Matt Rees's Blog - Posts Tagged "literature"

Python mistakes Palestinians for Buddhists

Last week at the Palestine Literature Festival, Michael Palin produced some of his funniest material since his Monty Python heyday. However, he probably didn’t intend it to be funny.

Palin told an audience that was rather lacking in actual Palestinians – mainly locally based international aid workers, diplomats and heaven knows who else – that he had seen how Israeli checkpoints worked. He thought it’d be a good idea to “always look on the bright side of life” and see the checkpoints as an opportunity for Palestinians to slow down. It saves them, he suggested, from the kind of frenetic pace that drives people crazy in other places, where there are no checkpoints.

A few attendees were perturbed by Palin’s comments. After all, the point of the checkpoints is less to slow down Palestinians and, more frequently, to prevent them moving about at all. Still he got off lightly. In Palestine, everybody expects the Spanish Inquisition…

I think Palin’s remarks were delightful. He’s trying to find something good about an aspect of life which most people only see as wicked and frustrating. Always look on the bright side of life, right?

It’s not his fault if he mistook the Palestinians for Buddhists.

Palin told an audience that was rather lacking in actual Palestinians – mainly locally based international aid workers, diplomats and heaven knows who else – that he had seen how Israeli checkpoints worked. He thought it’d be a good idea to “always look on the bright side of life” and see the checkpoints as an opportunity for Palestinians to slow down. It saves them, he suggested, from the kind of frenetic pace that drives people crazy in other places, where there are no checkpoints.

A few attendees were perturbed by Palin’s comments. After all, the point of the checkpoints is less to slow down Palestinians and, more frequently, to prevent them moving about at all. Still he got off lightly. In Palestine, everybody expects the Spanish Inquisition…

I think Palin’s remarks were delightful. He’s trying to find something good about an aspect of life which most people only see as wicked and frustrating. Always look on the bright side of life, right?

It’s not his fault if he mistook the Palestinians for Buddhists.

Published on June 04, 2009 07:04

•

Tags:

checkpoints, israel, israelis, literature, michael, monty, palestine, palestinians, palin, python

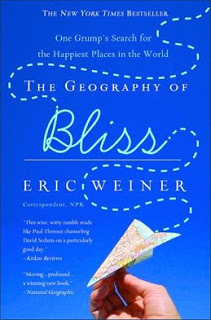

Whingers and Warm Guns: Happy-Guru Eric Weiner's Writing Life

What’s happiness? A large income, Jane Austen said. Absolute ignorance, according to the delightfully morbid Grahame Greene. Or John Lennon’s less delightfully morbid warm gun. Whatever else it is, happiness is done to death. But where it is? That’s something new. The genius of Eric Weiner’s New York Times bestseller “The Geography of Bliss: One Grump’s Search for the Happiest Places in the World” is to change the way of searching for happiness. Instead of looking for ways to make himself happy (the typically American individualistic approach to joy), he went out to find places where other people were happy. That way the former NPR correspondent (I got to know him when he was Mideast bureau chief, but he was based in India, too, for a time) was able to identify broader characteristics of a society that create happiness. He found, of course, that being Swiss helps (they trust everyone around them and therefore don’t have to worry and watch their backs). Being Moldovan on the other hand definitely doesn’t help -- everyone cheats, nothing's fair = miserable place. On his journey Eric also ditched email. But he broke that rule for the sake of my blog, and I’m glad he did.

How long did it take you to get published?

It took me three weeks to find an agent and publisher. It took twelve years for me to settle on an idea that I was passionate about.

Would you recommend any books on writing?

No. I think the best way to learn to write is to write. Reading (everything and anything) helps, too. So does coffee.

What’s a typical writing day?

I wake up bright and early, and by 8:00 a.m. settle into my office. Then I check my e-mail. Then I check Facebook. Then I check a few of my favorite blogs. Then I break for lunch. Usuallly, after lunch, I will do some actual writing before calling it a day.

Plug your latest book. What’s it about? Why’s it so great?

You're asking a writer to plug his own work? Okay, if you insist. My book, The Geography of Bliss, is brilliant because it takes a fairly tried subject, happiness, and gives it a new twist. Most happiness books focus on the what of happiness; I was interested in the where. Which are the world's happiest countries and what can we learn from them? And--did I mention?--the writing is brilliant! Funny and serious at the same time. I would highly recommend it. Really.

How much of what you do is:

a) formula dictated by the genre within which you write?

b) formula you developed yourself and stuck with?

c) as close to complete originality as it’s possible to get each time?

Mainly b), I think, with a smattering of c). My genre, broadly speaking, is travelogue. It is an odd, self-loathing genre. Many of the great travel writers don't like to be called travel writers. I think that's because travel writing sounds fluffy and inconsequential. At least bad travel writing is like that. Good travel writing is simply good writing that happens to use place as its main construct. In my work, I try to fashion a slightly new genre, the travelogue of ideas. In that sense, my book isn't really travel book at all. It's a book about the nature of happiness that uses geography as a way to get at this mystery.

Where is your favorite place to write?

I like coffee shops. The background din, oddly, helps me focus. After a while, though, I get antsy and feel the need to move. I might write in two or three different places in a single day. After all, I am a travel writer. Place matters.

Who is your favorite travel writer?

Jan Morris. She can get to the heart of a place in a few sentences. She is opinionated, but not obnoxiously so. She puts herself in her writing but never gets in the way of a good story. And she can be funny in all the right places.

What do you do if you are stuck?

I drink more coffee. If that doesn't work, (and it usually doesn't) I go for a walk. If that doesn't work (and it usually doesn't) I read what I have written aloud. I tend to write for the ear, and reading aloud can help me regain my rhythm. Also, I recently discovered a wine called "Writer's Block." It's a very nice Zinfandel.

What do you read for pleasure?

I like big fat books that tackle big fat topics. I'm currently reading Peter Watson's Ideas; A History of Thought and Invention from Fire to Freud. It's easily 800 pages. I'm still in the fire bit.

How much research is involved in each of your books?

An awful lot. For The Geography of Bliss, I read everything I could get my hands on about happiness, from Aristotle to Marty Seligmen, the poo-bah of the "science of happiness." I camped out at a university library for weeks on end. For a while, I was concerned that I was over-researching, but now I dont' think there is such a thing. Many morsels from my research made their way into the final manuscript.

What’s your experience with being translated?

My book has been translated into 13 languages, The publishers send me copies, which is nice. I can't understand a word of them,. for all I know they did a terrible job of translating. But they look nice on my bookshelf. Especially the Korean edition. Very colorful.

Do you live entirely off your writing?

I do make a living off my writing. I consider myself very fortunate.

How many books did you write before you were published?

This is my first one. Non-fiction, though, is a lot easier to get published than fiction.

What’s the strangest thing that happened to you on a book tour?

I had just completed an interview with a radio station in Portland, Oregon, when the interviewer said, "That was really great, Do you want to smoke some weed?" It's true. I might have taken him up on it, but I had a book reading in a couple of hours, so I politely declined.

What’s your weirdest idea for a book you’ll never get to publish?

I'd like to write a travel book about time travel. I would go back in time to an age when there still were undiscovered places to explore and write about them. I'd also buy some choice real estate in Manhattan. Then I'd travel back to the present and live large.

Published on June 10, 2009 01:11

•

Tags:

east, eric, happiness, interviews, journalism, life, literature, middle, nonfiction, weiner, writing

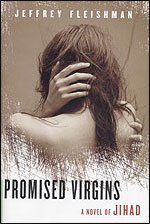

A living foreign correspondent the most useless thing to media industry -- Reviewing a "Novel of Jihad"

The magazine of Harvard's Nieman Fellowship asked me to write an essay about Jeffrey Fleishman's "Promised Virgins: A Novel of Jihad". I wrote about why international correspondents like me and Fleishman, Cairo bureau chief for the LA Times, turn to novels to express the depth of what we learn about a foreign culture. Here's how the article begins:

Jay Morgan, the central character of Jeffrey Fleishman’s thought provoking “novel of Jihad,” carries an undeveloped roll of film shot by his young photographer wife in the moments before she was killed in Beirut. Morgan lifts her wounded body to safety, but she dies anyway. It’s a fitting image on which to build Morgan’s deep bitterness and disillusion about journalism as he covers the war in Kosovo. In these days of cyberjournalism, idiotic reader “talkbacks” and nonsensical newsroom cutbacks, the only thing apparently more useless to the media industry than an undeveloped film or a dead photographer is a living foreign correspondent.

The story of “Promised Virgins” revolves around Morgan’s trek through the mountains as he interviews Serbs, Albanians and CIA operatives on the hunt for a newly arrived jihadi who has brought Islamic fundamentalism to the otherwise nationalistic Muslims of Kosovo. In truth, the book is about a foreign correspondent’s uncomfortable personal connections with the society he covers and his realization that they’re the only things keeping him from despair at his ever-shabbier trade. Read more...

Published on June 13, 2009 23:59

•

Tags:

balkans, bethlehem, collaborator, crime, east, fiction, islam, jihadi, journalism, kosovo, literature, middle, murders, religion, thrillers

Thriller Bugbear #69: Plot-Point Techno Madness!

Much as I love Nordic crime fiction, the Europewide megaseller “The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo” by Stieg Larsson made me want to throw knives like the Swedish chef on The Muppet Show. Why?

Two reasons.

First, the minor reason. Written by a (tragically deceased) Swedish journalist, the book is entirely in the style of a magazine article. Complete with page after page of “research.” It’d be enough for the author to tell me that Swedish women are often assaulted by men. I don’t need five pages of real background. A writer ought to understand that the greater the temptation for the reader to skim, the worse the book is. You end up with a good 250 page mystery trapped inside a 600 page monster.

Overloading with journalistic background is a common technique in contemporary thrillers and mysteries. It’s as though making things up was somehow a distortion of reality. Whereas it actually gets you a lot closer to reality than journalism or journalistic techniques, because it opens up the reader emotionally. (That’s what I’ve found with my Palestinian detective series.)

Second, the major reason. The Internet.

In “Dragon Tattoo,” the eponymous heroine is the now generic thriller/mystery character: the Internet hacker genius. Whenever Larsson needs to inject some new information or to unravel a tricky plot point, his hacker opens up her laptop and links into www.secretgovernmentinformation.com, the well-known (to fiction writers) site where all governments, in particular their intelligence networks, store material they want to be sure is available only to fictional hacker geniuses (and by proxy to thriller writers).

“Dragon Tattoo” isn’t the worst offender. Just the biggest seller.

But I’m only naming names here because poor old Larsson is dead. Those (here unnamed) living writers who use this technique ought to be ashamed of themselves.

In my novels the only time the Internet comes up is when detective Omar Yussef’s granddaughter sets up a website for him in her attempt to make him seem more professional. “The Palestine Agency for Detection,” as she calls her site, is merely embarrassing to Omar. No plot-point-shifting Houdini act there.

The Internet has essentially taken over from the Mossad as the thriller writer’s cure-all. In the old days, if there was something your main character couldn’t figure out, all he had to do was get in touch with the nearest Mossad agent, who’d be sure to know all the secrets in the world and was happy to pass them on with a few dark words about never forgetting the Holocaust and a cheerful “Shalom.”

As a resident of Israel, I can tell you the Mossad doesn’t operate that way. Neither does the Internet.

So stop writing books that pretend it does. (I wonder how you say that in Swedish...)

Two reasons.

First, the minor reason. Written by a (tragically deceased) Swedish journalist, the book is entirely in the style of a magazine article. Complete with page after page of “research.” It’d be enough for the author to tell me that Swedish women are often assaulted by men. I don’t need five pages of real background. A writer ought to understand that the greater the temptation for the reader to skim, the worse the book is. You end up with a good 250 page mystery trapped inside a 600 page monster.

Overloading with journalistic background is a common technique in contemporary thrillers and mysteries. It’s as though making things up was somehow a distortion of reality. Whereas it actually gets you a lot closer to reality than journalism or journalistic techniques, because it opens up the reader emotionally. (That’s what I’ve found with my Palestinian detective series.)

Second, the major reason. The Internet.

In “Dragon Tattoo,” the eponymous heroine is the now generic thriller/mystery character: the Internet hacker genius. Whenever Larsson needs to inject some new information or to unravel a tricky plot point, his hacker opens up her laptop and links into www.secretgovernmentinformation.com, the well-known (to fiction writers) site where all governments, in particular their intelligence networks, store material they want to be sure is available only to fictional hacker geniuses (and by proxy to thriller writers).

“Dragon Tattoo” isn’t the worst offender. Just the biggest seller.

But I’m only naming names here because poor old Larsson is dead. Those (here unnamed) living writers who use this technique ought to be ashamed of themselves.

In my novels the only time the Internet comes up is when detective Omar Yussef’s granddaughter sets up a website for him in her attempt to make him seem more professional. “The Palestine Agency for Detection,” as she calls her site, is merely embarrassing to Omar. No plot-point-shifting Houdini act there.

The Internet has essentially taken over from the Mossad as the thriller writer’s cure-all. In the old days, if there was something your main character couldn’t figure out, all he had to do was get in touch with the nearest Mossad agent, who’d be sure to know all the secrets in the world and was happy to pass them on with a few dark words about never forgetting the Holocaust and a cheerful “Shalom.”

As a resident of Israel, I can tell you the Mossad doesn’t operate that way. Neither does the Internet.

So stop writing books that pretend it does. (I wonder how you say that in Swedish...)

Stranger than zinc bars and literary fiction

Foreign correspondents are always more enthusiastic about Beirut than about Amman. Just like critics prefer “literary” fiction to crime novels.

It seems to me they’re both wrong, and for the same reasons.

Visiting reporters always rave about Beirut. Mainly because there’s a very un-Middle Eastern nightlife there. Zinc bars. Beautiful girls in spaghetti-strap tops beside the zinc bars. Booze, dance clubs, DJs.

They’re not really interested in the broken-down refugee camps or the ride up into the Shouf Mountains or the remnants of wars, bulletholes dug into the walls of buildings both inhabited and abandoned. It’s the zinc bars, that’s all. The things that are just like home.

But Amman. It’s “boring,” because despite its size it’s somehow still a big Bedouin encampment. Slow and formal.

Foreign, in fact.

Turns out, foreign correspondents aren’t so interested in “foreign” places. That’s why they like the bars, zinc or otherwise, at their hotels.

Amman has an astonishing history. It was one of the 10 Roman cities of the region – the original Philadelphia, according to its ancient name. The oldest parts of town down in the valley between the hills where the wealthier people live aren’t picturesque in the way central Damascus is. But they’re teeming with life and with conflicts and with striving – Palestinian refugees, Iraqi refugees, Syrian migrant workers.

No nightlife, though. When old King Hussein was dieing, hundreds of foreign correspondents were forced to endure nights at the Hard Rock Café (since closed) where the highlight was the Village People’s “YMCA”, danced by a staff which was not always familiar with the moves. Probably they didn’t read the Western alphabet, so they had no idea why two arms in the air had to go along with “Y” or why you had to dip to the side to make a “C.”

Having lived away from the country of my birth my entire adult life, I don’t see how anyone can say that any foreign city is boring. The culture will always be different to the one you’re familiar with. Understanding how people think in a world different to your own is the most fascinating thing.

But people prefer the zinc bar, and that’s often true of books, too.

Some genre fiction is not “foreign” enough. I don’t mean that the location has to be overseas, as in my Palestinian crime series. I mean that the subject it tackles or the way of examining the actions of the characters needs to have the challenging, uncomfortable quality of an alien culture.

A book ought to be like a visit to a foreign place, even if it’s set in your own town. Genre doesn’t matter. The way a writer answers this challenge is what makes a book good or bad.

There are cheap ways of engaging readers on this level, and then there are genuine ways.

You might think at first that so-called “genre” fiction would be less foreign, because of the apparent comfort of formula. (For a "formula is cosy and therefore any idiot can read it" appraisal, see The New Yorker's article this week on Nora Roberts.) But it's not so.

Take my Palestinian crime novels. Everything that’s written about Palestinians makes me cringe or toss it aside in boredom. Because “literary” authors like Robert Stone (“Damascus Gate”) find themselves writing about a false construct, an image of the Palestinians or of Jerusalem. They see the people and places of the region only in ways that others have seen them before.

I took the real Palestinians and stories I’d covered as a journalist, shook them out of the stable formula in which they usually appeared in the newspapers, and made them strange, which in turn made them visible in a new way. (For those lit. crit. fans out there, I cite Viktor Shklovsky, Russian formalist, “ostranenie,” art brings about the perception of a thing, rather than creating the thing itself.)

So visit Amman, instead of Beirut. And on the way over, read my Palestinian novels.

It seems to me they’re both wrong, and for the same reasons.

Visiting reporters always rave about Beirut. Mainly because there’s a very un-Middle Eastern nightlife there. Zinc bars. Beautiful girls in spaghetti-strap tops beside the zinc bars. Booze, dance clubs, DJs.

They’re not really interested in the broken-down refugee camps or the ride up into the Shouf Mountains or the remnants of wars, bulletholes dug into the walls of buildings both inhabited and abandoned. It’s the zinc bars, that’s all. The things that are just like home.

But Amman. It’s “boring,” because despite its size it’s somehow still a big Bedouin encampment. Slow and formal.

Foreign, in fact.

Turns out, foreign correspondents aren’t so interested in “foreign” places. That’s why they like the bars, zinc or otherwise, at their hotels.

Amman has an astonishing history. It was one of the 10 Roman cities of the region – the original Philadelphia, according to its ancient name. The oldest parts of town down in the valley between the hills where the wealthier people live aren’t picturesque in the way central Damascus is. But they’re teeming with life and with conflicts and with striving – Palestinian refugees, Iraqi refugees, Syrian migrant workers.

No nightlife, though. When old King Hussein was dieing, hundreds of foreign correspondents were forced to endure nights at the Hard Rock Café (since closed) where the highlight was the Village People’s “YMCA”, danced by a staff which was not always familiar with the moves. Probably they didn’t read the Western alphabet, so they had no idea why two arms in the air had to go along with “Y” or why you had to dip to the side to make a “C.”

Having lived away from the country of my birth my entire adult life, I don’t see how anyone can say that any foreign city is boring. The culture will always be different to the one you’re familiar with. Understanding how people think in a world different to your own is the most fascinating thing.

But people prefer the zinc bar, and that’s often true of books, too.

Some genre fiction is not “foreign” enough. I don’t mean that the location has to be overseas, as in my Palestinian crime series. I mean that the subject it tackles or the way of examining the actions of the characters needs to have the challenging, uncomfortable quality of an alien culture.

A book ought to be like a visit to a foreign place, even if it’s set in your own town. Genre doesn’t matter. The way a writer answers this challenge is what makes a book good or bad.

There are cheap ways of engaging readers on this level, and then there are genuine ways.

You might think at first that so-called “genre” fiction would be less foreign, because of the apparent comfort of formula. (For a "formula is cosy and therefore any idiot can read it" appraisal, see The New Yorker's article this week on Nora Roberts.) But it's not so.

Take my Palestinian crime novels. Everything that’s written about Palestinians makes me cringe or toss it aside in boredom. Because “literary” authors like Robert Stone (“Damascus Gate”) find themselves writing about a false construct, an image of the Palestinians or of Jerusalem. They see the people and places of the region only in ways that others have seen them before.

I took the real Palestinians and stories I’d covered as a journalist, shook them out of the stable formula in which they usually appeared in the newspapers, and made them strange, which in turn made them visible in a new way. (For those lit. crit. fans out there, I cite Viktor Shklovsky, Russian formalist, “ostranenie,” art brings about the perception of a thing, rather than creating the thing itself.)

So visit Amman, instead of Beirut. And on the way over, read my Palestinian novels.

The most obscure band in Jerusalem

I bet you didn't know there was an underground scene in Jerusalem (at least not an underground music scene; you've probably heard of some other undergrounds that operate here). Here's a little bit of Middle East insider poop for you: what's the most obscure underground band in Jerusalem?

Answer: Dolly Weinstein.

A fivesome (formerly a sixsome, sometimes foursome) of folk rock and rock standards, featuring yours truly on bass.

Other writers are notable for playing in not very good rock bands -- Stephen King, Amy Tan, and Dave Barry, for example, in the Rock Bottom Remainders (too many people on stage, always makes me think of Live Aid and horrible things like that -- not very "underground" at all). But which of them can say they've played in a basement bar under a dreary 1970s tower block in the center of Jerusalem? Or that they'll be the opening act at a Woodstock tribute concert in a football stadium in Jerusalem on August 6?

So here's Dolly Weinstein in action. A 56-second clip on Youtube.

There it is. Fifty-six seconds of underground Jerusalem. That's about what it's worth.

Answer: Dolly Weinstein.

A fivesome (formerly a sixsome, sometimes foursome) of folk rock and rock standards, featuring yours truly on bass.

Other writers are notable for playing in not very good rock bands -- Stephen King, Amy Tan, and Dave Barry, for example, in the Rock Bottom Remainders (too many people on stage, always makes me think of Live Aid and horrible things like that -- not very "underground" at all). But which of them can say they've played in a basement bar under a dreary 1970s tower block in the center of Jerusalem? Or that they'll be the opening act at a Woodstock tribute concert in a football stadium in Jerusalem on August 6?

So here's Dolly Weinstein in action. A 56-second clip on Youtube.

There it is. Fifty-six seconds of underground Jerusalem. That's about what it's worth.

Published on June 25, 2009 23:38

•

Tags:

amy, appearances, barry, bottom, dave, dolly, east, jerusalem, king, literature, middle, music, remainders, rock, stephen, tan, underground, weinstein

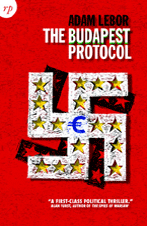

Culture and harshness in Central Europe: Adam Lebor's Writing Life

Political writing at its best highlights the unexpected changes in parts of our world that are hidden to us. That’s true of writing about the corridors of power in our own capital cities, but it’s even more of a factor for a writer like Adam Lebor whose work – fiction and nonfiction – has captured the dynamism and double-dealing of Central Europe, in particular. Because I live in the Middle East while he lives in Budapest, Lebor first came to my attention with his wonderful “biography” of Jaffa, the ancient port city on the Mediterranean coast, “City of Oranges: Arabs and Jews in Jaffa.” It was a masterful stroke to profile this town, rather than Jerusalem or even Tel Aviv, which tend to attract the attention of writers more readily than a historic city that’s now a slum filling with liberal yuppies. It shouldn’t have surprised me, then, that Lebor’s new novel The Budapest Protocol, which I reviewed recently, would take an issue that many think of as boring and bureaucratic – the expansion of the European Union – and make it immediate and vital, linking it to the demons of Europe’s past through Nazism and genocide. The novel is firmly in the tradition of great British writers like Eric Ambler, Graham Greene, and John LeCarre. Like them, Lebor knows that Central Europe’s cultured side comes with an accompanying harshness that makes for great drama.

How long did it take you to get published?

My first non-fiction book, ‘A Heart Turned East’, about Muslim minorities in Europe and the United States, was published in 1998 by Little, Brown, UK. It was commissioned so was published a few months after I wrote it. That was a fairly straightforward process. Since then I have written another five non-fiction books, all of which were commissioned.

Fiction, however, was a very different story. I first started writing the book that would become The Budapest Protocol in Paris in the winter of 1997. It was rejected by numerous publishers before I finally found one, Reportage Press, that would actually spend the time to tell me how to fix it. I always knew I needed the attention of a good editor, but apparently most publishers nowadays expect a perfectly formed novel to land on their desks, which is ridiculous.

Would you recommend any books on writing?

A search on amazon.co.uk for ‘writing a novel’ brings up 20,625 results. Most of the authors of these books are not well know novelists, because successful novelists are writing novels, not books about how to. That said, I have found ‘The First Five Pages’, by Noah Lukeman, very useful. Lukeman is a well-known American agent, and the book is full of good advice, from a commercial viewpoint. I would recommend it for anyone who is serious about getting published. I also like ‘Writing A Novel’ by John Osborne, which is enjoyably cantankerous but full of good advice.

What’s a typical writing day?

Breakfast with the Today programme on my Evoke internet radio, invaluable for keeping in touch when you live abroad - I am based in Budapest. Spend morning probably doing journalism or admin. Usually the muse arrives after lunch, and a good writing session will go from about 3pm to nine or ten at night. If it’s really flowing I will wake up in the morning with a plot solved or idea for a chapter plan that somehow my subconscious has sorted out while I am asleep and then I am straight back in the book.

Plug your latest book. What’s it about? Why’s it so great?

The Budapest Protocol is a conspiracy thriller that was inspired by a real American intelligence document from 1944. The document, known as the Red House Report, is an account of a secret meeting of Nazi industrialists in the Maison Rouge hotel, Strasbourg, where they planned for the Fourth Reich, which would be an economic imperium not a military one. That was the inspiration - I then used my twenty years reporting experience in eastern Europe to work out how that might actually happen. There is also a love story with several sexy, difficult girls and atmospheric scene setting in present day Budapest.

How much of what you do is formula dictated by the genre within which you write?

Thrillers are to some extent quite formulaic. The hero needs inner conflict to drive his outer battle with larger sinister forces. He needs to face and overcome repeated obstacles, each time getting in more and more danger. The trick is use the formula to make the structure work while making the setting, atmosphere and narrative drive powerful enough. Alan Furst, the master, gave me some advice: “Start with a murder and make sure the boy gets the girl” which was very useful.

What’s your favorite sentence in all literature, and why?

“Heshel was watching him through the window of the car and smiled thinly as their eyes met. Here is the world, said the smile, and here we are in it.” A line from my favorite book, Dark Star, by Alan Furst. Dark Star is an espionage thriller set in late 1930s Europe. That sentence is subtle, telling, and somehow opens a world of the imagination.

What’s the best descriptive image in all literature?

It was a bright cold day in April and the clocks were striking thirteen.

Who’s the greatest stylist currently writing?

Alan Furst. Less is more.

Who’s the greatest plotter currently writing?

David Ignatius, author of Body of Lies and The Increment. I would also add Stieg Larson, who sadly is not writing any more.

How much research is involved in each of your books?

The Budapest Protocol did not demand any specific research as I have covered this region for twenty years. My non-fiction books, like ‘City of Oranges: Arabs and Jews in Jaffa’ about Jewish and Arab families in the ancient port demanded many weeks of research, hours of interviews and gaining the trust of the families.

Where’d you get the idea for your main character?

The fact that he is a foreign correspondent, who lives in Budapest, who is obsessed with sinister conspiracies and who is entangled with beguiling but unsuitable women and whose first name is four letters beginning with ‘A’ is entirely coincidental.

What’s your experience with being translated?

Fine. I have been translated into eight languages, but I don’t really check what they have done to the book, even in languages I know.

Do you live entirely off your writing? How many books did you write before could make a living at it?

Now, yes. But that is combined with journalism for big papers like The Times, Economist etc. I think it would be very difficult just to live off books, and I like the change of pace with journalism. I value my connection with The Times, it opens doors and my assignments give me ideas for books and characters.

What’s the strangest thing that happened to you on a book tour?

I suppose it’s probably not that strange and happens to other authors but I was amazed that after two sell out events at the Edinburgh book festival with about 180 people in the room I only sold a handful of books. Why pay eight pounds to watch the author when you can buy the book for that?

What’s your weirdest idea for a book you’ll never get to publish?

I cannot reveal that as it’s such a good idea it may yet hit the shelves one day!

Ingenious book readings: Just don't mention books!

In his terrific book "On Writing" Stephen King notes that he once asked Amy Tan what she's NEVER asked about at public readings. "They never ask about the writing," Tan tells him. Which spurs King to write a book about exactly that.

Now controversial UK publishing guru Scott Pack goes one better. Public appearances by writers. With no readings. And no questions about...books.

The idea, as Scott explains here, is to get writers talking about their life and interests outside their books. Ultimately of course I think that'll take them back to their books. But it's a great way to refresh the rather tired world of literary events. For more on Scott's plan, look at his blog.

Published on July 12, 2009 01:13

•

Tags:

blogs, book, fiction, king, literature, publishing, readings, stephen, tour

Elmore Leonard's 11th Rule of Writing

I’ve always enjoyed Elmore Leonard’s novels and seen him as one of the true stylists of popular fiction. In a review, I even described my pal Christopher G. Moore as the “Elmore Leonard of Bangkok” and I meant it as a compliment. But I have a bone to pick with the great Elmore.

I just read a book of Elmore’s short stories from 2004 titled “When the Women Come Out to Dance.” In many ways it’s superb. The title story turns on the particularly American kind of hardness and determination that takes a character who is not bad into a situation that leaves them ineradicably among bad people.

So what’s the problem? Movie stars, that's what.

In one of the early stories in the book, a character is described as being a “Jill St. John type.” I looked her up. She doesn’t appear to have had a major movie role for about 28 years before Elmore wrote the story, but I suppose her bikini-clad appearance in an ancient Bond film made an impression on him.

In two – not one, but two – of the later stories in the book, there’s a character who’s described as looking like (or smiling like) Jack Nicholson.

This isn’t the work of a great stylist. This is on the level of Dan Brown. (Remember that in The Da Vinci Code, Brown’s hero, the dumbest professor Harvard ever employed, is described thus: “He looked like Harrison Ford.” I wonder if, after the movie came out, later editions updated that to “…He looked like Tom Hanks.”)

This would be a cheap technique if a journalist used it. For a writer with the descriptive powers of Elmore, it’s a real shame.

In his famous 10 Rules of Writing, Elmore says: “Avoid detailed descriptions of characters.” That’s probably why he didn’t write “He looked like Jack Nicholson in ‘The Shining’ in the scene where he’s coming through the door with the axe and shouting ‘Here’s Johnny’ with a demented enjoyment on his face.” Too much detail.

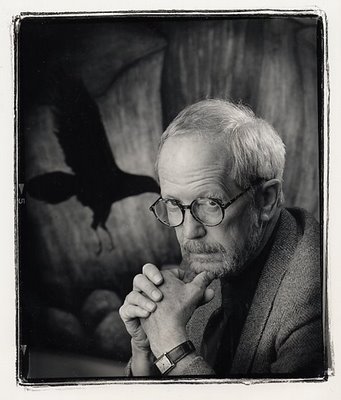

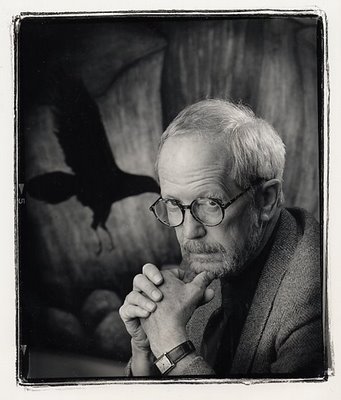

Well, if you were trying to describe Elmore, how would you do it? Here’s his picture. I could describe him as “looking like Roger Whittaker.” Mean anything to you? Perhaps you don’t recall much about British easy-listening music of the 1970s. If you did, you’d have a picture. But why should you?

That’s exactly why I don’t like to see Elmore describe a character as looking like a particular movie star.

That doesn’t mean Elmore’s style should be discounted. (Read his 10 rules below. They’re very good in a folksy American sort of way.) But let’s first add an 11th rule: Don’t describe characters as looking like a particular movie star.

Elmore Leonard's Ten Rules of Writing

These are rules I’ve picked up along the way to help me remain invisible when I’m writing a book, to help me show rather than tell what’s taking place in the story. If you have a facility for language and imagery and the sound of your voice pleases you, invisibility is not what you are after, and you can skip the rules. Still, you might look them over.

1. Never open a book with weather. If it’s only to create atmosphere, and not a character’s reaction to the weather, you don’t want to go on too long. The reader is apt to leaf ahead looking for people. There are exceptions. If you happen to be Barry Lopez, who has more ways to describe ice and snow than an Eskimo, you can do all the weather reporting you want.

2. Avoid prologues.

They can be annoying, especially a prologue following an introduction that comes after a foreword. But these are ordinarily found in nonfiction. A prologue in a novel is backstory, and you can drop it in anywhere you want.

There is a prologue in John Steinbeck’s “Sweet Thursday,” but it’s O.K. because a character in the book makes the point of what my rules are all about. He says: “I like a lot of talk in a book and I don’t like to have nobody tell me what the guy that’s talking looks like. I want to figure out what he looks like from the way he talks. . . . figure out what the guy’s thinking from what he says. I like some description but not too much of that. . . . Sometimes I want a book to break loose with a bunch of hooptedoodle. . . . Spin up some pretty words maybe or sing a little song with language. That’s nice. But I wish it was set aside so I don’t have to read it. I don’t want hooptedoodle to get mixed up with the story.”

3. Never use a verb other than “said” to carry dialogue.

The line of dialogue belongs to the character; the verb is the writer sticking his nose in. But said is far less intrusive than grumbled, gasped, cautioned, lied. I once noticed Mary McCarthy ending a line of dialogue with “she asseverated,” and had to stop reading to get the dictionary.

4. Never use an adverb to modify the verb “said” . . .

. . . he admonished gravely. To use an adverb this way (or almost any way) is a mortal sin. The writer is now exposing himself in earnest, using a word that distracts and can interrupt the rhythm of the exchange. I have a character in one of my books tell how she used to write historical romances “full of rape and adverbs.”

5. Keep your exclamation points under control.

You are allowed no more than two or three per 100,000 words of prose. If you have the knack of playing with exclaimers the way Tom Wolfe does, you can throw them in by the handful.

6. Never use the words “suddenly” or “all hell broke loose.”

This rule doesn’t require an explanation. I have noticed that writers who use “suddenly” tend to exercise less control in the application of exclamation points.

7. Use regional dialect, patois, sparingly.

Once you start spelling words in dialogue phonetically and loading the page with apostrophes, you won’t be able to stop. Notice the way Annie Proulx captures the flavor of Wyoming voices in her book of short stories “Close Range.”

8. Avoid detailed descriptions of characters.

Which Steinbeck covered. In Ernest Hemingway’s “Hills Like White Elephants” what do the “American and the girl with him” look like? “She had taken off her hat and put it on the table.” That’s the only reference to a physical description in the story, and yet we see the couple and know them by their tones of voice, with not one adverb in sight.

9. Don’t go into great detail describing places and things.

Unless you’re Margaret Atwood and can paint scenes with language or write landscapes in the style of Jim Harrison. But even if you’re good at it, you don’t want descriptions that bring the action, the flow of the story, to a standstill.

And finally:

10. Try to leave out the part that readers tend to skip.

A rule that came to mind in 1983. Think of what you skip reading a novel: thick paragraphs of prose you can see have too many words in them. What the writer is doing, he’s writing, perpetrating hooptedoodle, perhaps taking another shot at the weather, or has gone into the character’s head, and the reader either knows what the guy’s thinking or doesn’t care. I’ll bet you don’t skip dialogue.

My most important rule is one that sums up the 10.

If it sounds like writing, I rewrite it.

Or, if proper usage gets in the way, it may have to go. I can’t allow what we learned in English composition to disrupt the sound and rhythm of the narrative. It’s my attempt to remain invisible, not distract the reader from the story with obvious writing. (Joseph Conrad said something about words getting in the way of what you want to say.)

If I write in scenes and always from the point of view of a particular character—the one whose view best brings the scene to life—I’m able to concentrate on the voices of the characters telling you who they are and how they feel about what they see and what’s going on, and I’m nowhere in sight.

What Steinbeck did in “Sweet Thursday” was title his chapters as an indication, though obscure, of what they cover. “Whom the Gods Love They Drive Nuts” is one, “Lousy Wednesday” another. The third chapter is titled “Hooptedoodle 1” and the 38th chapter “Hooptedoodle 2” as warnings to the reader, as if Steinbeck is saying: “Here’s where you’ll see me taking flights of fancy with my writing, and it won’t get in the way of the story. Skip them if you want.”

“Sweet Thursday” came out in 1954, when I was just beginning to be published, and I’ve never forgotten that prologue.

Did I read the hooptedoodle chapters? Every word.

I just read a book of Elmore’s short stories from 2004 titled “When the Women Come Out to Dance.” In many ways it’s superb. The title story turns on the particularly American kind of hardness and determination that takes a character who is not bad into a situation that leaves them ineradicably among bad people.

So what’s the problem? Movie stars, that's what.

In one of the early stories in the book, a character is described as being a “Jill St. John type.” I looked her up. She doesn’t appear to have had a major movie role for about 28 years before Elmore wrote the story, but I suppose her bikini-clad appearance in an ancient Bond film made an impression on him.

In two – not one, but two – of the later stories in the book, there’s a character who’s described as looking like (or smiling like) Jack Nicholson.

This isn’t the work of a great stylist. This is on the level of Dan Brown. (Remember that in The Da Vinci Code, Brown’s hero, the dumbest professor Harvard ever employed, is described thus: “He looked like Harrison Ford.” I wonder if, after the movie came out, later editions updated that to “…He looked like Tom Hanks.”)

This would be a cheap technique if a journalist used it. For a writer with the descriptive powers of Elmore, it’s a real shame.

In his famous 10 Rules of Writing, Elmore says: “Avoid detailed descriptions of characters.” That’s probably why he didn’t write “He looked like Jack Nicholson in ‘The Shining’ in the scene where he’s coming through the door with the axe and shouting ‘Here’s Johnny’ with a demented enjoyment on his face.” Too much detail.

Well, if you were trying to describe Elmore, how would you do it? Here’s his picture. I could describe him as “looking like Roger Whittaker.” Mean anything to you? Perhaps you don’t recall much about British easy-listening music of the 1970s. If you did, you’d have a picture. But why should you?

That’s exactly why I don’t like to see Elmore describe a character as looking like a particular movie star.

That doesn’t mean Elmore’s style should be discounted. (Read his 10 rules below. They’re very good in a folksy American sort of way.) But let’s first add an 11th rule: Don’t describe characters as looking like a particular movie star.

Elmore Leonard's Ten Rules of Writing

These are rules I’ve picked up along the way to help me remain invisible when I’m writing a book, to help me show rather than tell what’s taking place in the story. If you have a facility for language and imagery and the sound of your voice pleases you, invisibility is not what you are after, and you can skip the rules. Still, you might look them over.

1. Never open a book with weather. If it’s only to create atmosphere, and not a character’s reaction to the weather, you don’t want to go on too long. The reader is apt to leaf ahead looking for people. There are exceptions. If you happen to be Barry Lopez, who has more ways to describe ice and snow than an Eskimo, you can do all the weather reporting you want.

2. Avoid prologues.

They can be annoying, especially a prologue following an introduction that comes after a foreword. But these are ordinarily found in nonfiction. A prologue in a novel is backstory, and you can drop it in anywhere you want.

There is a prologue in John Steinbeck’s “Sweet Thursday,” but it’s O.K. because a character in the book makes the point of what my rules are all about. He says: “I like a lot of talk in a book and I don’t like to have nobody tell me what the guy that’s talking looks like. I want to figure out what he looks like from the way he talks. . . . figure out what the guy’s thinking from what he says. I like some description but not too much of that. . . . Sometimes I want a book to break loose with a bunch of hooptedoodle. . . . Spin up some pretty words maybe or sing a little song with language. That’s nice. But I wish it was set aside so I don’t have to read it. I don’t want hooptedoodle to get mixed up with the story.”

3. Never use a verb other than “said” to carry dialogue.

The line of dialogue belongs to the character; the verb is the writer sticking his nose in. But said is far less intrusive than grumbled, gasped, cautioned, lied. I once noticed Mary McCarthy ending a line of dialogue with “she asseverated,” and had to stop reading to get the dictionary.

4. Never use an adverb to modify the verb “said” . . .

. . . he admonished gravely. To use an adverb this way (or almost any way) is a mortal sin. The writer is now exposing himself in earnest, using a word that distracts and can interrupt the rhythm of the exchange. I have a character in one of my books tell how she used to write historical romances “full of rape and adverbs.”

5. Keep your exclamation points under control.

You are allowed no more than two or three per 100,000 words of prose. If you have the knack of playing with exclaimers the way Tom Wolfe does, you can throw them in by the handful.

6. Never use the words “suddenly” or “all hell broke loose.”

This rule doesn’t require an explanation. I have noticed that writers who use “suddenly” tend to exercise less control in the application of exclamation points.

7. Use regional dialect, patois, sparingly.

Once you start spelling words in dialogue phonetically and loading the page with apostrophes, you won’t be able to stop. Notice the way Annie Proulx captures the flavor of Wyoming voices in her book of short stories “Close Range.”

8. Avoid detailed descriptions of characters.

Which Steinbeck covered. In Ernest Hemingway’s “Hills Like White Elephants” what do the “American and the girl with him” look like? “She had taken off her hat and put it on the table.” That’s the only reference to a physical description in the story, and yet we see the couple and know them by their tones of voice, with not one adverb in sight.

9. Don’t go into great detail describing places and things.

Unless you’re Margaret Atwood and can paint scenes with language or write landscapes in the style of Jim Harrison. But even if you’re good at it, you don’t want descriptions that bring the action, the flow of the story, to a standstill.

And finally:

10. Try to leave out the part that readers tend to skip.

A rule that came to mind in 1983. Think of what you skip reading a novel: thick paragraphs of prose you can see have too many words in them. What the writer is doing, he’s writing, perpetrating hooptedoodle, perhaps taking another shot at the weather, or has gone into the character’s head, and the reader either knows what the guy’s thinking or doesn’t care. I’ll bet you don’t skip dialogue.

My most important rule is one that sums up the 10.

If it sounds like writing, I rewrite it.

Or, if proper usage gets in the way, it may have to go. I can’t allow what we learned in English composition to disrupt the sound and rhythm of the narrative. It’s my attempt to remain invisible, not distract the reader from the story with obvious writing. (Joseph Conrad said something about words getting in the way of what you want to say.)

If I write in scenes and always from the point of view of a particular character—the one whose view best brings the scene to life—I’m able to concentrate on the voices of the characters telling you who they are and how they feel about what they see and what’s going on, and I’m nowhere in sight.

What Steinbeck did in “Sweet Thursday” was title his chapters as an indication, though obscure, of what they cover. “Whom the Gods Love They Drive Nuts” is one, “Lousy Wednesday” another. The third chapter is titled “Hooptedoodle 1” and the 38th chapter “Hooptedoodle 2” as warnings to the reader, as if Steinbeck is saying: “Here’s where you’ll see me taking flights of fancy with my writing, and it won’t get in the way of the story. Skip them if you want.”

“Sweet Thursday” came out in 1954, when I was just beginning to be published, and I’ve never forgotten that prologue.

Did I read the hooptedoodle chapters? Every word.

Poetry from the ‘driest’ book of the Bible: Yakov Azriel’s Writing Life

A few years ago I was at a literary conference near Tel Aviv. I found an eclectic mix of writers on the panel with me. I’m a crime writer. You wouldn’t expect me to be paired with a writer of poetry who takes his inspiration from the stories of the Bible. But as Yakov Azriel read his poetry, I sat beside him feeling that no contemporary poems had ever touched me as deeply. They’re full of the knowledge of the Bible the Brooklyn-born poet garnered during his studies at Israeli yeshivas and his four decades living here. There’s something else though: they bring to life the hills and desert around Jerusalem. To an outsider, it can often seem strange that so many people are attached to a place that’s stark and rather ugly and certainly not a nurturing environment for sustaining human life. With Yakov’s poems I think you’ll find a sense of what the place means. Here’s his interview, followed by a wonderful poem from his newest book.

How long did it take you to get published?

It took a few years of submitting my first manuscript of poetry to different publishers until my first book of poetry was published.

What’s a typical writing day?

I make a living by working as a teacher, so during the daytime I do not have the opportunity to write. I usually try to write in the evenings and at night (especially at night); I try to write one new poem a week.

Plug your latest book. What’s it about? Why’s it so great?

My latest book is entitled Beads for the Messiah's Bride: Poems on Leviticus, and it was published in June by Time Being Books (a literary press specializing in poetry). Like my two previous books of poetry (Threads From A Coat Of Many Colors: Poems On Genesis and In The Shadow Of A Burning Bush: Poems On Exodus, each poem in the book begins with a Biblical verse and the book is structured as a running commentary, starting with chapter 1, verse 1 and ending with the last Biblical chapter.

This book was challenging for several reasons. My first book focused on the different characters in Genesis, and I especially tried to focus on the gaps in the Biblical narrative (for example, who was Abraham's mother?) or to give a voice to figures who are silent in the Biblical text (such as Dinah, or Joseph's wife Asenat). In the poems on Exodus, the many events in the Biblical narrative itself (the enslavement in Egypt, the Ten Plagues, Passover, the splitting of the Red Sea, etc.) readily lent themselves to poetry.

In contrast, the Book of Leviticus is considered to be "drier," without the drama and large cast of characters of the first two books of the Bible. One device I used in order to grapple with this difficulty was a conscious effort to fuse the English literary tradition with the Jewish-Hebrew heritage. For example, the first chapters of Leviticus deal with sacrifices; I decided to write a Petrarchan sonnet for each sacrifice, a sonnet that is a prayer, modeled after the "Holy Sonnets" of John Donne. In the end, one book reviewer felt that this book was the most powerful of my three published books (eventually, we will be publishing five volumes of poetry, one for each of the Five Books of Moses).

How much of what you do is:

a) formula dictated by the genre within which you write?

b) formula you developed yourself and stuck with?

c) as close to complete originality as it’s possible to get each time?

I write poetry in all forms: mainly free verse (like most 21st century poets), but also formal, metric poems — sonnets, sestinas, villanelles, ballads, etc. Each poem has a life of its own, and it is the poet's duty to help each poem find its own voice. Just as a sculptor has to liberate the statue that is hidden in a block of marble, so the poet has to liberate the poem hidden on the empty page and grant it breath.

As I said, all my poems are based on the Bible. The Biblical verse is like an iceberg, with 90 % of its meaning under the surface; my job is to try to get under the surface.

T.S. Eliot said that there is little good religious poetry being written today because the religious poet tends to write what he thinks he ought to feel instead of what he really feels. All good poetry must be sincere. So part of my task as a poet is to be sincere, as much as possible.

What’s your favorite sentence in all literature, and why?

This is a very difficult question to answer! One sentence that really resonates for me in English literature is when Hamlet describes his father to Horatio in Act I, Scene II, and tells him that "He was a man." What a wonderful example of praise, love and understatement in four simple words.

In Biblical literature, one sentence that that I find very powerful occurs right after the scene in which the prophet Nathan tells King David the parable of the poor man's lamb (First Samuel, Chapter 12) and King David, incensed, says that this man deserves to die; after Nathan exclaims, "You are the man," David does not argue but admits, "I have sinned."

What’s the best descriptive image in all literature?

Again this is very difficult to answer, but I think that Dicken's description in Little Dorrit of the banquet scene in Rome in which Mr. Dorrit relives the past he has been trying so hard to conceal, and calls out loud to Amy, speaking about the turnkey and his imprisonment in the Marshalsea prison — this is certainly one of them.

How much research is involved in each of your books?

I have been "researching" my books all my life.

Where do you get your ideas?

This is a very good question. Often in the middle of the night an idea comes; I have to write it down, and the following evening, I work on it.

Do you have a pain from childhood that compels you to write? If not, what does?

No, I do not think that it stems from a childhood pain. Why do I write? Ask me why I breathe. The great German poet Rilke said that no one should write poetry unless he would have to die if it were denied him to write. Perhaps this is too strong (for me at least) but I cannot imagine a life for myself without writing.

What’s your experience with being translated?

I have translated several of my poems into Hebrew. However, you could perhaps claim that all of poetry is a kind of translation of dream language into waking language.

What’s your weirdest idea for a book you’ll never get to publish?

To write it in Yiddish.

And now, some poetry: from Beads for the Messiah's Bride: Poems on Leviticus (Time Being Books, 2009)

THE SCAPEGOAT

“And Aaron shall place both his hands on the head of the scapegoat and confess upon it all the sins of the Children of Israel and all their crimes, whatever their transgressions; they will be put on the head of the scapegoat, which will be sent off to the desert in the hands of the executioner.” (Leviticus 16:21)

Bright crimson ribbons tied between his horns,

A clanking, clinking bell around his neck,

His back bedecked with ornaments of silk —

Why did the priest place hands upon my head,

Then trembling shout a list of sins and crimes?

I bet I know: they want to crown me king,

A wise and noble king who never dies.

An orchestra of Levites play their flutes,

Their golden harps, their ten-stringed lutes, their drums,

Their silver trumpets as he is taken out —

Why I alone am sent to Azazel?

And who or what the hell is ‘Azazel’?

I bet I know: they think I am an angel,

A pure, immortal angel full of grace.

Out of the Temple precinct packed with crowds,

And out the narrow lanes of Jerusalem,

And out Damascus Gate, toward desert cliffs —

Why am I brought here to this mountain peak?

Why rip the crimson ribbons from my horns?

I bet I know: they wish to worship me,

I bet I —