Alex George's Blog

June 4, 2017

The Book Thief by Markus Zusak

This was one of those books that are unique in the way they are presented, with a unique author’s voice, but one that fails to thrill. I think the relatively high ratings are due to sympathy votes since the topic is centred on German children and families that do not espouse Hitler’s cause and who are forced to hide their true feelings about the Swastika and Nazi propaganda. Basically we follow the life of Liesel Melinger who meets the face of death from the onset, having lost her father and brother from a young age. Her adopted parents soon earn her love and she discovers that they are folks that truly know how to love and to distinguish right from wrong even if this means opposing the tide and making enemies of their neighbours. Markus describes the horrors of war quite well through the eyes of Death who is also a main character in the novel, which gives a unique perspective to the story. I think this novel was not written to entertain or enthral but to make a point, to show how futile, selfish, egotistic and wrong Hitler’s war on the world was. And it also paints the treatment of the Jewish nation in a unique grey colour showing how, when brainwashed, man can reach new beastly lows.

For the message being carried across, though it has been hammered into us by many other authors, I would have given a 5 star. But, since this is not only a rating about content but reader’s enjoyment, I am forced to lower the rating to 3.4 stars. I’m sure these messages have been pushed across by other authors in a more talented and engrossing manner.

May 14, 2017

David Copperfield by Charles Dickens

This book follows so many parallel tales and goes off at so many tangents that at times I found myself struggling to keep my interest going. It meanders too much. HOWEVER, when Dickens sticks to his main character, the story is as absorbing as ever and, needless to say, Dickens remains one of my favourite classics writers. Characters are developed fully, we feel drawn in by their vicissitudes, we learn to love the lovable characters and hate the villains passionately. If I were to rank the novels I have read by this great writer, they would be in this order:

GREAT EXPECTATIONS 5 STARS

OLIVER TWIST 5 STARS

DAVID COPPERFIELD 4 STARS

This tale centres on a young boy who grows up in a home where he is showered with love, loses his father very early, and remains with his mother and baby-sitter until strife enters their family circle. His mother remarries—a most unfavourable, strict, and cruel man who is supported by an equally detestable sister. David’s mother dies of grief, and David is very much left to fend for himself. Fortunately, David decides to run away from home and seeks the aid of his strict (but, as it turns out, lovable) aunt. Dickens travels the reader around the districts of London and then finally has his protagonist earning fame as a successful writer. As with previous novels by Dickens, this one has a few chapters devoted to the main character being schooled at a strict Boys’ School.

David meets love in the face of a child-like woman named Dora. They live well enough for a few years until the fragile wife dies. The novel meanders between the story of David and the trials and tribulations of his closest friends. Eventually, all wrongs are set to right, the villain is placed in jail, and David finally realises that his childhood sweetheart, his ‘sister’ Agnes, is the love of his life and he marries her.

Had Dickens concentrated solely on David and Agnes’s story, and had he made this novel at least 100 pages shorter, this novel would certainly have received my 5 star rating like his other two novels I have read. Even so, at times, it was a delightful and satisfying read.

May 5, 2017

Jane Eyre by Charlotte Bronte

Perhaps not as powerful or memorable a work as Emily’s ‘Wuthering Heights’, however, Charlotte’s story of Jane Eyre has a feel good factor more or less throughout the story with us feeling comfortable that our main character is able to take care of herself and overcome all obstacles. This, to my mind, is a classic tale of Beauty and the Beast, where our little Jane meets with ‘her Master’ as she likes to call her former employer and lover, Mr Rochester.

This is very much a tale of hardship, of an orphan that suffers at Lowood Charity School until better days arrive. Bronte paints the dreary atmosphere of the school with a precision and talent that only one that has gone through the same experiences in life can achieve. Our heroine, Jane, upon graduating and becoming a teacher sets off on her life journey, falls in love, is brought before a horrific dilemma, is forced to abandon her new abode to seek her fortunes elsewhere.

Saved from the brink of starvation, Jane inadvertently meets up with her long lost relatives—the Eyres. In the sisters, Maria and Diana, she is lavished with sisterly love, though the brother, a hard-line Christian, brings her before very tough decisions which will surely destroy her spirit and eventually ravish her small frame and lead it ultimately to death.

But, Bronte, ever a true romantic, has her heroine unite once more with her one true love under the most mysterious of circumstances, and the pair becomes entwined never to be separated again.

I enjoyed Charlotte’s work and would love to read more of her novels, and will endeavour to do so soon.

April 28, 2017

The Count of Monte Cristo by Alexandre Dumas

When I read The Three Musketeers all those years ago, I remember I could not put the book down until I had reached the end of D’Artagnan’s vicissitudes. And I thought, surely this is Dumas’ greatest work and cannot possibly be exceeded. ‘The Count of Monte Cristo’ comes very close to that superb work. I have a special soft spot for the musketeer book, however, I was very pleasantly surprised by the Cristo novel. Firstly, it’s not a novel for the faint hearted: 1276 pages long, and not one of those pages could I have lived without. There’s so much going on during this story: stories within the story, parallel plots, and an underlying sense of the extravagant, the exquisitely oriental and fabulous…which is what makes a good story-teller, and Dumas is one of the best—I would say he is the Dickens of the French writers.

Dumas paints a picture of a central character which is young, spirited, talented and hopelessly in love. Then, by the treachery and jealousy of ‘friends’ the protagonist’s world is shattered when he is thrown in prison and left there to perish. Life is a living hell for Edmond Dantes, but in his suffering he meets a man of honour, a fellow inmate who teaches him chemistry, several languages, politics and opens up Edmond’s spirit so he is moulded into a man of wisdom, a man of the highest educational standard, a true phenomenon. And Dantes does escape, eventually.

Now, free, and the inheritor of his teachers’ fortune, Edmond wears the shroud of the mysterious and magnificent Count of Monte Cristo. Old acquaintances are revisited, God’s wrath is acted upon them in acts of just punishment, and new friendships are born, all of which keep the reader turning the pages with relish until we reach a most satisfying finale.

I so enjoyed both books by Dumas that I will endeavour to get my hands on all the books he has written and to read them all. I’m open to any recommendations by fellow readers on this French giant of story-telling.

April 21, 2017

The Monk by Matthew Lewis

This tale is full of plots and twists. It starts off with innocence, but, like the serpent in the Garden of Eden, the snake of vanity is nestled in the monk’s bosom. And, as the story progresses we see that this orphaned boy, who is taken in by the monks develops into a character who, though he is believed to be saintly, in fact nurtures a character without compassion. As Matthew Lewis weaves his tale of treachery, we are confronted by pillars of religion: on the one hand the nuns of St Clare’s Convent and on the other the abbots of the Capuchin in Madrid. Lewis reveals in the characters of Reverend Ambrosio and prioress Agatha how from their positions of power they are able to torment lesser souls; we at once feel Lewis’ contempt for religion: perhaps during the time of publication—late eighteenth century—feelings against the Catholic Church which was seen as all-powerful and corrupt, were at their zenith. In any event, Lewis paints a gloomy picture and we are introduced to Satan and his devils in humanly form which they take to lead astray the characters in the novel.

I can well imagine how this bold outlook and the descriptions of Satan in league with and tormenting the holy would have upset the readers of the time which explains why the publication had to be modified. This novel, in line with a few other Gothic novels such as ‘Wuthering Heights’ and paranormal novels such as ‘Frankenstein’, pushed the boundaries of their times and attacked religion which had become stagnant and needed revitalising, and looked upon creation and the development of science at different angles. The Monk, unlike Frankenstein, does not delve into scientific issues, but it does attack the Catholic faith and paints the monastic life in the most gloomy and suspicious colours. A happy balance needed to be reached and Lewis was an advocate for the opposite view.

The moral of the story, without giving it away, is that what at first sight might seem pure and just, can prove to be evil and can be brought down if vanity burns too brightly in the victim’s breast. The characters portrayed are rich, interesting, and we follow their development and tragic ends with bated breath. The story has both a happy and tragic end which remains in the reader’s mind well after the conclusion of the tale. In Matthew Lewis’ ‘The Monk’ we have a good story, not as great as Alexandre Dumas’ ‘The Three Musketeers’ or Mary Shelley’s ‘Frankenstein’, but entertaining nonetheless.

April 18, 2017

Gone with the Wind by Margaret Mitchell

What a massive and most enjoyable book! Mitchell, in Scarlett O’ Hara and Rhett Butler, has created characters that are simultaneously larger than life and absolutely believable and genuine. Though O’ Hara is ruthless, spoilt and egotistic, she at once draws the reader’s interest and through her escapades, sufferings, and her explosive character, keeps the reader fully engaged. I kept turning the pages eagerly to see what she would get up to next. And she never failed to amaze me with the way she dealt with matters. Her relationship with Butler is explosive, full of twists and turns, and leaves the reader always wondering what will come next and on unsteady ground. Mitchell is anything but predictable.

Thanks to ‘Gone with the Wind’, I learned about the American civil war and ‘lived’ through the futility of it. Now, I confess I know more than I ever did before about the origins of the two ruling parties in the States: Republicans and Democrats. Republicans originated in the north and their adversaries in the south. Not knowing a lot about USA history, I find myself wondering how all this has changed over the years, for surely the two parties are spread throughout the States and have come to represent something different in modern times. Perhaps I will come across a new novel which will entertain me and simultaneously shed light on the development of these political parties.

I confess that I found the characters in this novel better developed, more fleshed out than in any book I have read before, except, perhaps, Dickens. This work is truly a master piece and I give it a full star rating without any hesitation.

April 7, 2017

Lady Chatterley’s lover by D.H. Lawrence

You either like an author’s style or you don’t. Some novels you start to turn the pages and you are hooked and can’t stop reading until you reach the last page. Other stories start slowly and gradually develop until you are left fulfilled and pleasantly surprised. And no two human beings are the same, so what works for one might not work for another.

I’ll start by saying what I liked about the novel. I’m glad Lawrence had no qualms about the sexual interplay and was graphic to a shocking extent for the time period involved—early 20th century England. In keeping with older works, like Harding’s Tess of the D’Urbervilles, there is an attack on modern industry, specifically the hardships of the coal works. There is also an attack on the upper classes and how they viewed and treated the middle and lower working classes.

Through Clifford, Lady Chatterley’s husband, Lawrence reveals the horrors of war, as Clifford returns from war severely handicapped and unable to feel or move his legs—he moves around in a wheelchair and a machine. Lady Chatterley—Connie Reid—is subjected to her husband’s will and is forced to take care of him at the start of the novel. The author reveals how Connie is bodily and spiritually reduced by this relationship in which her husband attaches to her and sucks the energy and life out of her whilst he pursues his interests in writing and simultaneously lords it over the coal workers toiling at his father’s mine.

Love and the liberation of Connie’s spirit enter her life in the form of a middle to lower class employee, the gamekeeper of the Chatterley estate, Oliver Mellors. Oliver is everything Clifford is not. Clifford embraces his upper class roots and soon reveals his overbearing and clingy nature. Oliver, though he was given the opportunity as a young lieutenant to escape his working class roots, shuns the hypocritical eunuch-style gentlemen of the upper echelons of society, and rather embraces his male nature and the freedom to access his primitive passions and sensualities.

Connie embraces and learns to worship the wild, savage passion of her lover and gradually peels away the layers of dominance Clifford has woven into her: it’s as if she pulls each root away and heals the wounds with Oliver’s lovemaking.

Though there is love in this novel, and the usual ideas revolving around the deleterious effects of industry, the male and female struggles that existed in all strata of society, the clash of the classes, Lawrence’s novel was a hard read for me, and did not manage to excite me enough to award him with a four star. Some parts of the book I flicked over, those parts where I felt that Lawrence was philosophising too much, and concentrated rather on the relationships between the characters. I suppose I fall in that smaller category of readers that would describe D.H. Lawrence as talented but not great, having written a nice (not thrilling) tale.

Despite my feelings concerning the novel, I am eager to admit that I found the 2015 movie version of the novel, starring Holliday Grainger and Richard Madden, lovingly created and interesting, but not very true to the novel as there was some flourishing of the characters and emotions portrayed between Connie and her husband which were not made reference to in the novel. Also, the actor chosen to play the role of Clifford’s nurse is much younger than the character in the novel. But, overall, a satisfying movie version of the novel.

March 31, 2017

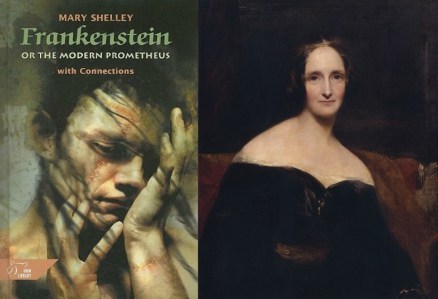

Frankenstein by Mary Shelley

What a brilliant story! Nothing at all like the Hollywood versions.

The things I liked: it has an adventure, trekking across different landscapes in a never-ending chase of revenge and torment. The frame narrative suits it so well. It juxtaposes passion and love with disgust and cruelty. Characters are lovingly created; there are life stories within life stories. It tackles disturbing issues concerning the advancement of medical science and how this treads a thin line with what is moral.

The idea of dead body parts coming back to life was something fantastical and outrageous in the day of Shelley (early nineteenth century). Now, just over two hundred years later, science has advanced to the point where donation of organs actually saves lives and is the only recourse for many sufferers with kidney, heart, and other organ failure. Shelley, a writer ahead of her times, tackled these issues, and revealed that in pursuing personal glory and fame, man is capable of crossing the boundaries and entering unchartered and quite possibly unethical territory. In our present, governing bodies and law makers are forced to tackle issues that just a few hundred years before belonged in the sphere of fantasy. Modern science is able to clone animals—perhaps human beings too. Human eggs can be fertilised outside of the womb. Human organs can be grown from stem cells and laboratory doctors and scientists are confident that they can produce human organs in pigs, however laws passed by the National Institutes of Health in 2015 instituted a moratorium on using public funds to insert human cells in animal embryos. As a point of interest, in the States, there are 76,000 people anxiously waiting for organ transplants in order to live a normal life.

Returning to our story, Shelley paints a very disturbing picture whereby a new species is created by human intervention: a being made from body parts of dead humans. The being is awakened through the use of modern science and electricity. Its creator, Dr Victor Frankenstein, is horrified with his creation and turns away from it in disgust. The monster, an innocent being with the human capacity for love and learning, leaves the laboratory and soon comes up against human reactions of horror to its appearance. Forced to stay out of human sight, the creature finds a dwelling where it is able to observe a family without being exposed to them. It learns to read and speak and grows fond of the family members. When it finally decides to make an appearance, the family is horrified and the monster, embittered, flees and seeks vengeance on its creator for abandoning it. Shelley draws parallels here with Emily Bronte’s Wuthering Heights and her character, Heathcliff. The monster in Frankenstein, like Heathcliff in Wuthering Heights, is subjected to hatred and likewise develops into a vengeful and violent being. Shelley toys with the idea that had this hatred been replaced by compassion and love, the being might very well have developed differently.

This novel was so enjoyable, and so easy to read, that I finished it in a day.

March 24, 2017

Pride and Prejudice by Jane Austen

I found some parts of the novel, especially at the start, to develop slowly, but, once the main characters vying for Elizabeth’s affection were fully explained and developed, the story picked up interest and pace. Austen delves into the minds of the higher middle to upper class ladies of the eighteenth century in a classic tale of prince meets pauper girl, fall in love, and live happily ever after. Of course, she—the writer—introduces us to an unusually witty character in Elizabeth, and through her experiences reveals how the mothers of that century were just as anxious about marrying off their daughters as women have been until the mid-twentieth century. In our modern times, with some couples living many years together before the question of marriage being brought up—if ever, we can see how drastically this has all changed, BUT, having said that, I am still left wondering if this anxiety does not still persist in some upper class families and most surely in the royal families of Europe and beyond. So, it is an issue that might still be applicable in our times as well.

Austen, in a backdrop of entertainment balls, introduces us to higher society England and travels us from the north western districts of greater London to the inner city. It’s no wonder that with such a setting, this novel has been reproduced in film. In fact, my enjoyment of the works was increased when I supplemented my having read the book with seeing the 2005 version of the novel in film, starring Keira Knightley as Elizabeth Bennet, and Matthew Macfadyen as Mr Darcy. In this film, I feasted my eyes on the Victorian style houses, the grand halls and manors with luscious green lawns and beautiful gardens, and the delightful costumes of the age.

In conclusion, Jane Austen’s tale ends joyfully enough but, were I to compare it with the tragedies that play out in Dickens’ ‘Oliver Twist’, or the soul wrenching works of Bronte in ‘Wuthering Heights’, I would have to place Austen’s ‘Pride and Prejudice’ in a slightly lower league, which is not to say that the novel is undeserving, just that comparable works of the period are better.

March 17, 2017

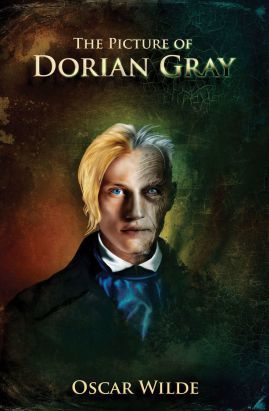

The Picture of Dorian Gray by Oscar Wilde

This was one of those rare novels which, once I started reading, I could not put down until I finished it in one day: it’s not a long book, just over 200 pages. If I’m not mistaken, this is Wilde’s only book—published in 1891, the rest of his works being plays, and was written at a time when homosexual behaviour was persecuted in the UK: Oscar Wilde was convicted in 1895 to two years in prison with hard labour for acts of gross indecency with men.

The protagonist of Wilde’s novel is a young man named Dorian Gray. The novel begins by expressing the beauty of Dorian Gray as seen by the two older gentlemen who enter his life: the artist Basil Hallward who paints Dorian’s portrait and is infatuated by him, and a gentleman named Lord Henry Wotton. The author enters the minds of both elder gentlemen and through their speech and thoughts expresses the love they share for Dorian which at times is so passionate it goes beyond mere friendship and hints strongly at homosexual attraction. As the novel develops, however, Dorian is kept by the author from falling in love with the two men (probably at the behest of his editor and publishers, and to adhere to the Victorian sense of propriety) and is portrayed in heterosexual relationships through which we see the influence of Lord Henry on young and impressionable Dorian, and how, with the passage of time, his treatment of those who come in contact with him becomes deleterious and poisonous with disastrous results.

Throughout the novel, the author, I feel, uses Lord Henry to express his own views on life, only with Lord Henry he let’s go of all inhibitions and restraints: lets him run freely. The author uses Dorian and the shaping of his character and the consequences of his actions, as a result of him adhering to Lord Henry’s philosophy of life, to reveal what Wilde believes would be the consequence of a world where people would have no restraints whatsoever. It’s as if the author is holding up a mirror and contemplating the consequences of his own life. It’s somewhat ironic that the events in Wilde’s subsequent life come to justify his fears. Perhaps the message in Wilde’s novel is that one has to have boundaries, limitations.

Dorian in the novel is penalised for his use of drugs, his harsh treatment of his lovers, his lack of compassion for his fellow man, his dangerous rage which leads to the murder of even his closest friends.

Another tragic irony is that this novel was used in court to support the Marquees of Queensberry’s case against Wilde when he charged the author of having homosexual relations with his son.

This was an extremely well written novel, reveals Wilde’s wit, gives a rare insight to the author’s deepest thoughts and anxieties, and is a work that keeps the reader glued to the pages as the tension builds up, the protagonist gradually sinking further and further into a pit of self-degradation with results which are often unexpected and particularly disturbing and harsh. Perhaps this can explain why this work was so badly received with very hurtful reviews when it first came out, and how in future generations, with the benefit of a free, fairer and more tolerant spirit it has come to occupy such a renowned position in the English classical novel collection.