Frater Acher's Blog

April 18, 2023

Do You Know Your Magical Ethos?

The only question more pertinent than whether you actually have any magic at your command, is whether you have a magical ethos?

The etymology of the word ethos points us to the genius of a person, a habitual character or disposition. In short, the question of a magical ethos asks us to be clear about what kind of human we want to transform ourselves into through the use of our magic. Whether this transformation is the actual goal of our magic or whether it happens as a side effect and backlash of the magic we use to change the world is irrelevant to the question of ethos. Actions speak louder than words, as the saying goes. Likewise, it is our magical conduct that creates our individual ethos as a side effect.

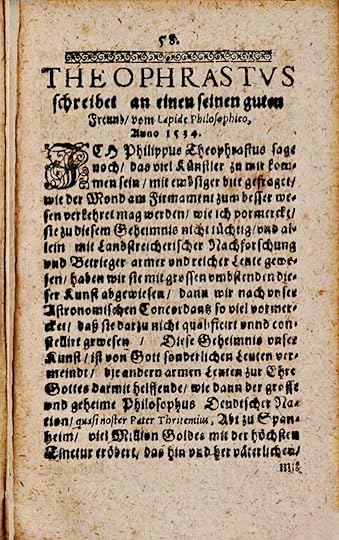

We will not digress into the depths of angelic magic here, and explore how the human ethos unfolds from the influence of those non-human persons in whose proximity each of us chooses to settle. After all, becoming alike to the angelic-mind, was not only Trithemius’ disguised motto in life, but also the exploration we have been undertaking in the Holy Daimon cycle, plus INGENIUM as its fourth instalment.

This short article takes a much more practical approach to the question of ethos. In short, we want to ask: Under which circumstances are you willing to apply magic? And when these circumstances occur, how will you be applying your magic?

In a world where we are all constantly caught in the crossfire of new technological advances and constant competition to prove one’s superiority in the use of such techniques, the question of ethos tends to get short shrift. Unfortunately, this is equally true in the technical, economic, ecological and magical world of our century. The What dominates the discussion about the What for in a narcissistically grandiose scheme.

With the question of when and why of the application of practical magic now a central problem arises. This we want to circumnavigate in a makeshift way here, because it would lead us into a completely different direction. This problem is that the notion of magic as a canon of clearly delineated disciplines is not always accurate.

For example, if we consider the herbal magic of the natural world, it begins not with a tincture of belladonna brewed at midnight under the blessing of Hecate, but with every morsel of food we eat. When we look at astro-magic, we equally cannot avoid it as every action we take is subject to astrological constellations. Similarly, with those non- human persons who are directly interwoven with the human environment: Certain land-beings, plant-beings, wind-beings, etc. are constantly in our vicinity. And if we go a step further, as shown for example in Holy Heretics in relation to the Olympic Spirits and their influence on the human body, we cannot escape the constant weaving of these inner presences either.

Despite these complexities, whether we like it or not, over a lifetime of magical practice, we will all end up having created our own magical ethos, consciously or unconsciously. Now, a simple way to become more aware of this ongoing process is to consider under which circumstances, we switch from purely mundane means for addressing a desire, concern or problem, to explicitly magical ones. It is no different from the situation we’d all recognise in the world of medicine: Here, too, we have the choice of treating a concern through changes in the client’s daily routine (exercise, diet, life-style, location, etc.) or intervening through targeted, more potent medications.

All of these were my reflections, when I recently came across a curious article on 13 medical commandments for beginners. Ayman Yasin Atat in a paper from 2014 had quoted them from an ancient Arabic manual, dating to the early 13th century. The original book is called Kitab Intikhab al- iqtidab and was written by Abu Nasr Sa’ed al-Baghdadi, an eminently important physician of his time. Following the idea of the Hippocratic Oath, these simple directives lay out before us a dozen ethical maxims to help the physician apply their art with prudence.

So, what could be more obvious, I thought, than to test whether these maxims could be translated into the outlines of a magical ethos? Without claiming completeness or universal adequacy, I share here my first attempt to translate these precepts adopted to our craft. These ancient guidelines and my new renderings of them, of course, should not invite for uncritical acceptance, but for personal examination, purposeful objection and individual appropriation in your own version. Because prudence ultimately is not an objective category. It depends entirely on what you want to achieve and the price you are willing to pay for it. It also depends on the ethos you are willing to accept as an implicit or explicit requirement on this journey.

Personally, I took several meaningful reflections from this little exercise. In my case, I do not offer magical services to clients. Therefore, this translation of old Arab maxims challenged me to clarify whether I meet their aspirations in the practice that I uphold as a lone practitioner? For example, have I really tried all my magical interventions first in situations where I was not yet dependent on their success? Have I really only ever used the specialist-spirit and been wary of ‘broad-spectrum conjurations’? Or, have I indeed always exhausted my mundane means before turning to explicitly magical acts?

Whatever my answers turned out to be, I invite you to examine your own. As always in life, things that are presented to us as possible dogma or maxims, let’s take them as suggestions to further our own experimentation.

So to start with, let me share the complete set of thirteen principles in a single paragraph, as they originally appear in Abu Nasr Sa’ed al-Baghdadi’s book. Then, I am providing a break down of each principle in its original and adopted version side by side, to facilitate slower reading and better reflection on each statement.

Early 13th Century Original for Medicine:Possible Modern Adoption for the Black Arts:The power of the patient is stronger than the disease, there is no need then for a physicians or medicine but particularly the strengthening of the body’s immune. Physicians first control pulse and the eyes of the patient. Pulse plays an important role in the knowledge of the condition of the heart, and the eyes and their focus gives us the situation of brain. If physician can treat the patient with food, there is no need for the drug. If you can treat the patient with mild medicine, there is no need for strong one. If you can treat the patient with one medicine, there is no need for more than one. Don’t prescribe the drug before expert it. The experience of the drug should be check primarily on healthy volunteers. When you need to treat 2 diseases at same patient, you must begin deal with the most dangerous one to save the life. When patient desire something like foods, drink, give him it. You must take care about the patient desire of method of treatment. You must relieve the patient’s pain. You must know the whole clinical history of patient. You must know the disease before begin the medication.

1st PrincipleIf the ability exists to resolve the concern through mundane matters, no magician or magic is needed. Where a magical intervention is advised, the magician first checks the client’s constitution and resistance to possible side effects. If the client’s concern can be addressed through herbal magic, there is no need to involve more potent magical interventions. If we can help the clients with mild magic, we do not need strong magic. If we can resolve the client’s concern with a single intervention, there is no need for more than that. We do not prescribe or perform magical acts on which we do not have expert knowledge. The experience with the magical procedure should first be made in a situation without dire need. If you have two concerns to address with one client, you need to start with the more dangerous one. If the client feels like exploring certain places, books, or foods as part of the intervention, we encourage them to do so. We must be careful that the client supports our method of intervention; resistance or any hesitation must be respected. Our intervention starts where the client is most impaired in their daily life. We need to know the magical or spiritual story of the client. We need to know the root cause that is causing the concern before we begin the intervention.

Original:

The power of the patient is stronger than the disease,

there is no need then for a physicians or medicine.

Adopted: If the ability exists to resolve the concern through

mundane matters, no magician or magic is needed.

Original: Physicians first control pulse and the eyes of the patient.

Adopted: Where a magical intervention is advised, the magician first checks

the client’s constitution and resistance to possible side effects.

Original: If we can treat the patient with food, there is no need for the drug.

Adopted: If the client’s concern can be addressed through herbal magic,

there is no need to involve more potent magical interventions.

Original:

If we can treat the patient with mild medicine,

there is no need for strong one.

Adopted: If we can help the clients with mild magic,

we do not need strong magic.

Original: If we can treat the patient with one medicine, there is no need for more than one.

Adopted: If we can resolve the client’s concern with a single intervention,

there is no need for more than that.

Original: Don’t prescribe the drug before expert it.

Adopted: We do not prescribe or perform magical acts on which

we do not have expert knowledge.

Original: The experience of the drug should be on a healthy person.

Adopted: The experience with the magical procedure should first

be made in a situation without dire need.

Original:

When you need to treatment two diseases at same patient,

you must begin deal with the most dangerous one.

Adopted: If you have two concerns to address with one client,

you need to start with the more dangerous one.

Original: When patient desire some thing like foods, drink, give him it.

Adopted: If the client feels like exploring certain places, books,

or foods as part of the intervention, we encourage them to do so.

Original: We must take care about the patient desire of method of treatment.

Adopted: We must be careful that the client supports our method of intervention;

resistance or any hesitation must be respected.

Original: We must relieve the patient’s pain.

Adopted: Our intervention starts where the client is most impaired in their daily life.

12th Principle:Original: We must know the whole clinical story of patient.

Adopted: We need to know the magical or spiritual story of the client.

13th Principle:Original: We must know the disease before begin the medication.

Adopted: We need to know the root cause of the concern before we begin the intervention.

December 24, 2022

In the Forest of Truths

Imagine you are walking through a dense forest. The light falls through thick crowns in sharply cut shadows, and everything seems to be in motion. You smell the scent of mosses, of rotting leaves and damp earth, and with no particular destination in mind, you walk deeper and deeper into this forest.

Now imagine that every tree you encounter on this walk, whether old or young, small or large, represents the human belief in a particular truth. Here is the grove of the Christian truths, and there, without the beginning and the end being distinguishable in any way, it merges smoothly and is interspersed with the trees of the Jewish, the Muslim, the pagan, etc. truths. Truth-trees everywhere in this sprawling, majestic, wild forest.

And so, we keep on walking through the forest of truths. Occasionally we stop, look at a tree from close up, the patterns of its bark, the strength of its trunk, and how it branches out with crown and roots into the neighbouring trees. Here or there, we discover two trees that appear to be completely intertwined, yet bear entirely different flowers…

As in every expedition, we enlarge the perimeter of the world we know with every step we take in the forest of truths. What is important in an expedition, however, is not to lose perspective: No matter how beautiful, impressive, even powerful or magical individual trees may appear to us in the forest of truths, we never forget that they would be nothing without the rest of the forest. Only together can they grow, thrive and sustain themselves in eternal diversity and change.

Now let us imagine that there are other living beings roaming this forest besides ourselves. Unknown beings they are, finding their ways among these trees, glades, and groves. Most humans never meet these presences eye to eye. Instead, most humans recognise them only by the traces they leave on the trees of human truths: A hollowed-out knothole, the bark of a trunk stripped of moss and torn open, young twigs bitten off, a deeply dug cave among the roots. Truths show the traces of the beings that once inhabited them. And truths, like trees, are deeply conditioned and shaped by the life that flows around and through them…

Now you must know, most people roam the forest of truths to choose as quickly as possible a pleasant tree under which to rest. They become settlers in the shade of this tree; they have found their truth and bind themselves to it with their own hearts and roots.

As magicians, however, we roam the forest of truths with the firm intention of never settling down. More than that, we create our path in this forest not searching for even more, even larger, or even more magnificent trees, but searching for those presences that move among them. The marks they leave on the trees merely serve as markers for us to follow the paths of these beings…

Sometimes, on the best of our days or nights, we catch a glimpse of these presences living with us in the forest of truths. Just like them, we live nomadic yet bound to certain recurring paths in the vastness of this forest. Like these invisible beings, we return to certain trees, allow them to anchor our orientation, and experience moments of confusion and distress when age brings them down. Some of these trees give us nourishment, the barks of others appear poisonous; often during our lives their effects seem to interchange.

As magicians in the forest of truths, we are not hunters. We do not shoot or kill game. We walk and search for presences, and on our paths we understand that we ourselves are such a presence… We all create this forest together, and without us, it would be nothing but desert. Likewise, we understand that the way we move through this forest attracts different types and beings of presences, which then accompany us for a while on our paths. Anyone who first enters the forest of truths feels alone and somewhat lost here. Only after years of wandering do most of us come to the realisation that we are actually never alone. Quite the contrary: usually a whole hoard of presences moves with us, and their presence colours and conditions how we see the trees around us. Their shadows pass overhead, their scent mingles with the trees, and their thoughts mingle with ours.

Life in the forest of truths is as diverse as the trees within it. To preserve it and become a living part of it, we have understood that there are three things in particular for as nomadic magicians to consider:

A settled human in the forest of truths quickly turns toxic to their environment. They begin to forget the very idea of the forest as a hive, that life is only possible in messy compounds, and, instead, they begin to fight for resources for their tree…

Our ability to understand not just one tree, but the forest as an ecosystem, is a direct function of how much we can refrain from the human instinct to judge everything. Observe not judge is the magician’s motto in the forest of truths.

And despite the majestic size and power of some of the old trees in this forest, we have learned never to delude ourselves that even one of them can last forever. Every tree dies and will eventually fall. Then it will be overgrown by new life, decomposed by fungi, and become the soil for future truths.

What always remains, never fades as long as we walk these paths, is the surging, proliferating, magical life that roams this forest and sustains it. Nothing exists here without the wandering of the presences — most of which we recognise only after years of wandering in the shadows of these trees. Indeed, the calm, immovable tranquility of the trees is symbiotically united with its very apparent opposite: the effervescent meandering of presences that surrounds and weaves through them.

May we all succeed in this exercise. May we all remain light-footed in the forest of truths. May we all become good rangers among our brethren presences. As tiny as the meaning of each one of us is, as powerful and mighty it is as a wandering species.

October 21, 2022

Holy Heretics - Introduction

View fullsize

View fullsize

View fullsize

View fullsize

View fullsize

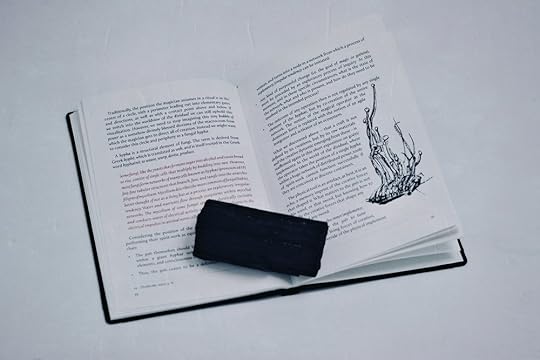

Thank you for your interest in my upcoming book, Holy Heretics.

Ideally this week people would have received their preorders. Unfortunately, though, the cloth for the hardcover edition was damaged in transit, and now shipping is delayed to begin on Monday, November 17th. To shorten the waiting time a bit, Scarlet Imprint and I have decided to offer you to open the book together in advance.... So on this page you will find the complete introduction to Holy Heretics - before the release and for free.

I also had the opportunity to record an episode for the wonderful Glitchbottle podcast, in which we dive headlong into the themes of this book: Magic and Mysticism, the double-edged sword of the Christian Tradition, Paracelsus, and, of course, the world and reality of the Olympic Spirits.

Holy Heretics begins with a longer quote from the 14th century Gulshan-i Raz; you can read it just after this paragraph. Following it, and in reference to its timeless thoughts, you will find the full Introduction.

Thanks for your patience and time.

LVX,

Frater Acher

[...] God is everywhere, visible to those who see by the light emanating from his beautiful face. He is ahead, and all men follow, holding his hand. Those friends of God who are behind, as well as those who walk ahead, have given news of arrival at their destinations. When they become self-aware like Adam, they may reveal news of the Knower and that which He knows.

One of them dove into the ocean of Oneness and said, 'I am Truth.' Another rode in a boat on the same ocean, and told of how far he was from the shore. One looks at the outside and talks of dry land, while gathering shells, and the other plunges into the ocean and gets the pearl. One starts talking about the bits and parts of things, how they appear and function, Another begins telling of the Eternal One and then of the creatures who live and die. One speaks of long curls of hair, the beauty spot, the curves of her eyebrows, the beloved man in dim candle light, passing a goblet of wine. The other speaks only of himself and his opinions. And the other loses himself in idol's of love, identifying himself with the monk's rope around his waist.

Each one speaks the language native to the level he has reached, and it is hard to understand what he says. You, the seeker of understanding, you must strive to learn the meaning of what they say.

(from the Gulshan-i Raz, by Sheikh Mahmoud Shabistari, 1317 CE)

Frater Acher, Holy Heretics, London: Scarlet Imprint, 2022

IntroductionThis book was written for all of us, as seekers of understanding. Seven hundred years ago one of the most famous Sufi mystics of the fourteenth century made the above address in words that remain timeless and essential to this day. Our experience of divinity is as individual as the knowledge derived from it. As human beings we are all living inside the pearl of a million rays, each of us reflecting back a certain nuance or shade of the divine light, and yet none witnessing it in its full uncreated potential.

In this world where we each possess a unique shard of truth, hasty judgement is the enemy of wisdom: one of us experiences divinity in the ocean, one of us in gathering shells, another in a lock of hair, each according to his or her sight. As human beings, however, we are not passive recipients of such experiences; we are co-creators of our encounters with the divine. Accordingly, and particularly as adepts of the magical art, we possess both the privilege and the requirement to continuously change our perspective, to enlarge the way we see this cruel and beautiful world and the manifold ways divinity manifests within it. It is best for those genuinely committed to a path of wisdom and personal evolution to harbour a healthy mistrust towards what we think we know and who we think we are.

This is the spirit in which this book was conceived, as the third and final volume of the Holy Daimon cycle. Its methodology offers a challenge and a contrast to the accepted sources for learning about Western magic. Thus, in the first part of this book we will be listening to some of the most antagonistic voices a Western magician can imagine: from the Desert Fathers to the Hesychasts and Symeon the New Theologian, from the Granum Sinapis to the Theologia Germanica, from the first centuries CE to the late Middle Ages, we will undertake a tour-de-force through the vast realm of Christian mysticism.

We will quickly come to see not only a view of the inner realm as we might not have expected it, but more importantly the heretical charge and tension within each of these voices. Because, ultimately, the source of so much hostility in our shared history does not reside in the difference of one man’s experience of the divine as opposed to another’s, but in the ever antagonistic forces between any unmediated experience of divinity and all forms of organised spiritual orthodoxy. The true mystic – like the true magician – irrespective of whether he or she emerges from an Egyptian, Jewish, Christian, Muslim, or any other paradigm, will always be perceived as a threat to organised spiritual institutions.

Western mystics and magicians, whatever the time and context in which they live, and regardless of how contradictory their practices might seem, all share one thing: the antisocial stench of the primal goês. All of our ancestors on this path have been lone workers, whether in the deserts, in their cells, or amongst their communities, walking their own version of the narrow path. And in doing so their very way of life posed a threat to any kind of codified, mediated and sanitised form of spirituality as represented by the major churches and institutional orders. Standing tall all by yourself and seeing angels eye to eye sucks the oxygen out of any kind of secondhand encounter with divinity. It is in this direct experience of the spirit that we stand united as holy heretics.

As part of the first half of this book we will discover the essential importance of what Christian mystics have come to call the heart space or heart flame. Following the ancient Greek understanding of emotions being located in one’s gut, for millennia the human heart was known not only as the throne of wisdom within man, but more importantly as the actual crack between the human and divine world, from which the light comes in. Each chapter, therefore, ends with straightforward instructions on how to approach your own heart space, how to navigate this complex inner realm, and how to ultimately attune it to the specific spirit(s) you intend to work with. Because the second half of the book builds upon these foundations, I would advise against skipping ahead and delving into the section titled MAGIC.

Contrary to common assumptions, the practice of advanced magic should not precede but instead follow periods of intense mystical training. I hope to illustrate many practical reasons for this in the first half of this book and specifically in chapters V and VI. In the final section I offer a restored version of an authentic ritual long considered lost. It relates to a magical act alluded to in the famous Arbatel and is best considered a form of baptism into the spirit and living presence of the cosmos. Paracelsus, the pseudonymous author of the rite in its earlier form, called it the act of restoring the Olympic Spirit within man.

Therefore I tell you cabalists and naturalists, or all magicians […] to learn the first three cabalistic principles: Ask, Seek, Knock on God the Lord, if you want to have a holy Spiritum (which is delivered to everyone from birth by God the Creator, to teach and guide people in all wisdom, art and true blissful life) with you and [if you want to be able to] converse with your Genius. Because no servant can be lent to you without your heart’s permission and without keeping the Evangelical commandments; according to which commandments, or Novo Olympo the faithful have more justice and freedom than those in the Old Testament with whom God did not speak directly but through the spirits: We, however, do not want to hear from the spirits alone, but we want to hear from God directly, for we have Him within us through our obedience to God. (Astronomia Olympi novi)

Before we attempt to ascend to the peak of this Novo Olympo, we have much work to do. Just as Icarus fell in his flight to the sun, so we can easily fall in our attempt to stand amongst the angels. For we face divinity neither as Jack nor Jill, names that turn to stone at the gate of the Moon, nor as sorores nor fratres, titles that melt away like wax on our ascent. Instead we face divinity as divine sparks ourselves, fragments of light facing the sun, bound from our origin to the absolute.

In this shape we are as one with all other human beings; one with those who walked before us and one with those who will come after us. In the eyes of divinity we are all one: one hand, one heart, one hive. And it is only in this shape, nameless except for the name of our species, that we shall come to stand among the angels.

But let us not be mistaken: we take the next breath, we take one step backwards, and once again we are wolves and pigs and hares. Conversely, if we hold our breath for too long or take one more step into the light, then we are dead. For such is the human condition: to partake in everything, from divinity to darkness, and never to be one thing alone. Thus it is meant to be; for it is the same hand of nature that gives the first breath to our children and that takes away their last; though one hopes with a lifetime of riches in between. We partake in it all, yet nonetheless we may choose to walk the narrow path and synthesise the Olympic Spirit from the open firmament within us.

This narrow path, of which we shall learn more, guides us safely among the traps and snares of hubris and self doubt, of egocentricity and guilt, of rigidity and inertia. Discovering our own path which leads from the tombs of our ancestors is the task of a lifetime. Whatever we create from it will be a beautiful hybrid, half of our own making, half the heritage of those who walked before us. The very nature of this path, however, has not changed throughout the millennia that our species has attempted to walk it: to breathe in both worlds at once, one foot in divinity, the other in the mundane world, one eye seeing eternity, the other our neighbour’s face; and so, in an act of Promethean courage and Clementian mildness, to stride out and live an honourable life.

I am very aware that searching for such a path among the very people who for centuries tried to usurp and control or deform and kill the Western magical tradition is a big ask. On such an expedition to find the narrow path we’ll soon be crawling through the bones, blood and ashes of our ancestors. And yet, at the same time we’ll also encounter beauty and genuine practice, true grace and deep spiritual power.

The attempt to see the world through the eyes of Christian mystics from many different centuries is an attempt to fan the flame they carried. And yet, I find my heart filled with dissonance and tension when walking in their shoes. For it seems to me they carried both light and shadow: one hand holding the flame, the other clinging to darkness.

Strangely, the further we walk back in time the more the tension seems to increase. It is hardly bearable by the time we arrive in the early centuries of Christianity. Perhaps this is because the actual, complex human beings have vanished behind the veil of time supervening between us, and all we hear now is the echo of the echo of their words. Or perhaps the difficulty lies in the fanatical extremism that guided the Egyptian Desert Fathers, itself a magical sword pulled from its scabbard. Just as easily as it cuts through the veils of the world, so it cuts through what makes us human.

Either way, excavating the powerful techniques practiced by our ancestors means immersing ourselves in their ways of thinking, living, and working, which always carries the risk of forgetting where we stand ourselves. Attempting to view, for example, Origen’s view of Jesus Christ not from the vantage point of how we would judge it today, but how Origen perceived it in his own time, requires the expertise of an anthropologist. How did Origen think about the world? What constituted coherence in his perspective? How did he forge the foundations of what would come to be one of the world’s most powerful spiritual paradigms? In order to truly encounter the Other, we must leave our own values and filters behind, with all the risk to one’s integrity that entails.

This leads us to the question of who is the intended audience of this book. To this, at least, I have a clear answer: it is for you. You and I, reader, will be embarking upon this expedition together, traveling from grave to grave, from country to country, century to century. Ours will be a lengthy journey indeed, far into foreign lands, with the risk of not returning as the people we once were. For seeing through the eyes of the Other, becoming a seeker of understanding, changes us – and changes everything.

Now, my presumption on this expedition will be that we both have certain essential traveling skills: to willingly manoeuvre our hearts into a silent, non-judgmental space; to realise the Other for what it is, rather than seeing our own projections in it (whether fears or desires); and in our pursuit of discovery, to put things that are dear to us on the scales without knowing where that will lead us. Most of all, however, I’ll trust your ability to embrace negative capability within your own mind; that is, to hold conflicting truths in your mind’s eye, and not to shut either of them out. To experience cognitive and spiritual dissonance in the pursuit of developing your capability to wrestle with a world that completely exceeds your ability to fully comprehend it. In short, I’ll trust we both show up as adepts with a desire to learn. Because becoming a seeker of understanding is a most dangerous undertaking. All magical books from Solomon to Faust teach as much.

Explore the BookAugust 20, 2022

Lucifer or Enoch?

Gerión, © Julian de la Mota, for more information see here.

What good…… is the knowledge of what holds the world together at its core if we continue to destroy it? More important than the knowledge of the innermost might be the knowledge of partaking. Before all abstract knowledge, we might want to seek a living relationship with the world right around us. The concept of human freedom can seem immensely overrated in the Western world, when we compare it to the concept of embeddedness.

Lucifer is the mythical being that represents for many the epiphany of the intrepid individualistic journey. A journey to empowerment to do the impossible and live unhindered and in full accordance with one's will.

Yet, none of us can be Lucifer and Enoch at once. Their routes of travel are diametrically opposed: The former travelling from divinity into individuality, and the latter the reversed route. Unconstrained freedom and unconditional service are the two poles between which we are all meant to follow the narrow path of our life.

Now the truth is, the narrow path of each of our lives is not delineated by a few heroic marker-moving decisions. Instead, it is lined on both sides by the fragile markers of our everyday behaviour. Whether we choose to travel a Luciferian or an Enochian path, or any of the myriad shades in between, it is the canvas of our mundane lives upon which the colours of our magic have to be applied.

This is true in our dealings with all living beings, plants, animals, humans, spirits and gods. Each one of us is truly nothing and can never be anything other than what we choose to become within our everyday lives.

Certainly, every biography encompasses peak experiences: formative moments of positive or traumatic nature. But the realisation of these experiences (i.e. literally, the act of turning them into realities) does not happen in the very moments when they occur, but by how we allow them to take root in our everyday lives. Realisation happens through the purposeful interweaving of ecstasy and normality, of emergency and habituality.

The birth of a child, the consummation of a marriage, the invocation of a spirit, the first crossing of a familiar over one’s home’s threshold - all these peak moments require continuation, they require transition into normality, in order to have any substantial meaning at all.

Therefore, we must think of the process of becoming Lucifer or Enoch not as a heroic epic, but as a life whose most extreme and most mundane situations have been brought into calm, everlasting integrity. Lucifer is Lucifer and Enoch is Enoch, whether they fill a cup of tea, light a cigarette, or forge their personal destiny in the bonds of their insurmountable choices.

Whatever territory your personal narrow path leads through, and by whatever beings and values it is guided, there are a few markers that help us on our way irrespective of the destination we are aiming for:

Presence, not fussiness. Composure, not indifference. Approachability, not naivety. Honesty, not cruelty. Reliability, not boundlessness. – And all of this with the goal of joy.

Every day we can ask ourselves: How do I make this day succeed – not in isolation, all by myself, or through a heroic act that neglects the reality of where I stand and how I feel today. But thrown into the vibrant bond of living and dying where I find myself. Partly dance, partly reeling. Partly adventure, partly madness. Partly choice, partly chaos. And in spite of this, and precisely because of this, I live with the goal of joy.

How do I walk, we can ask ourselves, towards the horizon that stretches between the fulfilment of duty and the fulfilment of self? Each of my days is a step forward on this narrow path. Duty on this horizon is not imposed on me by others, but the price I willingly pay for the decisions I made. Self-fulfilment on this horizon is not a narcissistic mirror, but a service that flows from being a useful tool in this world.

All the chaos of life can be as simple as this: Right now, I am the carpenter’s plane and the world is the wood. Right now, I am the smith’s iron and the world is the forge. Right now, I am a human and the world is the air in my lungs. Right now, I am death and the world is the night. Yet, always we walk side by side, world and I. Like two old friends on their way into a good life.

It is in this sense, of learning to coexist, of learning to value lived relationships over abstract knowledge, that I personally refuse to decide between Lucifer and Enoch. In fact, I hold both of their hands in mine right now; they walk side by side with me, one to my left, one to my right. And fair enough, I might not make it very far on this narrow trail of mine, due to the constant dispute and discussion between the three of us over every step forward. But boy, do I walk in good company.

And a note of gratitude to the marvellous Julian de la Mota,

for allowing me to showcase his stunning drawing of Dante’s demon Gerión,

who we encounter in the 8th circle of hell. – Well, that is in case

our narrow trail leads us towards such chthonic horizons…

June 26, 2022

72 Devils' Seals by a 17th-century Goës

Introduction

IntroductionHistorical research in the field of the occult is a strange thing. It requires an equal measure of openness to deviate from preconceived itineraries, as well as determination not to be seduced by the lure of ubiquitous anecdotes. All too quickly, a curious aside can take on a life of its own. Like a walk in the woods at night, we find ourselves surrounded by strange noises and a wide-open space that invites further and further exploration. The unknown wishes to be discovered. The ambiguous wishes to be clothed in form and story. And yet, every little anecdote can become another step into the labyrinth of spirits, and a step further away from arriving safely.

While researching the History of the Olympic Spirits, I came across the following curious historical footnote. I share it here because it seemed too valuable not to make it accessible to a wider English-speaking audience. However, as with so many texts of folk-magic, its real value lies not in the fancy spirit seals, but in the implicit information it conveys about the practice in question.

Luckily, its backstory has been preserved for us by the Austrian historian and archivist Hartmann Ammann (1856-1930) in his short essay The Sorceries of Ludwig Perkhofer von Klausen, including the use of Devils’ Seals (Hartmann Ammann; Die Zaubereien des Ludwig Perkhofer von Klausen mit Anwendung von Teufelssiegeln, in: Forschungen und Mitteilungen zur Geschichte Tirols und Vorarlbergs, 1917, p. 66–77).

Ammann included in his article a coarse photograph of the devils’ seals. We are extremely indebted to the Director of the Diocesan Archives of Brixen, Erika Kustatscher, for the new photos that she has made available and which are reproduced here.

Ludwig Perkhofer, a 17th-century GoêsOn May 31, 1681, the dean of the cathedral and auxiliary bishop of Brixen, Jesse Perkhofer, had died. Still at his deathbed, the bitter fight of his brother, Ludwig Perkhofer, for the rich estate of the bishop, which is said to have amounted to 35000 imperial florins, developed.

During this legal dispute, Ludwig confronted his opponents in such a polemic and accusatory manner that it was quickly suggested to imprison him. While he escaped an official verdict of incarceration, he was subjected to an interrogation in order to determine whether the statements and invectives in his writings, which sometimes bordered on blasphemy, had originated from his own hand, what he had actually wanted to achieve with them, and whether he was prepared to retract the complaints that had been made.

Additionally, an order was given to confiscate a certain chest from Ludwig and to inspect its content. As the surviving protocol in the Brixen archive detail, within it the officials found: Two old, written books on various “arts”, an incantation of the evil spirit, two other books with forbidden arts, an incantation for finding treasures and mines, an incantation of the chicory root, a number of written slips of paper, including one with circles and names of saints, a booklet on how to solve sorceries; furthermore, in the small chest were found: a mirror for an unknown purpose, and in a small bag hoopoe heads and several iron nails.

Despite these highly suspicious objects, and only after the intervention of Ludwig’s son with the bishop, his father was released from pre-trial detention, but with some strict conditions such as being sent to a small mountain village three walking hours from the city of Linz and needing to remain there, as well as to forgo all previously mentioned claims.

Although he accepted these conditions under oath, he continued to fight for the inheritance of his deceased brother. And so, we find our stubborn Ludwig in custody again already during the same year, 1682. This time, the protocol reveals some further glimpses into his magical practice:

Ludwig Perkhofer confesses that he had conjured his deceased brother (the suffragan bishop) to appear before the commission at the hearing about his estate and to testify in his (Ludwig’s) favour. Ludwig had even added: “And you God, when you are a just God, must let the appearance happen.”

He never bothered with certain arts and conjurations of devils, nor did he ever need their help. He himself painted and wrote the seals and invocations of the supreme devils with their characters, names and signs [...]. He received the manuscript for copying from N. Tassenpacher from Prague, copied the incantation only out of curiosity and for the science of how to fix the devils, but never made use of it. He did not have the characteres (devil seals) in a special depository, but in a sack with various writings and has had them for 8-10 years.

Ludwig Perkhofer also had 2 written books, in which different such forbidden arts were inscribed, he received them from the two daughters of the old doctor who died in Taufers, read them through, but never used them. He used the roots of the chicory and conjured it that, when something was stolen from him, he put such roots under the pillow and then the thief “dreamed” him, and once in Taufers a thief brought him back chains and belts. He performed the incantation with the words: “I adjure you root by the living God with those powers, so you have been gifted by God, that you communicate the same power to me.”

He did not use the booklet for resolving sorceries, and he did not exercise the mirror that leads to the mines, because he did not conjure it to this end.

He wanted to use the hoopoe heads only for the poison, together with the iron of old horseshoes that one finds on the road, with which one makes the mines invisible or cancels their invisibility.

He did this once on the Albl, called Jaghaus behind Rein [a side valley of Taufers near Brunecck]. In the evening it did not work, but when he tried again early in the morning before sunrise, he found the lost mine again in the following way:

That he put the nail in there [?], then took three steps behind him and said with each step: “With the nail I have bound you, with the nail I open you, God the Father, Son and Holy Spirit help me.” After finding the mine in this way, he also made it invisible again by going three steps behind him and saying at each one, “Nail, as long as you don’t get back into the hole from which I pulled you, no one shall find you in the name of God the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit.”

Ludwig Perkhofer does not know where he learned this art, but he believes to have read it in a book. Otherwise he knows nothing of these things, “except that he advised people to load such nails into their rifles and to shoot them into the clouds during thunderstorms, which was supposed to be good for sorcery.”

During this second trial, as expected, Ludwig Perkhofer did not get off so lightly. In 1683 he was ordered to make ecclesiastical apologies, sentenced to ten years in prison, and his entire magical inventory was to be burned in front of his own eyes... Clearly the latter step was never taken in full, as the double page with the spirit seals survives to this day in the Diocesan Archives of Brixen (Signatur HA 9891).

These files also reveal that Ludwig Perkhofer, who was already 72 years old at the time, did not bow to this second order, but continued to fight tenaciously for what he believed was either rightfully his or should be his with the help of the spirits he had enlisted. Perkhofer died, still involved in legal battles, before the end of 1685.

The 72 Devils’s SealsInterpretationIn the following, we provide modern images of these unique spirit seals, as well as a translation of Ammann’s attempt to reconcile their nature and construction.

As we will see, from the perspective of a modern practitioner, the value of this historical material is condensed in the following three points. We anticipate these here to facilitate access to the material that follows:

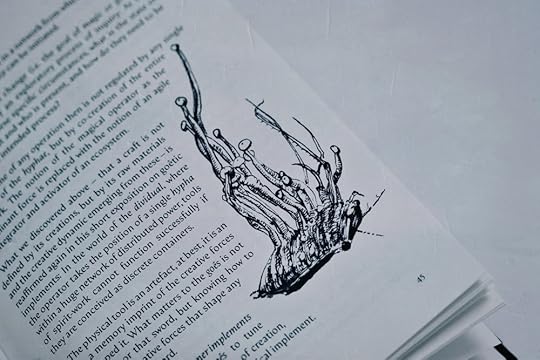

(1) These spirit seals make no claim to orthodoxy. On the contrary, they probably represent fascinating folk echoes of authentic goêtic practice. Rather than using rubber-stamped seals, the practitioner is encouraged to derive from each spirit a unique interpersonal seal intended only for their communion and contact.

(2) The instructions mention Lucifer as the ruling prince of the operation. However, the actual conjuration says that the spirits are summoned under the power of “him that maketh earthquakes”. Here we have another hint of authentic goêtic practice: Rather than orthodox spirit names, derived from man-made mythologies, the practitioner turns to a nameless spirit-force that is instead described by its specific ecological and chthonic power.

That spirit which holds the power to release earthquakes rules the realm of underworld. It is known foremost by its function in the ecology the practitioner participates in. And for this very reason, because of its elevated and unchallenged position of power in that of the underworld, this spirit is asked to bring the spirit in question into contact with the practitioner.

(3) Very few of the 72 listed spirit names are consistent with or reminiscent of classical Western spirit names such as Ariel, Beelzebub, Venus, or Ostara. Most of the others may be distant distortions of once-classic Western spirit names. Perkhofer himself states that he obtained the sigils from a man in Prague and copied them – which of course might have been a trick he devised during his interrogation to avoid revealing more about his personal practice.

From the perspective of a goêtic practitioner, we should instead consider another possibility: The spirit names on some of the seals might actually be the names of the spirits as revealed to Perkhofer or another local practitioner. This assumption is supported by the fact that some of them refer to actual places in Austria, e.g. Wörgl or Lassing. In addition, some of them are simply subtitled “rex”, meaning “a spirit is the king of”. This suggests that these spirits ruled over certain places such as a village, a mountain, or a gorge. In this case, the seemingly convoluted names below could indicate both actual locations in the practitioner’s topography, as well as personal names revealed to the goês.

Such considerations turn this historic anecdote into a curious case of possibly authentic goêtic practice – in the sense of a lived reality of chthonic sorcery – that took place in the Southern Alps of the 17th century: Spirits were conjured under the auspices of enlivened natural forces, their names were bound into the topographic locations where they resided, and any of the marks and echoes they left behind – may that be in the form of seals or names – were ephemeral and given as unique keys to the individual practitioner.

To invoke them once again today, a new bond must be placed around the minds of man and spirit. Each one unique, coloured by location, time, and order in the cosmos. To the chagrin of the modern scientific mind, nothing in magic repeats itself twice in exactly the same way. Never on this planet have two people kissed twice in exactly the same way. Likewise, no human and no spirit will ever make a bond that is not coloured by the time, topographical location and cosmic order by which they are connected.

Yours is yours and mine is mine. All we can do, is to send a call from here to there, in the hope that ancient ways are revived in modern times.

The Investigation of the Devils’ Seals (Ammann, 1917)The above-mentioned 72 devil seals or characters are drawn on the two inner sides of an ordinary sheet of writing paper and are distributed in a not quite even manner over 8 lines. They consist of two concentric circles each, drawn in black ink, but not always completely, between which usually the legend of the respective prince of hell is written. The scribe (Ludwig Perkhofer himself, see above) missed one with the legend Naso rex in the last line, which is why he crossed it with several strokes and entered it again next to it.

All seals are heraldic seals. Most of them consist of a number of straight lines, perpendicular to each other in various directions, forming tripods, but also cranes, and often ending in a pommel or an arrow-shaped point. Two seem to represent a perforated document with a seal; only a few contain images of people, animals or weapons, such as birds, a trident (?) a sword, etc.; two represent a caterpillar-like bulge, and in the penultimate row there is even the coat of arms of the city of Brixen, a lamb with a cross, which is probably supposed to represent a flag, of which only one is a flag.

The only visible part of the flag is a tassel hanging down. Since the legends are often written very unclearly, I cannot vouch for the fact that I have always read them correctly; I therefore see the ones that seem uncertain to me with question marks (?).

1. Pfere Pardus (?) 2. Fäbl, 3. Ariel, 4. Wolache, 5. Nerel (?) 6. Neizor, 7. Flamman, 8. Worgl Rex in arem, 9. Ostarat in mitermax, 10. Eminarna (?) 11. Suroforlt, 12. without legend, 13. Fabel, 14. Wenderer, 15. Walhelfe, 16. Faber antuar, 17. Faber andereng above and in the seal field, below “mer Har”, 18. Rua(?) bantes, in the seal field as no. 18, 19. Wüle, 20. Gorian in nox, 21. Siderobl, 22. Windl rex, 23. Alleton, 24. Felibiol rex, 25. Pelzepub rex in Romanis, 26. Suro, 27. Wündl rex, 28. Orneroth (?) 29. Bimel, 30. Pelzianus, 31. without legend, 32. Foriub, 33. Wolthann, 34. Merlieb, 35. Gans (?) fel, 36. Sareol, 37. Pareth, 38. Rosim, 39. Garlimbtun, 40. Sonta, 41. Lassing, 42. Sibtaier, 43. Furororumb (?), 44. Dopiol, 45. Farius rex, 46. Porgaria, 47. Wenus, 48. Wedaldes, 49 Liul, 50. Dostä, 51. Welman, 52. Pro- spenais, 53. Tridum, 54. Wenges gernn (?) 55. and 56. without legend, 57. Falor rex, 58. to 62. without legend, 63. Foroman rex, 64. to 69. without legend, 70. Naso rex XXX in X (seal crossed out), 70. a Naso rex + 1 + in XX, 71. XX Avanzetis? achesach? X in ruhtsech?, 72. Obmt Hecho.

The Application of the Devils’ Seals (Ammann, 1917, quoting the original archive documents from 1685)

These are the 72 seals of the supreme devils, hell kings, and princes. When they are required, take this constraint in your right hand and swear to them, and he will give you his seal. After that, make sure he cannot leave until he does your will and keep the seal.

Summon Lucifer to send the spirits, and if he will not come, take the same seal and write, as the seal is, on a plate that you smear with linseed oil, on it sulfur, [...] and asafoetida pitch, and burn it together with the hair of the goat, which you mix with the sulfur and pitch, until he does your will.

I adjure thee, spirit, by him that maketh earthquakes, that thou burn up this accursed spirit and devil, and make him to be accursed and martyred for ever.

Item speak over the fire and seal this incantation:

O thou [NN], thy name is put to shame, and thy name is incensed, and at the same time is tormented by the brimstone also by Lamoth's working, and reminded anew of thy admonition by the name of Lais Terminorum. You come into your dwelling first by the name Luasein, Laian, Ruriari, Lefeloria vyri, Rarefurth pero [...]. And before you will call the last name, whichever spirit it is, you will see it.

72 Devil's Seals from the trial records of Ludwig Perkhofer, 1683

© Diözesanarchivs der Hofburg Brixen, Signatur HA 9891, (Ammann, Anm. 1)

![[close up, top left] 72 Devil's Seals from the trial records of Ludwig Perkhofer, 1683](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1656247090i/33098096._SX540_.png)

[close up, top left] 72 Devil's Seals from the trial records of Ludwig Perkhofer, 1683

© Diözesanarchivs der Hofburg Brixen, Signatur HA 9891, (Ammann, Anm. 1)

![[close up, top right] 72 Devil's Seals from the trial records of Ludwig Perkhofer, 1683](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1656247090i/33098097._SX540_.png)

[close up, top right] 72 Devil's Seals from the trial records of Ludwig Perkhofer, 1683

© Diözesanarchivs der Hofburg Brixen, Signatur HA 9891, (Ammann, Anm. 1)

![[close up, bottom left] 72 Devil's Seals from the trial records of Ludwig Perkhofer, 1683](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1656247090i/33098098._SX540_.png)

[close up, bottom left] 72 Devil's Seals from the trial records of Ludwig Perkhofer, 1683

© Diözesanarchivs der Hofburg Brixen, Signatur HA 9891, (Ammann, Anm. 1)

![[close up, bottom right] 72 Devil's Seals from the trial records of Ludwig Perkhofer, 1683](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1656247090i/33098099._SX540_.png)

[close up, bottom right] 72 Devil's Seals from the trial records of Ludwig Perkhofer, 1683

© Diözesanarchivs der Hofburg Brixen, Signatur HA 9891, (Ammann, Anm. 1)

May 22, 2022

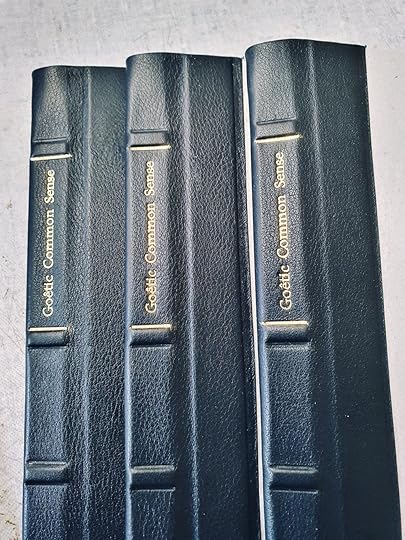

Book Update on my Paracelsian Trilogy

Let me take a moment to share a long overdue book update. Let me cover both the writing I have been doing over the last years and projects I aim to complete before the end of 2022. And if you don’t have time to read it all, I’ll make it really short. Here is the Paracelsian trilogy I am close to completing:

HOLY HERETICS - is a book of Promethean spirit and a primer on stealing the mago-mystical fire from the tombs of the Christian churches. It culminates in a restored Paracelsian initiation ritual with the Olympic Spirits. It is focussed to generate inner fire and magical contact.

INGENIUM - is a book about what it means to be truly human when standing surrounded by spirits. It shows a path into Radical Otherness and back again into the magi-mystical inner tools of magic as laid out by Paracelsus. It is focussed to generate wisdom and a living heart.

THE OLYMPIC SPIRITS BOOK - is a book about the history and the evolution of practice with the Olympic Spirits. It’s a deeply Paracelsian primer to walk the narrow path, and a restored grimoire of white magic. It is focussed to generate clear thinking and clean practice.

Contacted WritingBefore we get into the details, though, I should stress how these books have come to life. All the writing I have been doing over the last ten years happened in magical contact with the same group of spirits.

What does that mean? It means, I work with a small group of spirits and I invite them into my house, into my heart, and into my mind and hands. It is together with these spirits that I co-create all the written work that over the coming months will take the form of physical books.

The way this works in practice is simple: As long as I refresh my ritual contact to the respective spirits each week, they are ever present with me. They are with me, within me, like moons circling around the earth of my mind, giving me tides of images, ideas and words. If I stay still and open long enough, I can get their expressions down on paper quite cleanly.

The challenge in such way of contacted writing, as I have learned over the years, is both to allow the spirits to speak unconstrained, as well as to ensure that facts are not overlooked, that quotes and footnotes are tight and precise. Ultimately, to ensure the narrative adds up and shows a path that is worthwhile walking.

So, what fruits has this work borne over the past two and a half years?

HOLY HERETICSFollowing on the heels of completing Black Abbot White Magic in 2019, the spirits had a very precise idea of our next project: They told me to write an outline of how the mystical fire had been passed on, hidden and almost extinguished in Continental Europe over the last two-thousand years. Of course, I immediately replied: Thanks, but no thank you.

Not only would I be entirely unqualified to do such work, I thought, but also the limited time I have each day for writing presented the outlook of a decade long project… As often before, while still pondering the sheer magnitude of the project they suggested, I felt spirits rolling their non-existent eyes, and slap me over the back of the head. — By spring 2021 we had completed the book.

The process of writing Holy Heretics was the most pure experience of writing with magical contact I ever had the privilege of living through. Each morning I sat down, and each morning I was precisely instructed where to look for guidance, what to include and what to leave away. If you have ever studied under a highly experienced but very strict tutor, you know exactly what I am talking about.

Unfortunately, from an editing and layout perspective the book turned out rather complex. Which is why I am deeply grateful to Alkistis and Peter from Scarlet Imprint who have been wrestling with this mystical beast for many months. I will equally always be indebted to Jose Gabriel Alegria Sabogal for bringing to life this book with the magic of ink and paper, which he has perfected like no one else…

Thanks to additional Covid-related delays, pre-order for Holy Heretics is now scheduled to open in July 2022. Below is the high level content section – which also tells you that I did not live up to the spirit’s original instruction. Instead of covering an outline over a full stretch of two-thousand years, we follow the weave of the mystical light over 1500 years only.

What I am particularly surprised by is the last chapter on the Rite of the Olympic Spirit. For this chapter, in addition to the spirits, Josephine McCarthy shared brilliant guidance through several versions of this work. When I look at the end result – a never before published Paracelsian ritual fully restored – I know I’ll never write a more powerful (which also equals, dangerous) chapter on magical practice.

INGENIUM

INGENIUM The fact that INGENIUM would need to follow Holy Heretics was already clear to me, before I finished writing the latter. I put a statement out in 2021 that it’s likely going to be several years before this book would be done. Again, more than to anybody else, I was speaking to the spirits in my house, in my heart and my hands - and asked them to slow down and give me a break.

Where Holy Heretics unearthed the mystical fire and aimed to create contact to the Olympic Spirit(s), INGENIUM’s mission is to pierce through all byways and detours, and to reveal what happens to a human after they have created such contact.

INGENIUM is a book about human qualities. More specifically, as Paracelsus would have put it, it is a book about the human quality and how it is enlivened through magic.

When I enquired for the best way to approach this book, the spirits already had a clear idea again: To know what makes a human human, one best begins by gazing fearlessly into the mirror of Radical Otherness.

So after all, you’ll get less history and a lot more of my own and my spirits’ voice in this book. In a way, this book is an antithesis to Black Abbot White Magic, which focussed on bringing Trithemius’ voice and magic back to life. INGENIUM will be my most personal book yet.

And still, it presents a seamless continuation from Holy Heretics in so far, as it is a deeply Paracelsian book. At some point over the course of 2020, I guess, Paracelsus’ spirit simply took a seat in the circle of the daemons I was working with already. He is still here with me in this house now, or the echo of his presence is. He shows me where to open his books, where to find keys to deliberately cryptic passages, and how to listen to his words not with an academically trained mind, but an open, ancient, pagan heart.

If anybody truly conducts the Rite of the Olympic Spirit, they will find INGENIUM to be a compass helping them navigate the Olympic wilderness – the Olympi Terrae as Paracelsus would have said – they will find themselves thrown into.

INGENIUM, just like the deeper process of becoming human, is a story that only unfolds once we have mastered many years of practical magic. I did not set out to write an easy book or an accessible primer. I set out to write a genuinely Paracelsian book, coloured by my own blood and filled with both of our lives.

Below is the draft content section. The book is currently in the masterful hands of an artist I have admired for decades: Joseph Uccello. He has full creative control over its final form and body. We are currently on schedule to release it late in 2022 with my friends at TaDehent Books.

THE BOOK OF THE OLYMPIC SPIRITS

THE BOOK OF THE OLYMPIC SPIRITSRelentless, raging, wondrous, beautiful experience of writing with the spirits in my house.

I finished INGENIUM in early 2022, and soon after that I had the content section of my next book outlined. It was taking me into a completely different direction, into the lore of Russian fairy tales, into blood, bones and back into the stained lands of goeteia and the ancient Scythian past.

It was after I finished the material collection for this book, that the spirits told me to put a pause on the entire project - and to return to the Olympic Spirits once again. In no uncertain terms, they told me to finish the work I had started - and that I wasn’t done yet.

It took me a while to adjust, but now I can see it clearly: Where Holy Heretics is mediating magical contact, and INGENIUM is lightening up Paracelsus’s spirit from the heart – what required completion still is the actual written history as well as the evolution of practice of the Olympic Spirits.

The Book of the Olympic Spirits is a working title. As I am sharing this update, the project is two thirds done. Below is the content section as it stands. We will cover a lot of ground - from Paracelsus’ Archidoxis Magicae, to the Arbatel, to previously untranslated magical sections from Robert Fludd, to early 18th century grimoires and early 20th century folk-shamans still conjuring the Olympic Spirits…

Deliberately, I am writing this book as a stand-alone volume that people can read without having delved into any of my other work. Especially the second part will be the most grimoire-style book of my publications yet. And because I don’t like that necessarily, I am slowing down to infuse all the Paracelsian spirit required to unlock the deeper meaning of magic in its first part.

To my great delight, I had the honour of attracting the attention of a truly outstanding female artist to breath visual spirits into this book: the amazing Luciana Lupe Vasconcelos. We are currently exchanging thoughts about how to stay true to the hardcore Paracelsian spirit of the book, and at the same time find ways to give shape to all the ghosts, and magical contacts he deliberately hid in plain sight…

The Book of the Olympic Spirits is a work genuinely inspired by Paracelsus’ Musa sagax. It is currently on schedule for publication with TaDehent Books in early 2023.

I swear to you by everything that is holy to me: neither Arius, Photin, nor Mohammed, nor any other heretic were ever so heretical as this unholy magus.— Thomas Erastus (1524-1583) on Paracelsus

March 10, 2022

Understanding Belial

© JULIAN DE LA MOTA, Lucifer, 2020 - click to purchase print

IntroductionThis is a very personal post. It is also a post that has some rather disturbing content. Not in images, but in words. I am offering reflections on the difficult topic of attempting to understand an aggressor; much more remains to be said about standing with their victims of course. I have to apologise especially to all my Jewish friends for returning to this open wound. If I do so, it is in the spirit of never allowing myself or my people to forget. It is also in the spirit of making the poison of our past, an antivenom of the present.

We are experiencing a moment where a surprising number of people seem to take great pride in calling someone else their enemy. We are also experiencing a time when incredibly little effort seems to be made to understand the motives’s of one’s enemy. Today, the aphorism ‘Seeking to understand before seeking to be understood.’ is likely to be interpreted as a weakness or worse as a flaw of character by many.

I want to make a case against that. In fact, as magicians especially, we should know a thing or two about the understanding of otherness as well as the knowledge of evil.

In the kabbalistic system of the Etz Chaim and the ten Sephira, the qlippothic demon of the 11th pseudo-Sephira Da’ath (traditionally translated as Knowledge) is called Belial.

One translation of this ancient name is The Worthless Ones. Thus, Belial represents the demonic force that turns knowledge to nothing, that evaporates meaning – or applied more personally, that denies someone value. Everything Belial touches becomes worthless, it turns into nothing.

Knowledge (or Da’ath), born from genuine understanding, thus is the ultimate antivenom or shield against Belial. The more we understand, the more we generate value.

Becoming a seeker of understanding is a mission in creating value in this world. It’s a mission in making this world valuable. By understanding things we tear the shadow from them. Even things that were deemed worthless a moment ago, by turning them over carefully in our mind, we begin to see them in a new light: We might begin to see how they came to be, and what they once were intended to be. Nothing is ever worthless in this cosmos, but a lot of things can be harmful. The true art of becoming a seeker of understanding, therefore, is to create proximity without creating affinity or likeness. To step up close to Belial, without allowing the demon to touch us.

It is through this kabbalistic lens, of working with these demonic forces in real life, that I am sharing the following story. It is not an easy story for me to share. But such is the nature of understanding Belial.

LVX,

Frater Acher

May the serpent bite its tail.

I am an offspring of Nazis. I am also an offspring of nature, of crystal rocks, mountain rivers, of snake and ibex. But there is no beating around the bushes, I am an offspring of Nazis.

I am a German. When we delve into our not-so-distant past, pure evil is always around the corner: Old neighbours, who once helped us built figures from toothpicks and chestnuts, decades later over coffee and tea in a casual comment reveal traces of their past as concentration camp guards. Grandfathers had sailed through our youth as a passionate nature-lovers, as biologists and chemists, who had been able to avoid the terrors of war because their research had been deemed critical. And on an Easter brunch their daughters, now in their seventies themselves, drop an incidental remark that less Jews had been killed, had father not helped invent the chemical formula for Zyklon B.

Myriad of stories cloak themselves in the veil of the everyday. They are never uttered with horror, but dropped casually into the cracks of the most mundane situations: An aunt who tips off the police and, by a happy coincidence, can move into a large vacated flat next door a few days later. A half-brother of the parents, whose mother never appears in the family stories. Until a letter in the tangled estate of one’s dad reveals her to be Jewish and deliberately left behind during the sudden escape from Silesia.

You see, for us, fellow Germans these are not stories. They are voices in our blood. Well-hidden voices, murmuring voices, never sleeping, dangerous voices. And yet, voices we partake in. And that we are invited to bring to the foreground, so they can be understood.

For me personally, the constant presence of these sinister, gag-reflex-triggering voices has helped me a lot on my magical path. I had learned early on, that the deeper I dive into what I should consider my ‘self’ the more foreign, the more archaic and other the things I might find. I had learned early on that there is no safe space, no guilt-free retreat, no ablution that will ever wash away the voices swarming in my blood.

The presence of these voices also led me onto a journey of understanding. Specifically, of a journey into understanding what overtly seems entirely incomprehensible.

After the concentration camp visits of my childhood, and my personal visit to Auschwitz in my twenties, it was entirely clear to me: I had to understand how the mind of a Nazi looked from the inside. Running away from evil was a terrible strategy, when it was already in your blood. The only way was through. And to get through, I needed to do the unthinkable: I needed to grant my Nazi ancestors the right to be human as well. Perverted, of course, but human nevertheless. Only by looking at them as someone essentially like me, but who had made different experiences, I could hope to begin to understand the source, the make-up, and way of working of the evil they embodied.

Seek to understand before you seek to be understood, someone once recently has said to me. But how do you seek to understand what embodies pure evil to you?

Above the beautiful city of Berchtesgaden, surrounded by steep mountains, there are the ruins of what once was Hitler’s infamous Eagle’s Nest. High on top the mountain peak the Kehlsteinhaus still remains, with its golden elevator up through the mountain. It still breathes the Nazi charm of utter desolation of the soul. Below it, on the mountain slope, there once stood a large farmhouse, the Berghof at the Obersalzberg. History books about the Third Reich have much to say about it; this is where Hitler spent a lot of time during the war, befuddled by drug intoxication and painkillers, a few hours a day open only to visitors, and most of the time in bed dazed and exhausted. Clearly, to unleash utter evil into the world, one didn’t need a twelve-hour work day. Submissive subservience and anticipatory obedience did most of the job by themselves.[2]

Today, none of the remains of the Berghof can be seen. Instead the place is now taken by a small museum. If you walk up its stairs and step close to the glass-facade of its back wall, you’ll discover an audio-station. Several tapes are playing in endless loops, a bench invites to sitting and listening to them.

One day, I sat on one of these benches, headphones on, and heard the voice of Heinrich Himmler. He was giving a secret speech to hundreds of SS Leaders in 1943.[3] During this speech, Himmler arrives at the bottom of the human abyss. His words are so frightening, I have never heard anything come close to it. Essentially, in a few sentences, he opens a direct line of sight into how all these men and women had managed to lose their souls, their humanness.

A page from the authorised copy by Himmler himself of his speech from 4th of October 1943, source: wikipedia

Note: I must warn against the terrible things said in the following quote. To become a seeker of understanding, we must look evil in the face, not judge it from a distance. If you are not prepared to become physically sick or cry, or both, I suggest you skip the following quote of a key passage of this speech.

On 4th of October 1943 Heinrich Himmler said:

I also want to mention a very difficult chapter here before you in all candour. Among us, it should be expressed quite openly for once, and yet we will never talk about it in public. Just as little as we hesitated on June 30, 1934, to do our commanded duty and to put comrades who had missed the mark against the wall and shoot them, just as little have we ever spoken about it and will we ever speak about it. It was a matter of course, a matter of tactfulness, thank God, that we never talked about it among ourselves, never spoke about it. Everyone shuddered and yet everyone was clear that they would do it again the next time it was ordered and when it was necessary. I mean now the evacuation of Jews, the extermination of the Jewish people. It is one of those things that is easily said. “The Jewish people will be exterminated,” says every party comrade, “quite clearly, it's in our program, elimination of the Jews, extermination, let's do it.” And then they all arrive, the good 80 million Germans, and everyone has their decent Jew. It's clear, the others are pigs, but this one is a swell Jew. Of all who talk like this, none have witnessed, none have endured it. Most of you will know what it means when 100 corpses lie together, when 500 lie there or when 1000 lie there. To have endured this, and to have remained, apart from exceptions of human weaknesses - to have remained decent, that has made us tougher. This is a never written and never to be written glory of our history […]. On the whole […] we can say that we have accomplished this most difficult task with love for our people. And we have not taken any damage in our inner being, in our soul, in our character.

Well. I learned so much from listening to Heinrich Himmler. Despite the revulsion, the anger and sadness.

Not a week has gone by over the last twenty years since I first heard him speak these words, that I did not think of Himmler and what he said there.

I have taken his words deep into my blood. I have made them meet the voices of my grandparents and great-grandparents who whispers were already assembled there. And Himmler’s words - in a homeopathic way - have become an antivenom to all the voices of my past. For suddenly I could see the essence of the poison again that had befallen so many of my ancestors:

This poison is the idea that we can no longer trust our own nature. That man has to force life out and beyond its organic, meandering pathways. That standing on a heap of 500 corpses and not be traumatised, is what is means to be human. The idea that the quiet, gentle instincts of our soul are a weakness.

A verdict wisely spoken.Why am I telling this story here? A lot of shame, guilt and tears still well up, just directing my gaze to these places that will always be pitch-black, no matter how much light we shine on them.

I am telling this story, to invite for a culture of hard debate, as well as the seeking to understand. Not acceptance or approval, but deep human-to-human understanding.

This seems critical to stress: Understanding is nothing soft, nothing evasive or unmanly. Quite the opposite: Going into the enemy camp to become a seeker of understanding, to me at least, is a sign of great courage. It’s a sign of your conviction in your own resilience or antifragility. It’s also the beginning of healing. For a witch burnt on the stake, is a human not understood. As much as it might violate some people’s superficial ideas of entitlement and common sense, the same is true for modern images of enmity[4]: A homophobe, a white supremacist, a fascist burnt on the stake, is a human not understood. Once more: understanding, is not the same as tolerating.

I am aware of the problem: Becoming a seeker of understanding comes with the risk of being poised yourself. Of lessening your rage, of watering down your verdict, once you begin to see the outlines of a fellow human behind the mask you hate.

But maybe we can take this as an invitation to show the world our true strength: Let’s take the mask off our enemy, see their human face, their skin that speaks ‘brother or sister’ - and then still speak our verdict. We can make it as harsh as we think it deserves to be, but first we make the effort to understand. Otherwise we are no better than Belial.

A verdict wisely spoken is a verdict free of ego.

Hearing Himmler speak like this, made me wonder: Under which circumstances could I have become like him? He and I, we both started out in the same virgin, pure way as newborns. If I no longer consider myself immune to the experiences Himmler went through, to become the human monster he turned out to be, what kind of biography would have turned me alike?

My ego wants me to avoid these kinds of questions. It loves the illusion of superiority and defiance. But my heart tells me, deep inside, Himmler and I once were alike: We both were born as humans. And what really scares the shit out of me, keeps me awake at night, and infuses a Lovecraftian kind of horror under my skin, is to consider someone like Heinrich Himmler a fellow in species. A human like me.

If this was true, all my defences are suddenly down. I am standing here naked and vulnerable to the core. For I know Himmler did not plunge out of being-human suddenly. Rather, he slowly, measuredly walked out of it. One experience at a time. – In light of that, my own next step today, my next judgement tomorrow, could be the beginning of my own path out of humanness?

A verdict wisely spoken sees the enemy within ourselves. It has put in the enormous effort of dismantling the mask of the monster and of discovering the distorted fellow specimen, as bitter, as frightening as this realisation is. We are all vulnerable to evil. It’s only some of us who were led to actualise their evil. Understanding the unique reasons that led to this actualisation, is the foundation for acquiring truthful knowledge (Da’ath).

Again, understanding evil does not have to lessen the sharpness of our verdict over it. However, it ensures our verdict flows from a place of genuine knowledge. From a place of seeing Otherness as something inherently coherent, logic, possibly even ethicallyaccording to its own terms. For that is what true evil and true horror are made of: The realisation that seen from the inside they are not madness, but mostly clear logic, in the absence of a wise heart.

Calling someone mad, dumb, uneducated, primitive, etc. are all just excuses for not having gone deep enough into the enemy’s camp. As a basic rule, we all make sense according to our own terms. Even the most distorted and monstrous of us. Making the effort to understand their terms does not make us alike. But it holds the beginning of making us immune.

[1] For further details see my free online essay on the kabbalistic Qlippoth: https://theomagica.com/on-the-nature-of-the-qlippoth

[2] Peter Longerich; Der ungeschriebene Befehl. Hitler und der Weg zur „Endlösung“, München: Piper, 2001, ISBN 3-492-04295-3