Gary Rex Tanner's Blog

December 2, 2014

Dear John

Several years ago my pal Mississippi Slim played a couple of my songs for a blues-rock artist named Corey Stevens. Corey was preparing to do an album “Blue Drops of Rain” and decided to include my song “Head Shrinker.”

“Corey says he loved the two songs I played for him and he thinks you could be his J.J. Cale,” said Slim

“Who’s J.J. Cale?” I replied.

“You know,” said Slim, “he’s the guy who wrote all those songs for Eric Clapton.”

“Who’s Eric Clapton?”

I started paying attention to some of the songs on the radio and figured out who Eric Clapton was. One day I saw an article in the local newspaper that said J.J. Cale had moved to North San Diego County. That’s where I live. So I looked him up on Google and read his discography and biography. I’d only heard one of his songs, not one that I particularly cared for (by Clapton)…not that I really cared for anything I’d heard from Clapton. But the article said that Cale was reclusive and guarded his privacy fiercely. That was cool with me; I’m of a similar bent. More interesting to me was that he came from the Tulsa area (via Oklahoma City), where my people come from and was only a year or so older than me. One day I picked up the plumbing business phone and a voice said:

“I need some hay-elp…I way-en’t over t’Home Dee-poe Saturday and bought this damn faucet fer mah kitchen sank and ah spent most of the weekind tryin’ to keep the damn thang frum leakin’. Ya reckon yew could send someone over and fix that damn thang?”

I’d heard that voice and that brogue my whole life and figured it was one of my kinfolks “actin’ afool.”

I started to come back with my version of that Okie brogue…bear in mind, I AM an Okie, which means my parents migrated to California during the great depression and I was born prior to WW II. As a rule I don’t speak like that, but it’s there ifn I need it. I decided to play it straight and said:

“Where are you located?”

“I’m over here by the Circle R Golf Course, about a mall from the I-15.”

Well, I couldn’t hit a house over there with a rock from my place, but it’s only a mile or two away as the crow flies.

“I’ve got a truck going right by there,” I said, “I could probably get him over there in less than a half hour.”

“Thee-in send ‘im over,” the voice said, “I’ll see ‘im when he gets here.”

“What’s your name?” I asked

“Kale,” the voice says.

“OK, what’s your address?”

He gave it to me.

“Your phone number?”

He gave it to me.

“Do you spell your last name with a ‘K’, or with a ‘C’? I asked

“With a ‘C’.”

“What’s the first name?”

“John.”

I looked at the paper on which I was writing this down for a moment. Then I remembered what I had read in the paper.

“Are you a song writer?” I asked.

“Uh…naw, not really…er…well not…

“Yes you are,” I interrupted forcefully; “You’re J.J. Cale, aren’t you?”

“Waaay-el…”

“Yeah, you’re J. J. Cale and I’ve got your address and phone number. I’ll be puttin’ it up there on the Internet and people are gonna be drivin’ by your house and callin’ you night and day from now on.”

Dead silence.

“Hey man…I’m just kiddin’…I’ll get someone over there in a half hour.”

Mr. Cale did not laugh, but my son Lucky fixed his plumbing and talked with him for an hour or two. I would have brief conversations with him several times over the next few years whenever he needed his plumbing serviced. I enjoyed his rich Oklahoma brogue as much as anything we talked about. We never discussed music. John wasn’t an Okie, at least not by my definition. I call people from Oklahoma, Oklahomans. They may sometimes speak like us Okies, which John did, but they’re, for the most part, from a different cultural experience. Saturday, when my wife Daisy and I were driving down the freeway to wherever we were going, I said:

“Daisy, I just thought of something. We should send a copy of my book, ‘The Oklahoma Gamblin’ Man,’ to John Cale. I mean, he’s from where all that stuff happened…he’d probably really enjoy reading it.”

“Yes, that’s a good idea; we have his mailing address in our files.”

“Daisy, check the Internet on your cell phone and see if there’s a decent movie on nearby. Maybe we could eat and go to a movie.”

Daisy complied.

“Oh my God!” Daisy exclaimed. “It says John Cale just died in La Jolla of a heart attack.”

So I guess I won’t be hearin’ that rich Oklahoma country brogue anymore…but I’m sure I’ll think about him once in awhile, like when it’s real quiet…like…After Midnight.

“Corey says he loved the two songs I played for him and he thinks you could be his J.J. Cale,” said Slim

“Who’s J.J. Cale?” I replied.

“You know,” said Slim, “he’s the guy who wrote all those songs for Eric Clapton.”

“Who’s Eric Clapton?”

I started paying attention to some of the songs on the radio and figured out who Eric Clapton was. One day I saw an article in the local newspaper that said J.J. Cale had moved to North San Diego County. That’s where I live. So I looked him up on Google and read his discography and biography. I’d only heard one of his songs, not one that I particularly cared for (by Clapton)…not that I really cared for anything I’d heard from Clapton. But the article said that Cale was reclusive and guarded his privacy fiercely. That was cool with me; I’m of a similar bent. More interesting to me was that he came from the Tulsa area (via Oklahoma City), where my people come from and was only a year or so older than me. One day I picked up the plumbing business phone and a voice said:

“I need some hay-elp…I way-en’t over t’Home Dee-poe Saturday and bought this damn faucet fer mah kitchen sank and ah spent most of the weekind tryin’ to keep the damn thang frum leakin’. Ya reckon yew could send someone over and fix that damn thang?”

I’d heard that voice and that brogue my whole life and figured it was one of my kinfolks “actin’ afool.”

I started to come back with my version of that Okie brogue…bear in mind, I AM an Okie, which means my parents migrated to California during the great depression and I was born prior to WW II. As a rule I don’t speak like that, but it’s there ifn I need it. I decided to play it straight and said:

“Where are you located?”

“I’m over here by the Circle R Golf Course, about a mall from the I-15.”

Well, I couldn’t hit a house over there with a rock from my place, but it’s only a mile or two away as the crow flies.

“I’ve got a truck going right by there,” I said, “I could probably get him over there in less than a half hour.”

“Thee-in send ‘im over,” the voice said, “I’ll see ‘im when he gets here.”

“What’s your name?” I asked

“Kale,” the voice says.

“OK, what’s your address?”

He gave it to me.

“Your phone number?”

He gave it to me.

“Do you spell your last name with a ‘K’, or with a ‘C’? I asked

“With a ‘C’.”

“What’s the first name?”

“John.”

I looked at the paper on which I was writing this down for a moment. Then I remembered what I had read in the paper.

“Are you a song writer?” I asked.

“Uh…naw, not really…er…well not…

“Yes you are,” I interrupted forcefully; “You’re J.J. Cale, aren’t you?”

“Waaay-el…”

“Yeah, you’re J. J. Cale and I’ve got your address and phone number. I’ll be puttin’ it up there on the Internet and people are gonna be drivin’ by your house and callin’ you night and day from now on.”

Dead silence.

“Hey man…I’m just kiddin’…I’ll get someone over there in a half hour.”

Mr. Cale did not laugh, but my son Lucky fixed his plumbing and talked with him for an hour or two. I would have brief conversations with him several times over the next few years whenever he needed his plumbing serviced. I enjoyed his rich Oklahoma brogue as much as anything we talked about. We never discussed music. John wasn’t an Okie, at least not by my definition. I call people from Oklahoma, Oklahomans. They may sometimes speak like us Okies, which John did, but they’re, for the most part, from a different cultural experience. Saturday, when my wife Daisy and I were driving down the freeway to wherever we were going, I said:

“Daisy, I just thought of something. We should send a copy of my book, ‘The Oklahoma Gamblin’ Man,’ to John Cale. I mean, he’s from where all that stuff happened…he’d probably really enjoy reading it.”

“Yes, that’s a good idea; we have his mailing address in our files.”

“Daisy, check the Internet on your cell phone and see if there’s a decent movie on nearby. Maybe we could eat and go to a movie.”

Daisy complied.

“Oh my God!” Daisy exclaimed. “It says John Cale just died in La Jolla of a heart attack.”

So I guess I won’t be hearin’ that rich Oklahoma country brogue anymore…but I’m sure I’ll think about him once in awhile, like when it’s real quiet…like…After Midnight.

Published on December 02, 2014 14:24

•

Tags:

eric-clapton, gary-tanner, jj-cale, oklahoma-gamblin-man

June 20, 2014

Air-nges

Someone asked me why I named my beautiful orange Manx cat Air-nges. Well, here’s the story:

When I was about nine years old some of Pappy’s relatives came from eastern Oklahoma to California to visit. I think they probably stayed for a week or so out at my Aunt Kate’s and from there visited various family members. I remember they had two boys a bit younger than me and they came over to our house a couple of times. The family had a distinct Oklahoma brogue that my brother and I imitated when they were not around. My mother advised us that it wasn’t nice to make fun of the way other people talked. Pappy was from Oklahoma and had a bit of an “Okie” brogue, but it was more the way he constructed grammar than his actual phonetic pronunciation. It was like: “Awright you boys, git yer ass in the car ’for I take a notion to drive off and leave you here.”

The Oklahomans spoke more like: “High (hey) Die-vid (David)…why’nt y’all come on over ta Kites (Kate’s) hay-ouse (house) and brang (bring) yer bruuther (brother).”

It wasn’t that we thought we were better than them, our mother taught us better than that; we just thought they talked funny. Now my mother grew up on a farm in western Missouri. Lots of people from where she came from that came to California during the great depression talked like our visitors. She didn’t. I suspect Pappy didn’t either, because of her. She was, or could have been the prototype for June Cleaver a dozen years later.

The visitors came over one Sunday afternoon without their children and in the course of conversation Pappy offered to take them around the area to view the various landscapes. Now they don’t grow oranges commercially in Modesto, it’s too cold in the winter. What they do grow in large and impressive quantities are deciduous fruit (peaches, plums, apricots, etc.), almonds and walnuts, and grapes. But pappy knew of an orange grove that was geographically protected from the cold that was heavily laden with unpicked, ripe oranges and that’s where he decided to take them. We drove down a side road up to the beautiful orange grove and parked the car. I was in the front seat between Pappy and my mother. I don’t remember my brother David being there, but I remember our guests being in the back seat.

“Well, there she is.” Said Pappy.

“My God…would ya look at all them Air-nges!” exclaimed our cousin in the back seat.

“Air-nges?” I said, rather loudly, “Those aren’t Air-nges…those are Oranges.”

I can still remember the simultaneous surprise, pain and little stars I saw as my mother’s backhand hit the side of my head. It took at least half a minute before I could even see straight. No one said a word. Pappy, my mom and our cousins got out of the car and walked around admiring the wonderful orange grove. I stayed in the car, rubbing the knot my mother had put on the side of my head. She never looked at me until we got home. By then there was no need to explain her action…I had learned my lesson quite well.

My parents had dissimilar teaching techniques. Pappy was like an old Marine sergeant…he’d bark at you and make you think he was going to get physical, but he seldom did. Mom was like a dog trainer, she’d catch you in a compromising situation and make a “hard correction” that you’d never forget. I certainly never corrected anyone’s English after that, in fact I still sometimes offer visitors “Air-nges” from our beautiful trees in North San Diego County

When I was about nine years old some of Pappy’s relatives came from eastern Oklahoma to California to visit. I think they probably stayed for a week or so out at my Aunt Kate’s and from there visited various family members. I remember they had two boys a bit younger than me and they came over to our house a couple of times. The family had a distinct Oklahoma brogue that my brother and I imitated when they were not around. My mother advised us that it wasn’t nice to make fun of the way other people talked. Pappy was from Oklahoma and had a bit of an “Okie” brogue, but it was more the way he constructed grammar than his actual phonetic pronunciation. It was like: “Awright you boys, git yer ass in the car ’for I take a notion to drive off and leave you here.”

The Oklahomans spoke more like: “High (hey) Die-vid (David)…why’nt y’all come on over ta Kites (Kate’s) hay-ouse (house) and brang (bring) yer bruuther (brother).”

It wasn’t that we thought we were better than them, our mother taught us better than that; we just thought they talked funny. Now my mother grew up on a farm in western Missouri. Lots of people from where she came from that came to California during the great depression talked like our visitors. She didn’t. I suspect Pappy didn’t either, because of her. She was, or could have been the prototype for June Cleaver a dozen years later.

The visitors came over one Sunday afternoon without their children and in the course of conversation Pappy offered to take them around the area to view the various landscapes. Now they don’t grow oranges commercially in Modesto, it’s too cold in the winter. What they do grow in large and impressive quantities are deciduous fruit (peaches, plums, apricots, etc.), almonds and walnuts, and grapes. But pappy knew of an orange grove that was geographically protected from the cold that was heavily laden with unpicked, ripe oranges and that’s where he decided to take them. We drove down a side road up to the beautiful orange grove and parked the car. I was in the front seat between Pappy and my mother. I don’t remember my brother David being there, but I remember our guests being in the back seat.

“Well, there she is.” Said Pappy.

“My God…would ya look at all them Air-nges!” exclaimed our cousin in the back seat.

“Air-nges?” I said, rather loudly, “Those aren’t Air-nges…those are Oranges.”

I can still remember the simultaneous surprise, pain and little stars I saw as my mother’s backhand hit the side of my head. It took at least half a minute before I could even see straight. No one said a word. Pappy, my mom and our cousins got out of the car and walked around admiring the wonderful orange grove. I stayed in the car, rubbing the knot my mother had put on the side of my head. She never looked at me until we got home. By then there was no need to explain her action…I had learned my lesson quite well.

My parents had dissimilar teaching techniques. Pappy was like an old Marine sergeant…he’d bark at you and make you think he was going to get physical, but he seldom did. Mom was like a dog trainer, she’d catch you in a compromising situation and make a “hard correction” that you’d never forget. I certainly never corrected anyone’s English after that, in fact I still sometimes offer visitors “Air-nges” from our beautiful trees in North San Diego County

Published on June 20, 2014 16:28

July 19, 2013

Fish Story

The first time Dennis and I went “fishin’” I came back home with a string of a dozen, or so, fish. Dennis knew the names of the fish; we caught perch, blue gill, catfish and an occasional undersized bass of one stripe or another. I proudly walked up to our Las Flores Ave house and summoned my mother.

“Look Mom, I caught all these fish!”

“That’s nice, honey, what are you planning on doing with them?”

“Could we have them for dinner?” I asked.

“OK, but you’ll have to clean them for me.”

“Oh no, Mom,” I replied, “they’re already clean, I just took them out of the creek a half-hour ago.”

“That’s not how you ‘clean them’,” she countered, “go out back and get a board off the woodpile 6 or 8 inches wide and a couple of feet long.”

I was nine and I’d helped my grandpa build our back fence, so I know how to select a board such as she described. I returned to the front yard and she was already standing by with a formidable looking kitchen knife and a flat pan.

“OK,” she began, “first you cut their heads off, like this.”She took the sharp knife and pulled it across the fish, just below the head. She moved the detached head over with the knife and then instructed:

“Then you cut the tail off, like this.”

Cutting the tail off wasn’t as unpleasant to watch as the head had been and I thought, “well, this isn’t that bad…I can do this.”

“All right, now you have to gut them.”

“Gut them!”...Geez, that didn’t sound like something I’d ever want to do. But I watched as she ran the knife down from where the severed head had been, all the way to where she had removed the fishtail.

“Now all you have to do is take the knife and scrape out all the insides, leaving the spine and connecting ribs, along with the flesh. Take the guts and put them in this bag.”

“Mom, I don’t think I want to do this,” I said, “Can we just throw all the fish in the garbage and forget about having them for dinner?”

“Sure,” she said with a mischievous smile, “so you won’t be needing to go to the creek anymore and can hang around here with your little brother.”

“OK. I’ll gut the dang things,” I said, “hand me the knife.”

In a few minutes I was cutting and gutting like I’d been doing it my whole life…all nine years. When I had my catch thoroughly prepared, I took them inside, into the kitchen and presented them to my mother. She very graciously accepted them and began to make the preparation she would coat them with before placing them in the frying pan. I returned outside and took the God-awful smelling fish heads, tails and guts to the garbage can, where I buried them deep inside to block as much of the foul smell as possible. When Pappy came home we had a fish dinner and my mom told Pappy what a fine fisherman and fish gutter I was. I ate a couple of the fish, but except for an occasional tuna sandwich, I don’t think I ever ate fish again. That doesn’t mean I didn’t continue to fish. I just got smart fast and learned to take them to the neighbors before I came home with them.

Published on July 19, 2013 09:00

July 12, 2013

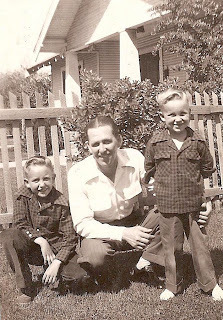

From My Rear View Mirror

So when I was about eight years old Pappy opened a plumbing shop across the street from our house at 108 Las Flores Ave., Modesto, CA. At that time I was beginning to pressure my mother to allow me to join some of the older boys in the neighborhood at Dry Creek, which was about a quarter mile from our house. By the time I was 9-10 years old, my life was full of adventure, alternating between playing with my friends at “the creek” and hanging out across the street from the plumbing shop. Sometimes I would spend several hours playing in the neighborhood with a conglomeration of kids of various ages. There were a couple of teenage boys that I admired who allowed me to “hang out” a bit with them. Both would serve in the Korean War, one as an air force fighter pilot, who was killed in combat and the other with the 82ndAirborne. Closer to my age were the Wilber boys who lived a block away and always seemed to have some kind of ball game, or adventure of one kind or another planned, or going on.

My first trip to “the creek” was with a boy a couple of years younger than me to go fishing. I was nine and had gone fishing with my dad several times, so I knew how to bait a hook and string whatever fish we might catch. My younger friend Dennis had been allowed to fish there at such a young age because you could see most of the creek from his house and also because his parents worked and his elderly grandmother who was supposed to be keeping track of him, hardly ever did. Luckily for me, I was able to parlay Dennis’s situation into a formidable argument that I was two years older than him and my mother was treating me like a baby.

Pappy was busy and didn’t concern himself with my day to day activities much; unless of course I wandered over to the shop, in which case he usually put me to work. Pappy taught me how to thread pipe with a Ridgid 3-way die and stock miscellaneous fittings in the appropriate bins. He paid me fifteen cents an hour, which seems paltry in today’s world, but you could buy a large candy bar or a soda for a nickel. I could work three or four hours during the week and have enough money to attend the Saturday afternoon matinee at the La Loma Theater, two blocks from our house for a twenty cent admission, pop corn for a dime and candy and soda as previously mentioned. In a couple of years I had advanced in skill and work ethic to a point where I could command, first twenty-five cents an hour and then thirty-five cents an hour. Add a couple of extra hours on Saturday morning and I might have a couple of bucks with which to maneuver. A large milkshake at the Foster Freeze cost a quarter. Pappy had grown up in rural Oklahoma in a large family and was as independent as he was street-wise. He didn’t over parent; he just allowed me to try whatever I wanted to and encouraged me to approach life fearlessly. That’s what he did…it was a hard standard to live up to.

Regardless, I could drive a truck when I was twelve, create lead joints for cast iron plumbing systems, run a pipe machine and dig a plumbing trench at an even younger age. Simultaneously, I spent as much time hanging out with my friends and listening to music, reading comic books and going to movies as I could manage. Although Pappy didn’t have much formal education, his business grew rapidly. I grew along with it and when it was discovered that I hadn’t attended school for four months, I was allowed to quit school and begin working full time at barely sixteen years old. The three years between leaving school and being inducted into the U.S. Army provided me with social and learning experiences that gave me enough confidence, ambition and grit to successfully navigate through my “roaring twenties.”

My first trip to “the creek” was with a boy a couple of years younger than me to go fishing. I was nine and had gone fishing with my dad several times, so I knew how to bait a hook and string whatever fish we might catch. My younger friend Dennis had been allowed to fish there at such a young age because you could see most of the creek from his house and also because his parents worked and his elderly grandmother who was supposed to be keeping track of him, hardly ever did. Luckily for me, I was able to parlay Dennis’s situation into a formidable argument that I was two years older than him and my mother was treating me like a baby.

Pappy was busy and didn’t concern himself with my day to day activities much; unless of course I wandered over to the shop, in which case he usually put me to work. Pappy taught me how to thread pipe with a Ridgid 3-way die and stock miscellaneous fittings in the appropriate bins. He paid me fifteen cents an hour, which seems paltry in today’s world, but you could buy a large candy bar or a soda for a nickel. I could work three or four hours during the week and have enough money to attend the Saturday afternoon matinee at the La Loma Theater, two blocks from our house for a twenty cent admission, pop corn for a dime and candy and soda as previously mentioned. In a couple of years I had advanced in skill and work ethic to a point where I could command, first twenty-five cents an hour and then thirty-five cents an hour. Add a couple of extra hours on Saturday morning and I might have a couple of bucks with which to maneuver. A large milkshake at the Foster Freeze cost a quarter. Pappy had grown up in rural Oklahoma in a large family and was as independent as he was street-wise. He didn’t over parent; he just allowed me to try whatever I wanted to and encouraged me to approach life fearlessly. That’s what he did…it was a hard standard to live up to.

Regardless, I could drive a truck when I was twelve, create lead joints for cast iron plumbing systems, run a pipe machine and dig a plumbing trench at an even younger age. Simultaneously, I spent as much time hanging out with my friends and listening to music, reading comic books and going to movies as I could manage. Although Pappy didn’t have much formal education, his business grew rapidly. I grew along with it and when it was discovered that I hadn’t attended school for four months, I was allowed to quit school and begin working full time at barely sixteen years old. The three years between leaving school and being inducted into the U.S. Army provided me with social and learning experiences that gave me enough confidence, ambition and grit to successfully navigate through my “roaring twenties.”

Published on July 12, 2013 23:40

Eight Years Old

So when I was about eight years old Pappy opened a plumbing shop across the street from our house at 108 Las Flores Ave., Modesto, CA. At that time I was beginning to pressure my mother to allow me to join some of the older boys in the neighborhood at Dry Creek, which was about a quarter mile from our house. By the time I was 9-10 years old, my life was full of adventure, alternating between playing with my friends at “the creek” and hanging out across the street from the plumbing shop. Sometimes I would spend several hours playing in the neighborhood with a conglomeration of kids of various ages. There were a couple of teenage boys that I admired who allowed me to “hang out” a bit with them. Both would serve in the Korean War, one as an air force fighter pilot, who was killed in combat and the other with the 82ndAirborne. Closer to my age were the Wilber boys who lived a block away and always seemed to have some kind of ball game, or adventure of one kind or another planned, or going on.

My first trip to “the creek” was with a boy a couple of years younger than me to go fishing. I was nine and had gone fishing with my dad several times, so I knew how to bait a hook and string whatever fish we might catch. My younger friend Dennis had been allowed to fish there at such a young age because you could see most of the creek from his house and also because his parents worked and his elderly grandmother who was supposed to be keeping track of him, hardly ever did. Luckily for me, I was able to parlay Dennis’s situation into a formidable argument that I was two years older than him and my mother was treating me like a baby.

Pappy was busy and didn’t concern himself with my day to day activities much; unless of course I wandered over to the shop, in which case he usually put me to work. Pappy taught me how to thread pipe with a Ridgid 3-way die and stock miscellaneous fittings in the appropriate bins. He paid me fifteen cents an hour, which seems paltry in today’s world, but you could buy a large candy bar or a soda for a nickel. I could work three or four hours during the week and have enough money to attend the Saturday afternoon matinee at the La Loma Theater, two blocks from our house for a twenty cent admission, pop corn for a dime and candy and soda as previously mentioned. In a couple of years I had advanced in skill and work ethic to a point where I could command, first twenty-five cents an hour and then thirty-five cents an hour. Add a couple of extra hours on Saturday morning and I might have a couple of bucks with which to maneuver. A large milkshake at the Foster Freeze cost a quarter. Pappy had grown up in rural Oklahoma in a large family and was as independent as he was street-wise. He didn’t over parent; he just allowed me to try whatever I wanted to and encouraged me to approach life fearlessly. That’s what he did…it was a hard standard to live up to.

Regardless, I could drive a truck when I was twelve, create lead joints for cast iron plumbing systems, run a pipe machine and dig a plumbing trench at an even younger age. Simultaneously, I spent as much time hanging out with my friends and listening to music, reading comic books and going to movies as I could manage. Although Pappy didn’t have much formal education, his business grew rapidly. I grew along with it and when it was discovered that I hadn’t attended school for four months, I was allowed to quit school and begin working full time at barely sixteen years old. The three years between leaving school and being inducted into the U.S. Army provided me with social and learning experiences that gave me enough confidence, ambition and grit to successfully navigate through my “roaring twenties.”

My first trip to “the creek” was with a boy a couple of years younger than me to go fishing. I was nine and had gone fishing with my dad several times, so I knew how to bait a hook and string whatever fish we might catch. My younger friend Dennis had been allowed to fish there at such a young age because you could see most of the creek from his house and also because his parents worked and his elderly grandmother who was supposed to be keeping track of him, hardly ever did. Luckily for me, I was able to parlay Dennis’s situation into a formidable argument that I was two years older than him and my mother was treating me like a baby.

Pappy was busy and didn’t concern himself with my day to day activities much; unless of course I wandered over to the shop, in which case he usually put me to work. Pappy taught me how to thread pipe with a Ridgid 3-way die and stock miscellaneous fittings in the appropriate bins. He paid me fifteen cents an hour, which seems paltry in today’s world, but you could buy a large candy bar or a soda for a nickel. I could work three or four hours during the week and have enough money to attend the Saturday afternoon matinee at the La Loma Theater, two blocks from our house for a twenty cent admission, pop corn for a dime and candy and soda as previously mentioned. In a couple of years I had advanced in skill and work ethic to a point where I could command, first twenty-five cents an hour and then thirty-five cents an hour. Add a couple of extra hours on Saturday morning and I might have a couple of bucks with which to maneuver. A large milkshake at the Foster Freeze cost a quarter. Pappy had grown up in rural Oklahoma in a large family and was as independent as he was street-wise. He didn’t over parent; he just allowed me to try whatever I wanted to and encouraged me to approach life fearlessly. That’s what he did…it was a hard standard to live up to.

Regardless, I could drive a truck when I was twelve, create lead joints for cast iron plumbing systems, run a pipe machine and dig a plumbing trench at an even younger age. Simultaneously, I spent as much time hanging out with my friends and listening to music, reading comic books and going to movies as I could manage. Although Pappy didn’t have much formal education, his business grew rapidly. I grew along with it and when it was discovered that I hadn’t attended school for four months, I was allowed to quit school and begin working full time at barely sixteen years old. The three years between leaving school and being inducted into the U.S. Army provided me with social and learning experiences that gave me enough confidence, ambition and grit to successfully navigate through my “roaring twenties.”

Published on July 12, 2013 23:40