J.L. Forrest's Blog

December 28, 2019

Essay: Science Fiction and the Personal-Political

This essay begins with the following premise:

Everything is political in the sense that any action we take or decision we make or conclusion we reach rests on assumptions, norms, and values not everyone would affirm. That is, everything we do is rooted in a contestable point of origin; and since the realm of the contestable is the realm of politics, everything is political.1

“Any action we take” includes the action of writing. Today, we often hear that authors should leave politics out of their fiction and that books are for entertainment, as if anything political is automatically unentertaining.2 Politics in fiction is a touchy subject.3 To approach it, I’ll explore three premises:

First, our political truths are diverse, and since fiction is the lie through which society discusses uncomfortable truths,4 we had best be able to express our political truths through it.Second, as others have argued, apolitical fiction does not and cannot exist. In fiction, the supposed absence of political content is invariably political.

Third, it follows that all fiction fits into one of three categories:

Message Fiction: Fiction written to make a political point, where the point is thinly disguised and polemical, often depending on straw-man arguments. In other words, message fiction is both poor writing and poor politics. Some message fiction might be better than others, and the threshold between message fiction and astute fiction is undoubtedly subjective.Obtuse Fiction: The story may be well told, it may be hack garbage, it may be anywhere along that spectrum, but this fiction possesses no political self-awareness. The politics are there, in the prose, but it’s likely the author had no idea.Astute Fiction: For writing to be politically astute, it’s almost always well written. In astute fiction, the political themes emerge clearly and naturally from character, have natural consequences within the plot, and address complex issues from multiple angles without resorting to straw-man arguments.

As always, there is good writing and poor writing. Good writing recognizes that all writing is political and manages that reality expertly. If the above premises are true, then:

Writers must grapple with political themes.Since we cannot avoid them, we should learn to write them skillfully. What makes for ham-fisted writing, and conversely how might we incorporate the political in entertaining, artistic, and compelling ways?

Writing is a political act. Even a grocery list, which many believe is for no one but themselves,5 contains a political element. Where do you shop: Whole Foods, Walmart, or your local farmer’s market? Are you buying organic or conventional? Any palm oil in your groceries? How much are your shopping choices rote habit, without reflection on the impacts they make upon society?

Writing establishes perceptions and reinforces behaviors, though at first draft it affects only the writer and is a personal activity.

Yet it is one of the only personal activities which can translate the inner world of the writer’s psyche to the psyches of others, sometimes in the millions. When intended for public consumption, it is therefore a political activity—a species of telepathy which passes from the individual to the community, reinforcing or challenging the norms of that community.

Conceptually, the personal and the political share a stronger relationship than we might assume, and writers should understand this as much as they understand that all writing is political. Through the remainder of this essay, I’ll try to illuminate these ideas in five ways:

By unmasking the dichotomy of the personal-political. By exploring the domestic, and showing how this most private of concepts plays out politically through writing. By showing how we can only believe that writing is apolitical from a position of privilege.By investigating speculative fiction, especially science fiction, and its relationship to political discourse.By suggesting some dos and don’ts for consciously writing for the political into our fiction.

I. The Dichotomy of the

Personal-Political.

My trusty dictionary defines political as “relating to the government or public affairs.” For writing to be political, it needn’t discuss the President, the votes of Congress, or a state election. Writing of public affairs is enough to make a story political. Naturally, this raises an immediate question:

Is it possible to write a story which deals only with private affairs, making it apolitical?

In short, no.

My dictionary defines personal as “of or concerning one’s private life, relationships, and emotions.” Tautologically, we may interchange the words private and personal.

The emotional need for privacy is powerful. Individually and culturally, we construct personal-private boundaries, both psychological and physical. We defend our privacy and, in the United States, the Fourth Amendment exists to protect it. Neither a state, nor any other power, can secure absolute control over a population so long as individuals retain some privacy, a point underscored by George Orwell.6 Thus the ongoing struggle for privacy, or declaring something personal, is counterintuitively a publicly political act. It follows that the personal is political.

By logical extension, nothing can be purely private, but all which is political and all which is personal occupy a spectrum. This personal-political spectrum shifts endlessly, according to culturally arbitrary standards and political struggles.

For example, what people do in the bedroom is personal, is it not?

In 2003 the U.S. Supreme Court invalidated criminal sodomy laws in all fifty states, but a dozen still outlaw it, including Alabama. In the Yellowhammer State, boinking a consenting partner in the ass is by legal definition an act of public concern, amenable to political discourse, and police regularly cite those laws to make unconstitutional arrests.

In seventeen states, homosexual sex remains illegal, despite federal law, proof that rightwing interests exercise real power over personal affairs.7

Liberal authorities, too, enforce thresholds beyond which the privacy of sex enters public-political concern: Bring a child into the act, and all fifty states and most of the rest of the world takes umbrage. (Though throughout the United States it is still possible for children to marry young,8 sometimes after obvious statutory rape, thus absolving the rapist in the eyes of the law.)9 To damage children is to damage their families and communities, to damage their futures, and to damage society. No threshold of right-to-privacy depoliticizes violence against children.

Public concern with the personal doesn’t stop at sex. Pro-choice advocates argue the abortion decision resides between a woman and her doctor, and it is her choice alone to make; pro-lifers disagree, and the topic remains as politicized as any can be. So long as members of a society contest them, the most personal of acts make the leap to the political in a twinkling.

Similarly, what you take into your body is no one’s business but yours, unless the law establishes controls for your substance of choice. Every time I purchase Sudafed, my local pharmacy scans my ID. Whoever reads those data can conclude I’m suffering from hay fever. If I buy enough pseudoephedrine, though, they might reach the conclusion that I’m cooking methamphetamines. For this reason, the state tracks these transactions, but what about logging purchases of birth control, mood stabilizers, or medications for pre-existing conditions? Under federal and state laws, most such information is “private,” but in today’s world of hackers, partisan politics, corporate rights, and commercial privatization (ironically named, for an ongoing threat to personal privacy), how easy is it to imagine the publication and politicization of data that today we consider protected?

Dystopian phantasmagorias abound.

In many states and most countries, using pot in one’s home is due cause for the state to batter down your door and incarcerate you, and legalization may at any time be reversed.10. In a legal reversal, how many individuals would already be on record as pot users, would then me on the watchlists of law enforcement?

A dearth of regulation may also elevate the personal into the political. In 2017 the average wage gap between women and men was 21¢ for every dollar.11 Perennially, for many women and their allies, their personal experience of lost earnings translates into a political effort to promote equality.

Is a uterus public or personal? Is your relationship with a doctor, or is your health, your concern? Are the affairs of multinational corporations private? These and a legion of other issues form the personal-political landscape, a complex and ever-evolving conversation (or shouting match, or fistfight, or gun battle).

Humans often fail to understand how the personal is political until they personally experience their lives being regulated, repressed, or attacked by public policy. The truly privileged can go a lifetime without understanding this. Yet the threat of the political becoming personal is omnipresent for everyone, no matter their station. “First they came…”12 for everyone but me.

Though as important today as ever, these ideas are nothing new. The Personal Is Political13—in 1970, Carol Hanisch wrote, “One of the first things we discover… is that personal problems are political problems. There are no personal solutions… There is only collective action for a collective solution.”

Let’s add that The Political Is Personal, because we tell stories through points of view. We impose upon our characters, consciously or unconsciously, POVs “rooted in a contestable point of origin.” Every POV represents a political position, as explored through an imagined personal position. Unless we’re writing solely from our unconscious biases or to construct a straw-man argument, different POVs will represent conflicting positions, and they will do so as honestly as we’re able to write them.

Never neutral, our published fictions nudge our real-world culture. They may suggest a greater good or, by reinforcing systems of might-makes-right, they may contribute to real-life injustice.

II. The Concept

of the Domestic

Much of contemporary literature deals with the domestic. Domesticity is a specific form of the personal and private. which deserves deeper consideration. For borrow Bob Shacochis’s model for a “literature of political experience” or a “literature of domestic experience.”14

Ancient patriarchal systems15 envisioned domestic arrangements as microcosms of larger societal structure; e.g., as the emperor was the head of society, the paterfamilias was the head of the household. This social construct remains a powerful and important part of our culture to this day. Though fractured, the patriarchy remains strong.

In the United States, an early rivening of that patriarchy and a reordering of the “American domestic” occurred during the Civil War. Brothers fought brothers, yes, but many slavers interpreted emancipation as a division of their family, an intrusion on their domestic affairs by state forces. For the Union, the Confederacy, and the slaves themselves, the political and the domestic were inseparable.

Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin did not launch the Civil War,16 but its characters, including slaves and slave owners, and their familial and delicate relationships, illustrated the personal nature of the politics of slavery.17 Uncle Tom’s Cabin certainly influenced Union thinking, and its message impacted generations of Americans, strengthening anti-slavery sentiment after the ratification of the Thirteenth Amendment.

In “The Thoreau Problem”, Rebecca Solnit wrote, “If [Thoreau] went to jail to demonstrate his commitment to the freedom of others [slave specifically], he went to the berries to exercise his own recovered freedom, the liberty to do whatever he wished, and the evidence in all his writing is that he very often wished to pick berries.”18 She refers to the innate strain between the domestic Thoreau of Walden19 and the communitarian Thoreau of Civil Disobedience,20 a strain which Solnit argued is no strain at all, but a necessary condition of free society. To retain our personal freedoms, goes the argument, we must at times engage politics and public life; to do that, we must sometimes rest and find domestic respite.

The domestic and political make each other possible and are cyclical.

Thus writing, too, is a cyclical act which engages politics and public life. We influence through our writing, and are influenced by our reading.

What’s more, the politics inherent in published works can take on life independent of their authors. Readers conscript fiction into political service, with or without the author’s permission. Mohsin Hamid, the British-Pakistani writer, observed, “Politics is shaped by people. And people, sometimes, are shaped by the fiction they read.”21

Thus irresponsible writing, produced for “entertainment,” can affect terrible outcomes. Umberto Eco illustrated this excellently in his analysis of Eugène Sue’s The Wandering Jew, and how it escaped Sue to become The Protocols of the Elders of Zion.22 What began as flaccid amusement ended by justifying, in the minds of Adolph Hitler and his supporters, the extermination of six million Jews. On this example alone, let no one declare that simple fictions cannot spur political outcomes.

Francine Prose wrote:

Perhaps the clearest case of literature effecting political change is that of Upton Sinclair’s 1906 novel The Jungle. Its disgusting portrait of the meatpacking industry rapidly led to the passage of the Meat Inspection Act and the Pure Food and Drug Act. So what if Sinclair had hoped that his work would end the oppressive conditions under which industry workers labored rather than merely improving the quality of the protein on middle-class tables?23

Politicizing forces can twist fiction to any purpose, and these days disinformation is common. The best writers will bear this in mind.

III. Privilege and the

Personal-Political

in Writing

My dictionary defines privilege as “a special right, advantage, or immunity granted or available only to a particular person or group of people.”

Privilege allows some readers, and writers, to imagine that writing can be apolitical. This is especially true for fiction. Privilege offers the power, willfully or ignorantly, to ignore social subtexts.

Blindness to subtexts can also afflict the oppressed, who may accept persistently imposed narratives about their own race, gender, or background. Let’s focus on the privileged, rather than the oppressed, the former being the cause of the latter.

For example, one might enjoy Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice as an intelligent, witty tale of tangled romance, a prototype for all romances since, whose enduring theme has always been love conquers all.

“Where are the politics?” one might ask. “And why won’t you leave my sentimental beach reading alone?”

Pride and Prejudice tells of the fraught courtship between Fitzwilliam Darcy and Elizabeth Bennet, yet it’s a damning commentary on the socioeconomic oppression of women, during Austen’s time and by extension today. Its characters act within the legal realities of nineteenth-century England and the entailing of property, which Austen also emphasized in Sense and Sensibility.

Mr. Benet’s daughters could not inherit, not even if he desired. If unmarried at his death, Elizabeth and her four sisters would become destitute, homeless, and anathema. The story’s courtship, proposals, and romance occur not with entailing as the backdrop, but because of it. The romantic misadventures overlay a tapestry of insurmountable legal constraint, oppression, and sexual politics. The personal narrative of Pride and Prejudice contains an outcry for political reform which, once perceived, dominates.

Without the constraints of entailing, imagine the plot: Darcy would be irrelevant by chapter nine. Lizzy would bide her time and, after inheriting a fortune, the smart, capable, witty woman could have leveraged her own means and done anything she liked. With or without a man, she could have used her astute skills of social observation to work the markets of an industrializing England. I’d buy that story.

A century before suffrage, Pride and Prejudice was a cry for women’s agency. So much for “sentimental beach reading.”

Similarly, the gothics wrote narratives ripe with sociopolitical subtext. In Emily Brontë’s Wuthering Heights, the character of Catherine Earnshaw withers (wuthers?), her nature crushed by sociocultural pressure.

Shelley’s multilayered Frankenstein was a forerunner of modern science fiction and horror, and it it utterly rejected everything society normalized prior to the nineteenth century.

Stoker’s Dracula brimmed with commentary about emerging industrialism, empowered femininity, homosexuality, and capitalism—all impossible for Stoker to express publicly, in his era, without the mask of fiction. Dracula exemplified the Camusian idea that “fiction is the lie through which society discusses uncomfortable truths.”

Anachronistically, removed from these texts by centuries, we may impose own meanings upon them. Yet even in their times, they were never mere entertainments, fluffy stories of tragic romance, mad scientists, and creatures of the night.

These books were powerful personal-political statements, capable of expressing beliefs through fiction which could not survive an outright declaration.

There are no great works of literature which fail to illuminate the personal-political. Hemingway, Fitzgerald, or Nabokov; Woolf, Mansfield, or Stein—all were political in their writing, whether overtly or in terms of personal identity, though their politics could be difficult to pigeonhole.24 In today’s era of polarized politics, political thinking can and perhaps should be viewed through nuanced lenses. We needn’t fall into camps, we don’t have to be tribal, and what better way to explore such a non-tribal society than through fiction?

The authors of yesteryear did sometimes reject the political natures of their own works. Virginia Woolf insisted on the apolitical quality of her own writing while spurring generations of political insights.25 Her view of her work suggests the strange idea that once creative artifacts spread into the world, their creator becomes simply one more subjective reader of them.

The personal-political in today’s contemporary fiction is no less present or powerful than it was for the modernists. Sometimes graceful (re: Ondaatje),26 sometimes clumsy (re: Franzen),27 today’s fiction is perhaps more concerned with identity politics and domesticity than were its forebears, but perhaps not; identity politics has been the politics of the last century, first blindingly white and now increasingly rainbow.28

Identity politics, emblematic in contemporary literature, underscore literature’s unavoidably political nature.29

Still, I can hear the affirmed escapists asking, “But what about the real beach reading?”

The mainstream fiction? Today’s romances? Can’t we have a frivolous read, without the weighty and socially responsible thematics?

Sorry, no. We may read any story for escapism, but we’ll need to disable our inner critic if we’re to pretend it’s apolitical.

Does any given bodice-ripper30 reinforce or challenge mores of sex, gender, and race? Does it exclude the disempowered, reinforcing only the tropes of WASPy suburban readers?31 Does it reinforce stalking behavior and patterns of abuse?32 Never mind Fifty Shades of Grey.33 Every story of romance, on some level, rises to these issues or fails to our collective detriment.34 We are capable of ignoring personal-political themes in any writing only when they are so familiar to us, or we are so unaffected by them personally, as to render them invisible.

What about whodunits and mysteries?

Notice the preponderance of youthful, well-to-do, attractive, white women-as-victims in twentieth- and twenty-first-century thrillers. The detectives leap to help them or to uncover their murderers, no matter the costs. But black women, old women, disfigured women, cat ladies? Not so much.

“Missing white-woman syndrome” exists in literature as much as it does in real life.35 But does fiction reflect life, or life reflect fiction?36 Certainly, they reinforce one another.

In science fiction, consider The Expanse.37 Detective Miller has seen a lot of bad shit go down, out there on Ceres, but wow does he go out of his way for a young, rich, and beautiful Claire Mao.38

Writers have more license than most to alter the narrative of society. “Ils doivent envisager qu’une grande responsabilité est la suite inséparable d’un grand pouvoir.”—They must consider that great responsibility follows inseparably from great power.39

In mainstream fiction, politics abound. Toward the end of his life, Michael Crichton became overtly political, but political themes run throughout his many novels. Stephen King, these days vocal about his positions, infused even his early books with underlying personal-political ideas.40 J.K. Rowling,41 Danielle Steele, Jackie Collins, Dean Koontz, Paulo Coelho, James Patterson, C.S. Lewis, Clive Cussler, Anne Rice, Ian Fleming, or Tom Clancy: each author has reinforced or challenged a political status quo, and we may interpret each of their books through personal-political themes. Each of those authors also counts among the best-selling authors of all time.

Despite this, in fiction the word political often draws disdain, as if entertainment must necessarily be apolitical. As if it can be. If our grocery lists can’t avoid the political, what hope does our fiction have?

IV. The Personal-Political

in Speculative Fiction

More than other fictions, science fiction imagines what reality might become, for better or worse. Desires for change—for new social orders, for new day-to-day pursuits, for new family structures, for new genetics, for new culture-changing technologies—are inherently political. Thus science fiction is fundamentally political.

This goes double for fantasy. Many fantasies could one day, in some place, in some fashion become reality, but even if not they can inform our thinking about our present reality.42 Thus all speculative fiction—both science fiction and fantasy—possesses a personal-political power.

Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein43 was among speculative fiction’s first true novels, but many prototypes predated it. They include One Thousand and One Nights,44 the Theologus Autodidactus,45 or even Utopia.46 Traditional stories from Japan, China, Greece, Egypt, Mesopotamia, India, and others carried the seeds not only of technological but also of social speculation. In prototypical science-fiction stories, imaginative technologies intersect an extant society to alter that society.

With few exceptions, the prototypes of science fiction explored sociopolitical themes which today we would recognize as libertine or liberal, even if they retained or reinforced other, more conservative themes. For example, More’s Utopia was a veiled, anti-authoritarian critique of Henry VIII, envisioning an egalitarian, anarchical, communal society. Yet Utopia also called for stringent marriage rules and repressive constraints on women, as if More could imagine an egalitarian society but only so far.

Since Frankenstein, the politics of speculative fiction have become more complex and more nuanced. In some cases, like an echo of More’s misogyny, science fiction has also envisioned worlds more patriarchal or authoritarian.

To a degree, socially conservative science fiction seems a reaction to progressive visions. The Enlightenment propagated humanism and secularism, destroying monarchies and weakening religion’s hold on politics. These changes, fewer than three hundred years old and by no means secure, threaten the fundamentalist beliefs of hundreds of millions of people. The extremisms confronting us today are responses to a global, secular society, one which promised equality and liberty, but which has left many disenfranchised, even if temporarily. As social conservatives reassert their personal-political positions, some will write science-fiction and fantasy which espouses conservative or fundamentalist ideologies.

Such reactions have happened before.

During the development of post-War liberalism, Ayn Rand conflated Stalinism and Marxism. In response to what she perceived as the inevitable autocracy in socialism, she developed a shaky counter-philosophy. Turning morality on its head, she equated greed with good and wrote The Fountainhead47 and Atlas Shrugged.48

Rand arrived in the United States at the impressionable age of twenty-one, shortly after Lenin’s death and about a decade before Stalin solidified his power. Before then, while she’d derided the Bolsheviks, she’d been an ardent supporter of Alexander Kerensky, whose philosophy was opposite to Rand’s later Objectivism. By the time Stalinism had wiped away Marxist and Leninist principles, Kerensky was in exile.

In 1938, Rand wrote to Kerensky, when they were both in the United States. Even then she expressed that Kerensky might have provided a better foundation for what would become the Soviet Union. I know of no evidence that Kerensky ever replied to her letter, and her admiration for his purer socialism seems to have died with her unanswered letter.

December 27, 2019

Essay: Footprints in the Snow

Plotter or Pantster?

“Are you a plotter or a pantster?”

This question bothers me. Taken at its most literal, it reduces writing either to rigidly designed plots or to route-free streams of consciousness. Neither model of the writing process is true or helpful.

Most writers waffle. “In some ways, I’m a plotter,” they often answer. “In others, a pantster.” A lukewarm response seldom satisfies, and a more definitive one doesn’t either.

“I’m a plotter.”

“I’m a pantster.”

A plotter who presages every twist of every scene, who never finds gratifying surprises in their own words? A pantster who never knows where the story will head next? In either extreme, there seems to be some a priori illogic, a struggle around the very idea of plot.

Yet what are we to make of plot? And how else can we write plot except to either plot the hell out of it (plotter), throw caution to the wind (pantster), or mix the approaches in some arbitrary and obtuse way?

Grade-school taught us the basic elements of story:

PlotCharacterSetting

(If we were lucky, we also learned theme, voice, and style, but those we’ll explore another day.) For now, consider this possibility:

Writing foremost for plot is, in fact, a dangerously counterproductive, misleading approach to fiction writing.

Footprints in the Snow

In the sense most schools teach it, plot does not exist. It’s an illusion in the way that Sol going round the Earth is an illusion. Using plot, as a theoretical approach to writing, is incorrect in the way the theory of phlogiston was incorrect.

Plot is supposed to provide the scaffolding by which a story makes sense. Event A follows event B, the princess infiltrates the castle before saving the knight, or the spy steals the secret list after crossing the Iron Curtain into the U.S.S.R. A plot, in this view, is “just one damn thing happening after another,” something into which we install settings, characters, and themes.

This is nonsensical. Why does the princess want to save the knight? Why does the spy need to steal the secret list? Why must A follow B? Events exist only in relation to characters, never the other way around.

Said another way, plots don’t generate characters. Never ever.

Ray Bradbury wrote:

Plot is no more than footprints left in the snow after your characters have run by on their way to incredible destinations. Plot is observed after the fact rather than before. It cannot precede action. It is the chart that remains when an action is through. That is all Plot ever should be. It is human desire let run, running, and reaching a goal. It cannot be mechanical. It can only be dynamic. So, stand aside, forget targets, let the characters, your fingers, body, blood, and heart do.

Zen in the Art of Writing (1973)

In other words, plot is no tool for writers. At best, plot is a tool for analysis after the fact. Plot is for rewrites, for the writer to analyze whether the characters’ behaviors make sense. In the same way, plot is for editors. Plot is, more than anything, for critics professional and armchair.

Character and Agency

Let’s cogitate over several related ideas:

In literature, characters possess agency.In literature, agency is not only the power to act but the desire to act.In literature, everything which can act is a character.In literature, everything can act.In literature, everything can be a character. Everything.

The most important question about any character, more so than any other quality, is this: What does the character want? Without an answer, nothing happens. Consider:

Robert sits on a couch.

Our character, like any actor in a play, is begging for some motivation, some agency. Now:

Robert sits on a couch and, as he soaks in the afternoon sunlight through the living-room window, his tastebuds cry out for a beer.

Now we’re getting somewhere. Robert desires something, even if prosaic, a simple beer. He has motivation. So:

Robert sits on a couch and, as he soaks in the afternoon sunlight through the living-room window, his tastebuds cry out for a beer.

Remembering the cold ones he’d spied in the fridge, he stands, crosses into the kitchen, and reaches for the icebox door.

Action makes story possible, but it isn’t conflict. The conflict arises from tension between one character’s desire and another’s:

Robert sits on a couch and, as he soaks in the afternoon sunlight through the living-room window, his tastebuds cry out for a beer.

Remembering the cold ones he’d spied in the fridge, he stands, crosses into the kitchen, and reaches for the icebox door.

“Not so fast,” says Robert’s roommate, the man entering through the back door, his beard bristling, his body as hairy as a Sasquatch’s. “I’m not letting you nab another of my brews.”

“Oh, yeah?” says Robert. “How’re you going to stop me? I’m closer to the fridge than you are.”

“I’m closer to the knives.” The Sasquatch reaches for the butcher’s block, wraps his hand around the largest handle in the kitchen set, and draws the blade. The steel rings free.

This is story. No matter how complex a story becomes, it emerges naturally from character. All stories are proverbially the story of Robert and his hairy roommate, whether stories of violence or unrequited love, stories of class struggle, stories of dueling magicians, stories of green eggs and ham, stories of lusty gods, or even stories of humans vs. objects:

Robert sits on a couch and, as he soaks in the afternoon sunlight through the living-room window, his tastebuds cry out for a beer.

Remembering the cold ones he’d spied in the fridge, he stands, crosses into the kitchen, and reaches for the icebox door.

Stuck. Frozen shut.

The door taunts him.

He tries with one hand, then with two, and finally he presses his foot against the adjacent countertop, heaving with every thewy limb. He strains until his knee pops, and with a scream he drops to the linoleum floor.

After a minute’s cursing, Robert stands, winces, and limps toward the garage. “I’m getting the damned blowtorch, you sonuvabitch. Don’t go anywhere.”

Notice how the door verbs. It taunts him. Especially in prose, objects may exercise the same agency as any other character. Objects, in this fashion, are characters, pursuing their own desires. In the same way a roommate might wish to deprive Robert of a beer, so might the malfunctioning refrigerator.

The concept of objects with agency extends, too, to environments — thus to settings. Try:

Robert sits on a couch, gauging the ferocity of the blizzard which rages beyond the living-room window. Good thing he stocked up for the weekend, because who’d want to go out in that weather? A good weekend for staying in. A good weekend for a drinking binge.

His tastebuds cry out for a beer.

Remembering the cold ones he’d packed in the fridge, he stands, crosses into the kitchen, and opens the icebox door.

Empty.

Not entirely empty. There’s plenty of food. Condiments beyond counting. But no beer.

Carl! That drunkard of a roommate, that Sasquatch, he’d already sucked down the last of the brewskis!

After marching to the front door, Robert wraps himself in layers, bundles up his coat, and ties a woolen scarf around his neck. Outside, the storm howls. It batters the trees and hammers every surface into frozen white. It taunts him.

Fear me, it seems to say.

Beer before fear, thinks Robert, and Mario’s Liquors should still be open. Bracing himself for the bludgeoning cold, Robert opens the front door.

As he trudges down his street, a street become an icy wasteland, he leaves behind him only footprints in the snow. Footprints quickly erased, gone, lost forever.

The storm howls, batters, hammers, and taunts. This is a storm with which to battle. Absent Robert’s desire for beer, he’d still be sitting comfortably, warmly, and safely on his couch. Now he’s heading into below-freezing temperatures, heat-stealing winds, and blinding snow, making for a liquor store which should be open.

As the storyteller, all I need do now is decide how difficult this trek will be, and it could be brutal.

Beware pre-baked plots: the monomyth, the wagon wheel, the snowflake, the touchstone. Story organization is to story as musical arrangement is to music. Bach arranged for flute or kazoo, played forward or backward, is still Bach.

A Footnote on Structure

Does this mean that the Hero’s Journey, or any other number of storytelling structures, aren’t worth learning? As you develop your chops as a writer, can you skip the analysis of others’ structures, of historical structures and popular structures?

Hell, no.

But neither should the ordained structures tie you into a straitjacket. In the Hero’s Journey, does the Ordinary World make sense as a beginning for who your characters are, for the setting in which they find themselves? Does your protagonist endure one overwhelming Ordeal, or three or six or twelve or some other number? Does a Threshold Guardian, as such, stand between the Ordinary World and the Special World for your characters?

Ditto for every romance-novel or mystery plot you’ve ever encountered. Do those structures inform the travails of your characters uniquely? If not, discard them.

Same for the Old and Middle English structures of Beowulf or Chaucer. (Many have attempted to stuff Beowulf into the Hero’s Journey. It doesn’t work, though many older stories, like the Epic of Gilgamesh, match the Hero’s Journey perfectly.)

These are your choices to make, as a writer. Thoroughly well-trodden structures are not immutable laws which you must follow. But how to choose? Allow your characters—their desires, needs, quirks, and motivations—to choose for you. Characters are story.

Learn the classical structures, and learn all the new ones you wish, but know what you’re looking at is the footprints left by someone else’s characters over some other setting at some other time.

Copy and paste them, as you please, but don’t be surprised when your dissatisfaction follows you around like a beaten puppy.

Conclusion and Review

As a concept, plot is a tool for analysis after the fact. To begin with plot, at some core level, is an error.

Many writers will disagree, insisting how they’re “plotters.” I’d encourage them to reconsider, to meditate on Bradbury’s footprints in the snow.

The longer I write, the more finished words I complete, and the more I reflect on my writerly journey, the more I believe this:

When we set the words onto the page, there is only character. In fiction prose, there is only character. Begin with character, get character right, and the rest follows.

Footprints in the Snow

Plotter or Pantster?

“Are you a plotter or a pantster?”

This question bothers me. Taken at its most literal, it reduces writing either to rigidly designed plots or to route-free streams of consciousness. Neither model of the writing process is true or helpful.

Most writers waffle. “In some ways, I’m a plotter,” they often answer. “In others, a pantster.” A lukewarm response seldom satisfies, and a more definitive one doesn’t either.

“I’m a plotter.”

“I’m a pantster.”

A plotter who presages every twist of every scene, who never finds gratifying surprises in their own words? A pantster who never knows where the story will head next? In either extreme, there seems to be some a priori illogic, a struggle around the very idea of plot.

Yet what are we to make of plot? And how else can we write plot except to either plot the hell out of it (plotter), throw caution to the wind (pantster), or mix the approaches in some arbitrary and obtuse way?

Grade-school taught us the basic elements of story:

PlotCharacterSetting

(If we were lucky, we also learned theme, voice, and style, but those we’ll explore another day.) For now, consider this possibility:

Writing foremost for plot is, in fact, a dangerously counterproductive, misleading approach to fiction writing.

Footprints in the Snow

In the sense most schools teach it, plot does not exist. It’s an illusion in the way that Sol going round the Earth is an illusion. Using plot, as a theoretical approach to writing, is incorrect in the way the theory of phlogiston was incorrect.

Plot is supposed to provide the scaffolding by which a story makes sense. Event A follows event B, the princess infiltrates the castle before saving the knight, or the spy steals the secret list after crossing the Iron Curtain into the U.S.S.R. A plot, in this view, is “just one damn thing happening after another,” something into which we install settings, characters, and themes.

This is nonsensical. Why does the princess want to save the knight? Why does the spy need to steal the secret list? Why must A follow B? Events exist only in relation to characters, never the other way around.

Said another way, plots don’t generate characters. Never ever.

Ray Bradbury wrote:

Plot is no more than footprints left in the snow after your characters have run by on their way to incredible destinations. Plot is observed after the fact rather than before. It cannot precede action. It is the chart that remains when an action is through. That is all Plot ever should be. It is human desire let run, running, and reaching a goal. It cannot be mechanical. It can only be dynamic. So, stand aside, forget targets, let the characters, your fingers, body, blood, and heart do.

Zen in the Art of Writing (1973)

In other words, plot is no tool for writers. At best, plot is a tool for analysis after the fact. Plot is for rewrites, for the writer to analyze whether the characters’ behaviors make sense. In the same way, plot is for editors. Plot is, more than anything, for critics professional and armchair.

Character and Agency

Let’s cogitate over several related ideas:

In literature, characters possess agency.In literature, agency is not only the power to act but the desire to act.In literature, everything which can act is a character.In literature, everything can act.In literature, everything can be a character. Everything.

The most important question about any character, more so than any other quality, is this: What does the character want? Without an answer, nothing happens. Consider:

Robert sits on a couch.

Our character, like any actor in a play, is begging for some motivation, some agency. Now:

Robert sits on a couch and, as he soaks in the afternoon sunlight through the living-room window, his tastebuds cry out for a beer.

Now we’re getting somewhere. Robert desires something, even if prosaic, a simple beer. He has motivation. So:

Robert sits on a couch and, as he soaks in the afternoon sunlight through the living-room window, his tastebuds cry out for a beer.

Remembering the cold ones he’d spied in the fridge, he stands, crosses into the kitchen, and reaches for the icebox door.

Action makes story possible, but it isn’t conflict. The conflict arises from tension between one character’s desire and another’s:

Robert sits on a couch and, as he soaks in the afternoon sunlight through the living-room window, his tastebuds cry out for a beer.

Remembering the cold ones he’d spied in the fridge, he stands, crosses into the kitchen, and reaches for the icebox door.

“Not so fast,” says Robert’s roommate, the man entering through the back door, his beard bristling, his body as hairy as a Sasquatch’s. “I’m not letting you nab another of my brews.”

“Oh, yeah?” says Robert. “How’re you going to stop me? I’m closer to the fridge than you are.”

“I’m closer to the knives.” The Sasquatch reaches for the butcher’s block, wraps his hand around the largest handle in the kitchen set, and draws the blade. The steel rings free.

This is story. No matter how complex a story becomes, it emerges naturally from character. All stories are proverbially the story of Robert and his hairy roommate, whether stories of violence or unrequited love, stories of class struggle, stories of dueling magicians, stories of green eggs and ham, stories of lusty gods, or even stories of humans vs. objects:

Robert sits on a couch and, as he soaks in the afternoon sunlight through the living-room window, his tastebuds cry out for a beer.

Remembering the cold ones he’d spied in the fridge, he stands, crosses into the kitchen, and reaches for the icebox door.

Stuck. Frozen shut.

The door taunts him.

He tries with one hand, then with two, and finally he presses his foot against the adjacent countertop, heaving with every thewy limb. He strains until his knee pops, and with a scream he drops to the linoleum floor.

After a minute’s cursing, Robert stands, winces, and limps toward the garage. “I’m getting the damned blowtorch, you sonuvabitch. Don’t go anywhere.”

Notice how the door verbs. It taunts him. Especially in prose, objects may exercise the same agency as any other character. Objects, in this fashion, are characters, pursuing their own desires. In the same way a roommate might wish to deprive Robert of a beer, so might the malfunctioning refrigerator.

The concept of objects with agency extends, too, to environments — thus to settings. Try:

Robert sits on a couch, gauging the ferocity of the blizzard which rages beyond the living-room window. Good thing he stocked up for the weekend, because who’d want to go out in that weather? A good weekend for staying in. A good weekend for a drinking binge.

His tastebuds cry out for a beer.

Remembering the cold ones he’d packed in the fridge, he stands, crosses into the kitchen, and opens the icebox door.

Empty.

Not entirely empty. There’s plenty of food. Condiments beyond counting. But no beer.

Carl! That drunkard of a roommate, that Sasquatch, he’d already sucked down the last of the brewskis!

After marching to the front door, Robert wraps himself in layers, bundles up his coat, and ties a woolen scarf around his neck. Outside, the storm howls. It batters the trees and hammers every surface into frozen white. It taunts him.

Fear me, it seems to say.

Beer before fear, thinks Robert, and Mario’s Liquors should still be open. Bracing himself for the bludgeoning cold, Robert opens the front door.

As he trudges down his street, a street become an icy wasteland, he leaves behind him only footprints in the snow. Footprints quickly erased, gone, lost forever.

The storm howls, batters, hammers, and taunts. This is a storm with which to battle. Absent Robert’s desire for beer, he’d still be sitting comfortably, warmly, and safely on his couch. Now he’s heading into below-freezing temperatures, heat-stealing winds, and blinding snow, making for a liquor store which should be open.

As the storyteller, all I need do now is decide how difficult this trek will be, and it could be brutal.

Beware pre-baked plots: the monomyth, the wagon wheel, the snowflake, the touchstone. Story organization is to story as musical arrangement is to music. Bach arranged for flute or kazoo, played forward or backward, is still Bach.

A Footnote on Structure

Does this mean that the Hero’s Journey, or any other number of storytelling structures, aren’t worth learning? As you develop your chops as a writer, can you skip the analysis of others’ structures, of historical structures and popular structures?

Hell, no.

But neither should the ordained structures tie you into a straightjacket. In the Hero’s Journey, does the Ordinary World make sense as a beginning for who your characters are, for the setting in which they find themselves? Does your protagonist endure one overwhelming Ordeal, or three or six or twelve or some other number? Does a Threshold Guardian, as such, stand between the Ordinary World and the Special World for your characters?

Ditto for every romance-novel or mystery plot you’ve ever encountered. Do those structures inform the travails of your characters uniquely? If not, discard them.

Same for the Old and Middle English structures of Beowulf or Chaucer. (Many have attempted to stuff Beowulf into the Hero’s Journey. It doesn’t work, though many older stories, like the Epic of Gilgamesh, match the Hero’s Journey perfectly.)

These are your choices to make, as a writer. Thoroughly well-trodden structures are not immutable laws which you must follow. But how to choose? Allow your characters—their desires, needs, quirks, and motivations—to choose for you. Characters are story.

Learn the classical structures, and learn all the new ones you wish, but know what you’re looking at is the footprints left by someone else’s characters over some other setting at some other time.

Copy and paste them, as you please, but don’t be surprised when your dissatisfaction follows you around like a beaten puppy.

Conclusion and Review

As a concept, plot is a tool for analysis after the fact. To begin with plot, at some core level, is an error.

Many writers will disagree, insisting how they’re “plotters.” I’d encourage them to reconsider, to meditate on Bradbury’s footprints in the snow.

The longer I write, the more finished words I complete, and the more I reflect on my writerly journey, the more I believe this:

When we set the words onto the page, there is only character. In fiction prose, there is only character. Begin with character, get character right, and the rest follows.

December 26, 2019

Bee on a LOG

What’s up with the Bee

on the LOG

in my BLOG?

See a devotee

of a pun

anyone?

Self-evident, my dear Watson. Don’t overthink it.

#sogrid-1577406988529.sogrid--tos1{

font-size: 16px;

background-color: rgba(0,0,0,0);

margin-top: 0px;

margin-bottom: 20px;

}

#sogrid-1577406988529.sogrid--tos1 .sogrid__others,

#sogrid-1577406988529.sogrid--tos1 .sogrid__others .sogrid__entry,

#sogrid-1577406988529.sogrid--tos1 .sogrid__two{

border-color: #cccccc;

}

#sogrid-1577406988529.sogrid--tos1 .sogrid__entry__title a{

color: #191919;

}

#sogrid-1577406988529.sogrid--tos1 .sogrid__entry__meta{

color: #777777;

}

#sogrid-1577406988529.sogrid--tos1 .sogrid__entry__meta .sogrid__entry__author{

color: #777777;

}

#sogrid-1577406988529.sogrid--tos1 .sogrid__entry__categories a{

color: #e53935;

}

#sogrid-1577406988529.sogrid--tos1 .sogrid__entry__excerpt{

color: #555555;

}

#sogrid-1577406988529.sogrid--tos1 .sogrid__entry__readmore{

color: #ffffff;

background-color: #d32f2f;

}

#sogrid-1577406988529.sogrid--tos1 .sogrid__pagination{

border-color: #cccccc;

}

#sogrid-1577406988529.sogrid--tos1 .sogrid__pagination span{

color: #333333;

background-color: #e9e9e9;

}

#sogrid-1577406988529.sogrid--tos1 .sogrid__pagination span.__active{

color: #ffffff;

background-color: #d32f2f;

}

@media all and (min-width: 768px) {

#sogrid-1577406988529.sogrid--tos1{

font-size: 16px;

}

}

@media all and (min-width: 992px) {

#sogrid-1577406988529.sogrid--tos1{

font-size: 16px;

}

}

Uncategorized

Bee on a LOG

Forrest26 December 2019

What gives? A bee on a log in a blog.

Read More

Musings

A Relaunch

Forrest26 December 2019

I have a love-hate relationship with blogging. Yet I'm re-launching, foremost to focus my thoughts,…

Read More

A Relaunch

At various times I’ve had a love-hate relationship with blogging. Real time has passed since I last blogged. Months. So why re-fire the blog roll now?

Two reasons and one hope:

Reason One

Weeks ago, this website crashed, and it crashed hard. Unbeknownst to me, the backup engine hadn’t been functioning, so I lost multiple iterations of updates from the last site. All the more, I’d been relying on third-party software for all kinds of website functionality, and much of that software was no longer supported. A recipe for disaster.

In rebuilding the site, I’ve conceived on something more streamlined. Considering my books? How about a direct link to buy them. Interested in the Reading Series (and the soon-to-be-introduced-to-the-world Group 43, which will manage that series)? Bingo, one link. Checking on the latest news, think you might learn something here, want to engage in a dialogue? Wham, there’s the blog.

Less is more.

Reason Two

I’ve changed my thinking about the blog. Here’s what makes it more interesting, and easier, for me to write:

I’m not writing it for you.

Counterintuitively, this might make it more interesting for you, and for any other visitor here.

I’m writing this as a discipline, as a reflection of my thoughts outside the creative writing. Because I spent so many years as a teacher, some of this content will be teacherly: writing exercises, theoretical insights, and analyses. Mostly, I’ll be writing these for myself, but if anyone finds these helpful, great.

A Hope

That some do find these writings helpful; in fact, I hope many do. I hope that at least a few engage here, outside the hyper-capitalized environments of the social networks.

November 4, 2019

Hello world!

Welcome to WordPress. This is your first post. Edit or delete it, then start writing!

January 30, 2019

Reading no. 8 — Rebecca Hodgkins, Lou J. Berger, & Jamie Ferguson

Rebecca Hodgkins,

Lou J. Berger,

& Jamie Ferguson

For the eighth installment of the Science Fiction and Fantasy Reading Series, I invited editors Jim LeMay and Chuck Anderson of Mad Cow Press to once more bring us one of their anthologies. They delivered with the impressively fun A Fistful of Dinosaurs.

Rebecca Hodgkins read her marvelous and touching “13 Ways of Looking at a Dinosaur”, an homage to Wallace Stevens 1954 poem, “13 Ways of Looking at a Blackbird”. Lou J. Berger brought us “The Serpent of the Loch”, a long-lost adventure Arthur Conan Doyle’s Professor Challenger, taking place perhaps between The Lost World and The Poison Belt. Finally, Jamie Ferguson read from “The Other Side of the Portal”, in which we met one of the most intelligent of all dinosaur species.

As always, BookBar gave us the most marvelous home for the evening. Books were sold and signed, and we had a great time. Go to BookBar, buy books, and support local and independent booksellers. For every book you buy at BookBar, a fairy gets its wings.1

Be sure to RSVP for Reading no. 9 on 9 March 2019, at BookBar, 7pm. For March’s reading, we’ll hear from authors Molly Tanzer and Laurence MacNaughton. Molly will read from her newest, Creatures of Want and Ruin, while Laurence will share the third in his Dru Jasper series, No Sleep Till Doomsday.

Check back for more information, follow developments on Facebook, join the Meetup, or better yet sign up for the mailing list. Learn more about the Reading Series.

[image error]A full house and a captivated audience.[image error][image error]Rebecca Hodgkins reads.[image error]Lou J. Berger reads.[image error]Rebecca Hodgkins listens in.[image error][image error]Jamie Ferguson reads.[image error]Lou J. Berger reads.[image error]Jim LeMay listens intently.[image error][image error]Jamie Ferguson

[image error]A Fistful of Dinosaurs.[image error]Rebecca Hodgkins.[image error]Reading no. 8.[image error]Lou J. Berger.

The post Reading no. 8 — Rebecca Hodgkins, Lou J. Berger, & Jamie Ferguson appeared first on J.L. Forrest.

Reading no. 7 — Carrie Vaughn & Betsy Dornbusch

Carrie Vaughn

& Betsy Dornbusch

Authors Betsy Dornbusch and Carrie Vaughn joined me for the Denver Science Fiction and Fantasy Reading Series no. 7. Carrie was the Series’s first reader, in November 2017, and it was a pleasure to have her back. In a huge year, Carrie won the Philip K. Dick Award for Bannerless, which she read at Reading no. 1, and she released book two in that series, The Wild Dead.

For this reading, Carrie shared passages from her series-related short story, “Where Would You Be Now?”, published by Tor. Betsy read from her novel The Silver Scar.

As always, BookBar gave us the most marvelous home for the evening. Books were sold and signed, and we had a great time. Go to BookBar, buy books, and support local and independent booksellers. For every book you buy at BookBar, a fairy gets its wings.1

Be sure to RSVP for Reading no. 8 on 12 January 2019, at BookBar, 7pm. For January’s reading, we’ll once more have editors Jim LeMay and Chuck Anderson from Mad Cow Press. For something different and fun, we’ll have three authors from the anthology Fistful of Dinosaurs—Lou Berger, Rebecca Hodgkins, and Jamie Ferguson. What’s not to love about some well-crafted dinosaur stories?

Rawr!

Check back for more information, follow developments on Facebook, join the Meetup, or better yet sign up for the mailing list. Learn more about the Reading Series.

[image error]Carrie Vaughn.[image error]Carrie Vaughn.[image error]Carrie Vaughn.[image error]Betsy Dornbusch.

[image error]Betsy Dornbusch.[image error]Carrie Vaugn’s “Where Would You Be Now?” Illustration by Jon Foster.[image error]Carrie Vaughn & Betsy Dornbusch at BookBar.[image error]Carrie Vaughn.[image error]Betsy Dornbusch.[image error]The Silver Scar by Betsy Dornbusch.[image error]The Wild Dead by Carrie Vaughn.

The post Reading no. 7 — Carrie Vaughn & Betsy Dornbusch appeared first on J.L. Forrest.

September 9, 2018

Reading no. 6 — Rebecca Roanhorse & Lauren C. Teffeau

For the Denver Science Fiction and Fantasy Reading no. 6, I had the great pleasure of hosting authors Rebecca Roanhorse and Lauren C. Teffeau. Rebecca read a potpourri from her short fiction, including “Welcome to Your Authentic Indian Experience ”. She also read from Trail of Lightning, and she gave us a preview of its sequel. Lauren captivated the room with the opening chapter of Implanted.

”. She also read from Trail of Lightning, and she gave us a preview of its sequel. Lauren captivated the room with the opening chapter of Implanted.

As it has before, BookBar gave us the most marvelous home for the evening. Books were sold and signed, and we had a great time. Go to BookBar, buy books, and support local and independent booksellers. For every book you buy at BookBar, a fairy gets its wings.1

Be sure to RSVP for Reading no. 7 on 10 November 2018, at BookBar, 7pm. November’s reading will feature author Carrie Vaughn, who’ll be returning for the one-year anniversary of the Reading Series. Since we last saw Carrie, she published her followup to Bannerless, titled The Wild Dead. Oh yeah, and she won the Philip K. Dick Award. We’ll also have Betsy Dornbusch with us. Check back for more information, follow developments on Facebook, join the Meetup, or better yet sign up for the mailing list. Learn more about the Reading Series.

[image error] Lauren C. Teffeau [image error] Lauren C. Teffeau [image error] Lauren C. Teffeau [image error] Lauren C. Teffeau [image error] Lauren C. Teffeau [image error] Rebecca Roanhorse [image error] Rebecca Roanhorse [image error] Rebecca Roanhorse [image error] Rebecca Roanhorse [image error] Rebecca Roanhorse [image error] Rebecca Roanhorse [image error] Rebecca Roanhorse [image error] Rebecca Roanhorse [image error] Reading Series no. 6 [image error] Reading Series no. 6 [image error] Reading Series no. 6 [image error] Rebecca Roanhorse [image error] Trail of Lightning by Rebecca Roanhorse [image error] Lauren C. Teffeau [image error] Implanted by Lauren C. Teffeau

The post Reading no. 6 — Rebecca Roanhorse & Lauren C. Teffeau appeared first on J.L. Forrest.

July 15, 2018

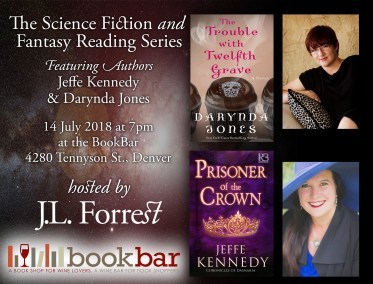

Reading no. 5 — Darynda Jones & Jeffe Kennedy

Science Fiction and Fantasy Reading no. 5

Darynda Jones & Jeffe Kennedy

For the Denver Science Fiction and Fantasy Reading no. 5, I had the great pleasure of hosting bestselling authors Darynda Jones and Jeffe Kennedy. Darynda read from the latest in her Charley Davidson series, The Trouble with Twelfth Grave. An opening scene with a twist, Darynda’s storytelling had everyone bemused and laughing. Jeffe read from Prisoner of the Crown, a decidedly darker tale which captivated the room.

As it has before, BookBar gave us the most marvelous home for the evening. Books were sold and signed, and we had a great time. Go to BookBar, buy books, and support local and independent booksellers. For every book you buy at BookBar, a fairy gets its wings.1

Be sure to RSVP for Reading no. 6 on 8 September 2018, at BookBar, 7pm. September’s reading will feature authors Rebecca Roanhorse and Lauren Teffeau. Check back for more information, follow developments on Facebook, join the Meetup, or better yet sign up for the mailing list. Learn more about the Reading Series.

The post Reading no. 5 — Darynda Jones & Jeffe Kennedy appeared first on J.L. Forrest.