Martha Brockenbrough's Blog

July 20, 2014

The best writing advice Judy Blume ever got: an #LA14SCBWI interview

It's hard to imagine a writer with more influence over young readers than Judy Blume. It's not just that her voice is true and appealing. It's also that she writes about the things kids hunger for (which is probably why she is often in the sights of book censors).

It's hard to imagine a writer with more influence over young readers than Judy Blume. It's not just that her voice is true and appealing. It's also that she writes about the things kids hunger for (which is probably why she is often in the sights of book censors).

More than 80 million copies of her books have been sold, and they're available in more than 32 languages, making her beloved around the world.

You probably have your own Judy Blume moment: that time you found yourself inside the safety of a book with characters experiencing exactly the things you feared, struggled with, or wondered about.

Mine came when I read the book DEENIE during a swim meet when I was in sixth grade. A friend had lent it to me, because that is the way of Judy Blume books. They are passed hand to hand, as secrets are from mouth to ear.

I read it straight through in the hot, chlorinated air of that swimming pool, lying on my damp towel as I waited for my events to be called. And as it is with the books we loved when we were young, that one twisted itself into my DNA and lives there still. When I see things that remind me of those characters and their struggles, when I smell a hot blast of chlorine, back I go into that story. I'm not that same kid anymore, and so the story isn't the same story. It's better, and this is the genius of Judy Blume.

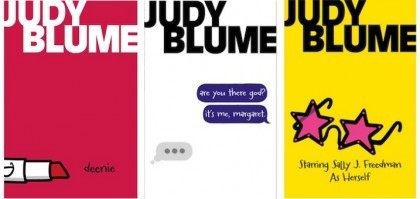

Judy is a big supporter of the children's writing community and serves on the SCBWI board of advisors. What's more, a fellow SCBWI member, the unstoppable Debbie Ridpath Ohi, illustrated a brilliant new series of covers for her classic books.

Judy will be at the sold-out SCBWI conference in Los Angeles next month, and even though she is on a book deadline (with her adult novel coming out next year), she took the time to answer a few questions for us.

Did you ever have a moment in your career when you thought you'd never get the hang of it?

Not so much in the beginning because I didn't know anything—as now, when I know too much. And in between I've had a lot of moments when I wanted to quit.

How did you move past that?

Don't over think it and just let it come. If it doesn't come today it will come tomorrow. Sometimes I just have to take long breaks between books.

What's the best piece of writing advice you ever got?

From my daughter, this week. (I'm having a hard time with revisions due the end of summer).

"Mother, just get up every morning, sit at your desk and write down anything and everything and it will come." And that's exactly what I'm doing. Sometimes, even when you know what to do, it helps to hear it again.

Every woman my age I know (including me) credits you with helping us navigate adolescence. Are there any authors who did that for you?

There were no YA book when I was a teen. I was reading from my parents' bookshelves at 13. Those books may not have helped me navigate adolescence but I learned a lot about life from them.

Visit Judy's website

Follow Judy on Twitter

The New Yorker on Judy Blume

June 13, 2014

Newbery winner Linda Sue Park on writing: #LA14SCBWI interview

Linda Sue Park, photographed by Sonya SonesLinda Sue Park is one of the most beloved authors writing for children today. Her many awards include a Newbery for 2002's A SINGLE SHARD, which I saw performed on stage in Seattle, where it was every bit as powerful as on the page. Her recent title A LONG WALK TO WATER was a New York Times bestseller.

Linda Sue Park, photographed by Sonya SonesLinda Sue Park is one of the most beloved authors writing for children today. Her many awards include a Newbery for 2002's A SINGLE SHARD, which I saw performed on stage in Seattle, where it was every bit as powerful as on the page. Her recent title A LONG WALK TO WATER was a New York Times bestseller.

In addition to being a top-notch writer and storyteller, Linda Sue is also a fantastic speaker and teacher. I took one of her intensives a few years ago at a summer conference, and the revision I did based on her advice became my first published novel.

She'll give a keynote this summer in Los Angeles on how we can make every word in our manuscript count. I can't wait to hear what she has to say.

If you haven't signed up yet, and you're thinking about it, the earlybird discount ends June 15. You can register here.

On the fence? I get it. These conferences are a big commitment in every way. But they're worth it. I also came up with the idea for THE DINOSAUR TOOTH FAIRY after my first Los Angeles conference. At another LA conference, I heard my agent speak for the first time (and thought then how much I would like working with her). And, as I mentioned earlier, Linda Sue showed me exactly what I needed to learn to sell my first novel. In all, six years after my first national conference, I have seven children's books either on the shelves or under contract. I know that would not have happened had I not taken that leap of faith.

Linda Sue was kind enough to answer a few questions. Here's hoping you find some useful information and inspiration to tide you over until August.

What's the best piece of writing advice you've ever received?

I’ve read and received all kinds of wonderful *inspirational* advice, but by far the most important tip was PRACTICAL. From the great Katherine Paterson: When working on a novel, write two pages per day. Every day. That’s it. Idiot simple. I actually begin my daily writing session by editing the two pages from the day before (sometimes throwing away the whole dang thing), but I don’t get up until I’ve written two new ones. They don’t have to be good. They just have to be done. Because I’m going to start my next session by editing them, right? I’ve written all of my novels that way—two pages at a time—and if I hadn’t read Paterson’s advice way back when I first started out, I’m convinced I never would have finished even one of them.

How do you know when your writing is working?

When I feel excited to get to work every day. I’m not saying it’s ice cream and balloons every time I sit down to write, but if I don’t have an overall feeling of eagerness to get at the story, I know something isn’t working.

What sort of research do you do before a project, and when do you stop with that part and start writing?

I try to do the lion’s share of the research before I start writing. Of course, there are always holes I have to fill in along the way (hopefully small ones…). But I think of research as revving up my engine. It helps create excitement for the project (see above). I let the story itself guide me regarding the question of when to start writing. I reach a point where I feel I have a good handle on the topic, and I know this by the fact that my use of post-its slows considerably. (I stick post-its in place while I’m reading, then transfer that info later to typed notes.) At the same time, my eagerness to start writing grows until I can’t rein it in any longer. Reaching that stage has varied for every book I’ve written. Sometimes a couple of months, sometimes years!

Linda Sue Park online

on Twitter: @LindaSuePark

May 20, 2014

The award-winning Cynthia Kadohata: #LA14SCBWI interview

There are lots of reasons to attend a national SCBWI conference. Among the best, though, is the chance to hear wisdom and inspiration from today's finest authors.

This August, we'll hear a keynote from Cynthia Kadohata, a National Book Award winner for The Thing About Luck, and a Newbery Medalist for Kira-Kira. The author of eight books for young readers, Cynthia was kind enough to answer a few of my questions. Curious about diversity in children's literature, Cynthia's best writing advice, and her favorite kind of taco? Read on!

Conference registration is open and conferences tend to sell out, so if you'd like to give your career a boost, sign up soon.

There's been a lot of discussion lately about diversity in literature. What are you trying to bring the world with the stories you write?

Apparently books by authors of color represented about 7 percent of all children’s books published in 2013. That makes my heart sink. That said, I don’t have a particular agenda when I write a book. I pick something I feel passionate about and I write it. My book Half a World Away, which comes out September 2014, has a white protagonist.

I want the stories I write to feel universal to readers whatever race is the main character. My mother once told me, “The more specific, the more universal.” I really agree with that and think if you write something as specifically as you can, the result will almost magically be universal.

For instance, my father’s life of hard labor inspired both Kira-Kira and The Thing About Luck. I wrote specifically about the hard work by a Japanese-American family in those books, but I hoped hard work by blue-collar employees is something relatable to all races. But I never, ever think about these things when I’m writing.

The emotional scenes in your book are so clearly drawn and resonant. In The Thing About Luck, for example, the grandmother's illness is so potent you can feel it progress. How do you prepare to write scenes like that? And how do you make them powerful and restrained at the same time?

As I write, I have to feel the way the character must feel. It can be almost a self-hypnosis kind of thing where I focus really hard on each scene until I can “catch” the feelings of a character.

Sometimes I can rely on my personal experiences, but other times I need to do research, and research is a big part of my process.

With Kira-Kira, I wrote a draft and put it in an envelope for my editor. Then something happened that devastated me and shook me to my core on the same day as I put the manuscript into an envelope. My boyfriend suggested I write down everything I was feeling. So I did, and later I put it verbatim into the manuscript, which I ended up sending to my editor after I’d worked on it further for a month. If there’s no personal experience involved, then once I’ve done the research, I have to catch the character’s feeling and write it down as quickly as possible before I lose it. There’s urgency involved, because I don’t have much time before I lose it—I feel like it’s a matter of a few hours, sometimes less. This probably sounds wacky … Anyway, that’s part of what I’m going to speak about at the conference.

What's the best piece of writing advice you ever got? What's your favorite writing advice to give?

The best advice I ever came across and the same advice I would give is “Make a mess, then clean it up.” That’s how I always write. For my first draft, I just rush through it in a month or so, and then I edit it over and over and over. Then my editor edits it over and over and over. So the “cleaning up” part takes much longer than the “make a mess” part.

Cleaning up can take two years. I absolutely cannot try to perfect each sentence in a first draft. It would take so long, and I don’t think what I wrote during the cleaning up phase would be very good. The rush of emotions I get in that first month of writing a book wouldn’t come to me if I tried to perfect each sentence. That’s probably a personal matter—some writers might feel differently.

Another way of interpreting “Make a mess, then clean it up” is that when you’re plotting, you can put the character into a mess, and then you clean up his/her mess.

Three tacos at a time, eh? What are your favorite kinds?

I only like beef ones! I’ve tried fish or chicken tacos a million different times, and I’ve never liked them. But beef ones—I LOVE them!

[image error]

More about Cynthia:

A National Book Award interview

May 15, 2014

The Problem with Godzilla (Warning: Contains Spoilers)

The original. It's still good!

The original. It's still good!

I'm in the midst of doing one last big revision of THE GAME OF LOVE AND DEATH, which comes out next year from Scholastic/Arthur A. Levine Books. Among other things, this means I have metaphors on my mind—and it's no doubt why I am not a thunder-lizard size fan of the new "Godzilla" movie.

There's a lot to like about it, especially great performances from Juliette Binoche and Bryan Cranston, neither of whom are on screen as much as I would like.

If you haven't seen the movie yet and don't want me to wreck it for you, stop reading now. (And have fun at the the theater, because movies are awesome.)

But if you're a writer and want to find out why this story didn't satisfy as much as it might have, pull up a chair.

.

.

.

The original "Godzilla," in case you've never seen it, is a Japanese movie released in 1954. On its surface, it's about a dinosaur-like thing that ravages the country. Metaphorically, it's a story about nuclear destruction. In the end, they don't beat the monster. He just walks away (to return later).

With nuclear weapons and nuclear power in general, we really did create a monster that is impossible, or nearly so, to kill. The movie works on both levels, which is a hard thing to pull off. A metaphor can't get in the way of the story. It has to make it resonate more deeply; otherwise, it's like putting a pinwheel on a top hat.

This latest version, which thankfully is better than the 1998 monstrosity starring Matthew Broderick, brings back Godzilla and modern-day giant moths. It's a good idea, to be sure, and the effects were great.

But this time, instead of working as a Cold War metaphor with the giant moths and lizard reaching a stand-off, the struggle between the two ends with a deux ex machina, which means "god from the machine" and refers to a story that ends when a divine force fixes things.

This is a total spoiler, but in the end, Godzilla kills the monsters because he wants to "restore balance" to a planet despoiled by nuclear power. So the moral of this environmental tale: Just get out of the way, humans. Mother Nature—the god in Godzilla—will take care of you.

Never mind that there's no such thing as an animal that exists to "restore balance." Sure, some serve that function, but that's a byproduct of evolution, not their intentional gift to the rest of the world. Living things are motivated to stay alive long enough to reproduce, and they'll generally do what it takes for that to happen.

I might have bought the magical balance monster if the story had contained a metaphor with meaning.

But the metaphor of this movie is reckless. Unlike the original, which said something profound, this movie says something stupid and dangerous.

The environmental story of the generation is the pending disaster of climate change caused by human activity—a fact supported by 97 percent of the scientific community, no matter how badly the mainsteam media has failed to communicate this, no matter how much the propaganda artists at Fox News would like to deny this.

According to the metaphor of the movie, the giant moths of global warming are the result of past excesses. But we don't need to worry about them. Nope! It'll be OK if we just do nothing! In Godzilla we trust!

This is what only the most uninformed and short-sighted politicians would have you believe: that climate changes are part of the natural cycle and that the planet will regulate itself as it always has. It's not true, even if it is a more comfortable story than the alternative.

I don't know if the filmmakers thought about this one bit as they made their movie. I suspect they didn't, and wouldn't want to be part of a propaganda machine. Nonetheless, this is how I interpreted the movie, and one reason it disappointed me on an artistic level.

My second disappointment with it was that it felt in many places like a piece of entertainment plotted according to the Blake Snyder "Save the Cat" school of screenwriting. If you haven't read this book, it outlines a storytelling method that responds to audience expectations about character, plot, and pacing. It's a really useful starting point, and a great way to understand what is happening on screen and why it affects us. This is what all stories want to do: entertain us by creating an emotional experience.

But it's not a really great way to write a story if your underlying metaphor isn't sound, and your characters are more pawns than fully realized humans.

Godzilla suffered a lot from this. At times, I coul dfeel the checklist of details contrived to manipulate my emotions: the death of a mother, the separation of a father and his child. Some of these moments worked—a scene where the Bryan Cranston character sees a gift his son had made for him 15 years earlier. This is a testament to his skill as an actor, at the least.

But other manufactured emotional moments. One such example: the one where the hero saves a child on a train. We didn't know the kid, we didn't get to know him, nor did we get any deep satisfaction of seeing him reunited with his parents, because the camera panned away before the hero interacted with them.

This is what can happen when you plot a story based on key moments instead of on the harder-to-predict, harder-to-craft moments that come from having really well-developed characters. In my experience, you can really only create these moments well when you know your characters deeply, and when you have put them into such emotionally harrowing situations that their response feels both like a surprise and an inevitability. Of course the good guy is going to save a child on a train. A great movie will make this feel a whole lot more special, especially if the good guy sacrifices something meaningful in the process. They tried here—in fact, the good guy gives up a toy soldier from his own childhood, ostensibly something he would have given to his own son. But if you were struggling to live, would you really care about a toy soldier? Probably not. It feels more like a manipulation than an authentic emotional moment.

For me, the writer's lesson in all of this is that it's hard to write a high-concept story with genuine emotional and metaphoric reasonance. For some people, this doesn't matter. A big enough lizard, loud enough explosions, and charismatic actors are enough.

"Godzilla" is getting great reviews so far, which means the movie is working for its intended audience. Being good, though, doesn't mean people will still be thinking of your story 60 years after it first comes out.

I don't think there are many writers out there who don't, at least in their dreams, hope of creating something that still means a lot to people decades later. You might not hit great with your work. You might only hit good. But no one's ever going to create anything truly great by relying on anyone else's formula, or by building a story from the outside in.

It's a fine place to start, but where you finish has to come from someplace deeper, someplace you can only find in yourself. It comes from the deep, like Godzilla. And it's hard work bringing it to the surface, but it's worth it every time.

May 1, 2014

The scary thing about diversity

A lot of people are talking about diversity in books and the many reasons this is vital.

What I haven't heard mentioned yet is the fear that can sometimes go along with changing perspectives and practices. So I'll talk about it. (And here's hoping I don't mess up too much. There's fear of that, too.)

In the children's book world, I'm the majority. I go to a lot of conferences, and when I look around, most of the people I see are white women. When I visit schools and bookstores, the same is true. And for sure, a lot of book characters are white girls.

When you're in the majority and people start talking about the importance of diversity, it can be uncomfortable thing.

First, you feel like a jerk. Your presence alone is crowding other, rarer voices out. All of the effort you've put into getting published, when viewed in this context, can feel terribly selfish. As if your dream is part of the problem. That things would be better if you would just go away.

This can be an especially hard feeling for women to bear. We still get paid less than men for equal work. And I'm old enough that I still remember when there was not a baseball or a basketball team for girls my age—I got to sit on the bleachers and watch my brothers play. Mine was the first generation to benefit from Title IX, and I'll be forever grateful to the teams that did make room for girls. It made a huge difference in my life.

And yet, for a lot of women writers, there remains a strong feeling that our male colleagues still get more respect and appreciation. I was once told by a librarian that the school didn't want our touring group if one of our male colleagues couldn't make it, because male authors are "so rare." Historically, nothing could be less true.

Given all this, it's been incredibly heartening to see the way my mostly female colleagues have embraced the need for diversity in what we read. This industry is full of big-hearted, wise, compassionate, and wonderful people.

And truly, the call for diversity is nothing to fear, even when you're in the majority demographically.

Working hard for this gets us where we want to be as a society: where all voices matter equally.

I don't want to live in a world where certain people matter more because of their skin color, their religion, or the size of their bank accounts. I don't want to live in a world where people feel lesser because they are different.

When we write, we create worlds. This is maybe the hardest part of our work as writers, but also the most thrilling. When we do it well, what we've created becomes real where it matters: in people's hearts and minds.

What kind of world do I want? One where every child can see him or herself in a book, where every child feels as if he or she can be a hero. I want to live in a world where young readers become more interested in others and develop empathy and compassion because of what they've read. And I want readers of all ages to know that everyone matters, not because of who they are or what they look like or believe, but simply because they are.

So let's write that world into existence. It's not about mattering less when you're in the majority. It's about acknowledging the everyone else matters as much.

There is room for all of us. There is also a need for all of our best efforts. I can't see a better way of working toward that world than by showing it to children in books.

March 29, 2014

If You Don't Mind Exploding Cats

If you don't mind cartoon cats who meet unfortunate ends, then you will like the German trailer for DEVINE INTERVENTION. I absolutely love this trailer, which conveys quite a lot of the book and is easily understandable, even for people who speak no German at all.

The German publisher, Dressler, has done a really great job with the book. They built me this website, made buttons, posters, and postcards, and even printed the first chapter. It's kind of thrilling, really, in part because German is the only other language I speak well enough to understand all that is happening.

Danke schön, Dressler!

March 21, 2014

Divergent and a Despicable Bias

"Divergent" opens this weekend, the movie based on Veronica Roth's bestselling trilogy. There's been a fair amount of coverage of what it signifies if the movie fares poorly—that YA books as adaptations are dead, that people are tired of everything YA has to stand for...

"Divergent" opens this weekend, the movie based on Veronica Roth's bestselling trilogy. There's been a fair amount of coverage of what it signifies if the movie fares poorly—that YA books as adaptations are dead, that people are tired of everything YA has to stand for...

This is so unfortunate.

For starters, I really feel for Veronica Roth. Her book has been unfairly singled out for criticism. I read this wildly misleading piece in the New York Times in January and wanted to send her a box of chocolates. It's simply not true that YA is all dystopians, all lucrative, or all written with ease by very young people. The article called this book "threadbare," which is a huge insult to the taste and hearts of the many people who loved the book. Just because you or I don't fall for a particular title doesn't mean it's a bad book. If even one person loves a book, it means the author did something right.

And while I had questions about the way Roth's world worked, I was able to put those aside and see it as a metaphor. Sure, it would be impossible to organize around a complex society around single attributes the way it's laid out in Divergent. But that very often is how high school feels. That we're all reduced to our simplest signifier, and it's hard to escape, and no one wants you to be more than one thing at a time. It's why "The Breakfast Club" was and remains resonant.

To enjoy the movie to its fullest, you have to be able to go into it thinking about things metaphorically, and not literally. For other forms of art, people seem to have no trouble doing this. No one looks at a Picasso and says, "Wow. That guy definitely couldn't paint noses."

With any piece of art, emotional resonance is more important than logic. It's not to say logic is unimportant, or that some books aren't better than others at creating both. But the purpose of a book is to give a reader a meaningful emotional experience, and Divergent did that for a lot of people, as will the movie.

I'm not saying the book or the movie rises to Picasso's level.

This movie is arguably striving more for entertainment than art, and it struggled at times to deeply establish the motivations and relationships between characters that would have made all of the violence and spectacle as resonant as they should be.

But this is true for most movies. And there's nothing wrong with being entertained. The moment that stops being important is the moment we've stopped being fully human.

I'm really bugged by the eagerness people have to dismiss something based on a YA book as inferior or the mere result of a trend. I hate the idea that this work we're doing and these books that so many people love represent a bubble. There's just too much substance there for this notion to persist.

I'm also bugged by the idea that YA is a genre. It's not. It's a marketing category, just as adult books are also a category. Both are split into genres that might include romance, science fiction, mystery, historical, horror, and the vaguer "literary." But YA ... it's not a genre that follows set conventions. The books are as diverse as adult books, as different from one another as people.

I object to the free pass that adult literary adaptations get. Many adult books are adapted into movies, and no one is making blanket generalizations about this practice. No one's saying, "If 'Gone Girl' tanks, no one's going to make adult books into movies."

This is because books written for adults are generally more respected than books written about the teen experience, simply because they are written about adult concerns.

It's an ignorant bias, as ignorant as respecting adults more than we respect teens simply because they are older. To understand how terrible this bias is, think of your least favorite adult. Then think of your favorite young person. Is your least favorite adult seriously deserving of more respect from the world simply on the basis of his age? Let's hope not.

What's worthy of respect is what is honest and true and made with care and skill. This can be a book as seemingly simple as WHERE THE WILD THINGS ARE or something as emotionally complex and literary as M.T. Anderson's Octavian Nothing books.

It's understandable, I suppose, to have this bias against young people. Teens are, by design, still developing. But this doesn't make them inferior. Nor does it make books about their experience inferior. Honestly, if I had to choose company or a book, I'd choose the curious and passionate teen over the jaded and satisfied adult any day. Just as I'd choose a passionately written, from-the-heart young adult novel over an adult novel that dwells in the land of middle-aged settling, where characters pop their pills and agonize about cruises and holiday homecomings, no matter how elegantly it's constructed.

There are some truly great books being marketed to young readers, books that are every bit as good as the best adult books. To lump them all together, making them easier to dismiss, is the same as writing young people off as inferior just because they're young.

I write for young people in part because I remember what it was like to have so much uncertainty in front of me, to have so many questions that fueled me. I write for young people who are deciding who they want to be and what they'll live and die for, because these choices matter. I write for young people because I care for them and believe in them.

And so should we all. Because before long, we will depend on them.

Divergent: The New York Times review of the movie, which I largely agree with.

March 13, 2014

Dodge Ball: A Modest Proposal

And remember! If you ever want to receive a strongly worded letter of your very own from me, try throwing a ball in the face of a child. My child or anyone else's ... I'm not picky. Also? A ball is sometimes just a ball. Sometimes, though, it's a metaphor for other things.

Dear Principal H.:

In the olden days, physicians used to treat certain diseases with mercury, which made the patients insane. Or physicians would slice open veins because everyone knows you feel better after a good bleed. Unless it's killed you.

In the less-distant olden days, people used to think it was OK to let kids throw balls at each other’s faces until there were no more faces left to hit and a victor was declared. And yet, because this sick and strange ritual was happening during gym class, it was healthy. They call this game dodge ball. I call it nuts.

Yesterday, my 45-pound fourth grader came home early from school, dizzy and in pain after being hit in the head during a school-sanctioned game of crazy. The hit was especially unfortunate, as she had already been knocked to the ground, and while this made her an easy target, she was, according to the rules of the game, off-limits. Oops!

My daughter is very concerned that I am going to get her beloved PE teacher in trouble. That’s not my intention. I don’t even want to get the person who threw the ball into trouble, although I would like him to know that I have excellent aim, and if he’d like to go mano-a-mom-o, I can make time in my schedule.

In all seriousness, though, the school needs to stop playing dodge ball, at least during gym class.

First, there are a lot better ways of getting exercise and developing hand-eye coordination. Anything that involves running and throwing balls at places other than heads and other body parts is better.

There is also prancercise. Have you seen it? Here's a link.

I’d love to see the kind of boys who throw balls at the faces of 45-pound fourth graders be required to prancercise instead. It would make for excellent yearbook photos.

Second, an overwhelming amount of evidence now exists that shows getting hit in the head is bad for the head--and not just in the short term. It can cause permanent damage. If anyone claiming to be reasonable wants to argue that dodge ball is worth brain damage, I will ask if he’s ever played dodge ball. The answer will be yes. And then I will rest my case.

Third, dodge ball is mean, especially for kids who are socially vulnerable. In this category, I do not include my daughter, who is a ninja, a wizard, and a unicorn all in one package. But I do think about kids who feel unloved at school, and who dread having their bodies used as targets for the kids who are already targeting them in other ways. On their behalf, I would like to lob a metaphorical red ball at the game’s face.

So, to summarize: Dodge ball is archaic. There are better alternatives. It’s dangerous physically and damaging socially. Let’s give it some mercury, open its veins, and kill the bastard.

I thank you for reading and hope I’ve been persuasive.

But, just in case, please be warned that if I ever hear of dodge ball being played in class again, I will show up with a ukulele and an anti-dodge ball anthem, and I will not leave until the game is officially dead at school. It should be noted that I am a very bad singer.

February 25, 2014

So you’ve attended an SCBWI conference: Now what?

One of the wonderful, talented new friends I met this weekend asked me this question on Twitter. (Hello, @JenipherLyn!)

What a great question. I’ve just returned home from what is probably my 20th major SCBWI event, if you add up the national and regional conferences and retreats I've attended over the past decade.

One thing I’ve learned: The day you get home from one of these huge things, don’t expect much out of yourself. If you’re fundamentally introverted, as I am, you’ll need a bit of time alone with your thoughts and your coffee cup before you’re feeling quite right again.

Once you’ve recovered from this particular conference, it’s time to seal in those connections you’ve made.

First, make a note of all of the people you met and spoke to. If you feel comfortable doing so, friend these folks on Facebook and follow them on Twitter. It’s especially true when these people are writers and artists.

Over the years, you’ll get to know them better and look forward to seeing them at future conferences. And you’ll feel palpable excitement when they sign with agents, publish books, go on tour, and win awards. Or even if they don’t and continue to work on their craft, celebrate life milestones, and generally make the most of their time on this planet.

For me, this stuff is important. We’re so often alone with our work that the pleasure of company from like-minded and like-hearted people is a source of joy and support. Many of my closest friendships have begun this way.

Second, take some time to thank the people who put this conference on. Lin Oliver, Steve Mooser, Sara Rutenberg, Kim Turrisi, Sally Crock, Kayla Heinen, Sarah Baker, Chelsea Confalone, and the rest of the staff at the international office would love to hear about your favorite moments. The work they do has changed so many lives, and no one will celebrate your successes with more enthusiasm.

If you had the good fortune to receive a critique from an editor or agent, it’s also nice to thank them for their efforts on your behalf. The point isn’t to sell a book or get a contract. It’s to show your appreciation for their time and expertise, and to begin building a relationship that will enrich your life with inspiration even if you never end up working with that person.

Finally, persist. If you keep learning and keep honing your craft, you will find an agent and sell a book. It might take a really long time, but if you truly enjoy the work and the company, then it’s time well spent. Over time, you'll learn that there won’t be one moment that changes everything for you, but rather, a series of moments in which you have learned what you need to learn to move forward. Have enough of those, and you will publish a book.

As great as it can be in those rare conferences when you have a stunning professional breakthrough, it’s probably more common to come home and feel a touch of despair in addition to all that inspiration you soaked up. Part of this despair might be exhaustion wearing an ugly mask. Travel, crowds, a flood of information—all of these things can take their toll.

But part might be knowing just how much work there is ahead of you.

If that’s the case, be kind to yourself. That great distance between you and wherever you want to be is something you cover in small steps. Don’t look at the mountain, just the ground in front of you. You might stumble. You might get lost. But these setbacks happen to all of us. Get up. Brush yourself off. Start climbing again.

Don’t give up on yourself and your dream, even if it feels really difficult at times. This work is hard for everyone. If it’s hard for you, too, chances are you’re doing it right.

And now, I am going to be revising my next novel, THE GAME OF LOVE AND DEATH, which Arthur A. Levine Books will publish next year, something I owe largely to a conference just like this one. It will be Arthur's and my third book together in as many years; I hope for similar successes for all of you.

February 19, 2014

Thanks, Lin Oliver

We are making a Lin Oliver sandwich.

We are making a Lin Oliver sandwich.

When I was a sophomore in college, I wrote an article for the school paper about massage. Always the schemer, I'd worked out a plan by which I would receive five free massages and write about them for the entertainment section, which I edited.

My lede in this utterly shameless enterprise referred to Dante's DIVINE COMEDY, speficially, the opening lines of the INFERNO. In the poem, the character finds himself at the halfway point of his life, wandering in a gloomy wood. And there I was! Halfway through my college journey! On a wooden massage table! In a gloomy room!

...

As with many things, it seemed like a good idea at the time.

It's funny the way good writing never leaves us, which is a very good reason to write children's books. If it's true that the books we read and love become part of us, it's even more that way with the things we read when we are young.

Probably not coincidentally, my novel DEVINE INTERVENTION has more than a few references to Dante, from the title to the structure of hell itself. And then there's that bit about lost souls being redeemed by love. Dante had his Beatrice, but because she'd already been well used by Lemony Snicket, I created Jerome.

All of this, of course, is a very long way of saying thanks to the one and only Lin Oliver, who co-founded the Society of Children's Book Writers & Illustrators, without which I would not be a published children's author.

I saw Lin last night at University Bookstore in Seattle. She and Henry Winkler, the co-author of the HANK ZIPZER series, were in town to launch a prequel for younger readers.

From where I sit, midway in my own life's journey, I can't overstate the importance of Lin or these books in my life. When my beloved daughter Lucy was in second grade, struggling in all sorts of ways in school, we'd planned a road trip. Getting away on weekends was hugely important then, because there was no getting away from a mountain of sadness during the week.

I stopped by the library for an audio book and found a couple of the Hank Zipzer ones. The kids laughed themselves silly listening to Henry Winkler read about an iguana that had wandered into a pair of boxer shorts. And they listened to the story again and again. It was only afterward that Lucy mentioned how much she identified with the narrator, a boy who struggled to read.

At first, I thought she was just monologuing from the book. Lucy can memorize almost anything she's heard instantly, and she's a really good actress. Also, I was in denial that the thing that gave me the greatest security in the world--reading and writing--was something my daughter struggled to do. After all, she was reading in kindergarten, and even though it took us a huge effort over many years to make that happen, she'd done it. (Or so I thought. She was faking much of it, making great contextual guesses.)

Still, by the end of the school year, I was ready to have her tested. Given how much time she spent with books, reading them was far more difficult than it should have been. Writing was nearly impossible for her even though she was a really bright kid.

The whole prospect terrified me. My entire sense of security in the world came from my ability to read and write. To know my daughter couldn't rely on that felt like sending her out in the world not only without armor, but without skin. For someone like me, already prone to anxiety, every day felt like a potential disaster.

Two years passed this way. School still wasn't working for her, so we had her tested again, because we figured the more we knew about how her brain worked, the more we could help her learn.

I'm not going into all of the details here, but let's just say things were hard enough for us that I took both kids out of school. I also pulled up stakes on my freelancing career. We even left Seattle for months at a time.

Anything was better than keeping my daughter in a place that wasn't right for her academically or socially, to say the least. (I learned later that it's common for kids with dyslexia to be mocked and excluded by their peers. I have no words for the rage this gives me on behalf of Lucy and other kids like her, but on the positive side, I feel a special kinship for parents of kids with any sort of disability. For many of these kids, school is the heart of darkness they enter every day. They're as brave as f*ck for hanging in there, and their families deserve love and support.)

This whole painful and necessary process started because of a book that made my daughter laugh herself silly--and then made her think. That is the magic and power of books. We see ourselves in them and we know we are not alone. We also learn we have choices. We can change directions and create a better life.

Even so, it's scary when you do something like this, entirely reinvent your life when there is no clear path going forward and no guarantees things will turn out OK. It's also incredibly tough to be both a teacher and a mom, especially when you have no experience working with a handful of complex learning challenges.

But in the many nights I lay awake during this time, I kept thinking about Hank Zipzer and Henry Winkler, who also is dyslexic and despite this, managed to go to Yale, become Fonzie, be a producer and director, and co-author with Lin of two dozen novels. So even if my own daughter wasn't going to be able to walk the same path I did, there would be a way for her to have a happy, productive, and successful life.

Henry and Lin and their books helped guide us toward a new destination.

And, after a rough year in the trenches with me and her sister, we found a new school for Lucy, one that specializes in teaching kids with dyslexia and language-related learning disabilities.

As with all good stories, the ending of this one touched back on the beginning. Lucy interviewed for this school over Skype when we were in Los Angeles for an SCBWI conference run by none other than Lin Oliver. The school offered Lucy admission on the spot and I felt a two-ton weight I hadn't even remembered I was carrying fly off my heart.

Even though middle school traditionally stinks, my girl is incredibly happy there. She dashes out the door in the morning on the way to school, and she's learned so much about how to learn that she feels ready to go to our neighborhood high school, even without a guarantee of support. At least for now, things are OK. Better than OK.

And they're that way for me, too. Giving up the freelancing that had sustained me from the time Lucy was an infant made room for me to do other writing. Thanks to Lin and Steve and Sara and Kim and all the other good people at the SCBWI, I've sold five books for young readers.

Three are out: DEVINE INTERVENTION, FINDING BIGFOOT, and THE DINOSAUR TOOTH FAIRY. Two more are coming: THE GAME OF LOVE AND DEATH, and LOVE, SANTA.

And I have more in the works.

And so, at what is probably the midpoint of my own life, I find myself in a wood that isn't gloomy at all. It's as sunny as these places can be, full of meandering and wonder and beauty and fellow travelers. Thank you, Lin, for lighting the way.