Alix Christie's Blog

August 21, 2025

How the Printing Press Changed Education in Europe

Back in the 1400s, when the printing press invention showed up, things kind of flipped for folks wanting to learn. Before all this fancy machinery, education was this really closed-off thing. Mostly monks and rich people got their hands on those old handwritten books—imagine copying all that out by candlelight! The big change? When Gutenberg and his printing press idea came along, suddenly learning wasn’t some exclusive club. Books spread everywhere and classrooms didn’t look the same after that.

Wider Access to BooksIf you ever wondered what changed overnight, it’s how many books you’d find once the first printing press got rolling. No kidding, the way schools and libraries exploded with books must have blown people’s minds. Instead of twenty students passing around one battered copy, everyone could finally hold their own book. Easier studying, more chance to look something up yourself—if you think about it, that’s a pretty big deal.

Growth of Literacy RatesThe whole reading game shifted too. All of a sudden, regular people saw books written in words they used every day. Here’s where you get part of the answer for why was the printing press important: it let loads of folks start reading—didn’t matter if they were kings or street vendors. Being able to read wasn’t some rare skill for the rich; now it mattered to everyone. Funny how fast that changes a place, right?

Standardization of KnowledgeHandwritten stuff came with plenty of mistakes, so before all this, one book could give you different facts from another. But since the printing press invention, you had pages turning out nearly identical across cities. Science texts, class notes—everything lined up better. If you had a teacher over in Paris using the same math book as someone in Venice, chances are you’d both be working off the same formulas. Makes sharing ideas a whole lot easier, if you ask me.

Expansion of Universities and SchoolsOnce books stopped being so expensive, universities grew like crazy. New spots for learning popped up because it wasn’t such an ordeal to put textbooks into students’ hands. The whole structure of education leaned way harder on what you could actually read, instead of just listening to someone talk. Pretty soon you’ve got experts popping up in law, medicine—you name it—all because people could riff off printed material. Kind of wild how that builds up, isn’t it?

The Role in Cultural and Intellectual MovementsThis tool changed way more than schoolwork. Thanks to the printing press, all kinds of movements took off—the Renaissance, the Reformation… those ideas wouldn’t have traveled the same if everything still needed scribes. Folks could pick up the latest Greek or Roman writer from their local printer and dig into stuff nobody talked about before. That sparkly attitude that pushed people to ask questions started sneaking into class conversations too, not only parroting info for exams.

Lasting Legacy on European EducationTake a minute and ask who made the printing press, or even track down when was the printing press invented, and you’re right smack in the middle of the story behind modern schooling. What Gutenberg did wasn’t build just another contraption—he started something where everyone from scholars to farm kids could dream bigger about what they might learn.

The ripples from that very first machine keep showing up today—you grab a textbook, hop online to check research, whatever. It all goes back to having a simple way to share writing. The real takeaway? Tools like the printing press don’t just help swap stories—they shape what we know, and even push us forward, generation after generation.

The post How the Printing Press Changed Education in Europe appeared first on The Gutenberg Bible.

February 10, 2018

Tower of Discord

The Gutenberg Museum in Mainz – “The World Museum of Printing” – is truly an unmissable destination for any lover of the history of print. I’ve spent untold hours there in the exhibition rooms and library, learning not only about Gutenberg and his world but the entire history of the technology of writing. So it was with some surprise that I recently read that in this celebratory year of Gutenberg 2018—five hundred fifty years after his death—the museum dedicated to the great inventor is in the midst of a raging controversy.

The Gutenberg Museum in Mainz – “The World Museum of Printing” – is truly an unmissable destination for any lover of the history of print. I’ve spent untold hours there in the exhibition rooms and library, learning not only about Gutenberg and his world but the entire history of the technology of writing. So it was with some surprise that I recently read that in this celebratory year of Gutenberg 2018—five hundred fifty years after his death—the museum dedicated to the great inventor is in the midst of a raging controversy.

A proposal to renovate the aging museum and turn it into a international showpiece has met stiff resistance from many citizens of Mainz, who will decide in a referendum in April whether the project should go forward.

At the center of the controversy is a new “Bible Tower” (Bibelturm) made of a lace of giant letters that would serve as entryway to the refurbished museum, adding new gallery space above and underground. The design won an architectural competition and reminds me a bit of a cross between the new tower at Tate Modern in London and the Pyramid at the Louvre in Paris—which similarly functions as an architectural doorway to the museum complex.

You can see the renderings and photos of the proposed building here. The citizens group opposing the move fears it will dwarf the historic medieval plaza of the Liebfrauenplatz, and worry about how it will be financed. Without wishing to enter the debate, I would say however that it is high time the museum got a facelift—not only architecturally but in terms of presenting its treasures. The displays are dated and old-fashioned and do not do justice to the remarkable collection of incunabula and printing technology that the museum has to share with the world.

Anyone who appreciates the tremendous history of the book and early printing has Mainz’s Gutenberg Museum on his or her bucket list. Here’s hoping that the town of Gutenberg’s birth finds a way to bring his epochal achievement into the modern age.

Article on the controversy in German here:

The post Tower of Discord appeared first on Gutenberg's Apprentice.

August 29, 2017

Books in Art: documenta 14 in Kassel

I just returned from Kassel, Germany, where the documenta contemporary art exhibition takes place every five years. What struck me after two days of wandering around was how many books there are in the art being made now. Real books. Physical books. Ledgers and notebooks and written documentation of every kind.

I just returned from Kassel, Germany, where the documenta contemporary art exhibition takes place every five years. What struck me after two days of wandering around was how many books there are in the art being made now. Real books. Physical books. Ledgers and notebooks and written documentation of every kind.

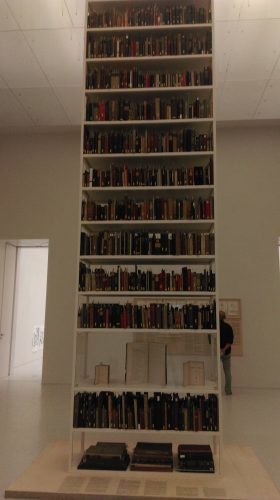

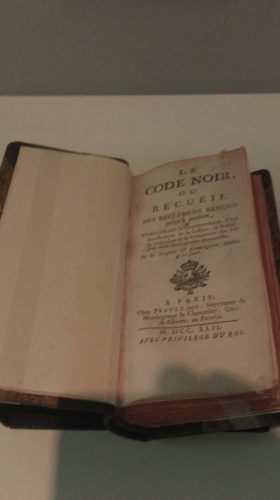

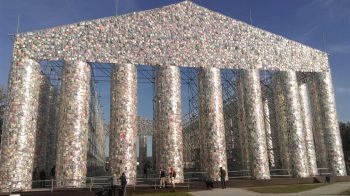

We’re all fairly done with the idea that the electronic book was going to replace the physical object that has been around for two thousand years. Still it was interesting to see the degree to which artists rely on this modest vessel. At this very political documenta, “the book” appears in many guises: as reminder of atrocities past, the persistence of ideologies, shorthand for the life of the mind, a locus for self-expression. And so on. The huge centerpiece of the show is “The Parthenon of Books” by the Argentinian Marta Minujin, in which thousands of books previously banned or restricted by governments aound the world are encased in plastic to create a replica of the Acropolis’s main building. So far, so obvious. A more interesting exhibit, to me, is the vast “Rose Valland Institute” by the German artist Maria Eichhorn (tall bookcase photo) which is a huge research project attempting to inventory all of the personal property, books and libraries included, expropriated from Germany’s Jews by the Nazis. (It’s named for a German art historian who secretly listed expropriated property during the Nazi occupation of Paris www.rosevallandinstitut.org).

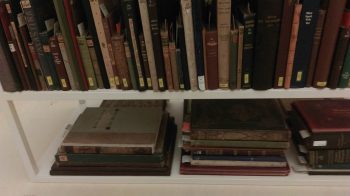

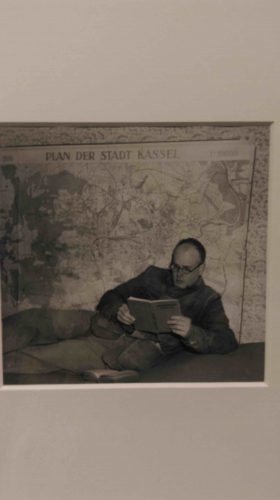

One mixed media exhibit by Daniel Garcia Andujar featured all kinds of references to the horror of war, including stereoscopic images of war damage (pictured), the artist lounging reading a—book (pictured) and a copy of Bertold Brecht’s Kriegsfibel (War Bible) along with a puzzle made from Picasso’s Guernica, among others. Another horrifying exemplar was Louis XIV’s 1742 guide defining the conditions of enslaving black people in French imperial colonies (pictured). It is considered “the most monstrous legal document of modern times.”

And then, in a break from the dreadful past, scattered throughout the show are individual volumes as objects, similar to those one might see in a contemporary fine book show. One book featured delicately stitched pages; a group of others were fashioned from bread dough. There was even a “wall” in the “Neue Galerie” which was made on site from books and mortar at the fourth documenta in 1977: the “Door to the Library” by Huburtus Gojowczyk (pictured).

While this documenta (the 14th) explicitly addresses questions of migration, refugee flows, economic justice and other pressing political issues, these exhibits to me suggested more. They underscored how verbal is much of the art being made today. As these examples show, many artists are interested in documenting processes—of exploitation, democratic resistance and so on. Conveying such complex human exchanges, it seems, requires words as much as images. Vive la parole, one might say: Long live the word.

The post Books in Art: documenta 14 in Kassel appeared first on Gutenberg's Apprentice.

May 16, 2017

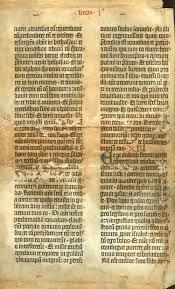

A library as old as the Bible it holds

Out of the 49 complete or partial copies of the Gutenberg Bible known to humanity, only one is the property of a high school library. Granted, Eton College is not just any high school. It was founded by King Henry VI in 1440, a convenient punt ride across the Thames from Windsor Castle. This also explains how a secondary school — rather than a university or private, state or national library–came to own one of the first major printed books in the West. When you are one of Britain’s leading schools for the ruling elite, chances are you will have a number of rather important, rich and, luckily for us, bibliophilic alumni.

Out of the 49 complete or partial copies of the Gutenberg Bible known to humanity, only one is the property of a high school library. Granted, Eton College is not just any high school. It was founded by King Henry VI in 1440, a convenient punt ride across the Thames from Windsor Castle. This also explains how a secondary school — rather than a university or private, state or national library–came to own one of the first major printed books in the West. When you are one of Britain’s leading schools for the ruling elite, chances are you will have a number of rather important, rich and, luckily for us, bibliophilic alumni.

As the story goes, in the early 1830s, an Old Etonian named John Fuller, who also happened to be a Member of Parliament from Sussex, was thinking of donating something to his old school. “Do you have a Gutenberg Bible?” he is said to have inquired. Answered in the negative, he promptly bequeathed Eton the copy he had purchased from a British bookseller named Payne, who in turn purchased it at the sale of the Countess d’Yve in Brussels in 1819.

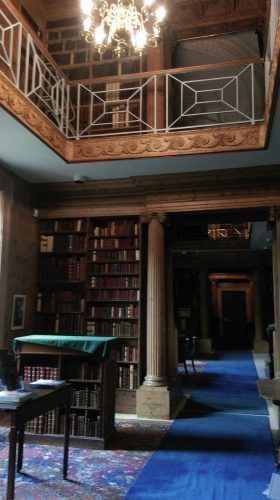

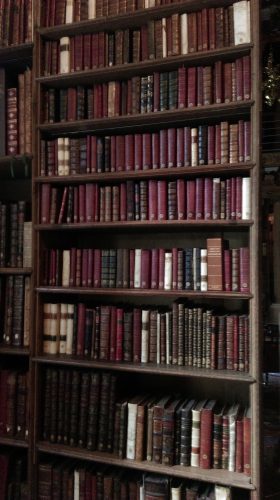

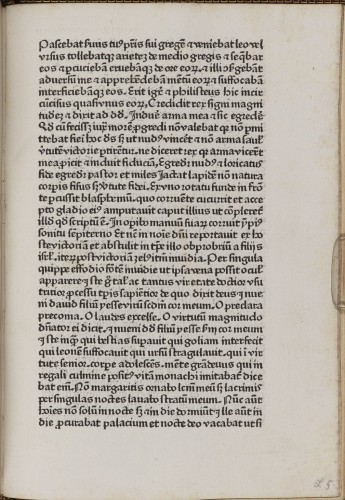

This paper (not vellum) copy of Gutenberg, Fust and Schöffer’s masterpiece was originally purchased by the Carthusian monastery in Erfurt, which as readers of my novel will know, was the seat of the great university at which both Gutenberg and Schöffer studied. It likely came onto the European market after the monasteries were seized by Napoleon. I was lucky enough to see it last week at Eton’s gorgeous 18th century library, which contains the Eton College Collections of rare books and manuscripts. The collection boasts about 200 books printed before 1500 (incunabula), including a whole bookcase full of Aldines (the classics printed in Venice by Aldus Manutius, pictured below). Stephanie Coane, assistant librarian for early books, had both volumes of the Bible waiting for my inspection. It was remarkable, I said, to be looking at a book that was made at virtually the same time that the school was founded. (In 1440, the inventor Gutenberg was hard at work on getting moveable type to work at his orchard workshop outside Strasbourg. All 180 or so copies were produced and sold by 1454, scholars think.)

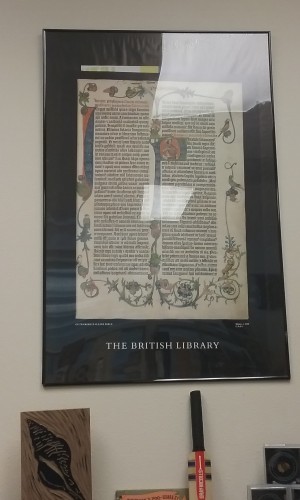

This copy also boasts the only known original binding with original binders’ mark, by one Johannes Fogel of Erfurt; though the spine is cracking, it has held up well; it also has tipped-in tabs the monks presumably stuck on to indicate the starts of different Biblical books. The illuminations feature curling leaves and vines supporting different birds. Though I couldn’t photograph it for you, the paintings resemble the copy in the British Library which my British publisher reproduced on its edition of “Gutenberg’s Apprentice” (pictured). Ms Coane knows her birds: on the opening of Genesis and Jerome’s Prologue she identified a goldfinch, blue and great tits and a jay. The boys at Eton get to see this magnificent thing at least once in their tenure at the school (though they are liable to think it has something to do with Hindenberg or Battenberg). It’s also on display during regularly scheduled open days, so find a teenager and bring him in tow. I flew on my way, after stroking the pages and posing for this photo, aware of how lucky I am to be allowed to touch these 560-year-old pages.

The post A library as old as the Bible it holds appeared first on Gutenberg's Apprentice.

December 29, 2016

Printers, printers everywhere

In my wanderings I’m fortunate to come in contact with many practitioners of the dark arts. (No, this is not a reference to Harry Potter, but the worldwide confraternity of ink-stained printers.) Recently I was invited to tour the extraordinary department of Graphic Communications at the California Polytechnic State University, better known as Cal Poly, in San Luis Obispo, California. The students who take printing and design production classes under department chair Ken Macro and associate professor Brian Lawler (the fellow pictured in these fuzzy photos) are lucky indeed. The department boasts the most astonishing array of printing technology under one roof that I have seen.

In my wanderings I’m fortunate to come in contact with many practitioners of the dark arts. (No, this is not a reference to Harry Potter, but the worldwide confraternity of ink-stained printers.) Recently I was invited to tour the extraordinary department of Graphic Communications at the California Polytechnic State University, better known as Cal Poly, in San Luis Obispo, California. The students who take printing and design production classes under department chair Ken Macro and associate professor Brian Lawler (the fellow pictured in these fuzzy photos) are lucky indeed. The department boasts the most astonishing array of printing technology under one roof that I have seen.

They don’t just have the largest graphic arts library in the world, but one of almost every kind of old and new printing machine, from the heaviest cast iron to the shiniest high tech. Mr Lawler’s tour of the facilities included glimpses of sturdy 20th century machines for foil stamping and die-cutting, a machine for making perfect bindings, a mammoth Heidelberg Speedmaster four-color press than can pump out 15,000 impressions per hour, the world’s fanciest and most expensive exacto knife (AKA an ESKO computer-driven cutter that costs more than most of us make in a year). Then there are the photopolymer plate makers, the rotogravure machine that is apparently only economical for runs of a million or more, and the amazing four-color Flexo printing machine that employs those polymer plates. Every student learns how to run and maintain all of these state-of-the-art monsters, some of which are loaned (rather cleverly) by the manufacturers. This means that from time to time, the very latest model replaces the one on the floor–and the graduates of this program, whether designing packaging or digital user interfaces, or learning to operate and manage complex printing processes, easily find great jobs.

Amazed as I was by all this modernity, my heart really belonged to the basement floor, where 19 working letterpresses are housed in the “Shakespeare Press Museum.” It’s not a museum so much as a working shop, with 500 fonts of type and everything from an 1850 Washington Hand Press to several Little Pilots and a behemoth newspaper press (the Campbell Country Cylinder Press) once used to print the Soledad weekly. There’s even a working Linotype machine, that remarkable invention of Ottmar Mergenthaler inspired by the Jacquard looms that prefigured the punch cards of early modern computing. (All together now: Farewell Etaion Shrdlu!) And naturally, as befits all printing establishments, there is a framed facsimile of a leaf from the first major book ever printed, our own personal favorite, the Gutenberg (Schoeffer-Fust) Bible!

The post Printers, printers everywhere appeared first on Gutenberg's Apprentice.

November 14, 2016

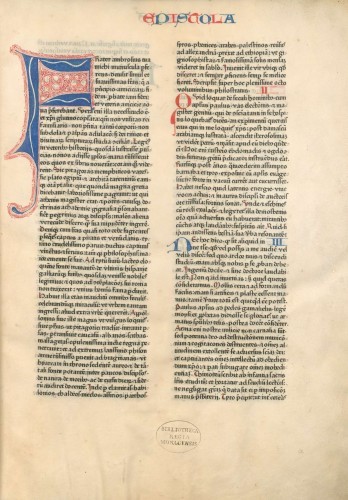

Some Very Big Books

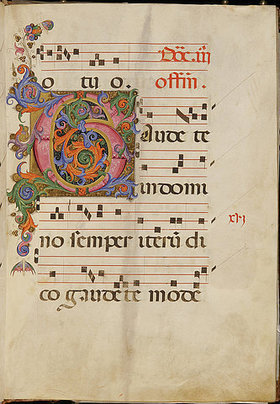

It’s always amazing to me to consider what was going on at the same time that Gutenberg was developing his system of moveable type and bringing in Fust and Schoeffer to help him fund and execute his big idea. Recently I was in Florence, and had the opportunity to visit the San Marco Monastery, which in addition to having the most dazzling paintings by Fra Angelico, also happens to have one of the world’s most beautiful libraries. It’s mostly a museum space now, displaying some of the incredible manuscript choir-books used by the monks. When you hear publishers nowadays talk about “big books” you might instead consider one like this.

It’s always amazing to me to consider what was going on at the same time that Gutenberg was developing his system of moveable type and bringing in Fust and Schoeffer to help him fund and execute his big idea. Recently I was in Florence, and had the opportunity to visit the San Marco Monastery, which in addition to having the most dazzling paintings by Fra Angelico, also happens to have one of the world’s most beautiful libraries. It’s mostly a museum space now, displaying some of the incredible manuscript choir-books used by the monks. When you hear publishers nowadays talk about “big books” you might instead consider one like this.

It’s a “Gradual”, lettered in 1451-1452 by two of the monastery’s monks. 1451-1452–the very same year that, in Mainz, the Gutenberg workshop was beginning work on the monumental printed Vulgate Bible. I wanted to show you the size of it, along with the side view of the massive brass bosses that protected the cover in an original 15th century binding. The midpoint of the 15th century was a big year, it seems: it’s also the date the architect Michelozzo built the library itself for Cosimo de’ Medici, who had a cell of his own in the monastery upstairs. The artist-scribes for several of these large choir books were Zanobi Strozzi, a famous pupil of Fra Angelico, and Filippo di Matteo Torelli. Here’s an open page from a different book to show you how sumptuous and impressive they were inside, as well as out.

The post Some Very Big Books appeared first on Gutenberg's Apprentice.

May 23, 2016

The art of punch-cutting

Here’s a remarkable video posted recently on Vimeo: the exceptional skill required to carve a steel punch that creates a matrix into which molten type metal can be poured to make a letter.

Here’s a remarkable video posted recently on Vimeo: the exceptional skill required to carve a steel punch that creates a matrix into which molten type metal can be poured to make a letter.

The post The art of punch-cutting appeared first on Gutenberg's Apprentice.

December 15, 2015

The Gift of Apprenticeship–a Christmas tribute

I remember with searing clarity the day I printed a thousand envelopes with the wrong zip code in Yolla Bolly red. It was my trial week in a fine letterpress shop in a remote California valley. The master printer bellowed, and I cried. I had hoped to become the Yolla Bolly Press’s first apprentice, but for a while it looked like I would be the last.

I remember with searing clarity the day I printed a thousand envelopes with the wrong zip code in Yolla Bolly red. It was my trial week in a fine letterpress shop in a remote California valley. The master printer bellowed, and I cried. I had hoped to become the Yolla Bolly Press’s first apprentice, but for a while it looked like I would be the last.

Jim Robertson was a hard-charging, passionate master of his craft who ruled his shop with an iron fist and an exacting eye. When after all he took me on, I spent the first weeks cutting paper and distributing type back in its case, terrified that I’d screw up. He was a damned “feinschmecker,” he conceded later with a grin. The term, a blend of fussbudget and connoisseur, reflects the fact that printing, to be truly fine, requires utmost precision. The secret to Yolla Bolly’s gorgeous books was obsessive attention to detail, from design to execution. Each page was carefully composed in shape and size; each line of type was justified, inked, and impressed exactly right.

Les Lloyd, my first master, was the complete opposite. My grandfather was a renowned San Francisco typographer who started teaching me the ‘dark art’ in my teens. An extraordinary man who designed books with Ansel Adams, the Grabhorn brothers, and other California luminaries, he was modest and self-effacing. He ran the largest hot type foundry on the West Coast,Mackenzie & Harris, and printed in his little hobby shop in his spare time. We printed together in his suburban garage; he didn’t rant when I wasted sheets or dumped a tray of type onto the floor, a mess called “printers’ pie”. He only laughed and told me to start over.

His method was gentle, patient: he printed for the love of it, to please himself. He passed to me the heritage that he himself received, leaving school at 16 to become a printer and lifelong member of the club of Printing House Craftsmen. I remember feeling deeply honored on the day that he saluted me in public as his apprentice.

I dedicated my first novel, the story of the Gutenberg Bible, to both these long-gone, much-loved masters. And over the many years of my different apprenticeships — in printing and in novel-writing, and in life — I’ve come to see the fundamental lesson they imparted. True mastery requires both kinds of training: perfectionism, if not sheer obsession, and abiding patience.

We live in a world of instaneity: our culture celebrates the teenaged millionaire, the overnight success. Yet all of our crafts, our wild, inventive human skill with tools, are based on something slower and much deeper. The path to skill in any art requires a long and painful journey. Despite our bits and bytes, this truth still holds. It took seven years in the medieval guilds: a period of apprenticeship, before the journeyman set out upon his wander years. This slow learning, to my mind, is like the movement called “slow food”. Its chief components are time and close instruction, which engage the mind and body in a way no massive open online course can do.

Every Friday for two years, my grandfather and I printed at his Red Squirrel Press. We made books and pamphlets and ephemera; he showed me secrets of the trade, from tissue paper packing tricks to letterspacing. We pored over books made by Leonard Baskin and Frederic Goudy; he described the Monotype caster, the Linotype, the San Francisco fine presses that descended from the English artisans at the great Kelmscott and Doves presses.

This was the first half of the gift of apprenticeship: preserving mankind’s store of knowledge, which the printing press had first made possible. Les was not just a mentor, standing in for the parent as the master did, “in loco parentis.” He was a living link transmitting our cultural heritage, embedded in brain and heart through the act of making at his side.

The second value of this kind of learning is the method the apprentice learns. In his marvelous treatise “The Craftsman,” the philosopher Richard Sennett defines craftsmanship as doing a job well for its own sake. There are no short cuts: “the craftsman must be patient, eschewing quick fixes.” The goal is to embed skill in the body, to make this knowledge tacit, so that the mind and hands are freed to play and push the tools beyond their given purpose. Aristotle noted the same thing centuries ago: “We are what we repeatedly do. Excellence, then, is not an act, but a habit.”

It’s fashionable now to talk of the 10,000 hours it takes to achieve mastery in a field. But what this misses is what happens in those hours. Rote repetition is a waste of time; the learning comes from failure, and then self-correction. The feeling is a sense of not-quite-there that every artist knows. A humbling occurs, a willingness to dwell in this discomfort. “The patience of a craftsman can thus be defined as the temporary suspension of the desire for closure, “ Sennett writes.

I think of Jim’s stubborn feinschmeckery, the high standard he set for the printed word, which he called “the playing field of the human imagination.” I think of Les’s gnarled fingers setting half of Moby Dick in his retirement, his speed and expertise amazing the next generation. I see now how their gifts of patience and precision have informed my own apprenticeship in the allied craft of writing, which has taken me far longer than the seven years prescribed by any guild.

In craft, we are absorbed; we enter the material, lose the murky overlay of ego. Monastic scribes believed that this rapt state made of their bodies a pure channel for God’s word. In modern terms, what I’ve been taught — through trial and error, failure and rejection and success — is that the craft of making has its own time, and that excellence cannot be rushed or forced.

When Jim died, too young, I spoke at his memorial. The Robertsons built books from the inside out, I said — starting with the words, the human spirit they conveyed. Decades before I knew anything about Gutenberg, I eulogized “that great handing-on, bringing a new generation forward steeped in the craft, lore and love of the letterpress.”

As Les lay dying, I worked against the clock to finish our last book, his memoir of the heyday of hot type. He waited as I printed the title page on his old platen press, and had a sample volume bound. I placed it in his hands; he whispered thanks. The torch was passed. The next day he was gone.

The post The Gift of Apprenticeship–a Christmas tribute appeared first on Gutenberg's Apprentice.

November 6, 2015

El Discípulo de Gutenberg — presentation in Barcelona Nov. 16th

I’m delighted to announce that I have been invited by the Barcelona city libraries to inaugurate a new branch dedicated to the history of the book. On Monday, 16 November at 7 pm, I’ll be interviewed by the cultural editor of La Vanguardia, Sergio Vila-Sanjuán. If you are in the city, please come!

I’m delighted to announce that I have been invited by the Barcelona city libraries to inaugurate a new branch dedicated to the history of the book. On Monday, 16 November at 7 pm, I’ll be interviewed by the cultural editor of La Vanguardia, Sergio Vila-Sanjuán. If you are in the city, please come!

The post El Discípulo de Gutenberg — presentation in Barcelona Nov. 16th appeared first on Gutenberg's Apprentice.

November 4, 2015

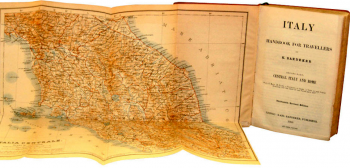

The original foldout book and other wonders

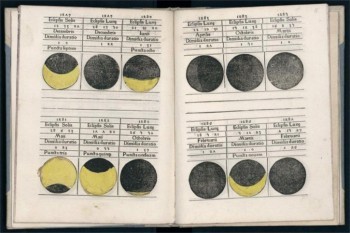

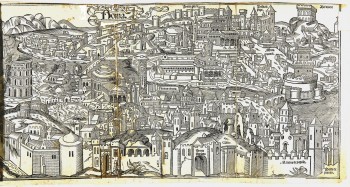

The birthday in 1801 of Karl Baedeker just passed, and the literary website LitHub noted the occasion by publishing a photo of the foldout maps that were seen as an innovation when Baedeker’s celebrated guidebooks first appeared. I chuckled, since last week I enjoyed the enormous privilege of visiting the rare book collection at Harvard’s Houghton Library, where I carefully unfolded the world’s actual first printed foldout maps. In the 1480s, a canon of the Mainz cathedral chapter, Bernard Breydenbach, set out on a pilgrimage to the Holy Land, and Erhart Reuwich illustrated and printed his account, replete with fabulous foldout maps. Five hundred years later they are a bit scuffed and torn, but still open to three or four times the width of the book–pieced together, a true feat of early pressmanship and binding. The images themselves, cut in wood (above left, Rome) are incredibly gorgeous.

The birthday in 1801 of Karl Baedeker just passed, and the literary website LitHub noted the occasion by publishing a photo of the foldout maps that were seen as an innovation when Baedeker’s celebrated guidebooks first appeared. I chuckled, since last week I enjoyed the enormous privilege of visiting the rare book collection at Harvard’s Houghton Library, where I carefully unfolded the world’s actual first printed foldout maps. In the 1480s, a canon of the Mainz cathedral chapter, Bernard Breydenbach, set out on a pilgrimage to the Holy Land, and Erhart Reuwich illustrated and printed his account, replete with fabulous foldout maps. Five hundred years later they are a bit scuffed and torn, but still open to three or four times the width of the book–pieced together, a true feat of early pressmanship and binding. The images themselves, cut in wood (above left, Rome) are incredibly gorgeous.

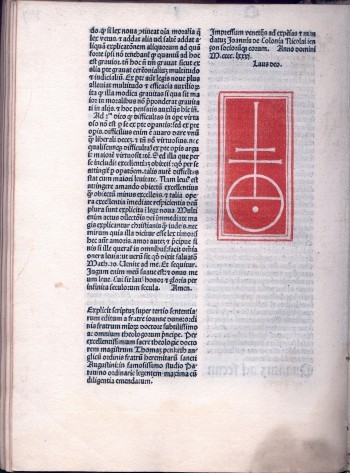

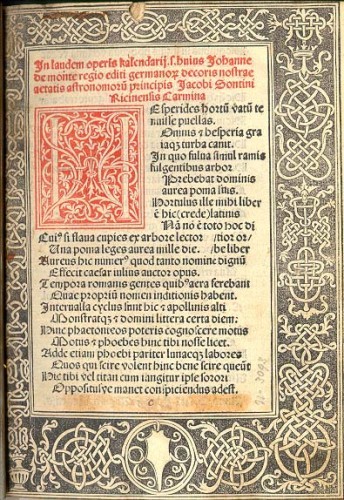

I had never laid eyes–or fingers–on many of the greatest works of early printing which I researched as I was learning about the life of Peter Schoeffer. So with the kind assistance of John Overholt, a curator at the Houghton, I spent a blissful Cambridge afternoon immersed in the smell and touch of 500-year-old paper and vellum. I marveled at the beauty of Nicholas Jenson’s red printer’s mark, reproduced below, on an edition of Duns Scotus; at the pounding impression used by Ulrich Zell in Cologne just a few decades after the invention by Gutenberg and crew; and at the exquisite workmanship of Regiomontanus’s 1482 calendar printed by Erhard Ratdolt in Venice, with its amazing waxing and waning moons. Perhaps the most special, though, was a single leaf from the 36-line Bible, which Gutenberg is believed to have had printed by Heinrich Keffer for the Bishop of Bamberg after the 42-line “Gutenberg” bible. I got a little dizzy, too, turning the four pages that Harvard owns of the 1462 Vulgate Bible printed by Schoeffer and Fust — these were the actual pages they set and printed.

Book people have as much to love in the Boston area as we do in London. I was especially impressed by the Boston Athenaeum, where I gave a talk on the making of the Gutenberg Bible. Atop Beacon Hill, it’s a gorgeous building filled with gorgeous books, a membership temple to the book much like my beloved London Library. Curator Stanley Cushing trotted me through it, stopping with understandable pride at George Washington’s own set of the first American encyclopedia. Truly, books are more than containers for texts. Libraries are the temples where our world is preserved. Volume by volume, the printers of the past encoded the cultural DNA of our species.

John Duns Scotus, Scriptum super tertio sententiarum (Venice, 1481)

The post The original foldout book and other wonders appeared first on Gutenberg's Apprentice.