Satima Flavell's Blog

June 21, 2020

Farewell to My Blog

I've been writing for Blogger for ten years with an output of 79 posts. This will be the eightieth and final offering.

It is a shame that blogging has been usurped by Facebook et al, but it must be admitted that the newer form of communication is faster and easier to maintain - and reaches a bigger audience than blogging. If you don't already read me on Facebook, look me up at https://www.facebook.com/SatimaFlavell. I am there almost every day, reading what my friends have been up to and shouting to the universe about my own activities.

Those of you who use Facebook are welcome to friend me, and if you have a Facebook page of your own I will friend you, too, and I'll stop by to say g'day.

I'd like to think I've made friends on Blogger, and I hope all those friends will will have long and happy lives and enjoy many cyber-friendships, as I have, both here and on Facebook.

May you all be well and happy for many years to come. My love to you all.

And hey, don't forget to look up my offer of a free novella about Nariel!

Published on June 21, 2020 00:23

July 20, 2019

Writing, Writing, Writing

Writing books - what fun! At least, that's what I thought at the age of five, when I was just starting to realise that books had to be written by somebody. Enid Blyton, Rudyard Kipling and Arthur Ransom were my favourite authors until I was about eleven, and when anyone asked what I wanted to be when I grew up I would say 'I want to be a children's authoress, like Enid Blyton'. I also had a yen to be a ballet dancer, but seeing as my parents wouldn't let me join a class, I read books about ballet instead. The Ballet Annual was my favourite, but anything with pictures of dancers would grab my fancy at the library.

By the time I was eleven, I was getting enough pocket money to pay for one ballet class a week, and when I was fourteen my teacher gave me free lessons in return for helping with the young children's classes on Saturday mornings. I struggled through my exams, rarely getting honours, while at school I was winning awards and high grades for writing. I also wrote stories and poems for the Chucklers Weekly - a magazine for kids and teens. They paid me a pound ($2) a time!

Dance-wise, by this time, the 'Balanchine body' was the one ballet companies sought - light build, a long neck, and legs half the total height. Prior to this time, most dance companies and musical shows had room for a few shorter girls to appear in character roles: they even had their own routines in musicals as the 'pony ballet'. Alas, Mr Balanchine's preference prevailed in all dance auditions by the time I reached my late teens, so professional ballet dancing as a career was a door closed to me.

However, I continued to excel academically, to the point I was able to matriculate a year early. I continued to dance, and eventually found work in cabaret (dancing the can-can three or four times a night keeps you fit, believe me!) while dancing occasional seasons with the Australian Dance Theatre a small contemporary dance company. With them, I danced before the Queen and Prince Phillip, dressed as a brolga! (See my post from December 2018 for more on this.)

In my forties I studied at the West Australian Academy of Performing Arts to 'update my expertise'. Hah hah! - when one is in one's forties, one's expertise does not enjoy being updated, and it was only with a struggle that I attained an Associate Diploma of Performing Arts. I also undertook Religious Studies (this was mainly in that glorious time when tertiary education was free in Australia!) and eventually I graduated Bachelor of Arts.

The BA with a Religious Studies major and a Dance minor has proved to be quite the least useful degree when seeking employment, but I was fortunate enough, due to a tip from one of the staff at WAAPA, to get a regular gig writing reviews of dance shows for Music Maker, and to my surprise I was head hunted by the Sydney Morning Herald to write for them, too. Since then I have continued to write reviews here and there, except for a three year break when I was traveling overseas in the late nineties. When I got back from my travels, I went back into this line of work, writing for the Artshub website, balanced by teaching ballet to senior folk like myself until late last year, when I finally hung up my ballet flats, and have only written a few reviews in the interim.

Writing fiction, however, is a whole different kettle of fish. It was during my travels that I first thought of writing fiction since I was a little child. I had a tiring job as housekeeper at a hotel in Devon, UK, and every evening after work I would collapse in front of the TV to watch the soapies. But one night, before I turned on the TV, a sentence popped in to my head: 'To be left a widow at the age of twenty-one may sound like a tragedy, but, to be honest, I felt liberated by Reyel’s death.' I knew at once it was the start of a story. not one that I'd read, but a new one - my very own book! The next day I bought an exercise book, and every night after work I would write for an hour or two. Of course, the result was not a very good book. First novels seldom are any good, but as the Bard of Avon said 'Tis a poor thing, but mine own'.

So here I am trying hard to make sense of my third novel to complete The Talismans trilogy. The first two books have not sold particularly well - but for the creator, traveling hopefully is better than to arrive.

Published on July 20, 2019 22:46

June 14, 2019

Review: Tosca by Freeze Frame Opera

Review of Freeze Frame Opera's production of La Tosca (Puccini)

‘Freeze Frame Opera’ is a puzzling name for a new opera company, and I have been unable to find a rhyme or reason for the choice of name. Set that aside, though, because this is as professional a troupe as any other ensemble I’ve seen in the genre. Their Facebook page tells us they are ‘committed to creating engaging, intimate opera experiences that appeal to both traditional and modern audiences’ and if the performance I saw is any guide, they have indeed succeeded with this fine production of Puccini’s Tosca. OK, there is no orchestra. Nor is there a chorus, although in one scene, the singers, still in character, created a chorus by playing a recording.

The singers, James Clayton as Scarpia, Jun Zhang as Cavaradossi, Kristin Bowtell as Angelotti, Pia Harris as Spoletta, Jake Bigwood as Sciarrone, Robert Hofmann as the sacristan and jailer and Harriet (Hattie) Marshall as Tosca all did a sterling job. They were fortunate in having engaged the services of Tomaso Pollio as musical director – he spent the entire performance (three hours!) at the piano -an excellent baby grand, played beautifully.

[image error]

Harriet Marshall as La Tosca (Photo courtesy of Freeze Frame Opera)

Harriet Marshall as La Tosca (Photo courtesy of Freeze Frame Opera)The season was, I understand, the brainchild of soprano ‘Hattie’ Marshall who, apart from singing the lead role, is credited as ‘producer’. This suggests she was in charge of finding finance as well as singing, and if so, she has done a great job on both fronts. Some thirty benefactors are listed, not counting the input from the state government’s Department of Local Government, Sport and Cultural Industries. Anything that keep entertainers working between seasons (the singers are all members of the WA Opera) has got to be a boost for the industry. I saw only one performance, but it had a packed house, and if the other performances were as well attended, it’s a sign that opera has a keen audience and therefore a viable future.

The musical high point of any production of Tosca is the diva’s rendition of Vissi d’arte, vissi d’amore. Marshall delivered this beloved aria with feeling and, of course, beautiful technique. All the performers are consummate actors as well as excellent singers. Gone are the days, heaven be thanked, when divas were all chubby ladies who could sing but not act!

This season, the company is using the Centenary Pavilion at Perth Showgrounds. It is not, perhaps, the best venue for an intimate opera performance – the acting area was huge, and largely wasted. A possible improvement might be to close off some of the rather factory-like archways.

Such an intimate performance with limited audience seating didn’t quite work for me at that venue – not only because of the above minor complaints – but largely because it was a very cold night and the heating was inadequate. Given the unsuitability of the venue, the performers did a sterling job. Quite honestly, I’d rather see a show in a church hall, if a theatre booking would overstretch the budget.

This was my very first ‘Tosca’. I was familiar with most of the music (thanks largely to the ABC, but also to my singing teacher of long ago who coached me in my teenage rendering of Visi d’arte!) It was great to see the story come to life. Many thanks to the cast and crew for all their hard work!

Published on June 14, 2019 21:35

December 6, 2018

End of an Era

This week, I taught my last dance class.

Me, performing, aged 28I started teaching as an off-sider to Miss Joan Ashton in Liverpool, NSW, shortly before my fifteenth birthday, so I have taught ballet and related genres for over sixty years. I haven’t taught non-stop, of course – I took time out from teaching to perform in my early twenties, but thereafter I taught whenever I could, household tasks and child-rearing duties permitting. I have taught in three Australian states and in Auckland, New Zealand. Ballet has long been my first love, and I hope I have imparted that devotion to many of my students. As far as I know, none of them became professional dancers or teachers, but I know many of them derived great benefit from their dance training. It is a wonderful thing to see shy adolescents blossom once they start to realise the joy of performing and the fitness benefits to be had from ballet training.

Me, performing, aged 28I started teaching as an off-sider to Miss Joan Ashton in Liverpool, NSW, shortly before my fifteenth birthday, so I have taught ballet and related genres for over sixty years. I haven’t taught non-stop, of course – I took time out from teaching to perform in my early twenties, but thereafter I taught whenever I could, household tasks and child-rearing duties permitting. I have taught in three Australian states and in Auckland, New Zealand. Ballet has long been my first love, and I hope I have imparted that devotion to many of my students. As far as I know, none of them became professional dancers or teachers, but I know many of them derived great benefit from their dance training. It is a wonderful thing to see shy adolescents blossom once they start to realise the joy of performing and the fitness benefits to be had from ballet training.So what shall I do instead? I shall attend dance and exercise classes for elderly folk, and I am not averse to teaching casually if asked. And, of course, I hope to write more – book three of The Talismans is just starting to take shape, but I need to put in many more hours of thinking and typing before it goes to press. So maybe I haven’t retired – I’ve just switched to a different stream!

Any funny stories to tell about my dancing life? Well, one certainly comes to mind. Once, when conducting a pas de deux class, I was teaching the boys to lift their partners, then turn around and put the girls down gently. That being accomplished, I started to move on by saying, ‘All right, gentlemen, when you have finished doing the girls over…’

The students were almost rolling on the floor with laughter, and I’m not sure we ever did finish that dance.

Published on December 06, 2018 17:26

November 24, 2018

Memories of schooldays

I have been very remiss in regard to blogging lately! The back end of any year is always busy, but this year I seem to be swamped with one thing after another. The most recent event has been a trip to Sydney for the centenary celebrations of my Alma Mater - Sydney's Conservatorium High School.

I was an incredibly lucky fourteen-year-old to get into what might be Australia's most exclusive school. To be accepted, students have to be studying with one of the wonderful music teachers at 'the Con'. My family had only recently moved to Sydney and I hated the local high school which I had been attending for a term or two. When I heard about the 'Con High' I leapt at the chance to go to a school that was more suited to my interests and abilities.

My musical ability is only one or two points above mediocre, and the fact that I didn't start taking lessons until I was eleven didn't help. However, when I auditioned before the education department's head of music, Terence Hunt, I played my old stand-by, Fur Elise, and Professor Hunt informed my mother that I showed no sign of genius but I could probably become a high school music teacher if I worked hard. (I had expressed a wish to take up music teaching to my mother, but in fact I really wanted to be a dancer - that's another blog post on its own.)

My recent visit was the first in about thirty years - a get-together for the centenary of the school. Only one of my classmates was there - Adrienne Bradney-Smith - and we had a rare old time sharing our life stories since those long ago schooldays. I don't know what has happened to most of our contemporaries, but I do know that at least two have passed away this year. (See my post 'A dear John Letter' from May 10 last for the first sad loss.)

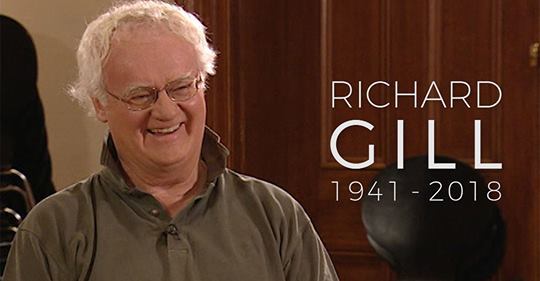

The other death was that of the incomparable Richard Gill, whom I only knew slightly as a highly talented con student. Richard went on to become one of the country's most highly respected conductors and music educators: in fact, some twenty-odd years after I left school he auditioned me for the Musical Theatre course at the Western Australian Academy of Performing Arts! However, the course did not run that year due to staffing difficulties, so I was accepted in to the Dance course instead. (Photo from the ABC)

The other death was that of the incomparable Richard Gill, whom I only knew slightly as a highly talented con student. Richard went on to become one of the country's most highly respected conductors and music educators: in fact, some twenty-odd years after I left school he auditioned me for the Musical Theatre course at the Western Australian Academy of Performing Arts! However, the course did not run that year due to staffing difficulties, so I was accepted in to the Dance course instead. (Photo from the ABC)Swings and roundabouts, roundabouts and swings...

Published on November 24, 2018 23:38

September 22, 2018

A mini-review of a brand-new play!

I haven't been doing much reviewing over the past year, but last week, a friend took me to see a brand-new Australian play. A trio, led by the playwright/actor Andrew O'Connell premiered Stuck, O'Connell's first venture into writing for an ensemble.

It was not obviously a 'first play'. The actors were confident and well-settled into character. In fact, it is apparent that O'Connell had these actors in mind when he sat down to write, since Tatiana Dunn is a real, live Columbian, typecast as Violetta. The third character, Anne, was played by Sylvia Comes, another actor/playwright with experience in Britain as well as Australia.

The ensemble has taken the name 'Company O', in honour of Oscar Wilde. I hope the name brings them good fortune - and plenty of performance work. So far, so good - they are starting a run next week at the Sydney Fringe. I hope they might turn up in the Perth Fringe as well, as I would happily watch Stuck again.

Sydneysiders, do go and see this play if you can. We don't see enough original Australian plays, and Company O deserves kudos for their work on Stuck.

Published on September 22, 2018 03:24

September 2, 2018

The Cloak of Challiver, Chapter 5

I hope you're enjoying this serialisation of The Cloak of Challiver. This is the last excerpt for now - like all authors, I hope to see interest turn into sales so I can write more books!

I hope these first five chapters have whetted your appetite! And, of course, do feel free to write a comment if you like.

You can purchase the novel here on Amazon.

Chapter 5* * *Kitrel was back! Linvar had made a point of calling in on Nevran once a week or so, ostensibly to enquire as to the progress of the barley crop, but all the time longing for news of Kitrel. And suddenly, she was back, even prettier than Linvar remembered her. Her arms were as warm and open as ever. It took no persuading to get her to meet him in the old shed at the edge of Adifer’s holding.

Chapter 5* * *Kitrel was back! Linvar had made a point of calling in on Nevran once a week or so, ostensibly to enquire as to the progress of the barley crop, but all the time longing for news of Kitrel. And suddenly, she was back, even prettier than Linvar remembered her. Her arms were as warm and open as ever. It took no persuading to get her to meet him in the old shed at the edge of Adifer’s holding.‘I had to make all kinds of excuses to get Mam and Da to let me come,’ she told him, holding both his hands and gazing up into his eyes. ‘But finally they let me, and oh, Linvar, my lord, I have missed you so much.’

Linvar pulled her into his arms and down to into the hay. He slid a hand up her leg to caress her thighs and the warmth of her moist cleft. Her legs parted eagerly as she started untying the fastenings of his breeches.

He had learnt a lot about lovemaking with Kitrel. They had learnt together, in fact, and he now knew to take his time over foreplay if she was to enjoy the act to the fullest. But this time he was unable to hold back, and he came within a few breaths of entering her.

‘I’m sorry, love,’ he said as he rolled off her, panting. ‘I’ve been Kitrel-starved for weeks. Next time will be better, I promise.’

Kitrel sat up and grinned at him. ‘Kitrel-starved, eh, my lord? But not, I take it, Janny-starved or Gitta-starved or Lady-Muck-of-Dunghill-starved?’

Linvar shook his head. ‘There hasn’t been anyone else, Kitrel. I don’t want anyone else. But my father is starting to make noises about finding a wife for me, and I’m not happy about it.’ He ran a hand down one soft arm and clasped her hand. ‘I only want you, Kitrel.’

He pulled her down atop him and eagerly she straddled his hips. He was hard again already and he groaned as she guided him into her. She rolled her hips and he gasped, then she began to slide back and forth, tightening her inner muscles…

He came quickly again, but not too quickly. They climaxed together and collapsed into a soft embrace. ‘Kitrel, I cannot live without you’, he murmured, stroking her hair. ‘I will take a house in the town for you, and we can see each other as often as we like, even when I’m married.’

Kitrel pushed him away and sat up. ‘No.’

Linvar propped himself up on one elbow, reaching out to caress her thigh. ‘Kitrel, why not? I will make good provision for you. You’ll have servants and fine clothes, and every woman in town will envy you for being my mistress.’

‘I’ll not bed another woman’s husband. While you’re single it’s all well and good, but you’ll not need me once you’re wed.’

‘But Kitrel, I love you!’ It was the first time he’d said that to anyone and suddenly he felt as if he’d ripped open his chest and showed his heart to a harsh world that would just laugh at him.

But Kitrel did not laugh. She stroked his cheek and smiled sadly. ‘And I love you, too, Linvar. If there wasn’t this difference in our stations I’d willingly live with you forever, but not when you’re married to someone else. Let’s just enjoy what we have, while we have it.’

Linvar felt the open space in his heart close as tight as the chamberlain’s money chest. He got to his feet and adjusted his clothing. ‘If that’s all you have to say, better to end it now,’ he said.

And with that, he walked out of the barn, whistled to his horse, mounted and rode away, his heart lying as heavy in his chest as one of Adifer’s millstones.

Her parents, she knew, were concerned. ‘All that study has turned her brain,’ she had heard her father say. ‘And now it’s serving on tables. Our family’s been fletchers time out of mind. That lass needs to find herself a nice fletcher’s son and settle down.’

But Vanrel had another secret. She was in love — and not with a fletcher. She had renewed her acquaintanceship with Tommavad and Spirivia. The more she saw of Tom the more attractive he seemed. He had a kind of brightness to his skin that she’d not seen in ordinary mortal boys. And his golden hair almost seemed to glow in the sunshine. Yet he could take on mortal form when it suited him, and any other shape he fancied, too. Spivvy no longer appeared as half mortal, half feline, but as a cheerful brunette with long plaits. Vanrel thought of the pair as her best friends.

But Tom was more than a friend now. One day, Vanrel had run into him on his own, and they had spent a delightful hour beside the stream where they had first practised scrying. When they got up to leave, Tom had taken her hand to draw her to her feet, and the tingling in her fingers lasted for hours afterwards. Since then, they had met — not quite accidentally — several times, and had progressed to holding hands and a little tentative kissing and cuddling. They had not done any more scrying together. They had other things on their minds.

Between canoodling and waiting on tables, Vanrel barely had time to fit in a few hours’ work for her father now and then, let alone study with Ven Istrovar. As for that silly idea of becoming a nun — why would any woman want to do that, when there was a young man with strong arms and a persuasive lilt to his voice, just waiting to introduce her to heaven knew what forbidden delights? Vanrel was a new woman. She hummed love songs as she went about her work, her mind only half on the task in hand. The other half was yearning for the next meeting with Tom, in the bushes beside the stream.

A week or two later, Vanrel and Tommavad were lying in close embrace in their hideaway by the stream. Vanrel had long since realised the problems of loving an elvishman. She could not take him home and introduce him to her parents as a likely suitor, nor could she boast to her girlfriends of his strength and his prowess in shape-changing. And what prowess he had! He would change into a bat or a bird or a bee or a terrifying monster, sometimes to amuse her, but, Vanrel thought, sometimes to taunt her and even scare her witless.

Yet physically, he delighted her. She had finally given in to his importunate pleading and given up her maidenhead, but now that was cause for as much worry as delight. What would happen to her if she got with child by an elvishman? Her parents, she was sure, would never forgive her, and no man would marry her with a half-caste bastard clinging to her kirtle. She shuddered when she thought what the future might bring, but as with the scrying stone, she felt powerless. How could she live without Tom and his lovemaking? No ordinary mortal man could compete with him in Vanrel’s eyes, and the very thought of bedding with one of the lads about the castle disgusted her.

‘Fancy a trip to Shentak?’ Tom stood up, stretched and held out his hand to pull her to her feet.

‘Shentak? How can we go to Shentak? It’s in Challiver, Tom! That’s half a day’s sail and you have to pay to go on a ship.’

Tom grinned. ‘You grumlees might have to go by ship and pay for it, but I can take you there for nothing. I’ve been working hard on my space-shifting and I know I can get us there and back, safer than any ship.’

Vanrel was doubtful. ‘Have you done it before?’

‘Yes, on my own, and with Spivvy, so I reckon I can get you there and back again. Come on, where’s your sense of adventure? You grumlees are a mob of cowards.’

‘This grumlee’s no coward,’ Vanrel retorted. ‘Come on, then, show me your amazing space-shifting trick.’

Tom took her hands and shut his eyes, mumbling some funny foreign-sounding words. All at once, Vanrel felt herself being lifted up and spun around, yet it felt completely safe, like lying on a fuzzy warm blanket in the dark. Then she lost consciousness.

She came to in a dark place. Her feet were firmly on the ground and Tom was still holding her hands. ‘Where are we?’ she whispered.

‘In the cellar of an old inn in Shentak,’ Tom said. He squeezed her hands and let them go. ‘It’s an abandoned building, so there’s no one around.’ He took one of her hands and led the way up a flight of stone steps to open the door at the top.

Vanrel blinked as daylight assaulted her eyes. The door opened onto the kitchen of an old inn. It looked as if no one had been there for years. The fireplace was cold and dirty, and the window shutters hung from rusty hinges like rags. Outside, there were sounds of shouting and laughter, of clutter-clatter and more shouting.

‘It’s market day!’ Tom exclaimed. ‘Wait a moment while I get money so we can have some fun’ He fell silent with closed eyes silently mouthing words.

He was casting a spell. It had frightened Vanrel the first time he’d done this in front of her, but now she accepted it as a matter of course. He put a hand to his belt and produced two silver coins.

‘There’s a meal and maybe a mummer’s show for both of us. Come on, let’s go and join the party!’

He bought Vanrel a green ribbon for her hair, and they shared a meat pie. Then they went to the inn for a pint of ale apiece, and then, in cheerful mood, they watched a play about a demon trying to seduce a miller’s wife, but she got the better of him and dumped him in the river in a barrel. They laughed as they left the marketplace, holding hands.

‘Let’s walk along the highway for a bit,’ Tom suggested. “You don’t have to be home early or anything, do you?’

‘No, Vanrel lied, thinking of all the tasks she was neglecting in father’s workshop. ‘I’d like to see a bit more of Challiver.’

So they strolled along the highway for a while, eventually turning off onto a side road that led to a patch of woodland. It looked like a perfect space for a spot of canoodling. But no sooner had they sat down under the sheltering trees than there was the sound of tramping feet coming down the lane. Vanrel gripped Tom’s hand. ‘Whatever is that noise?’

‘I’ll go and take a look.’ Tom let go of her hand and immediately disappeared.

Vanrel peered tentatively through the branches of a shrub. There was no sign of Tom, but there were soldiers aplenty, marching five abreast behind their mounted commander, his knights and their squires. What a fine sight they made!

Once the troop had passed, Tom reappeared at her side. ‘Those are elvish warriors,’ he announced. ‘Did you notice that they were wearing bronze mail? And the horses — did you ever see the like?’

Vanrel had to admit she had not. Although the horses were caparisoned for battle, they seemed lighter, friskier, than the heavy coursers of King Beverak’s guard.

‘A man could ride a hundred miles a day on a horse like that,’ said Tom with awe in his voice. He turned to Vanrel and hugged her. ‘I’m going to see if I can join them! I’ll bet that was Sir Jedderin himself leading them!’

Vanrel was nonplussed. ‘Who is Sir Jedderin?’

‘He commands King Auberin’s guard.’ Tom hugged Vanrel again. ‘I want to ride with a column of men like those. I want to fight for King Auberin. It’s what I’ve always wanted to do, but Mother didn’t want me to. Now I’m sixteen I’m old enough to make up my own mind, and if she makes a fuss I’ll run away. Come on, we have to get back so I can tell my father.’

And with that, Tom grabbed her hands and gabbled the spell to take them back to Rannerven.

This pair, however, surprised him. The man was respectful without being obsequious — and who could fail to be moved by the boy’s eagerness?

‘I know I’m young, sir, but I’m nearly seventeen. I’ve always wanted to go for a soldier, sir, but I didn’t know how to set about it. Please sir, let me join you.’

Jedderin shook his head. ‘I can’t take you into battle, Tom, with no training in arms. Do you know what it’s like? Can you imagine the man next to you with his guts spilling on the ground as he dies? Can you imagine fighting for your own life, calling on all the spellcraft at your disposal as well as all your skill at arms? And you will be away from home almost all the time, sleeping rough, living off the countryside and hardly ever even able to wash yourself and your clothing.

‘I still want to go, sir. I want to serve King Auberin. It’s what I’ve always wanted.’

‘What about your mother? Can you imagine how much she’ll miss you? And I’ll wager a fine lad like you must have a sweetheart or two.’ A thought struck Jedderin. ‘You don’t just want to join the army because you’ve got some girl into trouble, do you?’

‘Oh, no, sir. I do have a sweetheart, but nothing serious. She’s a grumlee.’ Tom spoke almost dismissively. Jedderin sighed.

‘Ordinary mortal women have feelings too, Tom: probably more than you, if truth be known. All right. You can come along on this exercise, and if you bear up all right I’ll take you back to Stavershall and we’ll see what we can make of you. But don’t come whining to me the first time you have to sleep out on the moors in a thunderstorm or go without food for three days. Understand?’

Tom almost danced a little jig in his excitement. ‘Yes, sir, I understand. And I’ll work hard sir, harder than anybody. You won’t be sorry you took me, sir, I promise you.’

Jedderin shook hands with Tom’s father. ‘Come back in a week. If Tom has changed his mind, you can take him home. If not, you can sign him on.’

No sooner had his father departed than Tom sensed someone calling his name. It took him a moment or two to realise that it was not someone in the elvish encampment, but someone a long way away, mind-calling him. A woman. It was Vanrel.

How could a grumlee mind-call him? And in any case, Vanrel wasn’t nearly so important to him that he should pick up a mind-call from her. It just shouldn’t happen. Yet it was as if he was there beside her, sitting by the stream where they had so often made love. She was crying his name out loud. She missed him. She wanted him back. Why had he left her?

Tom felt uncomfortable. He was a soldier now. He couldn’t just up and leave camp without serious consequences. It wasn’t as if he was in love with her, or anything soppy like that. She was just a grumlee girl who had been silly enough to get a crush on him. He ignored Vanrel’s calls.

She didn’t give up easily. For the next few days, he heard her crying at all sorts of times, day and night. Finally, he mind-called his sister.

‘Spivvy,’ he asked her, ‘can you find out what’s wrong with Vanrel? I don’t want to come back and I wouldn’t be allowed, anyway. If there’s something wrong with her, see if you can fix it. And make her understand I’m not coming back.’

‘Very well, brother,’ came the reply. ‘I’ll go and look for her tomorrow. If it’s something I can deal with, I will.’

Tom breathed a sigh of relief. After all, he was finished with Vanrel. Besides, he was busy learning to be a soldier.

The next day, she found Spirivia waiting at the streamside.

‘He’s gone to Dresnia with Sir Jedderin,’ Spivvy replied in response to Vanrel’s anxious questions. ‘He’s joined King Auberin’s army.’

‘Who’s King Auberin?’

‘Our king. The elvish king of these islands. Father was proud of Tom for going, but Mother hasn’t stopped crying since he left.’

Vanrel slumped against a tree in a wash of tears. ‘Oh, Spivvy, what am I going to do? I think I might be with child by Tom. My father will kill me. What will happen to me?

Spirivia shrugged. ‘You’ll have a baby, of course. You should have thought of that before you started to make eyes at our Tom.’

‘I did not make eyes at him! He was the one that started it.’ Vanrel’s face worked in anguish. ‘He said he wouldn’t love me if I didn’t…’

‘Love you? Elvishmen don’t love grumlees, stupid. It serves you right for being so easily deceived.’

Vanrel knew by now that ‘grumlee’ was a rude epithet applied by the elvish kind to ordinary mortals. She had always winced when Tom called her that, but had pushed the hurt feeling aside. She should have realised then that Tom had been using her. She felt alone, terribly alone, and so foolish! The word ‘betrayed’ came into her mind. That was what she was feeling. Betrayed. Betrayed by Tom, betrayed by Spirivia, and if she were honest, betrayed by herself. Cruel as Spivvy’s words were, they were right. If she had the time again, she would behave differently. She remembered something Ven Istrovar had once said, something about ‘the wisdom of hindsight…

Spivvy was avoiding her gaze, but finally she looked at Vanrel with something like pity. ‘Come again tomorrow, and I’ll have something with me that will bring on your bleeding. Mother’s given it to grumlee girls before, and I know where she keeps it.’ Then, suddenly anxious: ‘But you mustn’t tell anybody. Not anybody at all. We’ll both be in terrible trouble if anyone finds out. Understand?’

Vanrel nodded, biting her lip. ‘All right. Same time tomorrow. You won’t forget, will you?’

‘I won’t forget. But you be here on time or I’ll go straight home.’

And Spivvy was waiting at the usual place holding a tiny folded paper package. ‘Take as much as will fit on a half-copper coin,’ she said. ‘And if you don’t bleed the next day, take the same amount again the next night. And if that doesn’t work then it’s just too bad, because there’s nothing else can be done.’

Vanrel muttered her thanks, headed for home and sneaked back into her room, where with shaking hands she carefully measured out the powder Spirivia had given her. She mixed it with watered wine and drank it down.

A wave of nausea overcame her. She thought she would vomit then and there, so foul was the taste, but she forced herself to lie down quietly until the sickness passed.

The next day, her bleeding came. It was dreadful. Her stomach cramped, her body swung between hot and cold, and wave after wave of nausea, worse than any she had ever experienced, assailed her all day long.

Her mother, deeply concerned, brought her hot stones for her aching back and herbal possets that Vanrel couldn’t drink. She lay on her pallet, face to the wall. How could she ever face her parents again? Finally, she cried herself to sleep.

When she awoke the next morning, the pain had gone, to be replaced by exhaustion and guilt. She had knowingly and deliberately killed her own child, hers and Tom’s. To atone for it, she knew what she had to do. She must devote herself to the service of the Lady.

‘Dear Lady,’ Vanrel prayed, ‘let me serve you by serving children. Let me be as a mother to motherless little ones.’ Weak and shaking, she got up and went to pray in the chapel, convinced that the Lady would find a way to put this terrible experience to good use.

Vanrel would, after all, become a nun.#

Published on September 02, 2018 00:05

August 28, 2018

The Cloak of Challiver, Chapter Four

Chapter 4 ( I hope you're all still following!)* * *Lyrien yawned as she squinted into the morning light. Her harness jingled with her pony’s trot and on her left, Ullavir’s tack played a deeper counterpoint. Behind them, two or three of her ladies were singing. Strange, it was, the way the fine weather made people want to sing. Lady be thanked, the weather was holding fine for their journey. In two days she would be home. It was quite an honour, really, that her father sent her on courtesy calls to his eldermen. It showed he thought her mature enough to discuss matters of state with discretion and confidence. But this expedition to the elderman in Chitterven, minor though her task was, had proved long and tedious, and she would be glad to be home. They were nearing the Midlands border. Tonight would see them at Midlands Castle, and tomorrow they would continue on to Rannerven.

She turned to the old trouper at her side. ‘Is it far to Kettering, Ullavir?’

‘Just round this bend, your highness. If we take no more than an hour to break our fast, we’ll make Gellatherak by dinner time and Midlands Castle by sunset.’

‘That’s good. I’m hungry. Oh look, you’re right!’ They had rounded the bend and suddenly, the highway, which had taken a steep downhill turn, had become the beginnings of Kettering’s main street. ‘Where’s the inn?’

‘The one your father always stops at is on the other side of the township, madam. Have patience: it’s less than half a mile now, and the men we sent ahead will have ordered a meal and cleared the taproom.’

Lyrien grimaced. ‘I feel uncomfortable, ordering other travellers to make way for our party.’‘There won’t be many people on the road this time of year, madam, and those that are won’t be put out for long.’

Ullavir was right, but his words did nothing to lessen Lyrien’s discomfort. Sometimes she wished she’d been born common so she wouldn’t have to inconvenience anyone or feel self-conscious because of the fine clothes she wore and the high-stepping palfrey she rode. That was one of the worst things about being a royal. People had to give way to royals, even sick people, and old ones, and mothers about to give birth. Still, at least it meant she always had enough to eat, and right now she was hungry! Ullavir had insisted that they leave Chitterven at dawn with nothing in their stomachs but a bite of bread and a beaker of warm, weak, ale.

‘There we are, your highness. I told you it wasn’t far.’ Ullavir pointed to a half-timbered building fifty yards down on the left. Considerably more substantial than the wattle and daub of nearby cottages, the place looked clean and well cared for, with its brightly painted sign depicting a sheaf of grain blazoning forth a welcome. As they approached, grooms hurried to take their mounts and the landlord himself stood on the step, bowing, his hair slicked back and a fresh white apron girthing his bulk.

Ullavir dismounted and was about to hand over his horse to one of the men when, all at once, the orderly welcome was turned on its ear. A stray goat, its keeper hard on its heels, charged in front of Lyrien. Her horse shied and whinnied and someone on her right grabbed her reins.

‘Whoa there, girl, it’s all right.’

Lyrien was about to retort that thank you very much, she could handle her mount herself and would whoever it was please let go, when she looked down. Her voice promptly deserted her, for she was staring into the bluest eyes she’d ever seen. The beautiful orbs were set in the handsomest face, which was topped by wavy golden hair that put the primroses to shame. The hand that held her reins was lean and strong-looking, with clean, trimmed nails. Its owner, clad in mail topped by a surcoat that bore an unfamiliar device, was no groom.

‘Wretched animal,’ the mail-clad vision said with a smile that showed off two rows of perfect white teeth. ‘Here, my lady, let me help you down.’ And before Lyrien could gainsay him, those fine strong hands were encircling her waist and she found herself lifted to the ground.

She was unable to step back, for the stranger knight had her trapped between himself and her horse. He did not take his hands from her waist at once and his eyes were brimming with admiration. Lyrien blushed.

‘Excuse me, sir. I thank you for your assistance, but I must join my ladies.’

The hands removed themselves at once and the golden hair moved back a pace. ‘I crave pardon, my lady. I was overwhelmed by your beauty. Pray forgive me.’ He looked around. ‘Your party is already entering the inn. Shall we join them?’ He offered his arm and it was the easiest thing in the world to take it and let him lead her to where the landlord was waiting and her guards and ladies were crowding through the door.

‘Your highness!’ The landlord bowed lower than ever. ‘Permit me to welcome you to The Oatsheaf. Rooms have been prepared for you and your party to refresh yourselves before breakfast.’ He turned to the golden-haired vision of knighthood at her side. ‘Sir Pirstad! I did not realise you were waiting for her highness. Come in, come in.’

Lyrien could not find it in her heart to protest that she had no idea who her companion was. After all, it wasn’t really improper, was it? He had done what knights are supposed to do in looking out for her welfare. And he was so handsome…

When they reached the door of the chamber where her women were waiting, the heroic vision squeezed her hand. ‘I’ll see you at breakfast, your highness,’ he whispered.

‘Of course, Sir Pirstad.’ Lyrien’s heart was beating faster than if she’d run all the way down the spiral staircase that led from her bower to the Great Hall at home. What a beautiful, beautiful man!’Her ladies fussed over her hair and gossiped as they always did, but strangely, no one mentioned Sir Pirstad or the runaway goat. But when they made their way down to the taproom, and Sir Pirstad was waiting for her by the door the ladies-in-waiting were all blushes and coy smiles. A delightful shiver ran up Lyrien’s arm when he took her hand. As he led her to the head of the long table, Lyrien was sure she was glowing more brightly than the sunshine that reflected from the polished table tops. He handed her to her place at the head of the table and took the seat to her right just as Ullavir strode in.

The old guardsman stopped short at the sight of the strange knight, but only for a heartbeat. He marched over to Lyrien and confronted Sir Pirstad, hand on his sword. ‘Who are you, Sir Knight? I had no orders that we were to meet anyone here.’

Lyrien felt sorry for Ullavir. His job was to protect her from harm, and a stranger attaching himself to a royal entourage had to be challenged. But how to challenge a man who already seemed familiar with his charge? Poor Ullavir was obviously nonplussed.

‘It’s all right, Ullavir,’ she began, but Pirstad interrupted by rising to his feet.

‘Sir Pirstad Stormshore at your service, Sir Ullavir. I took the liberty of assisting her highness in a most unfortunate incident with a runaway goat and she was kind enough to invite me to dine with your party.’

‘Yes, where were you, Ullavir?’ Lyrien joined in the game with glee. ‘A goat spooked my horse and I could have been thrown.’ She regarded Ullavir reproachfully. ‘It’s fortunate Sir Pirstad was there to help.’

Ullavir faltered. ‘Pardon, your highness. I… I did not see the animal. It must have been while I was giving orders to the grooms. And I thank you, Sir Pirstad, for your timely intervention.’

Sir Pirstad inclined his head graciously. ‘I am honoured to have been able to help.’ He made room for Ullavir to sit beside him and quickly engaged him in conversation. It wasn’t long before Ullavir was also under Pirstad’s spell and the meal proceeded with much merriment. Over a pint of ale at the end, Pirstad led them all in singing The Flowers of Sproutingmonth, casting admiring looks at Lyrien whenever the chorus rolled around.If all the flowers of SproutingmonthWere growing by my doorThere’s only one that I would pickAnd keep forevermore.Every time they sang the line ‘There’s only one that I would pick’ Sir Pirstad smiled at Lyrien and she blushed pinker and pinker with every passing verse.There was no question but that Sir Pirstad should ride with them as far as Gellatherak, where, he said, he was to visit a friend’s manor. He rode at Lyrien’s left all the way. They chatted about music, and Lyrien was delighted to find they had similar tastes.

‘I really like the work of that Aristandian troubadour, Goffray de Mardell,’ Lyrien confided. ‘His Dream of the Golden Valley is my favourite song!’

Sir Pirstad agreed. ‘A lovely piece indeed, although I’m also fond of his Love in an Autumn Forest. Have you heard it, your highness?’

Lyrien hadn’t, so he sang it for her. After that he went back to The Flowers of Sproutingmonth, and Lyrien blushed more than ever.

When the town of Gellatherak loomed into view Lyrien’s heart sank. Her hero was leaving! But as the party reined in to bid him farewell, he took Lyrien’s hand and kissed it.

‘I shall see you again your highness,’ he whispered. ‘Very soon, I promise.’Lyrien got up and began to dress. It was still early. No sign of her ladies yet. That was good. Having people fuss over her was another of the trials of being royal. Being an elderman’s wife would be much less constraining.

But what if Pirstad really didn’t like her that much? The thought was too alarming to countenance. Of course he liked her. And hadn’t he said he would see her again, very soon?

Dressed in a simple stuff gown for another day in the saddle, and her hair neatly plaited, Lyrien made her way downstairs. Uncle Dristed’s talk was all of hopes for a better harvest this year than last, and the relative prices of oats and barley. Boring! Lyrien continued to daydream of Pirstad’s blue eyes and the feel of his hands at her waist.

Perhaps they would meet Pirstad along the way. They would have to stop somewhere for dinner, after all. She giggled behind her goblet. Maybe there will be another stray goat… Whinnies from the horses quickly became shrieks of fear. Her mount wheeled one way then the other, pulling at the reins. It was as much as she could do to hold her seat. Glimpses of fighting behind and before told her both ends of the column were being attacked, but her eyes refused to believe what they saw. Men, dozens of them. But were they men? They were man-shaped, but short, less than her own height. What they lacked in height they made up for in girth. Dark shaggy hair hung to their naked shoulders and what looked like wolf pelts covered their hips and upper legs. Some were firing slingshots from among the trees while others at close quarters were laying about them with swords.Dwarves. Surely not! Dwarves belonged in stories. They didn’t just appear out of nowhere, firing slingshots...

The guards fought desperately, but they were hopelessly outnumbered. Several were felled by stones from slingers in the trees, their comrades were unhorsed, their mounts slain by dwarves on the ground. The harsh tang of blood filled the air and Lyrien’s horse panicked. Desperately, she clung to the reins as the animal bolted back down the road the way they had come. A dwarf grabbed at the bridle as she passed but the horse reared and he backed off. Another tried, and was trampled for his pains. Lyrien closed her eyes and hung on, screaming.

Then all at once there was calm. Her mount stood still, head down, its breath heaving. Someone had hold of her bridle, murmuring words of endearment.

‘It’s all right, Lyrien, my little princess. It’s all right. Come now, come with me.’ She opened her eyes to find Sir Pirstad lifting her from her own saddle and onto his mount, where she clung to him, sobbing. He turned his horse’s head towards a gap in the trees where a narrow path opened before them. The noise of the fighting receded as they made their way into the forest.

‘Where are we going?’

‘Somewhere safe,’ said Pirstad. ‘Just relax and let me take care of you.’

‘What about the others? What about Ullavir?’

‘Ullavir can take care of himself. It’s what he does for a living, remember. Just be glad you are safe. You aren’t hurt, are you?’

‘No. At least, I don’t think so.’

‘That’s good.’ A gentle kiss brushed her brow. ‘I wouldn’t have you hurt for the world.’ Pirstad’s left arm tightened around her waist and she snuggled against his broad chest. How strong he was, and how kind.

‘I was lucky that you happened along at just the right time, Sir Pirstad.’

‘I told you I would see you again, didn’t I? Rest now. It’s not far.’

Lyrien lost track of time and distance. The motion of the horse, the jingle of the harness and the crunch of leaves under the horse’s hooves were calming. She found herself dozing. At one point, her dress must have caught on a branch. She heard the tearing sound and what sounded like a muttered curse from Pirstad, but he pulled the fabric free and pushed his mount through the encroaching undergrowth.

‘Look, here we are, safe and sound.’

Lyrien lifted her head and looked around. They were entering an enormous clearing, in the centre of which stood a sturdy timber building. Lyrien guessed it was a hunting lodge. Her father owned several similar ones in various parts of the country.

‘Whose is it?’ she asked.

Again the fluttering kiss to her forehead. ‘Ours, for now. Hold on while I dismount. It’s a long way to the ground.’

It was indeed a long way, but Pirstad lifted her, light as a feather, and carried her the rest of the way, up to the door of the lodge. It wasn’t locked.

Once inside, Pirstad set her on her feet. They were in a cosy hall with a dining table and several comfy-looking padded chairs. The only window was set high in the wall over the door, clerestory-style. An inner door opened off to one side, while opposite, an archway led to another part of the house.

It was as if they were expected. A fire glowed in the hearth and there was food on the table: cheese and fruit and nuts and pastries as fine as anything she’d had at any castle in the Islands.

‘Sit down, my princess,’ said Pirstad with a gallant bow. ‘Shall I pour us some wine?’

Lyrien realised she was terribly, terribly thirsty, and she drank the wine Pirstad poured almost in one draught.

Pirstad pushed a plate of pastries toward her. ‘Here, eat something, your highness. It’s not good to drink so much wine on an empty stomach.’

Lyrien took a pastry and bit into it. It tasted delicious, and she took a second bite. Something was niggling at the back of her mind, something about Ullavir and the rest of her party, but it all seemed a long way away and so unimportant…

She finished the pastry but realised she was more tired than hungry. So tired, all she wanted to do was close her eyes…

‘I’m sorry. You’ve had a bad experience, and you’re weary.’ Pirstad pushed himself from the table and held out his hand. Come, I’ll show you where you can rest.’

Obedient as if she was six years old and her nurse was calling her for bed, Lyrien stood up with a sleepy smile and, clasping the proffered hand, she allowed Pirstad to lead her through the inner door.She briefly considered scrying for them but dismissed the idea. What was the point? They were gone, hidden by Norduria’s filthy magic somewhere in the wilds of Challiver, and Ellyria told herself that she didn’t care where they were.

But I do care. I should care. Where they are, there lie the Dark Spirit’s plans.

Maybe she should try again…

Sighing, she set up her scrying bowl, knowing she would be no more successful than before. The water lay obdurately clear, showing only the smooth bronze of the bowl’s inner surface. She was about to give up when suddenly, the surface clouded.

But when the milkiness cleared, it did not show Fiersten and Norduria. It showed Ullavir, beside a forest-lined roadway, battling a dwarvish raider.

Lyrien…

Ellyria gabbled the spell, and the space-shifting vortex seized her up and carried her away.She opened her eyes to a scene of carnage. Horses reared and screamed and somewhere behind her, women were screaming too. A dead man lay at her feet, his head half severed. He wore the livery of Beverak’s guard. Barely an arm’s length before her, Ullavir ran his sword through his opponent’s belly. The dwarvishman screamed and fell to the ground.

Ullavir stepped over the dying dwarf. ‘Your majesty, he panted hoarsely. ‘You should not be here.’

Ellyria did not reply. She was busy creating the biggest binding spell she’d ever had to cast. And where was Lyrien? There was no hope of finding her, dead or alive, amid this mayhem.

Ullavir turned to face another dwarvish fighter just as Ellyria’s spell took effect on those closest to her. She could not possibly stop the battle all at once. She had to tackle it little by little, starting with the individual fights close at hand and gradually widening the spell’s net.

And little by little, it worked. Dwarves froze in full fight or flight, while Ullavir’s men lowered their swords in amazement.

Ullavir looked around at her handiwork and then gazed at her, awe-struck. ‘You’ve frozen them, your majesty. Are they dead?’

‘No, Ullavir. At nightfall they will move again. May the gods grant they return to their underground caverns and not come back to harm anyone even one more time.’Ullavir, however, was not listening. He was turning this way and that, looking for something. Or someone. ‘The princess — where is she?

Ellyria’s eyes already sought the familiar tawny hair and rosy cheeks of her granddaughter, but there was no sign of her. One of the women limped up, weeping. ‘Where is your mistress?’ Ellyria demanded. ‘Where’s Princess Lyrien?’

‘Her h-horse bolted, madam, quite early in the attack. Last I saw it was tearing back up the road towards Midlands Manor.’

‘She could have been thrown!’ Not waiting for a response, Ellyria began to run in the direction the weeping woman had indicated. Ullavir was hard on her heels, but she managed to lose him by dodging through a group of frozen dwarvishmen at the first bend in the road. She took refuge in a thicket as Ullavir thundered past. Then she took starling form and flew.

Half a mile down the road, a riderless mount grazed the verge. With her starling’s eyes, Ellyria glanced past the horse to an overgrown path. It had obviously seen little use: branches overhung from both sides and the path itself sported grasses high enough to mow for hay.

But someone had gone up there recently. Snapped twigs hung from the branches and the grass beneath was slightly flattened, as if a by a single horse.

There was magic about. Strong magic: she could almost smell it. Someone wearing a glamour…

The trail was easy enough to follow. Away from the edge of the wood, hoof prints in the sandy track led ever onwards and upwards. Some distance up the path, something hanging on a bush that overhung the path caught her eye. It was a piece of brown stuff. Along one edge fragments of floral embroidery still clung.

Alighting on the path, Ellyria resumed her own form and retrieved the scrap of fabric. She held it up to the dim light. It could be from Lyrien’s brown riding dress.

Heartened, she hastened along the path, even though it was growing steeper by the stride and thorny twigs grabbed her at every step. Two bends later, she pushed her way into a large clearing with a substantial building in its centre. From within came the sound of sobbing.

Ellyria mounted the steps in two bounds and tried the door, without success. It took several repetitions of an unlocking spell to gain entry. She raced across the hall, calling her granddaughter’s name, and flung open the inner door.

Lyrien, naked, lay hunched atop an elaborately carved bed. She raised her head and stared at Ellyria with terrified, unseeing eyes. Ellyria sat beside her and tried to take her in her arms, but Lyrien screamed and pushed her away.

‘Lyrien, my dear child, can you hear me? Lyrien, look at me!’

The sobbing became great gasping breaths punctuated by whimpers. ‘Grandmamma?’ Oh Grandmamma, he hurt me.’

Ellyria put an arm around the shaking white shoulders and this time she was not repulsed. Lyrien turned and collapsed into the embrace, sobbing again, more quietly this time. There was a smear of blood on her thigh. ‘Lyrien, who did this to you?’

‘A m-man, Grandmamma. A knight.’

Half releasing the shivering Lyrien, Ellyria pulled the bedcovers up. ‘Did you know him?’

Lyrien shook her head. ‘Not really. I met him only yesterday. He seemed so nice… but he planned this, Grandmamma. He told me, even as he…’ Lyrien bit her lips and screwed up her eyes.

Ellyria squeezed her shoulder. ‘Go on.’

‘He said to tell you that he can also play the horse breeder, that there are already plenty of little cuckoos. And that Nor-Nordelia? A strange name…’

‘Norduria?’

‘Yes, that’s it. Norduria.’

Ellyria folded Lyrien in her arms as she began to cry again, soft, despairing sobs that told a tale of heartbreaking disillusionment and loss. ‘Did this man tell you his name?’

Lyrien’s whisper was so soft even Ellyria could barely hear it. ‘He said he was Sir Pirstad Stormshore.’

Pirstad. Pierstan. Fiersten. Back on form, now the Dark Spirit is back… Ellyria stood up and retrieved Lyrien’s clothing. Some pieces lay on the bed, some on the floor, all in disarray. The hem of the riding habit was torn, matching the piece Ellyria had found on the bush, but the bodice was ripped to the waist, as was the undershirt.

A little magic mended them. If only broken lives could be as easily rendered whole. Ellyria’s jaw clenched. ‘He will pay for this, Lyrien. And have no fear; there will be no cuckoo in this nest. I shall see to that.’

She stroked Lyrien’s belly in a downward motion, seven times, murmuring a spell as she did so. ‘Come along, my darling. Let’s get you back where you belong.’

It was a long walk back to the road. Ellyria was tempted to space-shift at once to take Lyrien directly back to Rannerven, but that would cause complications. Ullavir and his men, to say nothing of Lyrien’s women, must be hunting for her high and low.

‘Lyrien, my dear, it’s probably best if your party returns to Midlands Manor. I’ll come with you if there’s a spare mount.’ Ellyria bit her lip. Of course there would be a spare: several of Beverak’s men were dead. ‘It might be wise to tell Ullavir and the others that you hid in the forest to avoid the dwarves, without mentioning Sir Pirstad.’

Lyrien just nodded. Her crying had given way to a sad silence that was almost worse, but all Ellyria could do was walk beside her, sending waves of compassion and reassurance and hoping that was enough.

Halfway down the path, they met Ullavir. The relief on his face as he caught sight of them was palpable. ‘Madam, you’ve found her. Praised be all the gods! Your highness, are you hurt?’

Lyrien shook her head. ‘Thank you, no, Ullavir. When my horse finally calmed down I thought it best to shelter in the forest for a while, and Queen Ellyria just happened to be passing. I am quite unhurt, as you can see. We must return to Midlands Castle. Prince Dristed should hear of this attack as soon as possible.’ She turned to Ellyria. ‘Will you accompany us, Grandmamma? I take it your servants have returned to your manor.’

Ellyria regarded her granddaughter with admiration. Where had the weeping, terrified girl gone? This was a different Lyrien, one who had very quickly grown in strength and dignity. ‘Indeed I will, granddaughter, if Ullavir can find me a mount.’

By the time they reached the scene of the battle, the dead and wounded were tied to their horses and Ullavir’s sergeant was readying the party to move off. Ellyria rode with them back to Midlands Castle, where she left Lyrien and her party in the care of Dristed. Then she space-shifted to Rannerven, to explain to Beverak and Tammi that their daughter had been raped.Tammi took his hand. ‘My love, whoever it was, there is nothing we can do without ruining Lyrien’s chances of marriage. We must keep this quiet. Surely you can see that?’

Ellyria stayed silent. She could not bear to tell Beverak the same elvishman that had seduced Polivana all those years ago had also raped Lyrien. Beverak still occasionally showed long-harboured feelings of fear and suspicion of her people, and knowing that his daughter had been forcibly deflowered by one of them could well be the last straw. Perhaps he would even turn her out, his own mother… The possibility of never seeing Beverak and Tammi or their children again was unbearable.

She held her peace while Beverak ranted and Tammi soothed, then quietly excused herself, went to her room and wept.

She fell into a restless slumber, only to be awakened by the feeling that someone — or something — was in the room with her. She opened her eyes to see a familiar shape flickering in the firelight. She sat bolt upright. ‘You! This was your doing, wasn’t it?’

The Dark Sprit smiled its lazy, supercilious smile. ‘Of course. Surely you aren’t surprised, little queen. You must have known I was back.’

Ellyria hugged her knees and stared back into the spirit’s unfathomable eyes. ‘Of course I did. I saw my spell undone in front of my very eyes. I’m surprised it took you so long to surface.’

The Spirit yawned. ‘Oh, I’ve been around, my dear. Laying plans, finding my minions and making them a few promises. Hence the sad business with your granddaughter. Fiersten is easily pleased: just wave a pretty piece of flesh in front of him and he is happy. But Norduria — now, she’s a cut from different cloth. Power is what she’s after, and that makes the game so much more interesting.’

‘What about Nustofer?’

The Spirit shrugged. ‘He wants power, too, but he’s easily diverted by smaller rewards for the time being. But really, my dear, you can’t expect me to share my plans with you. I may be clever, but I cannot read your mind — to me, the fun of this game lies in guessing what you will do next and foiling your plans. Sometimes I have to distract you with side issues, and that might often tie in nicely with the small rewards I give my minions.’

Bile rose in Ellyria’s throat. How could this creature be so evil, so conscienceless? ‘Why didn’t you just take Lyrien as your second payment, and have done with it?’

‘I like to prolong the game, little queen. I might indeed take her another time, but I must congratulate you. Your trinkets are doing their job well, and so far I have been unable to take either of your granddaughters. Fear not: your spells are strong, and providing me with much sport as I try to break them. For break them I shall, you know. It’s only a matter of time.’ And with that the Dark Spirit faded from view.He stretched to ease his aching back. It still troubled him, but not as much as the nagging awareness that the succession would not be assured until Linvar had a son. Better yet, two or three sons. Not all children, even pampered royal ones, would reach adulthood.

But he did not want to marry Linvar to a foreign princess. Oh, he’d been lucky himself in that regard — Tammi was the very best wife he could have had, and there was no likelihood that any of her kinsmen would try to take the throne of Dresnia. All the same, a good local girl would be a safer bet for Linvar, preferably one who had no brothers…

There was a knock at the door and Beverak cursed under his breath. Hadn’t he told them a hundred times to leave him alone when he was working? ‘Who is it?’

It was Lyrien. A pang of sorrow pierced Beverak as he watched her cross the room. She held her head high, but she’d been looking sad and withdrawn for days, ever since that cursed attack in the forest and her suffering at the hands of some stray knight. The worst part was that he couldn’t even seek the bastard out and have him die under the knife that a butcher would take to his balls. Hell, he’d wield the knife himself, given the chance. But Tammi was right. If word got about that Lyrien had been raped, it would ruin her chances of marriage and cast disrepute on the family. It was high time she had a husband. Just as soon as Linvar is safely wed…

Lyrien stood in front of him, hands clasped. That was strange; normally she would take a stool and sit at his feet. He’d never stood on ceremony with his children, and they were always at ease with him.

He regarded Lyrien seriously. ‘What is it, child?

Lyrien swallowed. ‘Father, I want to be a nun.’

‘You want what?’ Beverak almost fell from his chair in surprise. ‘Lyrien, is your brain addled? You are my only daughter. You can’t become a nun. And what sort of life do those women have anyway? Most of them are girls from families too poor to give them a decent dowry, or else they’re sick or deformed and can’t find husbands. We can do better for you than that. A lot better. Why, only last week the Falrouvian ambassador hinted that the king’s uncle was looking for a second wife. Once we’ve found a wife for Linvar——’

Lyrien broke in angrily. ‘Father, it will be obvious to anyone I marry that I’m not a virgin. Have you thought of that?’

‘Don’t be silly, Lyrien. Any old wise woman knows how to fake virginity. A bit of chicken’s blood in the right place and the man will be none the wiser, unless you tell him.’

‘I will tell anyone who comes to court me,’ Lyrien replied. ‘And if he persists, I shall spit in his face. I will never marry. Never. You might as well let me go to the godhouse right away.’

Bile rose in Beverak’s throat and his hands started to shake. He thumped the desk and roared at Lyrien. ‘You just listen to me, daughter! You have been pampered and given advantages all your life, because you are my child and thus a bargaining chip in trade. Your dowry is sufficient for any prince on the continent, or indeed, any in the world. This is what you’ve been bred for and you’ll marry where I tell you!’

‘Is that all I am to you, Father? A bargaining chip?’

Beverak’s anger evaporated as quickly as it had arisen. He put his head in his hands, elbows on the desk, and took a deep breath. ‘Of course not, my pet.’ He paused and looked up again. ‘But princes and princesses have certain duties. Why else have you been cosseted and given every advantage? We have to pay for these things in our duty to the country. And one of those duties is making useful alliances with other lands. Surely you’ve always known that.’

Lyrien turned away and looked out of the window. ‘I did not seek those advantages, Father. In fact, I despise them. Why should I ride while others walk? Why should I always take the best feather bed at any inn in the country while poor people sleep on straw or worse? And have you considered, Father, that if you marry me off to some foreign prince, my sons might one day seek to take the throne of Dresnia?’

Beverak felt himself blanch. This was, indeed, the very thing he feared when it came to foreign alliances. The dagger of Dresnia was long lost and his mother had intimated that the Dark Spirit was back. Her words of two decades ago rose to mind as clearly as if she’d only just now spoken them: there will be illness, famine and war within and without the kingdoms…

‘Are you threatening me, daughter?’

‘No, Father, just stating a simple fact. Until Linvar has sons enough to ensure the succession, it might not be prudent to have nephews on foreign soil.’

Beverak stared at his daughter. Suddenly, she seemed years older. Indeed, she was old enough to know what she wanted. And should he ever decide that it was politic for her to marry, dispensations from vows were not hard to buy…

‘Have you mentioned this idea to your mother, Lyrien?’

‘I have, Father, and she has no objection as long as you give consent. She said she would rather have me close by in Rannerven than over the seas and far away.’

Her father sighed. ‘Very well, daughter, I will consider your request. Now be off with you and leave me to my work.’Lyrien closed her father’s door behind her and leaned against it, breathing a sigh of relief. It might take another talk or two, but she’d already won. Lady be thanked, she would never have to lie with a man again.

Published on August 28, 2018 21:12

The Cloak of Challiver, Chapter 3

So here we go with chapter three. Comments welcome.

Chapter 3* * *

Artwork by Marieke Ormsby‘Good Girl, Vanrel,’ said Ven Istrovar, rolling up the scroll they had been studying. ‘Now, before you go, see if you can remember the names and attributes — in order, mind — of the Sky Wanderers.’

Artwork by Marieke Ormsby‘Good Girl, Vanrel,’ said Ven Istrovar, rolling up the scroll they had been studying. ‘Now, before you go, see if you can remember the names and attributes — in order, mind — of the Sky Wanderers.’Vanrel rested her elbows on the edge of Ven Istrovar’s huge desk, closed her eyes and counted on her fingers. ‘Mirthrev, the Messenger; Vernstrith, the Beautiful; Mordestan, the Warrior; Javnor, the Beneficent; Styrak, the Limiter…’ She screwed up her eyes in concentration.

‘And what about the two guardians of the Lady’s journeying?’

‘Kedris, the Guide, and Kurdilis, the Challenger.’ Vanrel opened her eyes and smiled in delight. ‘I got them all, didn’t I?’

‘You did indeed, child. If your mother can spare you, you can come back later and read a little on your own. You can start learning the characteristics of persons born under each of the Wanderers.’

‘Thank you Ven Istrovar.’ She started for the door then turned back hesitantly. ‘There is something I don’t quite understand, sir. May I ask a question?’

‘Of course, child, but make it quick. His majesty often sends for me about this time.’

‘Are the Wanderers and Guardians really gods, or are they more like angels? Is it right to pray to them?’

Ven Istrovar sighed and put aside the scroll. ‘That’s a question, Vanrel, that sages and theologians argue over. You know they are sometimes called the Seven Lesser Gods, and that’s the way most people think of them. Some find them more approachable than the Lord and Lady, and certainly prayers to one’s own ruler, based on one’s hour of birth, are often efficacious. So perhaps regarding them as minor deities is quite acceptable. On the other hand——’

Vanrel was not to hear the other side of the argument that day, for at that moment the Venerable Tandrian, the chamberlain, put his head in the door, requesting Ven Istrovar’s immediate attendance on the king. The portly chaplain heaved himself to his feet, hastily collected a set of scrolls from the shelf above his desk and bustled off to the king’s tower, leaving Vanrel to turn over the argument for the existence of minor gods in her mind as she made her way back towards the quarters she shared with her parents above the mews.

She took a detour, however, deciding to stroll through the kitchen gardens. Other people’s work often looked much more interesting than her own. Not that she minded the prospect of being a fletcher, but there were so many other things to learn about, too. How lucky she was that Princess Lyrien had persuaded the king that the castle children ought to be taught their letters! The scrolls she studied with Ven Istrovar had opened up a whole new world.

She smiled as she thought of Princess Lyrien and her kindness, and of her brother, Prince Linvar. Many a time, they had both romped with the artisans’ children in the fields around the castle and on the sandy shore that lay below it on the seaward side. Even now Princess Lyrien would read stories to the younger children, and sometimes she would hand Vanrel the book and ask her to read for a while.

On impulse, Vanrel took another detour, this time through a corridor of ancient rosemary bushes towards that same arbour where Princess Lyrien would sit to read. She had not gone far, however, when she was pulled up by shouting from behind. Turning, she was almost bowled over by her younger brother Vedran, leading a tribe of noisy children. Only a year or two earlier she would have been running with them, barefoot and wild, answering to no one unless her parents caught her and gave her errands to run. Now and then, of course, Ven Tandrian, the chamberlain, would admonish the young vagabonds, and they had all learnt early to dodge his heavy hand.

Nowadays, Vanrel was more sedate. After all, she was fifteen, wasn’t she? Another couple of years and she’d be well and truly marriageable. Not that she wanted to marry — it seemed to Vanrel that women had the lesser portion when it came to marriage — but what else could she do? She could work as a fletcher under her father, of course, and if she married a fletcher, as her father hoped she would, her labour would be valued, but unwed, she was unlikely to be given respectable employment in her own right. Apart from household service, usually for a relative and unpaid, only two paths in life were open to unmarried women: harlot and nun. Vanrel did not want to be either.

‘Where’re you off to, Sis?’ Vedran demanded, letting the younger children run ahead. ‘Father was looking for you earlier.’

‘I was studying with Ven Istrovar.’

‘What are you, some kind of teacher’s pet?’ Vedran scoffed. ‘You’re too old for schooling. I wish I was. I’ve already got more than enough learning for folk of our kind.’

‘Ven Istrovar is giving me private tuition in Geography and Astrology. He says I’m too clever for a girl and it’s a pity I’m not a boy, then I could be a clerk.’

‘As if that’ll help you fletch arrows and feed babies! Girls can’t be clerks, everyone knows that.’

‘So what? I like having lessons with Ven Istrovar. Listen, I know the names of all the Wanderers and Guardians.’ And counting on her fingers as she had for her teacher, Vanrel again rattled off the seven names.

‘Everyone knows those. They’re just the days of the week, only a bit different.’

‘They’re more than ‘a bit different’. They’re in a different order, for a start, and besides, I have to learn all about the qualities of people born under each Wanderer.’

‘I’d rather listen to stories than read them. Or play hide and seek in the herb garden.’ And indeed, the younger children were already chasing one another around the circular paths that surrounded a little arbour, the one where Princess Lyrien sometimes read to them. Throughout the spring it had been a scented hideaway as the herbs, one after the other, came into their season of bloom. Lavender had come in early this year. Its purple spikes rose proudly above the low-growing plants that bordered the plots, so there were plenty of hiding places. The children would be safe, Vanrel knew, unless Ven Tandrian caught them and sent them packing.

She rounded a corner to find the children crowding around Princess Lyrien, who was laughing. ‘I came out for a quiet read in the garden and find I have to tell a story instead. Which one do you want to hear?’ The princess had set her book aside and was leaning forward. The children shuffled and shoved for places at her feet.

‘Tell us the one about the Siege of Sarutha, your highness,’ demanded one ragamuffin lad.

‘Please, your highness, tell us the one about how Lord Melkavar tamed the Divine Eagle,’ a small girl pleaded.

‘I know what story I’ll tell you!’ Princess Lyrien said. ‘Would you like to hear how the Three Kingdoms came into being?’

‘Are there any battles in it?’ Vedran asked.

‘Oh, yes indeed,’ replied the princess. ‘There was a mighty battle when the three kings united to drive away the wicked elvishman, Fiersten, and their equally wicked cousin, Prince Nidvar.’

‘Once upon a time,’ she began, ‘the kingdoms of Dresnia, Challiver and Syland were one, and a blessed land it was, until there came to the throne a king whose three sons squabbled bitterly over the inheritance. The boys were of an age, born at one birthing, and who could tell which came first? They were as alike as acorns on a branch or eggs in a nest. The queen did not know, or if she knew she would not tell, and the midwife swore that she had marked the firstborn with a raddle, but could not find the mark again when her work was done and all the babes were safely in their cradles. Indeed, she had to find two extra cradles, since who might have suspected that the queen would have triplets?

‘As the young princes grew, they became as alike in their rivalry as in their appearances. Their suspicion and jealousy of each other even led to open fighting. One was a master with the lance, and he could always best his brothers at jousting. The king ordered the heralds to make sure the lances he used were blunt, so that the other princes’ armour would not be pierced.

‘Another was the finest swordsman in the kingdom, and when he took part in tournaments the king would not allow the other two princes to compete, lest they be slain by their sibling.’

‘Did he kill anybody, madam?’

‘They say he killed a great giant once, but that’s another story.’

‘Tell us that tale, your highness!’

‘Maybe tomorrow. Let’s finish this one today. Which prince were we up to?’‘The third, madam!’ chorused the children.

‘Ah, yes. The third prince was a fine bowman, and the king had to confiscate his weapon more than once, fearing he would lie in ambush for his brothers.’

‘My eldest brother is a bowman,’ reported one little girl importantly. ‘He went all the way to Kyrisia to join their army.’

‘Yes, lots of our people join the army in Kyrisia,’ responded Lyrien. ‘Prince Ruthvard was a military surgeon there when he was a young man. But let’s get back to the story. The king and queen were so distressed by their sons’ constant quarrels that in the end, the king divided his land in three, and at his death, each son was to take one part. To the north lay lovely Challiver, land of plains and mountains, and in the south lay Dresnia, full of barley fields and bees. And over the sea from both of them, by just a few hours’ sailing, lay wet and windy Syland with its rivers, lakes and trees. The old king ensured there was a fine castle in each thirding, so that all three sons would have equal rank and dignity. He found for each of them a good and beautiful wife of noble birth, and he died believing that the Three Kingdoms would flourish.’

‘What did he die of?’ demanded Vedran.

‘A nasty wasting disease. He was only forty-four.’

‘My grandfather died last year,’ said another child. ‘Ven Istrovar says he’s gone to live in heaven with the Lord and Lady.’

‘My father says that’s rubbish,’ responded Vedran. ‘There’s no such place as heaven, is there, your highness?’

Princess Lyrien smiled at the boy. ‘Maybe there is. It would be nice to think of people living on in a happier place, wouldn’t it?’

‘What about the three princes?’ Someone at the back was obviously impatient for the story to continue.

‘Well,’ Lyrien went on, ‘they would have continued to fight, but their mother, Queen Ellyria, came of elvish stock, and she made for each of her sons a magic talisman. To Volran, King of Challiver, she gave a cloak of her own weaving. “As long as your descendants wear this cloak,” she told him, “Peace will prevail in your land.”