Elizabeth Mitchell's Blog

February 11, 2020

Hello world!

Welcome to WordPress. This is your first post. Edit or delete it, then start writing!

February 10, 2020

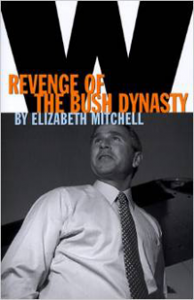

W: Revenge of the Bush Dynasty

{“main-title”:{“component”:”hc_title”,”id”:”main-title”,”title”:””,”subtitle”:””,”title_content”:{“component”:”hc_title_empty”,”id”:”title-empty”}},”section_5ZtkF”:{“component”:”hc_section”,”id”:”section_5ZtkF”,”section_width”:””,”animation”:””,”animation_time”:””,”timeline_animation”:””,”timeline_delay”:””,”timeline_order”:””,”vertical_row”:””,”box_middle”:””,”css_classes”:””,”custom_css_classes”:””,”custom_css_styles”:””,”section_content”:[{“component”:”hc_column”,”id”:”column_vtfQF”,”column_width”:”col-md-12″,”animation”:”fade-in”,”animation_time”:””,”timeline_animation”:”false”,”timeline_delay”:””,”timeline_order”:””,”css_classes”:””,”custom_css_classes”:””,”custom_css_styles”:””,”main_content”:[{“component”:”hc_pt_post_informations”,”id”:”SCjkR”,”css_classes”:””,”custom_css_classes”:”pageHead”,”custom_css_styles”:””,”post_type_slug”:””,”position”:”left”,”date”:false,”categories”:true,”author”:false,”share”:false},{“component”:”hc_title_tag”,”id”:”5ZtkF”,”css_classes”:””,”custom_css_classes”:””,”custom_css_styles”:””,”text”:”W: Revenge of the Bush Dynasty”,”tag”:”h1″},{“component”:”hc_title_tag”,”id”:”DI5Sx”,”css_classes”:””,”custom_css_classes”:”publicationTitle”,”custom_css_styles”:””,”text”:”Hyperion”,”tag”:”h3″},{“component”:”hc_title_tag”,”id”:”UTyhl”,”css_classes”:””,”custom_css_classes”:”publicationDate”,”custom_css_styles”:””,”text”:”January 25, 2000″,”tag”:”h6″},{“component”:”hc_wp_editor”,”id”:”Xhugf”,”css_classes”:””,”custom_css_classes”:””,”custom_css_styles”:””,”editor_content”:” “A telling book.” – Chicago Tribune\n\n“Anyone seeking insight into George W. before his final chapter is written will find much to ponder in Mitchell’s presentation.” – Publisher’s Weekly\n\n“Lucid…recommended.” – Library Journal\n\n“Follows George W.’s relentless path toward re-creating his dad’s achievements, from Andover to Yale to the oil patch to politics to his presidential run…. well-reported” – The New York Times Book Review\n\n“Valuable… recount[s] his early life in the oil country of West Texas.” – The Leaf-Chronicle (Clarksville, TN)”},{“component”:”hc_text_block”,”id”:”27BUN”,”css_classes”:””,”custom_css_classes”:””,”custom_css_styles”:””,”content”:”Read more and order the book: “},{“component”:”hc_button”,”id”:”iHeSs”,”css_classes”:””,”custom_css_classes”:””,”custom_css_styles”:””,”icon”:””,”style”:”circle”,”size”:””,”position”:”left”,”animation”:false,”text”:”Read more and order the book: “,”link_type”:”classic”,”lightbox_animation”:””,”caption”:””,”inner_caption”:false,”new_window”:false,”link”:”https://www.amazon.com/dp/0786866306/...””}}}}

“A telling book.” – Chicago Tribune\n\n“Anyone seeking insight into George W. before his final chapter is written will find much to ponder in Mitchell’s presentation.” – Publisher’s Weekly\n\n“Lucid…recommended.” – Library Journal\n\n“Follows George W.’s relentless path toward re-creating his dad’s achievements, from Andover to Yale to the oil patch to politics to his presidential run…. well-reported” – The New York Times Book Review\n\n“Valuable… recount[s] his early life in the oil country of West Texas.” – The Leaf-Chronicle (Clarksville, TN)”},{“component”:”hc_text_block”,”id”:”27BUN”,”css_classes”:””,”custom_css_classes”:””,”custom_css_styles”:””,”content”:”Read more and order the book: “},{“component”:”hc_button”,”id”:”iHeSs”,”css_classes”:””,”custom_css_classes”:””,”custom_css_styles”:””,”icon”:””,”style”:”circle”,”size”:””,”position”:”left”,”animation”:false,”text”:”Read more and order the book: “,”link_type”:”classic”,”lightbox_animation”:””,”caption”:””,”inner_caption”:false,”new_window”:false,”link”:”https://www.amazon.com/dp/0786866306/...””}}}}

February 5, 2020

Anita Hill’s Afterlife

{“main-title”:{“component”:”hc_title”,”id”:”main-title”,”title”:””,”subtitle”:””,”title_content”:{“component”:”hc_title_empty”,”id”:”title-empty”}},”section_5ZtkF”:{“component”:”hc_section”,”id”:”section_5ZtkF”,”section_width”:””,”animation”:””,”animation_time”:””,”timeline_animation”:””,”timeline_delay”:””,”timeline_order”:””,”vertical_row”:””,”box_middle”:””,”css_classes”:””,”custom_css_classes”:””,”custom_css_styles”:””,”section_content”:[{“component”:”hc_column”,”id”:”column_vtfQF”,”column_width”:”col-md-12″,”animation”:”fade-in”,”animation_time”:””,”timeline_animation”:”false”,”timeline_delay”:””,”timeline_order”:””,”css_classes”:””,”custom_css_classes”:””,”custom_css_styles”:””,”main_content”:[{“component”:”hc_pt_post_informations”,”id”:”SCjkR”,”css_classes”:””,”custom_css_classes”:”pageHead”,”custom_css_styles”:””,”post_type_slug”:””,”position”:”left”,”date”:false,”categories”:true,”author”:false,”share”:false},{“component”:”hc_title_tag”,”id”:”5ZtkF”,”css_classes”:””,”custom_css_classes”:””,”custom_css_styles”:””,”text”:”Anita Hill’s Afterlife”,”tag”:”h1″},{“component”:”hc_title_tag”,”id”:”DI5Sx”,”css_classes”:””,”custom_css_classes”:”publicationTitle”,”custom_css_styles”:””,”text”:”O Magazine”,”tag”:”h3″},{“component”:”hc_title_tag”,”id”:”UTyhl”,”css_classes”:””,”custom_css_classes”:”publicationDate”,”custom_css_styles”:””,”text”:”July 2005″,”tag”:”h6″},{“component”:”hc_wp_editor”,”id”:”Xhugf”,”css_classes”:””,”custom_css_classes”:””,”custom_css_styles”:””,”editor_content”:” As a teenager in Oklahoma, Anita Hill showed uncanny prescience in choosing a hero for the life that awaited her: Barbara Jordan, the outspoken 38-year-old congresswoman who captivated the nation when she forcefully defended the constitution during Richard Nixon’s impeachment proceedings. “I was watching the Watergate hearings, and I thought, This is the bravest woman—and she’s from Texas? Next door to me? This black woman is out there, and she’s a star in these hearings. She’s sitting with all these guys, and she’s definitely not a shrinking violet.” The image worked for Hill, Suddenly, she could envision how “you could be in the kind of skin that I was in, maybe even come from the same background, and make an impact on the world.””},{“component”:”hc_button”,”id”:”PGN6v”,”css_classes”:””,”custom_css_classes”:”moreLink”,”custom_css_styles”:””,”icon”:””,”style”:”link”,”size”:””,”position”:”left”,”animation”:false,”text”:”Read more »”,”link_type”:”classic”,”lightbox_animation”:””,”caption”:””,”inner_caption”:false,”new_window”:false,”link”:”https://web.archive.org/web/201101222... hide”,”custom_css_styles”:””,”main_content”:[{“component”:”hc_column”,”id”:”column_fsOTS”,”column_width”:”col-md-2″,”animation”:””,”animation_time”:””,”timeline_animation”:””,”timeline_delay”:””,”timeline_order”:””,”css_classes”:””,”custom_css_classes”:””,”custom_css_styles”:””,”main_content”:[{“component”:”hc_adv_image_box”,”id”:”d3cOz”,”css_classes”:””,”custom_css_classes”:””,”custom_css_styles”:””,”image”:””,”icon”:””,”title”:””,”box_style”:”full_content”,”image_animation”:””,”hidden_content”:false,”thumb_size”:”large”,”button_text”:””,”button_style”:”link”,”button_dimensions”:””,”button_animation”:false,”extra_text”:””,”subtitle”:””,”text”:””,”link_type”:”classic”,”lightbox_animation”:””,”caption”:””,”inner_caption”:false,”new_window”:true,”link”:””,”link_content”:[],”lightbox_size”:””,”scrollbox”:false},{“component”:”hc_adv_image_box”,”id”:”YcyWS”,”css_classes”:””,”custom_css_classes”:””,”custom_css_styles”:””,”image”:””,”icon”:””,”title”:””,”box_style”:”full_content”,”image_animation”:””,”hidden_content”:false,”thumb_size”:”large”,”button_text”:””,”button_style”:”link”,”button_dimensions”:””,”button_animation”:false,”extra_text”:””,”subtitle”:””,”text”:””,”link_type”:”classic”,”lightbox_animation”:””,”caption”:””,”inner_caption”:false,”new_window”:true,”link”:””,”link_content”:[],”lightbox_size”:””,”scrollbox”:false}]},{“component”:”hc_column”,”id”:”column_wp4oc”,”column_width”:”col-md-2″,”animation”:””,”animation_time”:””,”timeline_animation”:””,”timeline_delay”:””,”timeline_order”:””,”css_classes”:””,”custom_css_classes”:””,”custom_css_styles”:””,”main_content”:[{“component”:”hc_adv_image_box”,”id”:”5icYb”,”css_classes”:””,”custom_css_classes”:””,”custom_css_styles”:””,”image”:””,”icon”:””,”title”:””,”box_style”:”full_content”,”image_animation”:””,”hidden_content”:false,”thumb_size”:”large”,”button_text”:””,”button_style”:”link”,”button_dimensions”:””,”button_animation”:false,”extra_text”:””,”subtitle”:””,”text”:””,”link_type”:”classic”,”lightbox_animation”:””,”caption”:””,”inner_caption”:false,”new_window”:true,”link”:””,”link_content”:[],”lightbox_size”:””,”scrollbox”:false}]},{“component”:”hc_column”,”id”:”column_NpKeO”,”column_width”:”col-md-2″,”animation”:””,”animation_time”:””,”timeline_animation”:””,”timeline_delay”:””,”timeline_order”:””,”css_classes”:””,”custom_css_classes”:””,”custom_css_styles”:””,”main_content”:[{“component”:”hc_adv_image_box”,”id”:”ab176″,”css_classes”:””,”custom_css_classes”:””,”custom_css_styles”:””,”image”:””,”icon”:””,”title”:””,”box_style”:”full_content”,”image_animation”:””,”hidden_content”:false,”thumb_size”:”large”,”button_text”:””,”button_style”:”link”,”button_dimensions”:””,”button_animation”:false,”extra_text”:””,”subtitle”:””,”text”:””,”link_type”:”classic”,”lightbox_animation”:””,”caption”:””,”inner_caption”:false,”new_window”:true,”link”:””,”link_content”:[],”lightbox_size”:””,”scrollbox”:false}]}]}],”section_settings”:””},”column_EkNvV”:{“id”:”column_EkNvV”,”main_content”:{“component”:”hc_adv_image_box”,”id”:”YcyWS”,”css_classes”:””,”custom_css_classes”:””,”custom_css_styles”:””,”image”:””,”icon”:””,”title”:””,”box_style”:”full_content”,”image_animation”:””,”hidden_content”:false,”thumb_size”:”large”,”button_text”:””,”button_style”:”link”,”button_dimensions”:””,”button_animation”:false,”extra_text”:””,”subtitle”:””,”text”:””,”link_type”:”classic”,”lightbox_animation”:””,”caption”:””,”inner_caption”:false,”new_window”:true,”link”:””,”link_content”:[],”lightbox_size”:””,”scrollbox”:false}},”scripts”:{“lightbox”:”jquery.magnific-popup.min.js”},”css”:{“lightbox”:”scripts/magnific-popup.css”,”image_box”:”css/image-box.css”},”css_page”:””,”template_setting”:{“settings”:{“id”:”settings”}},”template_setting_top”:{},”page_setting”:{“settings”:[“lock-mode-off”]},”post_type_setting”:{“settings”:{“image”:””,”excerpt”:”[image error] As a teenager in Oklahoma, Anita Hill showed uncanny prescience in choosing a hero for the life that awaited her: Barbara Jordan, the outspoken 38-year-old congresswoman who captivated the nation when she forcefully defended the constitution during Richard Nixon’s impeachment proceedings. “I was watching the Watergate hearings, and I thought, This is the bravest woman—and she’s from Texas? Next door to me? This black woman is out there, and she’s a star in these hearings. She’s sitting with all these guys, and she’s definitely not a shrinking violet.” The image worked for Hill, Suddenly, she could envision how “you could be in the kind of skin that I was in, maybe even come from the same background, and make an impact on the world.””,”extra_1″:””,”extra_2″:””,”icon”:{“icon”:””,”icon_style”:””,”icon_image”:””}}}}

As a teenager in Oklahoma, Anita Hill showed uncanny prescience in choosing a hero for the life that awaited her: Barbara Jordan, the outspoken 38-year-old congresswoman who captivated the nation when she forcefully defended the constitution during Richard Nixon’s impeachment proceedings. “I was watching the Watergate hearings, and I thought, This is the bravest woman—and she’s from Texas? Next door to me? This black woman is out there, and she’s a star in these hearings. She’s sitting with all these guys, and she’s definitely not a shrinking violet.” The image worked for Hill, Suddenly, she could envision how “you could be in the kind of skin that I was in, maybe even come from the same background, and make an impact on the world.””},{“component”:”hc_button”,”id”:”PGN6v”,”css_classes”:””,”custom_css_classes”:”moreLink”,”custom_css_styles”:””,”icon”:””,”style”:”link”,”size”:””,”position”:”left”,”animation”:false,”text”:”Read more »”,”link_type”:”classic”,”lightbox_animation”:””,”caption”:””,”inner_caption”:false,”new_window”:false,”link”:”https://web.archive.org/web/201101222... hide”,”custom_css_styles”:””,”main_content”:[{“component”:”hc_column”,”id”:”column_fsOTS”,”column_width”:”col-md-2″,”animation”:””,”animation_time”:””,”timeline_animation”:””,”timeline_delay”:””,”timeline_order”:””,”css_classes”:””,”custom_css_classes”:””,”custom_css_styles”:””,”main_content”:[{“component”:”hc_adv_image_box”,”id”:”d3cOz”,”css_classes”:””,”custom_css_classes”:””,”custom_css_styles”:””,”image”:””,”icon”:””,”title”:””,”box_style”:”full_content”,”image_animation”:””,”hidden_content”:false,”thumb_size”:”large”,”button_text”:””,”button_style”:”link”,”button_dimensions”:””,”button_animation”:false,”extra_text”:””,”subtitle”:””,”text”:””,”link_type”:”classic”,”lightbox_animation”:””,”caption”:””,”inner_caption”:false,”new_window”:true,”link”:””,”link_content”:[],”lightbox_size”:””,”scrollbox”:false},{“component”:”hc_adv_image_box”,”id”:”YcyWS”,”css_classes”:””,”custom_css_classes”:””,”custom_css_styles”:””,”image”:””,”icon”:””,”title”:””,”box_style”:”full_content”,”image_animation”:””,”hidden_content”:false,”thumb_size”:”large”,”button_text”:””,”button_style”:”link”,”button_dimensions”:””,”button_animation”:false,”extra_text”:””,”subtitle”:””,”text”:””,”link_type”:”classic”,”lightbox_animation”:””,”caption”:””,”inner_caption”:false,”new_window”:true,”link”:””,”link_content”:[],”lightbox_size”:””,”scrollbox”:false}]},{“component”:”hc_column”,”id”:”column_wp4oc”,”column_width”:”col-md-2″,”animation”:””,”animation_time”:””,”timeline_animation”:””,”timeline_delay”:””,”timeline_order”:””,”css_classes”:””,”custom_css_classes”:””,”custom_css_styles”:””,”main_content”:[{“component”:”hc_adv_image_box”,”id”:”5icYb”,”css_classes”:””,”custom_css_classes”:””,”custom_css_styles”:””,”image”:””,”icon”:””,”title”:””,”box_style”:”full_content”,”image_animation”:””,”hidden_content”:false,”thumb_size”:”large”,”button_text”:””,”button_style”:”link”,”button_dimensions”:””,”button_animation”:false,”extra_text”:””,”subtitle”:””,”text”:””,”link_type”:”classic”,”lightbox_animation”:””,”caption”:””,”inner_caption”:false,”new_window”:true,”link”:””,”link_content”:[],”lightbox_size”:””,”scrollbox”:false}]},{“component”:”hc_column”,”id”:”column_NpKeO”,”column_width”:”col-md-2″,”animation”:””,”animation_time”:””,”timeline_animation”:””,”timeline_delay”:””,”timeline_order”:””,”css_classes”:””,”custom_css_classes”:””,”custom_css_styles”:””,”main_content”:[{“component”:”hc_adv_image_box”,”id”:”ab176″,”css_classes”:””,”custom_css_classes”:””,”custom_css_styles”:””,”image”:””,”icon”:””,”title”:””,”box_style”:”full_content”,”image_animation”:””,”hidden_content”:false,”thumb_size”:”large”,”button_text”:””,”button_style”:”link”,”button_dimensions”:””,”button_animation”:false,”extra_text”:””,”subtitle”:””,”text”:””,”link_type”:”classic”,”lightbox_animation”:””,”caption”:””,”inner_caption”:false,”new_window”:true,”link”:””,”link_content”:[],”lightbox_size”:””,”scrollbox”:false}]}]}],”section_settings”:””},”column_EkNvV”:{“id”:”column_EkNvV”,”main_content”:{“component”:”hc_adv_image_box”,”id”:”YcyWS”,”css_classes”:””,”custom_css_classes”:””,”custom_css_styles”:””,”image”:””,”icon”:””,”title”:””,”box_style”:”full_content”,”image_animation”:””,”hidden_content”:false,”thumb_size”:”large”,”button_text”:””,”button_style”:”link”,”button_dimensions”:””,”button_animation”:false,”extra_text”:””,”subtitle”:””,”text”:””,”link_type”:”classic”,”lightbox_animation”:””,”caption”:””,”inner_caption”:false,”new_window”:true,”link”:””,”link_content”:[],”lightbox_size”:””,”scrollbox”:false}},”scripts”:{“lightbox”:”jquery.magnific-popup.min.js”},”css”:{“lightbox”:”scripts/magnific-popup.css”,”image_box”:”css/image-box.css”},”css_page”:””,”template_setting”:{“settings”:{“id”:”settings”}},”template_setting_top”:{},”page_setting”:{“settings”:[“lock-mode-off”]},”post_type_setting”:{“settings”:{“image”:””,”excerpt”:”[image error] As a teenager in Oklahoma, Anita Hill showed uncanny prescience in choosing a hero for the life that awaited her: Barbara Jordan, the outspoken 38-year-old congresswoman who captivated the nation when she forcefully defended the constitution during Richard Nixon’s impeachment proceedings. “I was watching the Watergate hearings, and I thought, This is the bravest woman—and she’s from Texas? Next door to me? This black woman is out there, and she’s a star in these hearings. She’s sitting with all these guys, and she’s definitely not a shrinking violet.” The image worked for Hill, Suddenly, she could envision how “you could be in the kind of skin that I was in, maybe even come from the same background, and make an impact on the world.””,”extra_1″:””,”extra_2″:””,”icon”:{“icon”:””,”icon_style”:””,”icon_image”:””}}}}

The Fearless Mrs. Goodwin: How New York’s First Female Police Detective Cracked the Crime of the Century

{“main-title”:{“component”:”hc_title”,”id”:”main-title”,”title”:””,”subtitle”:””,”title_content”:{“component”:”hc_title_empty”,”id”:”title-empty”}},”section_5ZtkF”:{“component”:”hc_section”,”id”:”section_5ZtkF”,”section_width”:””,”animation”:””,”animation_time”:””,”timeline_animation”:””,”timeline_delay”:””,”timeline_order”:””,”vertical_row”:””,”box_middle”:””,”css_classes”:””,”custom_css_classes”:””,”custom_css_styles”:””,”section_content”:[{“component”:”hc_column”,”id”:”column_vtfQF”,”column_width”:”col-md-12″,”animation”:”fade-in”,”animation_time”:””,”timeline_animation”:”false”,”timeline_delay”:””,”timeline_order”:””,”css_classes”:””,”custom_css_classes”:””,”custom_css_styles”:””,”main_content”:[{“component”:”hc_pt_post_informations”,”id”:”SCjkR”,”css_classes”:””,”custom_css_classes”:”pageHead”,”custom_css_styles”:””,”post_type_slug”:””,”position”:”left”,”date”:false,”categories”:true,”author”:false,”share”:false},{“component”:”hc_title_tag”,”id”:”5ZtkF”,”css_classes”:””,”custom_css_classes”:””,”custom_css_styles”:””,”text”:”The Fearless Mrs. Goodwin: How New York’s First Female Police Detective Cracked the Crime of the Century”,”tag”:”h1″},{“component”:”hc_title_tag”,”id”:”DI5Sx”,”css_classes”:””,”custom_css_classes”:”publicationTitle”,”custom_css_styles”:””,”text”:”Byliner”,”tag”:”h3″},{“component”:”hc_title_tag”,”id”:”UTyhl”,”css_classes”:””,”custom_css_classes”:”publicationDate”,”custom_css_styles”:””,”text”:”August 2011″,”tag”:”h6″},{“component”:”hc_wp_editor”,”id”:”Xhugf”,”css_classes”:””,”custom_css_classes”:””,”custom_css_styles”:””,”editor_content”:” \n\nON THE MORNING of February 15, 1912, a Thursday, George Schweitzer stepped out of his doorman’s office inside the French Renaissance lobby of America’s largest hotel, the Broadway Central, in New York City. The harsh winter sun was just slanting down East Third into Broadway, and hundreds of guests hurried in and out of the hotel’s doors. The massive American flags on each of the three Gothic towers hung slack against the winter sky.\n\nSchweitzer saw the taxicab driver, Geno Mantani, idling near his stand, still waiting for his employee Sam Lefkowitz to get back from uptown, where he was having a half dozen tires fixed.\n\n“Bank call. Go over there,” Schweitzer said, motioning to East River National, across the street.\n\nMantani got up on his box and set his machine into gear. He was an extremely lucky man. Between fifty and a hundred taxicab chauffeurs operated in the city, but he had been fortunate enough to contract for East River National’s business about a year before. That meant regular work….\n\nAt that point in New York’s history, the city was like a mark falling victim to the swindler’s graft, naive enough to hope for a metropolis that would contain its nearly five million citizens in peace, and canny enough to desire more—ever taller buildings, an infrastructure that might surpass the marvelous underground railroad that had been rattling beneath the town since 1904, and larger fortunes than even the Rockefellers could amass.\n\nThe years of brute crime in the city—the regular Five Points gang-style rioting, for instance—had passed back in the late 1800s. Banks might lose track of funds, but that was through the crisp forgery of a first-rate scratcher. Somehow the denizens of the metropolis believed that this island of Manhattan, and across the river the crystallizing Brooklyn fed by the Brooklyn, Manhattan, and Williamsburg bridges, could amass fortunes, house the downtrodden, hide away the Burney Blowers blasting cocaine up their noses through rubber hoses, and absorb those disparate lifestyles in relative tranquillity. While a wife might plunge a knife in her husband’s chest, or a jewelry store watch might get pinched, strangers for the most part would never harm strangers, institutions would never be touched by violence.”},{“component”:”hc_button”,”id”:”PGN6v”,”css_classes”:””,”custom_css_classes”:”moreLink”,”custom_css_styles”:””,”icon”:””,”style”:”link”,”size”:””,”position”:”left”,”animation”:false,”text”:””,”link_type”:”classic”,”lightbox_animation”:””,”caption”:””,”inner_caption”:false,”new_window”:false,”link”:””,”link_content”:[],”lightbox_size”:””,”scrollbox”:false}]},{“component”:”hc_column”,”id”:”column_4aGNN”,”column_width”:”col-md-12″,”animation”:””,”animation_time”:””,”timeline_animation”:””,”timeline_delay”:””,”timeline_order”:””,”css_classes”:””,”custom_css_classes”:”storeLinks”,”custom_css_styles”:””,”main_content”:[{“component”:”hc_column”,”id”:”column_NpKeO”,”column_width”:”col-md-2″,”animation”:””,”animation_time”:””,”timeline_animation”:””,”timeline_delay”:””,”timeline_order”:””,”css_classes”:””,”custom_css_classes”:””,”custom_css_styles”:””,”main_content”:[{“component”:”hc_adv_image_box”,”id”:”ab176″,”css_classes”:””,”custom_css_classes”:””,”custom_css_styles”:””,”image”:”https://elizabethmitchell.info/wp-con...”

\n\nON THE MORNING of February 15, 1912, a Thursday, George Schweitzer stepped out of his doorman’s office inside the French Renaissance lobby of America’s largest hotel, the Broadway Central, in New York City. The harsh winter sun was just slanting down East Third into Broadway, and hundreds of guests hurried in and out of the hotel’s doors. The massive American flags on each of the three Gothic towers hung slack against the winter sky.\n\nSchweitzer saw the taxicab driver, Geno Mantani, idling near his stand, still waiting for his employee Sam Lefkowitz to get back from uptown, where he was having a half dozen tires fixed.\n\n“Bank call. Go over there,” Schweitzer said, motioning to East River National, across the street.\n\nMantani got up on his box and set his machine into gear. He was an extremely lucky man. Between fifty and a hundred taxicab chauffeurs operated in the city, but he had been fortunate enough to contract for East River National’s business about a year before. That meant regular work….\n\nAt that point in New York’s history, the city was like a mark falling victim to the swindler’s graft, naive enough to hope for a metropolis that would contain its nearly five million citizens in peace, and canny enough to desire more—ever taller buildings, an infrastructure that might surpass the marvelous underground railroad that had been rattling beneath the town since 1904, and larger fortunes than even the Rockefellers could amass.\n\nThe years of brute crime in the city—the regular Five Points gang-style rioting, for instance—had passed back in the late 1800s. Banks might lose track of funds, but that was through the crisp forgery of a first-rate scratcher. Somehow the denizens of the metropolis believed that this island of Manhattan, and across the river the crystallizing Brooklyn fed by the Brooklyn, Manhattan, and Williamsburg bridges, could amass fortunes, house the downtrodden, hide away the Burney Blowers blasting cocaine up their noses through rubber hoses, and absorb those disparate lifestyles in relative tranquillity. While a wife might plunge a knife in her husband’s chest, or a jewelry store watch might get pinched, strangers for the most part would never harm strangers, institutions would never be touched by violence.”},{“component”:”hc_button”,”id”:”PGN6v”,”css_classes”:””,”custom_css_classes”:”moreLink”,”custom_css_styles”:””,”icon”:””,”style”:”link”,”size”:””,”position”:”left”,”animation”:false,”text”:””,”link_type”:”classic”,”lightbox_animation”:””,”caption”:””,”inner_caption”:false,”new_window”:false,”link”:””,”link_content”:[],”lightbox_size”:””,”scrollbox”:false}]},{“component”:”hc_column”,”id”:”column_4aGNN”,”column_width”:”col-md-12″,”animation”:””,”animation_time”:””,”timeline_animation”:””,”timeline_delay”:””,”timeline_order”:””,”css_classes”:””,”custom_css_classes”:”storeLinks”,”custom_css_styles”:””,”main_content”:[{“component”:”hc_column”,”id”:”column_NpKeO”,”column_width”:”col-md-2″,”animation”:””,”animation_time”:””,”timeline_animation”:””,”timeline_delay”:””,”timeline_order”:””,”css_classes”:””,”custom_css_classes”:””,”custom_css_styles”:””,”main_content”:[{“component”:”hc_adv_image_box”,”id”:”ab176″,”css_classes”:””,”custom_css_classes”:””,”custom_css_styles”:””,”image”:”https://elizabethmitchell.info/wp-con...” ON THE MORNING of February 15, 1912, a Thursday, George Schweitzer stepped out of his doorman’s office inside the French Renaissance lobby of America’s largest hotel, the Broadway Central, in New York City. The harsh winter sun was just slanting down East Third into Broadway, and hundreds of guests hurried in and out of the hotel’s doors. The massive American flags on each of the three Gothic towers hung slack against the winter sky.”,”extra_1″:””,”extra_2″:””,”icon”:{“icon”:””,”icon_style”:””,”icon_image”:””}}}}

ON THE MORNING of February 15, 1912, a Thursday, George Schweitzer stepped out of his doorman’s office inside the French Renaissance lobby of America’s largest hotel, the Broadway Central, in New York City. The harsh winter sun was just slanting down East Third into Broadway, and hundreds of guests hurried in and out of the hotel’s doors. The massive American flags on each of the three Gothic towers hung slack against the winter sky.”,”extra_1″:””,”extra_2″:””,”icon”:{“icon”:””,”icon_style”:””,”icon_image”:””}}}}

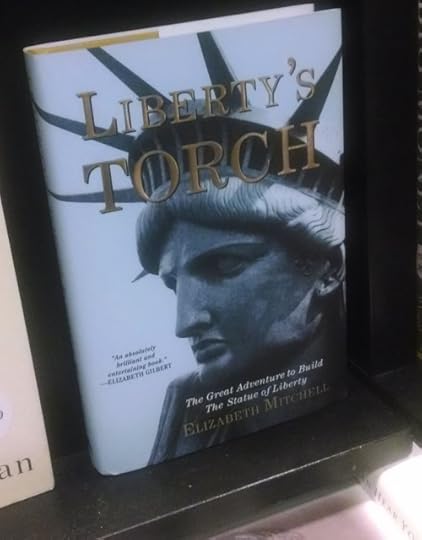

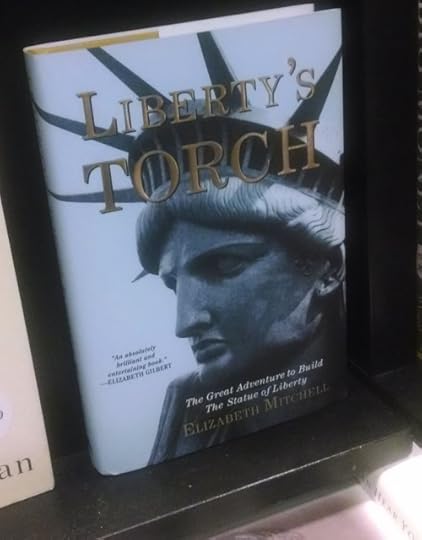

What they are saying about LIBERTY’S TORCH

{“main-title”:{“component”:”hc_title”,”id”:”main-title”,”title”:””,”subtitle”:””,”title_content”:{“component”:”hc_title_empty”,”id”:”title-empty”}},”section_5ZtkF”:{“component”:”hc_section”,”id”:”section_5ZtkF”,”section_width”:””,”animation”:””,”animation_time”:””,”timeline_animation”:””,”timeline_delay”:””,”timeline_order”:””,”vertical_row”:””,”box_middle”:””,”css_classes”:””,”custom_css_classes”:””,”custom_css_styles”:””,”section_content”:[{“component”:”hc_column”,”id”:”column_vtfQF”,”column_width”:”col-md-12″,”animation”:”fade-in”,”animation_time”:””,”timeline_animation”:”false”,”timeline_delay”:””,”timeline_order”:””,”css_classes”:””,”custom_css_classes”:””,”custom_css_styles”:””,”main_content”:[{“component”:”hc_pt_post_informations”,”id”:”SCjkR”,”css_classes”:””,”custom_css_classes”:”pageHead”,”custom_css_styles”:””,”post_type_slug”:””,”position”:”left”,”date”:false,”categories”:true,”author”:false,”share”:false},{“component”:”hc_title_tag”,”id”:”5ZtkF”,”css_classes”:””,”custom_css_classes”:””,”custom_css_styles”:””,”text”:”What they are saying about LIBERTY’S TORCH”,”tag”:”h1″},{“component”:”hc_title_tag”,”id”:”DI5Sx”,”css_classes”:””,”custom_css_classes”:”publicationTitle”,”custom_css_styles”:”display:none;”,”text”:”O Magazine”,”tag”:”h3″},{“component”:”hc_title_tag”,”id”:”UTyhl”,”css_classes”:””,”custom_css_classes”:”publicationDate”,”custom_css_styles”:”display:none;”,”text”:”October 2014″,”tag”:”h6″},{“component”:”hc_wp_editor”,”id”:”Xhugf”,”css_classes”:””,”custom_css_classes”:””,”custom_css_styles”:””,”editor_content”:” \n\nAn O Magazine 15 Titles to Pick Up Now Selection, Summer 2014\n\n“Journalist Elizabeth Mitchell recounts the captivating story behind the familiar monument that readers may have assumed they knew everything about.” — New York Times\n\n

\n\nAn O Magazine 15 Titles to Pick Up Now Selection, Summer 2014\n\n“Journalist Elizabeth Mitchell recounts the captivating story behind the familiar monument that readers may have assumed they knew everything about.” — New York Times\n\n “Liberty’s Torch reveals a statue with a storied past . . . Mitchell uses Liberty to reveal a pantheon of historic figures, including novelist Victor Hugo, engineer Gustave Eiffel and newspaper publisher Joseph Pulitzer. The drama—or “great adventure,” to borrow from the subtitle—runs from the Pyramids of Egypt to the backrooms of Congress. . . . By explaining Liberty’s tortured history and resurrecting Bartholdi’s indomitable spirit, Mitchell has done a great service. This is narrative history, well told. It is history that connects us to our past and—hopefully—to our future.”— Los Angeles Times\n\n“Streamlined and well constructed. . . . Proceeding chronologically, the author divides her story into three parts (“The Idea,” “The Gamble,” “The Triumph”) and opens with just the right amount of initial biographical detail on the designer, bolstering her portrait with further historical background as the narrative warrants. . . . deft strokes and always apt, telling details. . . . Mitchell successfully conveys the enormity of the undertaking and the infuriating amount of bureaucracy and old-fashioned glad-handing required to finish the job. . . . In Bartholdi, Mitchell has found a fascinating character through which to view late-19th-century America, and she does readers a service by sifting fact from fiction in the creation of one our most beloved monuments.” — Boston Globe\n\n“A myth-busting story starring the French sculptor Frédéric Auguste Bartholdi. Mitchell’s adjectives for him include crazy, driven, peevish and obnoxious. He rarely missed an opportunity to advance his own career, but Mitchell says he had “an incredible ability to soldier on” through a 15-year struggle. . . . Were it for not for Bartholdi, the statue probably would not have been built. In today’s world, Mitchell can’t imagine any single person driving such a massive undertaking.” — USA Today\n\n“Turns out that what you thought you knew about Lady Liberty is dead wrong. Learn the truth in this fascinating account of how a French sculptor armed with only an idea and a serious inability to take no for an answer built one of the most iconic monuments in history.” — O, the Oprah Magazine\n\n“Every American schoolchild learns the story: In a grand gesture representing their shared reverence for freedom, France presented to a grateful United States the imposing 305-foot Statue of Liberty. . . . Except, like all history, the story is a little more complicated than that. Elizabeth Mitchell takes us inside the statue’s history . . . Despite the statue’s iconic status in American culture, Bartholdi’s name probably does not spring into your mind as soon as you see its image. But Mitchell’s book does a fine job of retrieving him from the mists of history—and of recounting how long and hard he labored, not just artistically but financially and politically, to make the statue a reality. . . . Fascinating.” — Tampa Bay Times\n\n“Mitchell casts doubt on several myths about the genesis of and inspiration for Lady Liberty . . . Quite certain that the sculptor did not use his mother as the model for the statue’s face, Mitchell speculates that he may have had his deceased brother Charles in mind. And she suggests that there may be something to rumors, circulated at the time, that the body of Lady Liberty resembled Bartholdi’s paramour, later his wife.” — San Francisco Chronicle\n\n“The Statue of Liberty, which has stood at the entrance to New York’s harbor for more than a century and a quarter, is chiefly the work of a French sculptor named Frédéric Auguste Bartholdi . . . Mitchell tells the story of its construction . . . a good story.” — Washington Post\n\n“An absolutely brilliant and entertaining book—a delightful romp through a seemingly impossible history. It’s a bit amazing how much I didn’t know about the best-known statue in America, or its maker, Frédéric Bartholdi—a character so brazen and outrageous and charming that his life reads like a picaresque nineteenth-century novel. I delighted in every page.” — Elizabeth Gilbert, author of The Signature of All Things and Eat, Pray, Love\n\n“Filled with outlandish characters, fascinating tidbits and old world adventure, Liberty’s Torch is a rollicking read about one of America’s most beloved and, until now, misunderstood, icons.” — Maria Semple, author of Where’d You Go, Bernadette?\n\n“Is there any more globally recognizable American icon than the Statue of Liberty? Or any about which Americans know less? In Elizabeth Mitchell’s capable hands, the fascinating story of its quixotic creation—the mix of idealism and hustle, selflessness and selfishness, a crazy dream realized with breathtaking ingenuity—is a perfect parable for the moment mongrel America arose to become the world’s spectacular, improbable colossus.” — Kurt Andersen, author of True Believers\n\n“What we take for granted as a fait accompli was anything but, as we learn in this engrossing, witty, well-researched and surprising account of the Statue of Liberty’s bumpy path to glory. Mitchell does a beautiful job of breathing new life into a too-mythic tale, taking us behind the scenes to witness the hustling, chicanery, rivalries, back-stabbings, lies and disappointments that foreshadowed this eventually triumphant merger of patriotism, opportunism and the art world.” — Phillip Lopate, author of To Show and To Tell and Two Marriages\n\n“Elizabeth Mitchell is an inspired writer and Liberty’s Torch is a great book. While the French sculptor Frédéric Auguste Bartholdi, is Mitchell’s colorful hero, a gallery of historical figures like Victor Hugo and Joseph Pulitzer make grand appearances. My takeaway from Liberty’s Torch is to be reminded that the Statue of Liberty is the most noble monument ever erected on American soil.” — Douglas Brinkley, Professor of History at Rice University and author of The Wilderness Warrior: Theodore Roosevelt and the Crusade for America“},{“component”:”hc_column”,”id”:”column_HqIe6″,”column_width”:”col-md-12″,”animation”:””,”animation_time”:””,”timeline_animation”:””,”timeline_delay”:””,”timeline_order”:””,”css_classes”:””,”custom_css_classes”:”storeLinks”,”custom_css_styles”:””,”main_content”:[{“component”:”hc_column”,”id”:”column_ps5yl”,”column_width”:”col-md-2″,”animation”:””,”animation_time”:””,”timeline_animation”:””,”timeline_delay”:””,”timeline_order”:””,”css_classes”:””,”custom_css_classes”:””,”custom_css_styles”:””,”main_content”:[{“component”:”hc_adv_image_box”,”id”:”oCpvz”,”css_classes”:””,”custom_css_classes”:””,”custom_css_styles”:””,”image”:”https://elizabethmitchell.info/wp-con... “,”custom_css_classes”:””,”custom_css_styles”:””,”image”:”https://elizabethmitchell.info/wp-con... Elizabeth Mitchell recounts the captivating story behind the familiar monument that readers may have assumed they knew everything about.” — New York Times”,”extra_1″:””,”extra_2″:””,”icon”:{“icon”:””,”icon_style”:””,”icon_image”:””}}}}

“Liberty’s Torch reveals a statue with a storied past . . . Mitchell uses Liberty to reveal a pantheon of historic figures, including novelist Victor Hugo, engineer Gustave Eiffel and newspaper publisher Joseph Pulitzer. The drama—or “great adventure,” to borrow from the subtitle—runs from the Pyramids of Egypt to the backrooms of Congress. . . . By explaining Liberty’s tortured history and resurrecting Bartholdi’s indomitable spirit, Mitchell has done a great service. This is narrative history, well told. It is history that connects us to our past and—hopefully—to our future.”— Los Angeles Times\n\n“Streamlined and well constructed. . . . Proceeding chronologically, the author divides her story into three parts (“The Idea,” “The Gamble,” “The Triumph”) and opens with just the right amount of initial biographical detail on the designer, bolstering her portrait with further historical background as the narrative warrants. . . . deft strokes and always apt, telling details. . . . Mitchell successfully conveys the enormity of the undertaking and the infuriating amount of bureaucracy and old-fashioned glad-handing required to finish the job. . . . In Bartholdi, Mitchell has found a fascinating character through which to view late-19th-century America, and she does readers a service by sifting fact from fiction in the creation of one our most beloved monuments.” — Boston Globe\n\n“A myth-busting story starring the French sculptor Frédéric Auguste Bartholdi. Mitchell’s adjectives for him include crazy, driven, peevish and obnoxious. He rarely missed an opportunity to advance his own career, but Mitchell says he had “an incredible ability to soldier on” through a 15-year struggle. . . . Were it for not for Bartholdi, the statue probably would not have been built. In today’s world, Mitchell can’t imagine any single person driving such a massive undertaking.” — USA Today\n\n“Turns out that what you thought you knew about Lady Liberty is dead wrong. Learn the truth in this fascinating account of how a French sculptor armed with only an idea and a serious inability to take no for an answer built one of the most iconic monuments in history.” — O, the Oprah Magazine\n\n“Every American schoolchild learns the story: In a grand gesture representing their shared reverence for freedom, France presented to a grateful United States the imposing 305-foot Statue of Liberty. . . . Except, like all history, the story is a little more complicated than that. Elizabeth Mitchell takes us inside the statue’s history . . . Despite the statue’s iconic status in American culture, Bartholdi’s name probably does not spring into your mind as soon as you see its image. But Mitchell’s book does a fine job of retrieving him from the mists of history—and of recounting how long and hard he labored, not just artistically but financially and politically, to make the statue a reality. . . . Fascinating.” — Tampa Bay Times\n\n“Mitchell casts doubt on several myths about the genesis of and inspiration for Lady Liberty . . . Quite certain that the sculptor did not use his mother as the model for the statue’s face, Mitchell speculates that he may have had his deceased brother Charles in mind. And she suggests that there may be something to rumors, circulated at the time, that the body of Lady Liberty resembled Bartholdi’s paramour, later his wife.” — San Francisco Chronicle\n\n“The Statue of Liberty, which has stood at the entrance to New York’s harbor for more than a century and a quarter, is chiefly the work of a French sculptor named Frédéric Auguste Bartholdi . . . Mitchell tells the story of its construction . . . a good story.” — Washington Post\n\n“An absolutely brilliant and entertaining book—a delightful romp through a seemingly impossible history. It’s a bit amazing how much I didn’t know about the best-known statue in America, or its maker, Frédéric Bartholdi—a character so brazen and outrageous and charming that his life reads like a picaresque nineteenth-century novel. I delighted in every page.” — Elizabeth Gilbert, author of The Signature of All Things and Eat, Pray, Love\n\n“Filled with outlandish characters, fascinating tidbits and old world adventure, Liberty’s Torch is a rollicking read about one of America’s most beloved and, until now, misunderstood, icons.” — Maria Semple, author of Where’d You Go, Bernadette?\n\n“Is there any more globally recognizable American icon than the Statue of Liberty? Or any about which Americans know less? In Elizabeth Mitchell’s capable hands, the fascinating story of its quixotic creation—the mix of idealism and hustle, selflessness and selfishness, a crazy dream realized with breathtaking ingenuity—is a perfect parable for the moment mongrel America arose to become the world’s spectacular, improbable colossus.” — Kurt Andersen, author of True Believers\n\n“What we take for granted as a fait accompli was anything but, as we learn in this engrossing, witty, well-researched and surprising account of the Statue of Liberty’s bumpy path to glory. Mitchell does a beautiful job of breathing new life into a too-mythic tale, taking us behind the scenes to witness the hustling, chicanery, rivalries, back-stabbings, lies and disappointments that foreshadowed this eventually triumphant merger of patriotism, opportunism and the art world.” — Phillip Lopate, author of To Show and To Tell and Two Marriages\n\n“Elizabeth Mitchell is an inspired writer and Liberty’s Torch is a great book. While the French sculptor Frédéric Auguste Bartholdi, is Mitchell’s colorful hero, a gallery of historical figures like Victor Hugo and Joseph Pulitzer make grand appearances. My takeaway from Liberty’s Torch is to be reminded that the Statue of Liberty is the most noble monument ever erected on American soil.” — Douglas Brinkley, Professor of History at Rice University and author of The Wilderness Warrior: Theodore Roosevelt and the Crusade for America“},{“component”:”hc_column”,”id”:”column_HqIe6″,”column_width”:”col-md-12″,”animation”:””,”animation_time”:””,”timeline_animation”:””,”timeline_delay”:””,”timeline_order”:””,”css_classes”:””,”custom_css_classes”:”storeLinks”,”custom_css_styles”:””,”main_content”:[{“component”:”hc_column”,”id”:”column_ps5yl”,”column_width”:”col-md-2″,”animation”:””,”animation_time”:””,”timeline_animation”:””,”timeline_delay”:””,”timeline_order”:””,”css_classes”:””,”custom_css_classes”:””,”custom_css_styles”:””,”main_content”:[{“component”:”hc_adv_image_box”,”id”:”oCpvz”,”css_classes”:””,”custom_css_classes”:””,”custom_css_styles”:””,”image”:”https://elizabethmitchell.info/wp-con... “,”custom_css_classes”:””,”custom_css_styles”:””,”image”:”https://elizabethmitchell.info/wp-con... Elizabeth Mitchell recounts the captivating story behind the familiar monument that readers may have assumed they knew everything about.” — New York Times”,”extra_1″:””,”extra_2″:””,”icon”:{“icon”:””,”icon_style”:””,”icon_image”:””}}}}

October 29, 2019

Premier of LIBERTY: MOTHER OF EXILES on HBO

It was such a pleasure serving as a consultant on this HBO documentary about the Statue of Liberty, directed by Fenton Bailey and Randy Barbato. I remember picking up a call a few years ago out of the blue from Diane von Furstenberg who said, “You’ve gotten me into a lot of trouble.” She had read Liberty’s Torch and realized she wanted to be part of the story. She went on to create the Liberty Museum and executive produce and star in this documentary. Watch if you want to feel good about the people who share this nation. And my favorite part: to be reminded that something is kitsch when the emotion behind it is too big for the object.

It was such a pleasure serving as a consultant on this HBO documentary about the Statue of Liberty, directed by Fenton Bailey and Randy Barbato. I remember picking up a call a few years ago out of the blue from Diane von Furstenberg who said, “You’ve gotten me into a lot of trouble.” She had read Liberty’s Torch and realized she wanted to be part of the story. She went on to create the Liberty Museum and executive produce and star in this documentary. Watch if you want to feel good about the people who share this nation. And my favorite part: to be reminded that something is kitsch when the emotion behind it is too big for the object.

http://www.hbo.com/video/documentaries/liberty-mother-of-exiles/videos0/trailer

December 14, 2016

Editing

Elizabeth Mitchell has edited books for publication, consulted on screenplays and treatments, coached book proposal writing, and edited white papers. She was executive editor of George, having started with the magazine as a senior editor before George’s launch in 1995. Prior to that, she worked as features editor at SPIN.

Here are links to a few of her book editing projects:

Upcycle: Beyond Sustainability – Designing for Abundance, by William McDonough and Michael Braungart, forward by President Bill Clinton.

The Right Words at the Right Time, by Marlo Thomas.

Domestic Affairs, a novel by Bridget Siegel.

November 29, 2016

NEW YORK STORIES: How this hastily shot image of John Lennon became an enduring symbol of freedom

Who knows what Strom Thurmond had against the Beatles, but the senator from South Carolina certainly knew how to make John Lennon’s life miserable. On Feb. 4, 1972, the 69-year-old, anti–Civil Rights agitator wrote a few lines to Attorney General John Mitchell and President Richard Nixon’s aide, William Timmons, which would end up threatening Lennon with deportation and entangling him in legal limbo for almost four years.

“This appears to me to be an important matter, and I think it would be well for it to be considered at the highest level,” Thurmond wrote. “As I can see, many headaches might be avoided if appropriate action can be taken in time.”

Thurmond attached a one-page Senate Internal Security Subcommittee report explaining that Lennon appeared to be a threat to Republican interests, particularly their desire to re-nominate Nixon at the San Diego convention that coming summer. Citing a New York Times article and an unidentified informant, the report explained that Lennon was friendly with various left-leaning political activists, including Yippie leader Jerry Rubin. The leftists had gathered in New York and discussed the possibility of Lennon appearing at concerts on college campuses to promote voter registration, marijuana legalization and bus trips to the Republican convention for throngs of willing protesters.

In reality, while Lennon, then 31, spoke his mind about many political issues, he always felt that, as a British citizen, he shouldn’t endorse or attack individual U.S. candidates, says his friend, photographer Bob Gruen. Lennon and his wife Yoko Ono strove never to be negative. “They weren’t anti-war. They were pro-peace,” Gruen says. “They weren’t against a politician, they were for voting.”

NOWHERE MAN Lennon, who had recently turned 34, had much on his mind when he boarded the ferry to Liberty Island. He was estranged from wife Yoko Ono, and embroiled in costly legal disputes with his former Beatles bandmates.

NOWHERE MAN Lennon, who had recently turned 34, had much on his mind when he boarded the ferry to Liberty Island. He was estranged from wife Yoko Ono, and embroiled in costly legal disputes with his former Beatles bandmates. (© BOB GRUEN / WWW.BOBGRUEN.COM)

Gruen recalls that Lennon recounted listening to Rubin, Abbie Hoffman and Tom Hayden hashing out radical plots while Allen Ginsberg sat in the corner, cross-legged, ringing little Indian bells and chanting ommm . “John told me, ‘Ginsberg was the only one who made sense,’ ” Gruen says, laughing.

Thurmond’s note, however, had its desired effect. It climbed a few links up the chain of command, and by the end of February, an Immigration and Naturalization Service letter appeared under the door of Lennon and Yoko’s apartment telling them they had until March 15 to leave the country.

According to the INS, Lennon was an “excludable alien.” In 1968, a police drug squad had conducted a warrantless search of his London flat and found a half ounce of hashish. Lennon claimed he hadn’t known the hash was there and, in fact, had swept the apartment three weeks earlier on a tipoff that the squad would be coming. (Since Jimi Hendrix had been a previous tenant he left nothing to chance.) He and Ono had even gotten a friend in the police force to pre-search the place to make sure they were clear. But the raiding officers discovered the stash in a pair of binoculars, found in an untouched box of possessions that had been moved from his previous residence. Lennon pleaded guilty and paid a 150-pound fine. The charge, he thought, was behind him.

GALLERY: John and Yoko and May

Now it made him excludable under a provision against individuals convicted of marijuana possession. He would go on to spend large amounts of money, time and words in his battle to remain in New York, and on Oct. 30, 1974, he and Gruen created an image that would make his case succinctly.

Speaking of his adopted country as a guest on Tom Snyder’s talk show in April 1975, Lennon said, “I love the place. I like to be here. I’ve got a lot of friends here, and it’s where I want to be, Statue of Liberty…welcome.”

***

Bob Gruen has lived at the Westbeth Artists Community, the subsidized-housing complex in Manhattan’s West Village, since 1970. Visiting him there requires a wormhole-like journey to the past that takes you down surreally long hallways, up an elevator and down a flight of stairs. His apartment is packed with so much reminiscence, it could serve as a toddler’s alphabet teaching tool: Bugle, beads, Bowie, boas, buttons, Blondie. Cartoon, Clash, couch, CDs.…

Jimmy Breslin tells of cops who aided John Lennon in 1980

Concert posters mosaic the walls. Rows of filing cabinets are marked with labels such as LED ZEPPELIN and PUNK SELECTIONS. To the left is a kitchen disguised as a storage space and, near it, the door to the bathroom, where Gruen used to develop prints. The place would seem large if left empty, but nearly five decades of professional success strain the seams with contact sheets of outtakes, negatives, color prints, black and whites, contrast variations: all to secure a career’s worth of perfect photographic moments, in this case, the one-sixtieth of a second that John Lennon posed beneath the Statue of Liberty and flashed the peace sign.

The son of a Hungarian immigrant mother who, ironically, was also an immigration lawyer, Gruen, 71, has the worn, happy look of a man who has enjoyed a lot of encores. His coronet of white-gray hair frames lucid blue eyes. He has a comedian’s delivery and a core confidence, which is probably why music gods such as Ike and Tina Turner, David Johansen, Joe Strummer, Joey Ramone and Debbie Harry liked to hang out here. Lennon used to kick back in the same place where the newer couch lives now.

As an official photographer to Lennon and Ono (who at the time of the Liberty photo was estranged from her husband), he was allowed near total access to the duo, in exchange for unique images that might be used when record companies or media outlets called. He would take the pictures for free and get paid when the image landed on a record cover or in a promotional campaign.

Gruen first met Lennon and Ono backstage at the Apollo Theater in December 1971, at a benefit concert for families of prisoners injured at Attica. Gruen started taking snapshots in a scrum of four or five other fans. While watching the cube flashes popping, Lennon said, “Everyone is always taking pictures. Why do we never see these photos? What happens to them?”

NIGHT THAT CITY STOPPED COLD. Lennon’s death still haunts New Yorkers

Gruen volunteered that he lived around the corner from Lennon’s Bank Street apartment and would deliver his once they were developed.

“You live around the corner?”

“Yeah.”

“Well, slip them under my door.”

When Gruen dropped by with the prints, Jerry Rubin answered, which shocked Gruen, since he had only seen the radical in the midst of riots. He asked Rubin to pass the pictures to Lennon, rather than delivering them personally. This lack of pushiness impressed Lennon and Ono, who later asked him to be their photographer, sealing the deal by saying they wanted to “know him.” Before long, a deep bond was forged between the photographer and his subjects/employers.

Scrolling back to that day in 1974, Gruen recalls proposing the idea of the Statue of Liberty portrait during a recording session for “Rock n’ Roll,” Lennon’s album of oldies covers. Gruen’s intention for this photo was not commercial; he intended the shot to spark deeper support for Lennon. “To me, the case was urgently important,” Gruen says.

Lennon liked the idea immediately. Returning from the studio on Oct. 29, Gruen dropped Lennon off at his apartment. Lennon told him, “See you tomorrow. Bring your eyes.”

***

This was one of the last months of the infamous period known as Lennon’s “lost weekend,” when Ono sent her husband packing with their 22-year-old assistant, May Pang, and encouraged them to become romantic. Lennon had burned up L.A. on back-and-forth trips for six months, over-imbibing and over-indulging with Harry Nilsson, Keith Moon and their Hollywood pals, and had come back to New York with Pang in the spring for a return to tranquility.

Pang recalls that Lennon was constantly worried about the deportation battle. “He did not want to leave. He loved this country so much,” she says. “The fact that they let in musicians who had done worse things than him really hurt him. He thought, ‘I’m being singled out.’ And he was.” He couldn’t risk immediate deportation by traveling overseas, so he sacrificed visits to friends and family and resolved to stay and fight.

When Gruen arrived at Lennon and Pang’s apartment on E. 52nd Street for their Liberty excursion, Lennon was wearing his favorite black coat, black scarf and black sweater. Gruen appreciated the formality and seriousness of the fashion choice and, as an added benefit, the clothes wouldn’t distract from the image’s simplicity.

Lennon also wore a pin with the words LISTEN TO THIS BUTTON framing a cropped picture Gruen had taken of Lennon’s eyes. The pin was the detritus from a commercial campaign for Lennon’s most recent album “Walls & Bridges,” which was meant to include a billboard in Los Angeles that would “play” the whole album. Unfortunately, L.A. said no to singing billboards.

Pang had grown up in Harlem and Spanish Harlem, but she had never been to visit the statue. Now she and Lennon hoped to get a chance to go into the crown.

They drove down through Manhattan in Gruen’s car. New York was a hair’s breadth from bankruptcy at the time, which happened to echo Gruen’s own financial status. A bottle of Paisano wine went for $1 and a slice of pizza for a quarter, and you could live on that most of the day. Lennon roamed the city relatively undisturbed. He would call Gruen to meet him at a bar and when, after a few hours, the place started filling with fans summoned by other fans spreading the word by pay phone, they would simply move to another club and buy hours of peace again.

Polaroid of Bob Gruen and John Lennon in front of Statue of Liberty, NYC. October 30, 1974. © Bob Gruen / www.bobgruen.com

(© BOB GRUEN / WWW.BOBGRUEN.COM)

Not Released (NR)

(LARRY BUSACCA/GETTY IMAGES)

INSTANT KARMA Bob Gruen and John Lennon pose for a Polaroid snap in front of Statue of Liberty on Oct. 30, 1974, the day they made the now-famous images. Gruen (at right) in recent times.

As they got out of the car at Battery Park, Lennon pointed up to the Financial District skyscrapers. “I bet I’m paying rent in all these places,” he told Gruen.

“What do you mean?”

“Well, I have so many lawyers…” Lennon joked. He was fighting with his American manager Allen Klein at the time. He was more than three years into his legal struggle to break up the Beatles. And overriding all this was the time spent wrangling deportation, which had now exceeded two years. “The funny thing about lawyers,” Lennon continued, “is we go to meet them and they have a modest, regular office and we go back six months later for another meeting and they have a big impressive office and my picture’s on the wall.”

The reality was that Lennon’s sizeable personal wealth was stuck an ocean away while he waited for his U.S. residency, and his business income sat in receivership, awaiting resolution of his battle with Klein and the dissolution of the Beatles. Gruen recalls walking a late-night street with Lennon when a fan spotted him and did a triple take.

“You know, you look just like John Lennon?” the man said.

“I wish I had his money,” Lennon quipped, his standard deflection, which at that particular moment, had the virtue of being absolutely true.

***

This wasn’t Lennon’s first brush with Liberty. He had included a Liberty postcard in the 1972 album art for Lennon’s and the Plastic Ono Band’s “Some Time in New York City,” with a raised power fist replacing the hand holding the torch. Six years earlier, Paul McCartney and Lennon had circled Liberty Island for their first Apple Records board meeting.

BUTTON UP Lennon wore his favorite black coat and a pin from the promotional campaign for his most recent album.

BUTTON UP Lennon wore his favorite black coat and a pin from the promotional campaign for his most recent album. (© BOB GRUEN / WWW.BOBGRUEN.COM)

As Gruen bought their ferry tickets, a returning boat pulled in, which, oddly enough, happened to be packed with teenage girls. When they spotted Lennon, they immediately began shrieking. Lennon hushed them, promising, “If you stop yelling, I will sign for everybody.” He dashed off the signatures fast enough that the trio was able to catch that next boat.

Arriving on the island, they encountered an off-duty park ranger named Angel who joined them on their mission to snap the image that scores of tourists had taken countless times before — though in this case it was a world-famous British tourist who needed to be back in the studio by 4 p.m.

Nowadays, no one would take a celebrity to a photo-shoot site without visiting days ahead with a stand-in, for the lighting, the correct angle. On that October day, armed with two Nikon F cameras, one loaded with black-and-white and the other with Ektachrome daylight film, Gruen was surprised by the challenge of trying to include both the 5-foot-11 Lennon and 305-foot Liberty in the same frame. “You can only back up so far because it’s an island,” he points out, and he didn’t want the distortion of a wide angle. Given the cloud cover, Gruen used a flash, and since film costs money and developing costs time, he took only 28 black-and-white frames and two rolls — about 70 images — in color.

In one pose, John Lennon held up a Bic lighter, imitating the Statue. Hand on hip, hand down. Gruen liked when Lennon flashed the peace sign, because to him it looked like Lennon promising the government he would be good.As Gruen took pictures, Pang noticed security guards with earpieces starting to watch them. “I think we better go,” she warned. They regretfully hurried off the island, having failed to experience that thrill of going to the crown. “To see New York at its finest, for what this Liberty stood for…,” she says of those days in the’70s. “If you could stand up there and look out and say, ‘So this is my city.’ Nothing could beat that. What a magnificent view that would be. The closest we ever got was to be on that island.”

Later, in the darkroom, Gruen considered removing a KEEP OFF GRASS sign that wound up in the lower-right side of the frame. Gruen usually tried to avoid excess words in his images, but the sign’s accidental admonition proved to be too perfect. After all, it was ostensibly the disputed six-year-old cannabis-possession charge that the government was using to try to boot Lennon out of the country.

***

Chillingly, years later, Lennon’s killer, Mark David Chapman, remembered the Statue of Liberty photo as being on the cover of a paperback about Lennon he’d found at a library in Hawaii, the book that sparked his psychotic rage. When Chapman first visited New York to plot his crime, he thought he might jump from the crown to end his life, since no one had ever attempted such a spectacular suicide, and the notoriety, which he so desperately sought, would be about equal, he thought, to that gained by murdering Lennon.

Thirty-six years after that fateful night, Chapman’s vicious act still leaves Gruen in tears. “It’s the stupidest thing that ever could be,” he says of the uselessness of his friend being killed.

That December of 1980, Gruen had been photographing Lennon and Ono’s recording sessions for “Milk and Honey,” their companion album to “Double Fantasy.” Usually, Gruen drove them home since they preferred the normalcy to the limousine. That unforgettable Monday, Gruen was printing the photos from their session two days before.

FOR THE RECORD Gruen was granted near total access to Lennon and Ono; the images he provided made for an enduring glimpse of the rocker, in what would be the final decade of his life. (LEO LA VALLE/EPA)

When he had spoken with Lennon in the studio, his friend was elated. The new album was near completion. Then they would start making videos, rehearse and, by April, would embark on a world tour, with Gruen along for the adventure. They would eat at their favorite Tokyo restaurants. They would meet world leaders. Gruen hurried through the developing so he could get to Lennon and Ono in the studio by 1 a.m., when they usually departed. But the recording machinery at the studio glitched that night, and Lennon and Ono had no choice but to conclude early.

Gruen recalls his doorman buzzing him around 11 p.m., telling him to turn on the radio. “Lennon’s been shot,” the doorman said.

Gruen first assumed his friend had fallen victim to the crack epidemic then ruling the city. Lennon never carried money, so maybe he had gotten mugged and the addict had shot him in the leg, or arm. “Shot isn’t dead,” Gruen recalls thinking, clinging to that slim hope.

Then, a former colleague phoned. He reported that he had seen blood everywhere on the TV. “Lennon’s dead,” he confirmed.

“I kind of sank to the ground,” Gruen says. As he lay on the floor, all the plans he and his friend had delighted in, ended in an instant. He started obsessing over hypothetical events that would haunt him for years: If he had gotten to the studio earlier, he would have convinced Ono and Lennon to go out to eat, like they always did, maybe at the Russian Tea Room. Waiting for Lennon to return home, the assassin would ultimately have succumbed to the December cold and given up. Or Gruen would have driven his injured friend to the hospital faster than medical care could reach him.

The phone rang as Gruen lay motionless. It kept ringing, then stopped, and would ring again. He lay there. And then another call. It occurred to him what the ringing meant: The whole world was watching. He was the photographer. It was his job to make Lennon look good. He crawled to his filing cabinets, in the very space where he works today, and began pulling pictures.

Pang recalls hearing the news on the radio at a friend’s and rushing back to her home. She telephoned David Bowie, who had been a good friend to Pang and Lennon. The singer was out on a date, but his assistant told Pang to come to his apartment immediately. She recalled being there when Bowie careered out of the elevator, unhinged by grief, crying and screaming in disbelief. They huddled by the television through the night, trying to make sense: “Who was this person?”

Returning home, she found the city in mourning. “It was the first time I ever heard New York be so quiet. On every level,” Pang remembers. “On the bus. No one was talking. And you saw the headlines.”

Gruen says that Ono later talked about the importance of the flag carrier in a crusade. When the one holding the flag gets shot, somebody has to pick up the flag and keep going. “He was holding a pretty big flag,” Gruen says, “but fortunately a lot of people have come behind him and we keep going. Yoko’s doing the lion’s share.”

John Lennon on the ferry to the Statue of Liberty, NYC. October 30, 1974. © Bob Gruen/www.bobgruen.com

(© BOB GRUEN / WWW.BOBGRUEN.COM)

John Lennon posing at the Statue of Liberty, NYC. October 30, 1974. © Bob Gruen/www.bobgruen.com

(© BOB GRUEN / WWW.BOBGRUEN.COM)

PITCH-PERFECT Gruen snapped about 28 black-and-white frames and 70 in color. He considered removing the sign at Lennon’s feet, but couldn’t resist the accidental irony of its admonition.

Liberty carried the torch across the Atlantic, to shine on what was then the world’s only healthy democracy. Like Frédéric Auguste Bartholdi, who created the Statue of Liberty from his own inspiration and industry, Gruen invented those images of Lennon and the Statue of Liberty and holds the copyright. Like Bartholdi, Gruen has to some extent lost control of those rights. Bartholdi gave up his battle against the advertisers, postcard makers, and figurine forgers who stole the image immediately. Gruen says he tries to track its usage, yet he can’t help but be thrilled that people like it. He visited the Statue a few years ago and watched the multitudes of visitors striking the Lennon pose. “It’s the price of making something world-famous,” Gruen says. “It’s now part of the world.”

When the 29-year-old photographer took the photo in 1974, the image was meant to reflect the deportation struggle, but since Lennon’s death, it has taken on new meaning. “Now it’s a picture of two symbols of freedom. To me, Lennon represents personal freedom,” he says. Gruen considers it his unique accomplishment that he got those icons of personal freedom in the same place. For one-sixtieth of a second.

Pang remembers Lennon’s reaction when he realized that Thurmond and the government had been campaigning against him and had caused his years of suffering. “I remember John saying, ‘Can you believe they are afraid of me?’ That amazed him.”

Two days before John Lennon’s 35th birthday in 1975, federal Judge Irving Kaufman rejected the government’s deportation appeal. The judge threw out the case because deportation was not meant to be a punitive act; “moral culpability” mattered in the marijuana-possession charge, and Lennon did not appear to know he had marijuana on the premises. But Kaufman added remarks about the deeper meaning of the deportation attempt: “If in our 200 years of independence, we have in some measure realized our ideals, it is in large part because we have always found a place for those committed to the spirit of liberty and willing to help implement it,” Kaufman wrote in his decision. “Lennon’s four-year battle to remain in our country is testimony to his faith in this American dream.”

NEW YORK STORIES: “The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan” cover immortalizes a budding Greenwich Village love story

SHE BELONGS TO ME Bob Dylan and Suze Rotolo channeled the essence of young love when they snuggled on a Greenwich Village street for a photo that would become an instant classic.

If you walk along Jones Street in Greenwich Village, facing W. Fourth Street with Bleecker Street at your back, you’ll find yourself in the exact spot where Bob Dylan was captured on the cover of “The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan” in 1963. To experience it like Dylan did, you should go in the fading light of a February afternoon, dirty slush on the streets and a VW van parked against the curb. You should wear a suede jacket, too thin for the cold, and have your first real love braced against your arm. Around the corner, your $60-a-month apartment should await you, where you sometimes write songs — some to this first love on your arm — songs that would make you legendary the world over.

The photograph from “Freewheelin’ ” captures Suze Rotolo and Bob Dylan at a time when they lived on the cheap, wearing thrift-store or handmade clothes, mining second-hand book and record stores, slipping into neighborhood theaters and clubs easily accessed by friends with power over guest lists. Just around the corner on Sixth Avenue and Bleecker Street, Zito’s bakery gave out free hot bread to night owls. Grit mixed with glamour. A little farther on and to the east, a butcher on Bleecker and Thompson offered chickens for slaughter, then boiled them free of feathers. Four blocks north, the House of Detention prisoners yelled and catcalled from their exercise roof.

Rotolo and Dylan were 19 and 21, respectively, when Don Hunstein snapped the now-legendary photo, and while the image didn’t represent a seismic shift in folk-record iconography, its personal pulse remains intense. Rotolo was not a hired model. No one prepped hair and makeup. They walked down the street toward a Columbia Records staff photographer Dylan knew and liked, and who had shot him in the studio when he recorded his first album, “Bob Dylan,” in 1961, as well as that record’s cover. Thirty-year-old Billy James, Dylan’s Columbia publicist (the only “suit” Dylan is said to have trusted) looked on, there just for the fun of it.

The truth of first love remains frozen in this photo — ironic, as it was taken in an age of lies. For starters, Dylan was hiding his past and his real name. Until 1989, Rotolo would never publicly reveal that her parents were Communists. Rotolo and Dylan lived together, a situation they kept hidden from her suspicious mother. So much subterfuge, but not in this image.

***

Dylan met Rotolo backstage a year and a half earlier, in July 1961, during a 12-hour live folk radio broadcast at Riverside Church. “Meeting her was like stepping into the tales of 1,001 Arabian nights,” he wrote in his memoir “Chronicles: Volume One.” “She had a smile that could light up a street full of people and was extremely lively, had a particular type of voluptuousness.” He wrote he “could feel her vibe thirty miles away.”

At 75 years old, it’s time for burnt out Bob Dylan to retire

Rotolo was deep for a teenager. A red-diaper baby, she put herself through art school by working odd jobs in theaters and at CORE, the Congress of Racial Equality, and, at the time, house-sitting in her aunt’s West Village apartment. She had spent large portions of her life wandering the pages of books, and was fine-tuned by tragedy: Her father had died only recently, and she had just weathered a life-threatening car accident. When she fell for Dylan it was because she came to understand, as she explained to Dylan’s biographer Robert Shelton, “how frighteningly sharp he was.”

BOHEMIAN RHAPSODY The Gaslight Cafe on McDougal Street in The Village, a magnet for beat poets when it opened in 1958, became a launchpad for Dylan and other drivers of the 1960s folk scene.

BOHEMIAN RHAPSODY The Gaslight Cafe on McDougal Street in The Village, a magnet for beat poets when it opened in 1958, became a launchpad for Dylan and other drivers of the 1960s folk scene. (CHARLES PAYNE)

They became a closed circle of two. “He was eccentric,” says folk singer Sylvia Tyson, who knew Dylan almost from his arrival in New York City, and befriended Rotolo because she contrasted so sharply with the groupies on the folk scene. “But he was eccentric in the contrived way that very young people get into, to try to make themselves interesting.”

At the beginning of their relationship, Dylan bunked on the couch of any friend or acquaintance who would have him. “Before Suze, he basically was hitting on girls because he needed a place to sleep,” Tyson recalls. But signing to Columbia less than two months after they met brought cash, and Dylan found them a home — a two-room apartment on the third floor of a four-story walk-up at 161 West Fourth Street.

Until November, when she would turn 18, Rotolo couldn’t legally live with him, but they entwined their lives. In the Village’s crooked streets, they grazed some of the estimated 50 neighborhood coffee houses, for improv or original plays, or 15-minute folk sets, from noon to the small hours. They would hit the Village Vanguard for jazz, still in operation today. Or for folk, Gaslight or Gerde’s Folk City or Village Gate, all now closed. A chummy band of fellow artists would be feasting on the inspiration at these venues. She even attended the recording sessions for his first album.

Kesha crushes BMA performance, ignores Dr. Luke controversy

As Rotolo wrote in her vivid memoir, “A Freewheelin’ Time,” Dylan was a shape-shifter from the first, whether to make himself unaccountable, or as an amusement, or as a goose to creativity. While no one in the Village at the time cared about people’s pasts, only their ability to fully occupy the present, Dylan hid that he was Robert Zimmerman, born in Duluth, Minn., even from Rotolo. An article in the New York Mirror about the Riverside Church show on the day they met reports that “Bob Dylan of Gallup, N.M., played the guitar and harmonica simultaneously, and with rural gusto.” He even told Rotolo he had been abandoned in that state and joined a traveling circus. A few months into their relationship, she learned the truth when he drunkenly stumbled coming into their apartment and his wallet and draft card fell to the floor.

***

Ten months after they met, Rotolo changed the course of music history: by leaving Dylan.

When she set out for Europe on June 9, 1962, she thought she was simply off for the summer to study art in Perugia. But as soon as the boat set sail, she felt stunned, watching him recede. She tried to evoke his ghost by teaching a fellow passenger Dylan’s recently written song called “Blowin’ in the Wind,” which would go on to be the first song of “Freewheelin’ ”

NYC PAPERS OUT. Social media use restricted to low res file max 184 x 128 pixels and 72 dpi

’61 REVISITED The block that Dylan and Rotolo immortalized on the cover of “Freewheelin‘ ” is leafier than when the photo was shot, though it remains relatively unchanged. (ROBERT SABO/NEW YORK DAILY NEWS)

Dylan pined for her so immediately she found his first letter waiting at her Paris hotel when she arrived. Over the next months, he sent her Byron’s poetry and tender, sulky love letters. They made $100 phone calls to each other. She read the book about Picasso by his lover Francoise Gilot and immediately recognized Dylan as Picasso’s twin. But it was a cautionary tale: You could get sucked into a genius’ orbit, but art would always win the genius’ ardor.

His letters reflected that conflict. When he addressed her in text, he was passionate, revealing and honest, but that person lived in the ink. “I tried to figure out this guy who was calling me to come home to him, writing letters full of love,” she wrote in her memoir, “yet when I was with him, he seemed to take my presence for granted.”

In late October, at the height of the Cuban Missile Crisis, he spent a night drinking at one of their favorite Village hangouts, the now-closed Figaro Cafe. “If the world did end that nite, all I wanted was to be with you,” he wrote to her. “And it was impossible cause you’re so far away — And that was why it seemed so hopeless.”

***

When the “Freewheelin’ ” photo session occurred on that February 1963 day, the couple had only been reunited for a few weeks. Robert Zimmerman was gone. A man officially named Bob Dylan had greeted her (carrying with him a new draft card to prove it). His first album had been popular, but this next album — due for release in May — would change everything. Early on, Dylan only sang other people’s folk songs. But Rotolo had introduced him to the poetry of Rimbaud, as well as Kurt Weill and Bertolt Brecht’s song “Pirate Jenny,” which Dylan “unzipped” for inspiration. In his feverish creativity, he had brought forth to her “Don’t Think Twice,” and for future albums, “Boots of Spanish Leather” and “Tomorrow Is a Long Time.”

VILLAGE PEOPLE Dylan and Rotolo in September 1961, about a month after they met.

VILLAGE PEOPLE Dylan and Rotolo in September 1961, about a month after they met. (MICHAEL OCHS ARCHIVES)

As a photographer, Hunstein would prove to be the perfect man for the moment. He preferred a documentary style and had already created stunning images of such luminaries as Johnny Cash, Igor Stravinsky, Barbra Streisand and Miles Davis. He talked to his subjects, drew them out, isolated an essential quality about them. “I was merely a living witness,” he told a journalist in the introduction to his “Keeping Time: The Photographs of Don Hunstein.” “What does any good journalist do?…Observe the artist and their expressions, then leap in.”

The group started in Dylan and Rotolo’s apartment, which Hunstein termed “bleak.” But the sparseness, including Dylan’s furniture, much of which he had built on the premises, didn’t seem particularly unusual to Billy James, the publicist. “Everyone had modest places back then,” he says.

Hunstein initially took a few shots of the image-conscious Dylan in his street-salvaged armchair. Then the photographer suggested Rotolo join. Reluctantly, she hung over the back of the chair while Dylan strummed his guitar. As the shutter clicked, the charisma between the two became apparent. Hunstein had isolated something essential about Dylan.

The light was fading so Hunstein suggested they go outside. Rotolo wrote in her memoir that she was already wearing a heavy sweater in the freezing apartment but pulled on an overcoat, making her feel like an Italian sausage. Dylan cared more about appearance and chose a favorite jacket.

The first outdoor shots focused on Dylan at the bottom of the front stoop and then the couple in the same place, her head leaning on his shoulder. Eventually Hunstein sent them against traffic on quiet one-way Jones Street and instructed them to walk back toward him. He had shot only one color roll and a few in black and white when the light failed.

Not Released (NR)

HE WAS THERE Dylan perfoming at The Bitter End, another famed Village mainstay, in 1961. (SIGMUND GOODE/GETTY IMAGES)

In the photo, they look happy, united in their closeness, which is how observers of the time considered them. “When the ‘Jones Street’ cover came out, it was totally appropriate to everyone,” says folksinger Carolyn Hester, who helped Dylan get discovered by inviting him to play harmonica on her own Columbia album. Rotolo’s anonymity quickly vanished. “People definitely recognized Suze on the street because of the cover.”

“I thought it was a lovely photograph,” says guitarist Barry Kornfeld, a friend of Dylan’s then, and a lifelong friend of Rotolo’s. “I thought it was unusual to have your girlfriend on your album cover. Somebody who was not involved in the album.” But maybe the deeper message was: She had contributed.

***

Love got more complicated as Dylan’s fame accrued. In 1963, Dylan felt the power of Joan Baez’s reflective light when they performed together at the Newport Folk Festival in July, and later during the March on Washington in August. Rumors began. “I think he was very much in love with Suze,” Tyson says. “I think the Joan Baez thing took her entirely by surprise.”

That same month Rotolo moved into her sister’s apartment on Avenue B, and soon realized she was pregnant. Dylan and Rotolo considered the option of keeping the baby, but decided it couldn’t work, and went, both of them terrified, to a New York City doctor for an illegal abortion.

LOCAL HERO Dylan frequently performed at Gerdes, a legendary folk venue at W. Fourth and Mercer Streets. This poster is dated September 1961.

LOCAL HERO Dylan frequently performed at Gerdes, a legendary folk venue at W. Fourth and Mercer Streets. This poster is dated September 1961. (BLANK ARCHIVES/GETTY IMAGES)