Robin Kirk's Blog

May 8, 2020

Mapping the imaginary

This post first appeared in Fantasy Cafe

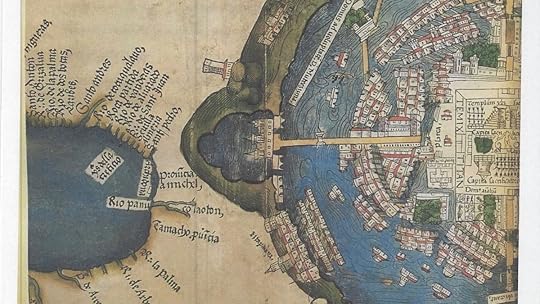

Map-makers have always drawn with their imaginations even when they thought they were making factual representations. Recently, I came across this detailed depiction of Tenochtitlán, the Aztec empire’s capital, published anonymously on Nuremberg in 1524 and featured in Elizabeth Hill Boone ’s The Aztec World. Some elements are somewhat accurate. The city was built on an island. Commerce on the pictured road was robust as tribute poured in from subjugated communities. As Boone writes, one Spaniard noted of the actual city how “everything was whitened and polished, indeed the whole place was so clean that there was not a straw of a grain of dust to be found there.”

A 1524 map of the Aztec capital, Tenochtitlán, from The Aztec World by Elizabeth Hill Boone

A 1524 map of the Aztec capital, Tenochtitlán, from The Aztec World by Elizabeth Hill BooneBut what of the round cylinders toward the base? How is the small, lake-like body of water to the left connected to the city? To some extent, all maps include some level of the imaginary (if only because the planet and the people on it are always moving). Maps include more than location and building style. For instance, at the upper right of the Nuremberg map, the distinctive coat of arms of Charles V, the Holy Roman Emperor and ruler of much of modern-day Europe, waves over a depiction of the conqueror’s castle. This is history, Spain’s bloody takeover not more than three years earlier.

The Latin inscriptions tell another tale. Not only was this the language of European officialdom. The Catholic Church supported adventurers like Hernán Cortés, who toppled the empire, and forcibly and sometimes murderously converted the indigenous population, at first more interested in numbers than the survival of new adherents. The map itself communicates power and control. Many scholars argue that the act of drawing maps of subjugated peoples and continents has been a part of building empire.

Fantasy maps turn real-world cartography on its ear. Instead of using real places to spin fantasy, fantasy maps use the format and conventions of actual maps to build imagined worlds. Whether the maps are street-level depictions or include whole continents, fantasy maps parlay our assumptions and relationships with maps into delightful imagined worlds. Like the Spanish map of Tenochtitlán, they also can serve as a powerful story-telling tool, showing us the central conflicts of the stories we love.

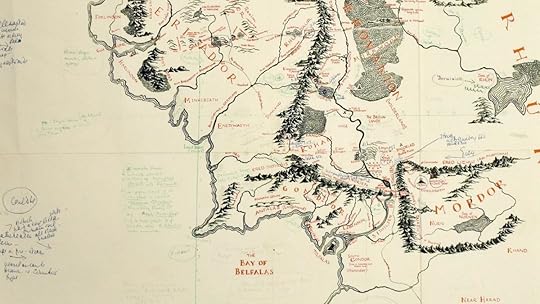

Like many, I got my first introduction to fantasy maps from J. R. R. Tolkien. As he wrote, for him, the map was not an extra, but a first step in story-telling, since “in such a story one … must first make a map and make the narrative agree.” His youngest son, Christopher, drew the map included in the 1954 publication of the first two volumes of The Lord of the Rings. Recently, Tolkien’s own annotated version of the map resurfaced, prepared for illustrator Pauline Baynes for the 1969 poster of Middle-earth.

Courtesy of the Bodleian Libraries at the University of Oxford

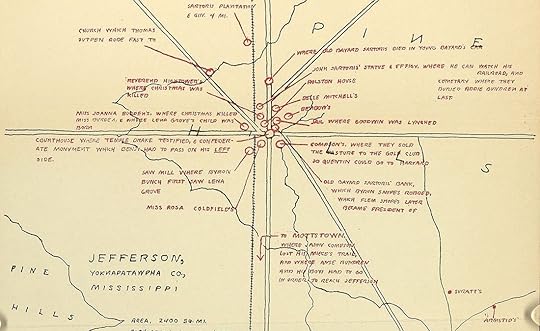

Courtesy of the Bodleian Libraries at the University of OxfordIn his gorgeous The Writer’s Map: An Atlas of Imaginary Lands, Huw Lewis-Jones mixes real-life maps with imaginary ones: Philip Pullman’s Eschtenburg from The Tin Princess, Anthony Trollope’s Barsetshire, William Faulkner’s Yoknapatawpha County, among others. Clearly, not all belong to completely fantastical realms. But Faulkner seemed just as insistent on his map as Tolkien, scribbling on one draft, “Surveyed & mapped for this volume by William Faulkner.”

In his gorgeous The Writer’s Map: An Atlas of Imaginary Lands, Huw Lewis-Jones mixes real-life maps with imaginary ones: Philip Pullman’s Eschtenburg from The Tin Princess, Anthony Trollope’s Barsetshire, William Faulkner’s Yoknapatawpha County, among others. Clearly, not all belong to completely fantastical realms. But Faulkner seemed just as insistent on his map as Tolkien, scribbling on one draft, “Surveyed & mapped for this volume by William Faulkner.”

William Faulkner, Absalom, Absalom! (New York: Random House, 1936). Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections, University of Virginia

William Faulkner, Absalom, Absalom! (New York: Random House, 1936). Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections, University of VirginiaLibrary, Charlottesville, Va.

There’s a lovely practicality to black-and-white maps and an exuberance to color maps, including maps made to accompany comic books. Maps were so important to science fiction that Dell published “map-backs” in the late 1940s, each book featuring a color map on the back. Lewis-Jones highlights their playful, interactive appeal as “invitations. We can read them, draw and redraw them, use them share them, add and alter them, enter into them. As representations, they are always partial, always incomplete, and yet they always offer us more than what is held there on paper alone.”

When I wrote The Bond, the first book in my YA fantasy trilogy, I had a rough idea of the landscape in my head. I love California’s Trinity Alps, my inspiration for the Black Stairs. I lived in Peru and experienced many a breathless (and terrified) moment crossing the Andes. Mountains had to be a part of the story.

But I also loved the wet denseness of the jungle, the crisp clarity of the puna, the high mountain desert. Perhaps a bit like Tolkien, I realized I had to draw a map if I was ever to write an intelligible story.

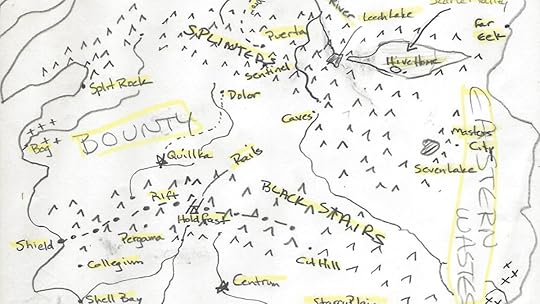

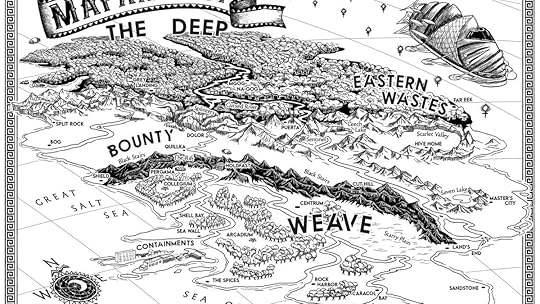

The first versions were for me alone. My questions were practical. If my main character was headed north, how far until she reached a plain? With Book II, The Hive Queen, I opened up a whole new area, the Eastern Wastes. There were rivers to cross, hidden valleys to traverse, strange cities to discover.

About mid-way through the revision of The Hive Queen, I realized readers, too, might appreciate a map. I was lucky enough to find a wunderkind map-maker to work with. I could tell by Travis Hasenour’s maps that he was precisely the artist I wanted (here’s his online portfolio). Each of his maps is different, each wonderfully calibrated to story, and all reveal a deep respect for the author’s world along with an inventiveness that I could never match.

I sent him my best guess at a map. Even the act of drawing it sent me running back to the text, to adjust a mountain range or the curve of a river.

My original, not-so-great version

My original, not-so-great versionWhen Travis sent a first draft of his interpretation, I had to sit down to catch my breath. It was … spectacular. Once, a young reader came up to me to ask a question about one of my characters and I felt the equivalent of a gut punch. How did she know this character? I wondered crazily. Characters take up spaces in writers’ brains, and then they walk — or leap or dance — into the heads of readers just as if they were real.

The way maps work is eerily, magically similar. When Travis sent me the final version of The Bond’s Mapamundi, it was as if I experienced a dozen good birthdays and holidays together. And cheesecake. I’ve written a world into existence and now, through the power of words and a map, it exists.

There’s no more reachable magic than this. Travis included so many lovely details — the whispered ships traveling the Signal Way, the star-shaped schools, the stylish compass rose. Though I wrote the story, it’s more real to me when I gaze at this marvelous map.

I’m doing a “map reveal” here, in advance of The Hive Queen’s August release. I hope you enjoy it — and come back for the story!

The post Mapping the imaginary appeared first on .

April 27, 2020

Science Fiction and Human Rights

“Science fiction is one of the greatest and most effective forms of political writing.”

Nnedi Okorafor, award-winning author of the Binti series

Originally published in Fantasy Cafe, April 24, 2020

Science fiction is often credited for inspiring advances in technology. Jules Verne, author of adventure stories like 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea, may have inspired submarines. Arthur C. Clarke imagined using satellites for global communications. Lillian Cunningham’s gripping “Moonrise” podcast, produced for the Washington Post, traces how science fiction helped propel both the Soviet and American space programs.

As a longtime human rights advocate as well as a sci-fi writer, I believe this genre has inspired more than objects. Through the lens of story, we’ve also explored ideas about how society could or should function. Women writers especially have tested the boundaries of what it means to be human and live in connection with other humans.

And that shapes what rights we think we do or should have—even who should have rights at all. This observation is almost as old as science fiction itself. As the world careened toward World War II, H.G. Wells—author of War of the Worlds, The Time Machine, and The Invisible Man, among other works, and a committed socialist—wrote “The Rights of Man,” a prescient treatise that proposed not only political rights, but rights to nourishment, housing, health care, and a home.

Taken from the book deposited with the Locus collection at the Rubenstein Rare Book and Manuscript Archives at Duke University

Taken from the book deposited with the Locus collection at the Rubenstein Rare Book and Manuscript Archives at Duke UniversityIn “Imagining Human Rights: rights through the lens of speculative fiction,” a class I taught this semester at Duke University, I relied on authors like Ursula K. Le Guin, Octavia E. Butler, and Nnedi Okorafor, among others, to explore how women writers have compelled us to examine the complexities of rights and how they may shift—or explode in our faces.

I started the course with Le Guin’s deceptively simple short story, “The Ones Who Walk Away from Omelas.” For me, the story presents a powerful allegory for our willingness in modern society to accept the suffering of others so long as we are comfortable. In a 2018 Paris Review interview, N.K. Jemisin described a category of what she called “Omelas stories,” which, like Le Guin’s spare tale, “gut punch(es) you with the fact that this is the reality of living in a modern capitalist society. You are living at the expense of, amid the pain of, a lot of people who have suffered to bring you the wonderful lifestyle that you’ve got—if you’ve got that wonderful lifestyle at all, which a lot of folks in this country right now do not.”

Some students had read the story in high school and remembered the relatively simplistic moral they’d gleaned. Of course, they stated, one should walk away from such suffering. Using Jemisin’s analysis, I pressed them. Walking away changes nothing for that child. How, exactly, are you looking for that metaphorical child in your life? While some of my students come from wealthy families, others are first-generation and overcame immense obstacles to go to a place like Duke. They felt they had “earned” the right to be there. But what would it mean to really open that door and peer in at the child whose suffering helped make their success possible? Would any of them—could they—walk away from the Omelas that is Duke’s verdant campus?

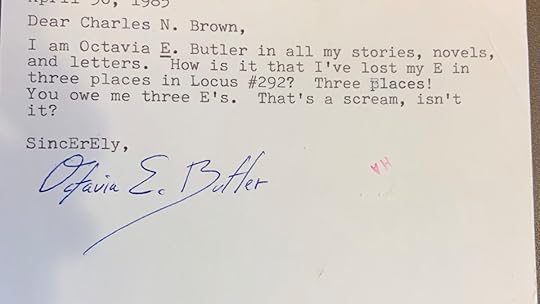

Postcard from Octavia E. Butler in the Locus collection at the Rubenstein Rare Book and Manuscript Archives at Duke University

Postcard from Octavia E. Butler in the Locus collection at the Rubenstein Rare Book and Manuscript Archives at Duke UniversityThe class came alive on the day we discussed Butler’s “Bloodchild.” Previously, we’d visited Duke’s Locus Archive and I’d helplessly fan-girled over a Butler postcard to her editor (“I am Octavia E. Butler in all my stories, novels, and letters. How is it that I’ve lost my E in three places in Locus #292? Three places! You owe me three E’s.”). “Bloodchild,” winner of a 1984 Nebula Award and a 1985 Hugo Award, forced the students to detach from gender norms and ask what assumptions they had about rights when faced with survival.

Butler’s protagonist, Gan, is a male human born on an alien planet. With his family, Gan lives in a protected reserve run by T’Gatoi, a Tlic noble. T’Gatoi is a gentle, though firm, ruler. The pact with humans is simple. Each family commits one male child per generation to incubate a Tlic egg.

As with Butler’s other stories, including the mind-bending Xenogenesis series, the relationship can’t be distilled into a simplistic narrative of slavery or gender-bending. Butler maintained that her inspiration for “Bloodchild” lay in issues of sex and gender. These categories presume trade-offs around rights, especially as we edge into worlds where bodies (and body parts) are purchased and hired to create and carry children. In many areas, gender fluidity is replacing gender binaries. My students went over allowed class time as they discussed how this story related to their own lived experience around consent and future plans to have or not have children.

The Xenogenesis trilogy by Octavia E. Butler

The Xenogenesis trilogy by Octavia E. ButlerWe even drew the Tlic, an exercise in disgust and fascination. I certainly could not have written the books in my own gender-bending fantasy series, The Bond and The Hive Queen, without having first read Butler.

Sadly, our in-person discussions were interrupted by the COVID-19 pandemic. I’d managed to somehow pair the cancellation of classes with the assignment of M.R. Carey’s The Girl with All the Gifts, planning to frame a discussion of rights and climate change once students returned from Spring Break. As it turned out, Carey’s apocalyptic tale and his unforgettable heroine, Melanie, were just as suited to a discussion of pandemic as rebirth and reveal.

Our final assignment is Nnedi Okorafor’s “Spider the Artist,” which takes place in a future Nigeria where multinational corporations defend oil pipelines with spider-like zombies. Fitting for an end-of-class discussion, the story introduces students to a woman who chooses to stand up for justice. In an interview posted to her blog, Okorafor says this story was the first she wrote consciously as pure science fiction.

The story is so rich in sensory detail that I wonder if my students will enjoy feeling transported from their quarantine homes into a Nigerian village so damaged by exploitation that “The air left your skin dirty and smelled like something preparing to die. In some places, it was always daytime because of the noisy gas flares.” Okorafor gives us a rich palette of Nigerian folklore, current politics, and the life experience of so many oppressed people, at the mercy of savage capitalism yet still determined to be human and fight for their rights. For Okorafor, “science fiction is one of the greatest and most effective forms of political writing.”

Only recently have women been fully recognized as having shaped our science fiction imaginary (despite the fact that the creators of the genre include writers like Frankenstein’s author, Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley, whose mother was a women’s rights champion). In some cases, the contributions are seismic in terms of rights and not confined to the page. Sometimes, just the fact that people of color, women, and the disabled, among others, are visible, regardless of what they are producing, is a rights advance.

For instance, Nichelle Nichols, the actor who played Lieutenant Uhura on Gene Roddenberry’s original Star Trek, famously considered leaving the show to return to her first love, musical theater. After telling Roddenberry, she happened to attend a fundraiser where the organizers asked to introduce her to a fan. She was shocked when that fan turned out to be the Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr.

King told her that Star Trek was one of the few shows he and his wife, Coretta, watched with their three children. When she told King she planned to leave the show, he protested. With the role, he told her, she was showing the world that African Americans were accomplished and capable of doing anything, including traveling the universe.

Nichols chose to remain. She went on to push NASA to recruit more women and people of color, helping to bring in Sally Ride, Guion Bluford, and Mae Jemison, the first black woman to go into space.

When I teach the class again—hopefully with this pandemic in our collective rear-view mirror—my challenge will not be to find material but to pare down the richness of what’s available. My students have helped me see science fiction in a different way, now through the lens of a generation shaped by pandemic and profoundly familiar with how life and their prospects can change in an instant. My one hope is that these stories will help them cope with those changes and feel less defeated by them. It’s a challenge to all writers to find ways to help people understand that they matter and that stories can help us see each other and our planet as precious.

The post Science Fiction and Human Rights appeared first on .

August 12, 2019

Appreciation vs. Appropriation

The conversation over cultural appropriation is necessary, long in coming, and deeply fraught. By their nature artists, including writers, absorb and incorporate many things into their work. Groups and cultures do this, too. Journalist Nadra Kareem Nittle notes that Americans who grow up in diverse communities “may pick up the dialect, customs, and religious traditions of the cultural groups that surround them,” all natural, predictable, and even desirable… (read more here)

The post Appreciation vs. Appropriation appeared first on .

July 24, 2019

July newsletter

I spent June completing revisions on Book II, tentatively scheduled for next year. My days started early (5 am) and often ended quite late, a marathon of character development, pacing adjustments, and plot connections. I immersed myself so deeply in my story that I would dream about it. Every time I took a walk (or took a shower or revived myself with food), I’d think of a new problem or solution to a pesky roadblock.

One of the pieces of writing advice that helped me came from one of my editors at Blue Crow. In a blog post, Lauren Faulkenberry writes about “a series of chain reactions” for her characters. I kept thinking about that as I wrestled with the revisions. That concept doesn’t determine what will happen, only that whatever happens must be intimately connected and lead to a following, equally connected action. Each action must help illuminate character, move the story forward, create change, spark interest in the reader, and, above all, be true to the story.

My “to-do” piles

My “to-do” pilesIt was in those intense moments that my characters “spoke” to me. I used to be impatient with writers who claimed that their characters communicated with them. That seemed too ethereal to me (plus I’d never experienced that phenomenon). But in the growing heat of June, a kind of magical thing did happen. As I searched for that perfect “chain reaction,” I was obligated to think deeply, viscerally, about how this character that I’d constructed would react: what they would think, what they would fear, what they would do. It was in these moments that the characters “spoke” to me, helping me create what I hope will be a gripping, unique story.

By the time I was finishing, I felt something else that was new: responsibility. I’ve created this world, and it’s up to me to do whatever I can to make sure that this world is preserved somehow. This is a special responsibility of those of us who write fiction and even more so those of us who create worlds that are spun out of our imaginations. Although The Bond has been out for over 7 months, I still feel a little jolt when a reader comments on a character or a twist in the story.

I panic—how do you know about this?—until I remember that, of course, this is printed in an actual book!

Now that the revision is submitted, I’m on to a novella I’ve been working on, a non-fiction book on human rights and memory, picture books, and a new non-fiction series for kids on human rights!

A little teaser

All of that and no taste of Book II? Here’s a little teaser, from the opening scene:

I never meant to kill my brothers.

As the hyba pack swings into the pine branches above our heads, I know that’s what I may have done. Seven days ago, I convinced my brothers to escape the city of Dolor. We were escaping our mother, a Captain, and Bounty itself. We were escaping the mother-bond that kept us at her mercy.

I told them the only way we’d ever be free is to run now, that day, before the helio fleet arrived from the south and blasted everyone to bits. None of us, not even our mother, will survive the Weave’s second attack, I told them. “What good is freedom to the dead?” I asked them.

Freedom: the shape word is a fist opening. My mother left me with a tongue, since she thought I’d need it as second to our commander. All but one of my brothers, our singer, is docked.

As I spoke to them, my brothers huddled in the shadow of Dolor’s lava beds. After a long silence, Tanoak answered for all eighteen of them. He’s strongest and most like my mother, with a red-brown top-knot and green eyes. We follow where you lead, Fir. To freedom or to death. You choose.

I didn’t tell them I had no more than fireside tales about the dangers awaiting us to the east. I can’t predict how far we’ll have to run to find this Master of men or even if we ever will. The Master rules a land to the east where men can be free.

Or so we’ve been told by the wildmen visiting our night fires. They also spoke of a draft Queen who lures wildmen who are never seen again. As we listened to their tales, we pitied the wildmen, sons rejected by their Captains and forced to fend for themselves. The lives of my brothers are weights I’ve carried ever since my brother Ash died.

What I’m Reading

I am a huge fan of James S. A. Corey’s “The Expanse” series. Corey is the joint pen name of authors Daniel Abraham and Ty Franck. The soon-to-be nine-book series is a sweeping tale about a future in which humanity has colonized much of the Solar System. But humans are still humans, and conflict brews between Earth’s United Nations, Mars, the asteroid belt and outer planets.

In addition to the books, there’s an excellent Amazon Prime show as well as short stories, novellas, and comic books. Currently, I’m on Book 2, Caliban’s War.

It’s a great next big read while I’m waiting for George R. R. Martin to finish Winds of Winter, Book Six in the “Game of Thrones” series.

One of the best things about the “The Expanse” series is how effortlessly the authors incorporate gender, racial, and cultural diversity. One of my favorite characters is “Gunny,” aka Roberta “Bobbie” W. Draper, a Martian gunnery sergeant. In the Amazon Prime television series (equally excellent), Gunny is played by Frankie Heard, a New Zealand-Samoan actress who captures both Draper’s uncertainties about her loyalties and her strength and willingness to kill in the service of her commanders.

Book News

I was very lucky to have The Bond recognized by two awards this summer. In June, Foreward Reviews chose The Bond for its 2018 Bronze Indies Award for YA fiction. Also, The Bond was a finalist in The North Carolina Speculative Fiction Foundation’s 2019 Manly Wade Wellman Award for North Carolina Science Fiction and Fantasy.

I had a great time talking about The Bond with my colleagues at the Franklin Humanities Institute, who chose the book for their summer read. There’s nothing like a group of committed, interesting readers to illuminate parts of the story I hadn’t thought about before.

My colleagues at Duke’s Franklin Humanities Institute after our discussion of The Bond.

My colleagues at Duke’s Franklin Humanities Institute after our discussion of The Bond.I’m really looking forward to taking part in the LoonSong Writer’s Retreat in early September. I’m especially looking forward to seeing one of my former faculty members from the Vermont College for Fine Arts, Elizabeth Partridge. Friends who’ve taken part tell me that the weekend is the perfect combination of writing, workshopping and enjoying the late summer delights of a Minnesota lake. I’m up for all three.

Social Media

I’ve started following a new Twitter hashtag, #vss365. Every day, writers all over the world respond to a word prompt with poetry, prose, photos. It’s fun! Here’s my response to #fury:

Imperator Furiosa is indifferent to your wails, your #fury , your incessant attack. She has armored herself, of course. But it’s more her mind: already past you. She’d give everything for that cosmos: to see it flower. You, however, are already dust

Photo of the month

I’ve taken out most of my ornamental plants and grass, replacing them with pollinators and natives, mostly gifted from neighbors. This helps the critters with food and habitat.

It’s high summer, but there’s been an unusual amount of rain. The garden loves the moisture (the tomatoes, not so much). One of my favorite plants is this wild cosmos. Over several years, I’d strip off the seeds from plants by the sidewalk. So now, I have a lot of it! The bright orange petals always brighten my day.

Wild cosmos

Wild cosmosThanks for reading! To subscribe to my newsletter, please scroll to the contact form here.

The post July newsletter appeared first on .

May 13, 2019

Serious in Seoul

When I learned that I had been accepted to a month-long writing residency at Seoul Arts Center-Yeonhui, I prepared by learning as much as I could about the city and South Korea. What I couldn’t prepare for was meeting one of the world’s most interesting and prolific Young Adult writers: Sinta Yudisia. The author of over 60 books, Sinta is a rock star in Indonesia, her home. She’s also a fascinating person who is an #ownvoices treasure.

Me with Sinta Yudisia

Me with Sinta YudisiaI interviewed Sinta in the Seoul Arts Center-Yeonhui library, a pleasant space built into one of Seoul’s many hills. The bookshelves are wonderfully – and intentionally — crooked and the lights are shaped like giant commas. Sinta came with a copy of her next book, Sirius in Seoul, a sequel to Polaris Fukuoka and featuring the same heroine, Sophia. Sophia is an orphan who lives with her uncle. He has a job in Japan, then South Korea. Like Sinta, Sophia is a devout Muslim who is also passionately interested in travel, language, other cultures, and books. She’s written for adults as well and also has several non-fiction books, including books about the unique cultures of Palestine and Indonesia. The book Sinta wrote about Indonesian culture is Reinkarnasi, about the magic and the power of keris, traditional Javanese swords.

Indonesia is the world’s most populous Muslim-majority country. Located in Southeast Asia and surrounded by the Pacific, Indonesia is also the world’s largest island country. The country is an #ownvoices master class, with hundreds of ethnic and linguistic groups.

Yudisia’s latest

Yudisia’s latestYA novel

Sinta spent part of her time in Seoul visiting locations she used in Sirius in Seoul, scouted on a previous visit, and making galley corrections. As yet, her work hasn’t been translated from Indonesian to English, so I’m hoping this interview snags Sinta an interested translator and publisher. This interview was originally published in YA Interrobang.

Follow Sinta on Facebook, Twitter, Goodreads, or her blog.

Tell me a little about yourself.

I’m from Surabaya, a port city on the Indonesian island of Java. This city mixes up the modern with canals and buildings from our Indonesian and Dutch colonial past. I’m a psychologist by training and I’m married with four children. My eldest, a girl, is 22. I started writing in 2000 with a book about cats. Then I wrote When Upi Asked (Ketika Upi Bertanya), a fable about a butterfly family, and Cici’s Promises (Janji Cici), about a family of cats. I write about three books every year, including short story collections. Usually, I get up in the middle of the night to write for a couple of hours. Then I have to get my family off to work and school. When I was a child, I had such a big imagination. I wanted to fly, be a police officer, be a princess. I’m able to explore that imagination as a writer. I get a lot of ideas from what I’m reading and from my dreams, even when they are nightmares.

Who are some of your favorite writers?

I have so many! Leo Tolstoy, Anton Chekhov, J.K. Rowling, Naguib Mafouz. One of my favorite writers for children is Jostein Gaarder. He is a Norwegian who’s written novels, short stories and children’s books like Sophie’s World: a novel about the history of philosophy.

Who is your ideal reader?

I love readers who give me feedback, including through social media. I like when they’ve really engaged with a book and encourage me to dig deeper into character and explore more what’s going on with my characters emotionally. I promote my books on Instagram, Facebook, Twitter, and on my blog and also do school and bookstore visits. Most readers in Indonesia are female and many of them have a big question: who am I? They want to be global citizens and are on social media constantly but at the same time they are Indonesian. Many have friends on social media but not in real life. Sophia, the main character in Polaris Fukouka and Sirius in Seoul, is also Muslim and is dealing with how she remains faithful to her religion when she’s with friends who aren’t Muslim.

Your two most recent books follow Indonesian teens in two of the most interesting teen cultures in the world, Japan and South Korea. Why did you choose these settings?

Indonesian teens are very fond of both Japan and South Korea. They love K-Pop! (I include a “Best of K-Pop sampler below.) I wanted to write about a girl who is in both places and struggling with what it means to be herself. Sophia has to live with her uncle, who works in Fukuoka, then Seoul. In Seoul, she is on summer holidays. She is looking for her secret cousin, and here the adventure begins. Sophia learns a lot about herself in these two places. She has to adapt to live as a Muslim wearing a hijab. She doesn’t eat pork or drink alcohol, but she can still have friends who do. For instance, Sophia wears batik, an Indonesian dyed cloth, as part of her fashion and way of honoring where she was born and who she is.

How has it been for you as a Muslim woman wearing a hijab in Seoul?

I’m really interested in languages, so I am learning both Japanese, which is really hard, and Korean, a little easier. People do look at you when you are walking or on the bus. There’s a perception that Koreans are pretty racist, but that hasn’t been my experience. I was in the gardens the other day, when it was quite hot. Some Korean women came up to me concerned that I would faint in the heat. I explained to them that my clothing is cotton, so I was just fine.

How does your faith influence your writing?

As a Muslim and a writer, I strive to make myself and the world better every day. I want to contribute to making the world better. Even though I’ve published more than 60 books, I feel like I can still write better.

Can you share your thoughts about #ownvoices and what is happening in Indonesian writing for children?

There is not yet a strong sense of expanding the kind of writers publishing for children. But, for about 2-3 years, there has been “Room to Read,” founded in San Francisco. That project has a goal to improve literacy and gender equality in Africa and Asia, including Indonesia. One of their efforts is to gather Indonesians writing children stories, train them and try to help some works get published. They are especially interested in stories that have a unique background, unique setting, and unique storyline.

The post Serious in Seoul appeared first on .

May 8, 2019

“Lost” in middle-grade awesomeness

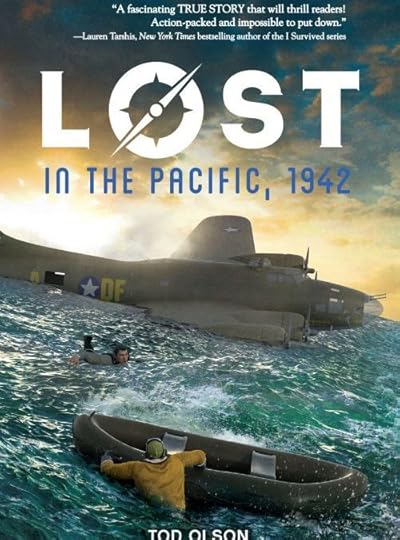

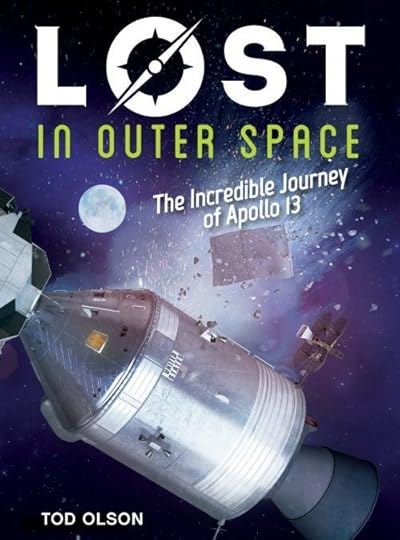

Tod Olson’s “Lost” series of real-life tales of people fighting their way back from almost certain disaster is catnip to young and old readers alike. If, like me, you are a sucker for a good Arctic (or Antarctic), ocean, or deep-in-space tale, these are wonderful immersions in stories you may have thought you knew, but can still be surprised by. Often, Olson gets those tiny details that reveal how disasters happen. For instance, I didn’t realize that Apollo 13, which almost didn’t come back from the Moon in 1970, actually launched with the defect that almost cost the three astronauts their lives. Olson’s stories are accompanied by wonderful photos. This interview was originally published in Wild Things, a VCFA-WCYA blog.

Tod Olson is author of the historical fiction series How to Get Rich and the narrative nonfiction series, LOST. He holds an MFA from Vermont College of Fine Arts, and lives in Vermont with his family, his mountain bike, and his electric reclining chair.

Tell us about your book. Where did the inspiration for writing this book come from?

Winter in Vermont (I live 10 minutes from VCFA) is neither long enough nor harsh enough so I needed a project that would stretch it into a year-long ordeal. A painful battle to survive in a frozen wasteland with no end in sight, it turns out, is a good allegory for the writing process. I could not, unfortunately, find a source for penguin steak or fried seal blubber.

This is part of a “Lost” series. What started you on that idea?

When I was about 11, I was on vacation in Maine and discovered the book Alive, the nonfiction account of the Uruguayan rugby team that was stranded in a remote location in the Andes after their plane went down. For anyone who doesn’t know the story, they eat the dead bodies of their friends and family in order to survive. I can’t remember if I knew this before I picked up the book, but I barely left my chair for two days until they staggered out of the mountains. With the Lost series I wanted to recreate that reading experience for kids, to try to write nonfiction that is every bit as riveting as a good novel. Steve Sheinkin talks about getting kids’ nonfiction out of the health food aisle. I think we can do that if we write as storytellers first and educators second.

What attracted you to Shackleton’s doomed voyage to the Antarctic?

Aside from the fried seal blubber, it was the sources. Most of the officers and scientists and a couple of the seamen kept diaries throughout the 18 months they spent stuck on the ice. Most of the diaries are unpublished and located in England or Australia, but I reached out to a couple of Shackleton writers who shared their transcripts with me. I had seven or eight day-by-day accounts of the ordeal, and I organized my notes into a chronology full of observations from each of them. For better or worse, it felt like I was on the ice with them while I was writing. The expedition also had a photographer, Frank Hurley, whose job it was to provide visuals for a lecture tour when they got back. His photos are probably the most detailed visual record of a survival story ever created. They were so important to the expedition that he dove into six feet of freezing cold water to salvage the negatives as the ship was getting crushed in the ice.

Frank Hurley

Frank HurleyWere there any unexpected hiccups along the way to this great series?

I find that at some point in the process for each book, some reason emerges why the book is impossible to write. For the first book in the series that point came when I discovered that starving men stranded in rafts don’t actually do much of anything except lie around complaining about the salt water boils on their butts. For the second one—Apollo 13—it turned out that most of the drama lay in esoteric technical problems like using the Earth’s terminator to align the spacecraft’s navigation platform. I think it’s Annie Dillard who has the most helpful advice for handling these crises: You write the book anyway.

Tell us a little bit about your background before VCFA, and how you came to decide to enter the program.

After college I went to grad school to be a history professor. I dropped out after a year, thinking I wanted to tell stories instead of debate all the Big Ideas you have to tackle to get a PhD. I ended up as an editor in Scholastic’s magazine division and never entirely left the Scholastic orbit, even after moving to Vermont. I wrote magazine feature stories, produced nonfiction videos, developed book collections as an independent packager, edited school library books, etc. And finally I realized I wasn’t really doing what I wanted to do when I left grad school. VCFA was a way to push myself into it. And the commute wasn’t bad.

What year did you graduate from VCFA and what was your class name?

I graduated in ’05, which was long enough ago that I’m only mostly sure when I say that our class name was the Multiple Viewpoints. I think it seemed like the only choice after we spent hours failing to agree on another one.

Was there one lecture in particular that you can recall an a-ha moment that reinforced that you belonged in the program?

No, but I immediately fell in love with workshop. I’ve always loved the process of trying to meet a piece of writing on own terms, figure out what it’s missing and articulate it. I completely buy what we were all told—that the practice you get critiquing other people’s writing is so much more important than the feedback you get on your own. The problem is that telling other people what to do with their writing is a whole lot easier than revising your own.

Could you talk about your experience in lectures or during your semester work with advisors and how it may have shaped the writing life you are living now? What about VCFA affected your career and where you are now?

Most immediately, I had Marc Aronson as a workshop leader during what I think was his only semester at VCFA. We had some common interests and ended up collaborating on my first trade books, an odd series of illustrated historical fiction called How to Get Rich. We packaged the series ourselves for National Geographic. The process of working with an illustrator and designer was incredibly fun. Less concrete but maybe more significant in the long run was the way my four advisors modeled variations on an approach to writing—a deep, lasting commitment to the words on the page and a conviction that each and everyone matters.

Do you have any VCFA connections that affect your career right now?

I taught a workshop at Highlights last fall with my great friend Leda Schubert, who was a year or two ahead of me at VCFA. I’ve collaborated with Marc on a couple other projects since I met him there. I got a great shot of inspiration two years ago from the Loon Song retreat in Minnesota, organized by my classmates, Debby Edwardson, Jane Buchanan, and Maura Stokes. Great faculty, great conversation, kayaking. You should go!

What would you say to potential students or current students who are hoping to further their writing career?

The same thing VCFA teaches: Don’t worry about your social media platform or what editors are looking for or what’s on the bestseller list. Just write.

What’s coming in the future for you and your writing life? Please let us know about any events coming up where readers could come see you.

I have a standalone nonfiction book coming out in Spring 2020, about the race to climb K2 in the ‘30s and ‘50s. After five nonfiction survival books, every sentence feels like I’ve already written it. So I’m going back to a steampunky adventure novel I haven’t looked at in five years. I’m also trying to do more teaching. Leda is ditching me as a partner, so I’m doing a nonfiction workshop with Steve Sheinkin at Highlights in March 2020. Come join us!

The post “Lost” in middle-grade awesomeness appeared first on .

May 1, 2019

Conversation with Tall Poppies

When Kelly Harms pinged me on Facebook to take part in a

conversation about The Bond, my YA

fantasy, I admit I had FEELINGS. Number one, Kelly is a well-published, best-selling writer who gets

rave reviews. Need more? She’s also one of the driving forces behind the Tall Poppies, a group of kick-ass women

writers who know we do best when we uplift each other. The Tall Poppies are

mostly writing for adults, so I felt especially lucky to be invited as someone

who writes for kids.

Tall poppies!!!!

Tall poppies!!!!Kelly was generous, incisive, and threw questions at me like a major-league pitcher. And this was all the day before the release of her new novel, The Overdue Life of Amy Byler (Lake Union Publishing). Plus (and I hope I’m not revealing secrets) she did all of this pool-side as she supervised her son.

Did I mention that Kelly’s bad-ass? Here’s an edited summary

of our chat.

Kelly Harms Wimmer (KH): Tell us about how you came to young adult writing and dystopian fiction! It is a long leap from a Turkish Fulbright!

Robin Kirk (RK): Like many, this is the material I love to read. When my daughter was in middle school, she read The Book Thief by Markus Zusak and insisted I read it. I was transported — this incredible book in the voice of death taking us through Nazi Germany and the life of the orphan Liesl. I began to aspire to write something powerful for younger readers. For me, these are the books that shape who we are. I also love immersing myself in different worlds, even scary ones. I began to play around with stories and The Bond was the result.

The Bond is available through Blue Crow, your local indie and Amazon

The Bond is available through Blue Crow, your local indie and AmazonKH: The Book Thief

changes so many lives. I too was changed by it.

RK: I still think about that book all the time. That’s also the power of kidlit — it tends to stay with you for a lifetime (Charlotte dying in the empty crate! Black Beauty’s friendship with Ginger!) SOB…

KH: What would you be today if your career was chosen for

you at 16? What would you have chosen for yourself? Was writing in the cards

even then?

Robin Kirk (RK): Uf, at 16, total Jane Goodall and George Schaller

(lion researcher and writer) fangirl: wildlife biologist and writer. Then in

college, bad-ass reporter. Much later I wrote a More

Terrible Than Death, a book about human rights in Colombia. My mother

wailed — what happened to living with the chimps and the lions!

Jane Goodall in Gombe

Jane Goodall in GombeKH: Most of our Bloom crowd are fervent readers and know

their way around a beautiful sentence. Do you think there’s a quality that

lends itself to writing for teens rather than adult fiction?

RK: That’s a great question. I think the one thing that may really distinguish writing for young people is story. You have got to grab them and not let go. Adults might luxuriate in character or scene or beauty. Young people will walk away. Alan Cumyn, one of my advisers at Vermont College of Fine Arts (VCFA), called it the cheese sandwich problem. You can’t let your reader start dreaming about that cheese sandwich they can make in the kitchen. They have to be so immersed in the story that they will go hungry.

KH: My first go at YA had a lot of what my mentor called

“potty breaks.” She said, if this is a movie, this is when you’d hit the

bathroom.

RK: One of my VCFA buddies, Jenn Bishop,

did her critical thesis on the use of the bathroom in middle-grade lit — it’s

the place in school where kids have crises or say the deep, awful thing. Important

location!

Jenn’s fabulous book!

Jenn’s fabulous book!KH: And to go deeper, there are mirrors and locks, two

favorite literary devices for people who are coming into their own and

demanding their privacy. Not

so long ago, Literary Young Adult wasn’t actually a publishing business. Some

of the books that I read at that age would never be published today. Do you

think it’s the business that changes, or the young readers?

RK: There’s no question that YA is a recent marketing category. Some of my favorite books from the 1970s and 1980s were never marketed as YA but would be today. I’m thinking of Robert C. O’Brien’s fabulous Z for Zacariah. I also think that YA lit is SO much more diverse than it was when I was growing up. It kind of needs its own category so kids are able to find the books that end up saving their lives. There is, as some of you know, a huge push in kidlit in general for more diverse voices, super-welcome and long overdue.

KH: As a writer from the dominant culture, I thank my lucky

stars for all the stories that stretch my understanding and grow my worldview.

The kids who grow up with an #ownvoices

bookshelf give me huge hope and inspiration.

RK: Matt de la Pena,

who taught for awhile at VCFA, tells a wonderful story about how one librarian

saw this half Mexican teen who only cared about basketball, went to the shelf,

pulled out a book, and said THIS BOOK WAS WRITTEN FOR YOU. It was Alice

Walker’s The Color

Purple. He’s gone on to write many YA and picture books and win a

Newberry.

KH: On that note, will you tell us a fav diverse dystopian

for our to-be-read list?

RK: Mmmmmm so many… Tomi Adeyemi’s Children

of Blood and Bone is spectacular — the next one in the series is due out

soon. I am really loving some of the stories inspired by Japanese or Korean

culture. Rebel

Seoul by Axie Oh, for instance. Forest

of a Thousand Lanterns by Julie Dao. I will read ANYTHING by S.A.

Chakraborty. I listened to City

of Brass on audio book and would have driven another 500 miles to stay

with the story.

KH: Let’s talk about your writerly education a bit more.

There are relatively few Masters programs for young adult fiction writers in

this country, yet they are thick on the ground for poetry and literary fiction.

How did the Masters affect you?

RK: I really didn’t think I wanted an MFA — but I sure needed

it, and I ended up landing in just the right program. Unlike adult programs,

kidlit programs tend to be extremely supportive and very celebratory. So people

try hard to help the students find their voice and when they do it’s PARTY

TIME. I learned to write fiction, really, in that program — and as

importantly, I found my tribe, other writers who support me (and I support

them) as we navigate this crazy business. There are certainly ups and downs.

The VCFA program is low-residency, so I continued to work as I pursued the MFA.

It was GRUELING but I wouldn’t change a minute of it

KH: i have a couple more questions while we still have you!

First, could you give us a longer spiel about The Bond?

RK: I really wanted to twist around some familiar tropes,

especially what family means and how we might make bonds to others in the

future. My heroine, Dinitra, is brewed in a lab, like everyone else in the

Weave, specially made (a familiar trope). But then that’s complicated when

the Sower who made her engineers her escape to a rival society. In Bounty, they

use the same genetic technology (it’s a given in this world). But in the rebel

world, male children are born to be soldiers, obedient to their Captain

mothers. Dinitra really has to struggle to understand what it means to be

herself when she knows she was made to be something that feels wrong. She also

is given a creature to command, a hybrid battle dog named 12. The creature is a

killing machine and protects her — and she learns to love it, creating her

own, emotional bond. I throw many challenges at her, and she has to dig deep to

decide who she is and what’s important to her. Basically, an adventure, where

the stakes are who you save and how you break the bonds of what’s expected and

instead choose to do what’s right.

Katie Rose Guest

Pryal (a Tall Poppy, a fab writer, and my editor at Blue Crow!): Robin, how does your

work at Duke in human rights inform your fiction in The Bond?

RK: This gets heavy! I’ve studied many genocides and one thing unites them — those committing the genocide convince themselves that they are doing the right and necessary thing to save the world (in their twisted logic). In The Bond, the Weave has convinced itself that the world must be protected from men, considered inherently violent. Women, they believe, are more peaceable and collaborative. Their plan is to eventually eliminate all men, again, arguing that this is the best option for the planet. So once they perfect reproduction in the lab — bye boy. I use what I imagine many of us believe (including me), that women would be more peaceable leaders. Really? As a journalist, I used to cover the Shining Path, and women were among their most ruthless killers. The book kind of takes this on in a fictional universe.

KH: What is next for you?

The gorgeous Malaan Ajang

The gorgeous Malaan AjangRK: I’m hoping to continue the story in a second book. This one focuses on the male warrior Dinitra falls in love with despite all she’s been taught. Like her, Fir realizes he’s been built for something he doesn’t want, killing and war. Dinitra helps Fir and his brothers escape – and they have to find their way in a dangerous new world. Dinitra and Fir meet again, but under the worst possible circumstances. And there’s a Bee Queen! My inspiration is Malaan Ajang, this incredible Sudanese model. My first description of her is basically the photo above.

The post Conversation with Tall Poppies appeared first on .

April 26, 2019

The cost of the Throne

After five books (and maybe two more on the way) and seven seasons on television, “Game of Thrones” is coming to an end. Duke scholars have been talking about what attracts them to the story and how they view the show’s themes through the perspective of their scholarship.

I was first up! I think my science fiction novel, “The Bond,” made me an easy target…

Q: Basic question: Why does the show, both in George R.R. Martin’s books and the TV series, appeal to you? Has it influenced your own fiction?

KIRK: Martin is a master world-builder, but the most compelling elements of his story are the characters. From the misunderstood, wickedly smart Tyrion Lannister to the scheming Margery Tyrell and the vicious Hound, he draws us into a familiar story by how these characters adapt and change to meet a seemingly impossible challenge. In contrast to a fantasy master like J.R.R. Tolkien, whose characters are less complex, Thrones characters have the stink and weight of the real.

Q: Could you pick a theme that is important to you and talk about why it works in the show, but also how its portrayal should be interesting to us in contemporary life?

KIRK: Martin’s story is eternal — what do people do when faced with the promise of power? Will they try to grasp it to benefit themselves — Cersei Lannister — or try to do good — Danaerys Targaryen? And what happens when those impulses start to cost them? I think that’s a perennial question that fascinates us.

There’s a story parallel between Thrones and House of Cards, which, boiled down, is really the same story. I’ll leave it to viewers to trace out the parallels between King Joffrey and any other modern-day head of state!

Q: Your own scholarship has reflected a lot on torture, terror and human rights abuses, all of which are prominent in the show. Do you think GOT deals with these issues honestly? Does it reflect anything about our ability to act on these issues, positively or negatively?

KIRK: I skipped through Ramsey Bolton’s torture of Theon Greyjoy. Torture as entertainment: not my thing. But I do think the question of rights in Game of Thrones is very interesting (and I’m working on a class that would examine rights through the lens of fictional worlds).

“Science fiction and fantasy writers have always played with what happens in alternate systems slightly or greatly different from our own, and that does allow us to think about our current challenges and what rights we could develop.”

Science fiction and fantasy writers have always played with what happens in alternate systems slightly or greatly different from our own, and that does allow us to think about our current challenges and what rights we could develop. H.G. Wells, author of The Time Machine, wrote The Rights of Man in 1940, partly in response to World War II. Some of his ideas helped inform the drafting, eight years later, of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, among other things.

Q: The big question: Who do you think will end the series on the throne? Who do you hope ends on the throne?

KIRK: Ha! No one ever won anything underestimating George R. R. Martin’s ability to shock us. If I wish the best for the people of Westeros, I say Tyrion. But Martin is not an author who seeks to hand out easy endings. By the look of the trailer, at least Gendry has stopped rowing.

The post The cost of the Throne appeared first on .

April 25, 2019

Letters to a King

Mexico recently sent a letter to the Spanish king requesting an apology for atrocities committed during the Conquest five centuries ago. Spain quickly dismissed the letter as an attempt to judge the past by modern mores. One outraged pundit wrote, “You cannot judge the events of 500 years ago through the prism of 2019.”

The basis for the request is a Spanish adventurer, funded by the crown, violently toppling the Aztec empire and causing untold thousands of deaths. More lethal were the diseases Hernán Cortes and his men carried, including small pox. Historians speculate that the deadly virus actually burned south ahead of them, felling the Inca emperor Huayna Capac before any European ship landed in modern-day Peru. The Inca’s death touched off a fratricidal struggle that ended with one son killing the other. Spaniard Francisco Pizarro executed the victor in 1533, even though his followers collected huge mounds of gold for ransom.

Mexican President Andrés Manuel López Obrador’s letter was not the first sent to a Spanish king to protest the Conquest’s horrors. Even at the time, some judged Spain’s actions publicly and harshly. Critics were a minority, to be sure. Many fortunes were made — and lost — pillaging the region’s riches.

But it’s a mistake for Spain to attempt to elude this request by pretending it is based solely on contemporary mores.

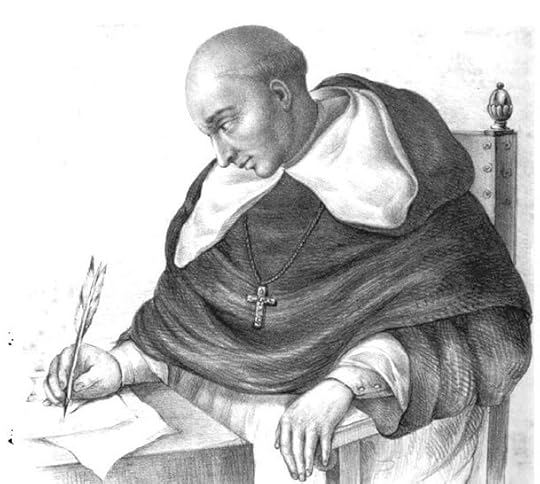

Among the best-known critics was an insider, Spanish priest Bartolomé de Las Casas. Born to a Sevilla merchant family, De las Casas arrived on the island of Hispaniola in 1502, 19 years before Cortés’s victory. De las Casas’s family owned land on the island and with it the indigenous people living there.

Fray Bartolomé de las Casas

Fray Bartolomé de las CasasDe las Casas witnessed atrocities first-hand, including massacres and the brutal treatment of people forced to mine for coveted gold. By 1515, he was penning pleas to Spain to avoid violence and enslavement. He was by no means “woke.” Reflecting widespread acceptance of slavery, he for a time advocated importing African laborers, considered hardier then natives. But he eventually abandoned that idea, arguing that all slavery be abolished.

Among his many works, De las Casas’s “In Defense of the Indians” stands out. In it, De las Casas chronicles horrors that read eerily like modern human rights reports. He shows an advocate’s ear for the most compelling examples of evil. In one passage, De las Casas recounts how conquistadores targeted women and children, snatching “young Babes from the Mothers Breasts, and then dasht out the brains of those innocents against the Rocks; others they cast into Rivers scoffing and jeering them, and call’d upon their Bodies when falling with derision, the true testimony of their Cruelty, to come to them, and inhumanely exposing others to their Merciless Swords, together with the Mothers that gave them Life.”

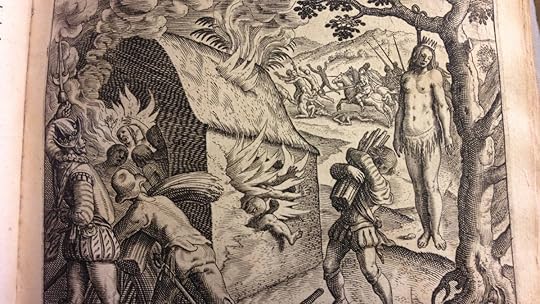

The images below are of a 1698 edition of De las Casas’ Relation des Voyages et des Découvertes que les Espagnols ont fait dans les Indes Occidentales, bound in bone and in Duke University’s David M. Rubenstein Rare Book & Manuscript Library

These appeals won mild reforms. One papal bull, Sublimis Deus, proclaimed that natives were human and should not be enslaved or robbed. In 1542, Spain promulgated laws abolishing slavery and the plantation (encomienda)system, with decidedly mixed results.

Another letter writer, Felipe Guamán Poma de Ayala, was a native, born just after Pizarro’s victory over the Inca. He likely learned Spanish from priests and officials. For some reason, Guamán Poma was banished from his home province, and he embarked upon a journey through a Peru still torn by violent occupation.

It was then that Guamán Poma — the Quechua translation is “Falcon Cougar” — began writing what came to be “The First New Chronicle and Good Government,” a 1,189-page letter that includes 398 full-page line drawings. Meant for King Philip III, the text is in Spanish with some Quechua. Much of the letter is Guamán Poma’s account of Inca history and customs, to support his central argument. He didn’t argue for reform of the Conquest. He argued powerfully that the Conquest itself was wrong and that Spain should withdraw and treat Peru as an equal.

When I teach these two authors in my human rights classes, I point out how they can be seen within an age-old debate over how to best pursue change. Are you a reformist who advocates, like De las Casas, for gradual change? That strategy was later adopted by anti-slave trade campaigners as well as modern-day death penalty abolitionists, who chip away at abuses over many decades.

Or are you, like the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, unwilling to wait any longer? Reading “The Letter from the Birmingham Jail” along with Guamán Poma’s Chronicle underscores the stark difference between how allies and how victims of abuses can approach change.

In the book, Guamán Poma depicts himself presenting his masterpiece to the king. Sadly, there’s no evidence the king ever received it. The stack of yellowed, cracked pages was only rediscovered in a European archive in 1908. Perhaps some noble promised the earnest Peruvian that they would personally deliver his life’s work. Likely, it was sold and resold as an oddity.

You may side with Guamán Poma’s passionate rejection of the Conquest, but De las Casas — a Spaniard, priest and white man — had more positive impact on curbing abuses. On the other hand, the priest’s advocacy of gradual change left the deep and persistent scars President López Obrador wants Spain to acknowledge.

During a visit to Madrid several years ago, I eagerly raced through the magnificent Museo Del Prado to see how this grand culture viewed its Latin American brethren. I left disappointed. I located a single painting, some Spanish nobleman surveying a Panamanian inlet. Even as Latin America looks to Spain as a touchstone, Spain’s gaze seemed to be to Europe or inward, to its own tangled history.

When I conveyed my disappointment to a Peruvian friend, he snorted, “We were there. You were looking in the wrong place.”

Had I missed a room? An exhibition?

“What color were the frames?” he asked.

“Gold,” I answered.

“And where do you think they got that gold?”

From the Museo del Prado

From the Museo del PradoOf course, the mound collected in return for the Inca’s life. Remorseless, Pizarro slit his throat and sent the spoils to Spain.

Whether we acknowledge it or not, the past frames our present and shapes the future. The Conquest’s scars will never go away. But by apologizing, Spain can help reframe its relationship to Mexico and the rest of Latin America for the better.

Maybe the spirit of Guamán Poma’s letter will finally help convince the Spanish king.

The post Letters to a King appeared first on .

February 3, 2019

Fear-mongering with caravans

Every morning, Merriam-Webster sends a word to my email inbox along with its definition and history.

Some words are worthy of a college test. Recently, I learned that “crapulous” means the feeling after overindulging in alcohol, not — well, not that other thing.

Often, the social media-agile dictionary features words linked to the news of the day (nationalism, quorum, nepotism, rogue).

Courtesy USA today

Courtesy USA todayOne word I haven’t been sent yet is “caravan.” The medieval origin — in Italian, caravana, or from Persian, kārvān — evokes cross-desert treks, laden camels, tales of the Silk Road. The word also brings with it the idea of danger. To protect their lives and goods, traders grouped in caravans.

So the use of “caravan” to describe yet another group of people heading toward our southern border with Mexico to seek asylum is appropriate.

Most are families with children, according to human rights monitors. They face more than danger on the trek itself. Many are fleeing their homes because they know they or their children risk harm or death if they remain.

Ironically, the country they’re fleeing to, the United States, is also an important cause of their plight.

During the Cold War, Americans supported murderous dictators throughout Latin America. Starting in the 1980s, we decided to “fight” our own use of marijuana, cocaine and heroin not by addressing consumption, but by pointing the finger south at the suppliers. That approach, often called the “War on Drugs,” has failed spectacularly.

According a UN report released in 2018, our policies have unleashed “a decade of fruitless carnage, where millions of people have been murdered, disappeared, or internally displaced amid a blizzard of overdoses, spiraling addiction, executions, extrajudicial killings and incarceration… on almost every measurable level, this war on our own citizens has abjectly failed. Drug use and drug deaths have risen. Drug production has rocketed. Organized crime groups continue to use the drug trade as a vital supply line of cash.”

These organized crime groups, fed by our own addictions, have torn apart countries like El Salvador and Honduras. That country’s capital, Tegucigalpa, is considered “the most dangerous capital city in the world without a declared war,” one journalist recently wrote.

Instead of facing up to our poison legacy, the White House is choosing scare-mongering: according to Merriam-Webster, needlessly raising or exciting alarm. This is especially frustrating because the ones who are afraid — legitimately afraid — are these migrants who have banded together in a caravan precisely because of the threats they face as they journey.

So why has this president — and his Fox echo chamber — made the caravan into such a fearsome prospect? At first glance, it’s hard to justify. In 2016, the last year for which data is available, the Department of Homeland Security estimated that almost 75,000 Central Americans and Mexicans applied for asylum. These applications were handled through normal procedures and represented no threat to either our government or residents on the border.

All of the caravans that have reached the border so far represent less than a tenth of that number. As asylum seekers have arrived, there’s been no spectacular increase in crime, poverty, or generalized disruption of any sort. To the contrary, these newcomers do what most arrivals have always done. They enroll their kids in school, rent apartments or buy houses, get jobs, pay taxes, attend church, and start businesses.

They go to baseball games. They shop. They stroll the parks on Sunday.

What’s really happening in Washington is all too obvious. We’re being told to be afraid, to be very afraid, and then make political decisions based not on reason or facts, but on fear. We’re being indoctrinated, in other words, screamed at to believe what is essentially a lie.

I’d call it crapulous, but only after several shots of Kentucky’s finest.

The post Fear-mongering with caravans appeared first on .