Kate Ruston's Blog

July 1, 2016

Writers Block? Try Five Songs

I often find myself experiencing writers block, sometimes I feel like writing but become totally lost and get stuck for an idea. Today we are going to try a creative writing exercise called five songs. There are various things you can do with this, but for this exercise we will choose five of your favourite songs and their last lines. See mine below:

FNT

Last line; Even when you are not new.

Smooth sailing

Last line; Shut up.

Carry on my wayward son

Last line; Don't you cry no more, No more

The man in the box

Last line; Feed my eyes now you've sewn them shut

Heart go faster

Last line; I feel I could make it last forever

We will now do a multitude of things with this;

● Write a short paragraph with the last line of one song as a beginning.

● Use the last word all five songs in your opening sentence.

● Try to incorporate the themes or words into a narrative.

See mine below.

It was not new to him. Not that she knew at this point. No matter what, this was the last time. He'd sewn his own eyes shut to the truth of it all. She wrote that he was her always. They made love under the stars and kissed each others scars. Nothing was secret from him. Nothing was known by her. He had said to her "I could make it last forever." And she believed him at the time.

But as the years pulled at their relationship the stitches came undone and he began to see the lies he was living in, the guilt towards her became unbearable and his self destruction seemed the only way to end it. Little fights building, disagreements everyday and then he said "no more". It was the first thing they agreed on for six months of their domestic wistful failure. They gave freedom to each other in a kiss in the door way and never saw each other again. Their past began to shut up, slowly at first as the memories resisted and the memorabilia was distraught before it was destroyed. Little is left of what they were and how they felt for each other. First love. Never matched, nevertheless it's not always real.

Please feel free to post your paragraphs in the comments.

Please show your support by clicking like, commenting and following.© Kate Ruston and Happy Little Narwhal 2016. Unauthorized use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this site’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Kate Ruston or Happy Little Narwhal with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.

Like us on FacebookMy e-Books: From the Watchtower The Blind Kings Sons Harry Potter and the Gothic Genre

June 29, 2016

Into the Lake of Souls

I'm just beginning to question it all. To try to see sense where there is none, I opened my eyes again and now I am here, what ever here is. Physically, I feel lighter now. My thoughts make me sink. Under the water, I lay on the bottom for years, but rot doesn't touch my skin. I do not move. My eyes stay open and I see all I have done, all I have felt re-breaths inside me, bitter and stale. This goes on until i have picked apart ever second of my life countless time, breaking them down so small that they stop being anything whole. A memory of playing as a child, broken into unrelated segments. colour, sound, shapes, warmth, touch, I took apart every detail and hid them out of order, in the wrong places in my mind. I broke it all down to take away all of the pain. It was after this that I noticed that I seem to have lost my name, it's all out of order. Just letter with no form or meaning... "H". H is for... it's for... and I don't know why it's important to remember. I sit up, pushing layers of mud and silt from myself and begin to rise.

I'm just beginning to question it all. To try to see sense where there is none, I opened my eyes again and now I am here, what ever here is. Physically, I feel lighter now. My thoughts make me sink. Under the water, I lay on the bottom for years, but rot doesn't touch my skin. I do not move. My eyes stay open and I see all I have done, all I have felt re-breaths inside me, bitter and stale. This goes on until i have picked apart ever second of my life countless time, breaking them down so small that they stop being anything whole. A memory of playing as a child, broken into unrelated segments. colour, sound, shapes, warmth, touch, I took apart every detail and hid them out of order, in the wrong places in my mind. I broke it all down to take away all of the pain. It was after this that I noticed that I seem to have lost my name, it's all out of order. Just letter with no form or meaning... "H". H is for... it's for... and I don't know why it's important to remember. I sit up, pushing layers of mud and silt from myself and begin to rise.Before I was here, I think I was standing below him, Darren. One of the memories I could not fracture. He looked so disappointed in me. I have betrayed a true friend. One who had defended me. And they all never suspected that I would do that, make an alliance with the enemy. It was for the greater good. Countless would have died either side. The vampranese knew that it was the best way. We made a mistake with Gavner. It all was pushed too far too fast. Why is this all coming back to me, little bits over endless days? He is so young to have done this to me."AR" It is out of order, what I did to them was wrong. I know that now, other wise I wouldn't be here. This can't be a place good people go.

They move around me, we collide, they are cold and lifeless, we touch, their yellowing eyes flash with fury for a moment before continuing onwards, as do I. Is that what I look like now? They are thin, skeleton showing under weakened flesh. We are all just churning, swimming together in circles, never going anywhere but restless to stay still like the others thst lay below. The fluid we live in is thick and lilac in hue. I'm not sure if you can call this living. "KAT". I spell it with a K. Some times I'm blind again, memories are no trouble to me now as I have few left. Even the ones that remain are ditching, like they were a story told to me long ago about someone I can't remember being. Once I had many, they pained me, perhaps that is why I sank, under the weight of my life, only to serface when I could let it go. Sometimes I would see the mountain and recall my first journey there, then all the time I stayed within and all of the plotting I did. I am regret... I noticed my hands today. They are much fairer than before. And the fingers are unmarked."M" is another of the letters, I can remember the pen making this bird-like shape, my hands did that mark on the page. They were all in my name. My hands with the knife, marking a mark in Gavner. Then, repeatedly, the stakes. They came through my hands too, they punctured everywhere. So why am I together again? My nails are long and translucent now. My veins are indigo abd broad, pushing up my drawn skin. "U"... you did this to yourself you know... It never seems to be night here. always a half darkness. Indiscriminate time. "L"ife. Life is time going forward, the growth and decay. This place is past decay. Like we are pickled, stored in a purple lake for an unknown purpose. How long has it been? Sometimes, for days, I swim and do not think at all. I have no way of telling for how long I do this. But when I come back around I notice changes in the others, some become slimy or scaled, others are so thin now that they are little more that bloated skins. The sky is dark. Dark sky."DS" Close... but not right. I still cannot tell if it is day or night, but the sky is black I look up to the water surface and the black floats on top like a lid, from time to time it ripples, but mostly it is still. Some times I see an old man looking down from the other side of the black and i see that he is smiling. But it is not a happy smile. He tells me things inside of my head. He says that I will come fishing here one day, along with he who put me down here. They will pull me out and give me back my name, etched on the teeth of the traitor lord. And I will risk it all for the two of them to live, perhaps returning me into the lake. He speaks like destiny.

© Kate Ruston - A doodle I did when originally reading the books in 2010

© Kate Ruston - A doodle I did when originally reading the books in 2010Thank you for reading. The above work is based on the 10th book of The Saga of Darren Shan by author Darren Shan, my favorite series when I was a teen. I would highly recommend this series for any Vampire fan but advise that it is written for young adults.

Please show your support by clicking like, commenting and following.© Kate Ruston and Happy Little Narwhal 2016. Unauthorized use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this site’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Kate Ruston or Happy Little Narwhal with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.

Like us on FacebookMy e-Books: From the Watchtower The Blind Kings Sons

Harry Potter and the Gothic Genre

June 15, 2016

Unclear Glass

The glass is scratched from being washed

by a dish washer for years.

Tiny salt crystals deepening into the glass surface,

engraving their own unique salty existence

into random lines.

Looking through, the world is scratched.

Just deep enough to show.

She drinks her coke from the glass.

And the point of it all is unclear.

Thank you for reading. Please show your support by clicking like, commenting and following.© Kate Ruston and Happy Little Narwhal 2016. Unauthorized use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this site’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Kate Ruston or Happy Little Narwhal with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.

Like us on FacebookMy e-Books: From the Watchtower The Blind Kings Sons

Harry Potter and the Gothic Genre

June 9, 2016

One of the Days

I need to keep moving on. Stay still, get caught. There is not a lot of fight left in me now, not after all of this. I'm staying in someone's old apartment tonight. One of those small apartment blocks above shops, like the one I lived in when I was nineteen. Other peoples possessions still here after all this time, dusty but unmoved. Some canned fruit, not bad yet. I may save it, it will be my birthday soon. Not that I know for sure. I've pushed the sofa to the door and this is where I will sleep. The window prepped with rope. A loss of rope better than a loss of life. Or perhaps not? Check the pipes for water, only a small amount but better than none. Boil it. I've been looking at their photographs. A couple lived here about my age. They are slightly overweight and don't look like they love each other very much. I guess all relationships get like that. I wonder if they broke up or if they are still out there fighting together, longing for the days that they fought each other. If they are alive they will have to fight until they are dead. Or they have become one of them. I wish I could find them when this is all over. Though I don't think I will see that day, if it ever comes. We could have a drink and look back at the past few years and laugh about it. Laugh off all of those we loved and lost and those we were robbed of ever meeting, like the good old days of news papers, jokes and memes. This couple are two of my best friends, the third is a train.

I need to keep moving on. Stay still, get caught. There is not a lot of fight left in me now, not after all of this. I'm staying in someone's old apartment tonight. One of those small apartment blocks above shops, like the one I lived in when I was nineteen. Other peoples possessions still here after all this time, dusty but unmoved. Some canned fruit, not bad yet. I may save it, it will be my birthday soon. Not that I know for sure. I've pushed the sofa to the door and this is where I will sleep. The window prepped with rope. A loss of rope better than a loss of life. Or perhaps not? Check the pipes for water, only a small amount but better than none. Boil it. I've been looking at their photographs. A couple lived here about my age. They are slightly overweight and don't look like they love each other very much. I guess all relationships get like that. I wonder if they broke up or if they are still out there fighting together, longing for the days that they fought each other. If they are alive they will have to fight until they are dead. Or they have become one of them. I wish I could find them when this is all over. Though I don't think I will see that day, if it ever comes. We could have a drink and look back at the past few years and laugh about it. Laugh off all of those we loved and lost and those we were robbed of ever meeting, like the good old days of news papers, jokes and memes. This couple are two of my best friends, the third is a train.Thank you for reading. Please show your support by clicking like, commenting and following.© Kate Ruston and Happy Little Narwhal 2016. Unauthorized use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this site’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Kate Ruston or Happy Little Narwhal with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.

Like us on FacebookMy e-Books: From the Watchtower The Blind Kings Sons Harry Potter and the Gothic Genre

January 13, 2016

The Good Things about Living in a Bad Area

But lets try this new thing. Positive thinking. Instead of me writing every thing I hate about living in a bad area, let us look at the good points about living here.

'Ronald McDonald Lady'

'Ronald McDonald Lady'Need to get rid of something that you don't want or is too big to throw out. Write 'Free' on it and put it outside. Problem solved.Low rent. More money to save.Lots of Christmas lights, Halloween costumes and random little fairgrounds.Lots of parks.Lots of choice for takeaway. Unkempt gardens means amazing wildlife.Indoors furniture, outside!People watching from your front room. Pretty much your own personal soap.Knowing people like 'Tattoo Stan', a man called 'Snakes' or 'Big Pete'.Giving people you don't know names like 'Gin Bike Guy' and 'Ronald McDonald Lady'.Cheap alcohol easily assessable.Lots of churches and other buildings of worship if you want them.Plenty of schools and children for your children to go to school with.No regulated litter laws. For that bag in the wind situation.Scrap men, here to collected all your unwanted, metal goods.Second hand furniture shops, for the frugal, student or the broke among us.Pretty trains sounds (proximity to train line required).BBQ' and other bon-type-fires.Some form of Woods near by.Ability to go to the shops in PJ's and not stand out (never done this, but nice to know I can).Lots of dogs, for the canine lover.Lots of cats, for the feline lover.In winter, its practically a ghost town.Cool abandoned building to photograph.No way of playing music in summer, no problem. Just open your windows.Drama of fire trucks/ambulance/police.Really sweet old people (no sarcasm in this one).People moving in and out often, much more interesting neighbour.Having a massive dog isn't seen as bad thing.Having a fictional massive dog isn't a weird thing.You will appreciate money.Curby.

So, hey its not all bad! Even if some were a little sarcastic, I'm glad I've lived here because the world is a big and diverse place and not many people know the pros of these areas and they dismiss the people who live in bad areas as bad people, which isn't always true. And no matter how good or bad you think you have it, there will always be somewhere worse or better than you. So appreciate the one thing about living in any area. Your living.

Beautiful abandoned building

Beautiful abandoned buildingPlease note that the works above were intended as a work of satire and if anything in any way offended you, it is unintended and apologize for.

Thank you for reading. Please show your support by clicking like, commenting and following.© Kate Ruston and Happy Little Narwhal 2016. Unauthorized use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this site’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Kate Ruston or Happy Little Narwhal with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.

Like us on FacebookMy e-Books: From the Watchtower The Blind Kings Sons Harry Potter and the Gothic Genre

January 8, 2016

A Short Story; Lamenting Leaves

One Thursday morning, about eight months ago, the doorbell shuddered through the apartment and lifted me out of a stupor and I absently walked to the side door, hoping he was on the other side. Usually I’d still be in my pajamas but today I dressed to match my pop tart breakfast, in an equally cheery purple off the shoulder dress, my favorite brown knee high boots ...dark emerald socks. I wanted to look good for him. It had been so many years since we'd even been in the same country. I missed him. It would be good to see him after all this time, he'd be proud of me? I wedged the door open in trepidation and all my expectation and hopes pored through the gap like a sun-ray passing through the eye of a needle. “Good morning madam, may I ask you where you’ll think you’ll be in ten years time?” I stared at the man bleakly as the mirage of life split in two, like an overripe orange sliced keenly in two, revealing the bitterly raw flesh. He had not come. I closed the door. The man slipped the cancer awareness leaflet though the post slot and left muttering angrily about people’s considerations and how it wasn't his fault if I was having a bad day. But over all he left to go on with his life and what ever his job was and back to whomever he loved. I had that too, but it wasn't the same. I knew the answer to his question. The answer was I would be here. A few days passed and the door rang again. I was still in my pajamas, an old ‘Nirvana’ t-shirt and some bottoms that were a Christmas gift, covered in hundreds of little snowmen in red knitwear. I knew it wouldn't be him. He doesn't love me anymore. He’s with her. So I ignored it and nibbled on my toast and sipped my coffee. But it kept ringing, so reluctantly I stood and answered it only to see the same man as on Thursday. He asked me the same question, but this time waving a new leaflet, this time on mental health awareness, under my nose. I gave him my answer I decided from before. “Um, now you don’t sound too happy about that?” He said. “I don’t care. It doesn't matter anymore.” I replied. “Look, I don’t usually do this but you seem pretty down.” He wrote an address on the back of the leaflet with a crooked smile, looking up at my face after every word or so, his brown shaggy hair catching in his lashes as he did so. His mouth was almost circular and very feminine which was set on a rather stubble filled, angular jaw. He had no blemishes or freckles and had pale but rosy skin. He was very attractive. And he still is. “It starts at two pm today and on Mondays. There’ll be a lot of people there. I go myself…it helps.” I thanked him and he left, this time smiling to himself.

The bottle was adorned with little gems of water that caught the light and reflected it around the restaurant, looking like starstruck eyes. Watching me. Blue glass dulled the red inside. It was encased and safe; its taste was dormant. Until the waiter opened it . From the other side of the table, he saw my hand twitch as the waiter did so, and reached out to hold me. We got on so well at the meeting; I thought how glad I was I answered the door. I don’t care now if it wasn't who I had first hoped it was. I know now why my Dad didn't come and I’m fine with it, I think I knew it then, in some way. His rosy square hand caressed my fingertips. I remember thinking, is this what love is like? It felt so much better than anything else I've ever had. So much better than I could have ever wished for, or could have dreamed of. I thought about the chances of him coming to my flat two times in a row and just knew it was because it was meant to be. And our first date was going so well! “Do you like the place?” He asked me. I said I did, very much. He gave my hand a squeeze. “And the chicken? How is it?” I told him it was the best I’d ever had and stared into his eyes. This was when I first noticed their colour. They were a cloudy grey. I wondered if they used to be blue when he was a baby. Some people’s eye colour changes, you see, and I wondered if his had changed. It reminded me of when we painted our house in summer. We painted it a light green. I didn’t like it much but Dad and me worked on it together along with Uncle John. My Mum made us icy lemonade and a quiche that had bacon and peas in it and we ate it all together on a tablecloth, very much like the one on the table in the restaurant. I remember that I kept going to the next-door neighbors for over a year, because I kept forgetting we had changed the colour to the nasty off green. Next door looked more like my house than mine did. They never asked me what I thought.“What are you thinking about? I love it when your eyes look like that; I never know where you’ve gone.” I shrugged. I didn't want to tell him. I don’t know why but I didn't so I just fed him some of my chicken and asparagus. I really like asparagus. It looks like little darts. At the end of the evening we sauntered back to my flat, along the black tarmac road river and under the inky blue sky that glittered constantly like when you strike flint together. He kissed me at the door. I was to see him tomorrow as well. I couldn't have been any more excited. It was hot outside. The water whirled around the vase like a storm would if you ever tried to encase her, the bubbles tearing into the surface and frothing. I didn't say a thing. I never say a thing. I drowned the stems after sheering them into a point and placed the bouquet in pride of place on my grandmothers mahogany table, the lace table cloth he bought me for my birthday last year looked as brilliant as it had in the shop, only there was a little tear from when I took off the label. He screamed at me about how he was only ever being nice, I found myself only able to look at the flowers. He had bought me: aconitum, buttercups, daffodils and monkhood. No roses any more. The harder I stared, the more they sucked in all the colours in the entire room. Soon the purples and yellows grew too vivid, like poison, and turned into hemlock and grew briers. “Are you listening to me?” His hands were at my elbows and they shook me slightly. “Where is your head at lately? Are you unhappy with me, Jessie? Look, I’m sorry I shouted at you. Work was hard today, stressful. I know I say that a lot now and that’s why the flowers. You can trust me, sweetie. You know you can.” And then he leaned in to kiss my head cheeks and mouth. The mood of the room shifted and the flowers gave the colours they had stolen back. The light seemed less hot and we shifted on the spot in a sort of dance. I was so happy in that moment. Nothing else mattered. We whispered how much we loved each other.

This was the night I thought that I had fell pregnant. He wanted to call her Flower after what had caused her conception. I said I’d rather call her Brier. It sounds like that fairy tale that my Dad used to tell me about a princess locked up in the tower and rescued by a handsome prince, I felt like I’d been rescued that day I answered the door. And I thought how pretty the name was, and I wished it were mine. I lay on my back and stared through the windowpane to see how the leaves had turned copper and grown gaunt. The doctor rubbed the gel on my stomach and told me that the suspicions were correct, I had miscarried.

Weeks after, we walked past the bakery on the way home and I looked bitterly into the window. Bun in the oven. I hated that cliché, but I longed to say it and it is true. He didn't know that it was the bakery that made me cry. He thought I was just sad at him. He told me we’d try again if I wanted; she’d been an accident anyway. I looked out through the black webs my lashes had formed, as my stomach told a well-rounded lie, and told him I wasn't upset at him. I was just upset. The streets were ghostly quiet as everyone was working. We had a visitor when we got home, but I simply told her to go away, I would not be attending, I simply couldn't bare my Dad’s funeral right now. I literally couldn't bare anything. She said I was heartless. I thought of the little heart that was no longer beating. She thought I was crying for him. I am always crying for her. We put flowers on her grave yesterday, together. The same kind we had on my Grandmothers table. It wasn’t long until frost clung to the delicate petals. He wrapped his arm around me and told me we’d be ok. He’d got that idea in his head. I had an idea too. I placed my head on his chest and hid from the snow that sheeted around us. The letters of ‘Briar Flower Brown’ were now twisted and engraved into my eyelids, the beads of ice still nestled in the indents and the soil still freshly stirred. Turning away did not hide that she had lived. The trees were still as empty as me, with their branches held in a lament for the loss of their leaves. Here I am now, stood in the bathroom. He’s lying in bed waiting for me. I've tried to be ok. But that idea seemed the best solution. I think I did right. I know I did right. He was fine; he liked it, as it had been so long. I’m moving back into the bedroom and can see him roughly, his eyes still closed. I sit down next to him and tell him I love him, him and Briar. The rosiness has gone. His brown hair still curls in towards his eyelids and he holds his gentle mouth slightly parted, in a crooked smile. But he doesn't reply. I pull back the sticky scarlet linen and stare into his perfectly pallid face... the line on his neck is sharp to my eyes, even in the dawn’s soft lazy lighting. As are the holes in his chest, but I was careful to miss his heart. His heart is important, it wouldn't be right for me to ruin it. He gave it to me to keep safe and he kept mine safe, so it wouldn't be right to hurt it now. It’s getting lighter in this room as his skin is getting paler. My pen is running out and so I’ll finish. This is my note, my solace. I don’t care. It doesn't matter anymore…

This is a short story I wrote my first year in college,Thank you for reading. Please show your support by clicking like, commenting and following.© Kate Ruston and Happy Little Narwhal 2016. Unauthorized use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this site’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Kate Ruston or Happy Little Narwhal with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.

Like us on FacebookMy e-Books: From the Watchtower The Blind Kings Sons Harry Potter and the Gothic Genre

December 12, 2015

Daphne Du Maurier's Rebecca; desire and identification.

In Du Maurier's (2003) Rebecca, identification and desire are key, entwined ideas. To explore them I will focus on the narrator and Maxim's desires and how they change their identities, the performance of desire and identity in costume and gender including theory of Butler's Gender Troubles (1990), the narrator's desire for Rebecca, the 'ghost' of Rebecca in relation to queer theory and Castle's The Apparitional Lesbian (1993) and well as Mrs Danvers and her involvement with the narrator and Rebecca. I will also look at the genre's used in the novel.

In Rebecca, the desire between man and wife isn't shown in a conventional romantic way as they seem to not have a usual adult and loving relationship since they only ever passionately kiss after Maxim's confession to murdering his late wife, which is strange enough alone. If this isn't odd enough, the reader finds that the two have a Father and daughter relationship through most of the novel, it being subverted in the opening (at the beginning of the novel where the narrator holds a Motherly role caring for Maxim who has become shell-like after the burning of Manderley). Due to this novel being marketed at the time, and still today, as part of the Romantic Fiction, this relationship is most peculiar as heterosexual desire is a leading element within this genre, however it is arguable that this text may be attempting, like many modern text, to be intentionally questioning the conventions of this genre to the means of confronting same sex female desire and the repressions it can have of female sense of identity, something I will discuss later in this essay. Still, Du Maurier does employ some aspects of the Romantic genre rather effectively in this novel such as; the plot being centred around a heterosexual relationship and marriage, use of exotic locations or occasions (e.g. the ball and Monte Carlo) and intense emotions within the romantic relationship between people of high social class. However, other techniques that she uses such as marriage used as a devise of desire to encourage the plot and help the heroine discover her identity (such as in conventional Romantic Fictions) yet she chooses to alter it by to not having 'happily ever after' in the conclusion, as the two seem to be in exile from everything they love and be in a state of punishment, perhaps a result of them both killing Rebecca (physically/her memory). She also chooses for the romantic hero in Maxim becoming aggressive, fatherly and passive, a combination not likely to have many followers of the genre swoon. However to start she follows Romantic conventions, in the quotation below we can see her using intertextual references to other Romantic texts such as Bronte's Jane Eyre (1847) and other Romanticised heroes like Conan Doyles' Sherlock-Holms (1904) to form the description of a man walking a fifteenth-century city, to create 'Man-about-Town' imagery and the descriptions of his items of clothing that suggest richness and high class, much to the same effect as Atwood's character of the Polish Count does in Lady Oracle, (1976) and Walter in Sarah 'Waters' (1998) Tipping the Velvet.

He belonged to a walled city of the fifteenth century, a city of narrow, cobbled streets, and thin spires…His face was arresting, sensitive, medieval in some strange inexplicable way, and I was reminded of a portrait seen in a gallery…Could one but rob him of his English tweeds, and put him in black, with lace at his throat and wrists, he would stare down at us in our new world …from a long-distant past… men walked cloaked at night, and stood in the shadow of old doorways. (Du Maurier, 2003, pp.15)

Also, the slow pace in this quotation created by the long sentence structure seems to frame Maxim in the readers first encounter of him as a man who is worth of a woman to stop, observe and romanticise about. However Maxim could also been seen in an entirely different light in relation to the Gothic genre, for in the quotation we see the first glance at the problems in their relationship, the paternal and aggressive masculinity which is a prominent side to Maxim in the novel. Du Maurier uses the words 'dark', 'medieval' and the phrase ' he would stare down at us' (Du Maurier, 2003, pp.15) and create the image of an aristocratic tyrant, observing the narrator with disdain to question whether he is the romantic hero or gothic villain. Maxims character is questioned further by the reader with his aggressive outbursts towards the childlike innocent narrator and the reader begin to feel a perversion in the romantic attraction between the pair.

'Listen my sweet. When you were a little girl, were you every forbidden to read certain books, and did your father put those books under lock and key?’‘Yes,’ I said. ‘Well, then. A husband is not so different from a father after all. There is a certain type of knowledge I prefer you not to have. It’s better kept under lock and key. So that’s that. And now eat up your peaches, and don’t ask me any more questions, or I shall put you in the corner.’ ‘I wish you would not treat me as if I was six,’ I said. ‘How do you want to be treated?’ ‘Like other men treat their wives.’ ‘Knock you about, you mean?’ ‘Don’t be absurd… You’re playing with me all the time, just as if I was a silly little girl.’ (Du Maurier, 2003, pp. 226-7)

Indeed, the relationship between Maxim and the narrator seems to be prompted by a desire for innocence, which is rather reminiscent of Stokers Dracula (1897) in which Dracula feeds from the innocence in order to corrupt them sexually, however by Maxim taking a role closer to the father than the lover, his desire for innocence seem to be less destructive and more protective of sexuality and the identity of the narrator and fearful of what others, perhaps others like Rebecca, could do to his new angelic wife. Horner and Zlosnik write that 'Rebecca is associated throughout the novel with several characteristics that traditionally denote the vampire: facial pallor, plentiful hair and voracious sexual appetite.' (pp.111) and notice that she was killed more than once 'she was shot; she had cancer; she drowned' (pp.111). This idea of Rebecca being the enemy and who Maxim is protecting her new wife from is reminiscing on Gothic heroes' like Van-Helsing of Dracula. Comparisons are drawn further after the discovery that Maxim murdered Rebecca as she is revealed as the threat that intends to corrupt his two loves, Manderley and now new wife due to her growing identification to Rebecca and her desires . Also by Du Maurier using this form of relationship for the 'normal' desire bond in the novel, we could see how Mrs Danvers raising Rebecca, "She ought to have been a boy, I often told her that. I had care of her as a child" ( Du Maurier, 2003, Rebecca, pp. 272), Du Maurier maybe drawing on the similarities between the two relationships to suggestion the sexual nature between the two women.

Prior to meeting Maxim, the narrator is a young woman struggling to find her identity and understand her desires. Throughout this novel, Du Maurier uses performance and costume similar to Sarah Waters (1998) Tipping the Velvet to explore this. Butler argues that gender exists as a form of social performance. She argues that woman isn't a fixed identity and that gender;

'intersects with racial, class, ethnic, sexual, and regional modalities of discursively constituted identities. As a result, it becomes impossible to separate out "gender" from political and cultural intersections in which it is invariably produced and maintained.' (Butler, 1990, pp.6).

She goes on to write; 'in this sense, gender is not a noun, but neither is it a set of free floating attributes, for we have seen that the substantive effect of gender is performatively produced and compelled by the regulatory practice of gender coherence.' (1990, pp.33) which questions how much of gender identity is performance.

'Put a ribbon in your hair and be Alice-in-Wonderland' (Du Maurier, 2003, p 219)In the quotation we see Maxim attempt for the narrator to assume the innocent to please him for fear of her dressing as a 'femme-fatal' , associated with Rebecca. His suggestion of childlike 'Alice' from Carroll's children's books (1865, 1871) is an example of intertextuality, used in the Romantic genre, such as in Atwood's Lady Oracle, (1976), Sarah Waters (1998) Tipping the Velvet, Morrison's Sula (1973) and Winterson's Oranges are not the Only Fruit (1985). Both of Maxim's wives dress to replicate Caroline de Winter, , and all of her social desirability in attempt to achieve different reactions in Maxim. Horner and Zlosnik (1998) writes of the narrators 'overwhelming desire is to please and surprise maxim by 'dressing up'' (pp118) by becoming as something virginal and pure, but as Rebecca also dressed up this way they go on to argue that she used it to aid her identity shield and perhaps disguise her bisexuality and construct 'heterosexualized femininity' to anger Maxim. In the line "And my curls were her curls, they stood out from my face as hers did in the picture" (Du Maurier, 2003, p238) the narrator uses the costume become the identity of Caroline, rather than mimic. As Rebecca dressed this way in the past she is also, invertible, becoming Rebecca. This scene is like the narrators dreams of transforming into Rebecca, in which Du Maurier explores the narrators hopes of pleasing her husband by presenting herself as stronger and closer to Rebecca, who, at this point, she believes Maxim loved dearly.

Du Maurier referred to Rebecca as 'a study of Jealousy', jealousy the result of unobtainable desires. This is shown most prominently in a passage on pages 261-262 where the narrators lists her fears about Rebecca and the reminders of her she has encountered, this creates a tone of hysteria in the narrators voice which shows how greatly she has identified herself to Rebecca. Yet, one must question the use of Rebecca being dead throughout the novel but the fact she has a presence which creates the illusion of her being alive. In the Haunted Heiress, Auerbach writes ‘she [Du Maurier] had a passionate self within herself: the boy in the box, that independent entity who fell in love with women while preserving the wife and mother from the tarnish of lesbianism’ (pp.74). In this Auerbach argues that Du Maurier had repressed lesbian feelings and as the novel suggests, Rebecca may have been modelled upon Maurier's own identity and desire as Rebecca is 'boxed' in death, however, her acted upon her desires in life and became an example for Du Maurier's fear of displaying the true lesbian ultimately destroying the individual. We can see evidence in the text that Rebecca too was a 'boy-in-the-box' but she expresses her 'boxed' desires by choosing the masculine-female fashion of short hair and taking part in boisterous activities such as sailing and horse riding.

‘Everyone was angry with her when she cut her hair…of course short hair was much easier for riding and sailing’ (Du Maurier, 2006, p. 190)

Du Maurier uses Gothic Genre conventions to create the ghost-like character of Rebecca by imitating a technique of 'haunting' used in other Gothic text, such as Jane Eye, which often leaves the narrator becoming strongly associating and psychologically linked with the identity of the ghostly 'Other'. The 'Other', Rebecca, grows in the mind of the narrator and, with much help from Mrs Danvers, attacks her identity. Horner and Zlonik write 'The narrators identity is haunted by an Other' (1998, pp. 99) and in this text this is shown in many ways, including when the narrator dreams her handwriting and appearance become that of Rebecca's.

I got up and went to the looking-glass. A face stared back at me that was not my own. … The face in the glass stared back at me and laughed. And I saw then that she was sitting on a chair before the dressing-table in her bedroom… Maxim was brushing her hair. He held her hair … and as he brushed it he wound it slowly into a thick rope. It twisted like a snake, and he took hold of it and … put it round his neck. (Du Maurier, 2003, Rebecca, pp. 426)

In this quotation the use of the narrator slowly becoming Rebecca and the application of snakes, which biblically links to 'Eve' (female curiosity, Original Sin and the temptation of men) in the readers mind, Du Maurier is showing the power of Rebecca and expressing that she is wanting to link into the narrators identity. In The Apparitional Lesbian, Castle argues that in fiction the Lesbian is 'ghosted' as is her desire and she is drained of “any sensual or moral authority” ( Castle, 1993, pp.32) Castle refers to this process as “derealization” (Castle, 1993, pp.6) meaning an attempt that the Lesbian is now disappeared and no-existent and a ghost like entity is formed to take her place, a form that is easier to be completely removed.

Why is it so difficult to see the lesbian—even when she is there, quite plainly, in front of us? In part because she has been "ghosted" or made to seem invisible—by culture itself.... Once the lesbian has been defined as ghostly—the better to drain her of any sensual or moral authority—she can then be exorcised. (Castle, 1993, pp.32)

With this in mind, we can further see how Du Maurier may have felt her to be too risqué of a character to explore her time, as I have written before, thus she is dead. However, Rebecca, although ghosted, is most overtly desired throughout the novel (by Maxim ,Jack Favell, Mrs. Danvers, the narrator and in their social circles). By doing this Du Maurier is attempting to 'un-ghost' her and expose her sexuality , be it Lesbian or bisexual. In the quotation below, Maxim indicates to a tabooed side of her personality that he seems reluctant or ashamed to provide detail to.

You thought I loved Rebecca?... I hated her I tell you…She was vicious, damnable, rotten … We never loved each other, never had one moment of happiness together. Rebecca was incapable of love, of tenderness, of decency. She was not even normal.’ (Du Maurier, 2004, p. 304.)

In this we see how Maxim, who perhaps represents society hence why Du Maurier deemed it necessary to 'ghost' this desire, finds her to be abnormal and associates her and her sexuality with evil and something for women to be shielded from, hence his paternal attitudes altering his desires. Whether this 'normal' is due to her being incapable of love etc. or if it is due to her sexual preferences we can only speculate, although Mrs Danvers line of ' She despised all men' (pp.382) the reader is readied to question it outright.

In this novel Du Maurier engages with the two issues of desire and identification to explore female taboos of sexuality, the performance of gender and the fear of the lesbian. Her novel is a complex argument between how desire shapes ones identity. I believe that this text is moreover a Gothic Novel, with the concern regarding female desire and a fear to express selfhood relating to ones own identity rather than the performance assigned by gender of woman.

Thank you for reading. Please show your support by clicking like, commenting and following.© Kate Ruston and Happy Little Narwhal 2016. Unauthorized use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this site’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Kate Ruston or Happy Little Narwhal with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.

Like us on FacebookMy e-Books: From the Watchtower The Blind Kings Sons Harry Potter and the Gothic Genre

October 16, 2015

NEW BOOK! From The Watchtower

You are driving to work, walking to the shop, sat at home or perhaps just sitting down. For a moment you are lost in your thoughts. When you are back to your self you begin reading these words, finding this story and become lost in the words of an unnamed man...

You are driving to work, walking to the shop, sat at home or perhaps just sitting down. For a moment you are lost in your thoughts. When you are back to your self you begin reading these words, finding this story and become lost in the words of an unnamed man... From the Watchtower is a letter to you, a glimpse into a place that you can not see. An example of a wish that shouldn't become a reality. A favor that only you can fulfill.

click the title below

FROM THE WATCHTOWER

It would mean a lot to me to have some of my readers take a look and leave some reviews, good or bad.

Thank you awesome guys who read and support my writing.

Thank you for reading. Please show your support by clicking like, commenting and following.© Kate Ruston and Happy Little Narwhal 2016. Unauthorized use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this site’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Kate Ruston or Happy Little Narwhal with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.

Like us on FacebookMy e-Books: From the Watchtower The Blind Kings Sons Harry Potter and the Gothic Genre

February 26, 2015

Novel Studies, Kristeva; Dialogism and Carnival

In this essay I will be discussing the two terms carnival (the spectacle of the colloquial language) and dialogism (two or more speakers in play in language) in response to the form of the novel and to Kristeva’s essay entitled Word, Dialogue and Novel (1986) and, due to the strong influences of Bakhtin in this essay, The Dialogic Imagination (1975), specifically the chapter Discourse in the Novel.Prior to the work of Bakhtin, the novel was viewed much differently to what customary today, as it was usually analysed with a structuralist reading. These theorists favoured to apply poetic theory to the novel, and used a scientific vernacular in attempt to explore and explain this form. Structuralists believe the novel to be monophonic, defined as there being one voice only acting within the text opposed to dialogic in which there are many, and they used symbols, scientific language (such as the term ‘centrifugal forces’- a force that acts to pull away from the centre or norm) and equations to better explain their views, as well as tending to ignore decentralised forces in life and language when examining the novel. The Dialogic Imagination is a compilation of Bakhtin’s previous essays including Epic and Novel (1941), From the Prehistory of Novelistic Discourse (1940), Forms of Time and of the Chronotope in the Novel (1938), and Discourse in the Novel (1935) and was first published together in 1975, due to the increases in the popularity of the poststructuralist ideas within his essays. Indeed, pre 1960-70s, structuralism was the accepted method of considering the novel and as Bakhtin’s ideas developed in the 1940s, this Russian theorist’s idea failed to reach the west due to west and east hostilities. Kristeva, however, presented and adapted his ideas to bring them to the west, she wrote of many of Bakhtins idea’s with her own insight in her essays, with the effect of a poststructuralist approach to language and the novel. However, like Bakhtin, Kristeva struggled to cut off from the methods in which structuralists present their ideas in the same ways I have stated previously (the use of symbols, scientific language and equations) thus creating an essay which contains a contradicting duality, also as I will discuss later, she failed to apply her theory to all novels, so briefly allotted the noncompliant text into another category of literature, the epic, to the effect of lessening her theory’s integrity.

In both the essays; Word, Dialogue and Novel (Kristeva, 1986) and to The Dialogic Imagination (Bakhtin, 1975), the argument that the novel is dialogic (a multitude of voices) is a significant one.Bakhtin argues that language, therefore the novel, is a representation of life, and life itself is dialogic and full of disrupting forces from many events and individuals pulling the language away from the simplistic view of structuralist understanding (centrifugal forces). He writes;

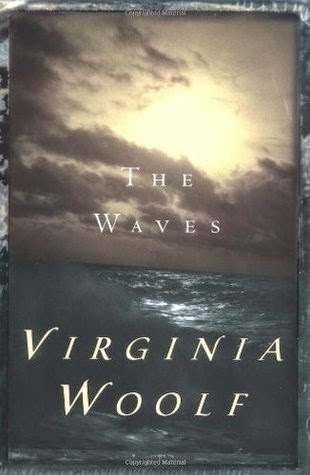

A common unitary language is a system of linguistic norms. But these norms do not constitute an abstract imperative, they are rather the generative forces of linguistic life, forces struggle to overcome the heteroglossia of language, forces that unite and centralise verbal ideological thought, creating within a heteroglot national language the firm, stable linguistic nucleus of an officially recognised literary language. (Bakhtin, 1975, p271)Bakhtin is arguing here that the official linguistically language is monologic and ideological. As it is often dictated by the ruling upper classes, it neglects all of the irregularities of language found in the national language. The national languages are obviously dialogic, as they are affected by; dialect and colloquial words (e.g. the novel Adam Bede, 1859), a modern example could be a the way that language had adapted in response to media and technology with the creation of new words and their abbreviations as well as the evolution of text/internet speech and their abbreviations. Bakhtin believes that the national language in the novel should be celebrated rather than rejected and restrained by the official language, as he believes that the influences behind the writing in the novel should be evident within the language used. Kristeva supports and builds upon this point in her essay and argues that diologism “appears on every level of the denotative word” (p.44). She explains this by proposing three dimensions of textual space for dialogue, she writes that; “These three dimensions […] of dialogue are writing subject, addressee, and exterior texts” (Kristeva, 1986, p.36). In this quotation Kristeva is arguing that word is a product of word definition, as well as being influenced by upwards of two prospective of intertexuality at any given time. To her, even a single word isn’t a stable thing; it is ever changing due to the readership which alters the word from the literal or connotative meaning to one of perception that is influenced by many factors. This point in her essay I strongly agree with as I can understand how, for example, the word ‘Apple’ could be understood in a myriad of ways. Today this could be a reference to the fruit, a colour, a first or surname, an acronym, a band, a technology company and many other endless associations. The listener and the speaker could take a very different meaning from the simple word ‘apple’. In the same way, the novel can be read in a way that derives from the authors intentions by any reader, and each reader can perceive the same novel differently from the other members of the novels audience, in this way the novel is dialogic as there are no right, wrong or otherwise ways of reading, all readings including the intended and the perceived are valid and present with in the text.The author Virginia Woolf arguably portrays the dialogic in experimental novel, entitled The Waves (1931), in which the characters dialogue is the main body of writing and the prospective and character’s voice within the dialogue are ever changing. This could be seen as Woolf using a literal diologism in her text to create waves of consciousness; also she chooses her characters to have different backgrounds to conjure different expectations of the characters in the readers attempting to represent all of the aspects that effect writing to make it become dialogic. This could also be to represent national language, which is the language group formed of regional words etc. which I write about later. In a sense, intertexuality is a form of diologism, being that a reader and author brings their intrinsic and extrinsic experiences to what they are reading and by doing this they shape the novel in a dialogic way. An example of this can be seen within the literary genres, as for a novel to become of a set genre the author must intentionally apply conventions and techniques of the desired genre to their writing for it to work successfully. In Gothic genre, set preconceptions of intertexuality are present, I will explain using the ‘vampire’. In Bram Stokers Dracula (1897), the most famous vampire in literature had ratty teeth and for a long time this was their appearance until Hammer Horror (1970s) films adapted the vampire to have two pointed fangs, the ratty teeth were no more; soon the vampire became sparkly and gentle in the works of Stephenie Meyer’s Twilight. Yet some aspects do not change, like the dark clothing, telepathy, the drinking of blood etc. This shows how past examples of a subject is present in subsequent novels, even if they become adapted due to centrifugal dialogic forces.

In her essay Kristeva explores Carnival in relation to the dialogical novel, explaining that dialogism give way to carnival as they both explore the perceptions of the many. She believes that all novels are carnival novels due to the expression of the public and the private languages with in the texts, she writes that;

Carnivalesque discourse breaks through the laws of language censored by grammar and semantics and, at the same time, is a social political protest. There is no equivalent, but rather, identity between challenging the official linguistic codes and challenging the official law.In this, Kristeva is arguing that carnival is now a set feature within the novel and that the carnivalesque can be present in novels despite the author’s intentions. Carnival has a way of entering a novel through diologism. It is notable that term of ‘carnival’ was discovered by Kristeva in the work of Bakhtin’s Discourse in the Novel (1935). Bakhtin wrote;

(Kristeva, 1986, p36)

At the time when major divisions of the poetic genres were developing under the influence of the unifying centralising, centripetal forces of verbal ideological life, the novel – and those artistic prose genres that gravitate towards it – was being historically shaped by the current of decentralising, centrifugal forces […] poetry was accomplishing the task of cultural, national and political centralisation of the verbal ideological world in the higher official socio-ideological levels, on the lower levels, on the stages of local fairs, buffoon spectacles, the heteroglossia of the clown sounded forth, ridiculing all. (Bakhtin, The Dialogic Imagination;Discourse in the Novel, 1975, p.273)In other words, Bakhtin is arguing that whist the official literary language was successful in the history of society; the diologism of life still influenced the lower forms of the literary arts in a protest to monologic forms of literary arts, as form of rebellion against the latter and a celebration of satire, dialects and the unusual, etc. Through these acts of street plays etc, language was brought to the lower classes in their national language through spectacle and this influenced the shaping of the novel.With this in mind, Kristeva builds her argument that all novels are carnival due to this shaping. In the quotation;

Within the carnival, the subject is reduced to nothingness, while the structure of the author emerges as anonymity that creates and sees itself created as self and other, as man and mask… The carnival first exorcises the structure of literary productivity, then inevitably brings light this structure’s underlying unconsciousness: sexuality and death. Out of dialogues that appear to be established between them, the structure dyads of carnival appear: high and low […] the carnival challenges of god, authority and social law; in so far as it is dialogical, it is rebellious. (Kristeva, 1986, p.49)Kristeva argues that carnival can be in the novel despite author’s intentions (Richardson’s Pamela, which could be read as a character of pure womanhood and virtue, as the author intended, or as something else, such as a satire to the absurdity of such a woman). Kristeva also argues in this quotation that by the novel having the presence of one in a novel, (e.g. laughter) the other (e.g. tears) is also present, this also relates back to dialogism as the reader will associate positives with their opposites unconsciously. She goes on to write that “The scene of carnival, where there is no stage, no ‘theatre’, is thus both stage and life, game and dream, discourse and spectacle.” (Kristeva, 1986, p.49). However, there is an irony with in the argument of carnival by both the theorists, as by presenting a law in which carnival works, they are structuring what they observe that can not be structured, thus counter arguing themselves.The novels that do not fit to Kristeva’s theory that all novels are carnival, she briefly refers to as ‘epic’ novels. This seems to the crucial setback in her theory which she doesn’t allow much counter argument against. She writes that the epic is ‘an extra-textual, absolute entity […] that relativizes dialogue to the point where it is cancelled out and reduced to monologue’ (Kristeva, 1986, p.57). This section reads differently to the previous points of the essay, not sounding as convincing and almost desperate due to the amount of diagrams she uses to try explaining her point. This seems as though she knows that they are flaws to the theory but dos not want to recognise them enough to cancel out her own argument. I understand why she does this as there are many more examples of novel that fit to her theories than go against.

The novel is a very complex form of literacy and by being such it would be much too simplistic to apply the theory of poetry to it; the novel can not be monologic no more than life can be. As a form, it is designed to be the means to which individuals can relay information to one another, express experiences, rebel against the repression of society and ultimately invoke thought and ideas of others mentally and physically. To suggest that a novel is dialogic is to suggest that it is not a novel at all, and to say that a novel isn’t an exploration of carnival (even in the most minor way) is just as detrimental. The word is the expression of human life, the novel is a collection of words, and the novel therefore is human life in word form.

Bibliography

Bakhtin, M (1975). The Dialogic Imagination. Texas; University of Texas Press.Eliot, G (1859). Adam Bede. Scotland; John Blackwood Publishing.Kristeva, J (1986. Word, Dialogue and Novel). New York; Columbia University Press.Richardson, S (1740). Pamela. London; Messrs Rivington and Osborn.Woolf, V (1931). The Waves. London; Hogarth.

Thank you for reading. Please show your support by clicking like, commenting and following.© Kate Ruston and Happy Little Narwhal 2016. Unauthorized use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this site’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Kate Ruston or Happy Little Narwhal with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.

Like us on FacebookMy e-Books: From the Watchtower The Blind Kings Sons

Harry Potter and the Gothic Genre

January 9, 2015

Woolf’s 'The Waves'; Modernism, Realism and Post-Structuralism

Through the course of this essay I will look at Woolf as a modernist writer and how she uses the Waves (1931) to rebel against and address issues in the design of realist novel, this primarily being that they are unrealistic to life, therefore unrealistic to the novel. However, this novels lack of realism, in the conventional sense, should not question its place with in the form of the novel, even though critics such as Watt (1968) would argue that realism is one of the defining features of the novel form. Woolf appears to be employing post-structuralist ideas within the text in order to address her problems within the standard, realist novel. I will be arguing that Woolf’s novel is with the product of the experimental idea of trying to form life into an accurate narrative, which was initiated by the post-structuralist arguing that language, therefore the novel, is a representation of life.

Through the course of this essay I will look at Woolf as a modernist writer and how she uses the Waves (1931) to rebel against and address issues in the design of realist novel, this primarily being that they are unrealistic to life, therefore unrealistic to the novel. However, this novels lack of realism, in the conventional sense, should not question its place with in the form of the novel, even though critics such as Watt (1968) would argue that realism is one of the defining features of the novel form. Woolf appears to be employing post-structuralist ideas within the text in order to address her problems within the standard, realist novel. I will be arguing that Woolf’s novel is with the product of the experimental idea of trying to form life into an accurate narrative, which was initiated by the post-structuralist arguing that language, therefore the novel, is a representation of life. The Waves (1931), as a modernist novel, pushes the boundaries of the standard novel form. In the Waves‘Introduction’, Parsons (2000) writes how this is supported in the way that this text is read differently to the conventional narrative, its arrangement being much closer to the medium of music, writing to a rhythm not a plot; it is due to this key factor that this novels true literary form is often questioned. This novel was labored over much more than Woolf’s previous novels in which two full drafts were made, reflecting Woolf’s ‘ever-increasing concern with the inflexibility of language and the need to accomplish a greater elasticity of expression with the novel form’ (Parson, 2000, p.iv). This novel, through its conception to its creation, was an experimental text, which Woolf feared would be incoherent, due to its contrast to the standard novel, to the majority of readers. Keep, McLaughlin and Parmar writes;In literature, the movement [modernism] is associated with the works of Eliot, James Joyce, Virginia Woolf, W.B. Yeats, [etc.] in their attempt to throw off the aesthetic burden of the realist novel, these writers introduced a variety of literary tactics and devices. […] Modernism is often derided for abandoning the social world in favour of its narcissistic interest in language and its processes. Recognizing the failure of language to ever fully communicate meaning […] the modernists generally downplayed content in favour of an investigation of form. (Keep, McLaughlin & Parmar, 1993) With this in mind, this texts form is clearly a modernist attempt of addressing the function of realism within the novel. In this novel, Woolf is questioning the fundamental role that realism has within the novel, seeing it as a contradiction. She is viewing the structural techniques used within these realist texts to be an unrealistic processing of the written word and of human experience. Indeed, through the use of the ‘stream of consciousness’ technique in the Waves (1931) she is endeavoring to re-create the true realism of the mind. However, the result is that the Waves (1931) is a novel that is rather unstable in form, as it struggles to fit within any single form of literary text; with Woolf often referring to it as a ‘Play-poem’, that address the unconscious aspects of being, rather than a novel. However, there are many aspects of the text that place it within the form of the novel, such as its use of ‘dialogism’ (many voices within the text, rather than one singular voice of the author) that helps to create reliability which is lost though the lack of realism in the text, which build upon the novels essential goal of exploring the reality of selfhood and life.

In the novels, interludes are used at the beginning of each of the nine parts, setting the scene of the time of day and the stage in the lives of the six characters, acting as waves that push the flow of the narrative. The interludes provide boundaries that help to shape the text, which can appear to be a collection of soliloquies or monologues through its use of its characters dialogue. Parsons writes that ‘the metaphor of the waves provides the formal structure for the presentation of these lives’ (Parsons, 2000, The Waves ‘Introduction’, p.vi), aiding the suggestion that these interludes are to help engage the reader with the text by Woolf framing her experimental writing within small sections of more standard and realistic writing in order to achieve clarity and foot hold for the reader that it searching for plot. Yet, these interludes can interfere upon the narrative and its rhythm, thus pointing out the flaws of realism within texts. Undeniably, the interludes create a contradicting duality towards realism in the novel. Watt writes that realism;Is the distinctive narrative mode of the novel. [It is] the sum of literary techniques whereby the novel’s imitation of human life follows philosophical realism in its attempt to ascertain and report the truth. The novel’s mode of imitating reality may therefore be equally well summarized in terms of the procedures of another group of specialists in epistemology: the jury in a court of law. Their expectations and those of the novel reader coincide in many ways: both want to know all the particulars of a given case.’ (Watt, 1968, the Rise of the Novel, Chapter I).

In this sense the Waves (1931) largely challenges realism place within the novel, as it contests this direct relationship between author, content and reader (which links to my point about Kristeva’s, 1986, three textual dimensions, p. 5). This novel never fully addresses ‘truth’ as it favors observations of the ‘truth’ which, paradoxically, is more realistic to life. Furthermore, its use of ‘stream of consciousness’ this text is insistent on creating a hyper-reality that is as close to first hand human perception as is possible within the written word. In this respect, Woolf’s text is questioning how a realist novel could be labeled as realistic as the language and form of realist text are not realistic in the logic of the human mind and experience. Yet her text is not coherent within the logic of the standard novel form.Indeed, Woolf is using her novel to explore the essence of realism of self and what it is to be an individual. Moreover, she is using this form to highlight contradictions found in life and selfhood by putting a ‘true’ realism into the form of the novel. We can see this in her use of characters;In the Waves she considered the six monologists as facets of one, larger complex identity, writing to G.L Dickinson that. ‘I did mean that in some way we are the same person, and not separate people. The six characters were supposed to be one’, and continuing, ‘I come to feel more and more how difficult it is to collect oneself into one Virginia…’(Parsons, 2000, The Waves ‘Introduction’, p.x)

By Woolf using six characters in her novel, she relates to the ways in which selfhood is divided. In the text Woolf intentions are shown in the character of Barnard who affirms that; ‘I am not one person; I am many people; I do not altogether know who I am – Jinny, Susan, Neville, Rhoda or Louis: or how I distinguish my life from theirs’ (Woolf, the Waves, 1931, p.156). This split of character/personality is in order to follow the many paths that an individual could journey, a task that realistically can not happen, hence why Woolf may have been inclined to create an anti-realism text. Moreover, as a result of this, Woolf is addressing the centrifugal forces (unbalanced events of life that are beyond control) in life and the novel that pull away from selfhood. Structuralists believe that the novel was void of centrifugal forces, however Bakhtin (1975) wrote otherwise, saying that the novel was much more complex and was under constant shaping by theses centrifugal forces due to the novel being the literary expression of life (The Dialogic Imagination, 1975, ‘Discourse in the Novel’, p.271). With this in mind, we can see how a modernist writer would utilize this theory that challenged the form of the novel in their own writing, in order to further the exploration and experimentation with the novels form in order to further explore their topic, life.The Waves (1931) relates heavily to Kristeva’s (1986) theories of ‘dialogism’ (the theory that all novels are a multitude of voices) which she constructed from the work of Bakhtin (The Dialogic Imagination 1975, ‘Discourse in the Novel’). Before the work of Bakhtin (1975), structuralism was the common method of interpreting a novel. Structuralism is a method towards interpreting the novel as a methodical, narrow structure which has a set path through which authors explore life through their texts. They viewed and critiqued the novel with fundamental ideas that the novel was monologic (a single voice, i.e. the authors). As Bakhtin (1975) was a Russian writer, his ideas did not reach the west until Kristeva (1986) wrote and elaborated upon them, arguing that the novel was in fact dialogic (many voices) due to her idea that even the singular word was dialogic (see below, three textual dimensions). Modernists, such as Woolf, explicitly illustrate in their text how this ‘dialogism’ is present through their use of experimental forms. As this text uses the voices of six personas to create a wave of consciousness, wherein the voice is constantly changing through the dialogue and prospective of the characters, Woolf is creating an apparent ‘dialogism’. All characters represent different life directions and backgrounds which influences the readers’ expectations of the character. This relates to Bakhtin’s (1975, p. 271) argument that the language of the novel, as with the language of life, is shaped by the heteroglot national language (colloquial speech, dialects etc.), rather than the ideological and monologic official language. However by the Waves (1931) being rather difficult for the average reader due to its form, Woolf somewhat questions the use of a heteroglot national language, as her book, like the official language, alienates lower classes. But by creating characters that represent very different roles and ambitions in life we can see that Woolf is attempting to represent the national heteroglot and the diversity of language. Woolf may be exploring the three dimensions of textual space that Kristeva Word, Dialogue and Novel (1986) addresses. In the quotation, Kristeva writes that the “three dimensions [of language ] are writing subject, addressee, and exterior texts” (Kristeva, 1986, p.36), meaning that the word and therefore the novel is a product of word definition, which is unstable due to the perceptions of the writer, literal definition and reader. We can see that Woolf is exploring this in her work by having each character deal with similar and overlapping ideas/themes. Indeed in a sense, all six characters represent an exaggerated example of how in all novels there are an overlapping of ideas and themes that is deeper than plot.

The Waves (1931) is not a standard example of Novel, however it is a crucial example of how the novel is shaped and re-shaped over time, representing the era of the modernists and the need to allow different formats and techniques within the novel form. It is a model of how this form shouldn’t rely upon ridged, structuralist rules over language and structure, as the novel is a written representation of life and selfhood, which I believe is the main effect that the form of the Waves (1931) creates for the reader. It is through experimentation that the novel should both explore and evade from the techniques found in realism novels, in order to evolve into a written ‘truth’ that is as close to life as a work of literacy can become.

Bakhtin, M (1975). The Dialogic Imagination. Texas; University of Texas Press. Blackburn, S. (2008) Oxford Dictionary of Philosophy, second edition revised. Oxford: Oxford University Press.Keep, C. McLaughlin, T. Parmar, R. (1993). Modernism and the Modern Novel. Accessed [Internet] < http://www2.iath.virginia.edu/elab/hf... Last accessed; 10th May 2013.Kristeva, J (1986). Word, Dialogue and Novel. New York; Columbia University Press.Parsons, D (2000). The Waves ‘Introduction’. Wordsworth Classics, Hertfordshire. Woolf, V (1931). The Waves. London; Hogarth.

Watt, I (1968). the Rise of the Novel. Chatto and Windus Press, London. ‘Realism and the novel form, Chapter I, p.9.

Thank you for reading. Please show your support by clicking like, commenting and following.© Kate Ruston and Happy Little Narwhal 2016. Unauthorized use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this site’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Kate Ruston or Happy Little Narwhal with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.

Like us on FacebookMy e-Books: From the Watchtower The Blind Kings Sons Harry Potter and the Gothic Genre