Peri Hoskins's Blog

September 2, 2018

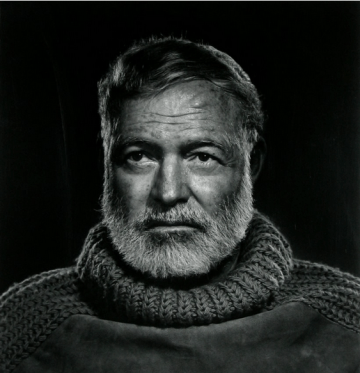

Ernest Hemingway’s The Sun Also Rises

I have just re-read Ernest Hemingway’s The Sun Also Rises. I first read this novel in 1982. It was my first year of university. The book was part of my twentieth century literature course. I loved the book then. It introduced me to Hemingway’s spare and masculine prose. He wasted no words. And for me, like Hemingway, less was more. I also much enjoyed the second reading. In particular I liked the photographs and background information within the Hemingway Library edition. Those were not available to me in the standard edition back in 1982.

I have just re-read Ernest Hemingway’s The Sun Also Rises. I first read this novel in 1982. It was my first year of university. The book was part of my twentieth century literature course. I loved the book then. It introduced me to Hemingway’s spare and masculine prose. He wasted no words. And for me, like Hemingway, less was more. I also much enjoyed the second reading. In particular I liked the photographs and background information within the Hemingway Library edition. Those were not available to me in the standard edition back in 1982.

Real People and Events

Hemingway based the novel on real events including the annual bullfights and festival he attended in Pamplona, Spain. He also based his fictional characters on real people: himself and his friends. He was Jake Barnes, Lady Duff Twysden was Lady Brett Ashley and Harold Loeb was Robert Cohn. Unsurprisingly, the real people were less than happy with their characters. Twysden pointed out she never slept with a bullfighter. Loeb maintained Hemingway portrayed his character in a poor light out of jealousy: Loeb had slept with Twysden and Hemingway had not.

Political Correctness

On my first reading back in 1982, I liked the powerful and lean prose. Those were the days before political correctness. In 1982 I did not consider whether or not the content was politically correct. Having just read the novel for the second time I am left wondering whether in 2018 a mainstream publisher would accept it. If Hemingway was launching his first novel today would he be joining the growing ranks of self-published authors? In 2018 the novel clearly fails the political correctness test. There are two obvious failures. First, the characters display anti semitic attitudes including Hemingway’s alter ego, Jake Barnes. No apology is made for those attitudes. Secondly, Africans are referred to as niggers, and exist only as caricatures.

Racism

RacismWithin the book’s opening paragraph we learn that Robert Cohn, a Jew and former middleweight boxing champion of Princeton, had his nose permanently flattened by another Princeton boxer. This ‘increased Cohn’s distaste for boxing, but it gave him a certain satisfaction of some strange sort, and it certainly improved his nose.‘

As the novel unfolds Cohn is described by Jake Barnes and friends as ‘superior and Jewish‘, ‘that kike‘ and ‘that damned Jew.’ While racial stereotyping is evident in Hemingway’s description of Robert Cohn, including a Jewish nose (albeit flattened), a Jewish superior attitude, and ‘a hard, Jewish, stubborn streak’, Hemingway gives Cohn redeeming features. He describes him as ‘shy‘ and having a ‘nice boyish sort of cheerfulness that had never been trained out of him.‘ He has an ingenuous quality. Cohn is the smitten romantic who having read and reread W H Hudson’s ‘The Purple Land‘ about the ‘amorous adventures of a perfect English gentleman in an intensely romantic land‘ will do battle for his lady love, Lady Brett Ashley. Consequently Cohn, being a central character, comes across as well-rounded and not just a racial stereotype.

Central and Minor Characters

The novel’s other central characters are American or European. They also come across as well-rounded real people. There are no African central characters, however passing reference is made to Africans. Inside a Montmartre bar ‘the nigger drummer waved at Brett.’ Jake Barnes describes him as ‘all teeth and lips‘. Early within book two Jake’s friend Bill Gorton tells Jake about a ‘wonderful nigger‘ prize fighter, and that ‘he’d loaned the nigger some clothes …’. Jake asks Bill ‘what became of the nigger?‘ While the Africans in the book are not fully developed characters, to the extent they are there, they exist as caricatures. The European minor characters are almost all Spanish and French. They receive mainly favourable treatment and do not appear as caricatures. Hemingway treats the German maitre d’hotel harshly, including his German accent. This may be more evidence of racism. However, it is arguable the man’s race is incidental to Hemingway’s disparaging treatment of an individual character he disliked.

The Sun Also Rises was first published in 1926. It was Ernest Hemingway’s first novel. Hemingway’s treatment of Jews and Africans within the book is disparaging. No doubt it reflects the prevalent attitudes of the time. The publication of this book ushered in Hemingway’s stellar literary career, and with it his immense influence on modern prose. The Sun Also Rises has endured because it is superb literature. If Hemingway were to publish the novel today as a first novel it seems beyond belief that such a book would fail to attract a mainstream publisher because of political correctness. Political correctness should not be taken into account when assessing literary merit. If it is taken into account great literary works will not reach the reading public.

The Sun Also Rises was first published in 1926. It was Ernest Hemingway’s first novel. Hemingway’s treatment of Jews and Africans within the book is disparaging. No doubt it reflects the prevalent attitudes of the time. The publication of this book ushered in Hemingway’s stellar literary career, and with it his immense influence on modern prose. The Sun Also Rises has endured because it is superb literature. If Hemingway were to publish the novel today as a first novel it seems beyond belief that such a book would fail to attract a mainstream publisher because of political correctness. Political correctness should not be taken into account when assessing literary merit. If it is taken into account great literary works will not reach the reading public.

Send to Kindle

Send to KindleThe post Ernest Hemingway’s The Sun Also Rises appeared first on Peri Hoskins Author.

January 26, 2018

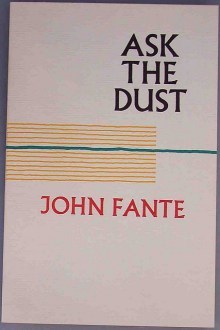

John Fante’s “Ask the Dust”: A Review

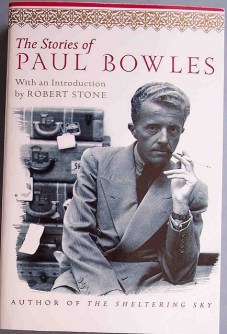

I’m fond of books that made few ripples when born into the world, but surface many years later to find fame and critical acclaim. A few years ago I came across one such novel: Paul Bowles’ A Sheltering Sky. Published in 1949, the book became a movie 51 years later in 1990, directed by Bernardo Bertolucci, and starring John Malkovich and Debra Winger. Bowles, then nearly 80, narrated the film and appeared in a cameo role. A Sheltering Sky now appears in collections of top 100 novels of the twentieth century. For Bowles, who died in 1999, I guess late success was better than none.

Last month I discovered another such gem: John Fante’s novel, Ask the Dust. First published in 1939, the book was made into a movie 67 years later in 2006 starring Colin Farrell. As Fante died in 1983, he did not see his novel adapted into a movie.

Fante’s fellow Los Angeles novelist, Charles Bukowski, provides an introduction to the 1979 edition of Ask the Dust, being the one I read. Bukowski accidentally discovered the novel as he trawled ′rows and rows of exceedingly dull books’ on the shelves of the Los Angeles public library wondering ′why didn’t anybody say something? Why didn’t anybody scream out?’ Bukowski said ‘Fante was my god’ and since the 1970’s Bukowski’s endorsement of Fante’s then out of print books has seen a resurgence in Fante’s popularity.

Having read and enjoyed Bukowski’s novels: Post Office, Factotum, Ham on Rye, and Women, I now see Fante’s influence in Bukowski’s prose. And in my novel East, I see Bukowski’s influence, and now realise Fante’s influence flowed through Bukowski’s work to also contribute to my own prose style.

Fante’s semi-autobiographical Ask the Dust was written in 1938 as war momentum built in Europe. Set in 1930′s depression-era Los Angeles, it has become known as the great Los Angeles novel. Among other things it deals with the theme of unrequited love triangles. The protagonist, young Italian American writer, Arturo Bandini, is in love with Camilla, a young Mexican waitress. Camilla is in love with Sammy, the bartender. And Sammy is in love with himself. The characters are well fleshed out. Camilla, in particular, stands out as totally real.

Fante’s semi-autobiographical Ask the Dust was written in 1938 as war momentum built in Europe. Set in 1930′s depression-era Los Angeles, it has become known as the great Los Angeles novel. Among other things it deals with the theme of unrequited love triangles. The protagonist, young Italian American writer, Arturo Bandini, is in love with Camilla, a young Mexican waitress. Camilla is in love with Sammy, the bartender. And Sammy is in love with himself. The characters are well fleshed out. Camilla, in particular, stands out as totally real.

This 165-page novel builds slowly. Not much happens during the first half. There was just enough interest to keep me turning the pages. The book begins with Arturo behind on the rent arrears for his hotel room. He solves the acute problem of the landlady’s note telling him to pay up or move out by ′turning out the lights and going to bed.′

This 165-page novel builds slowly. Not much happens during the first half. There was just enough interest to keep me turning the pages. The book begins with Arturo behind on the rent arrears for his hotel room. He solves the acute problem of the landlady’s note telling him to pay up or move out by ′turning out the lights and going to bed.′

As the story unfolds Fante develops themes within Arturo’s thought passages. At page 24, Arturo’s racial sentiments show less politically correct times:

The Mexican appeared. He stood in the fog, lit a cigaret, and yawned. Then he smiled absently, shrugged, and walked away, the fog swooping upon him. Go ahead and smile. You stinking Greaser – what have you got to smile about? You come from a bashed and busted race, and just because you went to the room with one of our white girls, you smile. Do you think you would have had a chance, had I accepted on the church steps?

Italian American Arturo has himself suffered racism. Among other things he has been called ‘wop‘ and ‘dago‘. And the racism he shows towards Mexicans, including Camilla, stems from those wounds. Fante makes this clear from Arturo’s thoughts at page 47:

Charles Bukowski

But I am poor, and my name ends with a soft vowel, and they hate me and my father, and my father’s father, and they would have my blood and put me down, but they are old now, dying in the sun and in the hot dust of the road, and I am young and full of hope and love for my country and my times, and when I say Greaser to you it is not my heart that speaks, but the quivering of an old wound, and I am ashamed of the terrible thing I have done.

The novel develops power in the second half. Camilla’s descent into mental illness and her fascination for Sammy, the one she can’t have, and the one who hurts her most, all ring true. I found myself recognising those traits in people I’ve known. Fante continues to develop the novel’s deeper themes within Arturo’s thought passages, as we see on page 96:

Bunker Hill, Arturo’s Los Angeles Home

… the world seemed a myth, a transparent plane, and all things upon it were here for only a little while, all of us, Bandini, and Hackmuth and Camilla and Vera, all of us were here for a little while, and then we were somewhere else; we were not alive at all; we approached living, but we never achieved it. We are going to die. Everybody was going to die. Even you, Arturo, even you must die.

At page 104 Fante returns to his theme of transient earthly existence: ‘The world was dust, and dust it would become.′ And again at page 120:

There came over me a terrifying sense of understanding about the meaning and the pathetic destiny of men. The desert was always there, a patient white animal, waiting for men to die, for civilisations to flicker and pass into the darkness.

I found exasperating Arturo’s inability to man-up at crucial moments and get it on with Camilla. Camilla is a hot young Mexican woman. Is  Arturo not a young hot blooded Italian man full of male hormones? But you don’t have to like the characters to get what the novel has to give. I know this, my novel, East, is peopled with unsympathetic characters, including one who is unable to stop telling of his inability to man-up in bed with women.

Arturo not a young hot blooded Italian man full of male hormones? But you don’t have to like the characters to get what the novel has to give. I know this, my novel, East, is peopled with unsympathetic characters, including one who is unable to stop telling of his inability to man-up in bed with women.

Having read this book I was reminded how novelists build on each other’s work. Bukowski built on Fante’s work by extending Fante’s ‘tell it like it is’ style to also tell it like it is in the bedroom. Bukowski, who also read Henry Miller, leaves little to the imagination in his sex scenes. Fante is honest, but shows much more reserve. Take this scene from page 94 of Ask the Dust:

And I was glad for her tears, they thrilled me and lifted me, and I possessed her. Then I slept, serenely weary, remembering vaguely through the mist of drowsiness that she was sobbing, but I didn’t care.

Bukowski portrays a racist and abusive father in his autobiographical novel, Ham on Rye, but was somewhat reserved on the subject of race. Maybe it was hard for a German American like Bukowski to say too much about race. Within East, I went further than both Bukowski and Fante on the issue of race. Being a mixed race person helped with that. And my sex scenes are more detailed than Fante’s and a little less detailed than Bukowski’s.

Bukowski portrays a racist and abusive father in his autobiographical novel, Ham on Rye, but was somewhat reserved on the subject of race. Maybe it was hard for a German American like Bukowski to say too much about race. Within East, I went further than both Bukowski and Fante on the issue of race. Being a mixed race person helped with that. And my sex scenes are more detailed than Fante’s and a little less detailed than Bukowski’s.

Among other things Ask the Dust deals with the struggle of different races to fit into America and our common human struggle to find meaning within short and apparently meaninglessness lives. I was reminded of the need to be kind to one another given the short time we are all here. For that alone the book is well worth reading. And the novel gives much more than that. The fact it is still being read and enjoyed shows Fante tapped into timeless and universal themes.

All made of dust, we all go back to dust. So where to look for answers for our short and apparently meaningless lives? Ask the dust …

Send to Kindle

Send to Kindle

The post John Fante’s “Ask the Dust”: A Review appeared first on Peri Hoskins Author.

January 10, 2017

Interview with Louise Roenn

Welcome Louise, it’s great to be interviewing you about your book of poems, I Thought We Were Just Hanging Out.

Welcome Louise, it’s great to be interviewing you about your book of poems, I Thought We Were Just Hanging Out.

Thank you, Peri. It’s a pleasure to be speaking with you about the book.

Your poems have great immediacy, emotional honesty, and seem to come from authentic raw experience. Which poets do you admire and which poets have inspired you?

I really enjoy Jodi Hill’s poems. She’s a poet from Minnesota, USA, who writes about love, being a woman, vulnerability, opening up, embracing, and letting go. I also love Pia Tafdrup, a Danish poet working with similar themes, and other Danish poets I grew up with. But to be honest, a lot of the times I’m inspired by people I meet during my travels, what they say, and writing I see in coffee shops or on Instagram. To me, poetry is everywhere – including in my own heart, when I’m quiet and listen.

You were born in Denmark and now live back there, in Aarhus. You have travelled to 60 countries. Has travel been important for your writing?

I feel very inspired when I travel, yes. I do a lot of writing on airplanes, trains, busses, even on the backseat of a car and on my iPhone. I write when it comes to me, and often when I travel, something will pop up and I’ll write it down that moment. It may end up in a book, a song or a story later. My job in that moment is to capture by writing it down.

How was travel important for this book?

‘I Thought We Were Just Hanging Out’ is a personal love story that transpired while I traveled in Australia, North America, Europe, and Africa. I wrote poems along the way, so without the travel and without the love that I felt, there would have been no poems and no book. Danish author Hans Christian Andersen wrote, ‘To travel is to live.’ I know what he means. I feel very much alive when I travel – when I move. It’s a hugely inspiring setting for me to be on the road. The editing of the book, however, was done at home in the quietness of my apartment in Aarhus, Denmark with Skype screen-sharing to my editor and graphic designer in the UK. The photographs were done in San Francisco. Traveling played a significant role in the creative process.

You’ve worked as a journalist, film producer and international event director. Has your working life shaped your writing, and if so, how?

I’ve always done a lot of writing as a child and young journalist. I had my first newspaper story published when I was twelve and by the time I finished high school, I had had over 400 stories published in the local paper and different magazines. I had my own column too for three years. When you work with film production and events, you do a lot of writing – story boards, invitations to attendees, press releases, website updates, etc. I feel that the way my work life has shaped my writing is that I write in a simple, quite direct way with a journalistic approach and an authenticity and honesty. I also write about people and places and how things feel and smell, and that is probably from all those years in the field as a journalist and around the world as a producer and director.

The poems in the book seem to come from recent raw experience – in a word: heartbreak. You’ve dedicated the book to ‘T’ ‘For breaking my heart right open.’ I’m guessing ‘T’ is the man in the relationship that inspired the book?

Yes, his name starts with a ‘T’. The book is dedicated to him.

In the first poem the relationship changes from friendship to something deeper. The second seems to deal with infatuation. The third poem speaks of your soul’s recognition upon meeting. The fourth mentions the other woman in his life (and she seems to haunt some of the poems). The fifth the longing to see him again. The sixth delights in the richness of the relationship. The seventh his departure for another country. In the eighth poem the relationship is in the past tense, he has gone back to the other woman, and there’s great sadness in that poem and the ninth poem. The final poem That Day on the Beach is more reflective, you seem to have come to terms with the loss, and there’s gratitude for what you did have together. Is that a fair assessment?

Yes, that’s a fair assessment.

There seems to be an arc in the poems from beginning to end. Do the poems tell the story of the relationship from beginning to end? And does that arc reflect something deeper about humanity and this human life?

There seems to be an arc in the poems from beginning to end. Do the poems tell the story of the relationship from beginning to end? And does that arc reflect something deeper about humanity and this human life?

I guess you could say that, yes. I wrote the poems while we were together and after we parted. I had no intention of ever publishing them. Three years went by before I was ready to do that. During my book tour in the U.S., a lot of people in the audience came up to me after a book reading, telling me how much they related to the poems in the book and the overall story. I met many who had experienced love and loss similar to mine, and the poems reminded them of that. I also met a woman who said that she had never felt anything like that, and she had been married for 25 years – now recently divorced. But I think the themes of love, longing, loss and moving on are universal and when I read my book today, it still expresses themes I’m going through – not necessarily related to ‘T’, who the book is about, but to my life in general.

Good writing, poetry or prose, reveals truths and explores universal themes. What are the truths revealed and universal themes explored in these poems?

The themes for me in the poems and in the book are: Love is possible. Life can be truly magical. Letting go and moving on is hard, but something incredibly beautiful can come from it. Everything changed for me when I realized that my heart was broken open and that the love I felt in the meeting with ‘T’ was the beginning of a much more rich life, not the end of it. I’m very grateful for the experience today, and I’ve felt first hand that we don’t always know or understand the meaning of things while they happen, but perhaps we will later on. And last, but not least: time does heal. You will love again. That is true for me today, four years after the adventure with ‘T’.

You are working on a new book. Please tell me about your new project. Is it more poetry, or is it prose? With your background as a journalist I sense a fellow prose writer?

I’m always working on a number of different projects. Which ones actually get published, turn into a book, song or a music video, I have less control over. That seems to reveal itself in the process. But one project I’m working on is a book about how I’ve traveled to 60 countries on five continents the past fourteen years, lived my dream and filled my heart with adventure. A lot of people asked me during my book tour how all this travel is possible for a 33-year-old Danish woman, who is not (yet) independently wealthy. To them, the life I live on the road, which is completely self-funded, is mysterious. To me, it’s a normal way of life. I want to give people the ins and outs of what I’ve done to live a life many people simply dream of but don’t know how to make a reality. A lot of it has to do with management of finances, priorities, choosing jobs and projects you can do on the road, etc. I like the idea of giving people tools and showing them what I’ve done in case they want to live a life full of adventure as well.

What themes does the new book explore?

How to travel the world, live your dream and fill your heart with adventure. How to manage your money in ways so you can fund your adventures and how to think creatively about how your life is spent. We don’t have to work and live like everyone else. It’s possible to do things differently. It’s possible to live the life that is right for you. Do things your way.

Thank you Louise, it’s been great interviewing you. Where may readers buy your books?

It’s been an honor to speak with you, Peri. My books and other adventures are available on www.louiseroenn.com

The post Interview with Louise Roenn appeared first on Peri Hoskins Author.

October 11, 2016

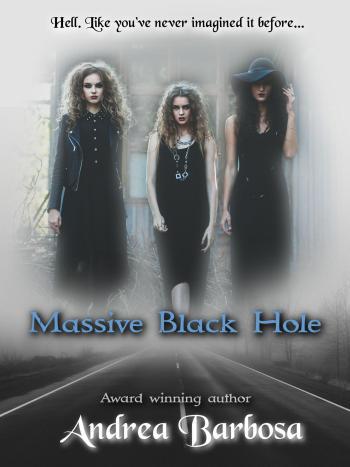

An interview with Andrea Barbosa about her novel ‘Massive Black Hole’

An Interview with Andrea Barbosa

An Interview with Andrea Barbosa

Welcome Andrea, it’s great to be interviewing you about your novel, Massive Black Hole.

Thank you for having me, it’s a pleasure.

You write both poetry and prose. Which do you prefer to write?

I find poetry easier to write as long as I find the right mood and topic. It flows and the words can be interpreted in different ways, making the reading more intriguing.

You were born in Brazil but you live in Houston, Texas?

That’s right. I’m Brazilian-born and have been living in the US.

To what extent did your own migrant experience contribute to the themes and characters within your novel?

Sometimes it’s easier to write about things that are familiar to us. My international experience definitely contributed to how the character of Cibele was developed, and details and descriptions of some of the setting and life in Brazil.

One of your characters, Cibele, is Brazilian and has strong Christian beliefs in heaven and hell.

As a teenager, Cibele’s character never really thought deeply about it until she visited the MET and became fascinated with Bosch’s painting. Because she’s Brazilian, it’s suggested that she was raised in a Christian environment where heaven and hell are a strong part of the belief system.

Do you identify with any of the characters? Is one of the characters your alter-ego? Are the characters based on real people you have met?

The characters might have a little bit of me and a little bit of people I’ve met in my life, but just snippets from some experiences with travelling and working in different environments. Their actions and motives are purely fictional.

Were you brought up as a Roman Catholic?

Yes.

To what extent does Catholicism underpin Massive Black Hole? Would you say Catholicism and Christian morality are recurrent themes within this novel?

In the sense of heaven and hell, it could be considered as a religious theme appearing throughout the novel because of the ever-present imagery of the black hole as a portal to hell and the way in which Cibele is traumatized about it. However, the novel was not intended as a religious tale. The discussion Cibele and Amy have about sin, punishment, beliefs, was purely intended as a means to achieve the sort of paranormal ending I envisioned.

Would you say Massive Black Hole is a morality tale in which sinners are punished by god? And are people who do good rewarded by god?

I suppose it could be interpreted that way by some readers, but that was not the intention. When I started writing this novel, all I had in mind was the ending: a place where you’re stuck, going around in circles, not being able to escape. The characters helped me write the story, and it kind of evolved that way. Amy’s character was not planned and only showed up into the novel during the third or fourth editing. The religious motives were created to make some sense towards the development of the characters so they could end up in the black hole of their own conscience.

Is the black hole a metaphor for purgatory, or hell, or both? Is the black hole a place or a state of being, or both?

That depends on each character’s view. For Cibele, the black hole was a portal to hell. When she pictured Agatha’s ex-husband falling into hell, the image that came to her mind was of him falling through the hole and not being able to escape his fate. Agatha had absolutely no idea of it whatsoever. And for Amy, she always saw it as a celestial object, one of the mysteries of astronomy. In the overall context of the book, the black hole becomes the metaphor for Cibele’s vision of a portal to hell. In different interpretations, it could be either a place or a state of being.

It seems two characters undergo transformations as a result of things that happen to them. One character seems to learn and evolve from her experiences, while the other character is corrupted by greed and vanity, degenerates, and her path spirals downwards into the black hole. Would you say one of the themes of this novel is we all make moral choices in life and those moral choices determine where we end up in a spiritual sense?

Yes, one of the themes associates each character’s personal choices with their outcome. Their conscience should dictate their behavior, but in the novel, two of the characters become blind to their own fates, preferring instead to blame everyone and everything for what happens to them, instead of taking responsibility for their actions, which they never acknowledge.

One of your characters seems to be innately evil. Are some people born evil, or is it more life experiences and moral choices that make them turn evil?

The feedback of her life is designed to instigate some empathy in the readers for her actions, but that is not a justification for how she turns out. Her selfishness, bad choices, and desire to succeed are the catalysts for her transformation into someone with evil instincts. Everyone has choices to make, and the environment and the state of mind could contribute to the development of evil instincts.

There is a debate within the novel about the existence of hell after death and experiencing hell within life. Do you believe that after death, purgatory, heaven or hell awaits all human souls? Or would you say we experience these things within this life?

I don’t really believe in a hell created by god to punish us. I don’t believe in a punishing god, only in a good one. I suppose you can create your individual hell on earth if that’s how you decide to live your life. Happiness and goodness are a state of mind, as well as sadness and evil. Some people love life, some people hate it. It’s all in the mind’s perception, it’s the conscience. Whatever you believe in becomes your reality.

Tell us a little more about the massive black hole. We know about black holes from astronomy, but you seem to be saying these black holes exist in a spiritual sense. Do you believe each of us may fall into our own black hole, and we therefore need to be vigilant with our moral choices to avoid such a fate?

As I mentioned before, Cibele sees the black hole as a portal to heaven. The heaven she believes in is like the painting by Bosch. Agatha doesn’t believe in anything. Amy believes the black hole is what it is in astronomy; a place in space where gravity pulls so much that even light can not get out. In Cibele’s vision, a sin will condemn you to this physical hell. Ultimately, it’s their conscience that dictates their ending. Amy experienced Cibele’s hell vision when she was in a coma. Cibele never experienced her own vision of hell, instead, hers and Agatha’s ending stemmed from their fear of being stuck, of never moving ahead, of being rooted in their unfortunate predicament. The metaphorical use of the black hole could signify being stuck, not moving, falling into a routine where your dream of salvation (from whatever you want to be free of) never comes.

And what of heaven? Does any character achieve heaven within life or after death?

That, in the scope of the novel, would be their conscience, their state of mind. In that aspect, I could say that Amy achieved peace with her fate. Could this peace be considered heaven? That’s totally open for interpretation!

Will there be a sequel and/or a prequel to Massive Black Hole?

No, I wrote this novel as a single volume.

Thank you Andrea. I wish you great success with your writing. Where may readers buy your books?

Thank you so much for the great opportunity to interview for your blog. You may find me at:

https://www.amazon.com/Andrea-Barbosa/e/B00DGXPK6W https://twitter.com/AndyB0810

http://massiveblackholenovel.blogspot.com/

https://www.facebook.com/massiveblackholebook/

The post An interview with Andrea Barbosa about her novel ‘Massive Black Hole’ appeared first on Peri Hoskins Author.

September 12, 2016

The Inspiration for Writing ‘East’

In 1994 I travelled all around Australia in a car. That road journey was the inspiration for ‘East’. I took the journey wanting to write a novel about the people I met, the places I visited: my experiences. I took notes as the journey unfolded. Soon after the journey ended I visualised the front cover of the novel. And that is exactly how the front cover looks today: 22 years later.

In 1994 I travelled all around Australia in a car. That road journey was the inspiration for ‘East’. I took the journey wanting to write a novel about the people I met, the places I visited: my experiences. I took notes as the journey unfolded. Soon after the journey ended I visualised the front cover of the novel. And that is exactly how the front cover looks today: 22 years later.

For 22 years I carried ‘East’ at brain edges. I was pregnant with it. I knew some day the novel would be born. I had to write it, and I had to find time to write it. I was busy in those years, mostly busy earning a living. There was never enough time to write this novel, not as I wanted to write it: slowly and carefully, putting care into each sentence. The novel has now been written. It has been born. And I’m proud of it. Jack Kerouac said his novels were his children. ‘East’ sure feels like a child of mine.

I read Jack Kerouac’s ‘On the Road’ in my twenties and loved it. I’ve wondered whether I would have taken this journey if I’d never read that book. Probably not. So I owe a big debt to Kerouac for inspiring me to go on this journey, and to write about it. And for the immediacy of Kerouac’s writing. That immediacy is there in ‘East’. The other inspiration for writing ‘East’ is there within the opening chapter: the suffocating, petty and circular working life. And the need to be free.

‘East’ is out now at these digital stores: www.books2read.com/east

Send to Kindle

Send to KindleThe post The Inspiration for Writing ‘East’ appeared first on Peri Hoskins Author.

August 18, 2013

Understanding Dharma

The western world has become familiar with ‘karma’ sufficient for the word to be absorbed into everyday language. People understand karma as payback for wrongdoing meted out by the invisible hand of the universe. People talk of ‘good karma’ and ‘bad karma’ and ‘quick karma’. Perhaps the well-known saying ‘what goes around comes around,’ sums up how we in the west commonly understand karma.

Not so with ‘dharma’. Few western people know what dharma is. The word is therefore little used in our day-to-day conversations. If Jack Kerouac’s 1958 novel The Dharma Bums had made the same impact as On the Road, published a year earlier, dharma may have taken firm hold in western consciousness. It wasn’t to be. Kerouac’s Dharma Bums foray into dharma with Buddhist poet friend, Gary Snyder, has not been popularized. We do however know about an accomplished car thief, Neal Cassady, made famous by On the Road as Kerouac’s ‘western kinsman of the sun.’

Both karma and dharma come from Hinduism – the most ancient of the world’s religions and mother tradition of newer dharmic faiths Buddhism, Jainism and Sikhism. Deepak Chopra mentions both in his 1994 book The Seven Spiritual Laws of Success. Karma is included as the third spiritual law in the chapter entitled The Law of “Karma” or Cause and Effect. Dharma features as the seventh and final law of success in the chapter entitled The Law of “Dharma” or Purpose in Life. Chopra defines dharma simply as a Sanskrit word meaning ‘purpose in life’. While this broad-brush definition works for this book, dharma means a whole lot more than that.

Dharma is one of those big non-western ideas that are hard to define. It has been translated as ‘religion’, ‘duty’ and ‘righteousness’. While dharma includes all these things, they do not define it. Other broad ideas from outside the west also evade easy definition. The indigenous Maori people of New Zealand (Aotearoa) have a word ‘mana’ that has been translated as ‘honour’ or ‘prestige’. This Maori word has crossed over into everyday use within New Zealand. Most New Zealanders have some idea what mana means. Although mana includes both honour and prestige the word means more than those things. The meaning of the word is better illustrated by an example from Maori society. A person who has acted selflessly in the best interests of the tribe (iwi) and/or the clan (hapu) and has as a result gained standing, influence, honour and prestige is said to have ‘mana’.

The origins of dharma are to be found in India, in one of the most ancient scriptures known to humanity, the Rig Veda. This first Vedic scripture dates back in oral tradition to the late Bronze Age – about 1,400 BC. The Rig Veda spoke of ‘Rta’ – the idea that natural justice and harmony pervade the natural world and there is a power behind nature keeping the natural world in harmony and balance.

Several hundred years later dharma, as we now know it, appeared in the pre-Buddhist era Brihadaranyaka Upanishad (the Great Forest of Knowledge Upanishad). In this scripture dharma is seen as truth. The intelligent force behind nature, rta, had become more than the universal principle of law, order and harmony, it had become dharma – all those things and pure reality – in a word, truth.

The Wikipedia definition of dharma is ‘that which upholds, supports or maintains the regulatory order of the universe’. ‘Adharma’ is the opposite of dharma and refers to that which pulls the universe down and into chaos. Unsurprisingly, the Hindu encyclopedia, Hindupedia, provides more in depth analysis. It confirms dharma ‘has no direct translation into English,’ and states dharma ‘can be thought of as righteousness in thought, word, and action.’ Hindupedia offers as another interpretation: ‘the collection of natural and universal laws that uphold, sustain, or uplift. That is law of being; law of nature; individual nature; prescribed duty; social and personal duties; moral code; civil law; code of conduct; morality; way of life; practice; observance; justice; righteousness; religion; religiosity; harmony.’ Dharma is said to represent a ‘principle’ or ‘quality of being’ capable of wide use in ‘a variety of contexts to mean a variety of different ideas.’

Hindupedia goes on to discuss dharma as: cosmic order; a social order; a civilizational principle; ethical behaviour, duty or responsibility; service to the community; self-expression; and a means for attaining eternal nirvana.

In order to understand dharma at a cosmic level we need to first see the universe not as a loose bundle of disparate elements but rather as an interwoven web of countless interdependent strands. Dharma is the intelligent cosmic order underpinning and sustaining this web.

Moving from the cosmic order to the social order of humans, dharma allows us freedom to express and experience so long as we respect others in doing so. A father who delivers his child to school supports and upholds the child and is therefore true to his dharma as a father. The community and the nation also benefit from the father’s support of his child. If however a father abuses his child, the result is adharma – a chain reaction of disharmony feeding out from the family, to the community, the nation and ultimately the universe.

At a community level, dharma is expressed in self-lessness, putting the greater good of the community ahead of personal gain. In serving our communities our lives are given meaning and purpose beyond our selfish existence. Supporting and uplifting others within our communities nourishes our souls.

Dharma is also the means by which the purpose of human life – eternal nirvana – will be achieved. A dharmic life will facilitate the evolution of the human soul to a state of eternal bliss and final liberation from the cycle of birth, death and rebirth. Hindus also believe nirvana may be achieved here and now on earth – there is no need to die and find it in heaven.

In western nations the individual is the most important member of society. Each and every individual has legal rights against each and every other individual. The most easily understood aspect of dharma for western people is therefore likely to be individual dharma or dharma as self-expression.

In order to understand dharma at an individual level we must first see human life as an essentially spiritual journey. As discussed, dharma is truth incorporating universal law, order and harmony. An individual following a dharmic life will therefore undertake a spiritual journey seeking and following truth.

The source of an individual’s dharma lies within the nature of each individual, his or her unique talents and abilities. As Hindupedia puts it ‘ultimately a human being uplifts himself, sustains and upholds his spirit, when he or she truly fully develops and expresses his or her unique gifts in the service of humanity.’ Dharma is therefore integral to the ‘flowering of a human being … this developing of an inner potential and possibility to its full height and range of expression, this unfolding of human genius consistent with the individual’s inner law of being and action.’

What is to be learned from dharma? As individuals if we connect with our dharma we will find and follow our true purpose in life. That path must be ethical because, in common with Christianity, dharma includes the principle ‘do unto others as you would have others do to you.’ The products of our work will be the expressions of our unique talents. And our unique talents will contribute to the greater good of humanity. If we follow dharma we will evolve in accordance with our higher spiritual purpose and uphold and support our families, our professions, our communities, our nations, and the entire universe.

References

On the Road by Jack Kerouac, Part One, Chapter One

The Seven Spiritual Laws of Success by Deepak Chopra at page 95

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rigveda see Dating and Historical Context

Rig Veda at 10.133.6 as cited by Wikipedia http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dharma

Brihadaranyaka Upanishad 1.4.14 as cited by Wikipedia http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dharma

Wikipedia http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dharma

Ibid.

Hindupedia http://www.hindupedia.com/en/Dharma

- 15. Ibid.

Send to Kindle

Send to KindleThe post Understanding Dharma appeared first on Peri Hoskins Author.