Solitaire Townsend's Blog

January 25, 2026

Where's Granny Weatherwax When You Need Her?

I’m old-ish. Not very old, as in happily retired, or really old, bundled up in a care home.

But not young. My knees hurt, I have LOTS of memories, and those memories act as a buffer against the horrors of the world.

Not because today’s horrors aren’t upsetting and overwhelming. But because they aren’t the first horrors I’ve seen. They don’t have the fresh bite unfamiliarity, like when I first saw them.

I’m not sure I’m very wise, although that was the promise of getting older. ‘Old and wise’ seemed like a reasonable deal. To trade the painful innocence of youth for a touch of sagacity as the years pass. Fresh skin is always thin. The folds around my eyes aren’t just from laughing, and now it takes a lot to get tears falling from them.

But I sometimes wonder if the change movement wants what we have anymore. Not a ‘bright young thing’ anymore, but not yet a sage and frail elder.

I’m Gen X, that oft-overlooked group huddled between the Boomers and Millennials, ducking as those two throw missiles at each other.

What do you call a sturdy woman with half a decade’s experience, muscle memory for what works, a world-spanning network, and ever-decreasing patience?

As we Gen X female activists plough into menopause, what are we?

Middle-aged, mature, vintage, wise women…

…Crones?I rather fancy becoming a crone. Not least because of one fictional witch who climbed under my skin when it was still bright and unlined.

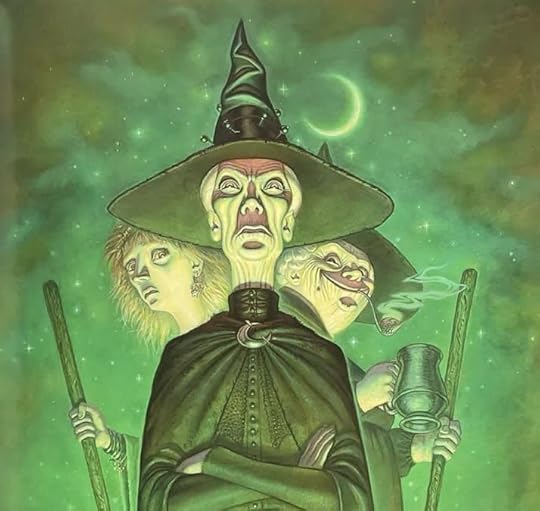

Granny Weatherwax is the greatest witch in Terry Pratchett’s Discworld novels, though she’d never admit it. She lives alone in a cottage in the mountains, wears practical black, and has a stare that could stop a charging bull. She’s described as handsome rather than beautiful, with steel-grey hair and a face carved by decades of hard decisions.

To me, even back when I crimped my hair and wore a leather jacket, she was deeply desirable in that way that comes from absolute self-possession and zero tolerance for nonsense.

When younger witches try to impress with flashy spells and dramatic gestures, Granny Weatherwax simply says: “It’s still magic even if you know how it’s done.”

The power which most impressed me? “Headology.” Understanding people so well that you can change their minds without ever lifting a wand. As she puts it: “You can’t go around building a better world for people. Only people can build a better world for people. Otherwise it’s just a cage.”

She doesn’t wield a sword, ride a white charger or command armies. She isn’t a ninja, a dragon slayer or even much of a community leader. Most people irritate her.

But she saves them anyway. With an eye roll and deep sigh, she’ll convince the dragon to slay itself if it’s besieging the village. Even if the villagers are unbearably annoying.

Granny Weatherwax isn’t filled with righteous passion, that’s for young girls with long hair wafting behind them as they hold their innocence as shield against the horrors.

Instead, she’s tired, harried, with bad knees and a desperate need for a cup of tea.

But she changes the world.

Because that’s what crones do.

The Crone ImperativeAs I head into menopause (aka cronedom), I can’t help wondering why this is happening. Is it supposed to help?

From a purely biological perspective, menopause has puzzled evolutionary theorists since science began. Why would a species “stop” female fertility while keeping women alive for decades afterward?

In most species, females can still breed into advanced old age.

The most interesting (and accepted) explanation is the Grandmother Hypothesis, proposed and refined by evolutionary anthropologists like Kristen Hawkes. This theory argues that post-menopausal women increase the survival of the group by reallocating energy away from childbirth and toward knowledge transmission, resource management, and social cohesion. In short, menopause is a societal necessity because older women know stuff, which is more valuable than making more babies.

This pattern is not entirely unique to humans. Female orcas also experience menopause, and post-reproductive females guide their pods through periods of scarcity, using memory and experience to locate food and reduce risk. When elder females die, overall group survival drops sharply. Knowledge, it turns out, is as valuable as reproduction.

Human societies once understood this intuitively.

Across Indigenous cultures, older women traditionally held authority precisely because they are no longer bound by fertility or male approval. In many First Nations communities, menopausal women became elders with decision-making power over land, conflict resolution, and ritual life. In parts of West Africa, post-menopausal women historically held exclusive rights to adjudicate disputes or speak in councils where younger women could not.

In East Asian philosophy, ageing women were often associated with yin wisdom: depth, stillness, and perceptive power. Even in medieval Europe, before the witch hunts catastrophically inverted the narrative, older women were healers, midwives, and keepers of ecological and medical knowledge. The persecution of “witches” was not only misogynistic; it was a systematic removal of female authority at a moment when centralised power felt threatened.

The crone has always been dangerous to unstable systems.

Sound familiar?

The Witches We NeedThe climate and justice movements have an abundance of passionate youth, brilliant scientists, and well-meaning corporate executives. What it lacks is crones.

Crones. The archetype of the woman who has lived long enough to know what matters, who has zero patience for performance, and who wields her power with precision rather than spectacle.

The crone speaks uncomfortable truths because she’s done caring whether you like her. She sees through greenwashing, political doublespeak, and performative activism with a single raised eyebrow. She doesn’t wait for permission or apologise for taking up space.

But nor will she accept injustice, exploitation or wanton destruction.

For too long, we Gen X women have been told to stay young, soften our edges, and perform our competence ‘with grace’. We’ve watched younger generations celebrated (and patronised) while our decades of experience are dismissed. We’ve been marketed anti-aging creams and dodgy menopause supplements while our wisdom has battled to break through.

We sit at a rare historical intersection. Gen X are the bridge generation between analogue and digital, between institutional trust and institutional collapse, between optimism-as-default and realism-as-survival skill.

Meanwhile, the planet burns and the people in charge keep making the same mistakes we’ve been warning about for thirty years.

And we’re tired and annoyed enough to try and change everything.

Headology Over HeroicsGranny Weatherwax rarely uses flashy magic. She could, but she won’t. “It ain’t what you do, it’s the way that you do it,” she says.

We need headology. The deep understanding of human psychology that lets you shift how people see themselves and their choices. The patience to work with people where they are, not where you wish they were. The moral clarity to know what’s right without needing to prove you’re righteous.

Granny Weatherwax never tells people what to do. She arranges circumstances so they choose rightly themselves. Because she understands that lasting change comes from within, not from being lectured or shamed or dazzled.

She also knows when a little pain needs to be mixed into the patience.

Your Crone Power AwaitsIf you’re a Gen X woman reading this, you already have crone powers. You’ve been developing them for decades, probably without realising it.

You know how to read a room in seconds. Spot bullshit from across a conference hall. We’ve all watched enough trends and fads and false promises to recognise what actually works. And we’ve all been dismissed enough times that we’ve stopped needing external validation.

You’re also gorgeous. Not despite your age, but because of everything you’ve lived through and learned. Like Granny Weatherwax, your power makes you magnetic.

Will you use it?

Here’s the thing about crone powers: they’re not actually about gender or age. They’re about wisdom, autonomy, and the courage to speak truth. So yes, men can embrace their inner Granny Weatherwax too. Anyone can choose to stop performing and start getting things done.

Gen X women just have a head start. We’ve been practising these skills in hostile territory for our entire careers.

The climate crisis needs Granny Weatherwaxes. Plural. An entire coven of us, scattered across industries and communities, using our powers of headology to shift minds, change systems, and build a better world with people, not for them.

So trust your decades of experience. Use your power with precision.

And when someone tries to dismiss you, just give them the Weatherwax stare and get back to work.

Because we aten’t dead. And there’s a world to save.

⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐

For a touch more magic, read my new novel, Godstorm.

January 18, 2026

My Goddess Of Oil

My new novel, Godstorm is (supposedly) a fantasy. A world where the Roman Empire never fell, its gods evolved with its machines, and the divine spirit of petroleum, Gaea, is worshipped as the mother of civilisation.

Oil is called ‘Gaeas Blood’, a thick black blessing from the body of a goddess, gifted to the Roman Empire as divine anointment of its right to rule.

I didn’t write this by accident. Because if climate storytelling is going to be truly effective, it must reflect the entirety of the human experience - including the divine.

My Godstorm world boasts petrol altars, holy refineries, and sacred chariots burning her blood in reverence:

“They passed a statue of Gaea herself: a generous and motherly naked body with sad countenance, her hands reaching down from the pedestal as if to lift a supplicant. The statue had oil rivulets running from her eyes, her breasts, and from between her legs. It was supposed to represent her great gift and sacrifice for the Roman people.

Arrow thought it looked painful.

They stopped under the large silver model of an oil rig that dominated the centre of the room, glinting in the lamplight. Arrow’s nose stung with the evaporated chemicals rising from the huge bowl of crude oil the rig stood within.

Grand as the Temple rig was, it was merely a symbol for the colossal metal pyramids that dominated across leagues of the fire plains in the East. It was said you could walk for a month across the plains and see nothing but rigs, slaves and the giant charnot convoys transporting millions of barrels of oil to ports for trade. During the Festiva of Gaea, the rig bosses would burn up entire lakes of oil, releasing thick black clouds a hundred leagues high, proving their piety and guaranteeing the gods would keep the liquid gold pumping for another season.”

My story wouldn’t be nearly as compelling if it weren’t just a single breath away from reality. Our world already worships oil (in all incarnations as petrol, gas, benzine, propane, etc.). We already defend the sacred oil sites with armies, build temples in offshore rigs and petrochemical towers, and measure our worth by how much of the celestial essence we can burn. We dress in this god's plastics, eat from its packaging, and whisper prayers to the mystic markets whenever the price per barrel rises.

If this is not worship, it is at least devotion.

The Divine Made Crude

In Godstorm, the people pray to Gaea for strength and prosperity. Her symbol is the oil rig; her scent is the petrol bloom that rises from sacred engines. They bless their children by dipping their little hands in wide bowls of crude, and praying as the drips of brown-black slip off their fingers.

Their faith is sincere because oil has been miraculous. In just a few generations, it gave the Roman Empire godlike powers: to fly in airships, to travel at speed, to light the night, to move mountains. Oil raised cities and granted dominion over time and distance. It is the nectar that fuelled their myth of progress. Every age has its gods, and theirs came from a well.

Or perhaps I should say ours.

Anthropologists call this resource mythologising: the way humans elevate what feeds or frees us into something sacred. The Egyptians had the Nile, the Norse had Yggdrasil, and the Mayans had maize. Each was more than sustenance; it was meaning. Had the Romans truly invented the internal combustion engine, I have no doubt they would have mythologised it.

Just as we have. In the twentieth century, we replaced the harvest festival with the oil boom. The pumpjack bowed and rose like a mechanical priest, worshipping itself. We have killed more in the name of our oil gods as any frenzied cult has managed.

Yet our god is jealous. Like all powerful deities, it demands sacrifice: forests, coral reefs, stable climates, even the lives of those who live closest to her wells. The oil god’s gifts are rich, but the price is ruin.

Faith, Fact & Fossils

Humans rarely abandon their gods for logical reasons. We stop believing only when a more powerful myth comes along. You can’t replace mythos with measured empiricism. Only a better story can replace a story.

Today, I feel the early stirrings of that new myth struggling to emerge from beneath the oil slick.

We still chant the oil gods' mantras of growth, comfort, and convenience, but they sound increasingly hollow. Floods, fires and storms have become the wrathful angels of a collapsing pantheon. Yet the priests of this old religion still hold power: investors, lobbyists and fanatic politicians who make pilgrimage to Houston instead of Delphi.

We invade nations in the name of The Oil.

The modern world treats oil not as a resource but as a right. Our financial systems are built on it, our politics revolve around it, and our wars are fought for it. We subsidise it at the rate of seven trillion dollars a year according to the International Monetary Fund, as if paying indulgences to a dying god. We trade futures in it, insure it, and pray to it for stable markets. Even the term fossil fuel carries the faint odor of holiness, a relic of ancient life compressed into divine energy.

We speak of energy independence as if it were spiritual liberation, yet we remain bound to the same altar. The extraction continues, the worship deepens, and the smoke of our devotion fills the sky.

And like all fading religions, this one lashes out at heretics. Speak of renewable energy or degrowth, and you are accused of blasphemy against jobs or prosperity. But revolutions often begin with an act of apostasy.

A New Creation Myth

What we need now is not only new energy sources but a story so compelling it converts. As the report Stories to Save the World points out, humans are homo narrans, the storytelling ape, and our myths guide our morals more than our facts do. Even the IPCC has called for new narratives to help people ‘imagine and make sense of the future.’ The climate crisis is the story of our age, and oil is its old god.

It is time for a reformation.

The renewable revolution must not remain stuck as merely an engineering project; it must become a spiritual one. Solar, wind and tidal power represent a return to living gods, the ones we can feel on our skin and see on the horizon. They do not demand sacrifice; they invite partnership. In mythic terms, we are moving from a religion of extraction to a religion of relationship.

Imagine if we told that story. Imagine if our children grew up blessing the wind, not fearing its stillness. Imagine if engineers were priests of light, if architects built cathedrals of efficiency, if every solar panel were a prayer. That is what storytellers are for: to write new scriptures before the old ones destroy us.

From Oil To Awe

This week, Godstorm has finally become real in the world – and people I’ve never met are buying and reading it.

I hope they realise that Gaea’s Blood represents the human impulse to take what is miraculous and make it monstrous through greed. Every civilisation has done it, worshipping its own creations until they devoured their creators.

But we are also capable of re-enchantment. As I wrote in It’s All Going To Be Ok, joy is a connecting force. We can replace the fear of loss with the awe of possibility. Climate action, taken in that spirit, becomes a love story between humanity and the planet, between science and spirit, between us and the future.

The end of oil will not feel like an apocalypse once we understand it as the closing chapter of an old mythology. Every great story must end before the next begins.

If we can make the next one divine.

Please Look At Godstorm!

‘Godstorm is a vivid, ferocious adventure, as the heroine struggles against a world even more violent than our own - or so it seems until you consider matters of scale, and realize this novel is an allegory for our fight too’ - Kim Stanley-Robinson, author of Ministry for the Future

Click these pre-order links to read more:

For all my friends in markets where Godstorm isn’t yet published (such as the USA), hopefully it will be next year, and I’ll keep running the bookplates then.

Thank you so much, wonderful people, for the support.

January 11, 2026

Don't Get Lost In 2026: We Are One Story

If there’s one thing becoming a novelist has taught me: stories are all about people. And if there’s one thing I’ve learnt from my decades of sustainability: people need each other.

The story of 2026 has started, and it’s started hard. Many friends are already looking hollow-eyed and burned out, and we’re not even a fortnight into the year.

Reality is sharp-edged. Which is when I turn to storytelling to remind me how to navigate the cuts.

We think we know stories of the lone saviour, the singular visionary, the one superhuman who saves the world single-handed. But when we revisit those stories, even the superhero ones, we always discover the hero was never alone. There were always allies, friends, sidekicks, deep friendships and even ‘passerby on the street’ helpers.

We all need help, even if we can leap tall building or shoot lasers from our eyes.

In the Japanese legend of Momotarō the hero could cut down a tree with a rusty knife, at just five years old. But he still needed his dog, monkey and pheasant friends to defeat the troll army. Frodo needs Sam, and Batman needs Alfred.

The most powerful stories show us that transformation comes not from solitary strength but from a shared purpose in community. Whether it’s a child gathering animal allies to reclaim his homeland or a revolutionary learning to trust her comrades, stories across cultures remind us: the journey only works when we walk it together.

In 2026 we need this story more than any other.

Group Work Saves The DayIn Sundiata: An Epic of Old Mali, the hero cannot defeat the sorcerer-king Soumaoro alone. He must learn to listen to his sister’s advice and rely on his community.

Scratch the surface of tales about individual triumph, and you’ll find a moral about collective resilience.

Why does that matter for sustainability in 2026? Because stories shape our subconscious understanding of what change looks like. And when we absorb the belief that it’s the “one visionary” who will fix things, we subtly teach people to wait for heroes rather than become part of the movement.

We’re Wired For Collective StoriesThere’s solid science behind why we love stories of togetherness. Studies in neuropsychology have shown that stories involving groups or cooperation increase emotional resonance and oxytocin levels (the bonding hormone). Mirror neuron research has revealed that movie audiences simulate the reciprocal relationships we see on screen, making us more socially responsive.

In short, stories about trust and teamwork make us more trusting and team-oriented.

This is our story for what will be a difficult year.

Yet we still tend to spotlight lone heroes, lone activists, lone consumers doing their best in a broken system. That story might be noble and admirable. But boy, it’s lonely.

If we want a new destiny, we need new story arcs. Stories that move from:

Lone hero ➝ Interdependent allies

Brilliant individual ➝ Beautiful coalition

Personal change ➝ Mutual transformation

Sustainability Isn’t A Solo MissionWhen you tell a story of a neighbourhood installing solar together, or women in Senegal replanting mangroves side by side, or young people in India building citizen science networks to track pollution, you flick that story switch to model a world where we win by linking arms.

Because what stories teach us is that the emotional climax comes not when the protagonist triumphs alone, but when they finally accept help.

The moment when the heroine realises she doesn’t have to carry the burden by herself. When the leader stops trying to save the village for the people, and starts working with them.

That’s the real turning point.

Write The WeSo if you’re a storyteller, a campaigner, or a leader doggedly trying to drive sustainability action in 2026, look around you. Where are your allies, friends, mentors or anyone who feels the same way? Prioritise connecting with them right now, as the year starts.

We need collective resolutions this year!

If we keep telling tales of isolated effort, we’ll keep getting isolated results.But if we tell stories of teams, tribes, coalitions, crews, and communities, then we might just rewrite the ending.

Together.

My Ask For Help :-)

I’m taking my own medicine and asking for your help! Later this week (Thursday 15th Jan), my debut novel Godstorm will launch in the UK, Ireland, Canada and Australia (not yet the USA). You are invited to the launch event - sign up here.

More pre-orders of Godstorm over the next few days will make the biggest difference to whether it launches with a bang or whimper! Bookshops, media and publishers take pre-order numbers as the most important indicator of a book’s likely success. And right now, climate fiction isn’t expected to fly! I’d love to prove that a great adventure story with climate themes (and swords) can buck that trend. THANK YOU!

Your copy of Godstorm can be pre-ordered from:

December 7, 2025

You're Invited! Godstorm Launch Party

This is it, my novel is almost out of the bag! And I need YOU to help celebrate.

I’ve been fingers-to-keyboard writing the sequel to Godstorm (title is still under wraps). But now that manuscript is off to the publishers, my hungry little brain is back thinking about Godstorm and what it’s taught me about climate storytelling.

On January 15th at 5pm UK time, I’ll open the floodgates to your questions! If you’re interested in climate storytelling, you won’t want to miss it.

I’ve decided on an online/virtual launch because I want ALL of you to be able to join. This is a book launch that will become a summit on climate storytelling.

Sign up here to register interest in joining (it’s a Microsoft Teams webinar link - with privacy settings).

When you sign up, you’ll be asked if you’ve preordered Godstorm. WHY? Well, firstly, because we want to prove there’s a market for climate fiction. The publishing industry is wobbling on climate content right now - so let’s show them that people still want to read great storytelling with climate themes!

Secondly, because I’ll send you a beautiful and FREE bookplate, dedicated to you (or a friend) and hand-signed by me.

These are available to everyone who pre-orders from today (if you’re based in the UK).

You can pre-order in hardback, audiobook or ebook and I will send the bookplate!

I recommend these direct links to Waterstones or Bookshop.org - although I’m happy with pre-orders on the ‘zon or anywhere!

IMPORTANT: Use this Google Form to tell me your dedication name and address. If you use the form, then I’ll post your signed bookplate before your books arrive. There might even be a little extra gift in your envelope.

I’m so immensely grateful for every pre-order. The number of pre-orders literally decides if a book will be successful for years to come.

So, if you order five or more copies of Godstorm as gifts for friends, family or colleagues, then of course you’ll get separate bookplates for each one. But also, you’ll be invited to the very exclusive in-person book launch drinks in London on 16th January. Remember to add your email to the Google form, so I know where to send your invite!

Will You Enjoy The Story?

Everyone has different literary tastes. Sometimes my reading palette changes depending on the day or what tea I’m drinking!

The wonderful Kim Stanley-Robinson, author of Ministry for the Future, sent me this review after reading Godstorm:

‘This startling alternative history takes us to a newly-imagined world in which fossil fuels extended the Romans’ conquest of the world through space and time; because energy is power. The result is a vivid, ferocious adventure, as the heroine struggles against a world even more violent than our own - or so it seems until you consider matters of scale, and realize this novel is an allegory for our fight too”

Once you’ve read it, I’d love to know what YOU think :-)

Reminder of the pre-order links:

For all my friends in markets where Godstorm isn’t yet published (such as the USA), hopefully it will be next year and I’ll keep running the bookplates then.

Thank you so much, wonderful people, for the support. And don’t worry, my usual content about sustainability will resume shortly.

October 19, 2025

How To Mask Like An Autistic

Everybody masks, somewhat.

The difference with autistic masking is that it’s a conscious act. A decision to construct a version of yourself that the world can handle.

Put more bluntly: I’m better at masking because I’ve decided to do it.

And I’d like to teach you how.

A Survival ArtBefore I get into how you can mask, let me explain why I have to.

Without a mask, I don’t function. That’s the autistic experience.

It always amuses me when self-help gurus advocate for ‘authenticity’ and always being 100% true to how you feel. Because my truly authentic self is non-verbal, eats only three unhealthy junk foods, wears the same pyjamas every day, stims until I bleed, watches the same show on repeat for years, rocks in place, can’t be touched, and rarely brushes her teeth.

I literally have to mask even when alone.

For people like me, masking is self-protection. And for many autistics, our ability to function even minimally is labelled as low or medium support needs. That label protects our autonomy. That label is what lets me live freely.

Sadly, autistic masking is often misunderstood as mimicry or dishonesty. In fact, researchers describe it as “a complex and effortful process of camouflaging”. Masking is consciously learning and performing social behaviours to blend in or avoid negative judgment. It’s cognitive choreography: watching, analysing, rehearsing, performing.

Yes, that can be as exhausting as it sounds. Studies show that chronic camouflaging can be associated with burnout, depression and anxiety. But for many of us, it’s also the only reason we can go to work, maintain relationships or avoid harm. The price of unmasking is sometimes unemployment, isolation, or worse.

So, what can all this possibly teach the neurotypical majority?

If you’re NOT autistic, keep reading.

Performing FunctionalityI’ve given literally thousands of talks, including a main-stage TED talk. I’ve successfully pitched product ideas that changed categories, launched businesses, led campaigns and advised CEOs and Government ministers.

I’ve done a lot of things that spark anxiety, imposter syndrome and outright fear in most people.

Recently, after hosting a 5,000-person, three-day event in New York City, a colleague asked, “How do you get up there and do all that?” He was baffled that the slightly geeky, autistic woman he knows can stand on stage for hours, chatting with CEOs and Hollywood stars.

My answer was simple: I mask.

And if I have to mask even for everyday efforts. Then why not mask magnificently?

If you’re gonna construct a persona, then make it a good one.

Before every talk, I consciously adopt the version of me who is confident, relaxed, powerful (intimidating even), and entirely in charge. A mask that’s very different from the version of me who can’t ask someone to move their bag on a crowded train.

That confident stage persona is no accident: it’s a construction. And it’s a construction anyone can learn.

And learning it just might help you unlock a version of you that you’ve always wanted to be.

The Psychology of the MaskSocial psychologists have long known that behaviour shapes emotion as much as emotion shapes behaviour. We quite literally are what we do.

Exciting facial feedback research found that smiling, even artificially, can actually make you feel happier.

That’s masking 101.

Autistic people do this deliberately and with great precision. We become experts in micro-behavioural engineering: adjusting our voice tone, gesture, eye contact and rhythm. Over time, those skills become tools for navigating a world designed for other minds.

For neurotypicals, these same tools can be applied to overcoming fear, public speaking anxiety, or imposter syndrome.

A meta-analysis by Keltner and Lerner found that role-playing confident behaviour (even when privately rehearsed) measurably improves performance under stress. And “self-distancing” studies suggest that referring to yourself in the third person (“Solitaire can do this”) helps manage anxiety before difficult tasks.

Autistic masking is these techniques turned into an artform.

Exquisitely MaskedDuring my autism diagnosis, my clinical psychologist called me ‘exquisitely masked’. It took me months to realise she hadn’t meant it as a compliment.

But I’ve decided to take it as one. Because I believe masking is exquisite. It’s a beautiful skill, hard-learnt, that allows many neurodivergent people to survive, thrive, and even lead. We choose the masks we wear, and some of us have constructed ones that have changed the world.

My masks are authentic because I choose to use them.

You’re already masking, of course. Sociologist Erving Goffman argued that all human interaction is performance. We each wear different masks: parent, colleague, friend, lover, switching between roles depending on who we’re with. Your wardrobe literally has different ‘costumes’ for different situations. The difference is that most people do it intuitively. Autistics do it deliberately, consciously, sometimes painfully…and therefore, masterfully.

Making Your MaskSo, how can you learn to mask like an autistic? Start by identifying the version of yourself you want to project in a particular situation. Then build that version intentionally. Here’s how:

Model, don’t mimic.

Observe someone whose confidence or calmness you admire. Notice their posture, rhythm, micro-expressions, and verbal pacing. Translate what fits your own physiology and context.

Match your style.

The most effective masks amplify a truth about you. If you have something to say, but are scared of public speaking, then build a mask to speak your truth on stage. Highlight traits you already own, not fictions you must maintain.

Micro-dose exposure.

Practise your mask in low-stakes environments like a small meeting before a conference or a friend’s dinner before a networking gala. Gradual exposure rewires the stress response, making masking easier.

Script key lines.

Autistics often pre-rehearse our social scripts. Neurotypicals can use the same trick. Prepare opening lines, transitions, and your exit phrases. These scripts free up mental space for genuine engagement.

Build a physical cue.

Carry a talisman like a ring, watch, pen or even a pretty stone (an autistic favourite). These can become your ‘mask switch’. Touching or holding the talisman reminds you of your chosen state. Athletes and performers use this technique routinely. Autistics tend to have pocketsful of them!

Practise reframing.

When anxiety hits, re-label your physiological arousal. My favourite is to tell myself, ‘My heart’s racing because I’m excited’ when anxiety hits.

De-brief your mask.

After each masked moment, note what worked, what drained you, and how positive it felt. Adjust the design of your mask like an engineer fine-tuning a prototype.

Respect recovery time.

Masks drain energy. Schedule decompression afterwards: silence, stimming, or sensory retreat. Recovery protects against burnout.

If you’re learning to mask like an autistic, then don’t forget that final step. Conscious masking takes effort, and you’ll need to rest after spending it.

Free your MaskThere’s a strange liberation in masking. The deliberate act of constructing yourself can make you more, not less, authentic. Because once you realise that authenticity is itself a social construct, you get to choose who you want to be.

Neurotypicals often fear masking because they equate it with fakery. But fakery implies deceit; masking implies agency.

So yes, I mask. Every day. I choose which version of me can best survive the moment or seize the opportunity.

And maybe that’s something the whole world could learn from autistic people. Because if we can construct selves to survive systems that weren’t built for us, perhaps everyone can learn to construct selves that rise above fear, doubt and inertia.

Masking is an art of becoming. One that anyone can learn.

October 13, 2025

UNF*CKING OUR CLIMATE STORY

Every great story begins with an ‘inciting incident’.

That’s the moment when the ordinary world cracks, when the hero is shaken awake. The ring is left on a hobbit’s mantelpiece. The message flickers from Princess Leia. The sky burns, the monster rises, the truth is revealed. It’s the moment the story really starts.

In my new novel Godstorm, it’s when a child is abducted during a climate-induced hurricane.

But reality rarely fits the strictures of excellent storytelling. We need to make it do so.

For climate, that’s going to mean moving on from the inciting incident we’ve been stuck in for literally decades, our story stalling, and action waiting for us to move on.

For too long, climate communicators have treated science as our inciting incident.

We’ve believed that if we simply presented the charts, the models, the melting ice, then people would leap from their sofas, grab their cloaks and swords, and set out to save the world.

That worked for some. The bold, the believers, the already-converted set off at once. But for everyone else, the call to adventure has been… ignored. Or worse, politely declined.

Because we’ve forgotten a crucial rule of storytelling: the inciting incident only matters if the audience knows they’re the protagonist.

The Call We Keep Refusing

Every good story has a moment of refusal. Luke doesn’t want to leave Tatooine. Frodo says, “I’m not made for adventures.” Katniss just wants to keep her sister safe. The refusal is human; it’s the trembling before transformation. As an author, that’s juicy material full of human turmoil, and excellent fodder for emotion-tugging prose.

That can only last a page or two before the reader gets bored.

But the climate story has been looping in that scene for thirty years.

We keep sounding the alarm, waving the graphs, replaying the warnings. We’ve become the anxious mentor in the hut, shouting “the world is ending!” while the potential heroes stare into their phones, waiting for someone else to pick up the quest.

It’s not that people don’t care. It’s that we never truly invited them into the story.

We’ve told them what’s happening to the planet, not excited them with the adventure.

We’ve shown them villains, but not given them agency.

We’ve cast them as audience members, extras, or at best “conscious consumers.”

In gamer lingo, they’re non-playable characters: moving through the climate world, affected by every update, but never handed the controller.

NPCs Don’t Save The World

Climate doom has been a powerful narcotic. It numbs guilt and pain, and it flatters the ego, because if the world is doomed, then our inaction is no longer cowardice, it’s resignation. And that’s so much easier to live with.

But NPCs don’t write myths. They don’t plant forests or overthrow empires.

They simply watch the game unfold until the credits roll.

And yet, look at what we’re surrounded by: real, breathing, feeling human beings capable of astonishing courage. People raising children in a burning world, inventing cleaner ways to live, making art that touches the soul of the crisis. We are the main character already in motion, we just haven’t realised it yet.

Why Science Can’t Start The Story

Science is essential. But science doesn’t make us move. Story does.

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change can describe the dragon; it can’t make us pick up the sword.

In storytelling terms, the climate movement has mastered world-building but forgotten character-building. We’ve mapped the terrain of catastrophe, but not the internal journeys of the people within it. The plot twist we need is a shift in identity, not another data set.

Because when people see themselves as protagonists, everything changes. The same flood becomes a challenge to overcome. The same solar panel becomes a symbol of defiance. The same act of hope becomes contagious.

The real transformation happens not when we say “the planet is dying,” but when we whisper, “You can change this story.”

The New Chapter Begins Here

That’s why I’ve helped launch the Fuck Doom campaign.

Because our cultural story has stalled in Act One. Because the doom narrative has eaten our imagination. Because we deserve more than tragedy.

Fuck Doom is a call to reclaim agency, creativity, and courage from the jaws of fatalism.

This campaign isn’t about denying danger. It’s about rejecting despair. And finally stepping into the adventure we were always meant to live.

So here’s your invitation:

You’re not an NPC.

You’re not an extra in the apocalypse

You are not background noise in the great story of survival.

You are the main character. The one holding the controller. The one who can change the ending.

It’s time to move past our inciting incident.

Because the climate story isn’t over. It’s barely begun.

++++++++

Godstorm is now available to pre-order in the UK (link goes to Waterstones).

These pre-orders are vitally important! So important in fact, that in the next few weeks I’ll send a free, beautifully designed bookplate, hand-signed and dedicated to you, to anyone with proof they’ve pre-ordered! So please get your copy, and send the receipt/email confirmation of your order to hello@solitairetownsend.com

Remember to tell me the name you’d like the bookplate dedicated to!

⭐THANK YOU⭐

October 5, 2025

'Cathedral Thinking' Can Make You Happier (& Change The World)

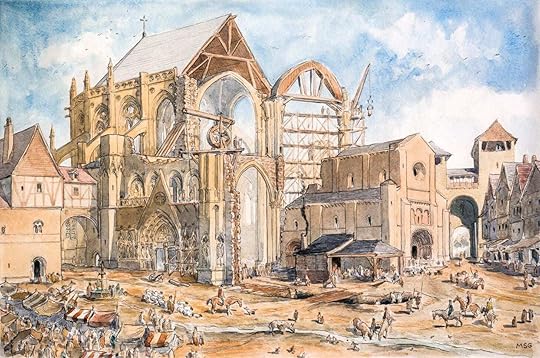

I must ask my father where the box is now. As a child, he would sometimes bring out his collection of treasures for my sisters and I to gawk at. Old coins, clay pipes and even interesting stones.

Each little trinket and treasure found between two giant slabs of stone laid down centuries ago.

Dad was a stonemason, a job that occasionally involves removing a worn or damaged stone from one of England’s many churches, cathedrals and ancient buildings. Most of these long-standing constructions have an inner and outer ‘face’ of stone with a rubble and mortar core.

It makes them incredibly stable, and also leaves a secret ‘gap’ where stonemasons who constructed them could leave a message, or a little gift, to the generations hence.

Your average time capsule has nothing on this. Dad would find 500-year-old graffiti on the back of the stones, the mason’s children’s names or often just shapes (unsurprising considering literacy rates at the time). Plus little offerings, often of a pipe.

These people knew they were building for the long-term. A cathedral would often take generations to build, with the expectation that it would then stand forevermore.

What an incredible mindset to hold. That with luck (and the effort of future stonemasons), your works would last long after your name was forgotten.

At least, forgotten until a future mason found it carved on a clay pipe you’d hidden, just for him to find.

A short-term world

We live in a culture fevered by immediacy. The next quarter’s growth, the news alert, the scrolling feed. That conditioning warps our sense of agency and scale.

Psychologists call this temporal discounting, the bias by which people prefer smaller, sooner rewards over larger, later ones. Our brains are wired to devalue what lies in the dimmer future. This helps explain why we struggle to save, to plan, to act on climate or justice beyond our own lifetimes.

And it’s making us sad.

A 2023 systematic review of future-oriented thinking found that people who focus more on the long-term future show higher well-being, stronger goal persistence and more satisfaction with their lives.

Yet short-termism is not only psychological, it’s institutional. Richard Slaughter wrote as far back as 1996 that modern systems “reinforce the minimal present,” turning long-term vision into an act of rebellion.

We live inside a runaway present, where choice shrinks to the next minute. This narrowing empties out meaning, isolates us from continuity and robs life of the depth that a 16th-century stonemason enjoyed.

When we stretch time

Research shows that reaching beyond today is the ultimate act of self-care. Studies in temporal expansion reveal that imagining distant futures can reshape our identity, decrease stress, and strengthen our sense of purpose. One 2022 experiment found that asking participants to picture their lives from future vantage points made their goals more ambitious, compassionate and vivid.

The emotion of awe has similar effects. Dacher Keltner’s research at Berkeley shows that awe slows our perception of time, expands our sense of self and makes us more generous. Standing beneath an ancient oak or gazing at a mountain not only makes us feel small, but it also connects us to a timeline that transcends the self.

As a stonemason's daughter, I feel this deep connection to time when contemplating the Egyptian pyramids, Stonehenge, Göbekli Tepe, and Mohenjo-daro. Even walking my commute past the White Tower in London (constructed by William the Conqueror) can flip me into a deep time contemplation. I think about the builders who worked through generations on these monuments, for the sake of generations to come.

Moral philosophers have long understood the benefit of this ‘cathedral thinking’. Hilary Greaves and William MacAskill, in The Moral Case for Long-Term Thinking (2021), argue that the ethical weight of our choices does not decline with time. Distance in years should not lessen our responsibility to those who come after us.

Considering the selfish and short-termist obsession of much tech-culture, I love that computational models of cooperation show that societies which retain historical memory behave more altruistically than those that live only in the instant.

The longer our view, the kinder our behaviour.

The literature of long time

Storytellers have always understood what scientists are proving. In Ursula Le Guin’s The Dispossessed, the Anarresti build tunnels and institutions that outlast any lifetime so that each generation speaks in chorus with the past and future. Aldo Leopold’s essay Thinking Like a Mountain invites us to take the mountain’s view of time, to see human events as flickers within a vast ecology.

Roman Krznaric’s The Good Ancestor argues that every decision should be weighed by how it will be remembered, not how it will be rewarded. “Our descendants,” he writes, “depend on our ability to look beyond the immediate.”

Literature, philosophy and ecology all converge on the same truth: the long view is the human view.

Joy in the long now

People often assume that thinking far ahead must be gloomy. Too many people now envision apocalyptic timelines of melting ice and societal collapse.

But I am a stonemason’s daughter. I know that humans can build things of beauty and utility that will long outlast the names of those doing the building.

When we see ourselves as part of a long continuum, joy appears almost inevitably. Knowing that our actions ripple through generations grants meaning to the smallest gesture. Turning off a light becomes a love letter to the future. Writing a book or planting a tree becomes an act of devotion to people we will never meet.

Long-term thinking is also an antidote to anxiety.

When we place our lives within centuries rather than seasons, the petty urgency of the moment loses its grip. The inbox still fills, but it no longer defines existence. Purpose crystallises. Our days acquire an axis, and we join a human chain that stretches across time.

How to live the long now

You do not need to build a clock that ticks for ten thousand years to practise this.

Try writing a letter to someone who will be alive in the year 2300. Describe their sky, their challenges and their hopes. Do not predict, simply imagine with affection.

Spend time with something older than you: a tree, a cathedral, a fossil. Let it teach you patience. Read diaries from centuries past and feel the continuity of human worries and joys. Set a goal that must long outlive you. Speak about the future as though it is listening.

The pitfalls of the far view

Of course, long-term thinking isn’t entirely free from danger. Michelle Bastian warns of chronowashing, where invoking “future generations” becomes a way to justify delay or disguise inequality.

Also, beware of paralysis by scale, when the immensity of time overwhelms your ability to act. Not all futures are equally imagined; we must be alert to whose centuries are being centred. It’s not lost on me how many of the grand monuments of the past were also symbols of hierarchy and imperialism.

Some of the messages my dad found on the back of those stones aren’t of joy, but of grief. Because the long arc of history contains everything.

The long arc as a home

Living within the long now is not an escape from urgency. It is an embrace of continuity. It’s also why I still love the term' sustainability,' because it embodies that sense of long-termism within it.

When we expand our sense of time, we rediscover our place in the great unfolding of life. We become cathedral builders.

August 5, 2025

We're Living Through A Death Flowering

Does the world (metaphorically) smell faintly fetid right now? You’re trying to go about life, find joy, do the right thing. But that scent persists, like something, somewhere is rotten. You look around the world and the wrong things are growing.

It’s called the death flowering.

Years ago, the arborist and environmentalist Sir Tim Smit told me about epicormic growth.

When a tree is dying, hollowed by disease or stress, it can respond with an explosion of mismatched blossoms and confused fruit. For a moment, it appears more alive than ever. But this is not resurgence, it’s the last convulsion of life before death. The tree, sensing its end, throws all remaining energy into reproduction, hoping to pass on its genetic code before collapse.

This phenomenon has an unsettling parallel in human society.

I believe we are witnessing the cultural equivalent of a death flowering. Old political, economic, and social systems based on domination, extraction, and hierarchy are entering terminal decline. But before they collapse, they are erupting into spectacular excess.

History teaches us that systems rarely go quietly. The Roman Empire, in its twilight centuries, did not shrink with dignity. It indulged in ever more lavish spectacles and increasingly brutal crackdowns. The French monarchy before 1789 clung to court rituals of decadence while famine spread. In every case, the dominant class believed they were asserting control, when in fact they were exhausting their last reserves.

Which brings us back to today. The rise of authoritarian nostalgia, the hysterical backlash against feminism, the belligerent denial of ecological limits, these are symptoms of decay.

The fossil fuel economy is a death flower. It’s not embarking on a bold new chapter, it’s desperately attempting to outlive its relevance. Fundamentalist, misogynistic, and ethnonationalist ideologies are death flowers.

We should not mistake this for a renaissance. The flowers are blooming, but only because the rot beneath them has reached the core.

What happens next depends on whether humanity understands this moment not as a regressive resurgence, but as a requiem.

As Tim Smit told me: sometimes you’ve got to fetch your axe.

The falling limbs and infectious spores of a diseased tree threaten the surrounding life of the forest. To preserve the ecosystem, foresters must remove the tree before it falls.

We must become cultural foresters.

This does not mean violent revolution. It means recognising when a structure no longer serves its function. It means choosing conscious transformation over catastrophic collapse.

The tree will fall. The question is whether we will be crushed beneath it or guide it to the ground.

The ancient mythologies of humankind contain a deep awareness of this cycle. From the Egyptian Osiris to the Hindu Kali to the Mayan Popol Vuh, death is not only an end, it is a clearing for the new. Many belief systems treat destruction as the necessary precondition for creation.

In ecological terms, the fall of a large tree is a moment of opportunity. It opens the canopy, releases nutrients into the soil, and allows young saplings access to light.

Rather than clinging to the decaying giants of the 20th century of endless growth, fossil capitalism, and patriarchal dominance, we can nourish the new shoots of cooperation, regeneration, and ecological sanity. These shoots are already growing: in circular economies, in feminist leadership, in Indigenous knowledge systems, in renewable technologies.

We must clear the death flowers for the green shoots to grow.

That requires not only political and economic change, but a transformation in our cultural narrative. As long as humans see the death flowers as signs of vitality, they will remain entranced by spectacle and oblivious to decay. But if we learn to read the forest correctly, we will see what the flowers are really telling us: this world is ending.

This is an evolutionary moment.

History is a forest.

July 20, 2025

The Terror Of Being Seen

Ever so often, someone will thank me for being so open or honest about my work, my feelings, my observations.

And I freeze in abject terror.

It’s always said with gratitude and even a little vulnerability (giving compliments is never easy). The person thanking me is doing so for a reason, and because they wish more people would be vulnerable and ‘real’ about their journey. Perhaps it’s something I wrote about sustainability, or autism, or storytelling They resonated with whatever I said because I shared my truth, even if that sometimes puts me in an unflattering light (as truths are wont to do).

That openness allowed them to connect, to feel relief at not being alone, to feel seen themselves. Sounds pretty good, eh? Clearly, I should bask in the warm glow of the connection and impact I’ve made.

But in that moment, I usually want to hide under the table. Sometimes, if more than one person tells me the same thing at a single event, I DO go and hide in the loos until I gather myself.

Why?

Because being seen, truly seen, is bloody terrifying.

I only manage to do it because even if I’m standing in front of an audience, or sharing with thousands of followers, I convince myself no one is listening.

We’re told that vulnerability is brave, that authenticity is magnetic, that our raw truths are what the world needs. And that’s all… correct. But it can be almost unbearable.

Why We Fear Being SeenPsychologists call it the ‘exposure effect’, but not the kind that makes people like something more the more they encounter it. I mean the visceral sense of exposure that comes with saying something that matters, posting something personal, or publishing something that came from deep inside your soul.

It’s the moment after clicking ‘publish’ or saying something more open than intended on stage - when your heart manages to go quantum by dropping into your stomach and soaring into the air at the same time. You feel it when a friend says ‘I loved what you wrote about…’ and you immediately want to deflect or diminish. You feel it when the thing that’s most you is out there, and suddenly you wish you’d worn armour instead.

Neuroscientist Brené Brown has called this a ‘vulnerability hangover.’ That raw, post-reveal shame spiral that screams: Why did I do that? What if they misunderstand me? What if they don’t like me? What if they do?

In our age of curated perfection and algorithmic outrage, being honest feels dangerous. Not just because of trolls or judgment (though they’re real, I have a few), but because it asks us to sit with the truth that we are uncertain, unfinished, and a little messy.

It’s Almost Impossible……and yet.

I’ve come to believe that this terror of being seen is the gateway to genuine connection, and in our climate of confusion, it may be the only compass worth following.

The people who have helped me most in life were not the ones who had the slick answers or polished personas. They were the ones who said ‘I don’t know either,’ or ‘Yep, I suck at that too’.

Especially in sustainability, literally NO ONE has the definitive answer. We are all seeking spots of light in the growing darkness.

I write posts like Fighting Monsters When You’re Tired not because I want to be inspirational, but because I was bloody exhausted, and didn’t want to pretend otherwise. And the responses I received made it clear: we are all walking through fire in our own way, and honesty doesn’t add to the flames. It lights a path.

Fiction Is Worse (So Better)It amuses me now that I thought fiction would be easier, because I’m making it up. When I started writing Godstorm, my upcoming novel, I thought I was building a mythic world about petrol-worship, doomed empires, and climate change.

But the real storm was inside the characters.

One of my protagonists, a governess forced to protect a child in a collapsing regime, spends much of the story hiding how she really feels. She believes her strength lies in secrecy and strength. But the turning point comes not when she defeats her enemies, but when she lets someone see her.

It’s that act of being seen, truly seen, that saves her.

Because fiction lets us live vicariously through vulnerability. It lets us love people we’d never meet and feel things we’d never admit.

The Gift Of GlareThere is power in telling your story before it's wrapped up with a bow. Before you’ve succeeded or survived. While you’re still in the middle, confused and healing.

That kind of truth gives others permission. Even if that’s the permission to say thank you (because of course, deep down, those people who thank me are the ones who actually keep me going!)

And if there's one lesson I hope Godstorm carries, and one I try to live in these essays, it's this:

The world doesn’t need our perfection. It needs our perseverance.

Especially now, when everything around us urges cynicism and silence.

Just A Little More BraveryYes, I will probably still internally flinch the next time someone thanks me for being honest. But I will also smile, and maybe even hug. Because maybe my panic attack helped someone else breathe a little easier.

So if you are wondering whether to say the thing, write the thing, share the thing that truly matters to you, know this:

You might want to hide. But someone else out there is holding their breath, waiting for someone (anyone) to go first.

Let them see you.

Because that’s how the good stories start.

…………………………………………….

Want to read Godstorm, six months before anyone else?I’m recruiting a ‘launch team’ of volunteers to help promote my debut novel Godstorm. Join us, and you’ll get a free e-book copy of the novel to review (before anyone else), as well as all the gossip and goodies. To sign up, click here (UK only)

July 6, 2025

The Villain In The Mirror: What Fictional Bad Guys Can Teach Us About Real Ones

When I started writing my novel Godstorm, I assumed villains would be the easy part. Especially when writing climate fiction, the bad guys would be easy: they are literally destroying the world!

Give them a haughty sense of entitlement or venial obsession with their own selfish desires, and send them off to do their worst.

I was wrong…for a fascinating (and helpful) reason.

Writing believable ‘antagonists’ is one of the greatest challenges in fiction. Because the only way to make a bad guy or girl work on the page is to make them think they’re the good guy.

Villains, the compelling ones at least, never think of themselves as evil, or even misguided. They believe they’re principled, justified, visionary, and at worst, misunderstood. They must truly believe that they’re fixing the world, not breaking it. They’re not trying to be the problem. In fact, they’re certain they’re the solution.

Sound familiar?

In fiction, this is a necessary technique. In the real world, it’s a trap. And when it comes to climate change, it’s one we fall into again and again.

Everyone Is The Hero Of Their Own StoryWhen I wrote Godstorm, I found myself drawn into the back story of my antagonist. He is ruthless, yes. Manipulative, certainly. But he isn’t wrong in the head. He has a very clear logic, deep values, and a burning sense of purpose.

To write him convincingly, I had to believe him. I had to put down my moral high ground and step inside his motivations.

It was a little unsettling. And strangely familiar.

Because quite a lot of my career has been an attempt to communicate with people who are making terrible choices (for our health and our planet). And I learnt a long time ago that I wouldn’t get far telling them they’re terrible. Try that and they’ll stop listening. Because they know they’re not.

This is especially true in climate communications. The oil executive, the consumer flying first class, the policymaker kicking the carbon can down the road, they all have a mental construct in which they are the hero. Maybe they’re providing energy security. Maybe they’re keeping their family safe. Maybe they’re boosting GDP, or preserving jobs, or saving up for their child’s future.

They don’t see themselves as the villain. And if you tell them they are, you don’t make them rethink. You make yourself the villain in their story.

The Mirror Test: Why Blame BackfiresThere’s a cognitive truth at play here. Humans have a powerful bias toward moral self-coherence. We need to see ourselves as good, even when our actions suggest otherwise. This is supported by work in moral psychology: researchers like Jonathan Haidt (author of the excellent book The Righteous Mind) show that people intuitively justify their behaviour and then rationalise it after the fact, especially when their identity is at stake.

If something threatens that self-perception, we defend, deflect, or disbelieve. Psychologists call this identity-protective cognition: a bias where people reject information that threatens their group or personal identity, even if it’s factual.

Our brains literally won’t let you accept that we’re the bad guy.

That’s why shame-based messaging almost always fails in climate action. A study by Feinberg and Willer found that messages focused on doom and guilt reduced support for environmental policies. Another by Moser and Dilling confirmed that fear-based climate communication often leads to denial or disengagement unless paired with hope and efficacy.

Accusations trigger our mental armour. Labels of ‘climate criminal’ or ‘denier’ might feel cathartic, but they rarely change minds and can instead entrench identities.

Fiction follows the psychological rule that everyone looks in the mirror and sees a hero.

Telling Better Stories: Reframing Climate HeroesSo what do we do instead?

We write better stories. We expand the narrative frame so that people can see themselves as climate heroes, without having to change their entire identity or admit their sins. We give them the role of the problem-solver, the innovator, the protector, or the wise ancestor. We don’t make them the enemy. We make them the main character in a different story where climate action is aligned with who they already believe they are.

The great lesson of writing villains is that empathy is the ultimate tool of understanding. When you walk in your antagonist’s shoes, you learn what moves them. And once you know that, you can write the moment they choose redemption, or refuse it.

In climate storytelling, that turning point matters more than anything. Because the story isn’t over yet. We’re still in the rising action. The climax is coming, and every character matters. Even the ones you think are on the wrong side.

So next time you sit down to write, speak, or campaign, ask yourself this: who do they believe they are? What’s their story?

Because until you can answer that, you’ll never be able to change the ending.

…………………………………………….

In other news:I’m recruiting a ‘launch team’ of volunteers to help promote my debut novel Godstorm. Sign up, and you’ll get a free e-book copy of the novel to review (before anyone else), as well as all the gossip and goodies. To sign up, click here.