Neil Cocker's Blog

September 23, 2023

Ten Things I’ve Learned in Ten Years of Self-Publishing

Pokémon and Kangaroo inspect a delivery

Pokémon and Kangaroo inspect a deliveryTen years ago, I took the decision to self-publish my novel Amsterdam Rampant.

I’d come close to getting a publishing deal twice, but both times fell short at the final hurdle. The publishers were full of praise, but there was always a but: your novel isn’t commercial enough; it doesn’t fit neatly into a genre; it’s a man’s book and men don’t buy books.

The whole experience made me fall out of love with writing for a couple of years. I decided to focus on my day job and started a part-time MBA. Learning about product development and marketing got me thinking differently about my writing. My fellow students talked wistfully about one day starting their own enterprise and getting a product to market. I already had a product. Why was I relying on others to take it to market?

Self-publishing felt like the obvious thing to do. I decided I was going to have fun doing it, and not only that, I decided I would blog about the experience with brutal honesty every step of the way…

In this post I’m going to look back and share what I’ve learned in the last ten years. I hope it will be of interest if you are thinking of self-publishing, if you’re curious how the publishing industry has changed in the last decade, or if you’re interested in the evolution of self-publishing technology in the digital age.

Let’s dive in…

Self-publishing was absolutely the right decision. But it wasn’t an easy decision at the time. As you can see from my first ever blog post, I was beaten up and bloodied and worried about the stigma. But after losing my love for writing I knew I needed to get my mojo back, and it felt like the right way out.

It was. While my experiences in the traditional publishing industry mostly involved waiting, and then going in circles in small steps, and then more waiting, with self-publishing I was learning something new every day. Whether it was learning about book formatting, cover design, digital marketing, publishing trends, or Amazon analytics, being in charge of the experience always meant motion and momentum rather than paralysis – moving forward instead of standing still.

The quality gap between traditional publishing and indie publishing has narrowed and continues to narrow. The perception of self-published novels as substandard still lingers, but it’s changing slowly. Two things have happened. Firstly, indie authors have learned lots in the last ten years and the quality of indie has increased considerably. Take a look at Amazon’s Storyteller competition – all of those books are self-published by indie authors, many of whom run their own one-person business writing, publishing and marketing their series of novels. Many make it into the top 20 bestseller charts. Secondly, the quality of novels published by traditional houses has generally declined in the last ten years. Money is draining out the industry, and the roster of proofreaders, copyeditors, marketers etc has shrunk considerably since I started knocking on their doors twenty years ago. I buy fiction books in ebook format and I’m often shocked by the poor quality of formatting from the big hitters.

Paper beats digital for hearts and minds. A quick experiment – do you, like me, often look at your IKEA Billy bookshelves and wonder what you’ll do with all those CDs and DVDs? But probably not the books. These days most of us consume movies and boxsets via streaming platforms, and music through Spotify or similar. But printed books remain a resilient format. Blockbuster and HMV have disappeared from high streets but bookshops – despite a rough few years competing with Amazon – are sticking around. The paper book is an object that we remain highly emotionally attached to.

Ebooks drive volume, print books make it real. Ebooks still tend to be divisive – every six months or so The Guardian runs an article about how ebooks are in decline and plucky print is winning the battle. The truth is more complex and layered. The different formats are consumed for different reasons and (very importantly) operate at different price points. Readers are happy to take a chance on an ebook for 99 pence/cents in a way they wouldn’t for a paperback at 14.99. My impression is that many readers will read their guilty pleasures on ebook, and if they start to love an author they will switch to print (or own both). Physical bookcases are increasingly ‘curated’ and becoming more about Instagram and TikTok. A Kindle library can hold thousands of books without the reader having to worry about building a new wing to their house.

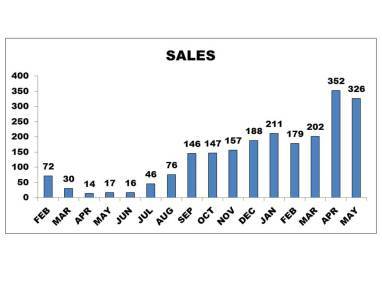

For me, I focused on ebook for the first eight years of my self-publishing journey. The price point directly affected volume – if I sold Amsterdam Rampant for 99 pence/cents I could sometimes shift 400+ in a month. If I increased to 2.99, then volume would typically drop by around three-quarters. The ebook format helped me build readership and reviews in a way that print-only wouldn’t have.

When I published my second novel The Devil’s Chamber I decided to also create a paperback and hardcover version, and after doing this decided to do the same for Amsterdam Rampant. The technology is pretty amazing – in traditional publishing the minimum print run is often 500 or more, meaning that a publisher has to make a call on expected sales and also where to store the stock. With print-on-demand technology, you can order one single copy. This large photocopier-like machine will then print and bind the book in around 5-20 minutes depending on the number of pages.

I completely underestimated the emotional impact of the print book – holding it in my hand and feeling its weight. Surprisingly it was the same for people I know – when I gave them a copy they often looked at it in wonder, at me in disbelief, turned it over in their hands, ran their thumb over the pages. People finally believe you’re a writer in a way they don’t from ebooks. The print book is the most powerful marketing tool at your disposal.

So while I make 99% of my sales in ebook, I keep a supply of my printed books at home and give away free copies to people who show an interest. I also like to occasionally drop them off in pop-up libraries or leave them in pubs. It’s fun to get them out in the universe and let people discover them by chance.

Amazon’s self-publishing platforms are revolutionary – but clunky. The journey from ready manuscript to published book in the traditional industry typically takes around two years. On Amazon’s Kindle Direct Publishing platform, an ebook can be published in hours and a print book can be delivered to your home in days. It’s a liberating and thrilling experience, deciding “OK, I’m finally happy with this” and then working through a series of webforms before finally clicking the PUBLISH button. It’s deceptive though – you can’t cut corners. It’s not just the manuscript; you need high quality artwork, blurb for the book description and your author page, a sense of how you want the book to look and feel whether digital or on paper. The KDP print platform is quite difficult to navigate, and even when your book looks good in the online preview, when you order that first paperback you can get a nasty surprise when the finished product arrives. It took me four attempts to get the artwork and margins and gutter correct despite what the online preview showed. So you have to be ready for hard work – you will lose evenings, weekends, holidays.

Amazon’s algorithm is becoming ruthlessly efficient. It’s difficult to get exact figures as Amazon is notoriously defensive about its publishing data, but my quick googling suggested that in 2014, there were 2 million ebooks available through Amazon, and in 2023 that figure had reached 12 million. Back in 2014 I spent next to nothing on Amazon marketing and managed to build up good sales for Amsterdam Rampant, peaking at around 400 books per month. I got lucky with the algorithm – readers of Scottish writers Irvine Welsh and John Niven started to buy my book and in turn it got recommended to other readers in the ‘Customers Also Bought’ sliders and a virtuous circle built momentum. My impression is that Amazon was still working things out back then. Now they seriously know how to monetise ebooks.

When I launched The Devil’s Chamber in 2021, it was much harder to get random sales. But once I started to run marketing campaigns, sales steadily rose. The way it works is that you bid for clicks – so for example, my most successful campaigns have focused on the category ‘literary fiction.’ If someone searches for that category then the highest bidding authors or publishing houses will see their novel appear on the first page of recommended reads. Depending on your bid settings, a campaign will typically cost €100-300 in a month. If I didn’t run a campaign in the early days I might only sell 20 books in a month. When I ran a campaign, this number jumped to around 120. And I had to run a few campaigns for The Devil’s Chamber to get that same feeling of momentum I had with Amsterdam Rampant. Basically, it feels like you now have to pay Amazon to feed the machine and turn the wheels, whereas in the early days of Kindle it was enough to customise your book details smartly to get hits in the search engine. Like any data-based model, the algorithm gets more powerful the more products and customers and history there is, so in the coming years a sizeable marketing budget may be essential to get any kind of visibility on Amazon. Which leads to the next point…

All writers need to be marketers now. The most successful indie authors are professional multi-taskers, not only writing quality novels (usually a series) but also highly impressive brand managers. Based on my unscientific observations on Twitter, many traditionally published writers complain about the amount of marketing they have to do – “I’m an artist, not a marketing manager” seems to be the common complaint. This begs the question – why pay so much of your royalties to the gatekeepers if they are not marketing and selling your book? The main reason is probably because…

Indie remains invisible. This is perhaps the most disappointing lack of development in the last ten years. Indie film and music are seen as innovative and cutting edge – away from the mainstream, changing the paradigm, a punky view into the future of the medium. But in fiction, the gatekeepers do their utmost to prevent self-published works from getting credibility (you will never see a self-published novel reviewed in any mainstream newspaper or literary magazine). Self-publishing has gained credibility in the last decade but is ultimately still seen as ‘less.’

The publishing industry is stratifying into three layers. Layer one: big publishing houses need chunky sales to thrive and survive, so they take few risks. They look for talent from creative writing courses and from within their own circles. When they find a winning formula they stick with it, but their two-year time-to-market means that by the time their billionaire bondage / teenage vampire novels hit the shops the fad has passed and they are behind the curve. They are too fossilised to keep up with BookTok. Layer two: the small presses are often run from someone’s kitchen by a small passionate team. They publish books because they love them rather than because the marketing department thinks it’s a big demographic. At one end of the spectrum they publish innovative writers, are creative in the look and feel of their books, and genuinely shake up the publishing scene (see this article about Bluemoose for a fine example). At the other end of the spectrum, they are overly localised, have a confusing list mixing fiction with books on hiking and fishing, and are overly loyal to their small and dusty community of creatives (ancient websites and twee cover art are often an obvious sign of this). Layer three: indie/self-publishing. At one end of the spectrum, successful indie writers who have the creative freedom to follow their vision, make far more money than they would with a publisher, trailblaze new genres and change the industry from the bottom up. At the other end of the spectrum, it’s a Wild West of clip-art covers, AI-generated scams, and deranged over-promotion of books with no substance.

The problem with the layers is that they are in danger of becoming stand-alone echo chambers with no interaction between the three. The traditional industry has its incestuous inner circle interlinked with establishment media and prize committees; the small presses plug in to the niches and zines, the open mic nights and the leftfield; the indie community is mainly online and tribal and turns its back on the traditional scene with a spartan fervour.

In my day job I work in the startup world and the idea of the ‘ecosystem’ is a popular one – an environment in which all the players/layers in that world interact with each other and thrive from this interaction. It’s possible to envisage the publishing world moving slowly towards such an ecosystem, although unlikely given the cutthroat commercials involved. What could this look like? Here are some ideas…

Self-publishing/indie would largely remain the same – a Darwinian world in which poor quality sinks without a trace and high quality gets noticed, bought, imitated. Amazon would develop a stable of labels – their own themed publishing houses that would select the most successful indie writers for multi-book contracts and push sales using their own marketing leverage.

Meanwhile, big publishers would improve their supply chain and reduce their time-to-market. Much like in the world of football/soccer in recent years, big houses would move their talent scouting process away from a relationship-based one to a mixed model that also looked at data to discover high potential writers (e.g. sales and ranking on Amazon, using AI to monitor popularity of pieces in online lit magazines, scanning sales on multiple platforms in countries all around the world to scout for writers for translation). This would help them find talent in a more meritocratic way and compete with Amazon for successful indie writers. By working with a variety of printing models they could also better compete with Amazon (rather than committing to huge print runs with long lead times).

The small presses are already doing a lot of things right. The ones that do really well such as Bluemoose tend to have a very clear strategy and/or purpose. To continue the football analogy, in the English Premier League smaller clubs such as Brighton and Brentford have thrived despite their smaller budgets. They’ve done so by having a very clear culture and focus at all levels of the club, and have been innovative in how they find and cultivate players (e.g. picking up players rejected at an early age by bigger clubs for being too small, scouting in countries the bigger clubs tend to overlook, etc). Likewise small presses could break their addiction to their local scene and either go all in on the hiking books or choose to specialise in a particular type of fiction, then scout the dropouts from traditional publishing scene and the indie breakouts.

Maybe some of this is already happening (perhaps I’m trapped in the indie echo chamber). Maybe it’s just wishful thinking.

The future for writers is hybrid. Until such a time as an ecosystem model develops, I personally believe writers will shift to hybrid publishing as standard. By this I mean that writers will develop a ‘horses for courses’ mentality depending on what they intend to publish. So let’s imagine an established writer with a back catalogue of five novels. Three have fallen out of print, and the writer has found a small press to print one of them. The writer decides to renew her relationship with her existing big publishing house for her other two novels and her new forthcoming one. But she has also written a 70-page novella, a passion project, that the big house isn’t interested in. Who reads novellas? they tell her. So she decides that she will self-publish the novella and promote it via her newsletter. Over time she also self-publishes the two older novels that are out of print. She eventually ends up with a hybrid portfolio of work that gives her deeper insights into the industry and her bargaining power, and also helps her balance the level of risk across three different publishing methodologies and understand the pros and cons of each. If one fails, she has backup options.

Ten years on, I am really pleased with my self-publishing experiences. From a writer’s point of view, having full creative control of my work – from first draft to fully realised novels reviewed and liked by readers – has been immensely satisfying. From a business perspective, I had two products I believed in, launched them to the market, and they sold.

However, as I get closer to finishing my third novel Dirty Old Europe, I am curious about a hybrid approach. The subject matter would benefit from a more knowledgeable third party to guide it into the hands of the readers who will love it. I’m being a little cryptic but will tell you all more when the time is right. And if it doesn’t work out with a big publishing house or a small press, well, I have a great Plan B

If you’re interested in finding out more about my novels you can visit my Amazon author’s page here.

You can browse my blogs about self-publishing in the panel on the right – they go all the way back to 2013. And just get in touch if you would like to discuss or debate my dribblings

January 23, 2021

The Devil is Coming

The devil is coming.

My new novel ‘The Devil’s Chamber’ will be published in February. Here’s the blurb, and if you’re brave enough, the first chapter…

Miro McGarrity has built a successful life in Singapore, trying to forget the Scotland of his youth. But one afternoon he receives the news he has dreaded for twenty years – an email that takes him back to Edinburgh in 1999 and his first job in a sprawling council archive.

Over the course of a few weeks in that long-lost autumn, Miro fell under the spell of two urban explorers seeking a legendary underground room known as the Devil’s Chamber. This fragile alliance would lead him into the forgotten corners of the archives, into grungy pubs and derelict buildings, until finally, in the shadows under the city, they discovered the shocking truth behind the legend.

Now, after two decades of running away, Miro must return to the Devil’s Chamber to face his fate – but there might be one last chance of a way out…

*

Do you want to know more?

Then come closer.

Sit here, where I can see you.

Have a beer – no, I insist. You’ll need it.

No, you can’t have a glass. Just drink from the bottle. What do you think this is, an ambassador’s reception?

[rolls eyes. sighs.]

Sorry, but I’ve been trapped with this story for four years, and now it’s burning to get out there.

Comfortable? Then I’ll begin.

*

PROLOGUE: SINGAPORE, 2019

The fire alarm wails – its pulsing siren is a needle in my brain.

Around me in the open-plan office, colleagues stand up, grumbling and stretching, grabbing their wallets and phones. This will mean all of us trooping down twelve flights of stairs and stepping out into the courtyard in the blistering Singapore sun, waiting while the appointed ones with clipboards tick us off their lists. But just as abruptly as it began, the alarm shuts off, and for a second I still hear its echo, feel that spike pushing through my eardrum.

“Just a test,” someone says. The Singaporeans return to their desks quietly but from a few of the foreigners muttered swearwords are audible.

When I turn back to my screen, I see the email drop into my inbox. I only see the sender name and title but it’s enough.

I vomit chilli crab onto my desk.

A hubbub explodes around me: shocked cries, a gasp, and a hooting laugh that can only be the Aussie IT guy. I feel another heave building in my guts so I run to the bathroom.

I get in a cubicle just in time to throw up second helpings. After a few more retches I spit out the last strands and slowly get my breath back, forearms resting on the toilet seat, staring down at the puddle of pink soup.

A knock on the door. “Miro? Are you OK?”

The voice sounds like Warren Chang, one of the data analysts.

“Miro? Do you need help?”

“It’s OK, I just need a few minutes.”

“I already called the cleaner, Miro. We are worried about you.”

The big boss puking on his desk. This is great for my career, if I still have a career or any kind of future on this planet. I’m aware of my iPhone awkwardly pressing into my thigh, and realise I can read the email here in case there are any more bodily explosions.

The bathroom door flops shut and I listen for any other signs of life. None.

I unlock the cubicle door and at the sink I wash my face and my forearms and hands. I’m not ready to read the email yet. My mouth still has the acidic tang of bile and I need some water, and a mint.

In the mirror my eyes are red. I don’t want to read this email cowering in a toilet cubicle. I want to read it in the open, with a coffee and a view. Die with my boots on. I scrape a fleck of sick off my shirt collar with my fingernail, check again for any other spray-back, and then head out into the office.

The cleaner’s trolley is parked by my desk and a few heads turn in my direction. I walk past reception to the other side of the office, see that the coffee area is mercifully empty, and grab an espresso and a bottle of water. The boardroom was booked for my meeting with the CEO of Malaysia’s second largest snack company but he cancelled this morning so this is someplace I can go to be alone. I step into its air-conditioned silence and drag one of the chairs over to the window.

Twelve floors below, Singapore bustles. In the business district the skyscrapers wall the streets in, snaring the traffic in one-way loops. Pedestrians move in shoals along the narrow pavements, clutching umbrellas and takeaway lattes.

I down the espresso. Combined with adrenaline, the caffeine glow amps up my heart so that I can feel its techno-beat high in my chest. I take a slug of water, and another, washing away the puke taste. It is time to read the email.

I take out my iPhone, and there it is at the top of my inbox.

The sender: Neve Pinkerton

And the title, neatly summarising the thing that has kept me awake on hundreds of nights and kept me running around the world, always one step ahead of my biggest fear.

The title.

They Found Us

November 11, 2018

Into the Wilds

[image error]

So, I released my new novel The Devil’s Chamber into the wilds last weekend.

In my younger days I mainly used writers’ groups as a source of feedback on novels-in-progress. It was really useful for a number of reasons. First, you get used to taking tough feedback and developing the scar tissue that goes with it. Second, you understand the difference between constructive feedback and crap feedback (I once sat in an Amsterdam group arguing with an American guy for 5 minutes about my use of the word ‘pitch’ to describe a football field, which he maintained would cause American readers to throw the book out of the window in exasperation; I got my revenge the following week when he used the phrase “the unmistakable stink of elephant dung” and I pointed out that most readers had, unlike him, no deep knowledge of the different aromas of animal faeces).

I stepped away from writers’ groups once I grew weary of the storm of voices, and also decided to trust my own instincts more.

So for the latest novel I sent the draft off to my three beta readers. The Wikipedia definition of beta reader is somewhat unflattering, suggesting that the individual is “a test reader of an unreleased work of literature or other writing (similar to beta testing in software) who gives feedback from the point of view of an average reader to the author.”

My beta readers are far from average. I think of them more as a league of superheroes.

First up is my fellow Scot Sean, who I’ve never actually spoken to other than on Skype, but I feel like I know him like an old mate. We first “met” on the comments string of a Scottish Literature article on the Guardian way back in 2006 and have since exchanged thousands of words of feedback on each other’s novels, along the way exploring and debating the big themes of Scottish literature, the epic storytelling universe of The Wire, the calamitous impact of misplaced commas, and the likely end of the world. Sean’s superpower is his line editing, an uncanny ability to remove words and strip flabby writing down to its fighting weight.

Second up is Mat, a Londoner I met at a writers’ group in Amsterdam way back in 2002. We immediately bonded over the awfulness of the group, and rebelled by setting up our own regular writing head-to-head over curry and beers which ran for the duration of my seven years in the Netherlands. He became a great friend as well as a writing buddy. His superpower is his eye for a story, his feel for character, and his humour.

Last but not least is Jeremy, an award-winning screenwriter who lives near London and adapted Amsterdam Rampant into a screenplay. I’ve learned loads from this Leeds lad in the year or so we’ve known each other. He described Amsterdam Rampant as ‘Trainspotting meets In Bruges’ which was the coolest thing anyone could ever say about it, as this was pretty much my objective all along. From Jeremy I learned the art of boiling a story down to its essence, the gun-to-the-head sacrifice of non-essential plotlines, and the relentless demand for entertainment from TV and cinema.

It’s an interesting exercise to canvas independent views on the same body of work, because when you get the same feedback more than once you know you have to act on it. You also get quite different views based on everybody’s inbuilt preferences for the types of books they like to read and the TV shows they like to watch. This is one of the reasons I started with Jeremy, Mat, and Sean – although I have several more writer friends whose views I trust and value, I decided to kick it off with these three because I know we have very similar tastes. I have a hunch they will give me advice on the type of story it should be, which is what I’m looking for at this stage. For the next wave of beta readers I will look for people with more diverse tastes who are likely to call out unexpected glitches and flaws, and also make suggestions that make me think more closely about what should and shouldn’t be included.

So my beta readers will be already wandering the new world of my novel, exploring its landscape, observing the characters like invisible ghosts. Scribbling notes. Hopefully smiling and nodding rather than tutting and shaking their heads.

Am I apprehensive about the beta readers’ feedback? Actually, unlike previous novels, it all feels quite liberating. It’s maybe a bit like kids leaving home – the first one leaves you with empty nest syndrome and niggling fears, but by the third one you’re relaxed and want them to go out into the world and find their own path. Over the many years I wrote The Vodka Angels (which I never published) I wasted countless hours trying to write something that would be Capital-L Literature. I re-wrote multiple versions of Amsterdam Rampant to get the setting and pace just right. This time with The Devil’s Chamber, I decided I want to keep the story simple and punchy, and get the novel out there quickly (not compromising on my own standards but not re-reading and re-writing each line obsessively for years either).

So here I am, sitting in a train station waiting-room with my main characters. There’s a large clock on the wall, its thudding tick resounding in the dusty stillness, and some of the people I have conjured into life shift nervously around me. One or two of them may have to leave; others may have a second chance, or a new destiny. A whistle blows in the distance and we sit in silence, waiting on news from the gods.

Photo: Jan Cocker

August 19, 2018

A NEW NOVEL ON THE HORIZON

[image error]

Hemingway famously said: “First drafts are shit.” I’m prone to agree. In June I finished the first draft of my new novel, provisionally titled ‘’The Devil’s Chamber’’. I started writing it in New York in November 2016 and since then I’ve been chipping away, writing only at the weekends, a stolen couple of hours on Saturday mornings or Sunday evenings until finally I crossed the finishing line.

After clicking save I left my raw novel to distill for a few weeks in my hard drive, a little worried about it, then when on holiday in July I uncorked it and downed it in one.

I was surprised. While it needs still more work, it actually holds together pretty well. I scrolled through it sitting on the veranda of an AirBnB bungalow in the South of France, some weird unseen creature screeching from the tree above, everything around me – cheering French football fans, chirrup of crickets, stifling humidity – out of sync with the setting of the novel – dark, rainy, booze-soaked Edinburgh in the 90s. But as I read, I was there on those wet streets and in those basement pubs with my main character, wandering this newly created world.

Having the headspace to reflect on a draft is new to me. In the past I wrote and edited and re-read on the go, which on reflection created many problems. You can’t strategise on the battlefield when you’re crouched in a foxhole counting bullets with trembling hands. There are still things I need to fix with this novel – a couple of holes in the roof – but the overall structure is there. It’s the first time I’ve written a first draft with a clear beginning, middle, and end. This might sound crazy, to embark on an epic writing project with no concept of what’s going to happen at the end other than a vague hunch, but in my experience that’s how most writers build a novel. You can have a strong mental picture of what the finished book will look and feel like, but the process of piecing it together is as hard to plan as falling in love. In fact, just like looking for love, when you stop planning it, that’s usually when the magic happens.

So I have a decent chunk of novel, what now?

The second draft excites me, because it’s about returning to characters and picking them up again, feeling around their barnacled shells for tiny apertures and prising them open to reveal hidden pearls. It’s about finding the plot holes, the howlers, the continuity errors. Pinpointing a small detail that adds richness, maybe opens up new avenues entirely. Slowly stitching it all together, getting the language right, turning words into music, making the dialogue spark, transmuting throwaway scenes into rough gold.

No pressure.

I’m hoping that the second draft will be ready in a few months, by which stage I will be able to kick off the publication process. To get ready, I’ve been re-reading my first blogs from almost five years ago and reflecting on everything that happened since.

In my first ever blog in October 2013, I wrote about entering Phase 4 of my writing life: self-publishing. I was still a bit bloodied and beaten up from the traditional publishing industry, nervous about leaping into the dark. Going through those blogs again I’m glad to look back and say that it was undoubtedly the right decision for me.

When I set out on the epublishing journey I mainly just wanted to prove the industry wrong after so many rejections. My main goal was to sell one thousand ebooks in the first year, but also to get the fun back, which had been missing for a long time. I blogged about it quite a lot, so I won’t rattle on about it, but I cracked the first thousand sales only after about ten months and then experienced all sorts of unexpected stuff.

I’ve now sold more than 5,000 ebooks of Amsterdam Rampant. I covered my costs (mainly the cover artwork) after about ten months. I’ve got 198 reviews on my main platform Amazon UK, averaging 4.4 stars. For Goodreads it’s 273 ratings, averaging 3.79 stars.

After around eighteen months, Amsterdam Rampant got picked up by fans of Scottish writers Irvine Welsh (mainly after the publication of his novel A Decent Ride) and John Niven, and started to appear in the ‘also bought’ sliders on their Amazon pages. This had a far more powerful impact on my sales than any paid-for advertising. Much like those ‘also bought’ sliders, a solid body of verified reviews really helped boost sales. And then it started to tip – readers see your book linked to other books they’ve read and enjoyed, they see you have dozens of genuine reviews, and they see a modest price (it’s been £2.99 for the last three years or so). They bought, reviewed, recommended.

When this critical mass builds up, weird things happen. In the pre-digital age, you published your novel in print, maybe sold a few hundred copies, then waited for any sort of engagement from readers. Did you get letters? Who knows. Since epublishing, I’ve had maybe 80-100 direct personal messages from readers. Sometimes it’s old friends or former colleagues, but most often just random punters who felt some connection with Amsterdam Rampant. This was one of the experiences that meant the most to me, getting back from work and finding a message from someone who’s taken time out of their busy day to say they loved your novel. They didn’t have to do it, but they tracked me down, and wrote a little personal note with words to say they’d laughed a lot or had been entertained or it had reminded them of their friends when they were younger. It gets you a bit emotional. The industry experts told me things like “I can’t see who would buy it”, “the topic isn’t appealing enough to the market”, “men don’t read books”, “there’s nothing in it for women.” Perhaps it’s all true statistically, but what’s also true is that there are people – men and women – who are buying it, and most importantly reading it.

I even got a very surprising message unrelated to the novel from a distant relative. I wrote a blog about my obsession with my family history and a couple of stories in particular, one of which was the death of my great-great-grandfather William McAldin in a mining accident in Nova Scotia and all of the unknowns. A distant cousin called Tam got in touch after my blog popped up on his search engine. After twenty-five years of trying to fully understand the mystery of William’s disappearance from the family tree, it was all there in one email, and it was a heartbreaker.

But the most amazing thing that happened was this. In June 2017, completely out of the blue, the award-winning screenwriter Jeremy Saul Taylor contacted me to say that he loved Amsterdam Rampant – “Trainspotting meets In Bruges” – and would like to adapt it into a screenplay. It’s been a great experience, in part because I wrote the book with a movie playing in my head. Over Skype calls and WhatsApp messages we bounced ideas around, then Jeremy stripped the novel back to its bones and rebuilt the story block-by-block. One plotline has disappeared completely, new scenes take the story in new directions, and the ending is different. Jeremy did a great job. In many ways I prefer the remix (now called Amoeba) to the original. Three versions later, the screenplay is out there, doing the rounds.

So it’s been quite a ride, this self-publishing lark. And I’m going to do it all again with The Devil’s Chamber.

Tune in for more news soon…

January 29, 2017

New York, City of Dreams

[image error]

In November, sitting at the breakfast bar on the 12th floor of a New York hotel, I started writing fiction again.

It’s the first time in more than five years I’ve written anything new – the fact that I can’t remember exactly when I stopped is somewhat shocking, considering I spent the previous twenty years writing almost every day. I knew it would take something unusual to get me started again, and no advice or encouragement from others would make a difference. The internet is awash with smug articles on how to overcome writer’s block, generate writing ideas, and craft them into shape, but frankly I think any attempt to explain this mysterious process is nonsense – writing-by-numbers just produces copies of copies, a hall of mirrors where every reflection is dimmer than the last.

Over the last few years I’ve nurtured four ideas for novels, a bit like those dragons’ eggs in Game of Thrones, dormant ideas lugged around, part-burden part-treasure, just waiting to be plunged into fire.

So why did I start writing again? What started the inferno?

The spark was New York itself. Last November, my wife started a 5-week work secondment in the city and I joined her for two and a half weeks. The timing of the trip couldn’t have been better, as I had just finished my MBA studies –four years of weekends spent with my nose in textbooks, and writing assignments – and suddenly I had the free time and headspace to go back to my second love (the first one of course being my wife – an insurance in case Anna is reading this).

New York swept me up into its crazy energy almost immediately. Anna had a couple of free days before starting work, and that first long weekend we mapped out the city’s matrix of streets on foot, dislocated by jetlag, surprised at every turn by the familiar and the alien. The Empire State, the Chrysler, Broadway’s brash trashy canyon. Central Park surprised us with its smalltown calmness. Ripped open blue skies framed the skyscrapers, gentle autumn sunshine illuminated the streets. We walked over Brooklyn Bridge at sunset, Manhattan blazing with light, the Hudson metallic and oozing sludgily below. Our hotel in a quiet section of Midtown East was a refuge from the crowds and honking sirens, and the days began with eggs and pancakes at the nearby diner, and were bookended with a quiet table at the local Thai restaurant or at Blackwells Irish pub. Those early days were a palate-cleanser – a brain-cleanser – wiping my mind clean of the grey Europe I’d left behind.

Once Anna started work, so did I.

It has happened before that a new place frees me up to write properly about another place, gives me the perspective to understand an object in the distance. And so it was with New York – the Big Idea was suddenly liberated, unleashed. I wrote two thousand words that first morning in the aparthotel, the peak of the Chrysler building visible from where I was sitting.

It helped that the city had a feeling of being under siege by the forces of history. The Trump v Clinton election build-up dominated every overheard conversation, every TV screen. And after the election itself, there was a sense that New York wasn’t just new to us, but to every single person in the city – everyone’s world turned upside down by the result, everyone suddenly an alien in a new America. The novel I’m now writing features a main character whose world has been capsized by the death of a loved one, so some of the chaos and disorder and grief I saw on the streets of Manhattan bled into the writing.

The Big Idea took shape in the grid of streets, in museums and Irish pubs. I alternated between writing and taking notes, mapping out the architecture of the new novel. One afternoon I sat in PJ Moran’s under a portrait of Brendan Behan, frantically keying the plan into my iPhone. The next day I was in the research room at the New York Public Library, typing away in the reverent silence. That must be my most beautiful post-writing walk ever, going down those grand stairs and out onto 5th Avenue just as dusk was settling.

[image error]

And so a pattern was established: write something every day, or at least scribble notes, and always walk the streets and work it through in my head. Sometimes New York got too deep into my headspace, and it helped that I had a soundtrack for the new novel – the music of King Creosote helped take my imagination back to the east of Scotland, to the gentle thunder of the North Sea and the wet streets of Edinburgh.

And so I wrote, then walked, then walked some more. I had forgotten that feeling of embarking on a novel, where the direct – writing it – is complimented by the indirect – thinking about it, and having experiences that contribute to it in some unknown way.

I carried my Kindle with me on those long walks, and in the moments when I needed to rest my aching feet (most often in an Irish pub with a decent IPA selection) I read Tyler Anbinder’s City Of Dreams: The 400 Year Epic History of Immigration into New York. It’s a brilliant book, and encouraged me to make the trip to Ellis Island, which was an absolute wonder. I was there for four hours and could have easily have stayed for twelve. Set against the backdrop of Trump’s election days before, visiting the tiny island that welcomed eleven million immigrants was nothing short of astonishing. Equally unsettling was the fact that a quick search of their database threw up five Cockers from Aberdeenshire – knowing how unusual my surname is (thankfully for humankind) the fact that five from my ancestors’ county, no doubt all related to me in some distant way, had been through the island hit home the massive scale of emigration to the US around the turn of the twentieth century. Something of this also leaked into my writing in the days that followed, into the main character’s displacement and relocation to a new city.

[image error]

I now have fourteen thousand words of the new novel – generally I’m a slow writer – but the world of the novel exists, and the characters that inhabit it are now alive. I don’t like to talk about projects when they are in progress but I don’t mind allowing you a glimpse. The Big Idea is about a young grief-stricken archivist who starts work in the mid-90s at a forgotten Edinburgh basement archive. One day he stumbles across a document that seems to suggest an old folk tale is in fact true – and by pursuing his interest, he uncovers an even bigger secret.

On my final day, sitting in the lounge at JFK, I really didn’t want to leave. Not only was it the best break I’d had in years, New York had unscrewed my head, rebooted my writing brain, and screwed my head back on again. New York pushed me in an unexpected direction and gave me a map of the way forward, a way to lead the idea into the light, and now every time I click save and shut down my laptop, I nod a quiet thanks to the city of dreams.

February 28, 2016

Mainland: Submissions Wanted

In an age of fevered tabloid paranoia, it is easy to forget that migration is a two-way street. More than two million British and Irish nationals live and work in mainland Europe and contribute to the rich diversity of a continent that has been a warzone for much of the past 2,000 years, but since the European project began has experienced a 70-year miracle of relative peace. With the UK In-Out referendum on the horizon in June 2016, this anthology of writing by British and Irish nationals living in mainland Europe is a timely reminder of the precious diversity and shared liberty of the European continent, and a celebration of its complex togetherness.

Submission guidelines:

Short stories, novel extracts, non-fiction of no more than 4,000 words

Submissions should ideally be written by British or Irish nationals living on mainland Europe (but much like the Schengen agreement, we maintain an open border policy, eg. If you are a native English speaker who has lived on mainland Europe at some point, or just passed through and have an incredible story to tell, then you may just pass the test).

All writing should be set in or about mainland Europe, which is loosely defined as the EU member state countries, and should ideally be about native English speakers interacting with people, cultures, history, food and alcoholic beverages within the mainland zone

Submission deadline is 15 April 2016, publication planned in May 2016

Proceeds will be donated to Care International, a charity supporting people who have been impoverished by war and conflict (with a particular focus on improving the rights of women and girls). No payment will be made to contributing authors but the editor promises to market the hell out of their work. The editor will cover all costs of publication.

Submit to neilcocker@hotmail.com

December 6, 2015

All Humbling Darkness

Back in the days when people got letters, it was the most exciting letter I’d ever had.

February 1993, I’m guessing. The letter announced that the University of Aberdeen’s Department of English had appointed the writer William McIlvanney as a creative writing tutor, and a course would be starting soon with limited availability, and if students wished to attend they should register as soon as possible, in person, at the Department of English (which in fact did everything it could to deconstruct the word ‘English’ – Scottish, Irish, and American literature held pride of place on the syllabus alongside the tolerated classics).

That morning, overcome with nerves that I might miss the opportunity, I power-walked up to King’s College and after a few minutes of excruciating lingering outside the administrative office, got my name down. I was dizzy with excitement for the rest of the day. It was an act that would change the course of my life.

Three years previously, at the age of seventeen, I had discovered McIlvanney. His novel Docherty distilled the early Scottish 20th-century through the experience of one family – mass Irish immigration, slum life, the First World War and its terrible toll, the grim tyranny of the mining industry, the scramble for a shred of dignity. It was a story that belonged to all of us and I was smitten.

At the first class I was so nervous I could barely speak. This was nothing new, however – it was a common problem for most of the Scottish state school students. At our exemplary government schools we had been taught how to read, how to learn, how to write, how to recite poetry – but not how to compete with confident others (especially those who had been privately schooled). But this class was different. McIlvanney talked to us like equals, gave us photocopies of brief snippets of literature, challenged us to decipher the code. He connected with us lost kids, the children of Scotland’s first ever socially mobile generation, and encouraged us to express our opinions and make our voices heard.

As I recall the course lasted for 8 weeks – 16 hours of my life – yet he taught me lasting lessons not only about literature but about communication and connecting with other people. I still distinctly remember several of those classes. There was one writing exercise where we started with an answering machine message – from a pompous Professor Clifford – and each of us scripted a message which by small increments destroyed the Professor’s life (mine was a scratchy recording from a pub phone of a mob of students drunkenly singing “Professor Clifford, Professor Clifford, you’re a horse’s arse.” Not exactly creative but my new favourite teacher laughed like a drain).

There was a stunning lesson which introduced me to the poetry of Dylan Thomas. McIlvanney read us ‘The Refusal to Mourn, The Death By Fire, of a Child in London.’ It was astonishing stuff – perplexing yet beautiful snippets like “all humbling darkness”, “Zion of the Water Bead”, “Secret by the unmourning water.” Willie led us on a deconstruction and interrogation line by line, but not in the rote manner I’d experienced so far during my degree – this was the work of a master craftsman, taking the engine apart piece by gleaming piece, gently polishing each component and then reassembling the poem to reveal the incredible precision of the inexplicable whole.

And there was the moment that inspired me to dedicate years of my life to writing. A week after we submitted our first assignments, he asked me to stay back after the class. We spent half an hour together, just me and my hero. He took me through my short story, pointing out the strengths and the weaknesses, nudging me in new directions. I still have those faded sheets of lined A4 with his scribbled notes.

Last night, after driving back to Luxembourg from Frankfurt, I opened the Guardian homepage and saw the news that Willie had died.

Over the last twenty years the magnitude and impact of his writing had finally found worldwide recognition. He had been acknowledged in recent years for creating an entire genre – Tartan Noir, or Scottish Crime Writing for the uninitiated – but this is an inaccurate legacy (despite the undisputed excellence of his Laidlaw novels) because his ‘other’ writing was even better. For me, McIlvanney tells the story of our parents and grandparents in a way that no other writer of his generation did. In his writing, heavy industry always melded with the glamour of cinema – the local and the global smelted together in a messy and unresolvable compound. In much the same way, he welded high literature to the everyday – he once described the Scots language as ‘English in its underpants.’ Even after thirteen years away from Scotland I still use words like ‘dreich’ (grim, rainy, drippy weather), ‘whersht’ (a sourness that makes you pucker your face) and ‘glaikit’ (a stupidity that is visible on the vacant face of the owner). McIlvanney celebrated the richness of our abandoned language and integrated it seamlessly with the grand dialect of Shakespeare.

This morning I sit in front of my laptop and think about what he bequeathed to us. There are the novels, the short stories, the poems, the essays, the TV appearances, his teaching. But McIlvanney’s legacy is much bigger than this. He was one of a kind but at the same time an everyman of his generation. He told the story of his ancestors in a way that resonated with all of us – of how community spirit could overcome sectarianism, poverty, and war. His writing mapped the previous Scottish century and predicted the direction of the current one.

In the final class twenty-two years ago we read some of our work and drank wine. McIlvanney’s son Liam (now an acclaimed writer himself) was there. Afterwards we went to The Machar, the campus pub, and I remember reluctantly leaving the throng, rushing out into the spring twilight to go to my dishwashing job, my feet pounding the pavement in the hope that the walk would diminish my drunkenness. It didn’t. I clanged around in the kitchen, intoxicated not just on wine and beer but on the thrill of learning and changing and understanding the universe a bit better.

When a favourite teacher dies, a chunk of you dies too. RIP Willie – thanks for teaching us, inspiring us, entertaining us. You taught us how to look into the all humbling darkness and see a spark of light.

June 7, 2015

Just like Cold Sores and Coldplay

It’s been a long time. A health problem knocked me out of action for a couple of months, but now I’m back on track to making a full recovery. Just like cold sores and Coldplay, I’m difficult to get rid of…

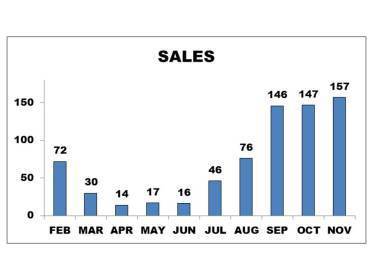

Despite doing absolutely zip to promote Amsterdam Rampant, sales have grown considerably since February:

I’ve now sold more than 2.2k. It took me 11 months to sell one thousand and then 3 months to sell the next thousand. What happened? Well, luckily I seem to be attracting Irvine Welsh fans, and the release of his new novel A Decent Ride led to a definite bounce in sales. If you check out A Decent Ride on Amazon you will see Amsterdam Rampant snugly parked at second place in the “also bought” listing. But hey, I hear you say, maybe Amsterdam Rampant fans are buying Irvine Welsh’s work? Too right, dudes and dudettes. I’m still waiting for the thank you telegram from Irv.

I’ve also seen a big spike in reviews on Amazon UK. Over the first year I accumulated around 45 reviews, and now three months into the second I’ve got more than 90. This is probably a combination of the increased sales and the addition of a ‘Dear Reader’ note at the end of the novel asking (pleading!) for reviews. People have been very generous with their feedback – common themes are the book’s high pace, the familiar characters, the Amsterdam setting, the humour and the dialogue.

The whole review thing got me thinking about opinion, with a capital O. I’m so grateful for the recent 4 and 5 star reviews that I could almost cry (for a Scottish male this mainly involves a Spock-like grimace). I get up in the morning and check first thing, and there I am, sitting in rural Luxembourg eating my blackcurrant jam on toast, getting all Spock-like because some random punter has given me the Full Five with a gushing commentary. Oddly, the rare one or two star reviews don’t really bother me, because it’s clear the subject matter isn’t for them (although you have to ask the question – what were you expecting from the title, cover, and synopsis – the novelisation of the Vicar of Dibley?)

The 3-star reviews are the most unpredictable. They include one of my favourites:

“I enjoyed this novel but felt parts of it were under-developed: the relationship between Fin and Gilly had more to be said about it and the plot development with Eva’s betrayal didn’t quite ring true. Yet there were sections which we brilliantly written and which reminded me of early Iain Banks. Don’t imagine the Amsterdam Tourist Board will endorse this but it was a good read from a writer whose work I’d read again.”

… and also a confusing and puzzling one, from someone who probably knows me (part of my younger life was spent in Fife) and is vaguely unsettling as a result…

“This is an amusing little Scottish modern diaspora tale. School bullies, sexual experiences of both the willing and less so make up the backbone, set against a rather poorly illustrated Amsterdam. Not sure what a previous reviewer meant by ‘phonetic Scots’ as rendering the language subtlety maybe incomprehensible. The book reads to me as if written by a Fifer. No in Welsh’s league – ye ken whit I mean ya bam?”

It’s interesting to compare the opinion of the punters with that of the publishers my agent pitched the novel to back in 2010-11. Bear in mind that the comments below date from previous versions of Amsterdam Rampant (when it was called Distillery Boys) and when it still needed a good edit, but I think it demonstrates the wide range of opinion that one novel can generate, and also what is foremost in the mind of the average editor/publisher:

SIMON & SCHUSTER: Thank you so much for sending DISTILLERY BOYS, who as you know shared it with me. We both enjoyed it – Neil Cocker has a vivid and entertaining style and a wicked sense of humour too. Looking at our publishing schedule, though, we weren’t entirely sure how best to position it on our list and couldn’t help feel that it might not have a wide enough appeal to female readers. So we have decided to pass, but we’re very grateful to have read and hope you find the perfect home for it elsewhere.

HEADLINE: In any case, I have read DISTILLERY BOYS and enjoyed it very much – Neil is an instantly engaging writer, and the journey he takes us on is very readable (I did feel a little nervous, reading this one on the tube, but had to keep going, nonetheless), though I did feel there was perhaps something a touch strained in all the playfulness – as though he was perhaps trying a little too hard to underscore his point about the nature of our consumer society. I also wasn’t really sure that the whisky theme was an appealing enough hook. So I’m afraid it’s a no from me, this time, though I do think he is a writer with potential. Thanks again for letting me have the chance to read this.

PICADOR: I enjoyed this but didn’t quite feel it was quite right for Picador. I would love to find a new young male voice for Picador but I think this was just on the lad side of lit for me.

HARPER COLLINS: I am so sorry not to have come back to you sooner on Distillery Boys. I thoroughly enjoyed reading it — there is a real strength in the central narrative voice, and an originality in the way Neil uses language, particularly dialogue. He also writes very engagingly when describing dramatic scenes. My concern is that the story is a bit limiting in terms of its commercial appeal, as I didn’t find the branding work that interesting (certainly less interesting than all the sexual encounters!). So I’m going to pass this time, but thank you for thinking of me. I hope you get a massive offer from this other editor!

HODDER: Thank you very much for sending me DISTILLERY BOYS. I’m afraid I’m going to pass, though it’s hard to say exactly why since it’s such a good debut novel. It had me laughing out loud one moment and cringing the next! However, while it’s very well done, I must admit that I have a few doubts about the commercial appeal of DISTILLERY BOYS to a wide audience (it’s quite male in appeal for a start, which can be limiting). As you know, we have to be wholeheartedly behind every book that we take on, and I’m afraid that I just didn’t quite feel that measure of enthusiasm about DISTILLERY BOYS to warrant making it a priority above some of my other commitments. But many thanks again for sending it to me, I’m very glad I had a chance to read it, and I hope you find a home for it very soon.

ATLANTIC: Many thanks for sending me DISTILLERY BOYS by Neil Cocker and for being so patient! I thought the opening was brilliant and I love the quick-paced, edge-of-the-seat style and dark humour. However, as the novel progressed I found myself feeling less, rather than more, involved with the characters and so I think I’m going to have to pass. I’m sorry as I really thought I might be able to take this further and hope that someone else feels differently to me.

HEINEMANN: Many thanks for giving me the opportunity to consider Neil Cocker’s DISTILLERY BOYS. I read it with much interest, but in the end I’m afraid I wasn’t convinced that it would was suitable for the William Heinemann list. I thought the premise was very good, and it’s engaging and exuberantly told, but I’m sorry to say I didn’t like it quite enough. Sorry.

WEIDENFELD: I hope it’s not rude to reply so quickly but I dived into DISTILLERY BOYS (the Hornby/Nicholls pitch got me!) and I’m afraid I just can’t see us making it work. There were some wonderful moments in the writing, and I think the author has real comic talent – I can’t stress that enough. But the novel as a whole didn’t gel as much as I had hoped – it was as though the caper elements were fighting with the more tender aspects instead of going hand-in-hand. And it would be difficult for us to find a place for this book – it’s too charming to work as enfant terrible fiction but, to my mind at least, the emotional pull of the central characters wasn’t quite strong enough for it to captivate the Nicholls/Hornby audience. But thank you for such an entertaining read, and I’d love to have a book with you soon!

CAPE: This is not for me, alas. Fun, but with not quite enough substance…

POLYGON/BIRLINN: OK, it’s not the one. I’m sorry but my misogyny detector went into overdrive only a few paragraphs in. I really don’t like the style of this one, I’m afraid, or Vodka Angels [my previous novel] which I remember. A colleague who also read it is itching to send a copy of the Scum Manifesto to Luxembourg! So, not for us.

Publishers seem to me to always be gambling on what the zeitgeist is, waiting for other publishers to make the first move before committing to anything. In the 4-5 years since I received these comments, thrillers such as ‘Gone Girl’ have made mainstream publishers more open to darker and explicit material, so ironically Amsterdam Rampant might be more interesting to them nowadays. But you can see from the above that the quality or entertainment factor came secondary in their thought processes to the commercial possibilities (which anyway is mainly guesswork judging by the perilous financial state of many publishing houses nowadays).

Reflecting on all this feedback just reminds me once again that self-publishing was the right option for me, because it answered the question of who I am writing for. I imagine the person I am writing for completely differently nowadays – not an editor looking out onto a London skyline, but rather someone who downloads the ebook of Amsterdam Rampant on impulse one night, and then reads it on the train to work, transported away from the grind of the commute to the backstreets of Amsterdam and the rain-washed hills of rural Scotland. I imagine that person reaching the final page and smiling to themselves, their life made a fraction better by my book. The train squeaks to a halt; they realise it’s their stop, slap their Kindle shut and dash off the train; I see them from the window moving along the platform with a bounce in their step and a glimmer of mischief in their eye, before they merge into the crowds and disappear from view.

January 24, 2015

Breaking the Thousand

I did it!

On 13 January I sold my 1,000th ebook of Amsterdam Rampant, breaking the target I set at the outset of my epublishing project.�� On 8 February I will reach the one-year anniversary of publication by which time (at current run rate) I will hopefully have sold more than 1,100.�� December sales were strong and momentum continues to build in January, averaging slightly more than 6 ebooks per day…

I���m even appearing pretty high up on Irvine Welsh���s ���also bought��� Amazon profile for Trainspotting prequel Skagboys which is one of my highlights of the century so far:

Over Christmas and New Year we had our usual epic trip around Europe to see family.�� My wife Anna had gone on ahead, and I followed a week later.�� These trips are intensely nostalgia-inducing for me, because I have the rare chance away from work and study to read books, look out of the window on long journeys, and generally think about things.�� Dangerous, really.

The journey to Poland started with an early morning bus ride out of Luxembourg.�� It was just getting light when I reached the German steel town of Saarbrucken, the sprawling rust-red plant ��� a tangle of pipes, towers, and gargantuan machinery ��� looming at the side of the autobahn like some nightmare from a surrealist painting.

I jumped the train to Mannheim, and connected for Berlin.�� On those long hours coasting through Germany I ploughed through Eleanor Catton���s The Luminaries ��� occasionally looking out the window onto Germany, then returning to 19th century New Zealand on my Kindle.�� It was around five o���clock by the time I reached Berlin, and I killed time before the next connection walking round the station and then sinking a cold glass of Berliner pilsner in a plastic and chrome wurst bar.�� The final two hours of the journey were spent on a local train on the spooky fringes of eastern Germany, the train windows revealing little of the poorly lit train stations and shadowy villages.�� Finally my 12-hour journey came to an end and I reached Anna���s home town of Szczecin.

Szczecin has always fascinated me.�� Before World War II it was part of Germany and known as Stettin.�� In the closing months of the war most of the German population fled westwards away from the advancing Red Army.�� The ghost city was then resettled with Polish refugees, mainly from Vilnius in modern day Lithuania or Lviv in modern day Ukraine.

Anna���s grandparents were from Lviv and upon arrival in 1945, the city was still in chaos ��� much of it was rubble, and the corpses of German soldiers were piled in one of the city���s main squares, awaiting disposal.�� The family were allocated an apartment in a grand tenement on one of the city���s grand Parisian-style boulevards.�� A few weeks after moving in a German woman turned up on the doorstep with her daughter and explained she used to live there, and would like to collect a doll they had left behind.

Szczecin still carries the scars of the war ��� swathes of Soviet-era concrete map out the routes of the British bombers, and most of the older buildings are pock-marked with bullet-holes and shrapnel damage.�� Yet the city carries its scars well ��� the economy is buzzing and there is a sense of energy and industry, reflected in the glittering ultra-modern malls and the SUVs backed-up at the traffic lights.�� A bizarre urban myth is doing the rounds, popular among taxi drivers, that the city is riddled with underground tunnels which reach all the way to Berlin, and when the Germans inevitably return they will emerge from below the ground and re-take the city.�� These taxi drivers watch too many zombie movies.�� Ironically the invasion seems to be happening peacefully the other way round ��� local Poles are buying property across the border in Germany because it���s cheaper.

One evening my mother-in-law, Agnieszka, showed me what she���d dug up in her garden.�� The family has had the same allotment since the early days of arriving in the city, a patchwork of gardens behind the train line which were initially allocated to Flemish railway workers in the late nineteenth century.�� Last year, Agnieszka was digging in the garden and uncovered a toy soldier and a coin.�� I examined the coin through a magnifying glass and could make out the word ���Stettiner��� on its time-worn surface.�� The toy soldier yielded more clues.�� We googled German army uniforms and saw that his tunic, belt, and helmet matched the standard First World War uniform.�� Agnieszka told me (through our usual mix of her few words of English, my few words of Polish, sign language and the ever-patient translation of Anna) that one time her father went to the allotment to find a large hole dug in the middle of the garden.�� The story went that the German residents had been instructed to only take one suitcase with them when they left, and had buried valuables wherever they could, and then returned years later in the dead of night to reclaim their heirlooms.�� The toy soldier and coin had perhaps been part of such a booty.

During my time in Szczecin I usually have a bit of time on my own when Anna catches up with her mum or with old friends.�� One afternoon I tramped past the city���s old gate down to the harbour area, wandered by the monument to the victims of the unrest of 1981, and ended up in a steakhouse/bar called Colorado.�� I sat by one of the windows looking out onto the port, candle flickering at my table, and sketched out some ideas for the next novel.�� Away from the pressure of work and study, my writer���s brain thaws from hibernation, and ideas tumble in.

Next up was Scotland.

We flew from Berlin to Edinburgh and spent a few days with my parents in North-East Fife.�� It was my first time back for a year, and as I get older Scotland���s beauty astonishes me more and more, catches me off guard and leaves me breathless.�� We walked the beach at St Andrews most days, the sun catching on the breakers, the hard-packed sand glistening with seawater and stretched shadows.

The view from my parents��� house looks onto Tentsmuir forest, which by bizarre co-incidence is where Anna���s great uncle most likely spent several months on training exercises with the Polish Free Army before jumping into Arnhem in 1944.�� Many of my schoolmates in Fife had Polish surnames, descendants of those exiled soldiers, the lucky survivors of Monte Cassino and the Netherlands campaigns.

Most evenings��in Fife we went up to the village pub to drink and chat to the locals.�� One night my dad told me a story I���d never heard before, about his time doing national service as a military policeman in Berlin in 1961-62.�� One night he was called out to an incident on the wall, and arrived with his partner in the immediate aftermath of a shooting of an attempted escapee.�� The young man���s body was crumpled in the space between the two zones; the East German guards were smoking, guns at ease, the deed done.�� My dad and his partner watched as they collected the body.

We moved on to Edinburgh to catch up with my brother and some old friends.�� One afternoon I had a spare hour and walked down the Royal Mile, past the old soldiers��� home where my great-grandfather, a London-Irishman by the name of Isaac Dunn, spent his final years.�� The clouds cleared as I strode down the hill, the hard blue sky and glaring winter sun spilling light onto the granite buildings.�� I walked down past the Scottish Parliament and felt a pang of regret that I had missed the referendum experience.�� Europe is, as always, disintegrating and reforming like a half-frozen loch.�� I walked back up Holyrood Road, past my old teacher training college, the nostalgia intensifying.

Later that night I wound up on the same street with my brother Ian in an old favourite pub, once the Holyrood Tavern and now Holyrood 9A.�� We sat at the bar and drank pale ale and reminisced about the late 90s when we���d been regulars.�� Back then it was a wonderfully odd boozer ��� dark wood and beaten-up old sofas, an amazing jukebox and excellent beer, and a clientele of old men, teacher training students, and transvestites.�� Somehow it worked.�� The kilted landlord had wild long greying hair and a goatee beard and would noisily chuck anyone out who told him he looked like Billy Connolly (he did).�� Our night ended at a takeaway, thick-cut chips drowned in salt and sauce, and the next morning I said farewell to Scotland.

Next was London.�� Anna wasn���t feeling too well so I had some Neil-time in the afternoons (in the evenings we explored the Thai restaurants of Holborn).�� Just like in Poland I put my Kindle in one jacket pocket and my Moleskine notebook in the other and headed off into the city to walk and observe.�� On the first day I wandered the bookshops of Charing Cross Road and ended up in a pub near Trafalgar Square called The Chandos, which I frequented back in the early 00s on visits to see old friends.�� Sitting in the corner of the pub, I read an ancient draft of my Lithuania novel (perhaps seventeen years old, then called Sea of Tranquillity) and sipped my pint of bitter; golden light dappled through the coloured glass windows, the raw and scrappy novel triggering all sorts of long-lost memories.

The next afternoon I headed in the other direction into Covent Garden, cut through the Seven Dials (where I spent a boozy day in 2002 with my Swedish pal Daniel, both of us at a crossroads in life and debating the meaning of it all) and wandered around the streets aimlessly, before settling in The Prince of Wales. ��The barmaid heard my accent and wanted to talk about Edinburgh; still high from being back in that city of dreams, I was happy to.�� I picked a corner table again and scribbled more notes on the next novel.�� I decided to go to one more pub before returning to the hotel but it was already close to five o���clock on a Friday, and the pubs were bursting at the seams with post-work drinkers.�� Eventually I found a quiet place near the hotel ��� The Dolphin Tavern, in a building which took a direct hit from a Zeppelin bomb in 1915.�� At that moment, nearing the end of my break, it seemed that our triangular journey had, as always, been stitched together by a shared European history of war and renewal, destruction and rebirth.�� At those moments, trying to make sense of a Scottish-British-Polish-Dutch-Luxembourgish-European experience, I tend to flounder, but marvel at the fact that we have had 70 years of peace in Europe.�� And agonise that it may not last much longer.

The first couple of weeks back in the host country is always tough.�� Luxembourg experiences hard grey winters, even more so than Scotland (at least the grey skies there blow over once in while).�� Even if you���re not an expat, the January blues bite deep, but as an emigrant there is a sense of dislocation and confusion, of waking up in the mornings and for the first thirty seconds not remembering where you are.�� Then gradually you remember the life you have built in the new country ��� work, friends, an altogether different view out the window.

And this year, I have something that makes me smile on those icy and dark January mornings ��� more than one thousand copies sold of Amsterdam Rampant, a book that prompted one publisher to tell me ���I just can���t see who would buy it.����� Well, my friend, one thousand people have bought it, and it���s only the beginning of the journey.

December 18, 2014

Seasonality’s Greetings

November was another good month for sales. Another skyscraper on the charts. My upstart city is growing fast…

Sales are tracking well in December too, at about 6 per day (current total sales since 8 February is 828 units) which at the current run rate means that by February I should hit the 1,000 target with a little to spare. Which is pretty amazing considering the lull in the spring.

Despite the promising sales so far in December, my Calvinist soul warns me of possible obstacles ahead. What does seasonality look like in the ebook world? Do people buy more or fewer ebooks over the Christmas season? I have no idea what to expect. Does anyone out there have any idea?