Graeme Shimmin's Blog

July 19, 2024

Melodrama and How to Use It

From an original article Melodrama and How to Use It, posted at Graeme Shimmin, spy thriller and alternate history writer

Picture this: a dastardly villain twirling his moustache, and a damsel in distress tied to the railroad tracks. Sounds like melodrama! But what if I told you that some of the most beloved stories of all time are, in fact, melodramas?

What is Melodrama, anyway?Melodrama often gets a bad rap, especially from critics who use it as a catch-all insult for stories they dislike. But let’s get back to basics. The actual definition of melodrama is:

A story where exaggerated emotions, stereotypical characters and a sensationalised plot featuring unrealistic problems attempts to elicit a strong emotional reaction from the audience.

The key word here is ‘unrealistic’.

Drama features realistic characters involved in a realistic plot displaying realistic emotions as they face realistic problems.

Melodrama features stereotypical characters involved in a sensationalised plot displaying exaggerated emotions as they face unrealistic problems.

What’s wrong with Melodrama?Well, arguably, nothing. Much of modern storytelling is basically melodrama, and there are many examples of stories that are both melodramatic and timeless classics:

RebeccaNow VoyagerBrief EncounterWuthering HeightsThe Count of Monte CristoIt’s a Wonderful LifeA Streetcar Named DesireRomeo and JulietGone With the WindWhat do these stories have in common? Larger-than-life characters grappling with intense emotions and confronting huge moral dilemmas. Sound familiar?

Clearly, there’s not necessarily anything wrong with larger-than-life characters, intense emotions or huge moral dilemmas. Let’s look then at the four characteristics of melodrama in more detail and see where the problem lies.

The Four Characteristics of MelodramaThe characteristics we’ve identified are:

Exaggerated emotionsStereotypical charactersA sensational plotUnrealistic problemsBut are all these elements inherently bad, because to me, this list seems to conflate two different things:

Events: plot and problemsPeople: characters and emotionsLet’s explore in more detail.

The Good, the Bad, and the MelodramaticStrong Emotional Reactions?When done right, melodrama can evoke a strong emotional response, and I think we can agree that as writers, we should aim to elicit a strong emotional reaction in our reader. Leading the reader to express indifference and apathy after reading our uninspiring, unemotional novel isn’t really what we’re aiming for. And if the reader goes ‘meh’ when they finish the story, it won’t become a blockbuster, will it?

So, we’re not really doing our job and are unlikely to be successful as writers if we don’t generate an emotional reaction to our work.

Plots and ProblemsAs a speculative fiction author, I’m drawn to the unrealistic. A lot of the fun of a story for me is precisely the thing in the story that’s unrealistic: the speculative element. I mean, Star Wars, The Lord of the Rings, The Avengers and Doctor Who ain’t exactly what you’d call gritty and down-to-earth, are they?

It seems to me that it’s a small-minded view of fiction to suggest the plot should always be ‘realistic’. To me, there’s nothing wrong with ‘unrealistic’ plots and high-stakes situations. In fact, they’re often what make a story memorable, because a sensational plot is gripping, engaging and fun. Mysteries, intricate plots and unexpected twists are what most people want in their stories, what keeps them turning the pages.

Characters and EmotionsThere’s nothing good about stereotypical characters. And having our characters exhibit exaggerated emotional reactions isn’t good either.

So, it seems that stereotypical characters and exaggerated emotional reactions are where the problem with melodrama lies.

But, there’s a fine line between a stereotype and an archetype. Archetypal characters like Protagonist and Antagonist are necessary for a story to be a story. Characters with distinct traits and motivations are what stories are all about. So, we’re going to have to explore where the balance between archetypal characters that resonate with readers and stereotyped characters is.

(For more about archetypes, see Story Archetypes that Make Your Novel Resonate.)

The Danger with Melodrama: BathosBathos is perhaps the major danger when writing emotional scenes. But what exactly is bathos, and why is it so problematic?

Bathos occurs when a writer attempts to evoke a strong emotional response but accidentally produces an anticlimactic, comic effect. It’s what happens when the author’s attempt at Pathos—evoking pity, sadness or empathy—fails. It’s unintentional.

For example, the notoriously terrible movie, The Room, has this dialogue:

You’re tearing me apart! I did not hit her! I did not! Oh, Hi, Mark.

Bathos undermines the emotional impact we’re aiming for. The last thing we want is for our readers to laugh when we’re trying to make them feel pity, sadness or empathy, isn’t it?

Overblown similes are a common source of bathos. For example:

Her heart shattered into a million pieces, like a dropped iPhone screen.

Luckily, we can avoid bathos by:

Ensuring the level of emotion matches the situation.Getting feedback on the story. Readers will spot unintended comedy in serious, emotional scenes.Reading work aloud: This helps catch the kind of awkward phrasing that can lead to bathos.Carefully considering metaphors and similes.To an extent, bathos depends on the reader, as it’s their reaction and not everyone reacts the same. But remember, accidental comedy will undercut everything you’re trying to achieve, and always keep an eye out for it.

How to Solve the Problems with MelodramaSo, we’ve seen that there are good things and bad things about melodrama, and often a fine line between the two. How then to walk that line?

The Dysfunctional Response: No emotionIn an attempt to rid their story of the stench of melodrama, some writers tone down their stories. They don’t write big scenes, their characters don’t express or feel powerful emotions. These writers think they’re being subtle, but in trying to avoid melodrama, they’ve discarded something valuable.

The Solution: Stronger MotivationIn his magnum opus, ‘Story’, Robert McKee suggests that:

Melodrama is not a problem of over-expression, but of under-motivation; not of writing too big, but of writing with too little desire.

So, the problem isn’t necessarily the level of emotion. The problem is when a character’s emotional responses are not proportional to the issues they face. If a character breaks down over the loss of a child, then that’s proportional. If they break down over the loss of a handkerchief? Not so much.

This shifts our understanding of melodrama from a problem of excess to one of insufficient foundation. Let’s explore how stronger motivation solves the problem.

How Stronger Motivation Solves Melodrama IssuesWith robust motivations, even extreme emotional responses become understandable and relatable. For example, if a character is suicidal because they lost their paper-round, that’s ridiculous. But if they lose their dream job, they’re deeply in debt and the only way to save their family from penury is to claim on their life-insurance, then we can understand their reaction, even if we see how tragic it is.

Similarly, strong motivation can transform one-dimensional characters into complex individuals. The “evil stepmother”, for example, could be grappling with her own demons. Her problems might not excuse her actions, but they do make them more understandable.

When characters have strong motivations, even extraordinary actions feel more realistic. When Ripley risks her life to confront the Alien Queen and save Newt in Aliens, for example, we don’t find it melodramatic, because we know her motivation stems from losing her own daughter.

How to Strengthen MotivationA great way to make sure characters aren’t being melodramatic is to create a Character Worksheet that includes their motivations. For each character, write down:

A backstory (even if not all of it makes it onto the page).An explanation of how the backstory shapes their motivations in the story.What the stakes are for the character.Their goals (which can be conflicting)Why each goal is important to them.What they fear will happen if they fail.How each goal relates to their backstory.Use these Character Worksheets as a reference when writing emotional scenes. Ask yourself, “Are the character’s stakes and motivation strong enough to justify this?” If it isn’t, then either strengthen the motivation or tone down the emotion.

Finding the Sweet SpotRemember, the goal isn’t to eliminate big emotions or high-stakes situations from our writing. Instead, it’s to make sure strong emotions and high stakes feel realistic. By focusing on stronger motivations, we can keep the engaging aspects of melodrama while avoiding its pitfalls, creating stories that are exciting and create an emotional reaction in the reader.

If we go back to the earlier definition and edit it, we see what we need to aim for:

Things to DoRemember that creating emotionally resonant stories isn’t inherently bad.Think about your favourite stories. What unrealistic elements do they include?Make a note of some stories you responded emotionally to.What is it about those stories that caused your response? Why?Analyse your own work. How melodramatic is it?Consider if your work would benefit from portraying stronger emotions.Experiment with evoking more emotion in a dramatic scene in your story.Try dialling the emotion back in a less dramatic scene.Want to Read More?A story featuring realistic characters involved in a gripping plot displaying realistic emotions as they face extraordinary problems.

The book I recommend for all plot structuring, including endings, is Story by Robert McKee. It’s available on Amazon US here and Amazon UK here.

Help!If you need help with melodrama, or any other aspect of your writing, please email me. Otherwise, please feel free to share this article using the buttons below.

Original article Melodrama and How to Use It, posted at Graeme Shimmin, spy thriller and alternate history writer

December 1, 2023

How to Write a Frame Story that Works

From an original article How to Write a Frame Story that Works, posted at Graeme Shimmin, spy thriller and alternate history writer

So, if you’re wondering how to write a frame story, here’s the lowdown.

What a Frame Story IsA frame story is where most of the action takes place as a story within a story.

The ‘world’ of the frame story is different to the main story.

Three Types of Frame StoryGlueIf the author writes a novel that comprises multiple short stories, then a frame story can bring them together into a coherent whole. I call this a ‘glue’ frame story.

This type of frame story is as old as storytelling. The ancient Egyptians used ‘glue’ frame stories, as does the Sanskrit epic, The Mahabharata.

John le Carré’s A Perfect Spy has a glue structure. The main character is missing and the search for him is a frame story for a narrative where the characters tells anecdotes about the main character’s life.

Similarly, Dan Symonds’ Hyperion has a frame story about an expedition. As they travel, the expedition’s six members tell stories about their backgrounds. These six stories make up the bulk of the novel.

Skipping the Boring BitsThis type of frame story is similar to the glue type, but the author uses the frame story as an opportunity to skip ahead by using narrative summary. Something like:

‘So what happened after that?’

‘I didn’t see him again for two years and then we bumped into each other on the street…’

And back to the main story.

BookendsSometimes an otherwise complete narrative opens and closes with a frame story. I call this a ‘bookend’ frame story.

The Eagle Has Landed, for example, opens with the author discovering the graves of German paratroopers in a Norfolk churchyard and trying to find how they came to be there. The bulk of the story is then the tale of those paratroopers, and the final part of the novel goes back to the frame story so the author can wrap the story up and deliver a final twist.

Similarly, 633 Squadron opens and closes in a pub in 1955, whilst the bulk of the novel occurs in 1943.

Out of the FrameAlso fairly common is a frame story which bursts out of its frame. It has the opening frame at the start, but the closing frame is at the end of the second act and then the story continues.

For example, in Spy Game, starring Robert Redford and Brad Pitt, the Chinese have captured Pitt’s character. A frame story of Redford’s character being interrogated links multiple flashbacks to explains Redford and Pitt’s relationship and why Pitt was in China. After the interrogation ends, Redford attempts to rescue Pitt.

What a Frame Story Isn’tA frame story isn’t any time a novel has two timelines or multiple characters or several threads of the story going on at once.

For example, Ian M Banks novel Inversions has two separate, but linked story-lines and alternates between them. Part of the fun of the novel is for the reader to put together the clues and determine how the stories are linked, but there’s no frame story.

What’s the Point of a Frame Story?A frame story can:

Lead the reader into the main storyProvide a second point of viewExplain parts of the storySet up the world of the storyAdd context, meaning, or alternative perspectivesCreate initial suspenseProvide a final twistMake the story seem more believableCall the validity of the story into questionAuthors often use frame stories for stories set in the past to link the past to the present, and so make the story seem more relevant.

Frame story as False DocumentA bookend frame story can also have the same purpose as a false document, adding a preface and afterword, from the ‘editor’ or ‘recipient’ of the story where they explain how the story came into their possession and the likely fate of the author.

They both have the same purpose: helping people suspend their disbelief in the story.

The story Lost Horizon uses a frame story to cast some doubt on the accuracy of the story.

Why Frame Stories are Hard to Get RightThe main thing is that there has to be a point to your frame story.

A ‘glue’ frame story can come across as a transparent attempt to string a bunch of unrelated short stories together.A ‘bookend’ frame story can just seem pointless.A ‘Bursting out of the Frame’ story can end up just going over the back-story before the action starts.For example, Jack Higgins uses the opening frame story in The Eagle Has Landed to set up a mystery that makes the reader want to read on and the closing frame story to deliver a clever twist. This is a great use of a frame story. However, when Frederick Smith tries to do the same thing in 633 Squadron, there’s limited mystery and the final twist is unremarkable. This is a poor use of a frame story.

So, think about precisely why you have a frame story and what it’s adding to your novel. If the answer is “not much”, then ditch it.

How to Write a Frame Story that WorksSo, this is the trick with a ‘bookend’ frame story: use the first chapter to set up a mystery and only fully resolve it in the final chapter. Also, make sure the final reveal isn’t an anti-climax.

The trick with a ‘glue’ frame story is to use it to gloss over the boring bits with a bit of narrative summary.

Make sure the frame story is interesting in its own right. Scheherazade is fighting for her life in the frame story of The Arabian Nights, for example.

Things to DoMake a note of some of your favourite novels or movies that have frame stories.Identify which type of frame story they used.Identify which of those frame stories worked and which didn’t and think about why.Consider if any of your own work would benefit from a frame story:Could you link some of your short stories together with a ‘glue’ frame story?Might a ‘bookend’ frame story be useful for your novel or screenplay?Might a ‘false document’ frame story help your readers suspend their disbelief?Experiment with a frame story for one of your own stories.Help!If you need help with your frame story or any other aspect of your writing, please email me. Otherwise, please feel free to share this article using the buttons below.

Original article How to Write a Frame Story that Works, posted at Graeme Shimmin, spy thriller and alternate history writer

April 21, 2023

633 Squadron – Novel and Movie Review

From an original article 633 Squadron – Novel and Movie Review, posted at Graeme Shimmin, spy thriller and alternate history writer

633 Squadron, written by Frederick E. Smith and published in 1956, was the source novel for the classic 1963 war movie of the same name. Although it’s not a spy novel, it does feature RAF special operations and the Norwegian Resistance.

633 Squadron: TitleThe title uses the protagonist archetype, ‘633 Squadron’ being the fictional Royal Air Force unit who carry out the mission the novel depicts.

(For more on titles, see How to Choose a Title For Your Novel)

633 Squadron: LoglineWhen the Norwegian resistance discovers a threat to the D-Day landings hidden in an impregnable fjord, an elite Royal Air Force squadron undertakes a suicidal mission to destroy it.

(For how to write a logline, see The Killogator Logline Formula)

633 Squadron: Plot SummaryWarning: my reviews contain spoilers. Major spoilers are blacked out like this [blackout]secret[/blackout]. To view them, just select/highlight them.

It’s the 1950s in Yorkshire, England. In a pub near an old RAF airbase, the publican talks to a couple of American and English pilots who’re interested in the wartime exploits of the legendary 633 Squadron. In particular, they want to hear about the “Svartfjord Operation”. Also in the bar and listening in is a stranger. The publican, who has been writing a book about the squadron, tells the pilots the story…

Now it’s 1943. 633 Squadron flies their Douglas A-20 Boston light bombers in to the airbase for the first time. Wing Commander Roy Grenville, a decorated war hero, leads the squadron.

A Norwegian resistance leader, Erik Bergman, arrives at the squadron to help it with a special mission, bringing his sister, Hilde, with him. Bergman insists on going on a shipping strike off the coast of Norway, flying with Grenville. The mission is a success, although the Germans shoot two aircraft down.

Gilibrand, an extrovert Canadian pilot, starts an affair with the local barmaid. Grenville meets Hilde and finds himself attracted to her. Adams, the intelligence officer, realises he is growing apart from his wife, who’s also staying in the pub.

A few days later, Granville and Bergman fly a reconnaissance mission over the Svartfjord, a fjord in Norway. German fighters ambush them, injuring Bergman.

TrainingBack home, the squadron converts from its Bostons to the brand new and far superior de Havilland Mosquito.

The Wing Commander reveals the squadron is to attack a target at the end of the Svartfjord. Because of the mountains, the only way to attack the target is to fly along the fjord. However, there are a lot of anti-aircraft guns along the fjord, making that approach suicidal. The Norwegian resistance will have to destroy them just before the attack. Bergman flies back to Norway to organise the attack on the guns.

The squadron trains in Scotland, flying up a glen that’s similar to the fjord and dropping their bombs on a target that requires precise flying to reach.

Gillibrand is angered when the barmaid he’s having an affair with takes pity on his young navigator while Gillibrand is away seeing one of his other girlfriends. He deliberately attacks a flak-ship to scare the navigator who is hit by shrapnel and dies. Gillibrand is mortified.

ProblemsThe Germans capture Bergman and take him to Gestapo headquarters. Since Bergman knows too much, the Wing Commander orders the squadron to bomb the Gestapo building. However German fighters ambush the squadron and they can’t complete the mission. The Wing Commander orders them to attack again, but Grenville refuses. Eventually, Grenville agrees to attack the building alone after learning the reason for the attack. He succeeds in destroying it, but is convinced that Hilde will hate him when she finds out he killed her brother and so he tries to avoid her.

The Germans send a squadron of their own fighter-bombers to attack 633 Squadron’s airfield. Gillibrand sacrifices himself to prevent the attack destroying the squadron. Worried that the attack means the Germans have discovered the plan to attack Svartfjord, the Wing Commander brings the attack forward.

The Wing Commander briefs the pilots. After flying along the fjord, the crews will have to drop their bombs under an overhanging rock outcrop, in the hope of blasting it loose, so it falls, burying the target.

On the eve of the attack, sick with guilt about killing Bergman, Granville breaks off his affair with Hilde by pretending he has a fiancé in London.

The AttackThe Norwegian resistance fighters’ attack doesn’t happen as they’re all arrested the night before the attack. This leaves the anti-aircraft guns operational, and so the Wing Commander orders the squadron to return as the mission will be a deathtrap…

However, [blackout]Granville and the rest of the squadron volunteer to attack despite the risk. The waiting anti-aircraft guns and Luftwaffe fighters shoot most of the squadron’s mosquitoes down, but several aircraft manage to get their bombs on target, and eventually the outcrop collapses, destroying the target.[/blackout]

Injured, [blackout]Granville crashes his mosquito, but he survives and becomes a prisoner of war. The mission is a success, though at high cost.[/blackout]

Back in the pub [blackout]it turns out the publican is Adams, and Hilde, who has not seen Granville since he survived the mission, regularly visits and is currently staying with him. Finally, Adams realises that the stranger who has been listening to his story is Granville, who has returned in the hope of reuniting with Hilde.[/blackout]

(For more on summarising stories, see How to Write a Novel Synopsis)

633 Squadron: AnalysisPlot633 Squadron has a straightforward Mission plot (see Spy Novel Plots). The squadron receives the mission of destroying whatever’s lurking at the end of the Norwegian fjord and gets on with the job.

The ‘Mission’ PlotMacGuffinThe Protagonist:

Is given a mission to carry out by their Mentor.Will be opposed by the Antagonist as they try to complete the mission.Makes a plan to complete the Mission.Trains and gathers resources for the Mission.Involves one or more Allies in their Mission (Optionally, there is a romance sub-plot with one of the Allies).Attempts to carry out the Mission, dealing with further Allies and Enemies as they meet them.Is betrayed by an Ally or the Mentor (optionally).Narrowly avoids capture by the Antagonist (or is captured and escapes).Has a final confrontation with the Antagonist and completes (or fails to complete) the Mission.

The target in 633 Squadron is a good example of a thing-that-must-be-destroyed MacGuffin (see What is a MacGuffin for more explanation of MacGuffins). The target is such a MacGuffin that the squadron’s aircrew are not even told what it is, just that it’s a “vital target”.

This is actually realistic, as aircrew in WW2 were often not told what the target really was. For example, according to veterans of the Peenemünde raid, even their commanding officer didn’t know what the target was, only that it was extremely important and if they didn’t destroy it, they’d have to keep trying until they did. The crews didn’t find out until after the war that Peenemünde was the test site and factory for the V1 and V2 rockets.

StyleThe writing in 633 Squadron is competent, no-frills, journalistic, stuff. Which is fine, as it isn’t a literary novel, it’s a straightforward plot-led military thriller, and a quick, easy read. The only surprise is that the climactic attack only takes up two chapters. I would have expected Smith to have made more of it.

CharactersThe characters in 633 Squadron are standard war-thriller stock characters. The officers are all either charismatic ‘born leaders’ or ‘by the book’ martinets. The pilots are all devil-may-care or morose. The Norwegians burn with hatred for their Nazi occupiers. All the ground crew are either grizzled veterans or ‘green’ youngsters.

However, there are hints of a realistic portrayal of men under wartime stress. Granville is not quite the cold-hearted, ruthless fighter he appears to be, but a man who hates his job. Gilibrand is openly having affairs with several women, and he’s hiding his navigator’s near-collapse from combat stress.

In the author’s defence, he had been in the wartime RAF and so, presumably, these stereotypical characters are not so far from reality. Still, books like Fair Stood the Wind for France have much better developed characters.

The Frame Story633 Squadron has a frame story set in the mid-1950s, which didn’t seem to add a lot to the story. This made me think about frame stories as a concept and what the point of them is.

A frame story leads the reader into the main story or to provide a second point of view to explain parts of the story, and Frederick Smith used it for both of those reasons. He uses the opening frame story with its modern (for the time) characters to lead the reader into the story. And the closing chapter enables him to quickly summarise the fates of the surviving characters and throw in a mild twist. The revelations in the final chapter are not exactly earth-shattering, they just give the story a happier ending.

Reality: RAF Precision AttacksWhat’s all this about Star Wars being based on 633 Squadron?During WW2, the RAF carried out many extremely low level, highly accurate raids using de Havilland Mosquitoes, such as the attacks on the Dutch, Norwegian and French Gestapo headquarters and Operation Jericho, an attack on Amiens prison. Perhaps though, 617 Squadron’s attack on the German dams and on the German battleship Tirpitz in a Norwegian fjord also inspired the novel.

Yes, it’s true, but only up to a point. The whole Star Wars movie isn’t influenced by 633 Squadron, just the ‘trench run’ sequence at the end. The climatic attack in Star Wars: A New Hope is very, very similar to the one in 633 Squadron:

A squadron of fighter-bombers.Flying through a deep fjord/trench.Fired on by anti-aircraft guns.Attacked by enemy fighters.Suffering heavy casualties.Delivering a precise strike that completely destroys the target.633 Squadron: My VerdictStraightforward flying adventure. Old-fashioned, but fun.

633 Squadron: The Movie

Walter Grauman directed a movie of 633 Squadron in 1963, with Cliff Robertson starring.

The movie is broadly true to the novel, but it’s hugely truncated, and drops the frame story and all of the subplots except the romance with Hilde. The most unlikely change is that Squadron Leader Granville becomes an American named Grant. Also, without the frame story, there’s no happy ending.

The back projection of the pilots in the cockpits and the sequences using model aircraft are both dated. The air-to-air photography, using five airworthy de Havilland Mosquitoes and a couple of French-built Messerschmitt trainers disguised as fighters is terrific though. Scarcely believably, the film-makers deliberately destroyed a Mosquito during the making of the movie in a simulated crash sequence, a tragic loss given that there are now only four airworthy Mosquitoes left.

The movie also features an iconic musical score by Ron Goodwin who also wrote the music for Where Eagles Dare and The Battle of Britain.

633 Squadron: The SequelsHaving found success with 663 Squadron, Frederick Smith stuck to the knitting, writing nine sequels over the next forty years. They are all called 633 Squadron: Operation [Something] and are all very similar in premise to the original: the Resistance reports that something needs blowing up and 633 Squadron get the job of blowing it up. The targets include secret weapons, bridges and trains full of prisoners.

The 663 Squadron movie also had a spiritual successor: the low-budget ‘homage’ Mosquito Squadron, which reused a lot of 633 Squadron’s flying sequences in a very similar story.

Want to Read or Watch It?Here’s the trailer:

The 633 Squadron novel is available on US Amazon here and UK Amazon here.

The DVD is available on US Amazon here and UK Amazon here.

Agree? Disagree?If you’d like to discuss anything in my 633 Squadron review, please email me. Otherwise, please feel free to share it using the buttons below.

Original article 633 Squadron – Novel and Movie Review, posted at Graeme Shimmin, spy thriller and alternate history writer

December 17, 2022

Is AI-Generated Art Ethical?

From an original article Is AI-Generated Art Ethical?, posted at Graeme Shimmin, spy thriller and alternate history writer

You’ve heard about AI-generated art. Maybe you’ve even played with some of the commercially available AI art tools. But are we really artists if the AI is doing much of the work? Should we be embracing AI-generated art or rejecting it? Is AI-generated art really art at all?

Let’s find out.

How Do AI Art-Generators Work?AI art-generators grew out of image recognition programs.

The developers trained the image recognition programs by showing them millions of images and descriptions of those images. The programs absorbed this information in order to classify what things look like. Eventually, the AIs could ‘understand’ similar images and what they represented.

So, for example, they knew what an aeroplane looked like. More impressively, when shown a new photograph, they could say whether it was of an aeroplane or not.

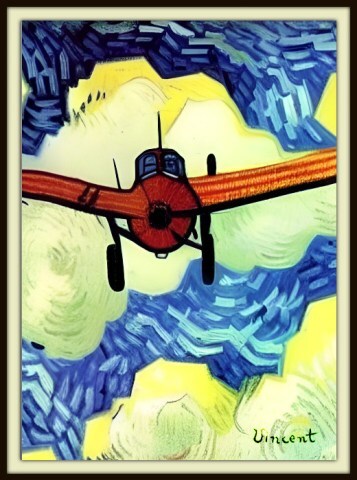

Image generators built on this image recognition model, but reversed the process. So, because the AI knew what an aeroplane looked like, it could output an image of an aeroplane. For example:

An AI-generated image of an aeroplane

Although this is identifiable as an aircraft, which was good enough for a recognition program, it doesn’t really work aesthetically. It’s distorted and there’s two engines on one wing and only one on the other, for example. So, there was a way to go.

But the things that an AI can recognise are not just objects like aeroplanes, it’s also concepts, styles, anything really, and that’s where it gets interesting thing from the point of view of an artist.

The eureka moment was when the developers realised they could ask the image generators to combine objects and concepts. For example, they could ask the AI to output an image that looks like an aeroplane, and looks like a Van Gogh painting:

The image is entirely AI generated. I just added the frame and the signature.

This was when it became possible to create art using AI.

But is it a Good Thing?Some people say that pictures like the one above either just aren’t art, or that using AI to generate art is somehow wrong. The arguments often used are:

AI-generated art isn’t real art.There’s no artistic skill involved in creating the picture.AI-generated art is soulless. It has no emotion or artistic process.Any AI generated art is by its method of production, derivative, unoriginal and banal.AI-generated art just isn’t very good.AI-generated art will destroy the livelihoods of real artists.Let’s explore some of those issues.

AI-generated Art Isn’t Real ArtThat AI-generated images are not art at all is not a sustainable argument.

Artists have presented innumerable unlikely things as art. Marcel Duchamp created artworks using unaltered everyday objects, for example.

What makes anything ‘art’ is entirely subjective, and it’s impossible to identify ‘real’ art.

AI-generated Art Lacks Artistic SkillIf an AI is generating the picture, then clearly, the artist isn’t supplying as much of their own technical ability. There’s potentially no technical skill at all involved.

But then again, did Tracey Emin use much technical ability to put her bed in an art gallery? Does photography lack artistic skill because you don’t need the same hand-eye-coordination to take a photograph as you do to paint a picture?

Art can be powerful, emotional, and exciting without being difficult to produce. Damian Hirst’s assistants produce his spot paintings by the dozen on what amounts to a production line, but they still speak to lots of people.

This goes to show that technical ability doesn’t define artists, and that art is not just about how hard it is to produce. The AI might facilitate the work, but it’s still a product of the artist. Just like a photographer using a camera, the AI augments human creativity rather than replacing it. The role of the artist is like a photographer choosing images that suit their vision and discarding those that don’t.

I’d also argue that removing technical ability from content creation democratises art. Art doesn’t have to be produced for the rest of the world. People can produce images for their own pleasure. If they want to do that by supplying an idea to an AI generator, picking the image that suits their vision and then tinkering with it in Photoshop, how is that wrong?

AI-Generated Art is SoullessAgain, this is entirely subjective. It’s true that until the invention of conscious AI, they will lack intentionality, but philosophical questions about concepts like intentionality are notoriously hard to formulate. Which reminds me of the Turing test, which is more complex and subtle than people realise.

Turing proposed that the question “Can machines think?” requires a definition of what “thinking” is, which is philosophically difficult. He proposed a more pragmatic question: “Can machines do what we (as thinking entities) can do?”

His test then proposed that if the responses an AI gave to questions were indistinguishable from the responses humans gave, then the AI was, for all practical purposes, alive.

In the same way, I propose that “Can machines produce art?” requires a problematic definition of what “art” is. Instead, we should ask a more pragmatic question: “Can machines produce art as we (as artists) can?”

If an AI can produce art that’s indistinguishable from human art, then the AI is, for all practical purposes, it’s an artist.

AI-Generated Art is DerivativeThere’s some truth in this. AI-generated art is unlikely to be startlingly original and innovative. At the moment at least, no AI will invent its own school of the Avant Garde. At least until AI gains true sentience, no AI is going to sweep the art world with a ground-breaking trend like cubism or impressionism…

…but then again, neither are the overwhelming majority of artists.

AI-generated Art Just Isn’t Very GoodIt’s certainly true that AI-generated images can be odd.

This isn’t necessarily a problem if the artwork is supposed to be surreal, but the more representational the artwork, the less likely it is that an AI can produce it without errors. For example, human figures with anatomically impossible bodies are very common.

In my experience, for every image that’s halfway decent, an AI generates a dozen that are unusable. Even the usable images need a human artist to edit them to make them more aesthetically pleasing, also known as ‘fixing them’. Occasionally one comes out perfectly, but most only have potential, along with several problems, such as misshapen bodies, odd faces and colours not being aesthetically pleasing.

This is where the human artist using the AI comes in. Selecting the images with promise is the role of the human artist, just as it is for a photographer, and the artist then has to manipulate the AI-generated image in Photoshop or a similar tool to make it work.

As long as a human has to select and edit the AI-generated images, i.e. until AI gains true sentience, AI art generators are simply tools that human artists can use, aids that help to create visual images.

In this way, AI art generators are analogous to cameras. A photographer can use a camera to take snaps, or they can use it to make superb art. Similarly, an artist can use AI to produce images that are banal or that are incredible.

An ExampleHere’s the process I used recently to make a book cover:

I doubt this is any more true than that Photoshop destroyed the livelihoods of artists. Remember, the skill of the artist is not just in the production of images, it’s the selection of meaningful images.

Also, computers and robots have already affected lots of jobs. For example, AI drivers will probably replace human taxi and truck drivers soon. Why should artists be exempt from this trend? To announce that artists can’t have their jobs changed by computers seems like special pleading.

Ultimately, art has always been a difficult way of making a living, and that’s unlikely to change. AI tools might actually help if they speed the artist’s process so they can make and sell more art.

ConclusionI’ve tried to argue in this article that, at least until AI gains true sentience, AI art generators are simply tools that human artists can use, aids that help to create visual images.

I’ve suggested that although the argument that AI-generated art is derivative has some weight, the other arguments against AI-generated art are questionable. They suggest a narrow approach to what art is and what the role of the artist is.

In the end, it seems hard to argue that AI-generated art will have any greater effect on artists than the invention of photography did. Rather than damaging art, AI, like photography, may open new fields for the artist. We can integrate AI into our artistic process where appropriate, or we can decide not to, just as many artists don’t use cameras.

Original article Is AI-Generated Art Ethical?, posted at Graeme Shimmin, spy thriller and alternate history writer

December 12, 2022

Why You Should Join a Writing Group

From an original article Why You Should Join a Writing Group, posted at Graeme Shimmin, spy thriller and alternate history writer

So, you’ve heard about writing groups? Maybe you’re even thinking of joining one. Good, because if you want to write and publish a novel, then joining a writing group is one of the best things you can do.

Why I’m Writing ThisFrom time to time (okay, all the time) I get messages like this:

Dear Graeme,

I’ve written a novel, but despite sending loads of queries out, I keep getting rejections. The publishing industry is so biased against people like me! Do you have any hints or tips about how to get my writing published? I’d appreciate any help so much. Thank you!

Regards,

Mr/Ms Aspiring Author

Now, there’s a lot of hurt in these messages, and I sympathise. Having said that, it’s incredibly hard to get published, and rejections for a beginning author with no track record are extremely common. In fact, when I was writing my article investigating the myths and reality of publishing, I made a startling discovery: literary agents reject over 99% of the manuscripts they’re sent.

That’s because, unfortunately, most aspiring authors are not producing publishable work. Most aspiring writers are prematurely focussing on getting published, when what they really need to do is focus on producing publishable work. So, the first thing you need to do as an aspiring writer is ask yourself what you’ve done to get feedback on your writing.

Okay, the people who contact me often say, how about you give me some feedback then, Graeme?

Now, I’d love to support everyone who asked me for help with their writing. Unfortunately, if I did, I’d not only have no time for my own projects, but I’d have no time for eating or sleeping. It’s just not an option.

What I can do though, is offer the next best thing, and so this is the advice I give to the writers to contact me:

Advantages of Writing Groups

Hi Mr/Ms Aspiring Author,

The absolute best thing you can do for your writing is to join a writing group. They’re great for supporting you and really help you improve your skills.

Best wishes,

Graeme.

But why do I think writing groups are so useful? Well, they have a bunch of advantages:

Raising Your GameMany aspiring authors only show their work to a handful of friends and family. That’s not great because they:

Don’t want to hurt or upset you.Can’t articulate what it is they like or dislike about your writing.Have no experience of critiquing people’s writing.So, you won’t have a realistic idea of the level your writing is at, and you won’t know how to improve.

If you join a writing critique group, you’ll likely discover that, although your work has strengths, it also has weaknesses. This is, in fact, the entire point of a critique group: to identify where you can improve your writing. You need to have the right attitude though, something that I outlined in this article:

Encouragement and Networking

Just being with other writers who understand what it’s like being a writer and who take you seriously can provide a lot of encouragement. Being with other writers avoids the feelings of being an outsider and ‘not knowing where to start’. And other writers can tell you about their experiences and what worked for them.

Deadlines‘Write every day’ is classic advice, and it’s not wrong. But how do you find that motivation? Well, a writing group can help, because the group meeting provides a deadline to get a version of the story ready.

If you write regularly, then you’ll produce more work and if you have a deadline, then you’re more likely to get work finished. These are both good things.

Writing Group = Social GroupHaving a like-minded group of people with a reason to meet up with is always good, and who doesn’t want more friends? The more you get out of writing, the better you’ll write.

Disadvantages of Writing GroupsPossible DiscouragementHow well a writing group gives and takes criticism is vital to its success. That’s because it’s easy to slip into being too negative, especially in online writing groups. Other people, while meaning well, might not ‘get’ your work. To avoid possible discouragement, I’d advise you to find a writing group that has a policy of constructive criticism as explained above.

Learning to deal with criticism as an author can be hard. However, some people find any kind of criticism distressing and just can’t accept any feedback, however well-meaning. If you are that kind of person, then it’s going to be tough to join a writing group. It’s also going to be tough to get anywhere in publishing, so perhaps it’d be best if you just self-publish your book.

Personality ClashesWriters can be touchy and emotional people. Even so, the only problems I’ve ever seen in writing groups were about politics. Well, not the only problems, but most of them. To avoid problems, my group makes it a rule that we’re apolitical. We disallow criticism of the politics, rather than the literary quality, of people’s work.

However, occasionally writing groups become cliquey and relationships can break down, at which point the only option is to leave and find a new group.

The Blind Leading the Blind?Some people question how useful a writing group whose members are all unpublished is. Do other aspiring writers know enough about writing to provide useful critique?

I’ve never found it to be a problem, because it’s a lot easier to critique other people’s work than to produce your own. Sure, some people’s critiques are more incisive than others. Still, most people can articulate what they liked and didn’t like about a story, and that’s always useful.

And even if someone really isn’t that switched on, their critique still gives you information on the reaction that average readers might have. For example, if they’ve misunderstood the premise of your story, then you might need to make it clearer.

But What If They Steal My Idea?Worrying about other people stealing your idea is something only new writers do.

See my article on how to copyright a story for why your work being stolen is not something you need to worry about.

Types of Writing GroupThere are two main types of writing group: groups where people do writing exercises, i.e. a writing workshop group, and groups where people submit their work for feedback, i.e. a writing critique group.

There are also two ways for writing groups to get together: real life and online.

Writing Critique GroupsIn a writing critique group, the members don’t write at the meetings. They write in their own time and then submit their work to the group meetings for constructive criticism. This feedback is your best opportunity to improve your writing.

If the people in the group understand the genre you write in, it makes their critiques even more useful because they understand the genre conventions. For example, if you’re writing sci-fi or fantasy, then you’ll be best joining a speculative fiction writing group.

If the group expects you to read your work out, then you’ll have to be comfortable with that. Some writers love to read their work out in front of a room full of people, others are uncomfortable. I’ve read my work out innumerable times now, and though I was nervous the first few times, I became more confident. I’ve also written an article full of public speaking tips for authors to help.

Writing Workshop GroupsIn a writing workshop group, the members write at the meetings. The participants either do writing exercises, or they co-write, i.e. sit and work on their own writing, but with others around.

Writing workshops are great for encouraging you and helping you concentrate on writing.

As there’s little to no critique in a writing workshop group, it won’t help you improve your writing as much. Perhaps, though, just being with other writers, doing writing exercises and getting words down on the page will help you progress.

Real Life Writing GroupsAlthough I said I didn’t have time to support everyone, there is one way to get me to critique your work. That’s to join my writing group, Manchester Speculative Fiction, and come along to meetings. To do that, you’ll have to live within travelling distance of Manchester, UK, though.

And that’s the main problem with real life writing groups. Unless there’s one in your area, it’s not an option. Of course, you could always try starting your own group. That’s a whole other article though.

Online Writing GroupsOf course, it’s possible to join a writing group that meets only online, using text, audio or video chat. This has the huge advantage of interacting with people from potentially all over the world who focus on your genre. For example, I’ve posted some of my writing on alternatehistory.com and found the feedback encouraging and useful. I also posted on the critique website YouWriteOn, winning their book of the year prize (however, YouWriteOn is currently ‘on hiatus’).

Online groups have the disadvantage of being more impersonal, which can lead to harsh critiques. Personally, I find any kind of critique useful, but you’ll have to decide if that suits you.

How to Find a Writing Group That Suits YouTo find a real life writing group, try searching online for ‘writing group in [your area]’ and see what comes up. You’ll likely be able to find a local writing group and, depending on where you live, you may have a choice. A nearby real-life writing group will be easier to get to. However, a writing group that’s further away or online might be better if it specialises in the genre you write in.

Alternatively, try asking at the local library or community centre, as they usually know what writing groups exist in the area.

Things to DoRealise just how hard it is to gain commercial publication.Realise that you need to focus less on getting published and more on writing publishable work.Consider how best to raise your writing game.Investigate writing groups in your local area and online.Find a writing critique group where you can get constructive feedback.Find a writing workshop group to encourage you to writeJoin the groups, attend some meetings and decide if they are for you.Agree? Disagree?If you’ve got any thoughts on writing groups, please email me. Otherwise, please feel free to share the article using the buttons below.

Original article Why You Should Join a Writing Group, posted at Graeme Shimmin, spy thriller and alternate history writer

September 20, 2022

Red Sparrow: Movie Review

From an original article Red Sparrow: Movie Review, posted at Graeme Shimmin, spy thriller and alternate history writer

Red Sparrow released in September 2017, starring Jennifer Lawrence, and directed by Francis Lawrence, is a noirish espionage-thriller about a Russian ballerina forced to become a seductress for Russian Intelligence.

Red Sparrow: TitleThe title is reference to the protagonist, ‘Red’ being a common slang term for the Russians and ‘Sparrow’, a term for an agent using seduction to entrap enemy sources.

(For more on titles, see How to Choose a Title For Your Novel)

Red Sparrow: LoglineAfter a ballerina witnesses an assassination, she is given two choices: death or become a state-sponsored seductress. Tasked with manipulating an American spy, she attempts to play both sides in order to gain revenge for her degradation.

(For how to write a logline, see The Killogator Logline Formula)

Red Sparrow: Plot SummaryWarning: My plot summaries contain spoilers. Major spoilers are blacked out like this [blackout]secret[/blackout]. To view them, just select/highlight them.

It’s the modern-day. In Moscow, Dominika Egorova is a ballerina for the Bolshoi ballet. After a career-ending injury, she loses her position and is in a desperate situation. Her uncle, who works in Russian intelligence, offers to help her if she does a job for him: seducing an opposition politician and then switching his phone so they can monitor him. But when Dominika gets the politician alone, an assassin kills him. Dominika’s uncle had lied to her.

General Korchnoi, who’s high up in Russian Intelligence, insists they eliminate Dominika as a witness, but her uncle suggests another possibility. He’s impressed by how Dominika seduced the politician and offers her a position in Russian intelligence doing similar work. With no real choice, Dominika accepts.

Meanwhile, a CIA operative in Moscow, Nate Nash, meets with a mole in Russian intelligence, codenamed ‘Marble’. When Russian cops stumble on the meeting, Nash has to blow his cover to enable Marble to escape. Nate returns to the USA in disgrace. Marble refuses to work with any other CIA agents, though, and so the CIA sends Nate to Budapest to regain contact with him.

In Russia, Dominika trains as a ‘Sparrow’. The training involves abusive and degrading treatment, which Dominika resists. Despite her stubbornness, her uncle decides to use her as an agent. He sends her to Budapest to seduce Nate, hoping he will tell her the identity of Marble.

The MissionIn Budapest, Dominika shares an apartment with another sparrow, Marta. Marta, without orders, has seduced the chief of staff of a US Senator. Dominika tells her uncle about the unauthorised plan and he executes Marta for her transgression.

Dominika contacts Nate and immediately admits she is a Russian agent and that her mission is to discover Marble’s identity. She offers to become a double agent for the CIA.

Under CIA control, Dominika meets with the American Senator’s chief of staff, receives the intelligence she’s selling, and switches it for fake information. The CIA close in to arrest their traitor, but she’s run over by a van before they can apprehend her.

Suspecting that Dominika betrayed the operation to the CIA, Russian intelligence torture her. She refuses to admit anything and eventually convinces her uncle that the fact that her own side has treated her so brutally will make her completely credible to Nate.

Dominika’s uncle allows her to return to Budapest. There, she tells Nate that she wants to defect to the USA. He agrees to help her.

MarbleLater, [blackout] Dominika finds another Russian operative trying to beat the identity of Marble out of Nate. She pretends to join in, but then attacks and kills the Russian. She and Nate are both badly injured in the fight and end up in hospital. At the hospital, General Korchnoi reveals he is Marble and tells Dominika to unmask him. This triumphant achievement will allow her to take his place as the CIA’s mole.[/blackout]

Dominika [blackout] contacts the head of Russian intelligence and reveals the identity of Marble. The Americans then arrange a spy-swop: Dominika for Marble. However, rather than naming General Korchnoi, Dominika frames her uncle as Marble in revenge for the terrible ordeal he has put her through. During the handover, a Russian sniper kills the uncle.[/blackout]

Russian intelligence [blackout] celebrates Dominika as a hero. Later, at home, she receives a phone call, implying that she’s still in contact with Nate.[/blackout]

(For more on summarising stories, see How to Write a Novel Synopsis)

Red Sparrow: AnalysisPlotRed Sparrow has a Mission plot (see Spy Novel Plots ).

The ‘Mission’ PlotThe Protagonist:

Is given a mission to carry out by their Mentor.Will be opposed by the Antagonist as they try to complete the mission.Makes a plan to complete the Mission.Trains and gathers resources for the Mission.Involves one or more Allies in their Mission (Optionally, there is a romance sub-plot with one of the Allies).Attempts to carry out the Mission, dealing with further Allies and Enemies as they meet them.Is betrayed by an Ally or the Mentor (optionally).Narrowly avoids capture by the Antagonist (or is captured and escapes).Has a final confrontation with the Antagonist and completes (or fails to complete) the Mission.

This archetypal plot is complicated in that it’s not clear who the Antagonists are. Dominika‘s uncle, Russian Intelligence and the Americans all seem to be the Antagonists at times, as Dominika tries to survive their machinations.

Red Sparrow – Black Widow – NikitaA Russian ballerina trained at a brutal spy school to become a seductress and spy? What does that remind me of? Yes, it’s the same back story as Marvel’s Black Widow.

Red Sparrow is also reminiscent of the classic French movie Nikita (and its loose remake Anna) with a spy agency forcing a troubled young woman to become a seductress/assassin.

However, Red Sparrow is not a Black Widow or Atomic Blonde style action movie, with spectacular stunts, but a wannabe slow-burn Le Carré style spy-movie. It’s a hell of a lot darker and more ‘realistic’ than the superhero-tinged Black Widow. Some of the violence is brutal, and the sex scenes are unpleasant, too. If you watch Red Sparrow to see Jennifer Lawrence stripping off, it will disappoint you.

And although Red Sparrow is comparable to Nikita in its noir edge, the comparison is not flattering: Nikita is a far superior movie.

Red Sparrow: The Ending ExplainedThis section contains massive spoilers, obviously.

To be honest, the ending is all a bit of a deus ex machina and doesn’t actually make a lot of sense.

Dominika’s problem was she was supposed to make Nate fall in love with her, so he’d tell her the identity of Marble. At the same time, Nate was trying to make Dominika fall in love with him so she’d defect.

The deus ex machina occurs when Marble reveals himself to Dominika as the mole out of nowhere and for no discernable reason. That means the conflict at the heart of the story is simply unresolved.

Instead of turning the real Marble in though, Dominika tells the head of Russian intelligence that her uncle is Marble – the evidence being one tumbler with Nate’s fingerprints (which she placed in her uncle’s apartment), a bank account in her uncle’s name (which she opened) and the fake CIA intelligence (which she obtained, not him). This is not very much evidence at all.

Also, Dominika collected those items early in the story, so must have been planning to frame her uncle before she discovered who Marble was, so it doesn’t even matter.

Luckily, the head of Russian intelligence is an idiot and so falls for Dominika’s transparent attempt to frame her uncle and everyone goes home happy… except for her uncle, who’s dead.

It never becomes clear if either, or both, of Nate and Dominika were genuine or they were both just attempting to manipulate each other. However, the final scene implies they are at least still in contact.

Red Sparrow: My VerdictNot sure I quite bought the plot, but the ride is entertaining enough.

Want to Watch It?Here’s the trailer:

Red Sparrow is available on Amazon US here and Amazon UK here.

Agree? Disagree?If you’d like to discuss anything in my Red Sparrow review, please email me. Otherwise, please feel free to share it using the buttons below.

Original article Red Sparrow: Movie Review, posted at Graeme Shimmin, spy thriller and alternate history writer

September 14, 2022

Deus Ex Machina: What it is, Why it’s Bad and How to Avoid It

From an original article Deus Ex Machina: What it is, Why it’s Bad and How to Avoid It, posted at Graeme Shimmin, spy thriller and alternate history writer

In order to understand what a deus ex machina is, first we need to go back in time. In fact, we need to go all the way to Ancient Greece, where the problems storytellers faced were the same as the ones we face today.

Just like in modern stories, in ancient Greece writers liked to give their protagonists lots of problems, because conflict is what stories are all about.

But, in Ancient Greece, there was no TV and no movies, so drama was all about the theatre.

So, imagine you’re an Ancient Greek playwright. You’ve got your theatre, you’ve got your actors and you’re working on your play. Now all you need is an ending. Trouble is, your script piles up so many problems up for the protagonists that you can’t think how to get them out of the pickle they’re in.

And, even worse, the play opens in two day’s time…

What to do? What to do?

‘Ah hah!’ you say. ‘I’ll get Zeus to come down from Mount Olympus and sort things out. People love the gods, so that’ll work, right?’

So you get the theatre to rig up some pulleys to lower ‘Zeus’ down from the rafters to get the protagonists out of whatever sticky situation you’ve got them in, resolve the story’s conflict once and for all, and wind the play up quick before the audience starts asking for its money back.

The Ancient Greek phrase for this was apò mēkhanês theós, which literally means ‘god out of the machine’ The ‘machine’ here is the pulleys or crane or whatever that lowered ‘Zeus’ to the stage.

Even then, it was criticised. Aristotle said:

Bring on the RomansThe resolution of a plot must arise internally from the character’s previous actions. The author should make their characters do things that are either necessary or probable from what the audience knows of them. Similarly, the ending of a plot should come about because of the plot not from a contrivance.

When the Romans came along, their writers had exactly the same problems and used the same solution (different gods, though, obviously). And when you translate apò mēkhanês theós into Latin, you get… deus ex machina.

And this time, the name stuck. It’s been deus ex machina ever since Julius Caesar was a boy.

Yeah, it’s that old.

In fact, it’s so old that people already regarded it as a bit of a weak way of ending a story before Jesus was born.

Everyone’s a critic, huh?

Modern Deus Ex MachinaSo, what’s this got to do with today’s writers? There aren’t any gods being lowered to the stage at the end of movies these days, surely?

Wanna bet?

Nowadays, a deus ex machina refers to any previously unmentioned external force suddenly and unexpectedly resolving a seemingly unsolvable story problem. The ‘external force’ is a solution outside the control of the characters. It can be an event, character, ability, or object. It could even be a god, though it usually isn’t.

Aside: The Plural of Deus Ex MachinaDeus Ex Machina: RulesStrictly, it’s Dei Ex Machina (Gods in Machines) but people use Deus Ex Machinas too. That’s kinda wrong, but we’re not Latin scholars, right?

There are some rules about what makes a deus ex machina:

Only a solution to a problem can be a deus ex machina.An unexpected event that makes things worse for the protagonist is a plot twist.A sudden revelation that changes the audience’s understanding of the story or a character is a reveal.A deus ex machina has to be unexpected.If the solution is set up earlier in the story, then when it saves the day, it’s a pay off.The protagonist’s plight has to appear hopeless before the deus ex machina intervenes.If there are obvious solutions that the characters ignore, then it’s an idiot plot.A deus ex machina is outside the control of the characters.If the protagonist saves themself through some unlikely improvisation, it’s handwaving or technobable.If the antagonist has an unlikely change of heart, or the unstoppable threat fizzles out, it’s an anti-climax.If the story ends without solving the unsolvable problem, it’s a cliffhanger.What’s Wrong With a Deus Ex Machina?I mean, in reality, unexpected things happen. Passers-by intervene. The police blunder into the serial killer. Stray bullets kill soldiers. People decide things on a whim. Bombs fail to go off. Etc. etc. etc.

Well, that’s true, but even so, I strongly recommend you not use a deus ex machina to get your protagonists out of whatever predicament you’ve got them into.

Why?

It’s CheatingResorting to a deus ex machina suggests the author didn’t think their plot through properly. What they’re saying to their audience is that they couldn’t think of a better way to get their protagonist out of the jeopardy they placed them in. It shows a lack of creativity. It’s inept. And no one likes a cheat.

It Just Doesn’t WorkIt destroys suspension of disbelief and damages the story’s internal logic. It’s a transparent contrivance, and that’s breaking the contract that the writer has made with the reader. Readers love a sudden and unexpected event that makes things worse, but they hate it when a similarly sudden and unexpected event solves problems.

It’s Unlikely to Get PublishedWorst of all, agents and publishers are going to spot your deus ex machina and reject your work. If you self-publish it, critics will dismiss you as an amateur.

Deus Ex Machina in James BondPeople often call Bond’s gadgets dei ex machina, but most of them aren’t. Many of them are incredibly fortuitous, turning out to be exactly what Bond needs to get out of a tight scrape, but the audience knows Bond has them because of the obligatory ‘briefing with Q’ scene where the gadget is set up.

Having said that, some of Bond’s save-the-day gadgets are dei ex machina.

The ski backpack that’s actually a parachute, and the car that turns into a submarine, in The Spy Who Loved Me are dei ex machina, as the screenplay hasn’t set them up.Similarly, the gondola that turns into a hovercraft in Moonraker.Bond’s watch in Live and Let Die also conveniently turns out to have a previously unmentioned built-in circular saw.I would argue though that even these aren’t exactly dei ex machina, as Bond always had gadgets in the previous movies and so the audience expects him to have gadgets and is disappointed if he doesn’t.

There is though a great example of a deus ex machina in the novel of Dr. No, though, because the final sentence in Ian Fleming’s From Russia with Love after Rosa Klebb has mortally poisoned Bond is:

Bond pivoted slowly on his heel and crashed headlong to the wine-red floor.

THE END

Bond is supposed to be dead. So dead that From Russia with Love is the only Bond novel to close with the words, “THE END”.

But From Russia With Love was a huge commercial success, and so Fleming resurrected his hero at the start of Dr No by inserting a (previously unmentioned) “doctor with experience of tropical poisons” who happened to be staying at the hotel.

“He was damn lucky,” as M says.

Well, no, M, it was a deus ex machina…

‘It Was All a Dream… or was it?’Getting your protagonist into some predicament and then they wake up, is such a deus ex machina, such a schoolboy error, that my teacher taught me not to write ‘it was all a dream’ when I was in junior school. Which, come to think of it, was pretty advanced thing to be teaching a seven-year-old, but hey…

The ‘it was all a dream’ ending is unsatisfying because it means that everything that’s happened didn’t really happen, and so the entire story was a waste of the reader’s time. It’s an anti-climax, at best.

Some variations on the ‘it was all a dream’ theme are:

It was all:

A hallucination or supernatural visionAn exerciseOn the holodeckBecause the narrator was unreliable or mentally illWhich isn’t to say you can’t use those plot devices, just don’t hide them. One of the greatest Star Trek: TNG episodes, The Inner Light, is a hallucination, for example. But crucially, it’s up front about it. The viewer knows a ray from an alien probe is making Picard experience the hallucination from the start of the story.

Can a Deus Ex Machina Ever Work?Not really.

There are though, some situations when they’re not as bad.

Sometimes people say a deus ex machina can work in a comedy, because as long as it’s funny, no one cares. Similarly, a story that’s absurdist or surreal may accommodate a deus ex machina better than a realistic story.

Early in a story, the audience will accept coincidences or contrivances more readily than towards the end. That’s because the story is still establishing the world and the characters, and so the audience is more prepared to suspend disbelief.

Similarly, if the main character is in jeopardy twenty minutes into a two-hour movie, the audience knows they’re going to get out of it somehow, but that doesn’t mean they won’t groan a little if a deus ex machina saves them.

How to make Sure Your Story Doesn’t Have a Deus Ex MachinaSo, what to do when you’ve painted your protagonist into a corner, set up an unsolvable problem, or they’re otherwise doomed and with no way out?

Decide how they’re going to get out of it.Go back and edit previous chapters to set that solution up.Once it’s set up, it’s not a deus ex machina any more! You rule!But I Can’t Think of Anything!Okay, it’s certainly possible to write your protagonist into a corner and then get stuck.

But the solution is still not a deus ex machina.

The solution is either:

Come up with something clever.Rework your plot.Don’t be tempted to take the easy (but dumb) way out. Instead, think of something that makes sense and is under the control of the characters. If you immerse yourself in the world of your story, then you’ll think of something. Make your characters deserve their victory!

Things to DoBe aware of what a deus ex machina is.Understand why they’re a bad idea.Write down five examples of dei ex machina in popular novels/movies.Think about how you could change the stories to remove them.Read through your own work and identify if you have any dei ex machina.Think about how to edit your work to remove them.Want to Read More?For more tips on writing a good ending, see How to Write a Story Ending.

The book on story archetypes that I recommend is The Writer’s Journey by Christopher Vogler. It’s available on US Amazon here and UK Amazon here.

Agree? Disagree?If you have any thoughts on the article, please email me. Otherwise, please feel free to share it using the buttons below.

Original article Deus Ex Machina: What it is, Why it’s Bad and How to Avoid It, posted at Graeme Shimmin, spy thriller and alternate history writer

September 1, 2022

Swastika Night: Book Review

From an original article Swastika Night: Book Review, posted at Graeme Shimmin, spy thriller and alternate history writer

Swastika Night was written by Katharine Burdekin and published in 1937 under the pseudonym “Murray Constantine”.

It is remembered primarily as the first novel to portray a world after a Nazi victory—remarkably, Burdekin wrote it before World War Two. It was also one of the first novels to portray a world where misogyny had been taken to the extreme.

Swastika Night: TitleThe title uses a figurative reference to the antagonist archetype, as the swastika is the symbol of the Nazis, whose victory is the premise of the novel.

(For more on titles, see How to Choose a Title For Your Novel)

Swastika Night: LoglineCenturies after the victorious Nazis replaced all historical records, an Englishman discovers a book containing the true history of the world and tries to use it to start a revolution against Nazism.

(For more on loglines, see The Killogator Logline Formula)

Swastika Night: Plot SummaryWarning: my reviews contain spoilers. Major spoilers are blacked out like this [blackout]secret[/blackout]. To view them, just select/highlight them.

It’s 2609 or, on the new calender, Year of Our Lord Hitler 720. The Nazi German and Japanese Empires dominate the world. The world now worships Hitler as a god, co-equal with his ‘father’, God the Thunderer.

The victorious Nazis organise the rest of society on a strict hierarchical basis with the current Führer at the top, below only the god, Hitler. An order of Knights is below the Führer. Next are German men and below them are foreign men. At the bottom of society are women and Christians, who the Nazis regard as no better than animals.

Hermann, a German Nazi, is worshipping in a Hitler Chapel when a choirboy catches his eye. He follows the boy outside, where he loses him but spots an old English friend, Alfred. Despite his indoctrination that he is far superior to any foreigner, Hermann recognises Alfred is a much cleverer and better-educated man than he is, which confuses him.

Hermann and AlfredAlfred is ostensibly on a pilgrimage to the Holy Places of Nazism, but tells Hermann that he is secretly planning the overthrow of Nazism. Hermann scoffs and says that is impossible and unthinkable.

Alfred then claims he has identified the Achilles heel of Nazism: its falsified history, which claims that all other nations were uncivilised barbarians who fell easily before the god-like Hitler. Without the world’s belief in Hitler’s divinity, the Nazis can’t hold the other nations in thrall forever. Therefore, Albert plans to start a rebellion of disbelief.

Alfred also claims Germans can never really be men, because real men can better themselves through talent and hard work. Nazism, in contrast, is captive to the idea that certain people (Knights, Germans) are born better than others. So, Alfred claims, no Nazi can ever be a man, because they can never improve themselves.

Alfred and Hermann argue until Alfred says he is tired and is going to have a rest. Hermann considers killing Alfred for his blasphemy, but finds he can’t. His softness and his failure to uphold his religion make him feel ashamed.

Shortly afterwards, Hermann spots the choirboy attempting to have sex with a Christian girl. Already angry because of his failure with Alfred, and furious that a German boy would defile himself with a Christian girl, he attacks the choirboy.

Alfred hears the noise and intervenes to stop Hermann from killing the choirboy. The girl disappears and they carry the boy to the nearest village where the local Knight, Von Hess, wants to know who attacked the choirboy and why. Hermann tells Von Hess that the boy was defiling himself, which justified beating him. Von Hess queries Hermann’s story and suggests he withdraw it, but ultimately agrees with Hermann’s request to make a deposition justifying his violence.

Von HessAlfred talks with Von Hess, who’s impressed by him and offers to let him fly them both in his private plane, despite Alfred never having flown a plane before. Alfred handles the plane effectively, but whilst landing again, he attempts to avoid some people on the runway and crashes the plane into a hangar. Both men survive the crash and the Knight orders Alfred to report to him in the morning with Hermann.

The next day, Von Hess explains his family has a curse: they know the truth about Hitler. He shows them a picture of the real Hitler, who is small, dark and paunchy. To Hermann’s horror, the Hitler in the photograph is looking lovingly at a young woman.

Von Hess tells them that a few hundred years after Hitler’s life, the Knight’s Council decided that a Hitlerian religion and a hatred of women should replace all historical records.

One of Von Hess’s ancestors opposed this plan but was unsuccessful. For the rest of his life, he secretly wrote everything he could remember about the genuine history of the world. The Von Hesses have been guarding the manuscript, the photograph of the real Hitler and the knowledge of what women were really like ever since.

Hermann can barely accept this information, but it energises Alfred. Hermann says he can hear no more and wants to kill himself, as everything he believes is a lie.

Von Hess and Alfred discuss why women didn’t resist their de-humanisation and how that has led to the current crisis of fewer and fewer women being born. Alfred suggests women abased themselves to please men, but men despised them even more for it. Allowing themselves to be treated like animals has crushed womens’ souls, which is why they don’t give birth to girls.

Von Hess says that, as far as he knows, the Japanese Empire has followed the same path and as a result has the same birthrate problem. Unless something changes, humanity is doomed.

As Von Hess has no remaining sons—they were all killed in a plane crash—he proposes to hand the record of the world’s history to Alfred. Alfred and Hermann should leave Germany with the book.

Von Hess tells Hermann that the only way he can leave Germany without arousing suspicion is to say that he lied in his deposition that he caught the choirboy attempting to have sex with a Christian. The courts will then find him guilty of trying to destroy the reputation of a German and exile him in disgrace.

EnglandVon Hess gives Alfred the history book. Alfred finishes his pilgrimage, then returns by boat from Hamburg to Southampton with it. He hitches a life to near Stonehenge, where there’s a hidden underground shelter he can keep the book in. After hiding it, he returns home, goes back to work and tells his son about the book. Alfred finds Hermann a job as a farm labourer and the three spend most evenings reading the history book in their hide.

Alfred visits his children’s mother, who has just given birth to a girl. He wonders if he could bring the girl up to be a free-spirited woman, but decides it’s impossible.

Alfred also befriends some Christians who tell him their knowledge of history. Their understanding broadly fits with the history book, although the Christians can’t read and so have passed what they know down verbally, leading to their history becoming garbled.

GhostsMonths later, some German soldiers are walking near the hide when they spot a Christian poaching rabbits. They grab him and he tells them a story about ‘ghosts’ in Alfred’s hide. The soldiers force the poacher to show them where the hide is.

Hearing the soldiers coming, Alfred tells his son to flee with the book while Hermann and he delay the soldiers…

Hermann [blackout]fights the soldiers, who kill him. Alfred tries to talk his way out, but ends up fighting too.[/blackout]

Alfred [blackout]wakes up in hospital, severely beaten and without long to live. His son visits him and tells him the book is safe. It’s hidden with the Christians, who can’t read it but who the Nazis never bother with.[/blackout]

Alfred [blackout]dies, hoping that eventually the knowledge in the history book will spread and his non-violent revolution of disbelief will save humanity.[/blackout]

(For more on summarising stories, see How to Write a Novel Synopsis)

Swastika Night: AnalysisPlotSwastika Night has a Mission plot (see Spy Novel Plots) although there’s no specific ‘Antagonist’ just Nazi-dominated society, and the background to the mission is the bulk of the novel.

The ‘Mission’ PlotIs Swastika Night actually Alternative History?The Protagonist:

Is given a mission to carry out by their Mentor.Will be opposed by the Antagonist as they try to complete the mission.Makes a plan to complete the Mission.Trains and gathers resources for the Mission.Involves one or more Allies in their Mission (Optionally, there is a romance sub-plot with one of the Allies).Attempts to carry out the Mission, dealing with further Allies and Enemies as they meet them.Is betrayed by an Ally or the Mentor (optionally).Narrowly avoids capture by the Antagonist (or is captured and escapes).Has a final confrontation with the Antagonist and completes (or fails to complete) the Mission.

Although it reads like an alternative history to a modern audience, and although the story’s setting is still in the future, Swastika Night is in fact an example of paleofuturism. To the reader, the differences between paleofuturism and alternative history are small, but:

Paleofuturism is an author looking forward to imagine what might happen in the future. Reality has now overtaken that imagined future.Alternative history is an author looking back and imagining what might have happened if the past had gone differently.See What is Alternative History? for a more in-depth discussion of the definition of alternative history.

The History of the World in Swastika NightThere is no detailed discussion in Swastika Night of what has happened over the six hundred years since the Nazis won the war. However, these points become apparent: