Mark Buchanan's Blog

December 4, 2020

Shelter Me

As promised in last week’s post, I will share over the next few weeks excerpts from books I am currently writing.

This is from the opening chapter of Shelter Me, a novel, to use Netflix’s favorite claim/disclaimer, “based on true events.”

[image error]

These true events happened in and around several villages in southeast France during WWII. During the war, a cluster of small and mostly Protestant communities worked together to shelter refugees, mostly Jewish children, from deportation and death at the hands of the Nazis and their French collaborators. The main village was Le Chambon sur Lignon (where Cheryl and I were set to live for three months this spring but, because of COVID, had to leave after a mere twelve days). Historians mostly agree that the central figure in this heroic effort was pastor André Trocmé, along with his formidable wife, Magda.

My opening chapter starts in the darkest year of the war, 1943. It introduces the two main characters, André and Madga, as well as a young Jewish refugee, Hannah. Hannah is a fictional character whose portrait I have created from a composite of several historical accounts. The final character I introduce here is Virginia Hall, an American spy and military operative working under British directive. Her story is only now fully coming to light – expect to hear a lot about her from various sources in the next few years. She displayed extraordinary courage, dedication, resourcefulness, and resiliency – not the least because she did all her derring-do while nursing a prosthetic leg. Her work in the latter part of the war directly touches on the events that unfolded in Le Chambon.

I hope you enjoy.

Shelter Me

A Novel

[image error]by Mark Buchanan

Chapter One

La Brule

February 11, 1943

A north wind scythes down the sharp-cut valley, bent on tearing rooves from walls, pulling trees from roots, scattering every loose thing every which way. And it snows, not gently: each flake a tiny barb, each gust a strafing. It will be hard to find warmth tonight, anywhere. The wind here is often hard and bitter cold. But tonight is La Brule, the demon wind. A force of pure malice. It can destroy in a single stroke things the earth has nurtured for centuries.

Only fifty feet to go. Then fire, bread, soup. Then his children, gathering around him, competing for space on his lap. Then her arms. Her strong thin arms, lean and tough as ropes, cinching his waist, pulling him into her sinewy fierceness. Though if he doesn’t stop eating all that bread, she won’t be able to reach all the way around. She’ll lose her grip on him.

André Trocmé pulls the collar of his jacket tight against the flesh of his neck. He shields his cheeks with his arm. His bones ache. And his back. That old injury every year twists deeper into him. Shows up in weather damp or cold, an intruder hammering the door, pushing its way in, taking up more and more room inside him. He limps the last twenty feet, drags his left leg like he’s taken a bullet in the thigh. The door is locked. He hammers on it.

And she’s there, worn, thin, but still beautiful. “Come in,” Magda says. Oh, come in.”

And her arms take him, and reach all the way around.

And it is warm.

***

“Monsieur Trocmé?”

“Yes?”

“André Trocmé?”

“Yes.”

“Of Le Chambon sur Lignon?”

“Yes.”

“You are married to Madga?”

He hesitates.

“I am simply establishing your correct identity. I do not want to make a clerical error, you understand?”

“Yes.”

“Magda, she is your wife?”

“Yes.”

“You are the pastor of The Protestant Temple?”

“Yes.”

“And there is another pastor there?”

“Edouard Theiss.”

“Pastor Trocmé of Le Chambon sur Lignon, there are rumors.”

“Rumors?”

“Do not take me for a fool. You know very well what I am speaking of. No?”

Trocmé falls silent, looks at his big hands. He wants to reach a hand around to his back, knead the soreness there. But he holds still. He’s learning to avoid all unnecessary movement.

“Yes,” Trocmé says.

“Yes?”

“Yes, I know what you are talking about.”

“Then say it.”

“The Jews.”

“Ah, yes: the Jews. So we understand one another?”

“I do not think we understand one another.”

“Listen, Monsieur Trocmé. Listen well. These are times for great caution. Great prudence. And you, you are putting yourself, your family, your church, your village – all whom you love – in grave peril, by these things you are doing.”

Trocmé looks up. The officer wears a rumpled suit. His tie is askew. Bread crumbs fleck his lapels. The Gestapo would disapprove, sternly. The Milice too. He seems a kind man, sober and slow, doing his job. Bored. Thinking of the end of the day. The bread and soup his wife is making. Her arms.

“Perhaps I am,” Trocmé says. “Perhaps. But perhaps you are putting yourself in graver peril, by what you are doing, and not doing.”

The man leans forward, lowers his voice. “Do not test me, Monsieur Trocmé. Do not try my patience. You must take care. Great care. I am telling you this as a friend.”

Trocmé looks at his own hands again. They have grown leathery of late. Ink, like nicotine, stains dark the seams between his fingers. It won’t come out, no matter how hard he scrubs.

“Perhaps you are right,” he says. “Perhaps we do understand one another.”

***

Wet earth soaks Hannah’s clothing. It soaks her skin. It seeps into her bone and muscle. Its coldness is like a burning. She trembles, can’t stop. She wants to cry, but swallows it: any sound that does not mimic the pulse of the deep forest, its chittering animal noises, the aching groaning of its trees, its long eerie silence, will give her away. But the dogs will likely find her soon anyways. Their barks splinter the air, break it like stones shattering glass. The dogs will pick up her scent, double their speed, bear down on her with lupine ferocity: sharp teeth glistening, tassels of saliva looping from their mouths. Their masters will not restrain them. She has seen all this before.

She thinks of Sasha. Sasha laughing, her head tipped back. The whole room glowing with candles and firelight. The whole room filled with the smell of food. The whole room filled with laughter, like coins falling. And it is warm. She settles into the memory as though into a soft bed.

***

“Stop,”

Virginia and the two men with her and her passeur halt. They are ten feet from the Spanish border, but a small guard house with two guards stands athwart the trail. One guard looks sleepy and bored. If it was only him, Virginia thinks, he would wave them through. But the other guard, the one in charge, has a lean hawkish look. He is rigid with his official status, and bristles with a kind of pent-up vindictiveness. The two men travelling with her sit down heavily on a fallen tree near the path. Virginia wants to join them but remains standing. She wishes she had taken her pistol out of her pack.

“Papers,” the angry guard says.

The passeur produces his papers with a swift smooth action. He’s done this before, she thinks. The guard examines them closely. He holds one up to his face and looks at the signature and bureau stamp with a magnifying glass. He hands them back, wordless.

“You,” he says to Virginia. “And you two, get up. Papers.”

She takes off her pack and starts to open the ties. The other guard, the sleepy one, suddenly comes alert. He cocks his rifle, points it at her. She takes her hands off the bag.

“Well, you men will have to decide which it is. Do you want my papers, or do you want to shoot me?”

“Slow, very slow,” the guard with rifle says.

She reaches into her bag. She feels the handle of her pistol. She put a fresh clip in last night, and oiled it. She touches the cool smoothness of the barrel. She could pull it out and kill the guard with the gun first, then hold up the second guard before he unholstered his side arm, or kill him as well. She looks up, into the face of the one pointing the rifle at her. He must be no more than twenty. Probably still living at home. A little sister, maybe. A father with a bad back who gets up every morning, uncomplaining, and shuffles off to his job at a foundry or brick works. A mother who feeds him more than he needs, more than the family can afford. He is, she sees, scared. She imagines the news reaching his home, that their son, their brother, has been slain in cold blood in the service of his duty.

She pulls out her papers. The other two men with her are also holding theirs.

Then guard inspecting them takes all three sets at once. He looks them over, one at a time. His face betrays no emotion. He seems to be about to hand them all back. And then, with blinding speed, he pulls his gun, cocks it.

“You are all under arrest,” he says.

The other guard looks ready to shoot.

In twenty minutes, the three of them are in a police wagon on their way to prison in Figueres, Spain. The passeur is on his way back to France, scolded, warned, flush with Virginia’s money.

Virginia looks at the two men, smiles. Neither smiles back.

November 27, 2020

Why I Have No Writing Muse

I have always envied, and maybe resented, writers for whom writing comes easy: it flows from their depths to their pen to the page in one silky unbroken stream. Thoughts unfold effortlessly into words, words into sentences, sentences into paragraphs, paragraphs into chapters, chapters into books, like one of those time-lapse recordings of a seed becoming a tree. I know a few writers whose first drafts are better than my finished ones.

It’s wondrous, bewildering, and altogether annoying.

Me, I toil at writing. I find language unruly, a coiling, thrashing, writhing beast, desperate to get away from me, resistant to all my efforts to tame it.

All the same, I keep making the effort. Other writers sometimes ask me about my writing routine – the time I commit to it, the place where I do it, the rituals I surround it with, the goals I set for it.

Two caveats before I share some of that.

One, I assume many of you are not the least bit interested in any of this. You have my glad permission to exit stage right, or left, whatever your leanings.

Two, I insist that my ways are not your ways, that one writer’s yoke is likely another writer’s shackles. I share what I do not because I think you should imitate me, but because there may be an idea or two scattered about my midden that you can pluck, retool, and employ to your own ends.

With that, my writing routine:

I write almost every Friday morning, nine ‘til noon, or just after. A mere three to four hours. That’s it. That schedule has allowed me to publish ten books in twenty years – roughly one every two years – plus write hundreds of articles, blog posts, and sundry miscellany, as well as begin and abandon six unpublished books. In short, committing to writing three to four hours a week (which usually amounts to a 1000 to 1500 words at each sitting) has been enough for me to build a reasonable stockpile.

My trick: I treat those three to four hours as part of my day job. Sometimes I actually write under contract and deadline, so guns and lawyers await any failure. But often I write on my own timeline. I keep the same pace either way. In fact, despite my second caveat above, that my ways should not become your ways, I think that any writer who does not treat their writing as necessary work will rarely if ever publish. They will dream about the book they’ll one day write, should time allow, but never actually write it. In truth, the time you need for writing is already lying in the cracks and seams of your weekly schedule, but you have to go pry it loose.

I edit as I go, more or less. Many writers will denounce this as a damper on creativity, and in my repentant moods I’m inclined to agree. But I can’t help myself. There is likely a psychological explanation for my behavior that derives from some childhood trauma or deficiency, but, alas, it is what it is. If you can let your writing rip, and happily throw down a hot mess on the page, and come back later to sift and order it, great. This has never worked for me, and I’m too old, I suspect, to reform now.

But this I do: when nearing the completion of a book, I go away for a week, usually to a place with water or mountains, or both, and hunker down ten to twelve hours a day and edit the whole thing, stem to stern. No paragraph is left unwinnowed. No sentence is left untweaked. No word is left unturned. No comma is left unexamined – even these I hold up, each and all, to a fierce and searching light, squint hard, and ask if this one is a lynchpin, holding everything together, or a grain of sand, clogging the gears.

Even after that, I would never publish a book, or even a lowly article, without one of my ruthless gestapo buddies known as editors giving the thing a once, or twice, or thrice, over. Editors are our friends. Honest. They scowl at us, mutter things that sound like cuss words,

sometimes bare their teeth in fang-like ways, or smile wanly at us, cajole us like we’re sullen children refusing dinner, assure us that our lives are not total wastelands, or at the very least look at us with that weary disbelief that our mothers sometimes use. They often commit against the high art of our writing acts that resemble vandalism. They make us kill our darlings. But we need them. They shame us privately to spare us being shamed publicly.

I have a few small writing rituals. I am not superstitious about these – they’re more force of habit than talismans. But they also help me get into the groove of writing and to keep me there. I sit in my overstuffed leather chair. I pray. I open my laptop, and start. I drink coffee and water, back and forth. I hold silence – no music, no background noise, just the sound of my fingers plunking on the keyboard, and me muttering the phrase I’m currently working on, just to hear it, to see if there’s any melody in it. Only after I have completed three to four hours, and wracked up 1000 to 1500 words, do I let myself get up.

That’s it. No ablutions, no ceremonies, no calling on the muse. I have no muse. There’s no waiting for inspiration to fall on me or rise in me. I’m just a working stiff showing up for his shift, punching the clock, slogging through to the end. I wish for all the other stuff, the magic, the angelic song, the rush of words so fast and wild that I merely hold on for dear life.

But I would never get a thing done if I depended on it.

***

By the way, I currently have three books in the works – one I’m co-writing with my daughter Sarah, one about a small village in France that did remarkable things during World War II, and Book Two of my trilogy of novels on King David. In the next few weeks, I’ll publish here excerpts from all three.

So to begin, here is an excerpt from Book Two of the David Trilogy, David: Reign.

I hope you enjoy.

David: Reign

Book II

Chapter 10 (excerpt)

Balsam Wood

“The king, he hears things, hey.”

“Huh?”

“David. The king. Our king. He hears things. Voices. Or a voice.”

“Like a ghostwife?”

“No, different. Like, maybe like a prophet. Like old Samuel. Or Gad. But also different.”

“He uses the priest for that, right? When the priest puts on the thing with all the shiny stones?”

“The urim and thummim. Yeah, he does that. But he also doesn’t need that. Like, he can go to a place, say, maybe a cave or beside a stream or, I don’t know, anywhere, and sit there all alone. Maybe a hillside. He gets real still, you think he’s sleeping. I watched him do it before. And then God, I guess, comes and talks at him.”

“Like we’re talking now?”

“Yeah. I think so. Don’t know. Maybe. Maybe different.”

“You heard it? You heard God speak at him?”

“No, not me. I saw it, though. You can tell, when it’s happening. He’s not like a prophet, all shuddery and such. He’s not like a ghostwife, all shrieking and tossing around and stuff. He goes real still. He’s like, I don’t know, quarry and stalker all at once. Like a cony and a fox both catch each other’s scent at the exact same moment. You know? That’s the best I can describe it. He’s quarry and stalker both.”

“Huh. What a thing. I fought for Saul all them years. Saul, he wanted that so bad, to hear God speak, even once. Never did, as far I knowed. He went to real strange lengths to try to cover for it. Even drug himself up a ghostwife. But nothing. So David, our king – God talks at him? This happens, what, often?”

“Often enough.”

“Huh. What a thing.”

Two soldiers sit by firelight, eating, slow, the meat they’ve roasted over coals. Night surrounds them like a wall. Another soldier is posted just beyond the rim of light, watching for Philistines, for predators, for intruders. Since David has been crowned king of Hebron, more and more of Saul’s soldiers, and not a few Philistines, have come over to him. They come, like the men in the desert once came, one by one, or in pairs, or small groups. They arrive nursing grudges, nursing wounds. Wary, hungry, angry. Men that Abner or King Achish have no use for, don’t trust, turned away. Men David can’t trust either, but must anyhow.

“It’s not like that.”

The men turn, startled. David steps into the circle of firelight.

“My Lord, I meant no harm.”

“No harm given. May I sit?”

“My Lord, of course.”

The two men shift over on the flat rock they’re sitting on. David sits down beside them, slightly apart from them.

“My Lord, if I may ask, how did you get past our sentry?”

“I killed him.”

The two men look shocked.

“I’m joking.” David laughs. “He is safe and keeps us safe, guards us even now from Goliath’s vengeful brothers. But I am – what? Quarry and stalker both.”

“I meant no harm, my Lord”

“No harm given. But I learned long ago, from having to learn it, to be a shadow in the shadows. A wind on the wind. To the shrewd, God shows himself shrewd. But it’s not the way you describe it, when I hear God.”

The two men wait.

“I think anyone, if they want, can hear God. If they want. You listen. You listen to everything. Birdwing. Cicadas. Wind in grass. The wind in the wind. Even the creatures beneath the ground, the ones that scuttle under the earth. You listen to them. When you get that quiet, that still, you hear something else. Another voice. This one, though, is inside you. It like someone deeper in a cave that you’re already far down in. You go in there to be alone and realize you are not alone.”

“And, my Lord, it tells you what to do, this voice? This other person in the cave?”

“Hmm. It’s more a breath. A breath beside me, inside me, with me. Breath of my breath. Bone of my bone. It speaks without words. It’s louder than words. It’s clearer. Also, gentler. You know how words can be like rocks that have never sat in a creek bed, never been smoothed by water? All those sharp edges? The voice is like rocks smoothed by water. No edges. But that’s not quite it either. It’s more like the water that smooths the rocks. I hear that voice, that breath, and I know what to do. I can’t explain it more than that.”

The men are silent for a long time.

“My lord, that explains everything.”

September 21, 2020

Becoming a Saint

I had breakfast with a friend last week. We each rode our motorcycles to meet up. The day was bracingly crisp, bright but a bit hazy. Steam curled off the river. The aspens had turned shimmery gold, the grasses a wild array of hues.

We’d not seen one another, my friend and I, since the pandemic began in March. There was a lot to catch up on. He’s a musician, and the first thing the lockdown did was dry up a major source of his income – touring his music. He had to figure out other ways to make money. But the lockdown also unlocked things for him – more time with family, a welcome slowing down, a fresh burst of creativity.

I left our breakfast encouraged. But I also left thinking what a mixed bag of things this pandemic is. For some, it’s been a gift – a time of rest, of discovery, of creativity. For others, it’s been a bane – a time of grueling work, or no work at all, of surviving, of rising anxiety. For a lot of us, it’s been both. My days have fluctuated between gratitude and stress, being rushed off my feet and bored out of my mind, fretting one hour, rejoicing the next.

The stuff I treasure: I’ve never walked so much in my life. Or cooked. I’ve written more in the last seven months than I typically do in two years. I built a kayak, and am kind of proud of it, and got to explore the far sides of big lakes with it. I had many evenings laughing and storytelling on the back deck with good friends. My wife and I feel closer than ever.

The stuff I could do without: waking in the wee hours, sick with worry, sometimes wild with panic. Having to scold myself into doing chores. Sitting listlessly and staring blankly, only to grow more listless. Hoarding. Irritability.

And I struggled with a terrible disappointment. It wasn’t over a deep loss. It was over a forced change in plans.

My wife and I were on a sabbatical and were supposed to spend all spring in Europe, mostly in France. It didn’t happen. Well, 12 days of it happened, and then it ended. We were there so that I could do some research for a book (more of which in an upcoming post). But Covid sent us scrambling back to Canada, and back into winter, into an altered reality that we kept thinking would end in a week or so, until we got to wondering if it will ever end.

You know the rest of this story, because it’s some version of your own.

But here’s where worlds collide: Albert Camus, the Nobel Prize winning novelist, lived in the early 1940s in the French village where we spent 12 days in March. It was there he began writing his most famous novel, The Plague (Le Peste in French). It’s about a mysterious and deadly virus that breaks out – in the case of the novel, the outbreak is in only one city, quickly quarantined from the rest of the world. But the plague goes on for months and months, and gets worse and worse. It kills thousands. It alters everything.

Cheryl and I both read The Plague at the height of the lockdown. That made for strange reading indeed, and did nothing to assuage our anxiety. But it also awakened something good in us. Camus was not religious, but his key concern in the book – indeed, in his life – was the idea of becoming a saint: choosing to do the good regardless of the costs, the consequences, or the rewards, either earthly or heavenly.

Camus thought sainthood was the chief goal of life. But his version of sainthood was agnostic, even atheistic. Is it possible, he wondered, that we need no religious motivation to pursue a life of unwavering goodness? Can we be good without God? Camus suggests, not only that it’s possible, but preferable: that pursuing the good with no incentive whatsoever, with no hope of any reward, with no confidence that what I’m doing makes any difference at all – that, Camus thought, is a higher and purer form of sainthood than the religious kind.

I’m not convinced. But I am challenged. Since reading The Plague, I’ve been asking myself why I do what I do. Do I do the right thing simply because it’s the right thing? Or am I always, at least in the back of my mind, seeking some reward, some human or divine “Atta boy!”?

This past weekend I was boating with two friends. We saw a dinghy, tied to a buoy, that was swamped with water. The boat was sunk down to its gunnels. Another wave or two would sink it completely.

We debated whether to bail it or not. All we had on hand was a small plastic cup, so this was a big undertaking. One of my friends said, “Let’s do it. Maybe God will give us extra points.”

“Or maybe,” I said, “the boat owner will see us and thank us lavishly.”

We all laughed. We all bailed. And then we carried on.

But I left wondering if God loves it best when we do the good for no points and no thanks at all.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

I also had two books launch in the past six months. I invite you to check them out, and let me know what you think.

[image error][image error]

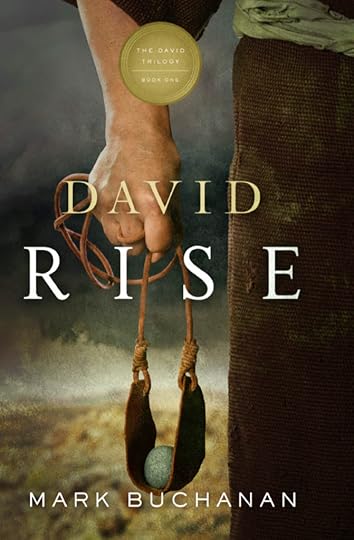

DAVID: RISE

God Walk

July 23, 2020

God Walk

March 19, 2020

DAVID: RISE – Released Today

I fell in

love with David’s story, if not always with the man himself, when I first read

the Bible at age 21. Since then, I have gone back to his story many times to

find my bearings, to figure out both how to live and how not to live, to the

point where David’s story sometimes feels like a part of my own. Years later, I

began to immerse myself in the extensive secondary literature on David and his

times (a bibliography of works is included at the back of the book). These

secondary sources confirmed, clarified, amplified, and sometimes corrected my

growing sense that David represents an historical and literary figure of

immense complexity and vitality whose life repays careful study and reflection

regardless of one’s own personal beliefs.

In

2009, sitting on a sandstone beach on a small island near Victoria, BC, the

beginning of this work came to me, unbidden. It came in the form of an almost

auditory experience: I “heard” Michal, David’s first and later estranged wife,

as an old woman thinking back on her life with David. She spoke with bitter,

rueful incisiveness. On the spot, I wrote down what I heard.

The

novel took another 10 years to complete, with many rabbit trails, false starts,

dead ends. In 2018, I decided to break the story into three parts and publish

it as a trilogy, beginning with this present book, David: Rise, which traces the story from David’s “birth narrative”

in the story of Ruth to David’s coronation in Hebron as king of Judah. In the

forthcoming Book II, David: Reign, I

will trace the story over the seven years of civil war between the House of

Judah and the House of Israel through to David’s ascension to the throne over

Israel at age 37, his establishing of a new capital called Jerusalem, and his

expanding and consolidating his rule over Israel. The trilogy will conclude

with Book III, David: Descend, which

will cover the final two decades or so of David’s life, beginning with his

encounter with Bathsheba and ending with his death. Book II is slated for

release in 2021 and Book III in 2022.

This

trilogy is a work of fiction. Though I have made every effort to be faithful to

the David story as it comes to us in Scripture, particularly in 1 and 2 Samuel,

and have drawn widely on academic, popular, and artistic depictions and

interpretations of David and his times to ensure biographical and historical

accuracy, I have also taken many liberties. The biblical account of David is

silent or sparse on many details of character, setting, and chronology, and our

historical and archeological knowledge about the man and his times is partial

and oftentimes tentative, and so my depictions of any given character – his or

her physical appearance, emotional states, deep motivations, inner and often

outer dialogue – or any given event – its timing, setting, dynamics – is

oftentimes imagined. In some instances, I have wholly invented characters and

scenes, though always attempting to be true to the story’s cultural, biblical,

and narrative context.

One hope I have in publishing this novel, and the two novels that will follow it, is that you, the reader, will go back and read the original story of David.

Paperback is available now, E-book will launch March 31st. 2020

March 12, 2020

Coming Soon:

1025 BC

David

He stands naked before the wind. It pummels him with

fists of gusting. It pulls his hair sharply back, tugs hard his flesh. It

scours all that is loose in him. He opens his mouth to swallow it. It empties

him and fills him. He anchors down his heels against the massive weight of the

wind’s wild blowing, and pushes himself into it to stay upright.

The sensation is of

flying.

Many things come hard

for him – speaking with his father, dealing with his brothers, watching his

mother’s mute anguish – but this comes easy: opening himself wide to the wind,

the breath, the ruach. Bending

himself whole to it. Letting nothing – no cloak, no shield, no armor, not even

his tunic – come between him and whatever the ruach does in him, however the ruach

does it.

Here he is in his

element. Here all things are clear. Here all things are possible. He is truly

fully undividedly himself.

He is David.

***

This is the best part of the day. The sun is down, but

night still waits to spread its cloak. Darkness is only a rumor at the edge of

earth. Colors drench the sky. Wind sweeps fields and drives out wilting heat.

The white stones that knuckle the hillsides glow. Jasmine releases its perfume.

Olive leaves, like handheld mirrors sending cryptic signals, flash silver.

And everything wakes.

Birds burst with one last fanfare of song, one last flourish of flight. Insects

in grass and sky whirr, and click, and thrum. Animals scuttle, groundlings

slither.

The sheep rouse with

fresh hunger.

And he rouses, too. The

langor of mid-day falls off him in a rush. He is quick and light, keenly

watchful.

Which

is good. Which is needed. Because the lion rouses, too.

He

loves this. This alertness in himself. His own sheer aliveness. The deep

calling to deep within him, like the roar of a waterfall. The air shimmers

bright, as if angels are about to sing. He steadies him, readies himself for

come what may.

He

rubs the pocket of his slingshot warm and soft, and then cradles in it one of

the stones he’d plucked from the stream this morning. It’s round and smooth and

green. It will be a shame to lose it. But an instinct, sharp and urgent as a

thorn, tells him he’ll need it, and soon.

He’s

asked his father Jesse three times for a proper weapon. A sword or a javelin.

He knows his father keeps a smithy hidden in the hills above their farm. The

Philistines have banned all smithies, to keep Israel from arming herself.

Farmers who need a hoe or rake or adze made or repaired must travel to Gath or

Ashkelon and hire a Philistine blacksmith, who charges double, sometimes triple

the price. Then the farmer is checked as he leaves Philistia, to make sure he

has paid no bribe to acquire a small sword or dagger. It is one of many reasons

the people hate the Philistines. And it is one of many reasons they are starting

to resent their own king, Saul: his weakness has reduced them to this thrall,

this humiliation, this smallness. In taverns and fields, men whisper to one

another a question that has dogged the king his entire reign: “Can Saul save

us?”

Jesse has taken matters

into his own hands. Every week or so, he goes out at nightfall to his smithy

hidden in the hills and works until daybreak. The cover of night hides the

smoke trail from his furnace that vents through a crevice of rock. He blocks

the cave entrance with thick bramble and foliage to deaden the ring of his

hammering on the forge. He comes down in early morning with a bundle on his

back wrapped in thick cloth. When he unfolds the cloth, sword blades, spear

heads, spikes clank out. He’s given weapons to his three oldest sons, and

trained their hands for war. Now he sells weapons to other farmers.

He’s never given one to

David.

“You are a shepherd boy.

You have a slingshot. You have a knife. What more do you need?”

***

The sun-starched land turns blue with shadow. David

rises to gather his sheep. As he steps down from his perch, he sees a deeper

shadow move swift and furtive between rocks. A lone sheep is just beyond the

fastness of those rocks. The sheep’s neck is bent to a lush tussock of grass.

It is oblivious to danger. David runs down the steep incline, zigzagging, and

when he reaches the valley floor he sprints straight.

The sheep is still

grazing. The lion, he guesses, is still crouching behind the rock.

Then the lion, quick as

thought, bursts its cover. David is still a hundred paces away. He cannot catch

it. His sling hangs ready in his left hand. He begins the rapid switching

motion in his wrist that makes the sling’s long tethers loop faster and faster.

It becomes a transparent whorl of air, a thin sharp whistle of sound. He moves

the twirling sling above his head, and then slightly behind it. The lion is so

locked in its bloodlust it doesn’t hear him coming. The sheep raises its head,

suddenly aware of death thundering down. It freezes.

David

can see the lion slowing, coiling on its haunches, preparing to lunge. He picks

a spot where he reckons it will be in the next few seconds, stretches his right

hand to steady his aim, and looses the stone.

The lion crouches full

on its hind quarters, and takes air.

He watches the stone

pierce the dying light. It hastens like a messenger with news of war. It finds

its mark, the back of the lion’s skull. The beast lands hard and staggers

sideways with the blow. The sheep, snapped from its stupor of terror, bolts.

The lion shakes its

head, slow and heavy. It gains its footing, and turns toward David. He still

runs toward it. The lion stands wavering, confused. It takes a few massive

leaps toward the sheep’s retreat, then wheels and comes straight at David.

He

tucks his sling into his pouch and, still running, unsheathes his knife. The

lion regains its strength. It runs at him full-tilt then shifts into a

rearing-up motion, ready to sail at him. David has been counting on this, the

animal’s precision of reflexes. He runs harder. When he and the lion are almost

on each other, the lion leaps. David dives under it, spins on his back. The

animal’s huge body eclipses the sun. Its shadow swallows him whole. As it flies

over him, its taut underbelly almost grazing him, he plunges his knife in its

stomach to the hilt. He holds on with both hands. He feels the massive body

shudder through his blade. The lion’s belly opens like tent flaps. The insides

rush out hot. David rolls away just before it spills out on him.

The

lion hits the ground on its shoulders, and tumbles, and sprawls. It tries to

get up, but can’t. David walks up to it, laid out in its own lake of blood. The

lion turns its head and bares its teeth. No sound comes out. Its yellow eyes

grow dim. It flops its great head to earth, panting. David places his hand flat

on the warm flank of its heaving chest. He holds his hand there, feels the

heart of the animal slow, slow, slow. The lion closes its eyes and stops

breathing.

He

walks over to where he first hit it. On the ground, his green stone looks up at

him like an eye. He picks it up, rolls it in blood-warm hands, and then washes

both in the stream.

He

gathers his sheep and heads home.

Happy to have his sheep

safe. Happy to have his stone back.

(David: Rise Book One releases late March 2020. Watch for early release details and specials.)

March 13, 2019

2019 Writing Retreat

Two spots remaining

Beautiful Keats Island – A Place to be inspired.

Interested in a week-long Writing Retreat on a tranquil island on the west coast with the option of personal coaching by a professional published author?

Here is an opportunity to sharpen your skills, deepen your passion, learn a few new tricks, and practice your craft – plus enjoy good company, amazing food, all in a spectacular setting.

Mark Buchanan will lead a “working retreat” for a small group of writers from May 26 – 31, 2019 at Barnabas Retreat Center on Keats Island, BC www.barnabasfm.org Mark is the author of 8 published, award-winning books, including the bestseller The Rest of God, has 3 more books on the way, and has published over 100 magazine articles. www.markbuchanan.net

The retreat begins Sunday May 26, with an afternoon boat ride from Horseshoe Bay in Vancouver to Keats Island, and ends Friday May 31 with lunch and boat ride back to Horseshoe Bay. All other travel arrangements are the responsibility of each couple or individual.

Our time together includes:

5 nights in lovely hotel style retreat center, with ocean & mountain views, eagles, orcas, and west coast beauty to inspire your creativityAll meals and snacks, fresh from the farm & garden, home made, nutritious and delicious.Chartered water taxi to & from Keats Island (from Horseshoe Bay)The option of bringing your spouse (see below; sorry, no children or infants)One hour each day of group instruction from MarkSeveral hours each day to writeOption of two 45-minute private coaching sessions with MarkSeveral hours each day to rest, relax and enjoy your surroundingsOpportunities each evening to gather together to read and discuss your writing

This event is limited to a maximum of 10 writers at any skill level, so please register quickly.

Costs:

$1850 – Per person, Single Occupancy plus 2 coaching sessions$1650 – Per person, Double Occupancy plus 2 coaching sessions$1600 – Per person, Single Occupancy, no coaching$1400 – Per person, Double Occupancy, no coaching

To register with a $300.00 non-refundable deposit or for more information, please contact Cheryl at cheryl.buchanan63@gmail.com

November 30, 2018

2019 Writing Retreat with Mark Buchanan

Only one writing retreat offered in 2019

Interested in a week-long Writing Retreat on a tranquil island on the west coast with the option of personal coaching by a professional published author?

Here is an opportunity to sharpen your skills, deepen your passion, learn a few new tricks, and practice your craft – plus enjoy good company, amazing food, all in a spectacular setting.

Mark Buchanan will lead a “working retreat” for a small group of writers from May 26 – 31, 2019 at Barnabas Retreat Center on Keats Island, BC www.barnabasfm.org Mark is the author of 8 published, award-winning books, including the bestseller The Rest of God, has 3 more books on the way, and has published over 100 magazine articles. www.markbuchanan.net

The retreat begins Sunday May 26, with an afternoon boat ride from Horseshoe Bay in Vancouver to Keats Island, and ends Friday May 31 with lunch and boat ride back to Horseshoe Bay. All other travel arrangements are the responsibility of each couple or individual.

Our time together includes:

4 nights in lovely hotel style retreat center, with ocean & mountain views, eagles, orcas, and west coast beauty to inspire your creativity

All meals and snacks, fresh from the farm & garden, home made, nutritious and delicious.

Chartered water taxi to & from Keats Island (from Horseshoe Bay)

The option of bringing your spouse (see below; sorry, no children or infants)

One hour each day of group instruction from Mark

Several hours each day to write

Option of two 45-minute private coaching sessions with Mark

Several hours each day to rest, relax and enjoy your surroundings

Opportunities each evening to gather together to read and discuss your writing

This event is limited to a maximum of 12 writers at any skill level, so please register quickly.

Costs:

$1850 – Per person, Single Occupancy plus 2 coaching sessions

$1650 – Per person, Double Occupancy plus 2 coaching sessions

$1600 – Per person, Single Occupancy, no coaching

$1400 – Per person, Double Occupancy, no coaching

To register with a $300.00 non-refundable deposit or for more information, please contact Cheryl at cheryl.buchanan63@gmail.com

What people are saying about Mark Buchanan’s retreats:

“I came with high expectations and it exceeded all of them. It was productive, instructive and relationally rich. I just didn’t leave a better writer, I left a better person and follower of Jesus. Thank you, Mark and Cheryl!” BA-M, Calgary

“What a great retreat. The food and fellowship with one another were tremendous. The spiritual component of praise and prayer and quite reflection was truly life-giving. The tips and tricks from the trade of writing that Mark provided were thoughtful, instructive, and helpful. The space provided to reflect and write, the ease with which we were encouraged to share our work, made for a fun-loving and dynamic atmosphere and experience. This is a first rate retreat. Mark and Cheryl led us with tremendous skill and insight, and I know for sure, I am a better, more aware writer, than when I arrived. Well done Mark and Cheryl and God’s blessings to you as you continue to provide your gifts to those who love to read and write!” IH, California

“I came with a dream, I left with a plan. I don’t think I’ve ever had such a meaningful and transformative professional development experience. My vague ideas were transformed into a clear vision through an ideal blend of the practical, the inspirational and the supernatural. Times of instruction, reflection, devotion, relaxation and discussion combined in a luxurious setting to fuel the creative process and nourish the writer’s spirit. Mark is abundantly generous of himself and his gifts in encouraging other writers, and you will be blessed by ample portions of his technical know-how, his creative genius, and his pastor’s heart.” KS, Victoria

February 1, 2018

Let the Sermon be Interrupted

The Church, First Nations and Reconciliation

i

“Rabbi, tell my brother to divide the inheritance with me.”

Once again Jesus is interrupted. It must happen to Him a dozen times or more. There He is, preaching some jaw-dropping piece of good news, and next thing the roof is coming apart, or a demoniac is shouting Him down, or a teacher of the Law is standing up to test Him, or Sadducees are lining up to trick Him, or Pharisees are cooking up a trap to ensnare Him.

But many people just want something from Him. Most who interrupt Him are simply preoccupied with their own stuff. They’re caught up with some earthy, urgent, agonizing matter that can’t wait for the sermon to end. They want answers to vexing questions, and they want them now. “Who is my neighbour?” “Good Teacher, how do I inherit eternal life?” “Son of David, have mercy on me – cleanse me, heal me, restore me!” “Lord, tell my sister to help me in the kitchen.”

That’s the story in Luke. A man crashes into the middle of Jesus’ sermon with his urgent demand. “Rabbi, tell my brother to divide the inheritance with me” (Luke 12:12). Well, that man does have a point. It’s hard to listen attentively to a sermon when your brother just bilked you out of your share of the family estate. A thing like that tends to consume all your energy.

A thing like that is powerfully distracting.

Many of my First Nations friends have difficulty listening to sermons. There are many reasons for this – some personal, some cultural, some historical – but much of it comes down to the issue of justice. They got bilked out of their share of the family estate. Land. Language. Children. A way of life. All and more were taken from First Peoples. And sometimes they itch to interrupt all our ethereal business about heaven and love and God and such with a burning request. “Jesus, tell my white brother to divide the inheritance with me.”

Well, they do have a point.

But actually that’s not quite what First Nations people, at least the ones I talk with and listen to, are asking. Dividing the inheritance is not exactly their request, or not the things they ask first. Almost every First Nations person I know wants something else, something deeper. “Jesus, tell my white brother to reconcile with me.”

I suggest this is worth interrupting our sermons.

And yet, is reconciliation even the right word? Many First Nations people don’t think so. Many observe reconciliation implies restoring the relationship to a former level of mutual warmth and trust and affection and intimacy. In most cases no such former relationship ever existed between Indigenous people and European settlers in Canada. In most cases our relationship has been marked by suspicion and distrust. In most cases we were never close.

What we need is a new story. A fresh beginning. A do-over. But to get to a new story, all of us must first become keenly aware of – and, I suggest, deeply troubled by – the story we actually have.

That was the hope that launched Canada’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC). The TRC was established to examine the history and legacy of Canada’s “Indian residential schools” and bring some closure and healing for those who suffered there.

The TRC was struck in 2008, launched in 2009 under the leadership of Justice Murray Sinclair, and wrapped up in 2015. The commission issued a seven-volume report which contained 94 Calls to Action. The work of the commission continues through the National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation housed in the University of Manitoba.

In the seven years the TRC was active, the commissioners, along with many participants, heard the testimonies of more than 6,000 residential school survivors. These testimonies, taken together, are devastating, and yet strangely and profoundly inspiring. They narrate a long tale of abuse, neglect and evil, but also tell a story of resilience, courage and grace.

But note this: the TRC was initiated by First Nations people, featured the testimonies, almost exclusively, of First Nations people, and was attended mostly by First Nations people. It was the idea and work of First Nations people from start to finish. All with the aim of reconciliation. Not blame. Not restitution. Not score settling. But reconciliation – of getting the story straight so now, hopefully, we can begin a new story.

Non-Indigenous people in Canada should stand amazed and grateful and humbled by this. After all that’s happened, First Peoples still hold out a hand of friendship to us.

But many of us have just ignored it.

About 14 years ago, I started a small effort to get Christians to start caring about the Church’s relationship with First Peoples, and to inspire Christians to be at the forefront of creating a new story. I’ve talked to hundreds of people about it. I’ve spoken in dozens of churches on it. I’ve lectured at colleges and universities regarding it. I’ve been involved with several conferences dealing with it. I’ve written a number of articles focused on it. I have helped organize local initiatives around it.

One of these initiatives is even called New Story. It’s an all-day teaching event to help Christians understand the history and culture of Indigenous peoples, both nationally and locally, and what we as churches and individuals might do next.

AFTER ALL THAT’S HAPPENED, FIRST PEOPLES STILL HOLD OUT A HAND OF FRIENDSHIP TO US.

I am seeing some things that give me hope. A growing number of churches, for instance, now open their Sunday services with an acknowledgement of the traditional lands on which they are situated. A few churches welcome, at least in small ways, some form of Indigenous worship in their Sunday gatherings.

More and more Christians are learning the beautiful and unique contributions First Peoples bring to the reading of Scripture. Genesis 1, for instance, depicts not humankind’s superiority over everything in creation, but our dependency on everything in it. Humans need air and water and light and fish and flocks and fruit to survive and flourish, and yet none of these things need us. Everything else in creation flourishes independent of our existence.

But I am also seeing in our churches many things that cause me distress. Continuing bigotry. Abysmal apathy. Deep contempt. Condescension. Resentment. Defensiveness. I would love to see all this change. And if you would too, here are a few things that can begin that change – a few steps toward a new story.

LEARN THE HISTORY

I am still astonished how few people in our churches know about the Doctrine of Discovery (the papal bull from 1493 upholding the divine right of Christians to take land from its “savage” inhabitants), Terra Nullius (the legal claim that “empty” territory belongs to the state that occupies it), the history of treaties, the history of colonialization, the history of the Indian Act, the history of Indian residential schools, and the current struggles and achievements of Indigenous peoples and communities in Canada.

And still fewer know anything about the local tribes and bands within driving distance of their church and home.

Why not strike up a church study group that, over the next few months, becomes well informed on all these things and then informs others?

DISCUSS THE SITUATION

There are many things the group might read and discuss, but I suggest you start with three things – Volume One of the TRC Final Report, the United Nations Declaration of the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (which is underneath much of the TRC’s work and recommendations), and the 94 Calls to Action that emerged from the TRC. I suggest your group focuses on Calls 58 through 61, which specifically address the Church and its supporting educational institutions. (On a side note, I find it stunning Canada’s First Nations people issue 94 Calls to Action, but ask only four things from the Church.)

MAKE A STRATEGY AND TAKE ACTION

The next step might be to come up with a strategy for your entire church to respond to one or two of the Calls to Action. For example Call # 60:

We call upon leaders of the Church parties to the Settlement Agreement and all other faiths, in collaboration with Indigenous spiritual leaders, Survivors, schools of theology, seminaries, and other religious training centres, to develop and teach curriculum for all student clergy, and all clergy and staff who work in Aboriginal communities, on the need to respect Indigenous spirituality in its own right, the history and legacy of residential schools and the roles of the Church parties in that system, the history and legacy of religious conflict in Aboriginal families and communities, and the responsibility that churches have to mitigate such conflicts and prevent spiritual violence.

i

One local church I know gathered a group of about ten people who spent several months discussing how their church might respond to this one Call to Action. That led to an evening where the group hosted a Blanket Exercise (www.KairosBlanketExercise.org) for the entire congregation. They also invited several elders from the nearby First Nations community.

This one initiative broadened the conversation, and soon several members of the church were meeting regularly with some of the elders to discuss ways they might work together. That led to several youth from both communities meeting every week, sometimes at the church, sometimes at the community.

That led to real friendships and that led to transformation.

What might your local church do?

REAL FRIENDSHIP

That last story brings us to the most important thing – real friendship. It still surprises me how few people in our churches have even one Aboriginal friend.

That was me a few years back. Indeed it was me for most of my life. Until about 15 years ago, I didn’t even know a First Nations person.

Then I became good friends with one First Nations man. That opened the way for other friendships. And the more First Nations people I got to know, and the more I learned their stories and came to know their hearts, the richer I became. My First Nations friends are funny and kind and generous and wise. And they are hurt and sad and wary and angry. But they still want to be my friend.

I have gained and grown much from these friendships. I discovered I need my First Nations friends more than they need me. I need my friends to be my teachers and examples and guides. I need them to show me how to live out my faith more fully and authentically – to pray with deeper faith, to share with greater joy, to stand up more bravely under trial. I have learned from them what it means to forgive from the heart. And I have learned from them the true meaning of resilience.

Every new story is rooted in friendship and leads to deeper friendship. That’s where the real transformation happens.

Canada’s TRC, intended to address the history and legacy of RSs, followed the pattern set by other country’s TRCs, such as the one in South Africa. The South African TRC was intended to address the history and legacy of Apartheid. But there is a significant difference between Canada’s TRC and those of other countries. In South Africa, as in other countries, the TRC was tribunal in nature. That meant that it included the testimonies of over 2000 perpetrators – those who engineered and carried out the policies of Apartheid, those who benefitted from it, but especially those who enforced it, often by brutal and illegal means: police, for instance, who committed extra-judicial murders to silence political dissent.

IT STILL SURPRISES ME HOW FEW PEOPLE IN OUR CHURCHES HAVE EVEN ONE ABORIGINAL FRIEND.

In Canada, for various reasons, the TRC was non-tribunal. In practice this meant that it heard virtually no testimony from anyone who “ran the system”: no government agent who scooped a six-yearold from her home and dragged her away from her wailing mother, no priest who summoned a 12-yearold boy to his study and sexually abused him, no nun who broke a little girl’s neck throwing her down the stairs, no teacher who publicly mocked and humiliated a student for peeing his bed, no school administrator who saw all this and turned a blind eye.

None of them said a word.

Which is a problem. Because – well, think about it. What if you suffered deep harm at the hands of another person, told your story publicly, and all the while the person who harmed you seemed neither to notice or care, and just stayed silent?

It would, at the very least, be hard after that to reconcile with that person. And it would be hard to reconcile with anyone associated with the system in which that person operated. It would be hard to begin a new story. Which is why this all comes down to you and me. Will I too stay silent? Will you?

Let us begin.

Reprinted from FAITH TODAY, January 2018