Jeremy Butterfield's Blog

November 30, 2025

Exploring Advent: Origins and Traditions

‘The Lord Will Come and not be Slow‘

(John Milton)

Ah, Advent! The season when children’s faces and some adults’ faces, too – mine, anyway – light up while, day by day, they open whatever kind of Advent calendar has come their way.

I vividly remember, aged four, my first, sparkly one, so any calendar today is a fast track down nostalgia lane.

Advent in Church terms begins on the Sunday nearest 30 November – this year, on 30 November itself – and covers the period from then until Christmas Eve. In popular use, it starts on 1 December. It refers to Jesus’s forthcoming arrival into the world and also to his eventual return one day in the Second Coming. (I say a bit about the word’s origins at the end.)

In a largely post-Christian Britain, it’s a safe bet that lots of people will experience greater excitement over Advent calendars than over the event Advent leads up to. In fact, some Advent calendars long ago morphed from winter scenes revealed by opening tiny doors, or even from the simple serotonin- and dopamine-induced high of chocolates concealed behind such doors.

Brands and retailers long ago adventjacked the calendars and turned them into an excuse for conspicuous consumption to the tune of several hundred or even several thousand pounds.

Sandro Botticelli The Adoration of the Kings about 1470-5 Tempera on poplar, 130.8 x 130.8 cm Bought, 1878 NG1033 https://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/paintings/NG1033 Licensed for non-commercial use under a Creative Commons AgreementWhere did Advent calendars start?

Sandro Botticelli The Adoration of the Kings about 1470-5 Tempera on poplar, 130.8 x 130.8 cm Bought, 1878 NG1033 https://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/paintings/NG1033 Licensed for non-commercial use under a Creative Commons AgreementWhere did Advent calendars start?If this were a film about the history of Advent calendars, we would now hear the voiceover saying, ‘But it wasn’t always like that…’ and then be presented with a snow-infused shot of a Victorian family whose adorably fresh-faced and well-behaved children are gleefully opening one of the minuscule* doors to reveal a nativity scene, or angels, or reindeer, and so forth.

Then the viewer hears an ear-shattering #$@!%%!?ф¡¡16йщ3¿¿ (denoting a classic film sound effect that this scene is completely wrong).

The most likely origin of Advent calendars is touchingly domestic and certainly not British. Accounts vary, but according to one tradition the first was made by a mother in Munich for her little son to stop him asking over and over again when Christmas would come. She stuck twenty-four tiny sweets to a sheet of cardboard for her boy to eat one day at a time. According to another version, the first printed Advent calendars were produced in 1851 in Germany, but a late nineteenth-century date or even an early twentieth-century one also seems possible.

What is certainly true is that the earlier calendars featured images which children would cut out and affix to the background of the calendar. And those images were generally religious in nature, such as scenes of the Nativity. It was only in the 1920s that doorlets that could be prised open were introduced. Some calendars have twenty-four doors, some twenty-five, to include Christmas Day.

This links to a rather novel Advent calendar: a haiku per day, going through the twenty-four books of the Hebrew Bible (all of which are in the Protestant Bible).

While lavish calendars stuffed with goods may be a thing, booksellers and other outlets still stock plenty of the simpler kind. In our home, we alternate between using a calendar with doors, each revealing a bird or animal in a nostalgic winter scene, and one with an imposing Nordic stable for the reindeer where you insert them, their harnesses and accoutrements into little slots so they sit upright.

Bringing light in the darkness of winterThe origins of the Advent wreath are also German. A certain Johann Hinrich Wichern was a philanthropist who took in street children into homes he established in Hamburg. In the run-up to Christmas, he would tell them the Christmas story and every day add an extra candle to the circular holders hanging from the ceiling. Doing this was a sort of visual religious parable, answering to Jesus’s saying ‘I am the light of the world: he that followeth me shall not walk in darkness, but shall have the light of life.’ (John 8:12)

And in the north of the northern hemisphere, where December days are at their shortest, light has a powerful, poetic resonance. For instance, in Sweden on 13 December people celebrate the Feast of Sankta Lucia, Saint Lucy, a big part of their Advent tradition. Saint Lucy was a fourth-century martyr, and on her feast day she becomes the bringer of light in the depths of winter. In fact, her very name is based on the Latin for ‘light’, lux. In Swedish churches on 13 December, one woman representing Saint Lucy leads a group of other women, all robed in baptismal white and carrying candles, while she is crowned with a wreath of lighted candles. York Minster nowadays regularly celebrates Sankta Lucia, which seems very appropriate given the city’s Nordic heritage.

And why does Saint Lucy’s day fall on 13 December? Because that was the shortest day in the Julian Calendar.

Similarly, on the theme of light, in UK churches, one candle will be lit every Sunday of the four before Christmas. In other words, religious Advent, unlike Advent calendars, doesn’t start on 1 December. The Church of England collect (the word is pronounced stressing the first syllable and means a short prayer said by the officiant before the bible reading) for Advent Sunday opens with this powerful metaphor of light:

Almighty God,

give us grace that we may cast away the works of darkness, and put upon us the armour of light, now in the time of this mortal life, in which thy Son Jesus Christ came to visit us in great humility.

And light is the central feature of the Jewish menorah. The version with seven candles refers to the style of lamp used in the Temple. The version with nine candles used during Hanukkah is a hanukiah. Eight candles of this version with nine candles signify how many days the oil burned, by miracle, in the Temple after it was recaptured by the Macabees in 164 BC, while the ninth is a “helper” candle or shammash to light the others with. Hanukkah, which this year begins on the evening of 14 December, celebrates the rededication of the Temple.

***

This Advent, leading up to Christmas, should always be written with a capital A, being a proper noun. The common noun* advent, with a lower-case a, means the arrival of something or someone.

(* “common” in grammatical terms, in contrast to proper nouns. It isn’t very common, of course – not the sort of word you’d hear down the pub.)

Both versions come from the Latin adventus, which was used in Classical Latin and in the Vulgate, the fourth-century version of the Bible produced by the scholarly Saint Jerome, who is often portrayed in mediaeval and Renaissance paintings at work in his study. And adventus in turn derives from advenīre, from ad, meaning ‘to’ venire, ‘to come’. The religious use of the term in Latin is a translation of the Greek parousia (παρουσία) referring to Jesus’s second coming.

As for when the tradition of marking the lead-up to Christmas started, it was certainly in force by AD 480 and thus dates back to an early phase of the development of the Church in Europe. However, monks were enjoined to fast rather than, as we tend to, feast.

I won’t be fasting. There are too many good things to eat. Ought I to be ashamed to say that I’ll be eating panettone, a hangover from when I lived in Italy; lebkuchen, to remember my beloved German stepmother? And they will contain plenty of marzipan, cinnamon and nutmeg. And the mincemeat in mince pies goes without saying.

Whether you’re fasting or feasting, I’d like to wish you a joyous Advent.

* I almost forgot. The original spelling is minUscule, via French from Latin, but pronunciation of that middle u as an i and also the link to mini and its compounds have conspired to produce the spelling miniscule with a central i, which Collins accepts as an alternative form. But bear in mind some people don’t.

This post is a lovingly tweaked version of one originally posted on the Collins Dictionary Langaguage Lovers site in 2022.

November 5, 2025

The Fascinating World of Oodle Words – Part II

Last week I looked at verbs containing the *oodle* string and suggested there was some sound symbolism going on. I didn’t mention three verbs linked by the idea of snuggling or being close, to croodle (1788), canoodle (1864) and snoodle (1887), the first and last being dialectal.

Crowdle.., to creep close together, as children round the fire, or chickens under the hen.

But this week we’re concentrating on the nouns, and what a cornucopia (1611) we have.

The OED lets you sort your choices by frequency, by date or by alphabetical order. If you choose frequency, guess which noun comes top? (I’ll let you in on that at the end.)

But sorting by date is more up my Strasse at the moment, as I love finding out how old – or new – a word is.

The oldest *oodle* in the OED is a 1542 noun based on a sound, only cited twice there and both times in works by Nicholas Udall, headmaster of Eton and Westminster (not concurrently, silly!), convicted sodomite and author of the comedy Ralph Roister Doister, in his translation of Erasmus’ Apophthegms.

His instrumente wheron to plaie toodle loodle bagpipe.

That’s followed by another musical – or quite possibly, unmusical – sound sometime before 1566 in the reduplicative shape of toodle-toodle, defined as ‘an imitation of the sound of a pipe or flute.’ Thankfully obsolete, says the OED.

But then we come onto a sound that’s alive and kicking and might even wake you up if you live in the country, as noted in Gabriel Harvey’s letter-book in 1573:

The yung cockerels… followid after with a cockaloodletoo as wel as ther strenhth wuld suffer them.

Nowadays we generally transcribe it as cock-a-doodle-doo. Which could lead onto how other languages transcribe the ‘same’ sound, e.g. French cocorico, Russian кукарекý (kukareku) or German kikeriki. Further than that we won’t go here. I rather like the spelling strenhth.

Sadly, the OED declares obsolete the restorative cock-a-doodle-do broth (1856), ‘a restorative drink consisting of beaten eggs mixed with either brandy or sherry’, to which one recipe adds milk and sugar. Perhaps better that way; otherwise it sounds like raw zabaglione.

In several nouns the dominant idea is foolishness. Earliest is the 1664 compound fopdoodle, adding the 1629 doodle to fop and first cited in Samuel Butler’s Hudibras but now obsolete.

Sometime around 1670 gives us fadoodle, ‘something foolish or ridiculous; nonsense’ which the OED double-whammies as ‘obsolete’ and ‘rare’. Its formation is ‘arbitrary’, i.e. it’s completely made up out of thin air but with that significant sememe oodle (which Grammarly wants to correct to *sememeoodle, which won’t do at all!).

Still in the 17C we’re regaled in rhyme, no less, with Tom doodle, ‘a clown, a fool; a stupid or foolish person, an oaf’

The first that appeard was a great Tom-a-doodle | With a Cap like Bushel, to cover his Noddle.

E. Ward, O Raree Show

before we reach the 1720 noodle, which, sadly, does not relate to the food noodle and therefore doesn’t allow me to apply the conceptual metaphor ‘stupid people are a foodstuff’ ‘as in e.g. dough ball or gammon. The OED suggests the origin is noddle, as in the quote above, meaning ‘the back of the head; the nape of the neck’.

Image courtesy of Charles Deluvio on Unsplash.

Image courtesy of Charles Deluvio on Unsplash. The incomestible – well, I just made that up, though it’s in Spanish, too – noodle, then, has had varied offspring, hopefully self-explanatory: noodledom (1810), noodledum (1821; a foolish person. I love this one!), noodleism (1829), noodlehead (1835) and – surprisingly modern – noodleness (1931).

My favourite ‘foolish’ word containing *oodle* must be flapdoodle:

‘The gentleman has eaten no small quantity of flapdoodle in his lifetime.’ ‘What’s that, O’Brien?’ replied I… ‘Why, Peter,’ rejoined he, ‘it’s the stuff they feed fools on.’

F. Marryat, Peter Simple, 1834

I couldn’t finish this piece without mentioning:

caboodle – before 1848, possibly a clipping of the phrase kit and boodle, boodle (1625) being borrowed from Dutch boedel, ‘property’;

Yankee doodle – 1786, ‘the title of a popular air of the United States of America, considered to be characteristically national’ and then for ‘yankee’ in 1787.

And what about jolly old oodle as in oodles of something? It’s yet another gift from US English to World English and is of mid-19C vintage, well, sometime before 1867, apparently. The OED suggests it might be a shortening of the slang scadoodles, with the same meaning, or the boodle already mentioned.

With that, it just remains for me to say, as some kind readers have suggested, cheerio, toodle-oo (1907) and toodle-pip (1977) as I pootle off (1973) to potter about (1824 in that meaning) in the meadows of English vocabulary.

Image courtesy of Fredrik Öhlander on Unsplash.

Image courtesy of Fredrik Öhlander on Unsplash.** The top *oodle* by frequency is, natch, the poodle.

October 29, 2025

The fascinating world of ‘oodle’ words

Have you ever wondered about words containing the sequence of letters –oodle-?

I mean, does it signify anything, or is it random?

No?

But don’t worry: I’ve done the wondering for you. Because I want to know if that sequence connotes something, in the way that, say, as Professor Anatoly Liberman suggests, many words beginning with fl– ‘ fly, flow, flatter, flutter, and flicker suggest unsteady movement.’ In other words, is there sound symbolism going on here?

If you search for that –oodle- string in the OED you get a surprising 130. But as so often happens with such trawls, you haul into your nets words that aren’t relevant to your search, such as bloodless or bloodletting.

Even so, throwing them back in the water still leaves me with a very large metaphorical catch.

We can jettison a couple right from the start on the basis of their origins, in German: noodle and poodle, from Nudel and Pudel(hund), though it’s interesting that Pudel derives from the German verb puddeln, ‘to splash about in water’, so the OED tells me.

Also to be jettisoned are the three poodle crosses we now foist on our furry chums as if they were a fashion accessory: goldendoodle, labradoodle and schnoodle, for golden retriever, labrador and schnauzer with poodle crosses.

But hold your horses! What about the verb to poodle, and what about the five verb homonyms of noodle?

To poodle, as classic as case of verbing as any you can think of, is defined as ‘to move or travel in a leisurely, indirect, or aimless manner; to potter. Usually with about, along’ and dates back not far short of a century to 1938.

The OED compares it to the mostly British to pootle (1973), ‘to move or travel in a leisurely manner’, which is a pronunciation variant of to poodle, devoicing the d. Which brings to mind also to tootle (1902), ‘to walk, to wander casually or aimlessly’. So perhaps the sequence –ootle– is relevant too (to footle: intransitive. To act or talk foolishly; to occupy oneself in an aimless or trivial way. Also with about, around.)

What links those four verbs, poodle, pootle, tootle and footle, it seems to me, is that the action they describe is performed with very little drive and with no clear purpose.

Are we on to something here?

So the next step is to list the –oodle– verbs. Well, not all of them. That would be tedious and tax your patience, gentle readers.

He flapdoodled round the subject in the usual Archiepiscopal way.

Westminster Gazette 11 July 2/1, 1893

Of the twenty-two verbs, the following five are relevant, as their definitions suggest – and we’ve already discussed to poodle. Most of them are colloquial and regional, whether that ‘region’ be the US, Britain and Ireland, or Australia. In short, don’t be surprised if they’re as new to you as they are to me. Dates are for the meaning, not the word, as several have more than one meaning; and some are examples of ‘conversion’, aka verbing.

to soodle – (1821; dialect) to walk in a slow or leisurely manner; to stroll, saunter.

to noodle – (1854; English regional) to fool around, to waste time.

to moodle – (1893) to dawdle aimlessly; to idle time away. Also with about, on. (possibly invented by George Bernard Shaw).

to flap-doodle – (1893) to talk nonsense; to maunder.

to doodle – (1937) to draw or scrawl aimlessly; to idle.

Courtesy of Alison Pang on Unsplash

Courtesy of Alison Pang on UnsplashNapoleon often moodled about for a week at a time doing nothing but play with his children.

G. B. Shaw, Intelligent Woman’s Guide to Socialism lxix. 328, 1928

So far, so good. But what about the other sixteen?

Well, these next five all have to do with sounds, and what they have in common is to denote sounds which are either subdued and low or inconsequential:

to croodle – (before 1810; Scottish) to make a continued soft low murmuring sound; esp. to coo as a dove.

to doodle – (1815; Scottish) to play the bagpipes.

to toodle – (1865; ?dialect) to hum or sing in a low tone (as to a baby).

to noodle2 – (1897; Scottish (Shetland) to sing (a tune) in a low undertone; to hum.

to noodle5 – (1937; chiefly Jazz) to play or sing (a piece of music) in a tentative, playful, or improvisatory way.

The cushat croodles amourously.

R. Tannahill, ‘Bonnie Wood’ in Poems (1846) 132, composed before 1810.

(cushat = wood pigeon, Scots, from Old English)

The odd sound out here seems to be to kyoodle (1935; U.S. dialect and colloquial) to make a loud noise; to bark, to yap. I haven’t yet deal with the whole kit and caboodle of these sounds. In a classic cliffhanger , that will have to wait till next week

, that will have to wait till next week

October 22, 2025

The Etymology of ‘A Gogo’: From French Roots to Pop Culture

It’s a long time since I’ve posted anything, and today I realised with a jolt that I’m in danger of turning my site into what is sometimes called a ‘cobweb site’, in that gruesome pun I remember from back in the day when I was a gros fromage at Collins Dictionaries.

I decided it really was time to get off my metaphorical, ahem, hindquarters.

But what to write about?

Well, anything that comes into my head, really, is as good a starting point as any. And what usually comes into my head is something to do with words.

And the words today are the phrase a gogo in the sense of ‘galore, in abundance’. It comes after any noun, so it’s ‘postpositive’, to use the off-putting grammarian’s term, e.g. Funny characters, great visuals, Robin Williams back on form, cameos agogo

(It came to mind because I was thinking of other reduplicated phrases such as hippy-dippy and happy-clappy, which will give me substantial fodder for another day.)

So is a gogo an example of reduplication?

Well, yes and no: ‘yes’, because it is a reduplication, and ‘no’, because it didn’t happen in English but in French. And the English a is an anglicisation of French à.

I was wondering if the phrase is a bit, you know, passé, so I thought I’d take a gander at Google news.

Well, slap my thigh and knock me down with the proverbial feather! I find a UK site offering that succulent Greek lamb stew kleftiko for home delivery under the name of ‘Kleftiko-a-Go-Go’. Which suggests to me the phrase is alive and kicking – even if, sadly, the lamb isn’t.

But next I find a headline that’s real gold dust as regards my quest:

Out-of-control dump truck slams into iconic ‘Whisky a Go Go’ music venue in West Hollywood*

That accident happened back in May 2025; the point is not the accident but the name of the venue.

For that venue’s name is cloned on the Parisian venue which in a sense started the whole thing going, as the OED etymology makes clear.

Back in the mists of time – well, 1952, actually, which is as good as – a nightclub and discotheque opened in Paris with the name Whisky à Gogo, literally, ‘Whisky Galore’ and quickly became hip and fashionable.

Paris being a sort of fashion leader back then – and not generally subject to outrageous jewellery heists from its top museums – venues in other European countries followed suit and opened with the same name. The trend hit the US a bit later, and the Hollywood Whisky a Go-Go on Sunset Boulevard* opened in 1964 and to this day hosts bands.

Stellar bands who’ve played there include The Who, Led Zeppelin, The Jimi Hendrix Experience, The Byrds and many, many others. And into its hallowed walls slammed an out-of-control dump truck on 10 May 2025, fortunately not injuring anybody.

Image courtesy of the New York Public Library

Image courtesy of the New York Public LibraryThe OED gives a go-go two meanings, the first of which is first recorded from 1960 and means ‘fashionable, with it’ as in:

At the bar David the DJ bought the first round, ‘Trust me, Henry, Pernod and blackcurrant is a go go,’ he said with a smile.

J. A. Walker, Art-Lovers ii. 10, 1999

I have to say, that meaning is not in my idiolect.

The second meaning is the one I think most (British?) readers will know, i.e. ‘galore, in abundance’, and dates from 1961 according to the OED, which states ‘In early use frequently with connotation of modishness; now often used ironically.’

I’m pretty sure there was nary a hint of irony in its first recorded use, in the title of an ITV series showcasing pop bands that ran from 1961 to 1965, Discs a Go-Go. It featured stellar [no irony intended and none taken, I hope] bands and artistes such as Manfred Mann, Gene Pitney, The Searchers, The Spencer Davis group, The Animals and scores more.

What about that reduplication, though?In French, the phrase goes back to at least 1485 with the meaning ‘joyfully, uninhibitedly, extravagantly’ and might be the source also of English agog. The go element is apparently based on the archaic word gogue, meaning ‘amusement, fun, entertainment’.

There are two English reduplications of go-go, one to do with nightclubs and (erotic) dancing (1964), the other meaning a) possessed of boundless energy (1951) or b) fashionable, in vogue.

Carole’s own name for the glasses is ‘Go-Go Goggles’. Why? ‘Because they make me feel very go-go! Speeded up! Moving fast!’

Lubbock (Texas) Avalanche-Jrnl. 25 April 1965

Tri-color ski jackets: two go-go styles with nylon shells puffed out with polyfill.

New York Times 9 October (advertisement) 1981

How should I spell it?The world’s your oyster.

Oxford Online has a gogo;

But the examples it shows include agogo;

The OED has a-go-go;

Collins keeps the French accent à gogo;

Merriam-Webster online and Unabridged only seems to refer to senses of go-go and doesn’t cover the ‘abundantly’ sense.

Is it a very British thang?

UpdateThanks to three of my sistren folllowers, I ‘can now reveal’:

a) there was a famous Whiskey-a-Go Go at No. 4 Queen Square, Brighton in the early 1960s. it even featured in a TV documentary about teenagers and sex;

b) there’s an old pun about the nightclub for the over-80s, Disco-A-Ga-Ga;

c) that the synth-pop band Landscape in the early 80s released a track that rejoiced in the name of Einstein a Go-Go.

* In an irony of ironies, sort of (come back Alanis, all is forgiven) the band due to play rejoices in the name of Boy Hits Car.

** Who can type that address without thinking of the immortal film of the same name?

May 28, 2025

The cultural significance of ladybirds across languages

I’m not sure when I first knew about ladybirds – perhaps as a child of five or six. At that age you’re closer to the ground and so much closer to small creeping things than you’ll ever be again, able to observe them with that goggle-eyed curiosity born of novelty. The age when a lifelong passion for insects first fires up to forge you as an entomologist.

Or not, in my case.

I’m more of the etymologist persuasion, that inclination so often confused with the insecty one. Last spring, however, I was fascinated to see dozens of ladybirds on the stems and flowerheads of our Euphorbia amygdaloides var. robbiae, also known as Mrs Robb’s bonnet. That fount of all knowing, the interweb, tells me such a site for overwintering is not unusual. Ladybirds perform the useful task of snaffling aphids on an industrial scale.

Image courtesy Martti Salmi on Unsplash

Image courtesy Martti Salmi on UnsplashEvery day I get a Danish word of the day to help with my learning. One such was mariehøne, ‘ladybird’, literally ‘Mary hen’.

Which led me to ask where the ‘Mary’ part came from.

Your house is on fireUnlike me until recently, you probably already knew that the Mary in question is Our Lady of Sorrows, the Virgin Mary. The native British ladybird typically, but not always, has seven spots. Seven is the number of Mary’s sorrows, which start with Simeon in the Temple at the time of Jesus’ presentation:

‘And Simeon blessed them, and said unto Mary his mother, Behold, this child is set for the fall and rising again of many in Israel’

meaning that some will rise in faith and be blessed and others fall away. Then Simeon tells Mary: ‘Yea, a sword shall pierce through thy own soul also.’ Mary, ‘Our Lady of Sorrows’ or ‘Mother of Sorrows’, Mater Dolorosa, is portrayed in the goriest versions of Catholic art pierced by seven rapiers, as in this gloriously gruesome image from the Chapel of the True Cross (CapilIa de la Vera Cruz) in Salamanca, Spain.

Aged five or six I had no idea about all that bloodthirstiness. But what I do remember is, in company with other playmates, picking ladybirds delicately up and then softly blowing them off my hand to the incantation of ‘Ladybird, ladybird, fly away home, | Your house is on fire and your children are burnt.’ Nobody knows for sure how old it is, but it’s recorded in the earliest known book of nursery rhymes, Tom Thumb’s Pretty Song-Book of 1744, which measures a diminutive 3 x 13⁄4 inches, to fit snugly into a child’s paw.

And your children are burntOther languages load this inoffensive and beneficial insect with religiosity. In German it’s ein Marienkäfer (Mary’s beetle) and in Swedish Jungfru Maria(s) nyckelpiga (Virgin Mary’s keyholder, literally ‘key maid’). In Irish it’s bóín Dé, which I believe means ‘God’s little cow’, an association that appears in Russian too, with бoжья коровка and in Argentina with vaca de San Antón (St Antony’s cow). Presumably the spots are reminiscent of a cow’s hide.

May 21, 2025

What’s the opposite of a placebo?

Last week I posted about the mock-Latin origins of gazebo and, tangentially, about Jane Austen and ha-has.

My point about gazebo is that it imitates Latin, specifically, the second conjugation first-person future indicative. Two other words with the same grammar immediately come to mind: placebo and nocebo. One is familiar in its modern psychological sense but goes back to mediaeval Latin; the other is a relatively modern invention, far less often used than its positive twin.

You’ll probably have come across placebo in one of its two modern meanings; a) ‘a medicine or procedure prescribed for the psychological benefit to the patient rather than for any physiological effect’; or b) ‘a substance that has no therapeutic effect, used as a control in testing new drugs’ (definitions taken from the Online Oxford Dictionary).

The first meaning goes back to 1770 and is defined with admirable and elegant concision in this 1811 quotation from a medical dictionary:

Placebo,… an epithet given to any medicine adapted more to please than benefit the patient.

R. Hooper, Quincy’s Lexicon-medicum (new edition)

A 1938 quotation, from a journal of the American College of Physicians, sceptically and wittily explodes much of the history of medicine:

The second sort of placebo, the type which the doctor fancies to be an effective medicament but which later investigation proves to have been all along inert, is the banner under which a large part of the past history of medicine may be enrolled.

Annals of Internal Medicine vol. 11 1417

The earliest OED citation for the second meaning, i.e. as a control, is from 1950, but I’ve no idea if that is truly the earliest evidence for that use (trigger warning for those who prefer data as an uncount noun):

It is… customary to control drug experiments on various clinical syndromes with placebos especially when the data to be evaluated are chiefly subjective.

Journal of Clinical Investigation vol. 29 108/2

The scientific literature is full of examples of experiments where people have derived real physiological benefits from medicines or drugs which in principle exerted no actual effect on their bodies. In other words, any benefit may originally have been ‘all in the mind’, but it translated to the body.

If a placebo is a medicine given to a patient for its beneficial psychological effect, what, then, is a nocebo, literally ‘I shall harm’?

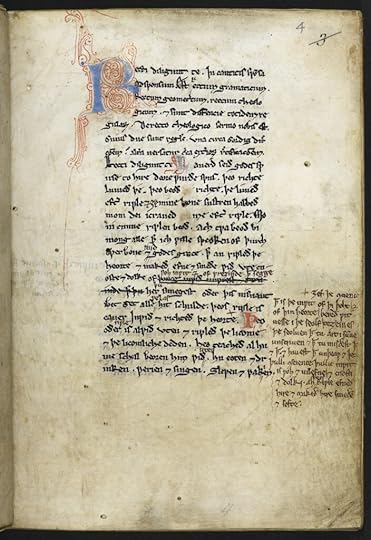

A page from the earliest copy of the Ancrene Riwle, held by the British Library, Cotton MS Cleopatra C VI, f. 4r.

A page from the earliest copy of the Ancrene Riwle, held by the British Library, Cotton MS Cleopatra C VI, f. 4r. Again, according to Oxford, it’s ‘a detrimental effect on health produced by psychological or psychosomatic factors such as negative expectations of treatment or prognosis.’

It’s first recorded from 1961.

That’s a harder idea to get your head around. A couple of the OED examples seem helpful. The OED also points out that it’s mainly used in the phrases nocebo effect and nocebo response and that it often applies to negative effects experienced after the administration of a placebo.

Attempts to define the secondary effects of placebos, i.e., the nocebo effect.

Encephale vol. 58 486 1969

Patients experiencing the nocebo effect… presume the worst, health-wise, and that’s just what they get.

Washington Post 30 April (Home edition) f1/2 2002.

I’ve looked for examples, and AI was helpful. For instance, patients might experience nausea or drowsiness when taking medication if they’ve been told they will, even if what they’re taking has no physiological effect because it’s a placebo. In other words, placebos and nocebos both illustrate how our expectations and beliefs can affect our experience in direct ways.

(Note, incidentally, the plurals in –os rather than –oes.)

Such thoughts were far from the mind of the person who first recorded placebo back in the early thirteenth century, in the Ancrene Riwle, the rules governing the life of anchorite nuns.

Like lavabo, discussed in last week’s post, the word’s origins are religious. It repeats the first word of the first antiphon of the Vespers for the Dead ‘Placebo Domino in regione vivorum’ (Psalm 114, Vulgate), ‘I will please the Lord in the land of the living.’

The other second conjugation verb in English we probably all know is habeas corpus. But that’s for another time.

May 14, 2025

Gazebos and Jane Austen – or not

As I write, my partner and I are on holiday in our favourite hideaway, buried in the heart of the Herefordshire countryside. Where we stay is a converted railway station on an extinct country line from Ross-on-Wye that was zapped by the Beeching Report in the 1960s. In its extensive gardens sits a gazebo where, weather permitting, we spend a lot of time chatting, browning our protruding legs and reading.

Image of a glorious gazebo courtesy of Brice Curry on Unsplash.

Image of a glorious gazebo courtesy of Brice Curry on Unsplash. A book I’ve been rereading here is Sense & Sensibility. Gazebo to me sounds very Jane Austen, just as a ha-ha does. But, disappointingly, a website that’s a thesaurus of every word she ever used assures me gazebos do not figure in her writings (but I’m happy to be corrected if someone tells me they do, and where). Nevertheless, I maintain it’s the sort of word that ought to have occurred, redolent as it is of some of the country estates — Mansfield Park, Barton Park, etc. – she set her comedies of manners in. Otherwise, you might think I was merely clickbaiting you.

And speaking of Mansfield Park, thanks to one of my readers, I am reminded that Austen situates a ha-ha at the grand mansion that is Sotherton, home of Maria Bertram’s betrothed, James Rushworth. On a walk in the grounds, Maria and Henry Crawford are determined to reach a knoll in the ‘park’, but the gate to the park is locked. Maria, egged on by Henry, decides she can slip round it, which horrifies her strait-laced cousin Fanny:

“You will hurt yourself, Miss Bertram,” she cried; “you will certainly hurt yourself against those spikes; you will tear your gown; you will be in danger of slipping into the ha-ha. You had better not go.”

The blindingly obvious phallic imagery of the spike tearing a gown, and symbolically, Maria’s virginity, foreshadows the disgrace caused by her later elopement with Henry Crawford.

Which language?Which language do you think gazebo comes from? Perhaps Italian, because of it’s –o ending, like piano or casino or ghetto? Or maybe Spanish? Or even Arabic, a gazebo being a bit like a tent travellers across the sands might pitch?

If it’s possible to describe words as ‘made up’, this one certainly fits that bill. It’s probably an invention based jestingly on Latin: it jokingly conjugates to gaze as if it were a Latin verb gazēre, ‘I shall gaze’, in the first-person singular future indicative.

No doubt, whoever first coined it and the people who first heard it thought it a terrifically clever learned wheeze. The OED first cites it from 1741, well before Jane Austen’s birth (1775), in a work by the Irishman Wetenhall Wilkes titled An Essay on the Pleasures & Advantages of Female Literature:

Unto the painful summit of this height | A gay Gazebo does our Steps invite. | From this, when favour’d with a Cloudless Day, | We fourteen Counties all around survey.

Mr Wilkes was clearly a bit of a mansplainer avant la lettre. Another work of his was A letter of genteel and moral advice to a young lady: being a system of rules and informations, digested into a new and familiar method, to qualify the fair sex to be useful, and happy in every scene of life.

His poetic lines display one meaning of gazebo, ‘A turret or lantern on the roof of a house, usually for the purpose of commanding an extensive prospect’ as the OED puts it. But nowadays the word means a roofed or tented structure in a garden, with open sides to provide shelter from the elements while allowing a view from within. These can be pop-up affairs with a canvas or similar roof, to provide shelter on beaches or in gardens, or sturdy, solid constructions, like ours, with its wooden posts, beams and roof.

If mock-Latin is indeed its origin, gazebo is not the only first-person singular future indicative Latin verb lurking in English. If you visit ruined monasteries, as we often do, the guidebook may draw your attention to a lavabo for the monks, a trough or basin for them to wash their hands in, sometimes built into a wall and furnished with a water supply and a drain. Wenlock Abbey has a notable free-standing one.

Lavabo, the physical object, comes from the earlier lavabo, the ritual washing of hands by the priest during celebration of the Eucharist, at which he recited Lavabo inter innocentes manus meas, ‘I shall wash my hands among the innocent’ (Psalm 26:6ff.). Since Vatican II, this has been replaced by Lava me, Domine, ab iniquitate mea, et a peccato meo munda me (‘Lord, wash away my iniquity; cleanse me from my sin’).

Lavabo is from a first conjugation Latin verb. Two more futures from the second conjugation are placebo and nocebo. I’ll come back to them in the next post.

April 30, 2025

Another cod etymology bites the dust.

February 17, 2025

An expert talks about ‘Words of the Year’ – what they are and what they’re not.

January 25, 2025

Burns Night and Burns Suppers

This 25 January, as every year, people in Scotland, Britain and the worldwide Scottish diaspora will gather merrily to celebrate the birth date of Scotland’s national poet, Robert Burns. Though it’s a gathering now as jolly as any birthday party, the event started life as a commemoration of Burns’ death in 1796 at the young age of thirty-seven. In 1801, a group of nine of his friends met at the Burns Cottage in Alloway, Ayrshire, on what would have been his birthday to reminisce about him and then turned their gathering into an annual event. Now it’s celebrated by countless millions. Other poets, like Keats, Shelley and Chatterton died untimely, but none has ever lodged so firmly in so many people’s hearts.

Over the decades and centuries since that first gathering an order of service, as it were, has sprung up for Burns Night or a Burns Supper. But a Google search suggests plenty of uncanonical interpretations, such as a Burns Supper on a double-decker bus, an underwater Burns Supper (how?) or on the former Royal Yacht Britannia. Some venues even seek to cash in on the occasion by turning it into a fully-fledged Burns Day.

Apologies to those who know the drill like the back of their hands. What follows is for those unfortunates who won’t be attending a Burns Supper, or for novitiates.

And some wad eat that want it;Exact arrangements vary, but the running order of a typical Burns supper goes like this:

The host – or staff member acting as such at a commercial venue – says a few words about why everyone’s gathered, and when people are seated, recites the Selkirk Grace.

Its four lines, shown in the headings of this post, celebrate our good fortune in having enough to eat and thank the Lord. They’re in Scots and display typical features: verb forms differing from Standard English, like hae (‘have’), wad (‘would’), thankit (‘thanked’), and different spellings reflecting pronunciation, like sae for ‘so’.

It’s popularly believed that Burns wrote this grace. He didn’t. It existed in the seventeenth century as ‘The Covenanters’ Grace’. Burns recited it at supper at the Earl of Selkirk’s – there’s still an earl of that title – in 1794, and at other times, so it became indelibly associated with Burns’ name.

If there’s to be a starter a soup as hearty and nourishing as Cullen skink or cock-a-leekie would be appropriate. Some eateries will serve the haggis as a starter or even a ‘gateau’ and then have a meat main dish, which might include skirlie (yuy-yum) as an accompaniment.

But the highlight is of course the presentation of the haggis, traditionally piped in on a silver salver. At home, you might serve it more simply on an ashet.

Both words are interesting. Salver took the French salve and added an –r to give an –er ending on the analogy perhaps of platter; ashet is a reformulation in British mouths of French assiette, ‘plate’ and is a mainly Scots word.

The host or other officiant then recites Burns’ famous ‘Address to a Haggis’. Only after that can people tuck in to their haggis, which should always be served with neeps (short for turnips) and tatties (Scots for potatoes). And often with a whisky and cream sauce.

On the perennially vexed question of ‘when is a turnip not a turnip’, what Scots mean is often Brassica napus, which others would call a ‘swede’ or ‘rutabaga’, as opposed to the smaller and generally white-fleshed Brassica rapa turnip. Funnily enough, though neeps might be Scots, and dialectal elsewhere, it comes from Old English næp, which is a direct borrowing from the Latin nāpus you can see above in the botanical name.

But we hae meat, and we can eatRemembering the whole ‘Address to a Haggis’ is a major memory feat, especially because several words may be unfamiliar to the reciter outside the world of the poem. Possibly, the simple rhyme pattern AAABAB helps, as it gaily drives the narrative forward over the work’s eight stanzas and forty-eight lines.

For those pressed for time, here’s my free summary. Please spare the brickbats.

What a glorious-looking and -smelling thing is a haggis, the pinnacle of pudding perfection! As men race to tuck in, one man who’s fit to burst says grace. Forget your fancy foreign grub: it would give a sow the boke and so enfeeble men they’re like a withered rush. The haggis-fed rustic with sword in hand will hack off heads and limbs like thistle tops. Give Old Scotland haggis, not poncey soups!

For anyone wanting the organ grinder, not the monkey, the link to the unadorned full text is here.

If you know none of the rest of the poem, many readers will, I’m sure, be familiar with the opening couplet.

Fair fa’ your honest, sonsie face,

Great Chieftain o’ the Puddin-race!

It’s worth stating, because we’ve probably forgotten through familiarity, that addressing a haggis is a startlingly novel and hilarious example of personification, designed to bring a smile to the listeners’ faces from the start. And if you’re wondering how a haggis can be a ‘pudding’,* it very much is one according to the fourth Collins definition: ‘a sausage-like mass of seasoned minced meat, oatmeal, etc, stuffed into a prepared skin or bag and boiled’. In haggis, the ‘minced meat’ is lamb.

Fair fa’ your honest, sonsie face,

Great Chieftain o’ the Puddin-race!

‘Fair fa’ in that first line is a formulaic ‘expression of blessing’, using the Scots variant fa of fall. Sonsie is a highly polysemous word, to use the lexicographical jargon: it has many meanings. As part of personification, the line reapplies the meaning ‘comely’ or ‘bonny’ from people to a thing, as you can see in 3 (3) of the Dictionaries of the Scots Language online. In that same entry, there’s a nice quote for another meaning of sonsie, ‘engaging and friendly in appearance or manner’: ‘Burns was handsome and sonsie, courteous and brave, clever and self-perceptive.’

I’d love to go on with my commentary, but there’s not room. And you may be relieved. If you wish to explore further, this link has a parallel translation in Standard English. And this one glosses the unfamiliar words. There, that should cover all bases.

Poor devil! see him owre his trash,

As feckless as a wither’d rash.

The only other linguistic comment I’ll make is that feckless in stanza 6 means ‘weak, feeble’, not its often-used meaning of ‘irresponsible’.

And sae the Lord be thankit.Back at ‘the order of service’, after the haggis or main course, there could be pudding or dessert. (I noticed several venues offering cranachan, yum-yum, a Scottish Gaelic word.)

There could be another Burns reading.

Next comes the section when the host or speaker comments on Burns’ importance and legacy in the ‘Immortal Memory’.

Then there could be a further Burns reading, followed by a ‘Toast to the Lassies’, who may then reply with ‘A Reply to the Toast to the Lassies’, sometimes called ‘Toast to the Laddies’.

Finally, there could well be some Scottish dancing to a band in a ceilidh, another Scottish Gaelic word (pronounced KAY-lee). And then a rousing rendition of ‘Auld Lang Syne’.

I’ve left a couple of words uncommented. So, to finish, whisky is from Gaelic, shortened from whiskybae, from Scottish Gaelic uisge beatha, literally, ‘water of life’. And if you take a ‘wee dram’ of whisky, you’ll be using a word, dram, that goes back to the Classical Greek drachma, the coin. How so? Because fifteenth-century apothecaries brought it into English from French, which in turn took it from Late Latin, as a unit of measurement supposedly equivalent to the weight of the coin, or one-eighth of an apothecary’s ounce.

Cullen in the Cullen skink starter mentioned is a wee village on the North-East coast of Scotland. The skink is from a Middle Low German word meaning a ‘shank, shinbone’ and is directly cognate with Modern German Schinken and Danish skinke, ‘ham’. You see, before fish became part of the recipe, a shin of beef would be used to make a skink, a potage or soup.

That same noun skink produced the verb in the final stanza of ‘Address to a Haggis’, meaning the thin, clear, watery soups that Burns objected so strenuously to.

Auld Scotland wants nae skinking ware,

That

jaups

in luggies.

(‘splashes in small wooden dishes’)

My partner and I will be celebrating in York.

Meanwhile, wherever you are, here’s a toast to you on Burns Night: slàinte mhath! (slan-jee-var).

* I expatiate on puddings in this November post for British Pudding Day.

This is a version of a post originally published on the Collins Dictionary site here.

Image: courtesy of Nina Garman on Pixabay.