Roy Christopher's Blog

November 17, 2025

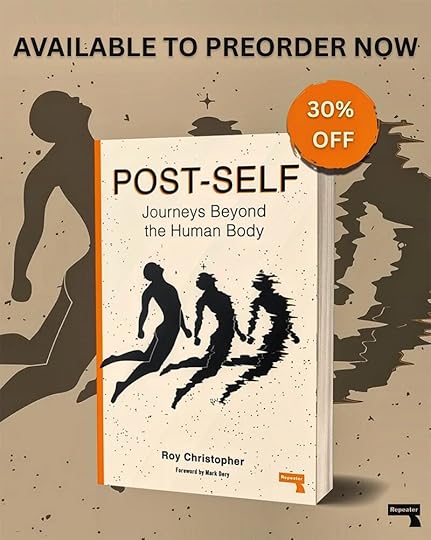

POST-SELF Preorders are 30% Off!

My next book, Post-Self: Journeys Beyond the Human Body, comes out on December 2nd from Repeater Books, and they’re currently running a 30%-off sale on preorders!

Post-Self is a grim survey of all the ways we attempt to escape the limitations of our physical forms—technology, rapture, drugs, death—with a Foreword by the cultural critic Mark Dery titled “Welcome to the Misanthropocene.”

“We are all perpetually holding ourselves together. Our breath, our blood, our food, our spit, our shit, our thoughts, our attention—all tightly held, all the time. Then at death we let it all out, oozing at once into the earth and gasping at last into the ether.” — from POST-SELF

The back cover copy reads as follows:

In the 21st century, the body has become a prison—a problem to solve, a boundary to break. Post-Self plunges into the dark urge to escape flesh and mortality by any means necessary: technology, cybernetics, drugs, death, or pure rapture.

From horror movies to heavy metal, from radical philosophy to science fiction, this book explores how artists, writers, and visionaries have imagined transcending the human form. What drives our desire to shed our bodies? What lies beyond the self?

Bold, unsettling, and fiercely intelligent, Post-Self journeys through the shadowlands of the modern imagination—where dissatisfaction becomes inspiration, and escape is the ultimate creative act.

“Once the soul looked contemptuously on the body, and then that contempt was the supreme thing — the soul wished the body meagre, ghastly, and famished. Thus it thought to escape from the body and the earth.” — Friedrich Nietzsche, Thus Spake Zarathustra

What other people are saying about it:“Too often philosophy gets bogged down in the tedious ‘working-through’ of contingency and finitude. Post-Self takes a different approach, engaging with cultural forms of refusal, denial, and negation in all their glorious ambivalence.” — Eugene Thacker, author, In the Dust of This Planet

“Using Godflesh—the arch-wizards of industrial metal—as a framework for a deep philosophical inspection of the permeable human form reveals that all our critical theory should begin on the street where wasted teen musicians pummel their mind and instruments into culture-shifting fault lines. Godflesh are not just a ‘mirror’ of all the horrors and glories we can inflict on our bodies, but a blasted soundscape of our moans. Roy Christopher’s book is a thought-provoking and delightful crucible of film, music, and the best kind of speculative thought.” — Peter Bebergal, author, Season of the Witch

“In his trademark breezy yet precise style, Christopher discusses everything from stimoceivers to Southland Tales, everyone from Henry Lee Lucas to Brummbear, and all without ever losing sight of his central points of reference: our all too malleable somatic limits and Godflesh’s Streetcleaner. And the combination here could not be more apposite, for however much we stretch and augment the reaches of our physicality, imagining ourselves the theophanies of some as yet speculative deities, we get no closer to getting away from ourselves, becoming Godly it seems only in the sense of becoming increasingly empty.” — Gary J. Shipley, author, Stratagem of the Corpse

“Through the lenses of Godflesh, J.G. Ballard, UFO phenomena, psychedelics, serial killings, and so much else, Christopher investigates humanity’s growing inclination to escape our bodies, to escape our species, to escape life itself.” — B.R. Yeager, author, Negative Space

“A peculiar hybrid of Thomas Ligotti and Marshall McLuhan.” — Robert Guffey, author, Operation Mindfuck

“An interesting read indeed!” — Aaron Weaver, Wolves in the Throne Room

Need an early Christmas present? Post-Self will be out in just two weeks, so go ahead and grab one at a 30% discount!

Thank you!

-royc.

November 5, 2025

Missives and Mentions

Close to the Bone is a UK-based publisher of crime fiction, short stories, and poetry run by Craig Douglas. They published a few of my short stories on their website, as well as my poetry collection, Abandoned Accounts, in 2021. Craig recently conducted the following brief interview with me for the Close to the Bone newsletter.

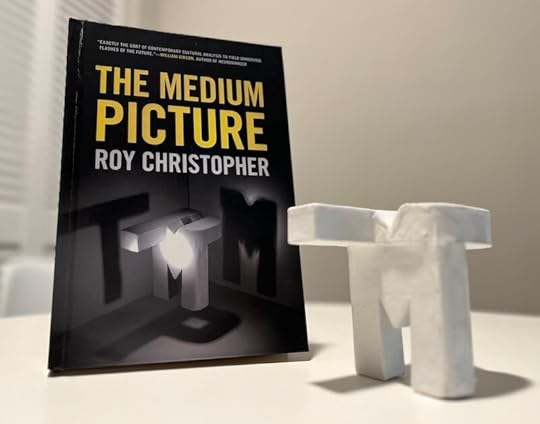

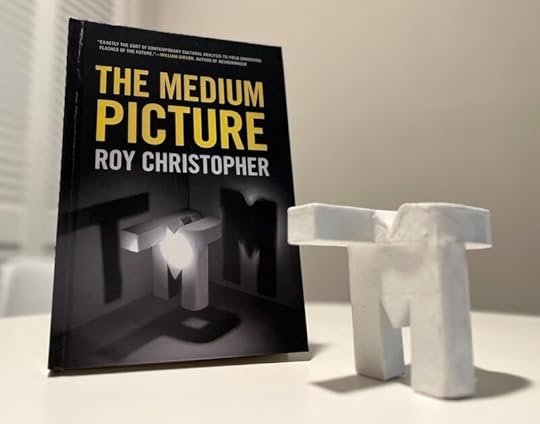

The Medium Picture

and its cover object.

The Medium Picture

and its cover object.Craig Douglas: Why did you want to write about how technology changes the way we connect with each other?

Roy Christopher: Because there’s always something in between—even in the most basic interactions. The poet Victoria Chang writes, “We read to inherit the words, but something is always between us and the words.” I find that interstitial space and the hidden processes at work there both frustrating and fascinating. I wanted to try and pry them open.

CD: Is there an old piece of technology that you think might have been the precursor to how we use our phones today?

RC: I think there are several, but for an example, I think the Walkman in concert with the cassette tape trained us for the devices we carry around now. That is, it trained our behaviors and expectations to allow for our adoption of the smartphone. The idea of personal media may have started with the book, but strapping on a Walkman was a big step toward our reliance on communication devices now.

CD: Do you think technology is changing who we are as a species?

RC: Yes, and I don’t think there’s a debate otherwise. We are changed with every new thing, from bags to wheels to clothes to eyeglasses to immunizations to houses to agriculture to electricity to cars to the telegraph, telephone, and television to the internet and smartphones to whatever comes next. Every new contrivance creates new possibilities for us and what it means to be human.

CD: If you could invent a new technology to make our lives better, what would it be?

RC: Paul Virilio once said that the invention of any new technology is also the invention of a new accident. With the last few leaps in technology, it seems like the accidents are winning. The net effects are bad. I’m thinking about cars, our dominant energy sources, social media, and smartphones. The jury’s back: These things are not good.

I would like to come up with something to soothe our uncertainty, quell our anxieties, and let us connect to each other again without all of the bad stuff.

Spike Jonze making marks in the invisible city, as seen in The Medium Picture. Photo by Rodger Bridges.

Spike Jonze making marks in the invisible city, as seen in The Medium Picture. Photo by Rodger Bridges. CD: How do the subcultures of skateboarding and music explain our relationship with technology?

RC: Skateboarding is a generative way to see the world. Skateboarders repurpose the built environment in ways it wasn’t intended to be used, mining affordances from stairs, ledges, rails, pools, curbs, and anything else that others might see as an obstacle.

The recording and playback of music have gone through epochal changes in my lifetime, from albums, cassettes, and CDs to CDRs, MP3s, and streaming. Each one has also changed the music industry in irrevocable ways. There’s a lesson in every one.

UNF Communication Mention

UNF Communication MentionThe Medium Picture got a mention on the University of Florida School of Communication’s Instagram. Along with the picture above, they wrote,

If you’re looking for a new read, check out The Medium Picture by Dr. Roy Christopher, a #UNFComm professor. His latest book is part memoir exploring his perspective on media theory, using the subdisciplines of media ecology and media archaeology. He also incorporates cultural and musical influences from his life. As you flip through pages, Dr. Christopher examines how industries continue to mediate our world with technology.

Thanks to Angela Spears, Haley D’Alessio, and UNF’s School of Communication social-media team!

Tails of Skateboarding’s Skate Book Club

Tails of Skateboarding’s Skate Book ClubTails of Skateboarding is one of my favorite publications, and their Skate Book Club newsletter is an awesome resource for the readerly skateboarder. I’m proud to have The Medium Picture mentioned in the first-anniversary issue!

Thanks to Craig Douglas for the interview and his continued support, to the UNF School of Communication’s social-media team, and John Freeborn at Tails of Skateboarding.

And thanks to you for reading,

-royc.

October 30, 2025

Half-Off Halloween Sale!

If you don’t have The Medium Picture yet, now is the time!

This is just a quick note to let you know that the University of Georgia Press is having a half-off Halloween sale on all of their fine books including my own recently released The Medium Picture! Just order from the UGA Press website, and use code “Spooky50” before Halloween is over at the end of the week.

If you thought it was pricey or you just haven’t ordered yet, don’t miss this deal!

Your regular newsletter will return soon.

Thank you for your continued support,

-royc.

October 15, 2025

THE MEDIUM PICTURE Cover Story

My new book, The Medium Picture, is out today from the University of Georgia Press! To celebrate, here is the photo essay I compiled chronicling how the cover object and image came together.

Many thanks to everyone who preordered this book. You should be getting your copies today! If you haven’t ordered one, it’s available everywhere now!

An Eternal Golden Braid

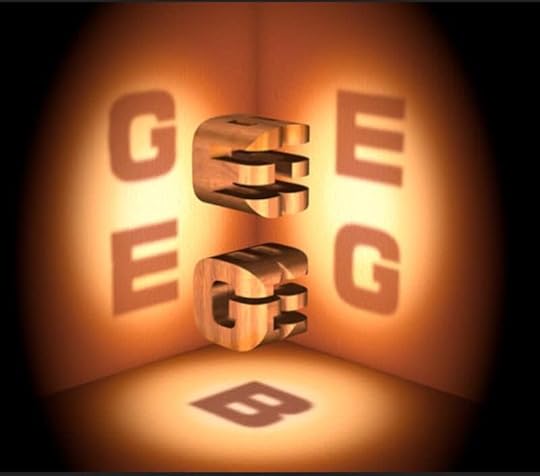

An Eternal Golden BraidReleased in 1979, Douglas Hofstadter's first book, the Pulitzer-Prize winning Gödel, Escher, Bach: An Eternal Golden Braid, is an expansive volume that explores how living things come to be from nonliving things. It's about self-reference and emergence and creation and lots of other things. It's well worth checking out.

For the cover of his heady tome, Hofstadter carved two wood-block objects such that their shadows would cast the book's initials when lit against a flat backdrop. He went the extra step of working in the initials for the subtitle as well.

Earlier this year, I was inspired to emulate Hofstadter's sculpture. I found a way to put the initials for my media-theory book-in-progress, The Medium Picture—TMP—into a similar configuration. This is one of my early sketches.

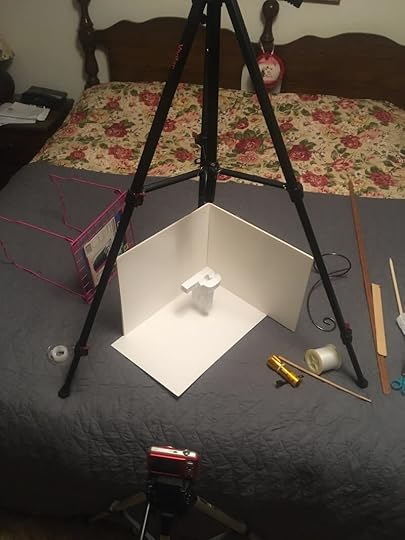

The sketches I did at least made the thing appear possible, so I started exploring physical options. After trying different materials and digging around craft stores, I finally found some letters that were about the right shape and would save me a lot of time toward the final object.

I was fortunate to find letters with similar proportions to the ones I'd been drawing. The first thing was to cut the M to make the P the top of the T. Like so:

Then I taped the pieces together.

And after some cutting, shaping, papier-mâché tweaking, calk to round the leg of the M…

…and a coat of white paint, the object was ready to test.

Now that it physically existed, I knew the real test would be hanging it, lighting it, and capturing its shadows correctly. I built a contraption for just that out of things found around my parents' house.

It was as sketchy as it looks. The object was suspended with two pieces of fishing line, and I had to turn off the air conditioning to get the thing to hang still for the picture. I found some pieces of foamcore in my sister’s old closet for the backdrop and gathered up tiny flashlights from all over the house.

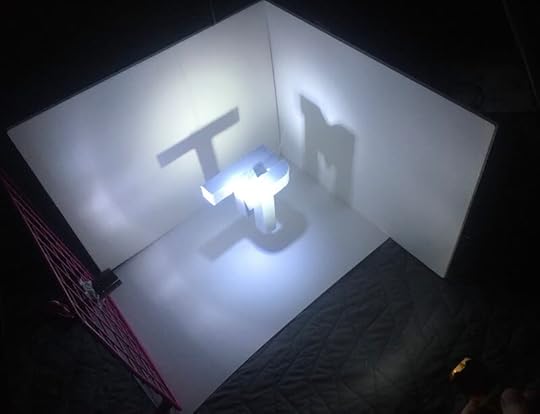

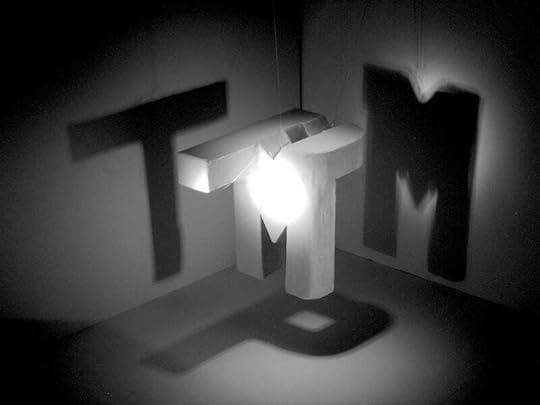

With the LED flashlights propped and taped in place, this is the final set-up.

And this is the final shot. It’s not quite as intricate or as elegant as Hofstadter’s, but I’m pretty stoked on it.

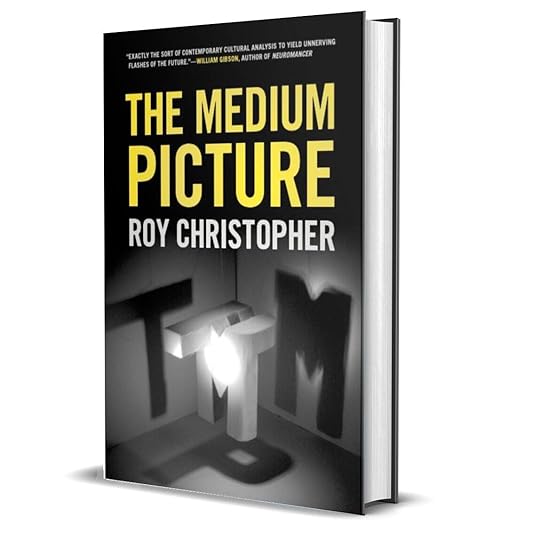

This is the final cover, designed by Erin Kirk.

I belabored this process here because about half the people who see the final image ask me what software I used to make it. I know this could've been done digitally in any 3-D imaging suite, but I wanted to make it for real, just as Douglas Hofstadter had done. I think it makes a striking cover image and a fitting tribute to his work.

The Medium Picture is out today from the University of Georgia Press!

Thank you for reading, responding, and sharing,

-royc.

September 30, 2025

To Seek Whence Cometh a Sequence

I recently got an email celebrating the 21st anniversary of my long-abandoned LiveJournal account. I looked back at my six entries from 2002 and found the seeds of my book The Medium Picture: early books I read on media theory, a note on Brian Eno’s edge culture, the claustrophobia I felt from working on computer screens.

One of my many mappings of The Medium Picture, March 2020.

One of my many mappings of The Medium Picture, March 2020.The Medium Picture was supposed to be my first book. I started outlining it in 2001, worked with an agent for a while, and—after a decade of research and revision—I originally signed a contract for it with Zer0 Books in 2011. The book then went through several publishing shuffles (as did the publisher), during which I went on to finish several other projects. I worked on it off and on in the meantime and am happy to finally have it out of my head and into your hands in two weeks.

In what follows I trace a few of the writers who influenced me along the way to this book’s publication. This stuff doesn’t come from nowhere after all.

As you know, I started writing as a byproduct of making zines. I’d been writing before that, but making zines reframed the practice for me. The layouts originally attracted me to the zine format. I found the juxtaposition of words, images, and drawings on the page endlessly interesting as a fifteen-year old, but if my friends and I wanted a story written or a review of something, we had to write it. That’s where, as I often say, I learned to turn events and interviews into pages with staples.

The Master Cluster (l to r): Andy Jenkins, Spike Jonze, and Mark Lewman. Photo by Spike.

The Master Cluster (l to r): Andy Jenkins, Spike Jonze, and Mark Lewman. Photo by Spike.At some point in my early BMX and skateboarding days, my admiration and ambition pivoted from the riders and skateboarders on the pages of the magazines to the writers and editors of those pages. The main ones being Andy Jenkins, Spike Jonze, and Mark Lewman. Not only did they run the magazines I wanted to be a part of (e.g., Freestylin’, Go, Homeboy, Dirt, Grand Royal), but when I started making zines, theirs were the high watermark. Andy’s Bend, Spike’s Stapled and Xeroxed Paper, and Lew’s Chariot of the Ninja were annexes and extensions of who they were in the magazines. I’ve stayed in touch with them off and on over the years, and they’ve taught me many, many things, but the main one is that you don’t need permission to do something great. Anything is possible.

Regrettably, I was not always a big reader. I mean I read a lot as a kid, but school sucked most of the fun out of it. The book that brought me back to reading was Chaos: Making a New Science by James Gleick. As I told Gino Sorcinelli at Bookshelf Beats, reading Chaos was a hairpin turn to a new direction for me. My shift in mindset not only included regular reading and going back to school, but also running a website about the new ideas I was learning. When I switched from making ‘zines about skateboarding, BMX, and music to making websites about new science and new media, Gleick was one of the first people I contacted. I didn't know it until years later, but he’d just gone through a horrendous plane crash and much personal loss. The first email I got from Jim was from his hospital bed at NYU’s Rusk Institute of Rehabilitation Medicine. Hearing back from him was another push on my new path.

Not long after that I found Media Virus! by Douglas Rushkoff, and my new direction became even clearer. Like Gleick, Rushkoff’s mix of smarts and readability, as well as his continued support, have kept me inspired and motivated. Somewhere in there a friend of mine recommended Steven Johnson’s Interface Culture. Like Chaos and Media Virus!, that book became a major touchstone for my thinking and its author a major influence on my writing.

Further along if not further afield, among many other writers, critics, and theorists, I found Steven Shaviro, Mark Dery, Erik Davis, Tricia Rose, Rebecca Solnit, Dave Tompkins, Kodwo Eshun, and Mark Fisher, all of whom employ music, movies, and other media in their theory and criticism. Having come from music, I found their approaches appealing, and I could comfortably see myself following them in ways I hadn’t felt with a lot of other writers I was reading. I’m still at it.

The Medium Picture: cover design by Erin Kirk; object and image by me.

The Medium Picture: cover design by Erin Kirk; object and image by me.In the preface to The Medium Picture I write that if I were to follow through with the book’s cover image, inspired by Douglas Hofstadter’s Pulitzer Prize-winning first book, Gödel, Escher, Bach, and name TMP after the three people who shaped it, it would be called Gibson, Eno, McLuhan.

William Gibson’s thought hangs heavy over a lot of my work. Nearly every time I come up with a way to theorize and think about the process of technological mediation or cultural evolution, I find Gibson got there first. His novels and essays are subtle sources of the nuances of the now, a wealth of ways to think about how we currently live with our world.

Brian Eno’s thinking on music and media is both vast and deep, and I’ve been yammering about his idea of edge culture for years. Outlined briefly in his 1996 memoir, A Year with Swollen Appendices, it has shaped my thinking in many ways. He kindly granted me permission to explore and expand on it further in TMP. I can only hope I did his thought and gesture justice.

Anyone who tries to do what I attempt to do has to contend with Marshall McLuhan, whose name and thought you might recognize from past posts and writings. If you want to study media and mediation, he’s the starting point. Ignore him at your peril.

A list like this can never be complete (I’ve already started a second part to this post), but with The Medium Picture finally coming out in two weeks (!!!), I wanted to try to retrace some of my steps — especially given how long I’ve been working on it.

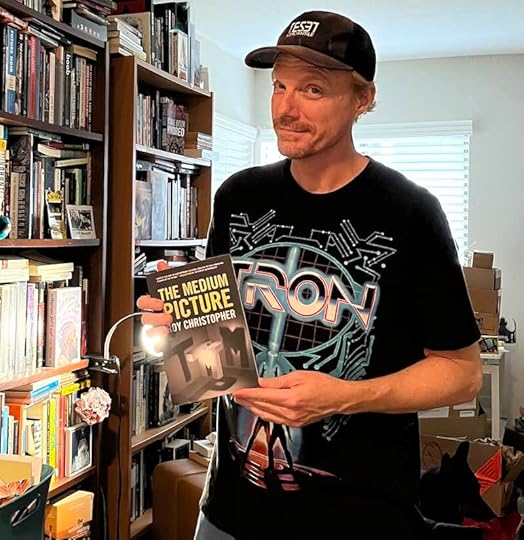

Your humble author holding the book.The Medium Picture exists!

Your humble author holding the book.The Medium Picture exists!Speaking of, I just got my author copies! It really is a beautiful book. I worked so hard on it for a so long, and I’m very proud of how it came out. Many thanks to Nathaniel Holly, Mick Gusinde-duffy, Candice Lawrence, Bethany Snead, Jon Davies, Chris Dodge, Erin Kirk, and all at the University of Georgia Press for taking a chance on this book, taking the time and care, and making it look so great. I can’t wait for everyone to see it!

The Medium Picture comes out on October 15th! Preorder yours now!

Thank you for reading and preordering,

-royc.

* Apologies to Douglas Hofstadter from whom I stole the title of this post. It’s the name of Chapter One in his brilliant 1995 book Fluid Concepts and Creative Analogies.

September 15, 2025

The World Forgetting by the World Forgot

Do you remember the last time you heard some good news? If you can’t, there are a few reasons — beyond the fact that there hasn’t been any in more than a minute. As news organizations found out a long time ago, it’s far more lucrative to feed you bad news, to make you resent, rage, and most importantly, react. This is compounded by the fact that it’s also difficult to remember any kind of news anymore. It’s a conspiracy between your media and your mind.

We see everything in two dimensions.

We see everything in two dimensions.One of the definitive aspects of the media spectacle is its lack of any sense of memory. As McKenzie Wark tells me, “As Guy Debord used to argue, the triumph of the spectacle is in the defeat of history and the installation of ‘spectacular time’, which is purely cyclical.”1 In his 1967 book Society of the Spectacle, Debord wrote,

The lack of general historical life also means that individual life as yet has no history. The pseudo-events that vie for attention in spectacular dramatisations have not been lived by those who are informed about them; and in any case they are soon forgotten due to their increasingly frenetic replacement at every pulsation of the spectacular machinery.2

As our experience is more and more mediated and less lived through, the spectacle functions to make us passive observers rather than active participants. It diminishes the idea of memory by reducing lived moments to their image, removing us from our selves and any genuine connection to our world. Now we have bespoke spectacles, individualized, each to their own churn. We exist in an isolated simultaneity, not quite solipsistic, yet fully mediated.

“Whatever was true now was true from everlasting to everlasting. It was quite simple. All that was needed was an unending series of victories over your own memory.” — from George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four

If life in Debord’s spectacle sounds awful, it was supposed to, but these days the idea of not remembering sounds better than the brutality of the everyday. Call the remedy tactical forgetting or strategic amnesia. Illuminating the idea in Octavia E. Butler’s Parable of the Talents (Seven Stories Press, 1998), Shari Evans writes, “Strategic amnesia gives us the critical distance to remember ethically rather than vengefully. This strategic amnesia in which Butler’s last novel situates us, then, leads, past forgetting, to the justice of remembering on a historic and cultural scale.”3 Justice, as much as it might be as a human as invention as history, matters. If any of this matters, it does.

Tom Wilkinson, Jim Carrey, and Mark Ruffalo in Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind (2004).

Tom Wilkinson, Jim Carrey, and Mark Ruffalo in Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind (2004).If only it were so easy for us as individuals to forget and remember on command. The world would look very different if we could. In the 2004 film Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind, screenwriter Charlie Kaufman and director Michel Gondry go to such great lengths to show that not only is it not easy, it’s not possible. In the movie, a medical firm called Lacuna offers a surgical procedure that removes painful memories from an individual’s brain. In this case, painful memories of a lost love, but one can imagine removing unwanted memories of traumatic events of any kind.

Conversely, sometimes memory is latent in the environment, just waiting to be activated. Have you ever learned a new word and then started seeing it everywhere? The literary theorist Kenneth Burke attributed this to what he called terministic screens.4 Burke would say that the word was always there, but you were filtering it out, obscuring it with ignorance. Once it became a part of your terministic screen, only then did you start seeing it. But you can’t unsee it once it’s a part of the screen you use to filter reality. Once you learn something new, you’re stuck with it.

Herbert Bayer, Diagram of the Field of Vision, 1930.

Herbert Bayer, Diagram of the Field of Vision, 1930.So, we can’t forget on command or remember at will, but our minds filter out and fill in all kinds of words and details and facts every day. As the author Grace Paley once said, “Any story told twice is fiction.”5 In a speech at BAFTA in 2011, Charlie Kaufman says, “If you consider a traumatic event in your life, consider it as you experienced it. Now think about how you told it to someone a year later. Now think about how you told it for the one hundredth time. It’s not the same thing.” One thing that intervenes, he says, is perspective, which we tend to think of as a good thing. “The problem is that this perspective is a misrepresentation of the incident; it’s a reconstruction with meaning and as such bears very little resemblance to the event.” He continues,

The other thing that happens in storytelling is the process of adjustment for the audience over time. You find out which part of the story works, which parts to embellish, which parts to jettison. You fashion it. Your goal, your reasons for telling it are to be entertaining, to garner sympathy. This is true for a story told at a dinner party, and it’s true for stories told in movies.

Sometimes we change the story inadvertently, and sometimes we do it as a matter of survival.

To survive,

Know the past.

Let it touch you.

Then let

The past

Go.

— from “Earthseed: The Book of the Living” by Lauren Oya Olamina

in Octavia E. Butler’s Parable of the Talents

Moreover, our collective memory, and especially our mediated memory (or communicative memory6), suit their own needs, sanity for the former, capital for the latter, selectively remembering and revising as they go. In “The ‘Yizkor’ Book of 1911 - A Note on National Myths in the Second Aliyah.” Jonathan Frankel writes:

Legends and national myths — which so enchant the group’s psyche, the collective subconscious — have become a source of inspiration to the faith and devotion which these imported ideologies [modern nationalism, socialism] could foster only partially and through constant adaptation.7

We watch this constant adaptation as short-scale history scrolls by in our daily diet of genocide, racism, gun violence, domestic terrorism, the global degradation of democracy, climate catastrophe, culture wars, and cat videos. History at any scale is always already a construct that cannot include all of the minutia of humankind, so the writers, editors, and adapters of that history choose to emphasize some things and leave other things out. If we ever want to break out of our now-individualized spectacle, and if we ever want any semblance of history or of justice, we need to care more about those decisions and who makes them for us.8

Only 30 More Days!

Only 30 More Days!Only one month left until The Medium Picture comes out from the University of Georgia Press! If you think you might buy a copy, please consider preordering it. You can still make a huge difference in the launch and life of the book. Thank you!

Advance praise for The Medium Picture:

“Like a skateboarder repurposing the utilitarian textures of the urban terrain for sport, Roy Christopher reclaims the content and technologies of the media environment as a landscape to be navigated and explored. The Medium Picture is both a highly personal yet revelatory chronicle of a decades-long encounter with mediated popular culture.” — Douglas Rushkoff

“A synthesis of theory and thesis, research and personal recollection, The Medium Picture is a work of rangy intelligence and wandering curiosity. Thought-provoking and a pleasure to read.” — Charles Yu

Preorder yours now! Thank you!

POST-SELF is Up Next!

POST-SELF is Up Next!My book-after-next, Post-Self: Journeys Beyond the Human Body, comes out from Repeater Books on December 2nd! This new expanded and revised edition of Escape Philosophy includes updates throughout, a new Foreword by Mark Dery (“Welcome to the Misanthropocene”), and a new Afterword by me! I just got a few copies, so if you’re an influencer or work for some giant media outlet, let me know if you want to spread the disdain.

Advance praise for Post-Self:

“Using Godflesh—the arch-wizards of industrial metal—as a framework for a deep philosophical inspection of the permeable human form reveals that all our critical theory should begin on the street where wasted teen musicians pummel their mind and instruments into culture-shifting fault lines. Godflesh are not just a ‘mirror’ of all the horrors and glories we can inflict on our bodies, but a blasted soundscape of our moans. Roy Christopher’s book is a thought-provoking and delightful crucible of film, music, and the best kind of speculative thought.” — Peter Bebergal, author, Season of the Witch

“Too often philosophy gets bogged down in the tedious ‘working-through’ of contingency and finitude. Post-Self takes a different approach, engaging with cultural forms of refusal, denial, and negation in all their glorious ambivalence.”

— Eugene Thacker

Preorder yours now! Thank you!

Thanks for reading and preordering! It really means a lot to me.

-royc.

1Quoted in Roy Christopher, “McKenzie Wark: To the Vector the Spoils,” in Roy Christopher (ed.), Follow for Now: Interviews with Friends and Heroes (pp. 131-136), Seattle, WA: Well-Red Bear, 2007, 134.

2Guy Debord, Society of the Spectacle, Detroit, MI: Red & Black, 1970, 90.

3Shari Evans, “From ‘Hierarchical Behavior’ to Strategic Amnesia: Structures of Memory and Forgetting in Octavia Bulter’s Fledgling,” in Rebecca J. Holden & Nisi Shawl (eds.), Strange Matings: Science Fiction, Feminism, African American Voices, and Octavia E. Butler (237-262), Seattle, WA: Aqueduct Press, 2013, 256; See also adrienne maree brown, Emergent Strategy: Shaping Change, Changing Worlds, Chico, CA: AK Press, 2017.

4Kenneth Burke, Language as Symbolic Action, Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1966, 45.

5Quoted in Jacqueline Taylor, Grace Paley: Illuminating the Dark Lives, Austin, TX: University of Texas Press, 1990.

6I particularly like this term; See Jan Assmann & John Czaplicka, “Collective Memory and Cultural Identity,” New German Critique, Spring - Summer, 1995, No. 65, pp. 125-133.

7Yahadut Zemanenu 4 (1987): 67-96 (in Hebrew).

8The title of this post and the title of Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind both come from Alexander Pope’s poem “Eloisa to Abelard” (1717).

September 1, 2025

Capitalist Surrealism

McKenzie Wark opens her book Capital is Dead: Is This Something Worse? (Verso, 2019) with an epigraph from Kathy Acker: “Post-capitalists’ general strategy right now is to render language (all that which signifies) abstract therefore easily manipulable.”1 Acker goes on, in her book, Literal Madness,

In the case of language and of economy the signified and the actual objects have no value don’t exist or else have only whatever values those who control the signifiers assign them. Language is making me sick. Unless I destroy the relations between language and their signifieds that is their control.2

Wark argues that we’ve moved beyond capitalism to something worse, where the Marxist means of production and the housing of our bodies are no longer relevant. Information, which often manifests itself in language, is the currency in play.

Cover design by Palais Sinclaire.

Cover design by Palais Sinclaire.Circling the same, in Exocapilatism: Economies With Absolutely No Limits (Becoming Press, 2025), Marek Poliks and Roberto Alonso Trillo turn what Nick Land calls “techno-capital” all the way up. Simultaneously echoing Wark, they write that exocapitalism exists as software: pure information. Information as such may want to be free, but it never is. As our friend Charles Mudede writes in his introduction, “Capitalism has never been and could never be a smooth criminal. It needs the hold, the friction, the instability to generate surplus value.”3 Poliks and Trillo start from the idea that there is not one, monolithic capitalism, but many capitalisms operating at many scales. Exocapitalism is smaller and more pervasive than diatoms or DNA, yet bigger and more expansive than Cassiopeia and the Capitalocene.4

So, is it a Mortonian hyperobject: a recently visible entity, always already too large for us to comprehend?5 Or is it as Dr. Alvin Z. Markov puts it in Land’s “Cyberrevolution,” like an organism, “but an organism that’s evolved much too fast to develop a reliable immune system…”6—like a selfish meme, a virus running roughshod through systems and scales with senseless abandon, an abject object with an excess of access?

“Nothing is more dangerous than a monster whose story is ignored.” — Annalee Newitz, Pretend We’re Dead

For Poliks and Trillo, it’s all of the above and beyond, beyond the anti-Oedipal schizoanalysis of Deleuze and Guattari, beyond Wark, Acker, and Land. Exocapitalism is monstrous, autonomous, invisible, inescapable, unpredictable. Mudede adds, “An efficient market hypothesis is nothing more than the chattering that zombies make with their teeth.”7

In his classic free-market, Marxist polemic, Capitalist Realism (Zer0 Books, 2009), Mark Fisher described capitalism as acting “very much like the Thing in John Carpenter’s film of the same name: a monstrous, infinitely plastic entity, capable of metabolizing and absorbing anything with which it comes into contact.”8 In their book Pretend We’re Dead (Duke University Press, 2006), Annalee Newitz writes, “capitalism creates monsters who want to kill you,”9 monsters lurking in the liminal, what Lacan called “the big Other,” a market economy in an Area-X ecology. As the big Other, exocapitalism is an invisible monster of which we only see traces, shadows, and stand-ins, ever-evident in its absence.

“I don’t trust the system, but I do trust the process,

Like I trust the water, but not the monster of Loch Ness.

Because what the system withholds, the process will tell you,

And what the water supplies, the monster will sell you.”

— WNGWLKR, “A Congregation of Jackals”

Acker wrote, “Since the only reality of phenomena is symbolic, the world’s most controllable by those who can best manipulate these symbolic relations. Semiotics is a useful model to the post-capitalists.”10 Fisher described late capitalism’s pace of “dreaming up and junking of social fictions is nearly as rapid as its production and disposal of commodities.” This monster eats everything… everything.11

Illustration by Avocado Ibuprofen.

Illustration by Avocado Ibuprofen.We can fix it though, as Fisher facetiously argued, “All we have to do is buy the right products.” If exocapitalism is only visible by its recent absence—by what it didn’t leave behind ( middle class )—then we need to pay closer attention to its appetite(s) and be more careful about what we feed it.

It. Eats. Everything.

“Products are out of date. No one can afford to buy anyway." — Kathy Acker, Hannibal Lector, My Father

One blurber calls Poliks and Trillo’s Excocapitalism “Nick Land for adults.”12 The reason is evident, even if only in the following: Relegating the user to the used, Land (in)famously asked, “Can what is playing you make it to level 2?”13 If it’s going to have a chance, then Exocapitalism is its survival guide, chock full of cheat codes, tips, trips, token stacks, stock symbols, amalgams, algorithms, and antagonisms.

Preorder These, Please!

Preorder These, Please!Speaking of, I have two books coming out before the end of the year: The Medium Picture comes out from the University of Georgia Press on October 15th, and Post-Self: Journeys Beyond the Human Body comes out from Repeater Books on December 2nd! If you think you might buy one of these (or both!), please consider preordering them. It makes a huge difference in the launch and life of the book. Thank you!

Advance praise for The Medium Picture:

Exactly the sort of contemporary cultural analysis to yield unnerving flashes of the future. — William Gibson

Brilliant, pathbreaking, palpable insights… Worthy of McLuhan. — Paul Levinson

Advance praise for Post-Self:

Too often philosophy gets bogged down in the tedious ‘working-through’ of contingency and finitude. Post-Self takes a different approach, engaging with cultural forms of refusal, denial, and negation in all their glorious ambivalence.

— Eugene Thacker

A peculiar hybrid of Thomas Ligotti and Marshall McLuhan. — Robert Guffey

Thanks for reading and preordering!

-royc.

1Quoted in McKenzie Wark, Capital is Dead: Is This Something Worse? New York: Verso, 2019, 1.

2Kathy Acker, Literal Madness: My Life, My Death by Pier Paolo Passolini; Kathy Goes to Haiti; Florida, New York: Grove Press, 1989, 301.

3Charles Mudede, “Foreword: The Political Economy of Software,” in Marek Poliks and Roberto Alonso Trillo, Exocapitalsim: Economies With Absolutely No Limits, Berlin/Nicosia: Becoming Press, 2025, 2.

4See Jason W. Moore (ed.), Anthropocene or Capitalocene? Nature, History, and the Crisis of Capitalism, Oakland, CA: PM Press, 2016.

5Timothy Morton, Hyperobjects: Philosophy and Ecology after the End of the World, Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 2013, passim.

6Nick Land, Fanged Noumena: Collected Writings, 1987-2007, Urbanomic/Sequence Press, 2011, 377.

7Mudede, 2025, 2-3.

8Mark Fisher, Capitalist Realism: Is There No Alternative? London: Zer0 Books, 2009, 6.

9Annalee Newitz, Pretend We’re Dead: Capitalist Monsters in American Pop Culture, Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2006, 3.

10Acker, 1989, 293.

11See, for instance, Nancy Fraser, Cannibal Capitalism, New York: Verso, 2023.

12“A masterpiece… Nick Land for Adults!” — Onty

13Nick Land, “Swarm 1: Meltdown,” ccru, 1994.

July 29, 2025

A Clockwork Kubrick

My mom, a lifelong artist and crafter, chronically has unfinished projects in various places around her house: a painting on an easel, a pattern pinned to some odd-shaped fabric, quilt squares pieced but apart, a half-repainted hobby horse. Once she can visualize the finished product, she all but loses interest in finishing it. I can relate to that feeling with my writing. I often approach with a question I want to answer or a curiosity that hasn’t found its end. Once I have an answer, my interest wanes.

Kubrick and his camera.

Kubrick and his camera.Master filmmaker Stanley Kubrick once said, “You start something because you are interested in it, but you actually do it to find out about it.”1 Once you find out about it, there’s usually still work to do. Creation is its own reward, but you could discover the best thing in a category or a new category altogether. If no one knows, it won’t matter. Follow through and spread the word or you’re depriving the world of your work.2 Sometimes we don’t even know what we’ve created until we share it. Kubrick added at another time, “The truth of a thing is in the feel of it, not the think of it.”

Screenwriter Joseph Mankiewicz used to say that a well-written script had already been directed. That is, if it’s put on the page properly, there isn’t much for actors or directors to improve upon. According his Eyes Wide Shut cowriter Frederic Raphael, that’s not the kind of script Kubrick ever wanted. And actor Malcolm McDowell, who played Alex the droog in Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange (1971), said that Kubrick never knew what he wanted, but he knew what he didn’t.

“To restrain man is not to redeem him.” — Stanley Kubrick

He knew it when he saw it though. I am fond of saying that as long as one keeps their options open, options is all one will have. It’s okay to let them breathe though. Raphael wrote of Kubrick, “Kubrick was not indecisive; he was postponing a decision, which is by no means the same thing.”3 Postponing a decision can be action in itself, but a decision must be made. As the song goes, “if you choose not to decide, you still have made a choice.”4

D. Harlan Wilson’s

Strangelove Country

. Cover design by Matthew Revert.

D. Harlan Wilson’s

Strangelove Country

. Cover design by Matthew Revert.In his book, Strangelove Country: Science Fiction, Filmosophy, and the Kubrickian Consciousness (Stalking Horse Press, 2025), D. Harlan Wilson deploys several critical constructs in order to investigate Kubrick’s forays into science fiction. Never a fan of the genre, Kubrick nonetheless made four films that are either squarely science fiction or more sci-fi than they are anything else: Dr. Strangelove (1964), 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), A Clockwork Orange (1971), and the posthumous A.I. Artificial Intelligence (2001). At least one of them—2001—outright redefined the genre, which was kid’s stuff prior to his sprawling opus.

“In all things mysterious—never explain.” — H.P. Lovecraft

And redefining science fiction is more and more difficult since, given the increasingly sci-fi reality we live in. Wilson writes,

Our media encourages us to view ourselves as characters to be viewed by other characters in a filmic realm whose social networks remake the self, identity, reality, and community. A manifestation of weaponized desire, cinematic thinking allows us to exist in our own highly mediatized diegesis.

We’ve been living as if—as if there’s an audience watching—for so long now that it’s difficult to imagine otherwise. Try it though. Post less. Save more for yourself. As Raphael wrote of Kubrick, “He is morbidly afraid of giving away his secrets, the best of which may be that he has none.” You don’t have to have a secret to act like you do. That’s a secret unto itself. Mystery loves company.

Different Waves, Different Depths

Different Waves, Different DepthsI tried my pen at some science fiction myself. Different Waves, Different Depths (Impeller Press) is my collection of nine stories, varying in style from the literarily weird to the science fiction and in length from the flash to the novella. There are time loops and time travel, reality television and big data, consultants who can make anyone a winner, a newspaper that’s just gone online-only, a band that never existed but is all too real, mistaken identities, roadtrips, drugs, guns, murder, and a love story or three. Check it out!

Taking a BreakIn the spirit of that last bit about Kubrick, I’m taking a break from social media for the month of August, and that includes this newsletter. I’m not mad or anything, I just want to get off the internet treadmill for a bit. I’ll still be available via email (would that we could ditch email for a month!), and I’ll be back on here in September. Enjoy your selves.

And as always, thank you for reading,

-royc.

P.S. Preorder The Medium Picture ! Thank you!

1Quoted in Alison Castle (ed.), The Stanley Kubrick Archives, Cologne, Germany: Taschen, 2008.

2I stole this last sentiment from my friend Howard Bloom.

3Quoted in Filippo Ulivieri, Cracking the Kube: Solving the Mysteries of Stanley Kubrick Through Archival Research, self-published, 2024.

4Rush, “Free Will” on Permanent Waves [LP], New York: Mercury Records.

July 22, 2025

Unwavering Radiant: Keith Haring

One election day when I lived in Chicago, I walked over to the school by my house to vote. On my way to the converted classroom that served as the polls, I was stunned stupid by a hallway-long Keith Haring mural. The vibrant colors and simple characters are impossible to mistake for anyone else’s work. Haring is one of my all-time favorite artists, and I had no idea that one of his last murals was only a few blocks from my house. During my undergraduate studies, my last big paper in English Composition 102 was a biography of Haring. He passed away as I was writing it.

Keith Haring mural at the William H. Wells Community Academy High School in Chicago, completed in November 1989. Panoramic photo by me.

Keith Haring mural at the William H. Wells Community Academy High School in Chicago, completed in November 1989. Panoramic photo by me.As an advocate and an artist, Haring occupied a unique place in the world. He skirted the aesthetics of typical graffiti by drawing thick-lined stick-figure characters and animals dancing and moving, the lines as flexible as their fancies. “Haring demonstrated that one could create art on the street that differed from the more pervasive lettering-based graffiti,” writes my friend and Obey Giant artist Shepard Fairey in the Foreword to Haring’s Journals. “He also showed me that the same artists could not only affect people on the streets, they could also put their art on T-shirts and record covers, as well as have their work respected, displayed, and sold as fine art.” Whereas most graffiti looks like graffiti—that is, it embodies its own aesthetic, much in the way tattoos do—Haring’s was more whimsical, like children’s hieroglyphs, if the children understood the many facets of line, its limits, and its capacity to communicate.

“Your line is your personality.” — Keith Haring

We love to hear the story about how artists live and worry. Graffiti proper, in the modern sense of the term, started in the late 1960s in New York City when a kid from the Washington Heights section of Manhattan known as Taki 183 (“Taki” being his tag name and “183” being the street he lived on) emblazoned his tag all over NYC. He worked as a messenger and traveled all five boroughs via the subways. As such, he was the first “All-City” tagger. Impressed by his ubiquity and subsequent notoriety, many kids followed and graffiti eventually became a widespread renegade art form. Aerosol artists embellished their names with colors, arrows, 3-D effects and wild lettering styles.

By the mid-to-late 1970s, New York—especially its subway system—was covered with brightly colored murals with not only tag names, but holiday messages, anti establishment slogans and full-on art works known as “pieces” (short for “masterpieces”). The world of graffiti preceded the rest of hip-hop culture, but became an integral part during hip hop’s early-1980s boom, joining breakdancing, emceeing and DJing as hip-hop’s four elements.

After filling fifty bags with garbage, cleaning up the three-foot-high garbage piles obscuring an abandoned handball wall on the corner of East Houston Street and the Bowery in the East Village, Haring and his partner, Juan Dubose, painted a giant mural of his signature figures breakdancing, running, and spinning in bold, fluorescent colors. Like many other graffiti artists replacing the drab city walls and boring metal subway trains with greetings and flashy colors, Haring saw himself as doing a service to the city. City officials and stuffy citizens hardly agreed. Massive anti-graffiti campaigns grew right along with the art form itself and are still in effect today in most major metropolitan areas. These specialized anti-graffiti forces only added to the art form’s already outlawed status. The ability to pull off a hype piece under such increasing pressure only made great writers more revered for their skills.

Haring started his public-art practice using chalk on empty ad panels in the New York subway stations. In spaces usually reserved for advertising, Haring drew alien abductions, mushroom clouds, radiant babies, barking dogs, televisions, and people, people, people. Between 1980 and 1985, he sometimes produced upward of forty drawings a day. This practice eventually gave way to murals and other more colorful paintings. His simple designs, characters, and animals caught on, even with a graffiti-weary public, leading to gallery shows and commercial work.

“Keith in the subway” (CC BY-NC 2.0) Ken Lig / JUST SHOOT IT! Photography

“Keith in the subway” (CC BY-NC 2.0) Ken Lig / JUST SHOOT IT! PhotographyIn spite of criticisms about the latter, his art never lacked bite. His images pushed back against everything from apartheid in South Africa and the threat of nuclear weapons, to the epidemics of crack and AIDS. These works appeared not only in chalk on black paper ad blocks but printed on posters, wheat-pasted on poles, and buttons on the lapels of friends and strangers. So prolific was his artistic protest and promotion that he drew the envy of no less a contemporary than Andy Warhol. “He was jealous of how Keith was like an advertising agency unto himself,” said the photographer Christopher Makos. “That was the cleverest thing any artist at the moment was doing.”

Companies develop—or hire other companies to develop—brand identities and campaigns. Logos, slogans, and thematic series of ads combine to sell products, brand recognition, and brand loyalty. Like the best branding, graffiti tags have to be catchy, and they have to have good letters or great characters. Graffiti and its corporate sanctioned sister art, advertising, are our modern day cave paintings. As Marshall McLuhan put it, “ads are not intended to be seen but to produce an effect. The cave paintings were carefully hidden. They were a magic form, intended to affect events at a distance.”

The artist Yasiin Bey once called hip-hop a folk art. It’s art by the people, for the people, and provides some use outside of mere decoration. “Art is nothing if you don’t reach every segment of the people,” Haring once said. “The performative nature of drawing for him was very important,” said his dealer Tony Shafrazi, describing a scene where Haring had run into a group of young people at a coffeeshop and drew pictures and gave them away. “That form of producing and giving was beyond any form of management. He had to let it flow. He couldn’t limit it.” Haring wrote the following in his journal on March 18, 1982:

My contribution to the world is my ability to draw. I will draw as much as I can for as many people for as long as I can. Drawing is still basically the same as it has been since prehistoric times. It brings together man and the world. It lives through magic.

Keith Haring passed away on February 16, 1990 due to complications from AIDS, yet his work is more widespread now and as recognizable as ever, still celebrating simple, innocent notions like spontaneity, generosity, and a love of humanity. As I mentioned above, I was writing an English Composition paper about him when he died, but I currently have a pair of socks with his drawings on them. His work is timeless.

And traditional graffiti still thrives in cities and along major train lines. It has survived as what the punk-intellectual Jello Biafra once called “the last bastion of free speech,” and the yippie Abbie Hoffman called it “one of the best forms of free communication.” Anyone can grab a can of spray paint, a fat marker, or some chalk and make their thoughts known to the passing population. You can buff graffiti, you can paint over it and you can arrest its practitioners, but as long as someone feels that their voice isn’t being heard, you can’t make it go away.

Word to the ThirdThis piece is the third of a loose trilogy including Escape from New York (regarding my own discovery of hip-hop) and From Blackout to Breakout (about the New York blackout of 1977). A few bits of it also appear in my book Dead Precedents: How Hip-hop Defines the Future (Repeater Books, 2019). If you don’t know, now you know.

I’ve been reading Brad Gooch’s wonderful book, Radiant: The Life and Line of Keith Haring (Harper, 2024), and if you’re interested in Keith Haring and the nexus of creativity and culture that was New York City in the late 1970s and early 1980s, there are far worse places to start.

Thank you for reading, responding, subscribing, and sharing,

-royc.

July 13, 2025

From Blackout to Breakout

Of all the technologies we take for granted, electricity has to be near the top of the list. Though it shouldn’t ever be interrupted, we’re not that suprised when the wifi is down. Streaming services still regularly buffer. Pinwheels, hourglasses, ellipses—an entire semiotics of technology’s foibles, failures, and inconveniences. But when the power goes out, everything stops. Everything. And even though they’re not that uncommon, we’re not prepared. As the former broadcast journalist Ted Koppel puts in his 2015 book Lights Out: A Cyberattack, A Nation Unprepared, Surviving the Aftermath, “We tend to come up with funding after disaster strikes.”

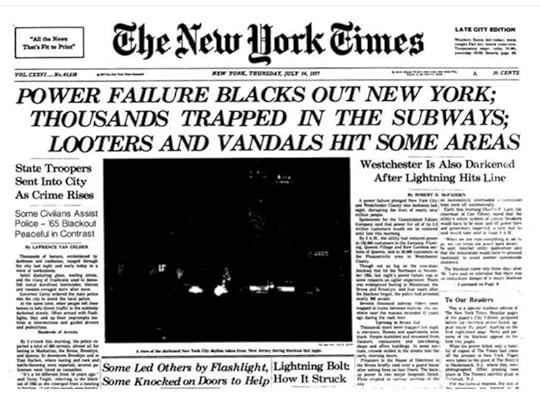

The New York Times on July 14, 1977 during a 24-hour blackout in New York City.

The New York Times on July 14, 1977 during a 24-hour blackout in New York City.With historical contrast, in his 2010 book, When the Lights Went Out: A History of Blackouts in America, the technologist David E. Nye writes that “by 1965, many New Yorkers regarded a blackout as a violation of the expected order of things. Yet it seemed an anomaly without long-term implications, and the paralysis of that night became the occasion for a liminal moment.” Such liminal moments are hard to come by, as the machinations of the city regularly work against the freedom they afford. Increasingly, the spaces required for dreaming, for creation, and indeed for freedom, are the product of artifice. They have to be intentionally assembled and deployed. Kodwo Eshun writes,

The technological conditions for intervention in the present have to be artificially constructed. They are not spontaneously available. To embark on a project that is set in the present, you have to renounce digital abundance by undergoing a temporal diet or media famine. You have to turn yourself into a castaway marooned on an island of the present separated from the abundance of digital archives and previous musical eras that continually saturate the contemporary.1

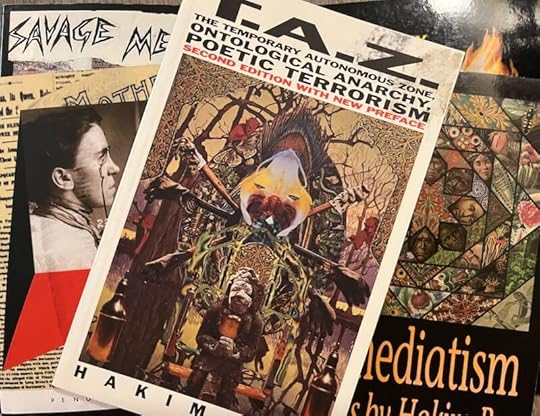

The idea of an outside or in-between space of dreaming recalls Hakim Bey’s temporary autonomous zone (TAZ). That is, the creation of temporary spaces that allow for moments of freedom, acts of creativity, and the availability of otherwise nonexistent autonomy outside the reach of established authority. Though certainly not the same thing, these spaces are similar to William Gibson’s idea of bohemias: subcultural backwaters that allow for new forms to flourish outside the influence of hegemony (Gibson cites Haight-Ashbury in the 1960s and Seattle in the 1990s as examples). Co-opted and all but defanged by the rave culture that followed its inception in 1991, the TAZ deserves a reassessment in our post-globalized world.

Hakim Bey’s

T.A.Z: Temporary Autonomous Zone

(Autonomedia, 1985) and other incendiary texts.

Hakim Bey’s

T.A.Z: Temporary Autonomous Zone

(Autonomedia, 1985) and other incendiary texts.One can imagine assembling one of Bey’s pirate utopias, but it’s easier to see them happening unintentionally. That is, when the mechanizations or modernism break down, leaving us alone in the moment, in an unintentional TAZ. The unintentional TAZ’s most recognizable form might be the blackout: a sudden inescapable shadow of spontaneity and creation.

Writing about a power blackout that affected 50 million people in North America in 2003, Jane Bennett defines assemblages as follows:

Assemblages are ad hoc groupings of diverse elements, of vibrant materials of all sorts. Assemblages are living. throbbing confederations that are able to function despite the persistent presence of energies that confound them from within. They have uneven topographies, because some of the points at which the various affects and bodies cross paths are more heavily trafficked than others. and so power is not distributed equally across its surface. Assemblages are not governed by any central head: no one materiality or type of material has sufficient competence to determine consistently the trajectory or impact of the group. The effects generated by an assemblage are, rather, emergent properties, emergent in that their ability to make something happen (a newly inflected materialism, a blackout, a hurricane, a war on terror) is distinct from the sum of the vital force of each materiality considered alone.2

Admittedly borrowing from Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari (A Thousand Plateaus), as well as Baruch Spinoza (Ethics), Bennett’s assemblage doesn’t lack intention. It lacks human intention. The blackout as monster, overtaking the city in a lumbering lack of light.

“I think bohemians are the subconscious of industrial society. Bohemians are like industrial society, dreaming.” — William Gibson

David E. Nye argues that public space transformed by New York blackouts is not an instance of technological determinism, a topic Nye has explored in depth previously.3 His take seems to flip one of Gibson’s well-worn aphorisms: The street finds its own use for things. If the technological use is culturally determined, then the use finds its own street for things. Nye writes,

By the beginning of the twenty-first century, blackouts were recognized as more than merely latent possibilities. They were unpredictable, but seemed certain to come. Breaks in the continuity of time and space, they opened up contradictory possibilities. From their shadows might emerge a unified communitas or a riot. The blackout shifted its meanings, and achieved new definitions with each repetition. For some, it remained a postmodern form of carnival, where they celebrated an enforced cessation of the city’s vast machinery.4

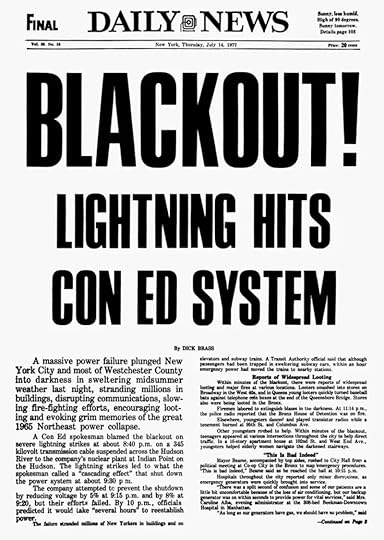

The Daily News front page on July 14, 1977.

The Daily News front page on July 14, 1977.Echoing the massive 1965 blackout, after an 11-day heat wave, on the evening of July 13, 1977, successive lightning strikes strained New York City’s already overtaxed power grid, shutting it down for 24 hours. A blacked-out bohemia pushed the already simmering hip-hop subculture to an overnight boil. Emcee Rahiem of Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five says, “The blackout of 1977 is what helped to spawn a multitude of aspiring hip-hop practitioners, because prior to that, the majority of aspiring DJs didn’t have two turntables and a mixer or the speakers. So, when the blackout happened, it just seems that everybody got the same idea at the same time. And when the lights came back on in New York City, everybody had DJ equipment.” Latin Quarter club manager Paradise Gray adds, “Not too many people in the Bronx could afford big sound systems until after the blackout. Then, everybody had sound.” To retrofit an idea, the Boogie Down became an unintentional temporary autonomous zone that night.

When you get to the blackout, it shifts hip-hop. It’s a pivotal moment, because like a week later, everybody was a DJ. Everybody. — MC Debbie D

Easy A.D. of the Cold Crush Brothers sums it up nicely: “The Bronx went from being decayed into something beautiful. The vibration of the music and the combination of bringing all those elements together, you had to be in there to feel it, because most of the time people only experience the music. But when you have all those elements in one place together, then you understand the essence of the hip-hop culture.”5 The blackout didn’t spawn the culture, but the autonomy it afforded pushed it toward national prominence.

Companion Compendia

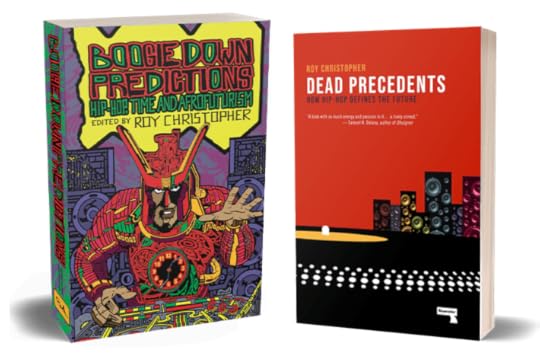

Companion CompendiaIf you’re interested in more about hip-hop and technology, might I recommend my book Dead Precedents: How Hip-Hop Defines the Future (Repeater Books, 2019) and the edited collection Boogie Down Predictions: Hip-Hop, Time, and Afrofuturism (Strange Attractor Press, 2022). The former is my own take on how the many cultural practices of hip-hop are the cultural practices of the 21st century, and the latter bridges hip-hop culture with Afrofuturism through essays by some of hip-hop’s most interesting thinkers, theorists, journalists, writers, emcees, and DJs.

“Roy Christopher’s dedication to the future is bracing. Dead Precedents is sharp and accelerated and Boogie Down Predictions is a symphony of voices, beats, and bars messing with time, unsettling histories, opening portals.” — Jeff Chang, author, Can’t Stop, Won’t Stop

Check out Jeff’s excellent Notes from the Edge:

Notes from The EdgeCulture. Politics. Music. Art. Ideas.By Jeff Chang

Notes from The EdgeCulture. Politics. Music. Art. Ideas.By Jeff ChangThis is a prequel of sorts to this newsletter from a couple of weeks ago, ICYMI. The New York blackout described above happened 48 years ago today!

Mike Ladd and me sharing a joke upstairs from Dusty Groove in Chicago, October 2017. Photo by Dan Bitney.

Mike Ladd and me sharing a joke upstairs from Dusty Groove in Chicago, October 2017. Photo by Dan Bitney.Today is also my man Mike Ladd’s birthday, so it’s a big day for hip-hop! He and I have something new slowly coming together, so KYEO.

As always, thank you for reading and responding,

-royc.

1Quoted in Gavin Butt, Kodwo Eshun, & Mark Fisher (eds.), Post-Punk: Then and Now, London: Repeater Books, 2016, 20; Iain Chambers writes, “With electronic reproduction offering the spectacle of gestures, images, styles, and cultures in a perpetual collage of disintegration and reintegration, the ‘new’ disappears into a permanent present. And with the end of the ‘new’—a concept connected to linearity, to the serial prospects of ‘progress,’ to ‘modernism’— we move into a perpetual recycling of quotations, styles, and fashions: an uninterrupted montage of the ‘now.’”; Iain Chambers, Popular Culture: The Metropolitan Experience, New York: Routledge, 1986, 190.

2Jane Bennett “The Agency of Assemblages and the North American Blackout,” Public Culture '7, no. 3 (2005).

3See chapter 2 of David E. Nye, Technology Matters: Questions to Live With, Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2006.

4David E. Nye, “Public Space Transformed: New York’s Blackouts,” in Miles Orvell & Jeffrey L. Meikle (eds.), Public Space and the Ideology of Place in American Culture (pp. 367-384), Leiden, NL: Rodopi, 2009, 382.

5These quotations are from Jonathan Abrams’ The Come Up: An Oral History of the Rise of Hip-Hop, New York: Crown, 2022.