Nichole Louise's Blog

November 4, 2025

Review: Daughters of Nicnevin by Shona Kinsella

Daughters of Nicnevin by Shona Kinsella reimagines the 1745 Jacobite Rebellion in Scotland through a historical fantasy lens. While it is true that many women and children of the Highlands were left to farm, subsist, and defend their homes and villages after many Jacobite soldiers were killed in battle, executed, or taken prisoner by government troops, Kinsella poses the “what if” magic could help these people survive? Enter natural witches Mairead and Constance, women from two very different backgrounds. Mairead is a lone wolf drifter, moving from village to village as a healer to avoid detection and persecution. Constance, on the other hand, has repressed her natural power by following the conventions of the time: get married, have children, keep house.

Constance life is drastically and irrevocably changed when Mairead arrives in her village just outside Inverness, Mairead having felt a strong pull of magic Constance didn’t know she was giving off. Constance and her children have been making ends meet while Constance’s husband, Iain, is off fighting with the Jacobites–a position nearly all the women in the village are in. Mairead befriends Constance, first working as a housekeeper and nanny but soon forming a deeper relationship with Constance. Ultimately, through Mairead, Constance awakens a part of herself long repressed and goes on a journey of self discovery that is both empowering and self-destructive (and harmful to those around her.) With the help of Witch Goddess Nicnevin, Mairead and Constance magically create the “Albans,” or men made from earth animated for manual labor and protection of the village against government soldiers.

I found magic, and its relationship to both Mairead and Constance, to be an allegory for sexuality. Where Mairead has always embraced herself and her truth, Constance has repressed it. The deviation, however, comes when Constance’s magic continually harms people, even Mairead. I viewed the romantic relationship between Mairead and Constance to be rushed and stilted; I never really “felt” it, but maybe the reason for that is the reader’s discovery of Constance using her magic for manipulation. Constance does a series of not-so-great things, but still we’re made to believe that Mairead and Constance should end up together. In my opinion, the relationship was not healthy and Mairead should have left!

DoN has a great, creative premise, but ultimately it fell a bit short for me and felt like something was missing.

October 24, 2025

Review: The Manningtree Witches by A.K. Blakemore

The Manningtree Witches by A.K. Blakemore follows Rebecca West during the 17th century witch hunt craze in England, spearheaded by “Witchfinder General” Matthew Hopkins (again, I couldn’t help picturing Vincent Price given his film.) Similar to Margaret Meyer’s The Witching Tide, the women of Manningtree are one by one accused by Hopkins and his associates of witchcraft. Having read not only The Witching Tide, but also the non-fiction Ashes and Stones, I found myself quite familiar with the this world and its methods of finding, inspecting, and punishing women for their alleged witchcraft. That said, it’s still a topic I can and will continue to read about.

Rebecca West sees a curious white hare, thinks she sees the devil in her friend’s water bowl, experiences fantastical and erotic dreams, has an all encompassing infatuation with the man who is teaching her to read and write–all these parts make the whole of her suspicion, and not necessarily fear but fascination with the prospect that she may indeed be stalked and influenced by the devil. But when Rebecca, her mother, and a few other village women are arrested and thrown in jail, her outlook begins to change. Blakemore gives an accurate, albeit brutal, account of how women were strip-searched by strange men for any mark upon their body that could be considered a teat from which they suckled their imp or familiar. West and the Manningtree women are treated worse than animals, stuck in a pitch dark cell with little to no food, lice and vermin abound, overflowing bathroom bucket, and on top of this they are periodically taken out to be compelled to confess to the Witchfinder General Hopkins.

West, at her mother’s encouragement, seizes the opportunity to save herself by effectively playing the system. Again, having just read true accounts in Ashes and Stones, many accused women did indeed offer vivid and fanciful confessions if only for the reprieve from torture, but also there is no doubt their words were influenced by delirium or hallucinations brought on by malnourishment, dehydration, and prolonged solitary confinement. Blakemore presents us with a world unscrupulous in its brutality (physical and psychological), objectification, and othering of women. I need not state the obvious in its parallels with today’s world.

A.K. Blakemore’s prose is gorgeous and creative. Her unique wording, descriptions, and explanations are a vivid feast (if at times perhaps too enthusiastic with the thesaurus, which some may find irksome.) Overall, The Manningtree Witches is one part social history, one part historical fiction, one part social / gender commentary. Blakemore’s talent as a writer in crafting unique turns of phrases is stunning. I can’t wait to read The Glutton!

October 19, 2025

A new short story from the world of Raven Rock…

Click Me!

Click Me!This story, the original legend told from the perspective of Katrina Van Tassel, has been in the back of my mind since I wrote Raven Rock. In fact, some of the ideas in this story were in Raven Rock‘s original epilogue. Ichabod Crane’s blatant desire for acquiring the Van Tassel wealth through Katrina always stood out to me. The fact that Katrina is also described as a “coquette” and as being fickle in allegedly pitting Ichabod and Brom always made me wonder about Katrina’s point of view. The original legend, after all, is written by a man. So what might have Katrina, a young woman of 1790, have had to say in the face of such perceptions and accusations? While Irving wrote Ichabod as presumably harmless with his gawky nature, Ichabod Crane always read to me as, quite frankly, entitled and brazenly covetous (I know this is partly the point of his character.) The following passage taking place at the end of the “frolic”, intrigued me:

Ichabod only lingered behind, according to the custom of country lovers, to have a tête-à-tête with the heiress; fully convinced that he was now on the high road to success. What passed at this interview I will not pretend to say, for in fact I do not know. Something, however, I fear me, must have gone wrong, for he certainly sallied forth, after no very great interval, with an air quite desolate and chapfallen.

So, what exactly happened that did not go Ichabod’s way?

If you’ve read Raven Rock, you will find All Hallows’ Eve Frolic aligns with its plot threads and character arcs. If you haven’t read Raven Rock, All Hallows’ Eve Frolic will provide an alternate take on The Legend of Sleepy Hollow, as well as provide a tease for Raven Rock without (hopefully) revealing too much.

Happy Halloween and enjoy this Spooky Season!

-Nichole Louise

October 14, 2025

Review: I Am Cleopatra by Natasha Solomons

I Am Cleopatra by Natasha Solomons follows teen to young adult-aged Cleopatra contending with the threat of Rome. When the Pharaoh, Cleopatra’s father, dies and Rome sets its sights on Alexandria, Cleopatra takes stock of her country’s leadership and well-being. As is the historical practice of the Ptolemies, Cleopatra is married to her brother. Her two younger siblings, a girl and a boy, are caught up in the political tensions. Knowing she must solidify her position and the country’s safety, Cleopatra allies herself with the famous Julius Caesar. Cleopatra quickly ingratiates herself with the powerful Roman, fresh off a civil war, pushing down deep her true desires and opinions to sacrifice her body to his pleasure and whim. The reader knows Cleopatra does not love him and is fully aware he has plundered Egypt, yet she “plays the game” for her country.

We also get a few chapters from the perspective of Servilia, on and off again lover of Caesar and mother of the infamous Brutus. I understand the author’s reasoning to have a Roman perspective in this story, but there weren’t enough Servilia POV chapters for it to warrant as a dual POV novel. Servilia has a handful of chapters, which this reader actually found jarring and a bit out of place–especially considering this book is titled I Am Cleopatra and is written from the first person perspective as a type of memoir.

There were a few things that did not sit right with me in this rendition of Cleopatra’s life. While at first Cleopatra is “grinning and bearing it” with her relationship with Caesar, often noting her disgust with his physical body and his behavior, she in time grows to have true affection for him. Not love, but enough affection to miss him. I could understand, perhaps, a mutual respect in playing a political game, but I did not like the Stockholm Syndrome of it all. The big event at the end seems like it should have had more emotional impact because of their enmeshment, but I just did not feel it.

What’s more, Cleopatra herself is not necessarily likeable. She is the product of her time and high social standing, therefore having life-long loyal slaves is her norm. Her close friendships with her slaves will not sit well with modern readers, however Cleopatra’s inner thoughts on this matter aren’t really redeeming. She is often selfish and entitled, even cruel when family members approach to buy the freedom of one of them.

Given where in the timeline this book ends, there is still much more of Cleopatra’s life to cover so I would not be surprised if the author plans to write a sequel or trilogy.

I Am Cleopatra will be released October 21, 2025

October 11, 2025

Review: Vlad The Last Confession by C.C. Humphreys

Vlad: The Last Confession by C.C. Humphreys is a historical fiction account of 15th century Vlad Dracula, Prince of Wallachia–or as most know him, Vlad the Impaler. The tale is framed by confessionals told in 1481 from those closest to Vlad, his former lover, his best friend, his confessor, who witnessed his lows and highs many years before. Humphreys then takes us to Vlad’s adolescence as a hostage in Turkey, very much under the yoke of the Sultan Murad and his son, Mehmet. Vlad, his younger brother Radu, and Vlad’s best friend Ion navigate the challenges of the Sultan’s court as students and outsiders, always at odds with their “hosts.”

Vlad’s time as a hostage at the Sultan’s court is only the start of his miseries, which are compounded when he frees a young woman, Ilona, from a life of serving as a harem mistress. Ilona, who I believe is a fabrication of the author and not based on a real historical figure (?), then flees to Wallachia to await “her Prince” for whenever he is able to escape the Sultan. While Radu is taken to, for lack of a better word, be groomed by Mehmet, Vlad is thrown into the dungeons of Tokat as punishment for freeing Ilona. It is within the walls of Tokat that Vlad is forced into a sort of “training” in the art of torture and pain. While he is resistant at first and highly disturbed by the torture methods, especially the impalement, his traumas slowly engulf him.

When Vlad does make it back to Wallachia, and to Ilona, he is a changed man. No longer the youth full of hope and idealism, but a traumatized and broken man. What I really appreciated about Humphreys’ take on Vlad is that he wasn’t just “evil” for evil’s sake with no reason. Rather, Humphreys crafts a complex psyche heavily impacted by what I interpreted as PTSD, to account for Vlad’s violent and harsh behaviors. He is the monster they–the warring boyars and kings and sultans and torturers–made him. He is trauma manifest.

Due to his complex psychological state, I vacillated on my views regarding his relationship with Ilona. While at times she was his one true love, his only refuge of honesty and peace, Ilona seemed to always view him with caution. While he was also her true love, she also recognized the darkness within him–the line he always seemed to be walking. She was also well aware of him sleeping around, which was a little hard for me to understand. As such, she handled him with the cautious reverence Vlad himself had for his beloved trained goshawks. While this dynamic was clearly not healthy, Ilona loved him no matter what–even to her own ruin.

Readers will find no vampires or magic here, but a brutal and gory account of the tumultuous life of this 15th century Prince of Wallachia. Humphreys even offers real world explanations for Vlad’s supposed longevity from which legends grew. And in the end, we find Vlad’s masterful machinations work to his favor.

September 29, 2025

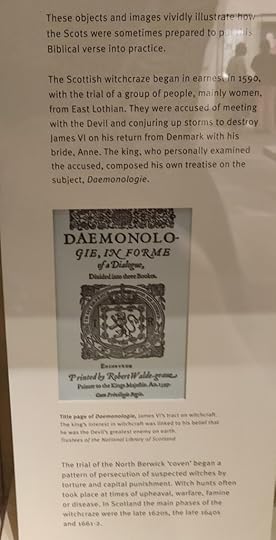

Review: Ashes and Stones by Allyson Shaw

Ashes and Stone by Allyson Shaw is a creative non-fiction account of women accused of witchcraft throughout Scottish history, particularly in the 16th through 18th centuries. Shaw details her personal journey traveling around Scotland to visit the forgotten, often neglected monuments to the those who lost their lives to witchcraft craze. Reading Ashes and Stone while I was traveling around Scotland, knowing exactly some of the areas Shaw spoke about and being able to visualize and physically place myself in those spaces, enhanced my reading. Shaw notes that many of the monuments, large or small, often held/hold language that wasn’t/isn’t exactly respectful to the actual human souls lost and the absolute brutality against women. Shaw describes the implements of bondage and torture used against women (as seen in the National Museum of Scotland, my own pictures below) who perhaps did not follow society’s script perfectly, singling them out as “easy targets” for persecution in a powder keg of battling Protestants and Catholics.

Descriptions of Scottish witch hunts in Scotland – National Museum of Scotland

Descriptions of Scottish witch hunts in Scotland – National Museum of Scotland

Collar and manacles used in imprisonments and torture – National Museum of Scotland

Collar and manacles used in imprisonments and torture – National Museum of Scotland

Full display of torture and imprisonment devices used in the witch hunts – National Museum of Scotland

Full display of torture and imprisonment devices used in the witch hunts – National Museum of ScotlandAs the author goes through each geographic area’s witch hunt story and those persecuted, she draws parallels to the violence and brutality against women then and women now. Her descriptions of these acts, taken from primary sources and in some cases womens’ own “confessions”, are stark in their honest and barbarous truth. Shaw also discusses the common themes of men in power using their status to fulfill their sick and twisted desires of enacting violence, and sexual violence, against women.

Ashes and Stones is both an interesting and hard read knowing these harsh truths of history persist today in both different and similar forms. Scotland in the 16th through the 18th century created the “perfect storm,” so to speak, for the witch hunts given the religious and political turmoil. Men using their positions of power and social prestige to control, imprison, torture, and kill women are still seen in today’s world–often will little or no consequences. Have we really come so far?

August 29, 2025

Review: The House of Two Sisters by Rachel Louise Driscoll

The House of Two Sisters by Rachel Louise Driscoll (titled Nephthys in the UK) follows Clementine “Clemmie”, daughter of a famed Victorian Egyptologist and “mummy unwrapper.” Clemmie ventures alone to Cairo to return one of her father’s (pilfered) artifacts that Clemmie believes has cursed her family. (Read into that the colonialism and superstition as you will.) Clemmie’s journey down (up?) the Nile to find the best place to return the artifact amulet is inter-spliced with flashback chapters from 1887 recounting Clemmie’s witnessing of one of her father’s “unwrapping” parties. While Clemmie instinctively finds the “fad” wrong and disrespectful, she cannot stop her father from reveling in his guests’ reactions to the mummy he has uncovered: conjoined twins. Although Clemmie begs him to stop, her father goes as far as to physically cut the twins apart.

The parallels between the sister mummies and the relationship between Clemmie and her own sister, Rosetta “Etta,” are beyond evident. Etta’s mind begins to unravel, setting Clemmie in motion to venture to Egypt to return the twins’ amulet. While abroad, however, Clemmie’s plan does not go according to her desire–this wouldn’t be a story if it didn’t! She teams up with English tourists, siblings Celia and Oswald, as well as the slightly suspicious and almost too curious Rowland. Clemmie is coerced into taking a boat with them down the Nile. Though her main objective is sidetracked, her journey ultimately leads to uncovering a grander scheme that speaks to British colonial exploitation of Egypt and her history. Colonialism is an important topic to discuss when writing a story about the English in 1890s Egypt, and though we read the story through Clemmie’s eyes, Egyptian Mariam is a stand-in for the Egyptian perspective. She serves as a sort of reality check for Clemmie, but her role as a character isn’t fully developed beyond a few lines of description speaking to her and her father’s greater purpose in preserving and protecting Egypt’s history. Although an Egyptian character, she isn’t given enough “screen time” in this story of Egypt.

The House of Two Sisters started in an engaging and descriptive way that made me want to know more, however as the story progressed, the writing became more of a summary of events. What’s more, the author often drove too on the nose points home. Perhaps these choices were at the request of an editor or publisher, as readers are not often given enough credit for being smart or perceptive enough to pick up on nuance.

August 25, 2025

Review: Boudicca’s Daughter by Elodie Harper

Boudicca’s Daughter by Elodie Harper is the author’s first book after the completion of The Wolf Den trilogy (one of my favorites.) Many may know about the famous Iceni warrior Boudicca who led a rebellion against Roman invaders, but little is known about her two daughters beyond the Roman accounts. History tells us that Boudicca was flogged by the Romans while they raped her daughters. Boudicca commits suicide, but what of her daughters?

Harper follows Solina, one of the daughters, in the warfare leading up to Roman defeat of the Iceni and her subsequent life in Roman captivity. The first part of the novel explores the dynamic between Solina and her mother, sister, and father. These relationships are often fraught with miscommunications and strong ideals of honor and protection of family. I found this first part to be the strongest because we see Solina in her natural state, so to speak, embracing her true identity. We also get the perspective of Boudicca (real name Catia), which offers interesting insight on how she views her daughters and husband.

Enter Roman general Paulinus, the legate of Britannia who conquers the Iceni and takes Solina, now seemingly the sole survivor of her family, into captivity. Paulinus raids the remaining Iceni settlements and takes the relics of Solina’s people for Rome’s treasure. Paulinus humiliates Solina, as well as forces her to execute one of the last surviving members of her extended family. As such, I think any reader–myself included, would be extremely put off by the budding “romance” between Solina and Paulinus.

Solina seems to develop Stockholm Syndrome with Paulinus, at first seducing him as a means to manipulate him and possibly free herself, but later she seems to develop genuine affection for him. As Solina and Paulinus eventually make it back to Rome, Solina is given to the Empress as a slave. Paulinus, once her captor and destroyer of her people, is unfortunately Solina’s only salvation.

I was excited for this book because I loved the Wolf Den trilogy, as well as the history of Boudicca, but the Stockholm Syndrome “romance” between the two main characters and the obvious exploitation of power dynamics never sat well with me. Despite the author’s attempt to make Paulinus sympathetic, I was never on board with their relationship. I kept hoping Solina would exact revenge upon him, but the story and their relationship in fact goes in the entirely opposite direction. I felt that Solina’s life in Rome, the life she builds with the man who took everything from her and her people, was so antithetical to Solina as a character. While Solina struggles with this dichotomy throughout, the ending the author provides is sadly not one that will satisfy many. What’s more, the summary of information concerning the political state of Rome in the later chapters was confusing and rushed. Ultimately, everything about the “romance” felt wrong to me and unfortunately soured my reading experience despite the author’s writing skill.

Boudicca’s Daughter will be released in the US on Sept. 2, 2025

August 18, 2025

Review: The Huntress by Kate Quinn

The Huntress by Kate Quinn opens in 1950 Boston where Jordan McBride must contend with her mysterious new step-mother, Anna. Jordan’s love of and talent for photography expose a darker side of Anna, causing Jordan to try to dig deeper into Anna’s cloaked past. Meanwhile in Vienna, English journalist Ian Graham and his associate Tony are still hunting Nazi war criminals. One Lorelei Vogt, known as The Huntress, is on their list and is suspected to have fled to the US. And then there’s Nina, the former Soviet Night Witch turned deserter who married Ian during the war as a way to safely immigrate to England.

Nina was perhaps the most engaging and interesting part of this story. As The Huntress is told in a non-linear fashion, we get flashback chapters of Nina before and during the war; her pilot training, the forming of the Night Witch bomber squadron, Nina’s relationship with fellow pilot Yelena, and her ultimate defection from Soviet Russia after her father speaks ill of the government. Nina’s personality and charm leap off the pages, leaving the other characters muted in her wake. For example, the 1950 chapters with Jordan in Boston seemed modern, out of place, and slightly disjointed from the rest of the story.

While The Huntress was an entertaining read, I kept wanting to know more of Lorelei Vogt’s backstory and motivation. We get glimpses via the clues the characters uncover, but we never really get a real motivation or reason from The Huntress herself, which makes her kind of flat and unconvincing with no real arc.

While The Diamond Eye by Kate Quinn (another WWII story) is one of my favorites, The Huntress didn’t quite measure up to the emotional intensity and depth of that book. I would have rather liked an entire book about the Night Witches!

July 29, 2025

Review of The Hounding by Xenobe Purvis

The Hounding by Xenobe Purvis is an 18th century tale of five out-of-the-ordinary sisters living in a small village in England. Raised by their grandparents, the sisters play by their own rules in a time and place where existing within a rigid set of rules and norms is expected. Anything out of the norm is viewed as suspicious, perhaps even evil or unnatural. It is these traits that draw the mingled disgusted fascination of the local ferryman Pete Darling. Purvis’s descriptions of Pete’s inner workings scream narcissistic fragile masculinity, as well as his unsettling need to crush and destroy anything out of the ordinary or anything he perceives as weak.

Although the story is about the unique sisters, the author does not provide a pov from any of them. However, I believe this choice is by design to retain the mystery of the rumors’ validity. Instead of the sisters’ perspectives, we rather get the povs of the village men who perceived them in different ways. Pete with disgust as earlier described, Robin who goes against the grain of toxic masculinity yet masks his humanity to “fit in,” Thomas, a town outsider, who has been hired for the season’s haymaking and soon falls for the eldest sister, and the girls ‘ blind grandfather who accepts and supports his granddaughters no matter what.

The one female character pov we get is from the village publican, aptly named Temperance. Temp observes the behavior of the men in the ale house, the inception and spreading of rumors, and offers a compassionate and thoughtful ear and perspective to the men around her.

Purvis plays with our perceptions as seen through unreliable narrators such as Pete, whose bias toward the girls skews his views. If we believe Pete and what the others have claimed to see regarding the girls turning into dogs, what does that say about us? And even if what he is seen is true, does this physical transformation of the girls even matter in the grand scheme? How does Robin’s masking his true, compassionate self deteriorate his integrity as he stands at the precipice of mob mentality? Purvis’s descriptions about fragile, toxic masculinity in the face of unapologetically independent women are spot on, as are her observations regarding the mob mentality of the cult of masculinity.

In the vein of the works of Susan Stokes-Chapman and Laura Shepherd-Robinson, The Hounding is a short, poignant, and beautifully written tale sitting somewhere between Pride and Prejudice and The Crucible.

The Hounding will be released August 5, 2025