Esther Crain's Blog

October 12, 2025

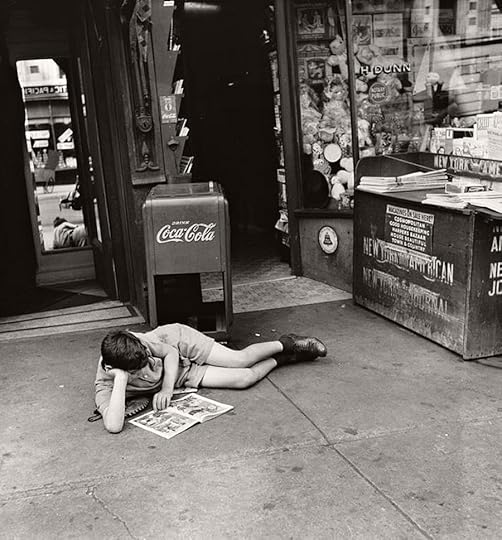

The Upper East Side tailor who took poetic street scene photos over six decades from his shop window

John Albok saw much loss early in his life. Born in Hungary in 1894, he was drafted into war, then returned home to learn that two of his sisters died of starvation and his father had committed suicide.

He may have been able to get through these tragedies by focusing on his passion: photography.

As a 12-year-old, he acquired his first camera, a Kodak Brownie. He took photos during his army years, documenting scenes from prisons and hospitals, according to New York University’s digital library. But his family had no funds to spend on art school. Instead he was apprenticed to a tailor.

In 1921 he immigrated to New York City, opening a tailor shop at 1392 Madison Avenue, between 96th and 97th Streets. Now married, Albok, his wife, and his daughter lived in an upstairs tenement apartment for the next six decades, witnessing waves of demographic change on the border of the Upper East Side and East Harlem.

From his shop, he began taking pictures—turning a compassionate, sensitive eye toward the sidewalks and streets in all seasons outside his front window.

“For 60 years, using a 5 x 7 view camera and then a twin lens reflect camera, Albok took as his subject people and passersby outside his shop, and New York City life during the Depression, and World War II,” per NYU. “Central Park, children, street scenes, and people at leisure were also among his preferred subjects.”

He described his Depression-era photos as a way to combat the degradation of poverty. “I photographed many poor souls, trying my best to leave them their most precious heritage—their dignity,” he said. “There is nothing else left.”

His work as a tailor occupied his days. “At night, he used the small shop as a darkroom to develop his pictures, many of them taken through the shop’s window,” wrote the New York Times.

Albok didn’t only capture images on Madison Avenue. He roamed the city for subjects, sometimes not returning home until early the next morning, much to the consternation of his wife. Labor protests and antiwar activism sparked his interest, as did day-to-day life among the Hungarian immigrant community then concentrated around East 79th Street.

Critical acclaim for his images came in the late 1930s. A curator at the Museum of the City of New York (MCNY) mounted a solo exhibit titled “Faces of the City.”

Through the next decades he had occasional exhibits, published photos in art journals, and was the subject of two documentaries.

Framed photos he had taken also hung from the walls of his shop, “peeking out from behind the garments hanging from the ceiling,” reported the New York Daily News in 1968.

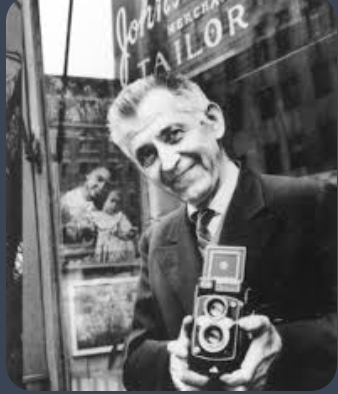

This gentle tailor (at right, in the 1970s) found himself and his work rediscovered in the early 1980s, per NYU.

Another MCNY show, “Tailored Images,” was put together. One day before this retrospective exhibit was to open in 1982, Albok died at age 87.

Albok was still residing in the tenement apartment above the shop that provided a window to the wonder and pathos of New York City life—glimpsed in these and thousands of other poetic images.

In a 1966 Daily News piece, he explained what might sum up his drive to chronicle the humanity in the city: “Wherever there is people there is pictures because there is life.”

[Top image: Monovisions; second image: Artsy; third image: Artsy; fourth and fifth images: Monovisions; sixth image: FAE Collector Blog; seventh image: Invaluable]

The eccentric Hungarian princess who moved into the Plaza Hotel with 12 servants and a lion cub

Imagine walking through Central Park one day and seeing a plump, fashionably dressed woman with her hair in a loose chignon walking a lion cub on a leash, trailed by a squad of servants.

You’d stop and do a double-take, right? Park visitors in early 20th century who came across this lady and her lion cub likely did as well. And some may have recognized her as the European princess now living in Manhattan that many of the city’s dailies were buzzing about.

The princess, Elisabeth Vilma Lwoff-Parlaghy, didn’t just have a royal title. She was a noted painter who in 1909 parked her suitcases, servants, and menagerie of exotic animal pets in a 12-room suite at the new Plaza Hotel on 59th Street and Fifth Avenue.

There she began her colorful Gotham residency as a seemingly wealthy portraitist whose life was an alluring mystery.

The mystery begins with her birth. Most sources say she was born into privilege in Hungary in the 1860s, showed an early talent in art, and studied at the Academy of Arts in Paris.

Others have it that her Jewish family was very poor, and after they scraped together the funds for the daughter they knew as Rebecca to study with a celebrated professor in Budapest, she set up a studio in Berlin and gave herself a new name.

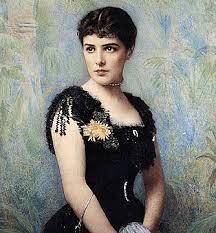

As a young woman in 1890 (self-portrait, above), she painted a portrait of her mother (below), which caught the attention of the European art world and brought her to prominence.

Through the 1890s she painted portraits of Kaiser Wilhelm and other notable European figures, exhibiting them at the Salon de Paris and World Columbian Exposition in Chicago in 1893.

She made her first trip to New York City three years later, where she entranced Gotham’s art world, society, and the New York Times.

A fawning Times profile described her “big, vigorous brush strokes,” the jealous sneers “this gifted young woman” has received from fellow artists, and—in a moment of accidental foreshadowing—her love of horses and dogs, of which she “possesses half a dozen of the finest sort.”

In 1899, Princess Vilma earned her title by marrying Russian Prince George Eugeny Lwoff (left).

“The union lasted just a few years,” states Atlas Obscura, “but Princess Lwoff-Parlaghy managed to retained her royal title—and much of her royal riches—post-divorce.”

In 1908, she returned to the States, temporarily settling in Hot Springs, Virginia and visiting Washington and Philadelphia.

But her sights were set on New York. So her staff sent letters to the city’s poshest hotels (which at the time were more like apartment buildings, with many full-time guests) seeking accommodations for “her highness” that included “auxiliary footmen” and a gold-trimmed Victoria, per the New York Times.

Her staff also requested a suite with room not just for the princess’s small dog but “a pet bear, (six months old and well trained), an ibis, and a young alligator,” wrote the Times. “These pets are from the palace of her Highness in Nice, and in case of damage her Highness is prepared to defray all expenses, although damage is unlikely.”

Reportedly turned down by the Waldorf-Astoria, the princess found rooms for her retinue at the year-old Plaza, a French Renaissance newcomer to the city’s luxury hotel scene.

By now, her entourage included 12 servants and another alligator, an owl, an angora cat, and a guinea pig. “As explained by her first secretary yesterday, she dearly loves animals, despises people who are not kind to them, and insists upon the motto: love me, love my dog,” per a New York Times article in 1908, before she moved into the Plaza.

Her plan was to paint the portraits of great living Americans. Over the years, she accomplished this, with Thomas Edison, Theodore Roosevelt, and August Belmont among her sitters. But not long after settling in the city, she tried to buy a lion cub from the Ringling Brothers Circus.

Told the cub was not for sale, she had Civil War General Daniel E. Sickles buy it for her. Sickles recently sat for a portrait, and her reasoning was that the Circus wouldn’t turn down such a celebrated American—which they didn’t.

The cub, named Goldfleck, went on leashed walks through Central Park and reportedly lived in the suite bathtub. Goldfleck even accompanied the Princess when she went back to Nice for visits.

Sadly, Goldfleck passed away in 1912. A funeral was held for him at the Plaza, and the now full-grown lion was interred at the pet cemetery in Hartsdale, New York.

Meanwhile, newspaper writers documented her comings and goings. She continued painting, scoring the only portrait of Nikola Tesla, who sat for her in 1916 (above).

It wasn’t long, however, before her unpaid bills at the Plaza (above) caught up with her, and she was asked to leave. Her paintings “were held as security for the unpaid bill,” wrote the New York Times. “But she was permitted to take with her a pet bear, an alligator, an ibis, two falcons, two pet dogs and two Angora cats, which made up her pet menagerie.”

Next stop for the princess was a townhouse at 109 East 39th Street. She decorated as if it were an art museum (displaying mysteriously acquired van Dycks, Rubens, and Rembrandts), entertained lavishly, and kept up the mystery of where her funds were coming from—as World War I spelled the end of her ex-husband’s riches, per Atlas Obscura.

She died “destitute” in her townhouse in 1923, according to the New York Times, with just two servants remaining of the dozen who previously catered to her. Her funeral took place at her home as well as the Greek Orthodox Church on West 54th Street, where an open casket displayed the Princess wearing a blue and gold robe and a silver crown. Today she rests in Woodlawn Cemetery.

“Death spared her seeing the most cherished objects of her household sold at public auction,’ wrote the New York Times in her obituary.

In a city always teeming with characters, Princess Vilma found a home for herself and her beloved menagerie. Entitled, eccentric, and with a true talent for portraiture, her theatrical life amused New Yorkers of the era—and she took many mysteries with her to the grave.

[Images 1-4, Wikipedia; fifth image: natachaivaldi.com; sixth image: Pixels.com; seventh image: MCNY 93.1.3.1529; eighth image: Alamy]

October 6, 2025

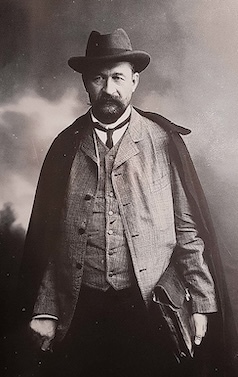

The tenement is a menace to all, according to a dark and blunt illustration from 1901

There’s no mistaking the message of this darkly graphic illustration, which appeared in the satirical periodical Puck in March 1901.

“The tenement—a menace to all,” the tagline says. Death hovers over the triumphant spirits of alcoholism, prostitution, gambling, opium dens, and other social evils, which escape like noxious vapors through the unlit tenement windows.

Its publication was just a few weeks before New York State adopted the Tenement House Act of 1901. Otherwise known as the “new law,” this legislation mandated at least one window in every room in a tenement apartment, as well as a separate bathroom in each unit, as opposed to a hall bathroom or outhouse in the back of the building.

Did the new law vanquish the unsafe and unsanitary conditions in tenements across the city, which two-thirds of all New Yorkers at the turn of the 20th century called home? Definitely not, especially since many landlords simply ignored the new rules.

But the possibility of air flow into all the rooms in an apartment and availability of hygienic and private bathroom facilities were victories hailed by the progressive reformers of the era.

[Source: The Ohio State University/LOC]

Unhappily married to a UK royal, this Gilded Age dollar princess became the great-grandmother of Princess Diana

Mansions, equipages, Parisian ball gowns, box seats at the Academy of Music—top-tier Gilded Age families had access to the finest material luxuries, thanks to their deep pockets and social influence in post-Civil War New York.

Yet one luxury some Gilded Age elites desired was much harder to come by: a family connection to royalty.

America had no aristocracy, of course. But Europe did. And many lesser dukes, earls, counts, and barons in England and across the continent were finding it difficult to maintain their expensive lifestyles and ancient estates while watching their funds dwindle in poor economic conditions.

So emerged the “dollar princesses.” These marriage-age daughters of posh American families were typically pressured into tying the knot not for love but status.

Their family would arrange a dowry of sorts for the intended husband who needed the cash infusion. In turn, his new wife would gain an aristocratic title—and her social-climbing relations became linked to nobility.

One of the earliest dollar princesses was Jennie Jerome (below left), the 19-year-old daughter of “King of Wall Street” Leonard Jerome. Jennie married Lord Randolph Churchill in 1874. (She gave birth to their son Winston seven months later.)

Perhaps the best known dollar princess was Consuelo Vanderbilt (below right), who was strong-armed by her mother, Alva, into giving up the American suitor she loved and accepting a proposal in 1894 from Charles Spencer-Churchill, aka the 9th Duke of Marlborough—a man she met on a visit to England when she was 17.

“We reached a stage where arguments were futile, and I left her then in the cold dawn of morning feeling as if all my youth had been drained away,” Consuelo recalled in a final confrontation with her manipulative mother at their Newport mansion in her 1953 autobiography, The Glitter and the Gold.

Both Jennie and Consuelo’s marriages were marred by infidelities and the transactional nature of the relationships. Consuelo cried the morning of her wedding, noting that she was 20 minutes late to the ceremony at St. Thomas Church because she had so many tears to wipe away under her veil.

The stories of these two high-profile dollar princesses have been retold over the years, with Consuelo currently serving as the inspiration for Gladys Russell in HBO’s The Gilded Age show.

But there’s a lesser-known dollar princess from New York City who also married an aristocrat from the UK. It was an unhappy union as well. But the marriage produced a descendent first known as Lady Diana Spencer and then Princess Diana, the modern world’s most famous princess.

The dollar princess’s name was Frances Ellen Work (top image and at left). Born in the fashionable Madison Square neighborhood in 1857, Fanny was the daughter of a Midwesterner who earned his fortune as Cornelius Vanderbilt’s personal stockbroker, according to American Aristocracy.

Fanny grew up at 13 East 26th Street, on the northern end of Madison Square Park. Bright and fluent in French, she summered in Newport and made the rounds of social events in New York City.

“She was also headstrong, so when the handsome James Burke Roche—the son of an Irish Lord with empty pockets but ladles of charm—proposed, she ignored her father’s angry remonstrations and married him anyway,” notes American Aristocracy.

Fanny’s father may not have been pleased by the nuptials; he reportedly cut his daughter’s allowance to $7,000 per year. (Not a bad sum in the 1880s.) Yet he did pay off her husband-to-be’s $50,000 in gambling debts.

But she had the support of her grandmother, according to a writeup in History Collection, who wanted her “exceptionally beautiful” granddaughter to “run in the most prestigious social circles of them all: British nobility.”

The marriage took place at Christ Church in September 1880. Two daughters and twin sons were born to the couple, and Fanny’s father once again paid off his son-in-law’s gambling debts, which now amounted to $100,000. By 1886, Fanny Burke Roche had enough. She fled to New York and filed for divorce, claiming desertion.

The divorce was messy, thanks to custody disputes and the fact that American divorces were not valid in England at the time. Fanny married again in 1905 at the Empire Hotel, this time to her Hungarian-born driving instructor. That marriage also ended in divorce a few years later.

When her father died in 1911, Fanny inherited a portion of his $14 million fortune. For the rest of her life, she entertained at her apartment at 1020 Fifth Avenue (below ad from the 1920s) and in her Newport mansion. She also visited various European destinations.

“Mrs. Burke Roche, during her later years, divided her time between this country and Europe, visiting her son, Lord Fermoy, who in addition to the title, inherited an estate of 20,000 acres at Rockbarton, County Limerick, Ireland, and a seat in the British Parliament,” reported the New York Times in Fanny’s 1947 obituary, which stated that she died in her apartment at the age of 90.

Here’s where the Princess Diana connection comes in. The son she visited in Ireland, Lord Fermoy, aka Edmund Maurice Burke Roche (above right), had a daughter named Frances Ruth Roche.

This daughter grew up to marry John Spencer, and the two became parents to four children—including Princess Diana in 1961.

Diana was born into the British aristocracy, and she hailed from a long line of UK nobles. But her connection to Gotham’s Gilded Age through a beautiful and independent-minded great-grandmother (who is also great-great-grandmother to William and Harry, and great-great-great grandmother to their children) adds a historical New York angle to her compelling life story.

[Top photo: American Aristocracy; second photo: American Aristocracy; third photo: Wikipedia; fourth photo: Wikipedia; fifth photo: American Aristocracy; sixth image: Wikipedia; seventh image: American Aristocracy (Frances Ellen Work) and Getty Images via Oprah Daily (Princess Diana)]

September 29, 2025

A ghostly old house on the edge of the Hudson River, and the boxer who lived there with his family

Before Riverside Park, before Riverside Drive, before the sparsely populated Manhattan district known since the 18th century as Bloomingdale was urbanized into the Upper West Side, there was a lone modest house.

Perched on the edge of the Hudson River in the West 80s, the two-story, pitched-roof dwelling appears to have no neighbors. A back porch faces the tracks of the Hudson River Railroad and the expansive waterfront; a front entrance opens to hilly, rocky land.

Outside are some of the residents, presumably—an adult or older child, a young kid or two, and a flock of chickens.

The scenes in the above photo—taken in 1884, as well as the one below from 1875—look like they depict bucolic upstate New York rather than Gilded Age Gotham.

But this really is Manhattan, and the farmhouse-style dwelling likely dates to the earlier 19th century—when Bloomingdale was a collection of family estates and working farms on hundreds of acres and chickens, gardens, and a barn would fit in perfectly.

Who lived in this house, and what was life like here at a time when the hallmarks of urban development—townhouses, elevated trains, graded streets, thousands of new faces—were rapidly encroaching? Here’s what we can piece together.

In the late 19th century, this was the home of Luke Welsh. Known as a “sporting man,” Welsh was an Irish-born boxer who came to the city in 1863 as part of a group of six athletes nicknamed the “Irish giants,” as they were all over six feet tall (Welsh was six-foot-two, per the New York Times.)

Boxing was mostly illegal in 19th century New York unless the match took place at an athletic club. Newspapers describe Welsh and other “sporting celebrities” attending fights at downtown clubs or sparring in front of raucous crowds. One account at the Bowery Theatre in 1868 reported that Welsh’s opponent “danced around Luke like a cooper round a keg.”

Welsh moved on from boxing in the 1870s and became part of the Tammany Hall political machine. He held positions as a sergeant-at-arms as well as a messenger. What these titles mean isn’t clear. But he had status, and his salary as a messenger earned him $1,200 a year—a fine sum in an era when a laborer’s yearly wage could have been as low as $300.

Though he lived in the house with his wife and four kids, Welsh turned part of his home into a saloon, reported an 1879 article, and he also had a boathouse by the 1880s.

The yard was the site of popular clambakes “on the lawn for the judges and politicians, with the chef carefully adding a magnum of champagne to each ten-gallon copper pot of chowder,” wrote Peter Salwen in his 1989 book, Upper West Side Story.

Day-to-day life had a rural feel. Welsh’s son James later recalled “a long family tradition of the children and visiting cousins planting trees nearby…cherries, apples, peaches, and plums came from trees on the property,” stated Salwen. James also said that “a mess of fish” would “be caught before breakfast by the younger boys for the morning meal before going to school.” (Map above, Bloomingdale in 1870, without the park of Drive)

Meanwhile, Bloomingdale was in transition. The new Riverside Park began welcoming visitors in the 1870s; Riverside Drive, then called Riverside Avenue, opened in 1880. Bloomingdale’s farmhouses, estate houses, and many shack dwellings for poor New Yorkers pushed to the margins were being replaced by mansions and townhouses. (Below, in 1889)

How did these transformations affect Welsh? I wish I knew. When he died in 1903 at the age of 65, The Evening World noted that this boxer-turned-politico “died yesterday at his home, No. 1534 West 83rd Street, from a complication of diseases.”

There is no 1534 West 83rd Street. Could his home have had a made-up house number to satisfy the requirements of living in the urbanized city? A death notice in the New York Times gives his address as 153 West 83rd Street. This is a stable (now a garage), which doesn’t seem right for a man who served the Tammany regime and later took a position with the steamboat police.

If it hadn’t been demolished before his death, the modest wood and brick house almost certainly went down soon after. Just as the Upper West Side as we know it today was making its debut.

For more on the houses and histories of 18th and 19th century Riverside Drive, check out one of Ephemeral New York’s Riverside Drive Gilded Age walking tours. The next tour dates are Sunday, October 12 at 1 p.m. and Sunday, October 19 at 1 p.m. Click the link for more info and to sign on!

[Top image: MCNY, X2010.11.6192; second image: MCNY, X2010.11.3084; third image: NYPL Digital Collections; fourth image: MCNY, X2010.11.3105B]

September 28, 2025

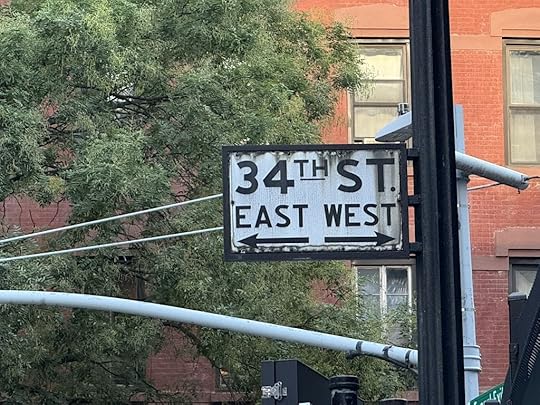

The oldest street sign still functioning in New York City might be this one in Murray Hill

New York City street signs are a study in evolution—from street names on the sides of buildings to pole-mounted square directionals to the rectangular green and white reflective signs we see on corners today.

But as thousands of city street signs were updated and replaced many times over the years, one 1940s-era sign on a side street in Murray Hill survives in the contemporary city.

It’s affixed to a street light at the end of an exit road on the Manhattan side of the Queens-Midtown Tunnel. The exit road brings traffic to 34th Street—and this simple relic directs drivers toward their eastward or westward destination.

How did the 34th Street sign manage to hang on? Because it’s on an exit road, it was likely missed by the Department of Transportation (DOT), which handles street sign maintenance and upkeep.

It’s hard to know exactly when the sign went up. White on black signs became the preferred style in the 1930s, according to a post from the Bklyner blog. The tunnel wasn’t completed until 1940, which means the 34th Street sign could have been placed on the exit road in that decade.

The sign isn’t just a relic; it’s also a rebel. It doesn’t conform to the green and white standard, nor does it meet 2010 guidelines from the Federal Highway Administration that street signs contain capital and lowercase letters in Clearview typeface, per the Cooper-Hewitt Museum.

But as a forgotten artifact of another New York City, let’s hope it stays in place—especially since the DOT has replaced other left-behind street signs, like the yellow and black 1960s-1970s sign on Union Square West at the bottom of this post.

Brooklyn also has—or had?—some old-school signs, like this one south of Prospect Park and another in Fort Greene. Hopefully they’re still with us.

September 22, 2025

What a 1912 painting might be saying about the changing social rules of New York’s public spaces

Any number of scenarios could be playing out in “At the Claremont.” It’s a rich and evocative nocturne featuring three women, one man, a table top of tea cups and bottles, and the twinkling lights of the Hudson River and New Jersey Palisades outside large picture windows.

The two rosy-cheeked women could be vying for the romantic attention of the handsome man in the tuxedo. These well-dressed women keep their distance across the wide table, but their extended hands suggest an invitation.

His arm on the table blocking his body, however, seems like a defensive move. Maybe he has an eye on the woman almost out of view behind him?

We might be viewing a fix-up between the man and the woman in the foreground. The woman with her back turned to the restaurant window could be the one playing cupid, pleased by the possibility of a match.

Or maybe all three are taking advantage of the romantic nighttime view to feel out the possibilities of pleasure later in the night. They’re at the Claremont Inn—an early 19th century roadside tavern north of Grant’s Tomb that by the turn of the century transitioned into a relatively pricey spot for dignitaries and businessmen. But a lavish meal doesn’t seem to be on the menu.

A closer look at the background of the painter might offer some clues. Ida Sedgwick Proper (at right) was born in Iowa in 1873. She made her first trip to New York in the late 1890s to attend the Art Students League.

After studying in Europe, she returned to Manhattan in 1905. In addition to creating art and exhibiting her work, she devoted herself to the suffrage movement and was a founding member of Heterodoxy—a group of 40 prominent women that met regularly at the Greenwich Village Inn on Sheridan Square to discuss issues in an appropriately bohemian setting.

Perhaps “At the Claremont” was simply Proper’s way of marking the shifting of social mores. The era of gendered public spaces began ceasing in the early 1900s. Both sexes were more free to mix in cafes and other venues—which would have shocked previous generations that accepted the social separation of men and (unchaperoned) women as a cultural norm.

Setting the painting at the Claremont Inn suits the situation. When it was a tavern, women were unlikely to be allowed inside. In the modern New York City of 1912, women dominate the venue.

[Top image: Artsy; second image: Wikipedia]

A Gilded Age sugar baron and his wife build a Fifth Avenue “house of fantasy” for their family and art collection

The house itself, a Romanesque Revival mansion completed in 1893 that spread across the northeast corner of 66th Street and Fifth Avenue like an open book, was sober and restrained.

Compared to Caroline and John Jacob Astor IV’s fantastical French Renaissance chateau one block south, as well as the many other gaudy showpieces lining the Gilded Age’s millionaire mile, it had an air of unobtrusive understatement.

But the rough-stone facade and turreted bays belied an interior so extraordinary, it made the house not just a family mansion but also a landmark of decoration filled with masterfully placed art and antiquities from all over the world.

The husband and wife who built this “house of fantasy,” as one newspaper retrospective called it, were not only fabulously wealthy but also well-known in business, political, and social circles of the 19th and early 20th centuries: Henry O. and Louisine Havemeyer.

Henry Havemeyer—known as Harry—was the heir to a family sugar dynasty that operated a refinery along the East River in South Williamsburg. Hence Williamsburg’s Havemeyer Street, which may have been named for the sugary refinery or possibly for William Frederick Havemeyer, a relative who served three stints as New York’s mayor in the 19th century.

Starting as a teenage apprentice in the 1850s, Harry learned all about the business, from the secrets of sugar boiling to finance. Eventually he became one of the leaders of what was then called Havemeyer & Elder.

His work ethic and competitive nature helped Havemeyer & Elder corner the extremely competitive post–Civil War sugar market and make the East River waterfront the top sugar refining location in the nation. The company built a state-of-the-art refinery on the same spot in the 1880s, ran afoul of anti-trust laws, and in 1901 introduced a new name, Domino—which maintained a presence in Williamsburg until 2004.

While Harry was a fierce businessman, he also enjoyed what seemed to be a fulfilling home life. Louisine, his second wife (above, with daughter Electra in an 1895 portrait by Mary Cassatt), was the daughter of his former business partner George W. Elder.

Later in life, Louisine would become known as a feminist and suffrage supporter who was arrested outside the White House during a 1919 march. But as a 19-year-old student on an extended trip to Paris with her family, she was introduced to painter Mary Cassatt—who became a pivotal figure.

“When we first met in Paris, [Cassatt] was very kind to me, showing me the splendid things in the great city, making them still more splendid by opening my eyes to see their beauty through her own knowledge and appreciation,” recalled Louisiane in her autobiography, via the Shelburne Museum website.

“With Cassatt’s tasteful eye and tap on the pulse of the Parisian art world, she guided Mrs. Havemeyer during their initial meetings to purchase modern art—works by Edgar Degas (1834-1917), Edouard Manet (1832-1883), and Cassatt herself—which would inform her, and later, her husband’s collecting interests,” states the Shelburne museum.

Harry and Louisine married in 1883, had three children, and spent the rest of their lives collaborating as art collectors. Harry had already purchased items on his own, such as carved ivory figures, Japanese lacquered boxes, and sword guards. Louisine continued her interest in scooping up the work of French Impressionists.

Eventually their collection included “nearly 2,000 Egyptian, Greek and Roman, Asian, Islamic and European paintings, sculptures, drawings, prints, and decorative objects,” wrote Michael Kimmelman in the New York Times in 1993.

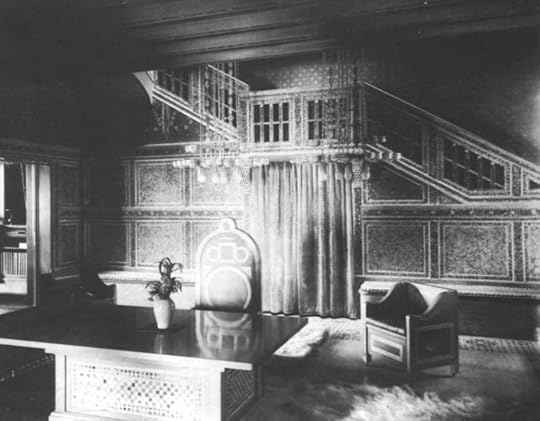

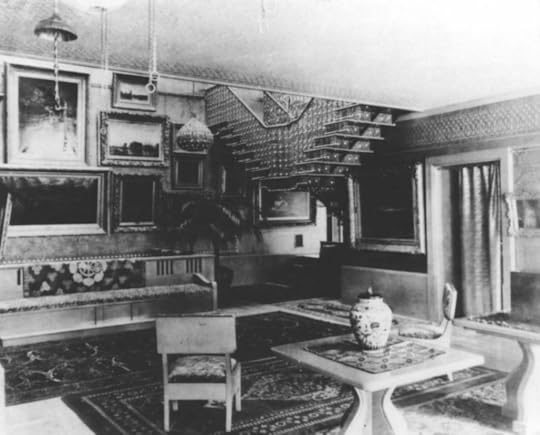

As their collection grew, they needed a mansion with the proper light and grandeur to display their holdings. The commission to design the house went to architect Charles Coolidge Haight. For the interiors, they turned to the design firm run by Louis Comfort Tiffany and Samuel Colman.

“While Colman supervised the decorative schemas, Tiffany saw to the fabrication of opulent decorative elements that resembled giant pieces of jewelry,” states the University of Michigan Art Museum website.

“Every component of the eclectic interior décor pushed the limits of decorative design by merging principles of jewelry design, mosaic art, sculpture, metalwork, and textile and furniture design,” the Michigan museum continued. “Not one square inch was neglected; no surface was left untouched.”

What Tiffany and Colman created was a sumptuous work of art in itself. Visitors would go through the metal and opalescent front doors and find themselves in the main entrance hall (fifth image), with a glass mosaic-faced staircase and a frieze of “individual mosaic panels that repeated a motif of Islamic character,” states Alice Cooney Frelinghuysen in Splendid Legacy: the Havemeyer Collection.

The library was known as the Rembrandt room (above), as it held the couple’s collection of Dutch pictures. Colman designed the furniture; the lighting fixture above the desk may be the first extant Tiffany chandelier, suggests Frelinghuysen, who was a family descendant by marriage.

Perhaps the most imaginative feature in the house could be found in the second-floor picture gallery: a “flying” staircase. “The spectacular staircase was suspended, like a necklace, from one side of the balcony to the other,” wrote art and architectural critic Aline Saarinen, as quoted in Splendid Legacy.

Also inventive in Louisine’s second-floor bedroom (below) overlooking Fifth Avenue was Tiffany’s use of “what seem to be two long printing blocks, possibly Indian and perhaps for textiles, adorn the headboard and footboard for the bed,” wrote Frelinghuysen.

It would not have been unusual for wealthy mansion dwellers to have art galleries in their homes. But because of their extensive collection and vision for how to display it, in partnership with Tiffany and Colman, the Havemeyers created a harmonious, enchanting, and spectacular space that received international attention.

Even after Harry passed away in 1907, Louisine continued collecting. Following her death in 1929, much of the couple’s holdings were bequeathed to the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Some went to the Shelburne Museum in Vermont, which was co-founded in 1947 by youngest daughter and art collector in her own right Electra Havemeyer Webb.

And the mansion itself? This fortress of art and antiquities went to the three children, who had the magnificent interiors broken up, sold off (some artifacts went to the University of Michigan Museum of Art), and the house demolished. Its replacement is an 18-story co-op completed in 1949.

A final relic of the Havemeyer fortune still stands in Williamsburg. The Domino sugar refinery is part of a complex rebranded Domino Park that includes the facade of the old brick refinery—an eerie ghost of one of the many riverfront industries that powered the fortunes made during the Gilded Age.

[Top image: MCNY, 93.1.1.18063; second image: New York Historical; third image: Wikipedia; fourth image: Findagrave.com; images 5-8: Splendid Legacy: the Havemeyer Collection by Alice Cooney Frelinghuysen; ninth image: MCNY, X2010.7.1.4758]

September 15, 2025

The enchanting stained glass luring drinkers into one of Midtown’s dwindling workingman’s taverns

Deep roots anchor P.J. Clarke’s, the restaurant and bar occupying a Civil War–era brick building with its top two floors sheered off at Third Avenue and 55th Street.

Converted into a tavern in 1884 when Irish laborers held a large presence in the developing neighborhood, the building was bought by Irish immigrant Patrick “Paddy” J. Clarke in 1912.

Clarke had been one of the saloon’s bartenders, and upon taking ownership, he decided to put his own name above the entrance. Little did he know his name would remain in place for more than a century.

Clarke lived above his bar, and four of his sons were born upstairs, according to the P.J. Clarke website. He kept the beer cold with the help of 200 pounds of ice; modern refrigeration didn’t get installed until the 1980s.

Prohibition threatened to put him out of business, but the establishment survived by selling bathtub gin and bootlegged Scotch from Canada, per the website.

After Paddy Clarke passed away, his heirs sold the saloon in 1947. (Below photo, the bar in 1940.) The new owners, the Lavezzo family, came in just as this neck of Third Avenue would undergo major changes.

The Third Avenue Elevated that ran beside the bar was taken down in 1955. Many of the surrounding tenements also got the boot in the name of development, and towering office buildings and apartment houses rose on all sides.

But P.J. Clarke’s endured as the business changed hands again. These days, corporate workers, locals, tourists, and celebrities all revel in the back-in-time feel of the turn of the century mahogany bar, the pressed tin ceiling, and the vintage wooden phone booth, now used by the wait staff.

To my eyes, the most enchanting historical relic of P.J. Clarke’s is the beveled stained glass on the corner of the building. There’s more stained glass inside, true, and the colored light against the dark wood interior is lovely.

But the glass on the facade has a magic to it. Illuminated by the late afternoon sky and the soft amber globes decorating the windows, it gives off a feeling of secrecy and privacy—luring thirsty New Yorkers into the warm embrace of a late 19th century workingman’s tavern.

[Third image: NYC Department of Records & Information Services]

Inside the Gilded Age childhoods of six clever siblings raised in “zany confusion” on Riverside Drive

On the facade of a magnificent mansion at Riverside Drive and 89th Street, six young siblings are immortalized in marble.

With innocent faces and pensive expressions, the four girls and two boys in bas relief above the mansion’s porte cochere are all engaged in learning. One is reading, another examines some kind of machinery, a third holds his hand to his head as if working through a math equation.

Who are these studious kids? Meet Muriel, Dorothy, Isaac Jr., Marion, Marjorie, and Julian Rice—otherwise known to their doting parents as Dolly, Polly, Tommy, Molly, Lolly and the Baby, aka Babe.

Born in the 1880s and 1890s, they are the six children of Isaac Leopold and Julia Barnett Rice, who built “Villa Julia” between 1901- 1903 (third image) as a refuge where they could enjoy the pleasures of domestic life and use their wealth and resources to raise their brood in a highly unorthodox way.

In an era in which families still abided by the centuries-old “children should be seen and not heard” adage, the Rices were determined to treat each child as an individual and nurture their natural curiosity, passions, and interests.

“Dolly, Polly, Tommy, Molly, Lolly, and Babe were, in the words of the New York Sun, the ‘children who never hear don’t,'” stated a 2013 New Yorker article referencing the family.

Isaac and Julia themselves were quite accomplished. A Bavarian immigrant, Isaac was a musician, editor of a literary journal, and an elite chess player—the “Rice gambit” was named for him. He made his fortune as a lawyer reorganizing various railroads and as an investor in companies pioneering the use of electricity.

Julia Barnett Rice (below) was equally gifted. This formidable woman hailed from New Orleans and came to New York to earn a medical degree, one of the few women of the era who did so. After she and Isaac married in 1885, Julia assumed the traditional role of the “moral center” of her household and was responsible for the day-to-day bringing up of the kids.

“She has sought to be her children’s companion, chum, and mentor,’ the New York Sun reported in a feature on Julia Rice in 1907. “She endeavors to restrain neither their tastes nor their thoughts, nor does she force their actions, but she aims to guide and advise.”

So what was it like to grow up with two highly intelligent, deeply unconventional parents in a household described as a “zany confusion of opulent hotels, transatlantic voyages, revolving tutors, harried servants, and disbelieving neighbors,” according to one publication?

In many ways, they were like other kids. “The Rice children played music,” noted the New Yorker in 2013. “They kept a menagerie of cats and dogs. They ran around a gymnasium on the fourth floor.” The constant uproar forced Isaac Rice to build a solid rock vault in the basement where he could play chess in peace.

Julia also retreated to this soundproof room, as she was driven to sleeplessness not by her kids but by the tugboat horns tooting at all hours of the day and night on the Hudson River. The din that comes with riverfront living led her to establish the Society for the Suppression of Unnecessary Noise, which made her a well-known figure in early 20th century New York.

Their bedrooms took a turn toward the unusual. Rather than rooms furnished to reflect a parent’s taste, which would have been the convention in the Gilded Age, “each one of the Rice children has a separate room and in it each is free to do as he or she pleases,” noted the Sun, adding that Julia would never enter any of her children’s rooms without permission, as it infringed on their independence.

“Ten-year-old Baby’s room “is decorated with more than 2,000 pictures of automobiles…not only are the walls covered with them but the ceiling as well,” wrote the Sun. Older brother Tommy’s room was adorned with images of steam engines.

As for education, Isaac and Julia seemed to eschew the traditional path of a private school or finishing school. When one of the children expressed an interest in a field of study or hobby, tutors were quickly found.

From an early age, “every one of the kids chose a lifestyle,” explained a cousin in a 1975 Sports Illustrated article. “Each was enormously intelligent and curious, and the father was willing to underwrite just about any interest any of them came up with. One had a seven-day bicycle racer for a tutor; another a three-cushion billiard player.”

When oldest daughter Dolly (below) showed a talent for writing poetry, Isaac Rice founded the Poetry Society of America. After second daughter Polly (above, sixth image) took an interest in motorcycle racing, Isaac built her a garage. Polly later took up painting, and among her teachers were Robert Henri, she told the New York Times in a 1940 article.

Molly, the fourth of the six siblings, developed a passion for engineering, and after three months of intensive tutoring likely arranged by her parents, she entered Barnard College and then graduated from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Their unconventional childhoods included yearly trips abroad to Europe, where they would stay for months at a time, engaging with family friends like the king of Spain, Madame Curie, and Pope Pius X. “We were so taken with him,” said sister Dorothy in the Sports Illustrated article, “that we all wanted to become cardinals.”

In 1907, an economic recession forced Isaac Rice to sell Villa Julia. But the family maintained their lifestyle by relocating to a 22-room apartment at the Hotel Ansonia on Broadway and 73rd Street (below, in 1906). To further Dolly’s literary talents, Isaac set up a regular salon in the apartment’s ballroom and invited noted writers like Theodore Dreiser, per Sports Illustrated.

By the time Isaac Rice died in 1915 and Julia in 1929, their children were adults. What became of them, and how do they remember their privileged, atypical childhoods?

Muriel “Dolly” Rice published a book of poems in 1906 and passed away in 1926. Dorothy “Polly” Rice made a name for herself as the first girl in New York City to ride a motorcycle (and got arrested along with brother Tommy for speeding down Broadway), became a pilot, then teamed up with her second husband, Hal Sims, to form a celebrated bridge team.

Isaac L. Rice, Jr., aka Tommy Rice, eloped with a Riverside Drive neighbor in 1915; he appears to have become a director of an electric boat company, which reflects his father’s business interest. Julian “Baby” Rice may have gone into law, another of his father’s professions. Marjorie “Lolly” Rice became a playwright.

Perhaps the boldest Rice child was Molly—or Marion, the name she went by through her illustrious adult life (at right). After becoming the first woman to graduate MIT with a chemical engineering degree in 1913, she worked as a physicist and a geologist, then took up painting and sculpture and moved to France.

Divorced and bored with the artistic life, Marion Rice Hart bought a yacht, became a captain, and sailed around the world. In her 50s she fell in love with flying and spent the rest of her life as a pilot. In 1975, Sports Illustrated became aware of this 83-year-old aviator and commissioned a profile.

In it, she referenced her upbringing. “I was brought up to believe what you did mattered, not what you didn’t,” she explained. “I am doing today what I have always done, which is what I want to do. There’s nothing unusual about that.”

Marion, the last of the Rice children, died at age 98 in 1990. All six siblings are gone, but their sweet faces and curious personalities are evident in the bas relief in front of their Riverside Drive childhood home.

This faded sculpture combines two things most important to Isaac and Julia Rice: family love and the pursuit of knowledge.

The Rice mansion is part of Ephemeral New York’s Riverside Drive Gilded Age walking tour—the next tour date is Sunday, September 21 at 1 p.m. Find out more about the Rice family and the hidden history of the Drive by signing up here!

[Second image: alchetron.com; third image: MCNY, X2010.7.2.25109; fourth image; NYPL Digital Collections; sixth image: Wikipedia; seventh image: Poems by Muriel Rice; eighth image: Shorpy]