Zak Mucha's Blog

October 10, 2025

An American Ambulatorium

... originally published by The Center for Critical and Clinical Analysis. April 2025...

An American Ambulatorium

A pal of mine, a Zen Buddhist monk, was asked by a mid-level corporation to present a mindfulness workshop for staff because people were overworked and getting burned out. The monk said, “No, I can’t do a mindfulness workshop, but I’d be glad to talk about collective bargaining or Marxism if you’d like.” The invitation was rescinded.

Psychoanalysis can embody more of that refusal, a refusal not dependent upon the offer, but one which recognizes a different measure of value. In her book, Persian Blues, psychoanalyst Gohar Homayounpour equates the origins of blues music and psychoanalysis as protests against the dominant culture, both holding their deepest purpose when at the margins of society. And she notes both, when mainstreamed, lose their reason to exist.

Right now, go ahead and try to find contemporary blues music that wouldn’t be out of place on a cruise ship. Some professions and practices may remain undiluted at the margins, but psychoanalysis may be at the wrong margins. Our lack of outreach to communities and institutions where psychoanalysis is not available has, so far, upheld the cultural biases psychoanalysis has earned as an elitist, solipsistic, jargon-loaded crowd talking only to itself.

In Chicago, we have a plan for a psychoanalytic training program for clinicians in community mental health clinics. Too often, talented and dedicated clinicians, often minorities, who are systemically underpaid, over-worked, and lacking real resources take work in communities where psychoanalysis is not an option for patients and psychoanalytic training and supervision is not available. These clinicians, often minorities, working with clients, also often minorities, must leave community settings for better pay, benefits, and education if they even consider that an option due to the structural racism in psychoanalysis. This interruption of care and protection ripples through the families and communities of these patients, further redefining mental health care negatively.

The lack of trained psychotherapists and psychoanalysts in community mental health supports the old “evidence-based” model of medication-and-case-management-only, as Bertram Karon argued decades ago in his paper, “The Fear of Understanding Schizophrenia”:

“If the therapist does not know how to do therapy, it is true that medication works better than psychotherapy. If bicycle riding were studied the same way, using only people who had never ridden a bicycle before, it would be concluded that human beings clearly cannot ride bicycles.”

Without this effort of creating a community psychoanalytic track, we foreclose on a potential generational change. Consider how many people in the field are in the field because they had an analyst with whom they changed the trajectory of their life. Consider how many people became psychoanalysts because their parents are psychoanalysts. This doesn’t happen where psychoanalysis is not an option.

We cannot stay comfortable on the cruise ship as we watch our government gleefully dehumanize those who are not white, cis-gendered, heteronormative males. If our field doesn’t reach out to populations that have no access to psychoanalysis then we continue supporting the transgressions of a cruel authority that decides what people are worth the investment. Obama will not be coming to the rescue.

learning psychoanalysis the hard way

...an excerpt from a presentation to the first year psychoanalytic classes at Trinity College Dublin...

Long before psychoanalysis I could accept maybe a handful of people whom I allowed to teach me. My most demanding teacher also saw the trip-wires around any humiliation set off by my own not-knowing. Far from soft, he was blunt and precise. Over 30 years he has become closer to me than blood, but when I was still a teenager, I saw how he impressed and/or terrified most people with whom he interacted. In our exchanges I never felt mortified by what I didn’t know, precisely because of his status in the world and in my mind. As he was a lawyer with extensive knowledge of criminal pathologies, I learned what a piquerist was long before I learned what a psychoanalyst was.

Outside of that relationship I protected myself from that not-knowing to avoid any dependence upon the other. In his book, On Balance, Adam Phillips wrote of the inescapable helplessness of living that demands our involvement with others, and cites Freud’s notice that we can begrudge our own helplessness, calling up or recalling the wish for a protective object, provoked by a terror of being unloved:

The catastrophe of being a human being is that we are irredeemably helpless creatures. And that means, helpless to do anything about our helplessness. We are essentially helpless, and that is the very thing that makes our lives impossible. It is the mark of our own resistance to our helplessness that we deem the ineluctable to be catastrophic; as though anything we don’t make for ourselves is bad for us.

Philips also notes, more importantly, that recognizing our helplessness is a prerequisite for the possibility of a satisfaction in life, one that I tried to foreclose, protectively avoiding the shame of not-knowing. Defending myself from that terror of the loss of love and that catastrophic dependence, I barred my own formal education for years to avoid acknowledging that basic helplessness.

To want to understand those childhood glimpses of the adult world – violence in war or in the front yard, parents’ whispering, prayers from the old country only the old women knew, or jokes the men told drinking beer – and to not have them explained when I was a child left me desperately wanting to know. And left me reluctant to trust those who might have been able to tell me precisely because they would not. Ashamed to have this want denied, not knowing becomes humiliating. I would teach myself, then.

If I was supposed to know something, then it did not have to be explained to me, allowing the other to never have to risk exposing their own selves by putting these expectations into words. If there are no secrets, then everything is a potential secret and nothing can be said. Speaking of them becomes proof of not-knowing. And not speaking becomes knowing. The child who suspects the house is haunted is certain there is something others are not speaking of, whether they know it or not is the mystery.

Those hauntings, placeholders for the intergenerational and interpersonal family secrets, cannot be discussed or understood. If they are spoken of, the unknown, the gap between people, the gaps between what we each know, is illuminated. Unrecognized, these “ghosts in the nursery” follow us, marking off the spaces we cannot think of and we cannot think in.

*

July 1, 2025

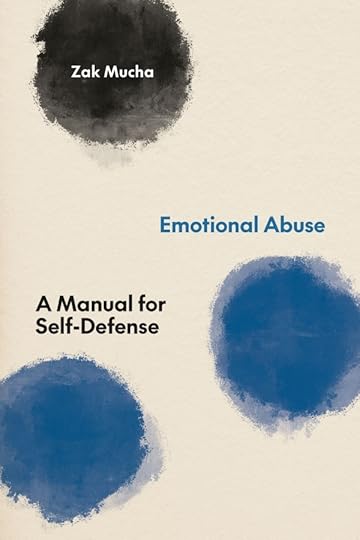

Emotional Abuse: A Manual for Self-Defense

The Perfect Weapon (pt. 1) from Emotional Abuse: A Manual for Self-Defense

There is no real difference between physical, sexual, and emotional abuse.

All that distinguishes one from another is the abuser’s choice of weapon.

—Andrew Vachss

We have been socialized to believe emotional abuse is not serious. We have been taught emotional abuse itself is nothing more than hurt feelings and there is no real evidence other than the victim’s complaints. And if the only evidence is the victim’s complaints, we wrongly justify, then there is no way to verify whether a person was actually hurt. The victim of emotional abuse is dismissed precisely because they cannot “prove” their feelings. Emotional abuse creates a vicious dynamic wherein the victim is taught their feelings do not count and any pain suffered is, somehow, their own fault.

Like any other abuse, emotional abuse is about power. Whoever can define reality has the ultimate power. In emotional abuse, the aggressor attempts to define reality with statements such as You’re too sensitive and I couldn’t help it. You made me mad. Each statement is an attempt to shape how another person perceives reality.

Emotional abuse teaches us to blame ourselves for being hurt. We learn to redefine ourselves in the hope that we do not get attacked again. In redefining ourselves, we retreat to new, constricted boundaries—where we can go, what we can say, and how we “should” feel. We do this in an effort to avoid pain. When we cannot escape emotional pain, we try to tell ourselves it’s not that bad. We minimize our own pain, criticizing ourselves for being hurt. We imitate and incorporate the aggressor’s accusations, repeating the same things they have told us about ourselves and the world. The abuser will present layers of excuses and justifications while the unstated truth continues to be I will continue doing this as long as there is no cost.

The aggressors justify their actions: If someone is hurt, they must be overreacting. They must be too sensitive. They didn’t get the joke. As a society, we remain willing to accept the abuser’s minimizations. It is easier to blame the victim. Righteous indignation and efforts to stop the abuser in cases of physical and sexual abuse do not exist when the abuse is emotional or psychological. Instead, we accept the abuser’s excuses: I didn’t say that. You misunderstood me. I was angry. You made me mad. I have a right to say what I want. I couldn’t help myself. You’re too sensitive. It was a joke—let’s forget it and start over. I was just being sarcastic . . .

This is why emotional abuse is a weapon equal to, if not more damaging than, physical or sexual abuse: We have been taught to accept the abuse. Emotional abuse becomes the perfect weapon when the abuser’s excuses are accepted by the victim and by the community. The perfect weapon is one no one sees. The perfect weapon is one the aggressor can hand over to the victim to use against their own self. The perfect weapon is self-perpetuating. The perfect weapon leaves the victim believing they deserved the attack.

May 29, 2025

an introduction by dogo barry graham

from the introduction to Emotional Abuse: A Manual for Self-Defense

Words are dangerous, and they cause permanent harm, because they mean things. Yet it is common for people to say, "Those are just words. They don't mean anything." The reality is that meaning things is the only function of words, and their meaning causes deeper wounds than most physical injuries. As Zak Mucha points out in this brilliant, urgent, impassioned and compassionate book, we can remember the factual details of a physical injury, but we cannot recall the pain, while to remember an emotional harm is to relive the pain, to experience the harm again. The wounds caused by emotional abuse, whether caused by vicious words or cruel silence, are not healed by time.

Zak Mucha understands words; he is an internationally-acclaimed poet and novelist. He also understands silence; he is a serious practitioner of Zen Buddhism. And, as a psychoanalyst who also spent years as a social worker (as well as time as a furniture mover, truck driver, construction worker, union organizer and journalist) he understands how words, and silence, can cause emotional carnage. In this regard, he is the opposite of a pacifist. This book is not for those who believe in turning the other cheek (which will also get slapped, or worse), but for those who want to defend themselves and need training.

Zak Mucha's words are dangerous to abusers, because his words mean things, and they name things. They name and describe the mechanisms of emotional abuse, and in doing so they provide weapons of self-defense and methods of liberation.

Michel Foucault said his books were written for users, not readers, and the same is true of this book, which may save lives.

—dogo barry graham

Comraich airson Lusan Leònte/Wounded Plant Sanctuary

Glasgow

Summer, Year of the Rabbit

January 31, 2025

The Monster Loves His Labyrinth -- The Zen of Charles Simic (pt. 3)

... the trickster lie, held lightly in order to explain another truth. The trickster lie is the joke told serious, explaining indirectly. The manifest alludes to the truth beneath, exactly the opposite of the stuff of conspiracy theories and the paranoia of the American political climate where the manifest statement declares exactly what’s happening with a certainty that is nearly psychotic.

In the 1990s, sociologist Susan Lepselter examined the creation of (now quaint-seeming) UFO conspiracy theory narratives. Through their observations of the world, her subjects created new patterns that “follow that quick leg of the semiotic journey where the public sign is internalized, and then reproduced as another sign, or another story...” The anecdote becomes a form of knowledge creating new patterns that ascribe meaning to chance encounters. As Lepselter describes, “this affect as it moves from a fleeting sensation to the center of things,” helps to create the conspiracy theories and fantasies that explain our world with a certainty held tightly against the terror of lives directed by chance.

Charles Simic accepted chance in all its joy and tragedy as creator of our world. In Dime-Store Alchemy, he wrote of Joseph Cornell’s collages and assemblages:

“You don’t make art, you find it. You accept everything as its material… The collage technique, that art of reassembling fragments of preexisting images in such a way as to form a new image, is the most important innovation in the art of this century. Found objects, chance creations, ready-mades (mass-produced items promoted into art objects) abolish the separation between art and life. The commonplace is miraculous if rightly seen, if recognized.”

The process of finding the image, the poem, the story, reminds me of therapy sessions where both the patient and analyst are both surprised by what came up by the end of the hour. Collage, like a conversation of unedited associations, allows us to catch glimpses and references of our associations that build our worlds, our ideologies. A meaning begins to hint at itself. Things that were not meant to be linked now are and signify something new, an angle on the world we did not have before.

A therapy session that surprises both the therapist and patient becomes a poem in this way and the arc of a therapeutic relationship becomes a glimpse of that unutterable whole. Like psychoanalysis, poetry is this effort of trying to be as precise as possible, adjacent to direct meaning, while not knowing what it is we’re trying to say.

Psychoanalytic work demands we incorporate the uncertainty of the world, the unknowable, into our existence. The horrific what ifs, what-nexts, shoulds and the dread of how-do-they-see-me exist, marking the unbearable anxieties left wordlessly outside of our narratives while driving our behavior. These what-ifs are trick questions that demand, humorlessly and impossibly, for definitive answers. Psychoanalyst Anton Hart wrote that this work is not about uncovering the unconscious as much as building up a tolerance to the unconscious, which is always creating itself anew.

Charles Simic’s humor is that of the trickster pointing out the impossibility of safely knowing the world. Like the 15th century Zen master, Ikkyu, whose poems venerated the brothels and wine shops but mocked the priests who worshipfully doused their buddha statues with incense. These are the great jokes of contemplative religious practice – jokes that are true, jokes that, like all jokes, hold an edge of hostility in their upending of the receiver’s expectations and tell us something new, and true, about the world.

Psychoanalyst Eugene Mahon traces the “ah ha moment” of an analytic session where the patient takes in an insight that suddenly shifts a perception of the world. Mahon traced the etiology of “ah ha” back to Jeremiah and Ezekiel, when humankind, or the speaker, is faced with a revelation and asks God, “Is this so?”

In conjunction with Mahon’s “ah ha moment”, we have to also hold onto the suggestion from Wilfred Bion, a psychoanalyst whose war experience influenced his clinical work, that we keep “the capacity to have feelings of respect for the unknown.” This is again, akin to the Zen Buddhist sense of self as being more than a singular subject and the paradox of the self that doesn’t exist but is sitting on a hot stove.

Simic’s work asks us to stay open to the possibilities of the unknown as well as the impossible questions with which we are left, reminding me of Michael Eigen’s summary of Bion’s unknowable reality, which Bion labelled as ‘O’, the great unknown: “We cannot count on the niceness of O.” Bion’s ‘O’ also reminds me of a Talmudic scholar, quoted by Richard Rohr, who wrote: “God is not nice. God is not an uncle. God is an earthquake.”

That unknown, unformulated thought is where we might create meaning as the coming moment has the potential to change the one just passed. And each moment becomes this perpetual emergence as the past no longer exists except as stories we tell ourselves.

And Simic notes both the safety and threat of the stories we tell ourselves:

“All lives are strange, but the lives of immigrants and exiles even more so. My parents died a long way from where they were born. It’s not how they imagined their lives were going to be. Even at the age of eighty-eight in a nursing home in Dover, New Hampshire, my mother was puzzled. What does it all mean, she wanted to know? What terrified her was the likelihood that it meant nothing.”

***

January 17, 2025

a new year's note from the Chicago Center for Psychoanalysis...

A New Year’s Note from the Chicago Center for Psychoanalysis

Simone de Beauvoir wrote of Americans in her travelogue of 1947:

“They witness the rise, more ominous every day, of racism and reactionary attitudes—the birth of a kind of fascism. They know that their country is responsible for the world’s future. But they themselves don’t feel responsible for anything, because they don’t think they can do anything in this world.”

Little has changed except we’re moving ahead at an AI algorithm’s pace as our government (shorthand for capitalism/colonialism/white supremacy/patriarchy) openly justifies the dehumanization of others unlike themselves.

Beauvoir noted that freedom and responsibility are linked. Poet and critical theorist Maggie Nelson also linked freedom with care – an active care for others as well as the world. For both writers the idea of “freedom” demands work, demands an acknowledgment of the other unlike us. And both touch upon Emmanuel Levinas’ “ethical subject” whose responsibility is to not turn away from suffering.

If we can accept a definition of freedom which places us in the world, interconnected to, impacted by, and responsible for others, then the dialectics of Beauvoir and Nelson ask us to accept things as they are and to simultaneously push to change them.

CCP offers more than professional training, education, lectures, and CEUs; we hope we are creating change in the world, individually and systemically. Our roles as social workers, psychotherapists, teachers, supervisors, and analysts ask us to be nurturing in a neglectful environment.

We have the opportunity and potential to do amazing work, to reduce the suffering of others. The first of the four great vows in Zen Buddhism says: “Sentient beings are numberless, I vow to save them.” Like most teachings in Zen, the important part is silent: We must count ourselves among that infinite number of beings as we practice and study so we can become the kinds of healers we imagine.

I hope we can continue to take care of ourselves, those we love, and those we don’t even know across the coming year.

Happy New Year.

Zak Mucha, LCSW. Chicago Center for Psychoanalysis

October 23, 2024

September 7, 2024

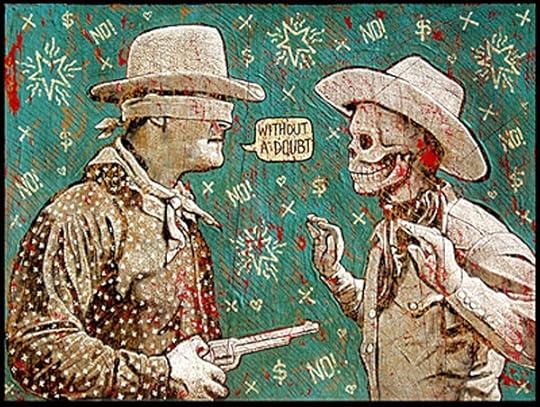

The Redneck Sigmund Freud

Among Jon Langford’s cowboy portraits, he has a few of Hank as Saint Sebastian – shirtless, bound, and run through with arrows. Hank is the Hillbilly Shakespeare and the Godhead for previous generations of country music. I’ve heard him described as the sin-eater for southern whites, his self-destruction saving others from themselves, if that’s how it actually works.

But Hank doesn’t get enough credit as a psychiatric diagnostician. On social media it’s standard now to diagnose one’s ex as having either borderline or narcissistic personality disorder. Hank specialized in the detailed illustration of the borderline and narcissistic personality structures dyad, a relationship where two terribly broken plates fit together perfectly until one or both shatters.

Listen to “First Year Blues” for proof.

Hank Williams was the Redneck Sigmund Freud.

September 1, 2024

The Monster Loves his Labyrinth (pt. 2): the Zen of Charles Simic

In Not Always So, a compilation of lectures by the Zen priest, Shunryu Suzuki, he declared: “My mind is a garbage can,” with a sense of joy, referencing the freedom to accept all thoughts that pass through without clinging to or refusing them.

The poet Charles Simic said, “A poem is a place where affinities are discovered. Poetry is a way of thinking through affinities.”

The Heart Sutra says, “form is emptiness and emptiness is form…” this ‘emptiness’ is not nihilism but is an interconnectedness of all things and a lack of the narcissistic sense of self which separates us from all things. Nothing can be defined without the existence of and comparison to all other things. The self doesn’t exist without recognition of all things and in those moments where all things are recognized, then the self ‘is’ also, but only for the moment... Zen monk, Dogo Barry Graham once said, “There is no self, but go sit on a hot stove and see who screams.”

As a child in Belgrade, Simic survived the German bombing and Nazi occupation and his childhood became a series of disruptions and displacements as he and his family crossed boundaries delineated by violence, ethnicity, culture, and language. In his poetry, the trauma of multiple displacements is presented by crossing boundaries between consciousness and dreams, magic realism and brutal reality, religious mystery and black humor and accepting each paradox as true. He describes his family’s survival during war:

“… we used to barter our possessions for food. You could get a chicken for a good pair of men’s shoes. Our clocks, silverware, crystal vases and fancy china were exchanged for bacon, lard, sausages and such things. Once an old gypsy man wanted my father’s top hat. It didn’t even fit him. With the hat way down over his eyes, he handed over a live duck.”

Life and death intermingled with absurdity and chance. Buster Keaton again. How else does one survive war and how does one keep their soul? How much do we have to feel in order to, simply, not take it all so seriously while simultaneously knowing this is exactly what life is? How do we reconfigure our perception of the world after trauma redefines the world for us? An absurd, unpredictable universe becomes either a perpetual threat or a chance for freedom.

Simic describes a meal in a restaurant with his Uncle Boris, both of them new to the U.S. after emigrating from Belgrade. Two women at the next table, well-to-do Americans, cannot place their accents, so they interrupt to ask. Boris, a perpetual trickster, gave a sad sigh and explained, in detail, they are part of the last Caucasian tribe of Africans and their language is a dialect that will go extinct with them. This, Simic also says, is poetry: “Poetry should contain every possible lie that can be told.”

But this is the trickster lie, held lightly in order to explain another truth. The trickster lie is the joke told serious, explaining indirectly. The manifest alludes to the truth beneath, exactly the opposite of the stuff of conspiracy theories and the paranoia of the American political climate where the manifest statement declares exactly what’s happening with a certainty that is nearly psychotic.

August 24, 2024

Charles Simic: The Monster Loves his Labyrinth (pt. 1)

The Monster Loves His Labyrinth: The Zen of Charles Simic

It seems like there’s always laughter in Charles Simic’s poems. Not in the line or action, subject or narration, but there’s almost always the sense, no matter the darkness of the actual text, that he knew someone was laughing somewhere. Simic was always sharing the joke of the impossible world.

In his notebook of aphorisms, The Monster Loves His Labyrinth, Simic continues to circle around a definitive definition of poetry, at one point finding poetry as a scene from a Buster Keaton short: “… That’s what great poetry is. A superb serenity in the face of chaos. Wise enough to play the fool.”

For Simic, Buster Keaton was as inspirational as Heidegger. We are thrown into being, standing still as the house falls perfectly around us. Simic’s notebook is filled with musings and explanations of poetry, working out the impossible paradoxes in his mind, much like Zen Buddhism and psychoanalysis, where definitions are always to be reconsidered.

Simic wrote:

“The poem is an attempt at self-recovery, self-recognition, self-remembering, the marvel of being again… A poem is a piece of the unutterable whole.”

But he also wrote:

“If I make everything at the same time a joke and a serious matter, it’s because I honor the eternal conflict between life and art, the absolute and the relative, the brain and the belly, etc…. No philosophy is good enough to overcome a toothache.”

There is more than a touch of Zen Buddhism in Simic’s acceptance of paradoxes, of the impossibility of solely occupying one space in life, that none of this is what it looks like, while also, whether we like it or not, the world is exactly what it looks like.