Lisa Borders's Blog

November 26, 2013

Blog in Progress: Lessons from Little America (Or, How to Survive – and Thrive – on a DIY Book Tour)

[image error]

1. Publish with a mighty independent press that creates a beautiful book whose cover warms your heart every time you look at its green and yellow glow. It is very important that you feel this way, as there will be days you’ll need that green and yellow glow to carry you through eleven hours of driving.

2. Find out your publisher’s budget for a book tour, and then figure out how much you can afford to spend yourself. Even if you’ve published with a major house, unless your last name is Kardashian, the amount you can afford to spend yourself will pretty much be your budget.

3. Book many dates in the state where your book is set, and plan for your boyfriend to drive you around that entire state. This may put a strain on your relationship, but it will rest you up for the legs of your book tour when you’ll need to drive. And, let’s face it, the first months after your book comes out are all about you! Except for when you’re taking out the trash, or changing the cat litter, or coordinating doctor visits long distance for your elderly mother. Bonus points if you do any of those things while wearing a sparkly dress within an hour of leaving for or returning home from a reading.

4. Book at least part of your tour with another recently-published author, preferably a good friend, and definitely someone with similar taste in music. When hauling ass from Oakland, California to Portland, Oregon, you want someone who shares your excitement at listening twice in a row to REM’s “Little America” or Neko Case’s “Hold On Hold On.” You don’t want someone who might ask to listen to Air Supply instead. (If you’re an Air Supply fan, simply reverse the above statement.)

5. Also paramount to the travel dynamic: be sure that, whether your travel companion is male or female, you feel comfortable discussing biological functions such as farting, burping, and the need for salty snacks while menstruating. These things will all come up, and not being able to stop for those Kettle chips RIGHT NOW could prove disastrous for you both.

6. When spending the night in a sketchy motel, do not spend two hours wishfully googling nearby hotels while your fellow author sleeps. Especially do not do this if you already feel guilty that your fellow author did so much of the driving because you nearly had a panic attack trying to navigate the windy roads near Mount Shasta, and so there is no way you will wake him up and ask to go to a motel that does not smell of Lysol and floral air freshener with a fungal undertone.

7. When your fellow author says the next morning that he does not smell the fungal undertone, but you are both able to laugh about the Hawaiian-shirted guy at the front desk the previous night – the one who told the bleary-eyed two of you about his upcoming dental work in unsolicited detail, using words like “scaling” and mentioning his own bad breath – when that happens, feel very, very grateful that the only thing you’ve really disagreed on in a week of constant travel togetherness is the smell in a motel that, happily, you will never visit again.

8. If traveling for two weeks, do not pack ten dresses/skirts and only two pair of pants, one of these being the jeans you will wear in the car every single day. By the fourth city, you will no longer have the energy to put on tights. By the fifth city, you will no longer be able to find the tights in your suitcase.

9. If traveling for two weeks, do not pack one huge suitcase that weighs as much as a Saint Bernard dog, one overflow suitcase, one laptop bag and one giant purse/bag. Especially if you can barely lift the Saint Bernard, and especially if your fellow author is kind enough to lift the Saint Bernard for you when you can’t. You will feel selfish and high maintenance for the entire trip, and you will lose the necessary clout for a motel fungal smell opt-out (see #6).

10. Recognize that having a book published is an enormous honor, and the ability to take time off from day jobs to promote said book is a gift. Be as grateful to the three people who show up for that one reading as you are to the forty who showed up for that other reading. Don’t ever publicly complain about your good fortune. EVER. Because there are lots of people out there who would love to have a book published, would love to have a book tour, would love to just have a couple of weeks off from their jobs, even. Yes, a book tour is work, but it’s work of the most wonderful sort. It’s not a shift on an assembly line, or physical labor in the hot sun or freezing cold. Being a writer can be hard, and frustrating, and lonely at times, but this is the awesome part. Enjoy it. Respect it.

Tweet

October 22, 2013

Blog in Progress: Artist Appreciation

On a Sunday night in March of 2001, I watched the Academy Awards telecast alone in my apartment. I had a first novel that I’d been unsuccessfully shopping around to agents for the past two years; I’d started entering it in a few small press contests as well. In five months I would learn that I’d won one of those contests, but I didn’t know it on that Oscars night. All I knew was that I spent a lot of time alone in my apartment and had little tangible success to show for it. I’d been thinking, lately, that if I couldn’t publish my book I might give up writing altogether.

I’ve watched the Oscars every year since I was a kid, but I’d always watched for the glamour, the fashion, the celebrity sightings. It was a fun diversion, and I expected no more on that night in 2001. And then, Steven Soderbergh won as Best Director for the film Traffic, and his speech included these two sentences:

“What I want to say is – I want to thank anyone who spends part of their day creating. I don’t care if it’s a book, a film, a painting, a dance, a piece of theater, a piece of music… anybody who spends part of their day sharing their experience with us. I think this world would be unlivable without art, and I thank you.”

What he said – not just the content, but the clearly heartfelt delivery – made me cry. Hard. I felt like he was talking directly to me, and I sat on my couch in front on my TV, sobbing. Steven Soderbergh was telling me, Lisa Borders, the unpublished novelist, that what I did mattered.

It sounds silly, I know, but something changed in me that night. And it wasn’t about perspective, that he’d made me see the act of creating as more valuable than the finished product; it was about connection. I realized that there were people out there who actually cared whether people like me made art. And by “people like me,” I mean people coming from circumstances where art was seen at best to be a frivolous diversion – a pursuit of the wealthy, not something the rest of us could reasonably expect to do.

Everyone in the arts knows how difficult it is to make a living as any kind of artist in this country, and of the necessity for either family money, a generous grant, a well-employed spouse or a day job. But equally important – and less acknowledged, I think – is the need for emotional support.

I’ve been thinking about this a lot over the past week, as my second novel went forth into the world. Newtonville Books was packed on the night of my launch reading; many of the people there were familiar faces from Grub Street, an organization I think of as my home, my family. It was immensely touching and gratifying, the support and love I felt that night, and have continued to feel over the past week. But I didn’t always have this level of support, and my mind keeps drifting to those who might not.

We have Grub here in Boston, and people in cities like New York and Minneapolis have access to organizations like Sackett Street Writers and The Loft; but how does a writer, sculptor, or dancer in rural Texas, the vast coal-mined stretches of Pennsylvania, or a working class town in New Jersey find someone to say, “Thank you for making art?”

Recently my boyfriend relayed to me a conversation he had with his teenage niece, who is equally interested in – and equally good at – art and math. He gave her pragmatic, loving advice about the difficulty making a life as an artist and the need for a bread-and-butter career. Jeff is an artist himself, and, as he put it to me, has “first-hand knowledge about how much the profession can kick you around.”

He wasn’t dissuading her from art, but wanted her to know what she would be getting into if she pursued it. I can’t argue that anything he said to her was wrong, or that it wasn’t good advice, but his words stung me, and it took some time to figure out why.

It was simply this: I think the world needs more artists, not less. We especially need his niece’s art, and it’s needed precisely because hers is the voice that may not be strongly encouraged. That doesn’t mean she shouldn’t listen to her uncle’s sound advice. She must be able to support herself. But I also think she shouldn’t give up on her art.

I want to say to her, and to everyone like her, what Steven Soderbergh said that night twelve years ago: thank you for making art. If that’s you, reading this, feeling alone and wondering if you should keep at it: Thank you. If you’re feeling like you’re working in a vacuum, wondering if anyone cares: I care. And if you’re suffering a lack of encouragement from your family, your community, keep at it even more, for yours is the kind of voice I want to read, the kind of art I want to see. What you’re doing is not “a delusion, an unfortunate habit,” as Lorrie Moore jokingly wrote in a short story called “How to Become a Writer” – a story I reread at least once a year, because it makes me feel less alone.

What you’re doing, no matter how raw in form, is art. And it matters.

Tweet

September 24, 2013

Blog in Progress: Macaroni and Gravy

By Lisa Borders

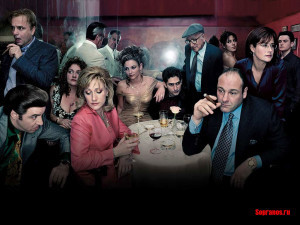

Until this summer, I’d never seen an episode of The Sopranos. I had a huge resistance to watching the series, despite the fact that so many of my friends had told me how terrific, ground-breaking, well-written it was. Part of my resistance, I think now, was that during much of the time the show was on the air, I was writing a novel that was set in New Jersey. And while my rural South Jersey setting is an entirely different world from The Sopranos’ gritty North Jersey, on some level I probably didn’t want that vision of New Jersey competing with my own.

This summer, not long after the death of actor James Gandolfini, who played Tony Soprano, I decided to give the show a try. I was hooked from the first episode, and ran through all six-plus seasons in a frighteningly short span of time. The controversial final episode intrigued me so that I found myself googling analyses and theories; what I read made me want to go back and watch the pilot episode again. Soon, I found myself re-watching the entire series.

There are television shows I love and have watched over and over: various Star Trek franchises, Gilmore Girls, Buffy the Vampire Slayer, Freaks and Geeks. In most cases it’s because I enjoy being in the world of the series, or identify with the characters. But it’s rare for me to rewatch a television series in the way I reread a novel I’ve loved, for craft. Yet that’s what I found myself doing with The Sopranos.

I certainly don’t like hanging out at the Bada Bing strip club the way I enjoy visiting the Gilmore Girls’ Stars Hollow, yet I find myself just as engrossed in The Sopranos on second viewing as I was the first time around. This is largely because so much is happening in The Sopranos from a dramaturgical standpoint that I’m catching things I missed on first viewing: symbolism, thematic connections, subtly ironic lines of dialogue.

The Sopranos, in fact, uses a surprising number of novelistic tools to tell its story – elements of craft that a feature-length screenplay, with its necessary compression, could never accommodate. I’d argue that the series has much more in common with a novel than it does with a screenplay, and that it has much to teach the novelist.

Here, then, is my list of the top five craft lessons The Sopranos can teach novelists. Please note that this list is rife with spoilers, for those of you who haven’t seen the series. (And if you haven’t, stop reading this post, start watching the show now, and return to the list in three months.)

1. Sometimes difficult narrative problems require ingenious, risky solutions. The Sopranos is not so much a story about the Mafia as a study of an antihero’s interior life, and his relationships with others. If series creator David Chase had been writing a novel, he might have chosen a first person or close third person point of view to convey Tony’s inner life. But there is no way to access a character’s direct thoughts in a work written for the screen, and this must have posed a huge dilemma for Chase: how could he possibly tell the viewer everything he, the writer, knew about Tony? Sometimes films use a voice-over narration technique to convey a character’s thoughts, but this often comes across as artificial and cheesy, and I’m glad Chase didn’t do that. Instead, he took a giant risk: he had Tony Soprano regularly see a psychiatrist. I can just imagine a disbelieving network executive at a pitch meeting: “This guy is the Mob boss of North Jersey, but he goes to see a shrink? No one will buy that!” And indeed, Chase’s device requires a huge suspension of disbelief on the viewer’s part. To render it more plausible, Chase gives Tony Soprano severe panic attacks that have caused him to pass out – in front of his business associates, in a world where showing weakness can be deadly. This becomes evident by the end of the pilot episode, and makes Soprano’s sessions with his shrink infinitely more believable.

2. Counterpointed characterization. The great Charles Baxter defines counterpointed characterization as what happens in a work of fiction when “certain kinds of people are pushed together, people who bring out a crucial response to each other.” There are many examples of counterpointed characterization in The Sopranos, but perhaps the best – and most extensive – is Tony’s relationship with his psychiatrist, Dr. Jennifer Melfi. It’s no accident that Dr. Melfi is a woman; a female shrink was vital to elicit some of the buried sides of Tony that I’m certain Chase wanted the viewer to see. As the series unfolds, Dr. Melfi is one of only two female characters in a position to challenge Tony’s antiquated views about women and about different races and cultures (the other is his college-educated daughter, Meadow). While Dr. Melfi challenges Tony, she also brings out aspects of his personality we might never be able to see otherwise; and because we see Dr. Melfi’s sessions with her own psychiatrist, we also see the other side of this counterpoint, elements of her character that treating Tony has brought out.

3. Shifts between scenes/chapters and the passage of time. Novelists often struggle with how to move from scene to scene or chapter to chapter, especially when a significant amount of time has elapsed between the two. The best way to handle this is often to just jump right in to the next scene, and work a clue or two within the action as to how much time has elapsed. Chase often uses this technique to great effect. At the end of Season 4, for example, Tony’s sister Janice and Bobby Baccalieri have started dating. In the first episode of the next season, Janice is at Bobby’s house preparing dinner. It quickly becomes clear that she and Bobby are hosting dinner for Tony and his children – and, when Janice says “This is my house, Tony” – that Janice and Bobby are now married. Chase doesn’t spell it out, but he does convey the passage of time while staying in scene and not over-explaining.

4. To know your beginning, you have to know your ending. When I teach a lesson in novel openings, I talk a lot about overall structure and the novel’s climax. Watching the series finale and then rewatching the pilot episode immediately afterward, I was struck by the extent to which the ending of The Sopranos addressed themes, tensions and characters introduced in the pilot. To accomplish this, series creator Chase must have had the entire story arc for all the seasons mapped out from the beginning, just as a novelist maps out chapters, once a first draft is complete and the revision process begins.

5. Great works of art should provide some resolution while also providing room for interpretation. The final season of The Sopranos unfolds like the end of a Shakespearean tragedy, as many brewing issues in this violent world come to a head. Tony’s son, A.J., who struggles with depression for much of the series (as does his father), attempts suicide. A simmering dispute with the New York mob erupts in the killings of several of Tony’s key men, and sends Tony into hiding.

In the final episode, the main threat from the New York gang has been killed, and Tony feels he has struck a deal with the remaining men. A.J. has a girlfriend and seems to be doing better; daughter Meadow becomes engaged; Tony and his wife Carmela, often at odds, seem to be in a good place. As Tony comes out of hiding and the family meets at a restaurant, it seems many of the main characters’ story lines have some resolution. And then … Chase seems to end the episode in mid-scene. The screen goes black as Tony looks up at the front door of the restaurant, where the viewer knows Meadow is about to walk in. The black screen is held for about ten seconds, with no music, no sound. Then the credits roll.

On first viewing, that last scene from the series finale reminded me of the ending of David Foster Wallace’s Infinite Jest in its apparent lack of resolution. I felt the cut in mid-scene underscored the ongoing nature of the danger Tony is in. Yes, he’s cheated death again, as he has many times before over the course of the series, but it doesn’t matter if he’s killed in this restaurant, on this night; he most likely will be killed eventually. It’s an implied ending, an ending the viewer must project.

But there’s another possible interpretation, one that I’m reluctantly coming around to believing: that Tony is killed at the moment he looks up at that door, that the screen goes black and silent because he has died. There are numerous shots from his point of view in this last scene of the series, and the final shot is from his point of view as well. An excellent explanation of this interpretation, walking the viewer through the final scene, can be found here.

What were Chase’s intentions for that final scene? It doesn’t matter. What matters is that he created an ending that resounds with all that came before, but leaves the viewer wanting to know more, interpreting and debating. As a novelist, it’s the kind of final scene I aspire to; and it’s a fitting ending for a series that is, in my opinion, a work of art.

Tweet

August 27, 2013

Blog in Progress: Audience Awareness

By Lisa Borders

I’ve never had my own blog. I’ve also never kept a journal, or the kind of diary Marcia Brady famously lost. I’d sometimes receive them as gifts when I was a kid, those little diaries with leatherette covers and a tiny lock on the front; after a week, my entries would taper off. After a month, I was done.

And yet, I’m a big fan of recording the minutiae of daily life. I composed bad confessional poetry from the time I was seven years old until I was about twenty. After that, I wrote long letters to friends. In the early days of the internet, I found my way to message boards that I posted on regularly. And now, I spend enough time on Facebook that my friends tease me about it.

It was never the idea of journaling per se that I found distasteful; for me, the problem was the notion of audience. For whom, exactly, was I writing these journal entries? Myself at an older age? The historians who would surely want to read my personal diaries after I became a famous writer (ha, ha)?

When the question of launching my own blog came up as I prepared for the publication this fall of my second novel, The Fifty-First State, I wondered again: who is the intended audience of this blog? My interests are wide-ranging and not just related to writing. I could imagine having a blog about writing, one about music, perhaps another about animals and animal welfare issues. When I reached the point where I had enough blog ideas for days of the week, I knew things had gotten out of hand – at least, if I wanted to hold on to the income-generating jobs that keep a roof over my head.

So when the opportunity to write a monthly blog for Grub Street came up, I jumped at the chance. Finally, a clear audience: other writers! I’m calling it Blog in Progress, partly as an homage to the Novel in Progress classes I launched at Grub Street years ago, and partly because for me, blogging regularly is a work in progress. Each month, I will address a topic related to fiction writing, must-read books, or the publishing world.

Which brings me back to this month’s topic: the notion of audience. When I started writing and submitting my first short stories, I didn’t think at all about audience. I wrote what delighted me, and then I revised to make the stories and characters work. Somehow, this haphazard process landed my stories in a few literary journals, so apparently my work did target that audience.

Once I started writing novels, the stakes became higher. The structure of my first novel, Cloud Cuckoo Land, was loosely based on Willa Cather’s The Song of the Lark. The first part of Cloud Cuckoo Land was set in Texas and based on my narrator’s early life. The second part took place in Philadelphia, where she scrambled to find her footing as a musician. In Part III, she began to succeed in her chosen field as she overcame her difficult early years.

The problem with this structure was – you guessed it – audience. As I sent the manuscript to agents, I heard from some that if I rewrote the book and set it all in Texas, they’d consider taking me on as a client; others said the opposite, that they preferred the grittier sections set in Philly and wanted the whole book to take place there. I realized there was a tonal shift in Part II of the book, but I felt that Cather’s novel, a beloved favorite of mine, did the same thing. I decided to keep the book the way it was and start targeting small press contests. Eventually, I won one, and the book was published in 2002.

But it wasn’t until I had a long discussion with a generous editor at a large publishing house that the notion of audience – and my utter disregard for it in writing Cloud Cuckoo Land – really clicked for me. This editor had stumbled upon my book, fallen in love with it, and tried, unsuccessfully, to get her press to buy the paperback rights. When I had lunch with her, she explained to me that the problem had been marketing. The Texas sections, she said, had the kind of sass and sensibility associated with Southern Fiction. The Philadelphia sections, with their backdrop of the alternative rock scene of the 1980s, would appeal to rock fans and more urban readers. The novel seemed to target two entirely different audiences. As a reader, this editor herself hadn’t found the shift to be a problem; but from a marketing perspective, the book was seen as too great a challenge.

I was, of course, terribly disappointed by this news, and at first, I was even a little angry. Why couldn’t the audience for my novel simply be people who like to read? Were modern readers so unwilling to step outside their comfort zones that they couldn’t handle a book that went somewhere unexpected? Why had this been okay in Willa Cather’s day, but not now?

With time and distance, though, I have more sympathy for the perspective of the marketer. It’s always an uneasy relationship, this one between art and commerce; but unless we’re writing in private journals, only for ourselves, we writers must take audience into account. In Cather’s time, publishing houses did not have so many other forms of entertainment competing for the public’s attention, and as a result, authors could take more artistic liberties and still have a good shot at selling their novels. Today, more than ever, an author doesn’t have that luxury.

This doesn’t mean that a writer can’t get highly literary, or even ground-breaking, work published today. As both a writer and a reader, I’d hate to live in a world where that kind of fiction wasn’t available. But it will have a smaller audience, and writers need to know that when they make certain stylistic choices, they may be narrowing their audience. I always advise my students to make the best choices for the book itself, the ones necessary to tell the story; but to be aware, as those choices are made, of how they are affecting the potential audience.

So how does a writer with a manuscript in progress sort out this notion of audience? I’d say that unless one is writing in a genre where the audience is clearly defined – young adult, perhaps, or mystery – I wouldn’t put too much thought into audience until the revision process begins. The first draft stage is usually quite messy, at least for me; the writer may try, and fail, at a variety of plot twists, narrative voices, structures before completing something that seems to have a beginning, a middle and an end. It’s in the later drafts, as the writer commits to choices taking the book in a certain direction, that the notion of audience should start being considered.

I’d love to hear in the Comments section about whether, and at what point, you, dear writers, take audience into account. And I will keep my Grub students, as well as writers outside of Boston, in mind as I continue this Blog in Progress.

Tweet