Barbara Rhine's Blog

August 24, 2021

Migizi Will Fly–A Grandmother’s Journey to Stop Line Three

Migizi Will Fly

A Grandmother’s Journey to Stop Line Three

By Barbara Rhine

It was my first flight out into the wider world since Covid geared up, so I was a hot mess on May 22, 2021, when I began a five-day trip to Minnesota with an uphill task: Stop “Line Three”—the pipeline Enbridge Inc. has planned to transport Canadian tar sands, the dirtiest of oils, to Lake Superior for export. Thirty-one of us from Northern California’s 1000 Grandmothers for Future Generations, working with indigenous leadership on the ground, organized this excursion. From the Lakota reservation in South Dakota five more grandmothers, who divide themselves into OG’s (not gangstas, but Old Grandmothers) and YG’s, joined us. All immunized, we assured each other. Here is the story of my journey.

At 3 AM I am awake and putting things in the car, to make sure I’ll have time for any formalities required for the 6 AM flight. The packing has been ridiculously difficult, especially in my head. Clothes for all weather, waterproof rubbers for wet mud, proof of vaccination both on my phone and on paper, masks and a shield for the airport and plane, leave keys at home in case of arrest, read up on MN laws re protest so any arrest would at least be on purpose. Yadayada, on and on, in an endless anxious mental loop . . .

The security line is long; the airplane packed. Squeezed into a middle seat, I settle down with my coffee and oatmeal, to try for calm. The guy on my right, however, seems to have asked me something, because all of a sudden I am explaining Line Three and listening to his lavish praise for my courage.

Minnesota is still riven by conflict since George Floyd’s murder, he says. Not black himself, he tells me that he has seen the police in his neighborhood go up the stairs to hassle a dark-skinned resident smoking on the man’s own front porch. Next he informs me that there are lots of white people who admire Kyle Rittenhouse—the white kid in Kenosha WI who went unchallenged by police as he strutted down the street, arms raised, rifle hanging from his chest, after killing two and wounding a third. And Minnesota is certainly divided over Line Three, he assures me. He insists that I take his phone number, so if I get into trouble he can send his lawyer out to help.

Eventually I recline, moving the back of my chair the full inch that Delta allows, close my eyes and ask myself again: Why did I come on this expedition?

My own climate activism began about thirty years ago, when, due the nonprofit Union of Concerned Scientists, I realized the terrifying depth and breadth of what was then usually referred to as the Greenhouse Effect. Obsessed, I lectured everyone I knew, most of whom had no idea of, and little interest in, whatever the heck they thought I was talking about. Now finally that has changed. The word climate is on everyone’s lips and sometimes even in their hearts. Yet CO2 emissions, here in the United States and world-wide, continue to rise.

Climate scientists agree that we humans must wean ourselves from use of fossil fuels, but the oil and gas industry remains unwilling even to try. Their answer to every attempt to limit their scope and profit is oh no, that won’t do any good. If we close down coal in the US, then China will just get it from somewhere else; if we back off fracking, our workers will lose their wonderful jobs and other countries will make the money. And just in case their profits start to fall? They push out more and more single-use plastic made from oil, and so contaminant of the oceans that its weight is predicted to exceed that of all the fish by 2050.

On April 4th this year, Elizabeth Kolbert published a comment in the New Yorker, where, without questioning President Biden’s sincerity, she worried that, even if all of his measures passed, CO2 emissions still would not turn that crucial corner and start down. Because they hadn’t under Obama, despite that President’s good intent. Because it’s so easy for the profiteers to distract us with every other issue on the planet.

As they did for thirty years according to Bill McKibben’s book Falter, when the oil executives accepted the science of climate change enough to alter their business plans accordingly, and yet financed and perpetuated lies and obfuscation about that very same science. Since science does not pause for lack of political will or political compromise, that thirty years of misinformation has caused irreparable damage to the future of your grandchildren and mine. Shouldn’t there be a punishment? Boiling in Oil, perhaps? Ha! Money. At least money. Lots of money.

Maybe you can tell—fear and fury about climate often have their hands around my throat, and this was true yet again, just when 1000 G’s was planning the trip. So I came. To see if the trees and the waters and indigenous culture could help me stay in the struggle rather than succumb to anger and despair. And to do my part to Stop Line Three.

After landing in Minneapolis four of us rent a van and set off on a three-plus hour drive northwest. Flowing streams, placid lakes, the headwaters of the Mississippi in the form of a large, languid creek—water is everywhere, in a gracious level landscape of astounding loveliness. Eventually we arrive at Welcome Camp, one of at least nine scattered through the area, all led by Warrior Women, all faced off against Enbridge.

Ah, Enbridge. A natural gas transmission corporation that took in profits over $50 billion Canadian dollars in 2019. With its flat cleared easements all ready for the pipeline; with its following and surveillance of protesters wherever they go; with its convenient arrangement to cover any overtime accrued by the local sheriffs. A formidable foe.

Enbridge has a terrible safety record that includes over 1068 pipeline spills, which have leaked a total of at least 7.4 million gallons of oil. The new Line 3 abandons an old pipeline to deteriorate in place, sets out for 300 miles through pristine wild rice habitat and under more than 200 bodies of water on a new route, and if completed would double the quantity of dirty tar sands oil being transported through the U.S. If finished, Line 3 will have the climate impact of 50 coalmines. Ah, Enbridge…

A line of colorful signs marks what is otherwise an ordinary entrance off a two-lane road through an open gate, into the Welcome Camp. Impressions, in order of occurrence:

Canopies of birch, oak, evergreens and aspen, quivering in the sun, shaking in the wind, insistent with the beauty of the natural world.Makeshift structures scattered about, along with tents, for shelter.Mosquitos that bite through any fabric on all parts of the human body.Comfortable camp chairs in circles, around outdoor fire pits.Delicious food cooked by a large and busy guy named Turtle, served buffet style.Tiny ticks, harbingers of Lyme’s Disease, one crawling up my arm, another along the lip of the van’s trunk, dangerous enough to require the grandmothers to inspect various crevices of each other’s bodies nightly to make sure they haven’t burrowed under any skin.The first of many in-person meetings begins, and they continue at the Blue Moon lodge where we stay the initial night, and at the Big Sandy Creek lodge where we stay the other nights. Frequent meetings. Long meetings. We have already had several over Zoom before we embarked; we will have more on Zoom after we get back. Grandmothers are good at meetings.

At one we sing and even dance a little, putting “one foot in front of the other, to lead with love.” At another we fold, string and hang chains of Origami cranes and butterflies. We plan meals and assign tasks of shopping, cooking, cleanup. We figure out who is going to create the art we need at our planned demonstrations, and how we will transport what’s needed for that art. We discuss how to respect indigenous culture and leadership. We argue a bit, and compliment each other a lot, for all their hard work.

Back at the Welcome Camp on our second day, at one of these meetings, a sweet, round-faced guy named Tim Coming Hay, hands out cards that read “Not A Lawyer,” give his email address as arrestee.advocate@gmail.com, and instruct on what to say in case of arrest: “I am going to remain silent, and I wish to speak to a lawyer.” So Tim obviously means business. But he also says that arrest in Aitkin, the nearby county seat where we are planning to picket in front of the courthouse tomorrow, is unlikely, at least for us, at least at mid-day. And so far, except for its big fat cleared adjacent easement, Enbridge has been nowhere around to confront our group of sweet-faced elder women.

Late that night, though, some of us drive back to gather at a bonfire, off the road near an entrance to a path to the river. The elders and youngers combine voices and songs to wonderful effect. The whole time, across the street, someone sits in a dark unmarked car with a flashing orange light. Enbridge, watching. . .

The next afternoon, behind the local high school we unload our equipment in eighty-plus degree heat—a long blue ribbon of cloth to represent a river, a large banner, smaller picket signs, flyers to hand out. Students are descending from a nearby school bus, and we are eager to talk with them, but most ignore our attempts to engage. It occurs to me that we should be shouting “Listen to THE grandmothers,” instead of “Listen to YOUR grandmothers,” ‘cause I’m pretty sure their grandmothers are not saying the same things we are.

Some of us yearn to be arrested, and in some moods I’m one of them, but over the next two hours, while we march and sing and chant and yell, not a single cop appears. In fact no one at all goes in or out of the courthouse. I worry that this is a colossal waste of time. Marcy, one of the Lakota YG’s, tells me, though, that Aitken is like the small towns near where she lives, and that everything is noticed.

Some folks in passing cars honk in support, and a few of the kids hear us out. Later, as we sprawl exhausted on the lawn of a small nearby public park, a reporter from the local paper comes over to speak with us. She is friendly, but unwilling to have her picture taken at all, let alone posted. We stop at the Dairy Queen on the edge of town after all this, and I get one of those butterscotch cones that must be six inches high, which makes me way too happy.

Later we are told the local sheriff insisted we had disobeyed orders to leave the premises. No such thing occurred. Marcy was right. Not only were we seen, but we were important enough that a lie had to be constructed.

Back at the Welcome Camp a few grandmothers strip to dip in the Mississippi’s headwaters down that path from the road. Normally that would be my m.o., at least when I was just a few years younger, but I right now I so tired that all I can do is lie on a bench and swat mosquitos. A hopeless task.

Next comes another long meeting at the Welcome Camp, with inconclusive results for the next morning’s plans, but then again also with another delicious buffet supper. Back at Big Sandy, I embark through a twilight without mosquitos (do they use DDT, or what?), on a walking tour of our far-apart Grandmother suites, and enjoy the synchronicity between a little vodka and some unstructured human company. All this culminates in an invitation from Dawn, another Lakota YG, to go with them and the OGs and the rest of our Coordinating Committee to a different camp, the following day.

So we set out at 8 AM on the familiar long drive, again through fabulously beautiful countryside, to arrive at a place where leaves of fresh green and bright yellow swish and sparkle in the early morning sun. The camp is called “Migizi,” in Ojibwe. “The Eagle” in English.

Substantial tents promise orderly interiors and true protection from the ever-changing elements. (The first night had plunged into the forties, lashed with hard rain; the second day was cold; the third had been in the eighties; now the fourth day presents with a benign and gentle morning breeze.)

Here is how the Migizi residents had prepared for the visit (taken from a Facebook post written by Taysha, Migizi’s camp leader):

“. . . The Grandmothers are coming!! we told one another as we rushed through camp. All morning my sister Ember had spent chopping mushrooms and onions. Others prepared potatoes for hash browns. Our chickens had given us three new eggs for the scramble. . . . The water bubbled at the fire ready to become coffee and Swamp tea. . . We all ran about gathering gifts for the Grandmothers—sage, tea, sweet grass, coffee—to welcome them home. By the gate a young man and his father prepared our humble driveway for the vehicles that would carry our Grandmothers safely here, . . . laying out a rug and raking the dirt . . . We braided our hair, put on our ribbon skirts and shirts, smudged down and gave thanks for such a beautiful day. Our drum carriers warmed their drums at the fire, preparing their hides for the songs and ceremony.”

A young man greets me with a square of cloth that reads “Migizi will Fly,” stamped with a black eagle whose wings hang down to spell “Stop,” on the left side and “Line,” on the right. The “3,” in red, is on the bird’s body. He fastens it to the back of my shirt with safety pins, and we lucky grandmothers settle into another circle of comfy camp chairs.

Taysha, surrounded by her three daughters and one toddler son who plays at her feet, receives her Lakota grandmothers with a formal welcome, followed by a painful account of a particular historical conflict between the Fond du Lac, her own tribe, and the Dakota, closely related by language to the Lakota. Her face bathed in tears, she concludes, after a description so chilling she must have meant for it to be private between herself and the OG’s and YG’s, that a serious debt is owed from the Fond du Lac to the Dakota. And so she intends to repay it by gifting the land where we are—a small private parcel, infinitesimal compared to what each tribe had before the white settlers arrived—to the Dakota nation when a warrior visits next week.

Some of the camp residents have joined us to eat, including Phoenix, a native woman whose beautiful clothes highlight the solemnity of her downturned mouth. Another young man asks if I want honey or maple syrup on my pancake. Delicious food is served.

With more tears and lots of laughter, Taysha moves on, to describe her own childhood—scarred by adults with addictions and men who “took what they wanted” sexually. Once, she tells us, she was invited to an “officer’s training.” By whom or for what was not clear to me, but when she got there they told her it involved alcohol, enough to get her fully drunk. She doesn’t drink, she assures us, but that day she made an exception. They asked how much she weighed, and at that time the answer was 210 lbs. (Now Taysha is nowhere near that big.) They calculated this meant she had to have eleven drinks, after which, she tells us gleefully, she sexually harassed every man in the room, the details of which she was too drunk to remember, except for one guy shouting out to her that she had messed with his dick.

I find this tale puzzling, disturbing. But whatever has or hasn’t happened to Taysha, she’s no one’s fool now. She knows the men who work on the pipeline because the Fond du Lac tribal leadership has a deal with Enbridge, which promises jobs in exchange for support of the project. Taysha remains in fierce opposition to Line 3. She intends no help at all for those who take the Enbridge jobs, but she does admit that she enjoys the way the workers welcome her arrival at the pipeline, because the resulting brouhaha will stall the work and then they’ll get overtime. She understands that this does not mean they are ready to walk off the job. Still, she hopes that might happen some day.

Done eating, Taysha contemplates her plate and informs us it’s compostable, which she had thought meant that she could throw it away. No—she had been corrected! Compost! You let it become part of the earth; you use it for the future crops. She is amused by her own ignorance; proud of her Camp’s determination to run off renewable energy alone.

I get up to wander around. I pee on the ground behind the bushes, as instructed by a sign on the wall of the toilet structure. Put back together just in time, I murmur hello to a young person passing by who would have been called a transvestite in my time, with her strawberry-printed dress, her elaborate makeup and long lashes.

When I get back to the circle, the 2-Spirit young man with painted nails and colorful clothes, with four names including two that sound Jewish, has taken center stage. He tells us that he reveres ritual—in each word, each hand gesture, even the shake of his head. His life story is another one of sorrow. His parents raised him in Southern California, where they had left their indigenous culture behind, and substituted alcohol and drugs. He found his people’s Rez as a teenager, but was rejected there due to his 2 Spirit nature. So he will do his ritual observance here in Migizi, his true home, he assures us, tears interspersed with tender smiles. Then he sings and plays his guitar sweetly, and with skill.

Children run everywhere while Taysha’s blond toddler stays right at her feet. His father, the only other blond in sight, is a spare young man who has helped with cooking and cleaning before our eyes, and has also told us he’s been arrested for sitting atop a pipeline. Eventually that dad, whom Taysha has named as her partner, hustles the older girls off to remote learning, and all too soon it ‘s time to get back to Big Sandy for the noon meeting.

The Lakota Grandmothers, dignified throughout, say their formal goodbyes, and we invite the Migizi community to join us at Big Sandy later later that evening, for our ritual to mark the year’s anniversary of George Floyd’s murder.

Taysha summed it up on Facebook:

The grandmothers arrived in two vehicles, many of them Lakota from Cheyenne River and Pine Ridge, brought by our allies 1000 Grandmothers. W e sat around the fires sharing in food, laughter, love and medicine, gifting our stories and support for one another . . . we shed tears at the arrival and departure of the. . . Grandmothers who traveled so far to voice their support for us, our camp and our cause. We made relations, and are moving forward with the hope to strengthen them. With the strength, prayers, and blessings of the Lakota people, we felt renewed in our oath, to Protect the Sacred and #StopLine3.

Back at Big Sandy, talking and laughing as I help cook our last group dinner, I wonder whether any of the Migizi folks will show, and also marvel at the fact that the next day I’m scheduled for a 4PM flight back from Minneapolis to SFO. The arduous trip is almost over.

We eat, clear up and sit down to do the Floyd ceremony. The door opens and Migizi comes in. Taysha and her daughters and her partner and their son. The musician with his intensity for ritual. Others whose faces are familiar from the morning. There must be 15-20 of them, counting the kids. People scramble to make room, and everyone looks to Starhawk to begin the commemoration.

Remember Starhawk—the Second Wave feminist neo-pagan witch from back in the day? If you look her up you will find that she is still active, writing and conducting ritual in earth-based spirituality. One of our grandmothers, here throughout, she has been a quiet presence. Now she talks about her own roots in Minneapolis, then leads the packed room in eclectic prayer. Taysha speaks directly of her knowledge that her son, due to that blond hair, will never face the dangers from the police that Floyd and so many others have known.

Next Starhawk gets us to begin with the names, all people unfairly killed by the state. Floyd of course. And Hampton and Grant and Bland and Rice and Taylor and Wright and Castile and Grey and Garner. “Emmett Till,” murmurs someone, who then adds a couple more, not familiar to me, to the endless list. Phoenix throws in a refrain of indigenous names I have also never heard of. Others call out for the six million victims of the Holocaust, the innumerable ones who did not survive the Middle Passage, the countless more who were killed body and soul by slavery. My contributions are Fred Hampton (see the movie, Judas and the Black Messiah), Li’l Bobby Hutton (Black Panther killed in Oakland by the police back in the day) and Ethel Rosenberg (blazoned into my heart during my red diaper baby childhood—maybe Julius was guilty of spying; Ethel most certainly was not).

Eventually, though immunized, I find myself obsessing about Covid in this closed space, crowded with the children and lots of adults, young and old who don’t know each other’s immunization status. I leave immediately when the ceremony is over, while others who are braver offer watermelon and ice cream, and stay to hang out.

Next comes packing, bed and such a deep sleep that when the 6 AM alarm goes off I return from a faraway land, rested. And cogent. And able to navigate the driver through the chilly morning scenery back toward Minneapolis. And willing to take over the wheel as Second Designated Driver, when the first one needs her nap. And we find a parking place right next to the Governor’s Mansion, where our final demonstration will soon begin.

We have blown-up posters to hold up, including two of my own grandkids. We have photos of kids from around the world, to tie to the fence. We have multi-colored chains of hand-folded origami cranes and butterflies to drape from the spikes at the top. We have our 1000 Grandmothers for Future Generations banner, and our Stop Line Three banner, and our length of silk, a bouncy buoyant pure blue stream now shortened and easier to handle.

We meet in person the magical grandmother Ellen, who was the one to arrange for our thirty-one chairs at the Welcome Camp. We thank her more than once, and she cries each time. How pressed they are in Minnesota, she tells us. How much they need our company, our support.

Other Minnesota grandmothers arrive, native and not. Folks from MN 350.org and Minnesota Interfaith Alliance of Light and Power. One live reporter is present, weighed down with camera equipment.

We meet Great Grandmother Mary, who had urged us to make the trip, but who couldn’t come out to the Welcome Camp to greet us because of car troubles. We take in the four generations of her family, all dressed in indigenous red skirts—herself, her daughter, her grand-daughter, and her ten-year old great grand-daughter, who eventually sings for us all, a shy and tender melody about nature

Our own native spokeswoman, Pat St Onge, calls upon us to care for the Earth—she is our Mother, after all! Phoenix speaks for Migizi, informs us that it is the only true home she has ever known, and assures us with quiet fervor that they will stay the course no matter what Enbridge does. Madonna Thunder Hawk, Lakota Grandmother OG, tells the young people how much she admires them, and how we grandmothers will always have their back, as our elders have had ours, just by being present.

Joe Meinholz, a white kid from Interfaith Power and Light, talks about his own grandmother being with him when he took a fall on his bike as a kid. He came up to her bleeding from his face. “Where does it hurt?” she asked him. “Here, right here!” He points to the left side of his forehead. The crowd laughs—such an obvious question.

And then Joe’s voice cracks as he tells us that is exactly why he needs us here—to ask him, where does it hurt, and to care about the answer. Because Minnesota, he informs us—the place with the largest disparity between black and white in the whole entire country—is hurting. Because this pipeline that cuts under our waters and through our wild rice territory to bring the dirtiest form of the very oil the burning of which keeps sending the temps sky high, the waters rising, the western states burning and parching, the climate refugees mounting into the millions, the limiting of the future for all our children and grandchildren—we all are hurting. (Forgive me, Joe, for adding to your words. This has become my own rant, as it does so often at home.)

So many times, when a Minnesotan has spoken to us, that person has shed tears. Now, throughout this rally, my own throat expands, my own eyes are wet.

The Coordinating Committee members lead the group in Holly Near’s 1000 Grandmothers, the song that inspired our name. We include my favorite verse:

An old woman holds a powerful force

When she no longer needs to please

She can cut your shallow life to bits

And bring you to your knees

We best get down on our knees

I always mimic slicing downward angles with a knife in both hands when I come to that highlighted phrase, so on a grandmother’s short and tender video of this event (https://vimeo.com/558779216) that is exactly what I’m doing under my cowboy hat, no song sheet in hand even though everyone else has managed to find one. A hot mess while the trip comes to its conclusion, just as I was going in.

Exhausted again, and weighted with worry for these beautiful courageous Minnesotans as they sally forth to risk life and limb in this epic struggle, I drive the van to the airport and turn it over, then trudge with two other grandmothers through the huge airport to join the long security line to get onto my flight home.

Three of us make it to the departure gate with a few minutes to spare. We cruise for food and drink, ending up with burritos which we save for the flight, and identical tall IPA beers, which we drink immediately. Suddenly we expand into fun and jokes, affection and declarations of fealty.

I gaze at the faces of these two slight grandmas whom I had barely known at home, but who are lifelong companions to my spirit from now on. Each with her distinctive weathered fashion statement is lovely, absolutely lovely—what else can I say? We’ve done it all and emerged intact, into conviviality before we have to fold ourselves into our separate cramped spaces, masked and strapped, for the flight home.

I am frightened for all these young folks, emerged from an environment already degraded by oil, by gas, by colonial culture. Thousands more have joined them since our trip. The sheriff’s cops are bullying them all, diving with helicopters to kick dust in their faces, arresting hundreds, using tear gas and rubber bullets, keeping them in custody longer each time. I worry about the physical and legal risks of going toe to toe the with the ruthless Enbridge giant.

My fear, though, is not the point. The protestors’ determined courage—through all their own tears and pain—that is the point. And as for ourselves, as grandmothers? Accompaniment is the point. For as long as we can, however we manage it. This is who we are.

And so, since I’ve been home I’ve signed every electronic petition about Line Three that comes my way, and sent numerous letters through the internet to all the major players. President Biden, of course, but also phone calls to CEO’s of Citibank, Chase, Bank of America, the Royal Bank of Canada. In the middle of the night my husband and I are among the singers who keep company with those painting in the middle of the street’s pavement by our local Chase Bank—Water is Life! Defund Line Three! I have a bunch of artistic posters on the same themes, and I’m perfecting my skill at getting them up on fences and the walls of buildings, including those banks, out in full view. This I do during the day, telling myself I wouldn’t mind being arrested. I wouldn’t mind jurors who have to listen to my explanation of why I am engaged in this blatant illegal conduct at my advanced age, to see if they can tell me that what I am doing is wrong.

Yep. I seem to have reached a familiar conclusion once again—struggle in the midst of pessimism and despair? It makes me tired; it makes me cry. And, though I will never know how much effect my individual actions contribute, it makes me happier than passivity. Migizi Will Fly.

The post Migizi Will Fly–A Grandmother’s Journey to Stop Line Three appeared first on Barbara Rhine.

February 17, 2018

Amsterdam–Summer 2017

We approach Amsterdam via a calm and simple train ride, with a club car that has decent snacks, good beer and coffee, and a slender grouchy fashionable entitled German woman, set up in the corner of the clickety-clacking vehicle, who keeps ordering her daughter in a loud voice to buy food. No one, even the daughter, seems to mind. So I decide I don’t mind either, and eventually we arrive in Amsterdam.

Our Turkish taxi driver thinks his President, Erdoğan, is doing the right thing by going hard against anyone he believes was connected to those rebels, because, after all, they killed people didn’t they? So what if the dictatorial tactics include mass arrests, torture, removing whole swathes of people from the civil service and the judiciary,…yet the driver seems nice. For once in my life I say nothing. Maybe the three and a half weeks of vacation have actually calmed me down?

Our destination is HOTEL V. Fifth in a series? Five centuries old? Its sign is a modern abstract of a coat of arms that seems to be two lions on hind legs scratching, growling, fighting each other. Kinda like a lot of the world…

HOTEL V, according to the tiny map they give us, is in Nesplein, on a tiny alley a block off the Grimburgwal canal. Our room is quiet and medium-sized and nice enough. The fancy restaurant does NOT include a breakfast buffet, for the first time since Switzerland. Yet the Hotel V costs more per night than any other lodging on the trip.

Amsterdam is known for its marijuana and its prostitution. Does that mean it draws more tourists than Berlin or Prague, even Paris? So supply and demand drive the prices up? Yet the town seems so wholesome in the early evening light.

Grimburgwal Canal

The Grimburgwal is peaceful, with its rhythms of ripples amidst varied breezes that reflect, then lose, then re-reflect amidst the lovely ducks that paddle around, the tour boats, the edifices that loom above. Each structure has a large hook suspended on a pulley, so that furniture and other large objects can be moved up and down on the outside rather than through the narrow interiors. When night falls it is the various lamps, on the streets, in windows that get reflected, doubling their warm and sparkling glow.

The Grimburgwal at Night

During our walk around on the first evening, I spy a place where the youth are lined up to buy their joints. Some even smoke the thick spliffs inside, while they sit with their wine and beer. It’s all loud and young and formidable so I wait until morning, make my way back into to that rear counter, where I boldly request a joint with CBD’s in it. (It’s the CBD’s, I have learned in Medical MJ California, that can relieve the pains associated with arthritis, inflammation, bad knees, and on and on.)

You have to go to a pharmacy to find your CBD’s, the guy behind the counter informs me. Fine. I go in search of a pharmacy and soon I see one, with a marquee that features the stylized cannabis illustration I’ve already spied on candy wrappers and cookie bags in corner stores. Which cute little packages, btw, contain only products with hemp, nothing that gets you high. And the pharmacy? There you can get CBD’s, yes. If you have a prescription. But none of their CBD products contain THC. Just in case you want to get high. Which, believe me, by now I do, because after all, isn’t that what Amsterdam is for?

I stroll into what looks to be a cannabis shop located near the top of the Red Light District, as the Woermostraat area is also called on our map. Red Light District, in big letters! This place has no coffee, no chocolate, no beer, no brownies, no packages with an emblem of any kind. Just an immaculate glass counter and small plants.

There I ask the young man behind the counter my simple question—can I buy some marijuana to smoke that has both CBD and THC in it?

In response to which he informs me emphatically that marijuana is NOT legal here. And it is NOT legal in Italy, which is where he comes from. And even in California it is NOT legal, and by now he is yelling. Well! I’m from California, I yell back, and medical marijuana has been legal there for twenty years, and recreational marijuana is coming in 2018. He pays zero attention to my lecture

No! He stands his ground. Marijuana is legal in only one country in the world, and do I know where that is? At this point I really want to walk out of there.

“Ecuador!” he shouts before I can even think about it. “Evo Morales! And he’s the only one! And your federal government can swoop in and shut down all that stuff in California whenever it wants to!”

I find myself nodding because he’s actually kinda right, especially since now Jeff Sessions, who in his wisdom has announced that marijuana is harmful to us all, is in there as Attorney General.

The Dutch don’t use it by and large, they don’t like it, and they look down their noses at those who do, my Italian friend continues, more reasonable in his tone now that I have decided to listen. Marijuana, is tolerated in Amsterdam just like in California, he tells me, because of the taxes it generates. And the same goes for prostitution.

Okay okay, the guy is intense but he is actually also making sense, so I give up on the CBD’s and ask him where, if anywhere, that’s not a dark bar reeking of tobacco, can I just sit and smoke a joint?

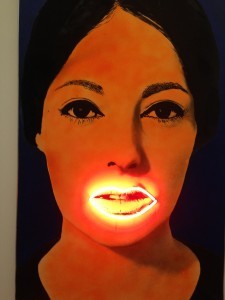

Seen Later, at the Stedlik Modern Art Museum

Sweet and kind suddenly, he says that someone who looks like me (viz. elderly white woman) can pick a quiet place. One of those insets along the canals, or a bench in a square. And if the police do stop me, they will just ask me to put it away and move on. AND he knows of a café with the good stuff. There is scaffolding on the outside of the building, but the shop is in there.

He writes arrows on my map, and we set out to locate it. Eventually, after two young women send us all the way around a long block when it would have been just around the corner if we had taken the opposite direction, we find the scaffolding. But there is NOT a place behind it, even closed, let alone open.

So I ask one of the directionally-challenged girls where there is another place to buy. She informs me with a disapproving look that she’s not sure, because she’s given the drug up.

Luckily I now remember that the Italian guy had marked a second place on my map—a mother-daughter operation, he said, but the product is not as good. We follow more of his arrows, and, miracle of miracles, we FINALLY find it.

I purchase one huge spliff,stuffed with coarse-looking weed, take my product trot off to a quiet old neighborhood across the Boerenwetering canal, which the Italian guy had also recommended, to get me away from the Red Light District.

I find a bench on a peaceful corner where the infrequent passers by look Dutch…and? The stuff is raw on the throat, but one must be tough as a tourist, right? I puff away. . . And?

It’s nice. I’m happy. The area is peaceful; the people are lovely, especially the ones on their bikes. Some riders have children with them, seated in various places—on the back fender, on top of the basket in front, in a container clipped onto the rod under the handlebars. They wear helmets or they don’t. With or without a child, the cyclist is upright and alert, and often whistles or hums as she or he goes along. The bikes are frequent, their drivers determined.

While under the influence I conclude that Amsterdam’s marijuana is definitely more a virtue than a vice.

Amsterdam is Pretty

But what about that Red Light District? Three times we stroll through it, once in the morning of the marijuana search, again later that afternoon, and of course, at night. Each time the displays behind windows of actual human female beings, in their close decorated spaces with their wide open decorated bodies, are more disconcerting than erotic for me. I remember that twenty years ago in this same city a live show with actual intercourse stimulated intense desire. But now all that is missing.

More than once I see a door open, each time to admit a young white man/boy who looks like a student on break. I can’t help but visualize what comes next. Disrobing, him with lust, her with boredom. Engaging physically. And afterwards? The kid would leave quickly, a bit embarrassed, maybe even ashamed. The woman would shrug, clean up, and get into position to attract her the next encounter.

What has happened, have I become a prude? Whatever, I do understand that it would not be better to put them—or, more precisely, one of them, the woman—in jail. . .

On the second day, after a breakfast finally so ordinary I can’t even remember it, we split up and I head out for the famous museums. The line in front of Van Gogh is daunting, the Van Rijk museum familiar from twenty years ago, so the Stedelijk Contemporary Art Museum it is.

Generous, full-blooded, intense and very female, the paintings impress and jumble together at the same time. I can’t even be bothered to remember the names of the artists—a sure sign that home is pulling at me, the journey nearing its end.

I emerge into the sunlight, start the long walk back and at the height of my fatigue with the tramping, my cell phone rings and it’s my husband telling me that I have to come where he is, right away. He had struck up a conversation with a passer-by who happened to be black, and the guy had told him about a celebration of slavery’s end that happened to be now, this very day and hour!

I haul myself into the hotel, they call a cab for me, and the driver takes me the edge of a large open space that must be Oosterpark on my map. He informs me with a bemused look that there will be good falafel and kabobs nearby.

But when I find Walter and we get into the park, there is nary a typical Middle Easterner in sight, because suddenly just about everyone is black. Dark-skinned black. Women are decked out in long dresses that flow with bright colors. The men sport vivid designs on their shirts, scarf strips, and even shawls. The children are quiet and respectful; the greetings among friends and family are elaborate and heartfelt.

Eventually someone informs us in perfect English that the folks here are descended from the formerly enslaved Africans of the Dutch republic of Surinam. According to my phone Surinam is a teeny-tiny country on the Northeastern coast of South America, but there are so many Surinamese listening to music in the huge field next to us that we are not even tempted to get close.

Eventually we locate a procession of percussive sounds that emanates from a smaller inside space. We edge into the dense crowd, and near the center we crane our necks to glimpse a substantial group of male drummers and swaying female singers. Concentric circles of audience shuffle in time with elaborate patterns of intricate steps. Difficult but not impossible to follow. Or so I believe as I imitate the nearby women who seem to pay zero attention to me as they dance. Fun!

We leave and keep walking. A guy or two has a beer in hand, but pretty much everyone indulges only in water or soft drinks. Varied scents of meat and vegetables prick at our nostrils, but the lines are long. We pick the shortest and end up with cobs of corn on sticks, lathered with butter. We are happy.

At last we come to the statue that commemorates the end of slavery for the Surinamese. Adorned by offerings of flower bouquets and garlands, it depicts a determined group that engenders a girl, upright and clothed in real fabric for this occasion, who in turn metamorphoses into a goddess with wings, her long body and outstretched arms ready to ascend to the sky.

The sign explains: “First all the slaves were ‘freed,’ but next they were required to work an extra seven years (!) to compensate their owners for the loss of property (!!). This holiday in early July is to celebrate the end of the transition, the beginning of true freedom (exclamation points added).”

Later as I tell the nice (white) guy at the lobby desk about all this, I notice he has a troubled look. Oh yes, he says, he has been to this place himself on this day in the past. Not too many white Dutch out there, right? Yes of course a few, but the Dutch still have so many problems with all this.

When asked for an example he turns his computer toward us and brings up a bank of photos of drunk white Dutch men celebrating Christmas as grotesque black-faced parodies of St. Nicholas.

On day three the same helpful hotel employee gets us tickets for 11 AM at the Van Gogh Museum, instructs us on where to catch the tram, and we are there only fifteen minutes late which doesn’t matter, so we get to bypass the line and walk right in. Van Gogh is so wonderful that his art need not be photographed, let alone described with words, as far as I am concerned. I wander the floors thrilled to stare unencumbered at the multitude of his works.

Van Gogh–Just One Picture

We emerge happy and hungry, and eventually settle at a sidewalk café where we sit almost touching shoulders with those on both sides of our narrow table. Walter orders a quiche that is so beautiful when it arrives with its sweet scents of cheese and mushrooms that two Spanish-speaking women tourists tell us in English how much they wish they had chosen the same.

Yum!

We eat, and I stroll around the corner while Walter pays the check. Out of nowhere comes a cavalcade of nude bike riders! Stunned, I can’t even get my phone out to take a picture until near the end, but there must have been at least eighty in the group. Mostly men, so more penises out in the open than I have ever seen in my life.

Were They a Mirage?

Without my one pic for evidenceI would wonder if it had all been a weird and feverish dream, but no. This was just a nude bike ride in Amsterdam on July 1st of 2017. Must be a back story, but I do not know it . . .

That evening we head back out on the same tram to the same area for a concert at the Amsterdam Royal Concertgebouw. First we eat, of course, in the famous hall’s café. I have smoked salmon with capers and good rye bread and a touch of salad and a glass of white wine, all of which makes me ridiculously happy.

Amsterdam Royal Concertgebouw

As for the concert, it seems out of another world altogether. The hall is huge, the giant organ behind the podium festooned with flowers. The Amsterdam Sinfonietta, a relatively small summer orchestra, seems dwarfed by the expanse. The featured star is Martin Fröst, a Swedish clarinetist who descends a staircase from high up into the space behind that incredible organ, so that he seems to be coming down from the clouds. He approaches conductor Candida Thompson, and their bows to one another constitute a dance of greeting.

The music swells to fill all the space and Mozart’s Clarinet Concerto in A has never sounded more sublime. (Also Brahms Waltz and 2 “Klezmer” dances composed by father Göran Fröst)

The next day is the final one of our month-long European trip. We decide on a bus ride into the countryside, which is flat and wet, with a prim and proper beauty. It must be reclaimed from the sea, but there are no dykes in view. Excerpt for the motor vehicles the area could be from an earlier century in its unbothered simplicity.

In line for a ferry to a town where we can catch another bus back, in some amazement that that such a hidebound place would be so close to the free and easy city, I ask the ticket taker—“so who actually lives around here?” He beams, and tells me he lives here, and has done so for his whole entire life!

Peaceful Countryside

The Author with a Proper Dutch Woman

In the afternoon we go to the Verzetsmuseum, aka the Dutch Resistance Museum, for one final World War II experience. It is in a building with a star of David embedded in the plaster triangle above the door. Inside is a series of spaces, entered through narrow doorways, with displays in various diminutive square and rectangular spaces. Photos, newspaper articles, documents, both personal and official, the accompanying text has a forthright honesty about the difficult choices that had to be made once the Nazis occupied the city. Accommodate and cooperate? Lay low? Resist?

All three alternatives are explored. A collaborator is imprisoned after the war. Resisters are regularly shot by German troops during the war. The Jews, as usual, have been shipped off to be cremated. No wonder most people found themselves to be cowards under those circumstances and put their heads down in the hope that eventually the Nazis will go away. The thrust of the exhibits is that this is exactly what the majority of Dutch residents did.

Further, the text confronts the weird but ubiquitous fact that, for at least a generation, little or none of this horror was even alluded to among friends and family, let alone discussed openly within the culture. So often this is what the human being does with trauma—shove it down down down to the deepest part inside, with a desperate fervent hope that it never has to be gone through again.

Which doesn’t work, it seems to me. Which perpetuates the cycle, which, which, which…why are human beings so cruel and perverse in the first place anyhow?? AU REVOIR WORLD WAR II!! Good by and good luck and may you stay in the rear view window now, forever.

Statue of Rembrandt in Amsterdam, Discovered on Our Last Night

So it’s off late on our last night to a gourmet seafood restaurant in a neighborhood I can’t be bothered to find or name on our tiny map. The place has white tables, white chairs, white-jacketed waiters. With much fanfare delicious oysters are on offer, along with other platters that taste of the sea and contain items so unusual in the U.S. that I can’t name them. This mysterious final meal, in a hidden neighborhood with unknown foods is the perfect ending, before our inevitable return to familiarity the very next day.

The post Amsterdam–Summer 2017 appeared first on Barbara Rhine.

Berlin–Summer, 2017

The train ride to Berlin from Prague is long and easy. The taxi from the Hauptbanhof to the Adina Apartment Hotel, near the Hackescher Market in Mitte, is quick. The neighborhood is supposed to be lively, including nightlife 24/7, but it looks so staid that the driver has to reassure us.

Our room on the sixth floor turns out to be an entire small apartment designed in unadorned clean lines. Our living room window overlooks an intersection of small roads with light car traffic. Pedestrians flow together and apart in an intermittent pattern. Most walk singly; some are pairs or small clusters with an occasional dog or kid. Every once in a while folks stop to chat, but mostly everyone heads straight on, determined to reach a destination.

And there are bikes, one or several of which are in view at any given instant. Cyclists are upright, equipped with briefcase for the day and/ or shopping bags for the evening. Quick and efficient, they pedal into and out of the intersection from all angles.

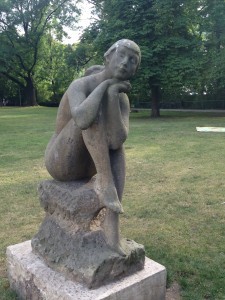

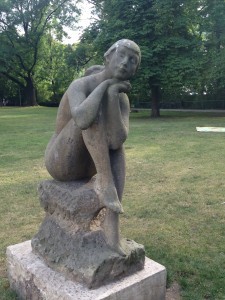

I go out to find a place to sit for a half-hour meditation. The small park just past the intersection is a quite deserted, a bit unkempt and certainly unlit, with darkness beginning its slow summer descent. The sculpture in roughened concrete of a woman seated on a cement bench has a commodious space beside her, so I am tempted, but a bit further on twisted concrete figures with vague features emerge from the ground, agonized.

Does She Want Company?

No sculptor’s name, no plaque that explains anything, just the grim reminder. Of what? The Holocaust? The hand-to-hand combat in this area as World War II wound down? The general angst of life? All of the above it seems to me.

I find a bench near a tram stop where I am more comfortable, and the next day I return to that area for my half-hour walking meditation. Two sidewalks bisect a planted rectangle in front of an entrance to what appears to be a school for young adults. People alight from and embark on the nearby trams; it’s an active place. But when I look into the dark vegetation, again there are the mementos.

This time one cement figure is a woman on her knees, hands behind her back, in chains. On the other side is a Giacometti-style duo, with the standing figure delivering a severe a punishment to the one that’s down on the ground.

Still, throughout our stay here I walk on this path and I sit on this bench, and I enjoy the peaceful swirl of what used to be East Berlin around me.

On our first full morning we stroll to Alexanderplatz. At this hour the huge square is quite empty. The first tourist attraction we see is a two-day, hop-on-and-off-the-bus-whenever-you-want-to-tour. We hop on and settle on the top level in the fresh air, right behind the guide.

He is a sorta scruffy counter-culture type middle-aged German guy, who draws our attention first to the Fernsehturm, a TV tower built by the communist German Democratic Republic (GDR). The needle, beneath which is a revolving restaurant, forms the highest human-made point in Germany. Our leader does not talk about the food, or even the view. Instead he describes the way the GDR used the tower for surveillance of everyone and everything, We never consider going back there to eat.

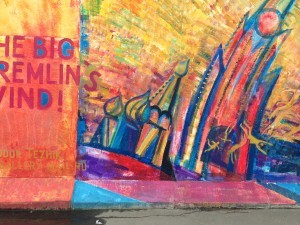

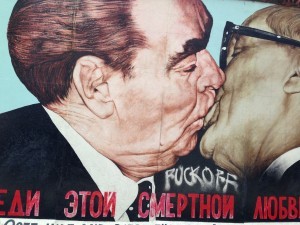

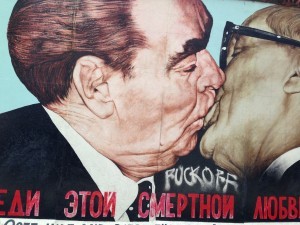

Next come the fragments left from the Berlin Wall, which the guide tells us are the largest tourist draw in the entire city. The sides of the Wall that fronted West Berlin were said to be the longest canvas for continual art in the in the world. Most of the Wall has been destroyed since 1989, but when we descend from the bus to stroll along what’s called the East Side Gallery, colorful murals still adorn an impressive length of what’s left.

Most famous, I suppose, is a huge painting of a kiss between Leonid Brezhnev (head of the USSR) and Erich Honecker (head of the GDR) from a 1979 photograph taken at the 30th anniversary celebration of the GDR’s founding. I could not take my eyes off this thing. What can I say? I have no idea what actually went on between these two, but this kiss, the one in the painting? It is sensual, just about to the point of lust.

Riff on a 1979 Photo that Celebrated the 30th Anniversary of the Founding of East Germany

Our bus takes us through various areas of what had been working class East Berlin. Our commentator mentions Rosa Luxembourg, and a street and square are named after this labor leader who was executed in 1919 by the German government.

Occasionally he points out two parallel tracks of narrow rectangular cobblestones in a darker shade which mark portions of the Wall’s original location.

As for modern Berlin, in what used to be the Western sector, both days on our bus give me the impression of an immense, stony, glassy business area under constant construction. Its scale dwarfs the people on the street, and corporate brands, especially Mercedes, are featured high and huge and loud and clear. The magnitude of all this leaves me a bit cold .

Modern Berlin

The guide tells us about a model replica of Berlin, crowded with moving toy trains, so eventually we hop off our bus and take on the depth and breadth of the huge shopping mall where this thing is supposed to be.

On and on go the displays of what you can buy, but we know about all that from the U.S., and refuse to be distracted. Finally we locate the hidden elevator to the LOXX BERLIN and ascend to the top floor, pay €12.90 (cash only—don’t be fooled when they tell you Europe accepts credit cards everywhere—not true) to enter a large darkened space that houses an old-timey set of the city in miniature form, with trains moving in and around iconic Berlin landmarks, and planes taking off and landing at the airport.

The exhibits are supposed to be interactive, but I can’t make anything happen with the buttons. The effect of the whole thing is sorta mesmerizing and sorta hokey at the same time.

Fresh from the Triumph of Capitalism in its myriad forms, we return to the Adina and I set out for a walk on my own. In a hidden corner of a nearby park with bunnies in a desiccated small field, I stumble on a majestic statue of Marx and Engels.

Marx on the Left; Engels on the Right

Black and white photos have been etched into a nearby metal wall, where they cannot be totally defaced. These include a couple of scenes from the American civil rights movement, which must have been supplied by the Communist Party USA once upon a time.

All of which makes this “red diaper baby” oddly happy. I like the statue with no tourists, and I like it even better when a family of tourists perches on Marx’s lap and leans up against Engels’s chest.

Marx and Engels with Company

In the middle of the second day we hop off our bus to go to the Hamburger Bahnhof Museum of Contemporary Art. The bus driver tells us it’s “right over there,”but we undergo a half-hour march, with much uncertainty, even to get to the place. Finally we walk up a massive avenue to a massive front door with a massive wooden blue man sitting there, pensive, his elbow on his knee, his palm cradling the side of his head.

The Blue Man Welcomes You to the Bahnhof Museum

All this makes us hungry, so instead of going in we hang a right, to check out the museum café.

We sit and chat, and eventually a waitress shows up. She gives us menus, retreats, and eventually she shows up again. If we have questions by now we’ve learned to guess at the answers. Because so far in Berlin restaurants when there are such inquiries the wait person says oh, just a second, and disappears.

Eventually, when we have supplied our own answers and figured out what we want, the waitress returns. Orders given, orders taken. Then a LONG pause and finally the food comes. Again our experience here has been that no one asks whether everything is all right, and if it isn’t, you have to work at getting anyone’s attention. But everything is fine. Next after a LONG pause, finally the dessert comes. And after another LONG pause, the check arrives, and believe me, by now we are ready to pay at once.

By the end the customers are as relaxed as the wait staff, because there’s no other choice. I come to like all this, so different than the way our American restaurants run. Then again, we are on vacation. We have nothing but time.

The first room of the museum has massive paintings by Anselm Kiefer and Andy Warhol. Kiefer’s work covers whole walls and portray Jewish dispossession in a blur of fragmented brown and gray.

Anselm Keifer, Telling Us About All The Books That Were Lost

But it’s his three-dimensional full-size freestanding gauzy dress that sticks with me. Pink and soiled and pierced by shards of glass pane, I expect this to refer to a specific woman, or maybe even women in general. But no, it’s more than that. The title is “Schechina,” the Hebrew word of the feminine aspect of G-d.

Kiefer’s Schechina Seems to be Under Attack

Warhol is on full display with a large Marilyn Monroe and another of his signature colorful flowers. What draws my attention most is his smaller “Hammer and Sickle,”in red and black, which I have not seen before.

Warhol’s Hammer and Sickle

The entire place is cavernous, with lots of zones to traipse through, and many odd displays to contemplate.

A life-size model of an art nouveau apartment from the 1920’s makes me chuckle because it’s so similar to our very own Adina apartment.

The central vaulted space of the old railway station creeps me out a bit. In a corner are young women with a questionnaire designed to ascertain which people would keep their word, no matter what, and to give them a way to connect directly with each other if they wish. I don’t even want to see if I qualify, let alone be in contact with the others.

What I like the best is a large dark room with squares of light on the floor that contain shimmering shapes of color and form. These intervals lead back into pre-and sub-consciousness, and comfort me on a level that is not analytical. I didn’t even write down the name of the artist, and later I could not find it anywhere.

On the third morning the Adina’s breakfast buffet—eggs cooked to order, bacon and sausages, smoked salmon, bagels and rolls, goat cheese and berries, juices and teas and coffee choices, pastries to the nth degree—leaves us stuffed and confident.

Of course we can handle bikes in Berlin! And right in front is the easiest bike rental I can remember. The price—as with everything about the Adina—seems reasonable. €12 for 24 hours, paid in cash. Each bike comes with three speeds, thick tires, hand and foot brakes, and a huge chain and lock—what’s not to like?

We take off and immediately understand that we are the least efficient bikers on the road. Everyone else knows where they are going and they pedal quick and smooth to get there. We typically ride at an uncertain pace, stop a lot to figure out where to go next, and no doubt are a nuisance for other riders. Nicely, no one complains.

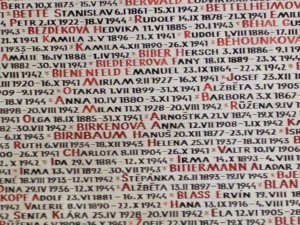

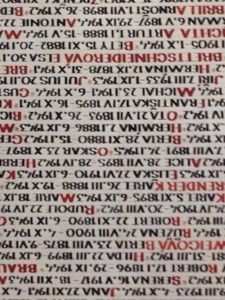

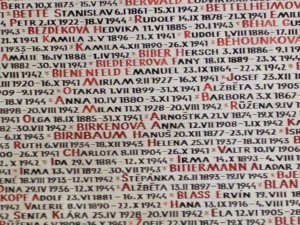

We go to the Neue Synagoge first thing, because it’s close. Security tells us to park the bikes across the street, security lets us into a locked door, security gets us through a metal detector and security searches my purse. Once inside there is printed material with facts like this:

Built between 1859-1866, with a main hall that seated 3,000, this was the largest synagogue in Germany.

The Jews were not required to wear distinctive clothing or stay within walls; in fact the rabbis played a political role in the life of greater Berlin.

Due to an unfavourable alignment of the property, which could not be changed, the building’s design required adjustment along a slightly turned axis.

Albert Einstein played the violin here in 1930.

AND? The first woman rabbi in the world, Regina Jones, ordained in 1935, was here! Not permitted to give sermons from the main bima (altar), she nonetheless performed weddings and presided at the smaller shabat services. Before the Nazis ruined it all…

…by rampaging through the whole place on krystallnacht. (Amazingly, the local police chief managed to get the thugs out, summon the fire brigade and save the building from being burned.)

…by choosing the Jewish New Year season in 1940 to requisition the main space for a leather warehouse. (The few services held after this were in side rooms).

…by causing a war that brought allied bombers to Berlin, who destroyed the whole building.

…by yanking Jews out of their homes, requisitioning their property, deporting them to concentration camps, and gassing them.

Regina Jonas, for example, had to fill out a declaration form that listed her property, including her books. Two days later, everything was confiscated, and the next day, November 5, 1942, the Gestapo arrested and deported her. She died in Auschwitz at the age of 42, in late 1944.

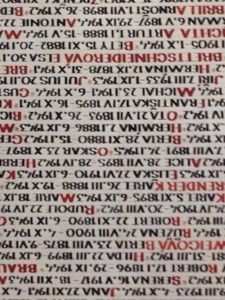

Throughout the neighborhood now are scattered occasional square golden cobblestones that list a name, date of birth, date of deportation and date of death. Thus, a few are commemorated.

Next, preoccupied by all this, we bike across the Spree River to see the “Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe.”

Once in the vicinity there is no way to ignore this extensive area (4.7 acres) packed with gray metal coffin-like boxes of slightly varied sizes. These march off in bleak rows, separated by level aisles in one direction, and undulating along small hills in the other. The slate surfaces are smooth, soothing to the touch if you forget what they are about.

Memorial to the Murdered Jews

I wander in, sense that I could get lost there, and edge back out. The setup conveys an unending suffering, a relentless grief.

So Many Are Gone

We bike through the Tiergarten, the main park of Berlin, which even in full sunlight, like the other parks in Berlin, seems neglected in places, and a bit foreboding. But maybe it’s just my mood…

The Holocaust Lives On

After all this and a break at the Adina we head off to find an interesting place for dinner. We bike from the Adina across the Spree River again and eventually stumble on a café that is a bit down and out and more friendly than most, which is enough to entice us in.

I settle into the casual pace of service and stare at the passersby. Suddenly I realize that every single Berliner I see—men and women both—are wearing black. Inky fabrics cover spare and zaftig frames alike. Whites and colors, if included at all, are only for accent.

The café is communally owned, the vibe relaxing, the food ordinary and nicely inexpensive. The owner tells us there is a jazz quartet tomorrow night that has been playing there twenty-five years, and we resolve to return in the hope of good music and conversation about what it was like in the olden days, before and after the Wall.

So the next evening, in the receding solstice light, we find our way back to the place on foot, and descend down two sets of concrete steps and through various concrete rooms until we arrive at the innermost claustrophobic cellar of all. Maybe this was one of those adventurous clandestine clubs during the GDR? Now the air is close, the stone walls and floor dingy. I wonder how we would all get out in an emergency, then resolve not to think about that again.

The music turns out to be old white-guy Dixieland jazz, which can be good in fact, but this was pretty awful. During the break I approach the trombonist, who is talking with a woman friend. She stares at me as though I’m intruding, which perhaps I am? Perhaps it’s a rare assignation between sexy sexagenarians, right there in front of everyone, and they need their privacy?

Nonetheless, I interrupt nicely with my question planned to break the ice—“Excuse me, but we were wondering. Could one play jazz in East Berlin before ’89?”

“Yes,” the man answers, “But I didn’t know much about all that. I was always in the Western sector.” His manner indicates that I should have understood this from the getgo. Next he returns to his private conversation, and oh well.

On our last full day, in the midst of a massive downpour, we make it to Kreutzberg, originally a counter-culture center just west of the Wall and now reputed to be a diverse community. We take the train, marveling on the ease of public transportation in this city, then trudge down from the raised station, get lost, find the right direction and continue. Despite windbreakers, hiking shoes and one huge Adina umbrella, we get drenched.

We take refuge in the first coffee shop we see, which has black African youth hanging out in plastic chairs under the front overhang. Inside, counting the baby in a stroller, is the three-generation Arab-looking Muslim family that runs the place. We order coffee with cream and soft sugary pastries, and settle down onto wooden chairs next to a table with a plain white cloth.

Outside the young men linger, and the owners don’t seem to mind. When the downpour turns to drizzle, careful to throw out their cups and napkins, the kids get up to leave.

We head for a nearby park, and this one looks so desolate we turn back before we even get to the trees.

We return to the café, and by now there is a tall rangy well-into-middle-age gray-haired German guy, wearing black of course, who proclaims himself a writer. We ask what he writes, and I hand him a business card about my own novel, “Tell No Lies.”

“Yes!” he exclaims. “Exactly that! I write of the truth, all the way down to my last day, because no one will know the full truth until then.”

After that, as seems to be our pattern with Berliners and substantive talk, there’s not much more to say.

We set off on the long wet slog back to the train station. There everyone commiserates pleasantly about the rain. Small talk. Lovely.

That evening, after I have changed into dry clothes, meditated out in the rain, gotten soaked once more despite all precautions, and changed yet another time, we try another jazz place. This group, all white again, plays an intricate set of improvisations that are complex and austere and lovely. No blues-based inflection, though. Nothing that makes me regret leaving town tomorrow.

In the train station the next morning, when I find my European edition of the NYT, I ask the woman selling papers about the storm the day before. She has never experienced so much rainfall in one day, she asserts, and she has lived in Berlin all her life. And I realize that during the whole day I had seen people walking quickly, running, sprinting, biking, with few umbrellas, jackets or hats, racing through the furious rain to get where they wanted to go.

An intense weather event, heightened by climate change? In any event, this morning it is clearing, and we are on the platform in plenty of time to catch our train to Amsterdam.

The post Berlin–Summer, 2017 appeared first on Barbara Rhine.

Paris–Summer 2017

Karel Appel

Jet-lagged of course, and the weather is unexpectedly hot and humid for early June. Our apartment is in an ancient building organized around an outside courtyard, with a modern elevator, encased in plexiglass and big enough for two, three if squeezed. During our ascent to the fifth floor we spy old wooden stairs, strollers, doors, conversations, and then by some miracle after a twelve-hour flight we and our luggage are in. It’s a small place, but with three bedrooms, a narrow kitchen, two baths, one toilet, living room, dining room—everything the five of us, all friends, will need.

We are on the Left Bank, Rue St. Placide, near brasséries that turn into serious restaurants the closer you walk to the Jardin du Luxembourg.

Ah, Luxembourg, with its sensuous statues of unclothed Greek gods.

Lounging in the Jardin du Luxembourg

The thwack of tennis balls. The office party where everyone, still in business suits, is throwing boules. The chairs strewn about with people lounging and reading actual books…do you really let yourself appreciate how much relief trees and grass and flowers and shade offer for a hot day? Yes, at least while you are on vacation in Paris!

Coffee at the corner is immediately delicious. A few French words float into consciousness. Passersby are thin and casual; stylish clothes are displayed in each shop window. Intersections are a strange combo of circular and angular, so it’s reassuring that nearby there is a news kiosk with the International Edition of the NYT in English. I date myself immediately by inquiring after the Herald Tribune, which has been out of existence for, oh, maybe twenty years?

The evening brings cool; the strolling eventually lands us up in a restaurant with soufflés of light and air with a bit of egg and spice thrown in. And wine, of course–wonderful wine that’s not even that expensive.

After that we pass out, but luckily it’s when we get back to our place. The next morning it’s time to try the brassérie at the left end of our street. I order their “American breakfast,” which is delicious, as usual, and includes no fewer than four eggs. Only later do I realize that in the first twelve hours I have consumed six eggs, or seven depending on how many were in the soufflé!

One of us is a foodie, and he stocks the place with breads, cheeses, meats, fruits, cereal, everything we could need or want. Plus he cooks the best meal ever while we are there—fish stew, lamb shanks, huge artichoke, salad, pasta, good wine, on and on and even this list perhaps is a combo of the week we are there, because the food and the wine and the sparkling water and the coffee out and the tea in all become a constant comforting stream, with no beginning or end. I’ll be lucky if I get through this trip without a heart attack . . .

So you know how when you travel, the present trip is the most real and all the other journeys from your past are the deepest memories? Then when you get back, you wonder—how did you spend all that time? Well, the answer in Paris, after eating and drinking, is that we went to museums.

On the first full day it’s easy to make it to Jardin du Luxembourg again, where the Musée du Luxembourg has an exhibit that’s all Camille Pissarro. To my surprise, since I’ve barely noticed him all the other times I’ve seen his work, I like him. To my further surprise, he had anarchist leanings. Maybe that’s why his work has love of the countryside first, the peasants next, and also the women and children in his life, all painted with respect.

On the second day we find our way through a maze of streets and come out at the Seine, which was what we hoped for but had begun not to expect. We cross a bridge far enough to sit, stare at Notre Dame, and listen to accordion music. We stroll along the river by weathered wooden structures that exhibit wares old enough to match, from whatnots like egg cups to black and white postcards to posters of jazz artists from the fifties. We pick a brassérie that fronts the parallel road, which unromantically bristles cars and fumes and shouting drivers. Nonetheless, all food in Paris is blessed, and my croque monsieur fairly drips with its cheese and ham.

Next it’s on to the Musée D’Orsay and, after the obligatory stop in the Van Gogh (which rhymes with “cough,” I later discover in Amsterdam), we head straight for the Impressionists.

I have always liked them in the past, but perversely now I am quickly irritated with the male (which is to say just about all) Impressionists. Maybe it’s Trump and his pussy-snatching that makes me aware of Toulouse-Lautrec and his dancing girls; Degas and his ballet girls; girls, girls, girls, all for the delectation of the artist and his male friends.

I search out Renoir, whom I thought corny in my youth but grew to love more with each decade, and yes, I still love him. But then, just as I remember that years ago I first had this adverse reaction at a Chicago Art Institute Matisse exhibit with walls and walls of odalisques (French version of Turkish word for courtesan), I stumble on a Renoir odalisque. The traitor!

Of course here is the trouble with generalizations. Later in Amsterdam I run into a Matisse odalisque that I like. Why? She seems like a real person, not his fantasy desire.

Matisse

Odalisque

Amsterdam

Next at the D’Orsay I find Berthe Morisot and Mary Cassatt, two of only three famous women impressionists. They both do women and children who are real people for sure. So by the end I am happy.

Berthe Morisot

Young Woman Powdering Her Face

Mary Cassatt

Young Woman Sewing in Garden

Berthe Morisot

The Cradle

And the third day is for Musée d’Arte Moderne de la Ville de Paris, on Boulevard Woodrow Wilson? Who’s ever even heard of this one? Our friend Herb, that’s who. And after all, it’s time to go beyond impressionism, now way over a century ago. But when I get there I am back to noticing that the stories-high color triptych of French history, on all four sides of the atrium entrance, does not include a single woman. Not even Marie Antoinette? Joan of Arc? Simone de Beauvoir?

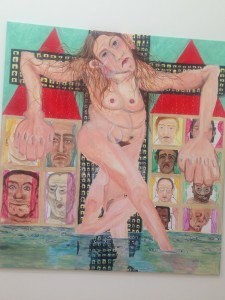

I wander several rooms of Karel Appel, Dutch abstract expressionist born in 1921. His women are compelling, though I am not certain he likes them much. And a series of wooden sculptures are so playful that I have to snap pix for the grandkids.

Karl Appel

Finally there is Paul Armand Gette, a sculptor/photographer born in Lyon in 1926. Okay, so Gette has a portrait of a woman’s lip-ringed mouth so large that textured skin gives way to smooth lips gives way to a dark cavern framed by white teeth where everything swims in saliva. Since this is how we are, male and female alike, I am fascinated.

After this is Gette’s centerpiece: a photo series Le plage…été 1973, and these pix of the young girl on the beach, many just fragments of her body, but all in a bathing suit, are appealing. He snaps a shoulder and a budding breast, her butt with its own cleavage, her legs going up into her crotch, and he claims this is all okay because he has her permission. Really? Somewhere between thirteen and sixteen, she does not know yet (we hope) what the world will do with this information. Isn’t this really an excuse for a bit of pedophilia?

And am I forever going to be this irritable, this bothered, this endlessly serious? Probably, given my advanced age. But also probably not, given my advanced age …

OMG, how could I almost forget to mention the French Open? Roland Garros! The red clay! A gauntlet of security checks, followed by coffee and croissants and fruit before we even got to the courts.

Hanging Out at the French Open

![IMG_5019[1]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1629963005i/31833859.jpg)

Flowers at the French Open

There were my elders—Navratilova, Davenport, Austin, Clijsters—playing an intense doubles final. There were the male equivalents, (less well-known, at least to me) cavorting about by literally running around the net during one of the points, joined even by a ball girl. Lunch, champagne, instructions on how to sneak beer or wine into the stands.

Food at the French Open

All this before the women’s singles final. Halep (Simona, the fans chant! Simona!) v. Ostapenko (Jelena! Jelena!) They pound through points that are crazy intense on what is supposed to be the slowest surface for tennis.

Jelena! wins her first Slam, after three sets.

Ostapenko and Halep, Women’s Final 2017

All this is capped off by the men’s doubles final—African American Donald Young and his Mexican partner (Mexico! Mexico!) who lose after a good solid three sets.

We’ve had such a good time that for an instant we actually want to buy a scalper’s tix for the men’s final the next day. A mere $600+ each the guy informs us, and he means it. If the seats exist, that is. On to Switzerland. (Mountain Alps! Mountain Alps!)

The post Paris–Summer 2017 appeared first on Barbara Rhine.

February 14, 2018

The Swiss Alps–Summer 2017

Before we get to the mountains, allow me a word or two about Swiss trains: Clean, comfy, and always on time. So the schedules give maybe five minutes to change trains. But it’s not always easy to find the new track on the signs. But people speak enough English to try to help. But sometimes they give the wrong information, so you should have looked at the signs more carefully. Then somehow you’re on the new train just before it rolls. So it works. But not without stress.

And any travel account has to mention food. Swiss food is fine. Not a particularly distinctive cuisine, but fine. At our hotel breakfast buffet (free with the room) there is a sign that requests guests to put no more on your plate than you will eat. Because the Swiss, relates the placard, believe it is wrong to waste food in a world where people go hungry. I’m from the era where parents emphasized starving children when they ordered you to eat your food, so I take this to heart, and I eat a lot.

Eventually, in a quiet restaurant at the Top of Europe (highest point of the continent that can be reached by train), relieved to escape the tourist hordes, I ask a waiter about this no-wasted-food rule, while I am debating what to order. Sure enough, he sincerely informs me that he hates to see food wasted in a world where so many don’t have enough. I am impressed with this compassion in a culture best known for precision and order, and vow to make the size of my eyes correlate with that of my stomach from now on.

But the real purpose of this account of the Swiss Alps is to describe the terrain in words. Here is the view from our hotel verandah:

The Glacier Visible from our Hotel Deck

The edges of two separate glacial landscapes seem to advance and retreat as I watch. Clouds, at times white and fluffy, at times gray and serious, sweep over and off the faces of the cliffs. Each glacier defines a distinct scene, tranquil but not still for long amidst the patterns of moving light and shade. Then a glacier, shrouded, is lost completely. Then the whole system is lit by a rose sunset glow, so that a solid rock face appears to be made out of a soft red ice.

One time in the middle of the night the sky is studded with diamond-like stars; the snow a soft luminescent blanket, pierced by the gigantic pyramids that are the mountains’ tips. Later a partial moon lends all this a soft glow, leaving nothing in sharp relief.

On the first day we stroll to a cable car from our room and immediately ascend hundreds of vertical feet to a high plateau. We walk and gape and chat with other tourists as we take in the fabulous view. We traipse across a high saddle to a cafeteria where my plate of tuna and raw veggies is a tremendous relief after the richness of Parisian repasts.

View from the Cable Car

The mountains garbed in glaciers—Vetterhorn, Schreckhorn, Eiger, Mōnch; and Jungfrau—parade around us, their towering visages clouded, then clear, then clouded again.

We hike down to Kleine Scheidigg, take the train back to Wengen, walk up the hill to our hotel, and every time I look up they are still there. Vistas, glaciers, sun and clouds.

As Ram Dass would say, “So what’s wrong with that?” Nothing, Ram Dass. Absolutely nothing.

On the second day we pay too much and get on the train to the Top of Europe, where there are HUGE ##s of people, as in elevator lines of ½-1 hour amidst family tour groups. And yet…

I decide to assert myself in order to circle every perimeter with no one between me and the view, and I am so determined that the people give way sooner or later. At one point I venture about 200 feet out onto the snow and ice.

It is a compressed mini-trek, complete with precarious footing and that sense of wonder as humanity falls away and the wilderness exerts its spell.

Always present. Always looming. Always more than we humans can conquer, with our cables and wires and trolleys and trains. The high cliffs and peaks and glaciers and waterfalls that spill down sheer surfaces for hundreds of feet.

This huge splendor that has spawned us all, that is where our atoms return to their star composites, that spreads from the oceans and the lowlands and the hills to the tips of the highest peaks. Out and out and out. Into the infinity of dark space and black holes our human brains cannot yet comprehend.

Next comes the day of the Lauterbrunnen valley walk, a long amble through the most beautiful valley I have ever seen—larger, wider, deeper than Yosemite.

Lauterbrunnen Seen from the Valley’s Rock Wall