Gregory N. Flemming's Blog

March 8, 2017

The Sudden Escape of Castaway Philip Ashton

On Saturday, March 9, 1723, a young fisherman named Philip Ashton — captured by pirates nine months before — was standing on the deck of a schooner when he saw a longboat approaching with seven of the pirates aboard. The men were rowing in the direction of the island of Roatan to collect fresh drinking water. Ashton called out to the ship’s cooper in the longboat, asking if they were going ashore. Yes, the cooper answered, they were. Ashton asked if he could go with them. The cooper hesitated...

August 10, 2016

Small boats in stormy seas

In a world where huge container ships, aircraft carriers, and cruise ships often exceed 1,000 feet in length, it’s hard to even comprehend battling a stormy ocean and massive waves in wooden vessels that were barely 50 feet long. Yet many of the fishing vessels I wrote about in my book, At the Point of a Cutlass — fishing boats that sailed in practically every month of the year from New England to the Canadian coast — were only 50 or 60 feet in length. The wooden sloop sailed in 1820 by Natha...

In a world where huge container ships, aircraft carriers, and cruise ships often exceed 1,000 feet in length, it’s hard to even comprehend battling a stormy ocean and massive waves in wooden vessels that were barely 50 feet long. Yet many of the fishing vessels I wrote about in my book, At the Point of a Cutlass — fishing boats that sailed in practically every month of the year from New England to the Canadian coast — were only 50 or 60 feet in length. The wooden sloop sailed in 1820 by Natha...

October 4, 2015

Hunting for Lost Cities and Buried Gold in Honduras

Two rocky islands known as the Cow (largest) and the Calf (smallest, in foreground), off Roatan, Honduras. Howard Jennings claimed to have found buried treasure on the larger island.

A new archaeological discovery, even when not a long-lost mythical city, always rekindles our sense of wonder. The latest discovery: in its October issue, National Geographic follows a team of researchers who’ve uncovered the ruins of a buried city in the mountainous La Mosquitia region of northeastern Honduras, a...August 28, 2015

Lost diary recounts whalemen’s fate

I went searching the other day in the quiet Chilmark Cemetery on Martha’s Vineyard to track down the headstone of a long-time island resident, William Homes. The lettering on many of the headstones dating back to the early 1700s is worn and faded, at times nearly impossible to read, and it took some time to find Homes’ marker. It was my son who finally spotted it near the crest of a hill. William Homes had served for much of the early 1700s as a minister in Chilmark. He also kept a diary whic...

I went searching the other day in the quiet Chilmark Cemetery on Martha’s Vineyard to track down the headstone of a long-time island resident, William Homes. The lettering on many of the headstones dating back to the early 1700s is worn and faded, at times nearly impossible to read, and it took some time to find Homes’ marker. It was my son who finally spotted it near the crest of a hill. William Homes had served for much of the early 1700s as a minister in Chilmark. He also kept a diary whic...

February 22, 2015

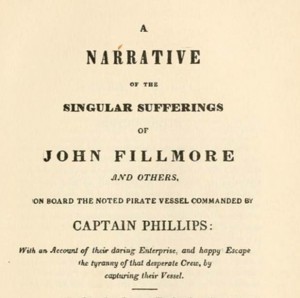

John Fillmore and a pirate’s sword

What surprised me the most, perhaps, while researching my book on Philip Ashton was discovering just how common young captives were aboard pirate ships during the early 1700s. Ashton’s story stands out because of its spectacular details — a young fisherman, captured by one of the worst pirates of the era, escapes and survives as a castaway on an uninhabited Caribbean island. But the more I pursued Ashton’s story, I uncovered the reports of dozens of other young men who were captured by pirate...

What surprised me the most, perhaps, while researching my book on Philip Ashton was discovering just how common young captives were aboard pirate ships during the early 1700s. Ashton’s story stands out because of its spectacular details — a young fisherman, captured by one of the worst pirates of the era, escapes and survives as a castaway on an uninhabited Caribbean island. But the more I pursued Ashton’s story, I uncovered the reports of dozens of other young men who were captured by pirate...

November 18, 2014

John Barnard of Marblehead

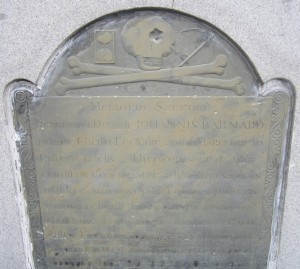

The headstone of John Barnard (1681-1770) in Old Burial Hill, Marblehead.

This month marks the 333rd anniversary of the birth of John Barnard, an adventurous New Englander whose curiosity about the world broke the mold of the traditional Puritan minister. Barnard spent hours talking with sea captains who arrived in colonial Marblehead, Massachusetts in the early 1700s, fascinated by their work and strategies for selling the tons of fish caught by local fishermen. In his younger years, Barnard...

October 31, 2014

Goat Island, Newport

Late in the day on July 19, 1723, the bodies of 26 executed men were brought by boat from Newport, Rhode Island over to a narrow strip of land called Goat Island, barely 1,500 feet from the town’s shoreline. Hanged for being pirates, the men were all buried near the north end of the island, not far from where the Goat Island Lighthouse stands today. Their burial marked just one of a series of events that, over the years, have made little Goat Island a figure in many chapters of American histo...

Late in the day on July 19, 1723, the bodies of 26 executed men were brought by boat from Newport, Rhode Island over to a narrow strip of land called Goat Island, barely 1,500 feet from the town’s shoreline. Hanged for being pirates, the men were all buried near the north end of the island, not far from where the Goat Island Lighthouse stands today. Their burial marked just one of a series of events that, over the years, have made little Goat Island a figure in many chapters of American histo...

September 7, 2014

Remembering a pirate’s victim

On the quiet Tuesday afternoon that follows Labor Day weekend, my son and I took a walk in the Chilmark Cemetery on Martha’s Vineyard in search of the headstone of Benjamin Skiffe, a prominent figure in early Tisbury and Chilmark before his death in 1717. The Skiffe family had settled near Mill Brook along what is today South Road in Chilmark and, during his lifetime, Benjamin Skiffe was owner of the fulling mill, captain of the local militia, and the island’s representative to the Massachusetts General Court for many years.

On the quiet Tuesday afternoon that follows Labor Day weekend, my son and I took a walk in the Chilmark Cemetery on Martha’s Vineyard in search of the headstone of Benjamin Skiffe, a prominent figure in early Tisbury and Chilmark before his death in 1717. The Skiffe family had settled near Mill Brook along what is today South Road in Chilmark and, during his lifetime, Benjamin Skiffe was owner of the fulling mill, captain of the local militia, and the island’s representative to the Massachusetts General Court for many years.

Benjamin Skiffe was also the uncle of a whaleship captain named Nathan Skiffe. I came to learn about Nathan Skiffe — and the tortuous final hours of his life — while writing my new book about New England pirate captives, At the Point of a Cutlass, published this summer. The younger Skiffe died at sea, the victim of one of the worst pirates to sail the Atlantic. But other members of the Skiffe family are buried in Chilmark, including Nathan’s uncle Benjamin. We found his worn headstone near the top of the gentle hill that sits at the back of the quiet cemetery.

It was a tragic twist of fate that placed Nathan Skiffe in the path of a pirate crew under the command of Edward Low on June 12, 1723. Low was racing out to sea, having barely survived a day-long battle with a British warship, HMS Greyhound, in which one of Low’s two sloops and about half of his men were captured. Low was in a rage when he spotted Skiffe’s whaling sloop about eighty miles offshore from Nantucket.

Boarding Skiffe’s sloop, Low’s pirates immediately singled out Skiffe as the captain of the whaling crew. Shouting and cursing, they “cruelly whipped him about the deck,” according to a report by one surviving member of Skiffe’s crew. Then Low raised his cutlass and hacked off both of Skiffe’s ears, one after the other. As Skiffe stood bleeding on the wooden deck of his sloop he may have begged for mercy, as many of Low’s captives did. Or other whalemen may have pleaded with the pirates saying that Skiffe was a fair and decent man, since pirates so often tortured captains that mistreated crews. But none of that mattered. “After they had wearied themselves of making a game and sport of the poor man,” a survivor recalled, “they told him that because he was a good master, he should have an easy death.”

That was little consolation for the Skiffe. Moments later, the pirates pointed a pistol squarely at Skiffe and shot him in the head.

At the Point of a Cutlass was released in June 2014 and is on sale now.

Read more about the hazards of early New England whaling and encounters with pirates in my recent article in Martha’s Vineyard Magazine here.

Read more about the hazards of early New England whaling and encounters with pirates in my recent article in Martha’s Vineyard Magazine here.

The post Remembering a pirate’s victim appeared first on .

August 28, 2014

The capture of John Fillmore

Two hundred and ninety one years ago today — on August 29, 1723 — a young fisherman on his first voyage at sea was captured by a small pirate crew off the coast of present-day Canada. That fisherman was John Fillmore, who would become the great-grandfather of the future U.S. president, Millard Fillmore. Just twenty-two years old, Fillmore had grown up near Ipswich, Massachusetts, a small coastal village about twenty-five miles north of Boston. The stories brought back to the village by men who worked at sea had a powerful impact on the young man’s desire to set sail himself: “hearing sailors relate the curiosities they met with in their voyages, doubtless had a great effect, and the older I grew the impression became the stronger,” Fillmore recalled.

Two hundred and ninety one years ago today — on August 29, 1723 — a young fisherman on his first voyage at sea was captured by a small pirate crew off the coast of present-day Canada. That fisherman was John Fillmore, who would become the great-grandfather of the future U.S. president, Millard Fillmore. Just twenty-two years old, Fillmore had grown up near Ipswich, Massachusetts, a small coastal village about twenty-five miles north of Boston. The stories brought back to the village by men who worked at sea had a powerful impact on the young man’s desire to set sail himself: “hearing sailors relate the curiosities they met with in their voyages, doubtless had a great effect, and the older I grew the impression became the stronger,” Fillmore recalled.

In the summer of 1723, Fillmore took his first job at sea, working aboard the fishing schooner Dolphin. It was on August 29 that the Dolphin was captured by a crew of pirates under the command of a man named John Phillips. Phillips and four other men had been part of a fishing crew working near Newfoundland when, only days before, they deserted their captain in a stolen schooner and set out as pirates. The Dolphin was one of the pirate Phillips’ first captures.

John Fillmore would sail as a captive aboard Phillips’ ship for eight long months — one of many men forced aboard pirate ships during this era, as I recount my new book, At the Point of a Cutlass. The pirate John Phillips had a temper so violent, Fillmore later recalled, that even members of his own crew hated him — and some even tried, unsuccessfully, to desert. “Phillips was completely despotic,” Fillmore recalled, “and there was no such thing as evading his commands.” Phillips nearly sliced Fillmore’s head off with a sword at one point and threatened to kill him at another, but Fillmore and several other captives were ultimately able to stage one of the most successful uprisings in the history of Atlantic piracy.

The break Fillmore and the other captives were desperately looking for came in April 1724. By now, Phillips’ crew had sailed to the Caribbean and back, returning again to the coast of Nova Scotia. They captured a sloop, the Squirrel, and took the new vessel as their own, moving their equipment, supplies, and weapons over the next day. The pirates allowed most of the captured sloop’s crew to go free, but kept its young captain, Andrew Harradine, from Gloucester, Massachusetts. Within a day of Harradine’s capture, Fillmore quietly approached him with the idea of planning an attack on the pirate crew. There were seven captives in on the plot, including Fillmore and Harradine, and it seemed possible that they might be able to overpower the eight pirates if circumstances were right.

The break Fillmore and the other captives were desperately looking for came in April 1724. By now, Phillips’ crew had sailed to the Caribbean and back, returning again to the coast of Nova Scotia. They captured a sloop, the Squirrel, and took the new vessel as their own, moving their equipment, supplies, and weapons over the next day. The pirates allowed most of the captured sloop’s crew to go free, but kept its young captain, Andrew Harradine, from Gloucester, Massachusetts. Within a day of Harradine’s capture, Fillmore quietly approached him with the idea of planning an attack on the pirate crew. There were seven captives in on the plot, including Fillmore and Harradine, and it seemed possible that they might be able to overpower the eight pirates if circumstances were right.

Their chance came close to noon on April 18 as the pirates sailed north. Fillmore and Harradine were standing on the deck with several of the other pirates. Fillmore stood casually spinning a broad axe that was lying on the deck with his foot. Then, in an instant, the men attacked. One captive grabbed the pirate standing next to him and threw him overboard. Fillmore bent over and picked up the broad axe at his feet and bore down on another of the pirates who was busy cleaning his gun, striking him over the head and killing him. Alarmed by the shouts and commotion on deck, Captain Phillips came out of his cabin to see what was going on. The captive who was manning the tiller, a Native American named Isaac Lassen, jumped at Phillips and grabbed his arm while Harradine struck him over the head with an adze. Finally, two French captives jumped a fourth pirate, killed him, and threw him overboard.

The remaining pirates were now far outnumbered and immediately surrendered. Fillmore and the other captives took control of the ship and headed home, arriving in Boston harbor on Sunday, May 3. The captives’ stunning overthrow of the pirate crew fascinated the town. The Boston News-Letter, the Boston Gazette, and the New England Courant each published accounts of how Fillmore and Harradine brought down Phillips and his men. Two members of Phillips’ crew, William White and the quartermaster John Rose Archer, were convicted and hanged. After the execution, the bodies of White and Archer were hauled back out to Bird Island in Boston Harbor (Bird Island no longer exists today, once standing where Logan Airport is today). White was buried on the island, while Archer’s body was hung there in a gibbet “to be a spectacle, and so a warning to others.”

At the Point of a Cutlass was released in June 2014 and is on sale now.

The post The capture of John Fillmore appeared first on .

July 22, 2014

Charles W. Morgan in Boston

The Charles W. Morgan, the “last wooden whaleship in the world,” spent the weekend in Boston, tied up in Charlestown in the shadow of the USS Constitution. The beautifully-restored Morgan set sail from Mystic Seaport this summer for the first time in nearly 100 years on a three-month cruise along the New England coast.

The Charles W. Morgan, the “last wooden whaleship in the world,” spent the weekend in Boston, tied up in Charlestown in the shadow of the USS Constitution. The beautifully-restored Morgan set sail from Mystic Seaport this summer for the first time in nearly 100 years on a three-month cruise along the New England coast.

Even before boarding the Morgan this weekend, I was struck by its size. The whaleship has a length of 113 feet, with a 27-foot 6-inch beam. That sounds like a big ship — until you imagine being aboard as she struggled around the notoriously brutal Cape Horn, weathered storms in the wide-open Pacific, or navigated Arctic ice. All of which men did a century ago aboard this 113-foot vessel.

Whaling has a rich history in New England, dating as far back as the early 18th century. I became interested in early New England whaling while researching my new book, At the Point of a Cutlass, since a number of young men who worked the whaleboats from Martha’s Vineyard and Nantucket were captured by pirate crews and forced aboard. Many of these whalemen were young Wampanoag men like Thomas Mumford, who I wrote about in a recent post here.

Whaling has a rich history in New England, dating as far back as the early 18th century. I became interested in early New England whaling while researching my new book, At the Point of a Cutlass, since a number of young men who worked the whaleboats from Martha’s Vineyard and Nantucket were captured by pirate crews and forced aboard. Many of these whalemen were young Wampanoag men like Thomas Mumford, who I wrote about in a recent post here.

At the Point of a Cutlass was released in June 2014 and is on sale now.

The post Charles W. Morgan in Boston appeared first on .