Jo Ivester's Blog

April 19, 2020

Review of “Sissy,” by Jacob Tobia

“I was taller and shinier than the Rockefeller Center Christmas tree.” That’s what Jacob Tobia writes after describing their successful fundraising efforts for an LGBTQ homeless youth center in their recent book Sissy,” which they describe as a “heart-wrenching, eye-opening, and giggle-inducing memoir about what it’s like to grow up not sure if you’re (a) a girl, (b) a boy, (c) something in between, or (d) all of the above.”

“I was taller and shinier than the Rockefeller Center Christmas tree.” That’s what Jacob Tobia writes after describing their successful fundraising efforts for an LGBTQ homeless youth center in their recent book Sissy,” which they describe as a “heart-wrenching, eye-opening, and giggle-inducing memoir about what it’s like to grow up not sure if you’re (a) a girl, (b) a boy, (c) something in between, or (d) all of the above.”

It was the first time in their coming-of-gender story in which their joyfulness at their self-discovery truly came through. In Sissy, Jacob describes what it was like for them growing up surrounded by people who not only didn’t accept them, but who also didn’t understand. None of the labels people had learned were applicable.

My son Jeremy’s journey brought him from childhood, where the label “tomboy” didn’t capture his true gender identity, through his decision to have top surgery, change his name and pronoun usage, take hormones to go through male puberty, change in legal status, and finally, become an advocate. It took him a few years longer than it took Jacob, but I couldn’t help but see the similarities.

And the differences. So many differences. Jeremy was identified as female at birth, but eventually figured out that he is a man. I’ve written previously about my initial reaction of not believing that being transgender is a real thing, through recognizing that the child I love is the same person, regardless of his gender identity, to becoming an advocate for the transgender community. As part of that, I worked conscientiously to use the right pronouns, to refer to my son as “he” and to call him by his new name.

I was pleased that this change came easily to me. With the exception of difficulties when I go into storytelling mode about Jeremy as a child, I rarely slip up. But no sooner had I become accustomed to using respectful terminology for binary people like my son (i.e., those who consider themselves to be either male or female) when I started to meet people like Jacob, individuals who are non-binary, who’s inner sense of gender is neither strictly male or female, but somewhere on the spectrum between the two, or, as Jacob says, “all of the above.”

The book Sissy welcomes me into the world of the gender nonbinary and nonconforming. Through sharing their story, Jacob becomes a real person to me, with feelings, a history (or as they might say, a “herstory”), with successes and failures, with self-understanding and a growing sense of understanding the world around them. The writing is at its best when Jacob relates anecdotes to illustrate their points. Their decision to wear high heels and then write about it for a college admissions essay. Getting harassed while a student at Duke and feeling chagrined that they didn’t do more to fight the bullying. The reaction of their mom about going to church presenting as their true self.

It is when Jacob shares these vignettes that the reader sees them as a complete person. That’s when I found myself choked up and wanting to give them a hug and congratulate them on what they’ve accomplished.

Sissy is a must-read for those who want to extend their understanding of the transgender community to include the nonconforming. And for nonconforming youth who rarely get to see themselves in literature because characters like them are rare, this book will envelop them with a sense of acceptance.

The post Review of “Sissy,” by Jacob Tobia appeared first on Jo Ivester.

March 30, 2020

Writing Respectfully About my Own Family

The excitement is building. My new book, Once a Girl, Always a Boy will be hitting book stores soon. Anyone who reads it will learn about deeply personal conversations between members of my immediate family.

As I was writing, I worried that revealing these intimate, sometimes painful details was an inappropriate invasion of my children’s and husband’s privacy. I didn’t worry about sharing my own inadequacies and faltering steps. That’s one thing. It’s entirely different to describe those of others.

Why write?

So why do it? Why take the risk of making anyone feel uncomfortable? And who am I to do that? I am the mother of a transgender man. Who is in a better position to speak out, other than transgender individuals themselves? I’m already a writer. And a public speaker. Also, I have a skillset that I bring to the table that not every parent does.

Why does that matter? Why is it important for parents to share their stories? Why are we able to communicate effectively? It is exactly because we are parents. Our readers and listeners may not understand what it means to be transgender, but most people respond to the reality of a parent loving their child. So, like many other parents of transgender children and adults, I speak out—in my writing, in meetings with our legislators, at public gatherings.

Getting Permission

I asked my family’s permission before setting out to do this. Each one of my children—and children-in-law—was clearly uneasy with what I might say, with how I might make them look. But they understood my desire to help people to grasp the struggle facing transgender folks and they supported that commitment.

I promised that they could read every word before publication and ask me to cut anything that was too personal, or to rework anything they felt was inaccurate or inadequate. Then they took the time to review it all, even when it felt awkward or painful. The resulting conversations were mind-boggling as we respectfully wrestled through differing memories and assumed intentions.

The family bonds grew deeper. I set out to write our story to help other families, and in the process, I was rewarded with some amazing changes in my own.

The post Writing Respectfully About my Own Family appeared first on Jo Ivester.

July 25, 2017

Texas Discriminates Against Our Transgender Community

They did it. The Texas Senate just passed the very poorly thought through Senate Bill 3. Hiding behind a bogus argument for “privacy,” Senator Kolkhorst authored and argued for a bill that discriminates against our transgender community. Now it’s up to the House to maintain our dignity and prevent Texas from becoming the next North Carolina.

This is personal for me. SB3 discriminates directly against my son. He grew up in Texas. He works and pays taxes. He is sweet and charming. He cares about his family and friends. And he is transgender.

When he first came out three years ago while a student in Colorado, he said he’d never move back to Texas. You see, the laws in Colorado protect him from discrimination; there are no similar state-wide protections here in Texas. But when his siblings started having babies, Jeremy had to be a part of it. He wanted his nieces and nephews to grow up knowing him. So, despite Texas being a less supportive environment, my boy came home.

Now he lives in Dallas where he is protected by the city’s non-discrimination ordinance. He cannot be thrown out of his apartment because of who he is. He cannot lose his job because someone doesn’t like the fact that he is transgender. He can participate fully in public life, not worried about where to use a restroom.Please don’t let the politicians take that away from my son and others like him.

Transgender people have been using the restroom of their choice for years and years with no problem. They are not a threat. In fact, if forced to use the bathroom on their birth certificates, then the opposite will be true. Transgender people, especially our youth and trans women of color, will be at risk.

Don’t let our politicians attack my son for their political gain. He and others like him are worthy of protection and respect, just like the rest of us. Don’t let them discriminate against him. Please urge your Texas House Member to oppose any anti-transgender bathroom legislation during the special session.

The post Texas Discriminates Against Our Transgender Community appeared first on Jo Ivester.

July 19, 2016

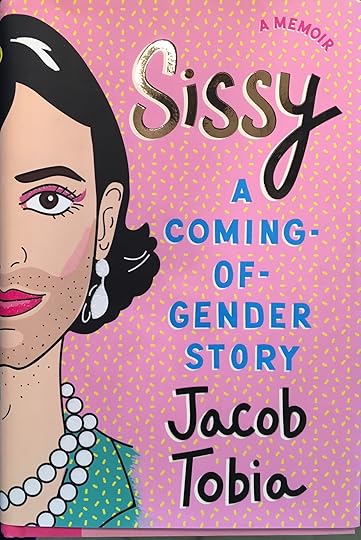

Texas Transgender Non-Discrimination Conference

Our son Jeremy is a shy man. He would like nothing better than to live his life as the man he has become and never make an issue about being transgender. He even contemplated moving to a new town to get a fresh start after he transitioned, so that nobody would see him as the man who used to be “Emily.” He wanted to do that, but he didn’t; his friendships in Boulder ran too deep. So he stayed. It’s been worth it. His community sees him as a man, even though they were first introduced to him as a woman. It’s been pretty darn awesome.

Jeremy is not especially political. During the dinnertime conversations as he was growing up, he’d listen attentively, but rarely express his opinion. Not that he didn’t have one; he did. But he felt as if all perspectives were being discussed and so there was no purpose to adding his own. Most of the time.

That’s not true anymore. When Jeremy came out on Facebook a couple of years ago, our family was deluged with messages. First came the appreciative and supportive notes. Folks expressing pride in his courage and in his father’s and my acceptance. Then came notes from other transgender individuals, young adults who as teenagers had been thrown from their homes when they told their parents who they really were. It was heartbreaking.

Jeremy decided at that point to forego his privacy and instead join Jon and me in trying to make a difference in securing rights and respect for all transgender people. So that Jeremy and others like him can be who they truly are and not live in fear. That is why we are giving a talk together at the Texas Transgender Non-Discrimination Summit later this month. Please check out their schedule and program at http://txtns.org/summit/program/.

The post Texas Transgender Non-Discrimination Conference appeared first on Jo Ivester.

May 30, 2016

Our Transgender Children

About a month ago, I had a Facebook post go viral. I’d written about my 26-year-old transgender son, Jeremy, and how I miss him. He won’t move back to Texas because here, the laws do not protect him. Not only can he be fired from a job for being transgender, he can be thrown out of his own home. The Department of Justice is trying to fix that, to interpret transgender people as a protected class, but the Texas politicians are fighting that. Please don’t let them get away with this bullying.

About a month ago, I had a Facebook post go viral. I’d written about my 26-year-old transgender son, Jeremy, and how I miss him. He won’t move back to Texas because here, the laws do not protect him. Not only can he be fired from a job for being transgender, he can be thrown out of his own home. The Department of Justice is trying to fix that, to interpret transgender people as a protected class, but the Texas politicians are fighting that. Please don’t let them get away with this bullying.

When I posted my comments, I hoped to broaden my community’s awareness of trans issues. With that increased awareness, I hoped for greater acceptance. And I accomplished that. The outpouring of support and yes, love, was tremendous. But something else happened as well. Not only did I broaden my community’s awareness, I also broadened my community itself, hearing from several transgender teenagers who thanked me for speaking out on their behalf.

One of those teenagers is named Quinn. He’s given me permission to share what he wrote. It’s beautiful, poetic, and it might make you cry.

My name is Quinn.

I’m 15 and am a transguy, just like your son.

Unfortunately, my father and stepmother think much like Texas legislature.

They cannot accept me for who I am, saying that “Transgender people come from an evil society and should be put in mental institutions.”

But I can assure everyone that there is nothing mentally wrong with me. Yes, I suffer from anxiety, but I do not intend to hurt someone with fear.

What is wrong with me?

Do I look like I would hurt anyone?

I couldn’t hurt anyone if I tried.

In fact, in the restroom, I’m more worried about ME getting raped.

Everyone hurts me for just trying to do what society says, “Just be yourself”.

What they don’t mention are the parameters in which you must remain to be accepted.

I am only seen as being “one of those trans kids”, “that he-she”, and my favorite, “a tranny”.

They can’t see who I am as a person.

I have strengths.

I care about people.

I can draw.

I can tell you every president of this country that hates me in order.

I’m a good public speaker, and I’m not afraid to do it.

I’m loyal to the core.

But all they see is WHAT I am, not WHO I am.

So do tell me.

What’s wrong with me?

The post Our Transgender Children appeared first on Jo Ivester.

November 4, 2015

Atticus Finch – Hero or Racist?

My father was Atticus Finch and I was Scout. I never doubted that from the first time I read “To Kill a Mockingbird” when I was ten years old. Dad was a foot soldier in the War on Poverty, having moved our family from the white suburbs of Boston to an all-black town in the Mississippi Delta so that he could become the medical director of a new clinic, built to serve the poor black population for miles around. That was back in 1967 and now, almost fifty years later, his clinic is still standing and it is the community’s largest employer.

My father was my hero, just as Atticus was Scout’s. He knew what was right and he did it, regardless of the cost, to him or his family. He took care of his African-American patients when white doctors in the nearby towns refused. I was proud of him.

Like many others who grew up idolizing Atticus Finch, I couldn’t wait to begin “Go Set a Watchman,” Lee Harper’s companion novel to “Mockingbird,” actually written first and presented from Scout’s adult perspective looking back in time. (Spoiler Alert) Like many other readers, however, I was disturbed by the portrayal of Atticus as a racist. To Scout’s dismay, she discovers that although Atticus as a lawyer defends the rights of African-Americans, he personally doesn’t want to rock the boat. He believes that change should come slowly, in small bites that won’t make people uncomfortable.

Some find the Atticus portrayed in “Watchman” to be unrealistic, the cognitive dissonance he displays somewhat unbelievable. How can one individual fight for the rights of a black defendant, yet not want to make waves when it comes to the rights of black people in general? I actually find this characterization to be quite plausible. Yes, Atticus was devoted to the concept that everyone deserves a fair trial and equal treatment under the law. He put himself and his family at risk to stand by that concept.

But that’s where his support of civil rights both started and ended. He believed that good people needed time to adjust to the complete integration of African-Americans into the community. And he was wrong. The Atticus of “To Kill a Mockingbird” was heroic; the Atticus of “Watchman” was not. No wonder Scout was horrified by her father’s behavior.

The post Atticus Finch – Hero or Racist? appeared first on Jo Ivester.

October 19, 2015

Are the Police Our Friends?

A little blonde boy steps confidently out of his kindergarten classroom on the first day at his new school, but he makes a wrong turn and heads directly away from the spot where he’s supposed to meet his older sister for the short walk home. When he never appears, she goes to the office to call home and their mother contacts the police. The little boy, confused by his surroundings, approaches an officer serving as the school crossing guard and says, “I’m lost. Can you take me home?” Between the lieutenant at the station and the policeman at the school, the family is quickly reunited.

That little boy was my big brother. We grew up in an upper-middle class suburb of Boston, where my mother told this story repeatedly as a means of teaching my siblings and me that the police were our friends, someone we could trust to help. That changed in 1967 when we moved to all-black Mound Bayou, Mississippi. There we were taught to be afraid of the white police in the nearby towns. We were told that many were KKK members and were believed to be involved in violence against African-Americans. They viewed us as outsiders from the North, civil rights workers, and Jews – everything the KKK hated. The police were not our friends.

People from different backgrounds are raised to have different reactions to the police. As a young child, I was taught to trust them; later I was told they were my enemy. In each case, this training led to a specific perception of the police, a subconscious reaction. Police officers also receive training. They are taught to be aware that any interaction can turn dangerous and to always be ready in case it does.

What we have to recognize is that – like the rest of us – officers have a subconscious reaction to the people they encounter. And often that response depends sub-consciously on characteristics such as race. An officer seeing me – a white, middle-aged, petite woman – is unlikely to feel threatened. Too many times, though, police see an African-American and – without necessarily meaning to do so – assume that the situation is more likely to turn dangerous. They may not acknowledge this or want it to be true, but it’s a reaction buried so deeply that it influences behavior. This is a highly unfortunate example of systemic racism. And that’s what we as a society have to change!

We must build a sense of trust between the police and community members of color. This can’t be done when even a handful of officers, influenced by deeply buried fears, escalate to violence as their first line of defense. The time has come for every police force throughout the country to acknowledge that we have a problem and need to train every single officer to always behave in a respectful, de-escalating manner. To those police who already do this, thank you for your service. To those who need to change, please recognize the situation and actively become a part of the solution.

The post Are the Police Our Friends? appeared first on Jo Ivester.

September 18, 2015

Is Black Beautiful?

The phrase “Black is Beautiful” that swept the nation in the 1960s was heard frequently in my mother’s classroom. Her students were surprised one day to walk in and see written boldly on the chalkboard, “Black is Not Beautiful.”

When the students, all of whom were black, began to object, she pointed out that black has come to symbolize unpleasant aspects of life. She didn’t have the brain science to prove it, but she suggested that this may go back to the early days of humankind, when early people were afraid of the night, fearful of the cold and dark that came with the setting sun. Knowing that her students knew their bibles, she added, “Later, we see this fear reflected in religious writings.”

Her students were quick to offer an example: the plague of darkness on the Egyptians when they wouldn’t free the Jews. When asked the colors of Heaven and Hell, nobody disagreed when one student stated “white and black.”

Then my mother, always looking to quote Shakespeare, offered, “Black is the badge of hell.”

“Do you still think black is beautiful? In almost every society around the world, the color black evokes feelings of melancholy and despair, of alienation and evil. White, on the other hand, is usually viewed as symbolic of virtue and purity, of truth and spirituality.”

Accustomed to her teaching style, her students knew that more was expected of them, that it was time to respond. “That may be true, Miz Kruger, but all that stuff has nothing to do with us, with who we are. We are beautiful.”

“Yes, you are indeed beautiful.”

This anecdote is from the classroom of my mother, Aura Kruger, who began teaching English in an all-black high school in 1967.

The post Is Black Beautiful? appeared first on Jo Ivester.

April 1, 2015

Small Worlds and Full Circles

Who is that speaking intently with President Johnson back in the early 1960s? It’s my uncle, Herbert Kramer. I’d never seen the picture when I was growing up, but I knew that Uncle Herbie had a way with words and had worked closely as a publicist and speech writer for the Kennedy and Shriver families. I knew he had penned the motto for the Special Olympics: “Let me win, but if I cannot win, let me be brave in the attempt.”

Who is that speaking intently with President Johnson back in the early 1960s? It’s my uncle, Herbert Kramer. I’d never seen the picture when I was growing up, but I knew that Uncle Herbie had a way with words and had worked closely as a publicist and speech writer for the Kennedy and Shriver families. I knew he had penned the motto for the Special Olympics: “Let me win, but if I cannot win, let me be brave in the attempt.”

Herb and my father, Leon Kruger, had been best friends and sometime roommates during their undergraduate years at Harvard, initially brought together by the university due to the alphabetical proximity of their last names. Soon after my father and mother began dating in college, my grandmother asked Leon to bring home a nice boy for younger sister, Karyl, still in high school. The two quickly fell in love and were wed near the start of WWII. Our families, with eleven children in all, spent many summers together at our grandparents’ home on Cape Cod.

I remember Herb as my most playful uncle, always quick with a humorous comment, always willing to take charge of eleven children for a trip to the beach or ice cream store. It was only as a college student that I began to realize that several political heavy-hitters relied on his wordsmithing and advice. It was the mid-1970s and I was visiting the Kramer household in West Hartford when I overheard Uncle Herbie on the phone talking with Eunice Shriver about whether or not her husband should run for president. My cousins all just wandered about the kitchen getting breakfast, not paying any attention. But I was giddy with excitement.

Fast forward thirty years to my mother’s decision to write down the family history and all the anecdotes. I worked closely with her; the resulting journal became the starting point for my recent book, The Outskirts of Hope. In our many conversations, she reminded me that it was the US Office of Economic Opportunity (OEO) and Tufts University that had provided the funding for the clinic where my father worked in Mound Bayou, Mississippi, the all-black town where we lived for two years starting in 1967, where my mother was recruited to teach English at the local high school and I was the only white student at my junior high. But we didn’t talk about the fact that Uncle Herbie was the Director of Public Affairs for OEO during that time. I learned that a little later.

What I just learned this week was that my uncle, in addition to his work with OEO, was involved more generally with Lyndon Johnson’s War on Poverty. In his speech announcing that effort in 1964, President Johnson said, “Many Americans live on the outskirts of hope, some because of their poverty and some because of their color, and all too many because of both. Our task is to help replace their despair with opportunity.” My cousin, Paul Kramer, now tells me that he believes it is very likely that his father penned those words, both because of his role during that time as Communications Director for the War on Poverty, and also because the phrasing sounds a lot like the way Herbie wrote.

So how does this complete the circle? Not knowing that these words were probably written by my uncle, I had selected this speech excerpt for the opening pages of my book. Upon reading them, my editor, Alexandra Shelley, suggested that I use the phrase “the outskirts of hope” as the title for my book. I didn’t know when I used her idea that I might well be using an expression coined by my own uncle.

The post Small Worlds and Full Circles appeared first on Jo Ivester.

February 3, 2015

Deciding to Write in Dialect

When my mother started teaching, the word Ebonics hadn’t yet been coined; nobody had grappled in the academic journals as to whether to accept it in the classroom or make students speak a more mainstream, i.e., white, speech. All she knew was that she couldn’t understand her students easily and assumed that if she couldn’t, than neither could others and this barrier in speech would create a barrier in life. So, without saying that black speech was bad, she explained to her students that it was different, that it might hold them back, and that she was going to teach them to speak in a way that would help them get ahead. She encouraged conversation about whether it was fair that they had to learn a new way of speaking to fit in, expressing her own pragmatic opinion that this was a moot point.

Because I was a child when we moved to Mississippi, I learned to understand black speech quicker than the rest of my family, the same way a ten-year-old transplanted into another country can learn the new language faster than the adults. There were moments when I had difficulty, mostly with the children from out on the plantations; it seemed like the kids from town spoke pretty much the same way I did.

When my mother first started writing her journal, she was adamant that she didn’t want to write in a way that tried to capture black speech, viewing that as disrespectful. But after much consideration, I decided that her efforts to help her students modify their speaking patterns were such an important aspect of her teaching, that I wanted to illustrate it. Even more than that, putting mainstream English into the mouths of people who didn’t speak that way didn’t feel authentic. And that’s something I really cared about, authenticity.

So I’ve introduced it into the conversation, writing, using the phrase, for example, “That be right,” instead of “That is right.” Another example is that I’ve sometimes eliminated the final consonant from words, choosing “explainin’” rather than “explaining.” I’ve used “dem” for “them” and “Miz” for “Mrs.” I haven’t been consistent in how I’ve done this, for there was no consistency. And by the time I’d lived in Mound Bayou for a few weeks, I didn’t even hear the differences.

But my editor did. Alexandra Shelley accepted me as a client following the completion of one of my early drafts. It was only after I acknowledged that I was near the beginning of the process rather than the end that she took me on. We talked for over an hour in our introductory meeting and covered a lot of territory, but two pieces of advice hit me hard. One was that I had to go back to Mound Bayou and interview people who knew my mother and so I could learn how the town had changed, and validate my memories. The other was that the absence of black speech made my book seem unrealistic.

The post Deciding to Write in Dialect appeared first on Jo Ivester.

Jo Ivester's Blog

- Jo Ivester's profile

- 30 followers