Lokke Heiss's Blog

November 29, 2018

Ring Theory

[image error]

ABSTRACT

The presence of rings on fingers are frequently seen in settings where narrative film occurs. This study assessed the relationship between the choice of finger for the ring as a predictive component for the ring bearer’s essential character traits, and describes how digital ring placement may serve as a visual cue and a foreshadowing to the audience early in the narrative as to ring bearers attributes, and subsequently what genre or genre(al) direction the narrative may follow. As such, over 200 films from multiple countries were sampled. The sampling of films was taken using the usual and customary cultural benchmarks, starting with the codification of narrative with TGTR (The Great Train Robbery) and ending with the Rat Pack Era’s Ocean’s 11 (ed. the only version that matters).

The sampling was done with a rigid enforcement of a pre-Code bias, and with concurrent strict nonenforcement of Hay’s Code rules. Other components of the study include the observation of physical nature of the ring itself to its diagetical role internal to narrative itself, with concurrent awareness of a ring’s symbolic power, its capacity for multivalency, and finally for its effect as a sliding signifier both to finger placement or to the ring bearer’s character arc – as we are talking about rings, the idea of a sliding signifier is double-encoded as both literal and metaphorical.

Conclusion: Although more research in needed to identify the relationship between digital ring placement as a way to predict foreshadowing and character revelation in film narrative, findings suggest a need to sensitize film students and cineastes as to: 1) The merits of looking at which finger a ring is worn when a character is first introduced in a film, 2) To consider the type of ring and finger placement as a Stanislavskian external manifestation of the actor’s “experiencing the role” and 3) To consider that the notation of both location and progression of ring placement may also give a character’s starting point in his “through-line” in the narrative, and will give the viewer a better overall appreciation of the how the actor will pursue the character’s superobjective.

Discussion

“Plutus himself,

That knows the tinct and multiplying med’cine,

Hath not in nature’s mystery more science

Than I have in this ring“

Shakespeare, “All’s Well That Ends Well”

The time has come not to talk about cabbages and kings, but of Murphy beds and rings. One evening, after a day of watching movies at the Cinecon Film festival in Los Angeles, I drifted over to a nearby bar with my friends, a group called the Daughters of Naldi, for a rousing discussion about the films we had just seen.

The conversation shifted from Douglas Fairbanks to the typical kind of apartments people lived in during the Classical Hollywood period, and then to how these apartments were furnished, and then to the subject of Murphy Beds. For those uninitiated, a Murphy bed is a bed pulled out of a wall, is popular even today as a space-saving device, and named after William Murphy, who patented a pivot and counterbalance design that made existing wall beds much more convenient to use. Murphy Beds are inherently funny; they move in strange and mysterious ways, and an entire generation of silent film comedians have somewhere in their careers, based one or more routines involving an encounter with a Murphy Bed. In the comedy One A.M. Charlie Chaplin takes up half of the film with his (very drunk) character merely trying to get into his very unwilling Murphy bed.

While the DoN crowd resolved to pursue the study of Murphy beds by make of a running list of films with Murphy beds—

—I chose to go a different direction. The idea of producing a list or inventory inspired me to pursue a separate investigation of something I had been noticing in an off-hand way for a long time – that is, rings worn in films. And to be clear, the interesting part of what I was noticing was usually not the ring itself, but on what finger the ring was worn.

With each scene in a film having the possibility of being densely packed with information, I reasoned how, where, and why an actor or actress wore a ring could provide a code to the audience – sometimes obvious, more often subtle – about the ring bearer. In particular, I posed a question to myself: Was ring placement more or less random – or by watching a lot of films, could I discern a typical code for each finger that would be predictive to the character’s personality or fate?

MATERIALS and METHODS

The Study – Methods Used:

I came into this idea of ring placement with the obvious knowledge that a ring on the “ring” finger would imply that the character was either engaged, married or committed in some way. But did the other fingers have their special code? I decided to investigate. My method of research was very scientific and precise – I watched hundreds and hundreds of movies, framing my time of particular interest from the silent era to about 1960, and paid attention (when I remembered) to always note what fingers the rings place and if the ring position changed as the story progressed. After years of study and untold number of films watched, here are my conclusions – but first a warning – this study is about characters in movies, not real life. Although there is obviously some connection of these ideas about rings to our cultural norms and expectations (otherwise these codes would not function the way they do), in real life there may be abundant and obvious reasons why a ring is worn on a particular finger that have no connection in any way to the topics discussed in this paper – to state one example among many, that’s maybe the only finger that the ring fits. As Freud famously said, “Sometimes a ring is just a ring.”

RESULTS

Using 1904 to 1960 (the dates of the Great Train Robbery and Ocean’s 11 as benchmarks) and with a hierarchical regression (R2 = TCM) my research demonstrated a B.S. (aka “applesauce” value less than my alpha value for significance, indicating a high level of significance for my ring theory. This means up to a 95% self-confidence level, I’m 100%, absolutely, totally correct about everything you are going to read further in this study. Note that the important element of ring placement is the finger, not the hand. Whether the ring is on the left hand or the right is of minimal importance compared to which finger the ring is on (for a movie audience, it’s much easier to “read” which finger is being used than to decide if one is looking at a right hand or left hand).

A Pinky Finger Ring – “Player or Poseur?”

Early in my research, I quickly decided that a “pinky ring” was the most obvious and clear-cut of all personality markers for finger choices, especially for men. As I watched films from the The Great Train Robbery up to the Rat Pack, I saw a long line of gangsters, rogues, rakes, and roués parade through my films, most if not all – at some point wearing pinky rings. These were men who wanted much and took what they want, and were almost always single, or acted like they were single. Women who wore pinky rings often were also presented as also having dubious or uncertain morals, although they were not as often tainted with a criminal element.

All in all, wearing a pinky ring for either sex is a code for what can be called in the common vernacular, a “player.”

[image error]

The player – Paul Muni in Scarface (1932)

But there was a second group of characters who wore pinky rings, the “wannabes,” the characters who wanted all the world to think they ran in the same crowd as the rogues, rakes, and roués, as if just wearing the ring showed the world you were just as tough. I call this type of pinky ring bearer a “poseur.” As in the animal world, where harmless snakes can copy the colors of venomous ones to reap the reward of the fear and respect of others, this group of men attempt to adorn themselves with a similar type of marking.

As one considers the two groups, one sees an interesting overlap between one and the other. Every poseur might have a little player in him, and certainly every player has some element of poseur. After all, a supremely confident male – a “zen master of masculinity” wouldn’t need a marker to announce the fact. Another element at play is that much of the drama you are about to see may be the very question asked by the presence of the ring: Is this man going really to walk the walk or talk the talk? Or is he going to fold under the first sign of danger and run for safety?

[image error]

The poseur – Peter Lorre in The Maltese Falcon (1941)

To confuse the issue slightly, not all pinky rings on men signify a criminal background or forecast an evil or salacious intent. Sometimes men who belong to an armed service, or social or professional organizations wear pinky rings as a sign they are part of a fraternal group – a band of brothers, so to speak. The fraternal or professional nature of pinky rings is especially evident in European films from this period.

While the context of the story can help the viewer decide on “what side of the tracks” this band of brothers is located (legal or criminal?), the character foreshadowing of pinky ring worn by a man still folds into the larger question the narrative will ask of its owner: “player or poseur?” The bearer of this particular type of pinky ring may not be a gangster or criminal, and in some settings may actually be the hero of the story, but the fact remains that his pinky ring is still giving us a code for masculinity and virility, which also usually means on some level he is single and sexually available. If the wearer of a pinky ring turns out the be the lead role in a story with a romantic plot, watch for the ring to disappear somewhere in the third act.

Pinky rings are the easiest and most predictable of rings to look for, so understanding them is Ring Placement 101.

A Ring on the Ring Finger – “Commitment”

[image error]

Teresa Wright and Harold Russell in The Best Years of Our Lives (1946)

You don’t have to be a ring scholar to know that a ring on this finger means that character has made a commitment, promise or pledge to something or someone. Commitment does not always mean a promise of marriage, it can be to an artistic passion, cause, or even to a religious idea. Although a ring finger is the most standard (and almost universally recognized) code for any finger, even this placement has its complexities. For example, when combined with rings on other fingers, the issues of commitment take on a more nuanced reading. Or the nature or type of ring itself can bring an ironic commentary to the customary idea of what a ring finger is supposed to signify.

A Middle Finger Ring – “A Woman of the World”

[image error]Stacia Napierkowska in The Queen of Atlantis (1921)

A ring on the middle finger is much more often seen on a woman than a man, and in terms or reading or decoding its message, has the richest number of possibilities. But if one sums up the message of the middle ring finger, it is a symbol of sophistication. A woman who wears this ring is a “woman of the world,” someone who has learned about life by study and experience, someone who is not an ingénue.

But let us keep in mind that as not all poseurs wear pinky rings, the character in the drama you are watching may fashion herself as the mostly worldly women ever, when by other clues we know that she’s not only just “fallen off the turnip truck,” she might not even know what that expression means.

[image error]An Index or Pointing Finger Ring – “The Adventuress”

In all the years I’ve been watching movies and keeping track of rings, a ring on the index finger is perhaps the most reliable predictor for who that person is. For men, it codes for characters who have already experienced exotic and dangerous activity and are looking for even more thrills and excitement. Women who wear this ring are powerful, and are also risk-takers, looking for adventure. Shy characters (unless under the cloak of disguise) do not wear this index finger rings, this is a ring worn by men and women who are used to being in command of their destiny.

A Thumb Ring Finger – “A King, an Empress, Someone Exceptional”

[image error]

Tom Cruise in Interview With A Vampire (1994)

A ring on this (specialized) finger is rarely seen in a film. It marks a ruler, a king or queen, an emperor, although it could be worn by a perhaps a kingpin of a crime organization, or someone especially skilled. A thumb ring is a ring of power. Whoever wears a thumb ring is “master of his domain.” Not seen often in films unless one is watching an historical epic, or a Fast and Furious sequel (Ed. Note – we will tolerate this brief excursion into post-1960 film to make a point).

No rings on any finger: “Off The Grid”

Having no rings on any finger means that at that moment, the character is not playing the Ring Game. Sometimes the lack of a ring might mean something, obviously the character of youth or an ingénue would be examples of someone expected to not wear a ring, or there may be a plot point involving the loss of a ring, but otherwise there is no way to reliably forecast a character’s attributes or their fate by a lack of a ring. Wait patiently for a ring to later appear, or obsess on what hat they might be wearing.

Rings on more than one finger: It’s Complicated

Surprisingly few characters in films wear more than one ring, when they do, it’s often related to a performance-related function, such as appearing in a night club act, or a scene of heightened awareness of appearance (such as being dressed like a gypsy), or in some way related as being in a masquerade. My general rule about rings on multiple fingers: The more rings you see, the more the rings are about an overall sense of costume (for example an excess of ornamentation), and not a particular commentary about the rings themselves.

But there are exceptions to this generality, in particular the pinky/ring finger combination. An example is John Stahl’s Husbands and Lovers (1924) where a wife (played by Florence Vidor), long exasperated by her husband’s lack of attention, begins to flirt with a family friend. The storyline is anticipated by the fact that at the beginning of the story we see her she wearing not one but two rings, her wedding ring and – yes, you guessed it, a pinky ring. She has a commitment of sorts, but the pinky ring tells us the arrangement is on shaky ground. The fact she has rings on both these particular fingers will (to a practiced eye) foreshadow the nature of what the storyline in this film will explore. In the previous example, one can see that Tom Cruise’s character has both a thumb and pinky finger. The combination of a pinky ring (player) and power ring (power) has an obvious meaning: This man is “mad, bad, and dangerous to know.”

Advanced Ring Theory

[image error]Earlier I mentioned that I primarily look at the which finger has the ring instead of the ring itself, but sometimes the nature of the ring itself can cast an ironic twist to the usual rules. A good example of this is in the classic film noir, Double Indemnity, starring Barbara Stanwyck and Fred McMurray. When we first see Stanwyck in her role of Phyllis Dietrichson, she is wearing a ring on her fourth finger. But this is no “ordinary” wedding ring, rather it’s large and gaudy, so garish that it’s perhaps not a wedding ring at all, even if it’s on the “correct” finger.

Her character is breaking the “rules” of ring placement, or perhaps more accurately, bending the rules to her own purposes. And as we observe her “wedding” ring and watch her flirt shamelessly with McMurray’s character, we start to get a clue as to how many levels of duplicity she is going to show us.

Even More Advanced Ring Theory

[image error]Rings are symbols, and more importantly, they are multivalent symbols, that is, they can have multiple meanings, even meanings that at the same time contradict each other (a lexicon example of this would be the word “white” which can be a symbol for strength or purity, but also can be a symbol for cowardice). Objects are less “fixed” than words, which can’t “jostle” and “slide” their meaning around as much, by contrast, objects like rings can be used as symbols to represent an almost limitless number of ideas; a promise of commitment, a bold statement of interest in adventure, to in the case of J.R. Tolkien, a representation of absolute power.

But one can focus on more traditional symbols for these rings and play directly with the codes and meanings in wonderful and contradictory ways. A great example of this is character of Sir Percy Blakeney played by Leslie Howard in the 1934 version of The Scarlet Pimpernel. Set in the time of the French Revolution, Howard’s character appears to be a useless British fop, worried only about his appearance and with no interest in politics. In reality, he is the heroic Scarlet Pimpernel, a man who courageously travels to France to rescue poor innocents from death by the guillotine.

[image error]When looking at Leslie Howard in his fop role, one sees he’s wearing a pinky ring. But let’s decode and unravel what is going on – here is a player (in the sense that Percy is really a man of action and a hero) … posing a poseur (the fop is his disguise) …who as a fop, is posing as a player (extending the idea that a fop would like to pose as a version of masculinity, a man of action). Because the role involves a secret identity, here is a situation that this ring signifies not just one, but three separate layers of meaning, all performing their symbolic function at the same moment. And now that you know your Ring Theory, you can enjoy watching Leslie Howard’s performance all the more.

Conclusions, and A Discussion with Dormitor About Early Film

The Dormitor Society is a group of film scholars who are especially interested in early film – from its beginnings to approximately 1915. During this year’s festival at Pordenone, I met with this group, and in reviewing my ideas about Ring Theory, a question came up: An obvious and important point is that the Ring Theory is not about decisions people make in real life, but rather is a tool that can be used to foreshadow character attributes in fictional stories.

But there is an intersection, a locus between the reality and the diegetic world of the character, and that locus is the actor, because he or she (or someone they work with), does have to make that choice. In other words, Ring Theory has an extension into the real world, because it is also about the choices the choices an actor makes in performing her role. And here was the question posed by Dormitor:

From film’s beginnings to a certain point where it matured as a business, (before vertical stratification changed the nature of cinema), actors often did their makeup and costuming, and certainly rings were part of that process. So are these ring placement codes any different in this early cinema? Where these codes scattered and haphazard, just as genre stories themselves were often inchoate and incomplete? Or did these ring codes arrive fully fleshed out from actor’s knowledge previous theatrical troupes and earlier traditions?

With this question in mind, the next day at the Verdi Theater I sat down for a program right up Dormitor’s alley, a screening of short French films all made before 1915. The first of these films met all the usual codes, such as an older man (with a pinky ring) courting a young woman with no ring, and a film about a widower who wore both his wedding ring and a pinky ring – so far, everything was going to expectation.

And then came a wonderful and hilarious film with the name of The Vengeance of the Town Constable (1912), a comedy farce directed by Louis Feuillade, about a newly married couple, the Brasems, who move into an apartment next to a town constable (Louis Leubas) who also happens to own the building. This constable loves to play his horn (badly) at all hours of the day or night, and the noise starts to drive the newlywed couple on the other side of the wall crazy.

[image error]

Yvette Andreyor in The Vengeance of the Town Constable (1912)

Because the constable owns the building and is also the law of the town, the couple have little recourse to stop the noise; finally the bride (Yvette Andreyor) goes to her doctor for help, and the doctor prescribes a treatment that seems completely sensible in the context of their desperate situation, he tells her to construct a life-size puppet who looks exactly like the constable, that she can torture whenever she wants. This unusual treatment works like a charm, as Mrs. Brasem enjoys beating on the dummy. Meanwhile, curious as to why his neighbor no longer seems to mind the awful noise, the constable drills a hole in the wall and is shocked to apparently see himself sitting in his neighbor’s apartment! And then things just even stranger in this delightful knockabout comedy about the trials of living next door to people you hate, which is about as good a way to describe the “human condition” as one can find.

So what does this great film have to do with rings? As I followed the antics of poor Mrs. Brasem as she ran helter-skelter trying to keep up with torturing puppets and keeping the constable out of her kitchen, I tried to count her rings – she had so many it was hard, but I eventually counted eight in all, including two thumb rings. The only fingers with no rings were of all things, her ring fingers!

Then it hit me: A French farce where everything is upside-down and nothing is as it seems – in this setting, Yvette Andreyor, who wonderfully conveyed the craziness of dealing with an impossible neighbor, was adding her own signature to her character – as one more farcical element on display, her newlywed character was wearing rings on every finger but the right one. Was this her own decision, done at the spur of the moment when she was getting her costume together? Or did she do this with help or guidance from the other actors, or from Feuillade? It doesn’t matter, because by noticing her subtle but clever addition to her part, I felt like I had reached across a century of time to appreciate a small but funny “inside joke” from a talented actress. Well done, Yvette Andreyor, and my hope is that those who follow my Ring Theory will find their own small but personal treasures.

[image error]

A take home test. Name the film, then see how many layers of meaning you can come up regarding the ring in the photo. Is there any irony that this is a wedding ring? Does the ring stand for perhaps several different kinds of commitment?

REFERENCES

TCM: A whole lot of movies (mostly black-and-white)

MoMA: A lot more movies, usually in Theater 1 and 2, occasionally Theater 3

Film Forum: So many black-and-white movies you wouldn’t believe how many I’ve seen there, mostly in that small theater to the right as you go in. Great programming by the way.

Days of Silent Film Festival, Pordenone: So many movies I had to write reviews just to keep track of them all. Mostly silent and black-and-white, occasionally a synch-sound film creeps in, we try not to notice. Thanks, Dormitor for your suggestions about this paper. Here is a link to their website-

(Additional references deleted for brevity.)

Thanks, Dormitor for your suggestions about this paper. Here is a link to their site- https://domitor.org/

August 8, 2014

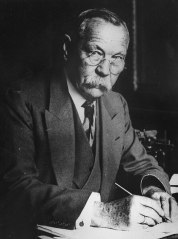

Ten Minutes With Hal Roach

Hal Roach discussing a scene with Laurel & Hardy

On October 16, 1986, I had the good luck to attend a lecture by renowned silent film producer Hal Roach. The event was held at the National Film Theater in London, and was moderated by David Robinson. Robinson reviewed his long and illustrious career, which included producing films starring Harold Lloyd, Laurel & Hardy, and many, many other comedians. After the screening and discussion of several of his films, there was time for a few questions from the audience. During this Q&A session (on which I took notes), Roach, 94 at the time of this tribute, was asked to give a brief description of several of the important comedians and filmmakers he knew or had worked with—his comments about these men all the more interesting because of their terse and completely off-the-cuff nature.

The following opinions are Mr. Roach’s, not necessarily mine.

On Charlie Chase

“He was one of the funniest men I ever worked with—naturally funny, on and off the screen. He never drank on the set, but his problem was with booze. I remember coming to visit Charlie in the hospital—he’d go in to get dried out—and I never needed to know what room he was in…I would just walk down the hall and listen to where the laughter was coming from. Then I’d go in the room and he’d be in bed and the doctors and nurses would be all around laughing their heads off listening to him. Eventually he went to Mayo (Clinic) because his drinking had caused problems with his stomach—they had to make another hole or something…well, I got a call back from Mayo—they said this guy’s got the whole hospital laughing. When the doctors told Charlie he’d be making progress when he could ‘pass wind,’ he sent invitations out to the floor inviting everyone to his room on the day it happened. They finally sent him home and he only made it for two weeks without the booze. I think he died two months later. It was all very sad.”

On Buster Keaton

“Buster got his comedy from sight gags—he only had one expression, so that was limiting. It was harder for him because he only had the gags to make things funny.”

On Laurel and Hardy

“Most teams had the comedian and the straight man. Laurel and Hardy were both comedians and this was an advantage. You could do a gag, and have Laurel react to it, and then have Hardy react to what Laurel had just done, and if it was funny enough you could have Laurel react to Hardy’s reaction. So that was great, because you could get three laughs from just one joke.”

(On being asked why the team had a decline in quality after they left his studio)

“As a gag writer, Laurel was one of the best, but he had no sense of story or plot. So when he insisted he wanted to write his own plots, I had to let them go.”

On D.W. Griffith

“Griffith was one of the greatest directors ever. He had left Hollywood for the East and then returned. We often had lunch together. My friends told me that when he ate with me, Griffith would eat a good meal, but when we didn’t have lunch, he wouldn’t eat. So I started to have a lot of lunches with him. I never had any intention of his filming One Million B.C. I just wanted him to screen the rushes, which is what he did, and he’d call me and talk to me about what I’d shot. He died not long after the film was finished.”

On Charlie Chaplin

“Charlie was the greatest comedian of them all. When I first met Charlie, he was just like you and me, an ordinary guy. Then after he got famous, he started getting invitations to meet famous people, people like Churchill, and he’d tell them something—didn’t matter what he said—and they say ‘that’s brilliant!’ So before long Charlie started believing what everybody was saying, and that changed him. What the government did to Charlie was very sad. Charlie was never a communist…he never gave a penny to anybody!”

When the Q&A was over, Hal Roach looked over the crowd and said, “No more questions? I really am disappointed in all of you.” We looked around at each other in stunned consternation. Had someone said something to offend him? What had happened? Then Roach continued: “I really am disappointed because everyone always wants to me to talk about the past, no is ever interested in what I’m doing now. I have all these projects going on. But no, no one ever asks,” he said with a wink. “Goodnight everyone.”

Hal Roach in his 90s

(from the collection of Dean McKeown)

February 13, 2014

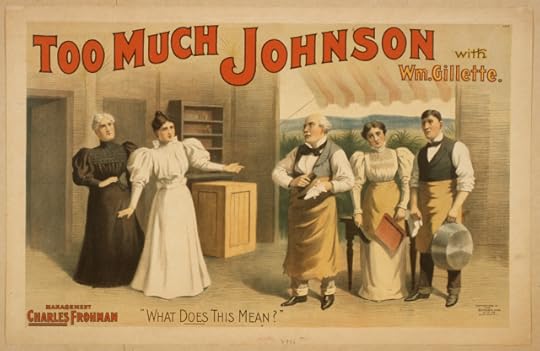

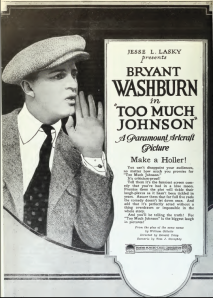

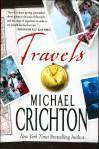

Too Much Johnson Is Never Enough Orson: The ‘Lost Film’ of Orson Welles

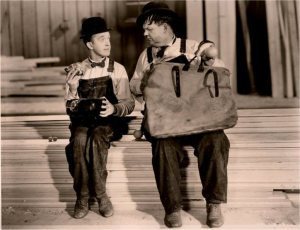

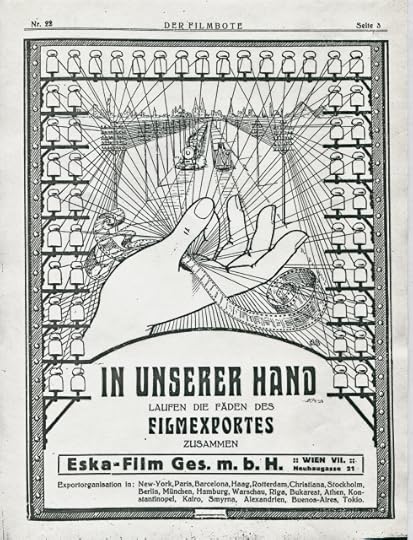

One of the highlights of last fall’s silent film festival in Pordenone, Italy was the premier of Orson Welles’s ‘lost’ 1938 film, ‘Too Much Johnson.’ A lost silent film made by Orson Welles shot three years before Citizen Kane? As usual, when talking about the life and career of Orson Welles, some explanation is in order.

Co-founders of the Mercury Theater, John Houseman and Orson Welles

In 1938, Welles, along with his Mercury Theater co-founder John Houseman, decided to stage a play on Broadway with the lewd but memorable title, Too Much Johnson. The season before Welles and Houseman had staged a successful adaptation of the French play The Italian Straw Hat. Their newly renamed version of the play, Horse Eats Hat, was perhaps a cue to the audience to expect less wordplay and more horseplay than in the original production, and they must have seen a similar possibility to amend and change the serviceable, but dated farce, Too Much Johnson. which had been first produced in 1894, and written by William Gillette, a playwright and actor, better known to us for his stage portrayal of Sherlock Holmes.

The first act of the play in its original form starts on a ship bound for Cuba, where we learn that Augustus Billings, a New York lawyer, is romancing another man’s wife by pretending he is a Cuban plantation owner. Meanwhile, there is another pair of lovers, Leonora and Henry, who must contend with an overbearing father, Faddish, who wants his daughter Leonora, to marry a plantation owner who really does have the name Johnson. As the ship sets sail for Santiago, the confusion of mistaken identities intensifies as they chase each other around the boat. In the second and third act, they reach Cuba, where after a series of misadventures, Billings, along with Leonora and Henry, escape the island, leaving Faddish and Johnson behind to plot revenge.

The first act of the play in its original form starts on a ship bound for Cuba, where we learn that Augustus Billings, a New York lawyer, is romancing another man’s wife by pretending he is a Cuban plantation owner. Meanwhile, there is another pair of lovers, Leonora and Henry, who must contend with an overbearing father, Faddish, who wants his daughter Leonora, to marry a plantation owner who really does have the name Johnson. As the ship sets sail for Santiago, the confusion of mistaken identities intensifies as they chase each other around the boat. In the second and third act, they reach Cuba, where after a series of misadventures, Billings, along with Leonora and Henry, escape the island, leaving Faddish and Johnson behind to plot revenge.

Welles liked this play well enough to consider staging in on Broadway, but with his ever- present itch to try something new, he came up with what was then a very original idea. He wanted to have a short film precede each act of the play that would function as part of the performance—the actors would be seen on the screen, and then, after the film was over, the same actors would walk unto to the stage to continue the drama—the film sequences and the live drama would function together with a unity of purpose for purpose of telling a story. The idea of linking film and theater into a combined narrative wasn’t completely new. In 1908 L. Frank Baum brought his Wizard of Oz characters to life using a combination of live actors, magic lantern slides and film in his stage production The Fairylogue and Radio-Plays, and there had been other previous productions in Europe with a similar ideas. But Welles planned to carry the concept much farther, completely integrating the elements of live theater, film and musical accompaniment into one seamless entity.

With this goal in mind, Welles gathered together the group of players scheduled to be in the stage production, and spent ten days filming scenes that would become the prologues for each act. The play was cast with actors from Welles’s repertory group, and included Joseph Cotten and a young Arlene Francis. Welles planned to edit together the footage in time for the play’s premiere, set for August 17 at Stony Creek, a small theater in Connecticut. If the play received good reviews during this ‘tryout,’ the next step would be a move to Broadway, where his idea of combining theater and film would be in full critical view. The cameraman for this project was Harry Dunham, an experienced documentary filmmaker who had filmed the Spanish Civil War and the Japanese invasion of China. Dunham was well suited for this assignment, which included largely improvisational, on-the-fly camera setups.

Welles and his crew first shot on the streets and roofs of Manhattan, and then went up the Hudson to Tompkins Cove quarry and filmed on locations that would double (with the help of a few rented palm trees) for Cuba, where the last part of the play takes place. After the filming was completed, Welles took the footage, and working in a New York hotel room, spliced together a workprint, including all the takes from each scene. This workprint ran a total of sixty-six minutes, from which about twenty minutes would have been edited together as a

Welles and his crew first shot on the streets and roofs of Manhattan, and then went up the Hudson to Tompkins Cove quarry and filmed on locations that would double (with the help of a few rented palm trees) for Cuba, where the last part of the play takes place. After the filming was completed, Welles took the footage, and working in a New York hotel room, spliced together a workprint, including all the takes from each scene. This workprint ran a total of sixty-six minutes, from which about twenty minutes would have been edited together as a prologue for the first act, with shorter prologues used for the next acts. Each of these prologues would then preface the stage portion of the next act.

prologue for the first act, with shorter prologues used for the next acts. Each of these prologues would then preface the stage portion of the next act.

It was at this time when several factors came into play with would doom the project. The first is that Welles had not secured the film rights to the play, which were owned by Paramount Pictures, who had released a version of the story in 1920. Paramount notified Welles that they would demand a fee if any type of film—no matter how experimental—was used in the production of the play. A second problem was the Stony Creek Theater—where the play  was scheduled for its tryout run—didn’t have the ability to project the film properly. Then Welles and Houseman suddenly found themselves in a cash flow problem—they had no more money to pay their actors, or buy film stock. The Mercury Theater had always run more on prestige and goodwill than on box office receipts, and with the costs of this film production quickly adding up, Welles and Houseman found themselves suddenly facing a huge budget deficit.

was scheduled for its tryout run—didn’t have the ability to project the film properly. Then Welles and Houseman suddenly found themselves in a cash flow problem—they had no more money to pay their actors, or buy film stock. The Mercury Theater had always run more on prestige and goodwill than on box office receipts, and with the costs of this film production quickly adding up, Welles and Houseman found themselves suddenly facing a huge budget deficit.

But perhaps the most pressing problem was that the play was set to premiere August 17. With no time for further editing or reshoots, with no money to pay off a film studio for the rights to an experimental project that might not work anyway, and with a venue that would not allow any simple way to project the film even if the first two conditions were met, the solution was obvious: Welles abandoned the attempt to use the filmed prologues. Shorn of these filmed interludes, or more accurately, never having them, Too Much Johnson premiered as scheduled, August 17.

As what happens to many (if not the majority) of the plays bucking for a chance to play in the very competitive New York theater circuit, Welles and his company decided the reception and critical reviews in the tryout were not strong enough to warrant a Broadway premiere. Too Much Johnson ended its short run at the Stony Creek, and the actors and staff moved on to other projects. John Houseman, in his autobiography, Run-Through, describes that Welles, angry and despondent at having to give up on his plans for the play, retreated to his hotel room and spent the week in bed. Years later, Houseman concluded the experience was Welles’s first real setback, his first significant ‘defeat’ in trying to mount an ambitious production. If so, it would set a precedent that would be repeated at a much larger scale in the years that followed.

But for now, the ever-present demand from his numerous radio programs soon returned him to his workaholic habits. Two months later, on Halloween night, October 31, Orson Welles achieved international fame with his radio broadcast of H.G. Wells’ War of the Worlds, by staging the drama as if it was really happening and being covered by the news services. Riding on a surge of fame and celebrity in a few short years he had moved to Hollywood, and in 1941, made Citizen Kane, now regarded as one of greatest films ever made. However, the release of Citizen Kane angered the 1940’s version of The Powers That Be, and afterward Welles’s career began a slow, sputtering descent, eventually forcing him to scramble for work, and giving him perpetual funding problems for his projects.

But for now, the ever-present demand from his numerous radio programs soon returned him to his workaholic habits. Two months later, on Halloween night, October 31, Orson Welles achieved international fame with his radio broadcast of H.G. Wells’ War of the Worlds, by staging the drama as if it was really happening and being covered by the news services. Riding on a surge of fame and celebrity in a few short years he had moved to Hollywood, and in 1941, made Citizen Kane, now regarded as one of greatest films ever made. However, the release of Citizen Kane angered the 1940’s version of The Powers That Be, and afterward Welles’s career began a slow, sputtering descent, eventually forcing him to scramble for work, and giving him perpetual funding problems for his projects.

Decades later, as part of a revival of interest in his work, an effort was made to recover  the workprint of Too Much Johnson, which had been put in a figurative (or perhaps literal) closet in 1938 and long forgotten. But no one could find any trace of the film. The best guess, made by Welles himself, was that the reels of nitrate film had burned in a fire in his house in Spain in the 1970s. Too Much Johnson was consigned to an ever-growing number of ‘what if’ projects by Welles that for various reasons, were never completed, a list that if compiled, would rival the collection of items seen at the end of Citizen Kane.

the workprint of Too Much Johnson, which had been put in a figurative (or perhaps literal) closet in 1938 and long forgotten. But no one could find any trace of the film. The best guess, made by Welles himself, was that the reels of nitrate film had burned in a fire in his house in Spain in the 1970s. Too Much Johnson was consigned to an ever-growing number of ‘what if’ projects by Welles that for various reasons, were never completed, a list that if compiled, would rival the collection of items seen at the end of Citizen Kane.

Decades after Welles’s death, by complete coincidence, Welles’s Too Much Johnson—a films designed by Welles to use the techniques of silent film to tell a story—turned up in a warehouse in Pordenone, Italy, a town where people come from around the world each year to attend a festival dedicated to silent film. Once it was determined that the film was indeed Welles’s ‘lost film,’ the reels were sent for restoration, and at the most recent festival, for the first time ever, the public was able to see this uncompleted project of Orson Welles.

As part of the film’s premiere, Paolo Cherchi Usai narrated the various sequences, along with piano accompaniment by Philip Carli. Before the film started, it was explained that we were watching a workprint, and were cautioned on having high expectations; after all we would clearly be watching a work in progress, with no intent for it to be a finished product. Helped both by Cherchi Usai’s knowledgeable narration and Carli’s expert ability to give us a music that matched the tone and context of what we were seeing, watching the film turned out to be a real delight. The experience was far more interesting than I had expected, and left me to ponder many ideas as I left the theater.

My first thought was that for film enthusiasts, watching a workprint, even one made as casually as this was, is a very rewarding experience. If you are interested seeing what such a print looks like, I recommend Criterion’s DVD of Night of the Hunter which includes a wonderful bonus track: Charles Laughton Directs “The Night of the Hunter,” a fascinating compilation of outtakes and behind-the-scenes footage.

Here is the link that discusses these outtakes and extra footage in more detail:

http://www.criterion.com/films/27525-the-night-of-the-hunter

My second thought about watching the workprint of Too Much Johnson is how this footage demonstrates the importance and advantage of using professional actors. Award winning director Alexander Payne, a huge fan of traditional Hollywood filmmaking, has said during interviews that 80% of directing a film is casting the right actors for the parts. I completely agree with Payne’s observation and in this footage you can see what Payne is talking about, as we watch Joseph Cotten, Arlene Francis and the rest of the actors, run through their paces (even John Houseman shows up for a cameo). These men and women are have years of experience and training—they know how to use their hands and arms, they know how to hold an expression and how to move their body—this discipline is on display even in the most cursory of shots.

My second thought about watching the workprint of Too Much Johnson is how this footage demonstrates the importance and advantage of using professional actors. Award winning director Alexander Payne, a huge fan of traditional Hollywood filmmaking, has said during interviews that 80% of directing a film is casting the right actors for the parts. I completely agree with Payne’s observation and in this footage you can see what Payne is talking about, as we watch Joseph Cotten, Arlene Francis and the rest of the actors, run through their paces (even John Houseman shows up for a cameo). These men and women are have years of experience and training—they know how to use their hands and arms, they know how to hold an expression and how to move their body—this discipline is on display even in the most cursory of shots.

John Houseman, many years before becoming a Harvard law professor, was once a Keystone Cop

I’ve read speculations that what we saw was not a workprint, but rather the ‘outtakes’ from a more carefully edited print. In other words, a more pristine (read: masterful) print exists—or at one time existed—where one can see a more finished version of the film. This line of reasoning posits that this version of Too Much Johnson was perhaps the print Welles was thinking of when he talked about losing as a consequence of the fire at his house in Spain. The idea that a more ‘finished’ film by Welles is still ‘out there,’ is tantalizing—almost too tantalizing. It smacks of a need to frame the scenario into a pulp fiction quest, a version of Dashiell Hammett’s Maltese Falcon reconstituted into cans of nitrate film perhaps still lurking in a dark, forgotten corner.

However fanciful, I would not dismiss this idea out of hand. Instead, the theory could be tested by comparing the raw nitrate film, and carefully analyzing the progression of outtakes in the sequences, while also looking for splices and other signs of alteration. No mention of this was discussed during the festival, and as to further discussion of this possibility, I quote Carl Sagan: “Extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence.”

Other reviewers of Too Much Johnson wax enthusiastic about the photography, lighting and composition of the images, comparing them favorably to Citizen Kane, still four years away. While it’s certainly possible Welles was already thinking ahead about the use of dramatic angles and deep space, let’s remind ourselves that he was working with Harry Dunham, an experienced cameraman, who surely knew how to frame a shot. What I see in most of this footage is a professional use of location and natural light in order to show the actors to the best advantage, even in the most improvisational camera setup. My conclusion: While it’s clear that Welles was involved in at least some aspects of the photography of this production, let us give credit to Dunham for doing his best in what must have been very trying conditions.

Other reviewers of Too Much Johnson wax enthusiastic about the photography, lighting and composition of the images, comparing them favorably to Citizen Kane, still four years away. While it’s certainly possible Welles was already thinking ahead about the use of dramatic angles and deep space, let’s remind ourselves that he was working with Harry Dunham, an experienced cameraman, who surely knew how to frame a shot. What I see in most of this footage is a professional use of location and natural light in order to show the actors to the best advantage, even in the most improvisational camera setup. My conclusion: While it’s clear that Welles was involved in at least some aspects of the photography of this production, let us give credit to Dunham for doing his best in what must have been very trying conditions.

One of the joys of watching this film is simply the ability to see the New York skyline of 1938. When watching a finished film shot on location, this is always a side benefit, but most films are edited so tightly that the pleasure of taking your eye off the actors and just taking in a physical space is difficult. Not so with a workprint like this, with its multiple takes. Under this format, the viewer has the freedom to enjoy the scenery without a compelling need to pay attention to any narrative. This allows you to see what New York buildings been lost to time, or to try to identify what landmarks are still present.

One of the joys of watching this film is simply the ability to see the New York skyline of 1938. When watching a finished film shot on location, this is always a side benefit, but most films are edited so tightly that the pleasure of taking your eye off the actors and just taking in a physical space is difficult. Not so with a workprint like this, with its multiple takes. Under this format, the viewer has the freedom to enjoy the scenery without a compelling need to pay attention to any narrative. This allows you to see what New York buildings been lost to time, or to try to identify what landmarks are still present.

A persistent problem I have with the all the discussion of Welles being a famous filmmaker (a discussion revisited by the discovery of this film) is that I think his major contributions are not in film but rather in theater and radio drama. The lack of attention to his stage work is natural enough, since by its nature theater is an ephemeral art, and each audience will have the pleasure of watching a dramatic performance in a way that can’t be repeated. I think the real ‘lost,’ or to be more accurate, ‘forgotten’ works of Orson Welles are his radio dramas.

We have an extensive archival collection of Orson Welles’s radio performances, from his role as The Shadow, to his pioneering work on radio literary adaptations, to even exotica like the radio series he played as Harry Lime (presumably the episodes take place before the events of The Third Man). But the popular interest for his work in this field is minimal, which is part of a larger cultural disinterest in the pursuit of radio as a medium for telling stories. Most of the radio programs from the 1930s have fallen into public domain and appreciation in the United States for this form of dramatic presentation languishes for all but the most devoted niche market.

In the context of the ten days he spent shooting Too Much Johnson, let’s look at what else was on Welles’s plate for the spring and summer of 1938. The Mercury Theatre itself was finishing a run of the critically acclaimed adaptation of The Tragedy of Julius Caesar that evoked comparison to contemporary Fascist Italy and Nazi Germany. It premiered on Broadway on November 11, 1937 and this production extended into 1938. On March 14, 1938, the Broadway production moved from the Mercury Theatre to the National Theatre. The Mercury Theatre’s second production was a staging of Thomas Dekker’s Elizabethan comedy The Shoemaker’s Holiday, which attracted “unanimous raves.” It premiered on January 1, 1938, and ran to 64 performances in repertory with Caesar, until April 1. The third Mercury Theatre play was an adaptation of George Bernard Shaw’s Heartbreak House, which again attracted strong reviews. It premiered on April 29, 1938, and ran for six weeks, closing on June 11. It was the last Mercury Theatre production before the troupe began broadcasting on the radio as well. Orson Welles (with John Houseman) was the co-founder of the Mercury Theater, and although he certainly didn’t have day-to-day management duties, he at least had nominal supervision of all these projects.

In the context of the ten days he spent shooting Too Much Johnson, let’s look at what else was on Welles’s plate for the spring and summer of 1938. The Mercury Theatre itself was finishing a run of the critically acclaimed adaptation of The Tragedy of Julius Caesar that evoked comparison to contemporary Fascist Italy and Nazi Germany. It premiered on Broadway on November 11, 1937 and this production extended into 1938. On March 14, 1938, the Broadway production moved from the Mercury Theatre to the National Theatre. The Mercury Theatre’s second production was a staging of Thomas Dekker’s Elizabethan comedy The Shoemaker’s Holiday, which attracted “unanimous raves.” It premiered on January 1, 1938, and ran to 64 performances in repertory with Caesar, until April 1. The third Mercury Theatre play was an adaptation of George Bernard Shaw’s Heartbreak House, which again attracted strong reviews. It premiered on April 29, 1938, and ran for six weeks, closing on June 11. It was the last Mercury Theatre production before the troupe began broadcasting on the radio as well. Orson Welles (with John Houseman) was the co-founder of the Mercury Theater, and although he certainly didn’t have day-to-day management duties, he at least had nominal supervision of all these projects.

In addition to these numerous and complex theater productions, Welles was so in demand as a radio actor that he had to be taken from one studio to another by ambulance to get to the recordings in time. An partial list of these roles in the summer of 1938 include a weekly performance as The Shadow and a lead role in a CBS show titled First Person Singular, a series of radio dramas adapted famous literary novels. Soon to be renamed The Mercury Theater on the Air, Welles and his associates would rehearse the script, make editing changes, and perform the show—all in less than seven days. Sometimes the script would be written in hours, not days or weeks. John Houseman, in his autobiographies Run-Through and Unfinished Business, talks about Welles’s sudden decision to use Bram Stoker’s Dracula for next week’s show. To meet this impossible deadline, Welles and Houseman spent all night at Perkin’s restaurant in Manhattan tearing the pages out the Stoker’s novel so that they could condense and rewrite the story to get it down to a one-hour format. And seven days later they had to be ready for Treasure Island. The year of 1938 must have been a blur on the calendar for both Welles and his staff.

In addition to these numerous and complex theater productions, Welles was so in demand as a radio actor that he had to be taken from one studio to another by ambulance to get to the recordings in time. An partial list of these roles in the summer of 1938 include a weekly performance as The Shadow and a lead role in a CBS show titled First Person Singular, a series of radio dramas adapted famous literary novels. Soon to be renamed The Mercury Theater on the Air, Welles and his associates would rehearse the script, make editing changes, and perform the show—all in less than seven days. Sometimes the script would be written in hours, not days or weeks. John Houseman, in his autobiographies Run-Through and Unfinished Business, talks about Welles’s sudden decision to use Bram Stoker’s Dracula for next week’s show. To meet this impossible deadline, Welles and Houseman spent all night at Perkin’s restaurant in Manhattan tearing the pages out the Stoker’s novel so that they could condense and rewrite the story to get it down to a one-hour format. And seven days later they had to be ready for Treasure Island. The year of 1938 must have been a blur on the calendar for both Welles and his staff.

Here is only a partial list of the novels adapted in the summer and fall of 1938 for his radio drama series:

July 11 Dracula by Bram Stoker

(It was after this radio performance that Houseman says they started shooting Too Much Johnson)

July 18 Treasure Island by Robert Louis Stevenson

July 25 A Tale of Two Cities by Charles Dickens

August 1 The Thirty Nine Steps by John Buchan

August 29 The Count of Monte Cristo by Alexandre Dumas

October 2 Oliver Twist by Charles Dickens

October 16 Seventeen by Booth Tarkington

October 30 The War of the Worlds by H. G. Wells

November 6 Heart of Darkness by Joseph Conrad

(This list is from Jonathan Rosenbaum, “Welles’s Career: A Chronology”, in Jonathan Rosenbaum (ed.), Orson Welles and Peter Bogdanovich, This is Orson Welles. New York: Da Capo Press, 1992)

The number and variety of productions Welles was involved with in this period is breathtaking. Of course not every project he worked on was meant to be deathless prose, or even memorable. Much of what he did was simply use his wonderful, sonorous voice to give life to a script thrust in front if him, as he ran, breathless, from one gig to another. Todd Tarbox’s book, Orson Welles and Roger Hill: A Friendship in Three Acts includes an interview Welles gave many years later, describing this moment in his life: “I was making a couple of thousand a week, scampering in ambulances from studio to studio, and committing much of what I made to support the Mercury. I wouldn’t want to return to those frenetic 20-hour working day years, but I miss them because they are so irredeemably gone.”

The number and variety of productions Welles was involved with in this period is breathtaking. Of course not every project he worked on was meant to be deathless prose, or even memorable. Much of what he did was simply use his wonderful, sonorous voice to give life to a script thrust in front if him, as he ran, breathless, from one gig to another. Todd Tarbox’s book, Orson Welles and Roger Hill: A Friendship in Three Acts includes an interview Welles gave many years later, describing this moment in his life: “I was making a couple of thousand a week, scampering in ambulances from studio to studio, and committing much of what I made to support the Mercury. I wouldn’t want to return to those frenetic 20-hour working day years, but I miss them because they are so irredeemably gone.”

When placed in the context of all the other work Welles was doing in 1938, the ten days of shooting a silent film on the streets of New York must have felt like a summer vacation. And more importantly, it was an easy project to put aside as other more important projects loomed in the horizon.

Looking at the impressive list of these radio dramas, of particular interest are the last two productions: If anyone remembers Welles’s radio work at all, it is because of his version of War of the Worlds, probably the most famous radio show ever done. And then in just the next week, the Mercury Theater group performed a story that Welles thought highly of, The Heart of Darkness. This was the first film project he attempted when given his contract at RKO and elements of the story found their way into Citizen Kane. Indeed, one could argue that our effort to peer into a heart of man who does not even understand himself is essentially an urbanized version of The Heart of Darkness.

Looking at the impressive list of these radio dramas, of particular interest are the last two productions: If anyone remembers Welles’s radio work at all, it is because of his version of War of the Worlds, probably the most famous radio show ever done. And then in just the next week, the Mercury Theater group performed a story that Welles thought highly of, The Heart of Darkness. This was the first film project he attempted when given his contract at RKO and elements of the story found their way into Citizen Kane. Indeed, one could argue that our effort to peer into a heart of man who does not even understand himself is essentially an urbanized version of The Heart of Darkness.

Some final thoughts: In the program notes, and in the subsequent reviews written about this film, the idea has been put out that Welles intended to have three prologues, one to start each act. However, Houseman in his memoirs writes that Welles planned two filmed prologues, not three. In reading the theater script and watching the workprint, I think Welles planned to condense act two and three into just one act, and have only a prologue before each act. Since part of the workprint includes a duel (alluded to but not shown in the original play), the possibility exists of having a third filmed interlude near the end of Welles’s adapted version. So this technically gives us two prologues, not three, and then perhaps the possibility of a filmed sequence right before the climax of the farce. This intent could perhaps be verified by examining an actual script used at the Stony Creek Theater performance (assuming this script survives) and this would help us better understand how Welles planned to integrate his filmed interludes into the play.

During the film’s premiere in Pordenone, and in subsequent discussions about the film, the theory was put out that Welles designed these prologues as ways of simplifying and condensing the expositional elements of the play so each act could ‘hit the ground’ running and plunge quickly into the story. After reading the original theater script of Too Much Johnson I am convinced this idea is wrong, or at least misleading. If anything, the prologues add complexity to the story, by showing us the events that happened just before the ship sails off to Cuba. In the theater script, much of the backstory is given to us in a quick (if dramaturgically awkward) fashion by Billings, who explains to a befuddled purser why all the involved parties are on board. In a few short passages, we have all we need to know about all the characters.

I think Welles had a simple and much better reason to do this—a filmed prologue was going to be the twist, the ‘new’ thing that made his play different from anyone else’s. He had been the first to put ‘voodoo’ in Macbeth; he had been the first to stage Julius Caesar in the setting of a contemporary fascist state. So the challenge for him was to figure out what could he do with Too Much Johnson, something so interesting that everyone had to see it. In reading the script of the play, a thought may have come to him (it did to me)

I think Welles had a simple and much better reason to do this—a filmed prologue was going to be the twist, the ‘new’ thing that made his play different from anyone else’s. He had been the first to put ‘voodoo’ in Macbeth; he had been the first to stage Julius Caesar in the setting of a contemporary fascist state. So the challenge for him was to figure out what could he do with Too Much Johnson, something so interesting that everyone had to see it. In reading the script of the play, a thought may have come to him (it did to me)  that there were elements of the play that functioned better in the style of silent film slapstick comedy than as theatrical farce. At some point while mulling over this script, the idea must have struck him —why not include silent slapstick comedies, and dramatically integrate them into the production? Nobody had done that before. Another first, another Orson Welles original.

that there were elements of the play that functioned better in the style of silent film slapstick comedy than as theatrical farce. At some point while mulling over this script, the idea must have struck him —why not include silent slapstick comedies, and dramatically integrate them into the production? Nobody had done that before. Another first, another Orson Welles original.

And he was completely right to think this. Orson Welles’s talents were in the direction of adaptation, rather than in writing or developing his own material. I say this not as a criticism, but rather as an explanation of one of Welles’s greatest gifts—the ability to see how to find an angle that would take something old and make it new. When he was forced to abandon the idea to include these films as part of performing Too Much Johnson, Welles knew more than anyone that the play would revert back to being a creaky, outdated, turn-of-the-century farce. After the short run at Stony Creek, which Houseman described as ‘trivial, tedious and underrehearsed,’ any thought of transferring the production to Broadway was abandoned, and after the last performance, the play was quickly forgotten, becoming merely a odd footnote to Orson Welles’s career.

In regard to plays performed with filmed interludes—I have seen two plays with film incorporated into live theater, the musical Hollywood Boulevard, and a drama, Hitchcock Blonde. In my opinion, neither attempt at mixing stage with filmed images worked for the simple reason that the moving image was always more compelling to the eye than the static stage. Just when you hoped you could sit back and enjoy the movie, the lights went on and the actors started their business. But to be fair, I can’t compare these modern attempts to blend film and theater to what Welles did—his prologues were different and more complex, not only because the actors on the screen were the same actors who were doing the stage performance. Welles was trying for a truly integrated attempt to integrate the scenes into the play, which leads to my final thought:

After watching these sixty-six minutes of film, I can’t think of a greater honor to Welles than for someone to take the material here and fashion something new out it. Welles spent his entire career updating versions of other people’s work (Shakespeare being the most obvious), so ‘re-purposing’ this material would be a very Wellesian proposition. There would be two obvious directions for this—one would be to cut together these dailies and fashion the prologues as he had planned so that the play itself could be performed as he originally intended. The other idea would be to take the footage and create a new piece of silent film with no need to connect itself with the Gillette play; with the right editing and judicious use of intertitles, an ambitious editor could put together a completely new story. It’s been done before in the silent film world, using stars such as Chaplin—this new story could be a slapstick silent film done under the style of Mack Sennett, starring the able and forever young cast of the Mercury Theater. And while watching for this updated version of Too Much Johnson, we can always hope for other plays, films and radio dramas by artists who are inspired by what Welles was able to achieve. Inspired by, but not a slave to his work, because above all there is always the dictum that Welles gave to himself: Always find a way to make what you are doing different, unique, and your own.

After watching these sixty-six minutes of film, I can’t think of a greater honor to Welles than for someone to take the material here and fashion something new out it. Welles spent his entire career updating versions of other people’s work (Shakespeare being the most obvious), so ‘re-purposing’ this material would be a very Wellesian proposition. There would be two obvious directions for this—one would be to cut together these dailies and fashion the prologues as he had planned so that the play itself could be performed as he originally intended. The other idea would be to take the footage and create a new piece of silent film with no need to connect itself with the Gillette play; with the right editing and judicious use of intertitles, an ambitious editor could put together a completely new story. It’s been done before in the silent film world, using stars such as Chaplin—this new story could be a slapstick silent film done under the style of Mack Sennett, starring the able and forever young cast of the Mercury Theater. And while watching for this updated version of Too Much Johnson, we can always hope for other plays, films and radio dramas by artists who are inspired by what Welles was able to achieve. Inspired by, but not a slave to his work, because above all there is always the dictum that Welles gave to himself: Always find a way to make what you are doing different, unique, and your own.

May 5, 2013

Roger and Me: An Almost Perfect London Walk

Roger Ebert’s death on April 4, 2013 has produced—for his vocation—a degree of sympathy and support that is perhaps unprecedented (since when have so many people been emotionally affected by the death of a film critic?). While some of this reaction is related to the Internet and the rise of social media (when Pauline Kael died in 2001, Facebook was three years away from its launch), one should not underestimate the personal connection Roger Ebert had with many of his readers and supporters—if you had the slightest interest in film, you knew who this person was. You may not have always agreed with his opinions and reviews, but it was impossible not to respect his effort to give each film a clear and honest appraisal. In looking back at history, I’d have to go back to Will Rogers to find a American writer who was better able to use a variety of media (today we’d call it convergence) in order to maintain high visibility, and do it not for the purpose not to primarily serve his own career, but instead to promote causes and interests he thought were important. That puts Roger in very select company.

Roger Ebert was at heart a newspaperman, a reporter in the best tradition of his fellow Sun-Times columnist Mike Rokyo. By accident or intent (I think much of this was in place before Roger ever got to Chicago), Roger followed Rokyo’s formula for success:

1) Write about what interests you, wherever that takes you.

2) Don’t show off—use smaller words when they work just as well as longer ones.

3) On the other hand, don’t play dumb, respect the intelligence of your reader to either know what you are saying or have the gumption to look up your reference and learn something.

Ebert’s writing aimed for clarity and simplicity, but it’s a mistake to think it was not learned; his reviews and articles over the years reflected an expertise about many topics and this knowledge would often add that extra touch that would elevate what he wrote from the ordinary to the special. And as someone who had been trained as a sports reporter and was interested in more than just movies, he loved doing work unrelated to his main job as a film critic. In particular, in 1986 he cowrote a guidebook with his friend Daniel Curley titled: A Perfect London Walk.

The book is many things, but mostly concerns a walking tour in northern London starting west of Hampstead Heath and finishing near Highgate Cemetery. I found his book in a London bookstore in 1986, and was immediately captured by its combination of wit and sense of purpose. The guidebook’s ability to connect literary references to real locations acts as a ‘literary buoy,’ if you will, allowing the reader to see, taste and smell the location that inspired the poem or story, thus enjoying the author’s creation all the more. A Perfect London Walk then, is much more than a guidebook, it is also a sort of manifesto of Roger Ebert’s interests concerning a time and place in English history and how this place influenced its local writers. Although I had never met him, in reading this book and then reading more about him from other sources, I found we had much in common. Roger and Me–old friends, even though we had never met.

Roger was born and raised in Urbana, Illinois, only a few hours from my hometown. We grew up both huge science fiction fans, we both wrote for fanzines, we both worked for local newspapers in our hometowns, we both went to local colleges in our hometowns after high school. We both were readers, and loved fiction, especially British literature. After graduating from the University of Illinois, Roger went on to Chicago, while I went to medical school at the University of Illinois at Urbana. From there our paths deviated a bit, but there would always be these common connections, and above all a love of movies.

Roger and Me. After his death, I have discovered there are a lot of Me’s out there. There is the Me of documentary filmmaker Michael Moore, who Roger championed in the late 1980s. There is the Me of Werner Herzog, a German director who Ebert praised and promoted, even during times when Herzog was having difficulty getting funding for his next film. There is the Me of thousands of readers who appreciated his frankness and passion in his writing and how he bravely kept reinventing his life. There are too many Me’s to try and list, but you know who you are.

A few years ago, I was in London and decided to repeat the walk and see how it had changed. Since by now Roger was ill, I resolved to send him a letter describing my walk. On this visit, I took photos to show how the walk had changed from the year it was documented in his book, but then, to reinforce how central the heath is to a certain chapter of British literature, and not be slavishly repetitious to what he had done, I came up with a new set of quotes from literary sources that had a connection to Hampstead Heath. A version of this ‘travel essay’ went out as a Christmas Greeting to Roger and Chaz the year of my revisit. Then I filed a copy of it away and moved on to other things.

This month, sad like everyone else at hearing the news of Roger’s passing, I thought about the Hampstead Heath and wondered if people were still using his guidebook. I checked Amazon.com and found the price of a used paperback of A Perfect London Walk going for $387.82 with one seller at more than a thousand dollars. I think it is safe to say this book is in need of a both a revision and a reprint. The cowriter of this book, Daniel Curley (who was Roger Ebert’s professor at the University of Illinois) tragically died from a traffic accident in 1988, so there will be no simple way for this to happen.

With this in mind, I have adapted the text of my letter to Roger to make it accessible to readers for which the guidebook will not be available, but are still interested in British literature and London history. In other words I’m posting this ‘travel essay’ as a thank you to Roger and in the hope of like-minded people reading this and becoming interested enough to include this walking tour on their next trip to England. Perhaps this account will produce one more Me in already a long and loyal list of Roger and Me’s. So here is my letter, addressed to Roger, but really going out to those who know him or have been touched by him in some way.

Dear Roger Ebert,

I’m titling this letter, “An Almost Perfect London Walk.” The only thing that kept this walk from being perfect is that you and Chaz were not part of the trip. While on the walk, I talked to a local who informed me that he’s met plenty of people with the same idea—that is, they told him they were going to write to you after their day on the heath. For all I know you might get thirty of these a day. Maybe you have a form letter to respond to the exigency of responding to this particular fan letter. If so, please file this account in the ‘Roger Ebert’s Perfect London Walk Response Letter’ genre that you have unwittingly created, and I can only hope that because no two heath walks can be the same, no two heath walk letters can be the same.

On the morning of my walk, I start at Russell Square. While in London as a student, this park became my second home, and I always go back to it when I return. There are hundreds of squares and parks in London, but Russell Square has some quiet simplicity of function and use that calms my nerves and yet still gives me energy. For me, all London journeys somehow start from a park bench at the center of Russell Square

I don’t remember where I bought your book, probably at Foleys, or one of the downtown London bookstores. I used it to take my original Hampstead Heath trip but since it has been more than two decades since your book was published, it’s going to be interesting to see what has changed and what has stayed the same since the 1980s.

Taking the Northern Line to Belize Park, I pop out of the escalator and into daylight on Haverstock Hill.

Turning right, Colonel Sanders is there to greet us, a new sign, but his iconic smile of Southern hospitality unchanged.

“The man is who is tired of London is tired of looking for a parking place.”

Paul Theroux

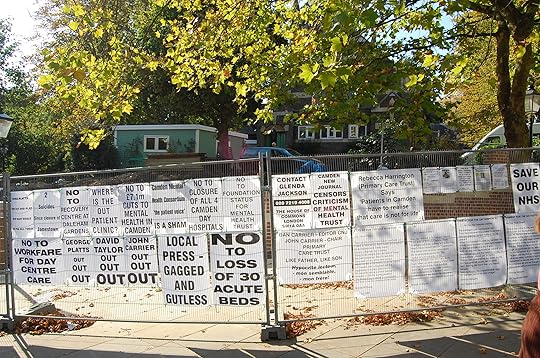

Walking past the George, I arrive at Hampstead Green and almost miss the turn because of construction. Signs explain that St. Stephen’s Church is undergoing a major renovation. The Royal Hospital also show signs of renovation, although the most interesting part of this walk are the signs on the security fences. “No to loss of 30 acute beds.” “Local Press Gagged and Gutless.” and “Save our NHS” are among the many Hyde Park-like banners of protest and dissension.

of construction. Signs explain that St. Stephen’s Church is undergoing a major renovation. The Royal Hospital also show signs of renovation, although the most interesting part of this walk are the signs on the security fences. “No to loss of 30 acute beds.” “Local Press Gagged and Gutless.” and “Save our NHS” are among the many Hyde Park-like banners of protest and dissension.

Past the hospital is the street leading to Adolph Huxley’s home. Not having the time to dwell on Huxley, I turn the corner and walk up to the plaque commemorating George Orwell. I reflect on the thought that the two faces that have greeted me unchanged in twenty years are Colonel Sanders and George Orwell. I don’t know whether to shoot an elephant or ask for Extra Crispy.

The plaque commemorates the bookstore that Orwell worked in for two years, 1934-35. He would use the experience to write Keeping the Aspidistra Flying, a novel about a man working in a bookstore. It was about as upbeat as he was ever going to get, and those of you who like Orwell and bookstores, this is the one book I recommend of his that gives you some ray of hope for the human condition.

Passing the South End Road, I approach Keats Grove.

Having spent much time in Keat’s house on my first visit, on this trip it’s pleasant to just sit on the bench and savor the sunshine and flowers. This beautiful fall day seems an impossibly long way from his melancholy description of a garden from “Ode to a Nightingale” -

Having spent much time in Keat’s house on my first visit, on this trip it’s pleasant to just sit on the bench and savor the sunshine and flowers. This beautiful fall day seems an impossibly long way from his melancholy description of a garden from “Ode to a Nightingale” -

I cannot see what flowers are at my feet,

Nor what soft incense hangs upon the boughs,

But, in embalmèd darkness, guess each sweet

Wherewith the seasonable month endows

The grass, the thicket, and the fruit-tree wild;

White hawthorn, and the pastoral eglantine;

Fast-fading violets cover’d up in leaves;

And mid-May’s eldest child,

The coming musk-rose, full of dewy wine, The murmurous haunt of flies on summer eves.

Leaving Keat’s house, I discover Keats Pharmacy, no doubt empty of hemlock and dull opiate, but perhaps stocked with the latest antibiotics to fight tuberculosis.

The preliminary attractions are over, it’s time for the main event, the walk through Hampstead Heath-

“The moon was full and broad in the dark blue starless sky, and the broken ground of the heath looked wild enough in the mysterious light to be hundreds of miles away from the great city that lay beneath it. The idea of descending any sooner than I could help into the the heat and gloom of London repelled me. The prospect of going to my bed in my airless chambers, and the prospect of gradual suffocation, seemed, in my present restless frame of mind and body, to be one and the same thing. I determined to stroll home in the purer air by the most roundabout way I could take; to follow the white winding paths across the lonely heath; and to approach London through its most open suburb by striking into the Finchley Road, and so getting back, in the cool of the new morning, by the western side of the Regent’s Park.”

Wilkie Collins, The Woman in White

At the entrance to the heath, there is a pond where children are feeding the ducks.

At the entrance to the heath, there is a pond where children are feeding the ducks.

A few yards later, I arrive at the next pond, in time to see a dog leap in the water and in a fevered display of canine frenzy, charge after some goslings. The mother goose, looking like a giant condor with its outstretched wings, comes to their rescue. The dog, outsized, outmatched and outmaneuvered, beats a hasty and embarrassing retreat back to dry land.

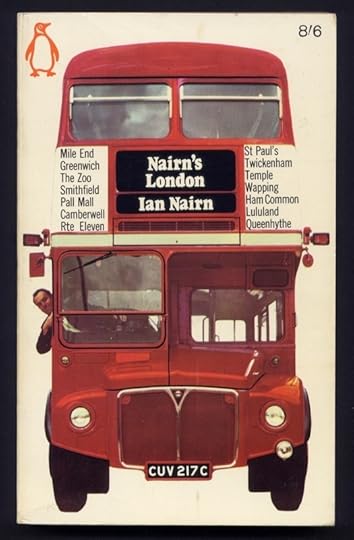

Now we come to the ‘spookier’ part of the walk, at least described by Ian Nairn. Roger Ebert’s dedication to London’s history is illustrated by his interest in keeping this London newspaper columnist in print.

Now we come to the ‘spookier’ part of the walk, at least described by Ian Nairn. Roger Ebert’s dedication to London’s history is illustrated by his interest in keeping this London newspaper columnist in print.

Here’s a link, in Roger Ebert’s own words, about Ian Niarn:

http://www.rogerebert.com/rogers-journal/nairns-london-an-introduction