Touré's Blog

September 1, 2011

Unpacking "No Church In The Wild"

Jay-Z’s verse on No Church In the Wild is one of the most interesting on Watch the Throne as it combines religion, spirituality, and philosophy. I tried to unpack most of what I heard but I’m sure there’s things I’m missing. It’s a deep verse. (Again, my point system is based on amateur boxing with 2 points for great lines, 1 point for good lines and 0 for anything else. But in this verse there's no 0s.)

Tears on the mauseoleum floor

Blood stains the coliseum doors

[2 points for the first line and 2 points for the second—These are great, brief images, like complex snapshots made by words—those sorts of photos that seem to suggest a scene. These give us moments of power asserting itself on weakness. In some grand, giant building, a mauseoleum, someone has been made to cry. On the door of the grand, giant stadium someone’s blood has been spilled. (Possibly many someones.) In societally-massive places someone has hurt someone else and left the mark of it behind. Thus Jay-Z slides into the song as a detached narrator, passing no judgment on these scenes, like a director starting the film with still images that tell so much but leave many questions, too. Also, really nice poetic work here rhyming a pair of four-syllable-then-one-syllable words.]

Lies on the lips of a priest

Thanksgiving disguised as a feast

[2, 2—In the song’s first two lines, the images were literal but in these two lines the images have turned figurative. But still we have power asserting itself on weakness. Priests were once among the most powerful men in society—a time evoked by words like mauseoleum and coliseum. This lying priest is hurting the people who believe him absolutely just as the person (or people) who cried and bled in the previous lines were hurt. Also, this figurative image becomes more literal because the previous two lines were literal so he’s accustomed you to see images from the words so that when you get a figurative line you see that, too. So I visualize the lies—these malicious words sitting on his lips like diseased spittle, about to fly out to the people’s ears. The following line (about Thanksgiving) concludes the series of images with a celebratory moment that’s really a Trojan horse allowing the powerful to take advantage of the weak. Interestingly, the first three lines suggest old Europe— mauseoleum, coliseum, a place where Priests had hegemony—while the fourth line, the line about Thanksgiving, clearly evokes early America, though perhaps at the beginning of America they were still more European than American. Perhaps.]

Rollin’ in the Rolls-Royce Corniche

[2—All these lines are getting 2’s because of the overall story they’re telling and how well they fit together to build something that’s greater than the sum of the parts. Is this particular line great in a vacuum? Maybe not, though the alliteration is nice, but what makes it great is how it fits with the lines we’ve been given before. Jay’s been a detached narrator so far, giving himself no place in the story and not even passing judgment on the scenes he’s painting. Here he enters the story in style. In style linguistically—there’s an elegant subtlety to how he inserts himself into the narrative. He doesn’t say “I” but you know it’s him rolling in that expensive car. It’s almost like he’s driven into the story casually—because you wouldn’t drive that car fast. Keep this image in mind—Jay driving. He’s not just bragging. He’s placing himself as a character within the narrative. This is the moment where the verse becomes something of a scene.]

Only the doctors got this, I’m hidin’ from police

[2—Jay’s been talking about the interaction of power and weakness but here he locates himself within that conversation but he makes it unclear who’s got the power. He’s got a car that only doctors can afford, that only the rich can get, so it’s a signifier of his power but he’s gotta watch out for the police because they’re the power and they’ll stop him for Driving [An Expensive Ride] While Black. So Jay’s both powerful and not so powerful at the same time.]

Cocaine seats

All white like I got the whole thing bleached

[2, 2—More great, precise imagery. The whole car is cocaine white, the crispest, sharpest white available. This continues the tangible, writerly detail he’s been giving us the whole song. And the bleaching is not just a reference to the car itself. “The whole thing” refers to Jay’s business and persona—he was in the streets and now he’s bleached his life. He’s clean. He’s a business, man. “Cocaine seats” puts the ghost of his old life into the air but we know there’s nothing that cops can stop him for. Except maybe Driving While Black.]

Drug dealer chic

I’m wonderin’ if a thug’s prayers reach

[1, 2—Drug dealer chic is what Jay’s style is all about but it’s not a line that’s blowing me away. But it links nicely with his allusions toward his coke-dealing days and his next line (I’m wonderin’ if a thug’s prayers reach) which goes back to the interplay between power and weakness and who’s truly powerful as well as launching us toward the religiosity alluded to in the song’s title and intro and discussed in depth in the next few lines. But it’s a great line in and of itself, a great philosophical question—do the prayers of an immoral criminal reach God’s ears? Does God take care of everyone or just those who are good? Keep in mind “I’m wonderin…” which may seem like a throwaway but isn’t—it’s there that the verse starts a trip into his mind. I see him cruising in his Corniche, pontificating, gettin all philosophical and shit.]

Is Pious pious cause God loves pious?

[2—This is an awesome line that deserves much more than 2. Jay’s taken the spiritual/philosophical question of the previous line to another level and dropped a deep and legendary philosophical question. This is the legendary Euthyphro dilemma in which Socrates asks “Is the pious loved by the gods because it is pious or is it pious because it is loved by the gods?” We’re talking Socrates now? We’re asking what is the source of what is Godly? Why are the things considered morally good considered that? How do we know what is Godly and why? In a polytheistic society, like the one Socrates lived in, this question was all the more complex: what if one god favors one behavior and another does not? This line, right after wondering if a criminal’s prayers would be answered by God, makes for a really deep pair of thoughts. In quick succession Jay’s wondered about the relationship to God of society’s moral lowest and highest. This, in a pop song?]

Socrates asks, “Whose bias do y’all seek?”

[2—Before he quoted Socrates, now he name checks him and gives us his own summary of what Socrates is saying. Whose opinion matters to you? Are you following reason or faith? This is a pop song?]

All for Plato, screech

[2—Now he’s naming Plato, Socrates’s homie. I can’t believe this sort of philosophical discussion and historical namechecking is flowing so smoothly in a pop song. But the 2 points here really goes to the seemingly insignificant “screech” which is a pivot point in the verse. It’s an onomatopoeia, of course, but it works two ways stopping two things. First it stops this line of deep philosophical discussion he’s been giving us. This is the pivot where he turns sharply and moves away from philosophy and into more classic Jay talk. But also, go back to the image of him in the car, when the Rolls enters the narrative. Jay describes the Rolls that he’s sitting in then says “I’m wonderin…” and the lines after that are a continuously deepening series of philosophical thoughts moving from a thug’s relationship with God to Socrates’s pondering the nature of piety. All these are thoughts he’s having as he’s rolling in the Rolls. It’s as if the voice of his inner monologue had been going in a voiceover. And then the car—the vehicle in which he’s having these thoughts—comes to a hard stop, a screech, and he snaps back to real life.]

I’m out here ballin’, I know ya’ll hear my sneaks

[2—Here’s a nice little double-entendre. He’s out in the streets ballin—either living large and/or playing basketball. If the latter you’d hear his sneaks, because while playing sneakers naturally squeak and even, maybe, screech. Or, if you’re ballin as hard as he is, your sneakers would be immediately noticed, or perhaps so stylistically loud they’re heard.]

Jesus was a carpenter, Yeezy laid beats

[2—Clever, clever: One third of the real Holy Trinity built literal things while Kanye builds music piece by piece, similar to carpentry. If that were the whole idea then this would maybe get a 1 but it’s followed up by…]

Hova flow the Holy Ghost, get the hell up out your seats.

[2—Damn the payoff is large: Jay-Hova is another third of the Holy Trinity he’s describing (along with Yeezy). He’s always talked about his writing and rhyming ability is beyond conscious, it’s God-given—as if it’s God flowing through him, he says. There’s something mysterious about the Holy Ghost and something mysterious about his ability to him, so it makes sense for him to link himself to that in this analogy. Who’s the God in this triumvirate? Is it God or is it the audience? Also, knowing Jay, he didn’t place the word hell there lightly, at the end of a verse filled with references to religion, spirituality and philosophy.]

Preach

[1—This is interesting. It’s a cool way to finish a verse that’s had so much religion and philosophy in it and it nicely lands the verse in a single word that locates us within the Black church experience as “Preach!” is a normal part of the call and response in a Black church. But “preach” is never an exclamation you use to praise something you have said. It’s always to praise something someone else has said. So for Jay to say this about his own verse is a bit weird. I wonder if it might’ve been better for Kanye to jump in here and say this word, speaking about Jay’s verse and then for Jay to say it about Kanye’s verse at the end of the song.]

August 10, 2011

Jay Electronica's Exhibit C: Decoded

In the intro Jus Blaze says “In the hearing against The State of Hiphop vs Jay Electronica.” Thus Exhibit C is the third and final exhibit or argument but what is the charge? Is it do you belong in hiphop? Is it do you deserve to be in the game? I’m not quite sure but I like that he sets this up as if he’s completing an almost legal case to prove his dopeness, his belonging, his necessity to the game. And that means there’s a reason given within the text for him doing this song: he’s on a trial of sorts with the state of hiphop as the plaintiff and him as the defendant. Most songs don’t offer a reason for why they exist, for why the person is telling the story or saying the rhymes and I like that this song gives it’s own reason for existence. This song is the most autobiographical of the 3 Exhibits, the one where he’s testifying—in both the legal sense (it’s a case) and in the Black cultural sense, testifying, telling his life story. This song is him laying himself bare before the court and saying this is who I am and where I’ve come from and how I got to be who and where I am.

This is a song that fits into the vaunted Black memoir/autobiography tradition—Malcolm X, Black Boy, I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings, Manchild In the Promised Land, Assata, Monster, Makes Me Wanna Holler, etc — most of which, Skip Gates has pointed out, could be subtitled Up From Hell.

This is also a song that follows the classic Growth of A Savior story structure as does, say, the Matrix. (Electronica often refers to himself as a savior.)

Both Jay and Neo are literally and, more importantly, figuratively sleeping when we meet them.

Neither Jay nor Neo are looking for enlightenment. They’re not on a quest.

Wise men come to them offering knowledge and, critically, saying I see something special in you. This is something Jay and Neo don’t see.

Because of the wise men they begin a journey that is both physical and internal.

The journey leads to them ultimately realizing who they are and the power they have and accepting that they are indeed saviors: Neo for the postapocalyptic world, Jay for hiphop.

This is a song that is, in a literary sense, extremely efficient. Every part of it works and matters and is necessary to build to the final conclusion. If it were a machine it would be one with no extraneous parts, no unnecessary movements. Most hiphop songs have non-sequitors and misdirections and if they were people they might run like say Barry Sanders, with side moves and jukes and then some straight running and then a curved movement around someone. That can be beautiful. But I like that this song is, in a literary sense, like Usain Bolt: it runs in a straight path from its beginning to its end.

I also appreciate that Exhibit C, in a narrative sense, makes the shape of a capital Q. Where great stories come full circle, this one comes full circle and then, at the end, goes a brilliant step further.

Where most autobiographical songs in hip-hop are about where the person is from, and almost suggest the person has hardly visited anywhere else (because they’ve kept it so real they hardly ever leave home), this one begins far from home, never visits home, and is about Jay’s movement through the Eastern part of the country and that geographical movement mirrors and motivates Jay’s personal development.

The Song:

“When I was sleepin on the train…”

This is a deceptively deep beginning: there’s a double entendre and a doubling of movement. Sleeping is a double entendre in that he’s literally sleeping and figuratively sleeping—figuratively in the 5 Percenter self because he lacks knowledge of self. There’s a double sense of movement because while he’s literally in motion (on the train), he’s also in motion in a literary sense: the song begins in motion, in medias reas (Latin for: in the middle of things).

“sleepin on Meserole Ave out in the rain…”

Meserole Avenue is in Greenpoint, Brooklyn which is interesting: here’s a New Orleans MC whose most autobiographical song begins in Brooklyn and whose style is very New York. But he’s still attached to the South—he’s sensitive to Southerners getting dissed by NY MCs (as we’ll see in a moment). The historic schism between Southern and NY hiphop is at play within this song.

“without even a single slice of pizza to my name

Too proud to beg for change, mastering the pain…”

“Too proud to beg for change” is a deep double-entendre: he’s too proud to ask for money and too proud to ask for his life to be altered. And even though he was a bum sleeping on the street, he still had pride, dignity and character. Even at his lowest he wasn’t begging for anything.

“when new york niggas were calling southern rappers lame, but then jacking our slang.”

This is an artful way of establishing a time period, when Southern hiphop was getting dismissed by NYers but still was powerful enough to influence NY. It also establishes, for a second, his Southern hiphop pride, in spite of everything else in the song being a love letter to NY hiphop: the producer he’s employed, the MCs he references, the people he notes are reaching out to him, the way he rhymes, the place he starts the song in…

“I used to get dizzy spells…”

This would actually happen to someone who’s homeless and not eating properly or consistently, but this is also a classic literary device: the voice of the future, of a ghost, or the Gods, speaking to this special person when they’re downtrodden, long before greatness comes.

“and hear a little ring, the voice of an Angel, telling me my name, telling me that one day I’ma be a great man, transforming with the MegatronDon spittin out flames…”

The use of flames is interesting here as the next line is about eating other MCs so it’s almost as if they’re being flame-broiled before being devoured like Burger King burgers. I like, too, this elegant shout-out to Jus Blaze the MegatronDon. It was prophesied that I would rhyme with you. And here I am actually doing it.

“eatin wack rappers alive shittin out chains.”

I love this line because it’s so visual. I can see two MCs standing there, facing each other, and then one opens his mouth absurdly wide and eats the other one whole, digests him, then pulls down his pants and defecates out a thick gold rope chain and walks off. Nice. MCs are constantly saying I’m better than you, I’m the best ever, you can’t see me, but Jay’s not actually making the boast: an angel (or a voice in his head) is telling him he will be great one day. So he gets away from the over-bravado that can be tiresome in hiphop by having someone else telling him this will happen for you one day.

“I ain’t believe it then…”

I love this: he cuts through the potential arrogance of the angel’s predictions and brings you screaming back to the narrative’s present. I can see this angel telling him he’s going to be incredible and he’s like, I don’t buy it. It’s like we’ve been getting a Technicolor opera telling him you’re gonna be major and he turns to the camera and blankly says, what? But the last word “then” is crucial. I didn’t believe it at that point but later on I would.]

“Nigga I was homeless. Fightin, shootin dice, smokin weed on the corners, tryna find the meaning of life in a Corona

Love that last line! Especially because alcohol is often referred to or thought of as truth serum.

“Till the 5 Percenters rolled up on a nigga and informed him.”

The grammar here is crucial: did the 5 Percenters inform him of the meaning of life or that you either build or destroy? Perhaps both. This is a crucial entrance of the first real characters into the story: up to now he’s either been alone or speaking to a ghost (who may or may not be real, that could be him hearing voices).

Also, if you’ve been listening to hiphop for a long time you know in the 80s and 90s the 5 Percenters were a powerful presence in hiphop, giving us great, conscious, complex hiphop and if you miss great, complex, thoughtful hiphop, you partly miss the influence of the 5 Percenters. So when he says, my life was transformed by the Gods, it’s like, oh snap, we might be about to get into some serious hiphop here! Course we already know that because of the rhymes he’s kicked, but in this way the story justifies itself at this point.

“ ‘You either build or destroy. Where you come from?’ ”

“ ‘The Magnolia projects in the 3rd ward slum.’ ”

“ ‘Hmmm… it’s quite amazing that you rhyme how you do…”

I find this interesting and a bit funny because the character in the story has never even mentioned MCing. We have no idea that he’s an MC from the information provided to us in the text so how do these 5 Percenters who just now rolled up on him know how anything about how he rhymes? I assume they caught him in a cipher and rolled up on him or heard of his reputation but ultimately it’s one of those leaps in a movie you just accept. But I do love how his MC persona in the song is immediately established as astounding which mirrors how he came into hiphop: astounding from early on, the same way, say, Nas was astonishing from his first widely-known rhyme. So we have two separate movements: while the character is growing from nothing, homeless, into something, moving into spirituality and knowledge of self, the MC within the character is introduced as amazing.

“ ‘and how you shine like you grew up in a shrine in Peru.’ ”

They again give him a massive compliment: you shine, brilliantly. This is a hiphop compliment but here from spiritual guys it speaks of something deeper. They see a light coming from him, he’s special. Again, he’s bigging himself up but putting it in other people’s mouths so it doesn’t sound arrogant. But this line is like the angel telling him he’s going to be great before he knows it and it also points directly toward the song’s final line. At this point he doesn’t yet know he’s shining brilliantly. Later he’ll know.

“Question 14 — Muslim Lesson 2: Dip diver, Civilize a 85er…”

That was quick. He met the 5 Percenters in the graf beforehand and now he’s quoting Muslim lessons by number. He’s growing by leaps and bounds! I’m not being disingenuous, the narrative has leapt forward and it fits because in a moment we’re about to go into a swift montage.

“I’ll make the Devil hit his knees and say the Our Father.”

This is the first time in the song Jay brags in his own voice and interestingly it’s about his religious or spiritual power not his rhyming ability. He’d rather tell you he’s got a powerful spirit than say he’s a dope MC.

“Abracadabra!”

Magic! Blam! I changed! I grew! I started to become the man you know. Here comes the montage, which always signals transformation.

“You rockin with the True and Living

shout out to Lights Out, Joseph I, Chewy Bivens.

Shout out to Baltimore, Baton Rouge, my crew in Richmond.”

He’s all over the place. Where most MCs rep for one area and give you a microscoped view of that area, this guy breezes through the many places he’s lived.

“While y'all debated who the truth was like Jews and Christians…”

While you debated what’s real, I knew what was real. You were dealing with two false answers, arguing between them, while I had the right answer and wasn’t debating but was moving around, making moves, becoming me.

“I was on Cecil B, Broad Street, Master, North Philly, South Philly, 23rd, Tasker…”

Philly

“6 mile, 7 mile, Hartwell, Gratiot…”

Detroit

“Where niggas really would pack a U-Haul truck up,

put the high beams on, drive up on the curb at a barbecue and hop out the back like ‘What’s up?!’

Kill a nigga, rob a nigga, take a nigga, bust up!”

That’s a courageous sort of crime. Damn. Dream Hampton points out that this is some Detroit shit. She said: “Murder capital. Post industrial wasteland. Where Trick Trick robs Young Berg for his chain then declares a no fly zone for national rappers. The most dangerous place of his travels and where he began recording (ironically at Eminem’s studio, Effigy Farms, with Mike Chav, his Detroit engineer who provides his distinct soundscape. Detroit is where Jay takes on the name Electronica after listening to techno, and where he recorded 80 percent of his pre-signed stuff.”

“That’s why when you talk the tough talk I never feel ya. You sound real good and you play the part well, but the energy you givin off is so unfamiliar.”

This is a really cool, smart way of establishing his thug authenticity and saying the “y’all are studio gangsters” thing that most MCs say but in a much more elegant and specific way. You sound real, you act real, but your vibes are off. He’s saying game recognize game and I don’t recognize you. I love that he pins it down to I don’t feel y’all because later he asserts that you’ll feel my music, I give you an electric shock.

“Nas hit me up on the phone, said ‘What you waitin on?’ Tip hit me up with a twit, said, ‘What you waitin on?’ Diddy send a text every hour on the dot sayin ‘When you gon drop that verse nigga? You taking long!’”

Again, his development as an MC happens offstage or something because how did go from a nomad and a BBQ gangster to a widely-known and highly-anticipated MC with the likes of Nas eagerly awaiting his music? You may know the answer in terms of his actual life—and as dream points out he began recording Detroit which is the previous stop in the text—but I’m saying that within the text no discussion of him MCing is ever given which makes it slightly comical for him to suddenly have the whole industry hungry for him. But we can accept it because the rhyming in the song justifies it. I also like that he says people are using a variety of modern communication techniques to reach him. That contributes to the suggestion that people are dying for his music, that they’re coming at him from every direction: phone, tweet and text. And this is way cooler than saying the world is awaiting my album: it shows it.

“So now I’m back spittin that He Could Pass A Polygraph”

This is a very cool way of saying I keeps it real.

“That Reverend Run rockin Adidas out on Hollis Ave…”

I’m takin you back to that classical New York hiphop.

“That FOI, Marcus Garvey, Nikki Tesla.”

What a list. Hiphop heads obviously know about the FOI and Marcus Garvey and what he’s asserting by name-dropping them. But Nikki Tesla? I’d never heard of him before now. Tesla he’s a pioneer of modern electrical engineering, a man rumored to have been nominated for the Nobel in 1912. So he’s talking about being brilliant, being original and giving people an electric feel as he says in the next line. Dream adds: “Tesla is important because he’d found a way to harness electromagnetic (the Earth’s) energy. This is why Thomas Edison’s backers hired assassins to kill him. His path would’ve led to free energy (knowledge) as opposed to industries who charge a fee. Eventually, it was Tesla’s (stolen) technology that is responsible for cell phones.” So like Telsa, Electronica is trying to liberate electricity and knowledge.

“I shock you like a eel. Electric feel. Jay Electra.”

Quoting MGMT but again talking about electricity and more importantly making you feel his music.

“They call me Jay Electronica. Fuck that.

Call me Jay ElecHannukah. Jay ElecYarmulke.”

He’s making Judaism references because Blacks are the original Jews. But also it’s interesting that after the angel told him his name (and the 5 Percenters told him about himself) now he’s come to knowledge of self and he’s telling you his name. And the agency suggested by the grammar is important: first he says “They call me…” others call me, then he snatches agency: Fuck that. Here’s what I want you to call me. He takes control of his identity. That’s dope. It kindof reminds me of that epiphanal moment of self-actualization in movies about a search for identity: What’s your real name?! “Louis Cypher!” in Angel Heart or “Tyler Durden!” in Fight Club.

“Jay ElecRamadaan. Muhammad Asalaamica RasoulAllah Supana.”

Muhammad, Peace be upon Him, the Messenger of God. I am the Messenger of God… the savior.

“Watallah through your monitor.”

May He be glorious and exalted… through the speakers I’m blessing.

“My uzi still weighs a ton check the barometer…”

Obvious one for hiphop heads: Public Enemy’s 1987 song “My Uzi Weighs A Ton” gives you an uzi as Chuck’s mind, so not only is Electronica making another reference to classic hiphop, he’s also saying his mind is as powerful as a hi-tech weapon. But this has already been proven. (Yes, I know Electronica had a song of his own called “My Uzi Weighs A Ton.”)

“I’m hotter than the muthafuckin sun check the thermometer. I’m bringing ancient mathematics back to modern man. My momma told me never throw a stone and hide your hand.”

“I got a lot of family, you got a lot of fans.”

This is a great line and a crucial difference. Malcolm Galdwell’s first book The Tipping Point talked about the connections humans have between them as either loose ties or strong ties. Some artists may have a lot of loose ties—fans—where others have strong ties. If you have loose ties a million people may buy the album and like it but on your next album you have to win them over anew. An artist with strong ties may have fewer fans but they love him and will ride with him no matter what and when he puts out a new album they will have to prove to him that they still understand him and are worthy of him being onstage. Jay doesn’t have fans, who could be fickle, he’s got family: they love him and whenever he comes home, they’ve gotta take him in.

“That’s why the people got my back like the Verizon man. I play the back and fade to black and then devise a plan. Out in London, smoking, vibin while I ride the tram.”

This is so elegant in a literary sense because he’s brought the song full circle: he’s made it from New York and sleeping on the train to London tram largeness, hanging on the London tube by choice, indicating succinctly his size, his global nature and how far he’s come. And yet, even though he’s come far personally and geographically, he’s still the same dude, still smoking and vibin.

“Givin’ out that raw food to lions disguised as lambs…”

I’m here to improve people’s lives.

“And, by the time they get they seats hot,

And deploy all they henchmen to come at me from the treetops, I’m chillin out at Tweetstock…”

This is where the narrative structure goes from a completed circle (at London) into the extra bit that makes a circle into a capital Q. He’s gone to another location, a sortof post-global location where he can connect with people from all over the world. (Tweetstock is a festival where Tweeps come together, also called a Tweetup.) And more than that, bear with me, he’s there connecting with people who you’d normally connect with via computer, but now they’re in the real world which is kindof like Neo unplugging from the Matrix and realizing his true self and coming into the real world. Is that exactly what Jay meant? Probably not but there’s definitely significance in this final location being a sort of Internet place made real and thus in some metaphorical way taking him beyond the physical realm. This is as far as humanly possible away from being homeless on the subway. Unless he becomes an astronaut.

“Building by the millions. My light is brilliant.”

He now knows he shines as the 5 Percenters told him. He knows who he is. He’s now like Neo facing down Agent Smith, fully aware of his power. Ready to move forward on his mission to save hiphop.

Thoughts On The Ultimate Bragfest: "Otis."

KRS-One once told me hiphop songs are like confidence sandwiches. You put them in your mouth (and repeat the lyrics) and they make you feel the confidence of the MC. Much of hiphop is about bragging, either saying I'm so ill with these lyrics or I'm so tough on the street or I'm so good at making and spending money or I'm so smooth with the girls or whatever. I'm all in favor of Black men having bravado and brandishing their outlandish self-esteem, given that there seems to be a multimillion-dollar multimedia campaign to destroy Black self-esteem. Hiphop seems hell-bent on giving us examples of Black men with massive self-esteem. So I'm all in favor of a song like Otis, which is filled brags. It's a brag session: which of the two wealthy men can say the baddest brag. Let's go line by line and see which line/brag works and which, in my opinion, doesn’t. I’ve created my own point system based on amateur boxing’s 2-point system. A blah line gets no points, a good line gets 1, a great line gets 2. I’m giving points for writing and delivery, though admittedly a system like this doesn’t give enough credit for flow but that’s something that becomes apparent over time and over an MC’s relationship to many beats, not one. Jay’s flow is obviously much smoother than Kanye’s but the writing and the meanings and the subliminals that come from their pen are so important.

[Jay]

I invented swag

[2 points—In a song full of braggin this is a nicely audacious way to start. Sets the bar high. Sons others who talk about having swag.]

Poppin bottles, puttin supermodels in the cab.

[1—This is a nice brag, I take supermodels out and then get rid of them while you’d be slobberin over them but how am I to take this from a married man? It’d be better coming from Kanye. There’s so many realistic brags here this one strains credulity to me.]

Proof : “I guess I got my swagger back.” Truth .

[1—Clever. They sample Jay from All I Need, a ten year-old song.]

New watch alert: Hublot’s .

[2—This is part of Jay’s I invented swag ish. He’s good for bringing new luxury brands into hiphop’s consciousness. Hublot is a relatively new top-line watchmaker (around only since 1980) and it hasn’t been mentioned much if at all in hiphop. A brag with specificity.]

Or the big face Rolle.

[0—This isn’t much of a brag. Everyone knows Rolex. It’s considered a top-line watch but it’s the opposite of rare. After Hublot, to name-drop a top of line model of a common brand leaves me nonplussed. He probably had a hot Rolex when he got in the game and hadn’t gone much further than Maryland.]

I got two of those .

[0—Good for you.]

Arm out the window through the city, I maneuver slow .

[2—This line may not mean that much but it has a really nice poetic sense, just the words and the imagery—I can see him letting his left dangle out the Maybach window—and the way he says it is fly. Also, this comes just after talking about his watch collection, so saying he’s got arm out the window and is moving slow, because time is on his side, makes it work.]

Cock back, snap back . See my cut through the holes

[2—A triple entendre. First he’s cocked back his hat and you can see his hair cut through the hole of the hat. Also, if he’s cocked back a gun’s hammer you’ll see the cut of his diamonds through the Maybach window’s holes. And, in football terms, you snap the ball back to him and then see him cut through the holes in the field because he’s such a slick runner.]

[Kanye]

Damn Yeezy and Hov, Where the hell ya been?

[0—He’s clearing his throat. He’s been away recording this album. O-k. (He actually hasn’t been away at all in a world where we’re waiting for Dr. Dre, D’Angelo, Lauryn, Jay Elec…]

Niggas talkin real reckless: stuntmen .

[2—I hate this simile structure where you lose the “like” that Big Sean innovated but some, like Weezy, do it very well. Oh wait, this is Weezy and Drake’s thing. Has Kanye used their style to send a shot at them? Birdman is the stunna, which is from stuntin. By gosh I think he is returning fire—Birdman, Wayne and Drake have said little things about Jay and Kanye in recent months. And this is actually a great way of using that style—stuntmen are literally reckless so if you’re talking reckless your mouth is a stuntman as opposed to an actual star. Are there famous stuntmen? Notice how they’re good at concealing their faces as they do the stunts. He’s used their style to diss them and used it better than they do. Damn that’s cold.]

I adopted these niggas, Phillip Drummond ‘em .

[2—Drummond of course is the dad on Diff’rent Strokes, the character who adopted Gary Coleman’s Arnold Jackson. He was rich. It’s kinda obvious how dope this line is, how it sons everyone.]

Now I’m bout to make them tuck they whole summer in .

[2—He’s not going to make you tuck in your chain out of embarrassment about his being way better, he’s going to make you tuck your entire season in and not mention it because he’s going to flyer places in better jets with better chicks, shopping at hotter places and making hotter music. Living well is the best revenge and my whole life is better than yours Young Money.]

They say I’m crazy, well, I’m ’bout to go dumb again

[1—“Bout to go dumb” is some fly ish to say and we all know how hairy things can get when Kanye acts dumb.]

They ain’t see me cause I pulled up in my other Benz

[2—I have multiple Benzes. Much flyer than saying I have multiple Rolexes. Also a nice play on the ancient “you can’t see me” thing which is usually figurative but here, literal—you couldn’t see me because you expected me in one particular Benzo but I have two.]

Last week I was in my other, other Benz.

[2—Oh, no, actually I have three, or more, and you couldn’t see me last week either. Also, “my other other Benz” is also some fly ish to say.]

Throw your diamonds up cause we in this bitch another ‘gain

[0—More throat clearing. The Roc’s in the building. Got it.]

[Jay-Z]

Photo shoot fresh, looking like wealth

[2—Some very fly ish to say and perhaps the thing that could jump off the song become enudring lingo. “Photo shoot fresh.”]

I’m bout to call the paparazzi on myself

[2—A fly brag and a funny one. Jay stays ducking paps but right now he thinks he’s lookin so good he might have to let him know where he is to capitalize on that. But, in typical Jay restraint, he says “bout to” because he’s not actually going to do it.]

Live from the Mercer

[0—We’re recording this at the Mercer in Manhattan. Ok. Though it does locate him in a specific place leading up to the discussion of place in Jay’s next few lines.]

Run up on Yeezy the wrong way, I might murk ya .

[1—I’m still that guy and I’ll protect my little homie if need be. Don’t test me.]

Flee in the G450, I might surface .

[2—I’m still that guy but now I have wealth to help me escape if I need to. The Gulfstream G450 is a tip-top level private plane that’s especially good for long flights. When you’ve absolutely, positively got to flee the country there’s no more stylish way to do it. And his specificity here, name-checking a hot plane that he probably has, is fly.]

Political refugee, asylum can be purchased.

[2—This may be the best line of the song. I have enough money to buy political asylum anywhere. What’s more important than that? What’s a better brag than that? You can buy some stuff. You can buy big toys. Ha. If I needed to, I could go to any number of countries and buy my freedom. The world really is my oyster. Checkmate.]

Everything’s for sale. I got 5 passports I’m never going to jail.

[2—It’s between this and the previous line for line of the song. This of course continues the idea that I can buy anything including freedom, which I’ve already bought an insurance policy on—I’ve already got 5 get out of America free cards so how could I ever get locked up? That’s the peace of mind we’d all love to have. This, in a world where some think going to jail means credibility and proof of something, Jay’s like no, going to jail is wack and I’ve already set myself up so I’m never doing that. Wonder if this is a little shot at a lil someone who recently had to go to jail…?]

[Kanye]

I made “Jesus Walks” I’m never going to Hell .

[2—Of course this line ups the ante of the brag of the previous lines to a supernatural level: I’ve got a post-mortem Heaven guarantee because of my song. If you believe in Heaven and Hell then this is way better than being able to say you’re never going to earthly jail.]

Couture level flow, it’s never going on sale.

[2—Such a fly thing to say.]

Luxury rap, the Hermes of verses .

[2—That’s an excellent description for what Kanye’s doin.]

Sophisticated ignorance, write my curses in cursive.

[2—This is so fly and so Kanye. It doesn’t have to be explained.]

I get it custom, you a customer .

[1—Fly though I’m sure I’ve heard this before somewhere. Um, EPMD?]

You ain’t customed to goin through Customs? You ain’t been nowhere, huh?

[1—He spits this in a fly way but ultimately who’s he braggin to? Anyone who’s anyone in hiphop has been overseas to tour so… ?]

And all the ladies in the house, got ‘em showin off

[0—Huh?]

I’m done, I hit ya up mana-naaaah!

[0—Um, yeah.]

[Jay-Z]

Welcome to Havana

[2—This nicely dovetails with Kanye’s Spanish tomorrow but, more interestingly, nicely fits with what Jay said the last time he was on the mic about being able to flee anywhere and buy asylum. Surely, if needed to flee, Cuba would be a place to go. This is also an interesting reversal—a few lines from now he quotes Scarface and elsewhere on Watch the Throne Jay references Scarface but here he posits the Scarface journey in reverse: moving from America to Cuba as opposed to Tony Montana’s opposite journey. It also nicely sets the scene for the next line. It’s a simple line but there’s a lot set in motion by this line.]

Smokin Cubanos with Castro in cabanas .

[2—This gets a 2 because of it’s potential veracity. I wouldn’t be surprised if Jay has actually has met Castro and I’m certain that if he were to end up buying asylum in Cuba he‘d end up smoking high-quality cigars with Fidel.]

Viva Mexico, Cubano, Dominicano. All the plugs that I know.

[0—Now he’s just name-checking drug dealers in other places he might go to seek asylum? Ok.]

Driving Benzes, wit no benefits .

[1—His drug dealer homies are pushin the same fly cars that Kanye has and they’re getting theirs outside of the system.]

Not bad huh? For some immigrants.

[1—Those dealers aren’t doin bad at all but this line is nada special even though it’s a quote from Scarface. But it does signal the next two lines in which he’s talking loosely about immigration.]

Build your fences. We diggin’ tunnels .

[2—Immigration fences keeping people out? Please. My kinda peeps, my plugs, we can’t be stopped—we’ll just go under your stinkin fence. We go around the man. We’re unstoppable.]

Can’t you see? We gettin’ money up under you.

[2—This borrows shine from the previous line, makes the idea clearer: we’re getting money by all means necessary. Like them, I’m invading the economic system and getting paid and there’s no way you can keep us out. Blacks acquiring wealth is still a revolutionary and powerful gesture and I’m unmoved by arguments that “Jay’s just talking about being rich.” Being a rich Black man has political weight in this country even if he’s not overtly political.]

[Kanye]

Can’t you see the private jets flyin over you?

[1—This is a clever answer to the previous line: our largesse goes over you as our moneymaking schemes go under you. We’re everywhere you want to be.]

Maybach bumper sticker read “What would Hova do?”

[2—The visuality of this line is great: can you imagine a Maybach with a bumper sticker? That’s funny. But the bumper sticker plays off of Jay’s most audacious nickname, Hova from Hovah from Jehovah. He’s Godly and whoever’s driving this Maybach is asking themselves WWHD? Ill. It’s a little ass-kissy, but the Jesus to Hovah connection makes more sense and it’s better that Kanye gave love to Jay here rather than saying What Would Kanye Do?]

Jay is chillin, ‘Ye is chillin. What more can I say? We killin em

[2—Nice play off of Audio Two’s classic Top Billin.]

Hold up, before we end this campaign

[1—I like that he’s saying we’re almost done and more that he posits the song as a campaign, which can mean a series of military operations. Even in the political sense, it’s still a military operation albeit a verbal one.]

As you can see, we done bodied the damn lames

[0—We done did what we set out to do.]

Lord, please let them accept the things they can’t change

[2—He adapts the famous Alcoholics Anonymous prayer and sends his pity to the damn lames—they can’t change that we’re better than them. Can’t they just learn that?]

And pray that all of their pain be champagne/sham-pain.

[2—He ends with a double entendre—let them have celebratory alcohol instead of pain or let their pain be false, sham-pain. I wish them serenity and freedom from their pain. We’re so far above them we don’t even wish them to suffer.]

Who won the song? Well, predictably since they’re working and writing together they’re even: both at 31. (The competitive aspect of this scoring system works better when the MCs aren’t working together on the rhymes.) Looking inside the numbers, Jay has a triple entendre and the two best lines of the song. Can’t say one killed the other.

July 26, 2011

Karma: A Dogged Beast With An Elephant's Memory

The Casey Anthony case continues to fascinate me. It's not over. There will be more chapters. Will they be pretty? I've been following Casey on Twitter and she seems defensive, angry, extremely self-centered and probably unable to get out of her own way. Here's my video essay from MSNBC that gives you a glimpse at where I think she's headed.

What To Do You Do When You're Told, "You Ain't Black!"

When you experience the most humiliating moment of your life and you're a writer, you write about it. You push your public self aside in favor of your writer self. You sacrifice face in order to gain as a writer. Because your life is lived in order to gain experience that can yield material. Yes, your proudest moments can lead to great writing but your most embarrassing moments will almost always lead to great writing that people will want to read because it'll force you to challenge who you are. This is video of me reading about the most humiliating moment of my life, when someone said, "You ain't Black," and how it forced me to go deep inside and figure out who I am. I thought about not writing about it. Then realized I had to. This moment has shaped the rest of my life and is the genesis of my book Who's Afraid of Post-Blackness?

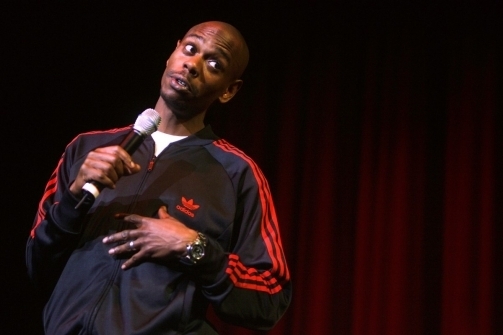

The Chappellologist At A Secret Show

For years Chappellologists have talked about Dave’s secret shows, the pop-up appearances. “Did you hear about the one in San Francisco that lasted six hours?” “He did a set in Tokyo?” “I heard he did a 5 a.m. show in Chicago.” We dream of catching a Chappelle stand-up performance because he was one of the best stand-up comedians of his generation and because of the sense of mystery that’s engulfed him after he suddenly left Chappelle’s Show in the middle of the third season. Like Lauryn Hill and Bobby Fischer, he abandoned the stage at the top of his game with genius and potential to burn, leaving behind so many questions. Why did he leave? Would he ever come back? No one knew, but maybe, if you could see him do stand-up, you could somehow find an answer. Or at least catch a glimpse of the great artist at work once more. And then someone whispered in my ear: “Dave might be at the Comedy Cellar tonight. The 1 a.m. set. Maybe.” Whoa.

I’ve got two little kids who wake up every day about 6 a.m., so going to a 1 a.m. comedy show is a physical challenge. It’d be hard to remain awake that late, and I’d surely be a zombie the entire next day. Could I risk all that on a maybe? Yes. I had to try. I settled in at 1 a.m. and laughed at comic after comic.

But by 2:40 a.m. I wasn’t laughing anymore. My eyelids were so heavy that my eyes shut against my will, and my neck was soggy. Was he coming? Had I wasted a night and the next day for nothing? I would’ve been depressed if I hadn't been so sleepy. And then the MC said, “Welcome to the stage a very special guest …” I snapped to. And there he was. My heart leapt.

He opened with an aside—“I’m so washed up”—then launched into a long story about a man in a spandex bodysuit and boots walking across the street from him. “I’m not a betting man,” Chappelle said, “but if I was I would’ve wagered that he was gay.” The man sees Chappelle looking at him and crosses the street, making a beeline for him. “I know who you are!” the man says. “You’re Dave Chappelle!” As an aside Chappelle told us, “I was once a famous dude.” We had no idea where the story was going, and we were on the edge of our seats. The man said, “I need your help, Dave!” He said he was gay and from the future and only Chappelle could help him. “You have to stop my father! He’s evil!”

“Who’s your father?”

Calmly, he delivered the punchline: “Tracy Morgan.”

The room exploded.

Then Chappelle laid back, bummed a cigarette and a light from audience members, and proceeded to meander through an hour-long set. Fellow Chappellologists, I am here to report that his comedy muscles remain cock diesel. His set was unpolished, he admitted as much. There was no theme and appeared to be no pre-planned order. He lurched from story to story and sometimes into improvisation with no reason for or momentum to his overall line of thought. But most of the stories he strung together were brilliant bits. He was letting us watch him practice, and Chappelle going through the motions is better than the vast majority of comics doing finished work. He moved through stories about recent news events—Anthony Weiner, Arnold Schwarzenegger, Tracy Morgan—and then paused to ask the audience what he should talk about, almost letting them direct the show. Someone shouted out, “Who’s worse? Arnold or Tiger?” Chappelle absolved them both and then moved into a bit about Tiger. When someone brought up Casey Anthony he claimed to have not heard about her. The outline of her story was given. He said sarcastically, “Now, that sounds funny.” Then he said, “I’m gonna read up on that. Next time you see me I’ll have 45 minutes on her.”

His bit about Tiger was based around the idea that he could’ve done way more. He’s a billionaire. Anything you or I could imagine, he can make happen. “You know what’d be great?” Chappelle said from Tiger’s point of view. “If I could get an alligator to bite my balls. But with just the right amount of pressure.” Three calls later he’s got someone on the line promising he can deliver just such a thing. “How much?”

Chappelle-as-Tiger said, “OK. How long would it take you to train it? Three months? OK, I can wait.”

About Weiner he said, “What good is the Internet if you can’t send pictures of your dick to people?” He later said he was going to start a website called Picsofyourdick.com with pictures of, well, you know. “To level the playing field,” he said. “Because of the Net you can’t be judgmental of anyone because everyone’s stuff is right there. I miss that.” There’s Dave’s brilliance—the outside of the idea was juvenile, but at its core it was a smart concept, the impact of the Internet on shame in modern society and how the Net’s inability to forget anyone’s foibles makes it harder to laugh at other people. I’ve read fuller unpackings of that idea in articles in The New York Times Magazine and Wired.

In the spirit of practice, Chappelle sometimes gave us endings without bits attached. He said, apropos of nothing, “The punchline was: And I realized I was smelling my balls.”

In many of the bits his fame was referenced in passing or directly. One story had him receiving a package at home with a note that had one word on it: “Gotcha.” Inside was a VHS tape. He races around the house looking for a VHS player—who has one of those anymore? He finds one in a closet and pops in the tape. It shows Chappelle having sex with a woman not his wife before he was married. Chappelle looks at the clock. His wife would be home in 15 minutes. “So,” he said, “I quickly jerked off to the tape.” Natch. Then a week later another package arrives. Another VHS tape. It’s a tape of Chappelle jerking off to the first tape! “So I jerked off to that.” The bit killed—nearly all of his punchlines did—but there you could see his fame creeping into his psyche and you could see his paranoia about being watched. This, even while he’s able to have fun with the fruits of being stalked.

In one key bit he discussed talking to groups of kids. He was asked to give them a piece of advice from his life. He said, “Don’t quit your show. I don’t know how any of y’all get by without a show.” Is he truly regretful, or is that just the funniest thing to say about all that? I interviewed him shortly after his return from self-exile in South Africa, and he seemed very settled with his decision to exit Chappelle’s Show. No one had forced him out.

But for me the important point wasn’t whether he was being honest or just being funny in saying, “Don’t quit your show.” The most telling part of that moment is that now Chappelle cannot do comedy without discussing himself, without doing surgery on his image. He must mention the show and the mysterious exit and that he “used to be a famous guy,” and the characters in his stories must recognize that he’s Dave Chappelle and act on knowing that fact or it’ll seem false that they don’t know him. Or he won’t be taking full advantage of the comedic potential if they don’t recognize who he is and react to that. Chappelle has become part of his own act in a way that recalls no comic since Pryor after he set himself on fire.

Most comics come out and do sketches and bits and aren’t a part of their own act. Steve Harvey and Ricky Gervais can do an hour without talking about themselves. Bill Cosby talks about his life, but it's normalizing, it's about him being a regular guy. Chris Rock opened Kill the Messenger with a bit in which he takes his family to Africa for a photo safari and eventually realizes everyone’s pointing their camera at him. When Rock talks about Rock onstage, it’s almost always innocuous; he's saying, "People notice me." The same night I saw Chappelle, uptown at Caroline’s Tracy Morgan was performing. Nowadays he must take a break from his set to do a bit about himself because of his homophobic comments. But that will pass, and a year or two from now Morgan will be back to doing stand-up without doing bits about Tracy Morgan.

Chappelle will forever have to talk about Chappelle—and by that I mean “Chappelle,” as in the icon who’s larger than him, the person who exists in others’ minds, not someone he sees in the mirror but someone he sees when he looks at the sum of his onstage/onscreen persona in his mind. Becoming such a big part of your own act suggests, perhaps, unwanted self-scrutiny. Because deconstructing yourself can be psychologically painful. You want to avoid doing that too much because it can mess with your head. You want to know why you’re famous, why you’re connecting with the audience, and what they want from you, but too much reflecting on “you”—i.e., the person the audience and the media see outside of the real you—can cause you to flip out. It’s just too damn meta.

At 3:45 a.m., shortly after repeating, out of nowhere, “Don’t quit your show,” Chappelle let the show end. There was no big, hilarious finishing bit. It kind of petered out and he was gone, back to the shadows. At a recent show in San Francisco he talked about a comeback without defining what that would even mean. That night at the Cellar, the word "comeback" was never even uttered.

This was shot by Mel D Cole at the Roots x Rakim show at which I asked Rakim & the Roots a few questions in the middle of the show then handed the mic to Chappelle.

Touré's Blog

- Touré's profile

- 95 followers