Colin Mustful's Blog

October 13, 2025

Sources that Shape My Understanding of Dakota and Ojibwe History

As an author whose novels explore the history of Native displacement and settler-colonialism in the Upper Midwest—particularly in Minnesota and during the U.S.–Dakota War of 1862—I’ve long recognized the importance of grounding my work in Indigenous perspectives. Understanding history responsibly requires listening to those whose stories have been marginalized for generations.

On Indigenous Peoples’ Day, it feels especially important to acknowledge and honor the voices of Indigenous authors whose work has informed, challenged, and inspired my own storytelling. These sources offer not only historical insight but also a reminder of the resilience, ingenuity, and cultural continuity of Native communities.

Below are some of the works I have relied on most heavily, along with a brief summary of each:

The Heartbeat of Wounded Knee — David Treuer

David Treuer offers a sweeping history—and a vital counter-narrative—to the idea that Native American history ended with the 1890 Wounded Knee massacre. Combining history, reportage, and memoir, Treuer explores how Native communities survived and thrived through adversity, from forced assimilation and land seizures to military service and urban migration. This book is an essential account of the resilience and ingenuity of American Indian life from Wounded Knee to the present.

The Assassination of Hole-in-the-Day — Anton Treuer

This work examines the 1868 death of Hole in the Day, a powerful Ojibwe leader, not merely as a story of Ojibwe–white relations, but through the lens of Ojibwe culture, internal politics, and oral histories. By drawing on interviews with elders and a meticulous study of tribal dynamics, Anton Treuer provides an insightful look into a pivotal period in Ojibwe history.

Mni Sota Makoce: The Land of the Dakota — Gwen Westerman & Bruce White

Often overlooked is the long history of the Dakota people in Minnesota before the 1862 U.S.–Dakota War. Westerman and White trace Dakota connections to the land, explore their cultural and political history, and reveal how misunderstandings and betrayals in treaty-making set the stage for conflict. This work is both a detailed historical study and a celebration of the enduring Dakota presence in Minnesota.

Ojibwe Waasa Inaabidaa: We Look in All Directions — Thomas Peacock & Marlene Wisuri

Peacock’s personal history of Ojibwe culture, illustrated with photographs, artwork, and maps, traces the survival and thriving of the Ojibwe from pre-contact times to today. This book emphasizes the importance of storytelling, land-based knowledge, and cultural continuity.

Being Dakota — Amos E. Oneroad & Alanson B. Skinner

Originally collected in the early 20th century, this manuscript preserves stories, traditions, and cultural practices of the Sisseton-Wahpeton Dakota. Edited and published by Laura L. Anderson, it conveys the original voice of Amos Oneroad, providing insight into daily life, ceremonies, and folk narratives that might otherwise have been lost.

As we reflect on Indigenous Peoples’ Day, I encourage readers to explore these works and listen to the perspectives they offer. Each book opens a window into histories, cultures, and experiences that are often overlooked, providing a richer understanding of Minnesota’s past and the enduring strength of Native communities today.

If you’ve read any of these books—or others by Indigenous authors—I’d love to hear your thoughts and reflections in the comments. Engaging with these voices is an important step toward learning, understanding, and honoring the stories that have shaped this land.

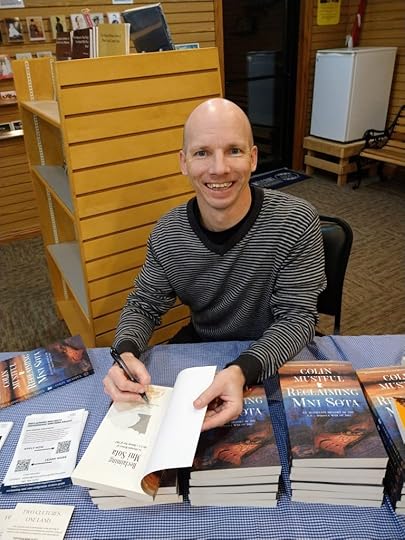

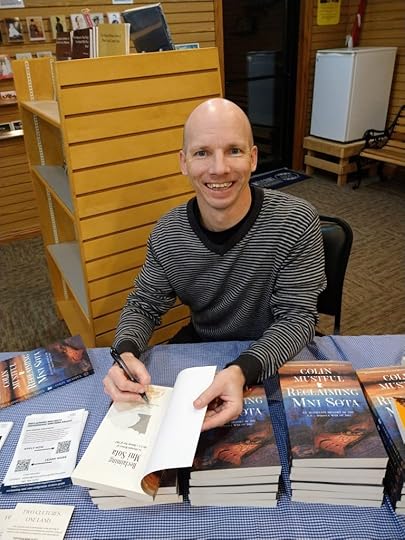

Colin Mustful is a celebrated author and historian whose novel Reclaiming Mni Sota won the Midwest Book Award for Literary/Contemporary/Historical Fiction. With a Master of Arts in history and a Master of Fine Arts in creative writing, Mustful has penned five historical novels that delve into the complex eras of settler-colonialism and Native American displacement. He is also the founder and editor of History Through Fiction, an independent press dedicated to publishing historical narratives rooted in factual events and characters. Committed to bringing significant historical tales to light, Mustful collaborates with authors as a traditional and hybrid publisher. Residing in Minneapolis, Minnesota, he enjoys running, playing soccer, and believes deeply in the power of understanding history to shape a just and sustainable future.

September 15, 2025

Remembering Laura Duley: A Life of Resilience Amidst Tragedy

In a recent blog post, I highlighted Never Let Go by Pamela Nowak, a remarkable novel that reimagines the life of Laura Duley. Through historical fiction, Nowak gives voice to a woman whose experiences of loss, survival, and resilience during the U.S.–Dakota War of 1862 deserve to be remembered. Historical fiction, when done well, has the power to breathe life into the silences left by history, and Nowak does this with great care.

Laura’s story is both heartbreaking and inspiring. Born on April 21, 1828, in Indiana, she married William J. Duley in 1848 and became the mother of eight children. By 1856, the family had settled in Minnesota, eventually moving to a small settlement at Lake Shetek in Murray County. But Laura’s life was marked by extraordinary loss. Two of her daughters drowned in the Mississippi River before the family ever reached Lake Shetek, and another child died in infancy.

On August 20, 1862, tragedy struck again when Dakota warriors attacked the Lake Shetek settlement, unaware that war had already erupted two days earlier at the Lower Sioux Agency. During the violence, three of Laura’s children—Willie, Isabella, and infant Francis—were killed. Laura herself, along with her surviving children Jefferson and Emma, was taken captive. Pregnant at the time, she endured weeks of forced marches, repeated assaults, and the eventual loss of her unborn child.

In November, with the help of Charles and Matilda Galpin and the remarkable bravery of the Fool Soldiers—a group of young Lakota men who risked their lives to save captives—Laura and her children were freed. She was reunited with William, who had believed them all dead. But the trauma of captivity, coupled with the grief of losing nearly all of her children, shaped the rest of her life.

The Duleys eventually rebuilt a life together, farming in Blue Earth County before moving first to Alabama and later to Tacoma, Washington, where their son Jefferson served as Chief of Police. Laura lived until 1900, outliving her husband and several of her children. Her strength in the face of unimaginable hardship is a testament to endurance and survival on the frontier.

Laura’s story is inextricably bound to that of her husband, William J. Duley. History remembers him as the executioner who cut the rope that ended the lives of 38 Dakota men in Mankato on December 26, 1862—the largest mass execution in U.S. history. His role, and the legacy it leaves, remains controversial. Together, Laura and William embody the human complexities of this difficult period in Minnesota’s past—stories of grief, vengeance, survival, and resilience.

As an author, I find myself returning to the Duleys’ life again and again. My hope is that my next novel will reimagine Laura and William’s lives in the years following the U.S.–Dakota War—exploring not only the tragedy they endured, but also the ways in which they sought to move forward. Their story, like so many from this era, asks us to confront painful truths about violence, survival, and the legacies of the past.

For those who want to learn more about Laura’s story, you can visit the Minnesota Historical Society’s U.S.–Dakota War website, which shares her personal account and the broader history of the conflict. You can also find her memorial at Find a Grave.

Colin Mustful is an author, historian, editor, and publishing professional. He is the founder and editor of History Through Fiction, an independent press dedicated to publishing historical narratives that are both authentic and engaging. As a novelist, Mustful has written five works of historical fiction exploring the complex histories of settler-colonialism and Native displacement in Minnesota. His novel Reclaiming Mni Sota won the Midwest Book Award for Literary/Contemporary/Historical Fiction.

Alongside his writing, Mustful has built a career helping authors navigate the publishing process through editing, book coaching, and education. He holds an MA in history and an MFA in creative writing, and he frequently speaks on the craft and business of historical fiction. Residing in Minneapolis, Minnesota, he balances his professional work with running, playing soccer, and advocating for the importance of history in shaping a more just and sustainable future.

August 15, 2025

Book Feature – Never Let Go: Survival of the Lake Shetek Women by Pamela Nowak

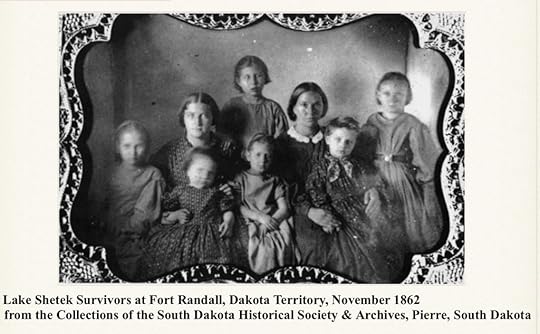

I recently came across Never Let Go by Pamela Nowak, a powerful historical novel that brings to life the harrowing stories of five women who survived the Lake Shetek Massacre. On August 20, 1862, settlers at Lake Shetek were attacked by Sisseton warriors during the outbreak of the U.S.–Dakota War. In the chaos, many hid in a nearby slough; fifteen settlers were killed, three women and eight children were taken captive, and twenty-one managed to escape to safety.

Drawing on extensive research—evident in her detailed list of sources—Nowak imagines the experiences of Laura Duley, Lavina Eastlick, Almena Hurd, Christina Koch, and Julia Wright, tracing their journeys from hopeful frontier beginnings to the terror of survival and the fierce, unyielding drive to protect their children.

I haven’t yet had the chance to read the novel, but I’m eager to delve into this compelling story. By sharing it here, I hope you’ll join me in discovering and honoring the resilience of these remarkable women.

About the novel

Sacrificing dreams and risking family, five women follow their husbands to an isolated Minnesota settlement. Struggling to survive, they develop resilience but none are prepared for the challenges they face when starving bands of Santee Sioux (Dakota) take up arms against the whites during the 1862 Dakota Conflict.

Laura Duley left Indiana as a newlywed. Promised a perfect life, she endured years on the hostile frontier and the loss of family only to be taken captive by the Dakota. Independent and protective, Lavina Eastlick was shot, beaten, and left for dead after witnessing the death of several of her children. In the hope that two still survived, she stumbled miles to reach safety. Christina Koch was a headstrong German immigrant determined to make a new life in America. Challenging her captors at every turn, she finally escaped to safety. Almena Hurd, unwavering in her commitment to family, was already dealing with a missing husband when she was sent alone onto the prairie with two small children. She survived by carrying one, then returning for the other, a quarter mile at a time. Julia Wright, the honest, practical wife of an unscrupulous trader, used her language skills and understanding of the Dakota to help the captives during their ordeal, becoming so valuable that her captor refused to release her to her rescuers, the Yankton Sioux Fool Soldier Band.

Their braided stories reveal a common will that allowed them to hold on no matter what and to never let go.

Get a CopyPraise for Never Let Go

“With great empathy and vivid storytelling, Nowak delivers readers into the heart of the frontier and the Dakota uprising of 1862. A tale of bravery, sacrifice, and determination, NEVER LET GO is rich with historical detail and a cast of unforgettable women who refused to accept their fate. A winner!”

—Heather Webb, USA Today Bestselling Author

“Never Let Go” is a rich, detailed 453 pages, the kind of novel you become lost in. About half the book details the women’s backgrounds; their childhoods, marriages, how they got to Lake Shetek, and their relationships with their husbands. So by the time the Indians attack, we know these women intimately and ache for their physical and mental suffering.

Nowak is equally respectful to the Indian’s frustrations. A character points out that it was not in the Dakota culture to kill and take captives. It was so alien they weren’t even sure what to do with the women. But treaties were broken and they were starving. Some of the Lake Shetek women were treated well in the camps, others suffered brutality. It was a group of young Indian men, known as the Fool Soldiers because they disagreed with the War Council, who guided some of the captives to safety.

The author includes helpful maps tracing the captives’ journey to release and charts showing the families at Lake Shetek and the relationships between the Sisseton and Wahpeton Dakota bands of Southwestern Minnesota in 1862.

Don’t miss this involving book, which also comes with a discussion guide.

—Twin Cities Pioneer Press, September 12, 2020 (Mary Ann Grossman)

From the Author

This is a story that is incredibly close to my heart. I grew up just a few miles from Lake Shetek and learned about the events there while still a child. I tried to write this story as a teenager (but, of course, knew nothing about fiction craft). It was the topic of research papers in high school and college and it remained with me for decades. When I knew it was time, I returned to Minnesota to again walk in the footsteps of these women, visit their cabin sites, and start deeper threads of research into what made each of them strong enough to survive their ordeals. The story grew beyond simply the events of 1862 because the roots of these women’s strength lay in the lives they lived.

As a historian as well as a novelist, I took great pains to remain true to the historical record wherever possible. However, my purpose was to make the stories of Laura, Lavina, Christina, Almena, and Julia come alive rather than to offer a scholarly reporting of events. While I was able to locate clues to their major live events, I could only surmise their personalities, their family interactions, their dreams and motivations, conversations, or what they thought and did in their daily lives. I have not changed any of the facts I was able to uncover. However, to create my story, I filled in the gaps and developed the women as characters, from my imagination, around factual events. This is a novel, not a history, but I hope it is one that does justice to the history.

Author WebsiteJuly 11, 2025

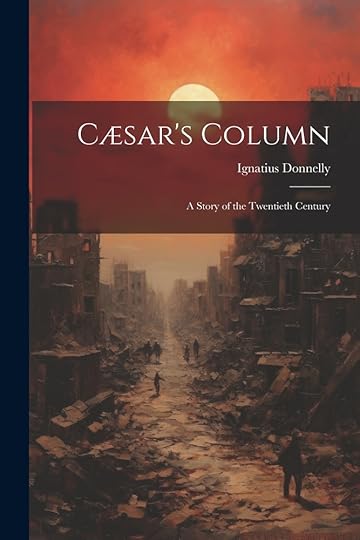

Caesar’s Column: Minnesota Author’s Early Vision of Dystopia and Alternate History

I’ve always been fascinated by alternate history—the idea of asking “what if?” and exploring paths not taken. It’s a big part of why I wrote Reclaiming Mni Sota, my own novel imagining a different outcome for Minnesota’s 1862 conflict between settlers and Indigenous people.

But alternate history isn’t new to Minnesota literature. More than a century before I was writing, Ignatius Donnelly, a Minnesota politician and populist, published one of the most striking dystopian novels of the 19th century: Caesar’s Column: A Story of the Twentieth Century.

Published in 1890, Caesar’s Column was a huge success in its time, selling over 250,000 copies. It’s a grim, apocalyptic vision of the future—an alternate 1988 New York ruled by a brutal capitalist oligarchy and torn apart by violent revolution.

A Minnesota Author’s Dark VisionDonnelly was no stranger to big ideas. He was famous for his popular nonfiction on Atlantis and for drafting the 1892 Populist Party platform, which railed against what he called “a vast conspiracy against mankind.” His novel Caesar’s Column reflects these anxieties in fiction.

Written as a series of letters (an epistolary novel), Caesar’s Column follows Gabriel Weltstein, a wool merchant from Uganda who visits New York by airship. The city is enormous—ten million people—ruled by an oligarchy that maintains order through a vast police force and a fleet of armored dirigibles called “demons.”

Weltstein quickly discovers the misery of the working classes, who live in hopeless poverty. He becomes involved with a revolutionary movement, the Brotherhood of Destruction, led by the fearsome Caesar Lomellini—a man whose farm was foreclosed by bankers and who seeks revenge at any cost.

A Violent Uprising—and a Monument to Civilization’s EndDonnelly’s New York is dazzling in its imagined technologies—airships, televised newspapers, menus on screens—but rotten to the core. The oligarchs are corrupt and merciless, and the rebellion that topples them is just as brutal.

When the uprising comes, the Brotherhood destroys the police, sacks the city, and turns to wholesale slaughter in revenge. At the height of the bloodshed, Caesar orders the dead piled in Union Square and entombed in concrete, creating the monument that gives the novel its title:

“We won’t make a pyramid of it—it shall be a column—Caesar’s Column… It shall reach to the skies! And if there aren’t enough dead to build it of, why, we’ll kill some more.”

An inscription on the column declares:

“This great monument is erected… in commemoration of the death and burial of modern civilization.”

In the chaos that follows, even the revolutionaries lose control. Weltstein flees the burning city by airship and eventually escapes to Uganda, where he helps found a utopian society with a new constitution promising liberty, education, security, and abundance for all.

Populism, Dystopia, and Alternate HistoryCaesar’s Column is a deeply political book. Donnelly used it to warn about the concentration of wealth and power he saw in the Gilded Age—a warning that feels remarkably modern. At the same time, the novel is steeped in the fears, prejudices, and contradictions of its era.

It’s a dystopian fantasy, but also an alternate history: Donnelly didn’t just extrapolate technology, he imagined a different trajectory for civilization—one shaped by revolution, collapse, and attempted renewal.

That’s something I find compelling about the genre. In Reclaiming Mni Sota, I tried to do something similar, asking: what if the Dakota and Ojibwe peoples successfully united and reclaimed Minnesota? What would that victory mean for them, for settlers, and for the shape of American history?

Why Read Caesar’s Column Today?More than 130 years later, Donnelly’s novel is still unsettling. It’s part social critique, part science fiction, part nightmare prophecy. As a Minnesota author, I’m struck by the ambition of his vision—and the power of alternate history to challenge us to see the past, and the future, with new eyes.

If you’re interested in dystopian classics, political fiction, or the roots of alternate history as a genre, Caesar’s Column is worth exploring—even if just to see what one Minnesotan imagined our future might become.

Discover an alternate history set in Minnesota.

Discover an alternate history set in Minnesota. In Reclaiming Mni Sota, the true and lasting results of history are challenged. Acting as individuals, striving to protect ourselves and our families, it’s impossible to understand our role and impact in the much larger march of time. The United States is an abundant, beautiful land filled with wealth and opportunity, but its history is scarred by inequity and loss. What if the defeated became the victors? What would that mean for the world today and how would that illuminate the wrongs of the past?

June 13, 2025

The Sky Turned White: Minnesota’s Grasshopper Plagues, 1873–1877

Lately, I’ve turned to A History of Minnesota, Volume III, by William Watts Folwell to learn more about settler-colonialism in the aftermath of the U.S.–Dakota War of 1862. These were formative years—marked not only by displacement and resettlement, but also by unexpected environmental catastrophes that tested the endurance of newly arrived settlers. One of the most dramatic of these was the grasshopper plague that swept across the state between 1873 and 1877.

A Storm of Wings

It began on June 12, 1873, in southwestern Minnesota when farmers saw what looked like a snowstorm heading toward their fields. But the flurry wasn’t snow—it was insects. “Their flight,” recalled one observer, “may be likened to an immense snowstorm… a vast cloud of animated specks, glittering against the sun.” It was a swarm of Rocky Mountain locusts, descending on young fields of wheat, oats, corn, and barley.

In just hours, crops were stripped down to the soil. For many, these were the first or second harvests after establishing homesteads—crucial for survival. As the locusts laid eggs deep in the soil, it became clear this wasn’t a one-time disaster. Over the next five years, the grasshoppers returned, spreading farther across the state and devastating hundreds of thousands of acres.

Minnesota Historical Society

Minnesota Historical Society

Desperate Measures

Farmers tried everything they could to fight back. They beat the insects with flails, dragged ropes through fields, set fire to prairie grass, and even filled ditches with coal tar. Some built “hopper dozers”—sheet metal contraptions smeared with tar or molasses to catch and burn the pests. But nothing worked.

Counties offered some aid, though rural governments were often ill-equipped for widespread relief. According to one 1875 report to Governor Cushman K. Davis, up to 1,500 farmers were left “utterly impoverished.” Yet skepticism lingered. Some questioned whether the damage was as severe as reported—echoes of the social tensions around who deserved assistance and why.

State Response: From Charity to Compulsion

The state cycled through three governors during the plague years. Governors Horace Austin and Davis offered limited state-funded aid and called on citizens for charitable donations. But John S. Pillsbury, elected in 1876, took a different approach. Convinced that frontier hardship was inevitable, he refused to provide direct relief. Instead, he pushed for eradication.

One of the more controversial measures came in 1877: every able-bodied man in infested counties was required to spend one day a week for five weeks destroying grasshopper eggs—or pay a fine of one dollar per day. The law, passed in March, was part of a broader effort that included digging deep ditches, rolling over larvae, and burning hatching grounds.

In a sign of the times, the legislature even called for divine assistance. On April 9, 1877, Pillsbury proclaimed April 26 a day of prayer. That spring, a late snowstorm damaged the locust eggs. By August, the swarms were gone. Whether it was coincidence or providence, the relief was tangible.

Aftermath and Legacy

The locusts left behind more than ruined crops. They etched themselves into the cultural memory of the region. Laura Ingalls Wilder famously fictionalized the experience in On the Banks of Plum Creek, while Ole Edvart Rølvaag’s Giants in the Earth captured the psychological toll on frontier families.

Though Minnesota would not see a plague of that scale again until the 1930s, the 1870s crisis reminded settlers that the land they had fought to control could still wield power over them—power as indifferent and sweeping as the wings of a locust cloud.

Sources:

Cartwright, R. L.. “Grasshopper Plagues, 1873–1877.” MNopedia, Minnesota Historical Society. https://www3.mnhs.org/mnopedia/search...

Folwell, William Wats. A History of Minnesota. Vol. 3. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 1926.

Colin Mustful is a celebrated author and historian whose novel Reclaiming Mni Sota won the Midwest Book Award for Literary/Contemporary/Historical Fiction. With a Master of Arts in history and a Master of Fine Arts in creative writing, Mustful has penned five historical novels that delve into the complex eras of settler-colonialism and Native American displacement. He is also the founder and editor of History Through Fiction, an independent press dedicated to publishing historical narratives rooted in factual events and characters. Committed to bringing significant historical tales to light, Mustful collaborates with authors as a traditional and hybrid publisher. Residing in Minneapolis, Minnesota, he enjoys running, playing soccer, and believes deeply in the power of understanding history to shape a just and sustainable future.

May 12, 2025

A Thoughtful Review of Reclaiming Mni Sota in War, Literature & the Arts

I’m thrilled to share that Reclaiming Mni Sota has been reviewed in Volume 36 of War, Literature & the Arts by Capt. Rebecca Layng. Capt. Layng is an Instructor of English in the Department of English and Fine Arts at the United States Air Force Academy in Colorado Springs. We first met years ago at the AWP Conference in San Antonio, and since then, she has contributed a powerful short story to my press, History Through Fiction, along with insightful blog content—like her piece “5 Famous Literary Quotes Explained: ‘‘Tis Better to Have Loved and Lost Than Never to Have Loved at All.’”

I’m especially honored by Capt. Layng’s review because of the care and depth with which she approached the novel. She thoughtfully interrogates the thematic heart of Reclaiming Mni Sota, exploring its setting, characters, and my motivation for crafting an alternate history of the U.S.–Dakota War.

One of the most striking elements of her analysis centers on a quote from Walt Whitman’s Leaves of Grass: “I do not ask the wounded person how he feels, I myself become the wounded person.” Featured in the novel, this line becomes, as Capt. Layng argues, a central lens through which to understand the book’s purpose—an effort to “become the wounded person” and offer an empathetic reimagining of historical narratives.

She also highlights the contrast between my two protagonists—Waabi, an Ojibwe boy from Madeline Island, and Samuel, a settler-colonialist from Vermont. As she writes, this juxtaposition “presents a clear delineation between white and Native experiences while also blurring the lines that keep humanity from seeing themselves in one another,” ultimately guiding readers toward deeper empathy. She notes how scenes in Waabi and Samuel’s lives intentionally diverge in ways that, as she puts it, serve as a deliberate “authorial move” to foster understanding in the reader.

Ultimately, Capt. Layng articulates the core question that I hoped would resonate through the novel. Reflecting on the contrast between nature’s beauty and the brutality of war, she writes, “It wasn’t meant to be this way… and perhaps even still it doesn’t have to be.” She concludes with a poignant observation: “Along with the heartbeat question pulsing throughout the novel, these scenes of war, destruction, and death held up against the beauty and vitality of nature appear also to ask, ‘what if?’”

I’m deeply grateful for Capt. Layng’s thoughtful reading and interpretation. You can read her full review of Reclaiming Mni Sota in Volume 36 of War, Literature & the Arts.

What if Minnesota was Mni Sota Makoce, a Native held and governed land?

A creative re-imagining of the U.S. – Dakota War of 1862, Reclaiming Mni Sota is an eye-opening portrayal of one of America’s most tragic, regrettable events. Told through dual narratives from each side of the conflict, Reclaiming Mni Sota confronts America’s history of settler-colonialism while illuminating the personal stories and heartrending choices that men and women, white and Native, were forced to make. Based on real events told through descriptive detail and fully developed characters, Reclaiming Mni Sota reveals the truth of our history while connecting it to the present and asking readers to question how things could have been different.

Get a Signed Copy of Reclaiming Mni SotaApril 21, 2025

A Letter to Lincoln: Bagone-giizhig and the Politics of 1863

The U.S.–Dakota War of 1862 was far more than a single conflict between U.S. and Dakota forces. What I find particularly interesting is that even as U.S. militia and Dakota warriors clashed on the battlefield, political maneuvering had already begun among U.S. and Ojibwe leaders, anticipating the war’s aftermath. On September 22, for instance, a large caucus of Ojibwe leaders traveled to the Minnesota State Capitol to offer their support to Governor Alexander Ramsey in the fight against the Dakota. While the Ojibwe and Dakota were traditional enemies, this gesture was likely more about currying favor with the U.S. government than pursuing old rivalries. Either way, it marked the beginning of a series of negotiations that would result in new treaties and reservation boundaries between the United States and the Ojibwe of Minnesota.

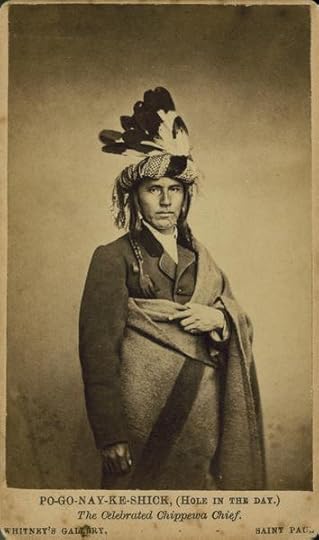

Bagone-giizhig the Younger was a capable leader that used the U.S. – Dakota War to negotiate better treaty terms for his people with the U.S. Government. Photo from the Wisconsin Historical Society.

Bagone-giizhig the Younger was a capable leader that used the U.S. – Dakota War to negotiate better treaty terms for his people with the U.S. Government. Photo from the Wisconsin Historical Society.

While the broader context of the U.S.–Dakota War and its repercussions is wide-reaching, I want to focus on one particular moment—a letter written by Bagone-giizhig, leader of the Mississippi Bands of Ojibwe, to President Abraham Lincoln, dated June 7, 1863.

Earlier that year, on March 11, while the Dakota were being held at an internment camp at Fort Snelling, a delegation of Ojibwe leaders from the Mississippi, Winnibigoshish, and Pillager bands negotiated a treaty in Washington, D.C. Notably, Bagone-giizhig was not part of this delegation, nor were his interests represented. The resulting agreement concentrated the Mississippi and Pillager Ojibwe at Leech Lake—a location already densely populated with other Ojibwe communities. Bagone-giizhig and his supporters were deeply dissatisfied with the arrangement.

In his letter to President Lincoln, Bagone-giizhig expressed the frustration of his people: “…we are unhappy….The young men are full of discontent, and further troubles are threatened unless something can be done to satisfy them.” He described the new land as little more than “swamps or marshes” and criticized its proximity to white settlements and their growing influence. Declaring that “the late treaty never will, never can, satisfy our people,” he asked that the agreement be annulled. He admitted he could not list every objection in detail but emphasized that the treaty “was negotiated, so far as my people had anything to do with it, by those who were thoughtless, and unaccustomed to look after the interests of the nation.”

Bagone-giizhig didn’t stop with a letter—he traveled across Minnesota, rallying support for his cause. His efforts paid off. Still reeling from the U.S.–Dakota War and wary of renewed violence, U.S. officials annulled the 1863 treaty. A new treaty was negotiated that, as historian Anton Treuer notes, “provided a substantial enlargement of the Leech Lake Reservation in order to accommodate the number of people who would relocate there.” Additionally, the Mille Lacs and Sandy Lake Ojibwe were allowed to remain on their existing reservations, reportedly due to their “heretofore good conduct” during the 1862 conflict. And in a personal victory for Bagone-giizhig, the new treaty included compensation for the burning of his house by two white traders—demonstrating the political influence he had come to wield.

Negotiations between U.S. and Ojibwe leaders continued well after the U.S.–Dakota War, shaping the reservation boundaries we still recognize today. It’s clear that the war directly influenced the negotiating power of both sides, and each used that leverage to serve their own goals. Bagone-giizhig, in particular, proved himself a skilled political actor, adept at navigating a rapidly shifting landscape—as shown by his letter to the president and the lasting changes it helped bring about.

Sources:

Anton Treuer, The Assassination of Hole in the Day (St. Paul, MN: Borealis Books, 2010).

“Annual report of the Commissioner of Indian Affairs, for the year 1863 [1863],” (Washington, Government Printing Office, 1864), https://search.library.wisc.edu/digital/ABQVZUYJSRAM2G83

Colin Mustful is a celebrated author and historian whose novel Reclaiming Mni Sota won the Midwest Book Award for Literary/Contemporary/Historical Fiction. With a Master of Arts in history and a Master of Fine Arts in creative writing, Mustful has penned five historical novels that delve into the complex eras of settler-colonialism and Native American displacement. He is also the founder and editor of History Through Fiction, an independent press dedicated to publishing historical narratives rooted in factual events and characters. Committed to bringing significant historical tales to light, Mustful collaborates with authors as a traditional and hybrid publisher. Residing in Minneapolis, Minnesota, he enjoys running, playing soccer, and believes deeply in the power of understanding history to shape a just and sustainable future.

March 18, 2025

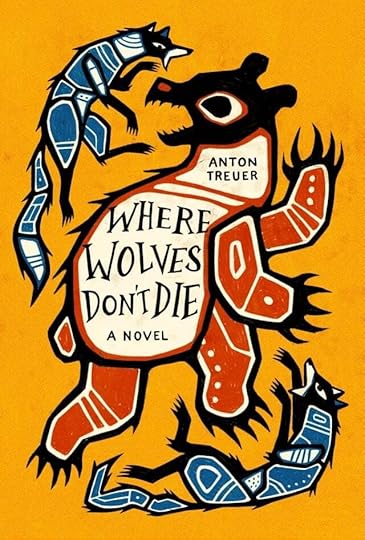

Exploring Tradition and Identity in Anton Treuer’s Where Wolves Don’t Die

Where Wolves Don’t Die by Anton Treuer is a captivating coming-of-age story that connects the past with the present.

Treuer’s teen fiction novel tells the story of Ezra Cloud, a fifteen-year-old boy from Northeast Minneapolis. After a dangerous encounter with a bully, Ezra temporarily moves to live with his grandfather on the Red Gut Reservation. There, he learns traditional trapping methods from his grandfather, Liam. Each day brings new lessons about the history and traditions of the Nigigoonsiminikaaning First Nation. Ezra grows to appreciate his time with his grandfather and becomes closer to his friend and secret crush, Nora. As the trapping season ends, Liam reveals a hidden pain. Then, in a tense encounter, they face Big Bear, and Ogimaa arrives. But will it be too late?

I enjoyed this novel, though it’s challenging for me to evaluate as I’m not the target audience. I prefer adult fiction and haven’t read much teen fiction. However, from a literary perspective, this novel has all the elements of an engaging and enlightening story. Ezra, the main character, develops quickly yet believably. Early on, he leaves Northeast Minneapolis, a place where he lives but doesn’t feel at home. His departure highlights the institutional racism faced by Native Americans and other marginalized communities. This is an important aspect of the story, showing the often-overlooked realities of living as a person of color in today’s American society. Treuer wisely doesn’t make this the central theme but presents it as an undeniable reality that Natives must navigate.

Another effective element is the portrayal of Native lifeways. Treuer’s characters are three-dimensional, discerning, and empathetic, rather than flat caricatures. They are vibrant and alive, providing an authentic view of both the tragic history of Indigenous peoples in North America and their enduring traditions. I was surprised by how much I learned about trapping and found Treuer’s descriptions of the great north truly facsinating.

The two elements I found less convincing were the climax and the absence of any mention of climate change. The climax felt a bit forced and implausible, and I wonder if a less dramatic ending could convey the same lessons. Regarding climate change, I understand Treuer wasn’t aiming to make a political statement, which was a wise choice. However, I read this novel in March when temperatures in Minneapolis soared into the 50s, 60s, and yes, even 70s. Much of the novel takes place in the natural world, and the characters rely on it for their livelihood. The real threat of climate change to traditional lifeways and its impact on plants and animals deserved some mention.

Overall, I recommend this book to both youth and adults. It’s a quick, enjoyable read that offers a sense of skill and authenticity found only in master storytellers and exceptional academics like Anton Treuer.

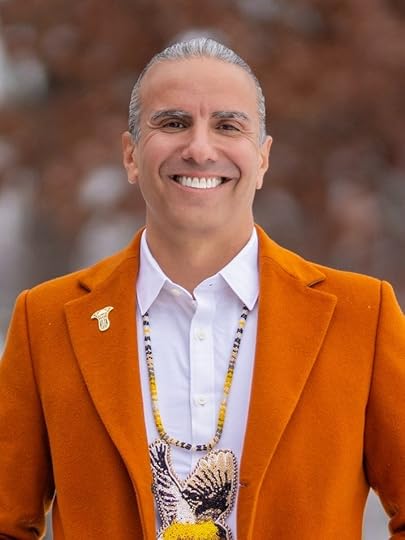

About the Author

Anton Treuer (pronounced troy-er) is Professor of Ojibwe at Bemidji State University and author of many books. He is building an Ojibwe teacher training program at Bemidji State University and his equity, education, and cultural work has put him on a path of service around the nation and the world.

February 24, 2025

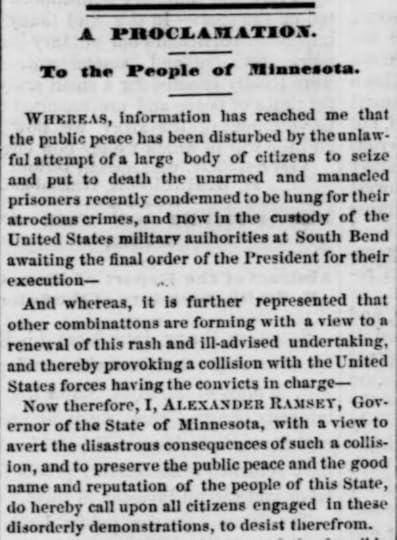

The December 6 Proclamation: A Call for Order Amidst Chaos

My research into the U.S. – Dakota War of 1862 began when I discovered that the Ho-Chunk, who lived on a reservation south of Mankato in 1862, were exiled from the state along with the Dakota in the spring of 1863. I wanted to understand why the Ho-Chunk, also known as the Winnebago, were banished despite not participating in the war. This led to my essay titled Unwarranted Expulsion: The Removal of the Winnebago Indians.

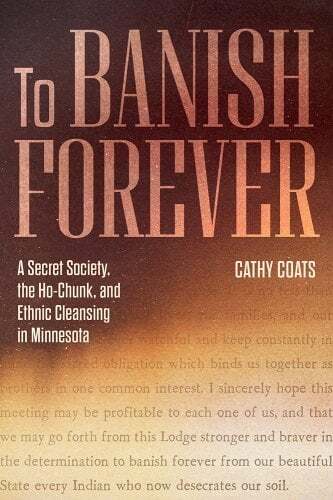

Recently, I was reminded of my research while reading To Banish Forever: A Secret Society, the Ho-Chunk, and Ethnic Cleansing in Minnesota by Cathy Coats. Coats provides excellent context for the Ho-Chunk removal and evidence explaining why it happened. I plan to explore Coats’ book further in a future post. For now, I want to share a startling piece of primary source evidence I was unaware of until reading her book.

After the U.S. – Dakota War, there was a strong call for harsh retribution against all Dakota people by the white settler-colonists in Minnesota. Henry Sibley and a military tribunal quickly charged and convicted 303 Dakotas of crimes they deemed worthy of execution. These sentences were sent to Major General John Pope in St. Paul, who forwarded them to President Lincoln in Washington, D.C., expecting swift approval. However, Lincoln did not act as quickly as the white citizens of Minnesota desired. Instead, he assigned two lawyers to review the cases before making a decision. Meanwhile, in Mankato, where the Dakota prisoners were held, threats of violence against them were rampant.

On December 4, 1862, the tension peaked when an angry mob marched to Camp Lincoln, the temporary Dakota prison. Reports indicate about 150 people, mostly unarmed, marched from New Ulm to Camp Lincoln but were stopped by the army. The crowd was loud but disorganized. All were taken prisoner and questioned by Stephen Miller, the Colonel overseeing the Dakota prisoners. They were released without incident, but the mere formation of the mob prompted a swift response from Governor Alexander Ramsey.

The response, dated December 6, 1862, and published in the St. Paul Daily Press on December 10, 1862, clearly reveals the fear, panic, and animosity in the community during that time. It is startling to read. I share it today to acknowledge and examine the reality of that era. It shows that while law and order were expected, retribution was foremost in the minds of Minnesota’s white citizens. This is evident in the line, “But whatever may be the decision of the President, it cannot deprive the people of Minnesota of their right to justice or exempt the guilty Indians from the doom they have incurred under our local laws.” Justice, as defined by the white settler-colonial population, would be served. I share the complete text with you now.

A Proclamation to the People of Minnesota

Whereas, information has reached me that the public peace has been disturbed by the unlawful attempt of a large body of citizens to seize and put to death the unarmed and manacled prisoners recently condemned to be hung for their atrocious crimes, and now in the custody of the United States military authorities at South Bend awaiting the final order of the President for their execution—

And whereas, it is further represented that other combinations are forming with a view to a renewal of this rush and ill-advised undertaking, and thereby provoking a collision with the United States forces having the convicts in charge—

Now therefore, I, Alexander Ramsey, Governor of the State of Minnesota, with a view to avert the disastrous consequences of such a collision, and to preserve the public peace and the good name and reputation of the people of this State, do hereby call upon all citizens engaged in these disorderly demonstrations, to desist therefrom.

The victims and the witnesses of the horrible outrages perpetrated by the savages may consider their sufferings and wrongs, a justification of this summary and high-handed method of retaliation. But the civilized world will not so regard it. Enlightened public opinion will everywhere condemn the vindictive slaughter of these guilty but helpless prisoners. The sober second thought of our own people will recoil from it with horror. The infatuated perpetrators of t will bitterly regret their ignominious share in the outrage which, if consummate, would inflict lasting disgrace upon themselves and the State.

Death, indeed, is the least atonement which these savage miscreants can make for their dreadful crimes. But the greater the crime the greater the need that its punishment should carry with it the weight and sanction of public authority.

It is not the blind fury of a mob to which Providence has entrusted the sword of public justice. The lawless violence which would anticipate the course of legal procedure by the massacre of these helpless prisoners in defiance of the authorities would deprive their punishment of all its legitimate effect.

Would it teach these savage men hereafter to respect the authority of a government thus openly condemned and degraded by an act of bold defiance on the part of its citizens.

Or, will it add to the sense of security of life on our frontier, to show that life is dependent on the will of an irresponsible mob?

Hitherto the conduct of our citizens in the midst of the extreme provocations which they have endured has been honorable to themselves and to the State.

The captured Sioux, instead of being indiscriminately slaughtered in the heat of passion as might have been expected, were conceded an impartial trial by a military tribunal. Those found guilty of capital crimes were condemned to death and now lay in durance awaiting the order of the President for their execution.

Our people indeed have had just reason to complain, of the tardiness of executive action in the premises, but they ought not to find some reason for forbearance in the absorbing cares which weigh upon the President.

The pressing and earnest representations repeatedly made of him from this Department of the necessity of proceeding promptly with the execution of the condemned Indians have been zealously sustained by the military and other authorities.

The Agent sent out by the Government gave the assurance upon his departure that he would spare no effort to procure an order to that effect. No official intimation has been received that the President contemplates any other course; and his final determination of the matter therefore soon be expected.

But whatever may be the decision of the President, it cannot deprive the people of Minnesota of their right to justice or exempt the guilty Indians from the doom they have incurred under our local laws. If he should decline to punish them the case will then clearly come within the jurisdiction of our civil courts. In a month the State Legislature will assemble and to them it may be safely left to provide for the emergency.

I appeal then to the good sense of the people to await patiently and peacefully the due course of law. I entreat them not to throw away the good name which Minnesota has hitherto sustained by a rash act of lawlessness which is neither necessary to the ends of justice, of personal security or even of private vengeance; but which would be subversive of public order and a perpetual stigma upon the community.

I entreat them as good citizens having at heart the public welfare not to add the injury which our young State has already sustained at home and abroad from its exposure to savage violence the worse and more permanent injury which it would suffer in the estimation of the world from the spectacle of barbarous violence among our own citizens.

Given under my hand and the Grand Seal of the State, at the city of St. Paul, this sixth day of December, A.D. 1862

Alexander Ramsey

Sources:

The Dakota Conflict Trials: An Account, UMKC School of Law, https://famous-trials.com/dakotaconflict/1525-dak-account

St. Paul Daily Press, December 10, 1862, https://archive.org/details/sep2186215thes/page/n3/mode/2up

A History of the Great Massacre by the Sioux Indians, in Minnesota Including the Personal Narratives of Many who Escaped by Charles S. Bryant and Abel B. Murch, https://www.google.com/books/edition/A_History_of_the_Great_Massacre_by_the_S/zwCyX5zkHeoC?hl=en&gbpv=0

Colin Mustful is a celebrated author and historian whose novel Reclaiming Mni Sota won the Midwest Book Award for Literary/Contemporary/Historical Fiction. With a Master of Arts in history and a Master of Fine Arts in creative writing, Mustful has penned five historical novels that delve into the complex eras of settler-colonialism and Native American displacement. He is also the founder and editor of History Through Fiction, an independent press dedicated to publishing historical narratives rooted in factual events and characters. Committed to bringing significant historical tales to light, Mustful collaborates with authors as a traditional and hybrid publisher. Residing in Minneapolis, Minnesota, he enjoys running, playing soccer, and believes deeply in the power of understanding history to shape a just and sustainable future.

January 16, 2025

Double Book Feature: To Banish Forever by Cathy Coats and The Lost Wife by Susanna Moore

I recently discovered two books—one fiction and one nonfiction—that really interest me. Although I haven’t had time to read them yet, I wanted to share them with you in case you’re interested too.

The fiction novel, The Lost Wife by Susanna Moore, tells the story of Sarah Wakefield. She was taken captive by the Dakota during the U.S.-Dakota War but was protected by Chaska. By the end of her captivity, Sarah sympathized with Chaska and the Dakota. I found this novel on the blog Herstory Revisited, created by author N.J. Mastro.

The nonfiction book is called To Banish Forever by Cathy Coats. It explores the troubling history of The Knights of the Forest, an organization founded in Mankato in 1863. Their goal was to remove all tribes of Indians from the State of Minnesota. I learned about this book from fellow Minnesota author Edward Sheehy.

Both titles are important historical reads that I hope to dive into soon.

The Lost Wife by Susanna Moore

Drawn partly from a true story, a searing, totally immersive novel about a devastating Native American revolt, and a woman caught in the middle of the conflict.

In the summer of 1855, Sarah Brinton abandons her husband and child to make the long and difficult journey to Minnesota, where she will meet a childhood friend. Arriving at a small frontier post on the edge of the prairie, she discovers that her friend has died of cholera. Without work or money or friends, she quickly finds a husband who will become the resident physician at an Indian agency on the Yellow Medicine River. As one of the earliest settlers in the area, Sarah anticipates unease and hardship, but instead finds acceptance and kinship with the Sioux women who live on the nearby reservation. She learns to speak their language, nourishing a companionship with them which far exceeds that which she shares with her strange and distant husband.

An endless flow of White settlers are clearing the forests and claiming land. The government has yet to pay the Sioux the annuities awarded them each July for the sale of the land, and starvation and disease begin to decimate the Sioux community. What inevitably and tragically follows is the Sioux Uprising of 1862. While seeking safety at a nearby fort, Sarah and her two young children are abducted by Sioux warriors. They are unexpectedly kept safe by one of the men, who protects them until their rescue six weeks later by federal troops. Because of her sympathy for the Sioux, Sarah has become an outcast, falsely accused of marriage with her Native American captor. Vilified by the whites and despised by her husband, she is lost to both worlds.

Intimate, raw, compelling, and brilliantly subversive, Susanna Moore explores the history of Native American suffering and the rapacious settlement of the Western frontier.

About the Author

Susanna Moore is a writer and teacher based in New York City.

She is the author of a dozen books, including In the Cut, The Whiteness of Bones, and My Old Sweetheart. Her memoir Miss Aluminum was published in 2020.

Susanna’s latest novel, The Lost Wife, is about a seminal and shameful moment in America’s conquest of the West. Drawing partly from a true story, it brings to life a devastating Native American revolt and the woman caught in the middle of the conflict.

To Banish Forever by Cathy Coats

The largely untold story of the Ho-Chunk exile from Minnesota, in which local white residents sought to expel all indigenous people from the region and deny Native claims to some of the richest farmland in the world.

In 1863, after the end of the US-Dakota War, a group of men in Mankato, Minnesota, formed a secret society. At the beginning of every meeting, members of the Knights of the Forest recited its ritual pledge, including these words: “I sincerely hope this meeting may be profitable to each one of us, and that we may go forth from this Lodge stronger and braver in the determination to banish forever from our beautiful State every Indian who now desecrates our soil.”

The Ho-Chunk people, who had not participated in the war, occupied a reservation about two miles south of Mankato on some of the state’s richest agricultural lands. The Knights–determined to claim these lands for their own profit–advocated for the removal of the Ho-Chunk, who had already been forced to move three times before settling in Blue Earth County of south-central Minnesota. Exploiting the fears of white people living in the area at the end of the brutal war, the Knights sent armed men to surround the Ho-Chunk reservation, threatening to shoot anyone who crossed the line. Within just a few years, the Ho-Chunk had been kicked off their land and removed to reservations outside of the state.

This is the story of the Knights, the Ho-Chunk, and the ethnic cleansing of southern Minnesota.

About the Author

Cathy Coats is the metadata specialist at the University of Minnesota Libraries. She previously worked at the James W. Miller Learning Resources Center at St. Cloud State University. She lives in St. Cloud, Minnesota.