Alex Quigley's Blog

November 29, 2025

Teacher professional development is hard!

Every teacher can recite awkward experiences from their teacher professional development past. Pleasing all the teachers all the time, with various approaches, is simply hard work!

Years later, I can still remember my left/right brain training (twice - by the same trainer!), as well as undertaking coaching approaches, and a whole array of different means to develop my practice. Happily, the dubious 'Brain training' has died a death, but the struggle to identify the best methods and content for professional development is still present across the country.

A new research study on professional development, and its impact on student achievement, tackles the muddy area with some interesting results that offer handy insights for busy leaders.

Entitled, '(When) do teacher professional development interventions improve student Achievement? A meta-analysis of 128 high-quality studies', it explores the really variable impact of professional development.

This exploratory research appears to indicate that the number of hours of training was not so significant. It is more a question of quality over quantity. More instructively, the researchers find that there are important principles to engineering more learning from teacher professional development. They identify four principles to apply to designing professional development:

Teacher performance standards: defining what teachers are supposed to learn in the PD and then monitoring that goal. Teacher self-regulation: Encourages teachers to monitor and set their own goals, find time to reflect and manage themselves (with precious time!)Teacher coaching: Sustained support to implement strategies in the classroom, with effective feedback. Teacher cooperation: Teachers exchanging knowledge and feedback so that they learn with and from one another.They found that hours being directly trained wasn't a key determining factor of impact, but that time (tools and support) is obviously necessary to fulfil the above principles.

The active nature of the teacher in the training is obvious. Teachers need clear goals and then need to monitor and plan with those goals in mind. Collaboration and coaching emphasis the sustained social quality of effective professional development. A September training day and a dream just won't cut it!

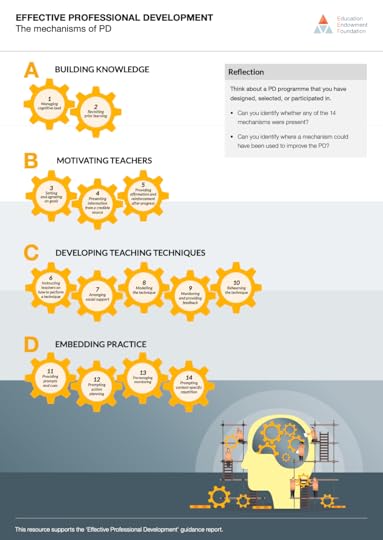

What also struck me about the new evidence is that is enriched and confirmed the seminal review by the Education Endowment Foundation on 'Effective Professional Development'. The 'balanced approach' from the EEF includes a range of 'mechanisms' which have a lot of parallels to the aforementioned research.

The EEF resources add a welcome specificity that can help leaders design professional development that is more likely to lead to a beneficial impact on student achievement. The specific 'mechanisms' are similarly broken down into four areas:

The mechanisms map well onto the principles indicated by this most recent study on teacher professional development.

The key message that attends teacher professional development is that it is very hard to do well! It isn't just about teachers working harder - there is the necessity for leaders to carefully establish and sustain the right climate and support for professional learning.

We must also remember: if so much teacher professional development evidently doesn't have a positive impact on student outcomes, that should give us pause.

This stuff is difficult - but there is progress being made and lots of great practice out there. Happily, the cumulative evidence-base is catching up and it allows leaders to be reflective of what they do, and what their teachers learn.

Related reading:Find the EEF guidance on professional development and resources HERE . Early career teachers may need a clear mental model of the learner. Prof. Dan Willingham makes a good argument HERE . Sarah-Louise Johnson, from Essex Research School, has written a really interesting article on 'Professional development: moving from informing practice to sustaining change' - HERE .November 22, 2025

The 3Rs - Reading, writing, and research to be interested in #73

Metacognition - New and Updated

Metacognition is a well known term but perhaps less well understood for some busy teachers. Education Endowment Foundation guidance on the topic of 'Metacognition and Self-regulation' has always proven popular and now it is new and updated so it is well worth returning to explore.

It is helpful to return to what metacognition is, and what it isn't, and how we might break it down to make useful guidance for busy teachers to enact in classrooms.

In concrete, everyday terms, we use metacognitive strategies all the time when we are undertaking most tricky tasks. For example, if you are travelling to a new venue for work, you put metacognitive strategies in place. You may plan to use a sat nav, or plan a bus route. You check and monitor timings. You may adjust for traffic or late trains. Then you are likely to evaluate whether you'll go the same route again in future.

The EEFs new and updated guidance report (find it HERE) has been updated by a great teams of authors (well done Beverley Jennings, Kirsten Mould and Corine Settle for authoring the newest update) and a team of expert reviewers. It is based on lots of of new research (over 355 studies).

The recommendations are similar to what they have been in the past, with more precise updates on different aspects of metacognition and self-regulated learning:

Metacognition is sometimes criticised for being tricky to pin down - and too multi-faceted to be actionable. It does require multiple recommendations, because it is complex, but that is because thinking and learning is complex and multi-faceted.

I do have sympathy with the notion of getting simple things right, such as getting students' attention and asking precise questions, or checking for understanding with precision, before tackling something like metacognition. However, it shouldn't be an either/or. Alongside getting the precise actions of teaching right, we must help student think, plan, check, evaluate, and take ownership of what they do, and this is the vital stuff of metacognition and self-regulated learning.

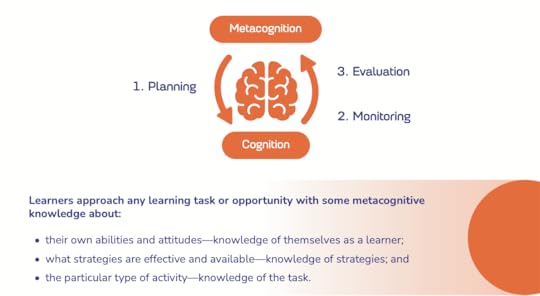

(Page 10 of EEF guidance)

(Page 10 of EEF guidance) Metacognition becomes visible in the classroom if we identify and understand it more precisely. In maths, pupils are often talking non-routine problems that they need to plan, adopt strategies, trial them, adjust, and evaluate. Writing a story in English is full of planning - checking, editing and revising, then evaluating whether you did an effective job. Planning independent revision is crammed full of metacognitive strategies - or not so much for some students who don't manage the process well!

For young children, we may emphasise the self-regulation aspect of the guidance – from keeping calm, thinking and communicating effectively. For the distracted teenager, trying to stick at GCSE revision in a room bursting with distraction, we likely think similarly about the importance of self-regulation.

Understanding metacognition and self-regulation helps teachers understand how to help students navigate these challenges strategically and with metacognitive strategies. It is no silver bullet but it can help. There is substantive evidence that they offer the means to particularly support pupils from disadvantaged backgrounds.

I am also happy to see misconceptions about SEND addressed in the latest guidance update. Insights include:

"Some pupils, including some with SEND, will find self-regulation harder than their peers. Informed by a knowledge of their pupils, teachers may therefore provide additional modelling, adapt the metacognitive questions they ask, or take advice around how to support a pupil to self-regulate in class" (p6)

Metacognition is not some amorphous focus on fuzzy skills, but how we support students to plan extended writing in English, or scaffold planning in history, or evaluate their strategies in maths problem solving.

"There is little evidence of the benefit of teaching metacognitive strategies in generic ‘learning to learn’ or ‘thinking skills’ lessons. Instead, self-regulated learning and metacognition have often been found to be context-dependent—for example, good planning strategies in Key Stage 2 art may have significant differences to planning strategies in GCSE maths." (p35)

Professor Dan Willingham makes a compelling case that teachers need to have a working mental model of how children learn. I think guidance on metacognition and self-regulation can also help to build a clearer notion of how children plan, monitor and evaluate their learning - and it should be part of the working mental model of every teacher.

Do explore the new and updated guidance. New and updated tools will be coming soon too.

November 8, 2025

Feedback: A message in a bottle

Approaches to feedback, such as written marking or 'whole class feedback', are popular classroom strategies that are undertaken daily with students of all ages and stages. But do they truly land with students in the ways we intend? Or is it like a message in a bottle, cast out with no certainty of where, or even if, it will be received?

Feedback is a tricky business. It can be time-consuming, essential to learning, but also unpredictable. Harnessed effectively, it appears to have a big positive impact on learning. But doing it well is hard work and teachers most often don't know if their message has actually landed.

Over the past few years, debates have raged about the relative effectiveness of written feedback versus oral feedback. Given the effort and time-consuming nature of written feedback in particular, teachers have been keen to prioritise oral feedback.

The evidence is rather equivocal, but oral feedback has become increasingly popular as the go-to mode of feedback for time-pressed teachers. Whatever the mode of feedback selected, challenges abound to make it land effectively and prove worthy of teachers, and students', time.

What may be the problem with 'whole class verbal feedback'?A common method for verbal feedback is 'whole class feedback'. Most typically this includes: reading students' work, making notes - such as on strengths, weaknesses and misconceptions - then delivering the feedback verbally to all students at once.

This can save time writing individual comments in books, or convening 1-to-1 feedback (effort and teacher, and teaching, time matter when it comes to selecting feedback strategies).

A key problem is that the students who are most likely to need targeted feedback on their learning do not interpret whole class feedback as relating to them.

Students can suffer from the Dunning-Kruger effect, where they think they are above average and better than they actually are. This overconfidence is toxic for effective responses to teacher feedback. The general nature of 'whole class feedback' can make it particularly prone to this flaw in students' learning.

A bitter truth for teachers is that poor performers lack the self-awareness (metacognition) to judge their own performance accurately. As the saying goes, 'they don't know what they don't know'. Individual students can struggle to identify what whole class feedback applies to them and what doesn't.

What may be the problem with written feedback?Written feedback has its own issues that make it hard to make work for every student.

First, written feedback can be laborious and by the time the message reaches students, it could be day (even weeks) after the task itself. It is hard even for high prior attaining students to respond to, and integrate, written feedback so that it improves their future work.

Students may not understand the teachers' language, or have time and the independence to apply it to improve their work. International research has shown that too few students improve their writing despite being given feedback on revisions.

Popular approaches such as 'live marking' can model feedback in the moment - so students don't have to wait for days. And yet, the message we want to communicate during live marking' feedback may not hit home because students are already overloaded and their working memory cannot follow the example, understand the teacher feedback, and then apply it to their own work.

Whether it is verbal or written, weaker students are prone to seeing feedback as criticism, whereas stronger students are more likely to be proactive and help it drive their improvement. Weaker students can misjudge the fact they tried hard with the quality of what they have produced.

Should we not bother with feedback? But we should consider how the mitigate the possible issues that might arise if we don't support and target feedback to individuals.

How can feedback be improved?Feedback is not a clear, simple exchange. It is a difficult, contingent, emotional, belief-laden effort. Teachers pose messages that can be easily lost, or can hit home very directly.

What can teachers do to enhance the likelihood that the message we want to convey with feedback hits home? Here are some evidence-informed strategies:

Integrate peer feedback. When students provide comments to their peers, it can be more beneficial than receiving the message directly, as it is more cognitive engaging, where students need to grapple with the criteria and compose the message. In short, it forces active hard thinking and learning. It needs training and support to be impactful, but peer feedback added to the teacher feedback loop is likely to add a layer of valuable learning. Analysing multiple exemplars. Students can involve their egos too much when reflecting on their own work. Better than to create some distance and to get students think harder about their own learning by way of concrete examples and distinguishing examples to compare with. Instead of generic whole class verbal feedback, pick three anonymous examples and compare them. Attribute 'gold/silver/bronze', or 'improving/better/best' to distinguish the successful features. More comparisons, more precision, more active thinking and learning. Focus on next-step checks. Dylan Wiliam states that feedback should be more work for the recipient than the donor. In short, the teacher needs to ensure the student is thinking hard about their feedback and acting up it. If students are reading written feedback, or listening to whole class verbal feedback, they need to create a checklist of individual actions they will undertake as a result e.g. in history, feedback on class essays on the Normans may elicit a checklist of three or four next steps for improvement. If students share and explain their next-steps, then they are more actively processing the feedback.Feedback is too often just hard work for students no matter their starting points. But for those students who struggle, and have low self-confidence, it is particularly fraught.

We should consider whether our strategies and feedback habits are getting the message through. Are teacher efforts leading to hard thinking and reflection, improving students' judgements, and leading to concrete actions that improve their learning.

If teachers are pouring hours into writing feedback, they need to know it won’t drift aimlessly like a message in a bottle, but land exactly where and how they intend.

November 1, 2025

The 3Rs - Reading, writing, and research to be interested in #72

Dyslexia: Issues with definitions and diagnoses

Teaching a struggling reader, whether they are seven or seventeen, can be a gut-wrenching experience. It can make the typical tasks of a school day difficult and sap the enjoyment out of learning. It is no surprise then that every teacher, and parent, wants to get to the root of the problem for struggling readers.

Dyslexia is one of the most well-known special education needs. This is largely part to it being one of the most common issues for children’s learning and development, but also because it poses barriers to learning that are clear and obvious.

However, like many areas of special educational needs, dyslexia is prone to misconceptions and misreadings. Indeed, research from Durham University showed that even dyslexia professionals held problematic misconceptions about it.

It is no surprise then that defining dyslexia is a really important task if we are to better diagnose and address the widespread issue for struggling readers.

Changing definitionsThe nature of a definition can fundamentally change how we respond to a special educational need. Dyslexia has been prone to changing definitions, shifting symptoms and different diagnoses.

In a recent research paper, entitled ‘Thoughts on the Definition of Dyslexia’, international researchers have explored the issue. They show how a fundamental change to the definition may change how we see and address dyslexia.

The expansive International Dyslexia Association’s two decades old definition of dyslexia has changed, and it reveals a key shift. The old definition was described as follows:

“Dyslexia is a specific learning disability that is neurobiological in origin. It is characterized by difficulties with accurate and/or fluent word recognition and by poor spelling and decoding abilities. These difficulties typically result from a deficit in the phonological component of language that is often unexpected in relation to other cognitive abilities and the provision of effective classroom instruction. Secondary consequences may include problems in reading comprehension and reduced reading experience that can impede the growth of vocabulary and background knowledge.”

However, the new definition and be made more concise and targeted:

“Dyslexia is a specific learning disability in reading at the word level. It involves difficulty with accurate and/or fluent word recognition and/or decoding pseudowords.”

The researchers challenge ‘zombie’ definitions and try to focus on the essential nature of dyslexia. The shortened definition is obvious.

They challenge the ‘discrepancy’ definition – which poses that dyslexia reveals an odd discrepancy between reading ability and general cognitive abilities (such as IQ). They also argue that any ‘neurobiological basis’ adds nothing to the definition. They even exclude the commonly related spelling deficit that attends dyslexia profiles.

From definition to diagnosis“Definitions of dyslexia must address the science-based skills that will lead to competent word reading accuracy and fluency.”

Definitions of special educational needs, along with medical diagnosis, can prove contentious. There are often multiple definitions out there in the wider world.

Indeed, other recent definitions of dyslexia in the UK, such as the ‘Delphi Definition’ have been welcomed as an improvement on the long-standing Rose Review definition. The Delphi definition pairs reading and ‘spelling difficulties’ together once more.

What is crucial is that there is a consensus over a definition, as this can lead to greater understanding of causes and symptoms. Without clear evidence, teachers and parents can be left confused. An industry of quick-fixes and the selling of dubious resources can thrive in such circumstances where ambiguity reigns.

What is helpful about the new International Dyslexia Association definition is the targeted focus. Too often, over time, special educational needs definitions, and symptoms, grow and grow. As a result, many more young people are given a diagnosis, but the science has not kept up with a solution to such issues.

An industry of assessment has grown up around the dyslexia issue nationally. There is a danger that the mushrooming of ‘mild’ cases obscures the solutions for word reading (and spelling), and that more severe cases go unaddressed due to a lack of capacity in the system.

It is also important the dyslexia doesn’t become a byword for all reading issues. The clearer we are about defining it, and being precise about the causes and symptoms, the greater the likelihood of decisively addressing the problem for more children, earlier and more effectively.

In England, a significant SEND review is on the cards. Precise definitions, and a clear consensus, are needed for the most prominent special educational needs if it is to be successful. A universal definition and diagnosis for dyslexia could make a massive positive difference.

A focus on the definition and the diagnosis must then be translated to teachers, who are supported to decipher the specific barriers to learning they cause, along with the best available strategies to address them.

Related reading: Making the difference for pupils with dyslexia . This blog offers practical teaching strategies for busy teachers. The impact of the dyslexia label . Researcher, Catherine Knight, released a study showing how a dyslexia label can paradoxically lower expectations and self-belief. We need a new definition of dyslexia . Professor Julia Carroll (of 'Delphi Definition' fame) argues compellingly for a new, universal definition.

October 25, 2025

What do we mean by high expectations?

"They can because they think they can."

('Possunt quia posse videntur')

Virgil's 'Aeneid'

High expectations can be a mysterious thing. Something ineffable. You can understand them when you experience it. You may be able to tell a tale about when someone had high expectations for you, but it can often prove hard to put those expectations into words.

We have all experienced school and have our personal interpretations of high expectations that linger with us.

I went to a tough comprehensive boys school in Croxteth, Liverpool. Then, and for two decades since, it has been on the brink of failure (until a more recent takeover). I remember the fabric of the school was worn and tattered. The hopes of its male students for academic success weren't shining either.

In rooms full of Lynx-laden Liverpool teenagers, where ideas like wider reading or homework were anathema, it was easy to assume high expectations were in short supply. I certainly didn't feel it in all my classes all the time.

But in history teachers like Mr Delahunty or Mrs Keogh, or maths teachers like Mr Laing, high expectations still slipped through the cracks in the walls and made themselves known.

They made explicit expectations we should work hard and prove our worth compared to boys from the posher schools. There were expectations you would listen and learn. There was an expectation that effort was non-negotiable, even if you hadn't read the books, or knew the special words. I didn't fully understand it then, but there were expectations, teaching practices, and behaviour nudges that meant high expectations were evident. Crucially, for me, they made a difference.

Defining high expectationsThe hard thing about high expectations is that everyone thinks they have them. It becomes an act of stating the bleedin' obvious. And yet, when we try and define it, we may crystallise some useful reflections and refinements as to what we actually think and do.

In the new OFSTED Toolkit, high expectations runs throughout the document. It is clearly evident in their view of inclusion, where "setting high expectations is noted as a factor that contributes strongly to inclusion".

It is also a factor in having "high expectations for all pupils’ attendance, behaviour and attitudes, and design effective policies that communicate these high expectations clearly to staff, pupils, and parents."

In a recent speech, the Education Secretary, Bridget Phillopson, extended high expectations to parents too, "So high expectations of children must mean high expectations of parents too. To live up to our responsibilities. To play an active role in our children’s learning."

So, sky-high expectations - everyone should have 'em!

And yet, a dictionary definition of high expectations doesn't do much for us. It needs to be specific. For leaders, they need to establish and sustain high expectations with daily habits and practices. Each leader, teacher, and teaching assistant is likely to need to share the same understanding too.

If we don't break down high expectations into things we think and do (often as a relentless habit), then it becomes an empty platitude. Or worse, it morphs into an unrealistic or punitive 'no excuses' mantra that can squander necessary goodwill.

Mr Delahunty was relentlessly supportive of me so that I could learn history. That came with some pressure, and a great deal of demanding expectation, but it was rooted in care, understanding, and clear instructions about what I should do.

High expectations in every classroomI think high expectations will look different in nurseries, schools, and colleges. If we try and narrow it down to a simple formula for all, we may stop people thinking, instead of supporting them to reflect, refine, and act.

But if I was to visit one of these settings (which is one of my professional privileges), then I would consider some practices that bake-in high expectations into teaching and learning. My notion of high expectations in the classroom could include:

Setting challenging goals. Feedback and setting meaningful but challenging goals can be a tricky business. We can boost motivation or break the hopes of students. We make decisions about it all the time: some explicit and some tacit. For example: Do we enact clear feedback and goal setting - and how? Do we issue target grades or not? If we do issue target grades, how challenging are they? Do we encourage self-regulation goals and not just academic goals? Do goals fuel students' motivation or foster fear - and how would we know? Read my blog on 'Goal setting and building cathedrals' - with its breakdown of different goals - HERE. Read the EEF guidance on 'Teacher feedback to improve pupil learning' - HERE. Read this by Prof Becky Allen on setting target grades - HERE . Model excellent work. The nuts and bolts of high quality teaching include modelling. It is inclusive, responsive, adaptive - take you pick! But it is tricky to do well. We might consider live modelling of academic writing, or modelling of product design or brilliant self-portraits in art. We would make decisions about how to model excellence. For example: How should we best model? How many worked examples would be effective? What would excellence look like for this given task? If we are scaffolding the task, when do we remove the scaffold? How do TAs support independence with their support and prompts? Read my blog on 'Adaptive teaching: Scaffolds, scale, structure, and style', where I unpick how you can maintain high standards with meaningful adaptations - HERE . And see my free resource on 'Modelling writing approaches' HERE . Read Tom Sherrington's brilliantly clear and practical blog on 'Five ways to secure progress through modelling' - HERE . Read Mary Myatt's passionate call for 'Beautiful work' - HERE . Build accountable communication. Who is talking in class may be our first question. But who is listening and thinking hard may be the key question, if we are to have the highest of expectations of both communication and learning. Doug Lemov's notion of 'ratio' works well here. That is to say, who is thinking hard and participating? What is the ratio in our classroom at any given point? To establish high expectations we need to model listening, build brilliant book talk, expect routine discussion with well-practised strategies, and more. We then have questions about the quality of academic talk and accountable communication. For example: Should we have 'no-hands up' or 'Cold call' to assure students are accountable? Can we deploy talk routines (like 'ABC feedback') to foster listening and responsive communication? Do we expect academic language to be used routinely - if so - how do we scaffold it?Read my blog on 'Disciplinary talk' to understand how we may communicate differently across the curriculum - HERE . My 'Three pillars of vocabulary instruction' explores how we build academic language - HERE . Read Julian Grenier's EEF blog on 'Building learning in the early years: How conversations can change children's lives for the better' - HERE . Read this St Matthew's Research School blog on 'Accountable classroom talk' - HERE . Scaffold self-regulation and independence. High expectations could plausibly be characterised as students routinely managing a tricky task to the best of their ability with increasing independence. High expectations is expecting a young children in nursery to play with their peers; high expectations in secondary school is expecting a student to undertake their revision with effort and diligence; high expectations in college is to expect wider reading around the topic, or independence in seeking more knowledge or work experience. We are left with questions. For example: What learning behaviours do we scaffold and expect? How do we support independent tasks best, such as wider reading, homework, or exam revision? How do approaches to build self-regulation or independence change between Early Years and year 1, or between primary and secondary school? What strategies help children persevere through difficulties and struggle? Read my blog on 'Improving independent learning' - which unpacks 'learned helplessness' and 'learned industriousness' - HERE . Watch the EEF animated explainer on 'Metacognition - A brief explainer' - HERE . Read the AERO practice guide on 'Supporting self-regulated learning' - HERE .Of course, there are so many interpretations of high expectations. What I have characterised may not encompass what schools and settings do, think, or prioritise. But the thinking and reflection matters. We need to distil high expectations into something concrete, replicable, clear and sustainable.

High expectations is not some idealism that every child can achieve a 9 or an A*, but it should be something useful that believes and builds a culture that supports every child to be the best version of themselves. It is how Mr Delahunty approached teaching me history.

We should ask then: what do we mean by high expectations?

October 18, 2025

The 3Rs - Reading, writing, and research to be interested in #71

October 11, 2025

Scaffolding and PEAL paragraphs

"Scaffolds are not intended to be permanent. If everyone has a scaffold all of the time, it's not a scaffold, it's just your lesson plan."

'The Scaffolding Effect', by Rachel Ball and Alex Fairlamb

Teachers understand that scaffolds can be vital supports to tackle tricky tasks. For English teachers, as well as in subjects like history, business studies, and religious education, where extended analytical writing features – PEAL, and similar analysis structures – have been long-standing strategies to support students.

It is recommended on BBC Bitesize, as well as being promoted by some universities as a handy writing support.

But in recent years, there has been a backlash in some quarters against using scaffolds like PEAL too.

So, what should teachers do? Do paragraph plans, PEAL, and similar scaffolds have a place? Should we get rid and do things differently? Should we consider where they have a place, when to use them, and when to deliberately fade the use of these scaffold?

The limits of PEAL paragraph scaffoldsIn recent English subject reports, paragraph analysis scaffolds, like PEAL have been directly critiqued. For example, AQA wrote the following in their 2024 examination report for English Literature GCSE exam:

"There are still examples of extremely tightly structured essays following an acronym model as PEE, or PEEL, or PRETZEL or similar. While these structures may give support and direction to some, for others they can be limiting and constricting, and responses that rely upon them quickly become repetitive and constrained."AQA GCSE English Literature Examiner Report

This quote reveals a challenge with all scaffolding. Leave it there too long and it becomes a constraint. Rather than get students thinking and developing their ideas with increasing independence, acronym structures can become a constraint.

In English, you can see a student practise PEAL paragraphs throughout Key Stage Three as a way to develop their analytical writing. But by GCSE, citing evidence can become procedural, or making a 'link' doesn't prove a sophisticated enough instruction to attain higher level written responses.

Once students can cite concise evidence and explore language and meaning, the PEAL formula can become redundant. It becomes an extra thing to remember. Given it is unnecessary, it is ultimately a waster of precious mental effort. And yet, judging whether it is helpful or extra mental effort is a nuanced decision based on careful knowledge of individual students.

A key phrase which may be missed in the examination report is the phrases "may give support and direction for some".

PEAL type acronyms are legion across the curriculum for a reason. It could be DEED (Define - Explain - Example - Draw it Together) in business studies, or DEAL in geography (Describe - Explain - Apply - Link). They help scaffold writing structures - typically of paragraph length - that make writing a little bit more manageable.

We should consider the effectiveness of scaffolds particularly through the eyes of the students who struggle the most to access the curriculum.

For some students, composing accurate sentences that exhibit lots of knowledge of business or geographical features comes relatively easy. For many others, who have significant gaps in their knowledge and understanding, and find writing skills a challenge, the acronym is a handy planning shortcut to remember when writing under pressure.

In summary: for some students the scaffold can free them up to think and write more effectively; for others it becomes a limit and a constraint.

Of course, the devil is in knowing the difference and adapting teaching for students both individually and collectively.

Focus on fadingThe key with scaffolding students through the learning has parallels with real-world scaffolds. It should always be a temporary support and we should plan to remove it. So when, and for whom, should we writing acronyms like PEAL?

Scaffolding is a matter of effective teacher assessment. When students can make a point, cite a quotation, explain something about it, and make a meaningful link, then it is time to consider fading. So far, so obvious.

But can we be more precise? The following checklist could be a good way of deciding when to get rid of the PEAL-type writing scaffold:

Making a point:

Do their points make sense?

Can they write a clearpoint (or thesis statement) that steers their argument, not just restates the question?

Does the point show independent thought or a clear stance?

Using evidence:

Can they select apt, relevant evidence (quotation or paraphrase) that genuinely supports their point?

Do they integrate evidence/quotations smoothly into sentences rather than “dropping” them in?

Can they vary evidence types — textual details or contextual reference — when appropriate?

Increasing depth of analysis:

Does they explain how their evidence supports the point, showing understanding rather than just summarising?

Can they layer analysis e.g. exploring word choice, tone, structure, or wider ideas?

Do they move beyond one-sentence explanations to more developed reasoning, revealing understanding?

Making meaningful links:

Do they make a meaningful link that drives their argument forward, not just a summary?

Can they use links to compare, contrast, or synthesise ideas across a text or topic?

Do their links connect naturally to the overall argument or next paragraph?

Overall readiness to skip the scaffold:

Do they demonstrate the above knowledge and skill consistently across different topics or texts?

Do they show signs that the PEAL structure is starting to limit their fluency or originality?

Are they beginning to internalise the structure — using it intuitively rather than mechanically?

If the answer is yes to a lot of this questions, we need to begin to remove the scaffold. We could pare it back to 'Point > analysis'. That is to say, make a point, then use evidence/compare/contrast/explore layers of meaning, and more. In short, they don't need to worry about wedging an arbitrary link at the end of the paragraph if they are capable of developing their ideas independently.

We likely need to be explicit to students about decommissioning the structure. For example. 'James, I want you to move on from PEAL. We are going to make a clear point, still, but your analysis needs to address XXX and YYY.' We need to offer worked examples of strong analysis, do live modelling, and more.

In Business Studies, or history, the acronym may well be tied to GCSE examination criteria. It can be pragmatic to offer such reminders for writing in pressured exam conditions, when they have a wealth of knowledge to recall and analyse. But we should aim to introduce writing scaffolds like PEAL with the intent to remove the scaffold overtime.

For a small number of students, particularly those for whom a GCSE pass remains a stretch, PEAL can still serve as a valuable scaffold that supports working memory. It can and should be used independently as a practical aid for planning, but we must also ensure it doesn’t become the plan itself.

Let's keep the goal to see as many students as possible confidently guiding scaffolds and achieve genuine independent success.

Related reading: Scaffolding was likely first cited by Jerome Bruner, David Wood and Gail Ross in their study, ' The Role of Tutoring in Problem Solving '. Gary Aubin has written an excellent blog for the EEF on 'Scaffolding - More than just a worksheet'. READ IT HERE . My blog on 'Adaptive teaching: Scaffolds, scale, structure and style' explores scaffolding in relation to adaptive teaching more broadly. READ IT HERE .If you are interested in Adaptive Teaching - and strategies like scaffolding - I am undertaking my 'Adaptive Teaching Unleashed Teachology Masterclass' in Central London on the 21st November, which includes a bespoke short guide and resources). For those that attend the masterclass, I am putting on an exclusive BONUS twilight on 'Scaffolding to Secure Success' in November too. FIND OUT MORE HERE.

October 4, 2025

The 3Rs - Reading, writing, and research to be interested in #70

Alex Quigley's Blog

- Alex Quigley's profile

- 12 followers