Cate Parke's Blog

April 3, 2021

Once Upon A Duke -- The Lost Prince

This is Carlisle Cathedral, located in the far northwest of England, in Carlisle (where else). The cathedral was begun in 1122, during the reign of Henry I, and represents the Norman style of architecture. Over time, the red sandstone of which the cathedral is built, has discolored to almost black in several spots. The building was refurbished under the reign of Edward I during the later 13th and early 14th centuries.

This is Carlisle Cathedral, located in the far northwest of England, in Carlisle (where else). The cathedral was begun in 1122, during the reign of Henry I, and represents the Norman style of architecture. Over time, the red sandstone of which the cathedral is built, has discolored to almost black in several spots. The building was refurbished under the reign of Edward I during the later 13th and early 14th centuries.So what is the significance of this building? Well, it's beautiful to begin with. Here are some pictures of the interior. Look at that marvelous ceiling. Also, notice how narrow the building is.

In the 13th century, the choir of the cathedral was rebuilt in the Gothic style, wider than the original and on a different axis. However, the new work was severely damaged by a fire in 1292, and the work was re-started. By 1322 the arcades and the easternmost bay were complete, with the elaborate tracery and glass of the east window being in place by about 1350. The upper stages of the walls were finished, probably by the architect John Lewen who died in about 1398. The Gothic arcade has richly moulded arches with dog's tooth decoration, and the twelve capitals are carved with vegetation along with small lively figures representing what is known as the labours of the months.

Here's another picture of that ceiling:

The view from the 14th-century choir looking towards the east window – one of the finest examples of Flowing Decorated tracery in England. What's the significance of this place? Actually, it's featured in my next book, called Once Upon a Duke--The Lost Prince. Carlisle Cathedral is the place Prince Edmund was married, his bride a beautiful young Scottish princess whose name is Alys. It is also where King Edward I confers a ducal crown upon him.

The view from the 14th-century choir looking towards the east window – one of the finest examples of Flowing Decorated tracery in England. What's the significance of this place? Actually, it's featured in my next book, called Once Upon a Duke--The Lost Prince. Carlisle Cathedral is the place Prince Edmund was married, his bride a beautiful young Scottish princess whose name is Alys. It is also where King Edward I confers a ducal crown upon him.The book is what is known as an Alternative History. The prince had been given the name of Edmund at birth. So, what's the rest of the rest of Edmund's story? Well, you'll simply have to wait for the book!

Published on April 03, 2021 11:19

December 18, 2019

Christmas Giveaways--Galore!

My first three books are all on sale this month! I hope you'll take the opportunity to load up on them. Richard Berkeley's Bride is on sale at Amazon.com and available through the Love Kissed Historical Romance giveaway which is available through December 31st.

My first three books are all on sale this month! I hope you'll take the opportunity to load up on them. Richard Berkeley's Bride is on sale at Amazon.com and available through the Love Kissed Historical Romance giveaway which is available through December 31st.Dreams Within Dreams, Book Two in the series, and Patriot's Dreams, Book Three, are also on sale at Amazon.com and available through the 99 books @ 99 cents Holiday Book Fair Giveaway. It runs only from December 18th through the 21st.

Don't miss my favorite authors, Cathy MacRae, Dawn Marie Hamilton, and Lane McFarland while you're there. They all have books available in both these giveaways. Don't miss the chance to load up on books by authors you may never have met. See you all at the Giveaways!

Merry Christmas to All!

Published on December 18, 2019 06:09

December 5, 2019

Christmas Giveaway from Love Kissed

Check out the December Historical Romance Giveaway! 12/1 - 12/31! Our Romance Authors in this promotion are featuring their Historical Romance Books. In addition to bringing you 120 featured books, we've pooled our funds to offer an amazing giveaway! You can enter to win 1 of 6 $50 Amazon Gift Cards. It's just our way of thanking our loyal readers.

Check out the December Historical Romance Giveaway! 12/1 - 12/31! Our Romance Authors in this promotion are featuring their Historical Romance Books. In addition to bringing you 120 featured books, we've pooled our funds to offer an amazing giveaway! You can enter to win 1 of 6 $50 Amazon Gift Cards. It's just our way of thanking our loyal readers.

Published on December 05, 2019 04:53

December 1, 2019

A Christmas Giveaway!

Don't you just love these? Richard Berkeley's Bride is part of it. Now's the time to take advantage of an updated version. Here are the details:

Don't you just love these? Richard Berkeley's Bride is part of it. Now's the time to take advantage of an updated version. Here are the details:Check out the December Historical Romance Giveaway! 12/1 - 12/31! Our Romance Authors in this promotion are featuring their Historical Romance Books. In addition to bringing you 120 featured books, we've pooled our funds to offer an amazing giveaway! You can enter to win 1 of 6 $50 Amazon Gift Cards. It's just our way of thanking our loyal readers. lovekissedbookbargains.com/2019/11/29/december-historical-giveaway/

Don't miss this unique opportunity. Put books on your Christmas list today!

Published on December 01, 2019 04:26

July 9, 2019

Goodnight Sweet Friend

Gaius Germanicus Catullus Gaius came to live with us on July 4, 2008. He was our Independence Day celebration. He was eight weeks old.

Gaius Germanicus Catullus Gaius came to live with us on July 4, 2008. He was our Independence Day celebration. He was eight weeks old. If you look close beneath his upper lips you can see fangs distending from below it. He had a glorious set. I called him my Sabre-toothed Siamese cat. You should him before he lost his kitten fangs. The poor little fellow had four sets of fangs in his little mouth--all impressive.

Gaius came home to a Labrador Retriever named Nink--who adored him. He had taken to sleeping at the foot of our bed on his first night with us, but gravitated down to Nink's bed within a couple of weeks. She kept him toasty warm in the night. Both Nink and Gaius would push the drapes apart every morning and stare out the windows at the bunnies playing chase in the circle inside our driveway. After several years we replaced the drapes with wooden blinds and Gaius still felt compelled to look outside. Hm-m . . . how does a cat manage such a feat? Solution! We pull the blinds open with one set of claws and get between the blinds and the windows! Easy peasy. And noisy!

Gaius Germanicus Catullus, 8 weeks old

Gaius Germanicus Catullus, 8 weeks old You've met Gaius before. Here he is on his first day at our house. So little and disconcerted. But that was just Day One. Things changed fast!

Kitten toys.

Kitten toys. See what I mean? Our little Siamese thief absconded with every blessed scrap of paper in the house and used them for toys. Regular kitten toys? Pffft!

My writin' buddy.

My writin' buddy. Gaius decided he wanted to help write my book(s). You might think cats don't have much to say. You would be wrong. Siamese cats never stop talking.

Mr. Inspector

Mr. Inspector You've seen this, too. He made the leap to the top of the cabinets as recently as last month. I never failed to worry that he might decide to try an Evil Knieval stunt and try to cross the tops of the window frames. At 1/2 inch wide -- I'm thinking he couldn't make it.

My friend, Gaius

My friend, Gaius Gaius went to sleep for the very last time today. He was precisely eleven years, 2 months old today.

Gaius is even a character in my last book, Alex Campbell.

This is his eulogy:

In Memoriam

To Gaius Germanicus Catullus

May You Rest In Eternal Peace

Goodnight my sweet little Gai.

We will love you and miss your rumbling purrs and grumbling meows forever.

9 May 2008 ~*~ 9 July 2019

Thank you for sharing your eleven short, precious, and thoroughly delightful years with us.

~Dad, Gretchen, and me

This page will be added to the book.

Published on July 09, 2019 16:17

June 7, 2019

Revenge is S-w-e-e-t!

Have you ever lent a book to a friend . . . who never returned it? Have you ever lent a book to a friend . . . who marked up your book, or let the children tear pages, or worse, let the dog chew on the bindings? Here's your revenge: Remind them of what awaits them if you don't receive it back from them in the same condition in which you lent it!

The following is copied from the Medieval Manuscripts and Earlier website of the Medieval Manuscripts blog

Enjoy!

Angel of Death Conquered - Rome, Italy

Angel of Death Conquered - Rome, Italy

The Curse of the Spiritual Sword

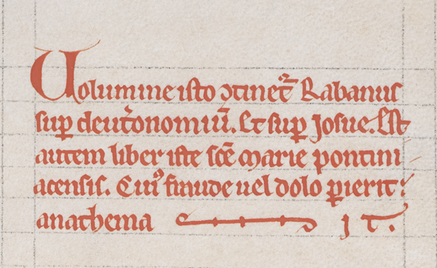

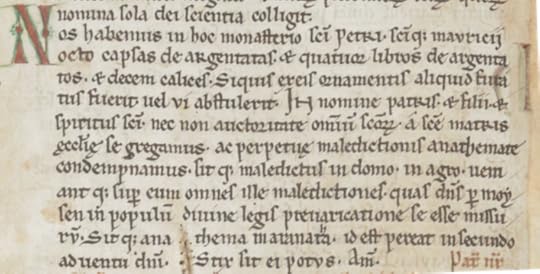

We have previously reported about our fascination with medieval book curses, added in monastic libraries to ward off thieves and warn careless users. Book curses typically state that those who stole or damaged a book would be spiritually condemned, often including the Greek-Aramaic formula ‘Anathema Maranatha'. For example, during the 12th and 13th centuries monks at Reading Abbey systematically added such curses to their manuscripts containing biblical commentaries (examples include Add MS 38687, Harley MS 101 and Harley MS 1246).

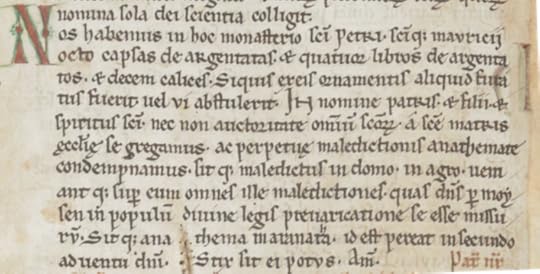

Reading Abbey’s book curse in a commentary on Deuteronomy and Joshua (1st quarter of the 13th century): Add MS 38687, f. 150r

Reading Abbey’s book curse in a commentary on Deuteronomy and Joshua (1st quarter of the 13th century): Add MS 38687, f. 150r

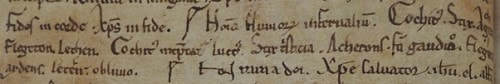

We would like to share some new findings that will enable you to protect your favourite books, as well as other prized possessions. One example comes from the so-called ‘Noyon Sacramentary’ (Add MS 82956). This 10th-century manuscript, produced by the monastic community at Noyon Cathedral in northern France, contains masses and prayers for blessings and ceremonies. The manuscript opens with a wrathful curse that would bring down a series of spiritual punishments upon those who stole from or committed any other crime against Noyon Cathedral.

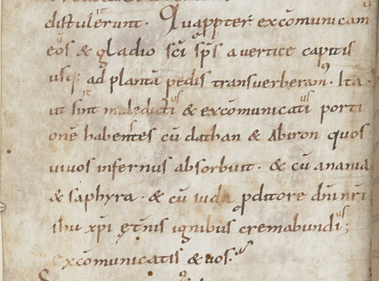

Noyon Cathedral’s ‘Curse of the Spiritual Sword’ (4th quarter of the 10th century): Add MS 82956, f. 1v

Noyon Cathedral’s ‘Curse of the Spiritual Sword’ (4th quarter of the 10th century): Add MS 82956, f. 1v

The Noyon Cathedral curse begins: ‘excommunicamus eos et gladio sancti spiritus a vertice capitis usque ad plantam pedis transverberamus’ (‘We will excommunicate them and cut through them with the sword of the Holy Spirit, from the top of the head to the sole of the feet').

It then declares that book-thieves would be condemned to burn in the eternal fire of Hell together with Judas Iscariot, perhaps because they, like Judas, committed betrayal for material gain. Finally, to top it off, these thieves were to remain in the darkness of Hell where they would keep the devil company.

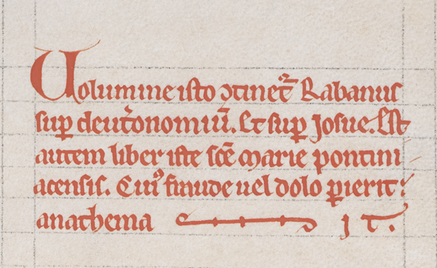

Perhaps an even more powerful curse for protecting your belongings comes from a 12th-century lectionary (containing readings from the Gospels for the Mass) from the Benedictine abbey of Tholey in western Germany (Add MS 29276). The curse is preceded by an itemised list of the monastery’s relics and sacred objects: ‘We have in this monastery of St Peter and St Mauritius eight bookcases of silver, four books of silver, and ten chalices’. Protecting this treasure is a curse that the community would collectively cast upon anyone who stole from the monastery:

‘a sancte matris ecclesiae segregamus ac perpetuae maledictionis anathemate condempnamus . sit que maledictus in domo . in agro . veniantque super eum omnes ille maledictiones . quas dominus per moysen in populum divin[a]e legis prevaricatione se esse missurum. Sitque anathema maranatha . id est pereat in secundo adventu domini. Stix sit ei potus. Amen’.

‘We will segregate him from the mother church and condemn him with the eternal curse of anathema: may he be cursed in the house and on the land, and let all the curses that the Lord cast through Moses onto the transgressors of the Divine Law come upon him. May he be anathema maranatha. That means: may he be damned at the Second Coming of Our Lord (the Last Judgement); may the Styx be his drink. Amen’. Tholey Abbey’s ‘Styx-Curse’ (c. 1100–c. 1175): Add MS 29276, f. 162v)

Tholey Abbey’s ‘Styx-Curse’ (c. 1100–c. 1175): Add MS 29276, f. 162v)

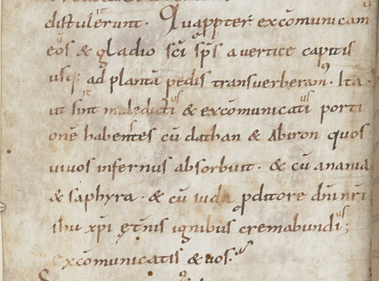

This curse encompasses both the eternal sentence to Hell, at the Last Judgement, and the Styx, the principal river of the Underworld. While it may seem unexpected to find a medieval monk referring to the Styx, monasteries gained knowledge about the Underworld through their copies of works such as Virgil's Aeneid. For example, in a 12th-century theological miscellany from the Cistercian abbey of Thame in Oxfordshire (Burney MS 357), the Styx is listed as one of the rivers in Hell, and its name is defined as ‘sadness’ (tristicia).

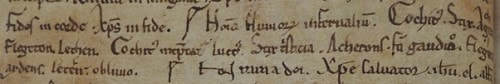

The ‘Stix’ among the ‘Names of the Infernal Waters’ (Nomina Humorum Infernalium) (1st half of the 12th century): Burney MS 357, f. 4v

The ‘Stix’ among the ‘Names of the Infernal Waters’ (Nomina Humorum Infernalium) (1st half of the 12th century): Burney MS 357, f. 4v

It's clear that some medieval monks were very resourceful when it came to protecting their most precious treasures. The book curses that they devised indicate not only their knowledge of religious and Classical works, but also the importance they attributed to their sacred books and objects.

To learn more about medieval monastic libraries, and how books were acquired, used and stored, see this article on Medieval monastic libraries by Alison Ray, created as part of The Polonsky Foundation England and France Project: Manuscripts from the British Library and the Bibliothèque nationale de France, 700–1200. Together with the Bibliothèque nationale de France, we have digitised 800 manuscripts from our collections, which you can learn more about on our dedicated Medieval England and France webspace.

Clarck Drieshen

Follow us on Twitter @BLMedieval#PolonskyPre1200

Part of the Polonsky Digitisation Project

In partnership with

Supported by

Posted by Ancient, Medieval, and Early Modern Manuscripts at 12:01 AM

Tags

Manuscripts , Medieval , Medieval history , Polonsky

Copyright © The British Library Board

https://blogs.bl.uk/digitisedmanuscripts/2019/06/the-curse-of-the-spiritual-sword.html

The following is copied from the Medieval Manuscripts and Earlier website of the Medieval Manuscripts blog

Enjoy!

Angel of Death Conquered - Rome, Italy

Angel of Death Conquered - Rome, Italy The Curse of the Spiritual Sword

We have previously reported about our fascination with medieval book curses, added in monastic libraries to ward off thieves and warn careless users. Book curses typically state that those who stole or damaged a book would be spiritually condemned, often including the Greek-Aramaic formula ‘Anathema Maranatha'. For example, during the 12th and 13th centuries monks at Reading Abbey systematically added such curses to their manuscripts containing biblical commentaries (examples include Add MS 38687, Harley MS 101 and Harley MS 1246).

Reading Abbey’s book curse in a commentary on Deuteronomy and Joshua (1st quarter of the 13th century): Add MS 38687, f. 150r

Reading Abbey’s book curse in a commentary on Deuteronomy and Joshua (1st quarter of the 13th century): Add MS 38687, f. 150r We would like to share some new findings that will enable you to protect your favourite books, as well as other prized possessions. One example comes from the so-called ‘Noyon Sacramentary’ (Add MS 82956). This 10th-century manuscript, produced by the monastic community at Noyon Cathedral in northern France, contains masses and prayers for blessings and ceremonies. The manuscript opens with a wrathful curse that would bring down a series of spiritual punishments upon those who stole from or committed any other crime against Noyon Cathedral.

Noyon Cathedral’s ‘Curse of the Spiritual Sword’ (4th quarter of the 10th century): Add MS 82956, f. 1v

Noyon Cathedral’s ‘Curse of the Spiritual Sword’ (4th quarter of the 10th century): Add MS 82956, f. 1v The Noyon Cathedral curse begins: ‘excommunicamus eos et gladio sancti spiritus a vertice capitis usque ad plantam pedis transverberamus’ (‘We will excommunicate them and cut through them with the sword of the Holy Spirit, from the top of the head to the sole of the feet').

It then declares that book-thieves would be condemned to burn in the eternal fire of Hell together with Judas Iscariot, perhaps because they, like Judas, committed betrayal for material gain. Finally, to top it off, these thieves were to remain in the darkness of Hell where they would keep the devil company.

Perhaps an even more powerful curse for protecting your belongings comes from a 12th-century lectionary (containing readings from the Gospels for the Mass) from the Benedictine abbey of Tholey in western Germany (Add MS 29276). The curse is preceded by an itemised list of the monastery’s relics and sacred objects: ‘We have in this monastery of St Peter and St Mauritius eight bookcases of silver, four books of silver, and ten chalices’. Protecting this treasure is a curse that the community would collectively cast upon anyone who stole from the monastery:

‘a sancte matris ecclesiae segregamus ac perpetuae maledictionis anathemate condempnamus . sit que maledictus in domo . in agro . veniantque super eum omnes ille maledictiones . quas dominus per moysen in populum divin[a]e legis prevaricatione se esse missurum. Sitque anathema maranatha . id est pereat in secundo adventu domini. Stix sit ei potus. Amen’.

‘We will segregate him from the mother church and condemn him with the eternal curse of anathema: may he be cursed in the house and on the land, and let all the curses that the Lord cast through Moses onto the transgressors of the Divine Law come upon him. May he be anathema maranatha. That means: may he be damned at the Second Coming of Our Lord (the Last Judgement); may the Styx be his drink. Amen’.

Tholey Abbey’s ‘Styx-Curse’ (c. 1100–c. 1175): Add MS 29276, f. 162v)

Tholey Abbey’s ‘Styx-Curse’ (c. 1100–c. 1175): Add MS 29276, f. 162v) This curse encompasses both the eternal sentence to Hell, at the Last Judgement, and the Styx, the principal river of the Underworld. While it may seem unexpected to find a medieval monk referring to the Styx, monasteries gained knowledge about the Underworld through their copies of works such as Virgil's Aeneid. For example, in a 12th-century theological miscellany from the Cistercian abbey of Thame in Oxfordshire (Burney MS 357), the Styx is listed as one of the rivers in Hell, and its name is defined as ‘sadness’ (tristicia).

The ‘Stix’ among the ‘Names of the Infernal Waters’ (Nomina Humorum Infernalium) (1st half of the 12th century): Burney MS 357, f. 4v

The ‘Stix’ among the ‘Names of the Infernal Waters’ (Nomina Humorum Infernalium) (1st half of the 12th century): Burney MS 357, f. 4v It's clear that some medieval monks were very resourceful when it came to protecting their most precious treasures. The book curses that they devised indicate not only their knowledge of religious and Classical works, but also the importance they attributed to their sacred books and objects.

To learn more about medieval monastic libraries, and how books were acquired, used and stored, see this article on Medieval monastic libraries by Alison Ray, created as part of The Polonsky Foundation England and France Project: Manuscripts from the British Library and the Bibliothèque nationale de France, 700–1200. Together with the Bibliothèque nationale de France, we have digitised 800 manuscripts from our collections, which you can learn more about on our dedicated Medieval England and France webspace.

Clarck Drieshen

Follow us on Twitter @BLMedieval#PolonskyPre1200

Part of the Polonsky Digitisation Project

In partnership with

Supported by

Posted by Ancient, Medieval, and Early Modern Manuscripts at 12:01 AM

Tags

Manuscripts , Medieval , Medieval history , Polonsky

Copyright © The British Library Board

https://blogs.bl.uk/digitisedmanuscripts/2019/06/the-curse-of-the-spiritual-sword.html

Published on June 07, 2019 05:13

May 20, 2019

A Medieval Best Seller?

I believe I once mentioned I'm a B - I - G fan of ancient books. Why? Because a few of them still exist -- in the original. I'm especially fond of books written during what is euphemistically known as the Dark Ages. (No, no . . . . It wasn't really dark during those long ago days -- well, some of them were, but that's yet another story.) If you think you will come across many of them that weren't written by monks, you would be mistaken. Guess who wrote virtually all of them.. Go ahead . . . . I'll give you one guess.

I hope you'll enjoy the following article as much as I have. It is reprinted from English Historical Authors: https://englishhistoryauthors.blogspot.com/2019/05/bedes-life-of-cuthbert-remarkable-life.html

Don't yawn and rub your eyes. The book Katharine writes about is over eleven hundred years old -- and counting. It still exists. How many other authors could lay claim to such a phenomenon?

Enjoy!

˞ Cate

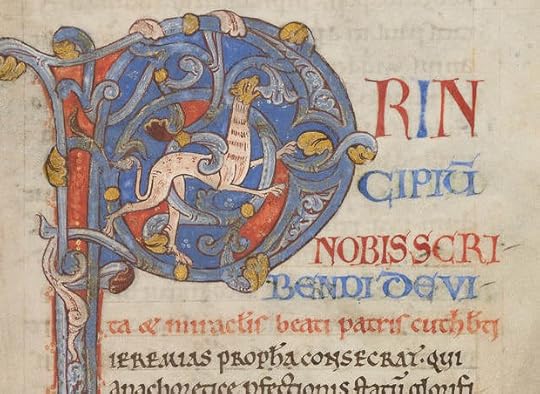

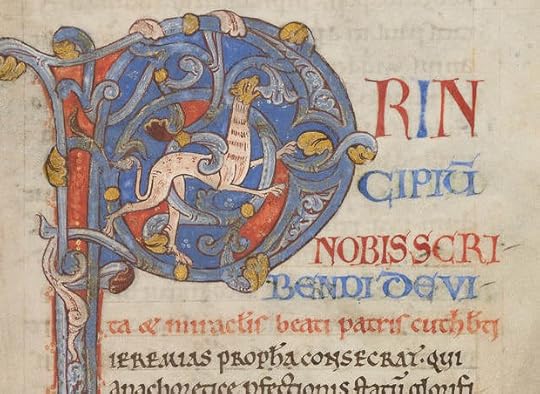

Title Page: Bede's Life of St. Cuthbert Bede’s Life of Cuthbert: The Remarkable Life of a Mediaeval Best-seller

Title Page: Bede's Life of St. Cuthbert Bede’s Life of Cuthbert: The Remarkable Life of a Mediaeval Best-seller

By Katharine Tiernan

Any visitor to the magnificent Romanesque cathedral in Durham will be drawn to the tomb of Cuthbert, the great saint of the north in whose honour the cathedral was built. His shrine is in the most sacred place in the cathedral, immediately behind the high altar. Originally hung with an ornate canopy, his tomb is now covered with a simple block of stone with his name, Cuthbertus, inscribed upon it.

The visitor may ask, who was this Cuthbert? How did a seventh-century monk from a remote corner of Northumberland come to be at the heart of one of the most powerful and influential cults in mediaeval England?

Part of the answer to these questions lies at the other end of the cathedral, in the Lady Chapel. In these more secluded surroundings our visitor can find another tomb, that of the Venerable Bede. Bede was thirty-nine years Cuthbert’s junior, and the two men never met. But without Bede, Cuthbert might be nothing more than a vague legend, like many other saints of the period, and the great cathedral at Durham might never have been built.

The story begins with a young Anglo-Saxon warrior, who at the age of seventeen took the decision to enter a monastery. Cuthbert’s monastery was close to the old Roman settlement of Trimontium, now Melrose in the Scottish Borders. At that time it was part of the great Anglo-Saxon kingdom of Northumbria. The year was 651, and the Christian faith had only recently arrived in the kingdom.

Cuthbert spent the rest of his life as a monk, but not in seclusion. He was an evangelist for the new religion and was also involved in the bitter power struggle which was to take place between the original Celtic Christianity of Northumbria and the nascent power of the Roman Church. In the latter part of his life he became a hermit on Inner Farne for eight years, bearing witness to the austere values of the Celtic tradition. While he was there, his fame as a wise man and miracle worker started to spread. As the Roman Church under his contemporary, Bishop Wilfrid, grew in wealth and power to rival the state, Cuthbert embodied the alternative values of the Northumbrian Church. When Wilfrid eventually fell from power, the King himself sailed to Inner Farne to implore Cuthbert to return to lead the Church as Bishop of Lindisfarne, which he eventually agreed to do. He went from the solitude and contemplation of a hermit’s life to the busiest job in the Church.

Cuthbert was already regarded as a saint by the time he died in 687. But the final proof of his sainthood was discovered eleven years after his death. The Lindisfarne monks wished to move his relics into the church for veneration, and opened his coffin, expecting to find a skeleton. Instead, they found his body incorrupt, the grave clothes fresh.

This was sensational proof of Cuthbert’s sanctity. Lindisfarne was to become a major pilgrimage centre and the monks decided a record of his life and miracles was needed. A Life was compiled by one of the monks of Lindisfarne, now known as the Anonymous Life. It must have been widely copied and circulated, and a copy reached Bede, a monk in St Peter’s monastery at Monkwearmouth. He clearly felt a strong affinity with the saint’s story. In 716, when Bede was in his early forties and already a distinguished scholar, he composed a version of the Life in Latin verse. Impressed, the Lindisfarne brothers begged Bede to write a new and more comprehensive prose life of the saint. He undertook the task with his customary scholarly rigour. In his Preface to the Life Bede tells us that he ‘has passed on nothing to be transcribed for general reading that has not been obtained by rigorous examination of trustworthy witnesses’. Of particular importance was a monk named Herefrith, who was with Cuthbert when he died. Bede quotes verbatim Herefrith’s account of the days leading up to Cuthbert’s death, and the death itself.

19th Century Image of The Venerable Bede The new Life was a great success. It is not difficult to see why. Although it is in some ways a conventional hagiography designed to give proofs of Cuthbert’s sainthood, it is also full of human interest and lively description. Bede loves a good story. He gives us a clear idea of Cuthbert’s character, and some of the miracles described are endearingly mundane – when the brothers forget to bring over a suitable plank to construct his latrine on Inner Farne, God obligingly arranges for a suitable piece of wood to be washed up on the shore.

19th Century Image of The Venerable Bede The new Life was a great success. It is not difficult to see why. Although it is in some ways a conventional hagiography designed to give proofs of Cuthbert’s sainthood, it is also full of human interest and lively description. Bede loves a good story. He gives us a clear idea of Cuthbert’s character, and some of the miracles described are endearingly mundane – when the brothers forget to bring over a suitable plank to construct his latrine on Inner Farne, God obligingly arranges for a suitable piece of wood to be washed up on the shore.

Some of the stories have become iconic, for example the tale of St Cuthbert and the otters, reported by one of the monks. He saw the saint leave the monastery where he was staying late at night and followed him, curious. He saw Cuthbert go down to the sea where he remained all night in prayer, standing in the icy waters. When he left the sea at dawn, two sea otters followed the saint out of the water and dried his feet with their fur. The watching monk was overcome with guilt at having spied on the saint and fell at his feet to beg forgiveness.

St. Cuthbert Praying in the Sea. Bede completed his Life of Cuthbert in 721. He went on to include an abridged version in his Ecclesiastical History of the English People, published ten years later. Bede’s monastery, St Paul’s, was one of two Benedictine monasteries at Monkwearmouth established in the Roman tradition. It was a thriving centre of scholarship and culture with a busy scriptorium. It was here that the Codex Amiatinus, the earliest complete Latin bible, was produced as a gift for the Pope. We can be sure that once completed, the Life of Cuthbert would have been copied many times and circulated to churches and monasteries in the other Anglo-Saxon kingdoms as well as Northumbria and further afield in Frankia and Italy. It was a true mediaeval best-seller.

St. Cuthbert Praying in the Sea. Bede completed his Life of Cuthbert in 721. He went on to include an abridged version in his Ecclesiastical History of the English People, published ten years later. Bede’s monastery, St Paul’s, was one of two Benedictine monasteries at Monkwearmouth established in the Roman tradition. It was a thriving centre of scholarship and culture with a busy scriptorium. It was here that the Codex Amiatinus, the earliest complete Latin bible, was produced as a gift for the Pope. We can be sure that once completed, the Life of Cuthbert would have been copied many times and circulated to churches and monasteries in the other Anglo-Saxon kingdoms as well as Northumbria and further afield in Frankia and Italy. It was a true mediaeval best-seller.

This wide distribution was essential to the survival of the work. A hundred and fifty years later the Viking invasions destroyed the monastic culture of Northumbria. The monks and nuns were an easy target for pagan raiders who had no compunction in looting the monasteries and enslaving their inhabitants. The written word had no value for the Vikings. The monastic libraries with all their books, deeds and records were destroyed; St Paul’s at Monkwearmouth became a roofless ruin. In 875, with the Danes now in command of York and heading northwards, the monks took the coffin containing the incorrupt body of the saint, together with the illuminated Gospels created in his honour, and left Lindisfarne.

Seven years later, in 882, they established a new monastery at Chester-le-Street after the miraculous intervention of the saint enabled them to make terms with Guthred, the Danish king of York. The cult of St Cuthbert, together with its lands and possessions, survived. It continued to attract pilgrims, not least from the royal house of Wessex. We are not told whether a copy of Bede’s Life had been popped into the coffin alongside the Lindisfarne Gospels, but certainly copies would have still existed elsewhere in parts of the country which had escaped the brunt of the Danish invasions.

Chester-le-Street was the only surviving monastery in the north of England for close on a hundred years. Although the Community diligently preserved the Lindisfarne traditions associated with the cult, monastic discipline started to slip. Monks married and had families, and the senior positions in the Community became hereditary, with each family holding a portion of the lands owned by St Cuthbert. The monastic reform movement of the tenth century which sought to end such practices was confined to the southern half of England, which enjoyed more stability than the north. For the Community the main aim was survival.

By the end of the tenth century, renewed threat from Danish armies led the Community to move again, this time to a promontory above the River Wear. Uninhabited at the time, it was cleared with the loyal help of the local population and the saint’s new shrine was established at Durham. It proved to be an excellent choice and highly defensible. St. Cuthbert Welcoming Visitors

St. Cuthbert Welcoming Visitors

However, 1066 saw the arrival of a new and different threat to the Community: the Normans. The threat this time was less physical – the Normans were, after all, Christians – but ideological. The Normans regarded Anglo-Saxon culture, including their saints, as backward and inferior. As the Normans started to take over the English Church, they often replaced Saxon saints with their own continental saints. Although St Cuthbert’s incorrupt body gave him claim to special status, King William was not convinced. On a visit to Durham he demanded that the Community open the coffin before him and threatened to kill all the senior clergy if it proved to be a fake. However, during a mass for All Saints’ Day, which was to be followed by the opening of the coffin, the King was visited by a terrible heat and fever. He leapt up, called for his horse and galloped out of the city. He was never to return to Durham. The Community was reprieved – for the time being.

Sometime after this incident King William appointed a Norman to the bishopric at Durham. The man was Walcher, a cleric who had been a canon at Liege, one of the great centres of learning in mid-eleventh century Europe. What view would he take of Cuthbert’s claims to sainthood? Walcher was an educated man with access to monastic libraries. Before he came to Durham he read Bede’s Ecclesiastical History and his Life of Cuthbert. They convinced him of the exceptional status of the saint and in turn, he convinced the King of the importance of the cult. Its future was secured – thanks to Bede.

There were to be changes, though. Having read Bede, Walcher knew that Cuthbert had been a celibate monk and that the original guardians of the shrine had been celibate monks also. Walcher’s plan was to oust the married canons and found a Benedictine monastery at Durham whose monks would be the new guardians of the saint.

Astonishingly, Bede was to play a role here too. A few years earlier, the prior of Winchcombe Abbey, a Saxon man named Aldwin, had acquired copies of Bede’s Life of Cuthbert and the Ecclesiastical History for the monastic library. They had an electrifying effect on him. The chronicler Simeon of Durham records:

He understood from the History of the Angles that the province of the Northumbrians had previously been peopled with numerous bands of monks, and many troops of saints … .these places, that is, the sites of these monasteries, he earnestly desired to visit, although he well knew that they were reduced to ruins, and he wished, in imitation of such persons, to lead a life of poverty.

Aldwin travelled north and with two companions set up camp in the ruins of St Paul’s Monastery. His single-handed revival of northern monasticism caught on, and others came to join him. By the time Walcher was planning to establish a monastery at Durham, there were local monks ready to help him.

Before Walcher could realise his plans he was murdered in a feud with the local Northumbrian nobility. The bishopric went to another Norman cleric, William St Calais. The new bishop energetically followed through on Walcher’s plans. Not only did he successfully found the new monastery, he went on to initiate the construction of a new cathedral in St Cuthbert’s honour to replace the existing Saxon church. The magnificent cathedral and the shrine of St Cuthbert would become the leading pilgrimage destination in the country. Bede’s Life of Cuthbert gained new popularity with lavishly illustrated versions appearing. The best-seller was back – and the fame of the saint it chronicled.

REFERENCES

Two Lives of Saint Cuthbert, trans. Bertram Colgrave Christ the King Library

The Age of Bede, trans. J.F. Webb, ed. D.H Farmer Penguin Classics

Simeon’s History of the Church of Durham Llanerch

~~~~~~~~~~~~~ Katharine Tiernan is a writer, teacher and passionate nature-lover. She grew up close to the dramatic coastline of North Northumberland and continues to draw inspiration from its history and landscape. She is currently working on a series of historical novels based on the legacy of St Cuthbert and his Community. Her first novel Place of Repose: A Tale of St Cuthbert’s Last Journey was published by Ningaui Press in 2013. Following its publication Katharine went on to hone her writing skills with an MA in Creative Writing (Distinction) at Newcastle University.

Katharine Tiernan is a writer, teacher and passionate nature-lover. She grew up close to the dramatic coastline of North Northumberland and continues to draw inspiration from its history and landscape. She is currently working on a series of historical novels based on the legacy of St Cuthbert and his Community. Her first novel Place of Repose: A Tale of St Cuthbert’s Last Journey was published by Ningaui Press in 2013. Following its publication Katharine went on to hone her writing skills with an MA in Creative Writing (Distinction) at Newcastle University.

Her latest novel, Cuthbert of Farne: A novel of Northumbria’s warrior saint, published by Sacristy Press, traces Cuthbert’s life and spiritual journey against the background of his turbulent times.

Katharine lives in Berwick-upon-Tweed, with a view from her writing desk across the Tweed estuary to Lindisfarne.

Buy Cuthbert of Farne:www.sacristy.co.uk/books/fiction/cuthbert-novel

Connect with Katharine: www.katharinetiernan.com

I hope you'll enjoy the following article as much as I have. It is reprinted from English Historical Authors: https://englishhistoryauthors.blogspot.com/2019/05/bedes-life-of-cuthbert-remarkable-life.html

Don't yawn and rub your eyes. The book Katharine writes about is over eleven hundred years old -- and counting. It still exists. How many other authors could lay claim to such a phenomenon?

Enjoy!

˞ Cate

Title Page: Bede's Life of St. Cuthbert Bede’s Life of Cuthbert: The Remarkable Life of a Mediaeval Best-seller

Title Page: Bede's Life of St. Cuthbert Bede’s Life of Cuthbert: The Remarkable Life of a Mediaeval Best-sellerBy Katharine Tiernan

Any visitor to the magnificent Romanesque cathedral in Durham will be drawn to the tomb of Cuthbert, the great saint of the north in whose honour the cathedral was built. His shrine is in the most sacred place in the cathedral, immediately behind the high altar. Originally hung with an ornate canopy, his tomb is now covered with a simple block of stone with his name, Cuthbertus, inscribed upon it.

The visitor may ask, who was this Cuthbert? How did a seventh-century monk from a remote corner of Northumberland come to be at the heart of one of the most powerful and influential cults in mediaeval England?

Part of the answer to these questions lies at the other end of the cathedral, in the Lady Chapel. In these more secluded surroundings our visitor can find another tomb, that of the Venerable Bede. Bede was thirty-nine years Cuthbert’s junior, and the two men never met. But without Bede, Cuthbert might be nothing more than a vague legend, like many other saints of the period, and the great cathedral at Durham might never have been built.

The story begins with a young Anglo-Saxon warrior, who at the age of seventeen took the decision to enter a monastery. Cuthbert’s monastery was close to the old Roman settlement of Trimontium, now Melrose in the Scottish Borders. At that time it was part of the great Anglo-Saxon kingdom of Northumbria. The year was 651, and the Christian faith had only recently arrived in the kingdom.

Cuthbert spent the rest of his life as a monk, but not in seclusion. He was an evangelist for the new religion and was also involved in the bitter power struggle which was to take place between the original Celtic Christianity of Northumbria and the nascent power of the Roman Church. In the latter part of his life he became a hermit on Inner Farne for eight years, bearing witness to the austere values of the Celtic tradition. While he was there, his fame as a wise man and miracle worker started to spread. As the Roman Church under his contemporary, Bishop Wilfrid, grew in wealth and power to rival the state, Cuthbert embodied the alternative values of the Northumbrian Church. When Wilfrid eventually fell from power, the King himself sailed to Inner Farne to implore Cuthbert to return to lead the Church as Bishop of Lindisfarne, which he eventually agreed to do. He went from the solitude and contemplation of a hermit’s life to the busiest job in the Church.

Cuthbert was already regarded as a saint by the time he died in 687. But the final proof of his sainthood was discovered eleven years after his death. The Lindisfarne monks wished to move his relics into the church for veneration, and opened his coffin, expecting to find a skeleton. Instead, they found his body incorrupt, the grave clothes fresh.

This was sensational proof of Cuthbert’s sanctity. Lindisfarne was to become a major pilgrimage centre and the monks decided a record of his life and miracles was needed. A Life was compiled by one of the monks of Lindisfarne, now known as the Anonymous Life. It must have been widely copied and circulated, and a copy reached Bede, a monk in St Peter’s monastery at Monkwearmouth. He clearly felt a strong affinity with the saint’s story. In 716, when Bede was in his early forties and already a distinguished scholar, he composed a version of the Life in Latin verse. Impressed, the Lindisfarne brothers begged Bede to write a new and more comprehensive prose life of the saint. He undertook the task with his customary scholarly rigour. In his Preface to the Life Bede tells us that he ‘has passed on nothing to be transcribed for general reading that has not been obtained by rigorous examination of trustworthy witnesses’. Of particular importance was a monk named Herefrith, who was with Cuthbert when he died. Bede quotes verbatim Herefrith’s account of the days leading up to Cuthbert’s death, and the death itself.

19th Century Image of The Venerable Bede The new Life was a great success. It is not difficult to see why. Although it is in some ways a conventional hagiography designed to give proofs of Cuthbert’s sainthood, it is also full of human interest and lively description. Bede loves a good story. He gives us a clear idea of Cuthbert’s character, and some of the miracles described are endearingly mundane – when the brothers forget to bring over a suitable plank to construct his latrine on Inner Farne, God obligingly arranges for a suitable piece of wood to be washed up on the shore.

19th Century Image of The Venerable Bede The new Life was a great success. It is not difficult to see why. Although it is in some ways a conventional hagiography designed to give proofs of Cuthbert’s sainthood, it is also full of human interest and lively description. Bede loves a good story. He gives us a clear idea of Cuthbert’s character, and some of the miracles described are endearingly mundane – when the brothers forget to bring over a suitable plank to construct his latrine on Inner Farne, God obligingly arranges for a suitable piece of wood to be washed up on the shore.Some of the stories have become iconic, for example the tale of St Cuthbert and the otters, reported by one of the monks. He saw the saint leave the monastery where he was staying late at night and followed him, curious. He saw Cuthbert go down to the sea where he remained all night in prayer, standing in the icy waters. When he left the sea at dawn, two sea otters followed the saint out of the water and dried his feet with their fur. The watching monk was overcome with guilt at having spied on the saint and fell at his feet to beg forgiveness.

St. Cuthbert Praying in the Sea. Bede completed his Life of Cuthbert in 721. He went on to include an abridged version in his Ecclesiastical History of the English People, published ten years later. Bede’s monastery, St Paul’s, was one of two Benedictine monasteries at Monkwearmouth established in the Roman tradition. It was a thriving centre of scholarship and culture with a busy scriptorium. It was here that the Codex Amiatinus, the earliest complete Latin bible, was produced as a gift for the Pope. We can be sure that once completed, the Life of Cuthbert would have been copied many times and circulated to churches and monasteries in the other Anglo-Saxon kingdoms as well as Northumbria and further afield in Frankia and Italy. It was a true mediaeval best-seller.

St. Cuthbert Praying in the Sea. Bede completed his Life of Cuthbert in 721. He went on to include an abridged version in his Ecclesiastical History of the English People, published ten years later. Bede’s monastery, St Paul’s, was one of two Benedictine monasteries at Monkwearmouth established in the Roman tradition. It was a thriving centre of scholarship and culture with a busy scriptorium. It was here that the Codex Amiatinus, the earliest complete Latin bible, was produced as a gift for the Pope. We can be sure that once completed, the Life of Cuthbert would have been copied many times and circulated to churches and monasteries in the other Anglo-Saxon kingdoms as well as Northumbria and further afield in Frankia and Italy. It was a true mediaeval best-seller.This wide distribution was essential to the survival of the work. A hundred and fifty years later the Viking invasions destroyed the monastic culture of Northumbria. The monks and nuns were an easy target for pagan raiders who had no compunction in looting the monasteries and enslaving their inhabitants. The written word had no value for the Vikings. The monastic libraries with all their books, deeds and records were destroyed; St Paul’s at Monkwearmouth became a roofless ruin. In 875, with the Danes now in command of York and heading northwards, the monks took the coffin containing the incorrupt body of the saint, together with the illuminated Gospels created in his honour, and left Lindisfarne.

Seven years later, in 882, they established a new monastery at Chester-le-Street after the miraculous intervention of the saint enabled them to make terms with Guthred, the Danish king of York. The cult of St Cuthbert, together with its lands and possessions, survived. It continued to attract pilgrims, not least from the royal house of Wessex. We are not told whether a copy of Bede’s Life had been popped into the coffin alongside the Lindisfarne Gospels, but certainly copies would have still existed elsewhere in parts of the country which had escaped the brunt of the Danish invasions.

Chester-le-Street was the only surviving monastery in the north of England for close on a hundred years. Although the Community diligently preserved the Lindisfarne traditions associated with the cult, monastic discipline started to slip. Monks married and had families, and the senior positions in the Community became hereditary, with each family holding a portion of the lands owned by St Cuthbert. The monastic reform movement of the tenth century which sought to end such practices was confined to the southern half of England, which enjoyed more stability than the north. For the Community the main aim was survival.

By the end of the tenth century, renewed threat from Danish armies led the Community to move again, this time to a promontory above the River Wear. Uninhabited at the time, it was cleared with the loyal help of the local population and the saint’s new shrine was established at Durham. It proved to be an excellent choice and highly defensible.

St. Cuthbert Welcoming Visitors

St. Cuthbert Welcoming Visitors However, 1066 saw the arrival of a new and different threat to the Community: the Normans. The threat this time was less physical – the Normans were, after all, Christians – but ideological. The Normans regarded Anglo-Saxon culture, including their saints, as backward and inferior. As the Normans started to take over the English Church, they often replaced Saxon saints with their own continental saints. Although St Cuthbert’s incorrupt body gave him claim to special status, King William was not convinced. On a visit to Durham he demanded that the Community open the coffin before him and threatened to kill all the senior clergy if it proved to be a fake. However, during a mass for All Saints’ Day, which was to be followed by the opening of the coffin, the King was visited by a terrible heat and fever. He leapt up, called for his horse and galloped out of the city. He was never to return to Durham. The Community was reprieved – for the time being.

Sometime after this incident King William appointed a Norman to the bishopric at Durham. The man was Walcher, a cleric who had been a canon at Liege, one of the great centres of learning in mid-eleventh century Europe. What view would he take of Cuthbert’s claims to sainthood? Walcher was an educated man with access to monastic libraries. Before he came to Durham he read Bede’s Ecclesiastical History and his Life of Cuthbert. They convinced him of the exceptional status of the saint and in turn, he convinced the King of the importance of the cult. Its future was secured – thanks to Bede.

There were to be changes, though. Having read Bede, Walcher knew that Cuthbert had been a celibate monk and that the original guardians of the shrine had been celibate monks also. Walcher’s plan was to oust the married canons and found a Benedictine monastery at Durham whose monks would be the new guardians of the saint.

Astonishingly, Bede was to play a role here too. A few years earlier, the prior of Winchcombe Abbey, a Saxon man named Aldwin, had acquired copies of Bede’s Life of Cuthbert and the Ecclesiastical History for the monastic library. They had an electrifying effect on him. The chronicler Simeon of Durham records:

He understood from the History of the Angles that the province of the Northumbrians had previously been peopled with numerous bands of monks, and many troops of saints … .these places, that is, the sites of these monasteries, he earnestly desired to visit, although he well knew that they were reduced to ruins, and he wished, in imitation of such persons, to lead a life of poverty.

Aldwin travelled north and with two companions set up camp in the ruins of St Paul’s Monastery. His single-handed revival of northern monasticism caught on, and others came to join him. By the time Walcher was planning to establish a monastery at Durham, there were local monks ready to help him.

Before Walcher could realise his plans he was murdered in a feud with the local Northumbrian nobility. The bishopric went to another Norman cleric, William St Calais. The new bishop energetically followed through on Walcher’s plans. Not only did he successfully found the new monastery, he went on to initiate the construction of a new cathedral in St Cuthbert’s honour to replace the existing Saxon church. The magnificent cathedral and the shrine of St Cuthbert would become the leading pilgrimage destination in the country. Bede’s Life of Cuthbert gained new popularity with lavishly illustrated versions appearing. The best-seller was back – and the fame of the saint it chronicled.

REFERENCES

Two Lives of Saint Cuthbert, trans. Bertram Colgrave Christ the King Library

The Age of Bede, trans. J.F. Webb, ed. D.H Farmer Penguin Classics

Simeon’s History of the Church of Durham Llanerch

~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Katharine Tiernan is a writer, teacher and passionate nature-lover. She grew up close to the dramatic coastline of North Northumberland and continues to draw inspiration from its history and landscape. She is currently working on a series of historical novels based on the legacy of St Cuthbert and his Community. Her first novel Place of Repose: A Tale of St Cuthbert’s Last Journey was published by Ningaui Press in 2013. Following its publication Katharine went on to hone her writing skills with an MA in Creative Writing (Distinction) at Newcastle University.

Katharine Tiernan is a writer, teacher and passionate nature-lover. She grew up close to the dramatic coastline of North Northumberland and continues to draw inspiration from its history and landscape. She is currently working on a series of historical novels based on the legacy of St Cuthbert and his Community. Her first novel Place of Repose: A Tale of St Cuthbert’s Last Journey was published by Ningaui Press in 2013. Following its publication Katharine went on to hone her writing skills with an MA in Creative Writing (Distinction) at Newcastle University.Her latest novel, Cuthbert of Farne: A novel of Northumbria’s warrior saint, published by Sacristy Press, traces Cuthbert’s life and spiritual journey against the background of his turbulent times.

Katharine lives in Berwick-upon-Tweed, with a view from her writing desk across the Tweed estuary to Lindisfarne.

Buy Cuthbert of Farne:www.sacristy.co.uk/books/fiction/cuthbert-novel

Connect with Katharine: www.katharinetiernan.com

Published on May 20, 2019 05:33

November 1, 2018

Do We Have to Tell Them the House is Haunted?

My House Seriously?

My House Seriously?(This article is reprinted from JSTOR. I know, I know.... It isn't Halloween any longer--but it's All Hallows Day. So enjoy!)

When dealing with a reputedly haunted house, honesty is the best policy.

“Haunted” houses generally fall under stigmatized property laws. These laws cover homes where notorious crimes, violent murders, or suicides have occurred. The real estate law scholar George Lefcoe notes that, since the 1960s , there has been a shift in the U.S. from caveat emptor, or “buyer beware,” to the principle that problems with a house should be disclosed to interested buyers. Often this takes the form of detailed forms for property condition disclosure. In other cases, realtors are simply obligated to answer any direct questions about a home’s flaws.

Disclosure laws vary from state to state. “Hauntedness” isn’t considered a material fact in all of them, and in any case not all states require sellers to disclose aspects that might lower a property’s value. There are, however, also cases of haunted houses attracting buyers, who sometimes even contribute to rumors of a house’s haunted status to get a discount. Or they might simply be drawn to the paranormal aura.

California, for example, has one of the more stringent disclosure laws. Its Civil Code mandates that realtors tell buyers if a violent death occurred three years before a purchase offer. The California realtor Randall Bell says that stigmatized property can sell for 10% to 25% less than a non-stigmatized one. As he explained to Curbed , “perception is everything with stigmatized properties.” This is why, when he consults on places where there are rumors of cultic murders or satanic rites, he effectively treats them as if they’re real.

The legal scholar Daniel Warner has referred to haunted locales as “karmic-based real estate.” His argument is that irrational beliefs shouldn’t have legal backing, and thus that sellers shouldn’t be required to disclose stigmas like murders and hauntings. His concern is that laws mandating disclosure might be seen as condoning belief in ghosts, and might actually influence it.

As the house had been “possessed by poltergeists,” it couldn’t be said to be unoccupied.

Case in point: In 1989, a man purchased a large Victorian house in Nyack, NY, before learning about local stories of Revolution-era ghosts inhabiting the place. He demanded to be released from the contract, as the realtor hadn’t disclosed the house’s reputation for being haunted. The buyer noted that he didn’t himself believe in ghosts, but was concerned about the effect on the property value.

The case eventually went to trial and later on to an appeal. In 1991, in a joke-laced ruling that quoted Ghostbusters, the appellate court agreed with the purchaser: As the house had been “possessed by poltergeists,” it couldn’t be said to be unoccupied. Real estate law in the state changed briefly as a result, requiring disclosure of a house’s haunted nature.

Ancient Disclosure Norms

Disclosure laws for haunted houses date back thousands of years, though pre-modern ghosts weren’t pictured the way contemporary specters are. Ghosts in ancient Rome weren’t always transparent, and instead were sometimes described as smoky or lifelike.

But then as today, plenty of people believed in ghosts. The oldest surviving haunted house story in Greek and Roman literature is the Mostellaria, or “The Haunted House,” by the Roman comic playwright Plautus. Likely first performed between 200 and 194 BCE, the Mostellaria was probably adapted from the Athenian playwright Philemon’s play Phasma, or “The Ghost,” which itself was written around 288 BCE. Phasma is among several stories whose titles are referenced in other documents, although the stories themselves don’t survive in their entirety.

Haunted house stories in antiquity, including the Mostellaria, followed a fairly standard template , writes the classicist Debbie Felton in a 1999 article. A guest is murdered in the house and buried on the property. The guest’s specter then begins to haunt the house at night. What stands out about this story, as in the Mostellaria, is the appearance of a ghost with a physical presence and a claim to a physical space—more alarming than a typical ancient ghost story, where the ghosts are relegated to dreams.

Finally, a brave and rational man arrives on the scene, determined to unravel the mystery of the haunting. The presence of this educated figure is meant to assure skeptical readers that the ghost does exist; after all, he’s no gullible sort. He follows the ghost to a spot that is then dug up. Human bones are revealed. Once the bones receive a proper burial, the hauntings come to an end.

The plot ultimately reinforces the gravity of the host’s transgression as well as the importance of burying bodies with due respect. The classicist Yelena Baraz has referred to this trope as an example of the standard “soul released from torment” plot. In the Mostellaria, this template is put to comic effect, as a ghost story told by the character Tranio within the larger story. One of the details Tranio relates is that the house’s ghost makes knocking sounds—likely the first recorded suggestion of a poltergeist.

Once the remains are properly buried, the hauntings come to an end.

Ancient stories of haunted houses also delve specifically into the question of disclosure. Although much contemporary knowledge of ancient laws is based on documents like the Roman Digest of Justinian, there’s also evidence of disclosure norms from the haunted house stories themselves. For instance, Pliny the Younger’s Letter 7.27, from the first century, is an early ghost story that centers on the philosopher Athenodorus. (The same letter also includes a story of specters that cut people’s hair as they sleep.)

Athenodorus is a prototypical educated and brave protagonist of a haunted house story. On arrival in Athens, he sees that a deserted house is for sale. He investigates and learns that it’s haunted by a bearded, chain-rattling ghost. The previous tenants have lost sleep and even died from terror due to the sound of the chains and the emaciated appearance of the old ghost. As fits the standard plot, Athenodorus follows the ghost to a spot in the courtyard. Digging reveals a corpse buried in chains. And surprise! Once the remains are properly buried, the hauntings come to an end.

Felton writes in her 1999 book Haunted Greece and Rome:

Pliny’s story also includes the detail that the haunted house was advertised at a low rent. Athenodorus, as a potential tenant, finds the low price of the house suspicious. It is an interesting detail, suggesting that haunted houses might in fact have been an economic reality in the ancient world.

Felton argues that the ancients recognized an ethical expectation (though not necessarily a law) that sellers would divulge the haunted status of a house to prospective buyers. The Greek philosopher Diogenes the Cynic, who died in 323 BCE, was recorded by Cicero as arguing that interested buyers should be told of flaws, including “an unhealthy atmosphere,” in the houses they’re considering purchasing. Felton therefore concludes that norms requiring sellers to reveal that their houses are haunted haven’t changed much in 2,000 years.

The Continuity of Ancient and Modern Ghost Stories

The modern stories are nearly as formulaic as the ancient versions. Generally, spirits invade because of something that went horribly wrong: a violent murder, an injustice, a violation of the rules of family life, etc. Audiences are often expected to be sympathetic to these ghosts, especially if they were marginalized during life: people living with mental illness, victims of violence, or otherwise vulnerable or exploited people.

Aesthetically, these tales often trade on Gothic tropes of spaces of darkness and shadow. The essential idea is that buildings and spaces correspond to people’s internal states; a house may be nearly as alive and feeling as its inhabitants. It’s challenging to show this kind of inner conflict directly, and one way to make it palpable is literalize it.

Commercialized and televised experiences of the paranormal lead to what Annette Hill, a media and communication professor at Lund University, calls a “revolving door.”

“This revolving door of skepticism and belief regarding the paranormal is part of how we experience haunted houses, and we carry this kind of ambiguous engagement with paranormal matters into our media engagement,” she told me. “At present, the rise of populism, and a politics of fear and anxiety about political and environmental catastrophes may be connected with a cultural dynamics of fear of the unknown, or the paranormal in our personal lives.”

Dale Bailey, a sci-fi-fantasy-horror author and an English professor at Lenoir-Rhyne University, believes that one reason these stories endure is that the haunted house is a flexible and potent metaphor. He explains:

The fear of an invasion of the domestic space–the safest space, the home–by forces natural or supernatural seems to be pretty universal. And the fear of your bonds with your most loved ones disintegrating is probably even more so.

There are ways to clean a house, spiritually speaking. Ghost hunters can locate the objects that ghosts are fixating on, or facilitate communication with the spirits to find out why they’re hanging around. More simply, some people swear by sage and cedar oil . But unless these remedies change the perception that a house is haunted, they’re unlikely to clear out the stigma.

Have a correction or comment about this article?

Please contact us.

classics Halloween law Quaderni Urbinati di Cultura Classica Real Property, Probate and Trust Journal Transactions of the American Philological Association (1974-2014)

Resources

JSTOR is a digital library for scholars, researchers, and students. JSTOR Daily readers can access the original research behind our articles for free on JSTOR.

PROPERTY CONDITION DISCLOSURE FORMS: HOW THE REAL ESTATE INDUSTRY EASED THE TRANSITION FROM CAVEAT EMPTOR TO "SELLER TELL ALL"

By: George Lefcoe

Real Property, Probate and Trust Journal, Vol. 39, No. 2 (Summer 2004), pp. 193-250

American Bar Association

Folkloric Anomalies in a Scene from the "Mostellaria"

By: Debbie Felton

Quaderni Urbinati di Cultura Classica, New Series, Vol. 62, No. 2 (1999), pp. 123-142

Fabrizio Serra Editore

Pliny's Epistolary Dreams and the Ghost of Domitian

By: YELENA BARAZ

Transactions of the American Philological Association (1974-2014), Vol. 142, No. 1 (Spring 2012), pp. 105-132

The Johns Hopkins University Press

https://daily.jstor.org/do-we-have-to-tell-them-house-is-haunted/

Published on November 01, 2018 21:21

June 24, 2018

So Much to Read, So Little Time

How will I ever get it all done??? So. . .what am I in the mood for right now? A really great book to catch my attention and hold it. Oh yeah, sure. So just kill me now. There are so many, how will I ever choose? I want to read about a love story. Yeah! A wedding with a handsome prince, maybe a medical drama, something that even makes me laugh and cry. So . . . right! All in one book? Like, where am I going to find something like that? Somebody help!!!

How will I ever get it all done??? So. . .what am I in the mood for right now? A really great book to catch my attention and hold it. Oh yeah, sure. So just kill me now. There are so many, how will I ever choose? I want to read about a love story. Yeah! A wedding with a handsome prince, maybe a medical drama, something that even makes me laugh and cry. So . . . right! All in one book? Like, where am I going to find something like that? Somebody help!!!  Oh, cool! It's even got cats in it! Where can I find it? It's at Amazon.com! YAY! I can get it on my Kindle. How cool is that?

Oh, cool! It's even got cats in it! Where can I find it? It's at Amazon.com! YAY! I can get it on my Kindle. How cool is that? I'm on my way!

Published on June 24, 2018 05:20

February 18, 2018

Mr. Beidler, Teacher Extraordinaire

Daniel Boone (not Mr. Beidler)

Daniel Boone (not Mr. Beidler) I once had an American History teacher named Mr. Beidler. Honest. His first name is Mr. because I never learned his real name…and I regret it to this day.

Keep in mind that I grew up in Albuquerque, New Mexico. This is important to my story for a couple of reasons. The first one is that Albuquerque is situated at the edge of the American Southwest desert. Also recall—or not—that I grew up in a day that could best be described as B.C.P. (before cell phones…and their handy little cameras). I know this is a shocking revelation. Yes, there are still those of us who never used the things. (Yup. And if you got sick at school, or they kicked you out—I have no personal knowledge of this, by the way—they had to call your mother and she would come to pick you up…if she had the family car that day. Otherwise, you walked.

As I recall, Mr. Beidler had a Texas accent, so I presume that’s where he grew up. I could be wrong. There are places in S.E. New Mexico where the residents also sound Texan. Mr. Beidler was middle-aged. That is to say that he could have been anywhere between twenty-five years old to fifty-five. He didn’t look young to me, but I was only thirteen at the time, and everybody older than twenty-one looked rather…old. Anyway, he had sort of nondescript light brown hair, and blue-eyes. This describes somewhere around one-half of all the men in Texas who weren’t Black Americans or of Spanish descent. Mr. Beidler’s claim to fame, at least in my book, is that he achieved what I regard as the impossible. He fired my imagination.

I best recall a couple of stories he told us. The first regards Daniel Boone. Daniel hacked his way through otherwise impassable forests using a long knife. Whoa! Can you imagine such a place? A place with trees growing so close together you can’t get through except by hacking a path through with a knife? Think how sharp that knife must have been! For the most part, everything east of the Mississippi River once had such thick forests. Think of it as an ocean of trees. That thought alone fires my imagination. Come to think of it, it already has.

Anyway, I spent my early childhood in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma. That’s a city situated on the American Great Plains. Remember I said that Albuquerque borders the Southwest desert? We had a lot of tumbleweeds there, but that’s about it. Trees? Not so much.

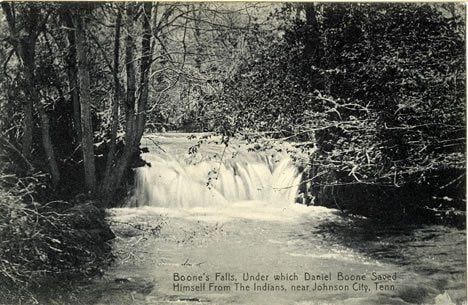

A tumbleweed, in case you wondered. Imagine my astonishment to learn that well within twenty miles of our house is a place that Daniel Boone traveled through. It’s now called Boone’s Creek Falls. He was once forced to shelter beneath the falls from Indians trying to capture him. Shades of the movie, “The Last of the Mohicans” comes to mind! Falls on that creek? Yes, they’re still there. Now, in Albuquerque, the Rio Grande River runs through the city. When I was a child, we referred to it the Rio Trickle (okay, so we weren’t all that original), but irrigation along the length of the long river had taken its toll, even then. But a creek? A creek? I can’t imagine such a small waterway with falls large enough to shelter a man. Mr. Beidler also told us about people crossing the Cumberland Gap in Conestoga wagons. Everyone had to push the wagon except for one person who pulled the horses’ harnesses up the trail. Nobody rode in the wagon. Nobody. I still wasn’t very impressed by what an achievement that must have been.

A tumbleweed, in case you wondered. Imagine my astonishment to learn that well within twenty miles of our house is a place that Daniel Boone traveled through. It’s now called Boone’s Creek Falls. He was once forced to shelter beneath the falls from Indians trying to capture him. Shades of the movie, “The Last of the Mohicans” comes to mind! Falls on that creek? Yes, they’re still there. Now, in Albuquerque, the Rio Grande River runs through the city. When I was a child, we referred to it the Rio Trickle (okay, so we weren’t all that original), but irrigation along the length of the long river had taken its toll, even then. But a creek? A creek? I can’t imagine such a small waterway with falls large enough to shelter a man. Mr. Beidler also told us about people crossing the Cumberland Gap in Conestoga wagons. Everyone had to push the wagon except for one person who pulled the horses’ harnesses up the trail. Nobody rode in the wagon. Nobody. I still wasn’t very impressed by what an achievement that must have been.

Boone Falls

Boone Falls  Conestoga Wagon Nosiree. Keep in mind that I’ve traveled through western Colorado north of Durango on Hwy 550. Picture driving across Red Mountain, which tops out at 11,075 feet. As you near the top, you see a sign that says, “Steep Grade Ahead.” So, then you begin to drop down into Ouray. S-l-o-w-l-y. They meant what they said about “Steep Grade Ahead.” It’s a curving two-lane road that clings to the mountainside and largely contributed to my intense fear of falling. It didn't do much for my love of flying, either.

Conestoga Wagon Nosiree. Keep in mind that I’ve traveled through western Colorado north of Durango on Hwy 550. Picture driving across Red Mountain, which tops out at 11,075 feet. As you near the top, you see a sign that says, “Steep Grade Ahead.” So, then you begin to drop down into Ouray. S-l-o-w-l-y. They meant what they said about “Steep Grade Ahead.” It’s a curving two-lane road that clings to the mountainside and largely contributed to my intense fear of falling. It didn't do much for my love of flying, either.

Mariana Trench--Notice that this is the largest image??? No joke. My (Navy) husband was offered orders to Guam, among other places. I politely informed him that, if he accepted them, he’d go alone. I can’t imagine flying at 37K feet over the deepest fissure in the Earth’s crust, the Mariana Trench. That sucker is almost seven miles deep! Suffice it to say, my response was, “No Way In You-Know-Where!” (Except, I was a little more explicit than that regarding the place.) Anyway, I had no plans in mind for making such a journey…no such bucket-list items. Not me. Nope. Not happening. My husband was no help. He consoled me with, “You wouldn’t even know you’d hit the water if you fell from 37,000 feet. You’d be dead way-y before then.” Oh, great. Thanks! Very comforting…. Suffice it to say, we didn’t go to Guam.

Mariana Trench--Notice that this is the largest image??? No joke. My (Navy) husband was offered orders to Guam, among other places. I politely informed him that, if he accepted them, he’d go alone. I can’t imagine flying at 37K feet over the deepest fissure in the Earth’s crust, the Mariana Trench. That sucker is almost seven miles deep! Suffice it to say, my response was, “No Way In You-Know-Where!” (Except, I was a little more explicit than that regarding the place.) Anyway, I had no plans in mind for making such a journey…no such bucket-list items. Not me. Nope. Not happening. My husband was no help. He consoled me with, “You wouldn’t even know you’d hit the water if you fell from 37,000 feet. You’d be dead way-y before then.” Oh, great. Thanks! Very comforting…. Suffice it to say, we didn’t go to Guam.  Cumberland Gap So, back to the Cumberland Gap and those Conestoga wagons. (Sorry…I have a B-A-D habit of digressing.) At the time, I’m fairly sure I hadn’t even thought of either the place or the journey made by those early pioneers…until the B-I-G engine in my husband’s truck began lugging while towing our 27-foot fifth-wheel RV. At the time, I recall wondering if I needed to get out and push…which, of course, triggered my memory of Mr. Beidler’s description. It was only then that I saw a sign pointing the way toward the Cumberland Gap. Okay, so now I’m impressed.

Cumberland Gap So, back to the Cumberland Gap and those Conestoga wagons. (Sorry…I have a B-A-D habit of digressing.) At the time, I’m fairly sure I hadn’t even thought of either the place or the journey made by those early pioneers…until the B-I-G engine in my husband’s truck began lugging while towing our 27-foot fifth-wheel RV. At the time, I recall wondering if I needed to get out and push…which, of course, triggered my memory of Mr. Beidler’s description. It was only then that I saw a sign pointing the way toward the Cumberland Gap. Okay, so now I’m impressed.

Below Cumberland Gap

Below Cumberland Gap And I thank you, Mr. Beidler. Taking American History from you was a rare privilege. You were an excellent teacher. By the way, my oldest friend and fellow classmate in your class, Terry Mora Sanchez, thinks so, too!

~With Gratitude

Cate...and Terry

Published on February 18, 2018 10:07