuspecting drivers were the cause. (To read these articles click here. This is outstanding investigative reporting by Times reporter Brian Rosenthal.)

It is true that these are both parts of the story, but they do not identify the primary cause of the medallion's collapse. What I'm doing in this post is setting the record straight. So, if you're interested, read on.

Some History

You may already know about taxi medallions. If you don't, here is some information about them:

A medallion is a license -- symbolized by a piece of metal (called the "tin" in the industry) -- attached to the hood of a cab. It's a license not to drive, but to own one taxicab.

The owner of a medallion may or may not be the driver of the cab. Most often the driver of a yellow cab in NYC is not the owner. The owner is more likely to be an investor who either leases the medallion to a middleman (known as a "taxi broker", who in turn sets up a driver with the medallion, a taxicab, and insurance) or the owner of the medallion leases it to the operator of a taxi garage. Taxi garages, also known as "fleets", vary in size. Some may have only ten or twenty cabs. Others have hundreds. There are many taxi garages scattered around New York City, mostly in the boroughs outside of Manhattan.

The medallion system was set up in 1937, during the Great Depression. In those days all you had to do to get a permit to be in the taxi business in New York was to have a car and pay a $10 annual fee to the city. The industry was so easy to enter that there were eventually way too many cabs for the amount of business potentially available. No one could make a living with so much competition. So the city said if you don't renew the $10 annual fee you won't be able to get another one because we're not going to issue any new permits (medallions). Before too long the number of taxis dwindled from over 30,000 to exactly 11,787. And it stayed at that number for over 60 years. Since that time the only way you could become an owner of a taxi was to purchase a medallion from someone who already owned one. When the Depression was over demand for taxi service picked up. More people wanted to get into the business. Thus the medallion market was created.

It should be noted, however, that many thousands of car services -- far more than the number of medallion cabs -- were added to the streets of the city as time went on. But only the medallion cabs could legally pick you up by means of the street hail. All other for-hire vehicles had to be summoned by telephone.

2013

Okay, enough history. Here's the story. Why did the medallion drop from $1.3 million to virtually nothing in less than a year?

Let's go back to the year 2013. Conditions in the NYC taxi industry are pretty much the same as they've been for decades. There are approximately 13,000 yellow cabs (one cab for each medallion) on the streets, a number that is set by law and does not increase, as noted, except on the rare occasion when new medallions are auctioned off by the city.

The majority of taxi drivers are working out of taxi garages. Working conditions, as always, are far below the labor standards of most American workplaces.

Drivers must pay leasing fees for twelve-hour shifts -- either a day shift (5 a.m. to 5 p.m.) or a night shift (5 p.m. to 5 a.m.) They also pay for filling the tank up with gas at the end of the shift.

It takes about five hours of driving time to break even, so you don't start making money for yourself until that point is reached. You don't have to work the full twelve hours of a shift -- that's okay -- but you still have to pay the full price of the shift. It's not charged by the hour, or by a percentage of the money from passengers. It's charged by the shift.

There is no union looking out for the drivers, only a taxi advocacy group called the Taxi Workers Alliance. They try their best but they are not a real union because they have no clout -- that is, they have no ability to call for and enforce a strike. No one who has any real power to improve your working conditions -- like the mayor, the Taxi and Limousine Commissioners, or the owner of your garage -- is looking out for you. There is nothing resembling a human resources department in the taxi industry that you'd find in any big business in the United States.

There is no overtime.

There is no health insurance.

There are no sick days.

No paid vacations.

No pension.

No profit sharing (of course).

No bonuses.

Although they pretty much fit the description of "employees", drivers have been deemed "independent contractors" by city law since the early 1980s. (And there went the concept of "benefits".)

Once you're out on the road you are driving in a kind of perpetual horse race with other taxi drivers to be the first to arrive at people waving their arms in the air. It's very competitive. Some cabbies prefer to work the airports and spend a lot of time waiting in front of hotels or in lots at the LaGuardia or JFK airports. Most, though, are battling traffic and other taxis on the streets of Manhattan.

At the same time you're contending with this you are servicing live people in the back seat. It's not like you're moving cargo. You've got people -- virtually every type of person imaginable -- to contend with.

You're carrying cash. Even though about 70% of the payments are made with credit cards, the fact that you are known to have cash could make you the target of a criminal. You cannot legally refuse service to anyone unless they are "disorderly" or intoxicated and you can be fined heavily or even have your license revoked if you're found guilty of doing these and other offenses by one of the TLC's kangaroo courts.

So it's a dangerous and usually a thankless job.

And yet, even with all these liabilities, there are always plenty of drivers. The great majority of them are immigrants from third world countries. Why? Because as substandard as these working conditions are, they're still a lot better than whatever they had in Bangladesh. Or Nigeria. Or Haiti.

Indeed, one problem owners of taxi garages never had was a shortage of drivers. Drivers would tend to come and go, but new ones showing up and old ones returning were always in sufficient supply. Quite often there were more drivers than there were cabs, which gave the owners of taxi fleets a great advantage. If they didn't like a driver for whatever reason, they could simply refuse to lease him a cab. This put drivers in a position of needing to put up with varying degrees of unfairness if they hoped to continue working there.

Dispatchers demanding "tips".

No compensation for lost time if their cab breaks down.

Payment to the garage for accidents which is not returned after insurance compensates the owner.

And so on.

Perhaps the greatest unfairness of all was forcing drivers to accept a "weekly deal". It's better for the owner of a garage to assign one driver to one car and be assured of payment for an entire week than to let drivers work whichever days they preferred. This meant that even if they took a day off to be with their families they were still paying for the shift for that day.

The point I'm making here is that drivers for decades have been utterly taken for granted. I mean "utterly", as in completely, totally, absolutely, entirely, thoroughly, in all respects, and to the hilt.

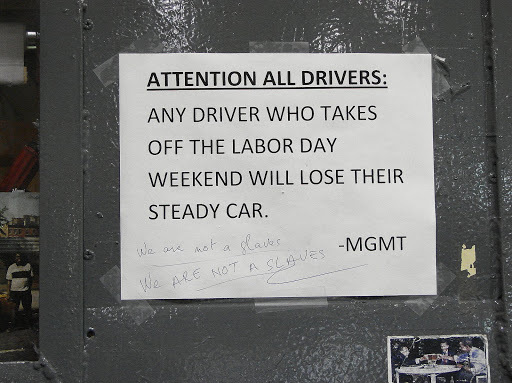

Look at this:

I took this picture in 2009 at my taxi garage. It pretty much tells the story. Labor Day is the one day of the year in the USA that is set aside as a national holiday to honor working people. One driver took it upon himself to write "WE ARE NOT SLAVES" on this insulting notice.

2014 - Uber Arrives

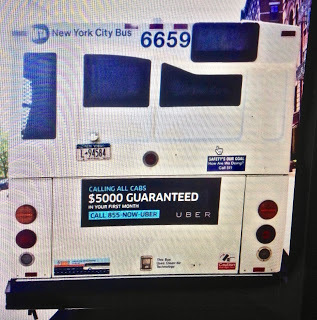

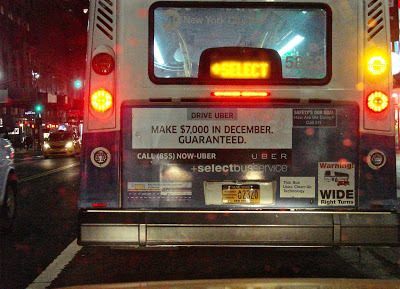

Although according to Wikipedia Uber "went live" in NYC in 2011, it didn't have any impact on the taxi business here until early in 2014. Then, quite suddenly, everywhere you looked -- on billboards, on TV, on the internet, and especially on the backs of buses -- there were ads from Uber directed not at customers, but at drivers. Some of these ads were actually offering guarantees of monthly income, something completely unheard of in the history of the taxi industry.

In 2014 Uber pulled off what I would call a military-precision invasion of New York City. You've got to have several things in place simultaneously for this to be successful.

1. You've got to have a public that has heard of you and has access to you. There was considerable word of mouth about Uber in the United States from people who traveled to places where Uber had already set up shop. And by 2014 everyone had a smart phone, so access, of course, was automatic.

2. You've got to be able to provide your service to the public immediately. If you promote a car service and an app to the general public and then you can't provide a car and a driver, you're finished. That's what happened to Hailo.

3. You've got to have a business model and all sorts of administrators to put it into action. This means people, policies, locations, and equipment. You've got to have the app set up and ready to go without crashing, tech personnel to maintain the app, people to answer phones, people to explain the deal to drivers and get them on the road, managers, lawyers, and staff to run offices.

4. You've got to have a ton of money. By demonstrating its success in other locations before it arrived in New York, Uber was able to obtain venture capital from major investors. By June of 2014 they had secured over a billion dollars in funding.

5. And finally, you've got to have a green light from the city you're about to invade. City officials turned a blind eye as Uber was able to add unlimited numbers of for-hire vehicles to the already congested streets of Manhattan. (By 2018 there were over 100,000.) I think it's safe to assume that the savvy leaders of Uber would not have attempted to enter the world's largest taxi market in the way they did (not with small steps, but with a bang) unless they felt confident that they would not be met with serious opposition from the mayor, the TLC Commissioner, or the City Council.

Meanwhile, At The Taxi Garage

Let's take a look into the world of the taxi garage. Imagine that you operate a taxi garage and you own or lease a hundred medallions. That's one hundred cabs, double-shifted. Two hundred drivers.

If every shift is sold out that means you've got two hundred drivers paying you approximately $125 every day for the use of a cab for twelve hours. That's a lot of money coming in, but you also have an enormous overhead. Your expenses include:

--- the cabs themselves which by TLC rules must be replaced every three years.

-- the parts for the cabs which are in constant need of repair.

-- the cost of the garage. This includes whatever you pay for renting the space if you don't own it, the parking lot for the cabs, the equipment you need to maintain the cabs, office machinery and office supplies.

-- insurance for the cabs, over $500 per month per cab.

-- a body shop and its equipment.

-- perhaps a tow truck.

-- personnel, including mechanics and dispatchers.

-- lawyers.

-- accountants.

-- fees paid to the city.

-- and let's not forget the cost of leasing medallions if you don't own them or paying for loans that may be outstanding on the medallions that you do own.

Clearly, it's an expensive proposition to run a taxi garage in New York City.

The Key Question

About a year after the medallion crashed it occurred to me that I didn't know the answer to a very pertinent question about the economics of the taxi business. I keep up with these things and I was sure I'd never heard the answer to this question in conversation nor had I learned about it from trade magazines or in the media. So I posed it to the owner of my taxi garage, a person who has operated a fleet of as many as 240 cabs for thirty years.

The question was: "What percentage of your cabs have to be out on the road for you to break even?"

He answered immediately without needing a moment to think about it.

"Eighty per cent."

Eighty per cent to break even. That, ladies and germs, is a great piece of data.

Here's another one: the customers of the owner of a taxi garage are NOT the passengers who get into his taxis and pay for a ride. His customers are the drivers who lease his cabs. His income comes almost entirely from his drivers. It is of little concern to the garage owner if passengers are happy with their rides or even if his drivers are out on the streets for the full shift and racking up lots of money on the meter. In fact, it would be fine with him if the drivers don't work the full shift. It would mean less wear and tear on his cabs.

The customers of the owner of a taxi garage are his own drivers. That's where his money comes from.

Why The Medallion Tanked

The medallion did not tank because Uber took the passengers. It certainly took many but not enough so that you couldn't still make a living driving a yellow cab. I can say this for a fact because I've been driving a yellow cab since 1977 until the present. It's true that I'm making less than what I was before Uber showed up in 2014, but it's not that much less. There's still plenty of business for yellow cabs.

And that's because the business model of the medallion cab -- people who live and work in an extremely condensed piece of real estate (Manhattan) step out onto the street, wave a hand in the air, and a yellow car suddenly appears and whisks them away -- is actually competitive with and often better than the app. I see people all the time standing there waiting for their Uber to show up while available yellow cabs are driving right by them. The app may have replaced the telephone but it hasn't replaced the street hail.

The medallion also didn't tank because several hundred drivers were swindled by predatory lenders. There are over 40,000 people in New York City who have valid hack licenses. There were thousands of people who never drove a cab but purchased medallions strictly as investments. The misfortunes of a relative few could, and should, lead to reforms in the way loans are made and even to compensations to these drivers, but it would not by itself destroy the confidence that so many other people still had in the commodity.

The medallion tanked because the drivers defected to Uber.

They suddenly left the garages, in big numbers, and did not come back. New drivers considering entering the industry chose Uber instead of yellow. Old drivers considering returning to the profession decided to give Uber a try instead of taking the old twelve-hour shift deal.

Drivers, who for so many years were taken for granted, whose working conditions were deplorable, saw the possibility of a better life if they left the garages and went with Uber.

No more twelve-hour shifts.

No more working for five hours before you break even.

No more waking at 3 a.m. to get to the taxi garage by 5:00 to start your twelve-hour work day.

No more working all night and not getting to sleep until 7 a.m.

No more dispatchers shaking you down.

No more being turned away because all the cabs are already leased out.

Now you can own and drive your own vehicle.

You can make money even if you drive for just a few hours.

You can arrange your schedule to give you time with your family.

Work when it's busy.

Work whenever you feel like it.

Surge pricing!

Unfortunately, and predictably, this didn't last. As time went forward Uber (and Lyft), like the owners of taxi garages, showed themselves to be not particularly concerned with the welfares of their drivers. In fact Travis Kalanick, Uber's founder, shamelessly announced that the long-term goal of Uber was to completely do away with their drivers and replace them with self-driving cars! These companies allowed their market to become saturated with unlimited numbers of drivers and the good times were over. It was actually very similar to the situation which led to the creation of the medallion in 1937.

But in 2014 Uber sure looked great if you were working out of a taxi garage.

At first the drivers began to drop away like defeated soldiers disappearing from their ranks on the long march home. You might wonder whatever happened to so and so who you used to see at the garage every day. Someone would say out of earshot of the dispatcher that so and so went to Uber. The word started to get around from these early defectors that they were doing so much better now, making as much money in two or three busy hours as they were making in twelve at the garage.

I will never forget what I started seeing in September of 2014. Traditionally summer was always the slowest season for yellow cabs due to so many New Yorkers being out of town on vacation. Many cabbies took time off in the summer, too -- the only time of the year when they may not have had to worry about losing their weekly deal. I might see a dozen empty cabs parked on the street in front of my garage in the summer months, whereas at other times of the year there would be perhaps just two or three out there, waiting for repairs.

But every year right after Labor Day, it would be as if a switch had been turned on. Immediately the business was back, the traffic was worse, the shifts at the garage were selling out, and things were back to normal. This did not happen in 2014. Instead there were dozens of empty cabs sitting on the street because they did not have drivers. In fact, the owner of my garage had a new problem -- he had no place to put his cabs. He had to start paying to keep them in commercial parking lots.

Driving around the city I saw the same thing. Every taxi garage with dozens of empty cabs on the streets. As months went by, nothing changed. Rows and rows of empty cabs at every taxi garage.

The days of endless supplies of drivers were over.

This meant that the garages were below their 80% threshold. They were losing money.

Worse than that, the confidence in the medallion evaporated. There was no reason to believe that things were ever going to get better.

This carried over into the taxi broker segment of the industry as well. As mentioned above, some drivers preferred to lease medallions rather than continue working out of garages. They'd go to a middleman (the broker) who'd set them up with a medallion (owned by an investor), a taxicab, and insurance. He'd then guide them through the red tape of the Taxi and Limousine Commission and they'd be in business for themselves. Part of this arrangement would be for the driver to sign a contract agreeing to continue to lease the medallion for an agreed upon period of time.

Let's say the driver signed a two-year contract to lease the medallion in November of 2012. The two years go by; it's now November of 2014. He sees that all the drivers he knows who went to Uber are doing great, much better than he is. Is he going to renew his contract to lease that medallion?

No. He's going to return it to the broker. See ya later.

Also, getting back to the owners of taxi garages -- they usually own some medallions themselves but they, too, were leasing medallions from investors. Seeing that they no longer had enough drivers and were losing money, did they renew their leases with the medallion owners?

No. In order to cut their expenses they reduced the number of cabs in their fleets by returning the medallions they did not own.

What if you were the person who bought a medallion (or ten) strictly as an investment? That commodity which had been giving you a great return in the form of a monthly check from a broker or a fleet owner has now been returned to you. There are no drivers to be found and you are getting nothing. If you owned only one medallion at least you could still make money by driving the thing yourself. But you can only drive one cab at a time.

You are screwed.

Supposing you were someone who had been considering buying a medallion and was alert enough to understand what was happening. Would you buy a medallion for a million dollars? Would you buy one at any price at all? No, you would not. Nor would anyone else.

If no one will buy a medallion, what is it worth?

Nothing.

So that's why the medallion tanked. The engine that was producing the wealth -- the drivers -- galloped out of the stable in the hope of finding a better life.

It's called karma.

If you kick a horse long enough it will no longer pull your wagon.

December 19, 2019

How Do I Get To Carnegie Hall?

I fed them the line...

"How do I get to Carnegie Hall?"

They were right on it.

"Practice!" they called out in unison.

I paused for a few moments and gave this some serious consideration.

Finally I replied...

"Nah... I think I'll just take Broadway down to 57th Street and make a left."

February 24, 2019

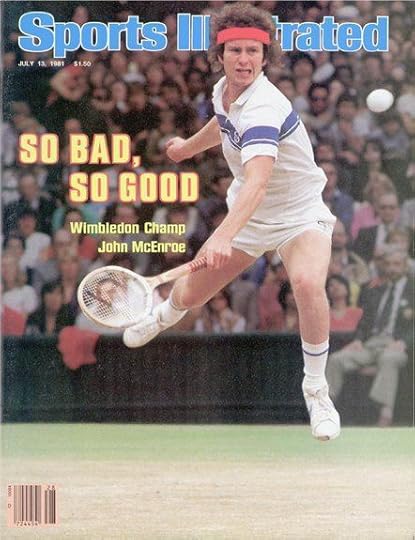

What It Takes, Part 3 -- Epilogue: McEnroe Returns

Epilogue (noun) -- a section or speech at the end of a book or a play that serves as a comment on or a conclusion to what has happened. (the Apple dictionary)

I love epilogues, especially when one occurs in real life, as if life itself were a story. In the context of a ride in a taxi in a big city like New York, epilogues are rare indeed because in most cases you will never meet your passenger again. So whatever you may have found to be interesting, or quirky, or disturbing about your passenger -- whatever the circumstance was -- it will remain unresolved in your mind. You may occasionally find yourself wondering, "whatever became of so-and-so?" You wish you could meet that person again just to find out or so you could satisfactorily end the story yourself.

I had an epilogue in my cab last year on April 22nd, a sunny Sunday with birds chirping and happy trees serenading the city with a concerto in the key of delicate green.

As I was waiting at a red light on Central Park West a bit before 4 p.m., the right rear door opened and a passenger jumped in. Before I could say "hello" he barked, "59th and York and make it fly!" Apparently he was in a big rush.

This kind of request is usually made in the form of a polite question, not a blunt command. I looked in the rearview mirror to evaluate the situation. In other words, why should I drive any faster than I normally do? Is this really an emergency? I had one of those Nissan minivan cabs that day

which has a partition running the entire width of the cab. One of the few things I like about this vehicle is that it allows the driver to fully view the passengers in the rear. It also has an intercom that actually works, enabling the driver and passenger to hear each other. So I was able to take a good look at this guy.

Hey, wait a minute -- he looked familiar.

Oh my God, it was McEnroe. Again. Much older. After thirty-four years he has returned to me, the prodigal passenger.

"Mister McEnroe!" I exclaimed.

Big mistake.

If you recall from the second story in this series, the correct way to address John McEnroe is by referring to him by his last name only. I should have remembered this and I immediately suffered the consequences of my blunder.

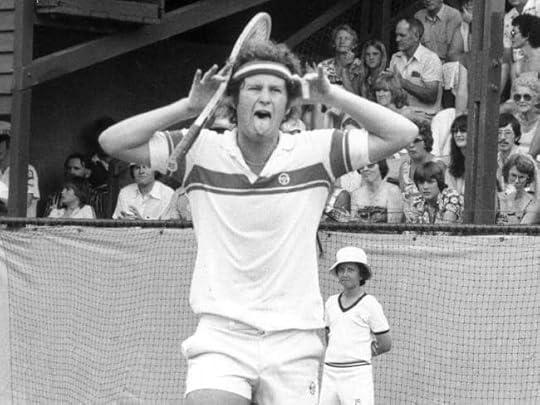

"WE DON'T HAVE TO TALK!" he screamed.

Now if this had been virtually anyone else in the world I would have tossed the guy out of my cab. It's a dignity issue. You can't allow people to talk to you that way unless, of course, they are drunk and much bigger than you. But this was McEnroe. Actually, it was kind of charming. I smiled as if he'd said, "Hello there, how are you?", which in his own way is sort of what he did.

I stepped lightly on the gas and we began moving downtown on Central Park West. His destination required me to make an almost immediate left turn onto the transverse which runs through the park at 65th Street. It's the fastest route to the East Side. But the transverse was closed due to a parade on 5th Avenue that day, so we had to cut over to Broadway, a detour. McEnroe didn't take this lying down and began venting his rage at Mayor de Blasio, the tyrant who had no doubt orchestrated this outrage. Ridiculous to get so upset, you say, but think about it. This is McEnroe. Everyone knows how McEnroe feels about referees and mayors are pretty much the same as referees. Right?

I realized there was no point in continuing on in that vein. Instead, I said:

"Hey, do you remember what you were doing in the evening of March 13th, 1984?"

This non sequitur caught his attention. He perked up and forgot about the mayor.

"I have no idea."

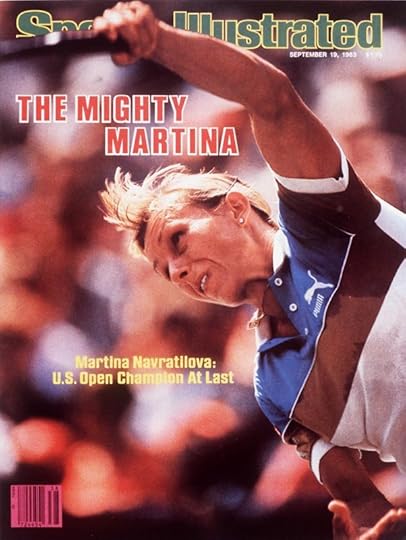

"You were in my cab. I picked you up from your place on East End Avenue and took you to the Garden to a Knicks game. We talked about sports. I told you about the time I hit some balls with Martina Navratilova's coach."

McEnroe's face lit up. "I think I remember that ride!"

Well, that handled his don't-talk-to-me and his I'm-in-a-big-rush state of mind. Suddenly McEnroe was friendly, conversational, and in no particular hurry. We began a rambling conversation about various subjects, one thing leading to another, as often happens in a lively exchange. My long tenure as a taxi driver interested him and he asked me some questions about my more memorable rides. One that I mentioned was the ride with a couple of Mafia hit men to Newark Airport. That led to him telling me about a book he'd been reading at the time, I Hear You Paint Houses, which led to how much money Netflix was reportedly paying Martin Scorsese to direct the movie version. And so on.

By the time we were about halfway to 59th and York I suddenly realized that I had the rarest of rare opportunities at hand. And that this was really going to be fun.

Let me explain: in the last 34 years I have told the stories in Parts 1 and 2 of this series to countless passengers in my cab. If the subject of tennis comes up, or if anything to do with what it takes to be the champion in a sport comes up, if time permits I will tell my passengers those two stories together. First the story about how pleased I was with myself that I was able to hit the serve of Mike Estep, Martina Navratilova's coach. Then the story about what McEnroe's response to me was, seven months later, when I told him how pleased I was with myself that I could hit Mike Estep's serve:

"Well, Mike's never been known for his serve," McEnroe had said.

It burst my little bubble.

This always gets a laugh. Then to make my point I really dig into McEnroe, putting emphasis on certain words. I'll say: "here's a guy who is number ONE... in the WORLD! NO ONE can beat him! In the WORLD! NO ONE! But he's just a little concerned that maybe his TAXI DRIVER can hit his serve. But then, oh, wait, it's okay. It was only Mike Estep. I'm safe."

After a brief pause for more laughter I'll put the finishing touches on my speech:

"What we're looking at here is compulsive competitiveness of a magnitude that is borderline insane! This guy is asylum bait. He's surrounded by assassins. Even his taxi driver, for God's sake, is a potential threat to his dominance in the world of tennis."

And the point I make is that this is what it takes to be Number One.

So -- the rarest of rare opportunities at hand was this: due to the high level of affinity that had been created between us by our free-flowing conversation, I knew I could now tell McEnroe the story I'd been telling passengers for 34 years about him to him. Just the way I tell it. In life this just never happens.

So I set him up.

As we hit some traffic on 57th Street, I asked him if he remembered what he'd said to me in 1984 about my tennis session with Martina's coach. Of course he did not, so the door was open. I started at the beginning with Mike Estep hailing me on 6th Avenue in August of 1983, how friendly he was, how he was telling me things about the men's tour he probably shouldn't be telling anyone, about how he always beats Martina in a real match, and so on, leading up to his invitation to come out onto the court so I could see what it's like to try to hit the serve of a pro, and then later observing the ferocity of Martina when she played him in a practice game for real.

Watching McEnroe in the mirror, it was clear that he was enjoying the story and I was in safe territory when the story became about him. So I brought it on...

"...so it's seven months later, March 13th, 1984 to be exact..."

"...you're going to the Garden, you're in my cab, we're on the FDR Drive..."

"...I'm telling you how happy I was with myself that I was able to hit his serve..."

"...you move forward in your seat, a look of concern on your face..."

"...what was his name again? you ask..."

"...Mike Estep..."

"...you move back in your seat, all relieved..."

"...well, you know," you say, "Mike's never been known for his serve"...

I check in the mirror to see how McEnroe's responding. He's loving it. I continue, with emphasis:

"...it's 1984. You're the Number ONE tennis player in the WORLD! NO ONE can beat you! In the WORLD! NO ONE! But you're just a little concerned that maybe your TAXI DRIVER can hit your serve! But then, wait, it's okay, it's only Mike Estep. I'm safe."

Looking again at McEnroe, I see he's just about doubled-over in laughter. I move in for the kill. In mock exasperation, squealing:

"Mike's never been known for his serve?"And then, the coup de grace, both middle fingers raised high in extended triumph:

"FUCK YOU! FU-U-U-CK YO-U-U-U McENROE!"

Now he is doubled-over in laughter.

I tell my passenger to go fuck himself and he loves it. A great accomplishment for me, but I knew it wouldn't offend him. Self-deprecation has always been one of McEnroe's sterling qualities -- his saving grace, actually.

A feeling of calm set in as the laughter subsided. We rode in silence for half a minute or so, then traffic for the 59th Street Bridge brought us to a complete stop at Park Avenue. I told McEnroe I knew a cab driver trick to get around it and proceeded to turn one block south to 56th Street, which is always completely empty. As we began to zip along at a decent pace, I remembered that in our previous ride back in '84 I had kind of set him up for giving me a big tip. We now had only a couple of minutes before we'd arrive at his destination, but I realized it could be done again.

"You know, for many years you held the record for being the best celebrity tipper in my cab," I said.

"Really! Who broke it?"

"Leonardo di Caprio. Back in 1997. He wanted to know who was the best celebrity tipper I'd ever had in my cab and I said, 'believe it or not it was John McEnroe, who gave me double the meter.' Then he said, 'well I'm gonna give you triple the meter.' And he did. Pretty impressive, considering he was really just a kid at the time."

Looking at him in the mirror, I could see a certain look of concern appearing on his face which I'd seen before. Remember, this is one of the most competitive human beings in the world.

I continued:

"That record stood for 17 years until it was broken by Derek Jeter who gave me quadruple the meter."

McEnroe was indeed concerned. "What was Jeter like?" he asked. "I've never met him."

I told him Jeter was as advertised -- friendly, funny, easy to talk to, unpretentious.

After just a bit more conversation we pulled up at his destination, the Sutton East Tennis Club (of course!) at 59th and York. The fare was $19.30. I could almost see the wheels turning in his mind -- "should I give this guy quintuple the meter?" That would be almost $100. Could he do it? The title of Best Celebrity Tipper Of All Time was within his grasp -- again! -- and the tension was almost palpable.

McEnroe, like most people these days, was paying with a credit card. As the passenger is touching a screen in the back to enter the tip, the driver can watch on his own screen in the front to see what's happening. McEnroe began tapping. If this had been taking place in a stadium, the crowd would be hushed in nail-biting anticipation.

Could he do it?

The numbers began coming up on my screen, ever so slowly, one digit at a time... a five, then a zero, then a period and two more zeroes. Fifty dollars. A valiant effort, ladies and gentlemen, but, alas, not enough. He had come up short. So sad, really, to see Father Time catching up with them. Even the great ones must fall eventually to his relentless pursuit.

But wait!

Number of times what's on the meter is only one way of determining the winner. Simple quantity would be another, more accurate, means of awarding the trophy. Di Caprio's ride in 1997 had been a short one and double the meter came to about ten dollars. And Jeter's ride was also a short one, around $8 on the meter and he gave me two twenties. A $32 tip.

So actually McEnroe had done it! After 34 years he had come back to reclaim his title -- the Best Celebrity Tipper of All Time In My Cab.

Without question the greatest comeback in taxi history!

I immediately decided he should receive a trophy -- my book. I always keep a copy handy on the dashboard should the need arise to show it to passengers and this was just such an occasion.

Thanking him for his tip, I announced that I had something for him -- "because you're special!" And I held it up for him to see. I couldn't hand it to him because the partition in these Nissans is solid with no window, so I told him to come around to me to receive his prize. While he was on his way I wrote an inscription: "To John McEnroe, Thanks for that double the meter in 1984! Best wishes, Eugene Salomon." I handed him the book, we shook hands, and by the smile on his face it seemed to me that he was as happy to receive it as he was when he'd been handed one of his many trophies for winning the U.S. Open.

Although that could be something of an overstatement on my part.

*********

I found myself basking in the afterglow of that ride as my day continued on. While taking a break at one of the many Starbucks around the city I reviewed mentally what had transpired earlier. By confronting and skillfully communicating with an angry passenger I had turned the ride into a pleasant experience for the both of us. I had transformed "we don't have to talk" into a fifty dollar tip. I had explained to the passenger the route I was taking and expertly navigated the city streets to get him there in the shortest possible time. I was so able to get myself on his wavelength to the point that even saying "fuck you" to him was completely appropriate and appreciated. And I had given him a book written by his own taxi driver, something that is not likely to happen to a passenger even once in a lifetime. Putting all modesty aside, that is what it takes to rise to the very top echelon of a subset of our culture called "taxi driver".

[image error]

October 4, 2018

What It Takes, Part 2 -- My (Verbal) Tennis Match With John McEnroe

It was the doorman of his high-rise on East End Avenue who'd hailed me and opened the door for him but since I'd been looking down at my trip sheet, filling in the required information, I hadn't yet noticed who my new passenger was. I simply called out my usual "hello" and awaited the response. Would this one be friendly, in a big rush, arrogant, a drunk, a serial killer, or what? McEnroe's response was a hard, direct shot, you might say, to my forehand.

"The Garden," he said.

Now, what was most important here was what wasn't said. He didn't say "hello" back to me. He didn't say "please". He didn't say "Madison Square". Just "the Garden", as if I automatically knew who he was and which garden he was talking about. It was more of an order than a request and at the same time it tested the ability of the recipient (me) to respond in kind. An excellent opening -- I didn't yet know who he was, but he'd already scored. Point, McEnroe.

I looked straight into the rearview mirror, wondering who would be speaking to me this way. I recognized him immediately and shot back my own gut response:

"McEnroe," I blurted out, showing surprise but no great enthusiasm.

I give myself a point here because: a) I returned his sharp opening with one of my own. If he had intended to be blunt with no mincing of words, he got the same from me. b) I didn't show any false respect or false adulation or false friendliness. It was just "McEnroe", not "Mr. McEnroe", or "Oh, John McEnroe!" Basically I was conveying an attitude that said, Okay, I know who you are, but you're not on a tennis court, buddy, you're sitting in my cab, so don't start up with any of those shenanigans you're famous for. I can hit your serve. Point, Salomon.

His return caught me off guard. "Yes, it's me ," he said, more to himself than to me and barely loud enough to be heard.

Now this was a switch, a complete change of style. His words could be interpreted as "Yes, the Great One is in your presence," but his tone was self-deprecating. Here was John McEnroe in person poking fun at John McEnroe the celebrity, actually satirizing himself. It was an impressive display of flexibility as a conversationalist. Point, McEnroe.

We volleyed as we headed south on East End Avenue.

"Are you playing tonight?" I asked, thinking maybe there was a tennis match at the Garden. No, he said, he was going to a Knicks game.

"Take the Drive?" I asked. (Meaning the FDR Drive, the highway that runs along the east side of Manhattan.)

"Yeah, please."

"Who are the Knicks playing tonight?"

"The Suns."

A couple more easy lobs were exchanged with no points scored.

Then, fearing the conversation might peter out for lack of fuel, I changed the tempo by employing a technique I've used on other celebrities. I express my regrets that I'm not all that familiar with their area of expertise (even if I am) because here would be a great opportunity for me to learn something from someone so renown in that field. Celebrities live lives of annoyance from mundane questions posed by strangers and this may cause them to be reluctant to engage. So by pleading ignorance (or even pretending you don't recognize them) it has the effect of putting them at ease.

"Too bad I don't really know that much about tennis," I kind-of-lied as I made a left on 79th Street and approached the entrance to the Drive, "or I might be able to hold down an intelligent conversation here. I mean, I play a little, but I don't really know the fine points of the game."

Looking in the mirror, I watched his facial expression loosen up just a notch. I edged into the opening I had created. "Funny," I said, "I seem to keep getting professional tennis players in my cab."

McEnroe was interested. "Really? Who?"

I could feel a big score coming up. Here was the famous John McEnroe showing an interest in the not-famous me. To hell with modesty, a surge of what let's call self-importance was rising from within and it felt good.

I told him about a couple of fares I'd had with tennis players whose names I didn't remember. After talking for half a minute, however, I realized I was getting too chatty and that McEnroe's interest was waning. So I served him up my big story ("What It Takes, Part 1") about how the previous summer I'd driven Mike Estep, Martina Navratilova's coach, out to a private club in Queens to practice with her; how Mike was such a great guy; how he'd asked me if I'd like to watch them practice; how I'd always wondered if I could return the serve of a pro, so I asked Mike if he'd hit me a few balls when we got there; and how -- isn't this great? -- he did.

McEnroe was all ears. Not to brag but, really, I had the guy in the palm of my hand.

"Could you hit it?" he asked.

John McEnroe, the number one tennis player in the world, wants to know about my tennis game. Yes! Point, Salomon!

"Yeah," I said and, not trying to disguise my pride, I told him how I'd actually been able to get my racquet -- actually, Martina's racquet, ha-ha -- on the ball. Not with any authority, mind you, but still, after a few serves I was getting my timing down and I could hit it. Not bad for an amateur, huh?

McEnroe moved forward, a concerned look on his face.

"Who was that again?"

"Mike Estep," said I.

"Oh," he said, and he moved comfortably back in his seat again. "Well, you know, Mike's never been known for his serve."

Ping!

The little bubble I'd been sitting in for the last seven months came bursting apart and evaporated into the atmosphere.

"Mike's never been known for his serve."

With one quick stroke I'd been reduced to the pathetic little tennis wannabe I actually was.

Point, set, match -- McEnroe. Damn!