Andrea M. Jones's Blog

September 29, 2025

For Mom

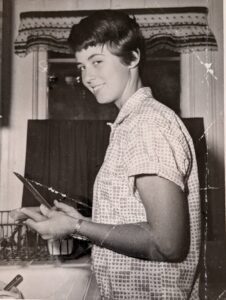

Amonda Marie Jones, 1940-2025

Amonda Miller in 1958. A few months later she became Mrs. Jones.

On November 3, 2000, my mother closed on the sale of her townhouse in Loveland, Colorado.

“I’ve always wanted to live in a big city, New York or San Francisco,” she had told me, announcing her plan to move. “If I don’t do it now, I never will.”

The date of the real estate closing coincided with her sixtieth birthday.

She headed east two months later. Her little black Dodge Neon, stuffed with enough essentials to launch her new venture, was aimed toward Brooklyn, where the youngest of my three older brothers lived. He’d attended Columbia University in the early 80s and never left New York. He made a few introductions, and in short order Mom had found a one-bedroom apartment about a mile and a half from where he lived in Williamsburg and was negotiating with a family in Manhattan that was looking for a housekeeper/nanny.

She started becoming a New Yorker by mapping her local precincts on foot. Unlike the simple grid of streets and avenues that covers most of Manhattan, the Williamsburg section of Brooklyn is a jumble. The area encompasses multiple historic towns that were platted on different orientations, creating a patchwork of neighborhoods with streets running on, and meeting at, wonky angles. The sweeping ramps serving the Williamsburg Bridge and the elevated tracks of the JMZ subway lines overlie the muddle, while the Brooklyn-Queens Expressway cuts through it all with a multi-lane slither and incessant roar. The human inhabitants are, if anything, an even wilder mashup. A more extreme contrast from the small-town homogeneity of Loveland would be hard to find within the continental US.

Mom settled into her routines within the chaos, bargain-hunting in the cramped grocery stores, schlepping her beer home from the closest bodega, commuting to Manhattan on the L-line. At work on the Upper West Side, she learned the ropes of high-rise New York, albeit from a working class perspective.

She was an anomaly: a white-haired white lady in a job most often filled by immigrants or women of color. I tagged along once or twice while visiting, alternately amused and in awe of the streetwise mien she adopted in the city. Her walk matched the hustling pace of a stockbroker late for a meeting. She snapped at interlopers who bumped into her, kept her wallet hidden, held her own in the gladiatorial queues of the Zabar’s deli. One jeans pocket was reserved for quarters and one-dollar bills, which she doled out to a handful of street people she’d come to know by name. One of her duties was passing on her newly-honed street smarts to her employer’s daughter, an over-protected teen who had grown up in Manhattan but had never learned to navigate on a bus or the subway.

She hadn’t left for work yet on September 11, 2001, when the planes hit the World Trade Center. My brother and brother-in-law were on vacation in Europe, their return flight delayed for almost a week. In the aftermath of the towers’ fall, when a collective spirit permeated the city more thoroughly than the dust and smoke, Mom’s fealty to her adopted home town was cemented.

***

1972

She had already made plans to fetch the rest of her belongings and furniture in Colorado that fall, and in late October we loaded up a rental truck and set out on the cross-country trip together. Engine noise permeated the cab, and every panel, bolt, window, and seat frame rattled incessantly. The radio only added to the din and we had to yell to converse, so mostly we didn’t. When I wasn’t driving (and sometimes when I was), I made a game of counting red tailed hawks perched on power poles along the interstate.

There was never any question that Mom would drive the final leg, from New Jersey into Brooklyn. The tunnels into Manhattan were still closed to trucks, so we roared across Staten Island and the Verrazano-Narrows Bridge and then along the western edge of the vast sprawl that is Brooklyn on I-278, aka the BQE. We had waited until late evening to tackle the crush of urban driving. Traffic was light enough to be moving at freeway speeds, which only made the ride more terrifying. The lights of the altered Manhattan skyline must have risen in front of us and then shifted to our left as we traveled north, our surroundings lit by amber streetlights and the autumn dusk, but I don’t remember much other than the noise and Mom, leaned toward the wheel, checking her mirrors in rapid-fire sequence, gunning the truck toward her little apartment on Lorimer Street.

It’s in that passage, perhaps—the motor’s high-pitched grinding, the jarring crash of potholes, the crappy pavement chattering the cab’s hard surfaces, the enveloping crush of aggressive New York driving—that the mini-story I’d tell for years about my mother took shape. On her sixtieth birthday, I would say, my mom left the life she’d known, packing up and heading to The City. “I hope I’m that ballsy when I’m that age,” was the inevitable concluding line.

I don’t know how many times I delivered that punchline over the next couple of decades, but I repeated the story whenever I was in a position to explain why my mother lived in New York and not Colorado. When I turned sixty myself in April this year, I realized I’m going to have to update my script. The question implied by the line has been answered. Will I be that ballsy at the age my Mom was then? No. Not even close.

***

New Year’s Eve 2009, in NY, gussied up for one of the notorious New Year’s Eve parties hosted by my brother Doug and brother-in-law Koitz. Photo credit Koitz.

While Mom went urban, I went wild. Her move to NYC roughly paralleled my own migration from Boulder to rural central Colorado. Doug and I had bought this property, part of a subdivided ranch, in 1995, and in the spring of 2001 we began the years-long process of establishing a home here. We built a barn with an attached cabin, living there while the house was under construction. We set up a walled garden, fenced pastures, got horses. Doug sold wine, I wrote and indexed books from home.

Mom, meanwhile, got doormen, building superintendents, and my brother’s friends hooked on her homemade cookies, banana bread, and deviled eggs. She picked up freelance seamstress gigs and hoarded her beer cans for the elderly Haitian woman who made late-night rounds collecting recyclables in a rattling shopping cart. She took in museums and attractions, exploring the city’s boroughs via public transportation, in her car, and at times on foot, saving the maps and guides she collected during her peregrinations in a decorative tin on the end table next to the couch. Always a news hound, she luxuriated in taking the New York Times as her daily hometown newspaper.

A few years after settling in the city, she found a place, as they say, “upstate.” The proceeds from her Loveland townhouse bought her a very old and slightly decrepit little house on the west bank of the Hudson River in a town called Coxsackie. She finally stopped working in her late 70s, spending her time puttering in the yard and on unceasing projects around the house. She adored the river and its traffic of barges and boats, although it was a difficult love, given that the Hudson in flood stage would wind up in her basement. She sold the house in 2020 and moved back to Brooklyn full time. She and her part-time roommate shared the first floor apartment below my brother’s place.

***

As much as I’d love to report that Mom lived out her days as a New Yorker, she took an abrupt skid into vascular dementia in January, 2024. When caring for her at home became too much for me and my brothers, we decided to move her back to Colorado, near me. She was philosophical on the late September morning when I broke it to her that she had to leave. She obliged as we packed, climbed into the Uber, sat calmly in the wheelchair as we navigated the terminal at Laguardia. On the plane, she stole my brother’s beer, but was otherwise stoic. As we were driving south from the airport, though, bound for a memory care facility in Colorado Springs, she broke down in sobs.

Mom died on February 21, 2025. There are many, many things about the last fourteen months of her life I wish were different. We were all helpless in the face of her psychosis and cognitive decline, but denying her the opportunity to die in the home place she had chosen for herself haunts me. Perhaps I’m projecting my own attachments onto her. I know what it feels like to find your place, an environment that gives you the sense that you can be the person you were meant to be. At sixty, I’ve had the unbelievable good fortune of having lived in that place for almost twenty-five years. Mom, at the age I am now, was still searching.

Mom and me at my wedding, June 1998.

My mother was born in Pueblo, Colorado but mostly grew up in Chico, California. She regularly visited an aunt who lived in Pueblo, and that’s where she met and fell for my dad. She was eighteen and pregnant when they married on New Year’s Eve, 1958. All four of us kids were also born in Pueblo, in the span of six years. Dad divorced Mom in 1978, a couple of years after she’d left him, and us. My theory for her departure is that she had come to regard herself as too damaged to live in the same house with us without hurting someone. She worked hard to stay present in our lives in various ways; she went to New York, in part, to be near my brother. But the fracture that ran through our growing-up has mostly made itself known through silence.

My mother was an introvert and a loner and it feels right to say she buried her emotions under hard work whenever she could. She was opinionated and honest, with a cutting wit and a sharp tongue that she increasingly kept sheathed as she grew older. It’s not possible to capture the scope of a person in a few words. But as I seek to memorialize Mom without soft-pedaling her stubborn reclusiveness, that quarter-century in New York shines in my mind. It occurs that she most loved the city for its quintessential characteristic: despite its density, noise, and diversity—or perhaps because of those qualities—it preserves solitude for the individuals who crave it, even as it opens spaces, however narrow, for them to insert themselves in the human flow, and ebb.

August 16, 2025

In the Blue Mist

A run of wet weather the first week of May delivered two inches of precipitation on our place. This quantity might be shrug-worthy in some parts of the world, but in this semi-arid region, two inches can be a notable accumulation for an entire month. To receive that much moisture in seven days felt almost miraculous.

Almost.

I don’t want to sound ungrateful, because I wasn’t then and I’m not now. But virtually all of this precipitation fell as snow, and it had been a very long winter, in more ways than one. Even though most of it melted as it landed, it was still snow. Maybe it was the sheer visibility of it, the individual flakes traceable as they drifted down from the gray skies, that pushed me to the edge. I knew the white would (eventually) yield, but I felt desperate for a sign of something, anything, more spring-like. At one point, I stomped out onto the deck outside the kitchen and yelled: “There’s such a thing as RAIN, y’know!!”

The snow did stop eventually. Clouds yielded to clear skies, unleashing the age-old botanical response. The grasses greened and the wildflowers set about making blooms out of water and sun.

I’m fond of saying that plants in this part of the world like their space. Grasses, shrubs, wildflowers: they all claim their patch of ground, and the light and water that comes with it. The dry environment is not conducive to mass displays of fecundity. Meadows and evergreen woods achieve coverage of bare earth, but layering is pretty minimal, unless you count lichen as understory. Wildflowers, in particular, are spaced out, each plant putting itself on display in a frame of grasses, more a confetti scattering than mass assembly. With one exception.

Blue Mist Penstemon (Penstemon virens) doesn’t mind the company of its kin—if fact it prefers it (one source I looked at recently asserts that plants are rarely found singly). The species likes open sites with an unobstructed south-facing view. When conditions are right, as they were this year, their congregations do indeed create the effect of a pale smoky-blue mist on the rocky slopes they prefer.

Although the display is notable—the only landscape-scale equivalent is fall color—it is more ethereal than teeming. On first glance and from a distance, a patch of flowers might be mistaken for an area of frost, dew, or the shadow of a cloud. Unlike a shadow, however, the haze emanates color instead of dampening it. As you get closer, the violet-blue gauze becomes more intense, and since the plants tend to grow on exposed hillsides here, an aficionado can play with the color saturation, chromatically shifting the pastel wash into concentrated strokes of intense sky blue by lining up an eye-level perspective.

I picked up this trick during a couple of morning drives to fields of the flowers along the county road in June. I wandered around, taking pictures and playing with light and shadow, slope and distance. Although the stands were thick by the standards of this ecoregion, meandering into their array tempered my impression of density: it wasn’t hard to walk through the “mist” without stepping on a flowering stem. In the flowers’ midst, I caught a delicate scent, sufficiently subtle and fleeting to defy description other than “faint whiff of floral,” suggesting that they deploy other attractants to seduce their pollinators. Another nuance I would not have noticed without getting out and into an expanse of the blooms was the variability in flower color.

Penstemons are native to North America, where their tolerance of dry conditions skews their populations westward. Botanists have documented upwards of 270 species in the genus, flowering in a range of colors from white, pink, and lilac to cobalt blue, royal purple, and deep red. The group shares some broad characteristics, notably erect stems bearing tubular flowers. Many species offer their blooms arranged along one side of the flower spike, like pennants unfurled in the wind.

Their common name, beardtongues, is attributed to the hairiness of a sterile fifth stamen, often nestled like a tongue at the bottom of the flower opening. Viewed from the front, a single bloom of P. virens does resemble a caricaturist’s rendering of a goofy mouth, complete with the narrow tongue, and, in some cases, crooked white teeth formed by the pollen-bearing anthers on the upper stamens. The voluptuous lips are purple rather than red, a fashion statement designed to appeal to insect pollinators rather than hummingbirds.

***

My diligence at botanizing ebbs and flows. I’m consistent in my admiration of our local flora, but I don’t always pursue identification in the field guides I’ve accumulated over the years. Even when I do look a plant up, descriptions and photos often don’t quite match the individual in front of me. In this case, however, my confidence in the identification is high. In fact, given that penstemons don’t tend to congregate, the appearance of this variety in such large swatches affirms that I’m looking at P. virens even from a hundred and fifty yards away.

Other validating clues lie in the plants’ height; by penstemon standards, the flower spikes are stubby. I live within the limited range of the species, too, which is confined to the foothills of Colorado and Wyoming (one of the other common names for the plant is Front Range Beardtongue). And, to give credit where credit is due, I didn’t make the initial identification myself. When I confessed my ignorance in a post dated July 1, 2019, friend and botanist Susan J. Tweit commented that my “little purple penstemon that blooms earlier than most of the penstemons” was P. virens.

That early bloom time is one point of gratitude among many, a reward enjoyed after the long winter has definitively ended. The wash of color isn’t reliable—some years the mist is more of a faint sprinkle that’s impossible to see without frank attention—and it comes too late to be a harbinger of spring. More than seasonality, then, or the regular cycles of phenology, virens speaks of opportunity: when conditions are right, erupt, unfurl, and smile into the sun.

January 21, 2025

Home Work

Although the title of this blog* bows to the influence of the urban, my efforts skew toward accounts of the wild. This is by design, since the preoccupations of everyday life have a way of steering our attention toward human (aka urban, in my scheme of things) concerns: social interactions, commerce, politics, and all the stuff of our built environment. I have a significant editorial bias against references to current events, too, which seems fair enough given that online spaces are so amply supplied with news from, commentary on, and triggering pertaining to such concerns.

I like to try to distribute some perceptual ballast toward the less-peopled world by way of writing about plants and wildlife and weather and rocks. If there’s an idealistic tint to anything I do here, it has to do with advocating for attention. I aim to single out the particulars of this thinly populated rumple of the central Rockies because they’re at hand and they delight or amaze me, but the subtext is that attending to the natural world has taken on fresh urgency in our tech-addled era. The purveyors of digital “content” would like to persuade us to keep our eyes locked on screens, but our societies and economies function within a wider and wilder reality. We are, all of us, suspended between urban and wild.

I like to try to distribute some perceptual ballast toward the less-peopled world by way of writing about plants and wildlife and weather and rocks. If there’s an idealistic tint to anything I do here, it has to do with advocating for attention. I aim to single out the particulars of this thinly populated rumple of the central Rockies because they’re at hand and they delight or amaze me, but the subtext is that attending to the natural world has taken on fresh urgency in our tech-addled era. The purveyors of digital “content” would like to persuade us to keep our eyes locked on screens, but our societies and economies function within a wider and wilder reality. We are, all of us, suspended between urban and wild.

During my unplanned hiatus (which will be, presumably, brought to a close with these words), home served as more refuge than muse. This might sound cozy and reassuring, and it was at times, but the narrow scope of my attention also made me feel passive and self-indulgent. I slipped into a habit I once vowed I would never indulge in: regarding my surroundings as mere scenery. Successfully projecting my desire for serenity on these rocky hills, I shut down every other possibility they held for me.

Realizing this fired up my determination to get back to this, my home work, which was great. That the energizing surge occurred in the depths of winter was rather less so.

January at our elevation and from our exposed position makes for unkind outdoor conditions. As I write today, for instance, we are experiencing a daytime high temperature in the low teens with gusting windspeeds in the mid-thirties. Snow that fell night before last is airborne, swirling up rather than drifting down. When I went out to hang haynets for the horses, Harper—who is normally aloofly bossy—expressed her anxious displeasure with a string of plaintive whicker-whinnies, the likes of which I’d never heard her utter before. If I had a translate button, I wager that the transcript would read Wh-wh-h-hh-y-y-y-y? Wh-wh-h-hh-wh-y-y?? On the way back inside, I detoured to retrieve the snow shovel I left leaning next to the door yesterday. The wind that had sent it skidding across the driveway proceeded to snatch it back out of my hand.

This weather calls for indoor pursuits: a book or a fire or a book in front of the fire. You might think it would be a good day for writing, but my office is perched on the top floor of the house, where it takes the full brunt of gusts revving up the ramp of the slope below. The north-northeast wind shuddering the wall six feet behind me is impossible to ignore. The noise doesn’t distract so much as it takes up residence in my skull, disrupting my concentration at a cellular level. My synapses refuse gentle musing, firing nothing but snarling complaint.

In the spirit of getting back to work while excusing myself from any obligation to go outside, I’ll note here that during the interval when this site languished, static, it also passed a milestone. My first post on Between Urban and Wild (The Blog) went live on November 7, 2013. I set up the website to coincide with the release of Between Urban and Wild (The Book—which can still be ordered here or from your favorite bookseller). I’m dismal at promotion, never mind self-promotion, so it’s doubtful the blog ever did much to drive sales, but over time I discovered other benefits.

In the spirit of getting back to work while excusing myself from any obligation to go outside, I’ll note here that during the interval when this site languished, static, it also passed a milestone. My first post on Between Urban and Wild (The Blog) went live on November 7, 2013. I set up the website to coincide with the release of Between Urban and Wild (The Book—which can still be ordered here or from your favorite bookseller). I’m dismal at promotion, never mind self-promotion, so it’s doubtful the blog ever did much to drive sales, but over time I discovered other benefits.

There was, first and foremost, the incentive to get outside and look at, and for, interesting things to share. Beyond that, though, I discovered I actually quite liked blogging*. I’m neither prolific nor particularly diligent, obviously, but I appreciate the quiet persistence the form encourages. I’ve produced enough short essays that, were I to compile the more substantive posts into a single document, they would add up to a respectable book manuscript. For many writers this rate of production over more than a decade would be laughable, but I’m stubbornly unambitious as well as being a very slow writer.

Given that, the discipline required to complete each step in its turn—conceive, draft, revise, format, proofread, publish—is good for me. The form urges concision, encouraging me to curb my habitual long-windedness. The extent of my editorial control is both heady and intimidating. I’m free to follow my whims in this little backwater of the internet, but I’m simultaneously responsible for drivel and typos. Since my outputs are, theoretically, at least, visible to the world, I try not look like, or be, an ass.

And so: back to work.

Back to watching the ravens, trying to think of fresh ways to account for their contortions on windy days, twisting skyward like broken black umbrellas. I’ll obey the sharp chirps of the juncos and throw them some birdseed; once we started feeding them in winter, our interactions have become unambiguously transactional. I’ll look for the cottontail rabbit who lives under the horse trailer, leaving trails of dimpled tracks beyond its wheeled hatch cover, evidence that he or she has not yet become owl bait. When I pause to take in the igneous stain of sunset while feeding the horses, I’ll remind myself to think of it as a provincial representation of our collective ride on the solar system’s merry-go-round.

I’ll wander over the grasslands or down a timbered slope, looking for something I haven’t noticed before.

After the wind quits.

* How I dislike this term. Onomatopoetically, it sounds like the slow accumulation of dreck in a sink drain. But you know what I mean when I use it.

December 26, 2024

Fast Forward

The break has been as overextended as it was unintended.

Life intervenes; the necessary asserts itself over the preferred and chosen. It’s an old story, familiar and not particularly interesting.

It would be easy enough to disregard the time elapsed, but in place of that, I offer a visual retrospective, a sampling of images to represent a few slices of life since last I showed up here.

Bobcat through the kitchen window.

Pasque flowers, May 2023.

Solstice lightning.

Cordilleran Flycatcher nest in the planter between the garage doors.

Swallowtail in the garden.

Harper and Jake.

Lower Manhattan through the Williamsburg Bridge.

Partial annular eclipse, October 2023.

Eclipse through the colander, with leaf cutouts transformed into fish.

“Who you lookin’ at?” Mantises in Cañon City, CO.

Sunset, looking south. January, 2024.

Crocuses in the garden, March 13, 2024.

30 inches of snow in the garden, March 14, 2024.

Indian paintbrush.

Baby rattlesnake.

Bumper cherry crop 2024

Monster Meyer lemon 2024

Jake and Harper

Summer bunny posing

Mid-town Manhattan from Williamsburg

Orb weaver in the hall window

Fat buck

April 2, 2023

The Long Haul

Twenty years ago, in March 2003, we were getting ready to move. Hubby Doug and I had spent the previous fifteen months living in “the cabin”: the little studio apartment adjoining the barn we’d built two years prior. We were in the process of settling down on our rural property in Colorado’s north-central Fremont County, living in the cabin as we built the house. A woodburning stove delivered heat, we relied on a hot plate for cooking, and our bed doubled as couch and reading chair—as well as hiding the plastic bins in which we stowed canned goods and clothes. Although we enjoyed the luxury of a bathroom with in-floor heat, we were entering our second spring living in a single room: cabin fever was well advanced.

Just up the hill, 240 steps away, an entire house awaited: bedrooms separate from the living room and kitchen, full-sized appliances, top-floor offices with wraparound views. The building contractors had two more days of work scheduled, but had already hauled away the roll-off dumpster (much to the dismay of the local ravens) and port-a-john. Our final inspection was scheduled for Wednesday, March 19; we planned to clean and organize for a couple of days and start moving in over the weekend. I had already used the new washer and dryer, having determined that schlepping baskets of laundry up and down the hill was more convenient than hauling dirty clothes to the laundromat in town, 30 miles away.

The snow started around noon on March 17. We gave up trying to keep the driveway plowed the following day, resigning ourselves to being snowed in. Under the circumstances, the tight quarters of the cabin felt snug. A raging wind out of the north battered the wall next to our heads, but we had wood for the stove, a sufficient pantry stashed under the bed, and a pretty unbelievable wine cellar stacked in boxes in the hall. On the eve of our second night of listening to the wind scream as it hurled snow around the low-slung building, I commented in my journal that we enjoyed truffle risotto with a bottle of Anderson Conn Valley Pinot Noir for dinner.

The next morning, my alarm clock was the expletive Doug uttered on opening the door. The swirling winds that had plastered the windows white had finally calmed, leaving the walled garden substantially filled with snow. We suited up in coats, boots, hats, and gloves and, skirting the bulk of a drift that would have reached my forehead if I stood in it, wallowed over to the gate. That aperture to the outside world was immobilized by drifts on the far side, so Doug gave me a leg up over the wall and tossed me a scoop shovel. After marveling briefly at the front wall of the barn—crusted entirely white, like a set in Doctor Zhivago—I started digging.

An account of the long trek from the cabin to the new house would become a set-piece in the stories we were starting to accumulate about life in these parts. A walk that normally takes a few minutes was a half-hour thrash, as we floundered from one snowy trough to the next. We figured the average depth approached three feet, with the tallest drifts looming almost triple that—although the drunken meander of our path took us across bare ground in a few places.

In the two decades since, the house has been the envelope into which we fold our days. Within these walls, we prepare our meals and clip our toenails (not at the same time); we sleep and work, read and watch TV, host friends (too rarely these past few years) and celebrate and mourn. We talk about the horses, plans for the day, the news, finances, plans for the future. We drink wine and clean and putter, leave and come home, avoid projects and, occasionally, dive into them.

We live in the house, in other words, which is what people do in houses, for the most part. But my awareness of the land that surrounds us—call it landscape, call it environment, call it place or geography or retired ranchland—infiltrates and shapes this living in ways I’d like to think are unusual.

One of the things I unpacked into this echoey and comparatively vast space twenty years ago was a budding self-image as writer of place and a determination to pay attention to where I am. Living in the sort of location where most of us go to “get away from it all” offers endless opportunities to contemplate dynamics between people and aspects of the world that aren’t built according to human preferences and economies. One of the surprises of living in a sparsely developed area, to me, is not how sharply evidence of the constructed domain—the roads and houses, ponds and power lines; the fences and mining leach-heaps, jet roar and wind-borne traffic rumble—stands out, but how easy it is—how natural—to want to edit those features out. Ten years after we moved into the house, I published a collection of essays that emerged from running such ideas through slow iterations of reflection and revision. In advance of the release of that book, ten years ago this fall, I launched this blog as a way of continuing to exercise that mindset.

To my considerable good fortune, the result has been an entanglement of my sense of “being home” with the place in which the house was built as much as with the building itself. I’ve come to think of going outside to see what’s happening as part of my job: a pretty good gig.

Like many other rural residents, however, I find that the imperatives of earning a living sometimes involve picking up work off the property. That mundane reality consumes energy and time is one of the everyday complaints of people who like to write: overcoming or resisting distractions is a perennial challenge and frequent topic of tautological scribing. Long story short, for months I’ve found myself busy elsewhere, and drained while I’m at home.

A desire, if not a determination, to write surged at times. Noodling over a possible blog entry late last summer, I took pictures of the Slender-tube Skyrocket that now bloom outside the kitchen windows in July and August. I thought I would write about the extended process of collecting seed and trying to get plants established on the skirt of barren ground around the house after construction was complete. I’ve touched on this idea before, but I hoped to dig deeper into the temporal aspects of the topic, writing about the sense of growing more rooted to my place. I’d even settled on a title, which is, for me, often one of the most vexing aspects of pulling together a self-contained essay; I would call this piece “The Long Haul.”

But the ephemeral nature of the flowers’ blooming soon made the idea feel dated. The delicate trumpets that weren’t eaten by deer faded, dropped, and set seed. Once the snow began to fly, featuring summer wildflowers felt out of step.

Months later—on Christmas Eve, to be exact—I was picking orange Sun Gold cherry tomatoes off dried vines I’d strung up in the greenhouse back in October. I was making mental notes for a new post, this one having to do with the adaptations necessary for sane gardening in a short-growing-season environment like mine. Conveniently, I already had a title: “The Long Haul.”

Outside events continued to impose, however. I had preserved the tomatoes in the food dehydrator, and as January advanced the topicality of my topic began to seem similarly juiceless.

January departed and February wore on. The theme of long hauling was taking on a different meaning, and not one I was altogether eager to explore in public. As March approached, it occurred to me that the twentieth anniversary of our move to the house was approaching: another, and newly apropos, rendition of The Long Haul.

I was sure I wouldn’t miss my goal of posting in March.

I did.

I find myself increasingly befuddled by the relentlessness of digital immediacy—by the sense that online mediums urge a reactive pounce on matters of the day, or of the moment. As a slow writer with a talent for procrastination, I’m ill-suited to producing rapid-fire (or, let’s face it, brief) dispatches. But one of the payoffs of living where I do is the ongoing opportunity to note the rhythms of the world as it operates on biological and seasonal—even geological—rhythms.

And so, I remind myself, the Skyrocket will bloom, again. Next month, I’ll sow a garden, and it will grow then fade then freeze, again. As long as I’m paying attention, I’ll notice details and begin to trace connections. I’ll be inspired or confounded or upset or delighted and sometimes I’ll muster the discipline and patience to attempt a translation of sensation and emotion into language arranged and presented for others’ eyes. After a long hiatus, I’m settling back in to my office—now cluttered with decades’ worth of books and papers, no longer bare and echoey—and coaching myself not to fret overmuch about how often the writing completes itself. The notion of the long haul has hovered at the periphery of my awareness for months, and it’s finally time to contemplate what it really means.

The house in summer, ’03.

May 29, 2022

Fire and Ice

The thing about the world as we’re coming to know it now—a world in the process of changing at timescales we can perceive from the relatively puny span of a human adulthood—isn’t just that extremes pile up.

No, the thing is that these extremes cozy up to one another in bizarre and frankly disturbing ways.

The entire winter was too warm here in central Colorado—other than when it was too cold. Spring has also been too warm (and occasionally too cold). Dry, too. Way too dry. And windy. Have I mentioned the wind?

On days when those winds surged up from the south, they carried a haze of smoke from fires across the Southwest, including the large, persistent, and wholly depressing blazes in our neighbor state of New Mexico.

On May 12, I texted my husband a picture looking northeast from our deck, saying simply, “And so it begins.” A smoke plume had erupted on High Park, a flat that stretches between our place and Pikes Peak. As the fire spread that afternoon, pushed eastward by whipping winds, the southern front broke over a low rise, revealing an orange frill of flame at the base of the billow of smoke. Through binoculars, I could see those flames torching individual trees—at which point I stopped looking through binoculars.

So it begins.

In the next morning’s calmer air, High Park was submerged under a placid white sea: a pool of woodsmoke that had settled over thousands of acres. A few hours later, the sea had evaporated under stirring winds. Lazy whisps rose from the fire zone, marking different sites at the perimeter of the previous day’s burn. As windspeeds rose in early afternoon, the whisps coalesced into a fresh plume as the fire found its footing and began to run again.

Checking local newscasts, “on the scene” reporters spoke earnestly into their microphones; held at a distance by road closures, they gestured at anonymous smears of smoke in the background. I couldn’t help but think: they should be here. We have grandstand seats.

We’ve been in this position before, tracking the erratic travels of a wildfire from the high perch of our property. The emotions these events provoke are hard to categorize; I feel eyewitness intimacy, even though I’m removed by distance and the fortunes of wind direction. Watching the progress of the High Park fire, I felt the usual mix of relief and anxiety: no, this wasn’t going to be “our” fire—but the entire region was parched, and my world seemed poised to spontaneously combust. Meanwhile, the wind continued to rampage like a mean drunk, looking for any stray ember to pick a fight with.

Under these conditions, we did what we always do. We reviewed what take and where to go in an evacuation—although we realized we need an alternate place for horses in case the route southward was closed. We discussed the circumstances under which we might stay to defend the house. We talked through projects that would further harden house and barn against wildfire: mowing (again), more tree-thinning and low-limbing, get up on the roof and check the screening over the vents, skirt the back decks with tight-mesh metal screens to prevent embers from blowing under them.

Despite the lack of immediate danger, the sense of imminent hazard was all-encompassing. This is what fire weather does: it puts me on edge and keeps me suspended there. The wind, which is usually aggravating, feels overtly threatening. I become distractable, constantly walking to windows or stepping outside, scanning the horizon for smoke and sniffing the air. Work projects stall. When I heard one expert recommending moving livestock onto dry lots or overgrazed pastures during Red Flag conditions, I barked something that was a mix of expletive and derisive snort: the drought has been so bad here that we have nothing but overgrazed pastures.

The fire burned on, blowing up some days, making a run here and there, glowing on a couple of nights like a perverse mile-wide campfire. In the calm of early mornings, it was settled to scattered smolders. When the wind kicked up in the afternoons, I’d start watching for smoke billowing from a blow-up, and would usually see it. On occasion, the smoke trailed back and forth like sea grass riding the tide as the wind shifted directions.

May 19 brought yet another Red Flag Warning, meaning high winds, high temperatures, and low humidity. The next day’s forecast, however, showed a Winter Weather Advisory, with potential for heavy snow. The eighth day of the fire, May 20, dawned gloomy, but the gray sky was due to low clouds rather than smoke haze. By the end of the day, it had drizzled enough to deposit almost a tenth of an inch of water in the rain gauge: our first measurable precipitation in 24 days, during what would normally have been some of the wetter weeks of the year.

The next morning, I sank a yardstick in the smooth cushion of snow on the back deck and measured 21 inches, with heavy snow still falling. At the end of the day, I recorded 1.73 inches of water in the gauge. Flipping through my weather logs, I have to go back to August 2016 before I find a comparable single day accumulation.

We live in an arid region, at high altitude. The weather, by default, is harsh or fickle or dramatic, and sometimes it’s all three all at once. Heavy snow in May isn’t typical, but it’s hardly unprecedented. Around this time twenty-two years ago, we were bailing out the foundation of the cabin we’d just started building. A late-season blizzard had dumped four feet of snow; as it melted, water collected inside the concrete stem walls like the world’s most ill-conceived swimming pool.

Part of making our home here has always been figuring out ways to be prepared in the event we’re cut off. In the face of consecutive drama, though—fire one day, ice the next—I was rattled. How do we prepare to run yet also be ready to hunker down?

Snowcone on the bird bath.

Maybe, in the end, the logistics are the same: get organized, pay attention. But the mental part is tricky. This latest weather whipsaw left me wrung out. Usually on a snowy day, Doug or I will build a fire. We’ll settle down in the living room, basking in the coziness of warmth and togetherness. Last week, neither one of us was in the mood. We hung out in the living room, but the fireplace stayed cold. We let the furnace, its flames unseen, do the work of warming the house.

A week later, the terrific dump of snow has melted. The ground was too dry to tolerate mud: the water simply vanished into parched soil. The moisture has brought a surge of greening grass, though, springing up practically as I watch. It’s already tall enough to shiver under the wind of today’s Red Flag warning.

April 21, 2022

Contemplating the Beaufort Scale

The question of how to live with the wind is answered with bitter resignation and gritted teeth. How to talk about the wind—without cursing—has different answers.

Cast of coyote track imprints, left after the surrounding snow was blown away.

I’ve been a volunteer observer for the National Weather Service for more than fifteen years now. My duties involve recording temperature and precipitation data; wind isn’t part of the daily assignment, unless it rises to the standard of “damaging,” in which case I have a checkbox. But since the wind is a regular if not persistent presence here, I’ve started noting “wind” in the comment section of my data sheets on days when its presence is demonstrably annoying. That bland remark becomes less than informative when it occurs repeatedly, so I sometimes mix things up with “wind, again” or “high winds.”

There’s a better method, although I haven’t used it. Sir Francis Beaufort originally developed the wind scale that bears his name in 1805. Beaufort was a British naval officer, and he developed the scale in his private log, ranking wind conditions for their effects on the set of his ship’s sails. His wasn’t the first wind chart; in a fact sheet on the subject, Britain’s National Meteorological Library and Archive notes that people no doubt began classifying wind and weather as soon as they started venturing out to sea. Daniel Defoe recorded a “table of degrees” in 1703, consisting of what he described as “bald terms used by our sailors.”

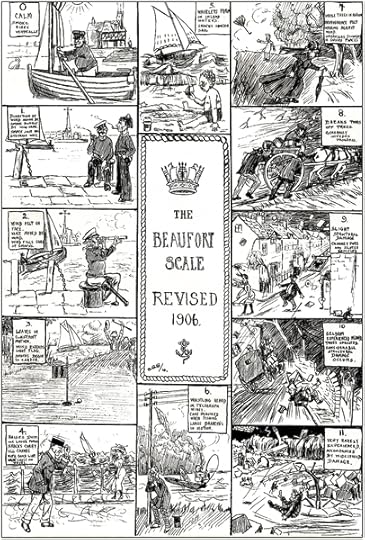

Beaufort aimed for uniformity over “bald terms,” using and refining his scheme throughout his seagoing career. In 1831, while serving as Hydrographer of the Navy, he commissioned the voyage of the HMS Beagle (of Darwin fame), during which the scale was first officially used. Seven years later, the British Admiralty commanded that Beaufort’s Wind Scale be used in the logbooks of Royal ships. As steam engines began to replace sails, its calibrations were matched to the appearance of wind effects on the sea; wave heights and wind speeds in knots (eventually converted into miles per hour for landlubbers) came later. A chart of land-based effects was added in 1906 by a fellow named George Simpson, who also created a helpful illustration.

Image retrieved from publiclab.org.

The Beaufort Wind Scale pairs standardized terminology with the simple empiricism of observation. Committing to shared terms means one person’s “Light Air” or “Fresh Breeze” is meant to be roughly the same as anyone else’s. Since the wind affects water and trees in consistent ways, calibrating Force levels according to those external phenomena tempers subjectivity. Yet perception is the Beaufort’s mechanism: there are no tools to purchase or maintain. The scale operates according to the quality of users’ attention to their surroundings. An anemometer might be numerically precise, but “leaves rustle” and “whistling in wires” and “resistance felt walking” have the consequence of embodied detail.

So, if I admire the scale, why not use it? It’s not like I just found out about it: the hard copy I printed off the Internet but then filed away is dated February 7, 2014.

Having spent some time over the past few days researching the Beaufort’s history and thinking about how it works and why it’s lasted, I’ve located two points of resistance. The first has to do with taking the time to learn the terms and linking them to the proper phenomena. In other words, I don’t use the Beaufort Scale because I’m too lazy to learn it. The second reason has to do with the very thing that makes the device so enduringly useful: the standardized classifications.

I’m sorry, but describing a Force 6 wind as a “Strong Breeze” just doesn’t cut it. The wind outside at this very moment is running 25 mph plus, and I can assure you there is nothing breezy about it. To characterize conditions that set the pine trees desperately waving their many arms and the power lines moaning as a “Breeze,” strong or otherwise, crosses a line from dry British understatement to sarcasm. Force 7’s “Near Gale” gets closer to reality: Now we’re talkin’ wind. The difference of wind velocity between Force 6 and Force 7 is but a few miles per hour, but the linguistic jump between Strong Breeze and Near Gale makes no sense to me. For sailors on a ship running with the wind, I suppose the sensation of a Force 6 blow might feel breezy. When you’re landlocked, though, and facing into it with an armload of fast-dissipating hay, other words come to mind.

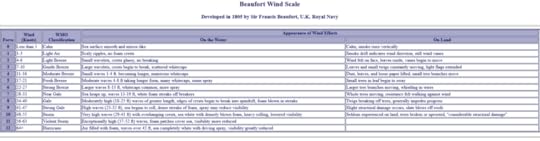

The version of the scale I’ve had in my files since 2014, from the noaa.gov Storm Prediction Center.

The scale was originally conceived to account for sustained winds on the open ocean, so maybe my high-altitude expectations are pushing the limits of its flexibility. Here in the central Rocky Mountains, the wind is often sustained, but mountainous terrain pushes it into variable and gusty behavior, with effects unevenly distributed. Our winds zither down ridges and roar over buttes; they whoosh through drainages and swirl into bowls. At the barn, which is sited in a sheltered depression, I feel the gentle fingers of a Force 2 on my face while the ponderosa pines uphill sway in the white-noise rush of a Force 4.

Such mismatches aside, I like how the Beaufort Scale invites me to contemplate the wind, not just resent it. I might wish it away, but that won’t do me any good. And what is the absence of wind, anyway? Stagnation. The ominous calm before the proverbial storm. Staleness. Calm air isn’t that common, but it’s also not a baseline condition. Force 0 on the Beaufort is one extreme on a relative scale, matched at the far end by Force 12: “Hurricane.”

More than anything else, it’s the scale’s fealty to local conditions that keeps me coming back. I think about how I would build another column, one for wind effects in mountainous terrain. Force 3, in that case, might be the stirring of air that cools a summer evening. Force 10 would be the overnight tempest that rolls the neighbor’s buck and rail fence.

Or how about a version calibrated by sound? Force 1 would be specified by the faint papery rustle of tall grass barely moving. A Force 2 blowing out of the east would be signaled by the fart-like brrrrtt of a car crossing the cattle guard on the paved road a couple miles away; if out of the west, that wind would bring us the barking of an unknown dog at an unspecified house off the gravel county road. We live among evergreen trees, and as the wind gets stronger, I would have to calculate how the psithurism of air flowing through pine needles at increasing speeds shrinks the aural neighborhood. By Force 7, though, all but the loudest outdoor noises would be drowned out by the roar in the trees.

There’s definitely room to expand the Beaufort Scale to include the interplay of wind and snow. Sculptural effects begin to occur at Force 3, I’d say, and snowment—drifted snow packed hard enough for a horse to walk on—forms around a Force 8.

Filling in snow effects is an exercise better suited to a winter day. For now, in April 2022, we are mired in “breezes” of various levels. By my count, there have been four days so far this month when the wind has not kicked up above at least 20 mph. Even though the temperatures are rising into the mid-50s, I’m still wearing my knit winter hat when I go out. It gets overwarm at times, but the wind doesn’t snatch it off my head. It stops my hair from thrashing my eyeballs and keeps the worst of the cursed wind—or is that my cursing of the wind?—out of my ears.

The buck and rail fence up the road a ways, which was rolled by the wind–twice–before the owners staked it down with rebar and installed outriggers (that log on the ground sticking out to either side of the cross-rail support).

March 25, 2022

Looking Out

That annual autumnal vow to make good on the dark months by focusing on writing has worn itself out.

Restlessness starts winning over office-bound convictions this time of year. The stuff that most needs doing is inside at my desk, but my attention refuses to stay in the room. Some part of me wants to be outside, even when there’s no good reason to be out there. The vernal equinox pendulated in on gloom and snow and wind, and three days into “spring” what’s left is that last one: wind. Icy gusts from the north rattle the house, put the horses in an entirely justified snit, and tear veils of snow off the mountains. It’s nasty out. Better to be in, sheltered.

Sticky spring snow.

The windows offer a semblance of compromise, framing glimpses of out there without the bitter conditions. As I have for weeks now, I catch myself paused at the glass. I keep thinking about what might be said on the theme of looking out, but the words don’t come.

Actually, that’s not right. Words come, but they circle pointlessly, reminding me of the bits of windblown hay that fall into the sink and get swirled down the drain after I brush my hair.

Images present themselves, however, and for a few weeks I mark time with pictures taken from inside looking out. Unfocused inquietude isn’t unusual for me this time of year, as winter tilts slowly into spring. But eventually I realize what’s gnawing at me about looking out is the sense of cloistered safety. This feeling of irresolution isn’t something between the weather and me, it’s something between the world and me.

Peeping Buck.

This sensation emerges at times of crisis, which is to say it’s been near-constant these past few years, with periodic surges of intensity. In more ordinary times, I’m perfectly at peace with my place here, on this wind-rolled ridge in Colorado’s central Rockies. When Big Picture trouble erupts, though, my position of remove makes me more uneasy rather than less so. In the face of a catalog of woes—war in Ukraine; a December wildfire…or was that an urban firestorm?…outside of my former home town of Boulder; one million dead from COVID; news that Antarctic fall and Arctic spring have been ushered in with extreme high temperatures at either pole during the week of the equinox—it is impossible to rationalize away how spoiled I am.

Snow etched by grass.

In the end, such a listing only numbs the misery, piling chaos on disaster over tragedy and running them through with anxiety to create a meaningless jumble. A bit conceited, too, maybe, adopting the world’s problems as my own.

Back at a window, I pout. In relation to the big calamities, I might be distanced, but I’m not immune.

That’s the emotional core.

But I’m stuck on the logistical pivot, the capacity for action. I’m handicapped by my status as a puny human, one of billions sharing the planet just now. I can look out through the windows of news and media and see what’s happening to people far from the familiar landscapes of home. There are limits to what I can do, though, and what seems possible or appropriate doesn’t add up to substance. In the face of ongoing upheaval, writing a check to a worthy cause feels urgent but hardly adequate. I believe in the idea that small acts multiply, but the sum effects aren’t visible from the hall window.

I think about the groups of people I’ve read about in Ukraine, meeting an invading army by gathering in basements to weave camouflage tarps from fabric scraps and fishing nets.

In times like these, I’d like to think words count as action. I might be fooling myself, merely taking what is, for me, the easy way out. I’m not convinced, entirely, that weaving the scraps of my thoughts onto the sheltering net that is this place is what most needs doing, but I turn away from the window, and get back to doing it.

Early bluebird.

January 26, 2022

Out of Time

I suppose it’s the usual, this dropping the thread and vanishing from blog life for weeks…okay, months…at a time. Usual for me, anyway.

It isn’t that I don’t think about posts, or topics for them. I do. Regularly, in fact. But I lack whatever instinct it is that compels the killing pounce, that impulse to not only take the idea down as soon as it’s spotted but tear into it, spill its vital little organs across a page in bloody black and white.

I have, it seems, embraced an identity as a ssllllooooowwww writer rather too enthusiastically—or at least more wholeheartedly than is suitable for the fast-paced world of on-line “content,” designed to appear quickly and fade away at the pace of a gentle scroll. I flatter myself, perhaps, that what I’m aiming for falls into the genre of brief essay rather than drive-by clickbait, but even so. Ideas that fly up like a bright flare fade by the time I’ve arrived ready to catch them with full attention. By then, I see their time-sensitive attributes, and inevitably it seems their time has passed.

So it’s gone for months now.

Without an early killing frost, the garden had a nice run last fall. I took to photographing each harvest, anticipating it might be the last. But the weather stayed fine and the pictures accumulated. Which basket of goods to feature?

The garden did eventually freeze, rendering that idea old news. But I left the carrots in the ground as long as I dared. Such pretty carrots in 2021.

The sun then set on that idea, too, but by then the fall saffron crocus were blooming. I am a sucker for that lavender color. And such delicate flowers at the season’s end, after everything else has faded to brown.

And so ephemeral, gone so fast.

But I had pulled up the tomato plants before they froze, hanging them upside-down in the greenhouse so the immature fruits could slowly ripen despite their small size. They did, and I harvested fresh tomatoes right through to Thanksgiving.

We ate them all, happily, and by then it was December. Shouldn’t I be contemplating the season of cold and rest, not yapping on about garden produce, still? Then again, it’s been so dry and warm, droughty, and I am weary of ominous news and incessant downers.

Although the too-mild weather was good for getting outside.

Visiting with Jake, who only wanted to steal Doug’s hat.

Then it snowed—not much, but some—and the temperatures slumped to a suitably January chill: the reassurance of a season still beholden to ancient rhythms as we ride the old earth, teetering as we swing around the sun. The moon overhead, meanwhile, kept its own time, waning to dark, waxing full, rolling into a new year.

I tally anniversaries—twenty years since we moved here to Cap Rock, thirty since Doug’s life wrapped itself around mine. I cannot decide if I am time-sensitive or out of time, perpetually late or finally present. Is it joy or helplessness I feel, whirling through the sunrises and sunsets of each new day?

October 22, 2021

Last Call

As fall color, the caution-yellow flowers of rabbitbrush tend to flare early. They bloomed here, this year, weeks before the aspen or the scrub oak got around to changing. As a wildflower, though, rabbitbrush blooms late, which is why plantswoman Lauren Springer Ogden refers to it as the “last bar open”: a destination where insects gather for one final slug of nectar before the season shuts down (my thanks to Susan J. Tweit for the reference).

Both rubber and Douglas rabbitbrush thrive in this area. The latter is smaller and easily identified by its twisted leaves. The larger rubber, or gray, rabbitbrush (Chrysothamnus nauseosis) is also known in Spanish as chamisa. The plants are considered undesirable by ranchers, but they’re browsed by deer, rabbits, and pronghorn, and the seeds are a food source for overwintering birds. Native tribes used branches from the plants in tanning hides and as coverings for sweat lodges, and boiled the flowers for yellow dye. Given that accounts I’ve read say that the flower clusters have to be boiled for six hours, making the dye bath over an open fire would have been an enormous commitment. Modern weavers and fiber artists still use yarns tinted with chamisa.

There’s a magnificent gray rabbitbrush sprawling at the southwest corner of our septic field. It took root in this fortuitous spot not long after the area was excavated, so it’s no more than 19 years old. I feel safe in surmising that its roots have found the leach field, since the plant has grown to over five feet high in that time—a whopper for this altitude. This particular shrub is far wider than it is tall, its branching crooked, crazy, and fractured from mule deer bucks rubbing their antlers on the tough and woody stems—some of which are now as thick as small trees.

In late September, I went out with the camera on a sunny morning, late enough that the crisp chill of fall had burned off under a crystalline sky. I was still in my bathrobe, but the nectar bar was in full swing. For thirty minutes I stood at that one plant, watching, listening to the hum and buzz, and taking pictures. It was the busiest gathering I’ve attended in years.

If you’re entomologically inclined, or just want to break out the field guide and practice identification, please feel free to put names to any of these barflys (haha, yes, I know most of them aren’t flies…but a couple of them are) in the comments. I’ve numbered the photos so we all can keep track.

1

2

3 Anybody else see a white comma marking on the wing?

4

5

6

7 Correct me if I’m wrong: male checkered skipper?

8 Correct me if I’m wrong: female checkered skipper?

9

10

11

12

13

14 clouded sulfur (left) and ??

15

16 Okay, that’s not an insect, but even the western salsify seed wants to hang with the rabbitbrush.