C.J. Adrien's Blog

November 17, 2025

The Viking Sack of Nantes, Part Deux

Welcome to the newsletter, where history, storytelling, and inspiration come together. Every week, I share some of the fun historical research or concepts I’ve encountered while writing my novels (and other things), as well as updates on my work and journey. If you were forwarded this message, you can join the weekly newsletter here.

Today’s DispatchViking History: When the Vikings took Nantes…Again.

Author Update: Novel Writing Month Check-In.

This week’s book recommendation.

Viking HistoryWhen the Vikings took Nantes…Again.

As I’ve been re-researching some of the backdrop history for my next novel to confirm certain details, I’ve found myself tangled up in the puzzle of Nantes in the 850s. Everyone knows about the famous sack of the city in 843, but almost everything about what happened afterward feels like a staccato of disparate mentions that don’t necessarily agree with one another. The events are there, but it feels like trying to read by candlelight in a smoky room.

The starting point is solid enough. On June 24th, 843, during the feast of St. John the Baptist, a Viking fleet sailed up the Loire River and attacked Nantes. The Annals of St. Bertin, along with the Annals of Angoulême, tell us they killed the bishop, Gohard, along with many others, and looted the city. Other, less reliable chronicles, including the Chronicle of Nantes, preserve the story of the bishop’s martyrdom, albeit with some curious additional details that cannot be verified, such as placing Hasting at the event. What’s certain is that the city was taken by force, and the Vikings even supposedly wintered on a nearby island afterward, acting as if they intended to stay.

Things became more complicated in the following decade. I keep seeing references to a “second sack” of Nantes, supposedly around 851 or 853, but when you start digging into the primary sources, nothing stands out as clearly as the 843 entry. Instead, you find hints. The political landscape changed dramatically after the Battle of Jengland in 851, when Erispoë defeated Charles the Bald. The treaty afterward effectively recognized Brittany’s independence and seems to have placed Nantes under Breton control. But how solid was their control? And what kind of city did they take over? I imagine a place still scarred from 843, half-rebuilt, half-abandoned, sitting on a frontier where Franks, Bretons, and Vikings all jostled for influence.

Then comes one of the most intriguing pieces of evidence: a document from 853 granting the Vikings royal permission to set up a market on the island of Betia, just outside Nantes. On the surface, this sounds almost peaceful, as if the same people who killed a bishop ten years earlier are now invited to establish a market. But when you look at it in the context of the political map of the time, it becomes clear how fluid and opportunistic relationships had become. The ‘royal’ power in question was the Franks, but the city had come under Breton control two years prior.

Only a few years later, in 856, the Annals of St. Bertin describe Vikings moving up the Loire again and strongly imply they were operating from Nantes as a base. This raises the question I keep coming back to: were they already in control of the city by 856? Did they raid it again, and no one bothered to write it down? Or was this simply a continuation of their habit of occupying places seasonally, the same way they would come and go from Noirmoutier depending on the tides of opportunity?

The chronicles don’t help. They record only what their authors thought necessary, usually events involving kings, bishops, and political crises. Frontier towns like Nantes appear only when something dramatic forces its way into the narrative. So it’s entirely possible that the Vikings slid in and out of influence there without leaving clear footprints in the surviving texts. What is clear from the evidence we have is that there was some funny business going on in Nantes in the 850s.

For my novel, this ambiguity is a gift. It allows me to paint Nantes in 853 as a city haunted by the memory of 843, caught between Breton rule and a rising tide of Norse activity. The evidence hints at a place where alliances were fragile, loyalties negotiable, and control of the city could change with the season. And in a way, what happens at Nantes in the mid-9th century foreshadows what is coming later in the century, when Viking power in the Loire region becomes far more entrenched with what historians have dubbed an ‘occupation’ of Breton lands.

If this topic interests you, I will be teaching a course on Early Medieval Brittany this coming January, covering the pivotal years from 799 to 1050. You can sign up for the course or purchase it as a Christmas gift for the history buffs in your life, click the button below:

COURSE: EARLY MEDIEVAL BRITTANY

Author UpdateNovel Writing Month Check-In.

This month, I set out to do my own version of NaNoWriMo. Even though the official event permanently closed last year, I wanted to give myself a good boost after the chaos of moving from Oregon to France. The plan was simple on paper: write every day, hit 3,000 words a day, and rebuild a steady cadence now that I’m a full-time writer again.

And at first, it worked beautifully. By the 10th, I was actually ahead of schedule. I felt like I had finally shaken off the dust of the move and settled into a new rhythm.

Then real life decided to have an opinion.

Last week was a perfect storm: meetings with the French administration, helping my wife navigate all the adjustments of living in a new country, a holiday that knocked out daycare, and our baby hitting a sleep regression with the precision of a military strike. Add in the fact that I had to dive back into research on the mid-9th-century Loire (and once I’m down that rabbit hole, I don’t come back quickly), and the writing pace suffered.

So yes, I’ve fallen a little behind. Not disastrously, but enough that I’m calling this week my regroup-and-catch-up week. The good news is that the story is flowing, the world is taking shape, and all this extra research is tightening the historical foundation of the new chapters.

In other words: still on track, still excited, still typing—just with a few more French bureaucratic forms scattered across my desk than expected.

Book RecommendationsRán’s Daughters, by Kaitlin Felix

Blurb:

Gyda Fiskwif and her all-women crew of Viking merchants set out to Al-Andalus only to discover that treachery, rather than treasure, lies in wait. A vengeful fire to reclaim her ship, her treasure, and her crew’ s freedom sets Gyda on a harrowing journey through Dyflin (Dublin), Jorvik (York), and eventually to the distant Norse settlements of Iceland at the height of the Viking Age. A saga of seasalt, blood, and gold, Ran’ s Daughters is a female-driven Viking epic like no other.

When a child on the shore waves to their parent as they stand in the beast-prow of a sleek ship of oak, journeying from the fjords of home to a far shore and plunder beyond reckoning, then it is well known that the child goes away from that sight wishing to one day sail the swan-road after them. And often, they do. Still more often, they die in the doing...

My take:

Ran’s Daughters offers a fresh and intriguing take on the Viking world through the eyes of a woman determined to make her mark in a society that would rather see her fail. Unlike many Viking tales with female leads, this story doesn’t shy away from portraying the harsh realities women faced when stepping outside prescribed roles. At every turn, the men in this world try to dictate her fate, and that tension gives the story real weight.

The cast of characters is diverse and engaging, with solid development early on and satisfying arcs that circle back by the end. The protagonist is flawed in all the right ways—complex, determined, and easy to root for.

What I found especially compelling is how Kaitlin Felix overlays modern themes onto the historical setting. The inclusion of gender-neutral pronouns and a character who uses sign language adds a layer of inclusivity that feels intentional and meaningful. As I’ve said before, we modern authors write for modern audiences, and using the past to explore contemporary themes is damn good storytelling.

The historical detail also felt well-researched and authentic, grounding the narrative in a believable setting while still leaving room for creativity.

All in all, Ran’s Daughters is a bold and thoughtful addition to the Viking historical fiction genre, and I applaud Kaitlin Felix for taking risks and telling the story she wanted to tell.

November 10, 2025

Revisited: How fast were Viking longships?

Welcome to the newsletter, where history, storytelling, and inspiration come together. Every week, I share some of the fun historical research or concepts I’ve encountered while writing my novels (and other things), as well as updates on my work and journey. If you were forwarded this message, you can join the weekly newsletter here.

Today’s DispatchViking History: How fast were Viking longships? Revisited.

Author Update: Vinci Books Relaunch.

This week’s book recommendation.

Viking HistoryHow Fast Did the Vikings Really Sail? Revisited.

This week, I’ve been writing a new chapter that involves long-distance travel—a harrowing sailing trip from Constantinople to Gibraltar—and as always, I’ve ended up down the same rabbit hole: how long should this journey take?

I’ve written about this topic before (How Fast Were Viking Longships?), but today I thought I would dive deeper into all the little things that would have affected their speed and the duration of Viking voyages.

The truth is, for all our reconstructions and experiments, the answer isn’t a simple one. Modern tests with reconstructed ships have shown us that the longship was, indeed, an astonishingly efficient design—the ‘speedboat’ of their day, if you will. But the speed tests that demonstrated this to us were tightly controlled and in specific conditions. In real-world journeys, the average speed recorded by longships has shown that they may not have exceeded the average for other vessels of the day by much.

The Viking Ship Museum in Roskilde has built several longships based on archaeological finds. In one real-world trial, their crew sailed fifty nautical miles across the Danish archipelago. They averaged 4 knots. That’s a far cry from the 13–17-knot top speeds often quoted from short bursts under ideal conditions. In practical terms, it means a day’s journey under sail may not have exceeded 30 nautical miles, depending on wind, current, and crew endurance.

When I write, I take these details into account. Suppose Hasting and his crew are crossing the Mediterranean in summer. In that case, I’ll start by tracing their most plausible route on a map, measuring the distance in nautical miles, and then factoring in average wind directions and weather for that time of year. If it’s winter, then I change the conditions.

Next comes the human reality—because these voyages were ultramarathons, not sprints (unless they’re being chased, which is an important detail). Crews had to rest, repair things, and resupply. On coasting journeys, I imagine they would have sailed no more than nine to ten hours a day, camping on shore each night. A ten-hour day is a long day at sea! And if they were camping on land at night, some of that sailing time would have been eaten up by sailing in and out of camping sites.

Longer stretches over open water were another matter entirely: days without rest, shared shifts, and the ever-present risk of storms or being becalmed.

All of this means that a voyage that looks like a quick hop on a map could have taken weeks longer than simply dividing the distance by an average speed would suggest. And yet, it’s this constraint that gives the journey texture. When you know your characters can’t simply “sail through the night,” you begin to imagine the dangers they may have faced to find a place to get a little shuteye.

Of course, it would be an awfully boring novel indeed if I stayed bogged down in the nightly routine of a crew on a two or three-month journey. That’s the balance I’m always chasing in my novels: historical realism grounded in the evidence, but written with the heart of an adventure story.

If you enjoy that kind of detail—the marriage of archaeology, history, and storytelling—you’ll find plenty of it in my Saga of Hasting the Avenger series. The newest volume, The Empress and Her Wolf, takes Hasting from the glittering palaces of Byzantium to the windswept coasts of the Eastern Mediterranean. Each mile of the journey is imagined as faithfully as history allows.

Author UpdateThe Vinci Books Re-Launch, Explained

Since announcing that a publisher in the U.K. picked up my Saga of Hasting the Avenger series, I’ve received some questions from readers about what to expect moving forward. It will indeed be a major transition that will change a few things, so I thought it would be a good idea to lay out the upcoming 60, 90, and 180-day plans, and beyond, for my followers.

The first thing to address is creative control and future volumes. Major publishers have a reputation for changing things for authors without their approval. While Vinci’s contract allows them to do so, it also includes strict conditions on when and how that happens, and it’s always done collaboratively with the author. That was part of their pitch to me—that I’d maintain creative control. Even better, I get to continue working with my current editor.

The process for releasing new books, however, will differ from how I handle it now. Once I submit a finished book to Vinci, it will go through their launch process, which takes about three months. Now that I can write full-time, I can establish a rhythm in which I work on the next novel in the series while the previous one is launching. If everything goes well, this could speed up my output. In practice, it will take about 60 days to work with my editor to finalize the manuscript, and then Vinci will take roughly 90 days to launch it. So, if I do this right, you should see a new novel every 90 to 120 days.

The next step is the rebrand. Vinci will completely rebrand the series, with new covers, formatting, and more. While I did a great job on my own, they have a team of top industry professionals, including Stuart Bache from Hodder & Stoughton and HarperCollins, to overhaul everything and prepare it for the big stage. The new covers should be ready in 60 days, and I will share them with you once they are ready. This overhaul will set the stage for a re-launch first in ebook format within 90 days, followed by a trade paperback with global distribution within nine months.

Here’s the kicker: the trade paperbacks will be available in pretty much every kind of store that sells books, including airports!

Last but not least, the series will be translated into ten different languages and sold in over 80 countries. The timeline for this is about nine months, just like the trade paperbacks in English. So, by next summer, you’ll be able to find my books pretty much everywhere in one of ten languages. Fun, right?!

I hope this information helps those of you who were wondering. I have nine books planned for Hastings’ life, and thanks to Vinci, I’m almost sure to finish them all much sooner than I expected.

Book RecommendationsThe Norse Queen, by Johanna Wittenberg

Blurb:

Ninth-century Norway, the dawn of the Viking era, -- a land shattered into thirty warring kingdoms. A woman could seize power if she were bold enough. Daughter of a Norse king, fifteen-year-old Åsa dreams of becoming a shieldmaiden. When she spurns a powerful warlord, he rains hellfire on her family, slaughtering her father and brother and taking her captive. To protect her people, Åsa must wed her father’s killer. To take vengeance, she must become his queen.

My take:

Johanna Wittenberg’s The Norse Queen is an enthralling dive into the life of Asa, a historical figure from the legendary Yngling dynasty. Asa, married to Gudrod the Hunter, is a powerful and compelling protagonist whose story is beautifully woven with rich detail and vivid imagination.

As someone who has always been fascinated by the Yngling dynasty, particularly through the Ynglinga Saga, this book was an absolute delight to read. Wittenberg’s portrayal of Asa and Gudrod brings them to life in ways that feel fresh yet deeply rooted in history. Having included some of their earlier characters, including Asa and Gudrod, in my own works, it was exciting to explore their story through a different creative lens.

This first in the series promises even more to come, and I can’t wait to see where Wittenberg takes these legendary figures next. Highly recommended for fans of historical fiction and Norse sagas.

October 30, 2025

By Popular Demand: The Hundred Years’ War — The Birth of Nations

Over the past two months, I have had the pleasure of teaching a six-part course on Chivalry for Medievalists.net. What started as an exploration of knighthood ideals evolved into a much broader discussion about how those ideals were tested, bent, and often broken by the realities of medieval warfare. The students were highly engaged, asking sharp questions about how the loose code of chivalry (more of a guideline) struggled to survive in the brutal crucible of fourteenth and fifteenth-century conflict.

After the fifth discussion section ended, several students asked the same question: Will there be a dedicated course on the Hundred Years’ War? I checked with Terri and Peter, who manage the course catalog for Medievalists.net. They had someone scheduled to teach it, but that person decided not to do it after all. I saw a chance.

While I may write mostly about the Vikings today, my fascination with the medieval period started with knights and chivalry, including the Hundred Years’ War. In fact, I have an entire series planned on the life of Geoffroy de Charny, famous for his last stand at Poitiers in 1356, once I finish Hasting’s saga.

So, I asked if I could teach the course. Terri and Peter agreed, and therefore I created: The Hundred Years’ War and the Birth of Modern Europe.

In this new series, we’ll follow the conflict from its tangled origins in feudal politics to its sweeping end in 1453, when France and England emerged forever changed. We’ll explore how this century-long struggle sparked the idea of national identity, led to the development of new technologies and tactics that transformed warfare, and caused social and economic upheavals that reshaped society.

You can find all the details, along with my current and upcoming offerings, on the newly launched Courses Page. There, you’ll also get a glimpse of what’s coming in 2026, including my Viking history courses and a series of writing courses and workshops designed to help aspiring authors bring the past to life on the page.

Teaching has been one of the most fulfilling extensions of my work as a writer and historian. It’s where I can turn my research, ideas, and what-ifs into shared exploration. And your feedback shows that the desire for deeper, story-driven history remains strong.

If you joined me for Chivalry, thank you for helping make that course a success. And if you’re new here, welcome. The journey through history continues to the battlefields of France and England, where modern nations were born.

October 26, 2025

The Viking Hasting Has Landed: My Saga Joins Vinci Books

When I was twelve years old, I wrote a story about a knight templar storming a castle to rescue a damsel in distress. I recognize the problematics now—but I was twelve! What mattered was that I had discovered storytelling and the thrill of creating worlds that felt alive.

In college, I dabbled in creative writing, but history stole my heart. I earned my degree in it, and later, when the PhD program I had been accepted into was shut down during the Great Recession, I became a schoolteacher instead. Standing in front of a classroom, I realized that storytelling was the key to bringing history to life. So, I began writing again, but this time with purpose.

My first novel, The Line of His People, was a humble effort. I queried 150 agents and was rejected by all of them. I wasn’t good enough yet. But Amazon had just launched its Kindle Direct Publishing platform, and I decided to take a chance. To my surprise, the book sold. I learned to design covers, build websites, run ads, and market my own work. My self-taught crash course in book marketing landed me a job in the private sector, where I spent the next twelve years helping companies grow.

And through all those years, I kept writing.

I wrote a second book and signed with a small indie publisher in Finland, which turned out to be an experience that taught me more about what not to do than what to do. I eventually got my rights back and decided to start fresh. I called my next project The Saga of Hasting the Avenger.

When I finished The Lords of the Wind, I remember saying to a friend, “This is the book I was meant to write.”

At first, it sold nothing. Then, slowly, the numbers climbed. 10 copies a day, 20, 30, 40—until it exploded. For more than a year, it held the #1 spot in Norse & Icelandic Historical Fiction on Amazon. My boss at the time asked how much I was making from my books; when I told him it was about the same as my salary, he just smiled and said, “Good for you.” He and his business partner remained exceptionally supportive of my author career and rooted for me the whole time.

Then came In the Shadow of the Beast with five thousand pre-orders. I thought I’d arrived. But algorithms change, the world changes, and the momentum slipped away for reasons I cannot quite explain. By the time The Kings of the Sea was released, I was selling fewer books than ever. Between COVID, a divorce, my dog dying, my car having engine trouble (yes, my life at one point was a bad country song), and rising production and marketing costs, I nearly quit.

But then, life surprised me again.

I met my wife, Crystal, a fellow Star Trek nerd who believed in my writing when I barely did. She encouraged me to keep going. She’d ask questions about what was going to happen to my characters in future books, and it got my creative juices flowing. I suppose I could call her my muse, but that would be awfully cheesy, indeed. To my delight, I discovered that she has an amazing talent for art, and in support of her, we published a children’s book together, I’m a Viking!

Around the same time, I met Professor Terri Barnes—now my co-host on the Vikingology Podcast—and together we rediscovered what I loved most: talking about Viking history with passion and joy.

Through it all, my success to date would have been possible without my readers. The Saga of Hasting the Avenger garnered nearly 6,000 ratings on Amazon, averaging 4.5/5 stars, which I’ve been saying for some time is proof that “I did something right.” Some of you are downright raving lunatic fans of Hasting, and I couldn’t be more honored.

The fan mail over the years has been incredible: heartfelt thank-you letters, speaking engagement invitations, marriage proposals (no joke), and, my favorite, Viking shields. Without you, my loyal readers, I would not have kept this dream going as long as I have. Seeing the positive outpouring for my characters kept my spirit alive.

Reinvigorated, I released The Fell Deeds of Fate in late 2024 and started writing the next installment. I told myself that if I kept at it long enough, someone would notice. Twelve years into this journey, however, I struggled believing that would ever happen. This past July, I released the fifth novel in the series, The Empress and Her Wolf, with that hope in mind, as well as the idea that, over time, more titles would sell more (which is algorithmically true).

And then, this past week, it happened.

U.K.-based publisher Vinci Books reached out. Naturally, I did my homework. When I learned that their CEO is Mark Smith—the very same Mark Smith who helped propel Stieg Larsson’s The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo to international fame—I had to read the email twice. This is a team who have built numerous global success stories. And now, they’re betting on mine.

So here it is: after twelve years of writing, publishing, failing, learning, and starting again, I’ve officially signed with Vinci Books. My Viking saga will be rebranded, relaunched in ten languages and dozens of countries, and—god willing—introduced to an audience far beyond what I could have reached alone.

It feels surreal to say it: I’m no longer an indie author. I write. They sell.

This moment is an ending but also a beginning. It’s the end of a long march through self-publishing, late nights, marketing spreadsheets, and self-doubt. And it’s the beginning of a new era, one in which I can focus on the work I love most: telling historically authentic stories.

Before the rebranding begins, though, I have one last thing to share with those who’ve been here since the start:

The original, independently published editions of The Saga of Hasting the Avenger—The Lords of the Wind, In the Shadow of the Beast, The Kings of the Sea, The Fell Deeds of Fate, and The Empress and Her Wolf—will soon disappear from circulation. Once Vinci takes over, these versions will be gone for good.

If you’ve ever wanted to own the originals, now’s the time. Consider them collector’s editions—the first printing of a saga that’s about to set sail for a much wider world. « BUY THEM HERE »

Thank you, sincerely, for being part of this long voyage as the next chapter begins. In the words of a famous Scottish movie star playing a soldier, “I’ll see you on the beach.”

October 17, 2025

The Aesthetic of the North: What Tolkien Helped Me See About the Vikings

Welcome to the newsletter, where history, storytelling, and inspiration come together. Every week, I share some of the fun historical research or concepts I’ve encountered while writing my novels (and other things), as well as updates on my work and journey. If you were forwarded this message, you can join the weekly newsletter here.

Today’s DispatchViking History: The Aesthetic of the North: What Tolkien Helped Me See About the Vikings.

Author Update: Teaching another course on medievalists (dot) net!

This week’s book recommendation.

Viking HistoryThe Aesthetic of the North: What Tolkien Helped Me See About the Vikings Artwork from the Oseberg ship—a certain aesthetic.

Artwork from the Oseberg ship—a certain aesthetic.No matter where I am, be it a book fair, conference, or even in social situations with people who know what I do for a living, one question tends to come up more than any other: What do you think makes the Vikings so popular? It’s a question we’ve tackled on the Vikingology Podcast as well, but with varying degrees of success. We all have ideas about what makes them attractive to a wide, global audience, as much today as they ever did. But what is it about them exactly that we’re all drawn to?

About two weeks ago, I came across an old interview with J.R.R. Tolkien, his first and last, I believe. The interviewer asked him that tricky question they like to ask authors: Why did you write your books? His answer gave me one of those “ah-ha!” moments that make me want to jump up and down like Tom Cruise on Oprah’s couch.

He said, “One of our natural factors is wishing to create, but since we aren’t creators, we have to sub-create. Let’s say, we have to rearrange the primary material in some particular form, which pleases. It isn’t necessarily a moral pleasing, but an aesthetic pleasing.”

You can see the clip here: » Tolkien Clip «

It took me a few days of chewing over his words before the ah-ha moment occurred. I honed in on the words “aesthetic pleasing” and considered what it meant. Aesthetics, at its core, is the study of beauty—why we find certain sights, sounds, and experiences pleasing or meaningful. It poses big questions, such as what makes something beautiful, whether beauty is universal, and why humans create art in the first place. In short, it’s the branch of philosophy that explores how and why we experience beauty in the world around us.

One of the things that drew me to Tolkien was his liberal use of Norse mythology, among others. There’s a specific something about it that, when I engage with it, gives me a deep sense of satisfaction. And that’s when it hit me.

Viking art, motifs, stories, and history all share a particular aesthetic derived from the common cultural linguistic boundary of Scandinavia at the outset of the so-called Viking Age. I would describe it as rugged natural forms, intricate patterns, and a mythic fatalism that feels ancient and strangely modern.

Perhaps the reason we’re drawn to the Vikings and the Viking Age is as simple as their aesthetic pleases us. Something about it, possibly undefinable (though many have and will continue to try), speaks to us on an aesthetic level, akin to how we are drawn to striking faces or haunting melodies that we can’t quite explain.

Now, much of that aesthetic is a later invention, and that’s precisely the point. The 19th and 20th centuries saw a great deal of sub-creating, as Tolkien would call it, incorporating modern preferences into that aesthetic. That may have helped make the Vikings even more appealing.

This all led me to the ultimate conclusion that the Vikings are popular because their aesthetic pleases, and it pleases because, on some level, their world still resonates with our sense of beauty and meaning. And perhaps, as Tolkien might say, that’s all it needs to do.

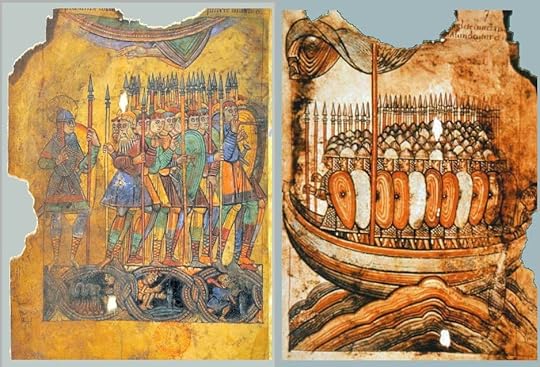

Author UpdateI’ll be teaching another course on medievalists (dot) net! A battle between Bretons and Vikings from The Life of St. Aubin.

A battle between Bretons and Vikings from The Life of St. Aubin.Give the gift of a fascinating course on little-known medieval history to your loved ones (or yourself) this holiday season. Starting in January 2026, I will be teaching a course on early medieval Brittany, its struggles with its Celtic identity, against the Frankish empire, and the invasions of the Vikings.

Book RecommendationsViking Kings of Britain and Ireland, by Dr. Clare Downham.

Blurb:

Vikings plagued the coasts of Ireland and Britain in the 790s. By the mid-ninth century vikings had established a number of settlements in Ireland and Britain and had become heavily involved with local politics. A particularly successful viking leader named Ivarr campaigned on both sides of the Irish Sea in the 860s. His descendants dominated the major seaports of Ireland and challenged the power of kings in Britain during the later ninth and tenth centuries. This book provides a political analysis of the deeds of Ivarr’s family from their first appearance in Insular records down to the year 1014. Such an account is necessary in light of the flurry of new work that has been done in other areas of Viking Studies. In line with these developments Clare Downham provides a reconsideration of events based on contemporary written accounts.

And, as always…Buy my novels!

October 6, 2025

What can we learn from the Vikings that will help us today?

Welcome to the newsletter where history, storytelling, and inspiration meet. Every week, I share some of the fun historical research I’ve done while writing my novels, writing reflections (and sometimes tips), and sharing updates on my work and journey. If you were forwarded this message, you can join the weekly newsletter here.

Today’s DispatchViking History: What can the Vikings teach us that can help us today?

Author Update: C.J. Adrien is featured in Ouest France! Again!

This week’s book recommendation.

Viking HistoryWhat can the Vikings teach us that will help us with our problems today?

Last week, I had the pleasure of attending a book fair at the Château de la Flocellière, where a journalist interviewed me for France’s largest newspaper, Ouest France. While the interview meandered in subject matter, the journalist posed a question at the end that gave me pause: What can we learn from the Vikings that will help us address our problems today? I could have taken my answer in several directions, such as developing critical thinking skills, understanding the progression of Western civilization, or the intrinsic pleasure of learning about a far-off time and place. My off-the-cuff answer? For me, they teach us (and indeed all historical peoples do) that our greatest obstacles today stem from the fact that we’re too comfortable and not grateful enough for it.

My Vikingology co-host, Terri, and I have tackled a related question: whether we would have liked to live in the Viking Age. Our answer—and we both agree—is an emphatic no. We enjoy our hot showers, access to modern medicine, and having survived childhood. We live today in the most privileged time in all of human history. Never before have so many people lived so long, so healthily, and so well as right here and right now (assuming you live in an industrialised nation). Childhood mortality has been so low and for so long that exceedingly few people alive today can recall any differently. It’s such an alien experience that many people have fallen for the false narratives that vaccines are a nefarious conspiracy meant to harm children. Mothers from all time periods outside the modern era, including the Viking Age, would have given anything for a medicine to prevent their children from dying from the myriad diseases vaccines now prevent.

And herein lies the crux of my answer to the journalist: what I take away from studying the Viking Age is that most, if not all, of our modern problems are essentially problems of our own making. We have it too easy. So easy, in fact, that our physiology, designed to endure the hardships of subsistence and survival in an unpredictable and unforgiving world, is working against us.

I’ve often asked aloud, “Is anyone else bothered that we’re destroying the planet so we can all be fat, sick, and miserable?” It’s a question that stems from my observation that our lives, filled with abundance and excess, have become unmanageable, and for no good reason. We’re anxious, depressed, and angry, not because our lives are hard—a Viking’s life was objectively hard—but because our lives are too easy. That has made us self-centered, self-seeking, selfish, fearful, inconsiderate, angry, and overall maladapted to a world where our every need is accessible to us at the push of a touchscreen button.

These traits are also making us less social. The so-called loneliness epidemic we’re living in is none other than the luxury of not having to cooperate with people we don’t agree with. What a privilege to be able to self-isolate! In the Viking Age, those traits would have risked our expulsion from our community, and exile was a death sentence. Community was life.

A recent book by Dr. Anna Lembke, called Dopamine Nation, has done much to bring this issue to light. Her central argument is that our brains evolved to balance pleasure and pain in a world of scarcity. Our reward circuits are designed to help us overcome starvation, being eaten, and to compete for scarce mating opportunities. In today’s society, our brains are overwhelmed by abundant sources of pleasure, from drugs to food to sex to myriad others.

Dr. Lembke describes the issue using what she calls “The gremlin theory of addiction.” She likens our reward pathways to a teeter-totter. On one side, we have pleasure gremlins, and on the other side, pain gremlins. When we seek out pleasures, it tilts the teeter-totter, and so the brain has to add more gremlins to the pain side to balance it out. But, remove the sources of pleasure, and the balance tilts back toward pain. And voilà! The brain makes us miserable to counterbalance all the pleasure. I’ll let her explain in more detail below:

The Viking Age—and I’ll focus on the Viking Age, even though what I have to say applies to most historical periods—was one of subsistence. Viking Age Scandinavians didn’t ‘betake themselves a-Viking’ because they thought it would be a fun adventure. They did it because the alternative was death. Every day was a struggle for survival. I’ve often said that Vikings were opportunists in the extreme (which I borrowed from Terri). They couldn’t go to the grocery store to top up on yogurt and ice cream. There were no doctors to treat their kidney stones. Recent studies have shown that their oral health was likely terrible. A majority of children died before adulthood. And to top it all off, even if you survived the day-to-day, there was a persistent threat that someone nearby might run out of food and come to take yours by force.

Dr. Lembke’s solution, and it’s one that I embrace, is deliberate exposure to pain and abstinence from (some) pleasures to balance out our dopamine reward system. This can take many forms, including abstaining from vices, engaging in regular exercise, fasting, and exposure to heat or cold, among others. They’re not a cure, per se, but a start to help regulate the body’s natural reward system.

Putting the effects of excess and abundance on the individual aside, there’s also the effect of a collective of people who all feel miserable. We see it today in our political discourse. The people who represent us feed into the anxiety, anger, and sadness of their constituents to great advantage. Their vitriol further enflames the discontent of the masses, and in a vicious feedback loop, misery continues to escalate.

Climate change. Authoritarianism. Disparity of wealth. War. On the surface, they seem insurmountable because we can’t seem to get along. But the ability to focus on these problems at all is a tremendous privilege in and of itself. In the Viking Age, people didn’t have the luxury of worrying about anything except their next meal and whether one of their children was going to die from a fever that night.

I am grateful to be alive today. And gratitude is the main lesson here, I believe. How terribly lucky that the people I love don’t have to die of plague, that we don’t have to fear being burned alive in our house tonight, that we have a grocery store for food, hot showers, interior plumbing, clean water, electricity, and books and movies! And how lucky that I don’t have to sail weeks on end on an open-decked longship across frigid seas just so I can scrounge enough silver together to get married! There’s an app for that now!

I’m grateful I don’t have to kill anyone just to survive.

It’s so easy to get swept up in the news and rage-baiting of the algorithms, to spiral on the state of the world, and to reach for that next dopamine hit like a baby crying for a baba to make it all better. Because we have it so good, we are all waiting for the other shoe to drop, and we’re all looking for that other shoe. That makes it harder to work together, to meet halfway in arguments, to compromise, and to otherwise keep this beautiful, perfectly imperfect wonder of a world we’ve created moving forward. I believe that a good dose of gratitude, acceptance, and exercise can go a long way in calming our minds and, perhaps, bringing us back to sanity.

To me, studying the Viking Age and being constantly reminded of their struggles gives me another perspective to frame my own challenges properly and reminds me to practice gratitude for my good fortune of living in our time, to stay focused on the here and now that I can control, and to remember that no matter what problems I face in this age of ease, they pale in comparison to the people who left home to rove. If those people (the Vikings) could make it work, then so can I.

Author UpdateFeatured in Ouest France!

I had the privilege of being featured in Ouest France for the second time in as many months. My day at the Château de la Flocellière was excellent. I met many wonderful people. Thank you to Dominique Théard for organizing the whole thing!

Book RecommendationsDopamine Nation

Blurb:

This book is about pleasure. It’s also about pain. Most important, it’s about how to find the delicate balance between the two, and why now more than ever finding balance is essential. We’re living in a time of unprecedented access to high-reward, high-dopamine stimuli: drugs, food, news, gambling, shopping, gaming, texting, sexting, Facebooking, Instagramming, YouTubing, tweeting . . . The increased numbers, variety, and potency is staggering. The smartphone is the modern-day hypodermic needle, delivering digital dopamine 24/7 for a wired generation. As such we’ve all become vulnerable to compulsive overconsumption.

In Dopamine Nation, Dr. Anna Lembke, psychiatrist and author, explores the exciting new scientific discoveries that explain why the relentless pursuit of pleasure leads to pain . . . and what to do about it. Condensing complex neuroscience into easy-to-understand metaphors, Lembke illustrates how finding contentment and connectedness means keeping dopamine in check. The lived experiences of her patients are the gripping fabric of her narrative. Their riveting stories of suffering and redemption give us all hope for managing our consumption and transforming our lives. In essence, Dopamine Nation shows that the secret to finding balance is combining the science of desire with the wisdom of recovery.

September 30, 2025

Legendary, Semi-Legendary, and Historical Vikings: What's the Difference?

Welcome to the newsletter where history, storytelling, and inspiration meet. Every week, I share some of the fun historical research I’ve done while writing my novels, writing reflections (and sometimes tips), and sharing updates on my work and journey. If you were forwarded this message, you can join the weekly newsletter here.

Today’s DispatchViking History: The difference between legendary, semi-legendary, and historical figures.

Writing and Publishing: Book Fairs Are Worth It.

Author Update: A Viking tour of Western France, anyone?.

This week’s book recommendation.

Viking HistoryThe difference between legendary, semi-legendary, and historical figures. Bishop Gohard was slain by Vikings in 843, allegedly by the Viking Hasing.

Bishop Gohard was slain by Vikings in 843, allegedly by the Viking Hasing.When the History Channel started promoting their show called Vikings, they made us a promise: that it was based on real history and would offer a rare glimpse into the Viking Age, free from the tropes that had plagued it for so long. No sooner had the opening episode introduced the protagonist, Ragnar, than I knew they had not told the whole truth. While the show opened with a strong pilot and gave the appearance of historical authenticity, Ragnar was not a historical figure. He’s a legend.

And so, because of that show, my work, and indeed the history I love to learn and teach, has been plagued by this pesky mythological figure from the sagas, and he refuses to go away. This past month, I attended three book fairs in France, where, while promoting my books about a real historical figure from the Viking Age, Ragnar kept coming up. “Ragnar attacked Paris,” many folks said. “And he did that ruse to get into the city.” All wrong.

I get it. It’s not their fault. A very popular TV show that promised historical authenticity made Ragnar the protagonist in many Viking Age stories in which he was not. Not unlike the Ragnar of the Sagas, History Channel’s Ragnar was an amalgamation of figures from the Viking Age, combined into one character to tell a compelling story.

Not unlike the Ragnar of the Sagas, History Channel’s Ragnar was an amalgamation of figures from the Viking Age, combined into one character to tell a compelling story.

The trouble is that Ragnar Lothbrok is not a historical figure. His story resides in a liminal place beyond the reach of verifiable history, one that historians have come to call ‘legendary figures.’ Indeed, there are three categories: Legendary, semi-legendary, and historical.

Legendary Viking FiguresStaying with Ragnar Lothbrok as a prime example, he is considered a legendary figure primarily due to his prominent place and role in saga literature. He figures prominently in the Saga of the Volsungs, with his own subsection titled "The Saga of Ragnar Lothbrok." These sagas tell of his conquests in England and his ultimate demise in a pit of snakes. It’s compelling storytelling.

Legendary figures are so-called for their place in legends. The figures who figure in the sagas are all legendary, meaning they are the product of no small amount of mythmaking. Could some of these stories hold a kernel of truth? Of course, and we have seen examples across history of these. However, I believe we are all far too quick to use that as an excuse to make the unreal real without ample evidence. Ragnar is a prime example.

The reason Ragnar is often considered historical is due to the numerous works by historians and amateur historians attempting to prove his existence. These works have attempted to link him to several historical figures who are mentioned in chronicles and charters of the time. A certain Reginherus, who led the fleet that sacked Paris in 845 A.D. (as attested in the Annales Xantenses, Miraculi Sancti Richarii, and the translation of St. Germain of Paris), is often evoked as having been Ragnar Lothbrok. The trouble is that the story of the sack of Paris and its aftermath (where Reginherus dies of dissentary two weeks after the attack) differs so much in form from the sagas that no concrete link can be made except to say that the man’s name was likely Ragnar. Ragnar may have been a common name.

Other figures have been suggested as perhaps inspiring Ragnar, such as Rorik of Dorestad, Turgesius of Dublin, and even Hastings himself, but none have been proven. The most likely explanation is that Ragnar is indeed entirely legendary, and the tales of many others inspired his story.

A more well-known historical parallel to illustrate the emergence and role of these legendary figures is that of King Arthur. Arthur, most of us will agree, is a myth, and the product of medieval literature more than anything else. And yet, serious efforts have been made over the years to prove that there may have been a real person who inspired the story. Most of these claims stem from Geoffrey of Monmouth’s Historia Regum Britanniae, which mentions a potential candidate—a Roman soldier—whose story may have later inspired Wace, Chrétien de Troyes, and others. Again, the trouble is that none of these links can be confirmed. Furthermore, the story of Arthur we know and love today is the product of the collective imagination of the society in which his story circulated. The same is true of Ragnar and the other legendary figures of the Viking Age.

Semi-Legendary Viking FiguresAs we say in French, “les choses se compliquent” (things get more complicated) when we enter the semi-legendary space. Semi-legendary figures are those who appear in sagas considered more historical (such as the Sagas of the Icelanders), are attested in saga literature and historical sources, have some archaeological support, or a combination of all of these.

Leif Eriksson is a notable example of a semi-legendary figure. He appears in the Sagas of the Greenlanders, which were considered, for many years, to be part fabrication with a kernel of truth from oral storytelling, and then, surprisingly, confirmed, at least in part, by the archaeological find of a Norse settlement in Newfoundland. Now, whether Leif Eriksson existed in the flesh is up for debate—he’s not mentioned in any contemporary sources, nor did he leave us any written testimony of his own. Herein lies one of the issues with Viking figures: they did not write anything down, making the work of historians all the more frustrating.

Undoubtedly, there are people who will argue that Leif Eriksson is a historical figure. The argument is that his name was transmitted through oral tradition. While this is true in many cases, the issue with oral tradition is that, although it occasionally provides us with evidence, it is, on the whole, unreliable. This unreliability is further exacerbated by the fact that those oral traditions were written down by people who did not necessarily practice them. And so we are left with the frustrating middle ground of leaving these historical figures to semi-legend.

Leif Eriksson joins a long list of these figures, including most of the earliest kings and jarls of Viking Age Scandinavia, who are attested in sagas such as the Ynglinga Saga (also known as the Saga of the Yngling Dynasty, or the kings of Norway).

Historical Viking FiguresHistorical figures are those whose existence can be confirmed through contemporary sources. They are those Vikings whose names made it into the annals, diplomas, charters, and cartularies of those people who had the ability and willingness to write down the stories of their deeds in the time that they did them. A single source will not do. As we discussed above, what cannot be confirmed lives in the semi-legendary realm. Historical figures can be confirmed through cross-referencing of sources, with multiple mentions of them within a narrow timeframe and specific geographical location.

That they are historical does not mean they have escaped the tendency of mythmaking by later chroniclers and historians. In fact, many of these figures took on larger-than-life proportions over the twelve centuries since their deeds were recorded. What’s important is that we can confirm their existence through contemporary sources.

My favorite example (because, of course!) is the Viking warlord Hasting (also spelled Hastein, Hastæn, and Alsting). In contemporary sources, he first appears in the Chronicle of Nantes for the year 843, allegedly having assisted the Bretons to defeat the Franks before moving on to sack the city. While the chronicle of Nantes has been questioned for some of its obvious fabrications, the events of that year it describes are confirmed in large part by the Annales d’Agoulême and the Annales de Saint-Bertin.

Later, Hasting reappears in the 860s in a flurry of mentions by the Chronicles of Regino Prüm, confirmed by the Annales de St. Bertin, the Annales de St. Vaast, and a handful of diplomas—including a land grant for Chartres—as a fidelis of King Charles.

Hasting was such an active force of chaos that later medieval historians featured him prominently in their histories. He is a tidal force of nature in the Gesta Normanorum, receiving no fewer than 150 epithets to describe his villainy. In the Gesta Danorum, he joins Bjorn Ironsides on a legendary adventure in the Mediterranean. And perhaps the most curious of these medieval histories is that of Raoul Glaber, who claimed to have worked from contemporary sources now lost to history to put forward a narrative that places Hasting at all the major raids in Nantes, Angers, Orléans, Tours, and even Paris through the 840s, 850s, and 860s. Short of finding the sources he used to verify his claims, his narrative remains in question.

Hasting was a real Viking whose exploits were recorded enough for us to say that he was a historical figure.

Why this mattersThe Viking Age has fallen victim to modern mythmaking to a much greater extent than most other historical periods. This could partly be due to the mythmaking they themselves did, and that their victims later did to them. It’s essential, however, to understand where the line between fact and fiction lies because ignoring it means ignoring the truth you can hold in your hands and opening yourself to believing all sorts of silly ideas. It’s an exercise in critical thinking to look at narratives about the past and to question them, and to put in the effort to understand what’s real and what’s myth. Good critical thinking skills are essential to survive in today’s madhouse of a media landscape, where fact and fiction swirl together like the Tasmanian devil’s tornado.

Writing and PublishingBook Fairs Are Worth It.This past month, I attended three book fairs in a row, first at the Domaine de Roiffé, then at the Salon de Noirmoutier, and most recently at the Chateau de la Flocellière. I was able to learn a great deal about how book fairs work in France, their value to authors, and where they will fit in my ‘author business plan’ moving forward.

Book fairs are great for meeting readers.At the salon de Noirmoutier, I was overjoyed by how many people came just to see me and meet me. In 2019, I gave a lecture to the community about the Vikings and sold some 1,000 copies of the French version of The Lords of the Wind. Many people remembered me and, despite my long absence during and after Covid, still came out to see me again and chat about Vikings, writing, and other things. The support from readers was a big boost to my morale as an author.

Book fairs are great for meeting other authors.The book fair at the Domaine de Roiffé was a dud. A dozen or so people showed up in total, so it was a slow day. Still, I spent the day networking with other authors, learning about their works, inspirations, and goals, and it was a pleasure to start building a community of like-minded people. I had not had many opportunities to meet other authors before, and so this was a delightful part of my book fair experience.

Book fairs are not a great sales channel.I would be remiss if I omitted mentioning that I was disappointed by the sales volume. At each fair, I sold the most books of any other author there (because Vikings sell!!!), but that volume was much lower than I had anticipated. Still, people bought, so it wasn’t a total loss. However, I was forced to reframe book fairs in my author business plan.

But they are great for marketing.Get known. That’s rule #1 of marketing. And these book fairs were not only great for local exposure, but also an opportunity to create content for my online channels. What a privilege it has been to travel through France and visit so many amazing historical sights along the way! I’ve created many videos of my travels, inviting my readers to share in this journey. TikTok seems to be the most interested. If you have a chance, check out my TikTok, Instagram reels, etc, to see the tremendous sights I’ve had the privilege of visiting.

Stay tuned for more book fairs to come. I’ll be at Barbatre end of October, Riantec in November, and Noirmoutier again for the Christmas market in December.

Author UpdateA Viking Tour of Western France, Anyone?I am starting to put together a ‘Viking Tour of Western France’ tour group for summer 2026 and am looking for 20 individuals who are interested. Thanks to some wise advice from fellow author Octavia Randolph, who does tours of Gotland, I plan to bring her same mix of travel, history, and literary intrigue to my region of France. You’ll get to visit these important sites with me as your guide. The goal will be to follow Hasting’s journey (loosely) from Noirmoutier to Paris (books 1-3).

Here is a tentative itinerary of spots we would visit:

Start in Noirmoutier at the castle and the church of St. Philbert (for the crypt).

Go sailing on the Viking ship Olaf D’Olonne in Les Sables D’Olonne.

Visit the 1,200-year-old priory at St. Philbert de Grand Lieu.

Visit the Château de Nantes.

Visit the Cathedral of Nantes.

Learn about Namborg (Viking Nantes) from a local Viking reenactment group.

Visit le Puy du Fou (to explore modern interpretations of the Vikings in France)

Visit the Viking fort in Brittany.

Visit the Viking village in Normandy.

Move inland to Rouen.

End in Paris at the foot of the wall the Vikings climbed in 845 A.D.

If you are interested in joining my waiting list, please email me at author@cjadrien.com to express your interest, and I will add you.

Thank you!

Book RecommendationsThe Oxford Illustrated History of The Vikings

Blurb:

With settlements stretching across a vast expanse and with legends of their exploits extending even farther, the Vikings were the most far-flung and feared people of their time. Yet the archaeological and historical records are so scant that the true nature of Viking civilization remains shrouded in mystery.

In this richly illustrated volume, twelve leading scholars draw on the latest research and archaeological evidence to provide the clearest picture yet of this fabled people. Painting a fascinating portrait of the influences that the “Northmen” had on foreign lands, the contributors trace Viking excursions to the British Islands, Russia, Greenland, and the northern tip of Newfoundland, which the Vikings called “Vinlund.” We meet the great Viking kings: from King Godfred, King of the Danes, who led campaigns against Charlemagne in Saxony, to King Harald Bluetooth, the first of the Christian rulers, who helped unify Scandinavia and introduced a modern infrastructure of bridges and roads. The volume also looks at the day-to-day social life of the Vikings, describing their almost religious reverence for boats and boat-building, and their deep bond with the sea that is still visible in the etymology of such English words as “anchor,” “boat,” “rudder,” and “fishing,” all of which can be traced back to Old Norse roots. But perhaps most importantly, the book goes a long way towards answering the age-old question of who these intriguing people were.

September 24, 2025

The Fell Deeds of Fate is a 2025 Reader's Favorite Awards Winner!

The Fell Deeds of Fate is a 2025 Reader’s Favorite Awards Winner!

The Fell Deeds of Fate is a 2025 Reader’s Favorite Awards Winner!The saga of Hasting the Avenger has reached new heights. The Fell Deeds of Fate, Book IV in C.J. Adrien’s internationally acclaimed Viking series, has officially been named a 2025 Reader’s Favorite Award Winner!

For those unfamiliar, Reader’s Favorite is one of the most respected international book award contests in the industry. With thousands of entries from over a dozen countries each year, their panel of judges—composed of publishing professionals, authors, and avid readers—recognizes the best books across genres. To rise from the sea of competitors and seize victory is no small feat. This is a mark of quality, honor, and recognition that few books earn.

But the glory doesn’t end there. The Fell Deeds of Fate was also highly praised by Kirkus Reviews, one of the most prestigious and notoriously discerning voices in publishing. Kirkus rarely gives high commendation, and when they do, readers know it means the work is something special.

So what makes this novel stand apart? In The Fell Deeds of Fate, the indomitable Viking chieftain Hasting turns his eyes toward Constantinople, the heart of empire, where the clash of swords meets the clash of destinies. It’s a tale of ambition, power, and the peril of chasing immortality—crafted with the grit, blood, and thunder that true Viking sagas demand.

If you crave shield-walls and storm-tossed seas, if you hunger for tales as sharp as a battle-axe and as fierce as Odin’s wrath, then this book belongs in your hands.

⚔️ The Fell Deeds of Fate has claimed its laurels. Now it’s time for you to claim your copy. Join the shield-wall—buy the book today! 👇September 15, 2025

Comment un monastère est devenu une forteresse face aux raids vikings.

Château de Noirmoutier, supposé avoir été construit à la base pour repousser les Vikings.

Château de Noirmoutier, supposé avoir été construit à la base pour repousser les Vikings.La semaine dernière, nous avons étudié l’exemption de péage accordée en 826 par Pépin Ier, un aperçu révélateur de la manière dont la politique royale s’adaptait à la pression croissante de l’activité viking le long de la Loire. Cette exemption montrait clairement qu’au milieu des années 820, les raids scandinaves étaient suffisamment perturbateurs pour justifier d’accorder aux moines de Saint-Philibert un allègement financier. Cela venait s’ajouter à la charte de 819, qui avait donné à l’ordre de Saint-Philibert le droit de construire et de se réfugier chaque année, pendant la saison des raids, dans un prieuré satellite plus en retrait, appelé Déas.

Cette semaine, nous avançons de quelques années, jusqu’en 830, lorsque la situation est passée de concessions fiscales à une tentative de fortification physique. Un diplôme royal daté du 2 août 830 indique que les moines de Saint-Philibert avaient fortifié leur maison insulaire sur Herio et reçu la permission impériale d’y poster des hommes pour garder le castrum. Le même acte rapporte que, malgré cette fortification, la communauté quittait encore l’île chaque été pour se réfugier à Déas. Il souligne même les difficultés de ce déplacement : transporter les biens de l’église était ardu et le service divin cessait sur l’île en leur absence. Une forteresse, une garnison et un départ saisonnier programmé témoignent d’un risque ordinaire et récurrent, et non d’une urgence ponctuelle.

Ce document s’inscrit dans une série d’indices qui décrivent déjà la menace comme répétitive. En 819, l’abbé Arnulf avait obtenu l’autorisation d’utiliser Déas comme refuge face à des incursions fréquentes. Le ton des sources ne se relâche pas dans les années 820. Le prologue des Miracles d’Ermentarius — Ermentarius de Noirmoutier était un moine du IXᵉ siècle et prétendu témoin oculaire de certaines attaques vikings ; il nous a laissé l’une des premières sources narratives dans ses Miracles de Saint Philibert — se plaint des perturbations constantes causées par les Normands, surtout pour les familles liées au service du monastère, et mentionne les habitants des îles fuyant avec leur seigneur. Plus tard, le Livre II situe le comte Renaud d’Herbauge combattant les Vikings tout en défendant le castrum. Que cet affrontement ait eu lieu exactement en 835 ou une année voisine importe peu : il confirme que la forteresse avait été construite pour faire face à un problème durable.

Cet élément est essentiel pour raconter l’histoire de la Loire avant que les grandes annales ne prennent le relais. Le diplôme de 830 implique que la fortification avait déjà eu lieu et que l’évacuation estivale était devenue une habitude. En d’autres termes, la « fréquence et l’intensité » des raids scandinaves mentionnées en 819 ne s’étaient pas atténuées au cours de la décennie suivante. Elles se sont poursuivies durant les années 820 et, en 830, avaient engendré une politique permanente sur Herio : construire, garder et, quand la saison change, partir.

Si les premières parties de cette série s’interrogaient sur le fait de savoir si 799 marquait un début et si le rythme s’était maintenu, cette entrée fournit la preuve administrative. Une charte qui autorise la mise en garnison est une réponse gouvernementale à une menace connue et répétée. Lue parallèlement au témoignage d’Ermentarius et à la mention des combats au fort, l’image est claire : des raids scandinaves réguliers le long de la basse Loire sont déjà attestés avant les notices mieux connues des grandes annales.

Aujourd’hui, en visitant le château de Noirmoutier, les visiteurs découvrent son histoire, notamment comment il fut construit pour repousser les Vikings et reste le plus ancien château de France. Bien que rien ne prouve que le château actuel descende directement du castrum édifié contre les Vikings, une chose est certaine : moins de trois décennies après le début des trois siècles que l’on appellera « l’Âge des Vikings », ces derniers avaient déjà un impact.

L’idée du castrum est un élément central de mes romans. Dans le deuxième tome, À l’ombre de la Bête, mon personnage principal, Hasting, s’empare du castrum et du monastère pour en faire sa base d’opérations dans la région.

Si tu ne veux pas attendre la semaine prochaine pour découvrir la prochaine phase de l’expansion viking dans le royaume carolingien, vis-la dès maintenant dans ma série La Saga d’Hasting le Vengeur, qui culmine avec la bataille épique sur l’île de Noirmoutier entre une armée franque et le plus célèbre chef de guerre viking de tous les temps : Hasting.

Sources (via Cartron, p. 34, n. 12) : Diplôme du 2 août 830 (éd. L. Maître, Cunauld, son prieuré, ses archives, 250–253), avec confirmations dans les Annales Engolismenses (MGH SS XVI, a. 834, 485) et le Chronicon Aquitanicum (MGH SS XVI, a. 830, 252) ; Ermentarius, Miracula I, Prologue ; Miracula II, c. XI.

Si vous ne voulez pas attendre la semaine prochaine pour en savoir plus, plongez-vous dans mon premier roman, Les Seigneurs du Vent, qui culmine avec l’épopée de la bataille de l’île de Noirmoutier entre une armée franque et le plus célèbre chef de guerre viking de tous, Hasting.

Et comme toujours…Achetez mes romans !

Was Noirmoutier Used as a Viking Wintering Base?

Bishop Gohard being slain by Hasting at the sack of Nantes, 843

Bishop Gohard being slain by Hasting at the sack of Nantes, 843It all starts with the entry for the year 843 in The Annals of St. Bertin, which relays to us the sack of Nantes in 843 as follows: “Northmen Pirates attacked Nantes, slew the bishop and many laypeople of both sexes, and sacked the civitas…finally, they landed on a certain island, brought their households over from the mainland and decided to winter there in something like a permanent settlement.”

The fall of Nantes shocked the entire empire, with one chronicle describing it as an apocalypse. Ermentarius relays that they sailed up the Loire with 67 ships, and the Annals of Angoulême suggest they were Vestfaldingi, or men from the Vestfold region of Norway. More intriguing to our purpose here is the mention in the Chronicle of Nantes, which was composed using earlier manuscripts, that directly references the island of Noirmoutier (then called Herio) as a wintering base for the Vikings.

The Annals of St. Bertin, along with the Chronicle of Nantes, seem to confirm Noirmoutier as a Viking base. However, there is an issue. Although the Chronicle of Nantes is recognized as a medieval document, it has been questioned for including later embellishments, such as the mention of Charles the Bald as king of France in 843. Therefore, we must approach its information with great caution. Whether Noirmoutier was used as a wintering base remains uncertain. As a result, we need to consider two other pieces of evidence that, when combined with the Chronicle of Nantes, support the theory.

First, the Annales of Angoulême tell us that a large fire erupted on the island in 846, destroying any settlement there. Several historians see this as evidence of a permanent settlement on the island, which was then destroyed after about ten years. Second, we have a report from a slightly farther source—from Andalusian Spain—by the envoy al-Ghazal, who traveled north with the Vikings who sacked Seville in 844 to learn more about them, as had been agreed with Emir Abdu al-Rhaman. Al-Ghazal describes that the fleet stopped on the French coast to resupply, where the Vikings had built a beautiful, prosperous port town before moving on to what historians believe was Ireland. Again, the island of Noirmoutier is not explicitly mentioned, but given the context of references in the Annals of St. Bertin, the Annals of Angoulême, Ermentaire, and the Chronicle of Nantes, the timing and location of al-Ghazal’s account seem to possibly confirm the base.

Like many aspects of the Viking Age, we can't definitively say that Noirmoutier served as a wintering base based on our current sources. However, we do have one more piece of evidence to add to the puzzle: the later pattern of how the Vikings conducted their raids in the region as they moved inland. Noirmoutier marked the start of over a century of Viking activity in the area. Beginning in the 840s and into the 850s, a clear strategy emerges. The Vikings established wintering bases in the lower Loire River Valley, starting with Nantes in 853, Mont-Glonne in 854, and further upriver in 856 and 866, each location bringing them closer to key targets like Angers, Tours, and Orléans, which they repeatedly sacked. Adrevald, a monk who wrote the Miracles of St. Benoît, notes that the Northmen built cottages as wealthy as a ‘Bourg’ (or wealthy trade town).

The establishment of bases across the Loire River Valley sets a precedent for the strategy used by the Vikings, making the base on Noirmoutier even more believable. If Nantes was their primary target, it makes sense they would have set up a settlement nearby to receive, sort, and ship their loot. However, as their targets moved inland, they shifted their bases accordingly, even using their former target of Nantes as a new base. As the Annals of St. Bertin tell us, in 853, “Danish pirates from Nantes heading further inland brazenly attacked the town of Tours and burned it.”

We have strong indications from the sources that Noirmoutier was used as a wintering base by the Vikings, although a clear ‘smoking gun’ remains elusive. By piecing together various partial mentions and establishing a pattern of behavior consistent with such activity, I believe we can make a solid case for Noirmoutier being a Viking settlement for at least ten years.

The settlement of Noirmoutier, its destruction, and the sack of Nantes are all pivotal events in my series, The Saga of Hasting the Avenger.

Did you enjoy this article?

And, as always…Buy my novels!