Matt Rees's Blog - Posts Tagged "politics"

A lesson in (mad) Mideast politics

On Global Post, I report on the fairly crazy mess (even by Middle East standards) in which both Israeli and Palestinian politics find themselves just now.

Measuring Up: Inside Netanyahu's Head

Here's my post this week on Global Post:

JERUSALEM — In Hebrew the word for “to visit” – levaker – is the same as the word for “to criticize.” He visited me; he criticized me. Exactly the same.

So why would you invite 30 of the most critical people in the country to visit you every Sunday, to sit around your table and run their mouths?

You wouldn’t. Unless you wanted trouble.

That’s exactly what the new Israeli Prime Minister Binyamin Netanyahu has done. Each Sunday, an enormous cabinet – more than half the parliamentarians in the governing coalition are ministers and deputy ministers – will troop up the stairs to his office, preening for the cameras before they settle into their caramel leather chairs and let rip at the boss.

This wasn’t supposed to happen.

Last time he was Prime Minister – from 1996 to 1999 – Netanyahu held together a shaky coalition of rightists and hawkish centrists as long as he could. The religious-nationalists in the cabinet brought him down in the end.

Bruised he went into exile as a “consultant” for companies doing business in the U.S. He returned rich, bought a villa in the exclusive Mediterranean town of Caesarea, and gradually eased back into the politics of the Likud Party. His message, delivered in private in those days, was that he had learned his lesson. He was a different man. For a time he even tried to get people to stop calling him by his childhood nickname, “Bibi.”

One of the reasons the far right abandoned him in 1999 was, according to legislators, that he would always promise whatever you wanted, trying to make you happy, to make you like him. Then he’d contradict himself by pledging to do whatever the next person to enter his office wanted. When he returned to politics, Netanyahu said, he would no more be manipulated into giving tiny parties just what they demanded.

Take a look at this new government and you have to wonder if that’s true.

Netanyahu handed the rightist Yisrael Beitenu control of the Police Ministry, though the party’s leader is under police investigation for money laundering and fraud.

The ultra-Orthodox Shas party is practiced at squeezing prime ministers and received four ministerial seats in return for the support of its mere 11 legislators.

Ha-Beit Ha-Yehudi is an ultra-right backer of West Bank settlement and is sure to make problems for Netanyahu next time U.S. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton comes calling.

The least of his troubles ought to be Labor, traditionally powerful and center-left, because it stands for little except keeping its leader, Ehud Barak, in the Defense Ministry. Still some of the Labor legislators say they’ll rebel against Barak and won’t support the government.

Even within Netanyahu’s own Likud Party, some leaders are grumbling that they failed to secure top cabinet jobs.

The government has 69 out of 120 seats in the Knesset. Politically, socially, ethnically, it’s all over the map. Technically three of Netanyahu’s four partners could block his majority in parliament.

The new prime minister seems to be repeating his self-defeating pattern.

Where does this tendency come from? From the Netanyahu family.

Global Post editor-in-chief C.M. Sennott last week examined the way Bibi’s relationship with his father drives him (http://www.globalpost.com/dispatch/is...). I’d expand upon that: Bibi’s family relationships determine his performance as Prime Minister — and may have set him up for another failure as Prime Minister.

As a young man, Bibi lived in the shadow of the dominant father detailed by Sennott. He was also most definitely in second place behind his elder brother Yoni. In the nationalist-Zionist set of the day, Yoni was seen as a future chief of the army, even a prime minister. He died in the 1976 rescue of hostages at Entebbe, Uganda, leading the commando force that stormed a hijacked Air France jetliner.

That death — both heroic and tragic — preserved Yoni as he had been, a perfect example which any human — certainly one who followed such a compromising path as politics – could never quite live up to.

When Bibi became Prime Minister, he might have overcome this. But he didn’t. His performance back then showed that he had to leave room for Yoni to continue to be superior to him. It was as though surpassing Yoni would’ve been an act of defiance against the father who idolized his departed son. So Bibi sabotaged himself.

When I met him shortly before his ouster he was a shadow of the confident orator who narrowly won an election three years before. He toyed with a cigar stub and stared at his crystal ashtray, barely attempting eye contact. He was generally acknowledged to have been a poor prime minister.

I put this family theory to Netanyahu as delicately as I could when I rode in the armored car he called his Batmobile on election day in January 2003.

“I used to be in a hurry,” he said. “Now I’m not anxious. I don’t have to prove anything to anyone. I only have to prove things to myself. I’ve climbed the greasy pole. Now I’m perched on a branch.”

Uh-huh… I pushed him on the role his departed brother played psychologically in his first term as Prime Minister.

“In public life you shouldn’t press Rewind,” he said. “Or Fast Forward. You can press Eject, or you can press Play.”

Analyze that. Well, without Rewind, you can’t analyze anything. It’s the definition of repression.

We drove to the Har Hamenuchot cemetery on a stark Jerusalem hillside. It was the third jahrzeit — the anniversary — of the death of Tsila, Netanyahu’s mother. His father, Ben-Zion, stood stern and jowly, like John Gielgud cast as a headmaster. He wore a flat cap and a blue raincoat and was still, staring ahead as though unaware of the crowd of several hundred. Bibi read kaddish with his brother Ido, though his usually powerful baritone was a barely audible whisper.

The inscription on Tsila’s grave was in particularly complex language. I asked Bibi to clarify it for me. “It’s a very high Hebrew. My father wrote it,” he said. “It’s hard to translate.”

Perched on a branch back then, Netanyahu has crawled out all the way along the limb with his new coalition. If he can’t master his own psychological demons as Prime Minister this time, he won’t be the only one to take a fall.

JERUSALEM — In Hebrew the word for “to visit” – levaker – is the same as the word for “to criticize.” He visited me; he criticized me. Exactly the same.

So why would you invite 30 of the most critical people in the country to visit you every Sunday, to sit around your table and run their mouths?

You wouldn’t. Unless you wanted trouble.

That’s exactly what the new Israeli Prime Minister Binyamin Netanyahu has done. Each Sunday, an enormous cabinet – more than half the parliamentarians in the governing coalition are ministers and deputy ministers – will troop up the stairs to his office, preening for the cameras before they settle into their caramel leather chairs and let rip at the boss.

This wasn’t supposed to happen.

Last time he was Prime Minister – from 1996 to 1999 – Netanyahu held together a shaky coalition of rightists and hawkish centrists as long as he could. The religious-nationalists in the cabinet brought him down in the end.

Bruised he went into exile as a “consultant” for companies doing business in the U.S. He returned rich, bought a villa in the exclusive Mediterranean town of Caesarea, and gradually eased back into the politics of the Likud Party. His message, delivered in private in those days, was that he had learned his lesson. He was a different man. For a time he even tried to get people to stop calling him by his childhood nickname, “Bibi.”

One of the reasons the far right abandoned him in 1999 was, according to legislators, that he would always promise whatever you wanted, trying to make you happy, to make you like him. Then he’d contradict himself by pledging to do whatever the next person to enter his office wanted. When he returned to politics, Netanyahu said, he would no more be manipulated into giving tiny parties just what they demanded.

Take a look at this new government and you have to wonder if that’s true.

Netanyahu handed the rightist Yisrael Beitenu control of the Police Ministry, though the party’s leader is under police investigation for money laundering and fraud.

The ultra-Orthodox Shas party is practiced at squeezing prime ministers and received four ministerial seats in return for the support of its mere 11 legislators.

Ha-Beit Ha-Yehudi is an ultra-right backer of West Bank settlement and is sure to make problems for Netanyahu next time U.S. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton comes calling.

The least of his troubles ought to be Labor, traditionally powerful and center-left, because it stands for little except keeping its leader, Ehud Barak, in the Defense Ministry. Still some of the Labor legislators say they’ll rebel against Barak and won’t support the government.

Even within Netanyahu’s own Likud Party, some leaders are grumbling that they failed to secure top cabinet jobs.

The government has 69 out of 120 seats in the Knesset. Politically, socially, ethnically, it’s all over the map. Technically three of Netanyahu’s four partners could block his majority in parliament.

The new prime minister seems to be repeating his self-defeating pattern.

Where does this tendency come from? From the Netanyahu family.

Global Post editor-in-chief C.M. Sennott last week examined the way Bibi’s relationship with his father drives him (http://www.globalpost.com/dispatch/is...). I’d expand upon that: Bibi’s family relationships determine his performance as Prime Minister — and may have set him up for another failure as Prime Minister.

As a young man, Bibi lived in the shadow of the dominant father detailed by Sennott. He was also most definitely in second place behind his elder brother Yoni. In the nationalist-Zionist set of the day, Yoni was seen as a future chief of the army, even a prime minister. He died in the 1976 rescue of hostages at Entebbe, Uganda, leading the commando force that stormed a hijacked Air France jetliner.

That death — both heroic and tragic — preserved Yoni as he had been, a perfect example which any human — certainly one who followed such a compromising path as politics – could never quite live up to.

When Bibi became Prime Minister, he might have overcome this. But he didn’t. His performance back then showed that he had to leave room for Yoni to continue to be superior to him. It was as though surpassing Yoni would’ve been an act of defiance against the father who idolized his departed son. So Bibi sabotaged himself.

When I met him shortly before his ouster he was a shadow of the confident orator who narrowly won an election three years before. He toyed with a cigar stub and stared at his crystal ashtray, barely attempting eye contact. He was generally acknowledged to have been a poor prime minister.

I put this family theory to Netanyahu as delicately as I could when I rode in the armored car he called his Batmobile on election day in January 2003.

“I used to be in a hurry,” he said. “Now I’m not anxious. I don’t have to prove anything to anyone. I only have to prove things to myself. I’ve climbed the greasy pole. Now I’m perched on a branch.”

Uh-huh… I pushed him on the role his departed brother played psychologically in his first term as Prime Minister.

“In public life you shouldn’t press Rewind,” he said. “Or Fast Forward. You can press Eject, or you can press Play.”

Analyze that. Well, without Rewind, you can’t analyze anything. It’s the definition of repression.

We drove to the Har Hamenuchot cemetery on a stark Jerusalem hillside. It was the third jahrzeit — the anniversary — of the death of Tsila, Netanyahu’s mother. His father, Ben-Zion, stood stern and jowly, like John Gielgud cast as a headmaster. He wore a flat cap and a blue raincoat and was still, staring ahead as though unaware of the crowd of several hundred. Bibi read kaddish with his brother Ido, though his usually powerful baritone was a barely audible whisper.

The inscription on Tsila’s grave was in particularly complex language. I asked Bibi to clarify it for me. “It’s a very high Hebrew. My father wrote it,” he said. “It’s hard to translate.”

Perched on a branch back then, Netanyahu has crawled out all the way along the limb with his new coalition. If he can’t master his own psychological demons as Prime Minister this time, he won’t be the only one to take a fall.

What's the difference between Sharansky and Lieberman? Apart from a few inches, not much

By Matt Beynon Rees, published on Global Post

JERUSALEM — So, there are two eastern European guys, one from Ukraine and the other from Moldova.

One of them is on the short side and is a chess whiz who suffered through a Siberian labor camp for his uncompromising belief in democracy and freedom. Meet Natan Sharansky, who was picked this weekend by Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu to lead the Jewish Agency for Israel.

The other is a beefy former nightclub bouncer who says nasty things about Arabs and is generally seen as just plain uncompromising. Meet Foreign Minister Avigdor Lieberman, who, it’s fair to say, is feared and loathed as a hardliner.

The two men couldn't carry themselves more differently and you don't have to be a longtime observer of Israel to know which one fits in better with the western diplomatic community and is most favored by America.

Trouble is they’re essentially the same guy.

Both reflect something unbending in current Israeli political thinking. But international diplomats will make a mistake if they ignore the reality signaled by the popularity of these two politicians and its consequences for the peace maneuvers that got underway this last week.

Sharansky pulled out of former prime minister Ariel Sharon’s government in 2005 to protest the Israeli withdrawal from its Gaza settlements and has since been occupying an office in a right-wing think thank in Jerusalem — when he hasn’t been touring the U.S. on high-paying speaking gigs.

Lieberman, meanwhile, lives in a settlement, drove his party to third place in the country’s February election with a promise of imposing a loyalty oath on Arab citizens of Israel, and, in his first statement as foreign minister, said "If you want peace, prepare for war."

That classically Lieberman aphorism prompted gritted teeth at the State Department, which sent special envoy George Mitchell to Ramallah and Cairo recently to prepare the U.S. plan for handling the new Israeli government.

But in their different ways, Sharansky and Lieberman are both saying the same thing: Israelis are tired of being pressured to hand over land to Palestinians, while the Palestinians ignore the world’s polite requests for an end to terrorism.

When I met with Sharansky just after he resigned from the cabinet in 2005, he explained what he had told Prime Minister Sharon when he went to his office to quit.

“One-sided concessions by us leave the Palestinians with their problems,” he said. “It’s an illusion to think international pressure on us will stop when we make concessions. We’re making terrorism legitimate. We dismantle settlements, terror continues, and the world will say we just didn’t dismantle enough.”

That’s how most Israelis tend to see things these days. (If you don’t believe that, check out the election results and witness the disappearance of the so-called left-wing parties.) And Sharansky's position is remarkably close to that of Lieberman. For example, instead of simply giving up the West Bank to the Palestinians, Lieberman has said that Israel ought to keep some of its settlement blocs and, in return, hand over parts of Israel where its Arab population lives to a new Palestinian state.

For Israelis, that would give them a sense of having driven a good bargain and received something in return for their concessions.

Western observers may not see things that way, but now they know what Israelis think. And Israelis are the ones that count.

So maybe we need to look for the difference between the two men for a hint of how we ought to interpret their positions.

The answer: democracy.

Sharansky, 61, wrote “The Case for Democracy” in 2004. It was a favorite of George W. Bush. It argued that the dictatorial Arab regimes couldn’t make peace with democratic Israel — totalitarian regimes need an enemy to demonize. The west needed to make the Arab countries democratic, instead of bolstering dictators.

We all like democracy, of course. So thumbs up for Sharansky, whose book went onto The New York Times bestseller list.

Lieberman, on the other hand, is generally portrayed as rather Stalinist in his approach to dissent and minorities. That earns him the Bronx cheer from the media.

The thing to remember is that it also earned him 15 seats in the parliament, leadership of the second-biggest party in the new coalition government, and the foreign minister’s chair.

Sharansky, by contrast, is being nominated to lead a body whose main function in these days of falling immigration is to encourage Jews in the diaspora to remain connected to their community. (Jewish Agency officials fear the dwindling population of Jews worldwide through intermarriage, and cite 50,000 new “former Jews” each year around the world due to assimilation.)

The former dissident Sharansky will be the lovable face of Israel’s new tough line and may even make it to the (ceremonial) president’s mansion in a few years. But it’s Lieberman who wields power.

JERUSALEM — So, there are two eastern European guys, one from Ukraine and the other from Moldova.

One of them is on the short side and is a chess whiz who suffered through a Siberian labor camp for his uncompromising belief in democracy and freedom. Meet Natan Sharansky, who was picked this weekend by Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu to lead the Jewish Agency for Israel.

The other is a beefy former nightclub bouncer who says nasty things about Arabs and is generally seen as just plain uncompromising. Meet Foreign Minister Avigdor Lieberman, who, it’s fair to say, is feared and loathed as a hardliner.

The two men couldn't carry themselves more differently and you don't have to be a longtime observer of Israel to know which one fits in better with the western diplomatic community and is most favored by America.

Trouble is they’re essentially the same guy.

Both reflect something unbending in current Israeli political thinking. But international diplomats will make a mistake if they ignore the reality signaled by the popularity of these two politicians and its consequences for the peace maneuvers that got underway this last week.

Sharansky pulled out of former prime minister Ariel Sharon’s government in 2005 to protest the Israeli withdrawal from its Gaza settlements and has since been occupying an office in a right-wing think thank in Jerusalem — when he hasn’t been touring the U.S. on high-paying speaking gigs.

Lieberman, meanwhile, lives in a settlement, drove his party to third place in the country’s February election with a promise of imposing a loyalty oath on Arab citizens of Israel, and, in his first statement as foreign minister, said "If you want peace, prepare for war."

That classically Lieberman aphorism prompted gritted teeth at the State Department, which sent special envoy George Mitchell to Ramallah and Cairo recently to prepare the U.S. plan for handling the new Israeli government.

But in their different ways, Sharansky and Lieberman are both saying the same thing: Israelis are tired of being pressured to hand over land to Palestinians, while the Palestinians ignore the world’s polite requests for an end to terrorism.

When I met with Sharansky just after he resigned from the cabinet in 2005, he explained what he had told Prime Minister Sharon when he went to his office to quit.

“One-sided concessions by us leave the Palestinians with their problems,” he said. “It’s an illusion to think international pressure on us will stop when we make concessions. We’re making terrorism legitimate. We dismantle settlements, terror continues, and the world will say we just didn’t dismantle enough.”

That’s how most Israelis tend to see things these days. (If you don’t believe that, check out the election results and witness the disappearance of the so-called left-wing parties.) And Sharansky's position is remarkably close to that of Lieberman. For example, instead of simply giving up the West Bank to the Palestinians, Lieberman has said that Israel ought to keep some of its settlement blocs and, in return, hand over parts of Israel where its Arab population lives to a new Palestinian state.

For Israelis, that would give them a sense of having driven a good bargain and received something in return for their concessions.

Western observers may not see things that way, but now they know what Israelis think. And Israelis are the ones that count.

So maybe we need to look for the difference between the two men for a hint of how we ought to interpret their positions.

The answer: democracy.

Sharansky, 61, wrote “The Case for Democracy” in 2004. It was a favorite of George W. Bush. It argued that the dictatorial Arab regimes couldn’t make peace with democratic Israel — totalitarian regimes need an enemy to demonize. The west needed to make the Arab countries democratic, instead of bolstering dictators.

We all like democracy, of course. So thumbs up for Sharansky, whose book went onto The New York Times bestseller list.

Lieberman, on the other hand, is generally portrayed as rather Stalinist in his approach to dissent and minorities. That earns him the Bronx cheer from the media.

The thing to remember is that it also earned him 15 seats in the parliament, leadership of the second-biggest party in the new coalition government, and the foreign minister’s chair.

Sharansky, by contrast, is being nominated to lead a body whose main function in these days of falling immigration is to encourage Jews in the diaspora to remain connected to their community. (Jewish Agency officials fear the dwindling population of Jews worldwide through intermarriage, and cite 50,000 new “former Jews” each year around the world due to assimilation.)

The former dissident Sharansky will be the lovable face of Israel’s new tough line and may even make it to the (ceremonial) president’s mansion in a few years. But it’s Lieberman who wields power.

Hebron settlers sit tight and worry

As the U.S. increases pressure on Israel to dismantle settlements, Hebron residents wonder who they can turn to. By Matt Beynon Rees - GlobalPost

HEBRON, West Bank — He’s stayed in the largest town in the West Bank for 36 years, even though most of its 167,000 residents want him to leave. He’s just won a $50,000 prize for his “Zionist activities” there. His country’s new government is vilified around the world because it’s seen as supportive of people just like him.

You’d think Noam Arnon would be feeling a lot more secure than he is.

But the 54-year-old leader of Hebron’s 700 Israeli settlers is worried that Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu won’t stand up to a new U.S. administration that promises to be tougher on Israel’s continued construction on occupied land.

“I know that we can’t trust him,” Arnon says, as he enters the ancient Cave of the Patriarchs, burial place of the biblical couples Abraham and Sara, Isaac and Rebecca, Jacob and Leah. “[Netanyahu:] is not a strong man. He’s very weak. Under pressure he collapses very fast.”

It’s commonplace among diplomats and foreign correspondents to refer to Arnon as “crazy.” After all, he’s bringing up his eight children in a hostile city whose municipality is run by Hamas. But the tag comes mainly from his opposition to the idea that Israelis ought to leave their settlements in return for peace. If the 282,000 Israeli settlers in the West Bank are generally seen as an obstruction in peace talks, the residents of the Jewish Quarter of Hebron are viewed as violent extremists reveling in the hatred that surrounds them.

Arnon, of course, doesn’t see it that way, and he’s not the only one. In a few weeks he’ll receive the Moskowitz Prize for Zionism awarded by Irving Moskowitz, a Florida resident mainly known for his support for controversial attempts by Israeli nationalists to plant colonies in Palestinian neighborhoods of Jerusalem. One reason Moskowitz decided to give the award to a Hebron settler was in recognition of the anniversary of a massacre of Jews in the city by Palestinians 80 years ago. It was followed by the expulsion of the Jewish residents, who only returned in the 1970s.

Until the massacre of 1929, as Arnon likes to point out, Jews had lived in Hebron since Abraham arrived 4,000 years ago. The patriarch bought the cave over which King Herod built the existing massive edifice at the time of Christ in the same style as his Great Temple in Jerusalem. (“Herod,” says Arnon, “was a complicated personality, but he knew how to build.” Which is what many people say about Moskowitz.)

The memory of the massacre, like the hostility of Hebron’s Arabs, only serves to strengthen Arnon’s determination to stay in the dusty, deserted quarter of the town where Israelis are permitted to reside. I walked with Arnon through the once-bustling market area between the Cave of the Patriarchs and the 120-year-old Hadassah building in which he lives. The Arab shops have been shuttered for five years for the security of Arnon and the other settlers.

“Don’t blame me for these shops being closed,” he says. “Blame the terrorists.”

Six paratroopers swap their red berets for helmets as we pass. They go single file into a narrow alley in the casbah, built in the time of Turkish rule. As they step out of sight, each one locks and loads his M-16 and takes a deep breath as though diving into water.

The edgy soldiers are patrolling the dividing line between Israeli-controlled Hebron and the part of the town handed over to the Palestinian Authority in 1997. Arnon needs no reminding who was prime minister when the bulk of his town was given to people he considers terrorists: Netanyahu.

The new Israeli prime minister visits Washington next week. The Obama administration has been trying to weaken his opposition to an independent Palestinian state and restrictions on Israeli construction in the settlements.

Last week, U.S. Vice President Joe Biden told a pro-Israel lobbying group that Israel ought to “not build more settlements, dismantle existing outposts and allow the Palestinians freedom of movement."

Combine that pressure with Netanyahu’s pullout from much of Hebron a decade ago and you see why Arnon has some doubts about his community’s future. To those who say Netanyahu is deeply right-wing and couldn’t possibly evacuate settlements, Arnon points out that it was the fiercely nationalistic Prime Minister Ariel Sharon who forced almost 10,000 settlers from their homes in the Gaza Strip settlements in 2005.

When Arnon and I sit with the mayor of Kiryat Arba, the 7,000-person settlement that abuts Hebron, he’s deeply skeptical of Malachi Levinger’s hope to build 2,000 new homes there over the next decade.

“This is very optimistic,” Arnon says.

“If the government won’t help us, God will help us,” says Levinger, whose rabbi father was the founder of the settlement in Hebron.

Levinger says that during the February election campaign, Netanyahu promised him that construction would go ahead full steam in the settlements. “Also after the election, [Netanyahu:] said we’d move ahead with building,” he says.

Asked if the prime minister had actually told him since the election that new building permits would be issued, Levinger backs off. “No, but I’ve been told this in conversations with ministers,” he says. “They’ve told me.”

Arnon shakes his head.

HEBRON, West Bank — He’s stayed in the largest town in the West Bank for 36 years, even though most of its 167,000 residents want him to leave. He’s just won a $50,000 prize for his “Zionist activities” there. His country’s new government is vilified around the world because it’s seen as supportive of people just like him.

You’d think Noam Arnon would be feeling a lot more secure than he is.

But the 54-year-old leader of Hebron’s 700 Israeli settlers is worried that Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu won’t stand up to a new U.S. administration that promises to be tougher on Israel’s continued construction on occupied land.

“I know that we can’t trust him,” Arnon says, as he enters the ancient Cave of the Patriarchs, burial place of the biblical couples Abraham and Sara, Isaac and Rebecca, Jacob and Leah. “[Netanyahu:] is not a strong man. He’s very weak. Under pressure he collapses very fast.”

It’s commonplace among diplomats and foreign correspondents to refer to Arnon as “crazy.” After all, he’s bringing up his eight children in a hostile city whose municipality is run by Hamas. But the tag comes mainly from his opposition to the idea that Israelis ought to leave their settlements in return for peace. If the 282,000 Israeli settlers in the West Bank are generally seen as an obstruction in peace talks, the residents of the Jewish Quarter of Hebron are viewed as violent extremists reveling in the hatred that surrounds them.

Arnon, of course, doesn’t see it that way, and he’s not the only one. In a few weeks he’ll receive the Moskowitz Prize for Zionism awarded by Irving Moskowitz, a Florida resident mainly known for his support for controversial attempts by Israeli nationalists to plant colonies in Palestinian neighborhoods of Jerusalem. One reason Moskowitz decided to give the award to a Hebron settler was in recognition of the anniversary of a massacre of Jews in the city by Palestinians 80 years ago. It was followed by the expulsion of the Jewish residents, who only returned in the 1970s.

Until the massacre of 1929, as Arnon likes to point out, Jews had lived in Hebron since Abraham arrived 4,000 years ago. The patriarch bought the cave over which King Herod built the existing massive edifice at the time of Christ in the same style as his Great Temple in Jerusalem. (“Herod,” says Arnon, “was a complicated personality, but he knew how to build.” Which is what many people say about Moskowitz.)

The memory of the massacre, like the hostility of Hebron’s Arabs, only serves to strengthen Arnon’s determination to stay in the dusty, deserted quarter of the town where Israelis are permitted to reside. I walked with Arnon through the once-bustling market area between the Cave of the Patriarchs and the 120-year-old Hadassah building in which he lives. The Arab shops have been shuttered for five years for the security of Arnon and the other settlers.

“Don’t blame me for these shops being closed,” he says. “Blame the terrorists.”

Six paratroopers swap their red berets for helmets as we pass. They go single file into a narrow alley in the casbah, built in the time of Turkish rule. As they step out of sight, each one locks and loads his M-16 and takes a deep breath as though diving into water.

The edgy soldiers are patrolling the dividing line between Israeli-controlled Hebron and the part of the town handed over to the Palestinian Authority in 1997. Arnon needs no reminding who was prime minister when the bulk of his town was given to people he considers terrorists: Netanyahu.

The new Israeli prime minister visits Washington next week. The Obama administration has been trying to weaken his opposition to an independent Palestinian state and restrictions on Israeli construction in the settlements.

Last week, U.S. Vice President Joe Biden told a pro-Israel lobbying group that Israel ought to “not build more settlements, dismantle existing outposts and allow the Palestinians freedom of movement."

Combine that pressure with Netanyahu’s pullout from much of Hebron a decade ago and you see why Arnon has some doubts about his community’s future. To those who say Netanyahu is deeply right-wing and couldn’t possibly evacuate settlements, Arnon points out that it was the fiercely nationalistic Prime Minister Ariel Sharon who forced almost 10,000 settlers from their homes in the Gaza Strip settlements in 2005.

When Arnon and I sit with the mayor of Kiryat Arba, the 7,000-person settlement that abuts Hebron, he’s deeply skeptical of Malachi Levinger’s hope to build 2,000 new homes there over the next decade.

“This is very optimistic,” Arnon says.

“If the government won’t help us, God will help us,” says Levinger, whose rabbi father was the founder of the settlement in Hebron.

Levinger says that during the February election campaign, Netanyahu promised him that construction would go ahead full steam in the settlements. “Also after the election, [Netanyahu:] said we’d move ahead with building,” he says.

Asked if the prime minister had actually told him since the election that new building permits would be issued, Levinger backs off. “No, but I’ve been told this in conversations with ministers,” he says. “They’ve told me.”

Arnon shakes his head.

Obama's speech: the view from Jerusalem

President Barack Obama spelled out what he expects of the Israeli government in his Cairo speech, issuing a challenge that most commentators here believe Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu has no way of meeting [I wrote on Global Post today:].

Obama’s speech, carried live on all three main Israeli television stations, made clear his firm opposition to any sort of building in Israel’s West Bank settlements. “This construction violates previous agreements and undermines efforts to achieve peace,” Obama said. “It is time for these settlements to stop.”

The realization that Obama is serious about halting settlements has been growing in Israel since Secretary of State Hillary Clinton visited in early March. At first Israeli politicians and diplomats thought it could be dealt with by the same sleight of hand that stymied previous administrations — Israel would agree to a freeze on settlement construction, except for “natural growth” to accommodate the children of existing settlers. In reality that meant as much building as Israel wanted.

Since Netanyahu’s visit to Washington two weeks ago, aggrieved Israeli government officials (who weren’t immediately available to comment on Obama's speech) have complained that there were unwritten agreements with the Bush White House allowing Israel to build in the settlements, provided they pulled out of “illegal outposts” — mainly composed of a few young settlers living in shipping containers on hillsides across the valley from existing settlements.

Obama’s speech made it clear that such unwritten promises are not part of the debate. Read more....

Obama’s speech, carried live on all three main Israeli television stations, made clear his firm opposition to any sort of building in Israel’s West Bank settlements. “This construction violates previous agreements and undermines efforts to achieve peace,” Obama said. “It is time for these settlements to stop.”

The realization that Obama is serious about halting settlements has been growing in Israel since Secretary of State Hillary Clinton visited in early March. At first Israeli politicians and diplomats thought it could be dealt with by the same sleight of hand that stymied previous administrations — Israel would agree to a freeze on settlement construction, except for “natural growth” to accommodate the children of existing settlers. In reality that meant as much building as Israel wanted.

Since Netanyahu’s visit to Washington two weeks ago, aggrieved Israeli government officials (who weren’t immediately available to comment on Obama's speech) have complained that there were unwritten agreements with the Bush White House allowing Israel to build in the settlements, provided they pulled out of “illegal outposts” — mainly composed of a few young settlers living in shipping containers on hillsides across the valley from existing settlements.

Obama’s speech made it clear that such unwritten promises are not part of the debate. Read more....

Writer is pro-Palestinian and pro-Israeli

The best thing about moving from journalism to fiction writing is that people show you more respect.

The best thing about moving from journalism to fiction writing is that people show you more respect.As a journalist covering a troubling issue like the Israel-Palestinian conflict, I was often subject to rather nasty verbal attacks during public speaking engagements. For a partisan of either side, I seemed a fine target for their generalized contempt—they thought journalists were all against them and here was a live reporter on whom they could vent their spleen.

Thankfully that doesn’t happen now that I’m the author of a series of Palestinian crime novels. I wasn’t sure that it would be different, but it turns out that there’s a big change in the way people behave toward me.

Here are two examples from the last week alone.

In Cologne, Germany, last week, I talked in a bookstore at the invitation of the Cologne-Bethlehem Association. Much of the audience was made up of middle-aged and older Germans who visit Bethlehem frequently and have made strong ties with the people there.

One older gentleman suggested that, because my first novel THE COLLABORATOR OF BETHLEHEM shows the corruption and extortion carried out by the gunmen of the town during the intifada, my book “tended toward Israeli propaganda.”

But the old fellow was very respectful and as I answered him I could tell he was listening. (My response, of course, is along the lines of “No, actually the book doesn’t even address whether or not it’s right to shoot at Israelis; the book concerns itself with the negative effect those gunmen had WITHIN Palestinian society.”) Listening’s something that was often evidently not happening when, as a journalist, I would talk to audiences.

Then this week I went to the Israeli settlement of Efrat in the West Bank. I’ve visited many times before to write news reports about the confiscation of land or the endless pressure from Washington to stop building in the settlements. This time I was invited by the Gush Etzion Book Group, a few dozen women who live in the local settlements.

There had been quite some fiery debate within the group about whether to have me come and speak to them. Indeed, someone hinted that certain members of the group had stayed away.

Nonetheless, I was glad to be there. After all, much of THE COLLABORATOR OF BETHLEHEM takes place in the village of Artas and the Dehaisha Refugee Camp, which abut the northern reaches of Efrat. I want very much to talk about my books with people who have a stake in the Israeli-Palestinian struggle. Provided they’re willing to listen respectfully, to examine what I’m actually saying and not what they think I’m saying (or what they wish I’d say.)

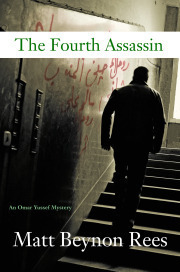

The evening in Efrat went well and, in fact, much of what we talked about was how little I’m interested in politics—despite the apparently political subject-matter of my novels. What interests me is “the life that remains when politics is sluiced away like the filth a stray dog leaves in the street” (that’s a line from my sleuth Omar Yussef in THE FOURTH ASSASSIN, the next of my novels, which will be published Feb. 1).

Such respectful treatment is a big contrast to situations I encountered as a journalist. Then I would look out over audiences which seemed to be entirely red-faced and with arms crossed over every chest. The hostlie body language didn’t change, even though I was essentially saying the same things I’m saying now. Partisans hate journalists and, I believe, many of them used somehow to detest that I had found a kind of personal peace in covering the very conflict that stirs them up and stresses them so.

In Cologne and Efrat, people heard what I had to say and understood that I’m pro-Palestinian and pro-Israeli. I'd like all the people I know here to have a good life, not the violent situation they suffer. Politics makes people choose sides, and I want no part of that.

I also think choosing sides makes for rather bad novels. It’s in the shades of gray, where decisions are so difficult or even impossible to make, that a novel becomes truly compelling--think of Graham Greene’s best novels. Political journalism on the other hand is, to say the least, dreary. Think of the glib rubbish turned out by columnists who have to fill three op-ed spaces each week.

Who would you respect more—Graham Greene or G. Gordon Liddy? See what I mean?

So I’ll continue to talk about my books to anyone who’ll take the time to read them, because that in itself is a sign of respect and openness. Those, after all, are the qualities most needed by both sides of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict if they’re ever to find peace.

(I posted this first on a joint blog I write with some other international crime writers.)

Published on January 14, 2010 23:21

•

Tags:

bethlehem, book-groups, cologne, crime-fiction, efrat, fiction, g-gordon-liddy, graham-greene, gush-etzion, international-crime-authors-blog, israel, israelis, journalism, koeln, matt-beynon-rees, mystery-novels, omar-yussef, palestine, palestinians, politics, settlements, settlers, the-collaborator-of-bethlehem, the-fourth-assassin, west-bank

Jerusalem Zoo: Penguins before pols

Here's a whimsical video explaining why the Jerusalem Biblical Zoo is the best vantage point from which to observe the Palestinian-Israeli conflict -- superior even than a Gaza refugee camp or an Israeli military base. Seriously. And yet not.

Published on February 11, 2010 00:55

•

Tags:

animals, arabs, crime-fiction, fish, global-post, israel, israeli-palestinian-conflict, jerusalem, jerusalem-biblical-zoo, journalism, leopards, lions, matt-beynon-rees, middle-east, palestine, penguins, politicians, politics, sara-sorcher, terrorism, tigers, ultra-orthodox-jews, video

Cameron can't solve English i.d. crisis

I was at Oxford University at the same time as Britain's new prime minister. But while I spent all my free time at a famous old pub opposite the historic Bodleian Library with a pint of Guinness in the company of some old Irish porters, I never saw David Cameron there. Which makes me doubt his suitability for office.

I was at Oxford University at the same time as Britain's new prime minister. But while I spent all my free time at a famous old pub opposite the historic Bodleian Library with a pint of Guinness in the company of some old Irish porters, I never saw David Cameron there. Which makes me doubt his suitability for office.That's not because I think the prime minister should be overfond of alcohol (at Oxford, Cameron was a member of a very upper-crust private drinking club famed for smashing places up). Rather, it's because Cameron is the wrong man to unite the pub-drinkers and the rowdy aristocrats -- and all the other splinters of a society still shattered by Margaret Thatcher's destruction of the old identity of Empire.

The coalition Cameron will lead reflects an identity crisis among the English that has developed in the two decades since Thatcher's reign. It's much deeper than mere political divisions, and I don't think he's equipped to resolve it.

Read the rest of my article on AOL News.

Published on May 13, 2010 23:20

•

Tags:

aol-news, britain, david-cameron, england, english-identity, margaret-thatcher, matt-beynon-rees, oxford-university, politics, prime-minister

With democracy like this, who needs dictators?

JERUSALEM — Israelis like to point out that theirs is the only democracy in a Middle East otherwise dominated by repressive regimes. Given the performance of legislators in the parliamentary session that just ended here, you might be forgiven for asking: with democracy like this, who needs dictators?

JERUSALEM — Israelis like to point out that theirs is the only democracy in a Middle East otherwise dominated by repressive regimes. Given the performance of legislators in the parliamentary session that just ended here, you might be forgiven for asking: with democracy like this, who needs dictators?The Knesset, Israel’s parliament, broke up last week for its summer vacation. The speaker of the Knesset, Reuven Rivlin, sent lawmakers on their way with an interview in an Israeli newspaper in which he described them as “pathetic.” Several human rights organizations slammed as dangerous to democracy more than a dozen bills that passed preliminary readings. The most abiding image of the session was surely the gang of right-wing legislators heckling and threatening a female Arab parliamentarian who had been aboard a Turkish ship intercepted by Israeli commandos en route for Gaza.

In a letter to Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu last week, Debbie Gild-Hayo, director of policy advocacy at the Association for Civil Rights in Israel, complained of “14 dangerous draft bills” introduced to the departing parliament.

“The Knesset is supposed to be a bastion of democracy,” Gild-Hayo wrote. “It seems an increasing number of Members of Knesset believe that their job is to silence those who do not share their views.”

The most headlines were devoted to a confrontation between conservative legislators and Haneen Zoabi, the female Arab lawmaker. Zoabi was aboard one of the Turkish boats intercepted May 31 by Israeli troops, which resulted in nine dead among the activists on board. They were protesting the Israeli blockade of Gaza by trying to run it.

The Knesset voted two weeks ago to suspend Zoabi some parliamentary privileges. She called this an act of “revenge” for her participation in the seaborne protest. A right-wing Israeli lawmaker brandished an enlarged facsimile of an Iranian passport with Zoabi’s photo in it. (Zoabi has suggested that Iran should have nuclear weapons to balance Israel’s arsenal.)

Read the rest of this post on my blog The Man of Twists and Turns.

Published on August 01, 2010 05:38

•

Tags:

arab, benjamin-netanyahu, gaza, haneen-zoabi, israel, israel-our-home, jerusalem, jew, knesset, middle-east, politics, reuven-rivlin, turkish-flotilla, west-bank

Omar Yussef predicted Cairo and Tunis

If you’ve been wondering why the people of Tunisia and Egypt have risen up against their dictators and why it caught Washington with pants down, it’s because you didn’t read THE FOURTH ASSASSIN, the latest of my Palestinian crime novels.

If you’ve been wondering why the people of Tunisia and Egypt have risen up against their dictators and why it caught Washington with pants down, it’s because you didn’t read THE FOURTH ASSASSIN, the latest of my Palestinian crime novels.In THE FOURTH ASSASSIN, which was published exactly a year ago, my Palestinian sleuth Omar Yussef travels to New York for a conference at the UN. While there, he uncovers an assassination plot. But he also has to address the conference about the life of ordinary Palestinians —— and the people of other Arab countries.

Here’s a passage from that chapter of the book, with Omar addressing the delegates from Arab countries and the Americans:

“ ‘It may be hard for you to understand, but what ordinary Palestinians want and what they battle for every day is precisely what’s denied to most of your citizens in the Arab countries: freedom and economic prosperity.’

The Libyan delegate removed his finger from his nose and flicked it angrily. The Syrian strode down from the rear of the hall, dropping his

cigarette. The Lebanese stepped out the butt on the carpet as he followed.

‘How can you, the Arab countries, dictate a solution for the Palestinians, when you suffer from many of the same problems? In fact, you, the governing class, thrive on the lack of democracy, the inequality of wealth. Take away the Israeli occupation and the Palestinians would be closer to freedom and a functioning economy than most of your peoples.’

Read the rest of this post on my blog The Man of Twists and Turns.

Published on February 02, 2011 01:00

•

Tags:

bashar-assad, brooklyn, cairo, crime-fiction, egypt, middle-east, new-york, omar-yussef, politics, syria, the-fourth-assassin, tunis, united-nations, washington