B.K. Duncan's Blog

July 2, 2016

BK Duncan on writing Foul Trade

June 24, 2016

THE PEOPLE’S BOOK PRIZE

June 12, 2016

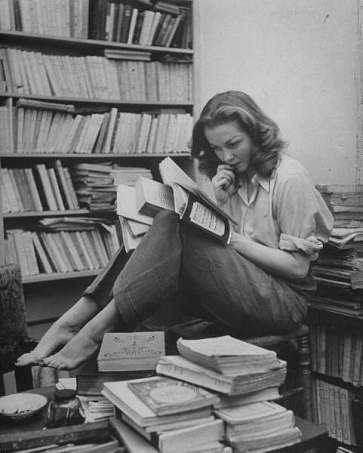

I READ, THEREFORE I AM

But spending time living vicariously is accompanied by being unable to avoid illuminating aspects of your true, deep personality. Sometimes discovering things that are startling or unsettling; things that rock the real world you inhabit and send tremors through the person you will be tomorrow. Shakespeare knew a thing or two about writing, and when he had Hamlet say of acting: ‘. . . the purpose of playing, whose end, both at the first and now, was and is, to hold, as t’were a mirror up to nature . . .’ he could have been giving his job description as a playwright.

I write because, by doing so, I learn.

My novels are set during the 1920s in the immediate aftermath of the Great War. The ongoing Centenary Commemorations have augmented my research with television programmes, radio dramas, and numerous websites where a click will unveil vivid first-hand accounts. All have enriched my understanding of self as I try to walk in the shoes of the people who endured the horrors of a worst nightmare. How would it have affected me? Surviving it would certainly have damaged me physically, psychologically or emotionally. What must it have been like to face a future that had been irrevocably altered by a cataclysmic event, the ramifications of which we, with rolling news and frontline reportage, can’t possibly comprehend? Can you imagine coming back from the trenches to a Britain flooded with a sort of collective amnesia that turned a blind eye to deny on-going suffering? Bear in mind that Wilfred Owen wrote his poems of remembrance, not for us, but to awaken his contemporaries. He bore witness to the world around him and, in doing so, left a legacy that shapes our world today.

I write because I read.

I have something to write about because others have broadened my knowledge through the written word. The number of sails on a ship running the trade winds from China? I’ll find it in a book. What woods and spices came through West India Docks and what time of year could they be expected to arrive? The labels on the exhibits in the cabinets at the London Museum Docklands told me that. How much food could a 1920 East End family buy per week and what would it cost? A contemporary newspaper article cross-referenced with the tables at the back of a volume of The New Survey of London Life and Labour put me straight. Whittaker’s Almanac of 1919 is stuffed-full of facts such as the number of postal deliveries a day (four); and the names of the police commissioners, judges, coroners, Home Office pathologists and everyone else with professional relevance to the world I was attempting to recreate. Do you care that a two-wheel horse drawn Hackney Carriage cost 2/6 (12p) to hire in 1920? You would if you were wondering if one of the characters in your story could afford to take one as a means of escape. My point in subjecting you to the sources of all this useless information is that it is only useless if you don’t need it, and if you need it, the only way to cure your ignorance is by reading.

I write because you read.

If I didn’t know you were reading this, then I wouldn’t be spending my Sunday writing it. Writing and reading is to give and to receive. Writing something down is to preserve experience and grant knowledge. Reading is to acquire and assimilate that knowledge; to learn and grow as a consequence. If we can’t read then the worlds open to us are limited and unvaried. If the person we become is a product of the combination of our inner and outer worlds, then by being unable to read we are, by definition, restricting our potential. There are too many people in England today who can only read sufficiently well to get by. The National Literacy Trust gives the figure of 16% or 5.2 million adults classed ‘functionally illiterate’ meaning they would not pass an English GCSE, and have the literacy levels at or below those expected of an 11-year-old. Such an appalling statistic in 2016 matters. It matters because if you can’t read proficiently enough to enjoy it, then you’re only ever going to read what you need to know (remember my 1920 cab fares above?) and miss out on everything else. It matters, because so much of the everyday experience of ordinary people of the past was lost when they couldn’t write down their thoughts and feelings in letters or diaries. Nor, I suspect, will any of our 5.2 million, however unique or fascinating their lives. It matters because one of the fundamental things human beings do is communicate with each other. No reading equals no texts, emails, blogs, books, magazines, newspapers, Wikipedia . . . And as a result our individual and collective world-pictures are painted in less bright colours.

So I read to write, and I write to be read. I write to be who I am. To make myself into the person I want to be. To make a difference (no matter if only in causing you think twice about Wilfred Owen) to who you are. Oh, I nearly forgot. Where does a writer get their ideas? From opening their eyes to the world around them because every story there has ever been in the history of human thought and deed is out there, writ large. You just need to be able to read the signs.

As a finalist in The People's Book Prize, BK Duncan is shortly to commence working in the community, schools and prisons, as an ambassador for The People’s Book Prize in pursuit of the organisation’s constitutional aim of eradicating illiteracy.

If you’d like her book, Foul Trade to win the fiction category of the Book Prize then you can vote until 10th July at:

www.peoplesbookprize.com/finalist.php

I READ, THEREFORE I AM

One of the most common questions an author is asked is why they write. It is second only to: Where do you get your ideas from? (I’ll come on to that one later). My answer is as simple as it is all-encompassing. I write because it opens up new worlds to me. Worlds that I only half understood before I began to explore them, or worlds I didn’t even know existed before research laid them at my feet. Worlds in which I am able to taste something of other people’s lives through memories bequeathed us; where I can – for a brief moment at least – imagine what life might be like if I hadn’t been born in the time and place I was. If I wasn’t me. And that sets you free. Free to pretend to be someone else; free to dance to the beat of a different drum. Free to escape the ordinariness of everyday life and forget the worries and stresses of the moment.

But spending time living vicariously is accompanied by being unable to avoid illuminating aspects of your true, deep personality. Sometimes discovering things that are startling or unsettling; things that rock the real world you inhabit and send tremors through the person you will be tomorrow. Shakespeare knew a thing or two about writing, and when he had Hamlet say of acting: ‘. . . the purpose of playing, whose end, both at the first and now, was and is, to hold, as t’were a mirror up to nature . . .’ he could have been giving his job description as a playwright.

I write because, by doing so, I learn.

My novels are set during the 1920s in the immediate aftermath of the Great War. The ongoing Centenary Commemorations have augmented my research with television programmes, radio dramas, and numerous websites where a click will unveil vivid first-hand accounts. All have enriched my understanding of self as I try to walk in the shoes of the people who endured the horrors of a worst nightmare. How would it have affected me? Surviving it would certainly have damaged me physically, psychologically or emotionally. What must it have been like to face a future that had been irrevocably altered by a cataclysmic event, the ramifications of which we, with rolling news and frontline reportage, can’t possibly comprehend? Can you imagine coming back from the trenches to a Britain flooded with a sort of collective amnesia that turned a blind eye to deny on-going suffering? Bear in mind that Wilfred Owen wrote his poems of remembrance, not for us, but to awaken his contemporaries. He bore witness to the world around him and, in doing so, left a legacy that shapes our world today.

I write because I read.

I have something to write about because others have broadened my knowledge through the written word. The number of sails on a ship running the trade winds from China? I’ll find it in a book. What woods and spices came through West India Docks and what time of year could they be expected to arrive? The labels on the exhibits in the cabinets at the London Museum Docklands told me that. How much food could a 1920 East End family buy per week and what would it cost? A contemporary newspaper article cross-referenced with the tables at the back of a volume of The New Survey of London Life and Labour put me straight. Whittaker’s Almanac of 1919 is stuffed-full of facts such as the number of postal deliveries a day (four); and the names of the police commissioners, judges, coroners, Home Office pathologists and everyone else with professional relevance to the world I was attempting to recreate. Do you care that a two-wheel horse drawn Hackney Carriage cost 2/6 (12p) to hire in 1920? You would if you were wondering if one of the characters in your story could afford to take one as a means of escape. My point in subjecting you to the sources of all this useless information is that it is only useless if you don’t need it, and if you need it, the only way to cure your ignorance is by reading.

I write because you read.

If I didn’t know you were reading this, then I wouldn’t be spending my Sunday writing it. Writing and reading is to give and to receive. Writing something down is to preserve experience and grant knowledge. Reading is to acquire and assimilate that knowledge; to learn and grow as a consequence. If we can’t read then the worlds open to us are limited and unvaried. If the person we become is a product of the combination of our inner and outer worlds, then by being unable to read we are, by definition, restricting our potential. There are too many people in England today who can only read sufficiently well to get by. The National Literacy Trust gives the figure of 16% or 5.2 million adults classed ‘functionally illiterate’ meaning they would not pass an English GCSE, and have the literacy levels at or below those expected of an 11-year-old. Such an appalling statistic in 2016 matters. It matters because if you can’t read proficiently enough to enjoy it, then you’re only ever going to read what you need to know (remember my 1920 cab fares above?) and miss out on everything else. It matters, because so much of the everyday experience of ordinary people of the past was lost when they couldn’t write down their thoughts and feelings in letters or diaries. Nor, I suspect, will any of our 5.2 million, however unique or fascinating their lives. It matters because one of the fundamental things human beings do is communicate with each other. No reading equals no texts, emails, blogs, books, magazines, newspapers, Wikipedia . . . And as a result our individual and collective world-pictures are painted in less bright colours.

So I read to write, and I write to be read. I write to be who I am. To make myself into the person I want to be. To make a difference (no matter if only in causing you think twice about Wilfred Owen) to who you are. Oh, I nearly forgot. Where does a writer get their ideas? From opening their eyes to the world around them because every story there has ever been in the history of human thought and deed is out there, writ large. You just need to be able to read the signs.

Bk Duncan is shortly to commence working in the community, schools and prisons, as an ambassador for The People’s Book Prize in pursuit of the organisation’s constitutional aim of eradicating illiteracy.

If you’d like her book, Foul Trade to win the fiction category in the final of the 2016 Book Prize awards then you can vote until 10th July at:

April 5, 2016

DIARY OF A DEBUT AUTHOR

It feels strange to have the label of debut author after 20 years spent being a full-time writer, but I guess what it really signifies is that I have, at long last, come to the end of my apprenticeship. But one of the new kids on the block I must be because I find myself a finalist in the 2016 Beryl Bainbridge First Time Author Award. And with that honour in the offing, I don’t mind what I’m called.

I keep a writing journal periodically – usually during the blood, sweat, and tears of a novel that refuses to play nicely – in the belief we recreate patterns and that much of learning is about revisiting the turning points to forestall making the same mistakes the next time around. There is a diary equally close to my heart as when I discovered it in the Museum of London Docklands’ collection I finally felt I had an authentic insight into the world of my historical crime novel, Foul Trade. Oscar Kirk was a 15 year-old messenger boy who left for us the everyday details of his life in 1919. In gratitude, I dedicated the book to his memory.

I thought it might be fun in a ‘compare and contrast’ sort of a way to share some of his entries with you alongside a few authorial reflections during my own quest for a place (albeit a minor one) in history. So, here goes . . .

DIARY ENTRY 1

Oscar Kirk Sunday 9th February 1919

Father went to Beard’s in Stepney to get a couple of pairs of shirts. He came home with some lovely ones.

Had mutton for dinner & had a second helping. Mother gave me half of the chocolate which Nana made last night, and an orange. Had some bacon and fried bread for breakfast.

BK Duncan Sunday 13th March 2016

Made a vat-load of pea & ham soup, which is going to be my stable diet for the foreseeable future as the Awards Ceremony is going to be televised and the only posh frock I possess is a snug fit (and that’s putting it kindly). Have also resurrected my long-abandoned regime of daily gym visits – it’s amazing what a motivator vanity can be.

Talking of mass exposure, I still can’t decide whether to take up one of my creative writing student’s offer of making a short programme for Cambridge TV. I know I should (because the public can’t vote for me if they don’t know I exist and to win The People’s Book Prize I have to come top of the polls) but I’m numbed with terror at the prospect. I’ve been live on local radio and discovered I really enjoyed the experience, but it’s the visual nature of the thing that worries me – will my fear come across and I look like a rabbit in the headlights? And what about my hands? Could I end up resembling a manic axe murderer if I wave them around as much as I normally do; conversely, would sitting on them render me as lifeless as a shop mannequin? On radio I could force relaxation into my voice by pretending I wasn’t sitting in a studio behind a barrage of microphones and computers, although I suspect my resulting intermittent zoning-out was a tad alarming for the interviewer (except she did invite me back so I couldn’t have appeared too deranged).

Vanity, vanity, all is vanity: I do know that. But being a writer is about ego – believing I have something to say you would want to spend your time reading – and, as a novice novelist (as opposed to a seasoned writer), it’s tricky to find the balance between self-belief and self obsession. A wise crime writer friend recently gave me some advice on the matter:

‘Think of your ego like a sports car . . . sometimes in the garage, sometimes tootling along country lanes, sometimes roaring full throttle along the highway . . .’

Think I’ll print that out and stick it above my computer.

On a purring engine note, I am the featured local author sharing favourite reads in this month’s Hertfordshire Life magazine. Pleased with my choices: Delight by the always entertaining and wonderfully opinionated J.B. Priestly; The Silent Boy by the very, very nice man (and what a great writer!) Andrew Taylor; and Longbow by Robert Hardy.

Soon time to think about how to tackle the rewrite of the second book in the May Keaps series, Found Drowned. Ah, that is what I enjoy and what I signed-up for. I always tell my students that the real work of being a writer is in the rewriting; when you can use your skills to craft the book into being the best it can possibly be. I liken it to a master carpenter whittling away the excess wood and knots until you can see the beauty of the grain beneath and can commence polishing.

Which reminds me, need to get another coat of beeswax on my new arrows. So love the fletchings which are blue barred with black like a jay’s feathers. Only hope I can complete the imitation by making them fly through the trees in the forest on Saturday.

Polls open to vote for BK Duncan and Foul Trade on 16th May. You can register to be eligible now at The People’s Book Prize

July 13, 2015

The People’s Book Prize

I’m delighted to be able to say that Foul Trade has been nominated for an award voted for exclusively by the public.

The People’s Book Prize was set up by Dame Beryl Bainbridge DBE (current Patron Frederick Forsyth CBE) with the aim of supporting and promoting new and undiscovered literary works, raising the profile of libraries, and celebrating reading in general. With such great ideals at its heart I am proud and honoured to have my crime novel up there on the short-list.

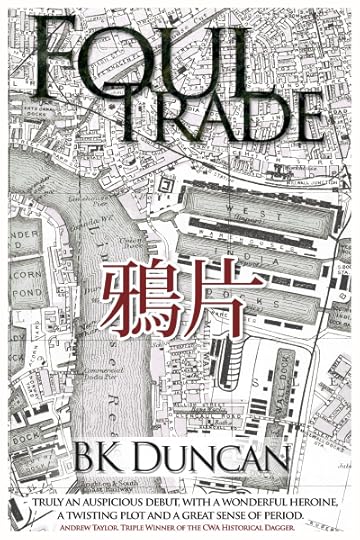

Andrew Taylor (triple winner of the CWA Historical Dagger, Diamond Dagger recipient, and recently hailed by the London Times as the most consummate writer of historical fiction today) had this to say about Foul Trade:

” I thought it was meticulously researched, with a fascinating and unusual setting and a strong protagonist. It richly deserves The People’s Book Prize — you just have to read it to see why!”

Voting closes for Foul Trade on 31st August 2015. You can cast your vote for me here:

http://www.peoplesbookprize.com/section.php?id=6

With so much else for people to spend their time on in the world it is always a joy for an author to know someone has appreciated their writing, the cover they designed (as I did using a 1920 map), or purely wants to champion someone for whom success is now blossoming on the back of crafting novels for over 20 years.

To read and write, to be able to share my heart and imagination with others; these are privileges I was given as a young child when I first discovered books. My aim in life is to be able to pass that on.

I’m currently working on the second book in the series, Found Drowned, but will, of course, put down my pen long enough to let you know if I win!

Best wishes

BK Duncan

TO SIGN UP FOR MY NEWSLETTER, CLICK ON THE RED POSTBOX.

July 7, 2015

The People's Book Prize

I'm delighted to be able to say that Foul Trade has been nominated for an award voted for exclusively by the public.

The People's Book Prize was set up by Dame Beryl Bainbridge DBE (current Patron Frederick Forsyth CBE) with the aim of supporting and promoting new and undiscovered literary works, raising the profile of libraries, and celebrating reading in general. With such great ideals at its heart I am proud and honoured to have my crime novel up there on the short-list.

Andrew Taylor (triple winner of the CWA Historical Dagger, Diamond Dagger recipient, and recently hailed by the London Times as the most consummate writer of historical fiction today) had this to say about Foul Trade:

" I thought it was meticulously researched, with a fascinating and unusual setting and a strong protagonist. It richly deserves The People's Book Prize -- you just have to read it to see why!"

Voting closes for Foul Trade on 31st August 2015. You can cast your vote for me here:

http://www.peoplesbookprize.com/secti...

With so much else for people to spend their time on in the world it is always a joy for an author to know someone has appreciated their writing, the cover they designed (as I did using a 1920 map), or purely wants to champion someone for whom success is now blossoming on the back of crafting novels for over 20 years.

To read and write, to be able to share my heart and imagination with others; these are privileges I was given as a young child when I first discovered books. My aim in life is to be able to pass that on.

I'm currently working on the second book in the series, Found Drowned, but will, of course, put down my pen long enough to let you know if I win!

Best wishes

BK Duncan

August 13, 2014

It Wasn’t All Downton Abbey

Audley End (Richard Marsham)

Audley End (Richard Marsham)History as nostalgic entertainment will always be with us. We appear to have an insatiable appetite for it. But history grounded in the lives of the people who knew what it was really like isn’t the stuff of high-rating television shows. It is too ordinary; sometimes too tragic or depressing; and always too riddled with inconsistencies. We want glamour – fancy frocks and Stately Homes, pristine uniforms and pretty faces; we long for complicated love stories instead of marriage as an economic and social necessity; we need the structure of hierarchy to turn our eyes away from current chaos – epitomised in cheerful servants, benevolent landowners, duty, moral strictures, and purpose.

A rosy glow of the past smooths out lumps and bumps and gives us the luxury of an overview that the people involved never had. Do you know what your life will be like in five year’s time? Next week, even? How can any of us know that headlines about the banking crisis, Ukraine, Gaza or Iraq might hint that the world is about to change forever? It serves us well to remember that we are living the history of tomorrow.

History changes things from what might have been, to what is. The First World War directly affected my grandparents, had consequences for my parents, and shaped the society in which I live. And, however young you are, 100 years on, the conflict will cast its shadow over you as well. History never goes away. Every second that ticks away simply adds another layer that will, in turn, alter how we perceive what went before. To quote the Director of the British Museum:

If you think carefully about the past, you will be able to think differently about the present.

So, as a historical crime writer, how do I transport myself back in time to get under the romance of interpretation? How do I resist falling back on carefree stereotypes dancing through time gleaned from films, television, and fanciful stories? By seeking out the words of those who were there. By reading and absorbing the letters, diaries, memoirs, and oral history accounts passed down through generations. Because in them is the proof that the long gone had the same hopes, dreams, fears, preoccupations and troubles that you or I might have. It is the experience of their lives as they lived them on which I base my fiction, and that I endeavour to honour.

The research for Foul Trade really came alive when I discovered Oscar Kirk’s 1919 diary in a London Museum Docklands’ collection. He was a 15 year-old messenger working in the West and East India Docks. Oscar wrote down the sort of things every boy would find noteworthy – divers salvaging in Limehouse Basin; a chemical works’ fire; watching a Charlie Chaplin film; letting off a cordite cartridge he’d bought; being chased out of the sack sheds by a policeman. But he also included remarkably touching details of his ordinary life:

Tuesday 4 February 1919

Went to the library and changed my library book and also Nanas [sic] (“Strand” for me and “Eternal Love” for Nana). Bought two halfpenny buns as I was coming home from the library.

Wednesday 5 February 1919

Had some fish for supper (cod). Read some of my library tonight. Had some chestnuts today out of the SS Rhio. I found the chestnuts on the quay but I didn’t think that I could be charged with stealing them as I found them. Had some soup for dinner (at 5pm).

Saturday 8 February 1919

It is my half-day today. Went to London Bridge in the afternoon on an omnibus . . . I think that I have lost sixpence out of my pocket but Mother made it up for me. I bought “Gem” and a ginger cake. Nana came this evening and made some chocolate which turned out to be somewhat of a failure.

This young man lived what I wanted to write about, and through his diary allowed me a glimpse of his world. In gratitude I’ve dedicated Foul Trade to the memory of Oscar Kirk.

You can find out more about Foul Trade, the first book in a historical crime series, at Amazon and by visiting my website: bkduncan.com Pinterest boards and Goodreads

It Wasn't All Downton Abbey

A rosy glow of the past smooths out lumps and bumps and gives us the luxury of an overview that the people involved never had. Do you know what your life will be like in five year’s time? Next week, even? How can any of us know that headlines about the banking crisis, Ukraine, Gaza or Iraq might hint that the world is about to change forever? It serves us well to remember that we are living the history of tomorrow.

History changes things from what might have been, to what is. The First World War directly affected my grandparents, had consequences for my parents, and shaped the society in which I live. And, however young you are, 100 years on, the conflict will cast its shadow over you as well. History never goes away. Every second that ticks away simply adds another layer that will, in turn, alter how we perceive what went before. To quote the Director of the British Museum:

If you think carefully about the past, you will be able to think differently about the present.

So, as a historical crime writer, how do I transport myself back in time to get under the romance of interpretation? How do I resist falling back on carefree stereotypes dancing through time gleaned from films, television, and fanciful stories? By seeking out the words of those who were there. By reading and absorbing the letters, diaries, memoirs, and oral history accounts passed down through generations. Because in them is the proof that the long gone had the same hopes, dreams, fears, preoccupations and troubles that you or I might have. It is the experience of their lives as they lived them on which I base my fiction, and that I endeavour to honour.

The research for Foul Trade really came alive when I discovered Oscar Kirk’s 1919 diary in a London Museum Docklands’ collection. He was a 15 year-old messenger working in the West and East India Docks. Oscar wrote down the sort of things every boy would find noteworthy – divers salvaging in Limehouse Basin; a chemical works’ fire; watching a Charlie Chaplin film; letting off a cordite cartridge he’d bought; being chased out of the sack sheds by a policeman. But he also included remarkably touching details of his ordinary life:

Tuesday 4 February 1919

Went to the library and changed my library book and also Nanas [sic] ("Strand" for me and "Eternal Love" for Nana). Bought two halfpenny buns as I was coming home from the library.

Wednesday 5 February 1919

Had some fish for supper (cod). Read some of my library tonight. Had some chestnuts today out of the SS Rhio. I found the chestnuts on the quay but I didn't think that I could be charged with stealing them as I found them. Had some soup for dinner (at 5pm).

Saturday 8 February 1919

It is my half-day today. Went to London Bridge in the afternoon on an omnibus . . . I think that I have lost sixpence out of my pocket but Mother made it up for me. I bought "Gem" and a ginger cake. Nana came this evening and made some chocolate which turned out to be somewhat of a failure.

This young man lived what I wanted to write about, and through his diary allowed me a glimpse of his world. In gratitude I’ve dedicated Foul Trade to the memory of Oscar Kirk.

You can find out more about Foul Trade, the first book in a historical crime series, by visiting my website: www.bkduncan.com

May 28, 2014

2014 Commemoration of start of WW1

I have recently finished a short story, Faith's Reward, as a prequel to my novel Foul Trade. It covers one of the harrowing days in the life of May Keaps when she was an ambulance driver in Northern France. And I dedicate it to every woman who endured such experiences for real. Mine is a work of fiction, but their losses and deprivations weren't brought to a conclusion with the closing of a book. Some things live on in the memory forever.

If you'd like to find out more about my research sources then please visit my website: http://www.bkduncan.com