Louis Arata's Blog

January 8, 2025

The Top Ten Books (I've Read) in 2024

My local library has shelves featuring recently published books as well as several tables where books are grouped by themes. About 20% of the books I read this year were discovered while perusing these stacks. It wasn’t like I was looking for a book on housecleaning or a novel about a piece of lung which becomes a monster. I didn’t have an eye out for a sci-fi retelling of the legend of Orpheus or a reimagining of Huckleberry Finn from the perspective of Jim. But I was delighted to find them all.

As in prior years, I did reread a number of books: Jane Eyre, Bleak House, The Hound of the Baskervilles, Little Women, Never Let Me Go, and Wide Sargasso Sea. Always, I get new insights when revisiting these amazing works.

And there’s an honorable mention which I never expected to wind up on the list, but I stand by my decision.

The Top Ten (alphabetized by author)

Jayne Eyre , Charlotte Bronté

It feels odd to put an established classic on my list of favorites, but the truth is that after rereading Jane Eyre, I came away with admiration for how radical a character Jane is. Hired as a governess for the ward of the moody Rochester, Jane must navigate the growing attraction between her and her employer. What makes Jane so radical is her absolute conviction to her moral principles. In an age where women were expected to prescribe to social norms, Bronte’s Jane speaks her mind. Any time she is faced with a moral challenge, she always determines what is best for herself rather than what society dictates – even if that means relinquishing her own happiness. But Jane’s moral fortitude gives her the ability to face every challenge head-on. A breathtaking novel.

A Dirty Guide to a Clean Home: Housekeeping Hacks You Can’t Live Without , Melissa Dilkes Pateras

Melissa Dilkes Pateras garners plenty of followers with her housecleaning wisdom via Tik-Tok videos. Now she has compiled her prescriptions for how to clean and organize your home. A witty writer, she has a knack for explaining why keeping on top of simple cleaning tasks can make your life less hectic. Often, I am bogged down by the endless chores of dishes and laundry so that deeper cleaning only occurs when I can’t stand the mess anymore. What Dilkes Pateras proposes is that by scheduling regular cleaning tasks, the little problems don’t become big problems. Since reading her book, I have kept a biweekly and monthly schedule for tackling chores that I typically would have put off. And truthfully, keeping on top of stuff has made my life easier.

James , Percival Everett

A brilliant reimagining of The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn from the perspective of Jim. In Everett’s novel, Jim is not only literate but well versed in philosophy. He teaches enslaved children how to read while also warning them to maintain the illusion that they are unschooled. Enslaved people know that if their intellect is discovered by their white enslavers, there will be hell to pay. While the early part of the novel follows the basic plot of Huckleberry Finn, once Jim is separated from Huck, he proceeds on his own adventures, such as performing in a minstrel show as a Black man pretending to be white pretending to be Black. He also helps free other enslaved people, and ultimately, he leads a mass exodus and a burgeoning rebellion. Satiric when it needs to be, and heartrending when it must, Percival Everett’s novel is a must-read.

Demon Copperhead , Barbara Kingsolver

I was eager to read Kingsolver’s reimagining of Dickens’ David Copperfield. Set in Appalachia, it follows the adventures of Demon as he is shuttled into foster care then finally finds a place as a high school football star. An injury sidelines his academic and athletic trajectory, but more so it is his addiction to opioids that undoes him. Whereas Dickens’ novel has its share of drama, there is always a fair amount of charm to the tale. Kingsolver opts for a gritty take on poverty, the foster care system, and especially the opioid crisis. Demon’s story goes from bad to worse, though it does land on a somewhat hopeful ending.

It Can’t Happen Here , Sinclair Lewis

Written in 1935, Lewis’s novel follows the rise of a fascist dictator on American soil. Duly elected, President Berzelius “Buzz” Windrip immediately initiates his plans to return the country to its patriotic values. If that means executing two-thirds of Congress, so be it. Soon, there are Minute Men, a paramilitary force akin to the Gestapo, rounding up any citizen deemed to be a threat to the nation. The tale centers on Doremus Jessup, a liberal newspaper editor who openly criticizes the presidential regime. He is thrown into a concentration camp with other dissenters. Eventually, he escapes to Canada, where he joins the resistance.

Given the divisiveness in our current society, I found it challenging to read this novel. While the author engages in some satire, the book is not comic and can be quite grueling. My biggest challenge was acclimating to Lewis’s writing style, which often required concentration to follow his syntax. In the end, it was worth it to read, and the story remains foremost in my mind.

The Most Fun We Ever Had , Claire Lombardo

A richly layered history of the Sorenson family: Marilyn and David and their four daughters. In her teens, Violet kept her pregnancy a secret, and she gave up her son to adoption. Sixteen years later, the teen shows up. His arrival triggers all manner of dysfunction between parents and children and between siblings. In particular, each daughter is facing some sort of identity trauma. What makes it harder for the daughters is that they live in the monumental shadow of their parents’ love. Via flashback, the author reveals that not everything was always rosy between Marilyn and David. I didn’t want this book to end.

Black No More , George S. Schuyler

Published in 1931, Schuyler’s novel speculates what would happen if the “race problem” was solved in the U.S. A scientist develops a process by which Black skin can be turned white. Wouldn’t that eliminate bigotry? Protagonist Max Disher, who undergoes the treatment, falls in love with the daughter of a White Supremacist whose organization, the Knights of Nordica, wants to end this race-reversal process. After all, if you can’t blame Blacks for all of society’s problems, how can you run an effective political campaign? Schuyler’s novel, thick with satire, addresses the dangerous absurdity of racism and even now spotlights how systemic racism remains woven into the fabric of society.

A Week on the Concord and Merrimack Rivers , Henry David Thoreau

Thoreau’s first published book, A Week on the Concord and Merrimack Rivers, is a precursor to his more famous work, Walden. Thoreau and his older brother, John, embark on a trek following the two rivers. Not really an adventure story; instead, Thoreau uses the journey to examine local wildlife and indigenous history, and sometimes he ruminates on religions. Everything is perceived through the philosophic lens of Transcendentalism. While lacking the thoughtful organization of Walden, this book shows the promise of a young writer wrestling with the Big Questions. I have read selections from A Week in a compendium of Thoreau’s writings, but sinking into the depth of this early work was an entirely different experience altogether. I will be revisiting this book in subsequent years.

Morgoth’s Ring , J.R.R. Tolkien

After completing The Lord of the Rings, Tolkien attempted to revise his earlier tales from The Silmarillion to bring them in line with Frodo’s history. Although he never completed these revisions, he did write several fascinating essays and stories exploring philosophic themes. The title, Morgoth’s Ring, does not refer to a physical object, such as Sauron’s One Ring, but rather the pervasive evil of Morgoth’s presence in the round, material world. Tolkien examines the nature of evil and how it must be combatted. Along the way, he delves into questions of mortality and immortality – Elves vs Men – and even wrangles with the Catholic notion that the marriage bond between one man and one woman is eternal. Morgoth’s Ring is the tenth book in the 12-volume The History of Middle-Earth, Christopher Tolkien’s compendium of his father’s work. I rank it as one of my favorites in the series.

When Brains Dream , Antonio Zadra & Robert Stickgold

How we dream is as fascinating as why we dream. According to the authors, the brain engages in a fair amount of problem-solving via dreams. So, why are dreams so absurd? It may be that literal thinking can’t make the necessary connections to resolve a problem, so the brain resorts to loose associations to provide insights. That’s why, after balancing your checkbook, you end up dreaming about your 2nd grade teacher who taught you to identify dimes, nickels, and quarters, and then you wake up determined to save every penny you can for retirement. Fascinating stuff.

Honorable Mention

Pollyanna , Eleanor H. Porter

Calling someone a “Pollyanna” suggests that they are excessively optimistic. And certainly, the main character in Porter’s novel has a favorable outlook on life. But to dismiss her as a naïve, chipper girl overlooks her sheer determination. An orphan, Pollyanna plays “the game” her father taught her: To find the best in any given situation. Now that she is living with her stern and aloof aunt, the girl must employ the game to face all sorts of challenges. While she does spread cheer throughout the town and changes many people’s lives, she is also wrestling with her own grief and limitations. There is depth to this child’s soul. The novel does take a surprisingly dark turn, but there remains hope at the very end.

The complete list of books is below:

Little Women, Louisa May Alcott

The Release, Elizabeth Jarrett Andrew

Clydeo, Jennifer Aniston

Slender Man, Anonymous

Planet of the Apes, Pierre Boulle

Jane Eyre, Charlotte Bronté

Still Life, A.S. Byatt

Sleeping Murder, Agatha Christie

The Hound of the Baskervilles, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle

Monstrilio, Gerardo Sámano Córdova

Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, Roald Dahl

The Last Thing He Told Me, Laura Dave

The Ghost and Mrs Muir, R.A. Dick

Bleak House, Charles Dickens

Some Short Christmas Stories, Charles Dickens

A Dirty Guide to a Clean Home, Melissa Dilkes Pateras

When Harry Met Sally…, Nora Ephron

James, Percival Everett

My Favorite Thing is Monsters, Vol. I, Emil Ferris

The Maltese Falcon, Dashiell Hammett

Horrorstör, Grady Hendrix

A Knickerbocker’s History of New York, Washington Irving

Never Let Me Go, Kazuo Ishiguro

Demon Copperhead, Barbara Kingsolver

We Are the Brennans, Tracey Lange

It Can’t Happen Here, Sinclair Lewis

A Hobbit, a Wardrobe, and a Great War, Joseph Loconte

The Most Fun We Ever Had, Claire Lombardo

Under the Tuscan Sun, Frances Mayes

Secrets of the Octopus, Sy Montgomery

Monster, Walter Dean Myers

The Railway Children, E. Nesbit

Hamnet, Maggie O’Farrell

The Lady from the Black Lagoon, Malory O’Meara

More Perfect, Temi Oh

Dream Work, Mary Oliver

Pay Dirt, Sara Paretsky

The Field Guide to the North American Teenager, Ben Philippe

Pollyanna, Eleanor H. Porter

Wide Sargasso Sea, Jean Rhys

The Lightning Thief, Rick Riordan

The Light We Lost, Jill Santopolo

Black No More, George S. Schuyler

The Two Gentlemen of Verona, William Shakespeare

Pygmalion, George Bernard Shaw

The Penguin Book of Murder Mysteries, Michael Sims, ed.

101 Great American Poems, The American Poetry and Literacy Project

A Week on the Concord and the Merrimack Rivers, Henry David Thoreau

Morgoth’s Ring, J.R.R. Tolkien

No Gods, No Monsters, Cadwell Turnbull

Thoreau: A Life, Laura Dassow Walls

When Brains Dream, Antonio Zadra & Robert Stickgold

October 23, 2024

Book Review: Horrorstör

The premise: ORSK, an IKEA-like furniture store, is haunted, and its employees face a night of paranormal horror.

Feeling stuck in her dead-end job, Amy hopes that a transfer to a new location will be the kick she needs to get out of the workaday rut. Standing in her way is Basil, a devoted ORSK manager who has sold himself body-and-soul to the corporate culture. They come to a begrudging agreement: If Amy is willing to help Basil find out who has been vandalizing the warehouse, he will approve her transfer.

That night, Amy and her sweetly pleasant co-worker Ruth Anne help Basic patrol the store. They come across bizarre graffiti and various noxious damages to furniture. Along the way, they discover two other employees, Tiffany and Matt, have snuck into the store to record paranormal phenomena.

At first, the only sign of bizarre activity is that Carl, a homeless man, has been living inside the store at night. When Tiffany insists on conducting a séance to contact the spirits, Carl is possessed by the spirit of Josiah Worth, the sadistic warden of a 19th Century asylum which had occupied the same location as the ORSK store. The warden has plans to rehabilitate Amy and her co-workers from their sinful ways.

And here is where author Grady Hendrix hits his stride: The rehabilitation exercises are analogous to the soul-sucking requirements of corporate culture. Amy, who has always longed for a simple desk job, finds herself literally bound to a chair by the plastic strips used to bind bundles of cardboard. The torturous pressure of the bands forces Amy to confront her own limitations: Her lack of drive, her willingness to quit when things get tough. Warden Worth assures her that if she would simply succumb to the treatment, she would be cured of her sinful nature and would become a useful cog in the machine.

Likewise, Amy’s co-workers face the existential tortures of mind-numbing, soul-deadening jobs: An endless treadmill; working their fingers to the bone.

Amy digs deep and discovers her courage, and she and Basil – no longer nemeses – find they have more in common. They set about attempting to rescue their colleagues from Warden Worth and his ghostly prisoners.

Hendrix fashions a recognizable environment. ORSK shares many qualities with IKEA, but it could also stand for any corporate grindstone. Employees are at risk of becoming like the ghostly inmates who haunt the premises:

My sole complaint is that the story progressed at an unvarying pace. Even as horror elements come into play, even as Amy throws herself into rescuing her colleagues, the pacing never accelerates toward the conclusion. It felt like the story was stuck in a 50-mph speed zone and never got into the passing lane.

Overall, Horrorstör is clever and fun, and Hendrix creates an effective and elaborate metaphor for the horror of soul-deadening corporate work culture.

September 12, 2024

Book Review: Bleak House

A contested will – or rather, multiple versions of a will – are at the center of Jarndyce and Jarndyce, an interminable court case which devours the lives of all legatees. Such is the backdrop for Charles Dickens’ Bleak House, a bleak and bitter indictment of the judicial system.

This is my third go-round for Bleak House. I confess that the first time I read it, I was befuddled by the method of storytelling, which alternated between Esther Summerson’s first-person narration and an omniscient third-person narrator. Plus, there is a humongous cast of characters (which is standard in any Dickens’ novel). My second time through was benefited from watching BBC’s 2005 production, which does an exceptional job of weaving together multiple storylines.

Bleak House follows the fortunes of Esther, whose parentage is a mystery. Her benefactor is John Jarndyce, a benevolent soul who resides at Bleak House. Jarndyce, who is one of the legatees of the court case, agrees to raise the two wards in Jarndyce, Ada Clare and Richard Carstone.

On the other end of the tale is Lady Dedlock, a cold, aloof aristocrat who hides a dreadful secret. She too is caught up in the court case. Once she comes under the suspicion of Edward Tulkinghorn, her husband’s villainous solicitor, she fears that her past will be exposed.

While Dickens’ novel is famous for its indictment of the judicial system, and it instigated some measure of judicial reform, what caught my attention this time is the examination of family relationships. A last will and testament is supposed to clearly state who receives what as a bequest. But this also applies to parent-child relationships.

Early in the novel, Esther encounters Mrs Jellyby, a far-sighted philanthropist who is more concerned about the welfare of a distant African tribe (fictional) than her own family. Her husband is so beaten down by life that he has to be propped against the wall. Her daughter Caddy is her unwilling amanuensis, and there are abundant younger Jellybys who are forced to scrounge for food because neither parent is capable of caring for them.

Likewise, there is Harold Skimpole, a congenial parasite whose defense is that he is too much of a child to actually be held responsible for anything: He does not work, he runs up debts, and he pleads ignorance when it comes to any financial matters. But he is perfectly willing to sponge off others. Skimpole does have a wife and daughters, but he seems perplexed when it is suggested that he should support them.

In contrast, there is the beneficent John Jarndyce, a parental figure for Ada and Richard. As Richard becomes increasingly obsessed with the outcome of the court case, he begins to view John as an interloper and an opponent, no matter how much John assures him otherwise. It becomes a symbolic battle between a worldly-wise father and a stubborn, willful son.

Throughout the novel, there are parentless children, like Jo the crossing-sweeper and Charlie Neckett, and childless parents, like the poverty-stricken Jenny, whose infant dies from want. There are mother-son relationships, such as Mr Guppy and his giggling mother, and the estranged mother and son, Mrs Rouncewell and Mr George. There are kind families, like the Bagnets, and there are villainous families, like the Smallweeds. There are constructed families, like Mr George and Phil Squod, and newly formed families, like Caddy Jellyby and her husband, Prince Turveydrop.

And ultimately, there is the discovered parentage of Esther Summerson, which pulls all the story threads together.

Of all of Dickens’ novels, David Copperfield remains my favorite, but Bleak House, with its interwoven storylines ranging from highest society to lowest poverty always impresses me. If you are new to Dickens, I encourage you to watch the BBC miniseries first; it was measurably helpful in parsing out the critical details of the plot. After that, indulge in the novel, for it is brilliant.

January 23, 2024

The Top Ten Books (I've Read) of 2023

We’re well into 2024, and only now am I getting around to posting my favorite books of 2023. It seems rather fitting that I’m behind schedule, given that everything about my 2023 reading season was on a slow track.

I spent my time revisiting some favorite plays (1776, Twelve Angry Men) and discovering new ones (Slave Play, All My Sons). I delved into classic and contemporary horror (The Haunting of Hill House, Dracula, Frankenstein, and Don’t Fear the Reaper). I dabbled in poetry (Dylan Thomas), UFO’s, and Charles Schulz’s Peanuts.

One monumental book (The Bible) occupied 9 months of my time. While I read other books along with it, the majority of my attention was focused on the good book.

Along with my Top Ten and Honorable Mentions, I’ve included two new categories: Most Significant and Guilty Pleasure.

In alphabetical order by author, here are my top ten books:

The Top Ten:

Rashōmon and Seventeen Other Stories, Ryunsoke Akutagawa

I love novels because there is elbow room to explore mighty themes. That is, until I come across a writer who excels at short stories. This collection of Ryunsoke Akutagawa’s work ranges from historic, tragic, comic, and a bit of memoir. His two most famous stories, “Rashōmon” and “In A Bamboo Grove” are the basis of Akira Kurosawa’s film Rashōmon. The final section of the book includes personal essays which share some of Akutagawa’s own story; these are all the more poignant, given that the author committed suicide at 35.

No Crying in Baseball, Erin Carlson

I enjoy a good behind-the-scenes look at movies. Erin Carlson’s book follows the making of A League of Their Own, the story of the All-American Girls Professional Baseball League. Not surprisingly, there are backstage dramas (i.e., Madonna didn’t always play well with others, and Tom Hanks was looking to recover from several movie flops). What makes this book better than most is that Carlson explores the significance of Penny Marshall’s career – such as, Marshall’s Big was the first film directed by a woman to gross over $100 million. Marshall, who is primarily known for Laverne and Shirley, proves to be somewhat eccentric and risk-taking as a director, but Carlson points out that male directors are often eccentric, and no one makes note of it. This book deepens my appreciation for one of my favorite films.

All The Light We Cannot See, Anthony Doerr

I wasn’t two pages into Doerr’s novel before I was in awe of his writing (and a wee bit envious). Beautifully crafted sentences, an engaging storyline. I was swept right along. The novel follows the parallel stories of Marie-Laure, a blind girl seeking refuge from WWII, and Werner, a bright German boy who is conscripted into the Nazi army. Their stories eventually converge, at least in a tangential sense; Doerr wanted to write about the “abundance of miracles” which may appear in the middle of a war. This may be one of the best novels I have ever read.

On a side note, my mother-in-law often recommended books to me. A Man Called Ove and A Gentleman in Moscow were the first two. She got comically impatient that I hadn’t yet read All the Light We Cannot See. At the start of every phone call and holiday visit, she asked me, “Have you read it yet?” I regret that I waited too long. She passed away in 2022, and now I won’t have the opportunity to discuss it with her. Gail, thanks for the recommendations. That’s three books now that will always remind me of you.

Don’t Fear the Reaper, Stephen Graham Jones

This novel follows Jade Daniel’s return to her hometown of Proofrock, ID, after the disastrous and horrifying events of My Heart is a Chainsaw. Stephen Graham Jones is composing a love letter to 1970-90’s horror films. He throws everything into the mix: slasher, ghost story, revenge tale. While the first book in the series is thrilling, Reaper hits the ground running and never lets up.

Slave Play, Jeremy O. Harris

Theatre can challenge the status quo like nothing else, and Harris’s play is a bold examination of the perpetuating legacy of slavery and racism. Three couples undergo Antebellum Sexual Performance therapy, in which they role-play different scenarios between slave owners and enslaved people. At times, the play is satiric; throughout, it is gut-wrenching. Given how deeply affected I was by reading the play, I can only imagine how powerful it would be to see a live performance. One of the best plays I have ever read.

Right by My Side, David Haynes

My library has a bookcase dedicated to classics: Pride and Prejudice, David Copperfield, The Poems of Emily Dickinson. Mixed in with these recognizable titles are lesser-known works which need to be discovered (or rediscovered), such as Haynes’ novel. Young Marshall Field Finney is disgusted by his parents’ perpetual drama. After his mother unexpectedly walks out, Marshall watches his heavy-drinking father soothe himself with affair after affair. Plus, Marshall’s best friend is too busy with his new girlfriend, while his other friend is caught up in a political protest. Nothing makes sense – especially when his mother starts writing him letters to explain why she left. Haynes delves deep into Marshall’s life and doesn’t shy away from examining the often conflicting and confusing emotions of growing up. When I finished reading the novel, I wanted to read it again right away.

Fairy Tale, Stephen King

King knows how to craft heroes and villains. But something has been happening in his more recent novels. There is a kindness and vulnerability to his main characters, which makes them all the more heroic. In Fairy Tale, Charlie Reade (17 years old) comes to the aid of his elderly neighbor, who has been injured. Mr Bowditch is a crotchety recluse with a sweet, aging German Shepherd, Radar. Soon, Charlie learns that Mr Bowditch guards a portal in his backyard which leads to Empis, another world. Bad things are happening there, and Charlie (and Radar) get pulled into a war to rescue the kingdom from Flight Killer and Gogmagog. Stephen King, of course, is adept at crafting magical realms, but what is more magical is his Charlie Reade. It takes a special talent to create a believable character who is courageous in their humanity.

Lady Chatterley’s Lover, D.H. Lawrence

I admit I’m surprised that this made my Top Ten. I knew a little about it, mostly that it was the subject of an obscenity trial when it was first published. I assumed it was a literary bodice-ripper: Lady Constance Chatterley experiences a sexual awakening at the hands of her husband’s gamekeeper, Oliver Mellors. Instead, what I discover is that smart, confident Constance is already sexually liberated. Her relationship with Oliver is both passionate and romantic. Together, they share concerns about class and social issues. As expected, their affair results in tribulations, but there is an element of hope at the end. Overall, an unexpectedly entertaining book.

Atonement, Ian McEwan

McEwan’s novel of a careless mistake is fascinating and heartbreaking. Thirteen-year-old Briony believes that her sister Cecilia is being stalked by Robbie, the housekeeper’s son. What she fails to comprehend is that Cecilia and Robbie are attracted to one another. Briony makes a disastrous accusation against Robbie, and he is arrested for rape. What follows is an examination of how this mistake has far-reaching consequences on all their lives. McEwan’s writing excels at blending his characters’ internal experience with the external world. My only complaint is that a fair portion of the novel centers on Robbie’s experiences in WWII, while Cecilia’s perspective is dropped. I wanted to know more about her life in the aftermath of the incident. The ending, however, is both clever and poignant.

Cabin Fever, Tom Montgomery Fate

Thoreau’s Walden is one of my favorite books, so when I learned that Cabin Fever is modeled after Thoreau, I had to read it. Montgomery Fate writes of lessons learned while living in a rustic cabin in Michigan. Here are thoughtful examinations of suburbia vs the woods. Solitude vs family. In essence, how nature blends with the modern world. Montgomery Fate’s writing is insightful, tender, and funny. I will come back to this book again and again.

The Most Significant Book I’ve Read:

The Bible, Douay-Rheims edition

To be honest, I couldn't bring myself to include this book in the Top Ten, as it deserves a category all its own. Given its historical and religious significance -- not to mention its scope -- it’s impossible to read The Bible like any other book. If you want to read more about my impressions of the Douay-Rheims edition, you can find it here.

Guilty Pleasure:

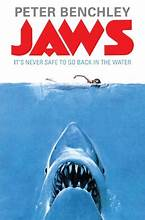

Jaws, Peter Benchley

This novel will always be overshadowed by Spielberg’s movie (and with good reason). The movie is a thrilling adventure story with distinctive characters. In the novel, Benchley seems to want the shark to win. Sheriff Brody feels like an outsider in the small town of Amity, whereas his wife, Ellen, mourns the loss of her youth and affluent status. As a result, she ends up initiating an affair with ichthyologist Matt Hooper. Meanwhile, the mayor Larry Vaughn is pressuring the sheriff to keep the beaches open; this isn’t merely to rescue the summer tourism trade but to appease the Mafia, who own most of the real estate in town. What intrigues me about the novel is that the shark represents an undercurrent of menace in a seemingly peaceful resort town. There are secrets everywhere, and they can rise up at any time and tear you to pieces.

Honorable Mentions:

Call Me by Your Name, André Aciman

A sweetly tender coming-of-age story which tells of the romance between Elio (17 years old) and Oliver, a 24-year-old graduate student. The novel explores the attraction, flirtation, ambivalence, and deeper contemplations as Elio discovers what it means to love. The relationship may be fleeting, but it continues to touch each of their lives. Beautiful writing and nuanced insight into the characters make this a special book. As of yet, I have not watched the movie (though I hear it is wonderful) because I don’t want to disrupt the novel’s gentle exploration of youth.

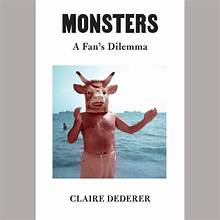

Monsters: A Fan’s Dilemma, Claire Dederer

What do you do when an artist you like happens to be a horrible person? Claire Dederer examines the careers of Roman Polanski, Pablo Picasso, Woody Allen, and others who produce respected works yet also have committed crimes and other moral outrages. What is a fan to do? Do we look at the art and not the artist, or are the two irrevocably intertwined? Overall, a compelling analysis, though the ending left me a bit disappointed.

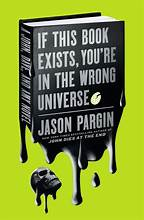

If This Book Exists, You’re in the Wrong Universe, Jason Pargin

The fourth book in the John Dies at the End series (JDate). The first novel will always be my favorite, but I remain impressed by the peculiarly funny and at times horrifying stories that Jason Pargin conjures. This time, Dave, John, and Amy are tracking down a possessed child’s toy which is involved in ritual sacrifices, alternate universes, and the potential apocalypse. As with the others in the series, a very entertaining book.

The complete list of books is below:

Call Me by Your Name, André Aciman

Rashōmon and Seventeen Other Stories, Ryūnsoke Akutagawa

Jaws, Peter Benchley

The Damned, Algernon Blackwood

The Peanuts Papers, ed. Andrew Blauner

Bloodchild and Other Stories, Octavia E. Butler

The Virgin in the Garden, A.S. Byatt

Free Days with George, Colin Campbell

No Crying in Baseball, Erin Carlson

The Mousetrap and Other Plays, Agatha Christie

How to Train Your Dragon, Cressida Cowell

I Heard the Owl Call My Name, Margaret Craven

Death in a Tenured Position, Amanda Cross

Monsters: A Fan’s Dilemma, Claire Dederer

All The Light We Cannot See, Anthony Doerr

The Bible, Douay-Rheims edition

Flying Saucers: Serious Business, Frank Edwards

Strangest of All, Frank Edwards

Middlemarch, George Eliot

Scenes of Clerical Life, George Eliot

Werewolves, Nancy Garden

Don’t Fear the Reaper, Stephen Graham Jones

Right by My Side, David Haynes

Growth of the Soil, Knut Hamsen

Slave Play, Jeremy O. Harris

MASH, Richard Hooker

Avenue of Mysteries, John Irving

Tales of the Alhambra, Washington Irving

The Haunting of Hill House, Shirley Jackson

Fairy Tale, Stephen King

Lady Chatterley’s Lover, D.H. Lawrence

Hell House, Richard Matheson

Atonement, Ian McEwan

The Sorceress and the Cygnet, Patricia A. McKillip

All My Sons, Arthur Miller

Cabin Fever, Tom Montgomery Fate

Baseball for Dummies, Joe Morgan

Ursula K. LeGuin: Conversations on Writing, David Naimon

If This Book Exists, You’re in the Wrong Universe, Jason Pargin

Bridge to Terabithia, Katherine Paterson

Kolchak: The Night Stalker, Kendall R. Phillips

The Death of Innocents, Sister Helen Prejean

Twelve Angry Men, Reginald Rose

Frankenstein, Mary Shelley

Dracula, Bram Stoker

1776, Peter Stone and Sherman Edwards

Weep Not, Child, Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o

Collected Poems, Dylan Thomas

How to Watch a Movie, David Thomson

Sauron Defeated, J.R.R. Tolkien

On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous, Ocean Vuong

December 4, 2023

Book Review: On Not Finishing "Gone with the Wind"

I couldn’t do it. I tried, but I could not make it through Gone with the Wind.

Before I began reading it (actually, rereading it after 30 years), I prepared myself for the romanticization of the Confederacy. Further, I braced myself for the racist depictions of enslaved people. Even so, I was taken aback.

My intention was to read it as a way to examine the shifting depictions of our country’s history. After all, here is a story which glorifies the Old South as though slavery is not a racist and cruel practice. Essentially, I wanted to understand why the book remains popular.

To be honest, right from the start, I had a hard time. I could barely handle Pat Conroy’s introduction, in which he noted how important Margaret Mitchell’s novel was to his mother and how she read it year after year. He described how the novel preserves the grandeur of the Old South and in particular the passing of a way of life. He glossed over any recognizable critique anyone might have with it.

I made it through the first quarter of the novel before deciding it wasn’t worth it. Gone with the Wind may remain a significant novel; it may be regarded as “literature,” yet what it does is whitewash our past.

Take the depiction of every single Black character in the novel. Mitchell resorts to stereotypes and dialect to underscore that they are less educated, less refined, simpler, naïve, and uncultured. “Slave” is just another word for “servant,” as though these characters chose this life. They are invested in preserving the dignity of their captors’ families and the prosperity of the plantations. Never is it suggested that they might desire their own freedom. Even Mammy, who has a keen eye and a degree of respectability, is caricatured as a bit of a buffoon.

The Old South is the closest thing to an aristocracy in the U.S., so it makes me wonder if Margaret Mitchell was modeling her style on that of Victorian-era novels, with their clear hierarchy of class. It suggests that the higher you are on the social ladder, the more respectable you are.

Curiously enough, two characters in Gone with the Wind question the South’s decision to engage in war. Ashley Wilkes, whom Scarlett O’Hara pines for, recognizes that it is a pointless battle. He will fight for the lost cause because he is brave and noble. And yet, he is smart enough to recognize that their aristocratic way of life is falling away. It must, given that society’s means of economy are continuing to shift.

Rhett Butler, that cynical scoundrel, also sees the writing on the wall, but he is too busy being a war profiteer to care.

At first, I thought Mitchell might use these characters to critique the complexity of the Old South. It became clear, however, that while Rhett and Ashley recognize the Old South's failing, they remain loyal to preserving it.

I grew up in Virginia, where Civil War memorials are ubiquitous. Memorials to the Confederacy were everywhere. Kids in my elementary school threw around the term Yankee as a comic insult. They also practiced the Rebel Yell. In fact, an amusement park in Virginia had a new rollercoaster (circa 1970s) called the Rebel Yell. It wasn’t until I was older that I caught on to what the term referred to.

Even as a kid living inside this milieu, I wasn’t the most knowledgeable kid about history, so I remember being confused about Robert E. Lee and Jefferson Davis. They were still lauded as noble Southerners. There were statues to them all over the place. Yet, hadn’t they tried to secede from the Union? Hadn’t they endeavored to preserve slavery as an institution? Wasn’t that wrong?

I recognize that readers who are loyal to Margaret Mitchell’s novel claim that it preserves their cultural heritage. But I wonder if the book simply perpetuates a blind spot about the Confederacy. By elevating the Old South’s culture, it ignores the fact that it was riddled with cruelty, rape, and murder.

In the end, I couldn’t stomach Gone with the Wind. I couldn’t read it as a simple story because in essence it distorts the reality of the Civil War.

While it’s hard for me to not finish a book, eventually I got what I expected from Gone with the Wind: An awareness that depictions of U.S. culture through literature and art continue to change. I can’t imagine a story like this being published in the mainstream now.

Should Margaret Mitchell’s novel be censored? I don’t think so. But if it is read, it should be open to critique and examination. Otherwise, it remains a story of a fabled past which perpetuates a cultural lie. At least for me, it got me thinking about how U.S. culture changes. And how it lies to itself to preserve a false notion of its own history.

October 22, 2023

Book Review: The Damned

Continuing the Halloween theme …

Tales about haunted houses generally aren’t my favorite. Often, the images, themes, and scary bits are derivative of other stories. It takes a deft hand to infuse the right amount of creepiness into the familiar trope.

Two favorites are Shirley Jackson’s The Haunting (with its house that is born evil) and Mark Z. Danielewski’s House of Leaves (while technically not a haunted house story, it is creepy that the house is larger on the inside than outside).

Another personal favorite is Algernon Blackwood’s The Damned (1914). Not much happens in terms of plot, but what makes the story special is the unsettling atmosphere of dread.

Siblings William and Frances visit their friend Mabel, a widow, at her mansion. The Towers, by all accounts, should be a peaceful place. It boasts large, comfortable rooms and a beautiful landscape. Yet something weird permeates the place. Neither William nor Frances feels at ease, and Mabel herself has become rather lifeless. None of them can put their finger on what makes the place so unsettling.

The haunting is distinctive in that it affects William, Frances, and Mabel differently. Mabel appears to be losing any vestige of personality, fading into a shadowy nonentity. Frances, meanwhile, finds that her paintings of the grounds are also capturing the inherent grotesqueness of the place. And William senses that gateways might open onto alternate landscapes.

Mabel’s deceased husband, Samuel, had been a fire-and-brimstone preacher who professed salvation, but only for those who shared his narrow views of right and wrong. Over the years, he had conducted many religious services on the grounds. Now William begins to suspect that the Towers are infected by Samuel’s fanatical religiosity.

William discerns that there are layers and layers of damned souls vying to escape their tortured existence. They are all pressing on the veil separating the spiritual realm from the real world – like too many people trying to fit through a narrow doorway. As a result, the Towers is becoming uninhabitable; no one feels safe there because the damned are all straining to capture your attention:

“House and grounds were not haunted merely; they were the arena of past thinking and feeling, perhaps of terrible, impure beliefs, each striving to suppress the others, yet no one of them achieving supremacy because no one of them was strong enough, no one of them was true. Each, moreover, tried to win me [William] over, though only one was able to reach my mind at all. For some obscure reason – possibly because my temperament had a natural bias towards the grotesque – it was the goblin layer. With me, it was the line of least resistance.”

Both William and Frances express a desire for the terror to finally erupt, if only for the relief. While William struggles to comprehend the nature of the haunting, it is Frances who articulates the complexity of it:

“’What is the world … but thinking and feeling? An individual’s world is entirely what that individual thinks and believes – interpretation. There is no other. And unless he really thinks and really believes, he has no permanent world at all…. Only the strong make their own things; the lesser fry.’”

Blackwood's crisp, efficient prose conveys the awful anticipation, the endless waiting. Ultimately, The Damned is a story about atmosphere rather than events. Blackwood acknowledges that there isn’t much story here: “It remains, therefore, not a story but a history. Nothing happened.” What might happen is where the horror comes in.

As H.P. Lovecraft writes of Blackwood’s stories: “Some of these accounts are hardly stories at all, but rather studies in elusive impressions and half-remembered dreams. Plot is everywhere negligible, and atmosphere remains untrammelled.”

The Damned may be pale by today's standards of horror, but it excels at how ghostly presences vie for dominance.

October 9, 2023

Book Review: Dracula

There are plenty of entertaining film versions of Dracula but none really captures the style of the novel. Plus, most movies take exceptional liberties with the story.

Bram Stoker’s novel begins with Jonathan Harker arriving at Castle Dracula, in Transylvania. He is there to deliver real estate papers for the count to sign prior to his moving to England. Plenty of peculiar happenings warn Harker that Dracula is a vampire, but before he can do anything, he finds himself prisoner, and the count on his way to his new home.

After a dramatic arrival via shipwreck, Dracula takes up residence in Whitby. It isn’t long before he is stalking Lucy Westenra, slowly draining her of blood and life. Lucy comes under the care of Dr Seward, whose sanitarium is adjacent to the count’s new home in Carfax Abbey.

When Seward is unable to identify the cause of Lucy’s illness, he enlists the help of his mentor, Abraham van Helsing. As they begin to suspect that this is the work of a vampire, the men scramble to protect Lucy, but Dracula proves wily enough to outwit them. Soon poor Lucy dies, but not entirely, for now she returns as a vampire. Van Helsing and Seward enlist the help of Arthur Holmwood (Lucy’s fiancée) and Quincey Morris to release Lucy from her undeath.

Now the count sets his sights on Mina Harker. It is up to van Helsing, Seward, Jonathan, Arthur, and Quincey to keep Mina alive. Armed with occult weapons, they begin tracking down Dracula’s lairs scattered around Whitby and London. By this point, Dracula has infected Mina with his tainted blood, which causes her to slip into quasi-vampirism.

Realizing he is in danger, Dracula flees back to Transylvania. Van Helsing, Mina, and their crew track him all the way to Castle Dracula, and there they dispatch the vampire with a swift beheading and a knife through the heart then stand back to watch as he crumbles to dust.

While most movies follow this general plot, what makes Stoker’s novel distinctive is that it is in epistolary style. There is no omniscient authorial voice, but rather the reader is presented with a series of journal entries, letters, and recordings made by Dr Seward, Mina, Jonathan, and Lucy, with a few passages by van Helsing himself.

The use of letters and journals as a narrative device grounds the story in the contemporary world of the 1890’s. These are characters who live by train timetables, current medical practices, and other features of modern society. In effect, the journals emphasize that these people live in a recognizable world which is being infiltrated by a monster from folklore. No one wants to believe there really is a vampire, even though all the evidence points to it.

One curious aspect of the story is Mina’s encroaching vampirism. When van Helsing attempts to protect her by placing a communion host against her brow, it burns her skin and leaves a scar. The mark symbolizes the psychic connection she has with Dracula. Every dawn and dusk, she slips into a hypnotic state which grants her some awareness of what the old vampire is up to. This piece feels like it foreshadows J.K. Rowling’s Harry Potter series, in which Harry’s lightning bolt scar represents his psychic connection to Voldemort. It makes me wonder if Rowling was inspired by Stoker in this regard.

One downside to Stoker’s novel is the gender stereotypes. Both Lucy and Mina are sweet, innocent angels (though Mina exhibits a quick mind). All the men worship them and wish to protect them, often by keeping them in the dark about what is going on. It becomes frustrating that the women are portrayed as helpless and in need of saving. Mina, at least, finally exerts her authority when she realizes she can see into Dracula’s thoughts; she ends up insisting on being part of the final chase to capture and kill the vampire.

I first read Dracula when I was 17 and a second time in my late twenties. At the time, I was not accustomed to reading epistolary novels, so while the story was engaging, I did find the style a bit of a slog.

This time, however, I thoroughly enjoyed how Stoker structured the story. It falls into a five-act structure:

1) Jonathan Harker’s arrival at Castle Dracula

2) Dracula’s arrival in England, and his stalking Lucy Westenra

3) Van Helsing’s efforts to save Lucy’s immortal soul

4) Dracula’s stalking Mina Harker

5) The search for Dracula’s lairs and the final chase into Transylvania

Once I recognized this structure, I found the segments exciting, as they were always driving toward the next climax. The only part which still seems slow to me is the preparation for the final act, as van Helsing and his crew are preparing to track Dracula to Transylvania. But the final chapter, with its race against the sunset, is quite thrilling.

I love revisiting novels and discovering that I engage with them quite differently now. In about ten years, I will be ready for another visit with Dracula.

September 4, 2023

Book Review: The Douay-Rheims edition of the Bible

If this were like any other book review, I would say that The Bible is a good book. The good book, as it were.

But to review The Bible like any other book is impossible. Its historical and religious significance – not to mention the breadth of its scope – prevents any sort of objective take on the work. Do I review the Old Testament or the New Testament? Do I compare “The Book of Job” to “The Gospel According to John”? How do I address the issue that some Christians consider the Bible to be the divine Word of God? What about all the individual authors of the books? Even if each of them was guided by God, the entire work is still a compendium of documents written across a great many generations. Christian editors selected which texts to include and which to leave out. And in the case of the Douay-Rheims edition, it includes books that are apocryphal to the King James version.

What I want to focus on is my response to the version which I read: the Douay-Rheims edition. It was chance that led me to select it. I simply downloaded from my library the first e-book version which was listed in the catalog.

The Douay-Rheims edition is an English language translation of the Latin Vulgate Bible (which itself is a Latin translation of texts written in Aramaic, Hebrew, and Greek). It was published in three volumes: the New Testament (1582) and the Old Testament (1609 and 1610). Notably, there were further revisions to the translation when Bishop Richard Challoner brought some of the language more in line with the King James version.

Specifically, the Douay-Rheims version is the Catholic Church’s response to the Protestant Reformation. Some of the books have different names than those in the King James version. For example, first and second Chronicles is called Paralipomenon, and 2 Esdras is known as the Book of Nehemias. Also, there are a few books, such as 1 and 2 Maccabees, which are not included in other translations of the Bible.

The Douay-Rheims version retains the archaic Latinate style and as a result is a bit heavy to muddle through at times. It makes me curious to read other translations and editions to see variable readings and more contemporary vocabulary.

I was raised Catholic, though I don’t recall which version of the Bible we used. Readings were only identified by chapter and verse, and I don’t recall that any readings ever came from the apocryphal books like Maccabees. What I do recall is that during Holy Week services, the congregation would read aloud the parts of the Passion in which the crowd shouted to crucify Jesus. I suppose this was to remind us that in our sinful nature we were still responsible for Jesus’s death.

In college, I took a class, “the Bible as Literature.” We read the books from a literary perspective. We examined the use of metaphors in “Job” and the poetry of “the Song of Solomon.” We also compared how the four gospels presented different takes on Jesus’s parables. While it felt rebellious (even somewhat sacrilegious) to treat the Bible like any other piece of literature, I was impressed that the professor (who I believe was a Christian Scientist) remained respectful of the text without promoting Christianity or even a belief in God.

This time when I read it, I found I didn’t have to read it as a divinely inspired work, nor from a Catholic didactic perspective. Instead, I read it as a history of a people’s relationship with their god. How the relationship was formed, how it changed over the generations. How people fell away then came back to the faith. How God could be righteous and forgiving. If I were to sum up the Old Testament, it might be with this passage from 2 Maccabees: “And therefore he never withdraweth his mercy from us: but though he chastise his people with adversity he forsaketh them not.”

Paradoxically, by reading it as a history, I was able to engage with stories in a more empathic manner. The stories teach that life is unpredictable but that there are principles to guide us along the way. Most important, it promotes that acts of goodness and mercy are the most important things in life. And these values are not rooted solely in Christianity but also in Judaism, Islam, Buddhism, Taoism, and any other manner of living which focuses on being kind to one another.

The most curious aspect of the Douay-Rheims version is that the editors interject commentary throughout the texts. They readily interpret passages from a distinctly Catholic perspective. For example, they emphasize that salvation must be earned by obedience to God. This is in opposition to Martin Luther’s view that God’s grace is a gift for all, regardless of our good deeds. At one point, the editors state: “For since none but the true religion can be from God, all other religions must be the father of lies, and therefore highly displeasing to the God of truth.” In other words, the editors are stating that Catholic church is the only true faith.

Sometimes, the editorial comments warn us not to read too freely into the texts. As such, in 1 Samuel, there is a note that while David was called upon by God to do good works, not all of David’s actions were sanctioned by God:

“Though it is to be observed here, that we are not under an obligation of justifying everything that [David] did: for the scripture, in relating what was done, does not say that it was well done. And even such as are true servants of God, are not to be imitated in all they do.”

Since college, I have read the Bible three times now, and each time I have wrestled and wrangled with it. It has been difficult for me to engage with a book which sometimes has been used to promote prejudice and oppression. Yet surprisingly, I can say that this time I enjoyed reading it as a history. I will leave the discussion of its being divinely written to others to ponder.

April 11, 2023

Book Review: Middlemarch

It’s difficult to overstate how important George Eliot’s novels were to me in my twenties. I had recently graduated college and had undertaken a reading program to tackle some of the classics of 19th century literature: Austen, the Bronte sisters, Dickens, Trollope, Melville, Tolstoy.

Austen’s humorous skewering of propriety was delightful, and Dicken’s comical and scathing attacks on social ills was always compelling, but there was something different about George Eliot’s work. Her characters faced the struggles of life and love, but they were always rooted in the machinations of a 19th century social system.

Over the last few years, I’ve been revisiting Eliot’s novels, only to find that I am having a vastly different reaction to them this time around. Some of them are a bit ponderous and too educative. I feel like the author is trying to edify me on the psychological landscape of the soul. What I recognize is that in my twenties, I was fascinated by the suppressed passion of the characters and how Eliot analyzed actions to a minute degree. Now, I confess, I sometimes find the lengthy passages rather tedious.

So far, I’ve reread five of Eliot’s novels:

Daniel Deronda: More comprehensible, now that I am older, and much more fascinating than I remembered.

Romola: This time I understood the historical backdrop better, but I enjoyed the plot less.

Silas Marner: On previous readings, I found this story rather dull, but this time around I was thoroughly charmed.

The Mill on the Floss: I admit it: I have no need to read this novel ever again. The characters are too infuriating.

And then there is Middlemarch – my favorite of her novels. It is an altogether different scale of work.

This novel focuses on the provincial town of Middlemarch and the surrounding environs, and how the lives of the residents intersect and intertwine. A simplistic summary of the plot could focus on the soap opera quality of these characters' lives, but of course George Eliot is working on a much grander scale.

The three primary stories are

1) Dorothea Brook and Edward Causabon: Dorothea eagerly marries the bookish, intellectual Causabon with the hope of supporting him in his great life’s work, The Key to All Mythologies. All her idealism comes crashing down when she recognizes his pedantry and the outdated quality of his academic scholarship. To make matters worse, Causabon is insufferably patronizing to Dorothea and needlessly jealous of his cousin, Will Ladislaw. In his will, he enacts a cruel judgment against Dorothea and Will.

2) Tertius Lydgate and Rosamond Vincy: Ambitious surgeon Lydgate arrives in Middlemarch intending to raise the standards of medical treatments but is met with resistance and hostility from the local doctors. Along the way, he falls for Rosamond Vincy, the town beauty. Their rocky marriage strains under the pressures of the couple’s radically divergent views of what marriage should be.

3) Mary Garth and Fred Vincy: Spoiled Fred Vincy hopes to make his fortune by inheriting it. When his chance of inheriting a valuable estate comes crashing to the ground, Fred must face the fact that now he must work for a living. What is clear is his love for Mary, who is far too sensible to settle on a layabout as a husband. She recognizes that Fred has more to him than he is willing to admit. And so, Fred learns that in order to win Mary's heart, he must learn to grow up.

In her other novels, George Eliot focuses on one or two individuals, but in Middlemarch she broadens the cast of characters. While the plot primarily focuses on these three stories, there are others that make up the webwork of provincial life. Because of this wider scope, the plot moves along much more swiftly. There is still the careful examination of individual motivations and struggles, but this time Eliot plays off these analyses against one another. No one’s life is lived in isolation, so there are intersections by which characters influence one another, even if only in a tangential manner.

The predominant theme of Middlemarch is progress. Set against the Reform Act of 1832, the novel examines how individuals strive to bring lasting and positive change to society, only to be met by resistance to any change in the old ways of doing things. As with Lydate’s medical procedures, there is a strong core of antagonists who wish to keep to the old-fashioned methods of medicine, despite any evidence that treatments could be improved.

Likewise, Dorothea longs to raise the standard of living for villagers. Though she has the means to do so, she has to face with the limitations put upon women’s ability to act independently. Many times in order to make a generous gesture, she is forced to gain the approval of the men in her life. How successful could she have been if she had been permitted to use her own judgment? The men respect her intelligence but generally treat her in a patronizing manner.

I’ve read Middlemarch three times, and when I finished it this time, I wanted to start reading it over again.

Virginia Woolf famously stated that Middlemarch is “one of the few English novels written for grown-up people.” I certainly enjoyed it when I was 23, but now that I am much older, I appreciate it on a whole new level.

January 10, 2023

Book Review: All The Light We Cannot See

As soon as I started reading Anthony Doerr’s All the Light We Cannot See, I asked myself why I bothered even trying to write at all? Doerr’s language is poetic and evocative; it transports the reader to another time and place. All the senses are engaged, including the heart. Stunningly lyrical writing.

After reading a few more pages, I found myself inspired to be better writer. Not that I have to write like Doerr, but rather that I can dig deeper into my craft to become the best writer that I can be.

Which is all to say that All the Light We Cannot See is a transformative novel.

Set during World War II, it follows the lives of Marie-Laure and Werner Pfennig on separate trajectories that will eventually converge.

Sixteen-year-old Marie-Laure is blind. Her father, Daniel, the keeper of keys at a museum in Paris, makes puzzle boxes for her to figure out. He also constructs detailed maps of her neighborhood which she can learn by touch, thereby allowing her to explore the outside world.

After the German army invades Paris, Marie-Laure and Daniel escape to St Malo, where they live with his eccentric Uncle Etienne, a recluse who used to broadcast his brother’s science lectures from the attic of the house.

It is these lectures which Werner, a young German orphan, chances upon one night on a broken radio. They open his curious mind to explore more deeply into science and electronics. When his skills are discovered, Werner is sent to a boarding school which drills its students in Nazi values. Though he has little interest in Nazism, Werner is swept along by the rising tide of German Nationalism, and eventually he is drafted into the army, where his skills at radio are used to track down enemy signals.

Both Marie-Laure and Werner share inquisitive minds. Each of them shares a quickness at solving puzzles, not so much for the prize at the end, but for the process of discovery. Doerr weaves these two stories in alternating chapters. By painting short, episodic moments of their lives, Doerr manages to create a larger palate that incorporates the encroaching world war.

There is also a mystery involving a purportedly magical diamond which brings good luck to its holder but bad luck to those that person loves. Through the diamond’s symbolism, Doerr is able to raise questions about action, choice, and chance – such as, whether there is such a thing as fate or is it all merely “the seismic, engulfing indifference of the world.”

If I had finished this novel last year, it would have been on my Top Ten list for 2022. Right now, it stands a very good chance of being on 2023’s Top Ten list. My only complaint is that the epilogue felt a little protracted, but that could have been because I read half the book in a single night.

A winner of the Pulitzer Prize, and no wonder. It is that good.